Preface

Protein kinase C (PKC) has been a tantalizing target for drug discovery ever since it was first identified as the receptor for the tumor promoter phorbol ester in 19821. Although initial therapeutic efforts focused on cancer, additional diseases, including diabetic complications, heart failure, myocardial infarction, pain and bipolar disease were targeted as researchers developed a better understanding of the roles that PKC’s eight conventional and novel isozymes play in health and disease. Unfortunately, both academic and pharmaceutical efforts have yet to result in the approval of a single new drug that specifically targets PKC. Why does PKC remain an elusive drug target? This review will provide a short account of some of the efforts, challenges and opportunities in developing PKC modulators to address unmet clinical needs.

Introduction

Protein kinase C (PKC) is a family of highly related protein kinases that have been a focus of drug discovery effort for the past twenty years. Much of the interest in PKC began with the discovery that members of this family of isozymes are activated in a variety of diseases as evidenced using human tissue studies and animal models. There is evidence for a critical role for PKC in diabetes2, in cancer3, in ischemic heart disease4 and heart failure5, in some autoimmune diseases6, in Parkinson’s disease7,8 Alzheimer’s disease9, and in bipolar disease10,11, in psoriasis12, and in many other important human diseases. However, which PKC isozyme contributes to the pathology of a given disease and at what point during the disease progression is it critical, can be answered only when using PKC isozyme-specific tools.

Much of what we know about the functions of each PKC isozyme in normal and disease states is based on use of genetic tools. These include manipulation of the level of a given isozyme by over-expression, siRNA knock-down, and complete elimination (knock-out) of the genes encoding specific PKC isozymes, or by inhibiting a given isozyme through expression of the corresponding dominant negative or catalytically ‘dead’ isozyme. However, such genetic approaches are limited to cells in culture or to in vivo studies that are confined mainly to one species – mice. Since mice are often not the appropriate/ideal animal model for many human diseases, additional studies were limited to using small molecule pharmacological tools. Unfortunately, developing pharmacological tools that affect the function of just one PKC isozyme has proven to be difficult, in part, because of the great homology between protein kinases, in general, and between PKC isozymes, in particular.

Since selective regulators of PKC isozymes were not used in many studies, the main questions in the PKC field remain unresolved. Why does each cell have multiple PKC isozymes? Are they redundant in their roles? What defines the functional specificity of each isozyme? Finally, and relevant to this review, what is the role of individual PKC isozymes in human diseases and are there ways to selectively regulate a culprit isozyme as a treatment for a given disease?

It has been more than 25 years since PKC isozymes have been cloned and their role in human diseases has been recognized. This review summarizes the efforts to generate PKC isozyme-selective pharmacological tools and how these were applied to identify the isozyme to target for drug development. To better discuss the challenges in targeting PKC for therapeutic development, we provide an overview of the biology of the members of the PKC family, their role in specific diseases, and analyze the classes of PKC regulators that have been developed and how they were applied in preclinical research. We conclude with a summary of clinical trials in which several of these regulators were tested as therapeutics for human diseases and some lessons learned from these drug discovery and development efforts.

The protein kinase C family

There are over 450 protein kinases in the human genome13. Some of these kinases phosphorylate only one or very few protein substrates, whereas others can phosphorylate a large number of substrates and therefore regulate a number of cellular responses. PKC isozymes belong to the latter group of kinases, phosphorylating serine and threonine (S/T) residues on a large number of proteins.

The PKC enzymes were identified over 30 years ago, as kinases that are activated by proteolysis14. Soon after, it was found that diacylglycerol activates the intact enzyme15, although the means by which diacylglycerol levels are regulated was not known at the time. Five years after the first description of PKC, it was found that PKC could be activated by the tumor promoter phorbol ester1. This discovery opened up the field of PKC as a target for drug development – first in cancer and then in many other diseases. However, the study was further complicated by the finding that there are eight homologous PKC isozymes: α, βI, βII, γ, δ, ε, θ and η16–19 products of seven highly related genes (Fig. 1). Many PKC isozymes are present within the same cell and are activated by the same stimuli. An additional distant subfamily of atypical PKC isozymes, comprised of PKCζ and λ/ι, exists, although these are not discussed further in this review, as they do not respond to the same second messenger, and they share less sequence homology than the eight other members20,21.

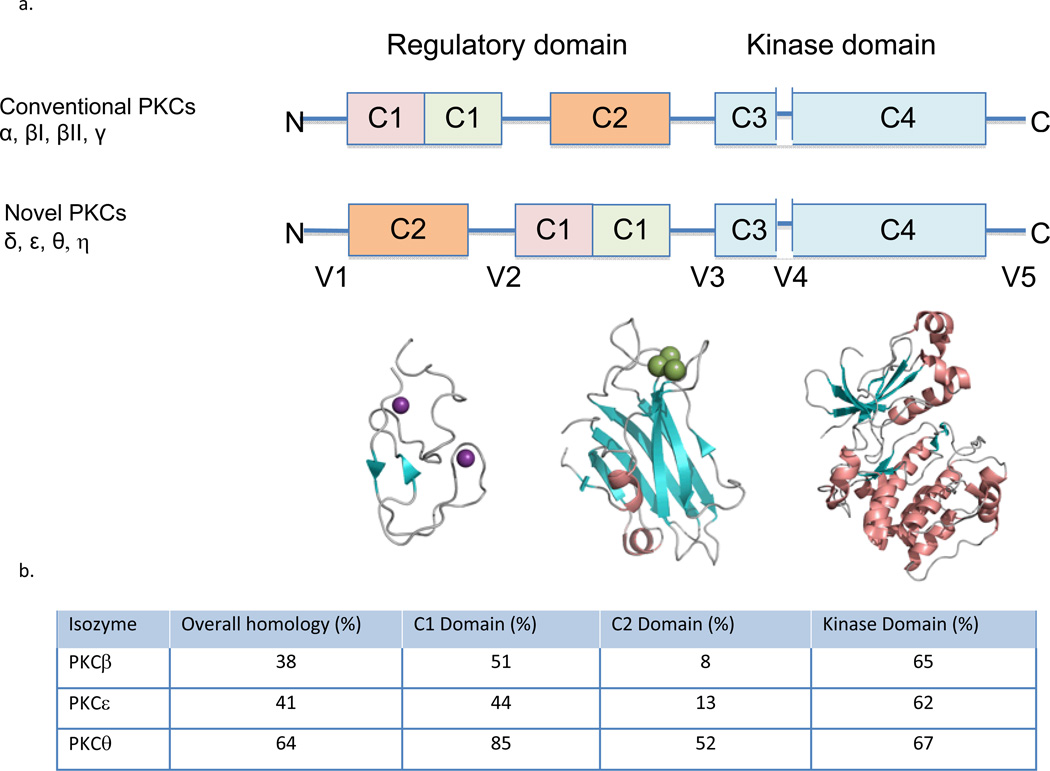

Figure 1.

a. Domain composition of PKC family members is shown in a stick scheme (not to scale). The structure of PKCβII (3PFQ) by domains; the diacylglycerol- binding C1a domain, the phosphatidylserine- (and calcium-) binding C2 domain, and the kinase domain. The secondary structures are α helix (in orange), β strands (in cyan) and loops (in gray), Zn2+ in purple and Ca2+ in green. b. The homology of different PKC isozymes to PKCδ. The C2 domain is the least conserved between the isozymes as compared with the other domains, suggesting that pharmacological tools that focus on the C2 domain are more likely to be isozyme-selective.

Similar to many other protein kinases, PKC has a regulatory region and a catalytic region. The catalytic region, or the kinase ‘business end’ of the enzyme, resides in the C-terminal half of PKC (Fig. 1). It contains a conserved ATP/Mg-binding site and a binding site for the phospho-acceptor sequence in the substrate proteins. The N-terminal half of the enzyme is the regulatory region (Fig. 1). In the inactive state, the regulatory region (comprised of two conserved C1 and C2 domains) is bound to the catalytic region (Fig. 2, bottom) and inhibits the activity of the enzyme. Dissociation of this intra-molecular inhibitory interaction results in activation of the enzyme (Fig. 2, top). Both the catalytic and the regulatory domains can be targeted for generating drugs to affect PKC activity (inhibition or activation), but each domain also presents challenges in achieving selective and safe drugs. As will be discussed below, the greatest homology between the PKC isozymes is in the catalytic domain. The PKC isozymes differ more from each other in the C2 region in the regulatory domain, as compared with the catalytic domain as well as in the intervening (the so called variable, or V) regions (Fig. 1). Much of the attention in developing drugs initially focused on the catalytic (kinase) domain and the second messenger-binding domain, the C1 domain. A greater isozyme selectivity, however, was associated with drugs focusing on the C2 region and the intervening sequences between the domains (the variable, V, regions), as discussed below.

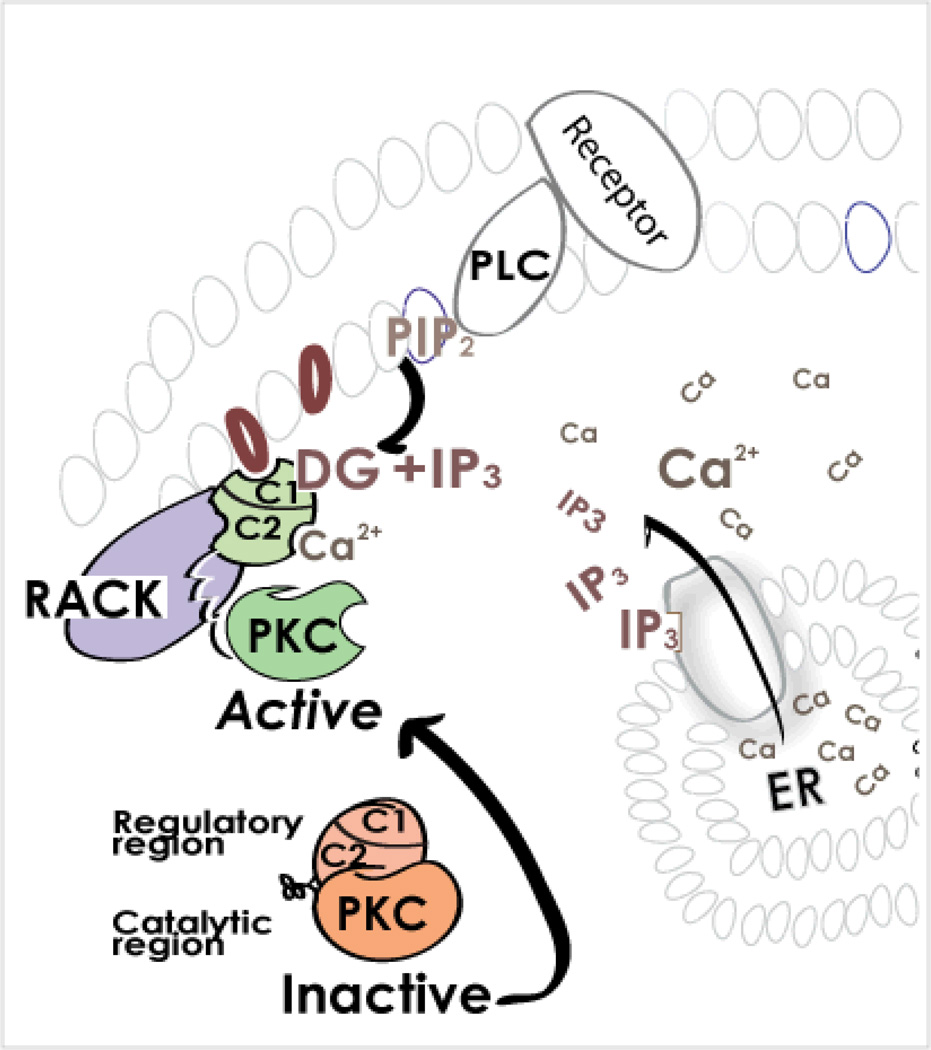

Figure 2. What processes lead to dissociation of the intra-molecular inhibitory interaction in PKC and to activation of the enzyme?

All PKCs require the binding of diacylglycerol (DG) to the C1 domain of the regulatory region for activation. Conventional PKCs also require calcium (Ca2+) binding to the C2 domain of the regulatory region. These second-messengers are generated following the binding of certain hormones, neurotransmitters or growth factors to their corresponding receptors. The consequent activation of membrane-associated phospholipase C (PLC) results in hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol-bisphosphate (PIP2), a membrane phospholipid, to DG and inositol trisphosphate (IP3). IP3, in turn, triggers the release of calcium from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), causing a rise in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration. Therefore, a single event (receptor-dependent phospholipase C activation) leads to generation of the two second-messengers that are required to activate both the conventional and novel PKCs. The rise in DG and Ca2+ leads to activation of PKC and its translocation from the cytosol to the plasma membranes as well as to other subcellular locations, where each isozyme interacts with its anchoring protein, RACK. When bound to RACK and the second messenger activators DG (and Ca2+ for the conventional PKC isozymes), PKC is then active, phosphorylating a number of substrates that are nearby, thus leading to diverse cellular responses.

Activation of PKC

PKC isozymes are activated by a variety of hormones, such as adrenalin and angiotensin, by growth factors, including epidermal growth factor and insulin, and by neurotransmitters such as dopamine and endorphin; these stimulators, when bound to their respective receptors, activate members of the phospholipase C family, which generates diacylglycerol, a lipid-derived second messenger15 (Fig. 2, upper right). Of the eight-members of the PKC family that are discussed here, the novel isozymes (PKC δ, ε, θ and η) are activated by diacylglycerol alone, whereas the four conventional PKC isozymes (PKCα, βI, βII and γ) also require calcium for their activation (Fig. 1). Cellular calcium levels are elevated along with diacylglycerol, because the latter is often co-produced with inositol trisphosphate (IP3), which triggers calcium release into the cytosol from internal stores (Fig. 2, lower right).

Further complication in the field arises because activation of PKC can also occur in the absence of the above second messengers. High levels of cytosolic calcium can directly activate phospholipase C, thus leading to PKC activation in the absence of receptor activation. A number of post-translational modifications of PKC were also found to lead to activation of select PKC isozymes both in normal and disease states22. These include activation by proteolysis between the regulatory and the catalytic domain that was noted to occur for PKCδ, for example23. Phosphorylation of a number of sites may be required for maturation of the newly synthesized enzyme24, but also for activation of mature isozymes, e.g. H2O2-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ25,26. Other modifications including oxidation, acetylation and nitration have also been found to activate PKC22. Whether PKC, activated by these modifications, can be inhibited specifically and how critical these forms of activation are for a given disease state is yet to be determined.

Finally, a hallmark of PKC activation, first described in 1982, is that it is always associated with translocation of the enzyme from the cytosolic (soluble) fraction to the cell particulate fraction, which includes the plasma membrane, but also many other cellular organelles27. It is this feature of isozyme-selective anchoring to different subcellular sites that enabled the generation of a class of more selective inhibitors and activators of individual PKC isozymes27.

Roles and functions of PKC isozymes

After the first descriptions of the cloning of eight different PKC isozymes16–19, isozyme-specific gene expression studies demonstrated the surprising finding that most PKC isozymes are ubiquitously expressed in all tissues at all times of development. Yet, it is quite clear that PKC isozymes have unique and sometimes opposing roles in both normal signaling and disease states28,29. In fact, even the same isozyme can have opposing roles in the same cell, depending on the context of the stimulation30.

Much of the initial work on PKC in cellular response employed phorbol esters, which irreversibly activate all the PKC isozymes and therefore does not represent well the transient activation that occurs by diacylglycerol. Nevertheless, using phorbol esters, PKC was found to regulate many cellular functions, including cell proliferation, and cell death, increased gene transcription and translation, altered cell shape and migration, regulation of ion channels and receptors, regulation of cell-cell contact and secretion, etc. Because phorbol esters are not isozyme-selective, this early work did not identify which of the iszoymes regulate a given function.

Subsequent studies that aimed to determine if a particular PKC isozyme participates in the studied cellular event or pathology always included determining whether the isozyme is translocated to the cell particulate fraction; only a subset of the studies also confirmed that the translocated isozyme is catalytically active, by measuring kinase activity, in vitro. Translocation is measured by cell fractionation as well as by microscopy (using either light and/or electron microscopy). Thus, translocation assays and examining changes in the levels of particular PKC isozymes were used as markers for activation of a given isozyme in the measured response.

PKC in disease

Increased activation of select PKC isozymes have been observed in cancer3,31, diabetes32, ischemic heart disease33,34, acute and chronic heart disease35, heart failure34,36, lung37 and kidney38,39 diseases, a number of dermatological diseases including psoriasis12, in autoimmune diseases6,40 and in a number of neurological diseases, including stroke41, Parkinson’s disease7,8, dementia42, Alzheimer’s disease9,43, pain44 and even in psychiatric diseases, including bipolar disease10. Initially, the role of PKC in various illnesses was implicated because abnormal activation or levels of a particular isozyme in the disease state was noted. However, this correlation between PKC activation and a disease could not determine whether the activated isozyme leads to the pathology, prevents it, or has no role in it. To address a causal role of PKC in a particular disease both genetic and pharmacological tools have been used. Table 1 lists some of the diseases and names the likely isozymes that contribute to these pathologies. Below, we will discuss some of these diseases and the pathological role of specific PKC isozymes in more detail.

Table 1.

PKC isozymes that are implicated in human diseases

| Disease | Main PKC isozyme implicated in the pathology Ref | The pathology associated with PKC |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer | PKCα196 | Proliferation, intravasation & metastasis |

| PKCβ54 | Vasculogenesis and cancer cell invasion | |

| PKCδ30 | Angiogenesis | |

| PKCε197 | Proliferation, pro-survival, metastasis, resistance to chemotherapy | |

| PKCθ58 | Gastrointestinal stromal cell proliferation | |

| PKCη89 | Glioblastomal cancer increased proliferation, resistance to radiation | |

| Diabetic complications | PKCβII2 | Vascular complications |

| PKCβ198,199 | Knockout attenuates obesity and increased glucose transport (role of βI?) | |

| PKCδ60 | Stimulation of islet cell function | |

| Ischemic heart disease | PKCδ mediates injury52,160,192,200 | Increased ROS, decreased ATP generation increased apoptosis and necrosis |

| PKCε is protective; useful for predictive ischemia such as in surgery or organ transplantation4,118,160,195,201 | Protection of mitochondrial functions and proteasomal activity, activation of ALDH2 and reduction of aldehydic load | |

| Heart failure | PKCα202,203 | Decreased cardiac contractility, myofilaments force , uncoupling β adrenergic receptor |

| PKCβII5,108,204 | In rats, decreased proteasomal activity and removal of misfolded proteins in several models, disregulate calcium handling. | |

| PKCβII205–209 | In mice*, overexpression results in hypertrophy or is not required for hypertrophy. It also decreases or increases contractility. | |

| PKCε4,5,35 | Increased fibrosis, fibroblasts proliferation, and inflammation | |

| Psoriasis | PKCδ12,66 | Increased inflammation, increased proliferation, dis-regulation of angiogenesis |

| Pain | PKCγ44 | Key mediator of pain in dorsal root ganglia |

| PKCε44 | Key mediator of pain in spinal cord | |

| Autoimmunity and inflammation | PKCδ210,211 | B cell development, inflammation |

| PKCθ6,212 | Involved in many T cell responses | |

| Stroke | PKCδ41,213–215 | Increased mitochondrial fission, ROS production and decreased blood-brain barrier |

| PKCε41,216 | Cytoprotective, increased cerebral blood flow | |

| Bipolar disorders | PKCα10,11,65,112 | Altered gene expression |

| PKCε63 | Altered neuronal transmission | |

| Asthma and other lung diseases | PKCθ217 | Inflammation, airway hyper-responsiveness |

| PKCδ218 (loss of others may contribute to pathology) |

Eosinophils activation | |

| Parkinson’s disease | PKCδ8,219,220 | Inflammation, neuronal cell death |

Footnote: some work using gene knockout and over-expression in mice is not discussed here, because there are conflicting data on the matter and the explanation for the conflicting is not always clear and is beyond the scope of this review.

Whereas studies using rat models find that inhibition of PKCβII is protective from heart failure5,204, other studies using mouse genetic models provide conflicting data205–209. Whether these differences reflect species differences, dose of gene, strain of mice or other reasons remain to be determined.

Heart diseases

Significant effort has been invested in understanding the role of specific PKC isozymes in cardiac diseases, with much of the initial focus being placed on cardiac ischemia. After the seminal study of Downey and collaborators45, demonstrating that direct PKC activation prior to the ischemic event provides cardiac protection, several groups examined the role of PKC in this disease. However, the initial use of non-selective pharmacological tools led to conflicting data, leading to the conclusion that PKC is likely ‘a spectator’ rather than ‘a player’ in this response46. Subsequent studies with transgenic mice that express dominant negative regulators of specific isozymes and the use of selective pharmacological tools in a variety of species including rabbits, mice, rats and pigs explained the earlier ambiguity: Activation of PKCδ and ε has opposing consequences on the ischemic myocardium29. Whereas PKCε activation is cardioprotective4, PKCδ activation mediates much of the acute injury induced after transient myocardial ischemia28,47. Fig. 3 depicts some of the molecular basis for the opposing effects of these two isozymes in regulating mitochondrial function. The figure also depicts how activation of PKCε protects the proteasome from inactivation, which leads to a fast and selective degradation of the damaging PKCδ at reperfusion48 thus altering the balance between PKCδ and PKCε towards cardioprotection. Protection of the proteasome also improves cardiomyocyte health by enabling removal of oxidized and damaged proteins (Fig. 3). Box 1 provides a summary of the role of PKC isozymes in other cardiac diseases, including heart failure, atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction and cardiac arrhythmia.

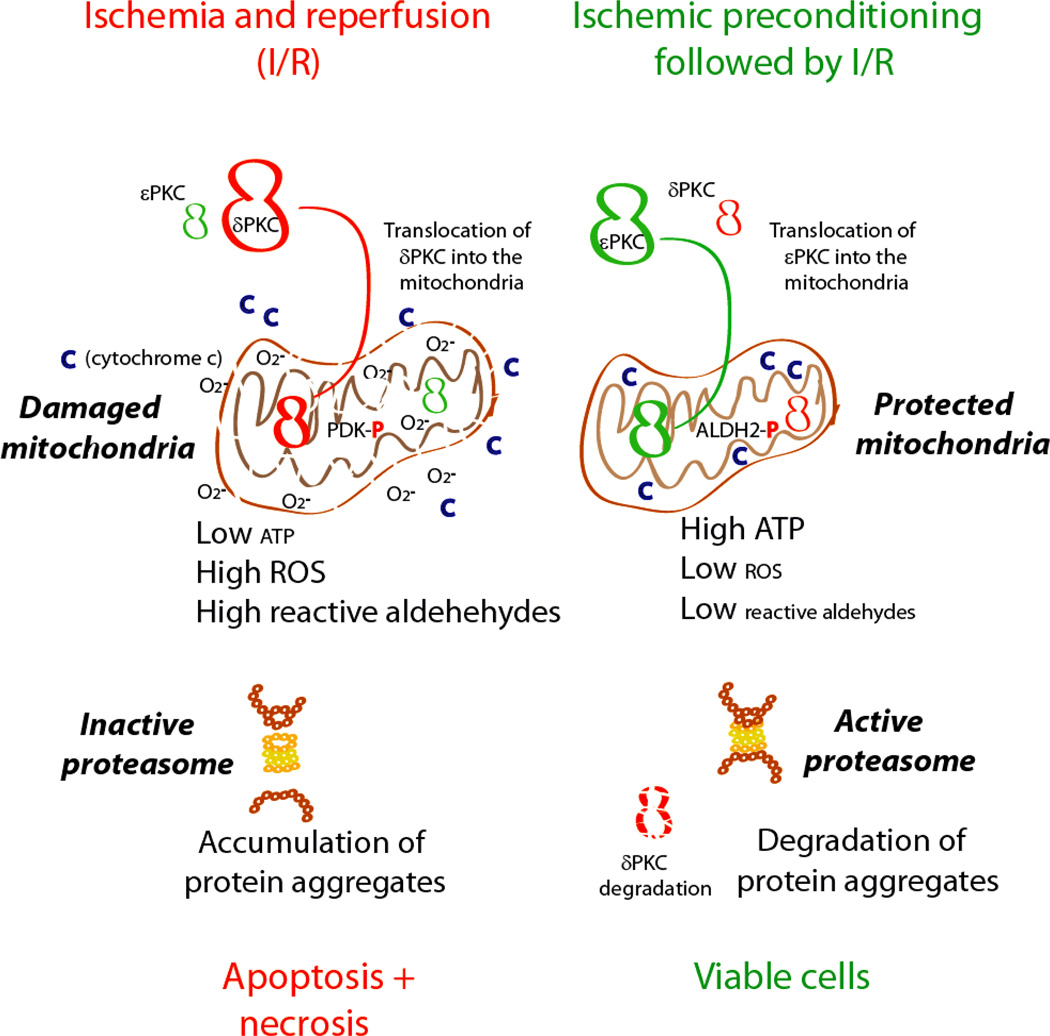

Figure 3. The role of PKC isozymes in ischemic heart disease.

Shown is how prolonged ischemia and reperfusion results in activation of PKCδ more than PKCε, leading to translocation of PKCδ into the mitochondria47, phosphorylation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK), which in turn phosphorylates pyruvate dehydrogenase47 and reduction in TCA cycle and ATP regeneration192. Mitochondrial dysfunction leads to higher ROS production and lipid peroxidation leads to accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and toxic aldehydes, such as 4-hydroxynonenal (4HNE), that interact and inactivate macromolecules including proteins, DNA and lipids193. Mitochondrial dysfunction and increase in ROS leads to both apoptosis29,194 and necrosis and severe cardiac dysfunction192. In contrast, ischemic preconditioning prior to prolonged ischemia and reperfusion provides cardioprotection by activating more PKCε4, which also translocates into the mitochondria92 and prevents mitochondrial dysfunction induced by prolonged ischemia and reperfusion. PKCε-mediated protection occurs, in part, by PKCε phosphorylation and actvation of aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2)195. Activated ALDH2 metabolizes aldehydes, such as 4HNE, thus reducing the aldehydic load and the mitochondrial and cellular damage. This results in improved mitochondrial functions and faster recovery of ATP levels. The reduced 4HNE levels also prevent direct inactivation of the peroxisome and thus enable fast removal of aggregated proteins. The active proteasome also selectively degrades activated PKCδ, increasing the balance in favor of the cardiac protective PKCε48.

BOX 1: PKC in cardiac disease.

-

Platelet activation at atheroslerotic site232:

The main isozyme found to be required for platelet aggregation is PKCα and PKCα inhibition is protective. Because PKCα knockout does not lead to excessive bleeding, an inhibitor of this isozyme may be safe for this indication. A role for other isozymes has also been described.

-

Myocardial infarction (MI) and acute ischemia and reperfusion injury4,118,233,234:

Both δ and PKCε are activated in the ischemic human heart and in a number of animal models of MI. Selective activators and inhibitors of this isozyme and work in transgenic mice showed that PKCε activation is protective when occurring prior to the ischemic event or right at reperfusion, mimicking protection induced by short ischemic period prior to the prolonged ischemic event (pre-conditioning) or right at reperfusion (post-conditioning). PKCε activation protects mitochcondrial functions, in part via activation of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (ALDH2), which removes toxic aldehydes, products of lipid peroxidation195. In contrast, PKCδ inhibition at reperfusion is protective. PKCδ activation mediates much of the damage, by activating mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase47, which inhibits pyruvate dehydrogenase and ATP regeneration and triggers necrosis. PKCδ activation also induces reperfusion-induced apoptosis235 of both endothelial and cardiac myocytes, thus leading to further tissue injury. See summary on the opposing roles of PKCδ and PKCε in MI (Fig. 4).

-

Cardiac arrhythmia236

PKCε inhibits fatal ventricular arrhythmia associated with ischemia and reperfusion injury, possibly through inhibition of mast cell degranulation and activation of ALDH2 in these cells, inhibition of L-type calcium activation in cardiac myocytes, inhibition of sodium channel and decreased connexin 43-dependent intermyocyte communication via gap junction. Note that PKCδ inhibitor, which like PKCε activator, also reduces infarct size in the MI model, does not inhibit post-MI cardiac arrhythmia, indicating that reduction of infarct size per se is insufficient to prevent arrhythmia.

-

Compensatory hypertrophy35

PKC α, βII, δ and ε are all activated during compensatory hypertrophy. However, only sustained inhibition of PKCε is cardioprotective during compensatory hypertrophy in hypertensive rats; selective inhibition of the other isozymes shows no benefit237. Over-expression of PKCα in decreases contractility and knockout of PKCα enhances contractility238 and selective activation of δPKC increases cardiac mass28, but also increases fibroblasts proliferation239 and therefore may be deleterious.

-

Heart failure35

Transgenic and knockout mice demonstrated that αPKC mediates HF in mice203. However, failed human hearts show at most a small increase in αPKC activation. In contrast, a more than 2X increase in βPKC activation33,34,240,241 and in two models of HF in rats (βIIPKC )109. Conflicting data were obtained on the role of PKCβ in HF using transgenic mice205–209. However, the use of highly selective pharmacological tools demonstrated that inhibition of PKCβII is therapeutic, at least in part by 1. preventing proteasomal inactivation and the resulting accumulation of misfolded proteins204; 2. by inhibiting decreases the contractile dysfunction159,207; and 3. by inhibiting increased cardiac fibrosis and improving calcium handling109,242

-

Diabetic cardiomyopathy2

Hyperglycemia activates PKC α, βII, δ and ε. PKCδ activation may prevent atherosclerosis. PKCε inhibition accelerated diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction and death in mice. However, it appears that inhibition of PKCβ alone (perhaps βII) is sufficient to protect from endothelial cell dysfunction, insulin resistance and cardiomyopathy.

-

Endothelial dysfunction and vascular restenosis243

PKC α, β, and δ increase smooth muscle cell (SMC) migration by promoting actin polymerization and enhancing cell adhesion. Sustained treatment with PKCβ and PKCδ inhibitors each provides some therapeutic benefit in rat and mice models. PKCδ inhibition and PKCε activation inhibit vasculopathy after transplantation50 or after balloon injury and stenting244. Also, acute inhibition of PKCδ greatly reduces MI-induced microvascular dysfunction by inhibiting endothelial cell death235 and by inhibiting re-occlusion of microvessels during reperfusion235.

Organ transplantation

There are two pathologies that need to be addressed to benefit patients after organ transplantation. The first relates to the ischemia and reperfusion injury to the transplanted organ, which, depending on its severity, can lead to both acute and chronic rejection (due to irreversible tissue damage49,50). The second pathology in which PKC plays a role relates to the immune response to the transplanted organ51, leading to organ rejection. The role of δ and εPKC in ischemia and reperfusion injury has been discussed above. The consequences of reducing this acute injury on functioning of the transplanted organ has been demonstrated, for example, in a study of cardiac transplantation; vascular occlusion due to increased inflammatory stimulation (vasculopathy) is inhibited if ischemia and reperfusion injury is reduced by treating with an activator of PKCε and inhibitor of PKCδ at the minutes before organ harvest and right after organ transplantation36,50,52. PKCθ, a critical isozyme for T cell activation, has also been implicated in the immunorejection of the transplanted organ and inhibition of this isozyme can reduce T cell activation, subsequent migration and further immune response6,53.

Cancer

It is not surprising that different cancer types depend on the activity of different PKC isozymes. Given PKC’s role in both cellular proliferation (PKCα)31 and vasculogenesis (PKCβ)54, two processes that are critical for cancer growth and metastasis, PKC has been targeted for cancer therapy. Further, genetic and pharmacological studies showed that other PKC isozymes are also important in this disease. For example, PKCδ activation increases angiogenesis in human prostate cancer cells55, PKCε overexpression is observed in stomach, lung, thyroid, colon, and breast cancers3, PKCη has been implicated in non-small cell lung cancer where the increased levels of PKCη correlated with tumor aggressiveness and cell proliferation levels56,57, and a role for PKCθ overexpression has been associated with gastrointestinal stromal tumors58.

Diabetic complications

Preclinical research suggests that hyperglycemia leads to activation of PKCβ, which may play an important role in mediating the microvascular disease complications of retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy59. Hyperglycemia leads to chronic activation of PKCβ, causing aberrant signaling and a variety of pathologies such as cytokine activation and inhibition, vascular alterations, cell cycle and transcriptional factor mis-regulation, and abnormal angiogenesis2. Clinical trials that examine the benefit of PKCβ inhibition are described below.

PKCδ, on the other hand, was found to have a major role in islet cell function and insulin response60. The authors showed that changes in the level and activity in PKCδ between mice strains correlates with risk of insulin resistance, and glucose tolerance. There is also loss of inflammation associated with insulin resistance in PKCδ deficient mice60. Therefore, inhibiting PKCδ may also provide a treatment for metabolic syndrome.

Bipolar disorders

PKC is highly expressed and heterogeneously present within the brain, where it plays important roles in regulating pre- and post-synaptic neurotransmission, coordinating intracellular signaling in response to neurotransmitter activation, and modulating changes in gene expression and neuronal plasticity11,61,62. Evidence to support a role for PKC signaling in bipolar disorder includes: 1) amphetamine-induced “manic symptoms” in rodents are correlated with PKC activation in the brain63; 2) platelets from patients with mania show an increased PKC activity and translocation to serotonin stimulation when compared to platelets from control subjects64; 3) post-mortem studies of brains of patients with bipolar disorder revealed increased levels of PKC activation and translocation65; 4) both lithium and valproate, two efficacious drugs in bipolar illness, indirectly decrease the activity of both PKCα and PKCε61.

Other diseases

PKC is a central mediator in many signaling cascades. As described in this review and many others, the 8 family members of PKC are implicated in disease states based not only on their function, but also on their activation or inhibition states and on changes in their levels. There are many other pathologies where PKC has been implicated based on the above criteria. These include lung37 and kidney38,39 diseases, dermatological diseases including psoriasis12,66, autoimmune diseases6,40 as well as neurological diseases, including stroke41, Parkinson’s disease7,8,67, Alzheimer’s disease43 and pain44. Whether PKC is critical in mediating these pathologies or whether PKC activation is caused by the pathologies remains to be determined using selective pharmacological tools in animal models of these diseases.

PKC inhibitors and their application in pre-clinical research

It has long been a goal of academic and industrial researchers to develop PKC-specific inhibitors that are also isozyme selective. Efforts to identify selective modulators of PKC have taken disparate approaches (see Fig. 4). These include development of (a) ATP-competitive small molecule inhibitors that bind to the ATP site of the kinase catalytic domain, (b) phorbol esters and derivative activators and inhibitors that bind to the C1 domain, mimicking DG-binding, and c) peptides that disrupt protein/protein interactions between the regulatory region and RACK (Fig. 4). Table 2 lists the names, structure, and degree of selectivity of some of the inhibitors and activators of PKC that were generated during the past 20 years with emphasis on those that were tested in the clinic.

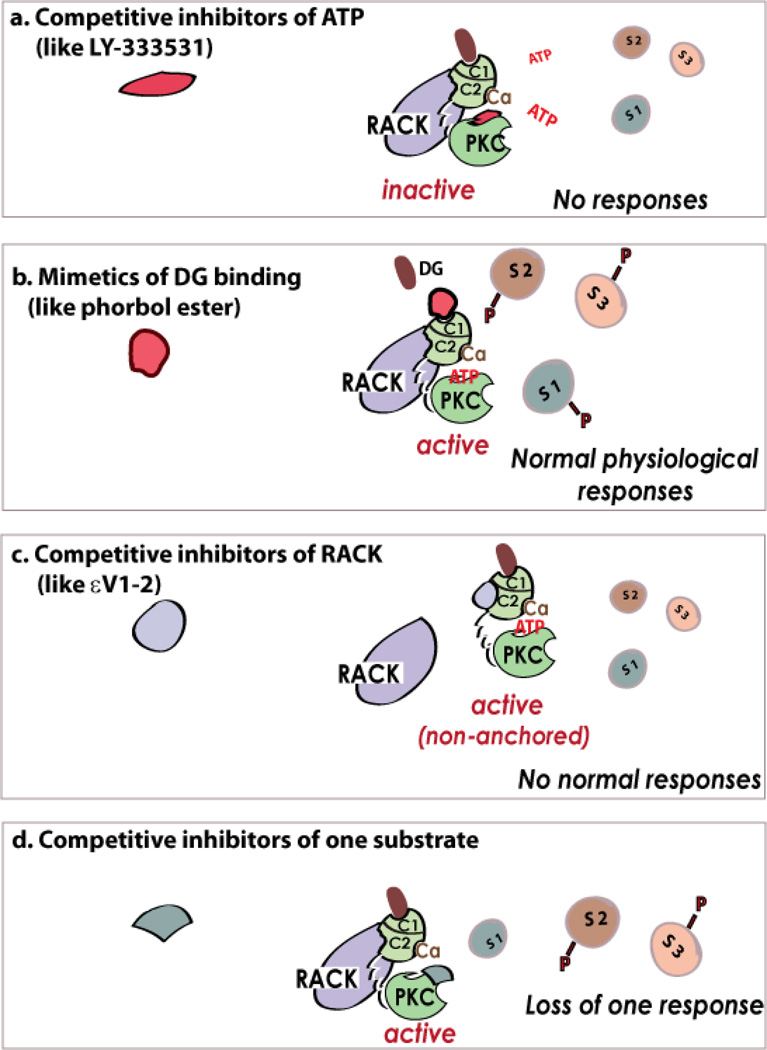

Figure 4. Inhibitors of PKC.

Inhibitors of ATP binding to the kinase inhibit the phosphorylation of all the substrates (e.g., S1, S2, S3) of that isozyme, and to a loss of all cellular responses (a). PKC regulators that target the DG-binding site, and act as activators (b) or inhibitors (not shown). The inhibitors can also inhibit anchoring of the enzyme to its RACK that rings the activated isozyme next to its substrates, thus leading to inhibition of all the physiological responses of that isozyme (c). Theoretically, the active, but non-anchored PKC may phosphorylate new substrates. However, this was not observed perhaps because activation in the absence of RACK binding is very transient and/or because the cytosolic phosphatases remove such non-physiological phosphorylations. The same isozyme is localized to several subcellular locations following activation90 and therefore near a subset of substrates and away from others. Further, there are reports on direct binding of substrates to PKC at sites that are distinct from the phospho-donor/ phospho-acceptor sites. Therefore, inhibitors of protein-protein interactions at a specific subcellular location or with a specific substrate may provide unique inhibitors of the phosphorylation of one substrate and not the others (d). Such separation-of-function inhibitors will have great value, as each PKC isozyme phosphorylates substrates and not all these phosphorylation events contribute to the pathological condition.

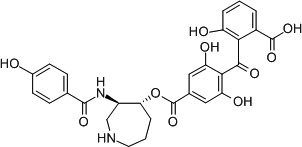

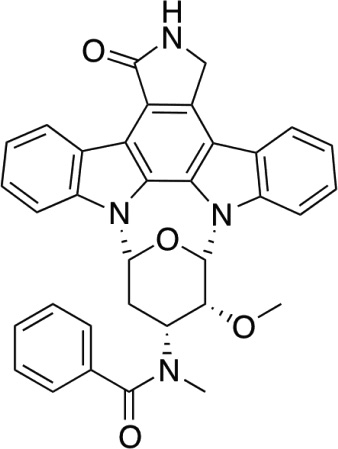

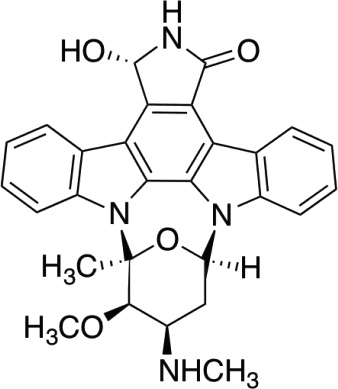

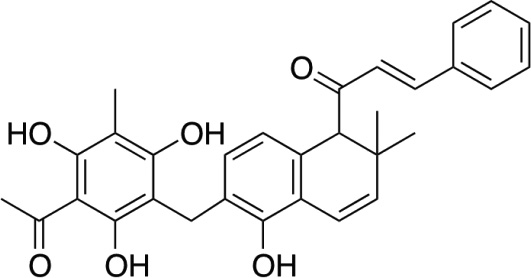

Table 2.

Main classes of PKC inhibitors used in the clinic

| Name Reference | Structure | PKC Selectivity (site) |

Isozyme Selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balanol76,221 |  |

An inhibitor of PKC and PKA (ATP-binding) | e.g., N-Tosyl derivative221 βII>βI>η>δ>α>ε>>>PKA |

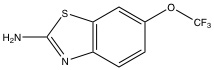

| Riluzole77 |  |

Likely inhibits other S/T kinases (ATP-binding) | Preferential inhibitor of PKCα |

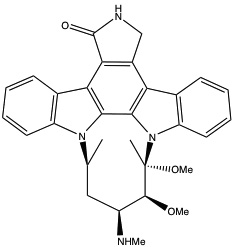

| Staurosporin222 |  |

(ATP-binding) | Pan-PKC inhibitor |

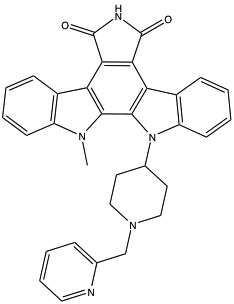

| Enzastaurin223 |  |

(ATP-binding) | 3- to 5-fold selectivity for βPKC inhibition |

| δV1-128 (KAI-9803 or Delcasertib*) | SFNSYELGSL-carrier** | δPKC inhibitor (RACK-binding) | >1,000X over other isozymes |

| εV1-2224 (KAI-1678*) | EAVSLKPT-carrier** | εPKC inhibitor (RACK-binding) | >100X over other isozymes |

| HDAPIGYD-Carrier** | εPKC activator (intramolecular interaction in PKC) | >100X over other isozymes | |

| Aprinocarsen225 | Anti-sense oligonucleotide that targets αPKC mRNA | PKCα inhibitor (expression) | PKCα |

| Midostaurin (PKC412)152,226 |  |

(ATP-binding) | A number of protein kinases, including PKC |

| UCN-01227 (7-hydroxy-staurosporin) |  |

(ATP-binding) | A number of protein kinases including tyrosine kinases and classical PKC at a similar IC50 (25–50nM) |

| Rottlerin72226 5, 7, dihydroxy-2,2-dimethyl-6-(2,4,6-trihydroxy-3-methyl-5-acetlybenzyl)-8-cinnamoyl-1,2-chromene |  |

PKCδ inhibitor (ATP-binding) | PKC δ, but also calcium calmodulin kinase VI at a similar IC50 (5µM). |

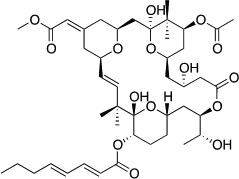

| Bryostatin 1228 |  |

C1 domain | 2-fold selectivity for PKCε over PKC α,δ84 |

The exact composition of KAI compounds is unavailable.

Carrier is the TAT-derived peptide, CYGRKKRQRRR229

ATP-competitive small molecule inhibitors

The highest similarity among PKC isozymes is in their catalytic domain (Fig. 1). The high degree of sequence homology and structural similarity for this region among PKC isozymes and the similarity with this region in other protein kinases suggests that generating isozyme-selective inhibitors for the ATP-binding site is extremely challenging68 (Box 2). Typically, inhibitors of kinase active sites have been discovered by high-throughput screening approaches or in silico methods, which use protein structures and computational methods to predict small molecules that best interact with the given site in the protein. Clinical candidates that inhibit PKC isozymes through an ATP- competitive mechanism have been discovered through high-throughput screening, and subsequent medicinal chemistry optimization that was assisted by in silico design69. The best-characterized ATP-competitive small molecules are the bisindolemaleimides70. These water-soluble compounds bind to the ATP-binding pocket and limit phosphorylation. The classic example, staurosporine, has pan-PKC activity, binding all isozymes with a double-digit nanomolar dissociation constant (Kd). Unfortunately, staurosporine binds several other S/T kinases68. Medicinal chemistry efforts to develop a more selective inhibitor led to the discovery of enzastaurin, which is more selective for PKCβ over other isozymes71. However, subsequent studies demonstrated that enzastaurin inhibits other PKC isozymes as well as several other protein kinases at a similar Kd. Rottlerin exemplifies the difficulties of developing a PKC isozyme selective ATP-competitive small molecule inhibitor. First described as a PKC-inhibitor, with selectivity for PKCδ in 199472, multiple groups went on to characterize its activity both in vitro and in vivo. After much controversy, Soltoff et al,73 published a paper demonstrating its activity against several other enzymes. Newer generations of inhibitors, e.g., the phenylamino-pyrimidine74 and arylamino-pyridinecarbonitrile75 classes, show some specificity for PKCθ, with 10 to 100-fold selectivity over conventional PKC isozymes. Finally, compounds, such as balanol76 and rizuzol77, which were originally developed as inhibitors of PKA, also inhibit PKC.

BOX 2: Potential targets for drug development and challenges associated with these targets.

ATP-binding site (in the catalytic domain): The PKC catalytic domain within the PKC family is ∼70% homologous, and the ATP-binding site in all protein kinases is highly conserved. Therefore, generating a drug that selectively inhibits one kinase has been a great challenge if not impossible68.

DG-binding site (in the C1 domain): The C1 domain and the DG-binding site are highly homologous between isozymes (60–80% identity). Further, other non-PKC proteins have C1 domains that bind DG245. Therefore, generating a drug that selectively bind the C1 of one isozyme has been a challenge, but the work of Blumberg et al 246 identified some selective C1-binding molecules, as did some recent work by Wender et al 87.

Protein-protein interactions with anchoring proteins (in the C2 domain): RACKs27 anchor proteins that bind activated PKC, in part through the C2 domain, have not been identified for all the PKC isozymes. The C2 domain is structurally conserved between PKC isozymes, but sequence homology is less than 50%. Further, there are also other proteins and enzymes with a C2 domain.

Protein-protein interactions with other proteins that regulate the subcellular localization of the enzymes. (The location of the interaction sites has not always been identified, but is often in mediated by sequences unique for individual isozymes): At least three families of proteins interact with select PKC isozymes99. These are RACKs27 , annexins247 and 14-3-3248. Other proteins, including HSP9092, actin107, AKAPs249,250 and importins102 also interact with some PKCs and some show high selectivity. However, critical partner proteins and the interaction site with each partner have not been always identified.

Interaction between PKC isozymes and their substrates. (The location of the interaction sites has not always been identified, but is often in mediated by sequences unique for individual isozymes): Several PKC substrates were found to stably interact with the corresponding PKC isozymes. These were termed STICKs by Jaken and collaborators251. This kind of PKC-protein substrate interaction can be selectively disrupted (Mochly-Rosen et al, unpublished).

Activators and inhibitors that mimic DG-binding

The second class of PKC modulators targeting the C1 domain (Box 2) are those that mimic the binding of the C1 domain to the second messenger activator of the enzyme, diacylglycerol. A classic example is the tumor promoter, phorbol ester78, which mimics diacylglycerol and activates PKC. Based on the seminal work of Blumberg and coworkers, diacylglycerol binding-site on the C1 domain was characterized79, which led to better understanding of the diacylglycerol pharmacophore, and guided the design of potent PKC activators, e.g., diacylglycerol-lactones80. These diacylglycerol-lactones show 3–4 orders of magnitude higher affinity for PKC isozymes and a greater specificity for PKCα and PKCδ, as compared with the natural diacylglycerols81. The C1 binding site is also highly conserved among the isozymes, making it difficult to develop selective compounds. The best characterized of these compounds is bryostatin, a naturally occurring macrolactone, which has pan-PKC activity in the low nanomolar to picomolar range82. Several studies have shown some anti-cancer properties, albeit limited in utility in the clinic83. Preferred protection of PKC from down-regulation by the strong ligand, phorbol ester84 led to a function-oriented synthetic approach to the design of selective PKC-binding bryostatin analogues85. These molecules show isozyme selectivity in binding the C1 domain86 of various PKCs and may represent a novel class of PKC regulators87,88.

Inhibitors of protein/protein interactions between PKC and cognate proteins

A third class of PKC modulators inhibits protein-protein interactions found to be critical for the translocation (change in the subcellular localization) of PKC isozymes following activation. PKC translocation upon activation, first described in 1982 by Kraft, Sando and Anderson89, was assumed to reflect the binding of the enzyme to the lipid-derived second messenger diacylglycerol in the plasma membrane. However, microscopy and cell fractionation studies demonstrate that activated PKC isozymes are present in a variety of subcellular locations90. Activated PKC isozymes are found on cytoskeletal elements91, inside the mitochondria92, on the Golgi apparatus93, on endoplasmic reticulum93 on centrosomes94–96, at the nuclear membrane and inside the nucleus90. Because different activated PKC isozymes localize to distinct subcellular sites within the same cell84,85, we proposed in 1988 and subsequently demonstrated that these isozyme-unique localizations are mediated by unique protein-protein interactions between a given PKC isozyme and an anchoring protein that we termed RACK, for receptor for activated C-kinase27,97. Other proteins can selectively interact with PKCs to keep them in an active state, to anchor them next to a particular substrate or to shuttle them from one location to another98,99. Some of these PKC-binding proteins are highly selective. For example, RACK1 binds PKCβII but not PKCβI100, even though the isozymes are products of the same gene and differ only in the last 50 of the 750 amino acids encoded by this gene18,101. Other proteins bind more than one isozyme through different sites and for different purposes. For example, HSP90 binds both δ and PKCε. However, binding of PKCε is required for shuttling this isozyme into the mitochondria92, whereas binding of δPKC to HPS90 is required for shuttling of PKCδ into the nucleus102. What is more surprising is that although PKCδ also enters the mitochondria, this entry is independent of HSP9092. Furthermore, the interaction sites for PKCε and δ with HSP90 are distinct and a pharmacological tool has been devised to affect the interaction of one isozyme and not the other92. A review of proteins that interact with PKC isozymes is not provided here, but a short list of interacting proteins is provided within Box 2.

Since protein-protein interactions are thought to occur across relatively large, flat surfaces, prevailing wisdom suggests that small molecules that fit ‘greasy pockets’ are unlikely to work103. However, a rational approach to develop peptide inhibitors of protein-protein interactions refuted this notion104. In this approach, the respective binding sites of the two interacting proteins are predicted and short peptides (∼6–10 mer) with sequence homology to one of the interacting regions are found to effectively inhibit the corresponding protein-protein interaction. Box 3 provides a short summary of the rationale used to generate isozyme-selective inhibitors and activators of PKC and Table 3 lists some examples of peptides with biological activities.

BOX 3: Rational approaches to identify peptide inhibitors of protein-protein interaction (PPI) of PKC99,104,106 .

-

Sequence homology between two unrelated proteins that interact with PKC:

A peptide corresponding to a short homology between two unrelated PKC-binding proteins, annexin I and 14-3-3 is a PKC inhibitor252.

-

The least conserved sequences within a highly conserved region:

Peptides corresponding to the least conserved sequences between isozymes in the C2 domain are selective inhibitors of the function of the corresponding isozyme. For example, δV1-1 peptide, derived from a PKCδ-unique sequence in the C2 domain (aka V1 domain), is a selective inhibitor of PKCδ function28.

-

The most similar sequences between unrelated proteins that contain a homologous domain:

Both PKCβ and phospholipase C contain C2 domains and peptides corresponding to the most homologous regions are selective inhibitors of PKC and do not affect other C2-containing proteins253.

-

A short sequence of homology between PKC and its partner protein:

Often this sequence represents an auto-inhibitory site that interacts with the binding-site for the partner protein when PKC is inactive. The first PKC inhibitor to be identified is the pseudosubstrate peptide, corresponding to a sequence in PKC that mimics the phospho-acceptor site in the substrate254. The six amino acid pseudo-βRACK peptide, representing a short homologous sequence between PKCβII and RACK1, is a selective activator of PKCβII255. Similarly, ψεRACK peptide, corresponding to a sequence in PKCε that is homolgous to its RACK, is a selective activator of PKCε256. A peptide corresponding to a six amino acid homology between Hsp90 and PKCε increases the interaction of PKCε with Hsp90 and its function, but not the interaction of PKCδ with Hsp9092. Finally, separation of function inhibitors, representing a stretch of homology between a given isozyme and one of its protein substrates, inhibits the phosphorylation of that substrate and not any other substrates of the same isozyme (Mochly-Rosen, unpublished data).

Other ‘filters’ to confirm that the sequences found represent PPI between a PKC and its partner proteins.

The sequence is conserved in evolution

The sequence contains at least one charged amino acid

If the sequence is found in other proteins in the human genome, the sequence in these other proteins is not conserved in evolution.

Table 3.

Peptides derived from unique sequences in PKC (6–10 amino acids in length) exert isozyme-selective effects in a number of animal models of human diseases.

| Peptide (isozyme; Swissprot #; site) |

Peptide sequence |

Selectivity reference | Biological effects: examples of diseases and modelsreference |

|---|---|---|---|

| βC2–4 (human PKCβ; PO5771; amino acids 218–226) | SLNPEWNET | Affects all cPKCs253 | Inhibits cardiac hypertrophy in culture253 |

| δV1-1 (mouse PKCδ; P28867; amino acids 8–17) | SFNSYELGSL | Selectively inhibits PKCδ28 | Reduces infarct size when given at reperfusion, after myocardial infarction (MI)28,192; Inhibits breakdown of blood/brain barrier in hypertensive rats257 |

| εV1–2 (rat PKCε; P09216; amino acids 14–21) | EAVSLKPT | Selectively inhibits PKCε224 | Prevents transition to heart failure in hypertensive rats237; Inhibits pain sensation in an inflammatory pain model in rats44 |

| βIIV5-3 (human PKCβ; P05771-2; amino acids 612–617) | QEVIRN | Selectively inhibits PKCβII108,94 | Prevents cardiac dysfunction and death in a rat model of post-MI heart failure109; inhibits neo-angiogenesis in a xenograft model of prostate tumor in mice94 |

| γV5-3 (human PKCγ; P05129; amino acids 659–664) | RLVLAS | Selectively inhibits PKCγ44 | Prevents pain by blocking transmission in the cord44 |

| αV5-3 (human αPKC; P17252; amino acids 642–647) | QLVIAN | Selectively inhibits PKCα258 | Inhibits PKCα and inhibits tumor metastasis258 |

| ψε RACK (rat PKCε; P09216; amino acids 85–92) | HDAPIGYD | Selectively activates PKCε by inhibiting auto-inhibitory intra-molecular interaction256 | Induces protection from ischemic event when given prior to MI256,259 |

Much of the work on protein-protein interaction (PPI) focused on the C2 domain (initially termed V1 in the novel PKC isozymes)99,104–106. As indicated in Figure 1, C2 is the least conserved between the isozymes and even between the highly homologous members of the novel PKCs, δ and PKCθ, there is only 52% homology within this region. Yet the domain fold is similar: it is a beta sandwich of four strands, each with an alpha helix at one end and loops in between the strands (Fig. 1). Mochly-Rosen and colleagues showed that most of the protein-protein interactions map to unique sequences within the C2 domain and peptides corresponding to these sequences act as inhibitors of PPIs105,106. Other PPI sites are found in intervening regions between the common regions C1, C2, C3 and C4, including the V2, V3 and V5 regions and the region between C1a and C1b domains of PKC99. A peptide derived from the latter region in PKCε inhibits interaction with actin107. A peptide derived from the region between the C2 and C1 region of εPKC inhibits the interaction of this isozyme with HSP9092. A peptide derived from the V5 region selectively inhibits the interaction between PKCβII and RACK194,108 as well as the function of that isozyme, for example in cancer94 or in rat models of heart failure109. Recent studies in cancer have shown that PKCε is required for the growth of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and is anti-apoptotic; in vivo sustained treatment with the PKCε-specific inhibitory peptide, εV1–2 (see Table 3), slowed tumor growth in xenograft models110.

Post-translational modification of PKC - a future direction for drug development?

PKC can also be activated (in the presence or absence of the above described second-messengers) by a number of post-translational modifications including: tyrosine phosphorylation, oxidation of a cysteinerich domain within the C1 domain, nitrosylation, acetylation, binding of other metabolites (e.g., retinol or arachidonic acid) and proteolytic cleavage of the enzyme at the hinge region between the catalytic and the regulator halves of the enzyme (see review22). Although these alternative means of PKC activation may play a role in disease states, no pharmacological agents have been developed yet based on second-messenger-independent activation of PKC.

Clinical Applications of PKC regulators

Modulation of PKC activity presents an attractive target for clinical drug development for several reasons. 1) Isozyme-specific perturbations in PKC activity have been identified in a number of human disease states including congestive heart failure34, bipolar disorder111,112, and diabetes mellitus2,59. 2) PKC isozymes play an important role in critical biological processes such as cell proliferation and formation of vasculature that are important in tumor growth and metastasis113–116. 3) Animal studies demonstrate a role for individual isozymes in a particular disease and/or evidence of therapeutic effects when the isozymes are inhibited or activated62,117,118. 4) A number of pharmacologic agents that are efficacious in disease states have been shown to modulate activity of PKC, either directly or indirectly through a signaling cascade10,119.

Despite the apparent promise of PKC modulators in human disease, results in clinical trials have been mixed and largely negative. Clinical trials have been conducted for the treatment of cardiovascular disease, neuropsychiatric disorders, malignancies, transplantation, and diabetic complications including nephropathy, neuropathy, and retinopathy. This section will focus on clinical efficacy studies for both novel compounds and previously approved drugs (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of clinical trials with PKC regulators

| Indication | Drug Reference | Proposed mechanism |

Outcome |

Company Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Congestive heart failure | Flosequinan156,157 | Non-selective ↓PKC |

Increased hospitalizations and mortality required early study termination | Withdrawn from clinical use |

| Coronary bypass grafting (preconditioning) | Volatile anesthetics161–165 | ↑PKCε | Reduction in troponin I levels, need for inotropic support, and prolonged hospitalization (>7days) | Sevoflurane and desflurane compared to propofol in moderate size studies. |

| Adenosine166–168 | ↑PKCε | Reduction in composite AMI, mortality, need for pressors postoperatively. | Requires validation in larger study | |

| Acadesine169,170,2 30 | ↑PKCε ↑AMPK* |

No reduction in death, AMI, or stroke | Reduced two year mortality in the small group of patients who had a post-operative AMI. | |

| Acute myocardial infarction Salvage | Adenosine171 | ↑PKCε | No reduction in composite endpoint of death and CHF | Reduced infarct size from 27% to 11% when given at 70 mcg/kg/min |

| Delcasertib172,173 | ↓PKCδ | No benefit when given intravenously | Positive biomarker trend when given to patients with TIMI 0/1 flow | |

| Bipolar Mania | Tamoxifen183–186 | Nonselective ↓PKC (at high dose) ER# inhibitor |

Several small studies show significant benefit in acute mania | High dose tamoxifen (80 mg/day) increases risk of thrombo-embolism, stroke, and uterine cancer |

| Oncology | Bryostatin121–134 | Nonselective ↑PKC |

Minimal to no benefit against a number of cancers. | Causes severe myalgias in >50% of patients. No ongoing studies. |

| Aprinocarsen135– 141 | ↓PKCα | Limited to no benefit against a number of cancers. | Development discontinued | |

| Enzastaurin142–148 | ↓PKCβ | Very rare to no objective responses against a number of cancers | Ongoing studies in brain malignancies | |

| Tamoxifen149–151 | Nonselective ↓PKC (at high dose) ER# inhibitor |

Limited to no benefit in malignant gliomas and hormone refractory prostate cancer | High dose tamoxifen (80 mg/day) increases risk of thromoembolism, stroke, and uterine cancer | |

| Midostaurin152,153 | Nonselective ↓PKC ↓FMS-like Tyrosine kinase 3 |

No effect in metastatic malignant melanoma. Decreased peripheral blasts in leukemia. | Leukemia trials being conducted. | |

| UCN-01154,155,231 | Nonselective ↓PKC ↓Chk1 |

No response in advanced renal cell cancer or ovarian cancer | Studied in combination with topotecan in ovarian cancer study | |

| Diabetic Retinopathy | Ruboxistaurin158, 174–177 | ↓PKCβ | Reduced sustained moderate vision loss in large studies | Under review by FDA for diabetic retinopathy |

| Diabetic Nephropathy | Ruboxistaurin179, 180 | ↓PKCβ | Failed to improve kidney outcomes | Studied as secondary outcome in large retinopathy trials |

| Diabetic Neuropathy | Ruboxistaurin181, 182 | ↓PKCβ | Mild decrease in symptoms | Small, short-term studies. Requires validation in larger study |

| Transplant Rejection | Sotrastaurin187,188 | Nonselective ↓PKC |

Marked increase in rejection | Rejection occurred when used in combination with mycophenolate |

AMP-activated protein kinase

estrogen receptor

Oncology Trials

Although a number of clinical trials have been conducted in cancer with drugs thought to modulate PKC activity, tumor responses have been infrequent and modest at best. Only six agents have been studied in efficacy trials. Bryostatin 1, a macrolide lactone and a non-selective activator of both classical and novel PKC isozymes, entered clinical study in 1993 after promising results in cancer xenograft models120. The drug has since been tested in multiple phase 2 studies with largely disappointing results. Bryostatin 1 showed minimal or no anti-tumor activity when tested in patients with advanced melanoma, sarcoma, head and neck cancer, multiple myeloma, colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and pancreatic cancer121–130. Modest effects were observed in advanced renal cell cancer and gastric/esophageal cancer, but the overall response was disappointing and more than half of the patients experienced severe myalgias, necessitating early termination of one study131–134. There are currently no open trials of bryostatin 1 on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Aprinocarsen, an anti-sense oligonucleotide that targets PKCα mRNA, has also been studied clinically in a number of oncology trials. In phase 2 studies, aprinocarsen failed to show activity as a single agent against advanced colorectal, ovarian, and hormone refractory prostate cancer135–138 and showed only modest activity against relapsed, low-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma139. In two phase 3 non-small cell lung cancer studies, aprinocarsen failed to improve tumor response rate or survival when added to combination chemotherapy, but additional toxicities including thrombocytopenia and venous thromboembolism were observed140,141. Further clinical development of aprinocarsen has been discontinued.

Enzastaurin is an orally available small molecule selective inhibitor of PKCβ that targets the ATP-binding site (Table 2). Single agent phase 2 studies showed inadequate efficacy in patients with advanced presentation of the following malignancies: large B cell lymphoma, mantle cell lymphomas, non-small cell lung cancer, high grade gliomas, recurrent ovarian and primary peritoneal malignancies, and asymptomatic chemotherapy-naïve colorectal cancer142–147. In a larger phase 2 study, enzastaurin did not add to the anti-tumor activity of pemetrexed and carboplatin in patients with stage IIIb or stage IV non-small cell lung cancer148. Clinical studies are ongoing to assess the addition of enzastaurin to combination chemotherapy for advanced brain malignancies (http://clinicaltrials.gov).

Other PKC modulators have undergone limited study in oncologic indications. High dose tamoxifen (a non-selective PKC inhibitor at high dose) provided negligible benefit to patients with malignant gliomas and hormone refractory prostate cancer149–151. Midostaurin, an orally available multi-targeted kinase inhibitor had no effect against malignant melanoma in a small study152. Midostaurin did show ≥ 50% reduction in blast counts in a substantial proportion of patients with acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome and is being assessed in clinical trials for hematologic malignancies, but its effect may be mediated by FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3, which is mutated and constitutively overactive in up to 30% of patients with myeloid leukemias153. UCN-01 (7-hydroxystaurosporin), a non-selective kinase inhibitor, was ineffective against both progressive renal and ovarian cancers154,155.

Cardiovascular Trials

Flosequinan, a non-selective inhibitor of inositol-triphosphate and PKC, was compared to placebo in 193 patients with symptomatic heart failure. After 12 weeks, patients in the flosequinan group showed statistically significant improvements in maximal treadmill exercise time (96 vs. 47 seconds; p=0.022), increase in maximal oxygen consumption (1.7 vs. 0.6 ml/kg per minute; p = 0.05), and symptom improvement (55% vs. 36%, p=0.018)156. In a larger subsequent study, the Data Monitoring Committee stopped the trial prematurely after an interim analysis revealed increased deaths and hospitalizations in the active arm, and flosequinan was removed from the market157. Recently ruboxistaurin, a PKCβ inhibitor that was well-tolerated in large clinical studies of diabetic patients158, was shown to improve cardiac function in a porcine heart failure model159 and perhaps warrants clinical study in heart failure.

Volatile anesthetics such as isoflurane, sevoflurane, and desflurane are known to activate PKCε119, an essential step in ischemic preconditioning of cardiomyocytes4,160. Clinical trials comparing the use of these anesthetics to intravenous anesthetics prior to coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) showed statistically significant reductions in peak troponin I levels, need for postoperative inotropic support, and need for length of stay exceeding seven days161–164. In one study, a volatile anesthetic reduced one-year mortality165.

Adenosine, a purine nucleoside, has been shown to activate both PKCδ and PKCε. Studies of intravenous adenosine prior to and during heart surgery have been modest in both size and effect166–168. Acadesine, a drug thought to increase adenosine levels in ischemic tissues, was compared with placebo in 2,698 patients undergoing CABG. The study missed its primary endpoint of reduction of myocardial infarction and secondary endpoint of a composite of cardiac death, myocardial infarction, or stroke at postoperative day 4169. In the small subset of patients experiencing post-operative myocardial infarction, two-year mortality was reduced from 27.8% to 6.5% (p=0.006)169. A more recent study of acadesine in CABG patients was stopped prematurely for futility after failing to show an effect on the composite outcome of 28 day mortality, nonfatal stroke, and severe left ventricular dysfunction (5.1% acadesine vs. 5% placebo)170.

Adenosine was also studied as a myocardial salvage agent during acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in a large randomized trial. Although there was no difference in the composite clinical endpoint of death and heart failure, infarct size was significantly reduced in the high-dose group compared to placebo (11% vs. 27% of the left ventricle; p=0.023)171. Delcasertib (δV1-1), a peptide inhibitor of PKCδ rationally designed by the Mochly-Rosen lab as an effective inhibitor when given at reperfusion28, showed encouraging trends toward reduced infarct size and accelerated resolution of ST elevation when administered by intracoronary injection to AMI patients with an occluded coronary artery on initial angiogram172. A larger AMI study of intravenous delcasertib administered prior to angiography in patients with and without reperfusion at the time of drug treatment failed to show a statistically significant benefit in the primary endpoint of infarct size, as assessed by CK-MB AUC (area under the curve). Subgroup analysis revealed a trend towards reduced infarct size (∼14%) in patients with anterior STEMI and TIMI 0/1 flow on initial angiography173., but this signal was not considered adequate to warrant further development by the sponsor.

Trials for Diabetic Complications

Ruboxistaurin, an orally available PKCβ inhibitor, has been extensively studied in diabetic retinopathy and has been well-tolerated158. The PKC-DRS, a randomized, double-blinded trial, compared three doses (8, 16, and 32 mg/day) of ruboxistaurin and placebo in 252 patients with severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy over 36 months. There was no effect on the study’s primary endpoint of progression of diabetic retinopathy. The secondary endpoint of sustained moderate visual loss (SMVL), however, was reduced from 25% in the placebo group to 10% in the 32 mg/day group in subjects who had definite diabetic macular edema at baseline174. The PKC-DRS2 was a 36 month, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study in which 685 patients with nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy were randomized to receive either 32 mg of ruboxistaurin or placebo once daily. The primary endpoint of SMVL occurred in 9.1% of placebo-treated patients and 5.5% of ruboxistaurin-treated patients (p = 0.034). Initiation of laser treatment for macular edema was 26% less frequent in the active treatment group (p = 0.008)175. In response to an FDA request for data on longer-term outcomes, a two-year open-label extension study of PKC-DMRS2 was conducted in 203 subjects who had been off-study for approximately one year at the time of re-enrollment. Thus, the study compared outcomes in 100 patients who received ruboxistaurin for the last two of the six years since initial enrollment and 103 patients who received ruboxistaurin for five of the six total years. The primary endpoint of SMVL occurred in 26% of the placebo-ruboxistaurin group and 8% of ruboxistaurin only group by the end of the open label extension (p < 0.001)176. Ruboxistaurin is currently undergoing regulatory review by the FDA for diabetic retinopathy based upon these data. In a diabetic macular edema study, ruboxistaurin failed to show improvement in a composite endpoint of progression to sight-threatening macular edema or necessity for focal/grid photocoagulation therapy177. Oral midostaurin was shown to reduce diabetic macular edema but further development was abandoned due to intolerable gastrointestinal side effects178.

Clinical trials were also conducted to study the effect of ruboxistaurin in delaying diabetic nephropathy. One study compared 32 mg/day of ruboxistaurin versus placebo over one year in 123 diabetic subjects with persistent albuminuria. Although the albumin to creatinine ratio decreased significantly in the active drug group and estimated glomerular filtration rate decreased significantly in the placebo group, the intergroup differences were not statistically significant179,180. A subsequent analysis was performed of the 1,157 patients enrolled in the three ruboxistaurin diabetic retinopathy studies. There was no difference in kidney outcomes in patients receiving placebo versus ruboxistaurin180. Two studies conducted in patients with diabetic neuropathy showed evidence of reduction in neuropathic symptoms over the six and twelve month treatment periods181,182. Longer-term studies are warranted to better define the role of ruboxistaurin in reducing progression of neuropathy.

Bipolar Disorder Trials

Tamoxifen citrate, an estrogen receptor modulator commonly used to treat breast cancer, readily crosses the blood-brain barrier and non-selectively inhibits PKC at doses approximately four-fold higher than the standard anti-estrogen dose62,151. Several small clinical trials have been conducted over the past decade to assess the efficacy of high dose (40–80 mg daily) tamoxifen in acute mania. All studies showed substantial improvement in mania scores compared to placebo183–186. Patients taking standard-dose tamoxifen have an increased risk of venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, stroke and uterine cancer and these safety concerns will be more pronounced at the higher doses used for mania. A PKC inhibitor that crosses the blood-brain barrier and has an improved safety profile would be a welcome addition for treatment of bipolar disorder.

Transplantation Clinical Trials

Sotrastaurin is a non-selective PKC inhibitor with activity against both conventional and novel isozymes. Because it inhibits PKCθ, a critical isozyme for T cell activation, sotrastaurin is being developed as an immunosuppressive for organ transplantation187. In two clinical studies of allograft renal transplantation, immunosuppressive regimens including sotrastaurin and mycophenolic acid were compared to standard of care regimens. In each case, the groups receiving sotrastaurin had dramatic increases in acute rejection187,188.

Challenges in Clinical Applications of PKC Modulators

Thus far, the clinical trial results of PKC modulators have been disappointing, largely due to inadequate therapeutic effect and/or unanticipated adverse reactions. Among the many agents tested to date, only ruboxistaurin achieved an adequate therapeutic signal to warrant an FDA review for potential market approval for use in non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy. A number of scientific challenges have contributed to the slow rate of progress in the clinical application of PKC modulators and to failure of related clinical trials:

Inadequate understanding of disease-specific pathophysiology - Much of the basic research leading to clinical studies has failed to identify the isozyme(s) of interest or the specific downstream signaling event that leads to the pathology. For example, many PKC isozymes have been implicated in cancer, and some PKC isozymes may be critical for select types of the disease. Work with mice bearing human tumors may down play the interaction between the tumor and the normal tissue (e.g., endothelial cells) and therefore often only a single isozyme in each tumor type is implicated in the pathology. A more robust understanding of the underlying biology and comparison of pathways identified in human specimens is essential for therapeutic progress in this field.

Inadequate preclinical studies - Animal models that examine the role of PKC in chronic diseases are usually very short term. For example, pressure overload by aortic constriction is often used to induce heart failure in rodents. This model mimics pressure overload induced by hypertension, which slowly leads to heart failure in humans. However, aortic constriction induces pressure overload very abruptly and therefore may implicate molecular processes in heart failure that do not occur in natural progression of the disease in humans. In addition, idealized controlled experiments conducted on inbred animals do not capture the full range of heterogeneous conditions encountered in clinical practice. Patients vary in age, underlying health, baseline medications, diet, and severity and cause of the disease of interest. Any of these factors might result in decreased efficacy or increased toxicity of the study drug. The route of administration is often changed between animal efficacy studies and clinical trials. To the extent possible, these potential confounding factors must be replicated in the animal studies. Species differences in PKC expression must also be taken into consideration when conducting animal efficacy studies. Another factor that needs to be considered is the lack of reproducibility of preclinical findings: Unfortunately, many academic studies include data in a single animal model, use too few animals per group, use inappropriate statistical tools, are carried out in un-blinded fashion and/or report only positive data. A recent publication in Nature reported that only 11% of 53 papers reporting preclinical data in cancer research were independently confirmed by Amgen investigators; the rest of the studies could not be confirmed even when working with the original authors189. Numerous reasons can be provided to explain the Amgen findings, and this is not the platform to discuss them. Nevertheless, lack of incentive (and platform) to publish confirming or negative data in a second species may contribute to the problem.

Lack of selectivity and unacceptable on-target and off-target effects - As discussed above, many PKC inhibitors also affect other protein kinases72,190 and, therefore, are less suitable as therapeutics. Second, multiple PKC isozymes are expressed in all cell types throughout the body and play critical roles in normal physiology. As a result, systemic inhibition of an isozyme (e.g., PKCβ) that contributes to a disease process, such as the disordered angiogenesis of proliferative macular degeneration, may result in undesired on-target side effects, such as delayed wound healing. Further, each PKC isozyme regulates a number of intracellular signaling events, each leading to a specific phenotypic response. Therefore, even an isozyme-selective drug may elicit responses that are both positive and negative in the pathophysiology of a particular disease. To address this problem, the Mochly-Rosen lab is developing separation-of-function inhibitors (SoF) (Fig. 4d). SoF inhibitors are peptides that are designed to selectively inhibit the phosphorylation of one particular substrate of an individual PKC isozyme, without affecting phosphorylation of its other substrates. Such peptide inhibitors were developed using the same rational as summarized in Box 3 (e.g., to selectively inhibit pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase phosphorylation by PKCδ47; submitted). Peptide regulators that affect the translocation to a particular site, without affecting the translocation and the resulting activities in other sites can also be developed e.g., the peptide that selectively enhances PKCε translocation into the mitochondria to provide cardioprotection92. It remains to be determined whether such separation-of-function inhibitors of individual PKC isozymes will be useful therapeutics. In addition, some labs have taken an in silico or systems biology approach to address the selectivity of PKC inhibitors (e.g., investigators at Lilly took at chemical proteomics approach to address bisindolmaleimide selectivity191).

The drug does not reach its target in adequate concentration - PKC modulators must be delivered intracellularly to their target. Optimal clinical dosing regimens are typically extrapolated from efficacious blood concentrations in animal studies. But blood levels may not correlate in either magnitude or timing to intracellular drug concentrations and the target tissue. This is particularly problematic with peptide and oligo-nucleotide therapies, which are largely impermeable to cell membranes and often require a carrier peptide to allow intracellular access.

Lack of blood biomarkers - As yet, there are no PKC-specific biomarkers that would indicate adequacy of dosing or predict phenotypic outcome. As a result, expensive trials measuring clinical outcomes are the only way to identify the optimal dosing regimen. This adds substantially to development costs and greatly increases the probability of failure to show efficacy.

Confounders in clinical practice - When designing clinical trials, researchers must consider and control for additional factors that might reduce a drug’s clinical effect. For example, a selective PKCε activator intended to reduce cardiac ischemic damage during CABG will be less likely to show efficacy versus placebo if volatile anesthetics are also routinely administered, since they also activate PKCε.

Inability to obtain and analyze data from failed clinical trials - With the establishment of registration of ongoing trials in clinicaltrials.gov, there was hope that all patient-related data will be available for analysis regardless of the trials’ outcome. However, whereas data on positive trials are provided in a relatively timely fashion, there is a long lag in or lack of reporting on failed trials. This may be due to reduced priority for the sponsors to publish and/or a disincentive to improve drug development in competing companies. Since the majority of the studies are conducted with academic principle investigators, it is imperative that this work will be published and that a forum for publishing these important data in high profile journals will be available. Analysis of such failed trials will provide critical information on how to improve subsequent trials.

Conclusion

Given PKC’s critical roles in both normal physiology and disease, this family of kinases remains an enticing target for drug development. As our knowledge of PKC biology deepens, it appears that even selectivity at the isozyme level may be insufficient for a drug to have optimal efficacy and minimal unintended “on-target” adverse effects. Biomarkers that are specific for PKC activity would greatly enhance our ability to monitor the pharmacodynamic activity of new PKC modulators. As we continue to unravel the biology of PKC, future success in developing drugs for PKC-mediated diseases will require that we thoughtfully combine cutting-edge basic research with more robust and efficient drug development practices.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Adrienne Gordon, Dr. Antonio Giachetti and Dr. Eric Gross for their critical comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the US National Institutes of Health grant, HL52141 (to D.M-R).

Competing interest statements:

D.M-R is the founder of KAI Pharmaceuticals and K.V.G and K.D. are past employees of KAI Pharmaceuticals.

However, none of the research in the D.M-R. lab is in collaboration with or supported by the company. Further, the company was recently acquired by Amgen and none of the authors are involved in KAI-related research.

References

- 1.Castagna M, et al. Direct activation of calcium-activated, phospholipid-dependent protein-kinase by tumor-promoting phorbo esters. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:7847–7851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geraldes P, King GL. Activation of protein kinase C isoforms and its impact on diabetic complications. Circ Res. 2010;106:1319–1331. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.217117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toton E, Ignatowicz E, Skrzeczkowska K, Rybczynska M. Protein kinase Cepsilon as a cancer marker and target for anticancer therapy. Pharmacol Rep. 2011;63:19–29. doi: 10.1016/s1734-1140(11)70395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Inagaki K, Churchill E, Mochly-Rosen D. Epsilon protein kinase C as a potential therapeutic target for the ischemic heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:222–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreira JC, Brum PC, Mochly-Rosen D. BetaIIPKC and epsilonPKC isozymes as potential pharmacological targets in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;51:479–484. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zanin-Zhorov A, Dustin ML, Blazar BR. PKC-theta function at the immunological synapse: prospects for therapeutic targeting. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burguillos MA, et al. Caspase signalling controls microglia activation and neurotoxicity. Nature. 2011;472:319–324. doi: 10.1038/nature09788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang D, Anantharam V, Kanthasamy A, Kanthasamy AG. Neuroprotective effect of protein kinase C delta inhibitor rottlerin in cell culture and animal models of Parkinson's disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:913–922. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.124669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrido JL, Godoy JA, Alvarez A, Bronfman M, Inestrosa NC. Protein kinase C inhibits amyloid beta peptide neurotoxicity by acting on members of the Wnt pathway. FASEB J. 2002;16:1982–1984. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0327fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manji HK, Lenox RH. The nature of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(Supp 13):42–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zarate CA, Manji HK. Protein kinase C inhibitors: rationale for use and potential in the treatment of bipolar disorder. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:569–582. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923070-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maioli E, Valacchi G. Rottlerin: bases for a possible usage in psoriasis. Curr Drug Metab. 2010;11:425–430. doi: 10.2174/138920010791526097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. The protein kinase complement of the human genome. Science. 2002;298:1912–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takai Y, Kishimoto A, Inoue M, Nishizuka Y. Studies on a cyclic nucleotide-independent protein kinase and its proenzyme in mammalian tissues. 1. purfication and characterization of an active enzyme from bovine cerebellum. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:7603–7609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takai Y, Kishimoto A, Kikkawa U, Mori T, Nishizuka Y. Unsaturated diacylglycerol as a pssible messenger for the activation of calcium-activated, phospholipid dependent protein-kinase system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1979;91:1218–1224. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(79)91197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]