Abstract

The decline of the immune system appears to be an intractable consequence of aging, leading to increased susceptibility to infections, reduced effectiveness of vaccination and higher incidences of many diseases including osteoporosis and cancer in the elderly. These outcomes can be attributed, at least in part, to a phenomenon known as T cell replicative senescence, a terminal state characterized by dysregulated immune function, loss of the CD28 costimulatory molecule, shortened telomeres and elevated production of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Senescent CD8 T cells, which accumulate in the elderly, have been shown to frequently bear antigen specificity against cytomegalovirus (CMV), suggesting that this common and persistent infection may drive immune senescence and result in functional and phenotypic changes to the T cell repertoire. Senescent T cells have also been identified in patients with certain cancers, autoimmune diseases and chronic infections, such as HIV. This review discusses the in vivo and in vitro evidence for the contribution of CD8 T cell replicative senescence to a plethora of age-related pathologies and a few possible therapeutic avenues to delay or prevent this differentiative end-state in T cells. The age-associated remodeling of the immune system, through accumulation of senescent T cells has far-reaching consequences on the individual and society alike, for the current healthcare system needs to meet the urgent demands of the increasing proportions of the elderly in the US and abroad.

Keywords: telomere, telomerase, T cells, immune, human, latent infection, aging, HIV/AIDS, immunosenescence, replicative senescence

Introduction

For the first time in history, older adults constitute the fastest growing population in the world. Projections indicate that by 2025 the cohort over age 65 will be increasing 3.5 times as rapidly as the total population [1] and the proportion of individuals age 60 years and older, which accounted for 10% of the world population in 2000, will increase to approximately 22% of the world population by 2050. Consequently, scientific research on age-related maladies needs to rapidly progress to meet the medical and health-related needs of the progressively increasing elderly population. Moreover, in order to develop appropriate preventative and therapeutic strategies, it is essential that we understand the underlying biological mechanisms that contribute to age-related diseases

Aging is a highly complex and continuous process that affects almost all organ systems, causing molecular and physiological changes, both qualitatively and quantitatively. With age, the immune systems undergoes an extensive but gradual process of remodeling dictated by both genetic and intrinsic events, such as the shrinking of the thymus, and environmental factors, primarily mediated by the lifetime encounters of the body to foreign antigens. These factors synergize with age and result in major alterations in immune function that have been implicated in multiple deleterious outcomes.

It is generally recognized that the function of the immune system declines with age, a process characterized by distinct and dramatic changes on both a cellular and systemic level. This so-called immunosenescence is associated with increased incidence of age-related pathologies, such as osteoporosis, Alzheimer’s disease, cancer and autoimmune disorders [2–5]. Older persons also have an impaired response to vaccinations, which have an efficacy of only 30–40% in this population [6]. In addition to the blunted immune response to vaccination intended to prevent infections, older persons show reduced ability to fight actual infections. Indeed, according to the United States Centers of Disease Control influenza and pneumonia rank as the fifth leading cause of death in persons over the age of 65 [7]. There is also evidence that aging affects the hematopoietic stem cell population; bone marrow from older donors fails to fully reconstitute the immune system of transplant recipients [8]. Morbidity and the prolonged duration of illness are also substantially increased with age. Interestingly, more than 50 years ago, the late Dr. Roy Walford, a pioneer of aging research and caloric restriction studies, proposed that chronological aging is directly related to dysfunctions in immunological processes and thus leads to age-related pathologies [9, 10]. This “immunologic theory of aging” has been confirmed more recently, in longitudinal studies of elderly people, which document significant correlations between specific immune features and all-cause mortality [11].

Immunosenescence describes a multifaceted and dynamic pattern of changes within the immune system during aging, leading to defects in both adaptive and innate immunity. One of the most important age-related immune changes is the impaired generation of primary CD8 T cell responses against infection and reduced vaccine efficacy, documented in mice [10, 12–15], rhesus macaques [16], and humans (reviewed in [17]). Other major alterations that characterize immunosenescence include the reduced number and impaired function of hematopoietic stem cells, diminished amount of circulating naïve T cells, inverted CD4/CD8 ratio and increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNFα [18]. There is also a shift from Th1 to Th2 cytokine profiles following T cell activation, which may shift the balance between humoral and cell-mediated immune responses. This altered cytokine profile is likely due to an increased ratio of memory to naive T cells [19, 20]. Another dramatic change observed in the elderly compared to the young is the dramatically reduced T cell production of IL-2 [21], an observation consistent with data from senescent T cell cultures. Although the number of T cell receptors (TCRs) at the individual cell level does not to decline with age, the TCR signal transduction pathways are significantly altered, resulting in impaired transcription of key effector T cell genes [22]. Phosphorylation of critical STAT proteins involved in T cell maintenance is also reduced or delayed in T cells from 90 year-old individuals, a further indication of age-associated T cells defects [23]. Age-related changes within the immune system, as with other complicated diseases and disorders, does not occur at the same pace in all components, or among different individuals, and is strongly influenced by environmental, genetic and epigenetic factors that ultimately shape the severity and magnitude of the dysfunction.

Arguably, the most significant age-related change in the human immune system is the quality and phenotype of the CD8 or so-called cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) subset. With age and in chronic infections such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the majority of CD8 T cells become antigen-experienced and acquires a dysregulated, pro-inflammatory phenotype. These late-differentiated CD8 T cells possess many features of cellular replicative senescence that have been characterized in long-term in vitro cultures [24].

Replicative senescence refers to the process by which normal somatic cells reach an irreversible stage of cell cycle arrest following multiple rounds of replication; this end stage is associated with marked changes in gene expression and function [25]. The parallel phenotypic and functional changes documented in T cells from aged individuals and those observed in T cells driven to replicative senescence in vitro suggests that the in vitro replicative senescence experimental system can be exploited further to elucidate the various factors that contribute to and that may modulate human immunosenescence. Currently, it is known that among the prominent causal agents of T cell replicative senescence in vivo are persistent viruses and tumor antigens.

Several excellent discussions of inflammation and its role in immunosenescence and aging have been covered by other reviews [18, 26, 27]. Here, we will first briefly summarize the main features of the immune system, then discuss the process of T cell replicative senescence and telomerase/telomere dynamics. We will follow with a summary of the current research bridging senescent T cells to several age-related pathologies. Finally the review will conclude with a few lingering, but significant, questions and suggested avenues for future research.

Immunology basics

The primary purpose of the immune system is to maintain and protect our health, by fighting off the glut of pathogens we encounter throughout our lifetime. There are two components of immunity. The innate system comprised of natural killer (NK) cells, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and complement factors, functions relatively non-specifically, but rapidly and efficiently. This immune compartment serves as the first line of defense against environmental pathogens. By contrast, the adaptive component, comprised of T and B cells, requires more time to mount a biochemical response, but utilizes extremely specific targeting to eliminate foreign invaders. Importantly, adaptive immunity allows for the development of immunological memory that is a crucial in both preventing recurring infection by the same strain of pathogen and for the prophylactic effects of vaccination. The innate and adaptive immune cells respond in concert through extensive crosstalk between the two systems. For example, cytokines secreted by different immune cells modulate the activity of innate and adaptive immune cells. Furthermore, the adaptive immune response begins its assault only after it has received signals from the innate component, and cells of the innate system are instructed by the adaptive immune compartment to eliminate weakened or injured pathogens and to clear cell debris. These evolution-driven, complementary components of the human immune system normally provide adequate protection against most bacteria, viruses, and parasites present in the environment.

The key mediators of the adaptive immune response are lymphocytes. T cells, along with B cells, derive from hematopoietic stem cells found in the bone marrow. Through a series of recombination events of variable and constant gene segments encoding different V, D, and J regions, a receptor molecule is formed that is unique to that cell [28]. In this way, a hundred different gene segments can create thousands of distinct receptor chains. Moreover, greater diversity is achieved by pairing two different chains encoded by different genes—in T cells, the chains are the α and β chain—to form a functional antigen receptor. As a result, an astonishing 108 different specificities may be generated to recognize the diverse epitopes of foreign antigens, enabling the immune system to respond to the myriad of different epitopes characterizing unique pathogens [29, 30]. After the cells undergo these intricate gene recombination events and passing through stringent selection tests within the thymic microenvironment, to eliminate inadequate or self-recognizing thymocytes, mature T cells then emigrate out of the thymus into peripheral tissue.

Activation and Clonal Expansion of lymphocytes

Induction of a primary adaptive immune response usually begins when antigen-presenting cells (APC) such as dendritic cells (DC) of the innate immune system engulf pathogens and present the pathogen antigens to naive T cells. TCRs on the T cell surface recognize the antigen bound to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules on the surface of APCs [31]. T cells that possess a TCR specific for the antigen-MHC complex are activated to proliferate (a process known as clonal expansion) and differentiate into effector T cells through induction of many pathways downstream of the TCR and CD28, a co-stimulatory molecule essential for optimal T cell activation. By this process, relevant T cells give rise to many clones with the ability to secrete pro-inflammatory, antiviral cytokines and cytotoxic enzymes to eliminate the pathogens during the first 1–2 weeks of infection [32, 33]. Proliferation of helper CD4 T cells instruct other immune cells such as B cells to clonally expand and differentiate into antibody-producing plasma cells. The antibodies neutralize, or block the pathogen’s ability to access human cells by coating the pathogen and thereby targeting it for phagocytosis by APCs (a process known as opsonization), or by activating the complement system, which promotes pathogen destruction. Pathogens that are not eliminated by the above mechanisms go on to infect cells and then become targeted by CTL. After the peak of immune cell expansion and clearance of the pathogen, 90–95% of antigen specific-T cells undergo cell-mediated apoptosis in a process termed ‘contraction.’ The remaining 5–10% of T cells differentiates into a pool of long-lived memory CD8 T cells that persist at low frequencies but retain cytotoxic effector functions and high proliferative potential, allowing them be on constant surveillance and prevent re-infection of the host by the same virus [33, 34].

Because of the enormous antigenic receptor repertoire, only a very small number of cells recognize and respond to any single antigen. Therefore, the ability to clonally expand in order to generate a sufficient and effective immune response is a paramount aspect of adaptive immunity and the clearance of infection. However, normal somatic cells cannot infinitely divide because of a cell-intrinsic phenomenon known as the Hayflick limit, which is thought to have evolved to protect against the development of cancers [35]. This strict limitation of proliferative potential, referred to as replicative senescence, although possibly beneficial as a tumor suppressor mechanism, has the potential to negatively impact the function of the immune system, as will be discussed in detail below.

CD8 T cell replicative senescence: in vitro studies

In 1961, Drs. Hayflick and Moorhead first described the phenomenon of replicative senescence in cultures established from human lung fibroblasts. Thereafter, many researchers went on to investigate this process in other somatic cell types, including epithelial cells, hepatocytes, endothelial cells and keratinocytes. In vitro senescence is defined by a limited proliferative capacity of somatic cells, resulting in arrested cell cycling and a population of non-dividing, but fully viable senescent cells [36]. However, only recently has this process been examined in the context of the immune system. At first glance, it may seem counterintuitive that there is a limited proliferative capacity of immune cells, since the ability to undergo rapid, extensive, and often repeated rounds of clonal expansion is absolutely essential to their protective functions. However, the observed decline of T cell immune function in elderly persons suggests that T cells may undergo replicative senescence as human beings age chronologically. Indeed, in vitro studies on senescence in T cells have delineated well-characterized and invariable changes in cell surface markers, signal transduction pathways, and functional traits that are similar to T cells from elderly people, as well as to T cells from younger persons chronically infected with HIV. Importantly the presence of various types of senescent cells, including those found in the immune system, have been shown to have some negative health effects, due, at least in part, to their production of pro-inflammatory molecules and cytotoxic enzymes [24, 37].

Following multiple rounds of stimulation with allogeneic or peptide-pulsed autologous antigen-presenting cells (APCs), or with antibody-coated microbeads that mimic APCs, CD8 T cells are driven to senescence in a fairly predictable manner in vitro. Cultured senescent T cells share similar functional changes with other senescent somatic cells including the expression of cell cycle inhibitors, inability to undergo apoptosis (a type of programmed cell death), shortened telomeres, and a pro-inflammatory secretion pattern [38–41]. This arrest is caused by the erosion of telomeres, the repeating hexameric sequences of nucleotides at the ends of linear chromosomes, as cells undergo replication. If telomerase, a holoenzyme that elongates telomeres, declines in activity, the chromosome is recognized as a double strand break and can no longer proliferate [42]. However, senescent T cells still retain some normal effector function, as described in earlier reviews [43, 44]. For instance, senescent CD8 T cells are capable of upregulation of CD25, the alpha chain of the IL-2 receptor, when exposed to antigen [45] and maintain MHC-unrestricted cytotoxicity [46]. With adequate activation and constant exposure to IL-2, which is necessary for survival in cell culture, normal human T cells can undergo between 25 and 40 population doublings, depending on the cell donor, before reaching senescence [47], with an average culture lifespan of approximately 33 population doublings [48].

A critical phenotypic and genetic change as T cells become late-differentiated and progress to senescence is the loss of gene and surface expression of CD28, an essential co-stimulatory receptor that activates T cell pathways such as the Akt and NFκB pathway [49, 50], and modulates important functions such as lipid raft formation, IL-2 gene transcription, apoptosis, stabilization of cytokine mRNA, glucose metabolism and cell adhesion [51]. Therefore, downregulation of CD28 would fundamentally alter normal T cell function, survival, and proliferation. Indeed, senescent T cell cultures were observed to be >95% CD28-negative within the CD8 T cell subset, as compared to over 90% positive in the starting population from healthy, young donors [52]. Although CD28 expression is dynamic and is regulated, in part, by protein turnover and transient transcriptional repression, the loss of CD28 on the cell’s surface and transcription is eventually permanent when senescence is reached. This loss of CD28 parallels the low percentage of CD28+ CD8 T cells found in aged individuals and those afflicted with HIV infections [53, 54].

Because CD28 is necessary to mount effective T cell immune responses, we hypothesized that sustained transcription of CD28 in long-term cultures of CD8 T cells in the previously described in vitro model may prevent the phenotypic and proliferative changes characteristic of replicative senescence. Successfully transduced cells did, in fact, exhibit higher initial mRNA levels and surface expression of CD28, as well as prolonged telomerase activity and significantly increased proliferative potential. Moreover, the senescence-associated proinflammatory cytokine production profile was also prevented. However, proliferation was not indefinite, and the cells eventually stopped dividing and lost CD28 surface, but not gene, expression. At that point, CTLA-4, an inhibitory receptor on T cells that can compete with the CD28 ligands on APC, was upregulated. Fundamental qualities of replicative senescence, including cell cycle arrest, were eventually observed in these cultures, suggesting that sustained transcription of CD28, while significantly delaying senescence, ultimately failed to permanently prevent this process [55].

Another significant feature of senescent CD8 T cells in cell culture is the resistance to apoptosis, consistent with the original findings in fibroblasts [56]. Senescent and late passage T cells exhibited reduced ability to undergo apoptosis as compared to quiescent early passage cultures from the same donor when exposed to six different apoptotic stimuli [39]. Furthermore, culture-driven senescent CD8 T cells expressed less Hsp70, a heat shock protein that promotes survival of cells under stress [57], consistent with previous observations in various cell types such as fibroblasts [58]. This feature parallels in vivo findings, which also documented an apparent decrease in Hsp70 with increasing age [59].

Although replicative senescence is manifested by decline in immune function, in vitro senescent CD8 T cells actually retain some, albeit dysregulated, effector functions in response to antigenic stimulation. As CD8 T cells are driven to senescence in cell culture, they produce more proinflammatory cytokines, mainly IL-6 and TNFα, than their more “youthful” early-passage counterparts [24]. Interestingly, these same inflammatory cytokines are strongly associated with frailty in the elderly [60]. Treatment of T cells with exogenous TNFα in long-term cultures has been shown to accelerate acquisition of senescent characteristics, including downregulation of CD28 gene expression, telomerase activity and IL-2 message [61]. Thus, it is possible that senescent T cells present in vivo may negatively affect other non-senescent T cells by secreting an inflammatory cytokine that promotes loss of CD28 and accelerated senescence. Unlike IL-6 and TNFα, the anti-viral cytokine IFNγ decreases with culture age and antigenic stimulation, diminishing the ability of senescent CD8 T cells to kill virally infected cells [38, 62, 63]. Together, the data suggest that senescent T cells not only fail in their effector function against viral infection, but may also impact the anti-viral function of other T cells, by promoting their premature senescence.

It is important to note, however, that although chronological aging and infections such as HIV, which constitute accelerated aging, are correlated with the accumulation of T cells with senescence markers, there is no clear correlation between in vitro lifespan of T cell cultures and chronological age of the donor [45]. Nevertheless, the accumulated data from multiple lines of research reveals that senescent T cells in long-term cell culture studies do mimic many facets of T cell dysfunction observed in elderly persons, cancer patients, and individuals harboring chronic/persistent viral infections.

The role of telomeres and telomerase in aging

Telomeres are tandem sequences of (TTAGGG)n nucleotide repeats that serve as protective ends of chromosome. Functional telomeres are essential for continued cell proliferation. Because of the incomplete replication of the lagging strand during DNA synthesis, termed the “end replication problem” [64], telomeres can lose up to 200 base pairs in somatic cells with each cell division [65–68]. Progressive telomere erosion eventually leads to the chromosome reaching a critical point at which the exposed DNA end is recognized as a double strand break and cannot pass cell cycle check points [42]. This mechanism—by inducing either senescence or apoptosis-- prevents potentially genetically unstable cells from proliferating indefinitely and developing into cancer. Telomere sequences can be restored by a ribonucleoprotein called telomerase by adding TTAGGG repeats onto the telomeres using its intrinsic RNA, TERC, as a template for reverse transcription [69]. Telomere attrition is not likely to be a linear process, since studies of T cells isolated ex vivo have demonstrated that only after the age of 40 do human cells enter a phase of accelerated telomeric shortening [70].

Telomerase is repressed in most human somatic cells after birth. However, lymphocytes possess the ability to upregulate telomerase upon activation, which allows the extensive proliferation required to combat infection, while maintaining telomere lengths [71]. Similar to this in vivo demonstration of telomerase activation during acute viral infection, ex vivo human CD8 T cells activated with antibodies against CD3 and CD28 have high initial telomerase activity and are able to maintain their initial 10–11kb telomere length through multiple rounds of cell division. Nevertheless, with repeated rounds of stimulation, their telomere lengths progressively shorten to approximately about 5–7kb [40, 48] and their telomerase activity becomes undetectable [72]. Interestingly, in contrast to the CD8 subset, human CD4 T cells do not undergo the same dramatic decline in telomerase activity in vitro [72]. Shortened telomeres and reduced telomerase activity are hallmark features of T cell senescence in vitro and has been associated with many pathological ailments in vivo, which will be discussed in detail later on in this review.

This loss of telomerase activity in vitro parallels loss of CD28 surface expression [72, 73]. Blocking the binding of CD28 to its receptors, B7-1 and B7-2 ligand, on APCs during stimulation significantly reduces telomerase activity, suggesting a role of CD28 in telomerase regulation. Consistent with this observation, sorted CD28+ T cells were found to have significantly greater telomerase activity than the unseparated T cell population after activation in vitro [72]. The outcome of telomerase activity differences based on CD28 expression is that CD28− T cells have shorter telomeres than their respective CD28+ counterparts from the same donor, findings reported by several groups [53, 74, 75]. A recent study that utilized retroviral vectors to constitutively express CD28 in long-term cultures demonstrated enhanced and prolonged telomerase activity as compared to the vector-control transduced T cells [76]. Together, these reports strongly implicate CD28 signaling in the modulation of telomerase and thus maintenance of telomere length.

The central role of telomerase in linking senescence at the cellular level with physiological aging is strikingly illustrated by the multiple abnormalities in persons with the autosomal dominant form of dyskeratosis congenital, a disease caused by mutation in the gene encoding the RNA component of telomerase, TERC [77]. The defects in these patients are most dramatic in tissues in which cells divide rapidly and often, such as hair follicles, skin, lungs, gut and bone marrow. In addition, these patients exhibit numerous age-related pathologies including higher rates of malignancies. Another clinical example is the premature aging syndrome known as childhood progeria, in which individuals have mutated or shortened telomeres. Children with progeria appear old and die of age-related diseases such as heart disease. Genetically engineered mice, which lack telomerase, have been used to analyze progeria in humans. These animals age far more rapidly than normal mice, suffering from multiple age-related conditions, such as osteoporosis, diabetes and neurodegeneration. However, when the inactivated telomerase was switched back on by feeding the mice a chemical called 4-OHT, there was a dramatic reversal of the age-related phenotype: the animals regained their fertility, and other organs such as the brain, spleen, liver and intestines showed correction of their degenerated state [78].

Studies performed on in vitro cultured cells clearly demonstrate that ectopic expression catalytic subunit of telomerase (hTERT) is sufficient to prevent the senescence-induced end-stage and allow proliferation. In addition to fibroblasts and endothelial cells, T cells have also been shown to be amenable to telomerase manipulation [79, 80]. Stable hTERT expression in long-term cultures of HIV-specific CD8 T cells resulted in enhanced proliferative potential and maintenance of telomere length compared to control transduced cultures. Importantly, the telomerized HIV-specific T cells also demonstrated greater inhibition of HIV replication and delayed loss of IFNγ production in the presence of HIV peptides, suggesting that telomerase is absolute essential not only for proliferation, but also for effective immune function [38].

Taken together, these studies suggest that inducing telomerase activity might have positive consequences in T cells that are reactive to viruses such as HIV. As proof of this principle, CD8 T cells from HIV-infected persons were exposed in cell culture to a plant-derived small molecule telomerase activator (“TAT2”). These cells showed upregulation of telomerase activity, retardation of telomere shortening, greater proliferative potential, as well as increase in functional cytokine and chemokine production [81]. When a specific telomerase inhibitor was included along with TAT2 in the culture, all these effects were totally abrogated. These in vitro studies underscore the potential beneficial therapeutic applications of maintaining telomerase activity as an approach to retarding the loss of immune control over infection.

Aging and replicative senescence in vivo

Current animal models of aging are somewhat limited in terms of elucidating certain mechanisms underlying human aging. For instance, mitogen-stimulated murine T cells do become senescent in terms of reduced proliferative potential [82], but cell cycle arrest occurs only after 10–15 doublings, long before significant telomere erosion occurs [83, 84]. Furthermore, humans encounter a plethora of pathogens throughout their lifetime, a process that continually molds the T cell specificity repertoire and affects the quality of their immune system, particularly during old age. It is obvious that this situation cannot be mimicked in short-lived laboratory animals that are protected from the hugely diverse spectrum of bacteria, viruses and parasites to which humans are exposed over many decades.

The reduced adaptive immune function observed with biological aging is, in large part, caused by thymic involution, the shrinking of the thymus, and a decline in naïve T and B cell output from the bone marrow. This leads to a shift in the lymphocyte population composition towards the accumulation of memory T cells. Furthermore, within the total memory cell population, there are changes in the proportional representation of these antigen-experienced cells. Specifically, memory T cells from older persons are often late differentiated or senescent, and are clonally restricted. This phenotype likely results, in part, from the lifetime exposure to prevalent chronic viral infections such as cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). These herpes viruses infect the majority of the population early in life, suggesting that they may be the primary drivers of replicative senescence in vivo. Although CMV and EBV are not life threatening, and often remain in a latent state, they persist over many decades and are never eliminated by the immune system. In fact, adaptive immune cells may be working over-time to suppress these viruses and prevent their reemergence. In this way, the constant interaction with herpes virus viral peptides and suppression of viral replication leads to chronic, low levels of T cell activation, proliferation and ultimately senescence and the resultant inflammatory milieu.

Within the total memory pool, arguably, the most dramatic functional changes occur in the CD8+ T cell subset. Similar to what is observed in long term in vitro cultures, there is a progressive loss of CD28 expression, an overall telomere shortening, and a decline in IL-2 production by T cells isolated from the elderly. Studies have shown that older persons have higher proportions of CD28-negative, late-differentiated cells within the CD8 T cell subset (>60%) compared to <10% in younger adults [52]. Importantly, telomere studies have confirmed that the CD28-negative cells had undergone extensive cell division compared to CD28+ T cells from the same individual. Furthermore, within the elderly population, individuals infected with herpes viruses have higher percentage of CD8+CD28− T cells than uninfected persons [85].

In addition to aging itself, autoimmune diseases, chronic infections, and cancer are also thought to drive immune cells towards late-differentiation and replicative senescence. For example, persons with rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune disease that leads to excess inflammation of the synovium, have elevated levels of CD28-negative T cells in affected joints, and these cells secrete higher levels of TNFα, one of the cytokines associated with senescence. Interestingly, TNFα has been shown to suppress CD28 gene transcription, suggesting that secretion of this cytokine by senescent cells may function to drive other T cells in the joint to replicative senescence [86]. As noted previously, another chronic infection associated with senescence is HIV, where there is accumulation of CD28-negative cells within the CD8 T cell subset as compared to unaffected age-matched controls [87]. Moreover, telomere length of CD8+CD28− T cells from a group of ~40-year-old HIV+ persons are in the same range as those of lymphocytes isolated from uninfected centenarians [74]. Thus, HIV/AIDS has been proposed as a model of accelerated or premature immunosenescence [88]. Finally, there is accumulating evidence that replicative senescence may play a role in tumor biology as well as cancer immunotherapy, as will be discussed later on.

In addition to the loss of CD28 expression, in vitro replicative senescence is associated with the upregulation of a number of proteins including the cyclin dependent kinase (Cdk) inhibitors p21CIP1/WAF1 (p21) and p16INK4a (p16) [89–92]. More specifically, p21 has been reported to be mostly involved in telomere damage induced replicative senescence, while p16 is mostly involved in stress induced (premature) senescence [93, 94]. Oxidative stress can also enhance telomere dysfunction and promote acquisition of a senescent phenotype [95]. However, there are still some questions regarding how to most accurately define senescent T cells in vivo via their cell markers. The loss of CD28 is commonly used as a biomarker for late-differentiation, as well as senescence, but this observation is an incomplete definition. Researchers also cite the absence of another stimulatory surface molecule, CD27, coupled with upregulation of inhibitory molecules, CD57, a surface marker found on terminally differentiated T cells as a more definitive description of truly senescent T cells. CD28−CD57+ T cells are commonly found in individuals with chronic immune activation, and they increase in frequency with age [96]. In HIV/AIDS, as well as in persons with other chronic infections [97], a large proportion of virus-specific CD8 T cells with CD57 expression that can produce cytokines such as TNFα in response to cognate antigen are unable to proliferate during in vitro culture. Furthermore, CD57 expression on T cells has been associated with shorter telomeres and these cells have undergone more cell divisions compared with other memory cells of other phenotypes [98]. Additionally, the surface receptor killer cell lectin-like receptor G1 (KLRG1) has been shown to be prominently upregulated on T cells in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV)-infected mice, having inhibitory properties by blocking co-stimulatory activities mediated by the AKT pathway such as proliferation [99, 100]. The increased expression of both CD57 and KLRG1 on CD8 T cells and NK cells has been associated with clonal exhaustion and autoimmunity [101]. Finally, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4), which can compete with CD28 for costimulatory ligands [102], has been shown to increase during HIV infection, decrease with the onset of HAART therapy [103] and may serve as a marker for chronically stimulated T cells in vivo. CTLA-4 expression also increases progressively as T cells are driven by repeated stimulation to the end stage of senescence in vitro [76].

Senescent CD8 T cells may acquire new functional properties, such as suppression of other types of immune cells [24]. This will be discussed in the context of cancer later in this review. Interestingly, the only context in which senescent CD8 T cells are associated with a positive effect on health is in organ transplant patients, where their abundance seems to correlate with reduced rejection episodes, suggesting that they may function to suppress immune reactivity to the donor organ. However, in bone marrow transplants, marrow donated by older individuals has been shown to have diminished capacity to reconstitute the immune system of the recipient [8].

Whereas the cell culture model has been highly informative in documenting and characterizing the process of T cell replicative senescence, this model cannot predict all the changes that may occur during in vivo aging. For example, investigative efforts have shown expression of both CD28 and CD57 on some CD8 T cells [104, 105], and the observation of enhanced antigen-induced apoptosis of CD57+ CD8 T cells, in contradiction with in vitro data [98]. Furthermore, it has been reported that T cells with varying levels of expression of CD57, KLRG1 and/or loss of expression of CD28 still have some proliferative potential, depending on the presence of specific cytokine combinations [106–109]. There are also reports of persistent proliferation of some CD8+CD28− cells from older individuals [107]. In addition, a comprehensive analysis did not show reduced proliferation capacity of cells explanted from elderly humans [110], but this study does not eliminate the possibility that during aging, non-dividing, putatively senescent cells accumulate and pack the immunological space. As previously mentioned, many analyses in elderly persons have shown that CMV seropositivity is strongly correlated with the expression of these putative senescent biomarkers, thereby raising the possibility that senescence is simply the negative by-product of the successful long term defense against these latent herpes viruses that infect 85–100% of the population [111–116].

It is generally recognized that senescent-like T cells are present in vivo, and likely contribute to immunosenescence in general, and to the specific associated pathologies observed in aging, as we have discussed so far. A major difficulty in studying cellular aging in vivo is the lack of accurate models, since even the changes observed in mice and other rodents do not precisely mirror those observed in humans. Even in human studies, the divergence between some of the in vitro and in vivo findings needs to be further investigated in order to more fully characterize the molecular changes that define replicative senescence, and how the process affects immune function and health of the elderly population.

Exhaustion versus senescence

The current body of research on T cell dysfunction often categorizes senescence and exhaustion as the same phenomenon because they share similar characteristics, such as the loss of proliferative potential and CD28 surface expression, and changes in cytokine secretion. Research in mice and ex vivo humans cells have shown that both senescence and exhaustion of CD8 T cells result from chronic antigenic stimulation by viruses and are thought to have evolved as a way of preventing excessive and damaging T cell responses to infection [117], but the precise molecular changes that lead to each end-state are still unclear. What is currently understood as a major distinghishing difference is that severe exhaustion results in eventual apoptosis of the exhausted cell, while senescent cells persist ( due their apoptosis resistance). In contrast to senescence, CD8 T cells become exhausted in environments of high antigenic load and lose their function in a specific chronological manner, beginning with the loss of IL-2 production and decline in proliferative potential, and followed by a reduction in TNF production. Finally, IFNγ production and cytotoxic activity are abolished and the cell is marked for degradation [118, 119]. Low levels of CD4 T cell also correlate with greater levels of exhaustion. Compared to naïve or effector CD8 T cells, exhausted murine T cells have altered gene expression profiles in important cellular processes such as chemotaxis, adhesion, co-receptors, migration, metabolism and energy [120].

To date, the most prominent identifying feature of T cell exhaustion is the increased surface expression of the CD28 family member, programmed cell death 1 (PD-1). Senescent T cells, defined primarily by high CD57 and loss of CD28 and CD27 molecules, do not necessarily have PD-1 expression, though they may be present concomitantly, as seen in some HIV-1 infected persons [117, 121, 122]. PD-1 surface expression was first observed in mice infected with lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV), where its expression was elevated on CTL that had lost effector functions, but not on functional LCMV-specific CD8 T cells [123]. In humans, virus-specific CD8 T cells during chronic infection with such viruses as human T lymphotrophic virus (HTLV) and hepatitis B, have high PD-1 expression and altered cytokine expression patterns that impact their ability to clear infection. Other important features characterizing exhausted CD8 T cells include the expression of inhibitory receptor CTLA-4, Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3), T cell immunoglobulin mucin-3 (TIM-3) and B lymphocyte-induced maturation protein (Blimp-1) [120]. Significantly, blockade of the PD-1 signaling pathway with antibodies can restore antigen-specific T cell cytokine secretion and proliferation in LCMV-infected mice [124] and in humans with chronic HIV [121, 125, 126]. The mechanisms driving CD8 T cell exhaustion are not completely understood, but almost certainly include intrinsic regulatory pathways (such as signals mediated by the inhibitory receptor PD-1) and extrinsic regulatory pathways (including immunoregulatory cytokines and regulatory T cells) [127].

Downregulation of telomerase activity and shortened telomeres, defining features of senescence, have not been studied extensively in exhausted cells. However, a recent study by Lichterfeld et al. analyzed telomere length and telomerase activity in HIV-1-specific CD8 T cells and found the blocking the PD-1/PD ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway increased both telomere length and telomerase activity in antigenic peptide-stimulated cells from HIV progressors [128], suggesting that PD-1 may play a role in the decline in telomerase seen in senescent and exhausted T cells. Still, the role of telomerase in the development of exhaustion is largely unknown, and more research will necessary to parse out the exact mechanisms that drive human T cells to reach senescence versus exhaustion. A more critical and thorough review by Akbar and Henson (2011) discusses this topic in greater detail [118].

Inflammation, the immune system and age-related pathologies

Infectious diseases have been a pervasive threat to survival throughout evolution. This suggests that stronger immune responses and inflammation during early life have been central in the survival of the species in the treacherous environments throughout human history. Accordingly, it is likely that certain genes and gene variants associated with robust inflammatory immune responses have been evolutionarily selected for, since they allowed survival to reproductive age. [26, 129]. Furthermore, until recently, most humans did not live to very old age so that there was no evolutionary pressure to prevent or reduce pathologies that arise with age. Thus, there are many age-related diseases and disorders, and in many cases, the immune system may be responsible for the cause, or at least the exacerbation of these conditions. This suggests that judicious manipulation of the immune system may provide novel immune-based therapeutic approaches to treat, prevent or limit the severity and progression of various pathologies.

The primary mode of defense and protection against pathogens by immune cells is through the secretion of inflammatory mediators such as cytokines and chemokines. However, chronic levels of elevated inflammation have negative effects on tissues, organs and overall health. Several studies report that increased levels of circulating proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TNFα and their receptors, serve as significant independent risk factors for mortality and morbidity in the elderly [130]. High levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the elderly were also correlated with 2–4 fold increase in production of several acute-phase chemokines such as vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), and C-reactive protein (CRP), both soluble molecules that are associated with several age-related pathologies including atherosclerosis and insulin resistance [88, 131–134].

Studies in mice have helped elucidate the relationship between chronic inflammation, disease and lifespan. For example, mice fed a restricted low-calorie diet, which had been previously shown to extend maximum life span, have lower levels of TNFα and IL-6 production by T cells, suggesting that lower cytokine levels may function in increased survival rates [135]. This state of chronically elevated inflammation associated with biological age, termed “inflamm-aging,” [136, 137] underscores the prominent role of inflammation in the age-associated dysfunctional immune changes. It has been proposed that inflamm-aging may represent the common denominator underlying a wide range of age-related diseases.

Inflammation was one of the parameters documented in one of the most thorough longitudinal studies in humans, the Swedish OCTO/NONA studies, which followed free-living persons >85 years of age. The purpose of the study was to determine the biomarkers that predicted morbidity and mortality in this already old, genetically homogeneous population. Interestingly, one striking finding was that low-grade inflammation might predict mortality late in life, often through damage to non-immune organs [11]. The study also identified a so-called “immune risk phenotype” (IRP) representing the cluster of immune parameters associating with 2-, 4- and 6-year survival of the very elderly [138, 139]. A characterization of IRP is as follows: low levels of B cells, increased levels of CD8+CD28−CD57+ T cells, poor T cell proliferative response, CD4/CD8 ratio of <1, and CMV seropositivity [140, 141]. A large population of clonally expanded CMV-specific CD8 cells has been described in elderly individuals and analysis of these cells indicate that they are dysfunctional, more resistant to apoptosis, take up immunologic space, and may be harmful to the immune system [141]. Current findings support the hypothesis that a large proportion of senescent CD8 T cells are driven predominantly by CMV (along with EBV) since between 50–85% of people will be infected with CMV by age 40 and all individuals in the IRP group were CMV-seropositive, compared to around 85% in the non-IRP group.

Additional follow-up studies to the original IRP work have further underscored the negative effect of chronic inflammation in the elderly, with a focus on TNFα and IL-6 as predictors of immune status [142]. Specifically, circulating TNFα levels were found to be a direct predictor of mortality in elderly populations, while IL-6 was the most significant risk biomarker. Another study, which followed 129 elderly nursing home residents documented that a detectable TNFα serum level was associated with death within 13 months [143]. The IRP and studies associating specific cytokine profiles with morbidity and mortality represent prognostic advances that may be further expanded in the clinical setting

Specific age-related pathologies with immune components

Osteoimmunology

The emerging body of work suggesting a role of the immune system in bone-related pathologies had been originally based on the observations relating bone loss in the form of osteoporosis with systemic and local inflammation [144–147]. Reports also showed that increased inflammation was associated with a higher incidence of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Furthermore, there is an increased risk of developing osteoporosis in various inflammatory conditions and diseases associated with chronic immune activation, including HIV infection [148–151]. An association between circulating levels of CRP, a strong marker of oxidative stress and inflammation, and bone mineral density has been documented in several immune and inflammatory diseases, as well as in healthy individuals, suggesting a relationship between systemic, low-grade inflammation and osteoporosis [152]. Furthermore, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), characterized by cartilage and bone destruction in the joints, is often cited as a link between inflammation and bone loss, resulting from the release of proteinases (metalloproteinases) and proinflammatory cytokines including TNFα [153]. The immune phenotype of osteoporotic patients also underscores a substantial correlation between T cell senescence and bone remodeling. Analysis of peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets indicates that osteoporotic patients have an increased CD4:CD8 ratio, similar to the IRP findings, and greater numbers of CD45RO effector memory T cells, whereas the naïve subset is markedly decreased [154].

The previously described correlational studies have led to development of an emerging interdisciplinary field known as osteoimmunology, which focuses on the intimate interactions between the skeletal and immune cells primarily within the bone marrow [155]. Immune cells, especially T cells, can influence the balance of bone mineralization, carried out by osteoblasts, and resorption, accomplished by osteoclasts [156]. Cytokines and other protein molecules that regulate osteoclastogenesis, such as receptor activator of NFkB ligand (RANKL), are also key mediators in several immunological responses that are observed to increase with age and/or are associated T cell replicative senescence. For example, in vivo studies in mice and in vitro experiments on human T cells have shown that activated T cells produce cytokines, such as IL-6 or RANKL, that leads to activation and maturation of osteoclasts upon binding on the RANK receptor [157, 158]. Numerous studies have shown that many age-related proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNFα and IL-1 may play direct roles in the pathogenesis of osteoporosis as well [142, 159]. IL-6 can also directly enhance osteoclast activity by RANKL-independent mechanisms by extending the lifespan of the osteoclasts by inhibiting their apoptosis. TNFα has been shown to both promote osteoclast generation and to stimulate mature osteoclasts to undergo a greater number of resorption cycles through modulation of RANKL activity. Furthermore, TNFα can induce downregulation of collagen synthesis in osteoblasts and enhanced degradation of the extracellular matrix [160]. In inflammatory states and autoimmune diseases, activated T cells produce RANKL and pro-inflammatory cytokines, all of which can induce RANK expression in osteoblasts [161]. In this way, the constant activity of senescent or chronically activated T cells can cause extensive bone loss, as seen in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis. Thus, immunosenescence may render older adults susceptible to bone diseases. Indeed, a recent study found that elderly patients with osteoporotic fractures had significantly more CD8 T cells with a senescent phenotype, including CD57 surface expression, in their peripheral blood [162].

Reduced bone mass within the oral cavity is also observed in the elderly, and has been linked to other age-related pathologies including atherosclerosis. Both activated and matured CD4 and CD8 T cells are found in the periodontal lesions [163, 164]. In addition, CD8 T cells lacking CD28 expression were found in gingival tissue [165], suggesting that replicative senescence may play a role in oral bone loss. There have been reports of increased production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) in people with periodontal diseases as well [166]. Our own recent studies have shown that PGE2, which is an important and ubiquitous mediator of inflammation, causes cultured CD8 T cells to progress more quickly to senescence, with a more rapid loss of CD28 protein and gene expression, reduced proliferative potential and suppressed telomerase activity (manuscript in preparation). Moreover, exposure of human T cells to PGE2 in concert with activation increases their RANKL production; if a similar process occurs in vivo, this would function to enhance osteoclast activity and bone breakdown. In support of this hypothesis, in patients with periodontitis, high levels of PGE2 were related to the severity of periodontal disease and the increase in alveolar bone loss [167, 168]. In addition, there is a greater production of PGE2 by old periodontal ligament cells [169], and this might promote recruited inflammatory T cells to acquire a senescent phenotype, enhancing the rate of alveolar bone resorption in elderly patients.

As a means to reduce address this clinical problem, our group has demonstrated a role of vitamin D in ameliorating the T-cell mediated destruction of bone. Vitamin D had long been known as a key modulator of bone integrity by promoting calcium absorption in the gut and maintaining adequate serum calcium and phosphate concentrations [170], but only when the vitamin D receptor (VDR) was detected on T cells did research on its role in immune/skeletal interactions become active. Initial studies suggested an immunosuppressive role of this metabolite, since it decreased the secretion of Th cell-associated cytokines and increased the population of T regulatory cells [171, 172]. We found that when we treated CD8 T cells from both HIV-negative and HIV-positive persons with low concentrations of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1–10nM), T cells transcribed less RANKL, TACE, which is the enzyme that cleaves RANKL from the surface of the cell into its soluble form, and conferred a less senescent T cell phenotype over time, including greater CD28 and CD27 surface expression that their untreated counterparts. Thus, vitamin D, in addition to its beneficial functions on innate immunity, specifically through the induction of cathelicidin production by macrophages [173], may play a critical role in modulating CD8 T cell function and may, modulate certain facets of the replicative senescence program.

T cell replicative senescence and cancer

Aging is the single highest risk factor for developing cancer. CD8 T cells, the immune system component that is central to the process of cancer immune surveillance, can recognize and kill cells that express tumor-specific antigens in the context of MHC. However, the combined effect of the accumulation of senescent T cells, which occupy “immunological space” and age-related thymic involution, which limits the naïve T cell repertoire, results in diminished immune surveillance capacity by old age. These changes synergize with a decline in innate immune function, all of which may contribute to the increased cancer incidence in the elderly population,

A second aspect of T cell-tumor biology relates to the possible role of chronic exposure to tumor-associated antigens, which may be also driving certain T cells to senescence. Although there is no direct causal data, there have been many correlational studies that support this hypothesis. For example, tumors associated with latent viral infections are increased with age, and are also associated with reduced immune function, as in immunosuppressed organ transplant patients and persons with HIV/AIDS. In AIDS patients, Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS, a rare vascular neoplasm) is uniformly associated with the latent herpes virus HHV8. Interestingly, co-culture of CD8+CD28− T cells from HIV-infected persons to normal vascular endothelial cells causes the latter to develop morphologic features of KS. Additionally, the rate of cervical cancer, which is associated with high-risk strains of human papillomavirus, increases during immune suppression [174].

Non-viral associated tumor antigens may also have the potential to drive antigen-specific T cells to become senescent. A striking example is the strong reactivity and immune response of CD8 T cells from prostate cancer patients to prostate-specific antigen (PSA), which is elevated in these individuals [175, 176]. Patients with certain cancers often times have increased proportions of senescent T cells, and this has been associated with poor clinical outcomes. For example, CD8+CD28− T cells can be purified from various types of human tumors, including lung [177], colorectal [178], ovarian [179], lymphoma [180] and breast gruber [181, 182], as well as from metastatic satellite lymph nodes and peripheral blood of cancer patients [177, 183]. Expanded clonal populations of cytotoxic T cells with other features of replicative senescence (e.g., CD57 expression) are also present in patients with melanoma and multiple myeloma [184, 185], and the abundance of senescent CD8 T cells correlates with tumor mass in head and neck cancer [186]. Moreover, in renal cancer, the proportion of CD8 T cells with features of replicative senescence is actually predictive of patient survival [187].

Interestingly, human T cells from healthy donors incubated with tumor cells for as little as 6 h at a low tumor: T cell ratio acquire a senescence-like phenotype, including the loss of surface expression of costimulatory receptors CD27 and CD28, telomere shortening, and induction of the cell cycle arrest proteins, p53, p21 and p16. Initiation of senescence is likely caused by the secretion of soluble factors by the cancer cells. Moreover, these T cells may play an active role, based on the observation that they can suppress proliferation of responder T cells after being in physical contact with them [188]. Highlighting the role of telomere length in carcinogenesis, a recent meta-analysis of 27 studies found a significant inverse correlation between telomere length of blood cells and cancer incidence [189]. However, these studies do not necessarily prove that these naturally occurring senescent T cells stimulate the progression of tumors in vivo in humans. In order to define the role of senescent T cells on the progression of age-related cancers in humans, it would be necessary to eliminate senescent cells and/or their soluble mediators from cancer-prone tissues and determine the consequences on tumor pathology. Conversely, the chronic activation by tumor antigens, like antigens of latent viruses, may indeed contribute to driving T cells to senescence and resulting in their failure to detect other tumor cells.

Another important issue regarding senescent T cells and cancer emerges from a recent study, in which adoptive immunotherapy with autologous anti-tumor tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) following chemotherapy led to tumor regression in half of the patients with metastatic melanoma. Significantly, tumor regression was strongly correlated with proliferative potential and telomerase activity of the transferred T cells [190]. Complementing this finding is study in which the investigators observed that patients with objective clinical responses had TILs with a mean telomere length of 6.3 kb, whereas telomeres of TILs that were not associated with significant clinical responses were markedly shorter. Expression of the costimulatory molecule CD28 also corresponded to longer telomeres and T cell persistence [191]. These studies suggest that in the transferred cells, telomere length and proliferative potential, both prominent features that are reduced in senescent T cells, may play a considerable role in mediating response to adoptive immunotherapy in the treatment of cancer. The results underscore the importance of senescent T cells in the clinical setting, since they can be used in predicting effectiveness of adoptive immunotherapy and the status of the cancer.

In practice, most primary tumors can be removed surgically, followed by radiation, chemotherapy or adjuvant therapy. However, these therapies are largely ineffective against metastases. Recent advances have shown some promising results of cancer vaccines against metastases. However, it seems likely that immunosenescence would significantly impact the efficacy of prophylactic vaccination, based on a large body of evidence that the elderly respond significantly less to vaccination than the young [192, 193]. Several vaccine studies in preclinical cancer models at old age demonstrated that in most cases T cell responses were hardly detectable [194]. Impaired immune responses in elderly can, in part, be attributed to the decline in CD28. Loss of this important costimulatory molecule would cause decreased T cell responses in aged humans.

The previous illustrations are likely reasons that immunological and chronological age is associated with decreased responsiveness to cancer vaccination. Therefore, in order to develop potential effective therapies against cancer and improve immune function, it is important first that we distinguish changes caused by persistent infection from those caused by cancer itself.

As an important catalyst of carcinogenesis, the hormone-like substance, PGE2, is overproduced in many tumors. It accelerates cancer progression by promoting angiogenesis and metastasis, and by influencing the immune response [195, 196]. Studies have also found that the enzyme that produces PGE2, cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, increases its activity in macrophages from old mice [197]. Our own recent studies addressed the potential effect of PGE2 on human T cells, since lymphocyte functional decline is a significant defect observed in persons with cancer. Our preliminary findings indicate that in the presence of physiologically relevant concentrations of PGE2, T cells exhibit reduced proliferation and telomerase activity, lower production levels of antiviral cytokines including IFNγ, and reduced CD28 protein and message. The effects of PGE2 would engender a more senescent-like phenotype to T cells and reducing their ability to detect and eliminate tumor cells.

Role of the immune system in age-related neurological diseases

Brain-infiltrating lymphocytes can directly modulate brain homeostasis under both physiological conditions and in the inflammatory state caused by disease or injury, during which proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNFα are found to be elevated [198, 199]. Because senescent CD8 T cells are increased with age and produce significantly higher concentrations of inflammatory mediators, there is a possibility that they are among the cells recruited to the brain during disease or injury, and may contribute to the inflammation. This increase in inflammation seen in neuropathologies correlates with deterioration of cognitive function, including the reduced speed of information processing, reduced working memory capacity and impaired spatial memory often observed in dementia, Parkinson’s disease (PD), multiple sclerosis (MS), progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Indeed, a correlational study implicated senescent T cells in influencing the progression or development of AD, as telomere length in T lymphocytes of AD patients was negatively associated with worse disease status [200, 201].

CD8 T cells are increasingly being recognized as potential drivers of neuronal damage, based on studies showing that they can directly target neurons or the myelin sheath and oligodendrocytes (ODCs) in both the CNS gray and white matter in vitro [202] and in vivo [203]. Importantly, neuropathologic studies have shown that CD8 T cells are the most numerous cell types in the inflammatory infiltrate in acute and chronic MS lesions gay [204]. Axonal damage in MS lesions correlates with the number of CD8 T cells [205, 206], and neurons and all other CNS cell types show increased MHC I expression [207]. Moreover, in patients suffering from MS with depressive symptoms, there are elevated levels of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β and TNFα, which correlate to greater negative behavioral consequences [208]. Collectively, these findings suggest that dysregulated CD8 T cells, including senescent cells, that accumulate in the elderly, could contribute as effector cells to the damage of glial and neuronal cells by direct recognition of MHC class I, as well as through the secretion of excessive inflammatory cytokines. However, to date, no group has explicitly investigated whether these infiltrating T cells in persons with MS have features of replicative senescence.

In contrast to the potential deleterious effects of CD8 T cells described above, there is a growing body of evidence documenting a beneficial, neuroprotective role of T cells after CNS damage and in certain neurodegenerative conditions. These T cells can help maintain homeostasis via their interactions with resident microglia, and they may also support neurogenesis. Mice deficient in CNS-specific T cells have reduced rates of hippocampal granular cell progenitor cell proliferation [209], and reduced spatial memory [199]. Regulation of a key molecule necessary for maintenance of brain plasticity, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), has been reported to be modulated by T cells, which can either produce it endogenously, or induce its production by glial cells [210–212]. Levels of BDNF production by hippocampal neurons were associated with CNS-specific T cell activity and, in situations of mental stress and depression, T cells were able to restore the reduced BDNF levels [209, 213]. Furthermore, during acute injury and neurodegenerative diseases, T cells can recuit monoctyes and act in tandem with resident microglia to remove excess toxins and debris, such as plaques seen in AD [214–216]. However, as noted previously, senescent T cells, which are show multiple alterations compared to non-senescent T cells, exhibit less ability to proliferate and secrete large quantities of inflammatory cytokines, features associated with negative outcomes in brain disorders. The emerging picture emphasizes the delicate balance between the normal physiological activity of T cells that supports brain health and the possibility that dysregulation of T cells in old age may negatively impact cognitive well-being.

T cell senescence and cardiovascular disease

As the most prevalent killer globally, cardiovascular diseases (CVD) involve complex sets of interactions between vascular endothelial cells and the immune system that lead to the development of cardiac and arterial pathologies. The principal cause of heart disease, myocardial infarction, and stroke is atherosclerosis, a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by lipid and cholesterol accumulation within the walls of large and medium arteries [217]. The immune system plays a major role in this process through the development of monocytes into foam cells upon exposure of oxidized lipids [218]. In addition, T cells have been documented to be present in atherosclerotic lesions [218–221] and vascular endothelial cells, macrophages and smooth muscle cells may communicate with T cells through CD40 [222] and secreted cytokines and chemokines [218].

By taking up a large proportion of the T cell antigen-receptor repertoire and interacting with vascular tissues, senescent T cells may modulate development of atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease. Indeed, epidemiological correlation studies show accelerated telomere shortening seen in patients with cardiovascular disease [223], atherosclerosis [224], and myocardial infarction [225]. Furthermore, patients with degenerative calcific aortic valve stenosis, an archetypal age-related cardiovascular disorder, were shown to have shorter PBMC telomeres than matched controls [226]. Shorter telomeres have also been associated with vascular dementia [95]. Moreover, a longitudinal study of 143 individuals also found that shorter PBMC telomere length at age 60 was associated with a 3.2-fold higher subsequent mortality rate from CVD [227]. Moreover, in HIV-infected persons, the presence of dysfunctional senescent T cells and their associated inflammatory and immunologic factors increases the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases. In one study, among the HIV-infected group, increased levels of T cell activation and a high proportion of senescent CD8 T cells were associated with an increased prevalence of carotid artery lesions. These effects persisted after adjustment for age, antiretroviral medication class, HIV RNA levels, and other cardiovascular disease risk factors [228].

Because these are associative studies, it is not yet known whether telomere shortening of T cells is increasing susceptibility to cardiovascular risk factors or, alternatively, if shorter telomeres are the byproduct of chronic systemic inflammation associated with cardiovascular diseases. However, the former possibility seems more likely, since the same cytokines secreted by senescent T cells (i.e., TNFα and IL-6) are also seen within atherosclerotic lesions. Furthermore, TNF-α and IL-6 facilitate a variety of functions that impact disease progression, including the enhanced recruitment of macrophages, and, therefore, foam cell formation [229]. Recent work in our lab suggests that exposure of CD8 T cells in long term culture to the same oxidized lipids that cause foam cell formation in vivo results in the enhancement of a number of senescence-like features, including reduced telomerase activity. Taken together, inflammatory mediators such as oxidized lipids and inflammatory cytokines may exert negative effects on T cells, enabling them to facilitate the development of vascular pathologies.

Interestingly, senescent T cells have been implicated in playing a role in diabetes mellitus, which in itself is associated to increase risk of having cardiovascular events. One recent study found that CD4+CD28− T cells, a rare long-lived subset of senescent T cells with proatherogenic and plaque-destabilizing properties, are expanded and are associated with poor glycemic control. The presence of these cells also correlates with the occurrence of a first cardiovascular event and with a worse outcome thereafter [230].

Stress and aging

An emerging body of work demonstrates the influential role of psychological health and the immune system. In this interdisciplinary field, termed psychoneuroimmunology, recent research has showed that many age-associated immune changes discussed in this review can be exacerbated by emotional stress such as in MS. Conversely, because T cells can cross the blood-brain barrier, their ability to function normally and regulate inflammation is key to neuronal and glial health. Dysregulated, senescent T cells that may be able to access and interact with brain cells can cause excessive secretion of inflammatory cytokines, which is often a symptom of age-related neurological diseases including Alzheimer’s disease.

It appears that the effects of both chronological and immunological aging, leading to the accumulation of senescent T cells in the T cell repertoire, can be exacerbated by psychological stress. Reduced antibody responsiveness to influenza vaccination has been documented in older caregivers of relatives with dementia. These caregivers also showed reduced telomerase activity versus matched controls [231]. A more recent study found that psychological stress, due to caring for a chronically ill child, is significantly correlated with higher oxidative stress, lower telomerase activity, and shorter telomere length in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy women [232, 233]. In fact, the mothers with the highest levels of perceived stress had, on average, telomere lengths of women 10 years older compared to low stress women. These findings suggest that, at the cellular level, stress may promote earlier onset of senescence, at least in PBMC, and possibly also age-related diseases.

Clinical depression is an important mental condition affecting millions of people, including the elderly, and associated with high levels of psychological stress. Inflammatory and oxidative stress markers, CRP, IL-1, and IL-6, are positively associated with clinical depression in a dose-dependent manner, indicating possible bidirectional crosstalk between senescent T cells and emotional response [234]. Indeed, it has been shown that psychological stress can boost inflammation [235] as well as oxidative stress [232], and both can accelerate telomere attrition [236]. Researchers compared persons with chronic depression versus a control group, and found that the depressed group, as a whole, did not differ from the controls in telomere length of their leukocytes, but individuals with more chronic courses of major depression had significantly shorter telomeres. The mean telomere length in the chronically depressed subjects was 281 base pairs shorter than that in controls, a difference that corresponded to approximately seven years of accelerated cell aging. [237]. Significantly, in HIV infected patients, depressive symptoms were significantly associated with higher viral load levels and altered CD8 T cell function [238]. Indeed, even among the HIV-negative population, psychological stress has been associated in a dose-response manner with an increased risk of acute infectious respiratory illness, specifically the common cold [239]. One explanation for these observations relates to cortisol, a major stress hormone that is elevated in depressed individuals [240]. Exposure of human T cells to cortisol in concert with activation results in a significant reduction in telomerase activity, a change that, over the long term, would be predicted to accelerate the progression to replicative senescence and, in turn, might lead to suppression of immune responses to vaccines and other antigenic interactions [241].

A decline in immune function can also arise in situations of extreme stress through the re-emergence of latent viruses including CMV and EBV, which we discussed as contributing drivers of replicative senescence. For example, physically healthy and fit astronauts have shown reactivation and viral shedding of CMV during spaceflight [242]. Some astronauts also show subclinical reactivation of the varicella zoster virus (VZV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) while levels of cortisol and catecholamines, both hormones involved in ‘fight-or-flight’ responses, were also elevated on the day of landing [243]. Other purportedly high-stressed individuals, such as medical students, showed increased expression of latent EBV during examination periods. Higher antibody titers to EBV IgG were identified at the time of examination, in contrast to 1 month prior to the exam [244, 245].

CD4 T cell senescence and autoimmunity

The primary focus of the discussion on replicative senescence has been on CD8 T cells, since this T cell subset undergoes the most dramatic phenotypic and functional changes during aging. However, recent efforts have begun to investigate the role of senescent CD4 T cells, characterized according to the same criteria described in CD8 T cell senescence, namely, loss of CD28 expression and telomerase activity, as well as shortened telomeres. When CD4 T cells, which normally function to orchestrate multiple signals between T cells, B cells and APCs, reach senescence, they acquire potent cytolytic abilities, a quality reserved primary to CD8 T subsets. Senescent CD4 T cells have been shown to kill endothelial cells [246], which may promote instability in atherosclerotic plaques. The purported senescent CD4 T cells are less common than their CD8 counterparts, but emerging reports suggest that the end-stage CD4 T cells may play an equally critical role in the development of age-related pathologies, particularly in the context of autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and Wengener’s granulomatosis, a rare type of small artery and vein inflammatory disease.

Elderly individuals suffer from autoimmunity more frequently [247] and autoimmune diseases are thought to lead to persistent immune stimulation, much like the situation of latent infections and cancers discussed earlier. The disease-causing autoantigens, though, are often unknown and are apparently not eliminated by the immune system, thus leading to repeated T cell activation. In the prototypic autoimmune disease, rheumatoid arthritis, which often afflicts the elderly, there is an increase frequency in CD28-negative CD4 T cells, which, like CD28-negative CD8 T cells, have been shown to have impaired telomerase activity [70].

The increased frequency of CD28-negative T cells in the elderly, discussed earlier, is often attributed to CMV infection, which is a major component of the IRP. Interestingly, the presence of CD4+CD28− T cells in several autoimmune diseases has been found to be accompanied by CMV infection. For example the expansion of CD28-negative CD4 T cells in Wegener’s granulomatosis and in RA has been strongly associated with CMV infection [248, 249]. Additionally, the T cell infiltrates in the muscle lesions of patients with Dermatomyositis and Polymyositis, both autoimmune connective tissue diseases, primarily consist of cells lacking CD28, and are CMV reactive [250]. However, it is still unclear the mechanism and extent to which CMV infection contributes to the expansion of CD28− CD4 T cells in persons with autoimmune diseases.

Additional information on CD4 T cell senescence is provided in studies on HIV-infected persons who are being treated with highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART). In those patients with low CD4 counts, there was greater expression of another senescence biomarker, CD57, on CD4 T cells compared to those with increased, reconstituted of CD4 T cell levels. The cohort with low CD4 T cell counts also showed reduced thymic activity, leading to a lower, more senescent-like CD4 T cell in the peripheral blood [251]. Together, these observations suggest that there are several different related mechanisms contributing to premature immune senescence in HIV-infected patients with low-level CD4 repopulation on HAART.

Future directions

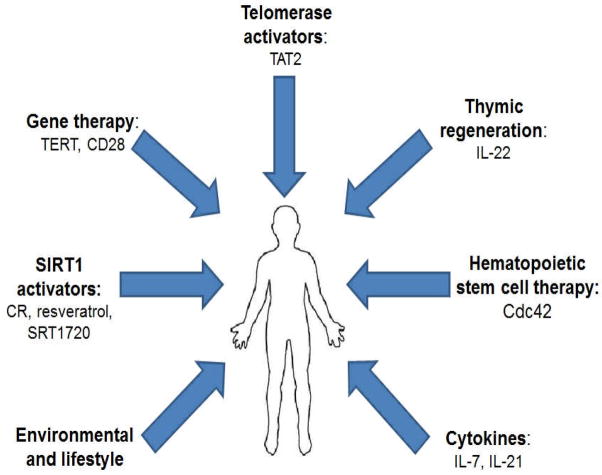

In this review, we have focused on the well-documented observation that senescent T cells, resulting, in part, from environmental factors such as exposure to chronic infections, constitute a significant proportion of the T cell compartment in elderly persons. There are several promising approaches to combating the decline of the immune system during aging or chronic infection, as summarized in fig. 1. Firstly, in considering strategies to prevent the generation of these cells, prophylactic childhood vaccination against CMV is an attractive option. In that regard, a preliminary report of a vaccine used to prevent primary CMV infection in pregnant CMV-seronegative mothers is quite encouraging [252]. It is also possible that development of a therapeutic vaccine, targeting both humoral and cellular immunity, might function to blunt the development of senescent CMV-specific T cells. However the challenge would be to elicit immunity that is more robust than the immunity resulting from natural infection, which we know does not achieve clearance of CMV from infected individuals. It is encouraging that a therapeutic vaccine against a different herpes virus, Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV), which is associated with shingles, has been moderately successful. Specifically, a 50–60% reduction of Zoster incidence was documented in the vaccinated vs. a matched control treated group [253], raising hopes that a similar vaccination strategy might be achievable for CMV. With the development of an effective CMV vaccine, it will be possible to (a) define the extent to which CMV infection contributes to immunological aging; and (b) possibly prevent or decrease the proportion of age-associated senescent T cells, and thus, their contribution to inflamm-aging.