Abstract

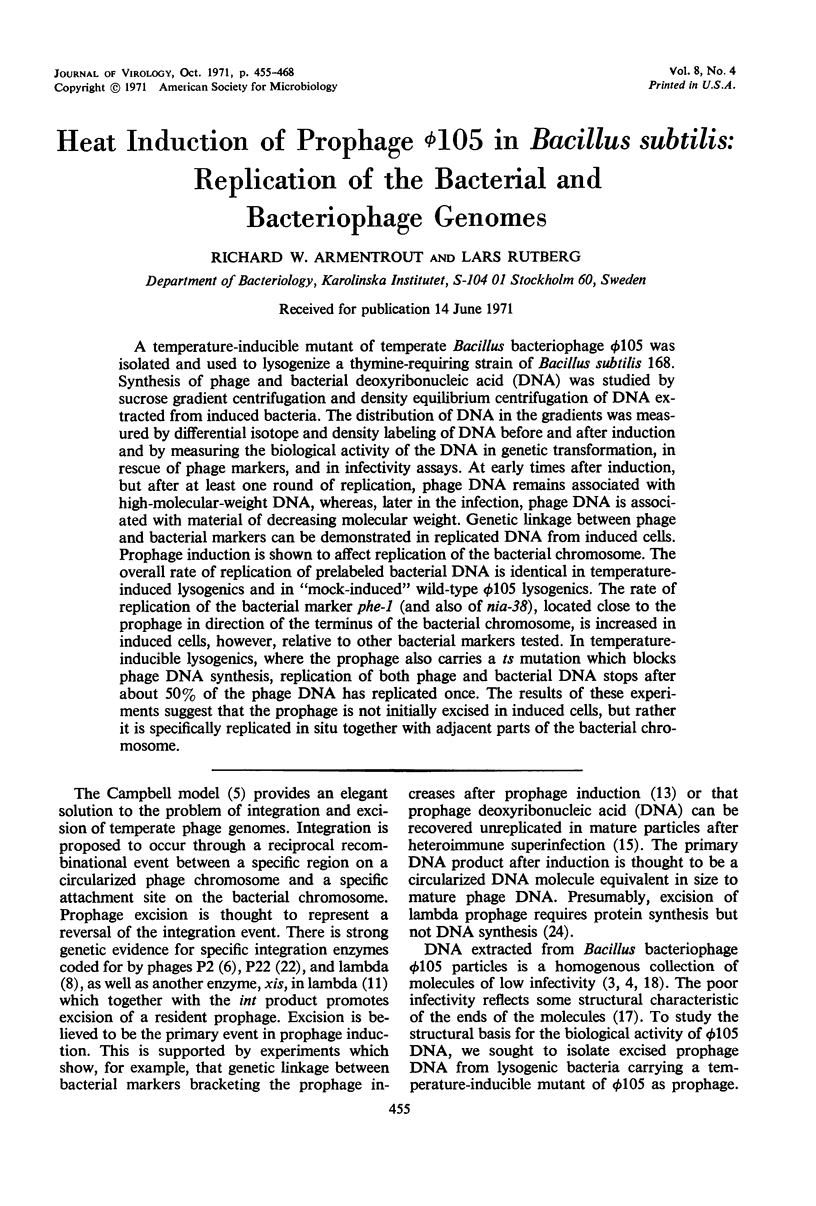

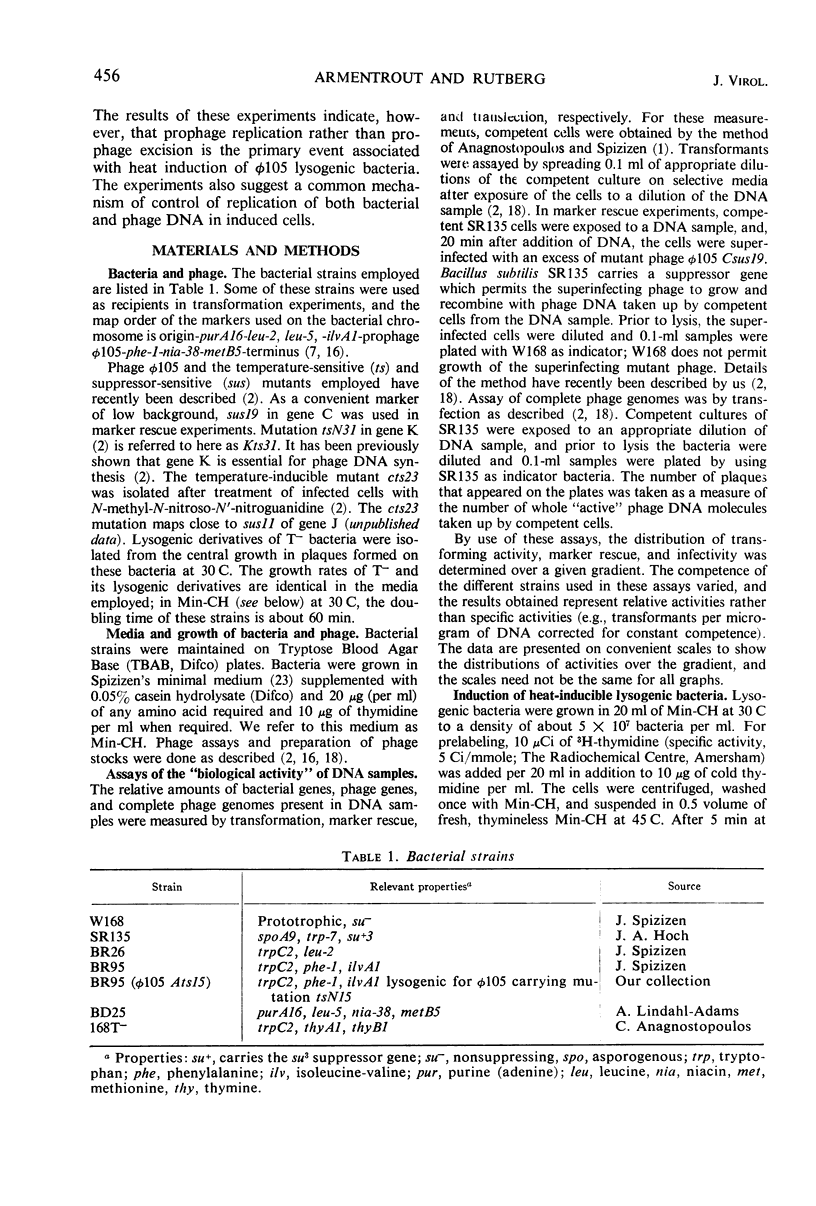

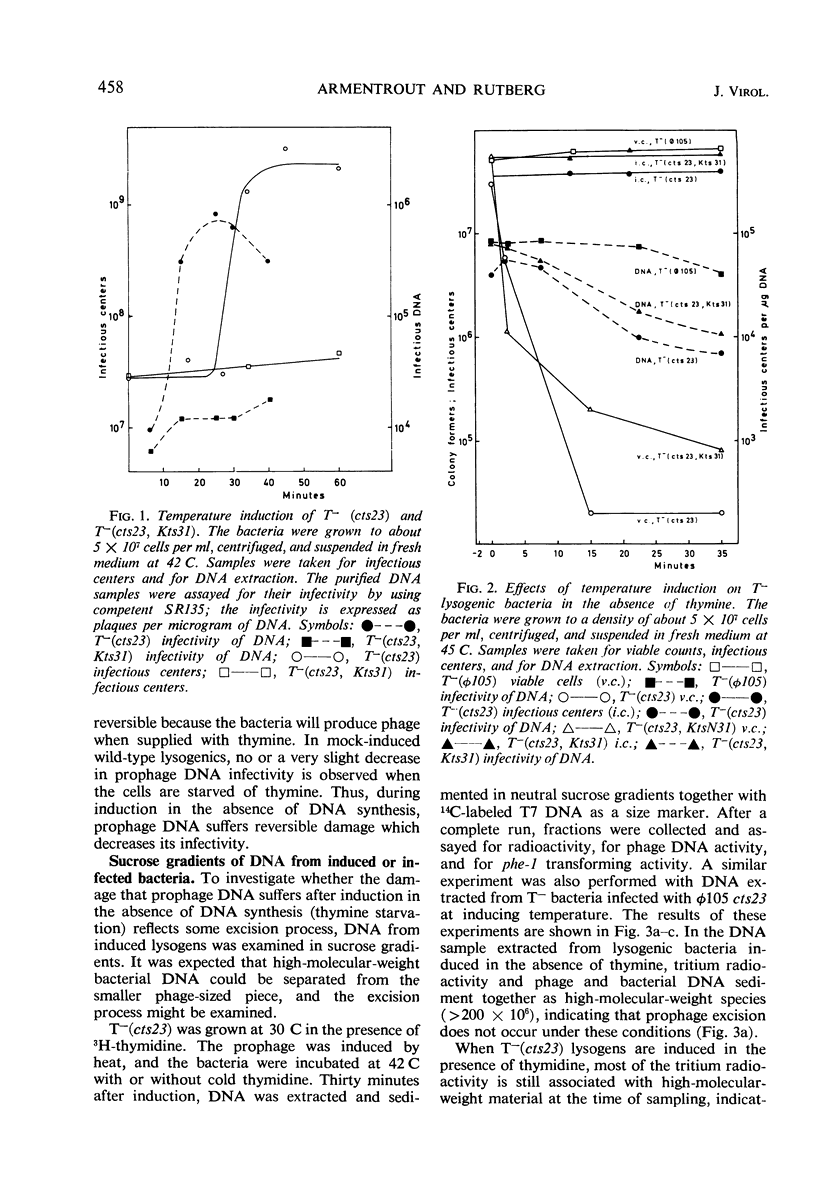

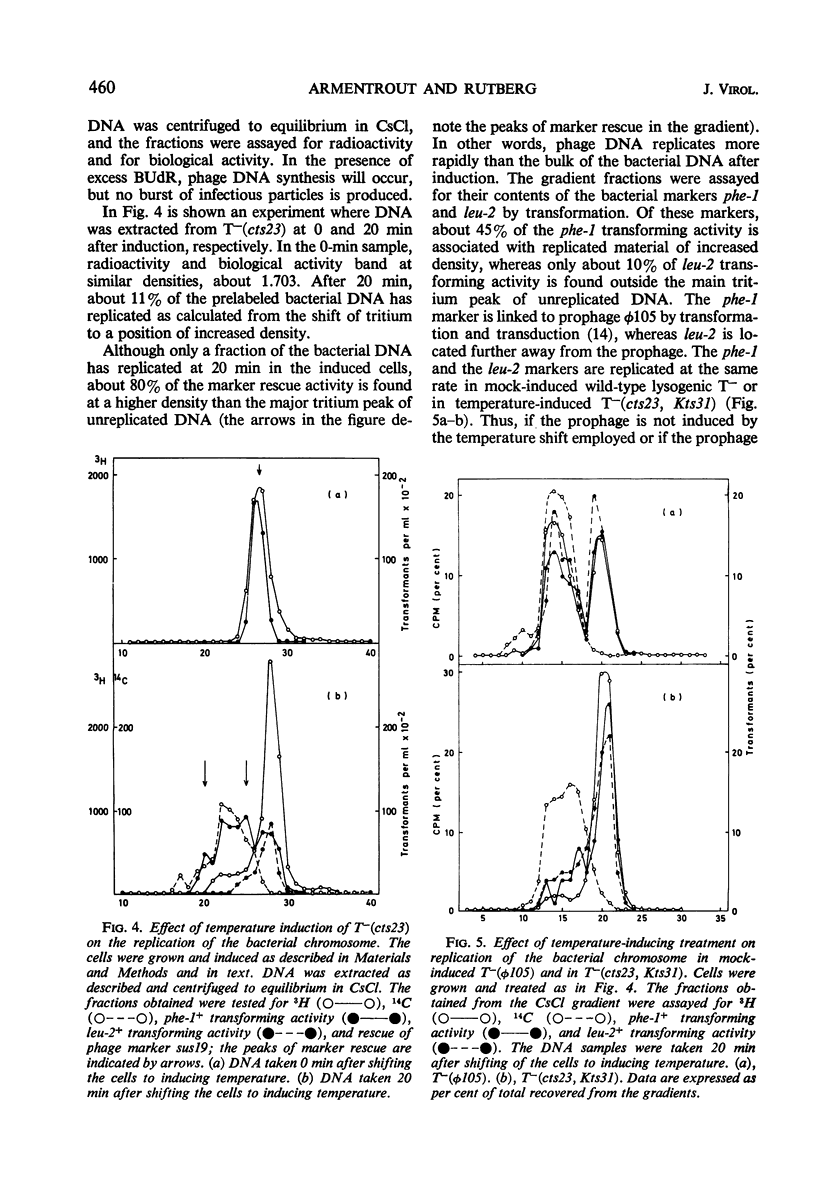

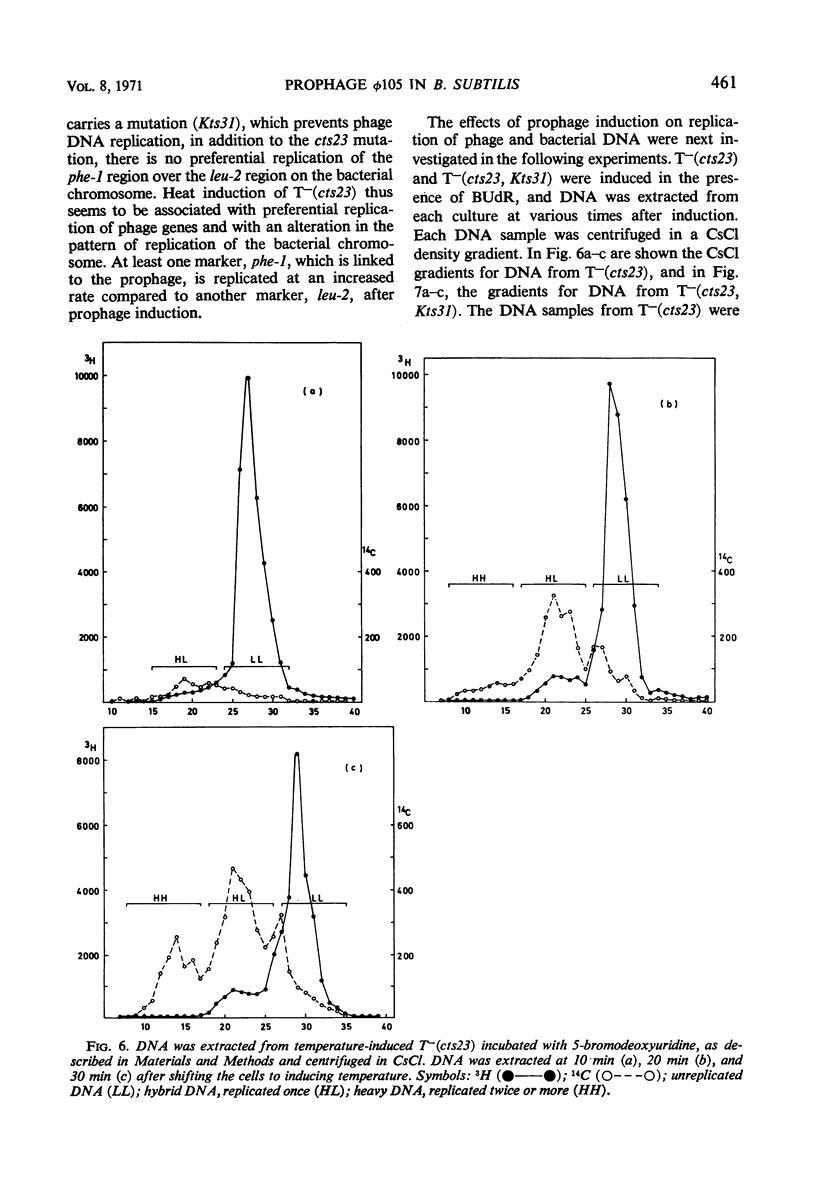

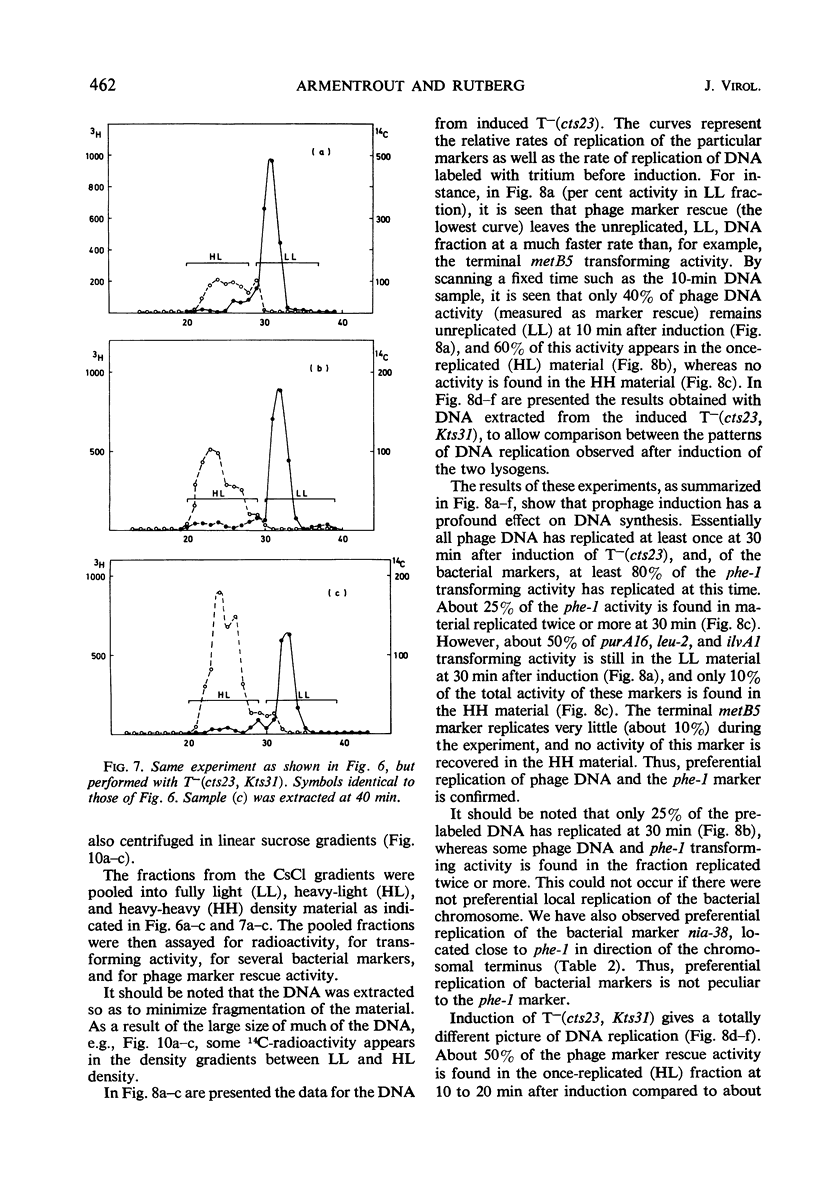

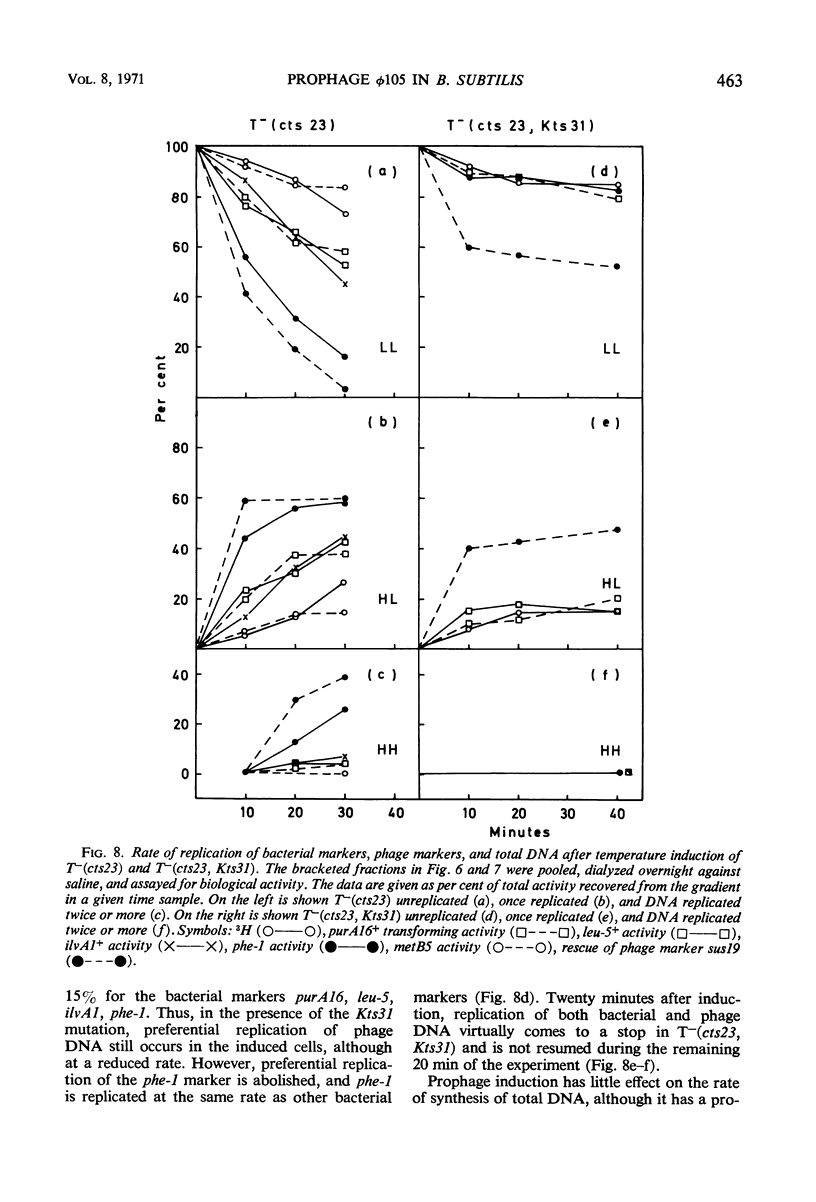

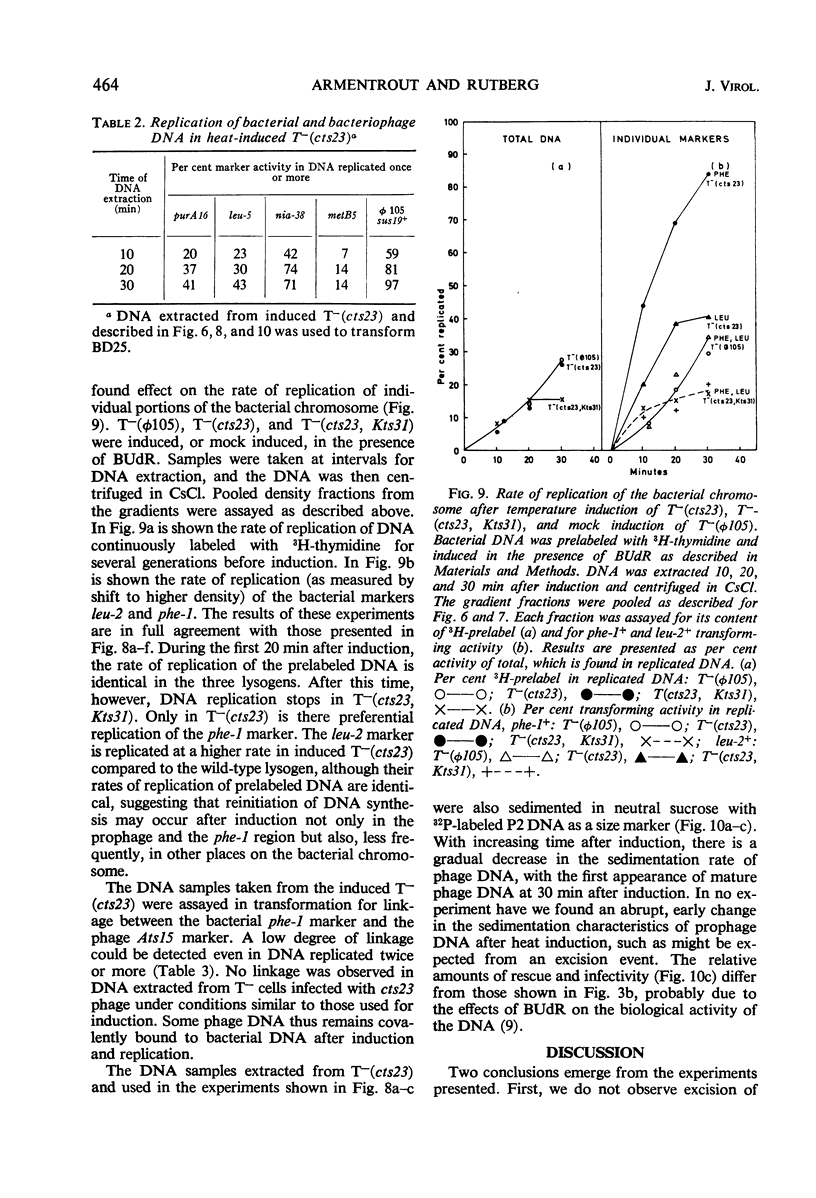

A temperature-inducible mutant of temperate Bacillus bacteriophage φ105 was isolated and used to lysogenize a thymine-requiring strain of Bacillus subtilis 168. Synthesis of phage and bacterial deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) was studied by sucrose gradient centrifugation and density equilibrium centrifugation of DNA extracted from induced bacteria. The distribution of DNA in the gradients was measured by differential isotope and density labeling of DNA before and after induction and by measuring the biological activity of the DNA in genetic transformation, in rescue of phage markers, and in infectivity assays. At early times after induction, but after at least one round of replication, phage DNA remains associated with high-molecular-weight DNA, whereas, later in the infection, phage DNA is associated with material of decreasing molecular weight. Genetic linkage between phage and bacterial markers can be demonstrated in replicated DNA from induced cells. Prophage induction is shown to affect replication of the bacterial chromosome. The overall rate of replication of prelabeled bacterial DNA is identical in temperature-induced lysogenics and in “mock-induced” wild-type φ105 lysogenics. The rate of replication of the bacterial marker phe-1 (and also of nia-38), located close to the prophage in direction of the terminus of the bacterial chromosome, is increased in induced cells, however, relative to other bacterial markers tested. In temperature-inducible lysogenics, where the prophage also carries a ts mutation which blocks phage DNA synthesis, replication of both phage and bacterial DNA stops after about 50% of the phage DNA has replicated once. The results of these experiments suggest that the prophage is not initially excised in induced cells, but rather it is specifically replicated in situ together with adjacent parts of the bacterial chromosome.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anagnostopoulos C., Spizizen J. REQUIREMENTS FOR TRANSFORMATION IN BACILLUS SUBTILIS. J Bacteriol. 1961 May;81(5):741–746. doi: 10.1128/jb.81.5.741-746.1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armentrout R. W., Rutberg L. Mapping of prophage and mature deoxyribonucleic acid from temperate Bacillus bacteriophage phi 105 by marker rescue. J Virol. 1970 Dec;6(6):760–767. doi: 10.1128/jvi.6.6.760-767.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armentrout R. W., Skoog L., Rutberg L. Structure and biological activity of deoxyribonucleic acid from Bacillus bacteriophage phi 105: effects of Escherichia coli exonucleases. J Virol. 1971 Mar;7(3):359–371. doi: 10.1128/jvi.7.3.359-371.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birdsell D. C., Hathaway G. M., Rutberg L. Characterization of Temperate Bacillus Bacteriophage phi105. J Virol. 1969 Sep;4(3):264–270. doi: 10.1128/jvi.4.3.264-270.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubnau D., Goldthwaite C., Smith I., Marmur J. Genetic mapping in Bacillus subtilis. J Mol Biol. 1967 Jul 14;27(1):163–185. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90358-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingery R., Echols H. Mutants of bacteriophage lambda unable to integrate into the host chromosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1967 Oct;58(4):1507–1514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.4.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas M., Yoshikawa H. Defective bacteriophage PBSH in Bacillus subtilis. II. Intracellular development of the induced prophage. J Virol. 1969 Feb;3(2):248–260. doi: 10.1128/jvi.3.2.248-260.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imae Y., Fukasawa T. Regional replication of the bacterial chromosome induced by derepression of prophage lambda. J Mol Biol. 1970 Dec 28;54(3):585–597. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90129-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser A. D., Masuda T. Evidence for a prophage excision gene in lambda. J Mol Biol. 1970 Feb 14;47(3):557–564. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(70)90322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimune Y. Prophage excision: on the status of host chromosome after induction. Virology. 1970 Jul;41(3):541–548. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(70)90174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PTASHNE M. THE DETACHMENT AND MATURATION OF CONSERVED LAMBDA PROPHAGE DNA. J Mol Biol. 1965 Jan;11:90–96. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(65)80174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson A. M., Rutberg L. Linked transformation of bacterial and prophage markers in Bacillus subtilis 168 lysogenic for bacteriophage phi 105. J Bacteriol. 1969 Jun;98(3):874–877. doi: 10.1128/jb.98.3.874-877.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutberg L., Armentrout R. W. Low-frequency rescue of a genetic marker in deoxyribonucleic acid from Bacillus bacteriophage phi 105 by superinfecting bacteriophage. J Virol. 1970 Dec;6(6):768–771. doi: 10.1128/jvi.6.6.768-771.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutberg L., Hoch J. A., Spizizen J. Mechanism of transfection with deoxyribonucleic acid from the temperate Bacillus bacteriophage phi-105. J Virol. 1969 Jul;4(1):50–57. doi: 10.1128/jvi.4.1.50-57.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutberg L. Mapping of a temperate bacteriophage active on Bacillus subtilis. J Virol. 1969 Jan;3(1):38–44. doi: 10.1128/jvi.3.1.38-44.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutberg L., Rutberg B. Characterization of infectious deoxyribonucleic acid from temperature Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage phi105. J Virol. 1970 May;5(5):604–608. doi: 10.1128/jvi.5.5.604-608.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzman L. A., Weissbach A. Formation of intermediates in the replication of phage lambda DNA. J Mol Biol. 1967 Aug 28;28(1):53–70. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(67)80077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. O. Defective phage formation by lysogens of integration deficient phage P22 mutants. Virology. 1968 Feb;34(2):203–223. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(68)90231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. O., Levine M. A phage P22 gene controlling integration of prophage. Virology. 1967 Feb;31(2):207–216. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(67)90164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spizizen J. TRANSFORMATION OF BIOCHEMICALLY DEFICIENT STRAINS OF BACILLUS SUBTILIS BY DEOXYRIBONUCLEATE. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1958 Oct 15;44(10):1072–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.44.10.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg R. A., Gallant J. A. Dual function of the lambda prophage repressor. J Mol Biol. 1967 May 14;25(3):537–544. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90204-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young E. T., 2nd, Sinsheimer R. L. Vegetative bacteriophage lambda-DNA. II. Physical characterization and replication. J Mol Biol. 1967 Nov 28;30(1):165–200. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90251-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]