Abstract

Biological regulatory systems face a fundamental tradeoff: they must be effective but at the same time also economical. For example, regulatory systems that are designed to repair damage must be effective in reducing damage, but economical in not making too many repair proteins because making excessive proteins carries a fitness cost to the cell, called protein burden. In order to see how biological systems compromise between the two tasks of effectiveness and economy, we applied an approach from economics and engineering called Pareto optimality. This approach allows calculating the best-compromise systems that optimally combine the two tasks. We used a simple and general model for regulation, known as integral feedback, and showed that best-compromise systems have particular combinations of biochemical parameters that control the response rate and basal level. We find that the optimal systems fall on a curve in parameter space. Due to this feature, even if one is able to measure only a small fraction of the system's parameters, one can infer the rest. We applied this approach to estimate parameters in three biological systems: response to heat shock and response to DNA damage in bacteria, and calcium homeostasis in mammals.

Author Summary

Many systems in the cell work to keep homeostasis, or balance. For example, damage repair systems make special repair proteins to resolve damage. These systems typically have many biochemical parameters such as biochemical rate constants, and it is not clear how much of the huge parameter space is filled by actual biological systems. We examined how natural selection acts on these systems when there are two important tasks: effectiveness – rapidly repairing damage, and economy – avoiding excessive production of repair proteins. We find that this multi-task optimization situation leads to natural selection of circuits that lie on a curve in parameter space. Thus, most of parameter space is empty. Estimating only a few parameters of the circuit is enough to predict the rest. This approach allowed us to estimate parameters for bacterial heat shock and DNA repair systems, and for a mammalian hormone system responsible for calcium homeostasis.

Introduction

Biological networks have been shown to be composed of a small set of recurring interaction patterns, called network motifs [1]–[6]. Each motif is a small circuit element that can carry out specific dynamical functions. An organism often shows hundreds or thousands of instances of each network motif, each time with different genes or proteins.

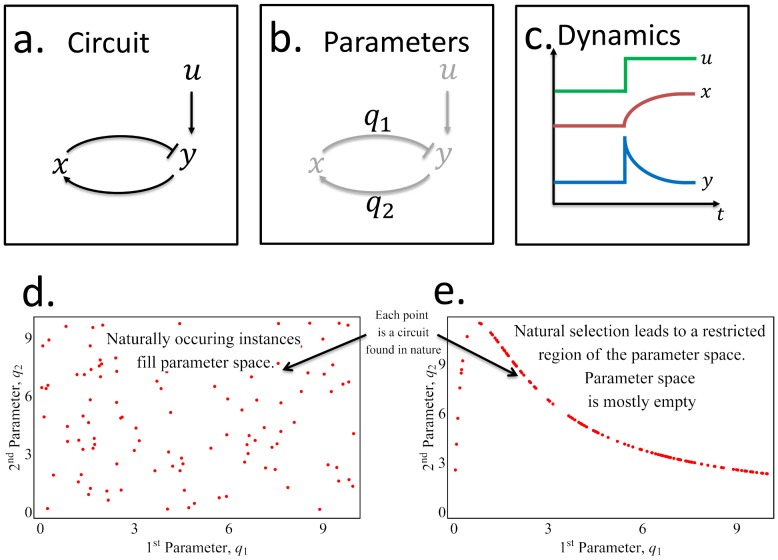

Qualitative aspects of the dynamics of each network motif are usually determined by their connectivity pattern - the arrows in the circuit diagram (Fig. 1a). However, in order to understand the detailed dynamics of a network motif, one needs to also know its biochemical parameters – the numbers on the arrows (Figs. 1b and 1c). If a given circuit has  biochemical parameters, every instance of the circuit can be described by a point in an

biochemical parameters, every instance of the circuit can be described by a point in an  -dimensional parameter space. Parameter space has been useful in theoretical studies that explore the range of dynamics accessible by a particular circuit, by sampling many points (many parameter combinations) and studying the dynamics of the resulting circuits [7]–[11]. Note that when the number of parameter is large, scanning the parameter space is a combinatorially difficult task.

-dimensional parameter space. Parameter space has been useful in theoretical studies that explore the range of dynamics accessible by a particular circuit, by sampling many points (many parameter combinations) and studying the dynamics of the resulting circuits [7]–[11]. Note that when the number of parameter is large, scanning the parameter space is a combinatorially difficult task.

Figure 1. In nature, the parameters that determine the dynamics of a circuit may fill the parameter space uniformly or, instead, lie in a confined manifold within parameter space.

(a) A schematic diagram of a circuit whose parameters,  and

and  (b) determine the dynamics (c) of the internal variable (

(b) determine the dynamics (c) of the internal variable ( , red) and the output (

, red) and the output ( , blue) for a given input time series (

, blue) for a given input time series ( , green). Two schematic illustrations of possible scenarios that could exist in nature are (d) the occurrences of the circuit fill parameter space or (e) the occurrences of the circuit are confined to a curve or manifold in parameter space. Natural selection in the context of tradeoffs can effectively remove points from (d), resulting in (e).

, green). Two schematic illustrations of possible scenarios that could exist in nature are (d) the occurrences of the circuit fill parameter space or (e) the occurrences of the circuit are confined to a curve or manifold in parameter space. Natural selection in the context of tradeoffs can effectively remove points from (d), resulting in (e).

An open question concerns the distribution of naturally occurring instances of a circuit in parameter space. One may imagine different scenarios: instances of the circuit may be distributed widely over parameter space (Fig. 1d), or, instead, be localized to a low-dimensional manifold within this space (Fig. 1e). The latter situation would be helpful because all the parameters of the circuit could then be derived from the estimate of only a small subset of parameters.

Recently, an analogous question has been posed for animal morphology, in which each organism is represented by a point in a space of traits [12], [13], called morphospace [14]. Animal morphology usually fills only a small part of morphospace. The range of morphology in a class of species – called the suite of variation- often falls on a line in morphospace. One theoretical explanation for such lines is that organisms need to perform different tasks, and thus face a fundamental tradeoff: No single phenotype (no point in trait space) can be optimal at all tasks. Shoval et al. [12] showed, using the concept of Pareto optimality [15]–[17], that tradeoffs often lead natural selection to phenotypes arranged on low dimensional regions in morphospace, such as lines and triangles. The vertices of these lines and triangles are phenotypes optimal at a single task, called archetypes.

Biological circuits also face multiple tasks [18]–[26]. For example they must effectively carry out a given function, but they must also economize the levels of the proteins made by the cell because unneeded proteins carry a fitness cost [27]–[32]. This tradeoff between economy and effectiveness in circuits, described by El Samad et al. [33], raises the possibility that a similar Pareto front analysis may be useful to analyze the distribution of the biochemical parameters of a circuit in parameter space.

Here, we apply such an analysis to a simple circuit, in order to exemplify an approach to study how tradeoff between tasks can lead evolved circuits to low-dimensional regions of parameter space. As a model system we study a circuit known as integral feedback- which serves as a simple model of a wide range of systems that govern physiological homeostasis, and is a mainstay of engineering feedback control. The circuit has two components (Fig. 2a): an internal variable  and an output

and an output  . In response to an input,

. In response to an input,  , the level of

, the level of  changes from its set point

changes from its set point  . As a result,

. As a result,  levels change slowly, causing

levels change slowly, causing  to return to

to return to  . The defining property of integral feedback is that the rate of change of

. The defining property of integral feedback is that the rate of change of  is proportional to the difference between

is proportional to the difference between  and its set-point

and its set-point  , a mathematical feature that guarantees exact return to

, a mathematical feature that guarantees exact return to  no matter what the model parameters are [34], [35].

no matter what the model parameters are [34], [35].

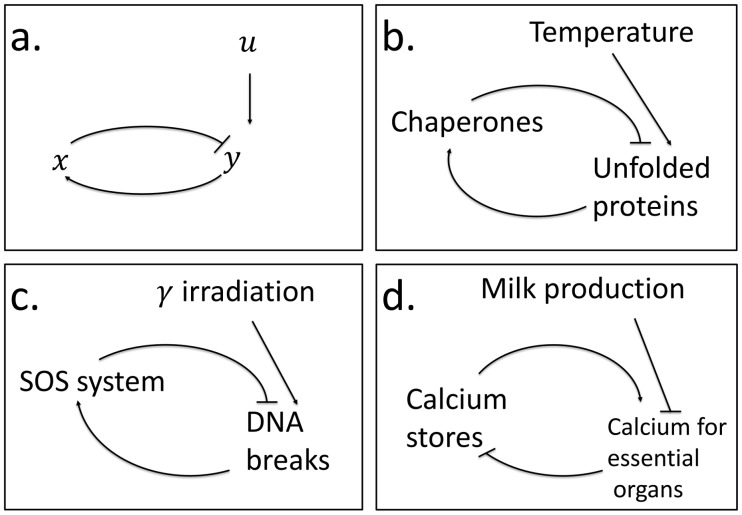

Figure 2. An integral feedback model for damage response and homeostasis systems.

(a) An increase of the input,  , leads to a rise in the level of the output,

, leads to a rise in the level of the output,  , which, in turn triggers the production of the internal variable,

, which, in turn triggers the production of the internal variable,  , that lowers the output back to its original level. This feedback loop is at the heart of systems such as (b) the E. coli heat shock system - where the input is temperature, the internal variable is the amount of chaperones and the output is the level of unfolded proteins; and (c) the E coli SOS DNA repair system where the input is DNA damaging agents such as

, that lowers the output back to its original level. This feedback loop is at the heart of systems such as (b) the E. coli heat shock system - where the input is temperature, the internal variable is the amount of chaperones and the output is the level of unfolded proteins; and (c) the E coli SOS DNA repair system where the input is DNA damaging agents such as  irradiation, the internal variable is DNA repair machinery and the output is the level of DNA damage. Another example is the regulation of the levels of calcium in the dairy cow (d) where the input is the calcium needed for milk production per day, the internal variable is calcium flux that goes into the blood from food, bone and other stores, and the output is flux of calcium that leaves the blood per day and is required for the activities of essential organs, such as heart and neurons.

irradiation, the internal variable is DNA repair machinery and the output is the level of DNA damage. Another example is the regulation of the levels of calcium in the dairy cow (d) where the input is the calcium needed for milk production per day, the internal variable is calcium flux that goes into the blood from food, bone and other stores, and the output is flux of calcium that leaves the blood per day and is required for the activities of essential organs, such as heart and neurons.

As an example, consider the bacterial heat-shock system (Fig. 2b): unfolded proteins,  , result from changes in temperature

, result from changes in temperature  . The heat shock proteins - chaperones and proteases, collectively described by

. The heat shock proteins - chaperones and proteases, collectively described by  , increase in level until unfolded proteins

, increase in level until unfolded proteins  return to baseline. Integral feedback has also been proposed to describe the dynamics of DNA repair [36]–[38] and hormonal systems [35]. A detailed model of the bacterial heat shock system was previously studied by [33], suggesting that the parameters of the E. coli heat shock system are Pareto optimal with respect to effectiveness and economy. As in most studies that employ the Pareto front, the analysis of El Samad was in performance space. In the present study, we analyze the shape of the Pareto front in parameter space. We use a much simpler model, which has the drawback of neglecting many biological details such as non-linearity, but has the virtue of being analytically solvable and thus the shape of the Pareto front in parameter space can be solved exactly. We apply this analysis also to hormonal control and bacterial DNA repair systems. We find that natural selection with two objectives of effectiveness and economy can lead integral feedback circuits to a one-dimensional manifold in parameter space. This manifold can help to estimate difficult-to-measure parameters in each system.

return to baseline. Integral feedback has also been proposed to describe the dynamics of DNA repair [36]–[38] and hormonal systems [35]. A detailed model of the bacterial heat shock system was previously studied by [33], suggesting that the parameters of the E. coli heat shock system are Pareto optimal with respect to effectiveness and economy. As in most studies that employ the Pareto front, the analysis of El Samad was in performance space. In the present study, we analyze the shape of the Pareto front in parameter space. We use a much simpler model, which has the drawback of neglecting many biological details such as non-linearity, but has the virtue of being analytically solvable and thus the shape of the Pareto front in parameter space can be solved exactly. We apply this analysis also to hormonal control and bacterial DNA repair systems. We find that natural selection with two objectives of effectiveness and economy can lead integral feedback circuits to a one-dimensional manifold in parameter space. This manifold can help to estimate difficult-to-measure parameters in each system.

Results

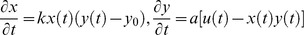

Integral feedback as a simple model for biological damage response and homeostasis systems

As a model system, we choose a well-studied class of circuits that are used to maintain homeostasis. To capture the essential behavior of these systems, we follow the models proposed by [35], [39]. These authors described the calcium and heat shock systems at various levels of detail, showing that they are essentially integral feedback loops. Here we use the simplest possible linear description of this feedback loop, ignoring important details (such as feed-forward control and non-linearity which will be treated in later sections) in order to gain clarity for analysis.

The integral feedback loop has three components. The input signal  causes a change in output

causes a change in output  (e.g. temperature

(e.g. temperature  causes increase in unfolded proteins

causes increase in unfolded proteins  ). The internal variable

). The internal variable  acts to reverse the effect of the input, so that

acts to reverse the effect of the input, so that  returns to its baseline level (e.g.

returns to its baseline level (e.g.  are heat shock proteins that cause unfolded proteins

are heat shock proteins that cause unfolded proteins  to return to a basal level). We describe these effects by a linear equation:

to return to a basal level). We describe these effects by a linear equation:

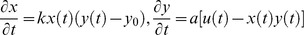

| (1) |

Feedback in these systems occurs because an increase in  leads to production of

leads to production of  , causing

, causing  to return to its basal levels. Integral feedback is a specific form of feedback, in which the rate of production of

to return to its basal levels. Integral feedback is a specific form of feedback, in which the rate of production of  is dependent on the difference between the level of output

is dependent on the difference between the level of output  and its desired basal level

and its desired basal level  :

:

| (2) |

The time constant for this process is  . The larger

. The larger  , the faster

, the faster  responds when

responds when  departs from its baseline

departs from its baseline  . The only possible steady-state for

. The only possible steady-state for  is when

is when  . For this reason, integral feedback is a robust circuit that leads the output to its baseline, regardless of parameter values.

. For this reason, integral feedback is a robust circuit that leads the output to its baseline, regardless of parameter values.

Note that we used the separation of timescales that occurs in the biological examples, in order to simplify the mathematical description: the production of  is typically much slower than the action of

is typically much slower than the action of  and

and  on

on  . Thus, Eq 2 is a differential equation; whereas equation 1 is algebraic.

. Thus, Eq 2 is a differential equation; whereas equation 1 is algebraic.

In order to reduce the number of free parameters in the model, we rescale the variables. We normalize  and

and  by the parameter

by the parameter  (

( ,

, ),

),  by

by  (

( ). We normalize time by the typical timescale

). We normalize time by the typical timescale  over which the system is activated, There remain only two scaled parameters,

over which the system is activated, There remain only two scaled parameters,  and

and  . Thus we will work with the rescaled model (Fig. 2)

. Thus we will work with the rescaled model (Fig. 2)

| (3) |

| (4) |

The parameter space for this model is two dimensional, with axes of  and

and  , corresponding to the responsiveness rate of

, corresponding to the responsiveness rate of  and the baseline level of

and the baseline level of  . Each choice of

. Each choice of  and

and  determines a particular dynamical system, which has its own characteristic dynamic response to a given change in input

determines a particular dynamical system, which has its own characteristic dynamic response to a given change in input  . Note that the time is now measured in units of

. Note that the time is now measured in units of  .

.

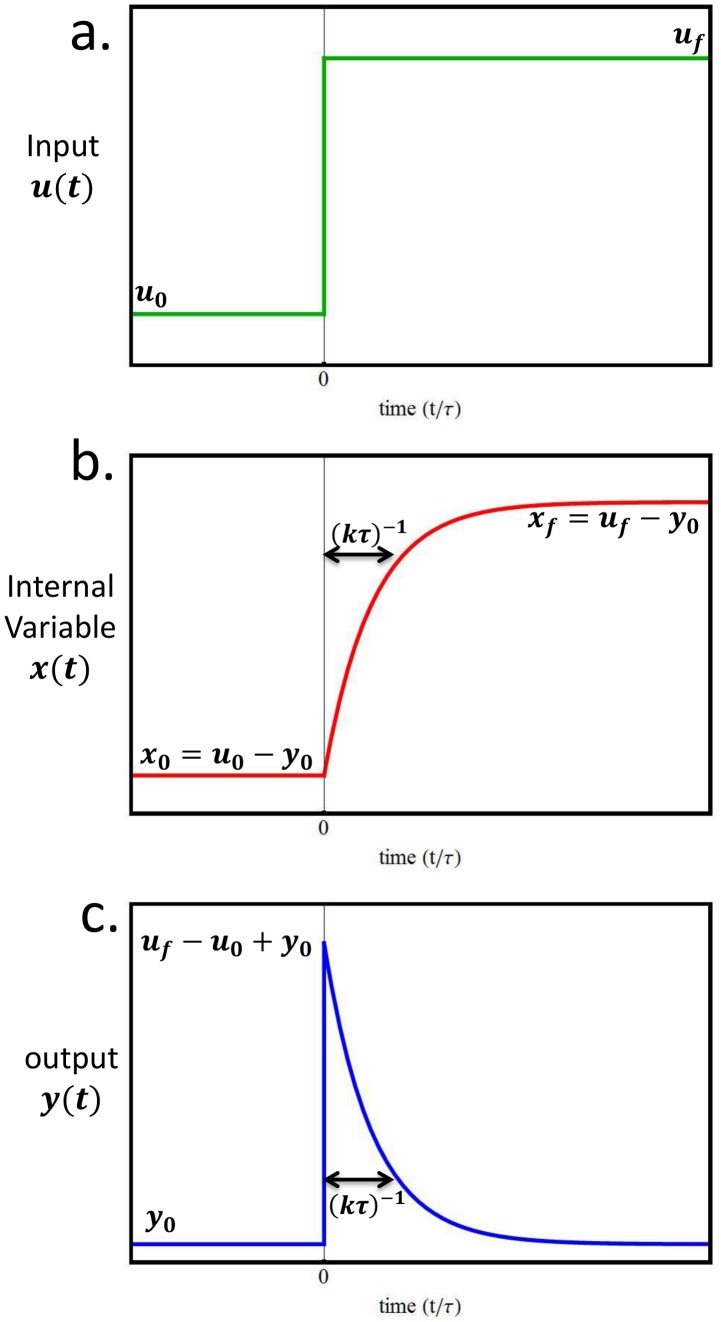

In Fig. 3 we plot the response of the integral feedback system to a step change in input that goes from an initial level  to a final level

to a final level  , at time

, at time  . An advantage of this model is that the dynamics can be solved analytically. The internal variable

. An advantage of this model is that the dynamics can be solved analytically. The internal variable  rises and exponentially approaches its new steady state

rises and exponentially approaches its new steady state

| (5) |

Figure 3. Dynamics of the integral feedback model show exact adaptation following a step change in input.

(a) A step of input at  leads to (b) an increase in the internal variable level,

leads to (b) an increase in the internal variable level,  . The parameter

. The parameter  determines the rate of response. (c) The output

determines the rate of response. (c) The output  increases rapidly due to the input step, and decreases back to its baseline level

increases rapidly due to the input step, and decreases back to its baseline level  due to the action of

due to the action of  .

.

The output  responds immediately, reaching a maximal level

responds immediately, reaching a maximal level  . The output

. The output  then decays due to the rise in

then decays due to the rise in  , eventually returning precisely to its initial level, the baseline level

, eventually returning precisely to its initial level, the baseline level

| (6) |

The timescale of changes in both  and

and  is

is  .

.

Tasks for an integral feedback system include economy and effectiveness

We define two tasks for the integral feedback system, following [33]. The first task is effectiveness, namely minimizing the ‘damage’  . In a damage response system, the more effective the circuit, the less the average output

. In a damage response system, the more effective the circuit, the less the average output  , because

, because  causes damage to the cell, and lower values of

causes damage to the cell, and lower values of  mean higher fitness. The second task is economy: the less of the proteins

mean higher fitness. The second task is economy: the less of the proteins  are made, the higher the fitness due to reduced protein burden [27]–[29]. There is a tradeoff inherent in these two tasks: effective systems require high levels of

are made, the higher the fitness due to reduced protein burden [27]–[29]. There is a tradeoff inherent in these two tasks: effective systems require high levels of  , while economizing systems require low levels of

, while economizing systems require low levels of  . Thus, natural selection needs to compromise between effectiveness and economy.

. Thus, natural selection needs to compromise between effectiveness and economy.

We consider a case where the system is at steady state for a time  , and then a step change in input occurs that lasts for time

, and then a step change in input occurs that lasts for time  (for example, ambient temperature for time

(for example, ambient temperature for time  , followed by temperature increase for time

, followed by temperature increase for time  ). A simple choice for a performance function for the task of effectiveness,

). A simple choice for a performance function for the task of effectiveness,  , is the average output over time

, is the average output over time

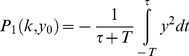

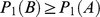

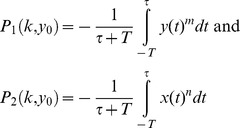

|

(7) |

And for economy, described by the performance function,  , the average of

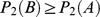

, the average of  over time

over time

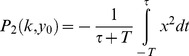

|

(8) |

We use quadratic terms,  and

and  , because biological cost is often an accelerating function of the cost-inducing factor [29], and because of the ease of analytical solutions [23]. Other functional forms for the performance functions lead to similar conclusions and will be discussed below.

, because biological cost is often an accelerating function of the cost-inducing factor [29], and because of the ease of analytical solutions [23]. Other functional forms for the performance functions lead to similar conclusions and will be discussed below.

The performance functions depend on the two circuit parameters  and

and  : for each choice of

: for each choice of  , one computes the dynamics for a given step increase in input (from

, one computes the dynamics for a given step increase in input (from  to

to  ), plug the dynamics

), plug the dynamics  and

and  into equations 7 and 8, and computes the performances – effectiveness and economy- that characterize that point in parameter space. Analytical solutions for these equations are provided in Methods.

into equations 7 and 8, and computes the performances – effectiveness and economy- that characterize that point in parameter space. Analytical solutions for these equations are provided in Methods.

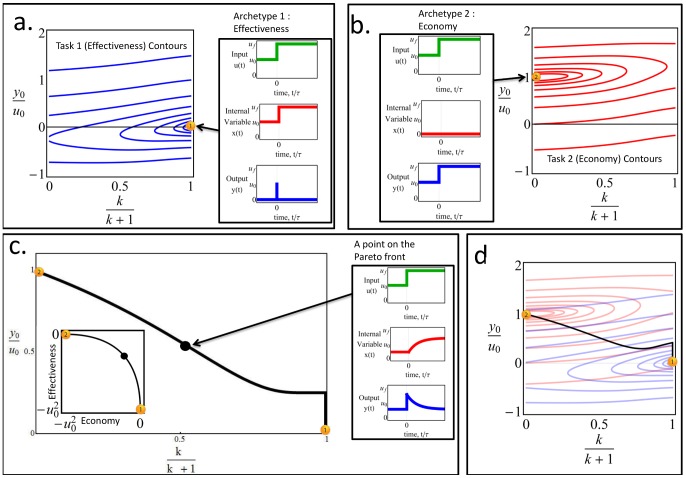

In Fig. 4a, we plot the contours of effectiveness in parameter space- lines of equal  Parameter space is plotted with

Parameter space is plotted with  on one axis, and

on one axis, and  on the other axis. The latter is a way to present an infinite range of

on the other axis. The latter is a way to present an infinite range of  in a compact way (

in a compact way ( means

means  ).

).

Figure 4. The Pareto front connects the archetypes – systems which are optimal for only one of the two tasks.

The effectiveness (a) and economy (b) contours radiate outwards from the archetypes, which have their dynamics described in adjacent boxes ( ). (c) The Pareto front is the set of points where the contours of the two performance functions are externally tangent. The plot shows the Pareto front when input changes are rare, that is

). (c) The Pareto front is the set of points where the contours of the two performance functions are externally tangent. The plot shows the Pareto front when input changes are rare, that is  . The Pareto front is a curve that connects the two archetypes. In the inset the Pareto front in performance space- note that axes are the effectiveness and economy, not the biochemical parameters as in parameter space of (a)–(c). The archetypes have the maximal performance in their respective tasks. An analytical solution shows the front is a parabola in performance space (see Methods). (d) the overlay of the contours of (a) and (b), and the resulting Pareto front (See Fig. 6 for further details).

. The Pareto front is a curve that connects the two archetypes. In the inset the Pareto front in performance space- note that axes are the effectiveness and economy, not the biochemical parameters as in parameter space of (a)–(c). The archetypes have the maximal performance in their respective tasks. An analytical solution shows the front is a parabola in performance space (see Methods). (d) the overlay of the contours of (a) and (b), and the resulting Pareto front (See Fig. 6 for further details).

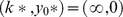

Effectiveness ( ) is maximized at a point that can be called the effectiveness archetype, at

) is maximized at a point that can be called the effectiveness archetype, at  . This archetype system is an extreme (limiting) case in which economy does not factor at all into consideration. It has an infinitely brief rise in

. This archetype system is an extreme (limiting) case in which economy does not factor at all into consideration. It has an infinitely brief rise in  after a step change in the input, caused by an infinitely rapid increase in

after a step change in the input, caused by an infinitely rapid increase in  . This archetype effectively makes an infinite amount of

. This archetype effectively makes an infinite amount of  in order to speed the return of

in order to speed the return of  to the baseline. Contours of performance at task 1 radiate around the archetype in elongated rings (Fig. 4a).

to the baseline. Contours of performance at task 1 radiate around the archetype in elongated rings (Fig. 4a).

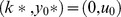

Economy ( ) is maximized at a different point, the economy archetype (archetype 2), at

) is maximized at a different point, the economy archetype (archetype 2), at  . This too is an extreme case where effectiveness is not a consideration. Here no

. This too is an extreme case where effectiveness is not a consideration. Here no  is produced at all (so that economy is maximal). As a result,

is produced at all (so that economy is maximal). As a result,  responds in an unmitigated way to the change in input, without returning to baseline. In effect, this archetype is akin to a loss of the response system

responds in an unmitigated way to the change in input, without returning to baseline. In effect, this archetype is akin to a loss of the response system  . Contours of decreasing economy (increasing

. Contours of decreasing economy (increasing  ) surround the archetype in elongated rings (Fig. 4b).

) surround the archetype in elongated rings (Fig. 4b).

The Pareto front is a curve in parameter space that best compromises between the tasks

We next computed the Pareto front [12], [20], [40]–[42], defined as follows. We term point  in parameter space as dominated by point

in parameter space as dominated by point  if the performance in both task 1 and 2 is better at

if the performance in both task 1 and 2 is better at  than in

than in  (that is

(that is  and

and  ). Because biological fitness is an increasing function of

). Because biological fitness is an increasing function of  and of

and of  , point

, point  has higher fitness than point

has higher fitness than point  . As a result, natural selection would tend to select against systems at point

. As a result, natural selection would tend to select against systems at point  , and they would vanish from the population. The Pareto front is the set of points that remains after all points dominated by another point are removed. The Pareto front thus represents the maximal set of phenotypes that will be found given that natural selection is the main force at play.

, and they would vanish from the population. The Pareto front is the set of points that remains after all points dominated by another point are removed. The Pareto front thus represents the maximal set of phenotypes that will be found given that natural selection is the main force at play.

The Pareto front is a powerful concept because it does not require knowledge of the precise shape of the fitness function, as long as fitness is an increasing function of both performances. The exact shape of the fitness function,  determines which point along the front is selected.

determines which point along the front is selected.

We calculated the Pareto front in parameter space [20], [43], [44] (Fig. 4d). For this purpose, we used the fact that the Pareto front is the locus of points at which the contours of the two performance functions are externally tangent [12], [13]. This allowed an analytical solution of the front (see Methods). We tested the analytical solution by numerical simulations in which points dominated by other points were removed in evolutionary simulations (see Methods).

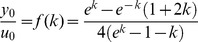

We find that the Pareto front, in the case where input changes are rare  , is a curve that connects the two archetypes (Fig. 4c). Its formula is

, is a curve that connects the two archetypes (Fig. 4c). Its formula is  . Thus, most of parameter space is predicted by this theory to be empty, and natural systems are expected to fall on a curve. Interestingly, the front does not depend on the final input value in the step,

. Thus, most of parameter space is predicted by this theory to be empty, and natural systems are expected to fall on a curve. Interestingly, the front does not depend on the final input value in the step,  , but only on the ambient input

, but only on the ambient input  (See Methods). When effectiveness is more impactful for fitness than economy

(See Methods). When effectiveness is more impactful for fitness than economy  , systems should lie on the front closer to the effectiveness archetype - with lower baseline

, systems should lie on the front closer to the effectiveness archetype - with lower baseline  and faster responsiveness

and faster responsiveness  . When economy is more impactful for fitness, systems should lie on the front closer to economy archetype, with higher baseline

. When economy is more impactful for fitness, systems should lie on the front closer to economy archetype, with higher baseline  , and slower responsiveness (lower

, and slower responsiveness (lower  ).

).

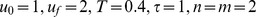

We tested the sensitivity of the Pareto front to variations in the form of the performance functions (Fig. 5). We tested

|

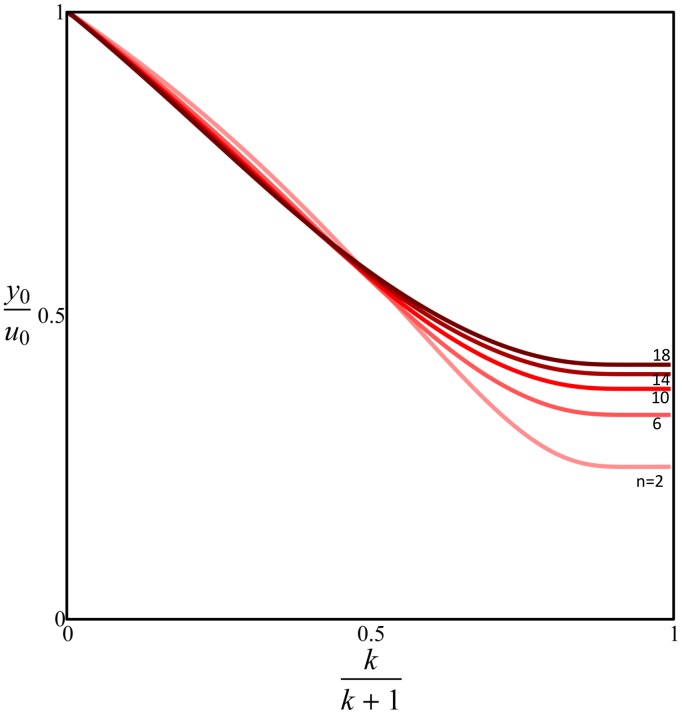

Figure 5. Altering the mathematical description of the performance functions does not cause substantial difference in the Pareto front shape.

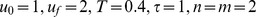

We changed the integrand power in both tasks from 2 to  (equations 7 and 8). The calculated front uses

(equations 7 and 8). The calculated front uses  (method).

(method).

We find that changing the powers  and

and  between 1 and

between 1 and  had only minor effects on the shape of the front. The higher

had only minor effects on the shape of the front. The higher  or

or  , the higher the baseline value

, the higher the baseline value  of the effectiveness end of the front. The front is insensitive to performance function shape at the economy end. We also tested other functional forms of the performance functions and find similar insensitivity of the front shape (Fig. S1 and S2).

of the effectiveness end of the front. The front is insensitive to performance function shape at the economy end. We also tested other functional forms of the performance functions and find similar insensitivity of the front shape (Fig. S1 and S2).

We also tested the sensitivity of this analysis to changes in the integral-feedback model itself. We added feed-forward control, known to occur in the bacterial heat shock system, by changing the parameter  into

into  , allowing the input

, allowing the input  to directly affect the internal variable,

to directly affect the internal variable,  . This describes the effect of input signal on the responsiveness of

. This describes the effect of input signal on the responsiveness of  . Since we consider step changes in

. Since we consider step changes in  , the present analysis applies precisely to this case as well, when one adjusts

, the present analysis applies precisely to this case as well, when one adjusts  by the value of

by the value of  . The resulting Pareto front is identical to Fig. 5, with appropriate change of

. The resulting Pareto front is identical to Fig. 5, with appropriate change of  to

to  . We also tested the model by adding non-linearity to the equations, and by removing the assumption of separation of timescales between

. We also tested the model by adding non-linearity to the equations, and by removing the assumption of separation of timescales between  and

and  . The results are detailed in Fig. S3, and generally show that the qualitative conclusions of a Pareto front curve, which connects the two archetypes and is insensitive to the form of the performance functions, remain valid.

. The results are detailed in Fig. S3, and generally show that the qualitative conclusions of a Pareto front curve, which connects the two archetypes and is insensitive to the form of the performance functions, remain valid.

It is likely that many damage response systems evolve in the limit when input changes are relatively rare  . For completeness, we also studied the Pareto front when changes in input are more frequent (

. For completeness, we also studied the Pareto front when changes in input are more frequent ( comparable to

comparable to  ) (Fig. 6) [45]. In this case, unexpected complexity was found in this simple model system. As long as

) (Fig. 6) [45]. In this case, unexpected complexity was found in this simple model system. As long as  , the front is a curve resembling Fig. 5 that connects the two archetypes, with an unstable region near archetype 1, at which the front jumps to

, the front is a curve resembling Fig. 5 that connects the two archetypes, with an unstable region near archetype 1, at which the front jumps to  (Fig. 6a,b). At

(Fig. 6a,b). At  the front splits into two disjoint components, one of which is a range of

the front splits into two disjoint components, one of which is a range of  values with

values with  (Fig. 6d). At

(Fig. 6d). At  , the front splits again into two disjoint curves separated by an unstable ridge.(Fig. 6e,f).

, the front splits again into two disjoint curves separated by an unstable ridge.(Fig. 6e,f).

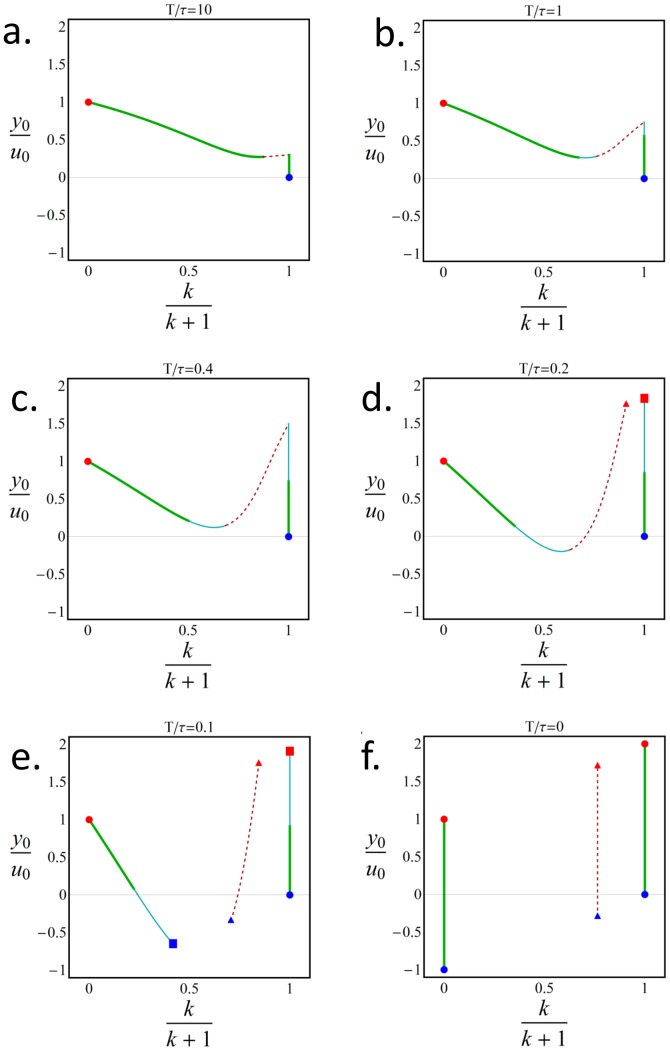

Figure 6. When input changes become frequent, the Pareto front shows complex changes in shape.

We plot the Pareto front changing the parameter  , which describes the typical duration between input changes. The archetypes of effectiveness and economy (marked in blue and red, respectively) are connected by the Pareto front (green) , which for any finite

, which describes the typical duration between input changes. The archetypes of effectiveness and economy (marked in blue and red, respectively) are connected by the Pareto front (green) , which for any finite  is split into two parts. For

is split into two parts. For  the Pareto front resembles its limit of rare input changes (a–c). As

the Pareto front resembles its limit of rare input changes (a–c). As  gets smaller a local Pareto front (cyan) emerges and a separatrix emerges (red-dashed) and grows. When

gets smaller a local Pareto front (cyan) emerges and a separatrix emerges (red-dashed) and grows. When  (d) a local minimum (square) and a saddle point (triangle) emerge for the economy task. And when

(d) a local minimum (square) and a saddle point (triangle) emerge for the economy task. And when  (e) the same occurs to the effectiveness task and the branches of the Pareto front becomes disjoint, until

(e) the same occurs to the effectiveness task and the branches of the Pareto front becomes disjoint, until  (f) where two parallel lines emerge. Red dashed lines are points where contours are tangent but are not part of the Pareto front (see methods).

(f) where two parallel lines emerge. Red dashed lines are points where contours are tangent but are not part of the Pareto front (see methods).

Heat shock, DNA repair and calcium hormone system parameters may be inferred from the Pareto front

Heat shock system

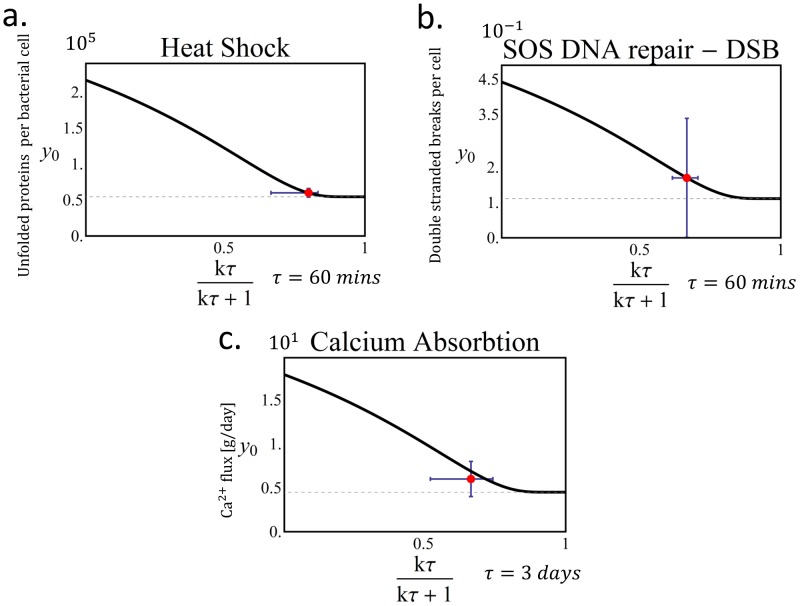

Finally, we explore the implications of the Pareto analysis for three biological examples of homeostasis systems (Table 1). We begin with the heat-shock system of E. coli. The baseline level of unfolded proteins at ambient temperature ( ) has been estimated to be about

) has been estimated to be about  [39], which amounts to about 2–3% of the total protein in a growing cell. The responsiveness parameter of the system,

[39], which amounts to about 2–3% of the total protein in a growing cell. The responsiveness parameter of the system,  , can be estimated from the typical timescale at which unfolded proteins are removed by the heat-shock system, which is about

, can be estimated from the typical timescale at which unfolded proteins are removed by the heat-shock system, which is about  [39]. Considering the dynamics over a cell generation time, so that

[39]. Considering the dynamics over a cell generation time, so that  =

=  , yields

, yields  . Plotting this point on the Pareto front (Fig. 7a) suggests that it lies towards the effectiveness archetype, in a relatively flat region of the front at which the value of

. Plotting this point on the Pareto front (Fig. 7a) suggests that it lies towards the effectiveness archetype, in a relatively flat region of the front at which the value of  can be robustly estimated as

can be robustly estimated as  . This suggests a value of

. This suggests a value of  . This value can be interpreted to mean that without a heat-shock system, at ambient temperature, E. coli would have had

. This value can be interpreted to mean that without a heat-shock system, at ambient temperature, E. coli would have had  , amounting to about 10% of its total protein. This level agrees with the estimated lethal limit of unfolded protein [46], and with the fraction of proteins that require extra chaperone assistance to fold as they exit the ribosome [47].

, amounting to about 10% of its total protein. This level agrees with the estimated lethal limit of unfolded protein [46], and with the fraction of proteins that require extra chaperone assistance to fold as they exit the ribosome [47].

Table 1. Summary of the data used to compare to the Pareto front in Figure 7.

– input – input |

– internal variable – internal variable |

- output - output |

Units of  , ,  and and

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The heat shock system of E. coli | Temperature – The amount of unfolded proteins the system would have in the hypothetical case of having no heat shock system | Chaperones – The average amount of unfolded proteins that each unit of cell machinery folds in its lifetime | Unfolded proteins | Unfolded proteins |

typical generation time typical generation time |

Inferred [39] Inferred [39]

|

60,000 [39] | 200,000 [47] |

| Calcium blood concentration in dairy cows | Flux of calcium for milk production | Flux of calcium to the cow from bone and intestine | Flux of calcium for vital organs | g/day | 3 days [54] |

[35]

[35]

|

[55]

[55]

|

18 [54] |

| DNA SOS Repair system | Amount of DNA damage inflicted | Amount of DNA damage fixed by the system | The amount of DNA damage remaining | Double stranded breaks |

typical generation time typical generation time |

[38], [49]

[38], [49]

|

0.17 [50] | 0.44 - Fitted |

Figure 7. Parameters for three biological systems can be estimated from the Pareto front.

Three examples of biological systems that can be modeled by an integral feedback circuit agree with the model's prediction. In all, the curve is the Pareto front in the case of a rare input change; the point represents the specific values for each example. (a) in the heat Shock system (b) the DNA damage repair system of E. coli, and (c) in the regulation system of the calcium in dairy cows. Values for heat shock and calcium systems were estimated independently and showed good agreement with the theory. In the SOS DNA repair system (b) we fitted using the model the value of the basal input ( ) by knowing the time scale (

) by knowing the time scale ( ) and set-point (

) and set-point ( ) of the system, which provides an estimate of the basal level of DNA damage in the absence of a DNA repair system. In all the data sets the error bars represent different estimates of the values.

) of the system, which provides an estimate of the basal level of DNA damage in the absence of a DNA repair system. In all the data sets the error bars represent different estimates of the values.

In this example, the Pareto front allows estimation of the amount of unfolded protein expected without a heat-shock system, a value that is otherwise difficult to study because knockout of the heat shock system is lethal at ambient temperature [48].

DNA repair system

The second example is DNA damage repair in E coli. Here the timescale for the response to  irradiation, which causes double stranded DNA breaks (

irradiation, which causes double stranded DNA breaks ( ), is about 20 min [49] (similar to timescale for response to UV damage [38]). By taking

), is about 20 min [49] (similar to timescale for response to UV damage [38]). By taking  as the cell generation time, 40–60 min, we find that

as the cell generation time, 40–60 min, we find that  . The baseline level of double stranded DNA breaks is

. The baseline level of double stranded DNA breaks is  [50]. Using the Pareto front (Fig. 7b), one can estimate the level of damage expected if there was no repair system and no irradiation,

[50]. Using the Pareto front (Fig. 7b), one can estimate the level of damage expected if there was no repair system and no irradiation,  .

.

Note that detailed experiments and models of the SOS repair system and its mammalian counterpart show additional features such as multiple pulses of repair enzyme production [38], [51], [52]. These features are not accounted for in the present model. Future studies may include mutagenic repair as an additional potential task, perhaps with a new performance function  [53].

[53].

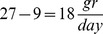

Calcium homeostasis hormonal system

The final example is control of calcium blood levels in mammals (see Methods for model). Data from dairy cows shows that after giving birth, calcium levels drop primarily due to milk production. In response, the hormones PTH and 1, 25-DHCC rise, leading to release of calcium from body stores. Calcium blood levels return to baseline exponentially with a time constant of about  [35]. In some cases, failure to recover baseline calcium levels leads to sickness (parturient paresis), which can be prevented by injecting calcium. As an estimate of

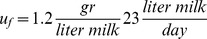

[35]. In some cases, failure to recover baseline calcium levels leads to sickness (parturient paresis), which can be prevented by injecting calcium. As an estimate of  we use

we use  , the time until an untreated cow typically shows signs of sickness [54], resulting in

, the time until an untreated cow typically shows signs of sickness [54], resulting in  . From the Pareto front, this yields

. From the Pareto front, this yields  (Fig. 7C).

(Fig. 7C).

We can compare these values to an independent estimate. We interpret  as the amount of calcium needed per day by a cow, estimated to be

as the amount of calcium needed per day by a cow, estimated to be  [55]. The extra loss of calcium due to milk production, which we interpret as

[55]. The extra loss of calcium due to milk production, which we interpret as  , is about

, is about  (

( , [56], [57]). The treatment for a cow with parturient paresis, which is caused by a failure to restore calcium levels following parturition, is to inject

, [56], [57]). The treatment for a cow with parturient paresis, which is caused by a failure to restore calcium levels following parturition, is to inject  of calcium to its blood stream [54]. Hence,

of calcium to its blood stream [54]. Hence,  is estimated to be approximately

is estimated to be approximately  . This yields

. This yields  , in reasonable agreement with the value from the Pareto front,

, in reasonable agreement with the value from the Pareto front,  .

.

Discussion

This study examined how natural selection acts on a simple biological circuit when two tasks are important: effectiveness and economy. We find that this multi-task optimization situation leads to natural selection of circuits that lie on a curve in parameter space. Thus, most of parameter space is empty. The curve is the Pareto front, composed of best-tradeoff circuits, and connects two archetype points in parameter space. These archetypes represent circuits optimized for only one of the two tasks. The simple model of the integral feedback circuit enabled analytical solution of the front shape.

The resulting Pareto front allows estimation of parameters in several example systems, bacterial heat shock and DNA repair, and mammalian calcium homeostasis. Interestingly, all three examples are in a plateau region of the Pareto front, in the side tending towards effectiveness. This may result from diminishing returns [58], in which speeding up system response (increasing  ) leads to small increase in effectiveness but a large increase in protein cost. In this plateau, a simple relation is found between the basal input and basal output,

) leads to small increase in effectiveness but a large increase in protein cost. In this plateau, a simple relation is found between the basal input and basal output,  . This means that large gains (large suppression of damage

. This means that large gains (large suppression of damage  by the basal activity of the system), are not possible, at least in this simple model. Large gains can only be reached at very large

by the basal activity of the system), are not possible, at least in this simple model. Large gains can only be reached at very large  , which may be unfeasible in terms of cost.

, which may be unfeasible in terms of cost.

Points located in other regions of the Pareto front curve are expected in organisms which have different relative fitness contributions from the two tasks. For example, Buchnera, a relative of E coli which is an obligate symbiont of termites, has a heat shock system, but its proteins do not seem to change their expression level upon heat stress [59]. In this system, economy may outweigh effectiveness, due to the rarity of heat stress in the environment in which Buchnera evolved; accordingly, a solution close to the economy archetype seems to have been selected. Throughout the Buchnera genome, evidence of economy is prevalent [60]–[63].

Previous studies of Pareto optimality of biological circuits [12], [13], [20], [21], [64], engineered circuits [65]–[67], and of metabolic fluxes [64], [68] have usually focused on performance space. El Samad et al. [33] found that the E coli heat shock system is on the Pareto front in performance space, and other studies compared different circuits theoretically in terms of hypothetical tasks in performance space [20], [21], [25]. Lan et al [24] presented a statistical-mechanics based analysis of the tradeoff in the bacterial chemotaxis between energetic cost and adaptation error. Recently, Barton and Sontag [25] analyzed the tradeoff between insulation and energetic cost of signaling . The present study computes the shape of the Pareto front of a biological circuit in parameter space, rather than performance space. This leads to the possibility of estimating difficult to measure parameters. The present study aims at categorizing best-tradeoff instances of the same circuit, rather than comparing between different circuit topologies [11], [18], [19].

Other optimization methods are also helpful in understanding tradeoffs. Variational calculus was employed to optimize temporal profiles of enzymes with respect to cost [23]. Optimal control using Pontryagin's method was applied to understand the optimal dynamics of wasp reproductive strategies [69], and the order of developmental events in the mouse intestinal crypt [70].

The conclusions of the present study can, in principle, be tested experimentally. Doing so requires measuring the parameters of a circuit accurately, a difficult task which is becoming more feasible with advances in experimental technology. It would be instructive to attempt a comparative analysis of the parameters of a given circuit in different organisms. For example, measuring  and

and  in heat shock systems or DNA repair systems in different bacterial species can test whether these systems all fall on a curve in parameters space. The position of each organism on this curve should correspond to the relative importance of effectiveness and economy in its natural environment. The present theory would be contradicted if the points fill most of parameter space, instead of falling on a curve or other low dimensional manifold.

in heat shock systems or DNA repair systems in different bacterial species can test whether these systems all fall on a curve in parameters space. The position of each organism on this curve should correspond to the relative importance of effectiveness and economy in its natural environment. The present theory would be contradicted if the points fill most of parameter space, instead of falling on a curve or other low dimensional manifold.

One such empirically discovered curve was found in the analysis of the biochemical parameters of Rubisco, an important carbon fixation enzyme. The enzyme affinities and velocity parameters from different plants and microorganisms fall on a line in a four-dimensional parameter space [71] . This may represent tradeoffs between efficiency and specificity of the enzyme.

The present study analyzed the case of two tasks. When there are a larger number of tasks, theory [12] suggests that Pareto fronts should resemble polygons whose vertices are the archetypes: points in parameter space that optimize a single task. Thus, three tasks should lead to fronts that resemble a full triangle; four tasks should lead to a tetrahedron etc. If only a single task exists, natural circuits should all fall on the same point in parameter space, the point that maximizes the task performance (and therefore maximizes fitness). Analyzing multi-task cases for biological circuits is an interesting avenue for further research. Analyzing the dynamical behavior of other common network motifs in terms of multiple tasks, such as feedforward loops [3], [4] and autoregulation [72]–[74] would be fascinating as well.

Methods

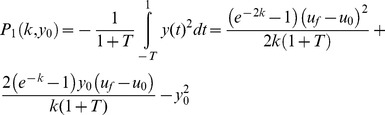

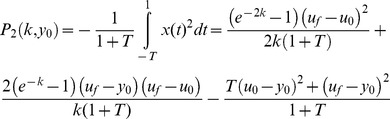

Analytical solution for performance functions

In order to find the Pareto front we first calculate the performance functions of effectiveness and economy normalizing  to be 1:

to be 1:

|

(9) |

|

(10) |

The relation between both performance functions is parabolic, and given by:

| (11) |

We searched in each of the performance functions for extremal points, by solving for when the derivative of performance functions according to  and

and  equal 0. Each point was then classified either as a maximum or a saddle point depending on the value of the determinant of the Hessian (matrix fo second derivatives). The set of equations was solved numerically. For each performance function, we find a critical value of

equal 0. Each point was then classified either as a maximum or a saddle point depending on the value of the determinant of the Hessian (matrix fo second derivatives). The set of equations was solved numerically. For each performance function, we find a critical value of  , called

, called  , at which behavior changes qualitatively (Fig. 6). When

, at which behavior changes qualitatively (Fig. 6). When  one maximum point is found, and when

one maximum point is found, and when  two maxima and one saddle point are found.

two maxima and one saddle point are found.

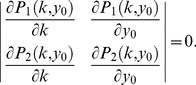

Analytical solution for the Pareto front

The Pareto front is the locus of points at which contours of the two performance functions are externally tangent, namely points  at which

at which

| (12) |

In the two dimensional case this is equivalent to solving

|

(13) |

Externally tangent points must further fulfill

| (14) |

More tests are needed in case where the tangent contours intersect at points away from the tangency point (this does not occur for the case  ).

).

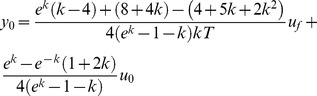

We isolate  to obtain an expression for the Pareto front:

to obtain an expression for the Pareto front:

|

(15) |

The solution corresponds to externally-tangent contours only in the region confined between the following contours in parameter space:

| (16) |

When input changes are rare,  is large (

is large ( ), and the limiting Pareto front is

), and the limiting Pareto front is

| (17) |

and is confined to the region between  and

and  . Equation 15 is confined entirely in this region.

. Equation 15 is confined entirely in this region.

Please note that the contours of the performance in the limiting case of  are all parallel to the

are all parallel to the  -axes and to each other, and thus their tangency points cannot be calculated. To calculate the Pareto front in this limit, we calculated the front at finite

-axes and to each other, and thus their tangency points cannot be calculated. To calculate the Pareto front in this limit, we calculated the front at finite  and then took the limit

and then took the limit  .

.

If the equal-performance contours of the performance functions are convex, the tangency point between them is on the Pareto front. However, in the case of finite  , some of the contours are not convex. This results in a region where contours intersect each other and change their curvature before touching each other. Hence, the resulting tangency points, that when looking locally seem like external tangency points, are actually internal tangency points. Such tangency point are dominated by other points in trait space and are not Pareto optimal. This leads to a situation where the above region that lies on the curve connecting the archetypes is not Pareto optimal. We denoted such points by red dashed lines in Fig. 6. [13].

, some of the contours are not convex. This results in a region where contours intersect each other and change their curvature before touching each other. Hence, the resulting tangency points, that when looking locally seem like external tangency points, are actually internal tangency points. Such tangency point are dominated by other points in trait space and are not Pareto optimal. This leads to a situation where the above region that lies on the curve connecting the archetypes is not Pareto optimal. We denoted such points by red dashed lines in Fig. 6. [13].

Another section marked in Fig. 6 in cyan describes points that lie on externally tangent contours, but the contours intersect each other in a different region of the parameter space, resulting in a dominance of points in the intersection region between the contours over the tangency points. Such points are said to be “locally Pareto optimal”, and the region were they lie is termed “local Pareto front”..

In order to test our analytic results, we performed simulations on a population of points evenly distributed in the parameter space [75]–[78]. For each point we calculated the two performances, and eliminated all the points that were dominated (outperformed in both tasks) by another point. We added some noise to the remaining points and repeated the comparison; we repeated this cycle several times. This helped us to overcome the effects of finite number of sampling points. The simulations were in excellent accordance with the analytical results. (Fig. S4).

Model for calcium system

In the calcium system, the dynamics are somewhat different than in the heat shock system. The sign of  (level of calcium in blood) is negative, because when

(level of calcium in blood) is negative, because when  rises (calcium demand)

rises (calcium demand)  gets smaller and

gets smaller and  (calcium flux into the blood cycle) restore the level of

(calcium flux into the blood cycle) restore the level of  back to normal, resulting in the following model:

back to normal, resulting in the following model:

| (18) |

| (19) |

The Pareto front for this model is identical to that of the model above.

Supporting Information

The basic monotonic shape of the Pareto front is robust to the value of the integrands' power of the two tasks. The gray line represent the original {n,m} = {2,2} tasks used throughout the paper, the label above each graph represent the power of the integrand of the economy and effectiveness tasks n and m, respectively,

(TIF)

When taking both integrands' powers together toward infinity, the Pareto front converges. The Pareto front for any n = m always begins from  and reaches the value in the graph as

and reaches the value in the graph as  goes to infinity.

goes to infinity.

(TIF)

The Pareto front for a case of nonlinear integral feedback with no separation of time scales. We extend the model in the main text by adding a time dependent ODE for  . In natural systems, the approximation that

. In natural systems, the approximation that  is much faster than

is much faster than  is reasonable. We also added nonlinearity in which

is reasonable. We also added nonlinearity in which  decay is multiplicative in

decay is multiplicative in  , at rate

, at rate  . This is a reasonable model of damage repair systems in which the repair proteins

. This is a reasonable model of damage repair systems in which the repair proteins  interact by mass action kinetics with the damage

interact by mass action kinetics with the damage  . This results in

. This results in  . Performance contours are in red and blue. Black lines are lines where performance contours are externally tangent. Green dots are the Pareto front according to simulations (see Fig. 4s for details). The qualitative conclusions of the main text remain valid: Pareto front is a curve that connects the economy and efficiency archetypes.

. Performance contours are in red and blue. Black lines are lines where performance contours are externally tangent. Green dots are the Pareto front according to simulations (see Fig. 4s for details). The qualitative conclusions of the main text remain valid: Pareto front is a curve that connects the economy and efficiency archetypes.

(TIF)

Simulations concur with the analytical results. Simulated data falls on the stable branches of the analytical solution for the Pareto front. Here,  . Simulation used an initial population of

. Simulation used an initial population of  randomly and uniformly distributed points. Points dominated in both tasks by other points were removed. Surviving points were perturbed by small noise (

randomly and uniformly distributed points. Points dominated in both tasks by other points were removed. Surviving points were perturbed by small noise ( ), and the process was repeated for 60 iterations, reducing the amplitude of the noise gradually to (

), and the process was repeated for 60 iterations, reducing the amplitude of the noise gradually to ( ). For comparison to Pareto simulation approaches see [75]–[78].

). For comparison to Pareto simulation approaches see [75]–[78].

(TIF)

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of our lab for discussions. We also thank Ilan Sela for the help in gathering data on cows.

Funding Statement

The research leading to these results received funding from the Israel Science Foundation (www.isf.org.il/english/) and from the European Research Council (http://erc.europa.eu/) under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013)/ERC Grant agreement number 249919. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Milo R, Shen-Orr S, Itzkovitz S, Kashtan N, Chklovskii D, et al. (2002) Network Motifs: Simple Building Blocks of Complex Networks. Science 298: 824–827 doi:10.1126/science.298.5594.824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shen-Orr SS, Milo R, Mangan S, Alon U (2002) Network motifs in the transcriptional regulation network of Escherichia coli. Nat Genet 31: 64–68 doi:10.1038/ng881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mangan S, Alon U (2003) Structure and function of the feed-forward loop network motif. PNAS 100: 11980–11985 doi:10.1073/pnas.2133841100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Alon U (2007) Network motifs: theory and experimental approaches. Nature Reviews Genetics 8: 450–461 doi:10.1038/nrg2102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kaplan S, Bren A, Dekel E, Alon U (2008) The incoherent feed-forward loop can generate non-monotonic input functions for genes. Mol Syst Biol 4: 203 doi:10.1038/msb.2008.43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Madar D, Dekel E, Bren A, Alon U (2011) Negative auto-regulation increases the input dynamic-range of the arabinose system of Escherichia coli. BMC Systems Biology 5: 111 doi:10.1186/1752-0509-5-111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alon U, Surette MG, Barkai N, Leibler S (1999) Robustness in bacterial chemotaxis. Nature 397: 168–171 doi:10.1038/16483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Eldar A, Shilo B-Z, Barkai N (2004) Elucidating mechanisms underlying robustness of morphogen gradients. Current Opinion in Genetics & Development 14: 435–439 doi:10.1016/j.gde.2004.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goentoro L, Shoval O, Kirschner MW, Alon U (2009) The Incoherent Feedforward Loop Can Provide Fold-Change Detection in Gene Regulation. Molecular Cell 36: 894–899 doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2009.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ma W, Trusina A, El-Samad H, Lim WA, Tang C (2009) Defining Network Topologies that Can Achieve Biochemical Adaptation. Cell 138: 760–773 doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Savageau MA (2011) Design of the lac gene circuit revisited. Math Biosci 231: 19–38 doi:10.1016/j.mbs.2011.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shoval O, Sheftel H, Shinar G, Hart Y, Ramote O, et al. (2012) Evolutionary Trade-Offs, Pareto Optimality, and the Geometry of Phenotype Space. Science 336: 1157–1160 doi:10.1126/science.1217405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sheftel H, Shoval O, Mayo A, Alon U (2013) The geometry of the Pareto front in biological phenotype space. Ecology and Evolution 3: 1471–1483 doi:10.1002/ece3.528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. David M Raup (1966) Geometric Analysis of Shell Coiling: General Problems. Journal of Paleontology 40: 1178–1190. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steuer RE (1986) Multiple criteria optimization: theory, computation, and application. Wiley. 574 p.

- 16.Clímaco J (1997) Multicriteria analysis. Springer-Verlag. 634 p.

- 17.Pardalos PM, Migdalas A, Pitsoulis L, editors(2008) Pareto Optimality, Game Theory and Equilibria. 2008th ed. Springer. 888 p.

- 18.Savageau MA (1976) Biochemical systems analysis: a study of function and design in molecular biology. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., Advanced Book Program. 408 p.

- 19. Savageau MA (2001) Design principles for elementary gene circuits: Elements, methods, and examples. Chaos 11: 142–159 doi:10.1063/1.1349892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Higuera C, Villaverde AF, Banga JR, Ross J, Morán F (2012) Multi-Criteria Optimization of Regulation in Metabolic Networks. PLoS ONE 7: e41122 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0041122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Warmflash A, Francois P, Siggia ED (2012) Pareto evolution of gene networks: an algorithm to optimize multiple fitness objectives. Physical Biology 9: 056001 doi:10.1088/1478-3975/9/5/056001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coello CAC (2005) Recent Trends in Evolutionary Multiobjective Optimization. In: Abraham A, Jain L, Goldberg R, editors. Evolutionary Multiobjective Optimization. Advanced Information and Knowledge Processing. Springer London. pp. 7–32. Available: http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/1-84628-137-7_2. Accessed 10 January 2013.

- 23. Reznik E, Yohe S, Segrè D (2013) Invariance and optimality in the regulation of an enzyme. Biol Direct 8: 7 doi:10.1186/1745-6150-8-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lan G, Sartori P, Neumann S, Sourjik V, Tu Y (2012) The energy-speed-accuracy tradeoff in sensory adaptation. Nat Phys 8: 422–428 doi:10.1038/nphys2276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Barton JP, Sontag ED (2013) The Energy Costs of Insulators in Biochemical Networks. Biophysical Journal 104: 1380–1390 doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2013.01.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guantes R, Estrada J, Poyatos JF (2010) Trade-offs and Noise Tolerance in Signal Detection by Genetic Circuits. PLoS ONE 5: e12314 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Koch AL (1988) Why can't a cell grow infinitely fast? Canadian Journal of Microbiology 34: 421–426 doi:10.1139/m88-074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dong H, Nilsson L, Kurland CG (1995) Gratuitous overexpression of genes in Escherichia coli leads to growth inhibition and ribosome destruction. J Bacteriol 177: 1497–1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dekel E, Alon U (2005) Optimality and evolutionary tuning of the expression level of a protein. Nature 436: 588–592 doi:10.1038/nature03842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shachrai I, Zaslaver A, Alon U, Dekel E (2010) Cost of unneeded proteins in E. coli is reduced after several generations in exponential growth. Mol Cell 38: 758–767 doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Eames M, Kortemme T (2012) Cost-Benefit Tradeoffs in Engineered lac Operons. Science 336: 911–915 doi:10.1126/science.1219083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lang GI, Murray AW, Botstein D (2009) The cost of gene expression underlies a fitness trade-off in yeast. PNAS 106: 5755–5760 doi:10.1073/pnas.0901620106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.El Samad H, Khammash M, Homescu C, Petzold L (2005) Optimal performance of the heat-shock gene regulatory network. In: Proceedings of the 16th IFAC World Congress; 4–8 July 2005. Prague, Czech Republic: Elsevier, Vol. 16. pp. 2206–2206. Available: http://www.ifac-papersonline.net/Detailed/29488.html. Accessed 9 December 2012.

- 34. Yi T-M, Huang Y, Simon MI, Doyle J (2000) Robust perfect adaptation in bacterial chemotaxis through integral feedback control. PNAS 97: 4649–4653 doi:10.1073/pnas.97.9.4649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. El Samad H, Goff JP, Khammash M (2002) Calcium Homeostasis and Parturient Hypocalcemia: An Integral Feedback Perspective. Journal of Theoretical Biology 214: 17–29 doi:10.1006/jtbi.2001.2422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rupp WD (1996) DNA Repair Mechanisms. In: Neidhardt FC, editor. Escherichia Coli and Salmonella cellular and molecular biology. Washington DC: ASM press, Vol. 2. pp. 2277–2294.

- 37.Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K, et al. (2002) DNA repair. Molecular Biology of the Cell. New York: Garland Science. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK21054/. Accessed 12 August 2012.

- 38. Friedman N, Vardi S, Ronen M, Alon U, Stavans J (2005) Precise Temporal Modulation in the Response of the SOS DNA Repair Network in Individual Bacteria. PLoS Biol 3: e238 doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. El-Samad H, Kurata H, Doyle JC, Gross CA, Khammash M (2005) Surviving heat shock: Control strategies for robustness and performance. PNAS 102: 2736–2741 doi:10.1073/pnas.0403510102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coello CAC (2003) Evolutionary Multi-Objective Optimization: A Critical Review. Evolutionary Optimization. International Series in Operations Research & Management Science. Springer US. pp. 117–146. Available: http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/0-306-48041-7_5. Accessed 23 December 2012.

- 41. Rueffler C, Hermisson J, Wagner GP (2012) Evolution of functional specialization and division of labor. PNAS 109: E326–E335 doi:10.1073/pnas.1110521109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gallagher T, Bjorness T, Greene R, You Y-J, Avery L (2013) The Geometry of Locomotive Behavioral States in C. elegans. PLoS ONE 8: e59865 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0059865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Farnsworth KD, Niklas KJ (1995) Theories of optimization, form and function in branching architecture in plants. Functional Ecology 9: 355–363. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oster GF, Wilson EO (1979) Caste and Ecology in the Social Insects. (Mpb-12). Princeton University Press. 380 p.

- 45. Kalisky T, Dekel E, Alon U (2007) Cost–benefit theory and optimal design of gene regulation functions. Physical Biology 4: 229–245 doi:10.1088/1478-3975/4/4/001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dill KA, Ghosh K, Schmit JD (2011) Physical limits of cells and proteomes. PNAS 108: 17876–17882 doi:10.1073/pnas.1114477108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Scotto-Lavino E, Bai M, Zhang Y-B, Freimuth P (2011) Export is the default pathway for soluble unfolded polypeptides that accumulate during expression in Escherichia coli. Protein Expression and Purification 79: 137–141 doi:10.1016/j.pep.2011.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kusukawa N, Yura T (1988) Heat shock protein GroE of Escherichia coli: key protective roles against thermal stress. Genes Dev 2: 874–882 doi:10.1101/gad.2.7.874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sargentini NJ, Smith KC (1992) Involvement of RecB-mediated (but not RecF-mediated) repair of DNA double-strand breaks in the gamma-radiation production of long deletions in Escherichia coli. Mutat Res 265: 83–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Robbins-Manke JL, Zdraveski ZZ, Marinus M, Essigmann JM (2005) Analysis of Global Gene Expression and Double-Strand-Break Formation in DNA Adenine Methyltransferase- and Mismatch Repair-Deficient Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 187: 7027–7037 doi:10.1128/JB.187.20.7027-7037.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Jolma IW, Ni XY, Rensing L, Ruoff P (2010) Harmonic Oscillations in Homeostatic Controllers: Dynamics of the p53 Regulatory System. Biophys J 98: 743–752 doi:10.1016/j.bpj.2009.11.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shimoni Y, Altuvia S, Margalit H, Biham O (2009) Stochastic Analysis of the SOS Response in Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 4: e5363 doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Krishna S, Maslov S, Sneppen K (2007) UV-induced mutagenesis in Escherichia coli SOS response: a quantitative model. PLoS Comput Biol 3: e41 doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aiello SE, editor(1998) The Merk veterinary manual. 8th ed. Whitehouse station: Merck & Co. 2305 p.

- 55. Luick JR, Boda JM, Kleiber M (1957) Partition of Calcium Metabolism in Dairy Cows. J Nutr 61: 597–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Lin M-J, Lewis MJ, Grandison AS (2006) Measurement of ionic calcium in milk. International Journal of Dairy Technology 59: 192–199 doi:10.1111/j.1471-0307.2006.00263.x [Google Scholar]

- 57. Halachmi I, Børsting CF, Maltz E, Edan Y, Weisbjerg MR (2011) Feed intake of Holstein, Danish Red, and Jersey cows in automatic milking systems. Livestock Science 138: 56–61 doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2010.12.001 [Google Scholar]

- 58. Tokuriki N, Jackson CJ, Afriat-Jurnou L, Wyganowski KT, Tang R, et al. (2012) Diminishing returns and tradeoffs constrain the laboratory optimization of an enzyme. Nat Commun 3: 1257 doi:10.1038/ncomms2246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wilcox JL, Dunbar HE, Wolfinger RD, Moran NA (2003) Consequences of reductive evolution for gene expression in an obligate endosymbiont. Molecular Microbiology 48: 1491–1500 doi:10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03522.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Parter M, Kashtan N, Alon U (2007) Environmental variability and modularity of bacterial metabolic networks. BMC Evolutionary Biology 7: 169 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Borenstein E, Kupiec M, Feldman MW, Ruppin E (2008) Large-scale reconstruction and phylogenetic analysis of metabolic environments. PNAS 105: 14482–14487 doi:10.1073/pnas.0806162105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. van Ham RCHJ, Kamerbeek J, Palacios C, Rausell C, Abascal F, et al. (2003) Reductive genome evolution in Buchnera aphidicola. PNAS 100: 581–586 doi:10.1073/pnas.0235981100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Thomas GH, Zucker J, Macdonald SJ, Sorokin A, Goryanin I, et al. (2009) A fragile metabolic network adapted for cooperation in the symbiotic bacterium Buchnera aphidicola. BMC Syst Biol 3: 24 doi:10.1186/1752-0509-3-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nagrath D, Avila-Elchiver M, Berthiaume F, Tilles AW, Messac A, et al. (2007) Integrated energy and flux balance based multiobjective framework for large-scale metabolic networks. Ann Biomed Eng 35: 863–885 doi:10.1007/s10439-007-9283-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Coello Coello CA, Aguirre AH (2002) Design of combinational logic circuits through an evolutionary multiobjective optimization approach. AI EDAM 16: 39–53 doi:10.1017/S0890060401020054 [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mitra K, Gopinath R (2004) Multiobjective optimization of an industrial grinding operation using elitist nondominated sorting genetic algorithm. Chemical Engineering Science 59: 385–396 doi:10.1016/j.ces.2003.09.036 [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oltean G, Miron C, Mocean E (2002) Multiobjective optimization method for analog circuits design based on fuzzy logic. In: 9th International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems, 2002; 15–18 September 2002. Dubrovnik, Croatia: IEEEXplore, Vol. 2. pp. 777–780. Available: http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/xpl/articleDetails.jsp?arnumber=1046285. Accessed 17 June 2013.

- 68. Schuetz R, Zamboni N, Zampieri M, Heinemann M, Sauer U (2012) Multidimensional Optimality of Microbial Metabolism. Science 336: 601–604 doi:10.1126/science.1216882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Macevicz S, Oster G (1976) Modeling social insect populations II: Optimal reproductive strategies in annual eusocial insect colonies. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 1: 265–282 doi:10.1007/BF00300068 [Google Scholar]

- 70. Itzkovitz S, Blat IC, Jacks T, Clevers H, van Oudenaarden A (2012) Optimality in the Development of Intestinal Crypts. Cell 148: 608–619 doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Savir Y, Noor E, Milo R, Tlusty T (2010) Cross-species analysis traces adaptation of Rubisco toward optimality in a low-dimensional landscape. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 3475–3480 doi:10.1073/pnas.0911663107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Becskei A, Serrano L (2000) Engineering stability in gene networks by autoregulation. Nature 405: 590–593 doi:10.1038/35014651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Gardner TS, Cantor CR, Collins JJ (2000) Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli. Nature 403: 339–342 doi:10.1038/35002131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rosenfeld N, Young JW, Alon U, Swain PS, Elowitz MB (2007) Accurate prediction of gene feedback circuit behavior from component properties. Molecular Systems Biology 3: 143 doi:10.1038/msb4100185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Deb K, Pratap A, Agarwal S, Meyarivan T (2002) A fast and elitist multiobjective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 6: 182–197 doi:10.1109/4235.996017 [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zitzler E, Deb K, Thiele L (2000) Comparison of Multiobjective Evolutionary Algorithms: Empirical Results. Evol Comput 8: 173–195 doi:10.1162/106365600568202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Horn J, Nafpliotis N, Goldberg DE (1994) A niched Pareto genetic algorithm for multiobjective optimization. , Proceedings of the First IEEE Conference on Evolutionary Computation, 1994. IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence. pp. 82–87 vol.1. doi:10.1109/ICEC.1994.350037.

- 78.Schütze O, Witting K, Ober-Blöbaum S, Dellnitz M (2013) Set Oriented Methods for the Numerical Treatment of Multiobjective Optimization Problems. In: Tantar E, Tantar A-A, Bouvry P, Moral PD, Legrand P, et al., editors. EVOLVE- A Bridge between Probability, Set Oriented Numerics and Evolutionary Computation. Studies in Computational Intelligence. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 187–219. Available: http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-642-32726-1_5. Accessed 12 June 2013.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The basic monotonic shape of the Pareto front is robust to the value of the integrands' power of the two tasks. The gray line represent the original {n,m} = {2,2} tasks used throughout the paper, the label above each graph represent the power of the integrand of the economy and effectiveness tasks n and m, respectively,

(TIF)

When taking both integrands' powers together toward infinity, the Pareto front converges. The Pareto front for any n = m always begins from  and reaches the value in the graph as

and reaches the value in the graph as  goes to infinity.

goes to infinity.

(TIF)

The Pareto front for a case of nonlinear integral feedback with no separation of time scales. We extend the model in the main text by adding a time dependent ODE for  . In natural systems, the approximation that

. In natural systems, the approximation that  is much faster than

is much faster than  is reasonable. We also added nonlinearity in which