Abstract

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a genetically heterogeneous disorder of motile cilia. Most of the disease-causing mutations identified to date involve the heavy (DNAH5) or intermediate (DNAI1) chain dynein genes in ciliary outer dynein arms, although a few mutations have been noted in other genes. Clinical molecular genetic testing for PCD is available for the most common mutations. The respiratory manifestations of PCD (chronic bronchitis leading to bronchiectasis, chronic rhino-sinusitis and chronic otitis media) reflect impaired mucociliary clearance owing to defective axonemal structure. Ciliary ultrastructural analysis in most patients (>80%) reveals defective dynein arms, although defects in other axonemal components have also been observed. Approximately 50% of PCD patients have laterality defects (including situs inversus totalis and, less commonly, heterotaxy and congenital heart disease), reflecting dysfunction of embryological nodal cilia. Male infertility is common and reflects defects in sperm tail axonemes. Most PCD patients have a history of neonatal respiratory distress, suggesting that motile cilia play a role in fluid clearance during the transition from a fetal to neonatal lung. Ciliopathies involving sensory cilia, including autosomal dominant or recessive polycystic kidney disease, Bardet-Biedl syndrome, and Alstrom syndrome, may have chronic respiratory symptoms and even bronchiectasis suggesting clinical overlap with PCD.

Keywords: Primary ciliary dyskinesia, PCD, Kartagener syndrome, situs inversus, dynein

OVERVIEW

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) (MIM#244400) is a genetically heterogeneous, typically autosomal recessive, disorder characterized by ciliary dysfunction and impaired mucociliary clearance, resulting in an array of clinical manifestations, including chronic bronchitis leading to bronchiectasis, chronic rhino-sinusitis, chronic otitis media, situs inversus (in approximately 50% of cases), and male infertility. The incidence of PCD is estimated at 1/16,000 births, based on prevalence of situs inversus and bronchiectasis.1,2 However, few PCD patients carry a well-established diagnosis, which reflects, the limited ability to diagnose this disorder.

The first cases, reported in the early 1900's, and characterized by a triad of symptoms that included chronic sinusitis, bronchiectasis and situs inversus,3 became known as Kartagener syndrome. Subsequently, patients with Kartagener syndrome, as well as other patients with chronic sinusitis and bronchiectasis, were noted to have “immotile” cilia and defects in the ultrastructural organization of cilia.4-6 Initially, the term “immotile cilia syndrome” was used to describe this disorder; however, later studies showed that most cilia were motile, but exhibited a stiff, uncoordinated and/or ineffective beat. The name was changed to “primary ciliary dyskinesia” to more appropriately describe its heterogeneous genetic base and the ciliary dysfunction, as well as to distinguish it from the secondary ciliary defects acquired following multiple causes of epithelial injury.

The “gold-standard” diagnostic test for PCD has been electron microscopic ultrastructural analysis of respiratory cilia obtained by nasal scrape or bronchial brush biopsy. Recent studies have identified mutations in several genes encoding structural and/or functional proteins in cilia. Limited clinical genetic testing is currently available, but a multi-center, international collaboration is focused on defining additional PCD-specific gene mutations in order to expand PCD genetic testing. Recently, nasal nitric oxide (NO) measurement has been used as a screening test for PCD, because nasal NO is extremely low (10-20% of normal) in PCD patients.7-10 As an adjunct test, nasal NO measurement can identify individuals with probable PCD (even if ciliary ultrastructure appears normal) to target for genetic testing. We anticipate that genetic testing for PCD will soon become the “gold standard” diagnostic test in a growing number of cases.

In summary, we are in the midst of a revolution for the diagnosis, and understanding of genotype/phenotype correlations in PCD. This effort has greatly benefited from an NIH-sponsored Rare Disease Network (url: http://rarediseasesnetwork.epi.usf.edu/), and a consortium focused on studying genetic disorders of mucociliary clearance, including PCD (url: http://rarediseasesnetwork.epi.usf.edu/gdmcc/index.htm).

CILIARY STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION

Normal ultrastructure of motile cilia

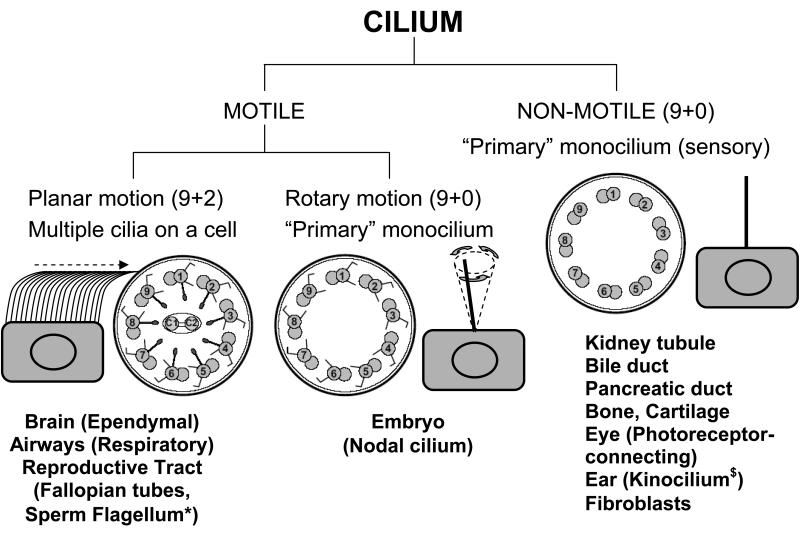

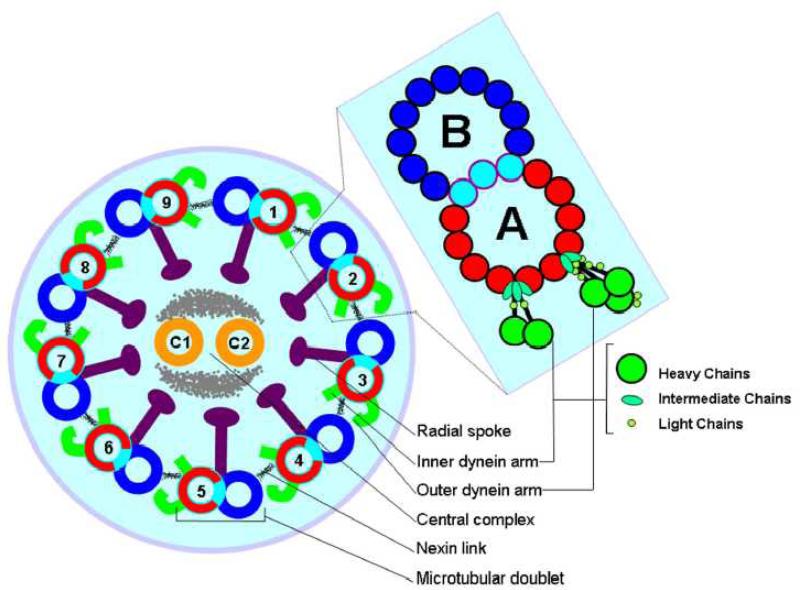

Cilia and flagella are evolutionarily ancient organelles whose structure and function have been rigidly conserved across the phylogenetic spectrum. Historically recognized for their role in cell motility and transport of fluids over mucosal surfaces, cilia have recently been recognized to have a sensory function that modulates elements of development and cell function. Both motile and sensory cilia are composed of highly organized arrays of microtubules and attendant accessory elements and their classification is depicted in Fig. 1. Microtubules are formed from α- and β- monomers of tubulin configured into helical patterns of protofilaments. The peripheral microtubules in the canonical 9+2 microtubular pattern of motile cilia are studded with dynein arms that contain ATPases and act as molecular motors to effect the sliding of the peripheral microtubular pairs relative to one another. The outer dynein arms (ODA) are positioned proximal to the ciliary membrane and the inner dynein arms (IDA) proximal to the central apparatus of the A microtubule. The dynein arms are large protein complexes each comprised of several heavy, light, and intermediate chains as shown in Fig. 2. In Chlamydomonas, and likely other eukaryotic cilia and flagella-bearing cells, the IDA and ODA are spaced in specific linear repeats of 96 nm and 24 nm, respectively11,12 along the axis of each microtubular pair, where they undergo an attachment, retraction, and release cycle with the neighboring microtubular pair that imposes a sliding motility of the pairs relative to one another. The A microtubule in cross-section is comprised of thirteen protofilaments and shares three protofilaments with the B microtubule. Studies of isolated axonemes depleted of accessory structures have shown that in the presence of ATP the microtubular pairs slide upon one another to visible light extinction. It is thought that some of the accessory structures, including the nexin links, radial spokes, and ciliary membrane provide shear forces that transition the sliding event to the bending characteristic of ciliary waveform. In contrast to the 9+2 pattern of motile cilia with dynein motors, there are structural variants without dynein motors that have a 9+0 microtubular pattern,13 which are called “primary” cilia. Unlike the numerous motile cilia present on airway epithelial cells, these primary cilia are borne as solitary appendages. Historically thought to be non-functional or vestigial, they have been rediscovered in recent years as structures central to organ positioning during embryologic development and to the detection of mechanical and chemical gradients. Thus, primary cilia are now recognized as structures modulating detection, orientation, and positioning. Virtually all cells are capable of producing a single primary cilium, which lacks dynein arms and is immotile. However, it has been suggested that populations of both non-motile primary cilia and specialized motile cilia are present in nodal cells, and that dyneins on the motile populations confer a whirling motility to the organelle that is distinct from the waveform motility typical of 9+2 motile cilia. Thus, there are three basic groups of cilia; motile 9+2 cilia with attendant dynein arm structures (e.g. respiratory epithelial cells), non-motile 9+0 primary cilia lacking dynein arms (e.g. kidney tubules), and motile 9+0 primary cilia possessing dynein arms (e.g. embryonic node). In addition to the highly specialized organization of the core of the cilium, the ciliary membrane exhibits a specialized structure, the ciliary necklace at the base of the axonemal shaft.14 The ciliary necklace has been speculated to be a docking/assembly site for axonemal elements, since nascent organizing structures of these arrays have been reported on the luminal membranes of cells in early stages of ciliogenesis.15

Figure 1.

Diversity of ciliary axoneme. Cross section of non motile (9+0 arrangement) and motile cilia (9+2 and 9+0 arrangement) are shown.27,182 Studies to date have not determined whether the 9+0 monocilium has radial spokes. The model showing synchronous motion of motile (9+2), rotatory motion of motile monocilium (9+0) and immotile monocilium (9+0) is also shown.

* Solitary axoneme in the sperm mirrors the structure of the cilium

§ Subcellular structure of the kinocilum is debatable. Some reports indicate 9+0 while others indicate 9+2 configuration. The function of the kinocilium is also not clear as it disappears during the mammalian early postnatal period.183

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the eukaryotic cilium. Cross-section illustrates the 9+2 configuration of nine peripheral microtubular doublets surrounding a central pair microtubule complex. The expanded view of a microtubular doublet schematically depicts cross-sections of the tubulin protofilaments including those shared by the A and B tubules. The dynein arms in the expanded view are rendered to schematically depict several light, intermediate, and heavy chains comprising each of these structures. While the outer arm exhibits a specific distribution of dyneins, being uniformly composed of three heavy, two intermediate and at least 8 light chains, the distribution of dyneins in the inner arm is thought to be more variable.

Normal ciliary beat frequency

Two distinctive types of motility are representative of 9+2 and 9+0 motile cilia. Ciliated epithelial cells bear approximately 200 motile (9+2) cilia that move with both intracellular and intercellular synchrony. The pattern of beat in 9+2 motile cilia occurs in a waveform having a forward effective stroke followed by a return stroke. The direction of stroke is a function of the directional orientation of the central microtubules. In addition to moving in synchrony, individual cilia in normal cells are very plastic and move fluidly, sometimes deforming briefly upon encountering resistance and/or particles being transported over the mucosal surface. Cilia are embedded in a watery periciliary fluid of low viscosity, which facilitates the rapid beat cycle to move the more viscous overlying layer of mucus. Ciliary beat frequency ranges from approximately 8-20 Hz under normal conditions, but may be accelerated by exposure to irritants such as tobacco smoke.16 The mechanism whereby beat frequency is accelerated has been suggested to be regulated through the activity of nitric oxide synthases localized in the apical cytoplasm. While baseline ciliary beat frequency is not thought to be under NO regulation, NO accelerates ciliary beat frequency in response to challenge through soluble adenylyl or guanylyl cyclase to form their respective cyclic nucleotides with activation of protein kinase G (PKG) and A (PKA) to accelerate beat frequency.17,18 Increases in intracellular calcium fluxes19,20 may also play a role in accelerating ciliary beat frequency.

In contrast to the forward/return waveform of 9+2 cilia, motile nodal 9+0 cilia beat with a vertical motion. This type of motility is thought to direct nodal flow “leftward” across the node, which is necessary for establishment of proper left/right asymmetry.

Cilia composition and conservation across species

The ciliary genome is highly conserved across the phylogenetic spectrum from simple unicellular eukaryotes and lower animals to functionally complex mammalian cells and tissues. The genomes for many of organisms are already characterized and the simple organisms are easily grown in the substantive quantities and manipulated in the laboratory setting to facilitate structural, functional, and genetic studies. This provides opportunities to identify cilia-specific mutations that may represent candidate genes for human ciliopathies.21 Indeed, mutations conferring outer dynein arm defects in primary ciliary dyskinesia have orthologs in Chlamydomonas.22 Moreover, genes encoding polycystins and intraflagellar transport proteins in Chlamydomonas also have orthologs with relevance to polycystic kidney disease.23,24 Hence studying orthologous genes across the various species is valuable in order to decipher the candidate genes for human ciliopathies.

GENETICS

Genetic heterogeneity; challenges and methods to identify disease-causing genes

Dysfunction of the axonemal structure has been linked to the emerging class of disorders collectively known as “ciliopathies” which includes PCD / Kartagener syndrome, Bardet-Biedl syndrome, hydrocephalus, polycystic kidney disease, polycystic liver disease, nephronophthisis, Meckel-Gruber syndrome, Joubert syndrome, Alstrom syndrome, Jeune syndrome, and laterality defects.25-28 PCD was the first human disorder linked to the dysfunction of motile cilia and that will be discussed in detail in this chapter.

Axonemal structure, which is conserved through evolution, is complex and comprised of multiple proteins; hence, it is not surprising that PCD is a genetically heterogeneous disorder posing challenges for defining causative genes. Conventional family based genome wide linkage studies have failed to identify PCD causing genes,29 because combining data from multiple families limits power when dealing with a genetically heterogeneous disorder, such as PCD. Multiple other methodologies alone, or in combination, have been successfully applied to elucidate the genetic basis of PCD, including functional candidate gene testing,30-34 homozygosity mapping35-37 followed by positional candidate gene analysis, and comparative computational analysis involving comparative genomics, transcriptomics and proteomics.38-43 Thus far, mutations have been identified in eight genes (Table 1) in PCD (DNAI1, DNAH5, DNAH11, DNAI2, KTU, RSPH9, RSPH4A and TXNDC3) but no genotype/phenotype associations have been defined and these genes are discussed in detail below:

Table 1.

Candidate genes tested and found to be mutated in PCD patients

| Human Gene | Axonemal component |

# of PCD families tested |

# of PCD families with biallelic mutations |

# of PCD families with only monoallelic mutations |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNAH5 | ODA-HC | 134 | 28 | 10 | 36,50,51 |

| DNAH11 | ODA HC | 2 | 2 | 0 | 30,37 |

| DNAI1 | ODA IC | 226 | 20 | 2 | 33,44-46 |

| 104 | 2 | 2 | 48 | ||

| DNAI2 | ODA IC | 10 | 0 | 0 | 34 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 53 | ||

| 106 | 3 | 0 | 35 | ||

| TXNDC3 | ODA LC/IC | 41 | 1 | 0 | 31 |

| KTU | cytoplasmic* | 112 | 2 | 0 | 32 |

| RSPH9 | RS | 2 | 2 | 0 | 56 |

| RSPH4A | RS | 5 | 5 | 0 | 56 |

= cytoplasmic protein requires for the dynein arms assembly

Abbreviations:

ODA: outer dynein arm, IDA: inner dynein arm, HC: heavy chain, IC: intermediate chain, LC: light chain, RS: radial spoke

DNAI1

DNAI1 (dynein axonemal intermediate chain 1) (MIM#604366), was the first PCD-causing gene to be identified based on the candidate gene approach. This approach takes advantage of the fact that the axoneme is highly conserved through evolution, and human orthologs of the genes known to cause specific ultrastructural and functional defect in other species are candidates for PCD. Chlamydomonas is a bi-flagellate, unicellular algae with well studied genetics and multiple motility mutants. One such mutant (oda9) had a mutation in the IC78 (intermediate chain 78) gene, resulting in a flagellar ODA defect. The human ortholog of IC78 (DNAI1) was cloned and tested in 6 unrelated PCD patients with ODA defects and biallelic mutations were identified in one PCD patient.33 Two studies reported biallelic mutations in three additional unrelated patients with PCD.44,45 Subsequently, a large study comprising of 179 unrelated patients revealed 9% (14 with biallelic and 2 with only monoallelic mutations) of all PCD patients carry mutations in DNAI1.46 Thus, taken together from all published literature, mutations in DNAI1 were seen in approximately 10% (22 of 226) of all PCD patients and it increased to 14%, if only patients with ODA defects were considered.33,44-46 Despite allelic heterogeneity, the IVS1+2_3insT founder mutation represented 55% of all the mutant alleles, as well as mutation clusters were seen in other exons (exons 13, 16, and 17), and these observations became the basis for the clinical molecular genetic test for PCD.33,44-47 In addition, IVS1+2_3insT founder mutation appears to be more common in individuals of the Caucasian descent.46 A recent study from Europe in 104 PCD patients (without phenotypic preselection) revealed biallelic mutations in DNAI1 in only 2% of the patients.48 Interestingly, these authors also observed 3 unrelated PCD patients harboring the IVS1+2_3insT founder mutation in DNAI1.

DNAH5

The DNAH5 (dynein axonemal heavy chain 5) (MIM#603335) gene was identified as a causative gene for PCD using homozygosity mapping. This approach requires the analysis of a large affected inbred family and assumes that the recessive disorder is caused by a homozygous mutation that is inherited from the common ancestor. Using a large Arab inbred family with PCD, Omran and colleagues found the locus on chromosome 5, which included DNAH5 within the shared interval.49DNAH5 was a candidate gene for PCD because the mutation in its ortholog γ-HC (gamma-heavy chain) in Chlamydomonas caused flagellar immotility and ODA defects; and indeed, mutations were observed in 8 unrelated PCD families.36 Subsequently, the same group carried out large scale studies using 134 unrelated PCD patients and found that ~28% of all PCD patients harbor mutations in DNAH5.50,51 Despite allelic heterogeneity, mutation clusters were observed in five exons (exons 34, 50, 63, 76 and 77), which assisted in the development of the first clinical molecular genetic test for PCD.47 Immunofluorescence studies on the respiratory epithelium and sperm flagella of patients known to harbor biallelic DNAH5 mutations showed that the mutant protein is present in the microtubule organizing center (MTOC) of the respiratory epithelial cells, but failed to localize along the axonemal shaft.28,52 Interestingly, sperm analysis from a male patient showed normal immunofluoresence staining pattern; thus, DNAH5 is not mislocalized in the sperm flagella.52

DNAI2

The DNAI2 (dynein axonemal intermediate chain 2) (MIM#605483) is an intermediate chain dynein of the ODA that was cloned and characterized utilizing the candidate gene approach. Mutations in the Chlamydomonas ortholog (IC69) caused an immotile mutant strain (oda6) which had loss of ODA.34 Initial studies showed no disease causing mutations in 16 PCD families, including 6 families with microsatellite marker alleles concordant for loci on chromosome 17q23-ter (locus for DNAI2).34,53 Very recently, Loges et al35 used homozygosity mapping and identified linkage to the DNAI2 locus in a consanguineous Iranian Jewish family, and a homozygous splice mutation (IVS11+1G>C) in all the affected individuals. Subsequently, they sequenced an additional 105 unrelated patients (48 with ODA defects) and identified a homozygous splice mutation (IVS3-3T>G) in a Hungarian PCD family and a homozygous stop mutation (R263X) in a German patient. Thus, DNAI2 mutations are found in ~ 2% of all PCD families and 4% of PCD families with documented ODA defects.35

DNAH11

Genetics of DNAH11 (dynein axonemal heavy chain 11) (MIM#603339) are still emerging. A patient with uniparental isodisomy of chromosome 7 presented with cystic fibrosis due to the common homozygous mutation (deltaF508) in CFTR (MIM# 602421). In addition, this patient had situs inversus, which is not part of the spectrum of cystic fibrosis.30 Upon investigation of the region near CFTR on chromosome 7, DNAH11 emerged as a candidate gene because mutations in the ortholog β-HC (beta-heavy chain) dynein and left right dynein (lrd) caused motility defects in Chlamydomonas oda4 mutant strain (reviewed in reference22) and situs inversus in mice54,55 respectively. Sequencing of DNAH11 in this cystic fibrosis patient with situs inversus revealed a homozygous nonsense mutation (R2852X).30 Because this patient had airways disease due to cystic fibrosis and no defined ciliary ultrastructural defect, it was not certain if the patient also had PCD, or only isolated situs inversus; hence, the status of DNAH11 as a PCD causing gene remained undefined. Very recently, a large German family with 5 affected individuals (and Kartagener syndrome) was found to harbor biallelic compound heterozygous truncating mutations in DNAH11.37 Although, the electron microscopic analysis and immunofluorescence localization in these patients showed normal dynein arms, they had abnormal ciliary beat patterns. Since PCD patients with normal dynein arms are difficult to diagnose, it will be important to carry out large scale genetic studies of DNAH11 in PCD subjects to decipher if DNAH11 plays an important role in PCD patients with normal DA.

TXNDC3

Thioredoxin-nucleoside diphosphate (TXNDC3) (MIM#607421) ortholog in Chlamydomonas (LC3 (Light chain 3) and LC5 (light chain 5)) and sea urchin ((IC1 (intermediate chain 1)) is a component of sperm ODA. Due to the involvement of TXNDC3 in the ODA, it was considered a candidate gene and tested in 41 unrelated PCD patients.31 Only one patient harbored a nonsense mutation (L426X) on one allele inherited from the mother31 and a common intronic variant (c.271-27C>T) on the trans allele. Although this variant is present in 1% of non-PCD control subjects, it occurs near the branch point in the intron that is involved in the splicing. TXNDC3 encodes two transcripts, one full length isoform and a novel short isoform TXNDC3d7 (inframe deletion of exon 7) that is thought to bind microtubules. The authors concluded that the variant was pathogenic in the patient with a nonsense mutation on one allele and the variant on the other allele because the levels of the short isoform (TXNDC3d7) were reduced in this PCD patient thereby affecting the ratio of the two isoforms.31

KTU

A truncating homozygous mutation in Ktu (previously known as Kintoun or knt) (MIM#612517) in Medaka fish causes laterality defects, polycystic kidney disease and impaired sperm motility in male fish. Ultrastructural analysis of the cilia of Kupffer’s vesicle (functionally equivalent to the mouse node) and flagella of sperm from the fish revealed ODA+IDA defects.32 Similar ultrastructural defects were found in the paralyzed flagella mutant strain of Chlamydomonas (pf13) that harbored mutation in the PF13 gene (ortholog of KTU), required for the ODA assembly.32KTU does not belong to the dynein family genes, but it is a cytoplasmic protein that is required for the assembly of the dynein complex and hence was considered a candidate gene for PCD.32 A total of 112 unrelated PCD patients were tested for the mutations in KTU and two unrelated inbred families were found to harbor truncating mutations; the ciliary ultrastructural analysis revealed ODA+IDA defects. Of the 112 PCD families tested, only 17 had defined ODA+IDA defects; thus, mutations in KTU occur in 12% PCD patients with ODA+IDA defects.32 Interestingly, KTU mutations caused PCD in humans, but polycystic kidney disease in fish, perhaps due to the difference in the origin of the kidneys that are mesonephric in fish and metanephric in mammals.

RSPH9

Very recently, Castleman et al56 identified the mutations in RSPH9 (radial spoke head protein 9). The authors carried out homozygosity mapping and identified the disease interval on chromosome 6 and subsequently discovered the inframe deletion (K268del) in RSPH9 in two Arab Bedouin families. The ultrastructural analysis from the patients who harbored mutations was the mixture of 9+2 or 9+0 microtubular configuration in one family and the normal dynein arms in the other family.56 Interestingly, Chlamydomonas motility defective mutant; pf17 that harbors mutation in the orthologous gene RSP9, shows the absence of entire radial spoke head and the central pair displacement.57

RSPH4A

Another PCD causing gene that has emerged very recently is RSPH4A (radial spoke head protein 4A).56 This gene was identified by the virtue of homozygosity mapping in three inbred Pakistani families. Homozygous nonsense mutation (Q154X) was identified in all three inbred and one out-bred Pakistani families in RSPH4A. In addition, one family of a Caucasian descent was compound heterozygous for the mutations (Q109X + R490X) in this gene. Ultrastructural analysis in all of the five PCD families with the mutation showed transposition defects with the absence of central pair and 9+0 or 8+1 microtubule configurations.56RSPH4A is orthologous to the Chlamydomonas RSP4 and RSP6. However, Chlamydomonas motility defective mutants pf1 and pf26 lacking RSP4 or RSP6 respectively, show absence of radial spoke head.58

Genes tested and found to be negative in PCD

A number of other PCD candidate genes have been tested and found to be negative in PCD patients. These genes include DNAH9 (dynein axonemal heavy chain 9), DNAH17 (dynein axonemal heavy chain 17), DNAL1 (dynein axonemal light chain 1), DNAL4 (dynein axonemal light chain 4), TCTE3 (T complex-associated testis-expressed 3), DYNLL2 (dynein light chain 2), DNALI1 (dynein axonemal light intermediate polypeptide 1 (HP28)), DNAH3 (dynein axonemal heavy chain 3), DNAH7 (dynein axonemal heavy chain 7), SPAG6 (sperm-associated antigen 6), SPAG16 (sperm-associated antigen 16), DPCD (deleted in PCD), and FOXJ1 (forkhead box J1 (HFH-4)). The details about the number of patients tested for each of these genes is given in Table 2. Some of these genes may still be candidates for PCD as they were either tested in a small cohort of patients or the patients were not preselected based on ultrastructural findings to test for the appropriate axonemal component gene.

Table 2.

Candidate genes tested and found negative in PCD patients

| Human Gene | Axonemal component |

# of PCD families tested |

# of PCD families with biallelic mutations |

# of PCD families with only monoallelic mutations |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNAH9 | ODA HC | 2 | 0 | 0 | 184 |

| DNAH17 | ODA HC | 4 | 0 | 0 | 185 |

| DNAL1 | ODA LC | 86 | 0 | 0 | 186 |

| DNAL4 | ODA LC | 54 | 0 | 0 | 187 |

| TCTE3 | ODA LC | 36 | 0 | 0 | 188 |

| DYNLL2 | ODA LC | 58 | 0 | 0 | 53 |

| DNALI1 (HP28) | IDA LC | 61 | 0 | 0 | 187,189 |

| DNAH3 | IDA HC | 7 | 0 | 0 | 190 |

| DNAH7 | IDA HC | 1 | 0 | 0 | 191 |

| DPCD | IDA gene | 51 | 0 | 0 | 96 |

| SPAG6 | CA | 54 | 0 | 0 | 185 |

| SPAG16 | CA | 5 | 0 | 0 | 192 |

| FOXJ1/HFH-4 | expressed* | 8 | 0 | 0 | 89 |

= expressed in respiratory cilia

Abbreviations:

ODA: outer dynein arm, IDA: inner dynein arm, HC: heavy chain, IC: intermediate chain, LC: light chain, CA: central apparatus

PCD co-segregating with other syndromes (OFD1 and RPGR)

In a few instances, PCD cosegregates with other genetic conditions and the causative genes primarily do not affect ciliary motor function. A large inbred Polish kindred was identified with a novel X-linked mental retardation syndrome, together with the compatible clinical PCD phenotype and dyskinetic cilia. Linkage studies followed by comparative genomic analysis identified the locus on the X chromosome including OFD1 (formerly known as CXORF5) (MIM# 311200). Mutation analysis confirmed the frameshift mutation in OFD1 in all the affected individuals tested from the Polish family.59 OFD1 is localized to the centrosomes and the basal body of the primary cilia and does not affect ciliary motor function.60,61 The index patient with the OFD1 mutation had disorganized ciliary beat suggesting the role of OFD1 in the respiratory epithelial ciliary function.59

A family consisting of two probands has been described by Moore et al.,62 with the X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (xlRP) (MIM# 268000), oto-sino-pulmonary symptoms consistent with PCD, and multiple abnormalities of all the ciliary components by ultrastructural analysis. Upon sequencing, both patients harbored a 57 bp deletion that is predicted to cause a truncated protein in RPGR that resides on the X chromosome (MIM# 312610).62 Furthermore, Zito et al.,63 described a patient with PCD and mild hearing loss together with xlRP. They detected a frameshift mutation in RPGR. In addition, Iannaccone et al.64 report a family with PCD and otitis media with bronchitis together with xlRP and the presence of a missense mutation in RPGR. RPGR protein is expressed in rods and cones and is essential for photoreceptor maintenance and viability.65 RPGR is also expressed in cochlear, bronchial and sinus epithelial lining cells,64,66 indicating a possible functional role for the broad phenotype in patients with RPGR mutations.

Animal models for PCD

Animal models for PCD are available that are either naturally occurring or constructed via genetic manipulations. They include dogs,67-71 cats,72 pigs,73 rats74 and mice. Causative genes in the animal models other than the mouse models are not yet known. Several axonemal component gene knock-out mice have been created including Mdnah5 (mouse dnah5),75,76lrd,54,55,77-79Dpcd/poll (deleted in PCD/polymerase lambda),80Pcdp1 (PCD protein 1),81hydin,82-85Tektin-t,86Mdhc7 (mouse dynein heavy chain 7, human ortholog (DNAH1; dynein axonemal heavy chain 1)),87,88Foxj1/Hfh4,89Spag16,90-92Spag6,90,93 and Spag16/Spag6 double knock-outs.94 None of these mice models presented with the classic PCD phenotype, except for the Mdnah5 and Dpcd/poll. None of these genes harbored mutations in the human orthologs (see Tables 1 and 2) in the PCD patients, except for the Mdnah5 and lrd (discussed in detail, below).

Mdnah5 deficient mouse

Mdnah5 nullizygous mice were generated by transgenic insertional mutagenesis that led to a frameshift mutation. These mice presented with the classical features of PCD, including respiratory infections, situs abnormalities, immotility of the cilia and ultrastructural analysis revealing absent ODA.75 Consistent with the autosomal recessive mode of inheritance, only homozygous mutant mice presented with the PCD phenotype. Almost all homozygous mutant mice developed hydrocephalus leading to perinatal lethality and indeed partial ODA defects were noted in the ependymal cells that are lining the brain ventricles and the aqueduct.95 Recently, another group identified the homozygous mice with an inframe deletion of 593 amino acids (exons 7-17) during the ENU (ethylnitrosourea) mutagenesis screen.76 These mice, (known as Dnahc5del593), presented with dyskinetic cilia and ODA defects in respiratory cilia. Mice presented with situs inversus totalis (35%) and heterotaxy (40%) with congenital heart defects leading to post-natal lethality. DNAH5 is the only gene thus far known to cause PCD in humans and mice.36,51

Other interesting mouse models

Another mouse model with the classic PCD phenotype is Dpcd/poll knock out mice presenting with sinusitis, situs inversus, hydrocephalus, male infertility and ciliary IDA defect.80 The initial study considered the mouse phenotype to be caused by the homozygous deletion of poll,80 but later it was discovered that another gene known as Dpcd was also deleted in these mice.96 In addition, mice generated with the catalytic domain of poll did not have a PCD phenotype.97 Thus; taken together, it appears that poll is not a candidate for the PCD phenotype in these mice that may be due to the Dpcd deletion. The human ortholog (DPCD) was tested in 51 patients with PCD (15 with IDA defects) and no mutations were discovered.96 A note-worthy model is for the left-right-dynein (lrd) deficient mice (lrd mice, iv mice and lgl mice) where classic PCD phenotype is not observed, but these mice present with the situs abnormalities and normal dynein arms by ultrastructural analysis.54,55,77-79 Interestingly, mutations have been observed in the human ortholog of lrd (DNAH11) in PCD patients.30,37

CLINICAL FEATURES

Introduction

Ciliated cells line the airways of the nasopharynx, middle ear, paranasal sinuses, and lower respiratory tract from the trachea to the terminal airways.98 Each ciliated cell has approximately 200 cilia projecting from its surface in the same orientation. Coordinated movement of the cilia sweeps the periciliary fluid and overlying mucus, resulting in vectoral movement of mucus out of the lower respiratory tract. The mucociliary escalator is the primary defense mechanism of the airways,99,100 and any functional disruption, primary or acquired, can lead to chronic sino-pulmonary symptoms.

Early clinical manifestations

The clinical features of PCD manifest early in life (Table 3). Most PCD patients (70-80%) present in the neonatal period with respiratory distress, which suggests that motile cilia are critical for effective clearance of fetal lung fluid.9,101-103 Several case reports have emphasized unexplained atelectasis or pneumonia in term newborns, which can present with hypoxemia or even acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation. Despite this early clinical feature, the association of newborn respiratory distress with PCD has been under-recognized and diagnosis is often delayed. In a retrospective review, investigators have found the mean age of PCD diagnosis was more than 4 years of age despite these early pulmonary manifestations.104 Persistent rhinitis and chronic cough are present since early infancy. Chronic cough is consistently reported in the majority of subjects (84-100%), and typically characterized as wet and productive.9,105,106 The infant may also exhibit poor feeding and failure to thrive in the early years of life,107 similar to cystic fibrosis, thus, making the diagnosis a challenge.

Table 3.

Clinical Features of PCD

| Middle ear |

| Chronic otitis media |

| Conductive hearing loss |

| Nose and Paranasal sinuses |

| Neonatal rhinitis |

| Chronic nasal congestion and mucopurlent rhinitis |

| Chronic pansinusitis |

| Nasal polyposis |

| Lung |

| Neonatal respiratory distress |

| Chronic cough |

| Recurrent pneumonia |

| Bronchiectasis |

| Genitourinary tract |

| Male (and possibly female infertility) |

| Laterality defects |

| Situs inversus totalis |

| Heterotaxy (± congenital cardiovascular abnormalities |

| Central nervous system |

| Hydrocephalus |

| Eye |

| Retinitis pigmentosa |

Laterality defects

A classic phenotypic feature of PCD that may be detected at birth are left-right laterality defects. The prevalence of situs inversus totalis tends to be over 60% in the pediatric population, as opposed to 50% in the adult population, suggesting that situs abnormalities may serve as a marker to aid in disease diagnosis.9,105,106,108,109 Without functional nodal cilia in the embryonic period, thoracoabdominal orientation is random and not genetically pre-programmed.

Heterotaxy and congenital cardiovascular defects

Patients with Kartagener syndrome have a greater incidence of congenital cardiovascular defects, and recent studies have found that approximately 6% of PCD patients have heterotaxy (situs ambiguus or organ laterality defects other than situs inversus totalis),110 which is associated with increased morbidity due to complex cardiovascular anomalies. Heterotaxia syndromes include abdominal situs inversus, polysplenia (left isomerism) and asplenia (right isomerism and Ivemark) syndromes.111 It is therefore recommended that patients with anomalies consistent with situs ambiguuus or heterotaxy, including congenital heart disease, with neonatal respiratory distress or chronic respiratory tract infections be referred for PCD screening.

Upper respiratory tract

The upper respiratory tract is frequently involved in PCD. Rhinosinusitis (100%) and otitis media (95%) are cardinal features of the disease, are responsible for much of the morbidity associated with PCD in early childhood.9,104 Nasal congestion and/or rhinorrhea are very common, and some patients have nasal polyposis. Middle ear disease is described in virtually all cases of PCD with varying degrees of chronic otitis media and persistent middle ear effusions, such that patients are often first referred to an otolaryngologist, who must have a high index of suspicion for the disease. The middle ear disease often leads to multiple sets of pressure-equalization (PE) tubes in early childhood,9,105,112 which can be complicated by persistent, purulent otorrhea. Middle ear disease often leads to conductive hearing loss.

Lower respiratory tract

Most patients (and their family members) report a chronic, productive cough as a prominent symptom of PCD, since cough compensates for the lack of effective mucociliary clearance. Physiologic data have shown that “effective” coughs can produce effective lung clearance, almost equal to normal mucociliary clearance over short time periods, even in PCD subjects with severe ciliary defects.113 Impaired mucociliary clearance of the lower respiratory tract leads to recurrent episodes of pneumonia or bronchitis. Bacterial cultures of lower respiratory secretions most commonly yield non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, including mucoid strains, has also been reported, most often in older individuals.9

Bronchiectasis; severity of disease

Clinical and radiographic evidence of bronchiectasis develops as the disease progresses, often accompanied by digital clubbing. Review of high-resolution computerized tomography (CT) findings of the lungs showed that bronchiectasis primarily involves the middle and lower lobes (100% adults and 55% pediatric patients).114,115 Bronchiectasis and obstructive impairment may be apparent in preschool children.106,116 When compared to cystic fibrosis (CF), pulmonary involvement is generally milder in PCD when controlled for age and gender. Studies examining lung function decline suggest that forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) in a cross-section of PCD patients decreases slower than that seen in CF.9,117 PCD patients can develop chronic respiratory impairment (25% in one series) as defined by hypoxemia or an FEV1 less than 40% predicted for age and some may eventually require lung transplantation.9,118 Pulmonary involvement also adversely impacts quality of life as PCD patients mature, and is increasingly recognized as both medical and public understanding in ciliopathies increase.119

Infertility

Men with PCD are typically infertile as a result of impaired spermatozoa motility secondary to defective sperm flagella, although it is not a universal finding.120,121 Males with PCD may occasionally have intact spermatozoa motility, suggesting sperm tails may retain some function or could have different genetic control than cilia.120 Female fertility is more variable; with reduced fertility in some that report delay in conception following unprotected intercourse, presumably due to abnormal ciliary function in the Fallopian tube.120,122

Other clinical manifestations

Other clinical manifestations of PCD are rare and less well understood. Several reports have linked hydrocephalus with PCD, hypothetically due to impaired cerebrospinal fluid flow secondary to dysfunctional motile cilia that line the ventricular ependymal cells.123,124 Hydrocephalus is frequently found in murine PCD models, but its incidence or clinical relevance in PCD patients is unclear. Retinitis pigmentosa has recently been linked to some forms of PCD,62-64,125 and recently, bronchiectasis was reported in 37% of patients who have autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease.126 Findings in these studies suggest phenotypic overlap between sensory and motile ciliopathies.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of primary ciliary dyskinesia is often delayed until late childhood or adulthood as a consequence of the heterogeneous nature of the disease, lack of physician knowledge of disease characteristics and the technical expertise required for an accurate diagnosis.9,104 Several clinical presentations warrant consideration of PCD in the differential diagnosis, including infants with unexplained respiratory distress and/or laterality defect, and infants and children who present with chronic cough, nasal drainage and sino-pulmonary disease.

(a) Neonatal respiratory distress

The differential diagnosis for neonatal respiratory distress in a term infant is extensive, and includes transient tachypnea of the newborn (TTNB), neonatal pneumonia and meconium aspiration,127 as well as rarer causes such as surfactant protein deficiency128 and interstitial lung disease. Infants with PCD are often misdiagnosed with TTNB or neonatal pneumonia in the newborn period. Surfactant protein deficiency, a rare form of interstitial lung disease (see below), presents in infancy with severe tachypnea and hypoxia, often requiring mechanical ventilation. These children typically have diffuse interstitial disease on chest CT and alveolar proteinosis on bronchoalveolar lavage, neither of which are seen in PCD.129,130

(b) Laterality defects

Situs inversus totalis occurs in approximately 50% of patients with PCD;9,131 approximately 25% of subjects with situs inversus have PCD.132 Other situs anomalies (heterotaxy), such as abdominal situs inversus, polysplenia, and right and left isomerism, may also be found in PCD;110,133 and, in conjunction with neonatal respiratory distress, should prompt an evaluation for PCD. Congenital heart disease, especially involving defects of laterality, may also be present in subjects with PCD;110,131,133 however, respiratory distress secondary to PCD may be difficult to distinguish from distress secondary to cardiac defects, thereby, delaying diagnosis.

(c) Chronic cough, nasal congestion and sino-pulmonary disease

The differential diagnosis includes CF, asthma, allergic rhinitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease (with or without aspiration), immunodeficiency, interstitial lung disease, and idiopathic bronchiectasis (see Table 4).9,131,134

Table 4.

Differential Diagnoses, Presenting Symptoms, and Findings

| SYMPTOMS | PCD | CF | Asthma | Allergic Rhinitis |

GERD | ILD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cough | +++ | +++ | ++ | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| frequency | chronic, daily | chronic | intermittent | intermittent | intermittent | intermittent |

| character | wet | wet | dry | dry or wet | dry or wet | dry or wet |

| time of year | year-round | year-round | often seasonal | often seasonal |

year-round | year-round |

| Nasal congestion | +++ | ++ | w/ allergic | ++ | − | − |

| frequency | chronic, daily | intermittent | rhinitis | intermittent | ||

| time of year | year-round | year-round | often seasonal |

|||

| Otitis media | +++ | − | − | − | + | ++ |

| Sinus disease | +++ | +++ | − | ++ | − | − |

| Neonatal respiratory distress | +++ | − | − | − | − | +++ |

|

| ||||||

| FINDINGS | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Chest imaging | hyperinflation, infiltrates, atelectasis, peribronchial thickening, bronchiectasis |

hyperinflation, infiltrates, atelectasis, peribronchial thickening, bronchiectasis |

hyperinflation, infiltrates, rare atelectasis, |

normal | normal, or infiltrates with aspiration, rare bronchiectasis |

ground-glass opacities, hyperlucency, consolidation, septal thickening, cysts, nodules |

|

Pulmonary

Function Testing |

obstructive, later mixed |

obstructive, later mixed |

obstructive | normal | normal | restrictive |

DEFINITIONS:

+++ Occurs in over 75% of patients with classic disease

++ Occurs in many patients with classic disease

+ Occurs in some patients with classic disease

− Occurs at same frequency as in general population

Abbreviations:

PCD: primary ciliary dyskinesia, CF: cystic fibrosis, GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease, ILD: interstitial lung disease (examples of ILD presenting in neonatal period include surfactant protein C deficiency and neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia)

Cystic Fibrosis

Both PCD and CF are characterized by chronic, productive cough, obstructive impairment on lung function testing,116,135-137 and radiologic changes including hyperinflation, subsegmental atelectasis, and bronchiectasis.9,134,135,138 Parents of PCD children often note that cough was present from birth, which may distinguish these patients from those with CF.9,134 Digital clubbing, chronic sinusitis and nasal polyps can occur in both diseases.9,131,134 The gastrointestinal and nutritional issues commonly seen in CF (e.g. failure to thrive, steatorrhea, and liver disease) are not typical of PCD.134,138 In contrast, chronic otitis media is a hallmark of PCD, occurring in 90-100% of PCD patients, while the incidence of otitis media in CF is not increased compared to the general population.9,131 CF can be ruled out by pilocarpine sweat electrolyte testing and/or by CFTR gene mutation analysis.139

Asthma and Allergic Rhinitis

PCD and asthma can both be characterized by chronic cough; however, this cough is usually dry and non-productive in asthma as opposed to the wet cough of PCD.140-142 Atelectasis is a common finding in both PCD and asthma, often associated with hyperinflation.143,144 Obstructive impairment on pulmonary function testing is seen in both PCD and asthma; however, bronchodilator responsiveness, a common feature in asthma, is not typical in children with PCD.131,141

Gastroesophageal reflux disease and aspiration

Gastroesphageal reflux disease (GERD) may present with a variety of pulmonary and upper respiratory tract symptoms, including cough, wheeze, rhinorrhea, sneezing, and recurrent pneumonia.145,146 Aspiration pneumonia (chemical pneumonitis) can occur as a result of GERD typically involves upper lobes on chest radiograph,147 while radiologic findings in PCD have a predilection for the right middle lobe and lingula.134

Immunodeficiency

Primary immunodeficiencies often present with chronic sino-pulmonary infections, resulting in a distinct overlap in symptoms with PCD.148,149 The antibody deficiencies seen with humoral diseases result in increased susceptibility to encapsulated bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae), and lead to recurrent pneumonia, sinus infection, and otitis media with symptoms which overlap with PCD.

Interstitial Lung Disease

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a descriptive term that encompasses a spectrum of over 100 lung diseases of both known and unknown etiology, all of which involve damage of the alveolar wall, accumulation of extracellular matrix within the pulmonary interstitium, and destruction of normal alveolar-capillary complexes, with progression towards pulmonary fibrosis.130,150 Patients with ILD may present in infancy or childhood with pulmonary infiltrates, hypoxia, cough, tachypnea, and frequent infections.129,130,150 Pulmonary function testing in ILD typically shows restrictive impairment129 that is distinct from the obstructive impairment seen in PCD. Typical findings on high-resolution chest CT (HRCT) in ILD include ground-glass opacities, septal thickening, geographic hyperlucency, consolidation, and cysts or nodules,129 all of which are distinct from the hyperinflation, atelectasis, infiltrates, bronchial thickening, and bronchiectasis seen in PCD.9,105

DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

The diagnostic approach to PCD is evolving. Until recently, the only definitive diagnostic test had been electron microscopy to define ultrastructural defects in cilia supported by light microscopic analysis demonstrating obvious ciliary dysfunction (immotile or profoundly dyskinetic cilia). Emerging diagnostic tests include genetic testing, nasal nitric oxide measurement, immunofluorescent analysis, and high-speed videomicroscopy to define subtle ciliary dysmotility. At this point, these specialized diagnostic tests are not standardized or readily available; therefore, referral to research centers may be needed. A systematic research approach to diagnosing PCD has defined some individuals with normal ciliary ultrastructure, who have PCD based on identification of disease-causing mutations in a ciliary genes associated with subtle defects in ciliary motility (as described above). It is conceivable that ultrastructural defects may represent a small fraction of individuals with a genetic defect of cilia in PCD.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

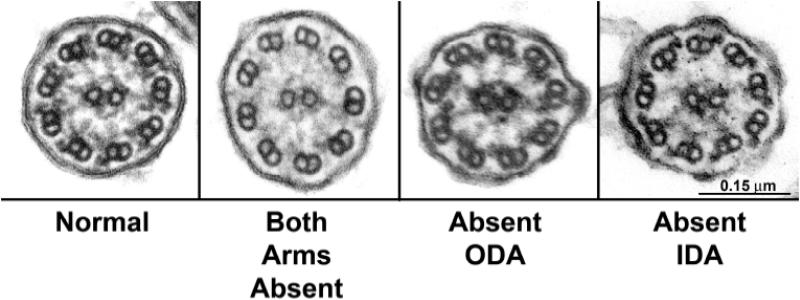

Ultrastructural changes in PCD

Ultrastructural defects of cilia associated with mucociliary dysfunction was first described in 1975 by Afzelius et al.4,151 These reports identified absent and dysmorphic dynein arms in spermatozoa and airway cilia of affected individuals and subsequent reports have supported these observations. Current ciliary ultrastructural diagnostic criteria include absence or structural modification of either inner or outer dynein arms individually, or of both dynein arms152-155 (Fig. 3). Cilia with defective radial spokes and transposition of a peripheral pair of microtubules to occupy the central axis also have been associated with disease consistent with PCD, although such cases appear to be rare.156,157 Although a variety of other ciliary ultrastructural defects such as axonemal changes, are reported in respiratory disease, these changes are “secondary” and can be traced to infection, inflammation, or irritant exposure.158,159 These abnormalities are distinguished from the index ultrastructural lesions of PCD by their lack of universality in all cilia of affected individuals. Indeed, studies of healthy airways have demonstrated a background of 3-5% defective cilia even in airways of healthy individuals.160 Ultrastructural analysis is cumbersome requiring technical expertise, sophisticated electron optical imaging, and is only available at a limited number of centers.

Figure 3.

Electron micrographs of nasal cilia from patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) illustrating dynein defects. Far left panel illustrates ultrastructure of a normal cilium from nasal epithelium of a healthy, clinically unaffected subject. The adjacent panels from three different PCD patients illustrates defects in both dynein arms, isolated defects of outer dynein arms only, and isolated defects of inner dynein arms only.

While ultrastructural analysis has proved invaluable in the diagnosis of PCD and has been considered the “gold standard”, new studies37 are emerging to demonstrate that affected individuals can exhibit the clinical phenotype of PCD, and mutations in ciliary genes, but have normal ciliary ultrastructure. This observation points to the broadening definition of PCD which is being brought about by advances in molecular genetics. These molecular studies are important, as they support a growing awareness among researchers that PCD is an underreported syndrome perhaps, in part, because of the limitation of ciliary ultrastructural analysis.161

Ciliary motility abnormalities in PCD

The first reports by Afzelius et al.4,151 indicated spermatozoa and airway cilia from the affected individuals were totally immotile, which led to the early descriptive name, “immotile cilia syndrome”. Subsequent studies among other affected individuals reported motile, but dyskinetic, ciliary activity, which led to adoption of “primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD)”. PCD more correctly described the typical pattern of motility, and implied heterogeneous genetic basis of the syndrome. Motile, but dyskinetic, cilia usually beat out of synchrony relative to neighboring cilia. Typically, dyskinesia is accompanied by markedly attenuated ciliary beat frequency (<3 Hz at 22°C) although cases of vigorous motility have been documented. Ongoing research is studying relationships between ciliary kinetics and beat frequency, specific ultrastructural characteristics, and specific dynein mutations conferring PCD.

Nasal Nitric Oxide testing

Nasal nitric oxide (NO) measurements is emerging as a non-invasive screening test for PCD, based on multiple studies demonstrating that nasal NO production is markedly reduced (5-20% of normal) in patients with PCD.7-10,162 The exact mechanism for reduced nasal NO in PCD has yet to be elucidated, and the biologic function of nasal NO has not been fully defined. Postulated functions include regulation of ciliary motility163 and antimicrobial activity.164 Nasal NO, produced predominantly in the paranasal sinuses, is much more abundant (10 – 50 fold greater) than in the lower airways.10,162,165 Consequently, accurate measurement of nasal NO production requires specific techniques for palate closure, in order to ensure that there is no dilution of the nasal NO by air from the lower airways.134,165 While nasal NO is extremely low in patients with PCD, it is also reduced (though not as low) in patients with cystic fibrosis.134,165 Sinus disease (acute or chronic) may result in falsely diminished nasal NO levels in otherwise healthy subjects.165 Because no FDA-approved devices for measurement of nasal NO are available, nasal NO measurement is used predominantly in research studies in the United States, but has become part of the diagnostic clinical testing at centers in Europe.166 Normal values are published for children as young as six years of age.167 Recent studies have focused on standardizing techniques for measuring nasal NO especially in children under 6 years of age who are unable to cooperate with maneuvers to close the soft palate.168,169

Immunofluorescent analysis

Immunofluorescent analysis for ciliary proteins holds diagnostic potential for PCD. Recent studies showed that PCD patients with ODA defects had absence of DNAH5 staining from the entire axoneme or from the distal portion and accumulation of DNAH5 at the microtubule-organizing center, in contrast to all control individuals, including disease controls (recurrent respiratory infections unrelated to PCD) who had normal DNAH5 staining along the ciliary axoneme.52,170 This method is performed on nasal epithelial cells obtained via non-invasive trans-nasal brushing. The main advantage of this method is that it can detect the changes along the entire length of the ciliary axoneme. At present immunofluorescent staining is available at one research laboratory in Germany with limited supply of ciliary protein specific antibodies.

Genetic testing

The diagnosis of PCD is challenging due to the requirement of cumbersome ultrastructural or immunofluorescent analyses, and only a few laboratories can offer those tests. Defining biallelic mutations in trans (inheriting a mutation from each parent) in a PCD patient in the causative gene would confirm the diagnosis. But, genetic diagnosis for PCD is also challenging due to the genetic heterogeneity and the large size of PCD-causing genes. In addition, despite the identification of several of PCD causing genes, the number of PCD patients harboring mutations in some of these genes is small and thus, limits the development of a robust clinical genetic test. DNAI1 and DNAH5 appear to be major causative genes in almost 30-38% of all PCD families.33,36,44-46,48,51 Since mutations in these genes have been exclusively identified in patients with ODA defects, the mutation detection rate is higher (~50-60%) in PCD patients with ODA defects. Despite allelic heterogeneity in DNAI1 and DNAH5, mutation clusters were observed in 9 exons of DNAI1 (exons 1, 13, 16, and 17) and DNAH5 (exons 34, 50, 63, 76 and 77). Based on published reports, we estimate that analysis of the 9 exons would lead to the identification of at least one mutant allele in approximately 24% of all PCD patients. The DNA from these patients can then be sequenced to test for the second mutation. The first PCD clinical genetic assay was developed that required sequencing of only 9 exons (out of 100 exons),28,47 and a commercial laboratory subsequently developed a genetic assay that tests for the known 60 mutant alleles of DNAI1 and DNAH5. For the full listing of the laboratories offering PCD genetic tests please check (url: http://www.genetests.org/). Sequence based assays are expensive; hence, alternative approaches, are being considered such as melting curve analysis and microarray chips. The benefit of these alternative methods is the ease of addition of the new genetic mutations as they are discovered, which can assist in further increase in specificity of the genetic test.

MANAGEMENT

Medical management of lung disease

Currently, there are no therapies that have been adequately studied to definitively prove their efficacy in the treatment of PCD. Treatments that are used in clinical practice tend to be extrapolated from CF clinical trials. There is evidence, however, from the observational data of clinical case series, that early diagnosis and management of patients with PCD in a specialized PCD clinic may improve long term lung function outcomes.171 The disease management approach reported by Ellerman and Bisgaard171 followed an algorithm very similar to the CF disease management approach. A number of high quality randomized controlled trials of therapy have been published to help establish an evidence based approach to care of CF.172 CF medical management practices which have some biological rationale for extrapolation to PCD, include daily airway clearance, judicious use of antibiotics, infection control and attention to nutritional status. Generally antibiotics are used acutely with disease exacerbation and are prescribed according to bacteria grown in the last sputum culture. Chronic suppressive use of antibiotics would be considered, if a patient is repeatedly growing Pseudomonas aeruginosa in the sputum. There are no data to recommend for or against agents that improve mucociliary clearance or inflammation in PCD. Clinical utility of bronchodilators has not been demonstrated in PCD. Monitoring for progression of lung disease should be an important part of the regular clinic visit. At present, there are no clinical practice guidelines to direct frequency of clinic visits or additional testing. Based on the PCD management approach reported by Ellerman and Bisgaard 171 and clinical practices used for cystic fibrosis, tests to consider include lung function testing and respiratory cultures every 3-6 months and lung imaging on an annual or biannual basis. Consideration should be given for obtaining a chest CT, instead of a plain chest radiograph, at the time of diagnosis or at intervals during follow-up, since chest CT is the gold standard for diagnosing bronchiectasis.173 The additional radiation of a chest CT must be weighed against the potential “benefit” of early recognition of bronchiectasis.

Surgical management of lung disease

Lobectomy is generally not recommended since PCD is a generalized airway disease. However, lobectomy has been shown to improve symptoms and to have low perioperative mortality in case series of selected patients with PCD174 and idiopathic bronchiectasis.175 Consideration for lobectomy should be limited to selected patients with severe localized bronchiectasis with frequent febrile episodes or, severe hemoptysis and failure of conservative medical management with antibiotics, airway clearance and embolotherapy.174 Surgery should only be performed in centers with specialized expertise. Lung transplantation is an option once a patient has reached end-stage lung disease. There are at least 9 reported cases of successful lung transplantation in patients with PCD.176 There are no longitudinal survival data published in order to develop criteria for referral for lung transplantation in PCD.

Management of chronic otitis media

The management of serous otitis and recurrent otitis media in PCD is controversial. While some otolaryngologists argue that myringotomy tubes can be harmful and should be avoided, others argue that myringotomy tubes allow hearing and speech to develop in the infant or toddler with hearing loss due to chronic serous otitis. The proponents against tubes suggest that they cause annoying chronic mucopurulent drainage of the middle ear, pose a risk of chronic middle ear perforation and that the natural history of hearing loss is that it normalizes by age 12 years, making these procedures unnecessary.177 On the other hand, mucopurulent drainage responds to treatment with local antibiotics and there is no hard data to show that chronic middle ear perforation is a common complication. In addition, delayed speech development can have profound effects on language development and subsequent school performance. Hearing aids may be used instead of myringotomy tubes, however they are sometimes not well tolerated in the preschool age group.

Specialized PCD diagnostic and treatment centers

A multi-disciplinary “disease management” approach to chronic disease is now well recognized to be the most successful strategy for improving patient outcomes.178 Key elements of advancing disease management include research, performance measurement and quality improvement.179 When one considers that PCD is a chronic airways disease with many similarities to CF including a similar (albeit slower) progression of lung function deterioration and lower airways bacterial colonization with age,9 the notion of a need for specialty “PCD Centers” seems obvious. Improvement in survival and quality of life over the last 30 years for patients with CF can be largely attributed to the better treatment developed at major CF centers.180 In addition to improved clinical outcomes, disease-specific centers are generally regarded favorably by patients and have numerous psychosocial benefits, including the opportunity to meet other families/patients with the same rare disease and share experiences.181 Finally, major CF centers also provide a natural infrastructure for the conduct of clinical research to further improve outcomes.139 Good medical management in a specialized PCD diagnostic and treatment center will probably provide the PCD patient with the best chance for preservation of lung function over time.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are indebted to the PCD patients and families, and would like to thank Ms. Michele Manion, who founded the US PCD Foundation. We are indebted to the principle investigators and the coordinators of the “Genetic Disorders of Mucociliary Clearance Consortium” that is part of the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network (url: http://rarediseasesnetwork.epi.usf.edu/gdmcc/index.htm), including Dr. Kenneth Olivier, Ms. Reginald Claypool, MS. Tanya Glaser, Ms. Kate Birkenkamp, and Ms. Beth Melia (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Bethesda, MD), Dr. Jeffrey Atkinson and Ms. Jane Quante (Washington University in St. Louis, Mo), Dr. Scott Sagel and Ms. Shelley Mann (The Children’s Hospital Colorado, Denver, CO), Drs. Margaret Rosenfeld, Ronald Gibson and Moira Aitken and Ms. Sharon McNamara (Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center, Seattle, WA), Dr. Carlos Milla and Ms. Jacquelyn Zirbez (Stanford University Medical Center, Palo Alto, CA), Ms. Susan Minnix (The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, NC), and Ms. Donna Wilkes (The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). In addition, all the authors belong to this consortium. Authors thank Drs. Karen Weck, Jessica Booker, and Kay Chao (Molecular Genetics Laboratory, UNC Hospitals, NC) for the continued work on PCD clinical genetics testing. Authors also thank Drs. Milan Hazucha, Larry Ostrowski, Peadar Noone, Adriana Lori, Hilda Metjian, Deepika Polineni, Adam Shapiro, Ms. Kim Burns, Mr. Michael Chris Armstrong, Mr. Kunal Chawla, Ms. Elizabeth Godwin and Ms. Cindy Sell from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, NC. We also thank Dr. Peter Satir (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY) for providing information regarding the primary cilium structure.

Disclosure of Funding:

M.W.L., J.L.C., T.W.F., S.D.D., S.D.D., M.R.K., and M.A.Z. are supported by National Institutes of Health grant U54RR019480

M.R.K. and M.A.Z. are supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 HL071798

T.W.F. is supported by R01 HL08265 and Children’s Discovery Institute

J.E.P. is supported by National Institutes of Health training grant 5 T32 HL 007106 -32

J.L.C. is supported by Clinical Innovator Award by Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

None

REFERENCES

- 1.Katsuhara K, Kawamoto S, Wakabayashi T, Belsky JL. Situs inversus totalis and Kartagener’s syndrome in a Japanese population. Chest. 1972;61:56–61. doi: 10.1378/chest.61.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torgersen J. Situs inversus, asymmetry, and twinning. Am J Hum Genet. 1950;2:361–370. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kartagener M. Zur pathogenese der bronkiectasien: bronkiectasien bei situs viscerum inversus. Beitr Klin Tuberk. 1933;82:489–501. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afzelius BA. A human syndrome caused by immotile cilia. Science. 1976;193:317–319. doi: 10.1126/science.1084576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eliasson R, Mossberg B, Camner P, Afzelius BA. The immotile-cilia syndrome. A congenital ciliary abnormality as an etiologic factor in chronic airway infections and male sterility. N Engl J Med. 1977;297:1–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197707072970101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedersen H, Mygind N. Absence of axonemal arms in nasal mucosa cilia in Kartagener's syndrome. Nature. 1976;262:494–495. doi: 10.1038/262494a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corbelli R, Bringolf-Isler B, Amacher A, Sasse B, Spycher M, Hammer J. Nasal nitric oxide measurements to screen children for primary ciliary dyskinesia. Chest. 2004;126:1054–1059. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.4.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Narang I, Ersu R, Wilson NM, Bush A. Nitric oxide in chronic airway inflammation in children: diagnostic use and pathophysiological significance. Thorax. 2002;57:586–589. doi: 10.1136/thorax.57.7.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noone PG, Leigh MW, Sannuti A, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: Diagnostic and phenotypic features. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:459–467. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200303-365OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wodehouse T, Kharitonov SA, Mackay IS, Barnes PJ, Wilson R, Cole PJ. Nasal nitric oxide measurements for the screening of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:43–47. doi: 10.1183/09031936.03.00305503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodenough UW, Heuser JE. Outer and inner dynein arms of cilia and flagella. Cell. 1985;41:341–342. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mastronarde DN, O’Toole ET, McDonald KL, McIntosh JR, Porter ME. Arrangement of inner dynein arms in wild-type and mutant flagella of Chlamydomonas. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:1145–1162. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.5.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Satir P, Christensen ST. Overview of structure and function of mammalian cilia. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:377–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.040705.141236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilula NB, Satir P. The ciliary necklace. A ciliary membrane specialization. J Cell Biol. 1972;53:494–509. doi: 10.1083/jcb.53.2.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carson JL, Collier AM, Knowles MR, Boucher RC, Rose JG. Morphometric aspects of ciliary distribution and ciliogenesis in human nasal epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:6996–6999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.6996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou H, Wang X, Brighton L, Hazucha M, Jaspers I, Carson JL. Increased nasal epithelial ciliary beat frequency associated with lifestyle tobacco smoke exposure. Inhal Toxicol 2009. doi: 10.1080/08958370802555898. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li D, Shirakami G, Zhan X, Johns RA. Regulation of ciliary beat frequency by the nitric oxide-cyclic guanosine monophosphate signaling pathway in rat airway epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;23:175–181. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.2.4022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wyatt TA, Spurzem JR, May K, Sisson JH. Regulation of ciliary beat frequency by both PKA and PKG in bovine airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:L827–L835. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.275.4.L827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dirksen ER, Sanderson MJ. Regulation of ciliary activity in the mammalian respiratory tract. Biorheology. 1990;27:533–545. doi: 10.3233/bir-1990-273-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanderson MJ, Dirksen ER. Mechanosensitive and beta-adrenergic control of the ciliary beat frequency of mammalian respiratory tract cells in culture. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;139:432–440. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.2.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pazour GJ, Witman GB. The vertebrate primary cilium is a sensory organelle. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pazour GJ, Agrin N, Walker BL, Witman GB. Identification of predicted human outer dynein arm genes - candidates for primary ciliary dyskinesia genes. J Med Genet. 2006;43:62–73. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.033001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang K, Diener DR, Mitchell A, Pazour GJ, Witman GB, Rosenbaum JL. Function and dynamics of PKD2 in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii flagella. J Cell Biol. 2007;179:501–514. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200704069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pazour GJ, Dickert BL, Vucica Y, et al. Chlamydomonas IFT88 and its mouse homologue, polycystic kidney disease gene tg737, are required for assembly of cilia and flagella. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:709–718. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.3.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beales PL, Bland E, Tobin JL, et al. IFT80, which encodes a conserved intraflagellar transport protein, is mutated in Jeune asphyxiating thoracic dystrophy. Nat Genet. 2007;39:727–729. doi: 10.1038/ng2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Badano JL, Mitsuma N, Beales PL, Katsanis N. The Ciliopathies: An Emerging Class of Human Genetic Disorders. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:125–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fliegauf M, Benzing T, Omran H. When cilia go bad: cilia defects and ciliopathies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:880–893. doi: 10.1038/nrm2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zariwala MA, Knowles MR, Omran H. Genetic defects in ciliary structure and function. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:423–450. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.040705.141301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blouin JL, Meeks M, Radhakrishna U, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia: a genome-wide linkage analysis reveals extensive locus heterogeneity. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:109–118. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bartoloni L, Blouin JL, Pan Y, et al. Mutations in the DNAH11 (axonemal heavy chain dynein type 11) gene cause one form of situs inversus totalis and most likely primary ciliary dyskinesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10282–10286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152337699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duriez B, Duquesnoy P, Escudier E, et al. A common variant in combination with a nonsense mutation in a member of the thioredoxin family causes primary ciliary dyskinesia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:3336–3341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611405104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Omran H, Kobayashi D, Olbrich H, et al. Ktu/PF13 is required for cytoplasmic pre-assembly of axonemal dyneins. Nature. 2008;456:611–616. doi: 10.1038/nature07471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pennarun G, Escudier E, Chapelin C, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in a human gene related to Chlamydomonas reinhardtii dynein IC78 result in primary ciliary dyskinesia. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:1508–1519. doi: 10.1086/302683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pennarun G, Chapelin C, Escudier E, et al. The human dynein intermediate chain 2 gene (DNAI2): cloning, mapping, expression pattern, and evaluation as a candidate for primary ciliary dyskinesia. Hum Genet. 2000;107:642–649. doi: 10.1007/s004390000427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loges NT, Olbrich H, Fenske L, et al. DNAI2 mutations cause primary ciliary dyskinesia with defects in the outer dynein arm. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:547–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Olbrich H, Haffner K, Kispert A, et al. Mutations in DNAH5 cause primary ciliary dyskinesia and randomization of left-right asymmetry. Nat Genet. 2002;30:43–44. doi: 10.1038/ng817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwabe GC, Hoffmann K, Loges NT, et al. Primary ciliary dyskinesia associated with normal axoneme ultrastructure is caused by DNAH11 mutations. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:289–298. doi: 10.1002/humu.20656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fliegauf M, Omran H. Novel tools to unravel molecular mechanisms in cilia-related disorders. Trends Genet. 2006;22:241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li JB, Gerdes JM, Haycraft CJ, et al. Comparative genomics identifies a flagellar and basal body proteome that includes the BBS5 human disease gene. Cell. 2004;117:541–552. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luck DJ. Genetic and biochemical dissection of the eucaryotic flagellum. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:789–794. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.3.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ostrowski LE, Blackburn K, Radde KM, et al. A proteomic analysis of human cilia: identification of novel components. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:451–465. doi: 10.1074/mcp.m200037-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pazour GJ, Agrin N, Leszyk J, Witman GB. Proteomic analysis of a eukaryotic cilium. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:103–113. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Piperno G, Huang B, Luck DJ. Two-dimensional analysis of flagellar proteins from wild-type and paralyzed mutants of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:1600–1604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.4.1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guichard C, Harricane MC, Lafitte JJ, et al. Axonemal dynein intermediate-chain gene (DNAI1) mutations result in situs inversus and primary ciliary dyskinesia (Kartagener syndrome) Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:1030–1035. doi: 10.1086/319511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zariwala M, Noone PG, Sannuti A, et al. Germline mutations in an intermediate chain dynein cause primary ciliary dyskinesia. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:577–583. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.5.4619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zariwala MA, Leigh MW, Ceppa F, et al. Mutations of DNAI1 in Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia: Evidence of founder effect in a common mutation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:858–866. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200603-370OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zariwala M, Knowles M, Leigh MW. Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2016.04.008. GeneReviews at GeneTests: Medical Genetics information Resource [database online]:Copyrights University of Washington, Seattle, 1993-2009-avialable at: http://www.genetests.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Failly M, Saitta A, Munoz A, et al. DNAI1 mutations explain only 2% of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Respiration. 2008;76:198–204. doi: 10.1159/000128567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Omran H, Haffner K, Volkel A, et al. Homozygosity mapping of a gene locus for primary ciliary dyskinesia on chromosome 5p and identification of the heavy dynein chain DNAH5 as a candidate gene. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;23:696–702. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.5.4257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bush A, Ferkol T. Movement: the emerging genetics of primary ciliary dyskinesia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:109–110. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2604002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hornef N, Olbrich H, Horvath J, et al. DNAH5 Mutations are a Common Cause of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia with Outer Dynein Arm Defects. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:120–126. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200601-084OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fliegauf M, Olbrich H, Horvath J, et al. Mislocalization of DNAH5 and DNAH9 in respiratory cells from patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:1343–1349. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200411-1583OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bartoloni L, Mitchison H, Pazour GJ, et al. No deleterious mutations were found in three genes (HFH4, LC8, IC2) on human chromosome 17q in patients with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:P-484. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Supp DM, Witte DP, Potter SS, Brueckner M. Mutation of an axonemal dynein affects left-right asymmetry in inversus viscerum mice. Nature. 1997;389:963–966. doi: 10.1038/40140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Supp DM, Brueckner M, Kuehn MR, et al. Targeted deletion of the ATP binding domain of left-right dynein confirms its role in specifying development of left-right asymmetries. Development. 1999;126:5495–5504. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.23.5495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Castleman VH, Romio L, Chodhari R, et al. Mutations in radial spoke head protein genes RSPH9 and RSPH4A cause primary ciliary dyskinesia with central-microtubular-pair abnormalities. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang P, Diener DR, Yang C, et al. Radial spoke proteins of Chlamydomonas flagella. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:1165–1174. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]