Abstract

T follicular helper (TFH) cells provide critical help to B cells during humoral immune responses. Here we report that mice with T cell-specific deletion of miR-17~92 family miRNAs (tKO mice) exhibited severely compromised TFH differentiation, germinal center formation, antibody responses, and failed to control chronic virus infection. Conversely, T cell-specific miR-17~92 transgenic mice spontaneously accumulated TFH cells and developed fatal immunopathology. Mechanistically, miR-17~92 family miRNAs control CD4+ T cell migration into B cell follicles by regulating ICOS-PI3K signaling intensity through suppressing the expression of the Akt phosphatase Phlpp2. These findings demonstrate that miR-17~92 family microRNAs play an essential role in TFH differentiation and establish Phlpp2 as an important mediator of their function in this process.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenously encoded small RNAs of ~22 nucleotides in length that play important roles in a large diversity of biological processes1,2,3. Genetic studies have shown that miRNAs are important regulators in the immune system4,5. However, the functions of individual miRNAs during lymphocyte development and effector cell differentiation remain largely unknown. miR-17~92, miR-106a~363, and miR-106b~25 are members of a family of highly conserved miRNAs, the miR-17~92 family6. Together, these three clusters encode for thirteen distinct miRNAs, which belong to four miRNA subfamilies (miR-17, miR-18, miR-19, and miR-92 subfamilies). Members in each subfamily share a common seed region (nucleotides 2-7 of mature miRNAs) and are thought to have similar functions. Germline deletion of miR-17~92 led to perinatal lethality of mutant mice. While ablation of miR-106a~363 or miR-106b~25 had no obvious phenotypic consequence, compound mutant embryos lacking both miR-17~92 and miR-106b~25 died before embryonic day 15, with defective development of lung, heart, central nervous system, and B lymphocytes7. These genetic studies revealed essential and overlapping functions of miR-17~92 family miRNAs in many developmental processes.

T cell help is essential for humoral immune responses. A distinct CD4+ effector T cell subset, T follicular helper cells (TFH), provides this help to B cells8. However, molecular mechanisms underlying TFH differentiation are still largely unknown. Bcl-6 was identified as a critical transcription factor regulating TFH differentiation9,10,11. A recent study reported that Bcl-6 represses the expression of miR-17~92, which targets the expression of CXCR5, a chemokine receptor essential for CD4+ T cell migration to B cell follicles, and suggested that miR-17~92 functions as a negative regulator of TFH differentiation (the “repression of the repressors” model)11. Here we explore the role of miR-17~92 family miRNAs in TFH differentiation and germinal center reaction using mice with loss- and gain-of function mutations for those miRNAs. We found that these miRNAs function as critical positive regulators of TFH differentiation by controlling CD4+ T cell migration into B cell follicles, and identified Phlpp2 as an important mediator of their function in this process.

RESULTS

The miR-17~92 family regulates TFH differentiation

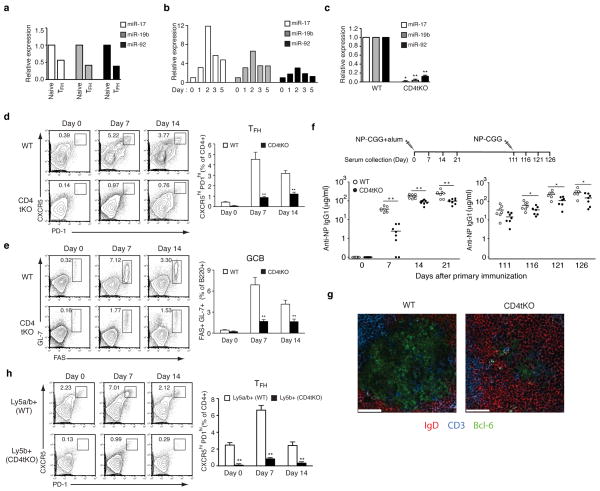

We first examined the expression of miR-17~92 family miRNAs during TFH differentiation. Consistent with a previous report11, their expression in TFH cells was lower than in naive CD4+ T cells at day 7 after OVA+Alum+LPS immunization (Fig. 1a). When naive CD4+ T cells were activated in vitro, the expression of these miRNAs was increased during the first 2 days, peaked around day 2, and decreased afterwards (Fig. 1b). These results suggest that miR-17~92 family miRNA expression is induced early in T cell activation and then repressed upon completion of the TFH differentiation program. To investigate the role of miR-17~92 family miRNAs in TFH differentiation, we generated CD4Cre;miR-17~92fl/fl;miR-106a~363−/−;miR-106b~25−/− mice (termed CD4tKO hereafter) and confirmed loss of expression of these miRNAs in T cells (Fig. 1c)7,12. CD4tKO mice exhibited grossly normal lymphocyte development and follicular structures in lymphoid organs (data not shown). We assessed TFH differentiation by immunizing mice with a T cell-dependent antigen, the haptenated protein, 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenyl-ovalbumin (NP-OVA), precipitated in alum together with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). CD4tKO mice exhibited severely impaired TFH (Fig. 1d) and germinal center B cell (GCB) (Fig. 1e) differentiation, and produced less NP-specific IgM (2~3 fold less on day 7, data not shown) and IgG1 (15 fold less on day 7 and 2~3 fold less on days 14 and 21) antibodies than did wild type (WT) mice (Fig. 1f, left panel). CD4tKO mice also showed a defective secondary antibody response (2 fold less than WT at all time points) upon re-immunization, suggesting that the miR-17~92 family miRNAs regulate not only the initial formation and function of TFH cells, but also the establishment of long-lived protective CD4+ T cell dependent B cell responses (Fig. 1f, right panel). Immunohistochemistry analysis revealed a drastic reduction in the number and size of germinal centers in the spleen of immunized CD4tKO mice (Fig. 1g and data not shown). In contrast, miR-17~92fl/fl;miR-106a~363−/−;miR-106b~25−/− mice (with germline deletion of both miR-106a~363 and miR-106b~25 miRNA clusters, termed dKO mice) showed mild reductions in TFH differentiation, GCB formation, and antibody production (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c). Similarly, CD4Cre;miR-17~92fl/fl mice (termed sKO mice) also showed modest reductions in TFH and GCB differentiation upon protein antigen immunization though more pronounced than the dKO mice (Supplementary Fig. 2). These results revealed essential and overlapping functions of the miR-17~92 family miRNA clusters during TFH differentiation.

Figure 1.

miR-17~92 family miRNAs regulate TFH differentiation during protein antigen immunization. (a–c) Expression of miR-17~92 family miRNAs in sorted naive CD4+ T and CXCR5hiPD1hi TFH cells (a), naive and activated WT CD4+ T cells (b), and CD4tKO CD4+ T cells (c, n=3) was determined by Northern blot. Numbers indicate miRNA/U6 ratios normalized to naive CD4+ T cells. (d,e) CXCR5hiPD1hi TFH (d) and FAS+GL-7+ GCB cells (e) were analyzed at days 7 and 14 after intraperitoneal (i.p) immunization with NP-OVA+Alum+LPS (n=6 per group). (f) WT and CD4tKO mice were immunized with 10μg NP-CGG+Alum (i.p.), followed by secondary immunization with 5μg NP-CGG (i.p.) on day 111 after primary immunization. Serum was collected at indicated time points. NP-specific IgG1 antibody concentration was determined by ELISA (n=8 per group). (g) Immunohistochemistry analysis of germinal centers. Spleens of NP-OVA+Alum+LPS immunized mice were examined at day 7 after immunization (i.p). Scale bar, 50 μm. (h) Lethally irradiated B6 Ly5a mice were reconstituted with B6 Ly5a/b and tKO Ly5b bone marrow cells (1:1), immunized with NP-OVA+Alum+LPS (i.p) at eight weeks after reconstitution, and TFH differentiation in the spleen was analyzed at days 7 or 14 after immunization. Data are representative of two (a) and three (b) independent experiments. All graphs are shown as means± s.e.m. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

To examine whether the compromised TFH differentiation in CD4tKO mice reflected a cell-intrinsic miRNA function, we generated WT:CD4tKO mixed bone marrow chimeras and immunized them with NP-OVA+Alum+LPS. Although WT CD4+ T cells differentiated into TFH cells, CD4tKO CD4+ T cells contributed very little to the TFH cell pool in chimeric mice (Fig. 1h). In contrast, dKO CD4+ T cells and B cells underwent relatively normal TFH and GCB cell differentiation in WT:dKO chimeras (Supplementary Fig. 1d). These results demonstrate that miR-17~92 family miRNAs function as CD4+ T cell-intrinsic positive regulators of TFH cell differentiation.

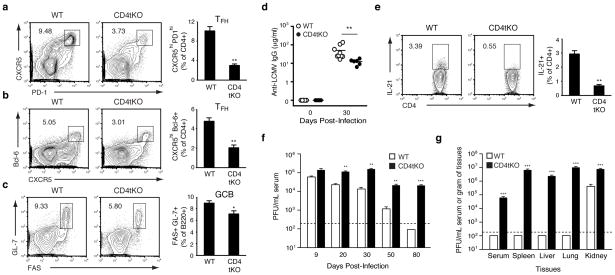

CD4tKO mice do not control chronic viral infection

Recent studies suggested that TFH cells play important roles in controlling chronic virus infection13,14. Infection of mice with a high dose of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) clone-13 (2 x 106 PFU i.v.) resulted in a chronic infection, with virus persisting in multiple tissues for 3–4 months15. Infection of CD4tKO mice with LCMV clone-13 resulted in reduced TFH differentiation (Fig. 2a, b), GCB formation (Fig. 2c), and 3~6 fold reduction in production of LCMV-specific IgG antibodies (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 3a). CD4tKO CD4+ T cells were severely impaired in their ability to produce IL-21 (Fig. 2e), a cytokine critical for TFH differentiation, GCB formation, and functional CD8+ T cell responses during chronic viral infection16,17,18,19,20,21,22. We also investigated CD8+ T cell responses during LCMV clone-13 infection. No significant difference in the percentage or total numbers of virus-specific GP33- or GP276-CD8+ T cells was observed when comparing CD4tKO to WT mice (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). However, virus specific CD4tKO CD8+ T cells expressed elevated levels of the negative immune regulatory molecule PD-1, suggesting a more exhausted state (Supplementary Fig. 3d)23, and displayed a smaller percentage of IFN-γ+TNF-α+ double producing cells (Supplementary Fig. 3e, f). Finally, we examined whether the impaired development of TFH and GCB cells, compromised antibody and cytokine production, and elevated CD8+ T cell exhaustion in CD4tKO mice led to a reduced capacity to control LCMV clone-13 infection. LCMV clone-13 infected CD4tKO mice harbored elevated titers of virus in the serum at days 20, 30 and 50 post-infection compared to WT and dKO mice (Fig. 2f and dKO data not shown). At day 80 post-infection when all WT and dKO mice had completely cleared the virus from the serum, CD4tKO mice maintained greater than 4-logs of virus (Fig. 2f and dKO data not shown). Moreover, CD4tKO mice harbored considerable viral loads in serum and multiple tissues at day 140 post-infection, a time when virus was eliminated in all tissues except kidney in WT and dKO mice (Fig. 2g and dKO data not shown). Taken together, our results demonstrate that CD4tKO mice exhibited defective TFH differentiation during LCMV clone-13 infection and failed to control the virus.

Figure 2.

miR-17~92 family miRNAs regulate TFH differentiation during chronic viral infection. (a–e) CXCR5hiPD1hi (a) and CXCR5hiBcl-6+ (b) TFH cells, FAS+GL-7+ GCB cells (c), and IL-21 producing cells (e) were analyzed in spleen of mice at day 30 after LCMV clone-13 infection (a–c, n=8 per group; e, n=4~5 per group). (d) anti-LCMV IgG concentration in serum was determined by ELISA. (f,g) LCMV clone-13 infected mice were bled at the indicated times (f), euthanized at day 140 post-infection (g), and viral titers in serum and tissues were measured by plaque assay (representatives of two independent experiments). All graphs are shown as means± s.e.m. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001.

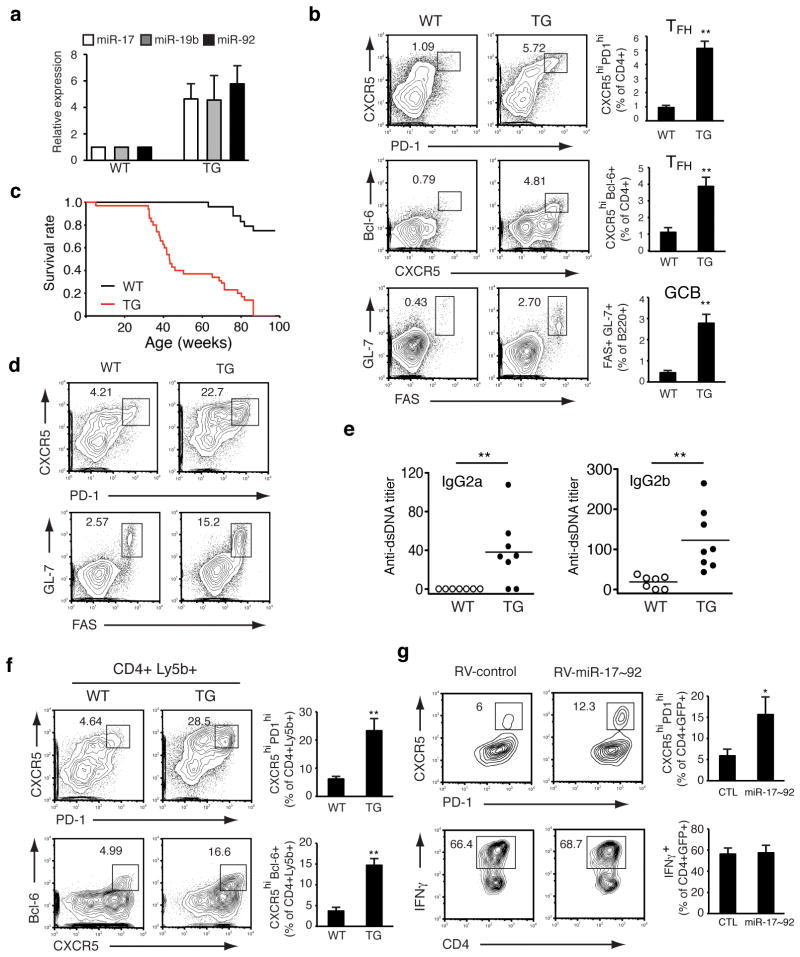

Accumulation of TFH cells in miR-17~92 transgenic mice

Next, we examined whether miR-17~92 over-expression was sufficient to promote the generation of functional TFH cells. We developed transgenic mice (CD4Cre;miR-17~92 Tg/Tg, termed TG hereafter) in which miR-17~92 expression was increased by 4~6 fold in CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3a)24. Young TG mice had increased numbers of effector/memory CD44+CD4+ T cells in the spleen (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). These young TG mice exhibited spontaneous TFH differentiation and GCB formation, whereas the percentages of other T helper (TH) cell subsets among CD44+CD4+ T cells were not affected (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 4c, d). These spontaneously generated TFH-like cells expressed Bcl-6, the signature transcription factor for TFH cells (Fig. 3b). TFH cell expansion has been observed in a subset of lupus patients and in sanroque mice, a mutant mouse strain that spontaneously develops systemic autoimmunity, and was shown to play a causative role in the latter25,26,27. We monitored a cohort of 24 WT and 35 TG mice for more than 20 months for disease development. All TG mice died prematurely, with an average life span of 40 weeks (Fig. 3c). Examination of sick TG mice revealed that they developed splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy (Supplementary Fig. 4e), accumulated TFH and GCB cells (Fig. 3d) in lymphoid organs, produced autoantibodies to double stranded DNA (Fig. 3e), and exhibited lymphocyte infiltration into non-lymphoid organs (Supplementary Fig. 4f). Therefore, T cell-specific over-expression of miR-17~92 caused spontaneous TFH differentiation and fatal immunopathology.

Figure 3.

Spontaneous accumulation of TFH cells in T cell-specific miR-17~92 transgenic mice. (a) Expression levels of miR-17~92 family miRNAs in TG CD4+ T cells (n=3) were determined by Northern blot. Numbers indicate miRNA/U6 ratios normalized to naive WT CD4+ T cells. (b) CXCR5hiPD1hi TFH (upper), CXCR5hi Bcl-6+ TFH (middle) and FAS+GL-7+ GCB cells (lower) were analyzed in the spleen of 6~8 week old non-immunized mice (n=5~7 per group). (c) Survival curves of TG (n=35) and WT mice (n=24). (d) TFH (upper) and GCB (lower) cells in splenocytes of 8 month old WT and TG mice. (e) Serum anti-dsDNA antibody concentration in TG and WT mice at 6–8 months of age was determined by ELISA. The serum titers of aged MRL-lpr/lpr mice were arbitrary set at 1x103. (f) Lethally irradiated B6.Rag1−/− mice were reconstituted with B6 (Ly5a) and WT or TG (Ly5b) mixed bone marrow cells (1:1), and spontaneous TFH cell differentiation in the spleen was analyzed at 3 months after reconstitution (n=3 per group). (g) WT naive CD4+ T cells were transduced with RV-miR-17~92 or RV-control and activated in vitro in the presence of anti-IL-4, anti-IFNγ, IL-6 and IL-21 for TFH (upper panel) or anti-IL-4 and IL-12 for TH1 (lower panel) differentiation. GFP+ cells were gated and plotted (representatives of three independent experiments). Bcl-6 expression in in vitro differentiated TFH cells is presented in Supplementary Fig. 5. All graphs are shown as means± s.e.m. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

To demonstrate that enhanced TFH differentiation in TG mice was intrinsic to CD4+ T cells, we generated WT:TG mixed bone marrow chimeras. Three months after reconstitution, a significantly increased proportion of TG CD4+ T cells acquired TFH phenotypes, whereas most WT CD4+ T cells remained undifferentiated (Fig. 3f). In addition, retroviral over-expression of miR-17~92 in naive WT CD4+ T cells led to a two-fold increase in TFH differentiation in vitro, whereas TH1 differentiation was not affected (Fig. 3g). Retroviral miR-17~92 over-expression promoted TFH differentiation without increasing Bcl-6 protein in the differentiated CXCR5+PD1hi TFH cells (Supplementary Fig. 5). This data suggests that the Bcl-6 protein level is not directly controlled by miR-17~92 family miRNAs. Taken together, these results show that miR-17~92 over-expression is sufficient to drive TFH differentiation and this effect is CD4+ T cell intrinsic.

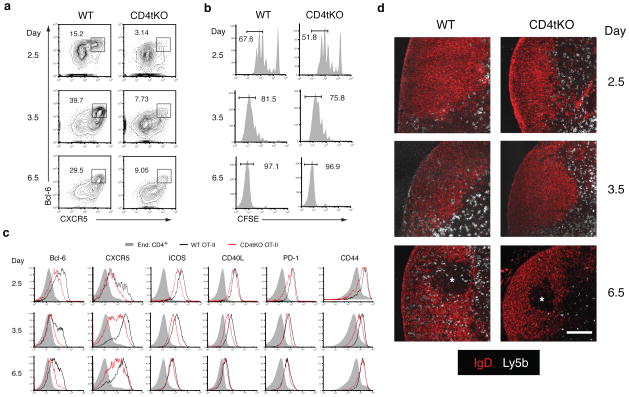

CD4tKO CD4+ T cells do not migrate into B cell follicles

We introduced the OT-II T cell receptor transgene to CD4tKO mice to study the effect of the miR-17~92 family miRNAs on antigen-specific CD4+ T cells during TFH differentiation28. We adoptively transferred carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled naive Ly5b WT or CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ T cells into B6.Ly5a recipients, immunized the recipients with OVA+alum, and analyzed transferred OT-II CD4+ T cells at various time points. In agreement with our previous results, CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ T cells failed to differentiate into CXCR5hiBcl-6+ TFH cells effectively (Fig. 4a, day 6.5). We examined cell proliferation, activation marker up-regulation, and the expression of other molecules functionally important for TFH differentiation on days 2.5, 3.5, and 6.5 post immunization. The proliferation of CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ T cells was similar to their WT counterparts (Fig. 4b). The up-regulation of activation markers (CD44, ICOS, PD-1, and CD40L) was slightly reduced on days 2.5 and 3.5, but reached the WT levels by day 6.5 (Fig. 4c). Consistent with a previous report29, Bcl-6 expression was up-regulated in almost all WT OT-II CD4+ T cells on day 2.5, with a fraction of them expressing CXCR5 (day 2.5, Fig. 4a, c). Subsequently, Bcl-6 expression was down-regulated in a large majority of WT OT-II CD4+ T cells, with about 30% of them remaining positive for both Bcl-6 and CXCR5, which presumably differentiated into TFH cells (days 3.5 and 6.5, Fig. 4a, c). Importantly, the up-regulation of Bcl-6 in CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ T cells was severely impaired throughout the whole period of observation, with a much smaller fraction of those cells becoming CXCR5hi Bcl-6+ TFH cells (Fig. 4a, c). On day 6.5, the expression levels of Bcl-6 and CXCR5 in CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ cells remained lower than in WT OT-II CD4+ cells (Fig. 4c). We also examined the location of CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ cells in draining lymph nodes during immune responses. On day 2.5 after immunization, both WT and CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ cells had proliferated and resided in the T cell zone (Fig. 4b, d, day 2.5). There was almost a complete lack of CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ T cells in B cell follicles and germinal centers on days 3.5 and 6.5, when WT OT-II CD4+ T cells have migrated into these areas en masse (Fig. 4d). These results indicate that CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ T cells lose the ability to migrate to B cell follicles and germinal centers.

Figure 4.

The effect of miR-17~92 family miRNAs on antigen-specific CD4+ T cells during in vivo TFH differentiation. (a–d) CFSE labeled or unlabeled Ly5b+ WT or CD4tKO naive OT-II CD4+ T cells were transferred into B6.Ly5a mice, which were subsequently immunized with OVA+Alum subcutaneously. TFH differentiation (a), cell proliferation (b), expression of activation markers (c), and localization (d) of adoptively transferred Ly5b+ OT-II CD4+ T cells in inguinal lymph nodes were analyzed by flow cytometry (a–c) or immunohistochemistry (d) at indicated times (3–5 mice per group). IgD+ area, IgD− area, and * indicate B cell follicle, T cell zone, and germinal center, respectively. Scale bar, 100 μm (d).

The miR-17~92 family regulates TFH cell generation after activation

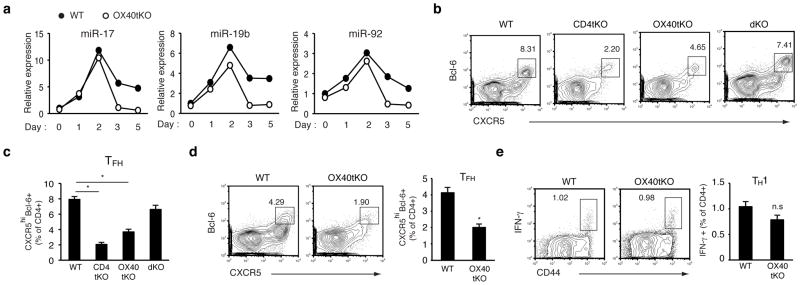

The delayed up-regulation of activation markers (CD44, ICOS, PD-1, and CD40L) and the compromised induction of Bcl-6 and CXCR5 on day 2.5 of the immune response show that CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ T cells exhibit early activation defects (Fig. 4a, c), which may indirectly compromise TFH differentiation. To examine this possibility, we generated OX40Cre;miR-17~92fl/fl;miR-106a~363−/−;miR-106b~25−/− mice (termed OX40tKO hereafter), in which OX40Cre is induced upon T cell activation and deletes the miR-17~92 gene specifically in activated CD4+ T cells. Northern Blot analysis of in vitro activated CD4+ T cells showed that the depletion of miR-17~92 started on day 2 and completed on day 3–5 (Fig. 5a). OX40tKO mice exhibited a clear TFH differentiation defect upon NP-OVA+LPS+Alum immunization (Fig. 5b, c), although the defect was milder than that in CD4tKO mice, probably reflecting a modest role of the miR-17~92 family miRNAs during the early phase of T cell activation. These results clearly demonstrate that the miR-17~92 family miRNAs play an essential role in TFH differentiation beyond the initial phase of T cell activation.

Figure 5.

MiR-17~92 family miRNAs specifically regulate TFH differentiation beyond the initial phase of T cell activation. (a) Expression of miR-17~92 family miRNAs in naive and in vitro activated WT and OX40tKO CD4+ T cells were determined by Northern blot (representative of two independent experiments). Numbers indicate miRNA/U6 ratios normalized to naive WT CD4+ T cells. (b–c) CXCR5hiBcl-6+ TFH cells in the spleen were analyzed at day 7 after intraperitoneal (i.p) immunization with OVA+Alum+LPS (n=4~10 per group). Representative flow cytometry plots are shown in (b) and combined bar graphs for TFH are shown in (c). (d–e) CXCR5hiBcl-6+ TFH (d) and IFN-γ+ TH1 cells (e) were analyzed at day 8 after LCMV Armstrong infection (n=4~5 per group). Splenocytes were re-stimulated with gp61 peptide loaded APCs to detect antigen specific IFN-γ+ TH1 cells. All graphs are shown as means± s.e.m. *, p < 0.01; n.s., not significant (p >0.05).

We further investigated whether this role of the miR-17~92 family miRNAs is specific for TFH differentiation. We infected OX40tKO mice with LCMV Armstrong strain, which causes acute infection and promotes the differentiation of CD4+ T cells into both TFH and TH1 subsets. On day 8 post infection, OX40tKO mice exhibited severely compromised TFH differentiation, whereas TH1 differentiation was only slightly reduced (Fig. 5d, e). Taken together, our results show that the miR-17~92 family miRNAs specifically regulate TFH differentiation beyond the initial phase of T cell activation. As follicular localization following activation is a critical step of the TFH differentiation program, and the deficiency of miR-17~92 family miRNAs severely impaired this process (Fig. 4d), these miRNAs may control TFH differentiation by specifically regulating molecular events underlying the migration process.

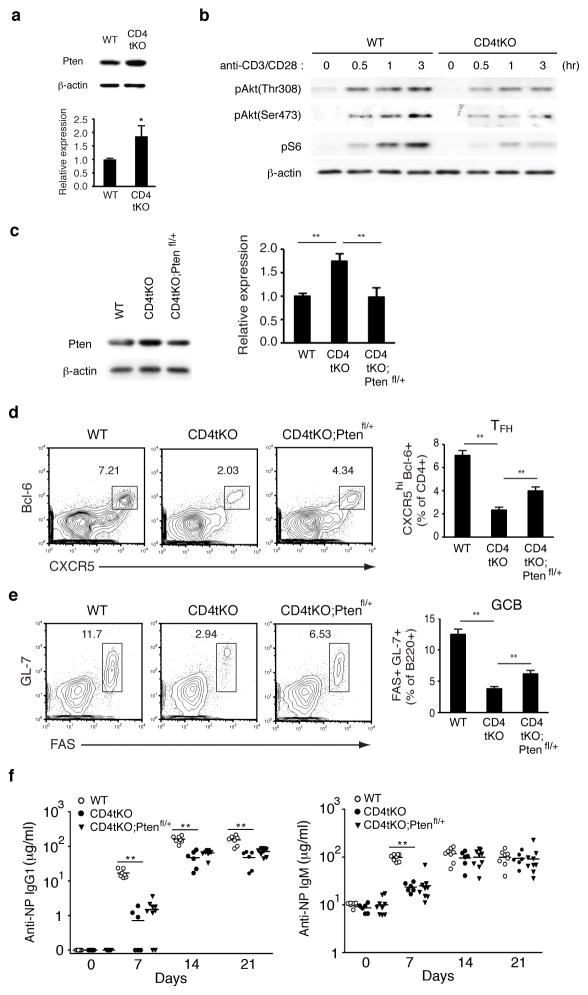

Phosphatase PTEN partially contributes to miR-17~92 function

A previous study has shown that ICOS directly controls CD4+ T cell migration from the T-B border into B cell follicles30. The PI3K pathway is the only known signaling pathway downstream of ICOS that is required for TFH and germinal center development31,32. Given the fact that Pten, a direct target gene of the miR-17~92 family miRNAs24, antagonizes PI3K function, we first tested whether these miRNAs could promote CD4+ T cell migration into B cell follicles through augmenting ICOS-PI3K signaling via Pten suppression. Indeed, Pten protein was increased in naive CD4tKO CD4+ T cells, and PI3K downstream signaling was severely impaired upon anti-CD3+CD28 stimulation in vitro (Fig. 6a, b). To determine the contribution of increased Pten protein on the TFH defect in CD4tKO mice, we generated CD4Cre;miR-17~92fl/fl;miR-106a~363−/−;miR-106b~25−/−; Ptenfl/+ mice (termed CD4tKO;Ptenfl/+ mice). However, restoration of Pten protein by deleting one copy of the Pten gene in CD4tKO CD4+ T cells only partially (~25%) rescued the TFH differentiation defect in CD4tKO mice (Fig. 6c–e). In addition, the rescue of antibody response was marginal (Fig. 6f). We also generated and analyzed CD4Cre;Ptenfl/+ mice to assess the contribution of Pten to the phenotypes of TG mice. While young CD4Cre;Ptenfl/+ mice did not exhibit any significant alterations in the number and percentage of effector/memory T cells (data not shown), 9 month old CD4Cre;Ptenfl/+ mice showed increased numbers of CD4+ T cells and CD44+ effector/memory T cells (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b), accompanied by spontaneous development of TFH and GCB cells that is reminiscent of young TG mice (Supplementary Fig. 6c, d). These results suggest that Pten is indeed an important contributor to miR-17~92 family miRNA-mediated regulation of TFH differentiation, but additional, and possibly more important, target genes must also be involved in this process.

Figure 6.

Deletion of one copy of the Pten gene in CD4tKO mice partially restores TFH differentiation. (a) The expression of Pten in WT or CD4tKO naive CD4+ T cells was examined by immunoblot (upper panel). The lower panel summarizes Pten/β-actin ratios (n=4 per group). (b) WT or CD4tKO naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated wtih anti-CD3+CD28 for indicated amounts of time and the PI3K pathway was analyzed by immunoblot (representative of three independent experiments). (c) The expression of Pten in WT, CD4tKO, or CD4tKO;Ptenfl/+ naive CD4+ T cells was examined by Western blot (left panel). The right panel summarizes Pten/β-actin ratios (n=4 per group). (d–e) Flow cytometry analysis of CXCR5hi Bcl-6+ TFH (d) and FAS+GL-7+ GCB cells (e) in mice of indicated genotypes at day 7 after i.p. immunization with OVA+Alum+LPS (n=9~12 per group). (f) NP-specific IgG1 and IgM antibody concentration was determined by ELISA on days 7, 14 and 21 after i.p immunization with 10 μg NP-CGG+Alum (n=7~8 per group). All graphs are shown as means± s.e.m. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

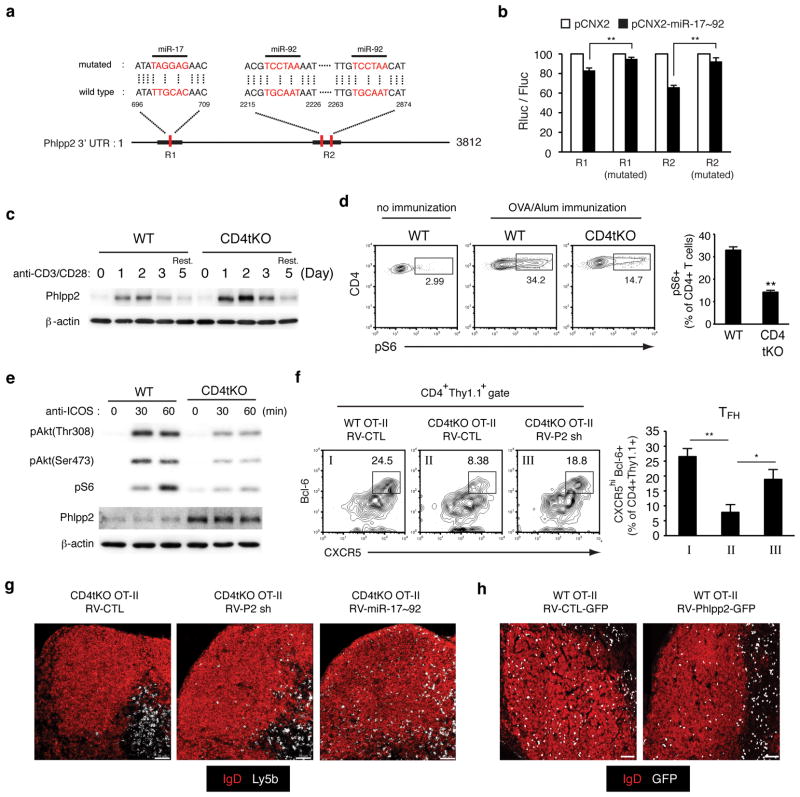

Phlpp2 mediates miR-17~92 control of TFH differentiation

It is thought that miRNAs target multiple components of functionally related pathways to achieve significant impact on the biological processes they regulate5. We examined additional components of the PI3K signaling pathway to identify potential miR-17~92 family miRNA target genes. The phosphatase Phlpp2 inactivates the PI3K downstream effector Akt, and is a miR-17~92 target in human mantle cell lymphoma cell lines33. The murine Phlpp2 gene contains one miR-17 and two miR-92 binding sites in its 3′ UTR and those sites were responsive to miR-17~92-mediated suppression in reporter assays (Fig. 7a, b). Phlpp2 protein was low in naive CD4+ T cells, strongly induced upon T cell activation, peaked around day 2, and was reduced afterwards (Fig. 7c). Consistent with its role as a miR-17~92 family miRNA target gene, activation-induced Phlpp2 protein levels were clearly increased in CD4tKO CD4+ T cells (Fig. 7c). We hypothesized that exaggerated activation-induced Phlpp2 protein expression beyond day 2 impaired ICOS-PI3K signaling and compromised T cell migration into B cell follicles. Indeed, adoptively transferred CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ T cells exhibited much reduced PI3K pathway activity as measured by phospho-S6 (pS6) on day 3.5 after immunization (Fig. 7d), around the time when T cells began to migrate into B cell follicles. Examination of ICOS-PI3K signaling in vitro showed that it was compromised in activated CD4tKO CD4+ T cells and this was not due to reduced ICOS expression (Fig. 7e and Supplementary Fig 7a, b). As Phlpp2 knockout mice have not been reported, we used retrovirus-encoded shRNAs to knock down the Phlpp2 protein in CD4tKO CD4+ T cells to that found in WT CD4+ T cells. This restored ICOS-PI3K signaling in previously activated CD4tKO CD4+ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 7c, d). We then adoptively transferred control or Phlpp2 shRNA-encoding retrovirus infected CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ T cells into WT recipients, and analyzed their differentiation into TFH cells upon protein antigen immunization. Phlpp2 knockdown in CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ T cells substantially restored their ability to differentiate into TFH cells in vivo and partially restored their migration into B cell follicles (Fig. 7f, g). Conversely, Phlpp2 overexpression in WT CD4+ T cells impaired ICOS-PI3K signaling and their ability to migrate into B cell follicles, but did not significantly change their differentiation into CXCR5hiBcl-6+ cells (Fig. 7h and Supplementary Fig. 8). These results are consistent with the recent finding that ICOS signaling controls follicular recruitment of CD4+ T cells independent of CXCR5 and Bcl-6 expression 30. Taken together, our data demonstrate that Phlpp2 is an important regulator of CD4+ T cell migration into B cell follicles, and that miR-17~92 family miRNAs control TFH differentiation in part by limiting T cell activation-induced Phlpp2 protein concentration to a proper range that allows productive ICOS-PI3K signaling to drive T cell migration into B cell follicles (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Figure 7.

MiR-17~92 family miRNAs regulate TFH differentiation through the ICOS-PI3K pathway by suppressing the expression of Phlpp2. (a) Predicted miR-17~92 binding sites in the Phlpp2 3′UTR. (b) Luciferase reporter assay was performed with WT or mutated R1 and R2 regions and normalized with firefly luciferase activity (Rluc/Fluc). (c) naive CD4+ T cells were activated with anti-CD3+CD28 and Phlpp2 protein was examined by immunoblot. Rest., CD4+ T cells were rested for 2 days in the presence of IL-2 after anti-CD3+CD28 stimulation for 3 days. (d) Ly5b+ WT or CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ T cells were transferred into B6.Ly5a mice. At day 3.5 after OVA+Alum immunization, OT-II CD4+ T cells were examined ex vivo by intracellular staining of pS6 (n=3~6 mice per group). (e) ICOS-induced pAkt and pS6, and Phlpp2 were examined in pre-activated WT or CD4tKO CD4+ T cells by immunoblot. (f) Control (RV-CTL) or Phlpp2 shRNA encoding (RV-P2sh) retrovirus transduced WT or CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into WT recipient mice, followed by OVA+Alum immunization. CXCR5hiBcl-6+ TFH cells were analyzed at day 6~6.5 post immunization (n=5~6 per group). (g–h) RV-CTL, RV-P2sh, or RV-miR-17~92 transduced Ly5b+ CD4tKO OT-II cells (3x106) (g), or RV-CTL, RV-phlpp2 transduced Ly5b+ WT OT-II cells (2x105) (h) were transferred into Ly5a mice. On day 4 after OVA+Alum immunization, draining lymph nodes were analyzed by immunohistochemistry. Images are representatives of two independent experiments (3~4 mice per group for each experiment). Scale bar, 70 μm (g–h). All graphs are shown as means± s.e.m. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Based on the results presented in this study, we propose the following model of miR-17~92 family-mediated regulation of TFH differentiation. The expression of both miR-17~92 family miRNAs and their target gene Phlpp2 are low in naive CD4+ T cells. They are induced upon T cell activation, peak around day 2, and are downregulated afterwards. Downregulation of Phlpp2 after day 2 is critical for ICOS-PI3K signaling, which drives T cell migration into B cell follicles30, a defining feature of the TFH differentiation program. The upregulation of miR-17~92 family miRNAs serves to limit the activation-induced Phlpp2 protein to a proper range, as exaggerated and prolonged Phlpp2 protein expression would impair ICOS-PI3K signaling. Indeed, complete deletion of the miR-17~92 family miRNAs in T cells results in dysregulated Phlpp2 protein expression, compromised ICOS-PI3K signaling, reduced migration into B cell follicles, and impaired TFH differentiation. As T cell migration into B cell follicles is not required for the differentiation of other CD4+ effector T cell subsets, this model explains why TFH differentiation is severely compromised in OX40tKO mice during LCMV Armstrong infection, whereas TH1 differentiation remains relatively normal in those animals.

The complete block of CD4tKO CD4+ T cell migration into B cell follicles is almost identical to that caused by ICOS deficiency30. However, CD4tKO CD4+ T cells can still differentiate into CXCR5hiBcl-6+ cells, though at a much reduced efficiency. This is in sharp contrast to ICOS-deficient CD4+ T cells, whose differentiation into CXCR5hiBcl-6+ cells is completely abolished34. The differential regulation of follicular recruitment and differentiation into CXCR5hiBcl-6+ cells by miR-17~92 family miRNAs and ICOS suggests that these two facets of the TFH differentiation program are controlled by distinct, and yet partially overlapping, molecular pathways. This idea is further supported by the consequences of Phlpp2 overexpression in WT CD4+ T cells, which severely impaired their follicular recruitment but not differentiation into CXCR5hiBcl-6+ cells. Elucidation of molecular pathways underlying these two facets holds the key to understanding the TFH differentiation program.

It is important to emphasize that Phlpp2 is not the only functionally important target through which miR-17~92 family miRNAs regulate TFH differentiation, as Phlpp2 knockdown only partially restored follicular recruitment and TFH differentiation of CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ T cells. Pten is clearly another important mediator of miR-17~92 family function, as deleting one copy of the Pten gene partially restored TFH and GCB differentiation in CD4tKO mice. Other functionally important targets may exist and mediate miR-17~92 family control of various aspects of the TFH differentiation program. Future investigation is warranted to identify additional targets and evaluate their contribution to the functions of the miR-17~92 family.

Previous studies showed that miR-17~92 regulates CD4+ T cell activation and proliferation in vitro24,35. By examining CD4tKO OT-II CD4+ T cells during immune responses against a protein antigen, we showed in this study that the deficiency of miR-17~92 family miRNAs had negligible effect on CD4+ T cell proliferation and caused a modest delay in their activation in vivo. The delayed activation is not the direct cause of TFH differentiation defect in CD4tKO mice, as deleting miR-17~92 family miRNAs beyond the initial activation phase by OX40Cre caused a similar TFH differentiation defect. Therefore, the miR-17~92 family miRNAs play a general role in the activation of CD4+ T cells and a specific role in their differentiation into TFH cells.

In summary, our loss- and gain-of function studies demonstrate that miR-17~92 family miRNAs are critical regulators of TFH differentiation and that Phlpp2, the recently discovered Akt phosphatase, is an important mediator of the functions of these miRNAs. Given the crucial roles of TFH cells in germinal center reaction and antibody responses, manipulating miR-17~92 family miRNAs or their target genes and pathways in vivo may facilitate the design of better vaccines and the development of therapeutic regimens treating autoimmune diseases.

ONLINE METHODS

Mice

The generation of miR-17~92fl/fl (Jax stock 008458), miR-106a~363−/− (Jax stock 008461), miR-106b~25−/− (Jax stock 008460), miR-17~92 Tg (Jax stock 008517), CD4-Cre (Jax stock 017336), OT-II (Jax stock 004194), and Ptenfl/fl (Jax stock 006440) mice was previously described7,12,24,28,36. All mice were bred and housed under SPF conditions. Disease development was monitored by frequent visual examination and histopathological analyses. All mice were used in accordance with guidelines from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The Scripps Research Institute.

Mixed bone marrow chimera

Ly5a B6 or Rag1−/− mice were irradiated with two rounds of 600 cGy with a 3 h interval. Bone marrow cells from WT B6 (Ly5a or Ly5a/b) and tKO or TG (Ly5b) mice were subjected to red blood cell lysis and T cell depletion by magnetic separation. 1:1 mixed 5x106 bone marrow cells were transferred via tail vein injection. Eight weeks later, the mice were immunized with NP-OVA+Alum+LPS intraperitoneally. Spontaneous generation of TFH cells in WT:TG chimeras was analyzed at 3 months after reconstitution.

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-CD4 (GK1.5), CD25 (PC61), CD44 (IM7), CD69 (H1.2F3), CD45.1 (A20), CD45.2 (104), CD40L (MR1), PD-1 (RMP1-30), ICOS (15F9), ICOS (C398.4A, agonist for TFH cell differentiation) and biotin anti-rat IgG2a (MRG2a-83) were purchased from Biolegend. Anti-CXCR5 (2G8), PE-conjugated CXCR5 (2G8), -Bcl-6 (K112-91), -CD95 (Jo2), IgD(11-26c.2a), APC-conjugated CD3 (2C11) and Alexa Fluor® 647-conjugated GL-7 (GL7) were from BD Pharmingen. Recombinant human IL-2, mouse IL-6, and mouse IL-21 were purchased from Peprotec. Anti-Pten (138G6), phospho-Akt (Ser473; D9E), phospho-Akt (Thr308; 244F9) and phospho-S6 (2F9) were from Cell Signaling. Goat anti-hamster IgG antibody was purchased from Pierce. Anti-Phlpp2 antibody (A300-661A) was purchased from Bethyl Laboratories.

Cell isolation and in vitro activation

Total CD4+ T cells were isolated from pooled single cell suspensions of spleen and lymph nodes by using mouse CD4+ T cell isolation kit II (Miltenyi Biotech). Naive CD4+ T cells (CD4+CD25−CD44−CD69−) were purified from isolated CD4+ T cells by MACS depletion of CD25+, CD44+, and CD69+ cells (>97% purity). For Northern blot, naive CD4+ T cells were activated with plate coated anti-CD3 (5 μg/ml) in the presence of anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml) for indicated amounts of time. For TFH isolation, WT B6 mice were immunized with OVA/Alum/LPS and CD4+ T cells were isolated from spleen at day 7 after immunization. Isolated CD4+ T cells were stained and FACS-sorted for naive CD4+ T cells (CD4+CD62L+CXCR5−PD1−CD44−), pre-TFH (CD4+CXCR5hiPD1low), and TFH (CD4+CXCR5hiPD1hi).

Immunization

Antigens for immunization were prepared by mixing NP18-OVA (Biosearch Technologies), OVA (albumin from chicken egg white, grade II, Sigma), or NP36-CGG (Biosearch Technologies) dissolved in PBS and 10% KAl(SO4)2 at 1:1 ratio, in the presence or absence of LPS (Escherichia coli 055:B5,Sigma), and adjusting pH to 7 to form precipitate. 100 μg NP-OVA and 10 μg LPS precipitated in alum was injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) for flow cytometry analysis of TFH and GCB formation. 5 μg NP-CGG precipitated in alum was injected i.p. for NP-specific antibody responses. 25 μg OVA precipitated in alum was injected subcutaneously (s.c.) at flank areas for OT-II CD4+ T cell adoptive transfer experiments.

LCMV infection

The clone-13 strain of LCMV was propagated on BHK cells and supernatants were clarified by load speed centrifugation, directly titered, and used for infection. For determination and quantification of viremia, blood was drawn from the retro-orbital sinus under isoflurane anesthesia. Serum was isolated by centrifugation to remove red and white blood cells. 10 μl serum was used to perform 10-fold serial dilutions for plaque assays on VERO cells37. Lung, liver, spleen and kidney were harvested from euthanized mice and frozen at −80 °C. At the time of assay, tissues were thawed, weighed and homogenized in 1 ml media, clarified by centrifugation and 10 μL of the supernatant was used to perform 10-fold serial dilutions for plaque assays. For LCMV Armstrong, mice were infected with the LCMV Armstrong 53b strain at a dose of 2 x 106 PFU intravenously.

Flow cytometry analysis

Single cell suspensions were prepared from spleen or draining lymph nodes. Antibodies for cell surface markers were added and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C. For most CXCR5 staining, single cells were stained with purified anti-mouse CXCR5, followed by anti-rat IgG2a and Streptavidin-PE. PE conjugated anti-mouse CXCR5 antibody was used for staining in vitro differentiated TFH cells. For CD40L staining, cells were stained for cell surface markers, fixed with 1% PFA for 1 h at 4 °C, permeabilized with FACS buffer containing 0.1% saponin (Sigma), and incubated with PE-conjugated anti-CD40L for 30 min at 4 °C. Foxp3 staining kit (eBioscience) was used to stain Bcl-6 following manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, surface marker stained cells were fixed with Fixation/Permeabilization buffer for 1 h at 4 °C, washed with 1x Permeabilization buffer, and incubated with anti-Bcl-6 at room temperature for 1 h in 1x Permeabilization buffer. Bcl-6 staining of in vitro differentiated TFH cells was performed with FACS-sorted GFP+ cells. All flow cytometry data was acquired on LSRII flow cytometers (Becton Dickinson) and analyzed using the FlowJo software (Treestar, Inc.).

Adoptive transfer

Naive WT or tKO OT-II cells (1x106) were adoptive transfer experiments into B6.Ly5a mice via tail vein injection and immunized one day after transfer. CD4tKO OT-II cells with Phlpp2 knockdown (3x106) or WT OT-II cells with Phlpp2 overexpression (2X105) were transferred into B6.Ly5a mice, which were immunized with 25 μg Ova/Alum s.c. one day after transfer.

Immunostaining

Freshly dissected tissues were instantly frozen in OCT. Sections of 8~15 μm were cut with a Leica Cryostat, mounted on Superfrost Plus glass slides, fixed in cold acetone for 10 minutes, air dried, and stained for IgD to label the follicular mantle, CD3 to identify T cells, Bcl-6 to identify the germinal center area, or Ly5b to detect adoptively transferred OT-II CD4+ T cells. For some experiments, GFP expressed by the retroviral vector was used to identify infected cells. Images were acquired with an Olympus FV1000 microscopy and processed with Bitplane Imaris. Tiling of images to cover large tissue areas was done using Adobe Photoshop.

Intracellular cytokine staining

Splenocytes were stimulated for 5 h with 2 μg/ml MHC class I restricted LCMV-GP33–41 or LCMV-GP276–286 peptides (>99% pure; American Peptide and The Scripps Research Institute, Center for Protein Science, La Jolla, CA) in the presence of 4 μg/ml brefeldin A (Sigma). Cells were fixed, permeabilized with 2% saponin, and stained intracellularly with antibodies to IFN-γ (XMG1.2), TNF (MP6-XT22) and IL-2 APC (JES6-5H4). Tetramer positive cells were detected by staining with SA-APC conjugated GP33 (GP33–41) or GP276 (GP276–286) tetramers for 1 h at 4 °C. Absolute cell numbers were determined by multiplying the frequency of specific cell populations by the total number of viable cells. For Fig. 2e, Fig. 3g, and supplementary Fig 4c–d, cells were stimulated for 4h with PMA (50ng/ml, Sigma) and ionomycin (1μg/ml, Sigma) in the presence of monensin (Biolegend). The cells were fixed and permeabilized as described above and stained with antibodies for IFN-γ (XMG1.2) (TH1), IL-4 (11B11) (TH2) or IL-17A (TC11-18H10.1) (TH17). For IL-21 intracellular staining, recombinant mIL-21R-Fc chimera protein (R&D Systems) and PE-conjugated goat anti–human Fcγ antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) were used as previously described38.

In vitro TFH cell differentiation

To obtain recombinant virus, 10 μg RV-miR-17~92 or control RV-GFP vector was transfected into phoenix-eco cells, a retroviral packaging cell line derived from 293T cells. The supernatants were collected 48 h after transfection and filtered through a 0.45 μm membrane. Naive CD4+ T cells were activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 for 24 h, infected with retroviral supernatants in the presence of polybrene (6 μg/ml) by spinoculation and further activated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28, in the presence of anti-TGFβ (antagonist; 5μg/ml), anti-ICOS (agonist; 5μg/ml), recombinant human IL-2 (rhIL-2; 100 U/ml), recombinant mouse IL-6 (rmIL-6; 10ng/ml), and recombinant mouse IL-21 (rmIL-21; 10ng/ml) for 3–5 days39.

ELISA

Microtiter plates were coated with salmon sperm DNA (5 μg/ml, Invitrogen) in Reacti-Bind DNA Coating Solution (Thermo Scientific) for measuring anti-dsDNA autoantibody, with NP-BSA (10 μg/ml, Biosearch Technologies) in PBS for measuring NP-specific antibody, LCMV clone-13 virus particles for measuring anti-LCMV antibody. The plates were blocked with PBSA (0.5% BSA in PBS). Serum samples were serially diluted in PBSA and incubated in blocked plates overnight at 4°C. The plates were incubated with Biotin-conjugated anti-IgM, IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, or pan-IgG (Southern Biotech) for 2 hours, streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase (Roche) for 1 hour, alkaline phosphatase substrate solution containing 4-nitro-phenyl phosphate (Sigma) for color development, and measured on a VERSAmax microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

Northern blot

Total RNA was extracted from CD4+ T cells isolated from WT, tKO, and TG mice at greater than 95% purity using TRIzol® Reagent (Life Technologies) following manufacturer’s instructions. 8 μg total RNA was used to detect miRNAs. DNA oligonucleotides antisense to mature miRNAs were used as probes. U6 snRNA was used as internal control for normalization. Northern blot results were acquired on a STORM 860 phosphorimager and analyzed using the ImageQuant software.

Luciferase reporter assay

WT or mutated Phlpp2 3′UTR R1 and R2 regions containing miR-17 or miR-92 binding sites were cloned into the psiCHECK-2 dual reporter assay vector. Renilla luciferase activity was measured in HeLa cells in the presence or absence of miR-17~92 overexpression and normalized with firefly luciferase activity (Rluc/Fluc). The Rluc/Fluc ratios were arbitrarily set at 100 for HeLa cells without miR-17~92 overexpression. Primers for cloning R1 and R2 regions are:

R1for: 5′-TATTACTCGAGCTGACATGGTGACATGGTTC-3′;

R1rev: 5′-TATTAGCGGCCGCGCAGTGATAGAGCATCCTCC-3′;

R2for: 5′-TATTACTCGAGCTGAAGAAAGAGCACTCGGC-3′;

R2rev: 5′-TATTAGCGGCCGCTGCAACATGCTCTGGCTC-3′

Retroviral infection

Annealed Phlpp2 shRNA oligonucleotides (5′-GATCGCAATGACTTGACAGAAA TCCTCTAAAGGAGGATTTCTGTCAAGTCATTGC-3′) or PHLPP2 were inserted into Thy1.1-expressing RV vector. S-Eco packaging cells were transfected by using Fu-GENE HD (Promega) and retroviral supernatants were collected 48 hours after transfection. Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with 5 μg/ml anti-CD3 and 2 μg/ml anti-CD28 for 1 day and then transduced with retroviral supernatants in the presence of 6 μg/ml polybrene (SIGMA) by spin infection for 1 h at 1800 rpm.

ICOS stimulation

Naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with 5 μg/ml anti-CD3 and 2 μg/ml anti-CD28 for 3 days and rested for 3 h. One million cells were stimulated with soluble anti-ICOS (5 μg/ml) and goat anti-hamster antibodies (10 μg/ml) in 100 μl medium for indicated amounts of time.

Immunoblotting

Freshly isolated or stimulated naive CD4+ T cells were washed with PBS twice and lysed in cell lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA) supplemented with Halt Protease & Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific). Primary antibodies were diluted in 5% w/v BSA in 1X TBS buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH8.0, 150 mM NaCl) and incubation was done at 4°C overnight.

Histological analysis

Tissues from sick TG and age matched control mice were fixed in 4% formalin solution. Hematoxylin-eosin stained slides were prepared by the TSRI Histology Core following standard procedures.

Statistical analysis

A total of 4~10 mice per group were used in each animal experiments. This number routinely provides the statistical power to define meaningful differences between groups when they exist. When differences between groups approach statistical significance (p=0.1~0.05), we used more mice for a more rigorous test of statistical significance. Student unpaired t test was used for statistical analysis. P values <0.05 was considered significant and all graphs were presented means± s.e.m.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Y. Zheng (Salk Institute), C. Fine and B. Rezner (The Scripps Research Institute flow cytometry core facility) for technical assistance; I. Tobias and A. Newton (UCSD) for providing the pcDNA3-HA-PHLPP2 plasmid; C.H. Kim (Purdue University), E. Stone, S.M. Hedrick (UCSD), K. Sauer (The Scripps Research Institute), the members of Xiao lab for discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. C.X. is a Pew Scholar in Biomedical Sciences. This study is supported by the PEW Charitable Trusts, Cancer Research Institute, Lupus Research Institute, American Heart Association (11POST7430106 to J.R.T.), National Institute of Health (R01AI019484 to M.B.A.O and R01AI087634 to C.X.), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC grant 81161120405 to H.Q.).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.X., S.G.K., W.H.L., and J.R.T. conceived and designed the project. P.L. performed immunostaining and some Phlpp2-related experiments under the supervision of H.Q. H.W.L. performed in vitro TFH differentiation experiments under the supervision of E.V. S.G.K., W.H.L., J.R.T., H.Y.J., J.S., and D.F. performed all other experiments under the supervision of C.X., J.R.T., and M.B.A.O. S.G.K., W.H.L., J.R.T. and C.X. wrote the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bushati N, Cohen SM. microRNA functions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:175–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Connell RM, Rao DS, Chaudhuri AA, Baltimore D. Physiological and pathological roles for microRNAs in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:111–122. doi: 10.1038/nri2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiao C, Rajewsky K. MicroRNA control in the immune system: basic principles. Cell. 2009;136:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendell JT. miRiad roles for the miR-17-92 cluster in development and disease. Cell. 2008;133:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ventura A, et al. Targeted deletion reveals essential and overlapping functions of the miR-17 through 92 family of miRNA clusters. Cell. 2008;132:875–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crotty S. Follicular Helper CD4 T Cells (TFH) Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:621–663. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnston RJ, et al. Bcl6 and Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular helper cell differentiation. Science. 2009;325:1006–1010. doi: 10.1126/science.1175870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nurieva RI, et al. Bcl6 mediates the development of T follicular helper cells. Science. 2009;325:1001–1005. doi: 10.1126/science.1176676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu D, et al. The transcriptional repressor Bcl-6 directs T follicular helper cell lineage commitment. Immunity. 2009;31:457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee PP, et al. A critical role for Dnmt1 and DNA methylation in T cell development, function, and survival. Immunity. 2001;15:763–774. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fahey LM, et al. Viral persistence redirects CD4 T cell differentiation toward T follicular helper cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208:987–999. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harker JA, Lewis GM, Mack L, Zuniga EI. Late interleukin-6 escalates T follicular helper cell responses and controls a chronic viral infection. Science. 2011;334:825–829. doi: 10.1126/science.1208421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed R, Oldstone MB. Organ-specific selection of viral variants during chronic infection. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1719–1724. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.5.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elsaesser H, Sauer K, Brooks DG. IL-21 is required to control chronic viral infection. Science. 2009;324:1569–1572. doi: 10.1126/science.1174182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frohlich A, et al. IL-21R on T cells is critical for sustained functionality and control of chronic viral infection. Science. 2009;324:1576–1580. doi: 10.1126/science.1172815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Linterman MA, et al. IL-21 acts directly on B cells to regulate Bcl-6 expression and germinal center responses. J Exp Med. 2010;207:353–363. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nurieva RI, et al. Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity. 2008;29:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogelzang A, et al. A fundamental role for interleukin-21 in the generation of T follicular helper cells. Immunity. 2008;29:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yi JS, Du M, Zajac AJ. A vital role for interleukin-21 in the control of a chronic viral infection. Science. 2009;324:1572–1576. doi: 10.1126/science.1175194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zotos D, et al. IL-21 regulates germinal center B cell differentiation and proliferation through a B cell-intrinsic mechanism. J Exp Med. 2010;207:365–378. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barber DL, et al. Restoring function in exhausted CD8 T cells during chronic viral infection. Nature. 2006;439:682–687. doi: 10.1038/nature04444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao C, et al. Lymphoproliferative disease and autoimmunity in mice with increased miR-17-92 expression in lymphocytes. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:405–414. doi: 10.1038/ni1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linterman MA, et al. Follicular helper T cells are required for systemic autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2009;206:561–576. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpson N, et al. Expansion of circulating T cells resembling follicular helper T cells is a fixed phenotype that identifies a subset of severe systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:234–244. doi: 10.1002/art.25032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vinuesa CG, et al. A RING-type ubiquitin ligase family member required to repress follicular helper T cells and autoimmunity. Nature. 2005;435:452–458. doi: 10.1038/nature03555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barnden MJ, Allison J, Heath WR, Carbone FR. Defective TCR expression in transgenic mice constructed using cDNA-based alpha- and beta-chain genes under the control of heterologous regulatory elements. Immunol Cell Biol. 1998;76:34–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1998.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baumjohann D, Okada T, Ansel KM. Cutting Edge: Distinct waves of BCL6 expression during T follicular helper cell development. J Immunol. 2011;187:2089–2092. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu H, et al. Follicular T-helper cell recruitment governed by bystander B cells and ICOS-driven motility. Nature. 2013;496:523–527. doi: 10.1038/nature12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gigoux M, et al. Inducible costimulator promotes helper T-cell differentiation through phosphoinositide 3-kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20371–20376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911573106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rolf J, et al. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase activity in T cells regulates the magnitude of the germinal center reaction. J Immunol. 2010;185:4042–4052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jiang P, Rao EY, Meng N, Zhao Y, Wang JJ. MicroRNA-17-92 significantly enhances radioresistance in human mantle cell lymphoma cells. Radiat Oncol. 2010;5:100. doi: 10.1186/1748-717X-5-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi YS, et al. ICOS receptor instructs T follicular helper cell versus effector cell differentiation via induction of the transcriptional repressor Bcl6. Immunity. 2011;34:932–946. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jiang S, et al. Molecular dissection of the miR-17-92 cluster’s critical dual roles in promoting Th1 responses and preventing inducible Treg differentiation. Blood. 2011;118:5487–5497. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-05-355644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lesche R, et al. Cre/loxP-mediated inactivation of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene. Genesis. 2002;32:148–149. doi: 10.1002/gene.10036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmed R, Salmi A, Butler LD, Chiller JM, Oldstone MB. Selection of genetic variants of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus in spleens of persistently infected mice. Role in suppression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte response and viral persistence. J Exp Med. 1984;160:521–540. doi: 10.1084/jem.160.2.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Suto A, et al. Development and characterization of IL-21-producing CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1369–1379. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu KT, et al. Functional and epigenetic studies reveal multistep differentiation and plasticity of in vitro-generated and in vivo-derived follicular T helper cells. Immunity. 2011;35:622–632. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.