Background: A limited number of cargoes specific for importin-β family nucleocytoplasmic transport carriers have been reported. We have developed a stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC)-based transport method to identify specific cargo.

Results: Candidate importin-β (with or without importin-α) cargoes were identified by our method and corroborated with binding assays.

Conclusion: New importin-β-specific cargoes were identified.

Significance: Our method has the potential to identify cargoes specific for other carriers.

Keywords: Mass Spectrometry (MS), Nuclear Pore, Nuclear Transport, Nucleus, Protein-Protein Interactions, Proteomics, SILAC, Importin, Nucleocytoplasmic Transport, Transportin

Abstract

The human importin (Imp)-β family consists of 21 nucleocytoplasmic transport carrier proteins, which transport thousands of proteins (cargoes) across the nuclear envelope through nuclear pores in specific directions. To understand the nucleocytoplasmic transport in a physiological context, the specificity of cargoes for their cognate carriers should be determined; however, only a limited number of nuclear proteins have been linked to specific carriers. To address this biological question, we recently developed a novel method to identify carrier-specific cargoes. This method includes the following three steps: (i) the cells are labeled by stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC); (ii) the labeled cells are permeabilized, and proteins in the unlabeled cell extracts are transported into the nuclei of the permeabilized cells by a particular carrier; and (iii) the proteins in the nuclei are quantitatively identified by LC-MS/MS. The effectiveness of this method was demonstrated by the identification of transportin (Trn)-specific cargoes. Here, we applied this method to identify cargo proteins specific for Imp-β, which is a predominant carrier that exclusively utilizes Imp-α as an adapter for cargo binding. We identified candidate cargoes, which included previously reported and potentially novel Imp-β cargoes. In in vitro binding assays, most of the candidate cargoes bound to Imp-β in one of three binding modes: directly, via Imp-α, or via other cargoes. Thus, our method is effective for identifying a variety of Imp-β cargoes. The identified Imp-β and Trn cargoes were compared, ensuring the carrier specificity of the method and illustrating the complexity of these transport pathways.

Introduction

A large number of proteins that participate in genetic processes, such as replication, transcription, or RNA processing, migrate into and out of the nucleus after they are synthesized in the cytoplasm. Ribosomal proteins also enter the nucleus and assemble into ribosomes. Thus, proper protein trafficking into the nucleus is crucial for many cellular activities (1). In interphase cells, proteins pass through nuclear pores in the nuclear envelope, but only a fraction of proteins penetrate the nuclear pores by free diffusion. Most nuclear proteins are transported by importin-β (Imp-β)3 family nucleocytoplasmic transport carrier proteins (Imp-βs) (2, 3), although recent reports have shown that a completely different type of carrier functions during the heat-stress response (4). Active transport by Imp-βs depends on the GTPase cycle of Ran, a small GTPase, which is essential for directionality of the transport (2, 3). An import carrier (importin) binds to a cargo protein in the cytoplasm and travels through a nuclear pore into the nucleus, where the GTP-bound form of Ran (RanGTP) is enriched. Once RanGTP binds to the carrier, the cargo is released from the carrier. Conversely, an export carrier (exportin) forms a trimeric complex with a cargo protein and RanGTP in the nucleus, and this complex traverses a nuclear pore to exit the nucleus. Following GTP hydrolysis, the complex dissociates to release the cargo. The human genome encodes 21 species of Imp-βs, which include 12 importins, 7 exportins, and 2 bidirectional carriers (5, 6).

The 21 Imp-βs are responsible for transporting thousands of proteins, and Imp-β cellular levels may vary depending on specific cellular contexts such as during spermatogenesis (7) or in specific sites, including brain tissues (8) and plant tissues (9). The expression of some Imp-βs is dependent on the circadian rhythm (8) or cellular response to stimuli (9). Each carrier is expected to transport a specific group of cargoes, although some cargoes are transported by multiple carriers. Cargoes that are transported by the same carrier must all share a specific nuclear localization signal (NLS), but most NLS sequences specific for Imp-βs have not been identified (10). Importantly, cargo proteins transported by a specific carrier may share specific functions; for example, a majority of known transportin (Trn) cargo proteins are RNA-binding proteins. Moreover, several known Trn-SR cargoes are SR-proteins (10). To understand the cargo-carrier interaction network and the physiological significance of each carrier, the cargo specificity must be established for each Imp-β carrier. To date, only a limited number of cargoes have been linked to specific carriers, and some carriers have no validated cargo proteins. To address this issue, we recently developed a novel SILAC-based (11) in vitro transport (SILAC-Tp) method to identify carrier-specific cargoes, and this method identified Trn-specific cargoes (12). The method was validated using bead halo assays (13), which detect the physical interactions between the identified cargoes and Trn.

Here, we applied the method to identify cargo proteins specific for Imp-β in the presence of Imp-α (Imp-α/β). Imp-β is the best characterized carrier, and it imports the majority of nuclear proteins in various ways. Imp-β directly binds to some of its cargo proteins, and it is the only carrier among the 21 Imp-βs that utilizes all seven (14) Imp-α family proteins (Imp-αs) as adapters for cargo binding (2, 3, 15). Hence, many cargoes imported through the Imp-β-dependent pathway have been identified as cargoes that bind to Imp-αs. Furthermore, Imp-α binding sites on the cargo proteins have been characterized as classical NLS (cNLS) sequences (16, 17). Although many of the Imp-α binding cargoes were identified separately in independent studies, some of these interactions were identified using systematic approaches. Screening synthetic libraries, such as in vitro virus libraries (18) and oriented peptide libraries (19), is effective for identifying amino acid sequences that bind to Imp-α and act as cNLSs, but these methods do not identify native cargoes. The identification of native Imp-α cargoes was performed using Far Western-based cellular proteomic approaches (20), yeast two-hybrid screening (21), GST pulldown assays (22, 23), and co-immunoprecipitation techniques (24). These methods depend on the protein-protein interaction between Imp-α and its cargo. Our SILAC-Tp method is unique because it includes an in vitro transport reaction. One advantage of this method is that cargo proteins accumulate in the nuclei regardless of whether the cargo-carrier interaction is short-lived or dissociates during pulldown experiments. For Trn, the SILAC-Tp method identified a set of cargoes that partly overlapped, but differed considerably from those identified by other binding-based methods, indicating that our method can complement conventional methods (12).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Buffers, the ATP regeneration system, antibodies, cytosolic, and nuclear extract preparations, and the evaluation of the transport system were described previously (12).

Proteins

The amino acid sequences of the recombinant proteins used in the bead halo assays are denoted by accession numbers in supplemental Table S1. Sequences are described for proteins whose cDNA sequences were not present in the database. GFP fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli, and the extracts were prepared as described previously (12). The GFP moiety in the E. coli extracts was quantified three times by Western blotting (supplemental Fig. S1, A–F). Intact recombinant proteins were expressed using the pColdII vector (Takara, Otsu, Japan), according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the extracts (supplemental Fig. S1G) were prepared as described previously (12). The Imp-α subtype used in this study was Imp-α2. GST-Imp-αΔN is a GST fusion of Imp-α2 and lacks the N-terminal 63 residues; these residues include the Imp-β binding domain (25–27). GST-Imp-αΔN was expressed using the pGEX-6p-3 vector (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and purified as described previously (12). Intact Imp-α4 (supplemental Fig. S4) was also prepared using an identical method to the intact Imp-α2 preparation (12). All of the other recombinant proteins were prepared as described previously (12).

SILAC-Tp

The SILAC-Tp method (supplemental Fig. S2) was described previously (12). For the in vitro transport reaction with Imp-α and Imp-β (+Imp-α/β), 2 μm Imp-α2 and 1 μm Imp-β were added. The entire SILAC-Tp experiment for the identification of Imp-α/β cargo was conducted simultaneously with the control (Ctl) and +Trn SILAC-Tp experiment, which was described previously (12).

Protein Identification and Quantification by LC-MS/MS

SDS-PAGE and protein in-gel digestion of the +Imp-α/β sample were performed simultaneously with the Ctl and +Trn samples as described previously (12). LC-MS/MS analysis using a nanoflow LC/linear ion-trap/time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Hitachi NanoFrontier LD) was conducted as described previously (12). The LC-MS/MS data were also analyzed in parallel. Protein hits were filtered using a significance threshold (p < 0.05), and only high quality peptide peaks exceeding threshold values (intensity >300, charge ≥+2, S.E. <0.1, fraction >0.5, and correlation >0.8, as defined by Quantitation Toolbox of Mascot Distiller (Matrix Science, London, UK)) were considered for quantification (12). Proteins that satisfied these criteria are listed in supplemental Table S2, and peptides quantified for each parent protein are provided in supplemental Table S3. For each parent protein, arithmetic mean light/heavy (L/H) ratios were calculated separately for peptides from the Ctl and +Imp-α/β samples (L/HCtl and L/Hαβ, respectively). The αβ/C value (calculated as (L/Hαβ)/(L/HCtl)), which corresponds to the T/C value ((L/HTrn)/(L/HCtl)) in the Trn cargo identification study, indicates the cargo potentiality of each protein. To select proteins with highly reliable αβ/C values, two arbitrary thresholds were applied to the L/H ratios. First, to pre-clear proteins that bound non-specifically to the permeabilized cells, heavily bound proteins with L/HCtl ratios >1.1 were removed; this cutoff was chosen based on the frequency distribution of the L/HCtl ratios (Fig. 1A). Second, to avoid inaccuracies near the lower limit of relative quantification, the L/HCtl and L/Hαβ ratios were required to be >0.03. Thus, 0.03 < L/HCtl < 1.1 and 0.03 < L/Hαβ were the criteria used to identify highly reliable αβ/C values. The proteins that met all of these thresholds are listed in Table 1. To calculate the αβ/C value, both the L/HCtl and L/Hαβ ratios must be quantified for one protein, and to calculate the T/C value, both the L/HCtl and L/HTrn values must be quantified. Therefore, the protein set identified with valid αβ/C values differs slightly from the protein set identified with valid T/C values, although the control data set is the same for the αβ/C and T/C calculations.

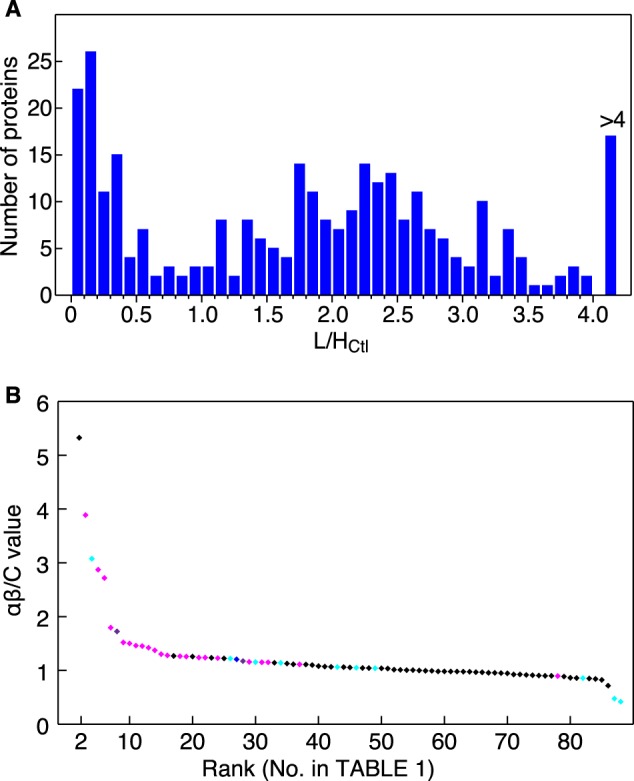

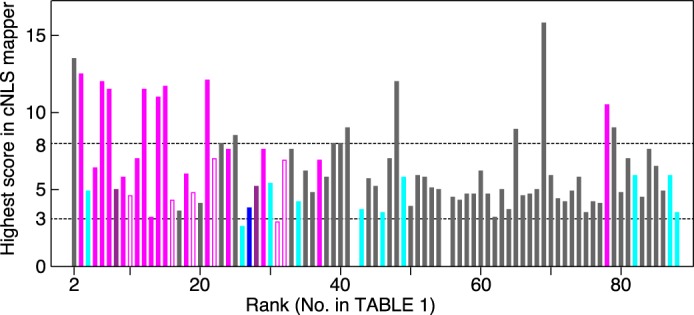

FIGURE 1.

αβ/C values predict Imp-α/β cargoes. A, frequency distribution of L/HCtl ratios. Both L/HCtl and L/Hαβ ratios were calculated for 307 proteins, and distribution of the 307 L/HCtl ratios is illustrated. B, protein ranking by a reliable αβ/C value. Proteins quantified reliably by MS (88 proteins with 0.3 < L/HCtl < 1.1 and 0.03 < L/Hαβ) were ranked in descending αβ/C value order (Table 1). Horizontal, protein rank; vertical, αβ/C value. IMB1 (Imp-β) ranked at the top is not shown. The results of the bead halo assays are indicated by the following colors: magenta, bound to Imp-α or Imp-β directly; violet, bound to Imp-α via another cargo protein; blue, unclear; cyan, not bound to Imp-α or Imp-β; and black, not assayed.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the results

Identified proteins with highly reliable quantification are ordered by descending αβ/C value.

| No. | Proteina | Mass (Da) | L/HCtlb | L/Hαβc | αβ/Cd | Bead haloe | NLS scoref | Referenceg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Da | ||||||||

| 1 | IMB1 | 98,420 | 0.041 | 1.052 | 25.465 | 3.1 | ||

| 2 | SRRT | 101,060 | 0.045 | 0.239 | 5.324 | 13.5 | α,β (41–43)h | |

| 3 | PSME3 | 29,602 | 0.904 | 3.515 | 3.887 | α ++ | 12.5 | |

| 4 | GRP78 | 72,402 | 0.243 | 0.748 | 3.075 | − | 4.9 | |

| 5 | HNRPU | 91,269 | 0.071 | 0.204 | 2.872 | α ++ | 6.4 | |

| 6 | LMNA | 74,380 | 0.037 | 0.101 | 2.718 | α + | 12 | |

| 7 | DHX15 | 91,673 | 0.555 | 0.997 | 1.795 | α ++ | 11.5 | α5 (22) |

| 8 | ROA2 | 37,464 | 0.040 | 0.068 | 1.724 | − (+ HNRPK/U) | 5 | |

| 9 | APEX1 | 35,931 | 0.948 | 1.441 | 1.520 | α ++ | 5.8 | α1,2 (50) |

| 10 | ERP29 | 29,032 | 0.086 | 0.130 | 1.501 | β + | 4.6 | |

| 11 | SET | 33,469 | 1.031 | 1.506 | 1.461 | α ++ | 7 | α3 (30) |

| 12 | MCM3 | 91,551 | 0.350 | 0.508 | 1.452 | α + | 11.5 | |

| 13 | SNRPA | 31,259 | 0.122 | 0.173 | 1.422 | α + | 3.2 | α2 (40) |

| 14 | MCM2 | 102,516 | 0.577 | 0.793 | 1.373 | α + | 11 | |

| 15 | CBX3 | 20,969 | 0.189 | 0.246 | 1.302 | α ++ | 11.7 | |

| 16 | SMD3 | 14,021 | 0.314 | 0.402 | 1.279 | β ++ | 4.3 | |

| 17 | NHP2 | 17,532 | 0.104 | 0.132 | 1.269 | 3.6 | ||

| 18 | XRCC5 | 83,222 | 0.349 | 0.441 | 1.264 | α+ | 6 | α2 (51) |

| 19 | RL18A | 21,034 | 0.129 | 0.163 | 1.257 | β + | 4.8 | β, Imp-9b (44) |

| 20 | CPSM | 165,975 | 0.047 | 0.059 | 1.257 | 4.1 | ||

| 21 | HNRPK | 51,230 | 0.597 | 0.739 | 1.238 | α ++ | 12.1 | α1,3–5,7 (22, 52) |

| 22 | RL27 | 15,788 | 0.120 | 0.148 | 1.237 | β ++ | 7 | β (12) |

| 23 | SF3B2 | 97,710 | 0.492 | 0.607 | 1.234 | 8 | ||

| 24 | NUCL | 76,625 | 0.139 | 0.170 | 1.228 | α + | 7.6 | α1 (53) |

| 25 | PRKDC | 473,749 | 0.181 | 0.221 | 1.223 | 8.5 | ||

| 26 | PCNA | 29,092 | 0.756 | 0.923 | 1.221 | − | 2.6 | β (54) |

| 27 | RLA0L | 34,514 | 0.195 | 0.235 | 1.206 | αβ ± | 3.8 | |

| 28 | MCM6 | 93,801 | 0.590 | 0.692 | 1.173 | − (+ MCM2) | 5.2 | |

| 29 | NPM | 32,726 | 0.081 | 0.094 | 1.158 | α ++ | 7.6 | α1,3–5,7 (52, 55) |

| 30 | ROAA | 36,316 | 0.143 | 0.165 | 1.154 | − | 5.4 | |

| 31 | CNBP | 20,704 | 0.506 | 0.582 | 1.151 | α +, β + | 2.9 | |

| 32 | TXND5 | 48,283 | 0.062 | 0.071 | 1.150 | β + | 6.9 | |

| 33 | PARP1 | 113,811 | 0.149 | 0.170 | 1.142 | 7.6 | ||

| 34 | PDIA6 | 48,490 | 0.078 | 0.089 | 1.139 | − | 4.2 | |

| 35 | RL27A | 16,665 | 0.120 | 0.135 | 1.128 | 6.2 | ||

| 36 | SF3B3 | 136,575 | 0.698 | 0.778 | 1.114 | 4.8 | ||

| 37 | XRCC6 | 70,084 | 0.405 | 0.450 | 1.112 | α ++ | 6.9 | α1,2 (20, 56) |

| 38 | RL7 | 29,264 | 0.105 | 0.116 | 1.110 | 5.8 | β3 (57) | |

| 39 | AN32E | 30,902 | 1.015 | 1.116 | 1.099 | 8 | α1,2 (58) | |

| 40 | RL26 | 17,248 | 0.118 | 0.128 | 1.080 | 8 | ||

| 41 | DNMT1 | 185,388 | 0.556 | 0.596 | 1.071 | 9 | α2 (59) | |

| 42 | RS29 | 6,900 | 0.295 | 0.315 | 1.065 | |||

| 43 | SERA | 57,356 | 0.547 | 0.580 | 1.062 | − | 3.7 | |

| 44 | ALDR | 36,230 | 0.323 | 0.343 | 1.061 | 5.7 | ||

| 45 | RS3A | 30,154 | 0.294 | 0.310 | 1.054 | 5.2 | ||

| 46 | RS12 | 14,905 | 0.296 | 0.310 | 1.049 | − | 3.5 | |

| 47 | PDIA3 | 57,146 | 0.109 | 0.114 | 1.045 | 7 | ||

| 48 | NSUN2 | 87,214 | 0.403 | 0.420 | 1.043 | 12 | ||

| 49 | PPIB | 23,785 | 0.114 | 0.119 | 1.040 | − | 5.8 | |

| 50 | RL11 | 20,468 | 0.147 | 0.153 | 1.039 | 3.9 | ||

| 51 | RL7A | 30,148 | 0.130 | 0.135 | 1.034 | 5.9 | ||

| 52 | RS23 | 15,969 | 0.272 | 0.275 | 1.014 | 5.8 | ||

| 53 | RS9 | 22,635 | 0.281 | 0.284 | 1.010 | 5.1 | ||

| 54 | ACTN4 | 105,245 | 0.489 | 0.491 | 1.005 | 5 | ||

| 55 | RS28 | 7,893 | 0.266 | 0.267 | 1.005 | |||

| 56 | GBLP | 35,511 | 0.351 | 0.350 | 0.998 | 4.5 | ||

| 57 | PABP1 | 70,854 | 0.644 | 0.640 | 0.993 | 4.3 | ||

| 58 | BTF3 | 22,211 | 0.851 | 0.844 | 0.991 | 4.7 | ||

| 59 | RS25 | 13,791 | 0.334 | 0.328 | 0.981 | 4.7 | ||

| 60 | RL12 | 17,979 | 0.136 | 0.133 | 0.981 | 6.2 | ||

| 61 | RS10 | 18,886 | 0.306 | 0.300 | 0.980 | 4.7 | ||

| 62 | RS2 | 31,590 | 0.370 | 0.362 | 0.979 | 3.2 | α (60) | |

| 63 | TERA | 89,950 | 1.045 | 1.020 | 0.976 | 5 | ||

| 64 | RLA2 | 11,658 | 0.220 | 0.215 | 0.975 | 3.7 | ||

| 65 | RL24 | 17,882 | 0.149 | 0.144 | 0.967 | 8.9 | ||

| 66 | RS19 | 16,051 | 0.313 | 0.302 | 0.965 | 4.6 | ||

| 67 | PAIRB | 44,995 | 0.342 | 0.327 | 0.956 | 4.7 | ||

| 68 | RL17 | 21,611 | 0.149 | 0.142 | 0.955 | 5 | ||

| 69 | RS8 | 24,475 | 0.286 | 0.271 | 0.950 | 15.8 | ||

| 70 | RS13 | 17,212 | 0.304 | 0.288 | 0.946 | 5.9 | ||

| 71 | RAB7A | 23,760 | 0.875 | 0.810 | 0.925 | 4.4 | ||

| 72 | IF2A | 36,374 | 0.912 | 0.844 | 0.925 | 4.2 | ||

| 73 | EIF3A | 166,867 | 0.784 | 0.718 | 0.916 | 4.9 | ||

| 74 | RL14 | 23,531 | 0.142 | 0.129 | 0.910 | 5.8 | ||

| 75 | PDCD6 | 21,912 | 0.037 | 0.033 | 0.905 | 3.5 | ||

| 76 | RS18 | 17,708 | 0.328 | 0.295 | 0.899 | 4.2 | ||

| 77 | RS11 | 18,590 | 0.311 | 0.279 | 0.899 | 4.1 | ||

| 78 | HNRPQ | 69,788 | 0.729 | 0.652 | 0.895 | α + | 10.5 | |

| 79 | RS3 | 26,842 | 0.347 | 0.308 | 0.886 | 9 | ||

| 80 | RS4X | 29,807 | 0.284 | 0.246 | 0.863 | 4.8 | ||

| 81 | RL4 | 47,953 | 0.143 | 0.123 | 0.858 | 7 | β/Imp-7-dimer (44) | |

| 82 | ROA1 | 38,837 | 0.086 | 0.074 | 0.856 | − | 5.9 | |

| 83 | RS7 | 22,113 | 0.347 | 0.295 | 0.850 | 4.5 | β (36) | |

| 84 | RL19 | 23,565 | 0.127 | 0.107 | 0.841 | 7.6 | ||

| 85 | RSMB | 24,765 | 0.297 | 0.244 | 0.823 | 6.5 | ||

| 86 | RL18 | 21,735 | 0.116 | 0.083 | 0.716 | 4.9 | ||

| 87 | HNRPD | 38,581 | 0.133 | 0.063 | 0.475 | − | 5.9 | |

| 88 | HNRDL | 46,580 | 0.177 | 0.074 | 0.418 | − | 3.5 |

a Entry name in UniProt.

b Light/heavy ratio in control reactions.

c Light/heavy ratio in +Imp-α/β reactions.

d αβ/C = (L/Hαβ)/(L/HCtl).

e Result of the bead halo assay. α, bound to Imp-α; β, bound to Imp-β; ++, bound strongly; +, bound weakly; −, not bound; ±, unclear because of degradation; (+), bound to Imp-α in the presence of indicated protein.

f Highest NLS score calculated by cNLS mapper.

g Reported carrier; α, Imp-α; β, Imp-β. Subtype of carrier is indicated when it is defined.

h Indirect binding is suggested by previous reports.

Bead Halo Assay

Normalized extracts of E. coli expressing a GFP fusion protein (supplemental Fig. S1, A–F), GSH-Sepharose, and one of GST, GST-ImpαΔN, GST-Imp-β, or GST-Imp-β with intact Imp-α were mixed in EHBN buffer (10 mm EDTA, 0.5% 1,6-hexanediol, 10 mg/ml of BSA, and 125 mm NaCl) as described previously (12, 13). To determine whether GFP fusion proteins indirectly bind to Imp-α or Imp-β via a complex containing their binding partners, extracts of E. coli expressing the GFP fusion protein and the intact binding partner protein (supplemental Fig. S1G) were pre-mixed and incubated for 20 min at 30 °C, and then assayed similarly. A GTP-fixed Q69L-Ran mutant (28), which inhibits the Imp-β–cargo and Imp-β–Imp-α interactions, was added when appropriate. After incubation for 20–30 min, the mixtures were observed by fluorescence microscopy.

RESULTS

Identification of Imp-α/β-specific Cargoes by SILAC-Tp

The SILAC-based method has been reported previously (12), which is briefly reproduced in supplemental Fig. S2. The in vitro transport reaction containing Imp-α/β was conducted simultaneously with the control reaction lacking Imp-α/β. Database search parameters were applied as described (12), and greater than 660 and 630 proteins were identified in the permeabilized cell extracts after the Ctl and +Imp-α/β transport reactions, respectively. Of these identified proteins, 479 proteins appeared in both extracts. The proteins were filtered by significance thresholds (p < 0.05), and the peptide spectra were compared with quality threshold values (see “Experimental Procedures”). Following these quality control steps, 307 proteins were identified with valid L/HCtl and L/Hαβ ratios. The αβ/C value ([L/Hαβ]/[L/HCtl]), similar to the T/C value used in the Trn cargo identification study (12), was used as an index of cargo potentiality. The 307 proteins are listed in descending αβ/C value order in supplemental Table S2, and the αβ/C values are graphically illustrated in supplemental Fig. S3. Highly ranked proteins with prominent αβ/C values are expected to be specific Imp-α/β cargo proteins. As was performed in the study identifying Trn-specific cargo, we further verified the potential cargo proteins with low L/HCtl ratios. The proteins with high L/HCtl ratios were likely binding non-specifically to the permeabilized cells (12). The frequency distribution of the L/HCtl ratios (Fig. 1A) indicated that the proteins could be divided into the following two groups: 1) low binding proteins with an L/HCtl ratio <1.1 and 2) high binding proteins with an L/HCtl ratio >1.1. We further analyzed the low binding proteins. We also removed proteins with an L/HCtl or L/Hα/β ratio <0.03 to avoid imprecision near the lower limit of relative quantification. After applying these criteria, 88 proteins were selected for further analysis, and they are listed in Table 1 in descending αβ/C value order and graphically illustrated in Fig. 1B. Hereafter, the proteins are referred to by their assigned number in Table 1. Protein 1 is the Imp-β that was added to the transport reaction. The 88 proteins in Table 1 include known Imp-α/β cargoes or interacting proteins, and most of them are ranked high on the list, ranging from the 2nd to 41st. Thus, ranking the potential cargo proteins by their αβ/C values seems to correlate with cargo potentiality. As Imp-α/β is the predominant carrier and imports many cargoes, the import capacity for each cargo may be reduced, and some cargoes (e.g. proteins 62 and 83) may not have been imported efficiently. Other possibilities for inefficient cargo identification are also discussed below (see “Discussion”). Despite these inefficiently imported cargo proteins, the results in Table 1 support the capability of the SILAC-Tp method to practically identify Imp-α/β-specific cargoes.

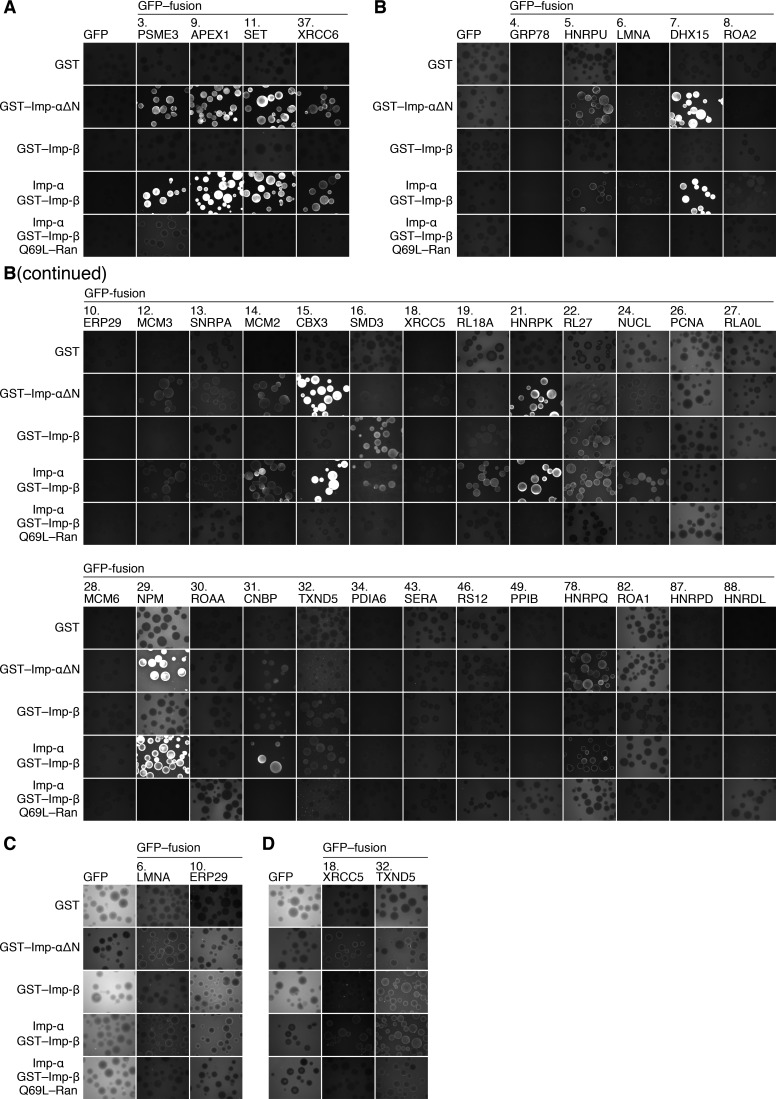

Interaction between Identified Cargoes and Imp-α or Imp-β

We examined the physical interaction between the identified candidate cargoes and Imp-α, Imp-β, and Imp-α/β with a bead halo assay (13) (Fig. 2). For this assay, the binding of a GFP fusion protein to a GST fusion protein on the surface of GSH-Sepharose beads is observed by fluorescence microscopy. Most of the highly ranked proteins and several of the lower ranked proteins that were randomly selected were expressed in E. coli as GFP fusion proteins. For detection of the cargo-Imp-α interactions, we used GST-Imp-αΔN, which is a GST fusion of an Imp-α2 that lacks the N-terminal 63 residues. The Imp-β binding domain at the N terminus of Imp-α inhibits cargo binding in the absence of Imp-β (29). Direct binding of cargo to Imp-β was examined using GST-Imp-β alone. In the presence of GST-Imp-β and intact Imp-α simultaneously, direct binding to Imp-β and indirect binding via Imp-α can be detected. Thus, the binding mode (direct binding to Imp-β, indirect binding to Imp-β via Imp-α, or a mixture of the two modes) can be determined by comparing results from the three assays. Q69L-Ran, a GTP-fixed mutant form of Ran, inhibits the specific binding of Imp-β to cargo and Imp-α (28), and this molecule was used to assess binding specificity. The results from the bead halo assays are summarized in Table 1. Of the 28 highly ranked proteins (rank ≤37) that were assayed, 15 proteins (proteins 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 18, 21, 24, 29, and 37) bound to Imp-β mainly via Imp-α, and 5 proteins (proteins 10, 16, 19, 22, and 32) bound to Imp-β directly. Finally, 1 protein (protein 31) bound to Imp-β both via Imp-α and directly, and 6 proteins (proteins 4, 8, 26, 28, 30, and 34) were incapable of binding to either Imp-α or Imp-β. The binding mode of protein 27 was unclear, possibly due to extensive degradation of the molecule (supplemental Fig. S1), but it ambiguously bound to Imp-β only in the presence of Imp-α. Conversely, of the seven lower ranked proteins (rank ≥43) that were assayed, only 1 protein (protein 78) bound to Imp-β via Imp-α. The other 6 proteins (proteins 43, 46, 49, 82, 87, and 88) were unable to bind to either carrier. Proteins that were highly ranked by the SILAC-Tp method and verified to bind to the carrier can be regarded as bona fide cargoes. Hence, 22 species, including established and novel Imp-β cargoes, were identified by the SILAC-Tp method in this study, and these cargo proteins can directly bind to Imp-β or interact via Imp-α. Of the 22 verified cargo proteins, two (proteins 7 and 11) have been reported to bind to other subtypes of Imp-αs (22, 30), but our results indicate that they are Imp-α2-dependent cargoes as well.

FIGURE 2.

Interaction of candidate cargoes with Imp-α or Imp-β. Cargo-carrier interactions were analyzed by a bead halo assay. Bacterial extract containing a GFP fusion protein was mixed with GSH-Sepharose beads and one of GST, GST-Imp-αΔN, GST-Imp-β, Imp-α/GST-Imp-β, or Imp-α/GST-Imp-β/Q69L-Ran. The interactions were observed by fluorescence microscopy. The extracts were normalized for the GFP moiety and total protein concentration following quantitative Western blotting (supplemental Fig. S1). Q69L-Ran inhibits specific interactions between Imp-β and the cargo or Imp-α. The images within each panel are comparable. Protein numbers are identical to those in Table 1. A, cargo proteins that bound very strongly to Imp-α. The exposure time was shorter than that for panel B. B, images taken using standard conditions. C and D, enhanced images for proteins 6, 10, 18, and 32. These images show faint but detectable signals.

Six proteins (proteins 4, 8, 26, 28, 30, and 34) with high αβ/C values did not bind to Imp-α2 in the bead halo assays. In our transport system, Imp-β proteins in the cell extracts are depleted effectively (4, 12), but Imp-αs are not. Thus, these six proteins may have been transported by other endogenous Imp-α subtypes that exist in the cell extract. We then assayed the binding of these proteins to Imp-β via Imp-α4, which belong to a different subfamily (15). However, the binding specificities were very similar for Imp-α2 and Imp-α4 in the bead halo assays (supplemental Fig. S4).

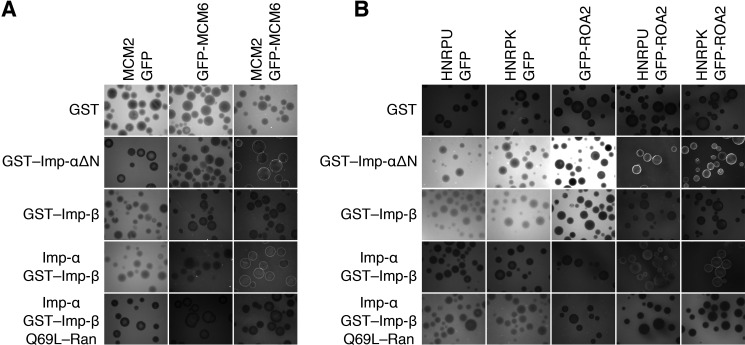

Cargo Complexes

In principle, the SILAC-Tp method can identify protein complexes as cargo, and some subunits of the cargo complex may not bind to Imp-β or Imp-α directly in the bead halo assay. Indeed, some highly ranked proteins in Table 1 are likely components of cargo complexes, including the MCM2–7 complex (31) (proteins 12, 14, and 28), the spliceosome C complex (32) or the mRNP granule complex (33) (proteins 5, 8, 21, and 39), and the DNA-PK complex (34) (proteins 18 and 37). For the MCM2–7 complex, GFP fusions of both MCM2 and MCM3 bound to Imp-α/β in the bead halo assays, but the GFP fusion of MCM6 did not (Fig. 2). However, in the presence of intact MCM2, the GFP fusion of MCM6 bound to Imp-β via Imp-α (Fig. 3A), suggesting that MCM6 was imported in the SILAC-Tp assay as a component of the MCM2–7 complex. Similarly, GFP fusions of the spliceosome C or mRNP granule complex components, HNRPU and HMRPK, bound to Imp-α/β, but a GFP fusion of ROA2 did not bind to Imp-α/β (Fig. 2). In the presence of intact HNRPU or HNRPK, however, the GFP fusion of ROA2 bound to Imp-β via Imp-α (Fig. 3B), suggesting that ROA2 was transported as a component of the complex. Thus, the SILAC-Tp method is capable of identifying cargo proteins that bind to Imp-α/β indirectly via complexing with other cargoes.

FIGURE 3.

Cargo complexes. Candidate cargoes that did not bind directly to Imp-α or Imp-β (Fig. 2) were examined for indirect binding via other cargoes by a bead halo assay. A, components of the MCM2–7 complex. GFP-MCM6 was assayed for binding to Imp-α or Imp-β in the presence or absence of intact MCM2, which binds to Imp-α (Fig. 2). B, components of the spliceosome C or mRNP granule complex. GFP-ROA2 was assayed in the presence or absence of intact HNRPU or HNRPK, which bind to Imp-α (Fig. 2). Assays were conducted as described in the legend to Fig. 2, but the images are enhanced. Images within each panel are comparable.

cNLS Sequences in the Identified Cargo Proteins

The Imp-β-specific cargoes identified above bound to Imp-β through one of three binding modes: direct, via another cargo, or via Imp-α. Imp-α binding sequences have been characterized as cNLS sequences, which can be grouped into two classes, monopartite and bipartite cNLSs. These classes can be further subdivided into several additional classes (16, 17). All cNLS classes in a protein can be predicted by computational scoring of the protein sequence. The NLS scores calculated by the “cNLS mapper” program (35) for all of the identified proteins are listed (Table 1 and supplemental Table S2) and illustrated in Fig. 4 by the order of their αβ/C values. Broadly, proteins with higher NLS scores (>8) were also highly ranked by their αβ/C values. Some proteins with lower NLS scores (<8) were highly ranked by their αβ/C values, and many of these proteins bound to Imp-β directly or to Imp-α as part of a complex. Thus, the SILAC-Tp method can effectively identify cargoes with and without cNLS sequences.

FIGURE 4.

cNLS sequences in the identified proteins. NLS scores, which were defined by the cNLS mapper program, were calculated and are shown for proteins listed in Table 1. For proteins with two or more predicted cNLS sequences, the highest NLS score was used. Vertical, NLS score; horizontal, protein rank in Table 1. The results of the bead halo assays are indicated by the following colors: filled magenta, bound to Imp-α; open magenta, bound to Imp-β; violet, bound to Imp-α indirectly; blue, unclear because of degradation; cyan, not bound to Imp-α or Imp-β; and gray, not assayed. Roughly, exclusive nuclear or cytoplasmic localization is predicted by a score of >8 or <3 (dashed lines), respectively.

DISCUSSION

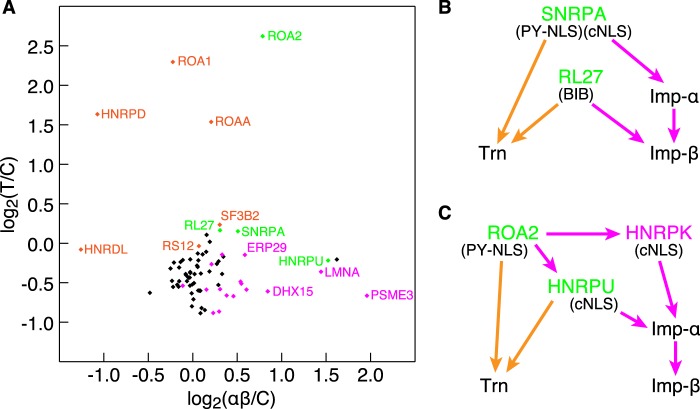

We have identified Imp-α/β-specific cargoes using the SILAC-Tp method, which we previously employed to identify Trn-specific cargoes (12). Among the proteins that satisfied the quality control thresholds of peptide mass spectra in these experiments, 77 proteins with 0.03 < L/HCtl < 1.1, 0.03 < L/HTrn, and 0.03< L/Hαβ were assigned with both of the highly reliable T/C and αβ/C values. These included 20 proteins, which bound to Imp-β either directly or indirectly (Figs. 2 and 3), and nine proteins, which bound to Trn in our previous report (12). Of them, 4 proteins (proteins 5, 8, 13, and 22 in Table 1) bound to both Trn and Imp-β, 16 proteins bound to Imp-β but not to Trn (supplemental Fig. S5), and 5 proteins bound to Trn but not to Imp-β. In the previous article (12) and present bead halo assays, we selected most of the proteins that were highly ranked by T/C (rank ≤18; see Ref. 12) or αβ/C (rank ≤34; this study, Table 1) values and assayed them for both Imp-α/β and Trn binding, if the GFP fusion proteins were available. In addition, we selected randomly some of the proteins with both a low T/C value (in the previous study, see Ref. 12) and a low αβ/C value (in this study) and assayed them, but few of them bound to the carriers. Thus, only a few proteins that show low T/C and αβ/C values are expected to bind to the carriers, although many of them were not assayed. The T/C and αβ/C values of the 77 proteins are plotted against each other in Fig. 5A, which shows no correlation between these values (r < 0.05). Within the scatter plot, cargoes that bound to Trn but not to Imp-α/β in the bead halo assays are located in the upper left quadrant, and cargoes that bound to Imp-α/β but not to Trn are found in the lower right quadrant. Cargoes that bound to both proteins are in the upper right quadrant. These clearly indicate that the SILAC-Tp method reproduces carrier-cargo specificity; therefore, the method can be applied to determine the cargoes of a variety of carriers.

FIGURE 5.

Identified Imp-α/β and Trn cargoes. A, αβ/C and T/C values. Log2(αβ/C) is plotted against log2(T/C) for 77 proteins that were quantified based on highly reliable quality control values (0.03 < L/HCtl < 1.1, 0.03 < L/HTrn, and 0.03 < L/Hαβ). The following colors indicate the results of the bead halo assay: orange, bound to Trn but not to Imp-α or Imp-β; magenta, bound to Imp-α or Imp-β but not to Trn; green, bound to both; black, not assayed or not bound to either. Proteins with prominent values are labeled. B and C, bi-pathway cargoes. Green letters, bi-pathway cargo; magenta letters, Imp-β cargo; orange arrow, protein-protein interaction suggestive of the Trn pathway; and magenta arrow, suggestive of the Imp-β pathway. NLS types engaging in the interactions are denoted.

cNLSs, which are recognized by Imp-αs, have been well characterized (16, 17), but structural determinants for direct binding of Imp-β are divergent (17) and lack defined consensus sequences. Many Trn binding sequences have been characterized as M9 (36) or proline-tyrosine NLSs (37, 38), and naturally, some Trn cargoes that were identified in our study encoded these sequences (12). Another type of Trn binding sequence is the β-like import receptor binding domain, which acts as an NLS in rpL23A for several Imp-βs including Imp-β and Trn (39). Previously, we demonstrated that it exists in numerous cargoes, although its consensus sequence is still obscure (12). These various types of NLS sequences enhance the complexity of the transport system. We identified the four proteins (proteins 5, 8, 13, and 22) as “bi-pathway” cargoes, which means that they can be imported by both Trn and Imp-β. Moreover, the types of NLS sequences encoded by the cargo proteins and the protein-protein interactions that include these cargoes are unique to each cargo protein (Fig. 5, B and C). The SNRPA protein contains two discrete NLS sequences, cNLS and a proline-tyrosine NLS; Imp-α binds to the cNLS, and Trn binds to the proline-tyrosine NLS (12, 40). RL27 interacts with both carriers via a β-like import receptor binding domain (12). HNRPU binds to Trn through an unidentified NLS (12), and it binds to Imp-α likely through a cNLS that was predicted by the cNLS mapper software. ROA2 binds to Trn via its well characterized proline-tyrosine NLS (36), but it also binds to Imp-α indirectly through its interaction with HNRPU or HNRPK, suggesting that the free and complex forms are imported through different pathways. Currently, the physiological significance of these complicated carrier-cargo interaction networks remains unclear, but cross-talk between transport pathways could be integrated globally and encompass the entire nucleocytoplasmic transport system. Similar experiments utilizing the SILAC-Tp method will reveal unknown features of the transport system in the appropriate physiological contexts.

Some proteins (proteins 4, 26, 30, and 34) that were highly ranked by their αβ/C values did not bind to Imp-β under any of the conditions examined in our bead halo assays, but these proteins may have been imported in the SILAC-Tp assay through interactions with cargo proteins that were not identified by the LC-MS/MS analysis. In fact, protein 2 (SRRT/Ars2) has been shown to bind the cap-binding complex that is imported by Imp-α/β (41–43), but this complex was not identified in our LC-MS/MS analysis. Conversely, one protein (protein 78) that was ranked low by its αβ/C value bound to Imp-α, and a few proteins (proteins 62, 81, and 83) that were reported to be Imp-α/β cargoes were ranked low by their αβ/C values (Table 1). Overall, the SILAC-Tp method sorted Imp-α/β cargoes less efficiently than Trn cargoes. This discrepancy in efficiency may be because Imp-β is the predominant carrier and imports many cargo proteins, reducing the share of import activity for each of its cargo. Because the Imp-α/β-dependent import pathway is the most prevalent in cells as estimated in yeast (16), all other carriers, which are expected to transport fewer cargoes than Imp-β, may not have this problem. It is widely accepted that Imp-β and some other Imp-β family carriers are abundant proteins in cells (44), but Imp-β is no more abundant than the other members of the family in our observation (data not shown). In addition, cellular contents of Imp-αs are roughly comparable with that of Imp-β, although expression levels of each of the family members vary in different cell types and tissues (7, 45–47). Therefore, it is not only the cellular concentration of carriers that determines import activity of each pathway. In fact, the transport efficiency and the number of identified cargoes do not increase by a simple addition of more Imp-α/Imp-β to the in vitro transport reaction (i.e. according to titration experiments in our in vitro transport system, 1 μm Imp-β and 2 μm Imp-α were added, but increasing their concentration does not improve the transport efficiency). Cellular abundance of Imp-α/β cargoes could be another important issue. Many Imp-β (and Imp-α/β) cargoes, such as transcription factors, for example, are low abundance proteins in cells and also in the nuclear extract that we used. Use of a fractionated nuclear extract in which the minor proteins are enriched may improve the cargo identification.

The Imp-β or Trn cargoes identified in this and our previous work (12) were fewer than expected. These low yields are referable to the numbers of proteins that were validly quantified by LC-MS/MS (307 and 298 for Imp-β and Trn, respectively), and the sensitivity of quantification depends largely on the performance of the instruments. Because our samples prepared for the SILAC-Tp method contained more nuclear proteins than actually identified by LC-MS/MS as shown previously (12), use of the advanced equipment must improve the cargo identification. Recently, other types of SILAC-based methods for cargo identification have utilized siRNA for Imp-α (48) or a specific inhibitor of exportin-1 (49). These methods and the method we have described have their respective merits, and they will identify different sets of cargoes that should complement results from other studies. Thus, parallel usage of the different SILAC-based methods must be practical to effectively identify carrier-specific cargoes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Maiko Furuta for thoughtful advice and reagents, and we also thank Yuriko Morinaka, Ai Watanabe, Yuumi Oda, and Seishi Iguchi for technical assistance.

This work was supported by the RIKEN Special Project Funding for Basic Science in Cellular System Project Research and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) through the “Funding Program for Next Generation World-Leading Researchers (NEXT Program),” which was initiated by the Council for Science and Technology Policy (CSTP) (to N. I.).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S3 and Figs. S1–S5.

- Imp-β

- importin-β

- cNLS

- classical nuclear localization signal

- Imp-α

- importin-α

- Imp-α/β

- importin-β with importin-α

- Imp-αs

- importin-α family carriers

- Imp-βs

- importin-β family carriers

- L/H

- light/heavy

- NLS

- nuclear localization signal

- SILAC

- stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture

- SILAC-Tp

- SILAC-based in vitro transport

- Trn

- transportin

- RNP

- ribonucleoprotein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Terry L. J., Shows E. B., Wente S. R. (2007) Crossing the nuclear envelope. Hierarchical regulation of nucleocytoplasmic transport. Science 318, 1412–1416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Poon I. K., Jans D. A. (2005) Regulation of nuclear transport. Central role in development and transformation? Traffic 6, 173–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pemberton L. F., Paschal B. M. (2005) Mechanisms of receptor-mediated nuclear import and nuclear export. Traffic 6, 187–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kose S., Furuta M., Imamoto N. (2012) Hikeshi, a nuclear import carrier for Hsp70s, protects cells from heat shock-induced nuclear damage. Cell 149, 578–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mingot J. M., Kostka S., Kraft R., Hartmann E., Görlich D. (2001) Importin 13. A novel mediator of nuclear import and export. EMBO J. 20, 3685–3694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gontan C., Güttler T., Engelen E., Demmers J., Fornerod M., Grosveld F. G., Tibboel D., Görlich D., Poot R. A., Rottier R. J. (2009) Exportin 4 mediates a novel nuclear import pathway for Sox family transcription factors. J. Cell Biol. 185, 27–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Major A. T., Whiley P. A., Loveland K. L. (2011) Expression of nucleocytoplasmic transport machinery. Clues to regulation of spermatogenic development. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 1668–1688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sato M., Mizoro Y., Atobe Y., Fujimoto Y., Yamaguchi Y., Fustin J. M., Doi M., Okamura H. (2011) Transportin 1 in the mouse brain. Appearance in regions of neurogenesis, cerebrospinal fluid production/sensing, and circadian clock. J. Comp. Neurol. 519, 1770–1780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Huang J. G., Yang M., Liu P., Yang G. D., Wu C. A., Zheng C. C. (2010) Genome-wide profiling of developmental, hormonal or environmental responsiveness of the nucleocytoplasmic transport receptors in Arabidopsis. Gene 451, 38–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chook Y. M., Süel K. E. (2011) Nuclear import by karyopherin-βs. Recognition and inhibition. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 1593–1606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ong S. E., Blagoev B., Kratchmarova I., Kristensen D. B., Steen H., Pandey A., Mann M. (2002) Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol. Cell Proteomics 1, 376–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kimura M., Kose S., Okumura N., Imai K., Furuta M., Sakiyama N., Tomii K., Horton P., Takao T., Imamoto N. (2013) Identification of cargo proteins specific for the nucleocytoplasmic transport carrier transportin by combination of an in vitro transport system and stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC)-based quantitative proteomics. Mol. Cell Proteomics 12, 145–157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Patel S. S., Rexach M. F. (2008) Discovering novel interactions at the nuclear pore complex using bead halo. A rapid method for detecting molecular interactions of high and low affinity at equilibrium. Mol. Cell Proteomics 7, 121–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kelley J. B., Talley A. M., Spencer A., Gioeli D., Paschal B. M. (2010) Karyopherin α7 (KPNA7), a divergent member of the importin α family of nuclear import receptors. BMC Cell Biol. 11, 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goldfarb D. S., Corbett A. H., Mason D. A., Harreman M. T., Adam S. A. (2004) Importin α. A multipurpose nuclear-transport receptor. Trends Cell Biol. 14, 505–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lange A., Mills R. E., Lange C. J., Stewart M., Devine S. E., Corbett A. H. (2007) Classical nuclear localization signals. Definition, function, and interaction with importin α. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5101–5105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marfori M., Mynott A., Ellis J. J., Mehdi A. M., Saunders N. F., Curmi P. M., Forwood J. K., Bodén M., Kobe B. (2011) Molecular basis for specificity of nuclear import and prediction of nuclear localization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 1562–1577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kosugi S., Hasebe M., Matsumura N., Takashima H., Miyamoto-Sato E., Tomita M., Yanagawa H. (2009) Six classes of nuclear localization signals specific to different binding grooves of importin α. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 478–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang S. N., Takeda A. A., Fontes M. R., Harris J. M., Jans D. A., Kobe B. (2010) Probing the specificity of binding to the major nuclear localization sequence-binding site of importin-α using oriented peptide library screening. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 19935–19946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blazek E., Meisterernst M. (2006) A functional proteomics approach for the detection of nuclear proteins based on derepressed importin α. Proteomics 6, 2070–2078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ly-Huynh J. D., Lieu K. G., Major A. T., Whiley P. A., Holt J. E., Loveland K. L., Jans D. A. (2011) Importin α2-interacting proteins with nuclear roles during mammalian spermatogenesis. Biol. Reprod. 85, 1191–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fukumoto M., Sekimoto T., Yoneda Y. (2011) Proteomic analysis of importin α-interacting proteins in adult mouse brain. Cell Struct. Funct. 36, 57–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park K. E., Inerowicz H. D., Wang X., Li Y., Koser S., Cabot R. A. (2012) Identification of karyopherin α1 and α7 interacting proteins in porcine tissue. PLoS One 7, e38990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miyamoto Y., Baker M. A., Whiley P. A., Arjomand A., Ludeman J., Wong C., Jans D. A., Loveland K. L. (2013) Towards delineation of a developmental α-importome in the mammalian male germline. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1833, 731–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Görlich D., Henklein P., Laskey R. A., Hartmann E. (1996) A 41-amino acid motif in importin-α confers binding to importin-β and hence transit into the nucleus. EMBO J. 15, 1810–1817 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Weis K., Ryder U., Lamond A. I. (1996) The conserved amino-terminal domain of hSRP1α is essential for nuclear protein import. EMBO J. 15, 1818–1825 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Moroianu J., Blobel G., Radu A. (1996) The binding site of karyopherin α for karyopherin β overlaps with a nuclear localization sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 6572–6576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bischoff F. R., Ponstingl H. (1995) Catalysis of guanine nucleotide exchange of Ran by RCC1 and stimulation of hydrolysis of Ran-bound GTP by Ran-GAP1. Methods Enzymol. 257, 135–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kobe B. (1999) Autoinhibition by an internal nuclear localization signal revealed by the crystal structure of mammalian importin α. Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 388–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Qu D., Zhang Y., Ma J., Guo K., Li R., Yin Y., Cao X., Park D. S. (2007) The nuclear localization of SET mediated by impα3/impβ attenuates its cytosolic toxicity in neurons. J. Neurochem. 103, 408–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ishimi Y. (1997) A DNA helicase activity is associated with an MCM4, -6, and -7 protein complex. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 24508–24513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jurica M. S., Licklider L. J., Gygi S. R., Grigorieff N., Moore M. J. (2002) Purification and characterization of native spliceosomes suitable for three-dimensional structural analysis. RNA 8, 426–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jønson L., Vikesaa J., Krogh A., Nielsen L. K., Hansen Tv., Borup R., Johnsen A. H., Christiansen J., Nielsen F. C. (2007) Molecular composition of IMP1 ribonucleoprotein granules. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 798–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cary R. B., Peterson S. R., Wang J., Bear D. G., Bradbury E. M., Chen D. J. (1997) DNA looping by Ku and the DNA-dependent protein kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 4267–4272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kosugi S., Hasebe M., Tomita M., Yanagawa H. (2009) Systematic identification of cell cycle-dependent yeast nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins by prediction of composite motifs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 10171–10176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Siomi H., Dreyfuss G. (1995) A nuclear localization domain in the hnRNP A1 protein. J. Cell Biol. 129, 551–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee B. J., Cansizoglu A. E., Süel K. E., Louis T. H., Zhang Z., Chook Y. M. (2006) Rules for nuclear localization sequence recognition by karyopherin β2. Cell 126, 543–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Süel K. E., Gu H., Chook Y. M. (2008) Modular organization and combinatorial energetics of proline-tyrosine nuclear localization signals. PLoS Biol. 6, e137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jäkel S., Görlich D. (1998) Importin β, transportin, RanBP5 and RanBP7 mediate nuclear import of ribosomal proteins in mammalian cells. EMBO J. 17, 4491–4502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hieda M., Tachibana T., Fukumoto M., Yoneda Y. (2001) Nuclear import of the U1A splicesome protein is mediated by importin α/β and Ran in living mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 16824–16832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Görlich D., Kraft R., Kostka S., Vogel F., Hartmann E., Laskey R. A., Mattaj I. W., Izaurralde E. (1996) Importin provides a link between nuclear protein import and U snRNA export. Cell 87, 21–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gruber J. J., Zatechka D. S., Sabin L. R., Yong J., Lum J. J., Kong M., Zong W. X., Zhang Z., Lau C. K., Rawlings J., Cherry S., Ihle J. N., Dreyfuss G., Thompson C. B. (2009) Ars2 links the nuclear cap-binding complex to RNA interference and cell proliferation. Cell 138, 328–339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dias S. M., Wilson K. F., Rojas K. S., Ambrosio A. L., Cerione R. A. (2009) The molecular basis for the regulation of the cap-binding complex by the importins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 930–937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Jäkel S., Mingot J. M., Schwarzmaier P., Hartmann E., Görlich D. (2002) Importins fulfil a dual function as nuclear import receptors and cytoplasmic chaperones for exposed basic domains. EMBO J. 21, 377–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nachury M. V., Ryder U. W., Lamond A. I., Weis K. (1998) Cloning and characterization of hSRP1γ, a tissue-specific nuclear transport factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 582–587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kamei Y., Yuba S., Nakayama T., Yoneda Y. (1999) Three distinct classes of the α-subunit of the nuclear pore-targeting complex (importin-α) are differentially expressed in adult mouse tissues. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 47, 363–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Köhler M., Fiebeler A., Hartwig M., Thiel S., Prehn S., Kettritz R., Luft F. C., Hartmann E. (2002) Differential expression of classical nuclear transport factors during cellular proliferation and differentiation. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 12, 335–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang C. I., Chien K. Y., Wang C. L., Liu H. P., Cheng C. C., Chang Y. S., Yu J. S., Yu C. J. (2012) Quantitative proteomics reveals regulation of karyopherin subunit α-2 (KPNA2) and its potential novel cargo proteins in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, 1105–1122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Thakar K., Karaca S., Port S. A., Urlaub H., Kehlenbach R. H. (2013) Identification of CRM1-dependent nuclear export cargos using quantitative mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 12, 664–678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jackson E. B., Theriot C. A., Chattopadhyay R., Mitra S., Izumi T. (2005) Analysis of nuclear transport signals in the human apurinic/apyrimidinic endonuclease (APE1/Ref1). Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 3303–3312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Koike M., Ikuta T., Miyasaka T., Shiomi T. (1999) Ku80 can translocate to the nucleus independent of the translocation of Ku70 using its own nuclear localization signal. Oncogene 18, 7495–7505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Köhler M., Speck C., Christiansen M., Bischoff F. R., Prehn S., Haller H., Görlich D., Hartmann E. (1999) Evidence for distinct substrate specificities of importin α family members in nuclear protein import. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 7782–7791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Song N., Ding Y., Zhuo W., He T., Fu Z., Chen Y., Song X., Fu Y., Luo Y. (2012) The nuclear translocation of endostatin is mediated by its receptor nucleolin in endothelial cells. Angiogenesis 15, 697–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kim B. J., Lee H. (2006) Importin-β mediates Cdc7 nuclear import by binding to the kinase insert II domain, which can be antagonized by importin-α. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 12041–12049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Friedrich B., Quensel C., Sommer T., Hartmann E., Köhler M. (2006) Nuclear localization signal and protein context both mediate importin α specificity of nuclear import substrates. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 8697–8709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Koike M., Ikuta T., Miyasaka T., Shiomi T. (1999) The nuclear localization signal of the human Ku70 is a variant bipartite type recognized by the two components of nuclear pore-targeting complex. Exp. Cell Res. 250, 401–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Chou C. W., Tai L. R., Kirby R., Lee I. F., Lin A. (2010) Importin β3 mediates the nuclear import of human ribosomal protein L7 through its interaction with the multifaceted basic clusters of L7. FEBS Lett. 584, 4151–4156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Matsubae M., Kurihara T., Tachibana T., Imamoto N., Yoneda Y. (2000) Characterization of the nuclear transport of a novel leucine-rich acidic nuclear protein-like protein. FEBS Lett. 468, 171–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hodge D. R., Cho E., Copeland T. D., Guszczynski T., Yang E., Seth A. K., Farrar W. L. (2007) IL-6 enhances the nuclear translocation of DNA cytosine-5-methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) via phosphorylation of the nuclear localization sequence by the AKT kinase. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 4, 387–398 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Antoine M., Reimers K., Wirz W., Gressner A. M., Müller R., Kiefer P. (2005) Identification of an unconventional nuclear localization signal in human ribosomal protein S2. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 335, 146–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]