Abstract

The objective of this study was to qualitatively describe the impact of a Rapid Response Team (RRT) at a 944-bed, university-affiliated hospital. We analyzed 49 open-ended interviews with administrators, primary team attending physicians, trainees, RRT attending hospitalists, staff nurses, nurses, respiratory technicians. Themes elicited were categorized into the domains of (1) morale and teamwork, (2) education, (3) workload, (4) patient-care, and (5) hospital-administration. Positive implications beyond improved care for acutely ill patients were: increased morale and empowerment among nurses, real-time redistribution of workload for nurses (reducing neglect of non-acutely ill patients during emergencies), and immediate access to expert help. Negative implications were: increased tensions between nurses and physician-teams, a burden on hospitalist RRT-members, and reduced autonomy for trainees. The RRT provides advantages that extend well beyond a reduction in rates of transfers to intensive care units or codes but are balanced by certain disadvantages. Potential impact from these multiple sources should be evaluated to understand the utility of any RRT program.

Keywords: Hospital rapid response team, qualitative research, workload, quality improvement, program evaluation

Introduction

Rapid response teams (RRTs), also known as a medical emergency teams or medical response teams, were developed to promote rapid assessment and treatment of patients whose clinical condition was deteriorating but who were not yet in shock or cardiac arrest.[1] In 2004, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement included RRTs in its influential 100,000 Lives Campaign, and by the next year over 1,400 American hospitals had implemented programs.[2] In 2008, RRTs became part of hospital accreditation by The Joint Commission.[3]

By making it easy to escalate care earlier, RRTs are thought to reduce mortality and codes occurring outside of intensive care units (ICUs).[4-8] Despite these potential successes, the impact of RRTs has been questioned: some authors have casted doubt on the prudence of implementing RRTs without stronger evidence of improved outcomes.[9-13] Existing studies have focused their measures of success on mortality and code rates [4-8]; however, RRTs may have substantial impact beyond these outcomes. For example, Donaldson et al described reasons staff nurses are in favor of RRTs -- many of which may be only tangentially related to reducing mortality outside of intensive care (physical assistance, one-call mobilization, competency of a critical care nurse, and expedited transfer of patients).[14]

Whether RRTs can decrease mortality and codes outside of the ICU represents only one component of their value. To create a comprehensive view of the impact and value of an RRT on a hospital and its staff, the objective of this study was to qualitatively describe the experiences of and attitudes held by nurses, physicians, administrators, and staff regarding RRTs.

Methods

Study Design

To broadly evaluate the RRT, we chose a qualitative methodological approach. Qualitative methodology provides a framework for developing exploratory studies to describe comprehension and behaviors that are based on complex beliefs that can be difficult to measure in a standardized quantitative manner.[15] We conducted qualitative, open-ended interviews with nurses, physicians, RRT members, housestaff (both interns and resident physicians), and administrators during November 2008 to January 2009.

Setting

Yale-New Haven Hospital is an academic hospital in New Haven, Connecticut. During the period of this study, the hospital had 944 beds and had 45,000 adult discharges per year covered by a medical staff of 1600 with an additional 500 affiliated physicians, 700 residents, 250 fellows, 1200 nurses for adult medical or surgical areas, and 21 senior administrators (7 of which had oversight for clinical areas).

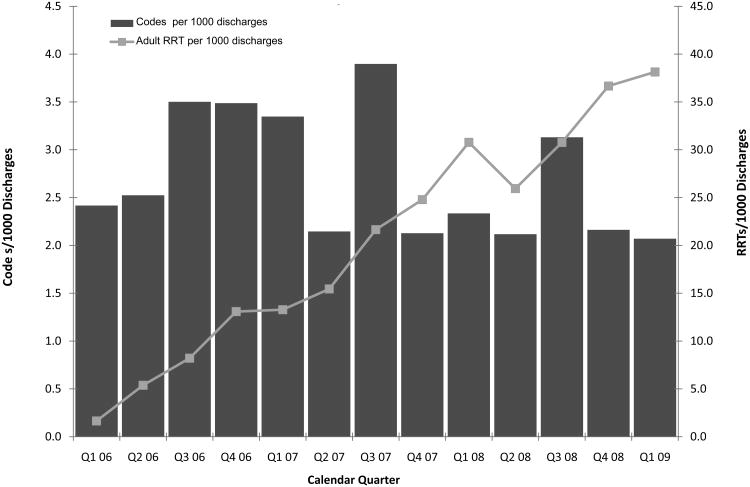

The adult RRT was instituted in December 2005. During the period of this study, the team covered 43 patient-care-units and received an average of 36.7 calls per 1,000 discharges (Figure 1). The RRT was composed of a hospitalist physician, a critical care “SWAT” nurse, and a respiratory therapist. A “SWAT” nurse is a resource nurse or “floater” with >2 years critical care training. Our RRT could also be classified as a medical response team or medical emergency team because it included a physician. Our clinical administrative policy addressed the purpose, procedure, trigger criteria, and responsibilities for the RRT. If a patient met one of the trigger criteria, the patient's nurse was expected to call the RRT simultaneously with the primary team so that decisions can be made jointly. As of December 2008, median response time was 2 minutes, median time at the bedside was 56 minutes, 40% of calls occurred during the day, 35% during the evening, and 25% at night.

Figure 1. Adult Rapid Response Team (RRT) Calls and Codes per 1,000 Discharges, Yale-New Haven Hospital, Q1 2006 – Q1 2009.

Sampling

As is standard in qualitative research, we used purposeful sampling to ensure that we included a diverse group of participants; we interviewed participants until no new concepts were identified by additional interviews (theoretical saturation) [15, 16].

Participants were selected from administrators, registered nurses, senior attending physicians, housestaff, and members of the adult rapid response team. Registered nurses were interviewed from 4 different medical units, 2 with a high rate of RRT activations and 2 with a low rate of RRT activations. We purposefully sought and interviewed staff with varied views based on the working knowledge of the Medical Director who was able to characterize persons in favor of or opposed to the RRT.

Data Collection

In total, we interviewed 49 participants: 18 registered nurses, 8 administrators, 6 primary team senior attending physicians, 6 house staff members, 4 RRT attending physicians, 4 RRT critical care (SWAT) nurses, and 3 RRT respiratory technicians. After obtaining consent, one investigator (CPB) conducted and recorded private interviews with each participant. Interviews (except for those with hospital administrators) began with a request to describe a recent or memorable experience when the participant had been involved with an RRT. Standard open-ended questions and probes were used to elicit a broad discussion about the RRT program.

Analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim by an independent transcriptionist. Using the common coding techniques for qualitative data and the constant comparative method of qualitative data analysis, we elicited from the interviews a list of major thematic categories and subcategories [15]. After a comprehensive coding structure had been established, researchers met in pairs (each researcher met with every other) to formally code each interview line-by-line. As new themes were elicited, the group reconvened, reviewed the themes, and made iterative changes to the coding structure; disagreements in coding were resolved through negotiated consensus. After all interviews had been coded and the taxonomy was complete, all authors met again to refine and to finalize the coding structure. A qualitative software coding program (Atlas-TI, GmbH, Germany) was used to retrieve and organize quotations.

Human Subjects

The project was approved by the Yale School of Medicine Human Investigation Committee. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Themes elicited from interviews were categorized into the broad domains of (1) morale and teamwork, (2) education, (3) workload, (4) patient-care, and (5) hospital administration (Table 1). Within each domain, themes emerged in the subcategories of positive impact and negative implications. In addition, interviewees identified suggestions for improving the program (Table 2).

Table 1. Qualitative domains, categories and themes derived from interviews.

| Domain | Category& Theme | |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Impact | Negative Implications | |

| Morale/teamwork | Support and empowerment for nurses | Conflict between primary team and nurse/between primary team and RRT |

| Education | Education for physicians and for nurses | Negative impact for education of housestaff |

| Workload | Redistribution of nurses' workload during emergent care | Burden of work for RRT members |

| Positive impact for physician workload | ||

| Patient care | Formalized process for escalation of care for patients | Errors and delays due to lack of continuity |

| Hospital Administration | Patient-flow, throughput through hospital | |

| Retention of nurses | ||

Table 2. Suggestions for Improvement of the RRT Program by Interviewees.

| Domain | Theme |

|---|---|

| Suggestions for Improvement from Interviewees | Expand resources & scope (e.g outpatient) |

| Improved data feedback to generate buy-in | |

Decrease conflict

| |

| Include front-line staff in suggesting improvements | |

| Include housestaff on team for their education | |

| More clarity on DNR/DNI status |

Morale and Teamwork

Positive Impact: Improved Morale for Nurses

A major theme that emerged for nurses was a sense of security and of empowerment generated by knowing skilled backup was available immediately through a single phone call. In the words of one nurse:

It's very comforting to have someone help us to assess the patient… to make the decision that the person is too sick to remain on the floor…and to support us.

This theme was echoed by both physicians and administrators. One hospitalist said, “[The nurses] actually have something they can do about it versus just kind of watching the patient flounder.”

The availability of the RRT empowered nurses who were able to obtain additional help without having to request permission. As one nurse explained, “I don't usually hesitate to call. I notify the team of any changes, and if I feel like I need additional nursing support or if I need respiratory support right that minute, I will call an RRT.” In the words of one senior leader:

When a nurse says, “I know my patient and something doesn't seem right,” and picks up a phone to call a rapid response - that is part of creating the work environment where the voice of nurse is heard and respected.

Negative Implications: Conflict between Primary Team and Nurse or RRT

While the RRT improved morale for nurses, it was also perceived to increase conflict between nurses and physicians. Some primary team physicians felt that nurses called the RRT inappropriately instead of calling the physicians who were the primary team and thus better suited to caring for the patient. This reduced the primary team members' ability to perform their role in caring for patients.

I know that it's made more tension between nursing and housestaff… [The nurses] always…apologized when they were calling one [RRT] because …they knew it upset us…it gave us so much more work and that we sort of philosophically disagreed with why they were calling them many times. (PGY-3 Resident)

Consequently, some primary teams discouraged the nurse from calling an RRT regardless of the severity of the situation:

The attending pulled me aside during the RRT to basically reprimand me for going above his head…even though I needed that extra support and I knew I should have called the RRT much earlier in the day… That's a barrier in calling an RRT, which could affect the patient's outcome. (Nurse)

In contrast, nurses often viewed the RRT as a solution to pre-existing problems with nurse-physician teamwork. Nurses reported feeling as though they sometimes tried going through the correct channels with the housestaff without a satisfactory outcome.

The patient was decompensating and during rounds I tried to express my concerns and my observations to the medical team …The patient continued to decompensate through the morning and I called the team every 5 minutes basically. With really no support and response… The patient was having trouble breathing; the patient's abdomen was distended and firm…So by lunch time, I had spent most of my morning with this patient…I ended up calling an RRT, which probably should have been called three hours earlier. (Nurse)

Several nurses felt this tension derived from a perception by physicians that a call to the RRT implied a failure on the part of the physician. In contrast, nurses were very practical about using it as a way to get another set of experienced eyes and hands.

I don't think it's that they don't appreciate the help from the hospitalist attending who shows up, because the hospitalist attending never really dictates care…But I think physicians look at it as they're not doing the best job that they can be doing. Instead of looking at it as help. (Nurse)

Despite these issues, nurses reported that the tensions improved over the years since the initial implementation of the program.

Sometimes they…have a bit of an attitude thing, “Oh I can handle this. This is my patient. I know this patient. I didn't want a rapid response to be called.” You know, we get a fair amount of that, but not as much as we did in the beginning. In the beginning…nurses were getting yelled at by the primary team like, “How dare you call a rapid response on my patient?” …They seem to be more receptive now. (SWAT Nurse)

Education

Positive Impact: Education

For both nurses and physicians, the RRT intervention could be used as a learning tool; and in particular, was seen as a good way to support and nurture junior nurses.

From an educational standpoint, you have seasoned people who can teach the younger physicians or residents how you approach someone like this. (Attending)

As a SWAT nurse…you have a little bit more time where once the rapid response is finished up, you are then able to go back to the nurse who initially called the rapid response and say, “You know, hey either that was a great job and you were really were dead-on with your call.” Or, “These are some things that maybe [you] could have done before the rapid response was called to help better the situation.”…(SWAT Nurse)

The hospitalists who rotated being on call for the RRT also appreciated the ongoing exposure to acutely decompensating patients as a way to make sure that their skills remained up-to-date. In the words of one hospitalist, “So just to kind of keep up some of the skills of, you know, when there's … a more difficult situation.”

Negative Implications: Detriment to Education of Housestaff

Because the RRT served to escalate care rapidly to the most experienced clinicians, physicians felt that physician-learners were not being adequately exposed to the decision-making process that is a requisite part of learning to be an independent physician. Teaching about thought-processes was being lost in the effort to expedite care for patients and the traditional teaching approach to care was upended.

The intern is the front line in the hospital … the one who goes, assesses the situation, tries to come up with a treatment plan and implements it under the auspices of a senior resident and an attending.… Very rarely on the floors is a situation so dire that an intern can't have 15 minutes to try to figure out a treatment plan…unfortunately what's happening with the RRTs is …RRTs are being called, a team is rushing in and barking orders, and the intern then is left in the dust. (PGY-3 Resident)

Workload

Positive Impact: Redistribution of Nurses' Workload

An important effect of the RRT was that it facilitated a redistribution of the workload for nurses. When a patient was very sick, it could take substantial effort by multiple nurses to attend to that patient. Consequently, the focus on the sick patient may divert resources from the other patients on the unit:

I had pushed a couple of medications and still could not get the heart rate down…once you start doing a few medications and doing the follow-up, you're watching the clock (and it had been about an hour, an hour and a half) …I'm starting to just focus on that 1 patient…we're hurting our other 4 patients… At the same, I had called in another nurse …now her 4 patients are not seeing the care that they should…So you're looking at maybe 8 patients now.(Nurse)

Repeatedly, interviewees described how the RRT provided nurses a way to realign the workload and to ensure that other patients were not being neglected.

Positive Impact: Balance of Physician Workload

Just as for nurses, acutely ill patients required a great deal of attention from physicians, potentially diverting their attention from other patients. This was a particular problem on nights and weekends when physicians already carried a larger workload. Physicians also noted the value of the RRT in providing expert assistance from both physicians and nurses in these situations.

I feel like the rapid responses that I've been involved in are in the middle of the night, and I'm tired and everyone's really busy, and we've got people coming up from the ED, and it's just…we need to get these people safe so we can go attend to our other people. (Intern)

I think that sometimes you legitimately need more help. When I'm here on the weekend as the only resident …I'm responsible for 40 very sick patients alone. (PGY-3 Resident)

Negative Implications: Burden to RRT members

The RRT is staffed by hospitalists who are also carrying their own patient load during their shift. For this reason, many hospitalists described a negative impact of RRT calls on their workload.

[The RRT] is not our only clinical responsibility for the day…it implies that at any time in your day, you drop that other patient; that other family; that other conversation …and you run to these situations…it's extremely disruptive… You see how huge this place is… it takes 10 minutes with the way the elevators work in this hospital to get to 5-2 [another patient unit] … So I think it's just a huge, huge stressor in terms of having physicians do it who are clinically responsible for others. (Hospitalist)

Patient-care

Positive Impact: Escalation of Care for Patients

The majority of participants described a positive impact of the RRT for patients in facilitating rapid escalation of care. Escalation of care took multiple forms: patients who were becoming increasingly acutely ill received necessary care in an expedited fashion, transfer to the ICU was smoother, and patient-safety could be ensured. In particular, participants articulated that the RRT provided a formalized process for escalating care that was more effective than earlier models. In the past, SWAT nurses had been available for help, and consults from the ICU were also available. These processes, however, could be erratic or dependent on personal relations or complicated politics. Formalizing the mechanism for escalating care to an RRT with appropriate expertise and devising a means for having them arrive in timely fashion meant that escalation of care was more effective and efficient. In the words of one administrator:

What the rapid response teams have done is sort of implement a more rational and planned approach to that previous sort of ‘Helter-skelter’ approach… “Well, I gotta find the respiratory therapist.” One call really precipitates team action… We were actually able to implement the team, teams without resource additions, because this work was [already] getting done in a slightly less-organized fashion. (Administrator)

Providers repeatedly described examples when a patient had begun deteriorating and quickly received more efficient and effective care and/or transfer than would have been possible in the days before the RRT program.

It's gotten them [patients] to safer levels of care within the hospital. For example, that patient…who needed to go back to the OR - the physicians caring for her were not willing to see that she was in distress… getting that outside opinion really helped them reevaluate the situation and move her to where she really needed to be. (SWAT nurse)

Negative Implications: Errors and Delays Due to Lack of Continuity

A few primary attendings felt that their plans for patients were disrupted by the RRT and caused disjointed care for the patients.

The RRT teams would have made mistakes had we not been there because they didn't know the patient… they came in, diligent though they were, listened to the patient's lungs… and wanted to give the patient some diuretic to get the fluid out. We knew that this patient had a chronic lung process, for the rales were always there. The patient had renal failure and it would have been a bad idea to give the diuretic. And so my concern is that although there are times when RRT certainly makes sense, I think you're much better off dealing with someone who knows the patient. (Primary Attending)

In addition, it could be very time-consuming for RRT members to get adequately briefed on the pertinent medical history of the patient. As one intern said, “They're not familiar with the patient. It takes them too long to look in the chart and figure out what's going on.”

Hospital Administration

In addition to the above themes, there were two ideas that emerged from hospital administrators that were specifically about creating a positive impact for the hospital as a whole.

Positive Impact: Patient-Flow

Administrators reported that the RRT served as a centralized mechanism to triage which patients should go to the ICU. In this manner, the RRT helped to manage the flow to the ICU beds, as well as averting some transfers altogether. As one administrator said:

If we can stabilize patients who become unstable before they require ICU transfer, then we leave that bed open for a patient from another place and are better able to handle incoming patients and patients from our ORs. (Administrator)

Positive Impact: Nursing Retention

Administrators described that the RRT program played an important role in retention of nurses:

We do have data that over the last couple years nurse retention has improved and nurse turnover has declined. We also have …interviews with our staff nurses about the rapid response teams. That they really feel like somebody has their back … they have somebody to call. (Administrator)

Suggestions for Improvement

A number of suggestions emerged from the interviews about how to improve the RRT as it was implemented. These suggestions are listed in Table 2 and many correspond directly to the themes about negative impact described above.

Discussion

In this qualitative study, we found that the positive impact of the existing implementation of the RRT for adult patients at our hospital extended well beyond a reduction in mortality or rates of codes. The RRT expedited effective care for acutely ill patients, ensured other patients were not neglected, improved morale and perhaps retention of nurses, facilitated hospital throughput and provided learning opportunities for nurses and physicians alike. At the same time, this study of the RRT showed some disadvantages: tensions may develop between floor nurses and primary teams, the RRT was perceived to have disruptive effects on trainee autonomy and education, and RRT members may have an excessive workload. Based on this information, we were able to target improvements to our RRT program by emphasizing decreasing tensions between teams, reviewing the distribution of workload for team members and others, and developing an integrated approach to education for both nurses and physicians to engage them in the RRT.

Some of the disadvantages to the RRT program elicited by this study may be specific to the environment of a teaching hospital. In particular, negative comments focused on lack of continuity of care and changes in traditional teaching approaches. This tension between clinical teaching and patient safety is not new – long-standing controversies in this regard are exemplified by the debates over resident duty-hours.[17, 18] Patient safety, however, does not need to preclude learning; and strategies to mitigate these disadvantages were suggested by interviewees, such as placing trainees on the RRT and using the event of an RRT as a teaching tool. To ensure that the education of physician- or nurse-trainees does not occur at the expense of patient safety and timely, quality care, we have used the information from this study to instigate expanded efforts in simulation with scenarios focused on clinical deterioration. Moreover, the experience of interviewees indicates that over time providers get used to the RRT and that many of the problems and conflicts abate.

The results of this study begin to address the question of how we define success for RRTs – should RRTs be evaluated on outcomes beyond a reduction in codes or mortality? Studies touting the success [4-8, 19-24] or failure [9, 10, 12, 25-27] of RRTs have typically relied on these narrowly-defined, quantitative determinants of success. The results of our study, however, show that relying entirely on these outcomes neglects numerous consequences – many quite valuable – of implementing the RRT. The RRT has effectively organized and streamlined work for those who care for the clinically deteriorating patient. This has led to ancillary benefits to staff morale, allowed increased attention to non-acutely -ill patients, improved hospital throughput, and enhanced education. Our thoughtful assessment of negative aspects has also engaged staff and facilitated program improvement. Together, looking at all of these outcomes, positive and negative, we believe the RRT promotes the “safety culture” at our hospital. Some of these outcomes have been partially assessed in earlier studies [14, 28], but comprehensive evaluation of all participants, such as was done in this study, are rare. Many of the positive and negative implications that we delineated qualitatively can and should be assessed quantitatively in future evaluations of any RRT program in order to fully understand its value.

These qualitatively-derived endpoints may also lend insight into the numerous reports of RRT failures.[9, 10, 12, 25-27] As several authors have noted, the nature of the implementation of the RRT program has a profound effect on program outcomes.[11, 29] RRT programs vary from “robust” to “challenged” [14], depending on the extent of cultural change present in the hospitals. Our study suggests several metrics by which implementation and culture can be assessed, including belief in effectiveness of RRT, relationship between nurses and physicians, response of physicians to nurse calling the RRT, willingness of nurses to call the RRT, morale, perceptions of workload distribution and others. Similar factors have been assessed in some studies of “challenged” implementations.[28, 30, 31]

The limitations of the study were related to generalizability and are typical to qualitative and quality improvement research. We included a purposeful sample from one hospital and one implementation of an adult RRT program. However, the generalizability of qualitative work is not intended to derive from a statistically representative sample; instead, qualitative work should describe in-depth a full range of attitudes to create a theoretical understanding of an issue. To maximize the validity of our findings, we used the methodological techniques of purposeful sampling, grounded theory, and coding by multiple researchers who came to agreement on the coding structure. Future work could evaluate the prevalence of the different themes across a wider spectrum of hospitals.

Future evaluations of the impact of any RRT program should include assessment of outcomes beyond those of codes and mortality. Efforts must include evaluation of the impact on morale of nurses, speed of escalation of care for acutely-ill patients, tensions between teams, distribution of workload, education for both nurses and physicians, and appropriate care for patients not involved in the RRT.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all of the participants for sharing their thoughts and time. We would also like to thank Marie Devlin, Elizabeth Fletcher, Lois Benis, Ginny Defilippo, Victor Morris, Michael Bennick, and Ada Fenick for their assistance in this work. This publication was made possible by CTSA Grant Number UL1 RR024139 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. This project was also supported by The National Library of Medicine (5K22LM9142) and by K08 AG038336 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA) and by the American Federation for Aging Research (AFAR) through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR, NIA, AFAR or NIH.

Funding: During the period of the study, Dr. Benin was supported by the National Library of Medicine (grant number 5K22LM9142) and Dr. Horwitz was supported by Grant Number UL1 RR024139 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. Dr. Horwitz is currently supported by the National Institute on Aging and the American Federation for Aging Research (K08 AG038336).

Appendix 1.

Interview Guides.

| Interviewee Category | Broad Question | Probes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Team & Nursing Staff |

|

|

| Administrators |

|

|

| RRT Members |

|

|

References

- 1.Lee A, Bishop G, Hillman KM, Daffurn K. The medical emergency team. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1995;23:183–6. doi: 10.1177/0310057X9502300210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robeznieks A. Quick assistance. Surge of popularity puts rapid-response teams in 1,400 U.S. hospitals. Mod Healthc. 2005;35:33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Joint Commission. [Accessed: 10/4/2008];National Patient Safety Goals. 2008 http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals/08_cah_npsgs.htm.

- 4.Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. Prospective controlled trial of effect of medical emergency team on postoperative morbidity and mortality rates. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:916–21. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000119428.02968.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellomo R, Goldsmith D, Uchino S, et al. A prospective before-and-after trial of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2003;179:283–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buist MD, Moore GE, Bernard SA, Waxman BP, Anderson JN, Nguyen TV. Effects of a medical emergency team on reduction of incidence of and mortality from unexpected cardiac arrests in hospital: preliminary study. BMJ. 2002;324:387–90. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7334.387. see comment. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Priestley G, Watson W, Rashidian A, et al. Introducing critical care outreach: a ward-randomised trial of phased introduction in a general hospital. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1398–404. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sharek PJ, Parast LM, Leong K, et al. Effect of a rapid response team on hospital-wide mortality and code rates outside the ICU in a children's hospital. JAMA. 2007;298:2267–2274. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.19.2267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winters BD, Pham J, Pronovost PJ. Rapid response teams--walk, don't run. JAMA. 2006;296:1645–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.13.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winters BD, Pham JC, Hunt EA, Guallar E, Berenholtz S, Pronovost PJ. Rapid response systems: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1238–43. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000262388.85669.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeVita MA, Bellomo R. The case of rapid response systems: are randomized clinical trials the right methodology to evaluate systems of care? Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1413–4. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000262729.63882.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hillman K, Chen J, Cretikos M, et al. Introduction of the medical emergency team (MET) system: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:2091–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66733-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jolley J, Bendyk H, Holaday B, Lombardozzi KA, Harmon C. Rapid response teams: do they make a difference? Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2007;26:253–60. doi: 10.1097/01.DCC.0000297401.67854.78. quiz 261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donaldson N, Shapiro S, Scott M, Foley M, Spetz J. Leading successful rapid response teams: A multisite implementation evaluation. J Nurs Adm. 2009;39:176–81. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31819c9ce9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patton MQ. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research. second. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guralnick S, Rushton J, Bale JF, Jr, Norwood V, Trimm F, Schumacher D. The response of the APPD, CoPS and AAP to the Institute of Medicine report on resident duty hours. Pediatrics. 2010;125:786–90. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowenstein J. Where have all the giants gone? Reconciling medical education and the traditions of patient care with limitations on resident work hours. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46:273–82. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2003.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bristow PJ, Hillman KM, Chey T, et al. Rates of in-hospital arrests, deaths and intensive care admissions: the effect of a medical emergency team. Med J Aust. 2000;173:236–40. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb125627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan PS, Khalid A, Longmore LS, Berg RA, Kosiborod M, Spertus JA. Hospital-wide code rates and mortality before and after implementation of a rapid response team. JAMA. 2008;300:2506–13. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeVita MA, Braithwaite RS, Mahidhara R, Stuart S, Foraida M, Simmons RL. Use of medical emergency team responses to reduce hospital cardiopulmonary arrests. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:251–4. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.006585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones D, Bellomo R, Bates S, et al. Long term effect of a medical emergency team on cardiac arrests in a teaching hospital. Crit Care. 2005;9:R808–15. doi: 10.1186/cc3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Offner PJ, Heit J, Roberts R. Implementation of a rapid response team decreases cardiac arrest outside of the intensive care unit. J Trauma. 2007;62:1223–7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31804d4968. discussion 1227-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pittard AJ. Out of our reach? Assessing the impact of introducing a critical care outreach service. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:882–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Association of American Medical Colleges. Rapid response teams yield mixed results. [Accessed: 12/28/2009];AAMC Reporter. 2009 Apr; http://www.aamc.org/newsroom/reporter/april09/rapid.htm.

- 26.Barbetti J, Lee G. Medical emergency team: a review of the literature. Nurs Crit Care. 2008;13:80–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2007.00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenward G, Castle N, Hodgetts T, Shaikh L. Evaluation of a medical emergency team one year after implementation. Resuscitation. 2004;61:257–63. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones D, Baldwin I, McIntyre T, et al. Nurses' attitudes to a medical emergency team service in a teaching hospital. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:427–32. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.016956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buist M. The rapid response team paradox: why doesn't anyone call for help? Crit Care Med. 2008;36:634–6. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181629C85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bagshaw SM, Mondor EE, Scouten C, et al. A survey of nurses' beliefs about the medical emergency team system in a canadian tertiary hospital. Am J Crit Care. 19:74–83. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2009532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cretikos MA, Chen J, Hillman KM, Bellomo R, Finfer SR, Flabouris A. The effectiveness of implementation of the medical emergency team (MET) system and factors associated with use during the MERIT study. Crit Care Resusc. 2007;9:206–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]