Abstract

We combine kinship estimates with traditional F-statistics to explain contemporary drivers of population genetic differentiation despite high gene flow. We investigate range-wide population genetic structure of the California spiny (or red rock) lobster (Panulirus interruptus) and find slight, but significant global population differentiation in mtDNA (ΦST = 0.006, P = 0.001; Dest_Chao = 0.025) and seven nuclear microsatellites (FST = 0.004, P < 0.001; Dest_Chao = 0.03), despite the species’ 240- to 330-day pelagic larval duration. Significant population structure does not correlate with distance between sampling locations, and pairwise FST between adjacent sites often exceeds that among geographically distant locations. This result would typically be interpreted as unexplainable, chaotic genetic patchiness. However, kinship levels differ significantly among sites (pseudo-F16,988 = 1.39, P = 0.001), and ten of 17 sample sites have significantly greater numbers of kin than expected by chance (P < 0.05). Moreover, a higher proportion of kin within sites strongly correlates with greater genetic differentiation among sites (Dest_Chao, R2 = 0.66, P < 0.005). Sites with elevated mean kinship were geographically proximate to regions of high upwelling intensity (R2 = 0.41, P = 0.0009). These results indicate that P. interruptus does not maintain a single homogenous population, despite extreme dispersal potential. Instead, these lobsters appear to either have substantial localized recruitment or maintain planktonic larval cohesiveness whereby siblings more likely settle together than disperse across sites. More broadly, our results contribute to a growing number of studies showing that low FST and high family structure across populations can coexist, illuminating the foundations of cryptic genetic patterns and the nature of marine dispersal.

Keywords: larval behaviour, marine connectivity, pelagic larval dispersal, phylogeography, population genetics, Southern California Bight, spiny lobster

Introduction

Determining the temporal and spatial scales of dispersal and gene flow across species’ ranges is essential for effective conservation and management. F-statistics (Wright 1943) and their analogues (e.g. Nei 1973; Weir & Cockerham 1984; Excoffier et al. 1992; Hedrick 1999) have been the workhorses in this regard for over 65 years. However, as both the number and diversity of genetic markers have increased, so has the demand for analyses that can complement fixation indices and extend our understanding of genetic data beyond the single marker, two-allele system pioneered by Wright (1943). Coalescent simulations (Kingman 1982) have emerged as the most informative techniques for distinguishing between historical and contemporary drivers of population differentiation (Hey & Wakeley 1997; Tavare et al. 1997; Rosenberg & Nordborg 2002; Rozas et al. 2003; Drummond et al. 2005; Hickerson et al. 2006; Hey & Nielsen 2007; Eldon & Wakeley 2009). By incorporating data from multiple nucleotide sequence-based markers, these equilibrium-independent analyses can isolate the effects of effective population size, demographic history, migration, mutation and drift summarized by FST (Hart & Marko 2010; Marko & Hart 2011, 2012). However, for fragment length data such as that generated by microsatellite markers, a number of alternative approaches have been advanced that can add insight into what is driving FST patterns (reviewed in Hedgecock et al. 2007; Lowe & Allendorf 2010).

One underutilized approach is the coupling of indirect metrics of gene flow (e.g. F-statistics, Dest_Chao) with more direct measures such as kinship or parentage analyses (e.g. Loiselle et al. 1995; Selkoe et al. 2006; Buston et al. 2009; Christie et al. 2010; Palsbøll et al. 2010). Broadly speaking, kinship analyses provide an index of the relative relatedness of all genotyped individuals in a data set, and parentage is a distinct case of kinship whereby the most likely parents of individual juveniles are identified (Vekemans & Hardy 2004; Jones & Arden 2003; reviewed in Blouin 2003; Jones et al. 2010). Kinship coefficients (also known as coefficients of coancestry) are widely interpreted as the probability of identity by descent of the genes, but they are more properly defined as ‘ratios of differences of probabilities of identity in state’ (Hardy & Vekemans 2002, p. 23) from homologous genes sampled randomly from each pair of individuals (Hardy & Vekemans 2002; Rousset 2002; Blouin 2003; Vekemans & Hardy 2004).

By comparison, F-statistics and Dest_Chao are often blind to the relatedness of individuals; different population samples with the same kinship structure can have very different levels of genetic differentiation among them and vice versa. By assessing how alleles are shared among individuals, kinship analyses can elucidate which locations have comparatively little ongoing genetic exchange in situations where low FST values suggest high contemporary population connectivity. This clarification is important because such inferences can in fact be due to historically high migration rates, effective population sizes or measurement error (Hart & Marko 2010; Marko & Hart 2011, 2012; Faurby & Barber 2012).

Direct evidence of coancestry between individuals provides a particularly valuable complement to F-statistics when it is not possible to derive other independent estimates of demographic connectivity such as through the tagging and tracking of adults or larvae (e.g. Bellquist et al. 2008; Meyer et al. 2009; Cartamil et al. 2011; Carson et al. 2011; López-Duarte et al. 2012; reviewed in Lowe & Allendorf 2010). In marine systems, the majority of taxa have relatively sedentary adults, but a pelagic larval stage that persists in the water column from a few minutes to over a year (Thorson 1950; Strathmann 1987; McEdward 1995). These larvae are notoriously difficult to track directly (Levin 2006), but the time that larvae spend in the open ocean has led to the intuitive expectation that the majority of marine species have high levels of gene flow (Hedgecock et al. 2007). However, the preponderance of recent indirect genetic evidence, based mostly on F-statistics, indicates that there is generally a weak relationship between dispersal potential inferred from pelagic larval duration (PLD) and genetic structure (reviewed in Bradbury et al. 2008; Shanks 2009; Weersing & Toonen 2009; Riginos et al. 2011; Selkoe & Toonen 2011). Furthermore, it is generally overlooked that indirect gene flow via multigenerational stepping-stone dispersal at small scales can mimic direct gene flow across large scales (Puebla et al. 2012). The relatively few studies that have directly measured larval dispersal through larval tagging or parentage analyses have bolstered the claim that many larvae have limited dispersal and often recruit back to their region of origin (Jones et al. 2005; Gerlach et al. 2007; Planes et al. 2009; López-Duarte et al. 2012). Due to the nature of these direct (kinship/parentage) versus indirect (F-statistics) measures of population connectivity, it is possible that direct analyses may identify recruitment patterns that cannot be detected using traditional F-statistics (Waples & Gaggiotti 2006; Saenz-Agudelo et al. 2009; Palsbøll et al. 2010). For example, Christie et al. (2010) found little genetic differentiation (max FST = 0.0097) among populations of bicolor damselfish (Stegastes partitus) in Exuma Sound, Bahamas, but parentage analysis identified high levels of self-recruitment at two of the eleven sampled locations. The direct identification of parent–offspring pairs resulted in very different management advice for this species than interpretation based on the FST data alone.

To date, most marine kinship studies have understandably focused on parent–offspring identification in reef fishes with fairly short larval durations. Here, we show that kinship analyses can also be useful at the opposite end of the potential dispersal continuum: the California spiny, or red rock lobster, Panulirus interruptus (Randall 1840), spends at least the first 8 months of its life in the plankton, during which time it can presumably disperse across its entire geographic range. Species without barriers to dispersal are expected to exhibit no detectable neutral genetic population structure. Here, we use the California spiny lobster as a model to test the intuitive assumption of genetic homogeneity in species with extended PLD. We demonstrate the utility of individual-based estimates of genetic exchange in the interpretation of connectivity based on F-statistics.

Methods

Study system

The California spiny or red rock lobster, Panulirus interruptus, exhibits high site fidelity during its adult phase (Withy-Allen 2010), but has a two-phase pelagic larval stage with a total PLD of 8–11 months (Johnson 1956, 1960; Serfling & Ford 1975). The initial phyllosoma stage undergoes multiple moults to produce 11 vertically and geographically stratified stages in the pelagic environment (Johnson 1960; Pringle 1986). The 11th phyllosoma stage molts into the final puerulus stage, which settles into the lobster's preferred juvenile habitat. Panulirus interruptus can be found across a 1400-km Pacific coast range from Monterey Bay, CA (although very rare north of Point Concepcion) to Bahia Magdalena, Mexico. Throughout its geographic distribution, P. interruptus plays an important ecological role in structuring both kelp forest and intertidal communities (Tegner & Levin 1983; Robles 1987; Lafferty 2004). Spiny lobsters are also a valuable commercial and recreational fisheries species in both Mexico and the USA with a combined value of over $39 million from the most recent estimates (Chávez & Gorostieta 2010; Porzio 2012).

Sample collection and DNA extraction

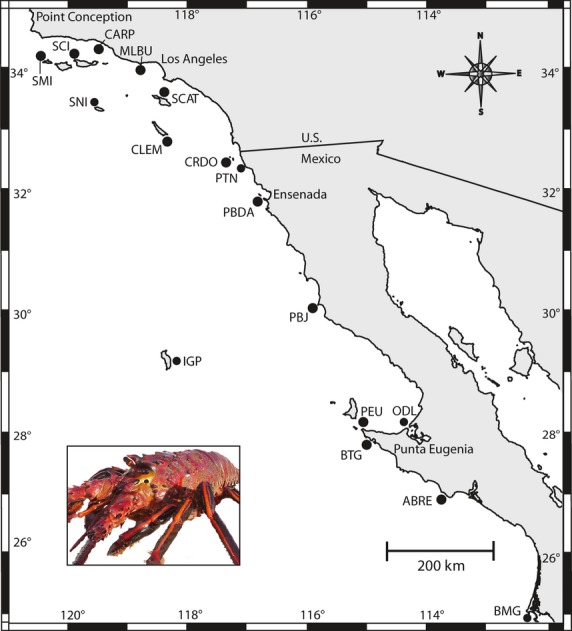

We collected tissue samples from 1102 P. interruptus individuals across 17 sites located throughout the entire Pacific coastal range from Point Conception, CA, in the north to Bahia Magdalena (BMG), Baja California Sur, Mexico, in the south (Fig. 1, Table 1). Samples were collected nonlethally by removing a small piece of an antenna or a leg segment from each lobster. Lobsters were either captured by hand while Scuba diving or obtained from commercial fishermen. Tissue samples were preserved in 95% ethanol and stored at room temperature until extracted. DNA was isolated using a standard salting-out protocol (Sunnucks & Hales 1996), a rapid-boil technique (Valsecchi 1998) or DNeasy Animal Tissue kits (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA, USA).

Fig. 1.

Map of lobster specimen collection locations in the Southern California Bight and Baja California, Mexico. CARP, Carpinteria, CA; SMI, San Miguel Island, CA; SCI, Santa Cruz Island, CA; MLBU, Malibu, CA; SCAT, Santa Catalina Island, CA; SNI, San Nicholas Island, CA; CLEM, San Clemente Island, CA; CRDO, Islas Coronados, Mx; PTN, Puerto Nuevo, Mx; PBDA, Punta Banda, Mx; PBJ, Punta Baja, Mx; IGP, Isla Guadalupe, Mx; ODL, Laguna Ojo de Liebre, Mx; PEU, Punta Eugenia, Mx; BTG, Bahia Tortugas, Mx; ABRE, Punta Abreojos, Mx; BMG, Bahia Magdalena, Mx. Photo credit: Patrick W. Robinson.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for Panulirus interruptus listed from northernmost to southernmost collection sites: total number of individuals sequenced for seven microsatellites (N, nDNA) and mtDNA cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (N, mtDNA)

| Collection site (abbreviation) | N | h | heff | π | AR | Aeff | Ho | He | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nDNA | mtDNA | ||||||||

| Carpinteria (CARP) | 74 | 57 | 0.94 | 16.67 | 0.011 | 18.46 | 15.98 | 0.83 | 0.89 |

| San Miguel Island (SMI) | 76 | 60 | 0.93 | 14.29 | 0.007 | 18.11 | 14.59 | 0.81 | 0.88 |

| Santa Cruz Island (SCI) | 54 | 53 | 0.92 | 12.50 | 0.005 | 18.48 | 15.51 | 0.84 | 0.89 |

| Malibu (MLBU) | 71 | 68 | 0.93 | 14.29 | 0.018 | 17.86 | 15.37 | 0.87 | 0.90 |

| Santa Catalina Island (SCAT) | 81 | 56 | 0.94 | 16.68 | 0.008 | 17.46 | 14.74 | 0.83 | 0.88 |

| San Nicholas Island (SNI) | 38 | 36 | 0.94 | 16.67 | 0.006 | 16.66 | 12.22 | 0.76 | 0.86 |

| San Clemente Island (CLEM) | 25 | 63 | 0.92 | 12.50 | 0.008 | 18.14 | 12.37 | 0.87 | 0.89 |

| Islas Coronados (CRDO) | 63 | 61 | 0.94 | 16.67 | 0.012 | 18.42 | 15.78 | 0.84 | 0.89 |

| Puerto Nuevo (PTN) | 57 | 56 | 0.91 | 11.11 | 0.007 | 16.83 | 13.65 | 0.86 | 0.88 |

| Punta Banda (PBDA) | 47 | 38 | 0.94 | 16.67 | 0.009 | 16.19 | 12.05 | 0.78 | 0.88 |

| Punta Baja (PBJ) | 94 | 70 | 0.88 | 8.33 | 0.009 | 17.85 | 15.06 | 0.86 | 0.88 |

| Isla Guadalupe (IGP) | 69 | 79 | 0.91 | 11.11 | 0.011 | 17.20 | 14.02 | 0.82 | 0.88 |

| Laguna Ojo de Liebre (ODL) | 42 | 55 | 0.91 | 11.11 | 0.008 | 18.51 | 15.34 | 0.83 | 0.88 |

| Punta Eugenia (PEU) | 45 | 45 | 0.93 | 14.29 | 0.012 | 17.36 | 13.39 | 0.82 | 0.89 |

| Bahia Tortugas (BTG) | 40 | 47 | 0.93 | 14.29 | 0.012 | 16.83 | 12.66 | 0.81 | 0.88 |

| Punta Abreojos (ABRE) | 66 | 42 | 0.88 | 8.33 | 0.009 | 17.44 | 14.96 | 0.84 | 0.89 |

| Bahia Magdalena (BMG) | 47 | 45 | 0.95 | 20.00 | 0.012 | 17.92 | 15.01 | 0.86 | 0.88 |

For mtDNA: haplotype diversity (h), effective number of haplotypes (heff) and nucleotide diversity (π). For nDNA microsatellites: rarefied allelic richness (AR), effective number of alleles (Aeff), observed (Ho) and expected (He) heterozygosity.

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)

We amplified a 494-bp fragment of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene (COI) using species-specific primers PintCOI-F (5′-GCTTGAGCTGGAATGGTAGG-3′) and PintCOI-R (5′-CACTTCCTTCTTTGATCCC-3′), which were designed from GenBank sequence #AF339460 (Ptacek et al. 2001) using primer3 (Rozen & Skaletsky 2000). Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) for each sample were performed in a 20-μl reaction volume containing 10 μL of 2× Biomix Red (Bioline, Taunton, MA, USA), 0.125 μm each of forward and reverse primer, 5–50 ng of genomic DNA and 0.75× bovine serum albumin. PCR was carried out on a Bio-Rad Mycycler Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad Laboratories Hercules, CA, USA), with an initial denaturation step of 95 °C for 4 min, 35 cycles of denaturation (95 °C for 30 s), annealing (56 °C for 30 s) and extension (72 °C for 30 s), followed by a final extension step of 72 °C for 10 min. PCR products were treated with 0.75 units of Exonuclease I and 0.5 units of Fast Alkaline Phosphatase (ExoFAP; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) per 7.5 μL of PCR product and incubated at 37 °C for 60 min, followed by deactivation at 85 °C for 10 min. Purified DNA fragments were sequenced in the forward direction with fluorescently labelled dideoxy terminators either on an ABI 3730XL capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) by the Advanced Studies of Genomics, Proteomics and Bioinformatics (ASGPB) Center at the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa or an ABI 3130XL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems) at the Hawai'i Institute of Marine Biology EPSCoR Sequencing Facility. Unique sequences and sequences with ambiguous nucleotide calls were also sequenced in reverse to confirm sequence identity. Sequences were edited, aligned and trimmed to a uniform size using sequencher 4.8b (GeneCodes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). The alignment did not contain any indels or frameshift mutations.

We calculated nucleotide (π) and haplotype diversity (h) for each sampling site as described in Nei (1987) using arlequin 3.5 (Excoffier et al. 2005). To visualize relationships between individual sequences, we constructed a median-joining network (Bandelt et al. 1999) using network 4.6.0.0 (http://www.Fluxus-engineering.com/network_terms.htm). We investigated population structure using an analysis of molecular variance (amova) as implemented in arlequin. We used an analogue of Wright's FST (ΦST), which incorporates a model of sequence evolution, for both our complete data set and pairwise population comparisons (Weir & Cockerham 1984; Excoffier et al. 1992). Using jModelTest2 (Guindon & Gascuel 2003; Darriba et al. 2012), we determined that the Tamura & Nei (1993) with a Ti/Tv ratio of 11.2 and gamma parameter of 2.1 was the most appropriate model of sequence evolution implemented in arlequin. Global ΦST and each pairwise population ΦST were tested for significance with 100,000 permutations. Due to the high heterozygosity in cytochrome c oxidase subunit I gene (COI) in P. interruptus, we also calculated Dest_Chao as an absolute measure of differentiation between sites. The magnitude of FST is inversely proportional to heterozygosity (Hedrick 2005; Meirmans 2006; Jost 2008), while Dest_Chao is less susceptible to biases caused by genetic diversity (Bird et al. 2011). For mtDNA, Dest_Chao (Jost 2008) was calculated with spade (Chao & Shen 2009). Mantel tests using linearized FST [FST/(1 − FST)] and the natural log of Euclidean distance (Rousset 1997) were conducted in genodive 2.0b20 (Meirmans & Van Tienderen 2004) to test for isolation by distance (IBD) among all sample sites, as well as subsets of sites across the range (California sites, Mexico sites, all island sites, all mainland/continental sites).

Microsatellite DNA

Seven previously developed microsatellites (A5, A102r, A110, Pin29L, Pin189, Pin10 and Pin244) (Ben-Horin et al. 2009) were amplified by PCR in a 10-μL reaction volume containing 1× GoTaq Reaction Buffer (with 1.5 mm MgCl2 pH 8.5; Promega Corp., Madison, WI, USA), 2 μm total dNTPs, 0.1 U GoTaq polymerase (Promega Corp.), 6 μm each of forward and reverse primer and 20 ng of genomic DNA. PCR was carried out using a Bio-Rad DNA Engine Dyad Thermal Cycler with the following conditions: an initial denaturation step of 95 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles of denaturation (94 °C for 40 s), annealing at primer-specific annealing temperatures (for 40 s; see Table 1 in Ben-Horin et al. 2009) and extension (72 °C for 40 s) and a final extension step of 72 °C for 30 min. Forward primers were fluorescently labelled with WellRed D2, D3 or D4 dye (Beckman Coulter Inc., Fullerton, CA, USA; see Table 1 in Ben-Horin et al. 2009 for primer labels). Microsatellite PCR products were sized on a Beckman Coulter CEQ 8000 capillary sequencer with a 400-bp size standard (Beckman Coulter Inc.). Alleles were scored using a CEQ 8000 genetic analysis system (Beckman Coulter Inc.).

Microsatellite quality control [Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), linkage equilibrium, scoring errors] followed Selkoe & Toonen (2006) as detailed in Ben-Horin et al. (2009), but expanded across all sample locations and loci. Additionally, null allele frequency was re-calculated with ML-Relate (Kalinowski et al. 2006) to enable significance testing. We calculated observed (Ho) and expected (He) heterozygosities at each location, as well as allelic richness (A), rarefied to 25 individuals, using the Excel Microsatellite Toolkit 3.1.1 (Park 2001) and fstat (Goudet 2001), respectively. We also calculated the effective number of alleles at each locus in GenoDive. Overall genetic structure was analysed using an amova framework (Excoffier et al. 1992) implemented in genodive assuming the infinite allele model, with FST equivalent to Weir & Cockerham's θ (1984). Consistent with mtDNA (COI), microsatellite allelic diversity was likewise high, so we calculated Dest_Chao (Jost 2008) in addition to FST. GenoDive was used to calculate pairwise FST and Dest_Chao for all sampling location pairs, and FST was tested for significance using 100 000 permutations. Patterns of IBD were investigated for microsatellite data in GenoDive as described above for mtDNA. The program geste 2.0 (Foll & Gaggiotti 2006) was used to calculate local FST, a site-specific metric of allelic differentiation that accounts for the nonindependence inherent in multiple comparisons (Balding & Nichols 1995; Hudson 1998).

Kinship

In order to further examine the factors driving the observed FST and Dest_Chao patterns, we calculated kinship coefficients (Loiselle et al. 1995) for each pair of individuals in genodive. These coefficients are based on the probability of identity of two alleles for each pair of homologous genes compared between each pair of individuals. Kinship was estimated with respect to the allele frequencies for the full data set, so these coefficients provide an index of relative relatedness between each pair of individuals. In order to determine whether individuals collected at the same location were more closely related to each other than individuals collected at different locations, we conducted an amova on the kinship coefficients. This approach compared the variation in within-population kinship coefficients with the variation in among-population kinship coefficients using the permanova+ 1.0.2 software add-on as implemented in primer6 (Clarke & Warwick 2001), following Stat et al. (2011) and Padilla-Gamiño et al. (2012). Specifically, the kinship covariance matrix created in genodive was loaded into primer6 as a Correlation Resemblance Matrix. A simple one-way analysis of variance (termed permanova in primer6) was conducted with 10 000 unrestricted permutations of the raw data and type III sums of squared differences. Significance is determined by evaluating a pseudo-F value (Clarke & Warwick 2001) based on the F-distribution, which is not to be confused with Wright's F-statistics.

To investigate site-specific patterns in kinship, we counted the number of closely related individuals within each site where the kinship coefficient was greater than or equal to the equivalent of that expected for quarter-siblings (0.047). Following Selkoe et al.'s (2006) and Buston et al.'s (2009) analysis of relatedness approach, we binned our counts of closely related lobsters according to specific levels of kinship. We used the Loiselle et al.'s (1995) coancestry coefficients (full-sib = 0.25, half-sib = 0.125) to generate the following bins: ‘nearly identical’, 0.57 > k > 0.375; ‘full-sib’, 0.375 > k > 0.1875; ‘half-sib’, 0.1875 > k > 0.09375; and ‘quarter-sib’, 0.09375 > k > 0.047. These bounds represent the midpoints between the coancestry coefficients in Loiselle et al. (1995), and we use quarter-sib as a short-hand to represent half of the level of coancestry as half-sibs. The nearly identical bin represents comparisons above full-sibs and is based on our kinship coefficient distribution for comparisons of individuals to themselves. We tested multiple bin sizes and divisions and found our results to be robust to these changes. To test for an overabundance of closely related lobsters within sites, we implemented a permutation test (10 000 replicates) where the lobsters were randomly assigned to sites and the observed number of closely related individuals was compared to the null distribution for each site. We calculated the maximum-likelihood estimate of relatedness (r) in ML-Relate, following the scale for the index of relatedness (full-sibs, r = 0.5; half-sibs = 0.25) to be able to compare our kinship results with a relatedness index. We also tested the relationship of the mean pairwise FST, mean pairwise Dest_Chao and local FST for each site with the proportion of closely related lobsters at that site (summed across all four sibship categories for the Loiselle et al. (1995) metric and across half-sibs and full-sibs in ML-Relate).

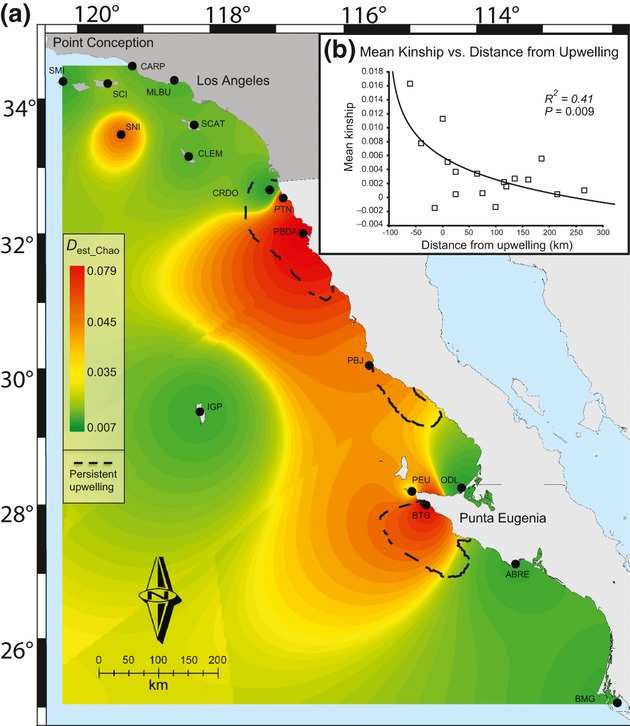

Upwelling

We identified hotspots of genetic differentiation by calculating mean Dest_Chao for each sampling location. We interpolated these values beyond the specific sites we sampled using an inverse weighted distance (IWD) algorithm in the Spatial Analyst extension in arcgis 10. To test the hypothesis that upwelling is a potential driver of both increased kinship and, in turn, site-specific genetic structure for P. interruptus in this region, we overlaid on this map known areas of consistent upwelling in Baja California, Mexico (as identified by Zaytsev et al. (2003)). We tested the relationship between the mean kinship at a site and that site's closest distance to an area of persistent upwelling. For sites within the Southern California Bight (SCB), where there are no areas of persistent upwelling, either the distance to Point Conception or to the edge of the northernmost upwelling area in Baja California, Mexico, was used, whichever was shorter. The southernmost sites in the range were measured to an upwelling area just off of BMG, which was identified by Zaytsev et al. (2003), but is not included in our figure. Negative distances represent sites that are located within upwelling regions and are measured from their location to the nearest edge of the upwelling zone. Both kinship and upwelling regression analyses were performed in spss 17.0.

Results

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA)

We sequenced COI for 931 individuals across 17 sites, which yielded 238 haplotypes. Haplotype diversity (h) was high, ranging from 0.88 to 0.95 (8.3–20 effective haplotypes), with a mean of 0.92 (12.5 effective haplotypes). In contrast, nucleotide diversity (π) was relatively low, ranging from 0.005 to 0.018, with a mean of 0.010. The number of individuals sequenced (N), haplotype diversity (h), effective number of haplotypes (heff) and nucleotide diversity (π) for each site are listed in Table 1.

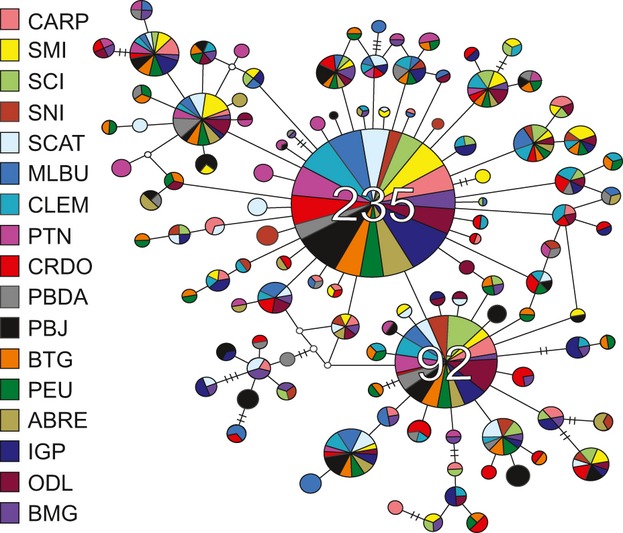

The median-joining network (Fig. 2) reveals two dominant haplotypes differing by one-nucleotide substitute and present at all sample sites. The most numerous haplotype was found in 235 individuals (25% of individuals sequenced), and the second most numerous haplotype was found in 92 individuals (10%). The haplotype network was characterized by a starburst pattern, with the majority of remaining haplotypes differentiated by one to two base pairs from the dominant haplotypes. Eighty haplotypes were represented in only two individuals and there were 131 singletons across all 17 sites; the removal of singletons did not impact the overall structure of the haplotype network (Fig. 2), so they were omitted for ease of visualization. A full, unedited network is included in Fig. S3 (Supporting information).

Fig. 2.

Median-joining network for Panulirus interruptus mtDNA, constructed using 454 base pairs of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) from each of 931 individuals in the program network 4.6.0.0. Each circle is a unique haplotype proportional in size to the number of individuals with that haplotype. The two largest circles represent 235 and 95 individuals. The smallest circle represents two individuals: there are 131 singletons in the data set, but these have been omitted for ease of visualization. A full, unedited network is included in the supplementary material (Fig. S3, Supporting information). Colours correspond to one of 17 locations where the individual haplotypes were found (see key, Fig. 1, Table 1). Lines connecting haplotypes represent a single base-pair difference between haplotypes, with crossing lines representing additional differences.

Global ΦST (0.006) was low, but significant (P = 0.001). Statistically significant pairwise ΦST values were 0.01–0.04, and in general, Dest_Chao values were an order of magnitude higher than ΦST, both for global Dest_Chao (0.025) and for each of the pairwise comparisons, ranging up to 0.300 (Table 2). Among pairwise ΦST comparisons, 26 of 136 (19%, Table 2) were significant at P < 0.05; however, after correcting for the false discovery rate (Benjamini et al. 2006), no pairwise comparisons were significant (P < 0.00035, Table 2). There was no pattern of IBD (Wright 1943) at any scale in the data set. This was true whether we examined all sampling locations together, or for any of the specific subregions: all Mexico sampling locations, California locations (SCB), only islands and only continental sites (Table S1, Supporting information).

Table 2.

Panulirus interruptus pairwise population structure results for (a) seven microsatellite loci and (b) a 494-bp fragment of the mtDNA cytochrome c oxidase subunit I region (COI)

| CARP | SMI | SCI | MLBU | SCAT | SNI | CLEM | CRDO | PTN | PBDA | PBJ | IGP | ODL | PEU | BTG | ABRE | BMG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | |||||||||||||||||

| CARP | — | 0.035 | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.016 | 0.030 | 0.028 | −0.011 | 0.048 | 0.066 | 0.033 | 0.032 | 0.002 | 0.027 | 0.053 | 0.017 | 0.018 |

| SMI | 0.005* | — | 0.013 | 0.030 | 0.026 | 0.031 | 0.016 | 0.019 | 0.063 | 0.073 | 0.035 | 0.003 | −0.006 | 0.037 | 0.071 | 0.010 | −0.008 |

| SCI | 0.001 | 0.002 | — | 0.008 | 0.028 | 0.048 | 0.014 | 0.006 | 0.043 | 0.049 | 0.025 | 0.006 | −0.002 | 0.024 | 0.060 | 0.009 | 0.011 |

| MLBU | 0.001 | 0.004* | 0.001 | — | 0.014 | 0.036 | −0.005 | −0.005 | 0.015 | 0.067 | 0.023 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.018 | 0.042 | 0 | 0.012 |

| SCAT | 0.002 | 0.004* | 0.004* | 0.002 | — | −0.001 | 0.026 | −0.005 | 0.041 | 0.089 | 0.040 | 0.029 | 0.007 | 0.034 | 0.029 | 0.013 | 0.023 |

| SNI | 0.004‡ | 0.005‡ | 0.007* | 0.005‡ | 0 | — | 0.038 | 0.021 | 0.052 | 0.093 | 0.054 | 0.032 | 0.011 | 0.027 | 0.030 | 0.032 | 0.017 |

| CLEM | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.002 | −0.001 | 0.003 | 0.005 | — | −0.009 | 0.056 | 0.073 | 0.035 | 0.010 | −0.012 | 0.002 | 0.073 | 0.019 | −0.005 |

| CRDO | −0.001 | 0.002‡ | 0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 | 0.003 | −0.001 | — | 0.028 | 0.059 | 0.013 | 0.001 | −0.012 | 0.008 | 0.037 | −0.005 | 0.003 |

| PTN | 0.006** | 0.009** | 0.005* | 0.002 | 0.006** | 0.007* | 0.007‡ | 0.004‡ | — | 0.104 | 0.046 | 0.026 | 0.023 | 0.058 | 0.077 | 0.031 | 0.044 |

| PBDA | 0.008** | 0.010** | 0.006* | 0.008** | 0.012** | 0.013** | 0.009* | 0.008** | 0.014** | — | 0.104 | 0.066 | 0.075 | 0.069 | 0.128 | 0.081 | 0.070 |

| PBJ | 0.004** | 0.005** | 0.003‡ | 0.003* | 0.005** | 0.008** | 0.005‡ | 0.002 | 0.006** | 0.014** | — | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.045 | 0.079 | 0.025 | 0.012 |

| IGP | 0.004* | 0 | 0.001 | 0 | 0.004* | 0.005‡ | 0.001 | 0 | 0.004‡ | 0.009** | 0.002‡ | — | −0.006 | 0.030 | 0.065 | 0.001 | −0.002 |

| ODL | 0 | −0.001 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | −0.002 | −0.001 | 0.003 | 0.010** | 0.002 | −0.001 | — | 0.005 | 0.047 | −0.021 | −0.02 |

| PEU | 0.003 | 0.005* | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.004* | 0.004 | 0 | 0.001 | 0.007** | 0.009** | 0.006** | 0.004‡ | 0.001 | — | 0.019 | 0.023 | 0.025 |

| BTG | 0.007* | 0.010** | 0.008** | 0.005* | 0.004‡ | 0.004 | 0.009* | 0.005‡ | 0.010** | 0.017** | 0.011** | 0.009* | 0.006‡ | 0.002 | — | 0.051 | 0.064 |

| ABRE | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0 | 0.002 | 0.005‡ | 0.002 | −0.001 | 0.004* | 0.011** | 0.003* | 0 | −0.003 | 0.003 | 0.007* | — | 0.003 |

| BMG | 0.002 | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.003‡ | 0.002 | −0.001 | 0 | 0.006* | 0.009** | 0.002 | 0 | −0.003 | 0.003‡ | 0.008** | 0 | — |

| (b) | |||||||||||||||||

| CARP | — | 0.003 | 0.016 | 0.018 | 0 | 0.118 | 0 | 0.067 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.081 | 0 | 0.015 | 0 | 0 | 0.039 | 0 |

| SMI | 0 | — | 0.124 | 0.022 | 0 | 0.214 | 0 | 0.032 | 0.020 | 0.011 | 0.057 | 0.008 | 0.058 | 0 | 0 | 0.003 | 0 |

| SCI | −0.002 | 0.005 | — | 0.108 | 0.100 | 0 | 0.025 | 0.209 | 0.072 | 0.027 | 0.143 | 0.068 | 0 | 0.005 | 0 | 0.096 | 0.093 |

| MLBU | 0.009 | 0.008 | 0.015 | — | 0 | 0.189 | 0 | 0.033 | 0.037 | 0.033 | 0.072 | 0.024 | 0.055 | 0 | 0 | 0.016 | 0 |

| SCAT | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.001 | — | 0.144 | 0 | 0.044 | 0.024 | 0 | 0.072 | 0 | 0.057 | 0 | 0 | 0.021 | 0 |

| SNI | 0.003 | 0.006 | −0.002 | 0.013 | 0.002 | — | 0.117 | 0.300 | 0.174 | 0.068 | 0.253 | 0.164 | 0.054 | 0.081 | 0.070 | 0.190 | 0.171 |

| CLEM | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.011 | 0.013 | 0.009 | — | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.025 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CRDO | −0.002 | 0.003 | −0.001 | 0.006 | 0 | 0.002 | 0.002 | — | 0.080 | 0.135 | 0.090 | 0.038 | 0.165 | 0 | 0.017 | 0.06 | 0 |

| PTN | 0.018 | 0.003 | 0.024* | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.021 | 0.013 | 0.018 | — | 0.018 | 0.033 | 0 | 0.023 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.008 |

| PBDA | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.007 | −0.007 | 0.003 | 0.014 | −0.005 | 0.013 | — | 0.126 | 0.042 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.031 | 0.015 |

| PBJ | 0.019 | 0.022 | 0.008 | 0.013 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.03* | 0.008 | 0.034* | 0.002 | — | 0.022 | 0.098 | 0.009 | 0.003 | 0 | 0.072 |

| IGP | −0.003 | 0.001 | −0.002 | 0.006 | −0.003 | −0.002 | 0.002 | −0.003 | 0.012 | −0.005 | 0.008 | — | 0.048 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ODL | −0.002 | −0.005 | −0.005 | 0.002 | −0.003 | −0.001 | −0.003 | −0.002 | 0.004 | −0.003 | 0.009 | −0.005 | — | 0 | 0 | 0.027 | 0.073 |

| PEU | 0.002 | 0 | 0 | 0.005 | 0 | 0.004 | −0.006 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.015 | 0.001 | −0.007 | — | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BTG | 0.003 | 0.002 | −0.002 | 0.006 | 0 | 0.004 | −0.004 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.012 | 0.001 | −0.006 | −0.021 | — | 0 | 0 |

| ABRE | 0.002 | −0.002 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.001 | −0.003 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.020 | 0.002 | −0.005 | −0.005 | −0.003 | — | 0.023 |

| BMG | 0.018 | 0.025 | 0.014 | 0.022 | 0.006 | 0.014 | 0.043** | 0.008 | 0.040* | −0.005 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.017 | 0.031* | 0.029 | 0.035* | — |

FST (фST for COI) is below the diagonal, and Jost's Dest_Chao is above the diagonal. Shaded boxes indicate significant differences at P < 0.05 for both nDNA and mtDNA.

For nDNA, comparisons marked with *, ** or ‡ are significant after a false discovery correction is applied. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.0005. For mtDNA, no comparisons were significant after correcting for false discovery, although some were significant at P < 0.01 and 0.0005, and indicated as such.

CARP, Carpinteria, CA; SMI, San Miguel Island, CA; SCI, Santa Cruz Island, CA; MLBU, Malibu, CA; SCAT, Santa Catalina Island; SNI, San Nicholas Island, CA; CLEM, San Clemente Island, CA; CRDO, Islas Coronados, Mx; PTN, Puerto Nuevo, Mx; PBDA, Punta Banda, Mx; PBJ, Punta Baja, Mx; IGP, Isla Guadalupe, Mx; ODL, Laguna Ojo de Liebre, Mx; PEU, Punta Eugenia, Mx; BTG, Bahia Tortugas, Mx; ABRE, Punta Abreojos, Mx; BMG, Bahia Magdalena, Mx.

Microsatellite DNA

We scored 989 individuals across 17 sites for seven nuclear microsatellite loci, with five to 104 alleles per locus, which translated to between two and 23 effective alleles per locus (Table S2, Supporting information). The genotyping error rate, determined by re-genotyping 74 individuals at each locus, ranged from 0.0% to 4.1%, with an average of 2.3% overall (Table S2, Supporting information). We identified two pairs of individuals with identical genotypes and removed one individual of each pair from the data set in order to eliminate the possibility that the same individual was sampled two times. In both cases, identical genotypes were identified within a sampling site. The expected chances of observing true identical twins in this study ranged from 1 × 10−42 to 4.39 × 10−26, while our observed rate was substantially greater, 2 in 989 specimens.

Rarefied allelic richness was similar among sites and ranged from 16.19 to 18.51, while the effective number of alleles ranged from 12.05 to 15.98 (Table 1). Expected heterozygosity (He) was between 0.86 and 0.90, while observed heterozygosity (Ho) exhibited a slightly wider range from 0.76 to 0.87 (Table 1). Tests for linkage disequilibrium (LD) were significant in 20 of 349 comparisons (∼6%) after correcting for multiple tests, and there were no locus-specific patterns. The three sample sites with the highest percentage of LD comparisons correspond to the three sites with the highest levels of kinship, as reported below, suggesting kinship may be high enough at these sites to produce a signal of LD. In general, however, LD is a weak test of family structure, and we found no site-specific patterns across the rest of the sites in the study. There were significant deviations from HWE in 46 of 119 (∼39%) comparisons after correcting for multiple comparisons, but again no sample-specific patterns were observed. micro-checker 2.2.3 (Van Oosterhout et al. 2004) found no evidence of scoring errors due to large allele dropout or stutter; however, six of seven markers showed patterns consistent with null alleles, which are the likely cause of the deviations from HWE (see Ben-Horin et al. 2009). Although the frequencies of these null alleles are low (1.20–6.63% across loci, Table S2, Supporting information), we wanted to be sure they would not affect our results. To test for the impact of null alleles on our results, we used FreeNA (Chapuis & Estoup 2007) to generate alleles for the data set where nulls were expected, re-analysed the data, and our subsequent results and conclusions remained the same. Therefore, we present only analyses with the full original data set.

Significant partitioning of the samples among locations was detected in the microsatellite loci with both a global fixation test (FST = 0.004, P < 0.001) and a global genetic differentiation test (Dest_Chao = 0.03, P < 0.0005). Global partitioning was also detected in analyses of individual loci, with a significant global FST (0.002–0.011, Table S2, Supporting information) and global Dest_Chao (0.030–0.114) at each individual locus, except A110.

We ran pairwise FST and Dest_Chao comparisons for each marker individually, as well as jackknifing across markers, and found the results were fairly consistent throughout these comparisons. Significant pairwise FST comparisons among sampling sites using the microsatellite loci were fairly low, ranging from 0.002 to 0.015, but 71 of 136 comparisons (52%, Table 2) remained significant after correcting for the false discovery rate (Benjamini et al. 2006). As in our mtDNA results, pairwise Dest_Chao comparisons generally were an order of magnitude higher than each respective pairwise FST comparison and ranged from −0.021 to 0.128 (Table 2). The higher magnitude of Dest_Chao compared FST to matches the expectation when heterozygosity is ∼0.9, as it is in this study (Bird et al. 2011).

The sites with the highest mean pairwise FST and Dest_Chao values were in the northern and central Baja California, Mexico region [Puerto Nuevo (PTN), Punta Banda (PBDA), Punta Baja and Bahia Tortugas (BTG)]. These sites also stood out by having the highest proportion of significant differences when compared to the other sites. Three of these four sites also had the highest local FST values (PBDA, BTG and PTN). There was no pattern of IBD in the data set, whether we examined all sampling locations together, or for any of the specific subregions, as described for the mtDNA results (Table S1, Supporting information).

Kinship

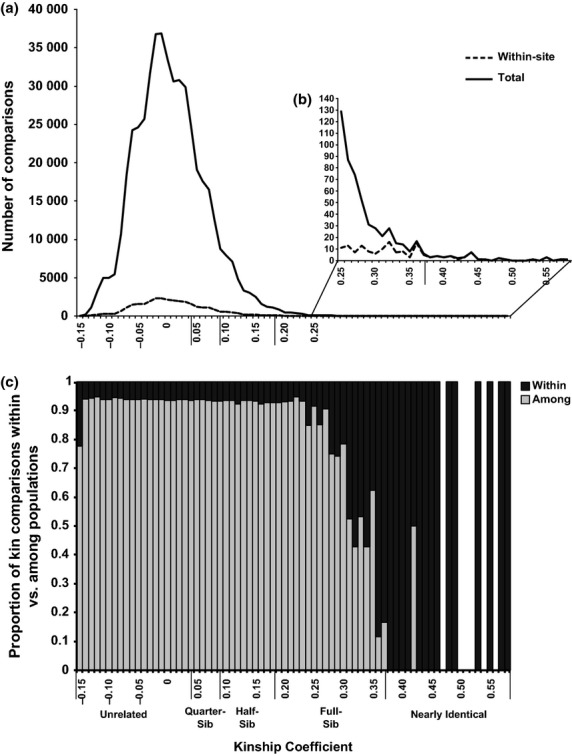

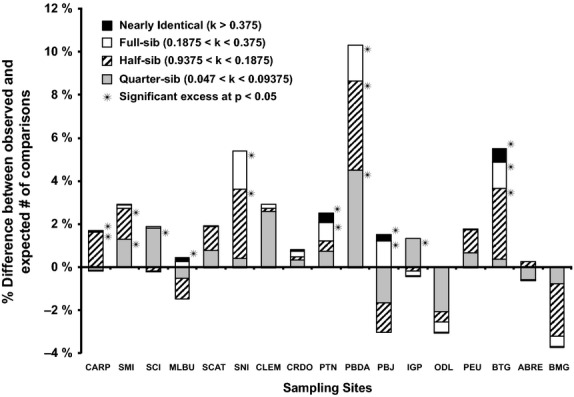

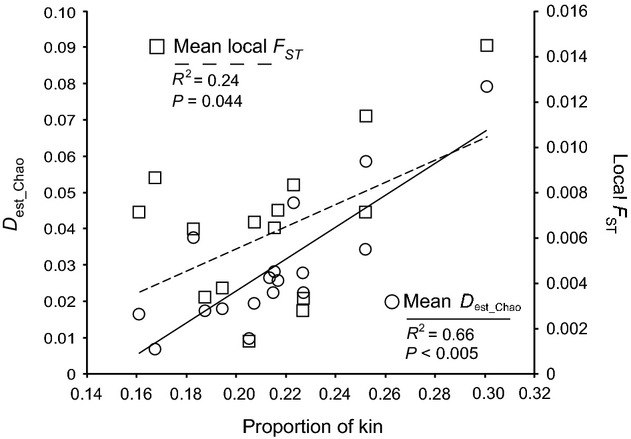

Following the exclusion of lobster specimens with identical genotypes, as well as self-comparisons, kinship coefficients ranged from −0.155 to 0.57 (Fig. 3). The overall mean kinship, which is expected to be zero, was −0.000025 ± 0.00008SE. There was a disparity, however, between the within-site mean kinship (0.003 ± 0.0004) and the among-site mean kinship (−0.0002 ± 0.00009) (Fig. 3). Mean within-site maximum-likelihood estimates of relatedness (r, from ML-Relate) ranged from 0.034 to 0.057 (Table S3, Supporting information) and were significantly correlated with mean kinship values (k) at each site (Table S3, Supporting information, Pearson's r = 0.92, P < 0.0005). Kinship coefficients were significantly greater for within-site than for among-site comparisons (pseudo-F16,988 = 1.39, P = 0.001). In total, 10 of 17 sites had significantly greater numbers of closely related pairs of individuals than expected by chance (P < 0.05) in at least one of four kinship categories: five sites had an excess of individuals in the ‘nearly identical’ category (0.57 > k > 0.375), five sites had an excess in the ‘full-sib’ group (0.375 > k > 0.1875), five sites had an excess in the ‘half-sib’ category (0.1875 > k > 0.09375), and four sites had an excess in the ‘quarter-sib’ bin (0.09375 > k > 0.047) (Fig. 4, Table S3, Supporting information). The proportion of kin in each site was significantly related to mean pairwise FST (R2 = 0.669; F1,16 = 30.333, P < 0.0005) and Dest_Chao (R2 = 0.658; F1,16 = 28.885, P < 0.0005; Fig. 5) for each site as well as to local FST (R2 = 0.243; F1,16 = 4.825, P = 0.044; Fig. 5). These findings are consistent across kinship classes. When we removed the lowest level of kinship (examining only kinship levels equivalent to ‘nearly identical’, ‘full-sib’ and ‘half-sib’), the relationship of both FST (R2 = 0.672; F1,16 = 30.741, P < 0.0005) and Dest_Chao (R2 = 0.658; F1,16 = 28.887, P < 0.0005) with the proportion of kin stayed approximately the same, while the relationship of local FST with the proportion of kin strengthened (R2 = 0.303; F1,16 = 6.526, P = 0.022). The relationships of mean pairwise FST, Dest_Chao and local FST with the proportion of related individuals (r, full- and half-sibs) from ML-Relate were all significant and stronger than the relationships between these summary statistics and proportion of kin (Fig. S1, Supporting information).

Fig. 3.

(a) Line graph depicting the total number of kinship (k) pairwise comparisons for each 0.01 bin of kinship (solid line, total N = 457,652) and the number of within-site kinship comparisons (dashed line, total N = 30,914). (b) Inset of (a), depicting the total number of kinship comparisons (solid line) and the number of within-site comparisons (dashed line) from 0.25 to 0.57 on a separate y-axis that ranges from 0 to 140 comparisons. The majority of these kinship comparisons are between individuals sampled at the same location. (c) Distribution of kinship coefficients divided into 0.01 bins and coloured by the proportion of within-site (dark grey) versus among-site (light grey) comparisons within each 0.01 division. White bars represent levels of kinship that were not found in the data set. Bars on the x-axis represent the divisions between unrelated and related individuals and between each of the four kinship categories we analysed: ‘quarter-sib’, 0.047 < k < 0.09375; ‘half-sib’, 0.09375 < k < 0.1875; ‘full-sib’, 0.1875 < k < 0.375; and ‘nearly identical’, 0.375 < k < 0.57.

Fig. 4.

Histogram of the proportion of kinship observed for each site that is in excess of expected levels due to chance in four kinship categories: ‘quarter-sib’, 0.047 < k < 0.09375; ‘half-sib’, 0.09375 < k < 0.1875; ‘full-sib’, 0.1875 < k < 0.375; and ‘nearly identical’, 0.375 < k < 0.57. Asterisks indicate significant (P < 0.05) differences between the observed and expected proportion of kinship comparisons within that category at that site. Expected kinship levels were constructed using 10 000 permutations of all kinship values across all sites without replacement to generate the distribution of kinship values that should occur if individuals were randomly distributed among sites. The nearly identical bin represents comparisons above full-sibs and is based on our kinship coefficient distribution for comparisons of individuals to themselves. Counts of the actual number of pairwise comparisons at each site that fell within each kinship category are listed in Table S3.

Fig. 5.

Linear regression of mean pairwise Dest_Chao (circles, solid line) and local FST (squares, dashed line) for seven microsatellite loci. Both metrics were regressed on the proportion of within-site kinship comparisons at each site that are significantly (P < 0.05) greater than k = 0.047 (the lower boundary of the four designated kinship categories).

Upwelling

Regions containing persistent, strong upwelling regimes, both across seasons within a year and across all years from 1996 to 2002, were traced from fig. 14 in Zaytsev et al. (2003) and are depicted by dotted lines in Fig. 6a. Three of the four upwelling regions overlap the geographic range of our study and contain four of our sampling locations: Islas Coronados, PTN, PBDA and BTG (Fig. 6a). Three of these four sites (PTN, PBDA and BTG) contain one of the highest four values for mean Dest_Chao, mean local FST and mean kinship. The IWD function applied to this data extrapolates these site-specific metrics across the entire study area, including the unintended extrapolation of Dest_Chao values to ocean areas where adult lobsters do not live, but phyllosoma may be present. Along the Baja California coastal areas containing adult lobsters, all three of the areas with the highest genetic differentiation (Dest_Chao) overlap the regions of strong upwelling intensity (Fig. 6a). The results for mean kinship and local FST were similar, although not shown. Across the geographic extent of our study, we see a significant relationship (R2 = 0.407; F1,16 = 10.296, P = 0.006) between mean kinship at each site and the closest distance between each site and the edge of an upwelling zone [(mean kinship + 1) = −0.005 ln (distance to upwelling + 100 km) + 1.028, Fig. 6b). This relationship holds for mean relatedness (r) versus distance from upwelling as well (Fig. S2, Supporting information).

Fig. 6.

(a) Map of lobster specimen collection locations overlaid with an inverse weighted distance interpolation of mean Dest_Chao values at each site created using the Spatial Analyst extension in arcgis 10. Red coloration represents areas of greatest genetic differentiation, green represents areas of little genetic differentiation, and yellow and orange represent the graded values between these extremes. Mean kinship values at each site showed the same pattern as Dest_Chao, with the highest kinship in red and lowest in green. Dashed lines circle areas of consistently high upwelling intensity (adapted from Zaytsev et al. 2003). There are also areas of high upwelling intensity at Point Conception, and one south of Bahia Magdalena that are not captured by this map. (b) Log-linear regression of mean kinship at each site on the distance (km) to the nearest edge of an area of high upwelling intensity [from (a)].

Discussion

There is accumulating evidence from multiple approaches that larvae rarely reach their full dispersal potential, resulting in a paradigm shift away from the perception that most marine populations are genetically homogenous across broad geographic scales (Jones et al. 1999; Swearer et al. 1999, 2002; Mora & Sale 2002; Grantham et al. 2003; Taylor & Hellberg 2003; Marko 2004; Cowen et al. 2006; Becker et al. 2007; López-Duarte et al. 2012). However, this evidence has come exclusively from species with short to modest larval periods (1–60 days). Even among species with modest PLD, there are just a few striking examples of broad populations with no genetic substructure across their full range. For example, reef fishes Myripristis jacobis in the Atlantic Ocean (Bowen et al. 2006), Lutjanus kasmira in the Central Pacific and Eastern Indian Oceans (Gaither et al. 2010) and Acanthurus nigrofuscus in the Pacific (Eble et al. 2011) all exhibit genetic homogeneity across thousands of kilometres (up to 12 000 km). Dispersal potential is assumed to be great in species with very long PLDs (>120 days), and population genetic surveys of such species to date have revealed little population structuring across broad geographic scales (Ovenden et al. 1992; Silberman et al. 1994; Thompson et al. 1996; Tolley et al. 2005; García-Rodríguez & Perez-Enriquez 2006; Inoue et al. 2007; Horne et al. 2008; Reece et al. 2011). When genetic discontinuities have been observed in species with long PLD, they have invariably corresponded with known biogeographic barriers, or oceanographic transitions (Palero et al. 2008; Babbucci et al. 2010; Chow et al. 2011).

In contrast to the intuitive expectation that Panulirus interruptus, with a minimum PLD of 240 days, would be genetically homogenous across its entire 1400-km range along the west coast of North America, we found slight, but significant genetic structuring among several sampling locations throughout Mexico and Southern California (Table 2). This finding contrasts with previous work that did not detect population structure in P. interruptus throughout Baja California, Mexico, using mtDNA RFLPs (García-Rodríguez & Perez-Enriquez 2006). Notably, lobsters do not exhibit a genetic break across Punta Eugenia, a faunal boundary for rocky intertidal species (Valentine 1966; Blanchette et al. 2008; Gaines et al. 2009) and a phylogenetic break for a number of coastal fishes (Bernardi et al. 2003). Nor does the overall pattern of genetic differentiation in P. interruptus correspond to the Northern, Central and Southern regional population subdivision within Baja predicted by Perez-Enriquez et al. (2001). Rather, genetically differentiated sites are nested within a greater area of undifferentiated sites (Fig. 6a). Specifically, some sites exhibit no genetic differentiation across the 1400-km species range, whereas other sites are differentiated from the majority of sampled sites, and there is no signal of IBD in either the mtDNA or the nuclear microsatellite markers across multiple spatial scales (Table S1, Supporting information). Similar patterns of genetic differentiation among proximate sites have been shown in species with shorter larval developmental periods (reviews by Larson & Julian 1999; Hedgecock et al. 2007; Riginos et al. 2011; Toonen & Grosberg 2011), but have not been reported for a species with such a long PLD as this one. Additionally, P. interruptus has equivalent or greater levels of genetic substructure than other species occurring in this same region (Selkoe et al. 2010), despite a PLD that is an order of magnitude higher.

The term ‘chaotic genetic patchiness’ was coined (Johnson & Black 1982, 1984) to describe ephemeral, finely spatio-temporal patterns of genetic structure generated by variation in the larval pool, recruitment and natural selection, which are counteracted in the long-term by dispersal and gene flow (Toonen & Grosberg 2011). Much of the difficulty in interpreting these unexpected patterns in genetic differentiation is due to the nature of FST as a summary statistic. Significant structure among populations may be a result of differences in effective population size (and corresponding genetic drift), demographic or colonization history, migration or some combination of these factors, especially for populations that may not have reached migration–drift equilibrium. Direct interpretation of summary statistics (FST, Dest_Chao) in the context of gene flow can be problematic (reviewed by Lowe & Allendorf 2010; Hart & Marko 2010; Marko & Hart 2011; Bird et al. 2011; Karl et al. 2012), especially in species such as P. interruptus, with highly fecund individuals and a potential for reproductive skew (Eldon & Wakeley 2009). For the many marine species with high fecundity and a type III survivorship curve, an independent test can help determine whether gene flow is the primary driver resulting in the observed population structure (Hart & Marko 2010; Lowe & Allendorf 2010).

Here, kinship (Loiselle et al. 1995) enriches our understanding of the drivers underlying significant differences in FST among sites. The pattern of chaotic genetic patchiness in P. interruptus evident in the FST and Dest_Chao analyses seems to be primarily a result of the nonrandom occurrence of closely related lobsters within sample sites. Across all sites, lobsters were more closely related within sites than between sites, and at the majority of sites, we found significantly greater than expected levels of kinship between adult lobsters (Fig. 4). Moreover, the proportion of kin found at each site accounts for the majority of the variation in the sites’ genetic differentiation: the most greatly differentiated sampling sites have the highest proportion of kin (Fig. 5).

One potential scenario that could generate high proportions of kin within sites is recruitment pulses of related individuals. The simplest explanation for this phenomenon is that larvae released together stay together throughout dispersal and recruitment (kin aggregation). However, this pattern would also result from extreme differential reproductive success among individuals, so that a recruiting cohort is entirely made up of offspring from only a few individuals (sweepstakes recruitment, Hedgecock 1986, 1994a,b). Sweepstakes recruitment could also generate the star-shaped pattern of our mtDNA haplotype network (Fig. 2, Fig. S3, Supporting information), although this pattern could also be indicative of a recent population expansion. Previous kinship analyses have detected high levels of relatedness within cohorts of larval recruits in both fishes (Planes et al. 2002; Pujolar et al. 2006; Selkoe et al. 2006; Buston et al. 2009; Bernardi et al. 2012) and invertebrates (Veliz et al. 2006), which supports both the hypothesis of kin aggregation throughout development and/or the hypothesis of sweepstakes reproduction. Unfortunately, we could not directly test these alternatives in P. interruptus because we did not have samples of new recruits. Nevertheless, given the size selectivity of lobster traps, and the intense fishing pressure for lobster depressing the age range (Iacchei et al. 2005; Kay & Wilson 2012), it is possible that our samples are largely made up of single year classes consisting of closely related individuals recruiting together by one of these aforementioned mechanisms. To our knowledge, this study is the first documented case of kin aggregation in the adult population of a marine species with planktonic larvae, although kin aggregation in recruits has been reported. Previous studies that have looked at only kin relationships among adults, rather than among cohorts of recruits, have found no evidence of kin aggregation in marine species (Avise & Shapiro 1986; Kolm et al. 2005; Buston et al. 2007; Palm et al. 2008; Andrews et al. 2010; Berry et al. 2012). Consequently, kin aggregation is generally assumed to be a transient phenomenon limited to newly settled recruits, with little detectable signal in adult populations due to multiple source populations of recruits, changes in reproductive success and differential juvenile mortality (Kordos & Burton 1993; Moberg & Burton 2000; Flowers et al. 2002; Planes et al. 2002; Selkoe et al. 2006; Buston et al. 2009).

High levels of within-site kinship could also be driven by a temporally stable pattern of self-recruitment, either through larval retention or through larval dispersal with subsequent recruitment back to the natal site. The prospect that larvae stay in the plankton for 240–330 days and return to settle near their site of release seems unlikely at first. However, the site-specific kinship patterns in our data match theoretical predictions for a species that has evolved a long PLD to avoid predation during the larval phase rather than to facilitate broad dispersal of larvae (Strathmann et al. 2002). The extended PLD may enable phyllosoma to disperse far offshore, into a pelagic environment that is favorable for the survival of unprotected larval-stage individuals (Strathmann et al. 2002). Late-stage lobster larvae (pueruli) are fast swimmers (Serfling & Ford 1975) and may utilize strong upwelling regimes to return and settle near their natal site after dispersing offshore. If this behaviour is selectively advantageous, we would expect to observe enhanced local recruitment regardless of PLD. Furthermore, local recruitment should be more pronounced at sites with strong, persistent upwelling (Fig. 6b).

The four sites with the highest proportion of kin in Baja California, Mexico, are located in areas of persistent upwelling (Zaytsev et al. 2003; Fig. 6a). Although upwelling was initially proposed as a mechanism for advecting recruits away from coastal areas (Roughgarden et al. 1988), subsequent studies have questioned that prediction (e.g. Shanks & Brink 2005; Morgan et al. 2009; Morgan & Fisher 2010; reviewed in Shanks & Shearman 2009). Genetic studies have proven equivocal in this regard: some have found reduced genetic substructure between populations in years with greater cumulative upwelling (e.g. Flowers et al. 2002; Barshis et al. 2011), and others have found upwelling dynamics to be insufficient to explain temporal and spatial genetic patterns (e.g. Toonen & Grosberg 2011). Passive larval dispersal models indicate that the effects of upwelling may depend on whether larvae stay near the surface (upwelling advects larvae offshore) or undergo regular migrations to depth (upwelling delivers larvae to the coast) (Byers & Pringle 2006; Marta-Almeida et al. 2006).

Spiny lobsters are known to have relatively large larvae capable of dynamic movement. Both the phyllosoma and puerulus stages show evidence of active movement in the pelagos, with phyllosoma exhibiting diel vertical migrations as well as horizontal movements (Kittaka 1994; Chiswell & Booth 1999; Phillips et al. 2006; Butler et al. 2011), and pueruli demonstrating rapid swimming, navigation towards the coast and habitat settlement preferences (Serfling & Ford 1975; Jeffs et al. 2005; Phillips et al. 2006). In P. interruptus specifically, Pringle (1986) found both geographic and depth stratification of different stages of both phyllosoma and pueruli collected during yearly larval tows in the California Current Ecosystem, suggesting active ontogenetic shifts in larval depth preference. Incorporating such larval behaviours into biophysical models of dispersal in a congeneric species, Panulirus argus, resulted in a 60% or greater decrease in the average distance a larva is predicted to settle from its release site compared with simulations of larvae that remain on the surface (Butler et al. 2011). Lobsters in the California Current Ecosystem rely on kelp forest habitat for survival: P. interruptus has much higher relative survival rates in the presence of kelp than in surrounding areas where kelp is absent (Mai & Hovel 2007). Given the ephemeral dynamics of kelp forest habitat (Reed et al. 2006) and the high variability in ocean conditions in this region, these lobsters may have evolved similarly complex behaviours as their congeners to increase successful local recruitment despite their extremely long PLD (e.g. Shanks & Eckert 2005).

Conclusion

Here, we present a novel approach to understand contemporary drivers of population differentiation in systems with high gene flow. In isolation, the population-level data present a commonly documented scenario among marine species: no evidence for any particular regional separation or isolation-by-distance patterns, but low and significant pairwise differences among populations. While the agreement between nuclear and mitochondrial markers confirms that the results are not due to statistical artifact, the nature of F-statistics leaves us without a clear indication of what is driving the pattern of genetic differentiation. The addition of kinship analyses reveals how alleles are shared between individuals, rather than just among populations, and provides an independent test of the hypothesis that population genetic structure as measured by F-statistics is a result of population connectivity. In this case, the majority of locations contained an excess of closely related individuals. This supports the inference that either self-recruitment or some form of coordinated larval delivery is driving population-level genetic differences in a species that would be expected to be broadly dispersive throughout its range, given its extremely long PLD. In combination with regional oceanographic data and larval dispersal behaviour, kinship analyses provide evidence for a mechanism of differentiation in an otherwise murky population genetic data set. The ability to directly test hypotheses about what drives population genetic substructure in high gene-flow species by independent means, such as kinship or coalescent analyses, provides greater confidence in the underlying causes of population substructure than summary statistics alone. As the ease of developing greater numbers of genetic markers increases, individual-based analyses such as relative kinship indices can provide a valuable complement for understanding patterns in traditional population genetics data sets.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Scott Aalbers, Stevie Adams, Eugenio Carpizo, Jack Engle, Lauren Garske, Eddie Hernandez, David Kushner, Kacy Lafferty, Thien Mai, Kathy Ann Miller, Arturo Ramirez Valdez, Jorge A. Rosales Casian, Patrick (Farfol) Robinson, Derek Smith, Armando Vega-Velázquez, Talib Wahab and Joe Wible for their assistance with sample collections. This manuscript benefited greatly from discussions with members of the ToBo laboratory, especially Kimberly Andrews, Kimberly Conklin, Joseph DiBattista, Iria Fernández-Silva, Michelle Gaither, Joseph O'Malley, Jon Puritz, Derek Skillings and Zac Forsman, as well as Megan Donahue, Steve Karl, Jonatha Giddens, Kelvin Gorospe, Fred Allendorf, Nils Ryman, Sheldon Plentovich and the Garza laboratory group at NMFS SWFSC. Special thanks to Kathy Ann Miller for taking the risk and giving MJI an opportunity to work on P. interruptus genetic connectivity. Thanks to Dr. Maria Pia Chaparro Lanfranco and the Donahue Lab for assistance with ArcGIS graphics, Justin Stopa with matrix parsing, Dr. Seastar for analysis vetting and Brian Bowen and Mike Hart for very helpful comments on an earlier draft. Many thanks to Shaobin Hou and the ASGPB and Amy Eggers and the HIMB EPSCoR Core Genetics Facility for sequencing of all the mtDNA data. We greatly appreciate the feedback of Giacomo Bernardi and the three anonymous reviewers, whose comments greatly improved the text. This project was partially supported by the University of California Coastal Environmental Quality Initiative, the Offield Family Foundation (MI), an EPA STAR Fellowship (MI), the Jessie D. Kay Research Grant (MI), National Marine Sanctuaries MOA 2005-008/66832 (KAS, MI and RJT), National Sea Grant NA06RG0142, project R/F-177 to R. Grosberg & RJT and NOAA Project R/HE-6 (MI and RJT), which is sponsored by the University of Hawai'i Sea Grant College Program, SOEST, under institutional grant no. NA09OAR4171060 from NOAA Office of Sea Grant, Department of Commerce. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and may not reflect the views of the EPA, NOAA or any of their subagencies. This is contribution number 1546 from the Hawai'i Institute of Marine Biology, no. 2013-002 from the University of Hawai'i at Ma-1.7 \barnoa Department of Biology, no. 8897 from the School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology and no. UNIHI-SEAGRANT-JC-09-53 from the University of Hawai'i Sea Grant College Program.

Data accessibility

DNA sequences: GenBank accession nos: KC775458–KC775695.

Sample ID's, collection locations, microsatellite genotypes and an mtDNA COI sequence alignment: Dryad entry doi: 10.5061/dryad.j6332.

Supporting information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article.

Table S1 Isolation by distance (IBD) results from Mantel tests conducted in genodive 2.0b20 to examine patterns of genetic differentiation across multiple spatial scales based on sampling locations: all sites, only California sites, only Mexico sites, only continental sites, and only island sites.

Table S2 Locus-specific diversity indices and FST values as calculated in genodive for each of the seven nuclear microsatellite loci, and null allele frequency for each microsatellite locus as calculated in ML-Relate.

Table S3 Comparison of ML-Relate calculations of relatedness (r) and genodive calculations of kinship for each sampling location.

Fig. S1 Linear regression of mean pairwise local FST (squares, dashed line) and Dest_Chao (circles, solid line) at each site on the combined proportion of full- and half-sibs as determined in ML-Relate for seven microsatellite loci.

Fig. S2 Log-linear regression of mean relatedness (r) at each site on the distance (km) to the nearest edge of an area of high upwelling intensity (from Fig. 6a).

Fig. S3 Median-joining network for Panulirus interruptus mtDNA, constructed using 454 base pairs of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (COI) from each of 931 individuals in the program network.

References

- Andrews KR, Karczmarski L, Au WL, et al. Rolling stones and stable homes: social structure, habitat, diversity and population genetics of the spinner dolphin (Stenella longirostris. Molecular Ecology. 2010;19:732–748. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avise JC, Shapiro DY. Evaluating kinship of newly settled juveniles within social groups of the coral reef fish Anthias squamipinnis. Evolution. 1986;40:1052–1059. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1986.tb00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbucci M, Buccoli S, Cau A, et al. Population structure, demographic history, and selective processes: contrasting evidences from mitochondrial and nuclear markers in the European spiny lobster Palinurus elephas (Fabricius, 1787) Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2010;56:1040–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balding DJ, Nichols RA. A method for quantifying differentiation between populations at multi-allelic loci and its implications for investigating identity and paternity. Genetica. 1995;96:3–12. doi: 10.1007/BF01441146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandelt H, Forster P, Röhl A. Median-joining networks for inferring intraspecific phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1999;16:37–48. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barshis DJ, Sotka EE, Kelly RP, et al. Coastal upwelling is linked to temporal genetic variability in the acorn barnacle Balanus glandula. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2011;439:139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Becker BJ, Levin LA, Fodrie FJ, McMillan PA. Complex larval connectivity patterns among marine invertebrate populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:3267–3272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611651104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellquist LF, Lowe CG, Caselle JE. Fine-scale movement patterns, site fidelity, and habitat selection of ocean whitefish (Caulolatilus princeps. Fisheries Research. 2008;91:325–335. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Horin T, Iacchei M, Selkoe KA, Mai TT, Toonen RJ. Characterization of eight polymorphic microsatellite loci for the California spiny lobster, Panulirus interruptus and cross-amplification in other achelate lobsters. Conservation Genetics Resources. 2009;1:193–197. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Krieger AM, Yekutiele D. Adaptive linear step-up procedures that control the false discovery rate. Biometrika. 2006;93:491–507. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi G, Findley L, Rocha-Olivares A. Vicariance and dispersal across Baja California in disjunct marine fish populations. Evolution. 2003;57:1599–1609. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardi G, Beldade R, Holbrook SJ, Schmitt RJ. Full-sibs in cohorts of newly settled coral reef fishes. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e44953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry O, England P, Marriott RJ, Burridge CP, Newman SJ. Understanding age-specific dispersal in fishes through hydrodynamic modeling, genetic simulations and microsatellite DNA analysis. Molecular Ecology. 2012;21:2145–2159. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird CE, Smouse PE, Karl SA, Toonen RJ. Detecting and measuring genetic differentiation. In: Koenemann S, Held C, Schubart C, editors. Crustacean Issues: Phylogeography and Population Genetics in Crustacea. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press; 2011. pp. 31–55. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchette CA, Miner CM, Raimondi PT, Lohse D, Heady KEK, Broitman BR. Biogeographic patterns of rocky intertidal communities along the Pacific coast of North America. Journal of Biogeography. 2008;35:1593–1607. [Google Scholar]

- Blouin MS. DNA-based methods for pedigree reconstruction and kinship analysis in natural populations. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2003;18:503–511. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen BW, Bass AL, Muss AJ, Robertson DR. Phylogeography of two Atlantic squirrelfishes (family Holocentridae): exploring links between pelagic larval dispersal and population connectivity. Marine Biology. 2006;149:899–913. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury IR, Laurel B, Snelgrove PVR, Bentzen P, Campana SE. Global patterns in marine dispersal estimates: the influence of geography, taxonomic category and life history. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B. 2008;275:1803–1809. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.0216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buston PM, Bogdanowicz SM, Wong A, Harrison RG. Are clownfish groups composed of close relatives? An analysis of microsatellite DNA variation in Amphiprion percula. Molecular Ecology. 2007;16:3671–3678. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buston PM, Fauvelot C, Wong MYL, Planes S. Genetic relatedness in groups of the humbug damselfish Dascyllus aruanus: small, similar-sized individuals may be close kin. Molecular Ecology. 2009;18:4707–4715. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2009.04383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MJ, Paris CB, Goldstein JS, Matsuda H, Cowen RK. Behavior constrains the dispersal of long-lived spiny lobster larvae. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2011;422:223–237. [Google Scholar]

- Byers J, Pringle J. Going against the flow: retention, range limits and invasions in advective environments. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 2006;313:27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Carson HS, Cook GS, López-Duarte PC, Levin LA. Evaluating the importance of demographic connectivity in a marine metapopulation. Ecology. 2011;92:1972–1984. doi: 10.1890/11-0488.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartamil DP, Sepulveda CA, Wegner NC, Aalbers SA, Baquero A, Graham JB. Archival tagging of subadult and adult common thresher sharks (Alopias vulpinus) off the coast of southern California. Marine Biology. 2011;158:935–944. doi: 10.1007/s00227-010-1620-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao A, Shen T-J. 2009. SPADE (Species Prediction and Diversity Estimation). Available at: http://chao.stat.nthu.edu.tw/softwareCE.html (accessed 20 July 2012)

- Chapuis MP, Estoup A. Microsatellite null alleles and estimation of population differentiation. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2007;24:621–631. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez EA, Gorostieta M. Bioeconomic assessment of the red spiny lobster fishery of Baja California, Mexico. California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigation Report. 2010;51:153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Chiswell SM, Booth JD. Rock lobster Jasus edwardsii larval retention by the Wairarapa Eddy off New Zealand. Marine Ecology Progress Series. 1999;183:227–240. [Google Scholar]

- Chow S, Jeffs A, Miyake Y, et al. Genetic Isolation between the Western and Eastern Pacific Populations of Pronghorn Spiny Lobster Panulirus penicillatus. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e29280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie MR, Johnson DW, Stallings CD, Hixon MA. Self-recruitment and sweepstakes reproduction amid extensive gene flow in a coral-reef fish. Molecular Ecology. 2010;19:1042–1057. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke KR, Warwick RM. Change in Marine Communities: An Approach to Statistical Analysis and Integration. 2nd edn. Plymouth: PRIMER-E; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cowen RK, Paris CB, Srinivasan A. Scaling of connectivity in marine populations. Science. 2006;311:522–527. doi: 10.1126/science.1122039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D. jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nature Methods. 2012;9:772. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Rambaut A, Shapiro B, Pybus OG. Bayesian coalescent inference of past population dynamics from molecular sequences. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2005;22:1185–1192. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eble JA, Rocha LA, Craig MT, Bowen BW. Not all larvae stay close to home: insights into marine population connectivity with a focus on the brown surgeonfish (Acanthurus nigrofuscus. Journal of Marine Biology. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/518516. Article ID 518516, 12pp. doi 10.1155/2011/518516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldon B, Wakeley J. Coalescence Times and FST under a skewed offspring distribution among individuals in a population. Genetics. 2009;181:615–629. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.094342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L, Smouse PE, Quattro JM. Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among DNA haplotypes: application to human mitochondrial DNA restriction data. Genetics. 1992;131:479–491. doi: 10.1093/genetics/131.2.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S. arlequin (version 3.5): an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evolutionary Bioinformatics. 2005;1:47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faurby S, Barber PH. Theoretical limits to the correlation between pelagic larval duration and population genetic structure. Molecular Ecology. 2012;14:3419–3432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flowers JM, Schroeter SC, Burton RS. The recruitment sweepstakes has many winners: genetic evidence from the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus purpuratus. Evolution. 2002;56:1445–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foll M, Gaggiotti OE. Identifying the environmental factors that determine the genetic structure of populations. Genetics. 2006;174:875–891. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.059451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaines SD, Lester SE, Eckert G, Kinlan BP, Sagarin RD, Gaylord B. Dispersal and geographic ranges in the sea. In: Roy K, Witman JD, editors. Marine Macroecology. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press; 2009. pp. 227–249. [Google Scholar]

- Gaither MR, Toonen RJ, Robertson DR, Planes S, Bowen BW. Genetic evaluation of marine biogeographic barriers: perspectives from two widespread Indo-Pacific snappers (Lutjanus kasmira and Lutjanus fulvus. Journal of Biogeography. 2010;37:133–147. [Google Scholar]

- García-Rodríguez FJ, Perez-Enriquez R. Genetic differentiation of the California spiny lobster Panulirus interruptus (Randall, 1840) along the west coast of the Baja California Peninsula, Mexico. Marine Biology. 2006;148:621–629. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach G, Atema J, Kingsford MJ, Black KP, Miller-Sims V. Smelling home can prevent larval dispersal of reef fish larvae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:858–863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606777104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudet J. 2001. FSTAT, a program to estimate and test gene diversities and fixation indices (version 2.9.3). Available at: http://www2.unil.ch/popgen/softwares/fstat.htm (accessed 21 August 2012)

- Grantham BA, Eckert GL, Shanks AL. Dispersal potential of marine invertebrates in diverse habitats. Ecological Applications. 2003;13:S108–S116. [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast and accurate method to estimate large phylogenies by maximum-likelihood. Systematic Biology. 2003;52:696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy OJ, Vekemans X. SPAGeDi: a versatile computer program to analyse spatial genetic structure at the individual or population levels. Molecular Ecology Notes. 2002;2:618–620. [Google Scholar]

- Hart MW, Marko B. It's about time: divergence, demography, and the evolution of developmental modes in marine invertebrates. Integrative and Comparative Biology. 2010;50:643–661. doi: 10.1093/icb/icq068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock D. Is gene flow from pelagic larval dispersal important in the adaptation and evolution of marine invertebrates? Bulletin of Marine Science. 1986;39:550–564. [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock D. Does variance in reproductive success limit effective populations sizes of marine organisms? In: Beaumont AR, editor. Genetics and Evolution of Aquatic Organisms. London, UK: Chapman and Hall; 1994a. pp. 122–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock D. Temporal and spatial genetic structure of marine animal populations in the California Current. California Cooperative Oceanic Fisheries Investigations Reports. 1994b;35:73–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock D, Barber PH, Edmands S. Genetic approaches to measuring connectivity. Oceanography. 2007;20:70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick PW. Highly variable loci and their interpretation in evolution and conservation. Evolution. 1999;53:313–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1999.tb03767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick PW. A standardized genetic differentiation measure. Evolution. 2005;59:1633–1638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hey J, Nielsen R. Integration within the Felsenstein equation for improved Markov chain Monte Carlo methods in population genetics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:2785–2790. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611164104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hey J, Wakeley J. A coalescent estimator of the population recombination rate. Genetics. 1997;145:833–846. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.3.833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickerson MJ, Stahl EA, Lessios HA. Test for simultaneous divergence using approximate Bayesian computation. Evolution. 2006;60:2435–2453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne JB, van Herwerden L, Choat JH, Robertson DR. High population connectivity across the Indo-Pacific: congruent lack of phylogeographic structure in three reef fish congeners. Molecular Phylogenetics & Evolution. 2008;49:629–638. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR. Island models and the coalescent process. Molecular Ecology. 1998;7:413–418. [Google Scholar]

- Iacchei M, Robinson P, Miller KA. Direct impacts of commercial and recreational fishing on spiny lobster, Panulirus interruptus, populations at Santa Catalina Island, California, United States. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 2005;39:1201–1214. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue N, Watanabe H, Kojima S, Sekiguchi H. Population structure of Japanese spiny lobster Panulirus japonicus inferred by nucleotide sequence analysis of mitochondrial COI gene. Fisheries Science. 2007;73:550–556. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffs AG, Montgomery JC, Tindle CT. How do spiny lobster post-larvae find the coast? New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 2005;39:605–617. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW. The larval development of the California spiny lobster Panulirus interruptus (Randall) with notes on Panulirus gracilis Streets. Proceedings of the California Academy of Science. 1956;29:1–19. [Google Scholar]