Abstract

The reduced muscle mass and impaired muscle performance that defines sarcopenia in older individuals is associated with increased risk of physical limitation and a variety of chronic diseases. It may also contribute to clinical frailty.

A gradual erosion of quality of life (QoL) has been evidenced in these individuals, although much of this research has been done using generic QoL instruments, particularly the SF-36, which may not be ideal in older populations with significant comorbidities.

This review and report of an expert meeting, presents the current definitions of these geriatric syndromes (sarcopenia and frailty). It then briefly summarises QoL concepts and specificities in older populations, examines the relevant domains of QoL and what is known concerning QoL decline with these conditions. It calls for a clearer definition of the construct of disability and argues that a disease-specific QoL instrument for sarcopenia/frailty would be an asset for future research and discusses whether there are available and validated components that could be used to this end and whether the psychometric properties of these instruments are sufficiently tested. It calls also for an approach using utility weighting to provide some cost estimates and suggests that a time trade off study could be appropriate.

Keywords: Age, aging, muscle weakness, quality of life, malnutrition

Introduction

The term “sarcopenia” helped to spotlight this common muscle wasting condition when it was introduced in 1989 [1]. Since then, its definition has seen a number of modifications, moving from a bio-gerontological concept to a clinical condition, which focuses more on the pronounced muscular deficits that impact functional independence and the possible roles of extrinsic factors, such as lifestyle, nutrition and concomitant disease [2]. In 2010, two papers were published, and a third the following year, that proposed consensus diagnosis criteria [3-5]. Their conclusions were similar and should serve as a base for future research.

The term “frailty” is a well-recognised clinical syndrome, yet is defined by a number of different classification criteria [6,7]. A key element underlying most frailty definitions is sarcopenia (i.e. skeletal muscle loss) [7,8]. Frail older people are particularly vulnerable to external stressors and less able to resist the mental and physical challenges after a destabilizing event, although it is now clear that both frailty and sarcopenia carry a prognosis of (rapid) further functional decline with a higher risk of comorbidity and increasing disability (higher risks of falls, hospitalisation, institutionalisation and death) than in the older population as a whole [9-11]. Thus one of the major challenges of geriatric medicine is therefore to recognise these conditions as soon as possible and to halt (or slow) the downward spiral of increasing comorbidity and frailty [7,12].

That the quality of life declines in frailty is intuitively evident and there are good indications that this is also the case for sarcopenia. However in the absence of specific QoL tools and without a clear conceptual framework of QoL in these patients, an important element in the characterisation and follow-up of these conditions seems to be missing. Since comorbidities are very frequent in both, attributing QoL to the core condition remains a challenge.

We describe herein the conclusions that were made during a discussion session in November 2012 on a possible QoL assessment in sarcopenia and frailty.

Definitions

Sarcopenia

The 3 consensus papers, which have published a definition of sarcopenia, were written under the auspices of, respectively: the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) [3], the ESPEN Special Interest Groups [4] and the International Working Group on Sarcopenia (IWGS) [5]. The consensus definitions were:

The presence of low skeletal muscle mass and either low muscle strength (e.g. hand grip) or low muscle performance (e.g. walking speed or muscle power) and when all three conditions are present, then severe sarcopenia may be diagnosed (EWGSOP).

The presence of low skeletal muscle mass and low muscle strength (which they advised could be assessed by walking speed) (ESPEN SIG).

The presence of low skeletal muscle mass and low muscle function (which they advised could be assessed by walking speed) and “that [sarcopenia] is associated with muscle mass loss alone or in conjunction with increased fat mass” (IWGS).

Thus the EWGSOP consensus, by separating muscle strength and muscle performance, allows for a slightly broader definition of the diagnosis and provides for a classification of a severe condition. A fairly long-running debate in this field is whether or not to apply the term “dynapenia” to the age-related loss of muscle strength and limiting sarcopenia to age-related loss of muscle mass [13]. Although the two processes may occur simultaneously in some individuals, they do not necessarily overlap and may be the result of different pathophysiology processes. The EWGSOP consensus authors however seem to be of the opinion that since sarcopenia is already a fairly well-known term, the introduction of another may lead to confusion [3].

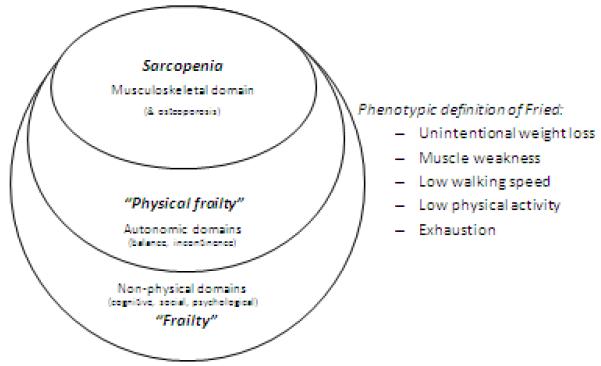

The EWGSOP consensus also discussed the frailty concept and its overlap with sarcopenia. It recognised, as others have done [6,14], that frailty is characterised by deficits in multiple organ systems, i.e. psychological, cognitive, and/or social functioning, as well as physical limitations.

Frailty

While a theoretical definition of frailty could be the lack of functional reserve [15], no single operational definition has met with widespread acceptance and consensus meetings have yet to offer a solution [6,16]. Widely used operational (phenotypic) definitions are those suggested by Rockwood and colleagues in 1999 [17] and Fried and colleagues in 2001 [18]. The Rockwood definition, with 4 classes of disability, is considered by some experts in the field to be flawed by using a combination of frailty and disability and prefer to consider frailty as a risk factor for disability. The Fried definition cites the accumulation of deficits in 5 domains: unintended weight loss; muscle weakness (grip strength); self-reported exhaustion; slow walking speed (i.e. low gait speed); and low physical activity. A total of 2 deficits indicate a pre-frail condition and 3 or more deficits indicate frailty. More recent frailty scales have been proposed and some of these use continuous variables [19] or extend the scale with social and psychological measures [20-22]. The majority of definitions of frailty include loss of skeletal muscle as a component [8] and it is usually the musculoskeletal component of frailty as the phenotype that most frequently comes to the attention of healthcare professionals [6].

Sarcopenic obesity

The term sarcopenic obesity has been used to describe a subgroup of sarcopenic individuals with a high percentage of body fat. This subgroup has been recognised for some time as having a particularly high risk of adverse outcomes [23]. The condition is characterised, in addition to low lean muscle mass or low muscle performance, by excess energy intake, low physical activity, low-grade inflammation and insulin resistance [3,23].

Cachexia

This describes a severe wasting condition that is seen in chronic disease states such as cancer, congestive cardiomyopathy and end-stage renal disease. This was the subject of the ESPEN SIG consensus paper [4] and the definitions presented therein and previously [24], were endorsed by the EWGSOP. Cachexia is associated with inflammation and frequently with insulin resistance and anorexia. It may therefore be viewed as a complex metabolic syndrome invoked by the underlying illness. While most cachectic individuals also have sarcopenia; sarcopenic individuals, unless they have an increased inflammatory status and/or impaired carbohydrate, protein or lipid metabolism, are not considered as having cachexia.

Diagnostic criteria

Sarcopenia

The consensus papers concurred on the use of a T-score-based cut-off for lean (skeletal) muscle mass (appendicular lean mass; aLM) divided by height squared with a threshold of ≥ 2 standard deviations below the mean measured in young adults in a reference population. The EWGSOP suggested that muscle mass could be determined by computed tomography (CT scan) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; the gold standards) or dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA: the preferred alternative); IWGS pronounced for DXA; and ESPEN SIG gave no indication. Using the Rosetta study for the reference population [25] and using DXA for mass measurement, this T-score method gives values of ≤ 7.3kg/m2 for men and ≤ 5.5 kg/m2 for women.

It seems relevant however that aLM is also indexed for body fat mass (e.g. on the residuals from a regression analysis). This approach, used in the Health Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) study [26], was found to give a better identification of overweight or obese sarcopenic individuals and better associations with impaired lower extremity function. In other recent research investigations, which have used DXA to measure body tissue mass, applied a definition of obesity as body fat mass greater than the 60th percentile of a ‘normal’ population (typically: 28% body fat in men and 40% in women) [27,28].

The second criterion for sarcopenia in all 3 consensus papers was (usual) gait speed. The most favoured assessment seems to be on a 4 metre course, with a reference speed of either 0.8 m/s (suggested by EWGSOP and ESPEN SIG) or 1 m/s (IWGS) where the inferior values are indicative of sarcopenia. Further research will be required to more closely define this threshold with perhaps a small difference between genders. In a recent cross-sectional study [29] of 3,145 older adults in England (aged ≥65 years; 46% men) it was found the mean walking speed was 0.9 m/s in men and 0.8 m/s in women. The conclusion of this study, which examined walking speed in the context of traffic collisions and socio-economic factors, was that the national standard of normal walking speed for pedestrian crossings of 1.2 m/s was too high for this segment of the population.

A third criterion (suggested by EWGSOP) was low muscle strength which, it was suggested, can be most conveniently measured using a hand-grip dynamometer (with a certain preference for the Jamar model).

Table 1 gives the cut-offs for the more widely used and well validated criteria for lean muscle mass determined by DXA; muscle strength; and muscle performance by gait speed.

Table 1. Frequently used cut-off values for a selection of diagnostic criteria for sarcopenia.

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| Skeletal muscle mass | ||

| SMI by DXA [25] | < 7.26 kg/m2 | < 5.45 kg/m2 |

| Muscle strength | ||

| Handgrip strength [30] | < 30 kg | < 20 kg |

| Muscle performance | ||

| Gait speed on 4m course [31] | < 1.0 m/s | |

| SPPB [32] | ≤ 8 | |

DXA: Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry; SMI: Skeletal Muscle Mass index where appendicular skeletal muscle mass is standardised using the square of the individuals’ height; m: meter; s: second; kg: kilogram; SPPB: Short Physical Performance Battery, summation of scores for balance, gait speed and chair stand (max score = 12)

Frailty

Using the definition of frailty proposed by Fried, there remains heterogeneity of assessment methods and of the cut-off values for a positive diagnosis. Table 2 shows a small sample of trials that have analysed their respective populations according to these criteria; the reference study by Fried appears in the first column. It may be seen that a number of more or less subtle differences are evident, from the methods of correction of parameters for body size or gender, to the use of subjective reports in the place of objective measurements. In the examples shown, the percentages of frail and pre-frail individuals show some similarities despite the methodological differences (between 4 and 11% for frail and 37-55% for pre-frail). Others have found however quite heterogeneous results, when different frailty criteria are applied, with the prevalence in a sample population ranging from 33% to 88% [33].

TABLE 2. Components of frailty and a selection of frequently used diagnostic criteria.

| Components of Frailty |

Cardiovascular Health Study (2001) [18] n=1741 |

InChianti study (2006) [34] n=827 |

Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement (SHARE, 2010) [35] n=18 227 |

Women’s Health and Aging Studies (2010) [36] n=786 |

TROPOS and SOTI (2011) [37] n=5082 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Unintentional

weight loss |

≥5% loss of body weight in prior year |

> 4.5kg self-reported unintentional weight loss in previous year |

A negative response to the question “what has your appetite been like?” |

≥10% weight loss since age 60 until exam |

≥5% loss of body weight in prior year | ||||||

|

| |||||||||||

|

Self-reported

exhaustion |

A positive response to either (CES-D) statement: i) I felt that everything I did was an effort ii) I could not get going |

A positive response to either (CES-D) statement: i) I felt that everything I did was an effort ii) I could not get going |

A positive response to the statement: i) In the last month, I have too little energy to do things I want to do |

A report of any of: i) low usual energy level (≤3, range 0-10), ii) felt unusually tired in last month, or iii) felt unusually weak in the past month |

A response of “most or all the time” to either (SF-36 – vitality) question: i) Did you feel worn out? ii) Did you feel tired ? |

||||||

|

| |||||||||||

|

Low physical

activity |

270 on activity scale (18 items) |

Self-reported physical activity during the home interview. |

A response of “one or three times a month ” to the question: i) how often do you engage in activities that require a low or moderate level of energy? |

90 on activity scale (6 items) |

A positive response to either of the statements: i) I do no physical activity ii) I do no more than 1 or 2 walks per week |

||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Slow walking speed | Walking 4.57 m: (corrected for height) |

Walking 4 m: (lowest sex-specific and height-specific quintile) |

A positive response to the question: i) because of your health problem do you have difficulty walking ? |

Walking 4 m: (corrected for height) |

A response of “;Yes, limited a lot ” to (SF-36 – physical functioning) question: - Are you limited in walking one block ? |

||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Muscle weakness | Grip strength (corrected for BMI range) |

Grip strength (lowest sex-specific quintile) |

Grip strength (corrected for BMI range) |

Grip strength (corrected for BMI range) |

A response of “Yes, limited a lot ” to (SF-36 – physical functioning) question: - Are you limited in climbing one flight of stairs? |

||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| 50-64yr | +65yr | ||||||||||

| Result | Robust | 33% | Robust | 56% | Robust | 59% | 41% | Robust | 45% | Robust | 46% |

| Pre-frail | 55% | Pre-frail | 38% | Pre-frail | 37% | 42% | Pre-frail | 44% | Pre-frail | 49% | |

| Frail | 12% | Frail | 7% | Frail | 4% | 17% | Frail | 11% | Frail | 5% | |

Note: the criteria in the first column, the Cardiovascular Health Study (2001,) are those proposed by Fried and colleagues

The need for simplicity and consistency in measurement and terminology

The EWGSOP consensus paper interestingly provides details and suggested threshold values for a number of other measurement techniques, which do provide valid performance assessments. Some are more widely used, such as Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) and the “timed get-up-and-go” (TGUG) protocol, others less so. Here, and elsewhere in the literature, it can be seen that various methodological debates exist, such as whether muscle power as a measure provides greater prognostic value than muscle strength; or is grip strength better assessed on the dominant hand or non-dominant hand and should the recorded value be the best of 3 tries, or meaned or summed [38,39].

From the premise that one should proceed from simpler theories only when simplicity can be traded for greater explanatory power, it might be argued that with the application of the criteria and threshold values from the consensus statements, it would be judicious to keep the methodologies and assumptions as simple as possible so as to test prognostic theories.

Efforts must also be made for the consistency of terminology and clarity of definitions. This is required for the terminology associated with muscle contraction, e.g. “performance”, “function”, “strength”, “quality”, “endurance” etc., as well as in the terminology for disability and QoL concepts. A laudable plea for a common language for disablement research was made previously by Jette [40], who recommended of using the language and concepts of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) framework of the World Health Organisation (WHO) [41].

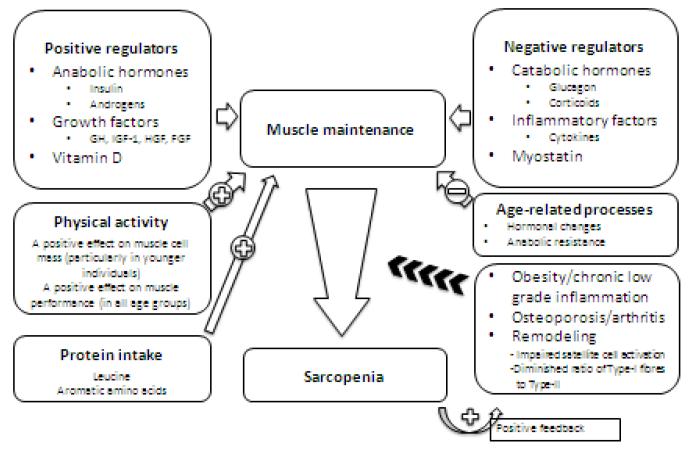

Etiology

The underlying causes of sarcopenia and frailty are multifactorial. Although the progressive loss of muscle mass with aging has been recognised for a long time, it is only with more recent techniques and longitudinal prospective studies that the age-related changes in body composition have begun to be described [42-45]. The main processes involved in the maintenance of muscle tissue and the decline towards sarcopenia are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The control of muscle maintenance and the decline to sarcopenia

It is assumed that the muscle is in its usual environment of biomechanical attachment, neural input and energy supply.

Muscle, given its usual environment of biomechanical attachment, neural inputs and energy supply, can be considered as having a number of positive and negative regulators that influence its maintenance and “health” [46,47]. Thus muscle tissue is negatively impacted when the influence of positive regulators is diminished (e.g. low vitamin D status)[48,49] and when negative regulators are augmented (e.g. inflammatory conditions)[50]. Muscle mass is increased by physical activity and protein intake [51]. Muscle strength is increased (in all age groups) by physical activity [52].

The process of normal aging, with the changes in hormonal status (e.g. following menopause or andropause) [53,54], with the onset of anabolic resistance [55], and a more sedentary lifestyle, leads to loss of muscle mass and muscle strength [44,56]. With the concerted influence of other factors, such as obesity and chronic low-grade inflammation [57], muscle loss is enhanced. This is then further exacerbated by feedback systems that are initiated in the muscle tissue. An increase in intramuscular fat at this stage is associated with an accelerated decline in muscle quality (strength per unit of mass) [58]. Another factor to be taken into consideration in older persons is the negative impact on muscle tissue of poly-medication.

Treatments for sarcopenia and frailty

The risk factors for sarcopenia, in addition to low physical activity and poor nutrition, include chronic inflammation and obesity and thus are to some extent modifiable.

The first step to be taken for a person with sarcopenia or clinical frailty is to ensure that he/she is receiving a correct and sufficient nutrition [59]. An insufficient diet is quite frequent in older people [55,60] in a recent study of hip fracture patients admitted to hospitals in Sydney, 58% were found to be undernourished and 55% had a vitamin D deficiency [61]. Nutritional assessment may be made by one of a variety of questionnaires including the Nutritional Risk Screening (NRS-2000), the Simplified Nutritional Appetite Questionnaire (SNAQ), the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST), the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) and the SNAQ65+ (the 2 latter instruments have been tested in or developed for older persons [62,63]).

It is also important that the sarcopenic/frail individual should receive minimal amount of physical activity and if possible resistance training [52,64,65]. Pharmacological treatments remain, for the moment, as research projects [66]. The positive effect of inhibiting angiotensin II converting enzyme is currently undergoing clinical trials as are blockers of chronic inflammation. Trials of hormone treatments have either shown complications or no proof of efficacy, while trials of myostatin inhibitors are ongoing.

Functional consequences associated with sarcopenia and frailty

Low muscle performance or strength has prognostic implications

In the 1990’s a number of research studies in healthy older populations began observing that low muscle performance was associated with a higher risk of future disability. For example, in a key prospective study conducted by Guralnik and colleagues in >70-year-old community-dwelling individuals [67], participants were assessed by the SPPB at baseline and then followed-up by interview four years later. Those with lower base-line scores were associated with higher levels of disability (activity- and mobility-related) at follow-up. After adjustment for age, sex, and the presence of chronic disease, those with the lowest SPPB scores (from 4 to 6) were 4 times more likely to have disability at follow-up than those with the highest scores (10 to 12). This was later confirmed in a large scale multi-cohort study which also noted that gait speed alone had almost the same prognostic ability as the complete SPPB [32].

Early in the following decade, the landmark study known as the Health ABC trial clearly demonstrated that the loss in muscle strength over time was greater than the loss of muscle mass (particularly the loss of fast-twitch muscle fibre). This study, which followed 1880 older adults over 3 years, found annualised rates of decline in leg strength of 3.4% in men and 2.6% in women, whereas the rates of loss of leg lean mass were only about 1% per year [68].

Subsequent mobility limitations of those enrolled in the Health ABC study were developed by 22.3% of men and by 31.8% of women. This loss in mobility was associated with lower muscle mass, lower muscle strength and greater muscle tissue attenuation (a measure of fat infiltration), when analysed using a Cox’s proportional hazards model to compare the lowest quartiles to the highest in each criterion and adjusting for demographic, lifestyle, and health factors. But, when all three muscle criteria were included in single regression model, only lower muscle strength and greater muscle tissue attenuation were independently associated with incident mobility limitation (p < 0.05) [69].

The association of body fat and physical limitation was shown at about the same period in the EPIDOS (EPIDemiologie de l’OSteoporose) study, a cross-sectional investigation of older women with osteoporosis [28]. The study showed that in obese women, low muscle mass was associated with an increased risk of physical limitation. But, in non-obese women this association was not apparent. Thus it would appear that the low muscle strength and the poor muscle quality (i.e. increasing fat infiltration) are strong indicators of functional decline, whereas low muscle mass is not.

Absolute muscle strength is a prognostic indicator of functional decline

Remarkably, it would also appear that absolute muscle strength at a point in time is a good long-term indicator of functional outcome. In a 25-year prospective cohort study in healthy men aged 45-68 years old, maximal hand grip strength was assessed at baseline [70]. Of the 6089 individuals enrolled, 2259 died over the follow-up period and 3218 survivors (53%) participated in the follow-up disability assessment 25 years later. Those with the lowest tertile on grip strength at study entry were associated with a very low walking speed (< 0.4 m/s) (odds ratio [OR]= 2.87) and a 2-fold greater risk of self-care disability. These associations persisted after adjustment for multiple potential confounders including chronic conditions.

This result was recently corroborated by the Invecchiare in Chianti (InChianti) study [71] which measured grip strength, knee extension strength, and lower extremity power at baseline and mobility function (gait speed and self-reported mobility disability) in 934 adults aged ≥65 years. At the end of 3 years follow-up, men who had low leg power (<105 W) at baseline were associated with 9-fold increase in mobility disability; low knee extension strength (<19.2 kg) and grip strength (<39.0 kg) were associated with relevant reductions in gait speed. While these associations were particularly strong in men, they showed similar trends in women.

In another cross-sectional study of 2,208 subjects (aged 55 and older), low handgrip strength and walking limitation (<1.2 m/s or difficulty walking 500m) were correlated with increased body fat [72]. The researchers found that the prevalence of walking limitation was much higher in persons who simultaneously had high body fat percentage and low handgrip strength (61%) than in those with a combination of low body fat percentage and high handgrip strength (7%).

Obesity increases the risk of functional decline in frail older persons

As mentioned above, there appears to be a particularly high risk of functional decline when frailty is concomitant with obesity.

In the cross-sectional Women’s Health and Aging Studies I & II [73], 599 community-dwelling women (aged 70 to 79, BMI > 18.5 kg/m2) were classified for frailty status (Fried criteria). The multinomial regression model returned a significant association for obesity and frailty (OR =3.52, 95% confidence interval (CI) =1.34-9.13), as well as obesity and pre-frailty (OR =2.23, 95% CI =1.29-3.84).

Co-morbidities associated with sarcopenia and frailty: Impact on quality of life

It seems clear therefore, that sarcopenia and frailty increase the risk of physical limitation and subsequent disability, but recent research also shows that these conditions increase the risk of comorbid conditions.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of published (prospective) studies that had assessed physical capability (using measures such as grip strength, walking speed, chair rises, or standing balance) and subsequent outcome (including fracture, cognition, cardiovascular disease, hospitalisation and institutionalisation), Cooper and colleagues found that those who demonstrated lower physical capability had a higher risk of negative outcomes [74]. To be included in the analysis, all papers had to identify in their respective populations the possible confounders of the association to be studied and a description of the methods used to control for them. A few of the results in the 4 main categories are presented below:

Fracture risk: in 7 out of 9 study samples, researchers reported that lower grip strength was associated with a higher subsequent fracture risk and in 4 out of 5 study samples that low walking speed was associated with a higher fracture risk.

Cognitive function: In 3 study samples that examined grip strength and cognitive function, all found that low strength was associated with a higher subsequent risk of cognitive decline, development of Alzheimer’s disease or other forms of dementia. (Also in this context, it is interesting to note that gait analysis in older people is indicative of their cognitive profile [75]).

Cardiovascular outcomes: In 3 study samples that examined grip strength and cardiovascular outcomes, one found that low strength was associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease over the subsequent 24 years, one found that low strength was associated with higher levels of fasting insulin and the third (in women) found no association between strength and risk of stroke.

Hospitalisation: in 2 out of 3 study samples low, walking speed was found to be associated with an increased risk of hospitalisation. Additional data corroborate the association between muscle strength and hospitalisation outcomes. In a small prospective cohort study of older patients (n = 120, age range 75-101 years), Kerr and colleagues investigated the association between grip strength and hospitalisation outcome. Using a Cox proportional hazards model they found that higher grip strength on admission was associated with increased likelihood of discharge to usual residence. A grip strength of greater than 18 kg for women and 31 kg for men was associated with a 25% increase in the likelihood of return home [76]. Others have found that low muscle strength or performance (but not muscle mass) were associated with the risk of hospitalisation [77].

Low physical capability is also associated with additional comorbidities such as diabetes and risk of falling as well as increased risk of death:

Diabetic men (previously or newly diagnosed), in the Hertfordshire cohort [78], had significantly weaker muscle strength and higher odds of impaired physical function that those without diabetes. This relationship held up also for individuals with impaired glucose tolerance and right across the normal range of glucose concentration. In women, the effect sizes were smaller and less consistent, perhaps reflecting sex differences in body composition. Subsequently, it has been shown that diabetes is associated with an accelerated loss of muscle mass and muscle strength [79,80].

The risk of falls is greatest in individuals with low muscle strength. The guideline published by learned geriatric societies for the prevention of falls in older persons [81] put muscle weakness as the strongest risk factor, more than a history of falls, or gait or balance deficits. The older men enrolled in the MrOS study (n = 10,998) who had a handgrip strength score less than 2 standard deviations below the reference mean had a 2.4 fold higher risk of recurrent falls (95% CI 1.7-3.4) than older men of ‘normal’ strength [82].

Mortality risk, after adjustment for demographics, health behaviours, comorbidity and CV disease risk factors is higher in older people with low physical capability. As part of the Health ABC Study, 3075 community-dwelling adults (aged 70 to 79 years, 52% women) were asked to perform a 400 m walk test at the baseline and the results were correlated with outcome after 5 years (total mortality, incident cardiovascular disease, incident mobility limitation, and mobility disability) [83]. Among those able to complete the test, each additional minute of performance time was associated with an adjusted HR of 1.29 (95% CI, 1.12-1.48) for mortality, after adjustment (statistically significant worsening was also seen for the other outcome measures). The crude mortality rate in the poorest quartile for the walk test was 39.9 per 1000 person-years versus 14.2 per 1000 in the best quartile (adjusted HR, 3.23; 95% CI, 2.11-4.94; p<0.001).

Similar correlations have been made between frailty and comorbidities [84]. Thus, while it seems clear that both of these geriatric conditions increase the risk comorbidity, it is also evident that a number of comorbid conditions increase the risk of sarcopenia and/or frailty. In consequence, the patient enters into a vicious circle of further functional decline.

The QoL instruments used in older populations and relevant disease states

Why study QoL?

Health-related QoL (HR-QoL) has been defined as “a subjective measure which is evaluable over time and having a focus on the qualitative dimension of functioning” i.e. an assessment of functional status, physical, mental, and social subjective dimensions that might provide evidence over time of the impact on the individual in terms of health status, satisfaction and contentment in everyday life. These assessments are important for governments and healthcare providers to understand the needs and preoccupations of important segments of the population and allocate resources and define healthcare reforms and initiatives accordingly. Increasingly their concern focuses on robustness of outcomes in relation to both the inputs and processes of healthcare delivery. Since the interest is in subjective measures, then the instruments are frequently referred to as patient-reported outcomes (PROs): i.e. any report of the patients’ health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patients’ response by a clinician or anyone else.

For complete assessment of the benefits of an intervention it is essential to provide evidence of the impact on the patient in terms of health status and health related quality of life. Such an approach is also essential in a comprehensive global assessment of older people [85] and should be taken into account in guided treatment decisions of any chronic illness.

Even in the assessment of physical functioning, the evidence suggests that self-reported and performance-based may provide different and complementary information. This was the conclusion of a recent study in hip fracture patients [86], in which the responsiveness of self-reported measures (5-point Likert scales and EuroQoL 5D) were compared with performance-based measures (including knee-extensor strength, the PPME [physical performance and mobility examination], chair-rise test, maximum balance range, etc.). The researchers found that the correlations between the two approaches were only small to medium. Walking speed and chair-rise test were amongst the most responsive performance-based measures, the self-reported measures often indicated greater levels of disability.

There are numerous different concepts of QoL, ranging from psychological perspectives, “utilities” and the trade-offs that individuals make, to the reintegration to normal living [87]. This fact and the implicit value of having a subjective measure of welfare have resulted in a multitude of QoL instruments [88]. Two distinctive classes of instruments exist to assess HR-QoL. Generic instruments are designed to be applicable across a wide range of populations, diseases, and interventions, whereas specific instruments are relevant to particular subpopulations or illnesses. While this review is not the place to discuss all the aspects of the QoL assessments, it seems pertinent to recall a few salient points.

Concepts and specificities

It is usually considered that there are three broad dimensions in the HR-QoL construct: physical / occupational function, social health / integration, and mental health / psychological state, while the non-health-related QoL, includes financial and economic aspects, spiritual and political aspects, and environmental factors [87].

For any study of QoL, it is important that a conceptual framework of the QoL dimensions and subordinate domains be made [89], describing how the assessment scales relate to the studied population and to the proposed risk factor(s) of interest. This is a step that is unfortunately omitted from many research publications, hindering their comparative evaluation [90,91]. QoL instruments should also clearly define the recall period for which patients/individuals are meant to refer. While a number of questionnaires do preface the question blocks by “in the last week” or “in the last month”, this is not systematic and the recall periods vary considerably between instruments.

A subtle aspect of QoL studies in patients with chronic disease (or for that matter following a serious illness or intervention) is that of “response shift” or adaptation, i.e. a change in perspective of QoL accounting for actual physical condition [92]. Studies have found that older people tended to compare themselves with their peers, and that the mildly frail identified themselves with those worse off and the most frail identified themselves with those doing better [85,93]. A potential solution to this might be the use of a visual analog scale relating actual well-being with the best and worst periods in the subject’s life [94,95] i.e. a single question which may anchor subsequent questionnaires.

The length of questionnaires is highly variable and there is clearly a trade-off between short-forms (with acceptable imprecision and high completion rates) and long-forms (with greater precision and lower completion rates). Thus, there is a risk is that specific QoL instruments become long and onerous to complete [96]. A contemporary approach to this response burden is computer-assisted adaptive testing (CAT) which, in an example of a questionnaire assessing disability outcomes, reduced the completion time from 20-30 minutes to 3.56 minutes without loss of measurement accuracy, precision or reliability [96].

In pharmacoeconomic studies, the utilities (preferences) for a health condition need to be established, which are then usually used to calculate QALYs (quality-adjusted life years). Frequently this is done using a validated QoL questionnaire (such as the EQ-5D), but in any new area, the assumptions should be verified using another method. In the study by Salkeld and colleagues [97] in hip fracture patients, this was done for example, using the time trade-off technique. Patients (194 women aged 75-98 years old) were asked to rank different health states (“full health”, “fear of falling” “good hip fracture” and “bad hip fracture”) and to trade off shorter periods of full health with longer periods of impaired health. The results showed that the women placed very high marginal value on their health and that 80% would rather be dead than experience the loss of independence and the poor QoL that results for a bad hip fracture and subsequent admission to a nursing home.

Generic QoL instruments

Generic QoL questionnaires are widely used since they allow the comparison of the burden of disease between different disease states. They carry risk however of being relatively insensitive to any particular pathological condition and therefore changes over time or treatment may be lost to background (low signal to noise).

“Broad-use” generic QoL instruments (particularly the SF-36) are popular in the study of older populations and several comparative reviews are available [98,99]. It has been argued however, that the assessment of QoL in older persons should use QoL instruments that are adapted to the specificities of the age group [85,100,101] and also differentiate between people dwelling in the community versus those who are institutionalised [102]. These types of instruments have been reviewed previously [100,103,104].

Table 3 presents a few of the more widely reported “broad-use” generic QoL instruments and some that have been designed for older populations.

TABLE 3. Generic QoL instruments.

| Name | Number of questions |

Domains (number of questions) |

|---|---|---|

|

SF-36 MOS 36-item Short Form Health Survey [105] |

36 | 8 domains: General health (GH) (5), physical functioning (PF) (10), role limitation-physical (RP) (4), mental health (MH) (5), role limitation- emotional (RE) (3), social functioning (SF) (2), bodily pain (BP) (2), vitality (V) (4) |

|

EuroQol EQ-5D European QoL Questionnaire [106] |

5 | 5 domains: Anxiety/depression (1), mobility (1), pain/discomfort (1), self- care (1), usual activities (1) |

|

Nottingham Health Profile (NHP) [107] |

38 | 6 domains: Bodily pain (BP) (8), emotional reactions (ER) (9), energy (E) (3), physical mobility (PM) (8), sleep (S) (5), social isolation (SI) (5) |

| Instruments for older persons | ||

|

OPQOL-brief Older People’s Quality of Life questionnaire [100] |

35 | 8 domains: Life overall (4), health (4), social relationships and participation (5), independence, control over life and freedom (4), home and neighbourhood (4), psychological and emotional well-being (4), financial circumstances (4), leisure, activities and religion (6) |

| CASP-19 [108] | 19 | 4 domains: Control, autonomy, self-realisation and pleasure |

|

PGC-MAI Philadelphia Geriatrics Center Multilevel Assessment Instrument [109] |

147 (+ mid-length [68] + short [24]) |

6 domains: ADL (16), cognition (10), perceived environment (25), personal adjustment (12), physical health (49), social interaction (17), time use (18) |

|

PWB Perceived Well-Being Scale [109] |

14 | 2 domains: Psychological wellbeing (6), physical wellbeing (8) |

|

ACSA Anamnestic Comparative Self- assessment Scale [94] |

14 | 1 domain: subjective well-being - the ACSA asks the patient to remember the best and worst periods of their life experience (assigned +5 and −5, respectively) then to rate their current life satisfaction (over period). |

| LEIPAD [110] | 49 | 7 domains: Cognitive function (5), depression/anxiety (4), life satisfaction (6), physical function (5), self-care (6), sexual function (2), social function (3) + other moderator scales (18) |

| WHOQoL-Old [111] | 24 | 6 domains: Sensory abilities (4), autonomy (4), past, present and future activities (4), social participation (4), death and dying (4), intimacy (4) |

ADL: Activities of daily living; IADL: instrumental activities of daily living

The SF-36

Given its widespread use, it is perhaps pertinent to discuss briefly the characteristics of the SF-36. This instrument was designed to satisfy minimum psychometric standards in a very broad range of individuals (14 years old or more) with the aim of surveying a general population for health policy objectives [105]. The 8 domains (or health concepts) were selected from 40 that were included in the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS), and considered to be the most pertinent in most patients; these domains being physical functioning, physical roles, bodily pain, general health mental health, emotional roles, social functioning, and vitality. While some of the scales of the SF-36 have been shown to have 10-20% less precision than the long-form MOS measures they were constructed to represent, this weakness is offset by the fact that the SF-36 has a 5-10 fold lower response burden than the long-form questionnaire [112]. It is recognised that the SF-36 functions best as a “generic core” to compare populations across studies and that it should be supplemented with disease specific instruments if it is to comprise a principal health outcome measure [112]. The SF-36 has been found to be a simple and effective measure of mobility-disability in epidemiological studies [113], although a substantial ceiling-effect for some domains has been noted [114].

Specific instruments

A large number of disease-specific QoL instruments exist, but none as yet specific for sarcopenia or frailty. QoL instruments do however exist for certain other diseases which may be of interest in defining impacted domains in sarcopenia, either because they have a relatively high prevalence in older people, such as osteoporosis and stable angina, or because they have a significant effect on physical functioning such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and Parkinson’s disease.

Osteoporosis

Some of the QoL instruments that have been developed for studies in osteoporosis are presented in Table 4. Three are self-administered questionnaires and 3 are given by an interviewer. The number of domains assessed varies from 2 to 7 and the number of questions from 23 to 84.

TABLE 4. QoL instruments for osteoporosis.

| Name | Administration | Number of questions |

Domains (questions) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualeffo-41 [115] | Self-administration | 41 Short version: 31 |

7 domains: Pain (5), physical function- ADL (4), physical function-IADL (5), physical function-mobility (8), social function (7), general health perception (3), mental function (9) |

|

QUALIOST (Questionnaire QoL in Osteoporosis) [116] |

Self-administration | 23 | 2 domains: physical function, emotional status |

|

OPAQ (Osteoporosis Assessment Questionnaire) [117] |

Self-administration | Version 1: 84 Version 2: 60 Version 3: 34 |

4 domains: physical function, emotional status, symptoms, social interaction |

|

OQLQ (Osteoporosis QoL Questionnaire) [118] |

Interviewer | 30 Short version: 10 |

3 domains: physical function, emotional function, ADL |

|

OFDQ (Osteoporosis Functional Disability Questionnaire) [119] |

Interviewer | 69 | 6 domains: general health, back pain, confidence, ADL, socialization, depression |

|

OPTQoL (Osteoporosis-targeted QoL Questionnaire) [120] |

Interviewer | 33 | 3 domains: physical activity, adaptations, fears |

Heart Disease

The impact of chronic cardiovascular disease on QoL has been investigated in numerous studies and several specific instruments are available [88]. Studies of stable angina are of potential interest since the patients are frequently older, community-dwelling women. Of note are the HeartQoL questionnaire and the Seattle Angina Questionnaire. Patients with heart failure are usually more severe and these specific instruments (e.g. Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire and the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire) of less interest.

Muscle Disease

The Individualised Neuromuscular QoL instrument (INQOL) is a 45-item questionnaire designed for patients with muscle diseases that examines the impact of symptoms (weakness, myotonia, pain, and fatigue), the effects they have on aspects of daily life, and the positive and negative effects of treatment [121].

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

The impact of this disease on QoL has been examined in several studies and a pertinent review is that by Gimeno-Santos and colleagues [90].

Studies of QoL assessment in sarcopenic or frail populations

Studies that assessed QoL in populations of older community-dwelling individuals with a diagnosis of either sarcopenia or frailty are presented in Table 5. Of the 8 studies identified, 5 used the SF-36; the other instruments were the OPQOL, the WHOQO-Bref and the QLSI (Quality of Life Systemic Inventory Questionnaire). In 3 of the studies using the SF-36 (in frail patients), the mean physical and mental summary values were presented and these show notable heterogeneity. Also apparent from these 3 studies is that the standard deviations for the means in the robust, pre-frail and frail groups equal or exceed the differences between the groups. In this respect, the OPQOL scores appear to show a more satisfactory result.

TABLE 5. Studies of community-dwelling populations having a diagnosis of sarcopenia or frailty and QoL assessment.

| Population | Diagnosis of Sarcopenia/Frailty | QOL | Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sayer et al. (2006) [114] England |

N = 2,987; aged 59–73 years, mean age = 66.6 years; 47% of the cohort were women. |

Sarcopenia: grip strength (mean values were: 44.0 ± 7.5kg for men and 26.5 ± 5.8kg for women) |

SF-36 |

Men Women |

Decreased grip strength correlated with: poor PH and GH poor PH, GH,RP, VT and BP |

||

|

Masel et al. (2009) [122] USA (Hispanic population) |

N = 1008; aged 74 years and older, mean age = 82.3 ± 4.3 years; 63% women; 40% overweight, 26% obese. |

Frailty (Fried criteria) | SF-36 |

Robust Pre-frail Frail |

Pop 26% 54% 20% |

QOL Physical 44 ± 10 36 ± 12 29 ± 10 |

QOL Mental (subscores) 58 ± 6 54 ± 11 47 ± 13 |

|

Bilotta et al. (2010) [93] Italy |

N = 239; mean age = 81.5 ± 6.3 years; 67% women; 4.3 chronic diseases; 5.4 drugs/day; 26% had depression/dementia. |

Frailty using the 3 criteria from Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (weight loss, exhaustion & 5 times chair rise exercise) |

OPQOL |

Robust Pre-frail Frail |

Pop 30% 37% 33% |

OPQOL total score 126 ± 13 116 ± 14 107 ± 13 |

|

|

Lin et al. (2011) [123] Taiwan |

N = 933; 38% aged 65-70 years; 25% aged 71-75yr, 37% aged >75yrs; 48% women. |

Frailty (Fried criteria) | SF-36 |

Robust Pre-frail Frail |

Pop 47% 44% 10% |

QOL Physical 50 (SE 0.5) 48 (SE 0.5) 43 (SE 0.8) |

QOL Mental (subscores) 56 (SE 0.6) 54 (SE 0.6) 53 (SE 0.9) |

|

Chang et al. (2012) [124] Taiwan |

N = 374; mean age = 74.6 ± 6.3 years; 53% women; 16% with fall in previous year; number of comorbidities = 1.4 ± 1.2; |

Frailty (Fried criteria) and using TGUG for slowness criterion (lowest 20%) |

SF-36 |

Robust Pre-frail Frail |

Pop 31% 63% 6% |

QOL Physical 49 ± 8 48 ± 8 40 ± 8 |

QOL Mental (subscores) 57 ± 8 52 ± 9 43 ± 12 |

|

Kull et al. (2012) [125] Estonia |

N = 227; aged 40-70 years, mean age = 55 years; 53% women. |

Sarcopenia: hand-grip strength < 6.5kg/cm2 F / < 24.4kg/cm2 M; or ALM using DXA < 4.87kg/m2 F / < 6.60kg/m2 M (BMD also measured) |

SF-36 |

(sub) Normal Sarcopen Osteopen ‘Sarco-os-’ |

Pop 53% 14% 39% 7% |

QOL Physical 50 na 50 47 |

QOL Mental 48 na 49 42 |

|

Gobbens et al. (2012) [126] Netherlands |

N = 484; aged 75 years and older; N = 336 at 1 year follow-up; N = 266 at 2 years follow-up. |

Frailty assessed according to the Tilburg Frailty Indicator at baseline |

WHOQOL -BREF QLSI |

Medium to very large associations of frailty with advers outcomes and poor QOL 1 or 2 years later. |

|||

|

Langlois et al. (2012) [127] Canada |

N = 83 (39 frail + 44 non-frail | Frailty assessed using a geriatric examination and scored using the Modified Physical Performance Test |

QLSI | Frail elders reported poor self-perception of physical capacity, cognition, affectivity, housekeeping efficacy, and physical health. |

|||

Notes: All studies were of community dwelling individuals; all studies except Gobbens et al were cross-sectional; unless stated patients were at least 65 years old for inclusion

Abbreviations: ALM: appendicular lean mass; BMD: bone mineral density, BP: bodily pain; DXA: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; GH: general health, na: not available; PH: physical health; Pop: population; QLSI: Quality of Life Systemic Inventory Questionnaire; RP role physical; VT: vitality.

In a cross-sectional study – the Hertfordshire Cohort Study [114] – in nearly 3000 community-dwelling men and women aged 59–73 years, the relationships between grip strength and HR-QoL using the SF-36 were investigated. The results showed (using simple unadjusted analyses), that low grip strength (in both men and women) was associated with increased prevalence of having poor scores for all of the domains of the SF-36 instrument. With adjustment for age, height, weight, walking speed, social class, smoking, alcohol consumption and known co-morbidity, lower grip strength remained associated with a low physical functioning score and a low general health score. These relationships were not explained by falls history. Thus, even after adjusting for muscle performance (walking speed), low muscle strength (hand grip) was associated with low HR-QoL

Frailty is associated with poor QoL

Frail and pre-frail individuals have lower QoL scores when compared to age- and comorbidity-matched non-frail individuals. One relevant study in this context is the Hispanic Established Populations Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (Hispanic-EPESE), which enrolled 1008 older adults living in the community [122]. The results showed, after adjusting for sociodemographic and health related covariables, being pre-frail or frail was significantly associated (p < 0.001) with lower scores on all physical and cognitive HR-QoL scales than being non-frail. Furthermore, in a longitudinal study of 484 community-dwelling persons aged 75 years and older frailty status was assessed at baseline (Tilburg Frailty Indicator) and QoL was assessed after 1 and 2 years (WHOQoL-BREF) [126]. The results revealed very large associations between frailty status and poor QoL.

In older frail nursing home residents it has been shown that muscle fatigability (assessed by sustained grip strength) was related to both self-perceived fatigue and QoL (WHOQOL, Mobility-Tiredness scale, physical domain score of SF-36) [128]. Since fatigue is often considered as a key element in frailty, its estimation both objectively and subjectively might help to distinguish the muscular (related to sarcopenia) and mental components affecting QoL in these patients.

Conclusions on QoL research in older populations

What emerges from this research in older populations (and mostly from generic QoL instruments or structured interviews) is that physical functioning plays an extremely important role in QoL. The striking thing about this conclusion is the similarity to the drivers of QoL in patients with chronic diseases [99].

The main drivers of QoL in older adults are therefore: energy, freedom from pain, ability to do activities of daily living and to move around [97,101]. Those who regularly do at least one hour per week of moderately intense physical activity had higher HR-QoL measures (on SF-36) than those who do not [129]. They have a strong need the “need to stay independent” and maintain self-efficacy; any perceived threat to these ideals has a strong negative impact on QoL [85,130].

Yet these drivers (domains) remain difficult to quantify:

The lack of energy (anergia) experienced by some older adults is a complex phenomenon that is often associated with underlying chronic conditions, such as inflammation, under-nutrition, pain, masked depression, and cognitive and functional decline [93]. The concept of “mental energy” in itself is a three-dimensional construct consisting of mood (transient feelings about the presence of fatigue or energy), motivation (determination and enthusiasm), and cognition (sustained attention and vigilance) [131].

The physical activity domain is challenging since there is a huge number of possible subdomains and items. In a review of 104 patient-reported physical activity questionnaires for chronic diseases and older populations [99], Williams and colleagues identified 182 physical activity (sub)domains with 1965 associated items. They concluded, as others have done, that it is crucial to construct a conceptual framework for the areas and boundaries of physical activity early on in such a project.

While the QoL instruments usually refer to the dimension of “physical function”, it should be considered that its reciprocal is “disability” [132] – it is thus a question of perspective. Some clinical specialities, for example rheumatology and gerontology, have an historical preference for the term “disability” over “physical function”. But, if one should adopt the language of the ICF, then one should use “disability” with the concept of an impairment of functioning with respect to generally accepted population standards [41].

It is clear that any new instrument would need to be thoroughly validated in terms of its reliability and sensitivity to change. This aspect of QoL instrument development has advanced significantly in recent years with the publication of the COSMIN guidelines which provide consensus-based standards for the evaluation and development of health-related PROs [133,134]

As part of the FDA roadmap initiative, PROMIS (Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) sets out to provide clinical researchers with a bank of validated QoL modules that can be assembled for computerised scoring [135]. It has defined 3 main components (dimensions): Physical health, Mental Health and Social Health, with 7 sub-components and 16 domains (e.g. pain, fatigue, physical function, negative/positive affect, social isolation, ability to participate in social activities, etc.). In early testing within the field of rheumatology, these modules appear to be effective in assessing self-reported physical functioning [132,136]

There are frequent calls from members of the research community for an approach that uses utility weighting. The value of a measure that can be integrated over time to obtain an overall figure for disability (or dis-utility) is well known. Possibly a time trade off study such as that used by Salkeld and colleagues would be applicable in this population [97]. This approach will be helpful to evaluate the burden of the disease.

In any construct that purports to assess QoL in sarcopenia it will be important to try to understand the effect size of disability on overall QoL. Sarcopenia may only lead to poor QoL in a context of disability and this will be vital to dissect. Frailty is always associated with disability and so carries an inherently greater risk of poor QoL.

An ideal QoL construct in sarcopenia would assess the physical aspects of the musculoskeletal domain and give an even-handed balance to the other factors affecting QoL. It is anticipated that as a patient-reported measure, it would complement the objective assessments of physical performance [137]. It would include the functionality of articulations and the impact of bone health as well as an assessment of pain, fatigue, the emotional aspects and non-health-related dimensions of the conditions. It should also take into account any change in weight and perhaps certain behavioural changes to help explain longitudinal differences. A comprehensive construct, coupled with multivariate analysis models, would provide the most useful outcome trajectories.

Conclusions on goals and challenges of QoL assessment in frailty and sarcopenia

With the publication of three, fairly similar, consensus definitions for sarcopenia, important progress has been made and it is expected that future research will build on this new foundation. It may be hoped that a consensus definition for frailty might soon also see the light of day, for it is clear that medical research and practice advances by the definition of formal criteria that define clinical syndromes. Examples of this in the past include Alzheimer’s disease and osteoporosis [138]; recognised pathological conditions that were once just syndromes.

While the two conditions, sarcopenia and frailty, are closely related, it may be seen that sarcopenia is a key component of frailty. This is as shown schematically in figure 2. Both conditions may be considered as being geriatric syndromes with multifactorial causes, both increasing the risk of serious disability with consequent and strong impact on healthcare costs. It is therefore critical to halt, or slow down this progression. Proactive steps should therefore be taken early following diagnosis.

Figure 2.

The domains of frailty.

Efforts must now be made so that the consensus definitions are widely recognised and refined accordingly. The application of terms, measurement techniques and cut-offs must be used consistently. An important question will be: is it necessary to develop from scratch specific QoL instruments for sarcopenia and frailty? – Or are there available instruments that can be adapted? A variety of PRO instruments have been developed for older populations and there are also some relevant disease-specific instruments, so it may be that some part could be adapted. Also to be considered are the growing number of modules available in the PROMIS program. The SF-36, should still serve as a generic-core, but its limitations are evident.

It can be hoped that healthcare providers and regulatory agencies will recognise that these age-related conditions invoke high personal and social costs and are suitable targets for intervention [139]. In this regard, the European Medicines Agency with its Geriatric Medicines Strategy has taken initial steps for fostering the development of geriatric medicines and incorporating geriatric aspects into the assessment at authorization and post-marketing surveillance of approved drugs [140]. The European Commission, via the Innovation Partnership on Active and Healthy Ageing (EIP on AHA), has put a target of adding 2 healthy life years to citizens by 2020 [141]. Improvements in geriatric medicine will help to make this goal achievable.

Acknowledgements

The of the manuscript from the presentations and discussi for his assistance the draft authors would like to thank Jeremy Grierson, PhD, ons of the working group in preparing participants.

Reference List

- 1.Rosenberg IH. Sarcopenia: origins and clinical relevance. Clin Geriatr Med. 2011;27:337–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malafarina V, Uriz-Otano F, Iniesta R, Gil-Guerrero L. Sarcopenia in the elderly: diagnosis, physiopathology and treatment. Maturitas. 2012;71:109–14. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, Landi F, Martin FC, Michel JP, Rolland Y, Schneider SM, Topinkova E, Vandewoude M, Zamboni M. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39:412–23. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afq034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muscaritoli M, Anker SD, Argiles J, Aversa Z, Bauer JM, Biolo G, Boirie Y, Bosaeus I, Cederholm T, Costelli P, Fearon KC, Laviano A, Maggio M, Rossi FF, Schneider SM, Schols A, Sieber CC. Consensus definition of sarcopenia, cachexia and pre-cachexia: joint document elaborated by Special Interest Groups (SIG) “cachexia-anorexia in chronic wasting diseases” and “nutrition in geriatrics”. Clin Nutr. 2010;29:154–59. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fielding RA, Vellas B, Evans WJ, Bhasin S, Morley JE, Newman AB, bellan van KG, Andrieu S, Bauer J, Breuille D, Cederholm T, Chandler J, de Meynard C, Donini L, Harris T, Kannt A, Keime GF, Onder G, Papanicolaou D, Rolland Y, Rooks D, Sieber C, Souhami E, Verlaan S, Zamboni M. Sarcopenia: an undiagnosed condition in older adults. Current consensus definition: prevalence, etiology, and consequences. International working group on sarcopenia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2011;12:249–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abellan van Kan G, Rolland Y, Bergman H, Morley JE, Kritchevsky SB, Vellas B. The I.A.N.A Task Force on frailty assessment of older people in clinical practice. J Nutr Health Aging. 2008;12:29–37. doi: 10.1007/BF02982161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gielen E, Verschueren S, O’Neill TW, Pye SR, O’Connell MD, Lee DM, Ravindrarajah R, Claessens F, Laurent M, Milisen K, Tournoy J, Dejaeger M, Wu FC, Vanderschueren D, Boonen S. Musculoskeletal frailty: a geriatric syndrome at the core of fracture occurrence in older age. Calcif Tissue Int. 2012;91:161–77. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9622-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cooper C, Dere W, Evans W, Kanis JA, Rizzoli R, Sayer AA, Sieber CC, Kaufman JM, bellan van KG, Boonen S, Adachi J, Mitlak B, Tsouderos Y, Rolland Y, Reginster JY. Frailty and sarcopenia: definitions and outcome parameters. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23:1839–48. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-1913-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyd CM, Xue QL, Simpson CF, Guralnik JM, Fried LP. Frailty, hospitalization, and progression of disability in a cohort of disabled older women. Am J Med. 2005;118:1225–31. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landi F, Liperoti R, Russo A, Giovannini S, Tosato M, Capoluongo E, Bernabei R, Onder G. Sarcopenia as a risk factor for falls in elderly individuals: results from the ilSIRENTE study. Clin Nutr. 2012;31:652–58. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landi F, Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Liperoti R, Russo A, Giovannini S, Tosato M, Capoluongo E, Bernabei R, Onder G. Sarcopenia and mortality risk in frail older persons aged 80 years and older: results from ilSIRENTE study. Age Ageing. 2013;42:203–9. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petermans J. Pathological ageing: a myth or reality? Rev Med Liege. 2012;67:341–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark BC, Manini TM. Sarcopenia =/= dynapenia. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:829–34. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.8.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bauer JM, Sieber CC. Sarcopenia and frailty: a clinician’s controversial point of view. Exp Gerontol. 2008;43:674–78. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fried LP, Xue QL, Cappola AR, Ferrucci L, Chaves P, Varadhan R, Guralnik JM, Leng SX, Semba RD, Walston JD, Blaum CS, Bandeen-Roche K. Nonlinear multisystem physiological dysregulation associated with frailty in older women: implications for etiology and treatment. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:1049–57. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez-Manas L, Feart C, Mann G, Vina J, Chatterji S, Chodzko-Zajko W, Gonzalez-Colaco HM, Bergman H, Carcaillon L, Nicholson C, Scuteri A, Sinclair A, Pelaez M, Van der Cammen T, Beland F, Bickenbach J, Delamarche P, Ferrucci L, Fried LP, Gutierrez-Robledo LM, Rockwood K, Rodriguez AF, Serviddio G, Vega E. Searching for an operational definition of frailty: a delphi method based consensus statement: the frailty operative definition-consensus conference project. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:62–67. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gls119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rockwood K, Stadnyk K, MacKnight C, McDowell I, Hebert R, Hogan DB. A brief clinical instrument to classify frailty in elderly people. Lancet. 1999;353:205–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)04402-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romero-Ortuno R. The Frailty Instrument for primary care of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe predicts mortality similarly to a frailty index based on comprehensive geriatric assessment. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2012 Sep 19; doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00948.x. (ahead of print) doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2012.00948.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogan DB, MacKnight C, Bergman H. Models, definitions, and criteria of frailty. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;15:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Markle-Reid M, Browne G. Conceptualizations of frailty in relation to older adults. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44:58–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Puts MT, Lips P, Deeg DJ. Sex differences in the risk of frailty for mortality independent of disability and chronic diseases. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:40–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stenholm S, Harris TB, Rantanen T, Visser M, Kritchevsky SB, Ferrucci L. Sarcopenic obesity: definition, cause and consequences. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008;11:693–700. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328312c37d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans WJ, Morley JE, Argiles J, Bales C, Baracos V, Guttridge D, Jatoi A, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Lochs H, Mantovani G, Marks D, Mitch WE, Muscaritoli M, Najand A, Ponikowski P, Rossi FF, Schambelan M, Schols A, Schuster M, Thomas D, Wolfe R, Anker SD. Cachexia: a new definition. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:793–99. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumgartner RN, Koehler KM, Gallagher D, Romero L, Heymsfield SB, Ross RR, Garry PJ, Lindeman RD. Epidemiology of sarcopenia among the elderly in New Mexico. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:755–63. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newman AB, Kupelian V, Visser M, Simonsick E, Goodpaster B, Nevitt M, Kritchevsky SB, Tylavsky FA, Rubin SM, Harris TB. Sarcopenia: alternative definitions and associations with lower extremity function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:1602–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baumgartner RN, Wayne SJ, Waters DL, Janssen I, Gallagher D, Morley JE. Sarcopenic obesity predicts instrumental activities of daily living disability in the elderly. Obes Res. 2004;12:1995–2004. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rolland Y, Lauwers-Cances V, Cristini C, bellan van KG, Janssen I, Morley JE, Vellas B. Difficulties with physical function associated with obesity, sarcopenia, and sarcopenic-obesity in community-dwelling elderly women: the EPIDOS (EPIDemiologie de l’OSteoporose) Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89:1895–900. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asher L, Aresu M, Falaschetti E, Mindell J. Most older pedestrians are unable to cross the road in time: a cross-sectional study. Age Ageing. 2012;41:690–694. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lauretani F, Russo CR, Bandinelli S, Bartali B, Cavazzini C, Di Iorio A, Corsi AM, Rantanen T, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Age-associated changes in skeletal muscles and their effect on mobility: an operational diagnosis of sarcopenia. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:1851–60. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00246.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Penninx BW, Nicklas BJ, Simonsick EM, Newman AB, Tylavsky FA, Brach JS, Satterfield S, Bauer DC, Visser M, Rubin SM, Harris TB, Pahor M. Prognostic value of usual gait speed in well-functioning older people--results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1675–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Pieper CF, Leveille SG, Markides KS, Ostir GV, Studenski S, Berkman LF, Wallace RB. Lower extremity function and subsequent disability: consistency across studies, predictive models, and value of gait speed alone compared with the short physical performance battery. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M221–M231. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.4.m221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Iersel MB, Rikkert MG. Frailty criteria give heterogeneous results when applied in clinical practice. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:728–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00668_14.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ble A, Cherubini A, Volpato S, Bartali B, Walston JD, Windham BG, Bandinelli S, Lauretani F, Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L. Lower plasma vitamin E levels are associated with the frailty syndrome: the InCHIANTI study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 61:278–83. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.3.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romero-Ortuno R, Walsh CD, Lawlor BA, Kenny RA. A frailty instrument for primary care: findings from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) BMC Geriatr. 2010;10:57. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-10-57. 2006. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-10-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang SS, Weiss CO, Xue QL, Fried LP. Patterns of comorbid inflammatory diseases in frail older women: the Women’s Health and Aging Studies I and II. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:407–13. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rolland Y, Abellan van Kan G, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Roux C, Boonen S, Vellas B. Strontium ranelate and risk of vertebral fractures in frail osteoporotic women. Bone. 2011;48:332–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mijnarends DM, Meijers JM, Halfens RJ, Ter BS, Luiking YC, Verlaan S, Schoberer D, Cruz Jentoft AJ, van Loon LJ, Schols JM. Validity and Reliability of Tools to Measure Muscle Mass, Strength, and Physical Performance in Community-Dwelling Older People: A Systematic Review. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;14:170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts HC, Denison HJ, Martin HJ, Patel HP, Syddall H, Cooper C, Sayer AA. A review of the measurement of grip strength in clinical and epidemiological studies: towards a standardised approach. Age Ageing. 2011;40:423–29. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jette AM. Toward a common language of disablement. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:1165–68. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organisation [Accessed 7 March 2013];Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health - The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. 2002 http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/training/icfbeginnersguide.pdf.

- 42.Delmonico MJ, Harris TB, Visser M, Park SW, Conroy MB, Velasquez-Mieyer P, Boudreau R, Manini TM, Nevitt M, Newman AB, Goodpaster BH. Longitudinal study of muscle strength, quality, and adipose tissue infiltration. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:1579–85. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fantin F, Di Francesco V, Fontana G, Zivelonghi A, Bissoli L, Zoico E, Rossi A, Micciolo R, Bosello O, Zamboni M. Longitudinal body composition changes in old men and women: interrelationships with worsening disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:1375–81. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.12.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Frontera WR, Reid KF, Phillips EM, Krivickas LS, Hughes VA, Roubenoff R, Fielding RA. Muscle fiber size and function in elderly humans: a longitudinal study. J Appl Physiol. 2008;105:637–42. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90332.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song MY, Ruts E, Kim J, Janumala I, Heymsfield S, Gallagher D. Sarcopenia and increased adipose tissue infiltration of muscle in elderly African American women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:874–80. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamrick MW. A role for myokines in muscle-bone interactions. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2011;39:43–47. doi: 10.1097/JES.0b013e318201f601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscles, exercise and obesity: skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8:457–65. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2012.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bischoff-Ferrari HA. Relevance of vitamin D in muscle health. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2012;13:71–77. doi: 10.1007/s11154-011-9200-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Body JJ, Bergmann P, Boonen S, Devogelaer JP, Gielen E, Goemaere S, Kaufman JM, Rozenberg S, Reginster JY. Extraskeletal benefits and risks of calcium, vitamin D and anti-osteoporosis medications. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(Suppl 1):S1–23. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1891-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sakuma K, Yamaguchi A. Sarcopenia and cachexia: the adaptations of negative regulators of skeletal muscle mass. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2012;3:77–94. doi: 10.1007/s13539-011-0052-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Genaro PS, Martini LA. Effect of protein intake on bone and muscle mass in the elderly. Nutr Rev. 2010;68:616–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waters DL, Baumgartner RN, Garry PJ, Vellas B. Advantages of dietary, exercise-related, and therapeutic interventions to prevent and treat sarcopenia in adult patients: an update. Clin Interv Aging. 2010;5:259–70. doi: 10.2147/cia.s6920. 259-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carcaillon L, Garcia-Garcia FJ, Tresguerres JA, Gutierrez AG, Kireev R, Rodriguez-Manas L. Higher levels of endogenous estradiol are associated with frailty in postmenopausal women from the toledo study for healthy aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2898–906. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carcaillon L, Blanco C, Alonso-Bouzon C, Alfaro-Acha A, Garcia-Garcia FJ, Rodriguez-Manas L. Sex differences in the association between serum levels of testosterone and frailty in an elderly population: the Toledo Study for Healthy Aging. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032401. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Breen L, Phillips SM. Skeletal muscle protein metabolism in the elderly: Interventions to counteract the ‘anabolic resistance’ of ageing. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2011;8:68. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-8-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Faulkner JA, Larkin LM, Claflin DR, Brooks SV. Age-related changes in the structure and function of skeletal muscles. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:1091–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beyer I, Mets T, Bautmans I. Chronic low-grade inflammation and age-related sarcopenia. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2012;15:12–22. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32834dd297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goodpaster BH, Carlson CL, Visser M, Kelley DE, Scherzinger A, Harris TB, Stamm E, Newman AB. Attenuation of skeletal muscle and strength in the elderly: The Health ABC Study. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:2157–65. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.6.2157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mithal A, Bonjour JP, Boonen S, Burckhardt P, Degens H, El Hajj FG, Josse R, Lips P, Morales TJ, Rizzoli R, Yoshimura N, Wahl DA, Cooper C, Dawson-Hughes B. Impact of nutrition on muscle mass, strength, and performance in older adults. Osteoporos Int. 2012 Dec 18; doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2236-y. ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morley JE. Undernutrition in older adults. Fam Pract. 2012;29:i89. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr054. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmr054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fiatarone Singh MA, Singh NA, Hansen RD, Finnegan TP, Allen BJ, Diamond TH, Diwan AD, Lloyd BD, Williamson DA, Smith EU, Grady JN, Stavrinos TM, Thompson MW. Methodology and baseline characteristics for the Sarcopenia and Hip Fracture study: a 5-year prospective study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64:568–74. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cuervo M, Garcia A, Ansorena D, Sanchez-Villegas A, Martinez-Gonzalez M, Astiasaran I, Martinez J. Nutritional assessment interpretation on 22,007 Spanish community-dwelling elders through the Mini Nutritional Assessment test. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12:82–90. doi: 10.1017/S136898000800195X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]