SUMMARY

Changes in the extracellular ionic concentrations occur as a natural consequence of firing activity in large populations of neurons. The extent to which these changes alter the properties of individual neurons and the operation of neuronal networks remains unknown. Here, we show that the locomotor-like activity in the isolated neonatal rodent spinal cord reduces the extracellular calcium ([Ca2+]o) to 0.9 mM and increases the extracellular potassium ([K+]o) to 6 mM. Such changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o trigger pacemaker activities in interneurons considered to be part of the locomotor network. Experimental data and a modeling study show that the emergence of pacemaker properties critically involves a [Ca2+]o-dependent activation of the persistent sodium current (INaP). These results support a concept for locomotor rhythm generation in which INaP-dependent pacemaker properties in spinal interneurons are switched on and tuned by activity-dependent changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o.

INTRODUCTION

Rhythm generation is a key feature of repetitive behaviors such as locomotion, mastication, and respiration. Two main concepts have been proposed to account for rhythmogenesis in central pattern generators (CPGs) (Marder and Bucher, 2001). The pacemaker concept relies on neurons that generate inherent rhythmic bursts of spikes when synaptic transmission is blocked. In contrast, the network hypothesis suggests that the rhythm arises from nonlinear synaptic interactions. The specific contribution of cellular and network properties in generating rhythmic activities underlying locomotion are not understood. The persistent (slowly inactivating) sodium current (INaP) was suggested to play an important role in generating rhythmic motor behaviors (Brocard et al., 2010; Butera et al., 1999; McCrea and Rybak, 2007; Pace et al., 2007; Paton et al., 2006; Rybak et al., 2006; Tazerart et al., 2007; Zhong et al., 2007), and INaP-dependent pacemaker properties may represent a common feature of CPGs (Brocard et al., 2006;Rybak et al., 2006; Tazerart et al., 2008; Thoby-Brisson and Ramirez, 2001; Ziskind-Conhaim et al., 2008). Importantly, blockade of INaP by riluzole abolishes locomotor-like activity in rodents (Brocard et al., 2010; Tazerart et al., 2007; Zhong et al., 2007).

In newborn rodents, interneurons considered to be elements of the motor CPGs express intrinsic riluzole-sensitive bursting properties when removing extracellular calcium (Brocard et al., 2006; Tazerart et al., 2008). Concomitantly, INaP was increased and its activation threshold was shifted toward more negative voltages (Tazerart et al., 2008). Such properties observed in nonphysiological conditions (zero calcium) raise the question of their functional relevance to the normally operating network. Although changes in the ionic concentration of the extracellular space are usually not considered as relevant physiological signals, the locomotor activity was shown to increase the extracellular concentration of potassium ([K+]o) in the spinal cord (Marchetti et al., 2001; Wallén et al., 1984). While the precise dynamic changes in [K+]o during locomotion remain to be determined, no attention has been paid to the possibility that changes in the extracellular calcium concentration ([Ca2+]o) might regulate the firing properties of spinal CPG interneurons. The objectives of this study were (1) to measure changes in [K+]o and [Ca2+]o occurring with locomotor-like activity in the isolated spinal cord and (2) to determine their effects on pacemaker bursting properties of isolated spinal interneurons. We show that the generation of pacemaker activity is determined by the ongoing modulation of INaP and potassium currents resulting from simultaneous changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o.

RESULTS

Reduction in [Ca2+]o and Increase in [K+]o during Locomotor-like Activity

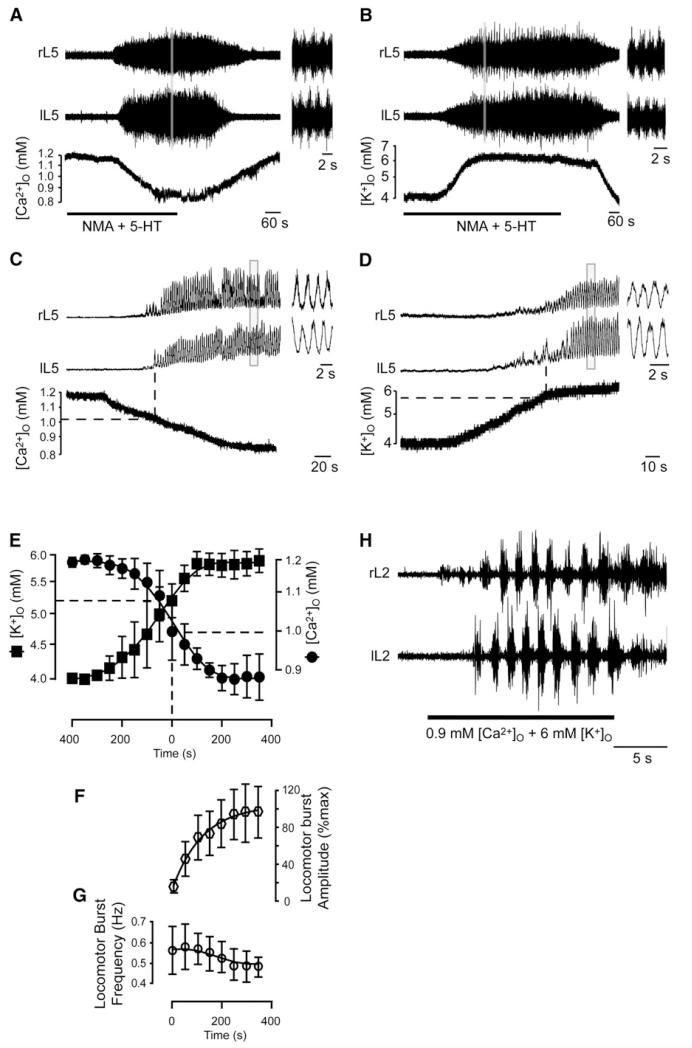

By means of ion-sensitive electrodes, we measured [Ca2+]o and [K+]o in the ventromedial part of upper lumbar segments (L1-L2), the main locus of the locomotor CPG (Cazalets et al., 1995;Kjaerulff and Kiehn, 1996). At rest, the values of [Ca2+]o (1.2 mM) and [K+]o (4 mM), determined by the composition of the Krebs solution, were similar to those measured in vivo in the neonatal rat cerebrospinal fluid (see Table S1 available online). During locomotor-like activity, characterized by alternating bursting activities of opposite lumbar ventral roots, the [Ca2+]o decreased (Figure 1A) and the [K+]o increased (Figure 1B). Both [Ca2+]o and [K+]o concurrently changed before any rhythmic activity was detected from ventral roots (Figures 1C-1E). At onset of locomotion, [Ca2+]o has declined to 0.99 ± 0.01 mM (n = 14; Table 1) and [K+]o has increased to 5.18 ± 0.05 mM (n = 29; Table 1). As locomotor-like activity developed, [Ca2+]o and [K+]o changes were related with the increase in burst amplitude (Figures 1E and 1F) without apparent relationship with the frequency (Figures 1E and 1G). Then, [Ca2+]o and [K+]o reached a steady-state level as locomotor-like activity became stable. The steady-state [Ca2+]o and [K+]o changed as the locomotor rhythm speeded up as a result of incremental concentrations of NMA (Table 1). Within the range of NMA concentrations (8–12 mM) enabling locomotion, [Ca2+]o declined further from 0.94 to 0.84 mM and [K+]o increased from 5.5 to 6.1 mM. With concentrations higher than 14 μM, left-right alternations switched to a tonic activity; the steady-state levels of [Ca2+]o and [K+]o in these conditions were 0.8 ± 0.04 mM (n = 5) and 6.5 ± 0.08 mM (n = 7), respectively. Similar changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o were also observed in neonatal mice when locomotor-like activity was electrically induced by stimulation of the ventral funiculus (Table 1 and Figures S1A and S1B).

Figure 1. Variations of [Ca2+]o and [K+]o during Locomotor-like Activity.

(A–D) Changes in [Ca2+]o (A and C) and [K+]o (B and D) in the locomotor CPG during (A and B) and at the onset (C and D) of NMA/5-HT induced locomotor-like activity in neonatal rat preparations. Raw (A and B) and rectified/integrated (C and D) traces of locomotor output recorded from opposite L5 ventral roots. Insets illustrate enlargements of the recordings (gray vertical line). (E–G) Time course of [Ca2+]o and [K+]o changes before and during locomotor-like activity in relation to amplitude (F) and frequency (G) of bursts. Error bars indicate SEM. Time 0: onset of locomotion. Dashed lines in (C)–(E) represent threshold of [Ca2+]o and [K+]o at the onset of locomotion. (H) Fictive locomotor episode induced by an aCSF composed of 0.9 mM [Ca2+]o and 6 mM [K+]o pressure applied over the CPG.

Table 1.

Changes in [Ca2+]0 and [K+]0 during Locomotor-like Activity

| NMA, 8 μM | NMA, 10 μM | NMA, 12 μM | Electrical Stimulation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 4 | n = 5 | n = 5 | n = 5 | |

| Threshold [Ca2+]o | 0.99 ± 0.03 mM | 1.01 ± 0.03 mM | 0.98 ± 0.06 mM | 1.03 ± 0.01 mM |

| Steady-state [Ca2+]o | 0.94 ± 0.01 mM | 0.88 ± 0.03 mM | 0.84 ± 0.03* mM | 0.92 ± 0.01 mM |

| Locomotor period | 2.5 ± 0.19 s | 2 ± 0.05 s | 1.6 ± 0.15** s | NA |

| n = 4 | n = 15 | n = 10 | n = 5 | |

| Threshold [K+]o | 5.2 ± 0.16 mM | 5.16 ± 0.05 mM | 5.2 ± 0.12 mM | 5.19 ± 0.09 mM |

| Steady-state [K+]o | 5.5 ± 0.08 mM | 5.86 ± 0.06 mM | 6.1 ± 0.2** mM | 6.35 ± 0.08 mM |

| Locomotor period | 2.6 ± 0.3 s | 2 ± 0.07 s | 1.8 ± 0.1** s | NA |

Values represent the means ± SE of [Ca2+]o and [K+]o measured at the onset of locomotor-like activity (threshold) and when locomotor-like activity was stable (steady state). The locomotor period represents the cycle frequency of ventral root bursts recorded during steady locomotion. With one-way ANOVA test, statistical significance was evaluated as the difference between values measured for a locomotor-like activity induced by 8 μM and 12 μM of NMA, respectively. NMA, N-methyl-DL aspartate; n, the number of preparations.

In the cerebrospinal fluid of rats, [Ca2+]o remains constant with age but [K+]o decreases to ~3 mM in adults (Table S1). We therefore investigated whether the locomotor-related changes in [K+]o are different when the [K+]o of the artificial cerebral spinal fluid (aCSF) is initially set at 3 mM. In this condition, and as previously reported (Vargová et al., 2001), the baseline [K+]o within the spinal cord was higher than that of the aCSF (3.53 ± 0.1 mM, n = 10). At the onset of locomotor-like activity induced by NMA/5-HT (10 mM/10 mM), the [K+]o had increased to 5.1 ± 0.06 mM (n = 10) and then plateaued at 5.7 ± 0.13 mM (n = 10) (Figures S1C and S1D). In sum, significant and reliable changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o accompany the operation of the locomotor CPG in rodents such that values of [Ca2+]o and [K+]o reach ~ 0.9 mM and ~6 mM, respectively. When applied over the rostral lumbar segments, an aCSF composed of 0.9 mM [Ca2+]o and 6 mM [K+]o triggered an episode of locomotor-like activity in all preparations tested (n = 7; Figure 1H).

Membrane Oscillations in Locomotor-Related Interneurons Emerge Concomitantly with the Changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o

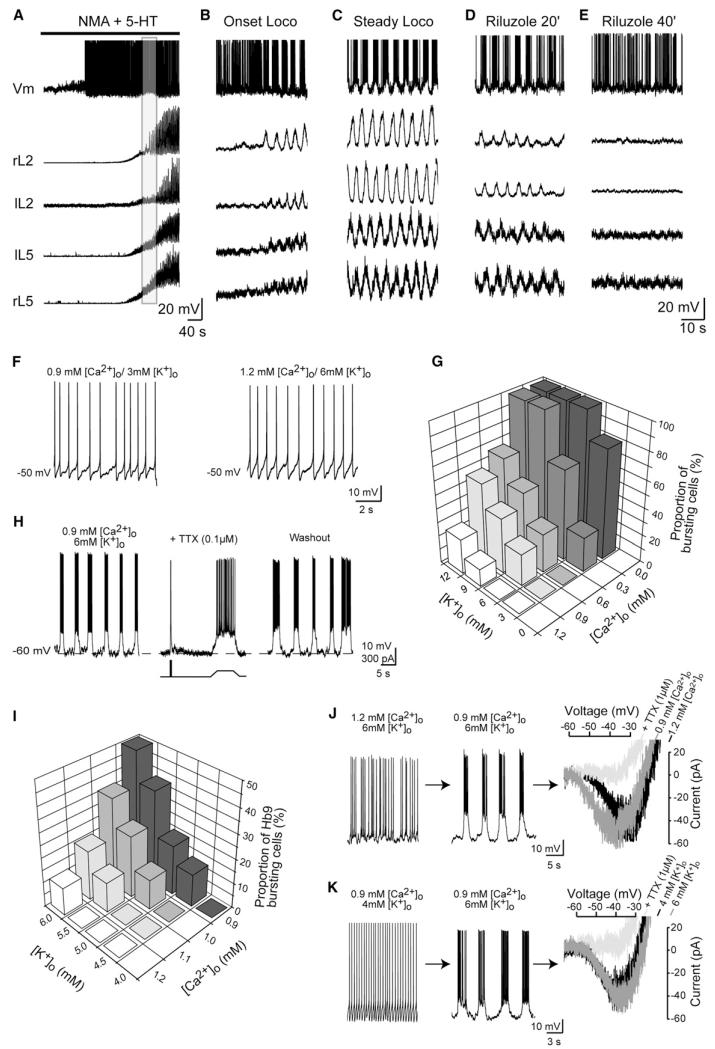

Blind whole-cell recordings were performed from ventromedial neurons in the L1-L2 region to further investigate the relationship between changes in ionic concentrations and firing properties. Interneurons were identified by their high input resistance (604 ± 75 MU, n = 18) and the absence of antidromic response to ventral root stimulation. A few minutes after NMA and 5-HT were applied, and long before the locomotor-like activity emerged, all interneurons (n = 18) were spiking (Figure 2A). Simultaneous recordings with ion-sensitive microelectrodes and intracellular pipettes enabled linking changes in ionic concentrations to the cellular activity (Figures S2A and S2B). Half of the recorded neurons switched their firing pattern from spiking to bursting, either at the onset of locomotor-like activity (3/8 neurons; Figure 2B) or during ongoing locomotion (5/8 neurons). Superfusion of riluzole (5 mM) to block INaP progressively reduced the amplitude of membrane oscillations, which then became undetectable (Figures 2D and 2E). As described previously (Tazerart et al., 2007; Zhong et al., 2007), the ventral root burst progressively decreased in amplitude with little effect on the cycle frequency until locomotor-like activity disappeared (Figure S2C). Furthermore, when preincubated for 45 min before the application of NMA/5-HT, riluzole (5 μM) prevented the emergence of locomotion (n = 3, Figure S2D).

Figure 2. Changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o Precede and Trigger INaP-Dependent Bursting Properties.

(A–E) Activity of a locomotor-related interneuron before (A), at the onset (B, enlargement of the gray area in A), and during (C) an NMA/5-HT-induced locomotorlike activity and 20 min (D) or 40 min (E) after the superfusion of riluzole (5 μM). (F) Voltage traces illustrate the effects of varying [Ca2+]o or [K+]o alone (within the range of fluctuations observed during locomotion) on the firing pattern of interneurons recorded in the locomotor CPG region of neonatal rats. (G) The threedimension histogram plots the proportion of interneurons exhibiting pacemaker properties (y axis) against [Ca2+]o (x axis) and [K+]o (z axis). Note that for each [K+]o and [Ca2+]o concentration in which bursts emerged, at least one bursting cell was tested for the sensitivity of their membrane oscillations to the blockade of INaP (by TTX or riluzole). (H) Activity of a pacemaker cell before, during, and after a brief (~3 min) application of TTX (0.1 μM). (I) Proportion of Hb9 interneurons exhibiting pacemaker properties (y axis) against [Ca2+]o (x axis) and [K+]o (z axis). (J and K) Firing patterns of two typical Hb9 cells when the [Ca2+]o was decreased from 1.2 mM to 0.9 mM (J) or when [K+]o was increased from 4 to 6 mM (K) while [K+]o and [Ca2+]o remained constant, respectively. For each cell, the leak-subtracted membrane current evoked by voltage ramp from −70 to −10 mV is plotted before (black trace) and after decreasing [Ca2+]o or increasing [K+]o(dark gray trace). A subsequent application of TTX (1 μM) abolished the current (light gray trace).

Locomotor-Related Changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o Generate Pacemaker Properties in Putative CPG Interneurons

The following set of experiments was performed to assess whether locomotor-related changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o may initiate intrinsic bursting properties. Whole-cell recordings were performed in neonatal rat slice preparations from spinal interneurons (n = 187) located in the area of the locomotor CPG (ventromedial part of L1-L2). To discriminate the effect of ionic changes from that of neurotransmitters in generating membrane oscillations, we omitted the application of NMA and 5-HT. Reducing [Ca2+]o to 0.9 mM while keeping [K+]o at 3 mM did not affect the firing pattern (Figure 2F, left). Bursting could be induced only when reducing [Ca2+]o further to 0.3 or 0.0 mM (Figure 2G). At a constant [Ca2+]o (1.2 mM), pacemaker activities could not be evoked by increasing [K+]o to near 6 mM (Figure 2F, right) and appeared only at values above 9 mM (Figure 2G). A striking observation was the synergistic effect of reducing [Ca2+]o and increasing [K+]o on the generation of bursts. A concomitant reduction of [Ca2+]o to 0.9 mM and increase of [K+]o to 6 mM induced bursts in 25% of neurons (Figures 2G and 2H). These bursts were attributable to INaP as they were reversibly abolished by low concentrations of TTX (0.1 μM) (see Figure 2H) or riluzole (5–10 μM, data not shown).

We then switched to transgenic mice to record genetically identified Hb9 interneurons (n = 137) considered to be part of the locomotor network (Brownstone and Wilson, 2008). The threshold of [Ca2+]o to generate bursts in Hb9 cells decreased as [K+]o was increased (Figure 2I). At the [Ca2+]o and [K+]o values measured when locomotion emerged (~1 mM and ~5 mM, respectively), 12% of Hb9 cells expressed bursts. At the optimal [Ca2+]o and [K+]o with regard to locomotion (~0.9 mM and ~6 mM, respectively), as many as 50% of Hb9 cells acquired INaP-dependent bursts (Figure 2I). At these values of [Ca2+]o and [K+]o, no pacemaker activity was triggered in motoneurons (n = 15, data not shown), indicating that the emergence of bursts is not ubiquitous. The switch in the firing mode occurs through a fast dynamic process such that transient changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o instantaneously and reversibly switched the firing pattern of Hb9 cells from spiking to bursting (Figures S3A-S3F). By slowing down the fictive locomotor rhythm with nickel, a recent investigation raised the possibility that low-threshold calcium current (ICaT) regulates the locomotor rhythm (Anderson et al., 2012). In line with this, in all Hb9 cells tested (n = 5), INaP-dependent bursting properties were slowed down in frequency by nickel (200 μM; Figures S3G and S3H).

As INaP appeared to play a key role in generating pacemaker activity, voltage-clamp recordings were performed to examine the relationship between the biophysical properties of INaP and the changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o. In response to slow voltage ramps, Hb9 cells displayed a large inward current (Figures 2J and 2K, right, black traces) attributable to INaP as it was abolished by riluzole (5–10 mM) or TTX (1 mM; Figures 2J and 2K, right, pale gray traces; see also Tazerart et al., 2008). The acquisition of bursts by Hb9 cells as a result of reducing [Ca2+]o from 1.2 to 0.9 mM (Figure 2J, left and middle) was accompanied by an upregulation of INaP (Figure 2J, right, dark gray trace; see also Figure S3). The features of the upregulation were a negative shift (~3 mV) in both the current activation threshold and the half-activation voltage (VmNaP1/2) and an increase (~12%) in amplitude (Table S2). In contrast, bursting properties induced in Hb9 cells as a result of increasing [K+]o (Figure 2K, left and middle) occurred without changes of VmNaP1/2 (Figure 2K, right, dark gray trace and Table S2). It appears that the facilitation of pacemaker activities by [K+]o did not result from an increase in INaP. Note that bursting Hb9 cells differed from nonbursting cells on the basis of significantly more hyperpolarized activation threshold and VmNaP1/2 of INaP (Table S3).

Involvement of INaP and IK in Generation of Pacemaker Activities: Insights from Computational Modeling

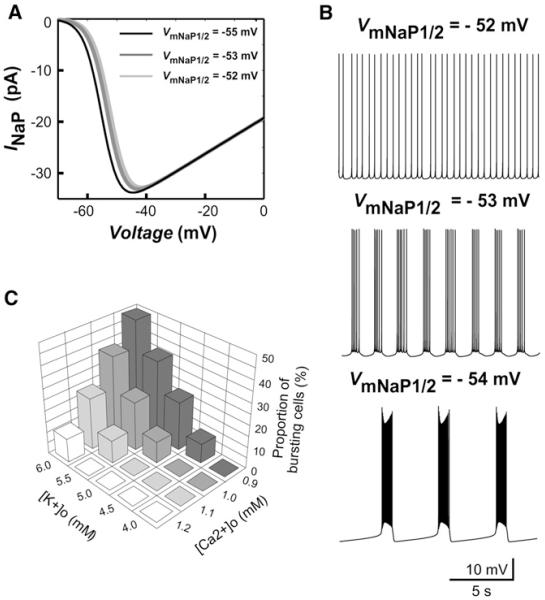

The generation of bursts results from the modulation of a variety of intrinsic neuronal properties. As described above, a decrease in [Ca2+]o explicitly amplifies INaP. In turn, an increase in [K+]o is expected to reduce the absolute value of the potassium and leak reversal potential (EK and EL, see Supplemental Experimental Procedures) and hence to reduce all voltage-gated potassium and leak currents. This should affect INaP-dependent bursting (Rybak et al., 2003). To theoretically investigate the effect of changing [Ca2+]o and [K+]o on neuronal bursting behavior, we used a single-compartment computational model of the Hb9 cell. In this model, we explicitly simulated a negative voltage shift of INaP activation with a reduction of [Ca2+]o (Figure 3A). For VmNaP1/2 = −52 mV (at [K+]o = 6 mM), the model exhibited tonic spiking activity (Figure 3B, top). Bursting activity appeared at VmNaP1/2 = −53 mV (Figure 3B, middle), and further shifting VmNaP1/2 to the left produced stable bursting with higher spiking frequency within bursts (Figure 3B, bottom). As expected, depolarizing the neuron by injecting current increased bursting frequency (Figure S4, top). Bursts disappeared when the conductance of INaP was set to 0 (to simulate the effect of riluzole, Figure S4, bottom).

Figure 3. Involvement of INaP in Generation of the Pacemaker Bursting Activity: Insights from Computational Modeling.

(A) Changes in INaP during slow voltage ramp for different values of VmNaP1/2. (B) Firing pattern of neuron in the model at [K+]o = 6 mM. At VmNaP1/2 = −52 mV, the model exhibited tonic spiking activity (top); at VmNaP1/2 = −53 mV, the neuron switched to bursting (middle), and further shifting VmNaP1/2 to the left (−54 mV) increased spiking frequency within the bursts (bottom). (C) Dependence of the percentage of bursting cells on [Ca2+]o and [K+]o (in the modeled population of 50 uncoupled neurons with randomly distributed parameters).

To investigate how random distribution of neuronal parameters could affect neuron bursting properties and the relative number of pacemaker neurons involved in population bursting, we simulated a population of 50 uncoupled neurons. To provide a necessary heterogeneity in bursting properties of neurons, we randomly distributed the base values of neuronal VmNaP1/2 (i.e., these values at [Ca2+]o = 1.2 mM and [K+]o = 4 mM) among neurons using the uniform distribution within the interval [−53, −48] mV. An additional heterogeneity was set by normal distribution of all conductances, including that for INaP. The average values and variances used for all conductances can be found in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures. Because of the random distributions used, some neurons with more negative VmNaP1/2 and/or higher values of INaP maximal conductance were intrinsic bursters, whereas the remaining neurons had no bursting capabilities. This was equivalent to our experimental data showing that bursting Hb9 interneurons had more negative values of the activation threshold and halfactivation voltage for INaP than nonbursting neurons (Table S3). After parameter distributions, simulations were run to check the ability of each neuron to generate bursts with changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o and to determine the percentage of bursting cells in the population at each level of [Ca2+]o (from 1.2 to 0.9 mM with 0.1 mM steps) and [K+]o (from 4.0 to 6.0 mM with 0.5 mM steps). Each 0.1 mM decrease in [Ca2+]o reduced VmNaP1/2 in all neurons by 1 mV (hence shifting INaP activation to more negative values of voltage); each 0.5 mM increase in [K+]o resulted in the corresponding reduction of EK and EL (see above). The results are summarized in Figure 3C. Specifically, none of the neurons exhibited bursting at base levels of [Ca2+]o and [K+]o (1.2 and 4 mM, respectively). In agreement with our experimental data, the proportion of bursting neurons increased when [Ca2+]o was reduced and when [K+]o was elevated, reaching a peak of 45%–55% for [Ca2+]o and [K+]o set to 0.9 and 6 mM, respectively (Figure 3C). In summary, our modeling study supports the fine modulation of INaP and potassium currents by [Ca2+]o and [K+]o as a key mechanism for the emergence of bursts in interneurons forming the locomotor CPG.

DISCUSSION

The critical role of pacemakers in the operation of the locomotor CPG remains controversial (Brocard et al., 2010). Conditional pacemaker properties relying on the activation of NMDA receptors have been described in many rhythm-generating motor networks (Grillner and Wallén, 1985; Hochman et al., 1994; Hsiao et al., 2002; Li et al., 2010). It appears that these properties are not critical because locomotor-like activity can be induced after blocking NMDA receptors (Cowley et al., 2005). In contrast, a critical role of INaP-dependent properties in locomotion has been confirmed in vitro (Brocard et al., 2010; Ryczko et al., 2010; Tazerart et al., 2007, 2008; Zhong et al., 2007). The mechanisms by which they contribute were unknown. Our study demonstrated that INaP-dependent membrane oscillations can arise from specific changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o observed during locomotor-like activity, so that the firing pattern of Hb9 cells switches to pacemaker mode. The inability of numerous genetic ablations to abolish the locomotor rhythm (Kiehn et al., 2010;Talpalar et al., 2011) suggests that this function is not supported by a specific population of cells. Even if the contribution of Hb9 cells to the generation of the locomotor rhythm remains under debate (Kwan et al., 2009), a small fraction (12%) of Hb9 cells acquiring bursting properties at the onset of the locomotor activity may contribute to generate a rhythmic output at the network level (Butera et al., 1999). Interestingly, such a small fraction (~12%) of locomotor-related interneurons have been shown to display intrinsic bursting properties during locomotor-like activity in neonatal rats (Kiehn et al., 1996), but the number of bursting cells may increase through gap junctions (Tazerart et al., 2008).

Changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o as a consequence of firing activity of large populations of neurons are well established in the CNS (Amzica et al., 2002; Heinemann et al., 1977; Nicholson et al., 1978). In line with this, we observed that the firing activity of locomotor-related interneurons paralleled extracellular ionic changes. In the spinal cord, both the natural limb movements and activation of sensory afferents increase [K+]o, particularly in the intermediate gray matter of lumbar segments (Heinemann et al., 1990; Kríz et al., 1974; Lothman and Somjen, 1975; Walton and Chesler, 1988), a region proposed to contain neural circuits of the locomotor CPG (Kjaerulff and Kiehn, 1996). We described in this region a rise of [K+]o up to ~6 mM (see also Marchetti et al., 2001) and a decrease of [Ca2+]o to 0.9 mM when locomotor-like activity was evoked. [K+]o and [Ca2+]o reached a steady-state level during a stable locomotor episode. The steady state of [K+]o reflects an equilibrium between the neuronal K+ efflux and its clearance from the extracellular space with neuronal Na+/K+ pump (Syková, 1987) and glial cells (Jendelová and Syková, 1991). The decrease in [Ca2+]o mainly involves an uptake into postsynaptic somata and/or dendrites (Heinemann and Pumain, 1981).

Lowering [Ca2+]o has been reported to switch the firing mode of various CNS neurons from spiking to bursting (Brocard et al., 2006; Heinemann et al., 1977; Johnson et al., 1994; Su et al., 2001; Tazerart et al., 2008). In our experiments, the reduction of [Ca2+]o requires a concomitant raise in [K+]o to trigger bursts. This synergistic effect probably results from a joint regulation of INaP and IK, respectively. An increase in INaP appears to be the major link between the reduction in [Ca2+]o and the bursting ability because a decrease of [Ca2+]o shifts the threshold of INaP activation toward more negative values and enhances its amplitude. In agreement with this, our simulation showed that the shift of the threshold of INaP activation toward more negative values plays a major role in the emergence of bursts, and even a subtle shift of activation by −3 mV produces the same effect as increasing INaP conductance by 50%. This is supported by the sensitivity of pacemaker activity to riluzole and TTX. Changes in pore occupancy of sodium channels by calcium may be responsible for these modifications of INaP (Armstrong, 1999). Although [K+]o increase does not upregulate INaP, as shown experimentally, our model demonstrates that it facilitates the emergence of INaP-dependent bursts by reducing IK as a result of reduction of EK (see also Rybak et al., 2003). The increased [K+]o also provides an additional depolarization of pacemaker cells via the reduction of the voltage-gated potassium and leak currents, which also increases the frequency of oscillations. In summary, the regulation of INaP and IK by [Ca2+]o and [K+]o, respectively, may represent a fundamental mechanism in generating and regulating the pacemaker activities in other brain areas.

Taking into account that changes in [K+]o and [Ca2+]o (1) precede the onset of locomotion, (2) promote INaP-dependent pacemaker properties in putative locomotor CPG cells, and (3) trigger a locomotor episode, a conceptual scheme can be proposed for rhythmogenesis in the mammalian spinal cord. A moderate spiking activity of CPG components causes a reduction in [Ca2+]o and increase in [K+]o. Changes in these concentrations cause the simultaneous regulation of INaP and IK, which together produce at a threshold level a switch from spiking to bursting representing the locomotor oscillations. Because changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o are dependent on the level of neuronal activity, the relative importance of pacemaker cells in rhythm generation may dynamically change with the functional state of the locomotor network. In this context, a higher recruitment of pacemakers will increase the strength of the locomotor outputs, while their depolarization will speed up the locomotor rhythm. Finally, our results support a hybrid pacemaker network concept for generation of the locomotor rhythm in which INaP-dependent pacemaker properties of CPG interneurons may be switched on by activity-dependent changes in [Ca2+]o and [K+]o and finely tuned by neurotransmitters or neuro-modulators such as glutamate or 5-HT. These results obtained in vitro represent a major conceptual advance that remains to be tested in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animals

Experiments were performed on neonatal (1-to 5-day-old) Wistar rats (n = 97) and Hb9:eGFP transgenic mice (n = 47). We performed experiments in accordance with French regulations (Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries; Division of Health and Protection of Animals).

In Vitro Electrophysiological Recordings

Electrophysiological experiments were performed on either whole spinal cord preparations or spinal cord slices. We performed dissections under continuous perfusion with an oxygenated aCSF (details in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures). In the whole spinal cord preparation, the locomotor-like activity was recorded (bandwidth 70 Hz–1 kHz) using extracellular stainless steel electrodes placed in contact with lumbar ventral roots and insulated with Vaseline. During locomotor-like activity, [Ca2+]o and [K+]o were recorded by means of ion-sensitive microelectrodes manufactured from double-barreled theta glass capillaries (protocol described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures). Slice preparations were used for whole-cell patch-clamp recordings from interneurons in the ventromedial laminae VII-VIII (neonatal rats) or Hb9 interneurons. Electrophysiological procedures used to characterize INaP are described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Simulations

We simulated the effects of [Ca2+]o and [K+]o on INaP-dependent pacemaker properties at the level of either a single neuron or a population of 50 uncoupled neurons with randomized parameters. The detailed description of the computational model is provided in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Statistical Analyses

Data are presented as means ± SEM. Nonparametric statistical analyses were employed with a Wilcoxon matched-pairs test when two groups were compared and a one-way ANOVA test for multiple group comparisons (GraphPad Software). The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Additional Methods

Detailed methodology is described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the French Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (ANR to L.V.), the Institut pour la Recherche sur la Moelle épinière et l’Encéphale (IRME to L.V. and F.B.). S.T. received a grant from the Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM). I.A.R. and N.A.S. were supported by the National Institutes of Health grant R01 NS081713. F.B. designed and supervised the overall project, performed and analyzed in vitro experiments, and wrote the manuscript. S.T. performed and analyzed some in vitro experiments in Figure 1 and Figure S3. M.B. performed and analyzed some experiments in Figure 1 and Figure S3. N.A.S. designed, performed, and analyzed the modeling study and wrote the manuscript. I.A.R. supervised the modeling investigation and wrote the manuscript. U.H. provided valuable expertise for the ion-sensitive microelectrode techniques. L.V. contributed to the design and supervision of the project and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes four figures, two tables, and Supplemental Experimental Procedures and can be found with this article online at http://dx. doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2013.01.026.

REFERENCES

- Amzica F, Massimini M, Manfridi A. Spatial buffering during slow and paroxysmal sleep oscillations in cortical networks of glial cells in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:1042–1053. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-03-01042.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson TM, Abbinanti MD, Peck JH, Gilmour M, Brownstone RM, Masino MA. Low-threshold calcium currents contribute to locomotor-like activity in neonatal mice. J. Neurophysiol. 2012;107:103–113. doi: 10.1152/jn.00583.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong CM. Distinguishing surface effects of calcium ion from pore-occupancy effects in Na+ channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:4158–4163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocard F, Verdier D, Arsenault I, Lund JP, Kolta A. Emergence of intrinsic bursting in trigeminal sensory neurons parallels the acquisition of mastication in weanling rats. J. Neurophysiol. 2006;96:2410–2424. doi: 10.1152/jn.00352.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocard F, Tazerart S, Vinay L. Do pacemakers drive the central pattern generator for locomotion in mammals? Neuroscientist. 2010;16:139–155. doi: 10.1177/1073858409346339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownstone RM, Wilson JM. Strategies for delineating spinal locomotor rhythm-generating networks and the possible role of Hb9 interneurones in rhythmogenesis. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2008;57:64–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butera RJ, Jr., Rinzel J, Smith JC. Models of respiratory rhythm generation in the pre-Bötzinger complex. I. Bursting pacemaker neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1999;82:382–397. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.1.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazalets JR, Borde M, Clarac F. Localization and organization of the central pattern generator for hindlimb locomotion in newborn rat. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:4943–4951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-07-04943.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowley KC, Zaporozhets E, Maclean JN, Schmidt BJ. Is NMDA receptor activation essential for the production of locomotor-like activity in the neonatal rat spinal cord? J. Neurophysiol. 2005;94:3805–3814. doi: 10.1152/jn.00016.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillner S, Wallén P. The ionic mechanisms underlying N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor-induced, tetrodotoxin-resistant membrane potential oscillations in lamprey neurons active during locomotion. Neurosci. Lett. 1985;60:289–294. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(85)90592-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann U, Pumain R. Effects of tetrodotoxin on changes in extracellular free calcium induced by repetitive electrical stimulation and iontophoretic application of excitatory amino acids in the sensorimotor cortex of cats. Neurosci. Lett. 1981;21:87–91. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(81)90063-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann U, Lux HD, Gutnick MJ. Extracellular free calcium and potassium during paroxsmal activity in the cerebral cortex of the cat. Exp. Brain Res. 1977;27:237–243. doi: 10.1007/BF00235500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann U, Schaible HG, Schmidt RF. Changes in extracellular potassium concentration in cat spinal cord in response to innocuous and noxious stimulation of legs with healthy and inflamed knee joints. Exp. Brain Res. 1990;79:283–292. doi: 10.1007/BF00608237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochman S, Jordan LM, Schmidt BJ. TTX-resistant NMDA receptor-mediated voltage oscillations in mammalian lumbar motoneurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2559–2562. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.5.2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao CF, Wu N, Levine MS, Chandler SH. Development and serotonergic modulation of NMDA bursting in rat trigeminal motoneurons. J. Neurophysiol. 2002;87:1318–1328. doi: 10.1152/jn.00469.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jendelová P, Syková E. Role of glia in K+ and pH homeostasis in the neonatal rat spinal cord. Glia. 1991;4:56–63. doi: 10.1002/glia.440040107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SM, Smith JC, Funk GD, Feldman JL. Pacemaker behavior of respiratory neurons in medullary slices from neonatal rat. J. Neurophysiol. 1994;72:2598–2608. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.6.2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn O, Johnson BR, Raastad M. Plateau properties in mammalian spinal interneurons during transmitter-induced locomotor activity. Neuroscience. 1996;75:263–273. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(96)00250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiehn O, Dougherty KJ, Hägglund M, Borgius L, Talpalar A, Restrepo CE. Probing spinal circuits controlling walking in mammals. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;396:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjaerulff O, Kiehn O. Distribution of networks generating and coordinating locomotor activity in the neonatal rat spinal cord in vitro: a lesion study. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:5777–5794. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05777.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kríz N, Syková E, Ujec E, Vyklický L. Changes of extracellular potassium concentration induced by neuronal activity in the sinal cord of the cat. J. Physiol. 1974;238:1–15. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan AC, Dietz SB, Webb WW, Harris-Warrick RM. Activity of Hb9 interneurons during fictive locomotion in mouse spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:11601–11613. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1612-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WC, Roberts A, Soffe SR. Specific brainstem neurons switch each other into pacemaker mode to drive movement by activating NMDA receptors. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:16609–16620. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3695-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lothman EW, Somjen GG. Extracellular potassium activity, intracellular and extracellular potential responses in the spinal cord. J. Physiol. 1975;252:115–136. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1975.sp011137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti C, Beato M, Nistri A. Evidence for increased extracellular K(+) as an important mechanism for dorsal root induced alternating rhythmic activity in the neonatal rat spinal cord in vitro. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;304:77–80. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01777-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marder E, Bucher D. Central pattern generators and the control of rhythmic movements. Curr. Biol. 2001;11:R986–R996. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00581-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrea DA, Rybak IA. Modeling the mammalian locomotor CPG: insights from mistakes and perturbations. Prog. Brain Res. 2007;165:235–253. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)65015-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson C, ten Bruggencate G, Stöckle H, Steinberg R. Calcium and potassium changes in extracellular microenvironment of cat cerebellar cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 1978;41:1026–1039. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.4.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace RW, Mackay DD, Feldman JL, Del Negro CA. Role of persistent sodium current in mouse preBötzinger Complex neurons and respiratory rhythm generation. J. Physiol. 2007;580:485–496. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton JF, Abdala AP, Koizumi H, Smith JC, St-John WM. Respiratory rhythm generation during gasping depends on persistent sodium current. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:311–313. doi: 10.1038/nn1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybak IA, Shevtsova NA, St-John WM, Paton JF, Pierrefiche O. Endogenous rhythm generation in the pre-Bötzinger complex and ionic currents: modelling and in vitro studies. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003;18:239–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybak IA, Stecina K, Shevtsova NA, McCrea DA. Modelling spinal circuitry involved in locomotor pattern generation: insights from the effects of afferent stimulation. J. Physiol. 2006;577:641–658. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.118711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryczko D, Charrier V, Ijspeert A, Cabelguen JM. Segmental oscillators in axial motor circuits of the salamander: distribution and bursting mechanisms. J. Neurophysiol. 2010;104:2677–2692. doi: 10.1152/jn.00479.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su H, Alroy G, Kirson ED, Yaari Y. Extracellular calcium modulates persistent sodium current-dependent burst-firing in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J. Neurosci. 2001;21:4173–4182. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04173.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syková E. Modulation of spinal cord transmission by changes in extracellular K+ activity and extracellular volume. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1987;65:1058–1066. doi: 10.1139/y87-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talpalar AE, Endo T, Löw P, Borgius L, Hägglund M, Dougherty KJ, Ryge J, Hnasko TS, Kiehn O. Identification of minimal neuronal networks involved in flexor-extensor alternation in the mammalian spinal cord. Neuron. 2011;71:1071–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazerart S, Viemari JC, Darbon P, Vinay L, Brocard F. Contribution of persistent sodium current to locomotor pattern generation in neonatal rats. J. Neurophysiol. 2007;98:613–628. doi: 10.1152/jn.00316.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazerart S, Vinay L, Brocard F. The persistent sodium current generates pacemaker activities in the central pattern generator for locomotion and regulates the locomotor rhythm. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:8577–8589. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1437-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoby-Brisson M, Ramirez JM. Identification of two types of inspiratory pacemaker neurons in the isolated respiratory neural network of mice. J. Neurophysiol. 2001;86:104–112. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargová L, Jendelová P, Chvátal A, Syková E. Glutamate, NMDA, and AMPA induced changes in extracellular space volume and tortuosity in the rat spinal cord. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2001;21:1077–1089. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200109000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallén P, Grafe P, Grillner S. Phasic variations of extracellular potassium during fictive swimming in the lamprey spinal cord in vitro. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1984;120:457–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1984.tb07406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton KD, Chesler M. Activity-related extracellular potassium transients in the neonatal rat spinal cord: an in vitro study. Neuroscience. 1988;25:983–995. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong G, Masino MA, Harris-Warrick RM. Persistent sodium currents participate in fictive locomotion generation in neonatal mouse spinal cord. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:4507–4518. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0124-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziskind-Conhaim L, Wu L, Wiesner EP. Persistent sodium current contributes to induced voltage oscillations in locomotor-related hb9 interneurons in the mouse spinal cord. J. Neurophysiol. 2008;100:2254–2264. doi: 10.1152/jn.90437.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.