Abstract

Trypanosoma brucei membranes consist of all major eukaryotic glycerophospholipid and sphingolipid classes. These are de novo synthesized from precursors obtained either from the host or from catabolised endocytosed lipids. In recent years, substantial progress has been made in the molecular and biochemical characterisation of several of these lipid biosynthetic pathways, using gene knockout or RNA interference strategies or by enzymatic characterization of individual reactions. Together with the completed genome, these studies have highlighted several possible differences between mammalian and trypanosome lipid biosynthesis that could be exploited for the development of drugs against the diseases caused by these parasites.

Keywords: Trypanosoma, Phospholipids, Sphingolipids, Fatty acids, Biosynthesis, Metabolism, Gene IDs

1. Introduction

Parasitic protozoa cause infectious diseases affecting 15% of the global population, with millions of fatalities. One such neglected disease is caused by the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma brucei, which causes Human African Trypanosomiasis, also known as African sleeping sickness. According to the World Health Organization, it constitutes a serious health risk to ~60 million people in Sub-Saharan Africa. Due to increased efforts in vector control, the annual rate of infections has fallen to ~50,000 with an estimated ~7000 fatalities per year. In addition, the animal form of the disease, called Nagana, has a devastating economic, social and nutritional impact by affecting the cattle population in Africa. Current human and animal drug therapies are woefully inadequate, expensive, hard to administer, highly toxic and have increasing drug-resistance problems. Hence there is an urgent need for new drugs to treat African sleeping sickness and Nagana, as well as other Third World diseases transmitted by closely related protozoan parasites, such as Leishmania spp. and Trypanosoma cruzi.

T. brucei belong to the order Kinetoplastida and are considered part of the earliest diverging eukaryotic lineages [1]. As such, they are regarded as a ‘model organism’ for the study of alternative mechanisms by which eukaryotes accomplish basic functions. During their life cycle, trypanosomes encounter the vastly different environments of the mammalian bloodstream and various tissues within the tsetse vector. They respond to these by dramatic morphological and metabolic changes, including adaptation of their lipid and energy metabolism [2]. Lipids constitute 11–18% of the dry weight of T. brucei and their distribution is consistent with the usual range of lipids found in eukaryotes, such as phospholipids, neutral lipids, fatty acids, isoprenoids, and sterols [3–9]. T. brucei bloodstream and procyclic forms contain all major phospholipid classes known in other eukaryotes, accounting for ~80% of membrane lipids [7]. Trypanosomes do not utilise intact phospholipids scavenged from their hosts, but use their repertoire of metabolic and anabolic enzymes to de novo synthesise their own phospholipids and glycolipids for their specific requirements [5,10]. Until recently, most of the literature on T. brucei lipid metabolism focused on myristate formation and turnover, due to its requirement for glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor biosynthesis and remodeling [11–14].

Completion of the Tri-Tryp (T. brucei, T. cruzi, Leishmania spp.) genome projects (http://tritrypdb.org/tritrypdb/) has allowed putative identification of homologues of genes necessary for de novo biosynthesis of all classes of phospholipids. Recently, several biosynthetic enzymes involved in de novo synthesis of phospholipids have been characterized experimentally, including enzymes involved in de novo synthesis of fatty acids and the major glycerophospholipid and sphingolipid classes, and several catabolic enzymes, including two phospholipases and a sphingomyelinase (see below). As more enzymes involved in phospholipid metabolism are characterized, our understanding of these parasites will allow direct comparisons with man, and thus new targets are likely to emerge for the development of new anti-protozoan drugs.

2. Lipid composition of African trypanosomes

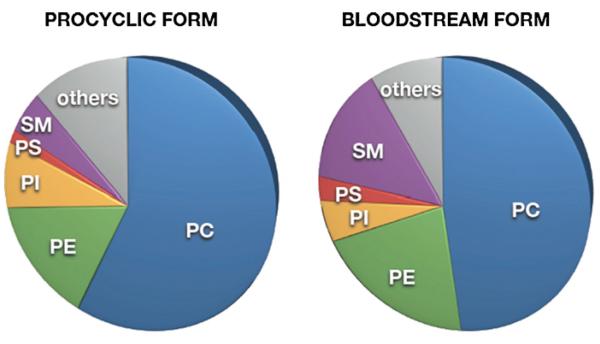

The total phospholipid composition of T. brucei bloodstream and procyclic forms resembles that of other eukaryotic cells. Phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) represent the most abundant glycerophospholipid classes, comprising 45–60% and 10–20%, respectively, of total phospholipids (Fig. 1). Phosphatidylinositol (PI), phosphatidylserine (PS) and cardiolipin (CL) represent minor glycerophospholipid classes and account for 6–12%, <4% and <3%, respectively, of total lipid phosphorus [6,7,9,15–17]. In addition, T. brucei parasites contain substantial amounts (10–15% of total lipid phosphorus) of the sphingophospholipids, sphingomyelin (SM), inositol phosphorylceramide (IPC) and ethanolamine phosphorylceramide (EPC) [6,7,18,19]. Interestingly, trypanosomes from both life cycle stages contain high amounts of ether lipids, which are particularly abundant in PE and PS [7]. A similar observation has also been made in the related kinetoplastids, Leishmania spp. ([20–22]; reviewed in [23]), T. cruzi [24], and T. congolense (P. Bütikofer, E. Greganova, M. Serricchio and A. Acosta-Serrano, unpublished data). Information on the lipid composition of subcellular fractions of T. brucei parasites is lacking, except for a recent analysis of the lipid composition of isolated mitochondria from T. brucei procyclic forms [25]. A detailed comparative lipidomics analysis of bloodstream and procyclic form T. brucei has recently been published [26].

Fig. 1.

Phospholipid composition in T. brucei. Relative distribution of the phospholipid classes, PC, PE, PI, PS, and SM, in T. brucei procyclic and bloodstream forms. Others include IPC, EPC, CL, PG, PIPs, phosphatidic acid, lyso-phospholipids, phosphorylated prenyls, Dol-Ps.

The fatty acyl chain composition of T. brucei membrane lipid classes differs between bloodstream and procyclic forms [6,7], possibly reflecting an adaptation of the parasite membrane to the change in environmental conditions in the insect host compared to the mammalian bloodstream [10]. The molecular species composition of PC in bloodstream form parasites was shown to consist of 18:0/18:2 (23%), 16:0/22:6 (12%), 18:0/22:6 (11%), 16:0/18:2 (9%), 18:0/22:4 (7%), 18:2/20:4 and 18:1/20:5 (6%), 18:2/22:5 (5%), 18:0/20:4 (5%), and others (5%) (with the assumption that saturated fatty acids are sn-1 esterified) [7,26]. Similar chain lengths and degrees of saturation were also found for the molecular species of PE and PI in bloodstream forms, although the distribution slightly varied. In T. brucei procyclic forms, the relative amounts of diacyl glycerophospholipids containing highly unsaturated fatty acyl chains showed a decrease compared to bloodstream forms, in the order of PC > PE > >PI. T. brucei parasites also contain significant proportions of sn-1 ether-linked glycerophospholipids, especially in PE (73–84%) and PS (60–88%)[7,15,17,26].

The fatty acyl chain composition of T. brucei does not reflect that of their immediate environment. Examination of the fatty acids of T. b. rhodesiense bloodstream forms showed that they have a much lower proportion of C16:0 and a higher proportion of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (C18:2, C20:2, C20:4, C22:4, C22:5, C22:6) than in their host plasma, probably as a result of their preferred uptake of these fatty acids from culture medium compared to saturated fatty acids [6]. More recent experiments provided clear evidence for the existence of de novo fatty acid synthesis, elongation, and desaturation in T. brucei [27,28]. Analysis of the fatty acyl composition of various phospholipids supported the notion that the intrinsic acyl-coenzyme A (acyl-CoA) specificity of the acyltransferases involved in ether- and diacyl-type glycerophospholipid formation, together with the availability of acyl-CoAs, are major factors in producing the final phospholipid molecular species composition. Interestingly, most ether-type species of PC, PE and PI, and most diacyl-type species of PC, PE, PI and PS, contain almost exclusively C18:0 attached to the sn-1 position of the glycerol [7,26]. This implies that both the dihydroxyacetonephosphate and glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferases have either a specificity for C18:0-CoA or, alternatively, are exposed exclusively to C18:0-CoA. In contrast, the sn-2 position of the glycerophospholipid subclasses is almost exclusively occupied by unsaturated acyl groups, i.e. predominately C18:2 in the ether-type and mainly C18:2 and C22:4, with some C20:4, in the diacyl-type glycerophospholipids. Presumably, most C20:4 is scavenged from the host plasma and modified to C22:4 by the elongase ELO4 [28].

Like other eukaryotic cells, trypanosome membranes contain substantial amounts of sterols. A recent detailed analysis showed that cholesterol constitutes more that 95% of total sterol in T. brucei bloodstream forms isolated from rat blood [29], most of which they take up from the mammalian host by receptor-mediated endocytosis [4,30]. In contrast, T. brucei procyclic forms contain a set of sterols, with cholesta-5,7,24-trienol, cholesterol and ergosta-5,7,25(27)-trienol representing the most abundant species, accounting for >84% of total sterol [29]. Some of the sterols in T. brucei may accumulate in lipid rafts [31], which seem enriched in the flagellar membrane [32].

3. Uptake and synthesis of lipid precursors

3.1. Uptake of components for de novo lipid biosynthesis

It has long been known that trypanosomatids scavenge lipids from their host environment. This may occur via uptake of protein-bound fatty acids and lyso-phospholipids, which are then assembled to phospholipids, or by receptor-mediated endocytosis of lipoprotein particles [5,33–36]. In addition, it has been shown that T. brucei bloodstream forms in culture require the uptake of lipids from the medium for optimal growth [34,37]. However, more recent studies have demonstrated that T. brucei bloodstream and procyclic forms are capable of de novo synthesis of all major phospholipid classes using exogenous lipid precursors [15–19,38]. In addition, T. brucei parasites possess a system for de novo synthesis of fatty acids [28].

Choline, ethanolamine and myo-inositol represent components of the head groups of the major glycerophospholipid and sphingolipid classes. Although choline uptake activities have been reported in certain protozoan parasites [39,40], T. brucei bloodstream forms show no transport activity for choline and, instead, meet their demand for choline by uptake of lyso-PC from the culture medium, or the host plasma [41,42]. In contrast, efficient uptake of ethanolamine, followed by incorporation into the cellular PE pool, has been reported in both bloodstream and procyclic form T. brucei [15–17,42]. A transporter for ethanolamine has, however, not been identified in protozoa. In contrast, several myo-inositol transporters have been reported and characterized in L. donovani [43–46]. In addition, myo-inositol uptake has also been documented in Trypanosoma cruzi [47,48] and T. brucei bloodstream forms [38].

Serine, an essential precursor for sphingolipid and PS synthesis, is readily taken up by T. brucei bloodstream and procyclic forms and incorporated into the respective lipid classes [15,17,18].

3.2. De novo fatty acid synthesis

A type II prokaryotic-like fatty acid synthesis system located inside the mitochondria was initially thought to be the source of de novo synthesised fatty acids in T. brucei [27]. However, the low level of fatty acid production by this system suggested that, in addition to fatty acid scavenging from the host, there must be another de novo synthetic route to myristate (C14:0). Subsequently, it was shown that four microsomal elongases with different specificities produced nearly all of the de novo synthesised fatty acids in T. brucei (Table 1) [28,49]. The first two elongases convert C4:0 to C10:0 and C10: to C14:0, respectively, while elongase 3 extends C14:0 to C18:0 (Fig. 2). This last enzyme is stage specifically down-regulated in bloodstream form trypanosomes, resulting in the almost exclusive production of myristate (C14:0), which is utilized for GPI anchor synthesis and remodeling [13]. Finally, elongase 4 likely elongates host-derived long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, i.e. C20:4 to C22:4 [49], which may then be desaturated further by a plant-like fatty acid desaturase to form significant amounts of C22:5 and C22:6 [50] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Trypanosoma brucei genes encoding predicted enzymes involved in membrane lipid biosynthesis.

| Biosynthetic step | Enzyme name | T. brucei gene | Essentiala | Yeast genea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ELO1 | Elongase 1 | Tb927.7.4160 | No (both) | |

| ELO2 | Elongase 2 | Tb927.7.4170 | No (BSF) | |

| ELO3 | Elongase 3 | Tb927.7.4180 | No (both) | |

| ELO4 | Elongase 4 | Tb927.5.4530 | No (BSF) | ELO1-3 |

| ACS1 | Acyl-CoA synthetase 1 | Tb09.160.2770 | ||

| ASC2 | Acyl-CoA synthetase 2 | Tb09.160.2780 | FAA2 | |

| ASC3 | Acyl-CoA synthetase 3 | Tb09.160.2810 | FAA1/FAA4 | |

| ASC4 | Acyl-CoA synthetase 4 | Tb09.160.2840 | ||

| ASC5 | Acyl-CoA synthetase 5 | Tb927.10.3260 | No (both) | FAA2 |

| ACBP | Acyl-CoA binding protein | Tb927.4.2010 Tb11.52.0001 |

BSF | ACB1 |

| SPT | Serine palmitoyltransferase | Tb927.4.1020 | LCB1/LCB2 | |

| 3KSR | 3-Ketosphinganine reductase | Tb927.10.4040 | TSC10 | |

| DHCS | Dihydroceramide synthase | Tb927.8.7730 Tb927.4.4740 |

LAG1/LAC1 | |

| DHCD | Dihydroceramide desaturase | n.i. | SUR2/SYR2 | |

| SK | Sphingosine kinase | Tb927.7.1240 | LCB4/LCB5 | |

| SPL | Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase | Tb927.6.3630 | DPL1 | |

| SLS1 | Sphingolipid synthase 1 | Tb09.211.1000 | ||

| SLS2 | Sphingolipid synthase 2 | Tb09.211.1010 | ||

| SLS3 | Sphingolipid synthase 3 | Tb09.211.1020 | ||

| SLS4 | Sphingolipid synthase 4 | Tb09.211.1030 | AUR1 | |

| GAT1 | Glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase | Tb927.10.3100 | GAT1/2 | |

| GAT2 | 1-Acyl-sn-glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase | Tb11.01.6800 | GAT1/2 | |

| DAT | Dihydroxyacetonephosphate acyltransferase | Tb927.4.3160 | SLC1 | |

| ADS | 1-Alkyl-dihydroxyacetonephosphate synthase | Tb927.6.1500 | ADS1 | |

| PAP | Phosphatidic acid phosphatase | Tb927.6.1820 | PAH1/LPP1 | |

| DAGK | DAG kinase | Tb927.8.5140 | DGK1 | |

| DAGAT | DAG acyltransferase | Tb11.18.0008 Tb927.3.1700 |

DGA1 | |

| CK | Choline kinase 2 | Tb11.18.0017 | Both | CK1/2 |

| CCT | Choline-phosphate cytidylyltransferase | Tb927.10.12810 | PRO | CCT1 |

| CPT | Choline phosphotransferase | Tb927.10.8900 | PRO | CPT1 |

| EK | Ethanolamine kinase 1 | Tb927.5.1140 | PRO | EK1/2 |

| ECT | Ethanolamine-phosphate cytidylyltransferase | Tb11.01.5730 | Both | ECT1 |

| EPT | Ethanolamine phosphotransferase | Tb927.10.13290 | Both | EPT1 |

| CTPS | CTP synthase | Tb927.1.1240 | BSF | URA7/8 |

| CLS | Cardolipin synthase | Tb927.4.2560 | PRO | CRD1 |

| PGPS | Phosphatidylglycerophosphate synthase | Tb927.8.1720 | PRO | PGPS |

| PSS/PSS2 | PS synthase/PS synthase-2 | Tb927.7.3760 | Both | CHO1/PSS2 |

| PSD | Phosphatidylserine decarboxylase | Tb09.211.1610 | BSF | PSD1/2 |

| INO1 | Inositol-3-phosphate synthase | Tb927.10.7110 | BSF | INO1 |

| PIS | Phosphatidylinositol synthase | Tb09.160.0530 | Both | PIS1 |

| PIKn | PI3 kinase Class (III) | Tb927.8.6210 | ||

| PIKn | PI4 kinase | Tb927.4.1140 | PiK1 | |

| PIKn | PI4 kinase | Tb927.3.4020 Tb927.4.800 Tb927.4.420 |

Stt4 | |

| PIKn | PIK-related | Tb927.1.1930 Tb927.2.2260 Tb11.01.6300 |

||

| GPI-PLC | GPI phospholipase C | Tb927.2.6000 | No (BSF) | |

| SMase | Neutral sphingomyelinase | Tb927.5.3710 | Both | ISC1 |

| PLA1 | Phospholipase A1 | Tb927.1.4830 | No (both) | N/A |

| LPLA1 | Lyso-phospholipase A1 | Tb09.211.3650 | No (both) | N/A |

| ALG7 | UDP-GlcNAc:Dol-P GlcNAc-1-P transferase | Tb11.01.2220 | ALG7 | |

| ALG1 | GDP-Man:GlcNAc2-PP-Dol β-1,4-mannosyltransferase | Tb927.10.13210 | ALG1 | |

| ALG2 | GDP-Man:Man1 GlcNAc2-PP-Dol α-1,3-mannosyltransferase | Tb927.4.2230 | ALG2 | |

| ALG11 | α-1,2-Mannosyltransferase | Tb09.211.0860 | ALG11 | |

| ALG3 | Dol-P-Man α-1,3-mannosyltransferase | Tb927.10.6530 | No (BSF) | ALG3 |

| ALG9 | Dol-P-Man:Man5GlcNAc2-PP-Dol α-1,2-mannosyltransferase | Tb927.6.1140 | ALG9 | |

| ALG12 | Dol-P-Man:Man7GlcNAc2-PP-Dol α-1,6-mannosyltransferase | Tb927.2.4720 | ALG12 | |

| OST | Subunit of the oligosaccharyltransferase complex | Tb927.5.890 Tb927.5.900 Tb927.5.910 |

STT3 (OST) | |

| RFT1 | Man5GlcNAc2-P-P-Dol translocase | Tb11.01.3540 | RFT1 | |

| GDMPP | GDP-Man pyrophosphorylase | Tb927.8.2050 | BSF | PSA1 |

| DOLK | Dolichol kinase | Tb09.211.3740 | Both | SEC59 |

| DPMI | Dol-P-Man synthase | Tb927.10.4700 | Both | DPM1 |

| CHW8 | Dol-PP phosphatase | Tb927.6.1820 | BSF | CHW8/ CAX4 |

| (GT) | GPl-GlcNAc transferase | |||

| TbGPI13 | Tb927.2.1780 | GPI3 | ||

| TbGPI12 | Tb927.3.4570 | GPI2 | ||

| TbGPI15 | Tb927.10.6140 | GPI15 | ||

| TbGPI19 | GPI19 | |||

| TbGPI1 | GPI1 ERI1 |

|||

| (PIG-L) TbGPI2 |

GlcNAc-PI de-N-acetylase | Tb11.01.3900 | BSF/ No(PRO) |

GPI2 |

| (MT-I) TbGPI14 |

α-1-4-Mannosyltransferase (MT-I) | Tb927.6.3300 | GPI14 PBN1 |

|

| (MT-II) TbGPI18 |

α-1-6-Mannosyltransferase (MT-II) | Tb927.10.13160 | GPI18 | |

| (MT-III) TbGPI10 |

α-1-2-Mannosyltransferase (MT-III) | Tb927.10.5560 | BSF | GPI10 |

| IAT | Inositol acyltransferase | n.i. | GWT1 | |

| (ET) | Ethanolamine-phosphate transferase | |||

| TbGPI13 | Tb11.02.2720 | GPI13 | ||

| TbGPI11 | Tb927.10.13290 | GPI11 | ||

| DeAc | GPI inositol deacylase | |||

| TbGPIdeAc, TbGPIdeAc2 |

Tb927.3.2610 | BSF | BST1 | |

| TbGUP1 | GPI remodellase | Tb10.61.0380 | No (BSF) | GUP1 |

| Transamidase TbGPI8 TbGAA1 TbGPI16 |

GPI transamidase subunit 8 GPI transamidase subunit Gaa1 GPI transamidase subunit 16 |

Tb927.10.13860 Tb927.10.210 N/A |

BSF/ No(PRO) BSF/ No(PRO) |

GPI8 GAA1 GPI17 |

| TTA1 | Tb927.4.1920 | GPI16 | ||

| TTA2 | GPI transamidase subunit Tta1 GPI transamidase subunit Tta2 |

N/A Tb11.01.7400 Tb927.10.5080 |

GAB1 | |

| AcCS | Acetyl-CoA synthetase | Tb927.8.2520 | ACS1 | |

| AAT | Acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase | Tb927.8.2540 | ERG10 | |

| HMS | HMG-CoA synthase | Tb927.4.2700 | ERG13 | |

| HMR | HMG-CoA reductase | Tb927.6.4540 | HMG1/2 | |

| MK | Mevalonate kinase | Tb927.4.4070 | ERG12 | |

| PMK | Phosphomevalonate kinase | Tb09.160.3690 | ERG8 | |

| MDD | Mevalonate-diphosphate decarboxylase | Tb927.10.13560 | BSF | ERG19 |

| IDI | Isopentenyl-diphosphate isomerase | Tb09.211.070 | BSF | IDI |

| FPS | Farnesyl-pyrophosphate synthase | Tb927.7.3360 | BSF | ERG20 |

| PFT | Protein farnesyltransferase α-subunit Protein farnesyltransferase β-subunit |

Tb927.3.4490 Tb927.7.460 |

BSF | RAM1 |

| SQS | Squalene synthase | Tb927.8.7120 | ERG9 |

n.i., no gene identified.

Indicates if a gene product is essential for parasite growth in culture; BSF, bloodstream forms; PCF, procyclic forms; both, essential in both bloodstream and procyclic forms; no, not essential.

The corresponding S. cerevisiae genes.

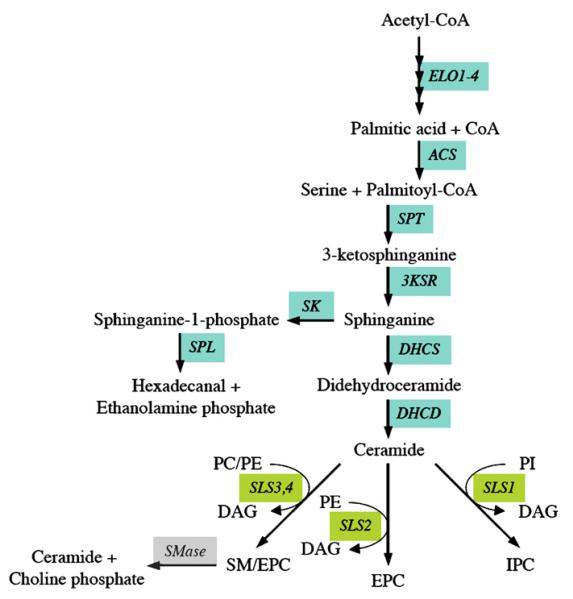

Fig. 2.

Predicted pathways for sphingolipid biosynthesis in T. brucei. Enzymes for which candidate genes have been identified in the T. brucei gene DB are indicated; see Table 1 for the abbreviations of the enzymes.

3.3. Fatty acid activation

Fatty acids normally undergo activation to CoA derivatives prior to their utilization in anabolic and catabolic pathways, such as core glycerophospholipid biosynthesis, phospholipid reacylation, fatty acid elongation, cholesterol ester formation, and β-oxidation. Activated fatty acids also serve a variety of protein targeting and regulatory roles including protein acylation, enzyme activation/inhibition, cell signaling, and protein transport [51,52]. N-myristoylation in T. brucei has been validated as drug target [53] and efforts by academia are now being made to obtain drug-like lead compounds [54].

Activation of fatty acids is generally accomplished using a family of enzymes, termed fatty acyl-CoA synthetases (ACSs). Five out of eight potential T. brucei ACSs have been characterised (Fig. 2, Table 1). TbACS1–4 are found in a tandem array and are constitutively expressed in both main life cycle stages, with TbACS3 being the dominant form. TbACS1, TbACS3, and TbACS4 show specificity towards C12:0–C14:0, C14:0–C16:0, and C14:0–C18:0, respectively, while TbACS2 prefers C10:0 [55]. TbACS5 is not essential in either of the main life cycle stages, despite it having a preference for C14:0 (G.S. Richmond and T.K. Smith, unpublished data).

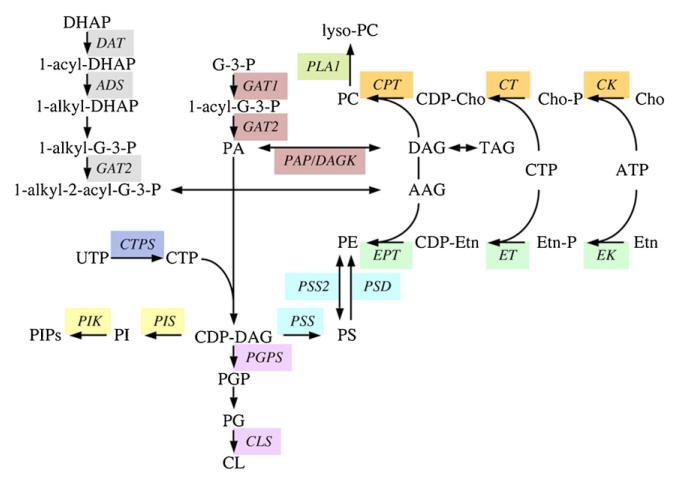

3.4. Dihydroxyacetonephosphate and glycerol-3-phosphate formation

A significant proportion of the glycerophospholipids have ether-linked aliphatic, i.e. alkyl or alk-1-enyl, chains attached to the sn-1 position of the glycerol backbone (see above). However, their function(s) and essentiality in T. brucei are unknown. Ether-linked lipids are de novo synthesised from dihydroxyacetonephosphate, via acyl-CoA:dihydroxyacetonephosphate acyl-transferase, alkyl-dihydroxyacetonephosphate synthase and alkyl-dihydroxyacetonephosphate oxidoreductase [56] (Fig. 3, Table 1). The putative enzymes in T. brucei have been shown to be associated with glycosomal fractions [57,58]. To date, only the alkyl-dihydroxyacetonephosphate synthase has been recombinantly expressed and characterized [59].

Fig. 3.

Predicted pathways for glycerophospholipid biosynthesis in T. brucei. Enzymes for which candidate genes have been identified in the T. brucei gene DB are indicated; see Table 1 for the abbreviations of the enzymes.

3.5. De novo ceramide synthesis

Ceramide, the hydrophobic precursor of sphingolipids, consists of a sphingoid long-chain base to which a fatty acyl chain is attached via an amide bond. Its synthesis occurs in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and starts with the conversion of serine and fatty acyl-CoA into 3-ketosphinganine by serine palmitoyltransferase complex (reviewed by [60,61]). Subsequently, the reaction product is reduced to sphinganine by 3-ketosphinganine reductase. Sphinganine can now enter two pathways, the phosphorylation to the lipid mediator, sphinganine-1-phosphate, or the acylation to dihydroceramide, which in turn, becomes desaturated to ceramide (Fig. 2, Table 1).

Experimental evidence that the pathway of de novo ceramide synthesis is active in T. brucei has been obtained by labeling procyclic trypanosomes in culture with radioactive serine, which is readily incorporated into sphingolipids [15,18]. Recently, a similar observation has also been made in T. congolense procyclic forms in culture (P. Bütikofer, E. Greganova and A. Acosta-Serrano, unpublished data). A search of the T. brucei genome reveals candidate genes for ceramide biosynthesis (Table 1). Both T. brucei bloodstream and procyclic forms clearly depend upon de novo sphingoid base synthesis, as was demonstrated by blocking serine palmitoyltransferase in these life cycle stages, resulting in growth inhibition and delayed kinetoplast segregation and aberrant cytokinesis, respectively [18,62]. In contrast, Leishmania parasites lacking serine palmitoyltransferase are viable as long as they are substituted with ethanolamine, a metabolic product of sphingoid base degradation [63,64].

4. The Kennedy pathway

4.1. CDP-ethanolamine branch

PE, the second most abundant glycerophospholipid class in T. brucei bloodstream and procyclic forms, can be generated via its CDP-activated intermediate, CDP-ethanolamine, by a reaction sequence termed the ‘Kennedy pathway’, after its original discovery by Kennedy and Weiss [65]. It involves the phosphorylation of ethanolamine by ethanolamine kinase, followed by activation of ethanolamine-phosphate to CDP-ethanolamine via ethanolamine-phosphate cytidylyltransferase. Finally, the activated head group is transferred to diradylglycerol by ethanolamine phosphotransferase (Fig. 3, Table 1). The first two reactions are catalyzed by cytosolic enzymes, whereas the third step is mediated by an integral membrane protein of the ER (reviewed by [66]).

All enzymes involved in PE formation by the ‘Kennedy pathway’ in T. brucei have been identified and experimentally confirmed [15–17,67]. Disruption of the CDP-ethanolamine branch in procyclic forms using RNA interference (RNAi) resulted in severe growth phenotypes and revealed dramatic changes in cellular PE, PC and PS levels [15,16]. In addition, a block in PE synthesis caused alterations in mitochondrial morphology and the formation of multinucleate parasites [68]. Similar observations were also made in T. brucei bloodstream forms after knocking out ethanolamine-phosphate cytidylyltransferase, which validates the Kennedy pathway as a potential drug target [17].

4.2. CDP-choline branch

A similar pathway, involving CDP-activated choline, also leads to the formation of PC, the most abundant phospholipid class in eukaryotic cells, including T. brucei. Candidate trypanosome genes for all three enzymes of the CDP-choline branch of the ‘Kennedy pathway’ have been identified (Fig. 3, Table 1). The first and third enzymes, choline kinase [67] and choline phosphotransferase [15], have been characterized experimentally and were found to show dual specificities for choline and ethanolamine, and CDP-choline and CDP-ethanolamine, respectively. Choline kinase is essential in T. brucei bloodstream forms (S.A. Young, F. Gibellini and T.K. Smith, unpublished data), indicating the importance of this pathway in choline metabolism of the parasite. The second enzyme, choline-phosphate cytidylyltransferase, which, in analogy to its homologues in mammalian cells or to T. brucei ethanolamine-phosphate cytidylyltransferase in the CDP-ethanolamine branch, likely represents the rate-limiting reaction (S.A. Young and T.K. Smith, unpublished data).

4.3. Cross-talk between the two branches

An alternative route for PC synthesis in eukaryotic cells involves methylation of PE to PC, catalyzed by phosphatidylethanolamine N-methyltransferases [66]. However, in contrast to Leishmania, the genomes of T. brucei and T. cruzi show no homologues for these enzymes. In addition, labeling of T. brucei bloodstream and procyclic forms with radiolabeled and stable isotope labeled ethanolamine, or serine, showed no evidence for the conversion of PE to PC [15,17,26,42] (T.K. Smith and P. Bütikofer, unpublished data), indicating that this pathway is absent in trypanosomes. This evidence suggests that T. brucei are auxotrophic for choline, i.e. they depend on choline scavenged from the host. Interestingly, experiments involving RNAi-mediated gene silencing of ethanolamine phosphotransferase revealed that a block in PE synthesis via the CDP-ethanolamine branch led to increased PE formation via choline phosphotransferase, which shows dual specificity for the substrates of both branches (see above), thereby changing the molecular species composition of PE from mostly alk-1-enyl-acyl-type species to mostly diacyl-type species [15]. Thus, parasites try to compensate for a lack of one subclass of PE by up-regulating another subclass, indicating that the PE content of T. brucei is tightly regulated, and essential, for its survival.

5. PS formation and metabolism

5.1. PS synthesis

In prokaryotes and yeast, PS is formed from serine and CDP-diacylglycerol in a reaction catalyzed by PS synthase [69]. In contrast, in mammalian cells, PS synthesis is mediated by two serine-exchange enzymes, PS synthase-1 (PSS1) and PS synthase-2 (PSS2). In plants, both pathways have been identified (reviewed by [70]). PSS1 and PSS2, which are localized in mitochondria-associated membranes, differ in their substrate specificity. Whereas PSS1 utilizes PC for the head group exchange reaction, PSS2 is specific for PE as substrate. The two enzymes share 32% amino acid identity and are membrane bound via multiple transmembrane domains [70]. Studies using knockout mice showed that deletion of either PSS1 or PSS2, but not both, is compatible with mouse viability [71–73].

In T. brucei, PS represents a minor membrane component [7,15]. Its biosynthetic pathway has not been firmly established [15,17]. A candidate gene encoding a putative PS synthase, or a PSS2, has been identified in the T. brucei genome (Fig. 3, Table 1). Experiments to establish the route for PS formation in T. brucei are currently under way in our laboratories.

5.2. PS metabolism

In both prokaryotes and eukaryotes, PS is used as the only (in most bacteria) or primary (in most other cell types) source for PE formation via PS decarboxylation ([74]; recently reviewed by [75]). The reaction is catalyzed by two types of enzymes, PS decarboxylase I, comprising bacterial and mitochondrially localized enzymes, and PS decarboxylase II, comprising enzymes associated with the endomembrane system. The two types of enzymes share a highly conserved GST motif in the C-terminal region of the proteins, which is the autocatalytic cleavage and processing site for the formation of the α- and β-subunits [76,77]. Although PS decarboxylases are present in many prokaryotic and eukaryotic organisms, the relative contribution of PS decarboxylation to cell viability, or function, greatly varies [75].

In T. brucei, decarboxylation of PS to PE has been shown to occur in procyclic forms [15]. However, the pathway contributes little to PE formation since depletion of cellular PE in procyclic trypanosomes by disrupting the CDP-ethanolamine branch of the Kennedy pathway could not be compensated by increased PE formation via decarboxylation of PS [15]. In addition, stable isotope labelling experiments showed virtually no PE formation from PS in T. brucei bloodstream forms in culture [17]. A gene encoding a putative PS decarboxylase I has been identified in the T. brucei genome (Fig. 3, Table 1) and was found to be expressed in both main life cycle stages. In addition, recombinant T. brucei PS decarboxylase I has been shown to be correctly processed and catalytically active, implying its activity may be highly regulated or restricted in the parasite (T.K. Smith, unpublished data).

6. Sphingolipid metabolism

6.1. Biosynthesis of sphingophospholipids

The hydrophilic head groups for the formation of SM, IPC and EPC, are transferred to their common hydrophobic precursor lipid, ceramide, from the glycerophospholipids PC, PI and PE, respectively. Two SM synthases have been identified in the Golgi and the plasma membrane of mammalian cells [78–80] and an IPC synthase has been found in the Golgi of the yeast, S. cerevisiae [81]. In addition, activities responsible for EPC formation have been described in mammalian cells [82–84].

In T. brucei, a sphingolipid synthase (SLS) gene family consisting of four tandemly linked genes has recently been identified (Fig. 2, Table 1) [19]. The deduced enzymes show very high degrees of amino acid identity between each other and are predicted to contain multiple transmembrane domains [19,85]. RNAi against a nucleotide sequence common to all four putative SLS genes showed that sphingolipid synthesis is essential for growth of T. brucei bloodstream forms in culture [19,86]. However, the SLS-depleted parasites showed little decrease in cellular SM and EPC levels, suggesting that the turnover of these lipids may be very low. Expression of the T. brucei SLS4 gene in Leishmania major promastigotes demonstrated that its product has SM and EPC synthase activity [19]. This finding is in contrast to a report claiming that the product of the SLS4 gene is involved in SM and IPC formation [86]. Interestingly, detailed sphingolipid analysis revealed that T. brucei procyclic forms contain significant amounts of SM and IPC, while bloodstream forms lack IPC but contain small amounts of EPC [19], suggesting that the four putative SLSs may be differentially expressed in the main life cycle forms and likely encode enzymes with different substrate specificities. This has recently been confirmed by showing that stumpy bloodstream forms (i.e. parasites differentiating from bloodstream to procyclic cells) contain IPC and that the expression of the corresponding SLS is increased in this life cycle form [87]. Recent unpublished data using a cell-free expression system revealed that SLS1 and 2 primarily synthesise IPC and EPC, respectively, while SLS3 and 4 are bifunctional SM/EPC synthases (J.D. Bangs, personal communication). A similar dual substrate specificity for SM and EPC formation has recently been described for SLS2 in mammalian cells [88].

6.2. Catabolism

Intracellular degradation of sphingolipids is achieved by sphingomyelinases (SMases), which catalyse sphingolipid hydrolysis to ceramide and a corresponding head group, i.e. phosphorylcholine in the case of SM degradation. Various SMases have been described, differing in subcellular localisation and tissue specificity. In many cases, SMases are activated by growth factors, cytokines, chemotherapeutic agents, irradiation, nutrient removal and other related stress factors (reviewed by [89,90]).

The T. brucei genome contains candidate genes for two putative acidic SMases and one neutral SMase (Fig. 2, Table 1). The neutral SMase, which is homologous to the yeast enzyme, Isc1, has recently been found to play a crucial role in the exocytic flux of variant surface glycoprotein (VSG) to the cell surface, i.e. flagellar pocket (S.A. Young and T.K. Smith, unpublished data). In Leishmania, SMase was shown to be involved in the degradation of host SM [91].

As mentioned above, in Leishmania promastigotes ceramide degradation by sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase (Fig. 2, Table 1) has been shown to be essential for growth. Apparently, this pathway is required for the formation of ethanolamine-phosphate, a direct product of the reaction, for anabolic processes [64]. Preliminary data indicate that this enzyme is also functional in T. brucei procyclic forms (J. Jelk and P. Bütikofer, unpublished data).

7. CDP-DAG synthesis

CTP and phosphatidic acid are utilized by the rate limiting and tightly regulated enzyme, CDP-diacylglycerol (CDP-DAG) synthase, to form CDP-DAG, which is a central metabolite in the de novo synthesis of PI, PS, PG and CL. Genes encoding CDP-DAG synthases have been cloned from several organisms and show high sequence identity, suggesting conservation during evolution. Homologues of CDP-DAG synthases have been found in all eukaryotic organisms sequenced to date and some appear to have multiple copies. Mammals, for example, appear to have two copies, which are differently expressed and regulated [92–95].

In T. brucei, a putative CDP-DAG synthase gene has recently been identified (Table 1), and its product was found to be essential in both bloodstream and procyclic forms of the parasite (A. Lilley and T.K. Smith, unpublished data). Interestingly, the related organisms T. cruzi and Leishmania appear to have two CDP-DAG synthase genes, one clustering with the T. brucei homologue in phylogenetic analysis and one clustering with bacterial homologues.

The previous observation that the T. brucei PI synthase is located in the ER and Golgi [38,96] (see below) suggests that CDP-DAG may be also be synthesised in both organelles, or transported from one to the other. In addition, since CDP-DAG is also a precursor for PG and CL synthesis, which most likely takes place in mitochondria, where these lipids are required to maintain organelle integrity, membrane potential and function (see below), CDP-DAG must either be synthesized in, or transported to, the mitochondria.

8. PG and CL synthesis

CL, also called diphosphatidylglycerol, represents a component of the plasma membrane of many Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and the inner mitochondrial and chloroplast membranes of eukaryotes. Due to its chemical structure, consisting of four acyl chains and a small negatively charged head group, CL has the tendency to form non-bilayer structures and can organize into membrane sub-domains (recently reviewed by [97,98]). In addition, CL plays an important role in the stabilization and function of many mitochondrial proteins or protein complexes (recently reviewed by [99,100]).

The synthesis of CL in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes starts with the activation of phosphatidic acid by CTP (recently reviewed by [101]). Subsequently, the phosphatidyl group is transferred to the sn-1 hydroxyl group of glycerol-3-phosphate to form phosphatidylglycerophosphate (PGP), which becomes dephosphorylated to phosphatidylglycerol (PG). In prokaryotes, PG receives the additional phosphatidyl group from another PG molecule, whereas in eukaryotes, the phosphatidyl group is transferred from phosphatidyl-CMP. The prokaryotic CL synthase catalyzes the reaction by a phospholipase D-type transesterification mechanism that is fully reversible (reviewed by [102]) and, thus, may also be involved in CL degradation. In contrast, the eukaryotic enzyme catalyzes CL formation by an irreversible phosphatidyl-transferase mechanism, a type of reaction that is also involved in PS, PI and PG synthesis. In Escherichia coli, CL synthase is bound to the inner membrane, with the catalytic site facing the periplasm [103], whereas in rat liver mitochondria, it localizes to the inner membrane and the active site faces the matrix [104].

In T. brucei procyclic forms, CL has been identified in isolated mitochondria and characterized using mass spectrometry, revealing several molecular species [25]. In contrast, at present no information is available on the pathway for PG and CL formation. However, the genome of T. brucei shows candidate genes encoding putative PGP synthase and CL synthase (Fig. 3, Table 1). Preliminary data indicate that both enzymes are essential for normal growth in T. brucei procyclic forms (M. Serricchio and P. Bütikofer, unpublished data).

9. Inositol phospholipid metabolism

9.1. PI synthesis

PI is a ubiquitous eukaryotic phospholipid, which serves as a precursor for the phosphorylated PI species (PIPs), second messenger molecules and GPI anchors. PI is synthesised via the action of a PI synthase using myo-inositol and CDP-DAG and releasing CMP, and has been studied in such organisms as S. cerevisiae, Arabidopsis thaliana and Toxoplasma gondii [105–107].

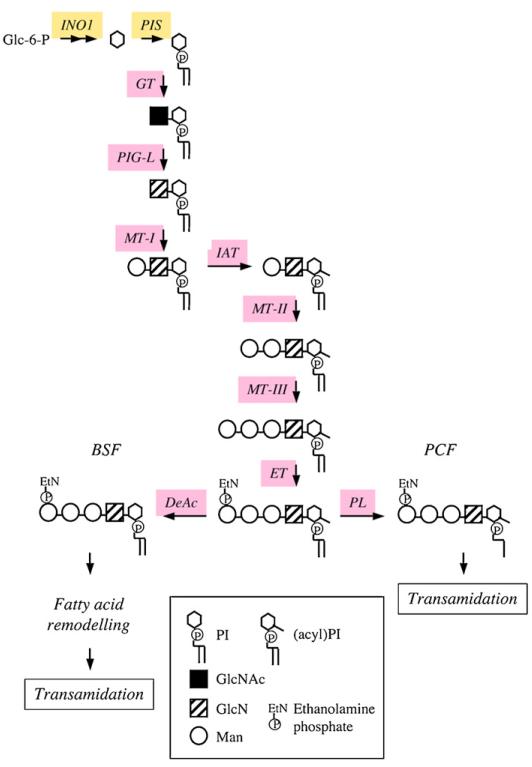

The conundrum that bloodstream form GPI anchors cannot be in vivo labelled with [3H]inositol led to the discovery that de novo synthesis was responsible for supplying myo-inositol for PI, and GPI, synthesis in the ER (Figs. 3 and 4, Table 1) [96]. This observation was confirmed by immunofluorescence studies showing that the PI synthase is localized in the ER and the Golgi, where it utilizes imported extracellular inositol to generate the majority of bulk PI in the parasite [38].

Fig. 4.

Pathway for GPI biosynthesis in T. brucei. Enzymes for which candidate genes have been identified in the T. brucei gene DB are indicated; see Table 1 for the abbreviations of the enzymes. BSF, bloodstream forms; PCF, procyclic forms.

9.2. Formation of PIPs

In many eukaryotes, trafficking, endocytosis, and Golgi maintenance are PI-mediated events (reviewed by [108]). PIPs are known to effect proteins of eukaryotic components of secretory pathways, some of which have been identified in T. brucei, i.e., clathrin, adapter proteins, and Rab GTPases [109].

Several putative PI kinases have been identified in the genome (Fig. 3, Table 1), however the apparent lack of genes encoding class I or II PI 3-kinases suggests that T. brucei may not have PI 3-kinase-dependent signaling pathways. However, an identified class III PI 3-kinase has been implicated in Golgi segregation and endocytotic trafficking [110]. The T. brucei database also contains genes for two putative PI 4-kinases, TbPI4KIII-α and TbPI4KIII-β, the latter of which is required for maintenance of Golgi structure, protein trafficking, normal cellular shape, and cytokinesis in procyclic form trypanosomes [111]. In addition, the T. brucei genome reveals four putative PI monophosphate kinases, a type I PI4P 5-kinase, a type III PI3P 5-kinase (PIKFYVE), and two type II PI monophosphate kinase isoforms. Collectively, the presence of these putative enzymes suggests that T. brucei can, in principle, synthesize all of the mono- and bisphosphorylated PI species. Recently, these classes of PIPs have been identified in a comprehensive lipidomics analysis (T.K. Smith, unpublished data).

10. GPI biosynthesis

T. brucei bloodstream forms avoid the hosts’ innate immune system by undergoing antigenic variation, which involves switching of GPI-anchored VSGs [112]. Despite the variation in the VSG protein, the GPI core structure attached to protein remains unchanged and comprises of ethanolamine-PO4-6Manα1-2Manα1-6Manα1-4GlcNα1-6D-myo-inositol-1-PO4-dimyristoylglycerol [113]. The biosynthesis of GPI anchors has been validated both genetically and chemically as a potential therapeutic drug target in bloodstream form T. brucei [114–117].

GPI biosynthesis and attachment to protein has been elucidated in bloodstream form T. brucei, mainly through the use of a cell-free system consisting of washed membranes in the presence of either UDP-GlcNAc or synthetic substrate analogues and radiolabelled GDP-mannose, allowing the stepwise formation of radiolabelled GPI intermediates (Fig. 4, Table 1) ([118–122]; reviewed in [123,124]). The initial step is catalysed by a sulfhydryl dependent multi-protein complex, which transfers GlcNAc from UDP-GlcNAc to PI to form GlcNAc-PI. The PI utilized for GPI biosynthesis in the ER is made almost exclusively from de novo synthesized inositol [96]. GlcNAc-PI is then de-N-acetylated to form GlcN-PI [125–127], and is a pre-requisite for further processing, i.e. mannosylation. Numerous substrate analogues of GlcNAc-PI have allowed the specificity of this zinc dependent metalloenzyme to be explored, leading to the formation of parasite specific potent suicide inhibitors [117,128,129]. Subsequent mannosylation of GlcN-PI involves three distinct dolichol-phosphate-mannose dependent mannosyltransferases. In T. brucei, unlike most other eukaryotic GPI pathways, the addition of the first mannose to GlcN-PI precedes inositol acylation (reviewed in [123,124]). Inositol acylation is an essential pre-requisite for the transfer of ethanolamine-phosphate from PE to the 6-hydroxyl group of the third mannose of Man3-GlcN-(acyl)PI. Again various synthetic substrate analogues have been used to explore the specificity of the mannosyltransferases and the inositol acyltransferase (reviewed by [130]). Unusually, inositol acylation and subsequent inositol deacylation are inhibited specifically by the serine protease inhibitors, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and diisopropylfluorophosphate, respectively [122,131]. The GPI precursor, EtN-P-Man3-GlcN-PI, is then subjected to fatty acid remodeling [11], where a stepwise replacement of the acyl chains with myristate is mediated by two phospholipases and two myristoyl-CoA dependent acyltransferases, resulting in the mature GPI, EtN-P-Man3-GlcN-(dimyristoyl-)PI. Subsequently, this mature GPI is covalently attached to VSG, mediated by the T. brucei transamidase complex [132]. A specific C-terminal GPI addition signal peptide is cleaved, forming a new C-terminus, by activation of the carbonyl group of the ω amino acid, allowing nucleophilic attack on the activated carbonyl by the amino group of the ethanolamine-phosphate linked to the third mannose of the mature GPI precursor forming a new amide linkage [133]. Finally, mature GPI-anchored VSG destined for exocytosis to the flagellar pocket, via the recycling endosomes, undergoes a process called myristate exchange, whereby the existing myristates of the GPI anchor are replaced with two new myristates [12,14]. A candidate gene product, TbGup1, involved in the addition of myristate to the sn-2 position of the glycerol backbone during lipid remodeling of GPI lipids and proteins, has been reported [134].

11. Other pathways involved in lipid homeostasis

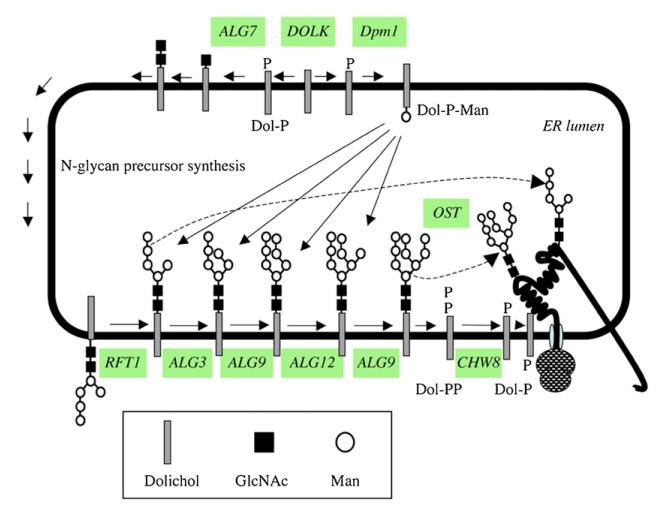

11.1. N-glycosylation pathway

All variants of VSG protein are GPI-anchored and modified with one to three N-glycans. Seminal work by the Ferguson group [135,136] has shown that T. brucei parasites are unusual amongst eukaryotes, as they are able to transfer en bloc oligomannose structure or biantennary structures by the different homologues of the oligosaccharyltransferase STT3 subunits identified in the genome in a site-specific manner, i.e. Man9GlcNAc2-PP-Dol for Asn-428 and Man5GlcNAc2-PP-Dol for Asn-263 of VSG221 (Fig. 5, Table 1) [137]. Interestingly, some of the glycosyltransferases involved in making and processing high mannose structures are not essential [135,136]. However, activation of mannose as either GDP-mannose or dolichol-phosphate-mannose is essential in the bloodstream form of the parasite [138,139] (J. Nunes and T.K. Smith, unpublished data). Interestingly, unlike in most other eukaryotes, the recycling of Dol-PP to Dol-P by the gene product of CHW8 (Table 1) is essential in T. brucei (T. Chang and T.K. Smith, unpublished data).

Fig. 5.

Predicted pathway for N-glycosylation in T. brucei. Enzymes for which candidate genes have been identified in the T. brucei gene DB are indicated; see Table 1 for the abbreviations of the enzymes.

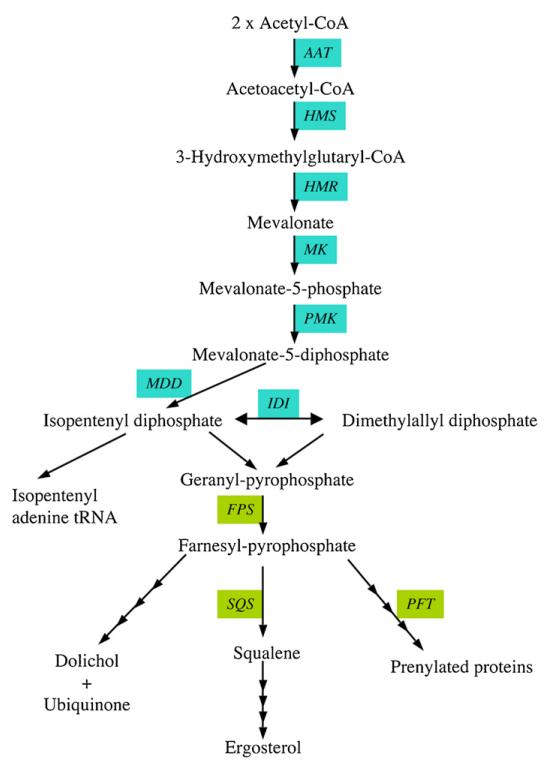

11.2. Mevalonate pathway

The mevalonate pathway is a target for drug intervention to treat many diseases, since it provides the essential five carbon building blocks used in the biosynthesis of several ubiquitous families of essential molecules, such as sterols, dolichols, ubiquinones, carotenoids and prenylated proteins, that are essential for many cellular functions (reviewed by [140]). Humans and trypanosomes share the same pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis, however, the T. brucei genome reveals that the trypanosome mevalonate pathway is more related to that found in bacteria and archae than that in eukaryotes (Fig. 6, Table 1).

Fig. 6.

Predicted pathways for mevalonate and isoprenoid biosynthesis in T. brucei. Enzymes for which candidate genes have been identified in the T. brucei gene DB are indicated; see Table 1 for the abbreviations of the enzymes.

All isoprenoid compounds are synthesised from isopentenyl-diphosphate and dimethylallyl diphosphate, the later being formed from the former by isopentenyl pyrophosphate isomerase. Preliminary findings suggest that the T. brucei isopentenyl pyrophosphate isomerase is a Type II, riboflavin-dependent isomerase closely related to archae homologues (T. Chang and T.K. Smith, unpublished data). In addition, both the isopentenyl pyrophosphate isomerase and the mevalonate-diphosphate decarboxylase have been found to be essential in T. brucei bloodstream forms, thus for the first time validating the T. brucei mevalonate pathway as a drug target (T. Chang, E. Byres, W.N. Hunter and T.K. Smith, unpublished data). Crystal structures for two of the trypanosomatid enzymes have recently been reported, possibly allowing future in silico drug design [141,142]. Localisation of the components of the pathway seems to be different between trypanosomatids, but T. brucei hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase activity is associated with the mitochondria [143]. Several drugs targeting enzymes within the mevalonate pathway have been shown to have anti-parasitic activity [35,144,145]. Trypanosomes have an active isoprenoid metabolism, which differs in several aspects from mammals, in that they make dolichols of 11 and 12 isoprene units, ubiquinone with 9 isoprene units and a series of sterols. Bloodstream form trypanosomes acquire most of the cholesterol from their mammalian host via receptor-mediated endocytosis of low density lipoproteins [4,30]. Procyclic form trypanosomes, instead, are known to de novo synthesize a set of unconventional sterols [29], and several enzymes involved in sterol synthesis in trypanosomatids have recently been identified [146–149]. Since 25-azalanosterol, an inhibitor of sterol methyltransferase, was found to inhibit growth of both bloodstream and procyclic form T. brucei parasites, sterol biosynthesis seems essential in both life cycle stages [29]. In addition, bisphosphonate inhibitors of farnesyl diphosphate synthase, which was shown to be essential in T. brucei [150], inhibit proliferation of T. brucei [151]. Furthermore, extensive studies on protein prenylation, mediated by farnesyltransferase and two geranylgeranyltransferases, have shown that protein prenylation is essential in T. brucei (reviewed in [152,153]). The utilization of ‘piggy-back medicinal chemistry’ of anti-cancer research in this area may lead to the identification of promising lead compounds [152,154].

11.3. Prostaglandin formation

In higher eukaryotes, bioactive precursors stored in glycerophospholipids and released by phospholipases have been recognized as important factors in signal transduction and in the generation of lipid mediators [155,156]. Phospholipase-modified membrane lipids are themselves important mediators in cellular processes, such as apoptosis, membrane trafficking and transport [157,158].

The fate of unsaturated fatty acids liberated from glycerophospholipids in T. brucei has not been studied in much detail. However, free arachidonic acid has been implicated in regulating calcium mobilization in procyclic form trypanosomes [159,160] and, in addition, has been shown to serve as a precursor for prostaglandin biosynthesis in T. brucei [161]. Although a putative mechanism for the release of arachidonic acid from T. brucei glycerophospholipids has been proposed [162], the phospholipases mediating these events in T. brucei are not known.

11.4. Phospholipases

Phospholipases form a diverse series of enzymes that exist in almost every type of cell and are optimized to hydrolyze glycerophospholipids at specific ester bonds. Despite their considerable variation in structure and function, they can be classified into two sets, i.e. the acyl hydrolases and the phosphodiesterases, according to the cleavage of the ester bond for which they are specific. Phospholipase A1, phospholipase A2, phospholipase B, and lyso-phospholipase A1/2 constitute the acyl hydrolases, whereas the phosphodiesterases are represented by phospholipase C and phospholipase D. Three general functions can be ascribed to the physiologic relevance of phospholipases: they can (1) serve as digestive enzymes, i.e. A-type phospholipases are ubiquitous in snake and vespid venoms, (2) play important roles in membrane maintenance and remodeling, i.e. fatty acyl chains of glycerophospholipids can be cleaved and exchanged by acyl hydrolases and acyltransferases, respectively, and (3) regulate important cellular mechanisms, i.e. generate bioactive lipid molecules used in signal transduction.

To date, only two phospholipases have been characterized in T. brucei (Table 1), the GPI-hydrolyzing phospholipase C (GPI-PLC) and a PC-specific phospholipase A1 (PLA1). GPI-PLC is a C-type phospholipase implicated in the cleavage of the VSG GPI anchor, generating DAG and a 1,2-cyclic inositol-phosphate containing epitope linked to the GPI head group of VSG [163–165]. For many years, the subcellular localization of GPI-PLC in T. brucei bloodstream forms presented a topological problem for its putative role in VSG release from the surface of bloodstream form parasites during differentiation to procyclic forms. Work by several laboratories indicated that GPI-PLC faces the cytosol, or is localized in intracellular vesicles [166–169]. However, in a recent report, GPI-PLC has been localized to (a restricted area of) the plasma membrane [170], which is consistent with an earlier report [171], resolving the topological issue since the enzyme and its major substrate are located in the same compartment. Nevertheless, the biological role for GPI-PLC as a VSG lipase remains unclear, as the enzyme cannot be active in bloodstream form trypanosomes under normal conditions because it would hydrolyze and release the protective VSG surface coat.

The only other identified and characterised phospholipase from T. brucei is a cytosolic PLA1, which acts on PC and releases long polyunsaturated fatty acids (Fig. 2, Table 1) [172,173]. The gene of this enzyme may be a result of horizontal gene transfer from the proteobacterium Sodalis glossinidius, an intracellular endosymbiont of Glossina (tsetse) flies, the insect vector host of T. brucei.

The apparent absence of a T. brucei phospholipase D homologue, which normally catabolises PC and/or SM in other organisms, has led to the hypothesis that the action of a phospholipase D may have been substituted by the concerted actions of a PLA1 and a lyso-phospholipase A, the later of which has been characterized (T.K. Smith, unpublished data). Unfortunately, neither of these lipases are essential in T. brucei bloodstream and procyclic forms, implying the parasites may have an alternative means to catabolise PC, perhaps via the concerted actions of SM synthases and SMase.

Perspectives

In recent years, since the completion of the Tri-Tryp genomes, considerable progress has been made in the molecular biological characterisation of several lipid biosynthetic pathways. However many more genes and their products require detailed genetic and biochemical validation, including detailed enzymological studies, before we can take advantage and exploit possible differences in these pathways between humans and eukaryotic pathogens, such as T. brucei, towards the development of drugs against the diseases they cause.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jay Bangs for communicating unpublished data and Federica Gibellini for help with Fig. 1. Research in TKS’s laboratory is supported in part by a Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellowship (067441), and Wellcome Trust grant (086658) and studentships from the Wellcome Trust and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council. Research in PB’s laboratory is supported in part by Swiss National Science Foundation grant 31003A-116627 and Sinergia grant CRSII3 127300, and by COST action BM0802. PB thanks A. Macdonald for valuable input and the reviewers for helpful comments.

Abbreviations

- ACS

fatty acyl-CoA synthetase

- CoA

coenzyme A

- CL

cardiolipin

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- EPC

ethanolamine phosphorylceramide

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- GPI-PLC

glycosylphosphatidylinositol phospholipase C

- IPC

inositol phosphorylceramide

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

- PG

phosphatidylglycerol

- PGP

phosphatidylglycerophosphate

- PI

phosphatidylinositol

- PIPs

phosphorylated PI species

- PS

phosphatidylserine

- PSS1

PS synthase-1

- PSS2

PS synthase-2

- PLA1

phospholipase A1

- SM

sphingomyelin

- SMase

sphingomyelinase

- SLS

sphingolipid synthase

References

- [1].Simpson AG, Stevens JR, Lukes J. The evolution and diversity of kinetoplastid flagellates. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:168–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hannaert V, Bringaud F, Opperdoes FR, Michels PA. Evolution of energy metabolism and its compartmentation in Kinetoplastida. Kinetoplastid Biol Dis. 2003;2:11. doi: 10.1186/1475-9292-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Venkatesan S, Ormerod WE. Lipid content of the slender and stumpy forms of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense: a comparative study. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1976;53:481–7. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(76)90203-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dixon H, Ginger CD, Williamson J. Trypanosome sterols and their metabolic origins. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1972;41:1–18. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(72)90002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dixon H, Ginger CD, Williamson J. The lipid metabolism of blood and culture forms of Trypanosoma lewisi and Trypanosoma rhodesiense. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1971;39:247–66. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(71)90168-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Dixon H, Williamson J. The lipid composition of blood and culture forms of Trypanosoma lewisi and Trypanosoma rhodesiense compared with that of their environmemt. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1970;33:111–28. doi: 10.1016/0010-406x(70)90487-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Patnaik PK, Field MC, Menon AK, Cross GAM, Yee MC, Bütikofer P. Molecular species analysis of phospholipids from Trypanosoma brucei bloodstream and procyclic forms. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;58:97–106. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90094-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vial HJ, Eldin P, Tielens AGM, van Hellemond JJ. Phospholipids in parasitic protozoa. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2003;126:143–54. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00281-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Carroll M, McCrorie P. Lipid composition of bloodstream forms of Trypanosoma brucei brucei. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1986;83:647–51. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(86)90312-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].van Hellemond JJ, Tielens AG. Adaptations in the lipid metabolism of the protozoan parasite Trypanosoma brucei. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:5552–8. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Masterson WJ, Raper J, Doering TL, Hart GW, Englund PT. Fatty acid remodeling: a novel reaction sequence in the biosynthesis of Trypanosome glycosyl phosphatidylinositol membrane anchors. Cell. 1990;62:73–80. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90241-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Buxbaum LU, Raper J, Opperdoes FR, Englund PT. Myristate exchange. A second glycosyl phosphatidylinositol myristoylation reaction in African trypanosomes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30212–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Werbovetz KA, Englund PT. Glycosyl phosphatidylinositol myristoylation in African trypanosomes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1997;85:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(96)02820-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Buxbaum LU, Milne KG, Werbowetz KA, Englund PT. Myristate exchange on the Trypanosoma brucei variant surface glycoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1178–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Signorell A, Rauch M, Jelk J, Ferguson MA, Bütikofer P. Phosphatidylethanolamine in Trypanosoma brucei is organized in two separate pools and is synthesized exclusively by the Kennedy pathway. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:23636–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M803600200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Signorell A, Jelk J, Rauch M, Bütikofer P. Phosphatidylethanolamine is the precursor of the ethanolamine phosphoglycerol moiety bound to eukaryotic elongation factor 1A. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20320–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802430200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gibellini F, Hunter WN, Smith TK. The ethanolamine branch of the Kennedy pathway is essential in the bloodstream form of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Microbiol. 2009;73:826–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06764.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sutterwala SS, Creswell CH, Sanyal S, Menon AK, Bangs JD. De novo sphingolipid synthesis is essential for viability, but not for transport of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins, in African trypanosomes. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6:454–64. doi: 10.1128/EC.00283-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sutterwala SS, Hsu FF, Sevova ES, et al. Developmentally regulated sphingolipid synthesis in African trypanosomes. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70:281–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06393.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Beach DH, Holz GG, Anekwe GR. Lipids of Leishmania promastigotes. J Parasitol. 1979;65:203–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wassef MK, Fioretti TB, Dwyer DM. Lipid analysis of isolated surface membranes of Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Lipids. 1985;20:108–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02534216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Singh BN, Costello CE, Beach DH, Holz GGJ. Di-O-alkylglycerol, mono-O-alkylglycerol and ceramide inositol phosphates of Leishmania mexicana mexicana promastigotes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;157:1239–46. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhang K, Beverley SM. Phospholipid and sphingolipid metabolism in Leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2010;170:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Bertello LE, Gonçalvez MF, Colli W, de Lederkremer RM. Structural analysis of inositol phospholipids from Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigote forms. Biochem J. 1995;310:255–61. doi: 10.1042/bj3100255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Guler JL, Kriegova E, Smith TK, Lukes J, Englund PT. Mitochondrial fatty acid synthesis is required for normal mitochondrial morphology and function in Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Microbiol. 2008;67:1125–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Richmond GS, Gibellini F, Young SA, et al. Lipidomic analysis of bloodstream and procyclic form Trypanosoma brucei. Parasitology. doi: 10.1017/S0031182010000715. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Paul KS, Jiang D, Morita YS, Englund PT. Fatty acid synthesis in African trypanosomes: a solution to the myristate mystery. Trends Parasitol. 2001;17:381–7. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4922(01)01984-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lee SH, Stephens JL, Paul KS, Englund PT. Fatty acid synthesis by elongases in trypanosomes. Cell. 2006;126:691–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhou W, Cross GA, Nes WD. Cholesterol import fails to prevent catalyst-based inhibition of ergosterol synthesis and cell proliferation of Trypanosoma brucei. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:665–73. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600404-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Coppens I, Courtoy PJ. The adaptative mechanisms of Trypanosoma brucei for sterol homeostasis in its different life-cycle environments. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:129–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Denny PW, Field MC, Smith DF. GPI-anchored proteins and glycoconjugates segregate into lipid rafts in Kinetoplastida. FEBS Lett. 2001;491:148–53. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02172-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Tyler KM, Fridberg A, Toriello KM, et al. Flagellar membrane localization via association with lipid rafts. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:859–66. doi: 10.1242/jcs.037721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Samad A, Licht B, Stalmach ME, Mellors A. Metabolism of phospholipids and lysophospholipids by Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1988;29:159–69. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(88)90071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Coppens I, Baudhuin P, Opperdoes FR, Courtoy PJ. Receptors for the host low density lipoproteins on the hemoflagellate Trypanosoma brucei: purification and involvement in the growth of the parasite. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:6753–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Coppens I, Courtoy PJ. Exogenous and endogenous sources of sterols in culture adapted procyclic trypomastigotes of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1995;73:179–88. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(95)00114-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bowes AE, Samad AH, Jiang P, Weaver B, Mellors A. The acquisition of lysophosphatidylcholine by African trypanosomes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:13885–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Black S, Vandeweerd V. Serum lipoproteins are required for multiplication of Trypanosoma brucei brucei under axenic culture conditions. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989;37:65–72. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90103-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Martin KL, Smith TK. Phosphatidylinositol synthesis is essential in bloodstream form Trypanosoma brucei. Biochem J. 2006;396:287–95. doi: 10.1042/BJ20051825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zufferey R, Mamoun CB. Choline transport in Leishmania major promastigotes and its inhibition by choline and phosphocholine analogs. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2002;125:127–34. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(02)00220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lehane AM, Saliba KJ, Allen RJ, Kirk K. Choline uptake into the malaria parasite is energized by the membrane potential. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;320:311–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Mellors A, Samad A. The acquisition of lipids by African trypanosomes. Parasitol Today. 1989;5:239–44. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(89)90255-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Rifkin MR, Strobos CAM, Fairlamb AH. Specificity of ethanolamine transport and its further metabolism in Trypanosoma brucei. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16160–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.27.16160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Langford CK, Ewbank SA, Hanson SS, Ullman B, Landfear SM. Molecular characterization of two genes encoding members of the glucose transporter superfamily in the parasitic protozoan Leishmania donovani. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1992;55:51–64. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Drew ME, Langford CK, Klamo EM, Russell DG, Kavanaugh MP, Landfear SM. Functional expression of a myo-inositol/H+ symporter from Leishmania donovani. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5508–15. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Mongan TP, Ganapasam S, Hobbs SB, Seyfang A. Substrate specificity of the Leishmania donovani myo-inositol transporter: critical role of inositol C-2, C-3 and C-5 hydroxyl groups. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;135:133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Seyfang A, Landfear SM. Four conserved cytoplasmic sequence motifs are important for transport function of the Leishmania inositol/H(+) symporter. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5687–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Einicker-Lamas M, Almeida AC, Todorov AG, de Castro SL, Caruso-Neves C, Oliveira MM. Characterization of the myo-inositol transport system in Trypanosoma cruzi. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:2533–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Einicker-Lamas M, Nascimento MT, Masuda CA, Oliveira MM, Caruso-Neves C. Trypanosoma cruzi epimastigotes: regulation of myo-inositol transport by effectors of protein kinases A and C. Exp Parasitol. 2007;117:171–7. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lee SH, Stephens JL, Englund PT. A fatty-acid synthesis mechanism specialized for parasitism. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:287–97. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Tripodi KE, Buttigliero LV, Altabe SG, Uttaro AD. Functional characterization of front-end desaturases from trypanosomatids depicts the first polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthetic pathway from a parasitic protozoan. FEBS J. 2006;273:271–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Glick BS, Rothman JE. Possible role for fatty acyl-coenzyme A in intracellular protein transport. Nature. 1987;326:309–12. doi: 10.1038/326309a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Faergeman NJ, Knudsen J. Role of long-chain fatty acyl-CoA esters in the regulation of metabolism and in cell signalling. Biochem J. 1997;323:1–12. doi: 10.1042/bj3230001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Price HP, Güther ML, Ferguson MA, Smith DF. Myristoyl-CoA:protein N-myristoyltransferase depletion in trypanosomes causes avirulence and endocytic defects. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2010;169:55–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Frearson JA, Brand S, McElroy SP, et al. N-Myristoyltransferase inhibitors: new leads for the treatment of human African trypanosomiasis. Nature. 2010;464:728–32. doi: 10.1038/nature08893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Jiang DW, Werbovetz KA, Varadhachary A, Cole RN, Englund PT. Purification and identification of a fatty acyl-CoA synthetase from Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;135:149–52. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Hajra AK. Glycerolipid biosynthesis in peroxisomes (microbodies) Prog Lipid Res. 1995;34:343–64. doi: 10.1016/0163-7827(95)00013-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Opperdoes FR. Localization of the initial steps in alkoxyphospholipid biosynthesis in glycosomes (microbodies) of Trypanosoma brucei. FEBS Lett. 1984;169:35–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(84)80284-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Vertommen D, Van Roy J, Szikora JP, Rider MH, Michels PA, Opperdoes FR. Differential expression of glycosomal and mitochondrial proteins in the two major life-cycle stages of Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2008;158:189–201. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Zomer AW, Michels PA, Opperdoes FR. Molecular characterisation of Trypanosoma brucei alkyl dihydroxyacetone-phosphate synthase. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;104:55–66. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Futerman AH, Riezman H. The ins and outs of sphingolipid synthesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:312–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Cowart LA, Obeid LM. Yeast sphingolipids: recent developments in understanding biosynthesis, regulation, and function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:421–31. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Fridberg A, Olson CL, Nakayasu ES, Tyler KM, Almeida IC, Engman DM. Sphingolipid synthesis is necessary for kinetoplast segregation and cytokinesis in Trypanosoma brucei. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:522–35. doi: 10.1242/jcs.016741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Zhang K, Showalter M, Revollo J, Hsu FF, Turk J, Beverley SM. Sphingolipids are essential for differentiation but not growth in Leishmania. EMBO J. 2003;22:6016–26. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Zhang K, Pompey JM, Hsu FF, et al. Redirection of sphingolipid metabolism toward de novo synthesis of ethanolamine in Leishmania. EMBO J. 2007;26:1094–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Kennedy EP, Weiss SB. The function of cytidine coenzymes in the biosynthesis of phospholipides. J Biol Chem. 1956;222:193–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Vance JE, Vance DE. Phospholipid biosynthesis in mammalian cells. Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;82:113–28. doi: 10.1139/o03-073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Gibellini F, Hunter WN, Smith TK. Biochemical characterization of the initial steps of the Kennedy pathway in Trypanosoma brucei: the ethanolamine and choline kinases. Biochem J. 2008;415:135–44. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Signorell A, Gluenz E, Rettig J, et al. Perturbation of phosphatidylethanolamine synthesis affects mitochondrial morphology and cell-cycle progression in procyclic-form Trypanosoma brucei. Mol Microbiol. 2009;72:1068–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Kanfer J, Kennedy EP. Metabolism and function of bacterial lipids. II. Biosynthesis of phospholipids in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1964;239:1720–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Vance JE, Steenbergen R. Metabolism and functions of phosphatidylserine. Prog Lipid Res. 2005;44:207–34. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Bergo MO, Gavino BJ, Steenbergen R, et al. Defining the importance of phosphatidylserine synthase 2 in mice. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47701–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207734200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Arikketh D, Nelson R, Vance JE. Defining the importance of phosphatidylserine synthase-1 (PSS1): unexpected viability of PSS1-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:12888–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Steenbergen R, Nanowski TS, Beigneux A, Kulinski A, Young SG, Vance JE. Disruption of the phosphatidylserine decarboxylase gene in mice causes embryonic lethality and mitochondrial defects. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40032–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506510200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Voelker DR. Phosphatidylserine functions as the major precursor of phosphatidylethanolamine in cultured BHK-21 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1984;81:2669–73. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.9.2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Schuiki I, Daum G. Phosphatidylserine decarboxylases, key enzymes of lipid metabolism. IUBMB Life. 2009;61:151–62. doi: 10.1002/iub.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Li QX, Dowhan W. Structural characterization of Escherichia coli phosphatidylserine decarboxylase. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:11516–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Voelker DR. Phosphatidylserine decarboxylase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1348:236–44. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2760(97)00101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Yamaoka S, Miyaji M, Kitano T, Umehara H, Okazaki T. Expression cloning of a human cDNA restoring sphingomyelin synthesis and cell growth in sphingomyelin synthase-defective lymphoid cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:18688–93. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401205200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Huitema K, van den Dikkenberg J, Brouwers JF, Holthuis JC. Identification of a family of animal sphingomyelin synthases. EMBO J. 2004;23:33–44. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Tafesse FG, Huitema K, Hermansson M, et al. Both sphingomyelin synthases SMS1 and SMS2 are required for sphingomyelin homeostasis and growth in human HeLa cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:17537–47. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Levine TP, Wiggins CA, Munro S. Inositol phosphorylceramide synthase is located in the Golgi apparatus of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:2267–81. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.7.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Malgat M, Maurice A, Baraud J. Sphingomyelin and ceramide-phosphoethanolamine synthesis by microsomes and plasma membranes from rat liver and brain. J Lipid Res. 1986;27:251–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Maurice A, Malgat M. Phosphatidylethanolamine: ceramideethanolaminephosphotransferase activity in synaptic plasma membrane vesicles. Influence of some cations and phospholipid environment on transferase activity. Further proof of its location. Int J Biochem. 1993;25:1183–7. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(93)90597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Vacaru AM, Tafesse FG, Ternes P, et al. Sphingomyelin synthase-related protein SMSr controls ceramide homeostasis in the ER. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:1013–27. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200903152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Denny PW, Shams-Eldin H, Price HP, Smith DF, Schwarz RT. The protozoan inositol phosphorylceramide synthase: a novel drug target that defines a new class of sphingolipid synthase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:28200–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600796200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Mina JG, Pan SY, Wansadhipathi NK, et al. The Trypanosoma brucei sphingolipid synthase, an essential enzyme and drug target. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;168:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Kabani S, Fenn K, Ross A, et al. Genome-wide expression profiling of in vivo-derived bloodstream parasite stages and dynamic analysis of mRNA alterations during synchronous differentiation in Trypanosoma brucei. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:427. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Ternes P, Brouwers JF, van den Dikkenberg J, Holthuis JC. Sphingomyelin synthase SMS2 displays dual activity as ceramide phosphoethanolamine synthase. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:2270–7. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900230-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Zeidan YH, Hannun YA. The acid Sphingomyelinase/Ceramide pathway: biomedical significance and mechanisms of regulation. Curr Mol Med. 2009 doi: 10.2174/156652410791608225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Hannun YA, Obeid LM. Principles of bioactive lipid signalling: lessons from sphingolipids. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:139–50. doi: 10.1038/nrm2329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Zhang O, Wilson MC, Xu W, et al. Degradation of host sphingomyelin is essential for Leishmania virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000692. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Kopka J, Ludewig M, Muller-Rober B. Complementary DNAs encoding eukaryotic-type cytidine-5′-diphosphate-diacylglycerol synthases of two plant species. Plant Physiol. 1997;113:997–1002. doi: 10.1104/pp.113.3.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Lykidis A. Comparative genomics and evolution of eukaryotic phospholipid biosynthesis. Prog Lipid Res. 2007;46:171–99. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Inglis-Broadgate SL, Ocaka L, Banerjee R, et al. Isolation and characterization of murine Cds (CDP-diacylglycerol synthase) 1 and 2. Gene. 2005;356:19–31. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Volta M, Bulfone A, Gattuso C, et al. Identification and characterization of CDS2, a mammalian homolog of the Drosophila CDP-diacylglycerol synthase gene. Genomics. 1999;55:68–77. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]