Abstract

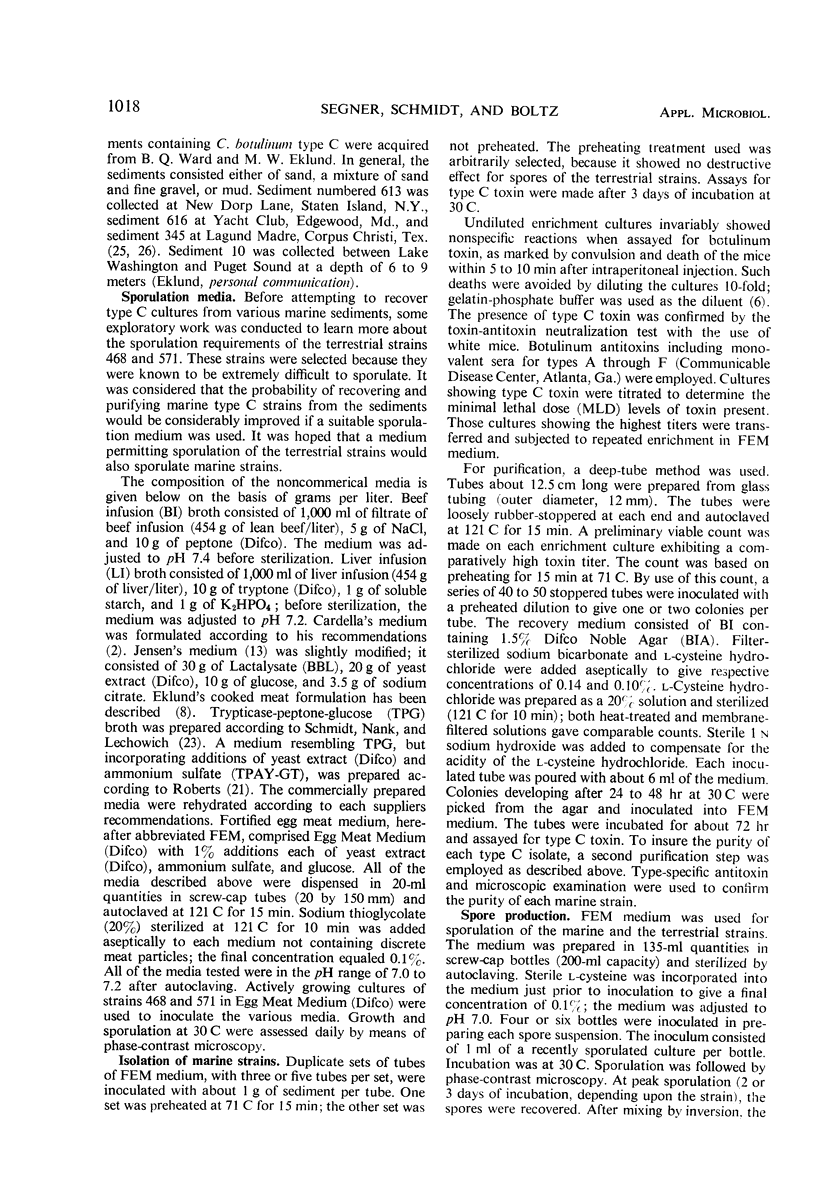

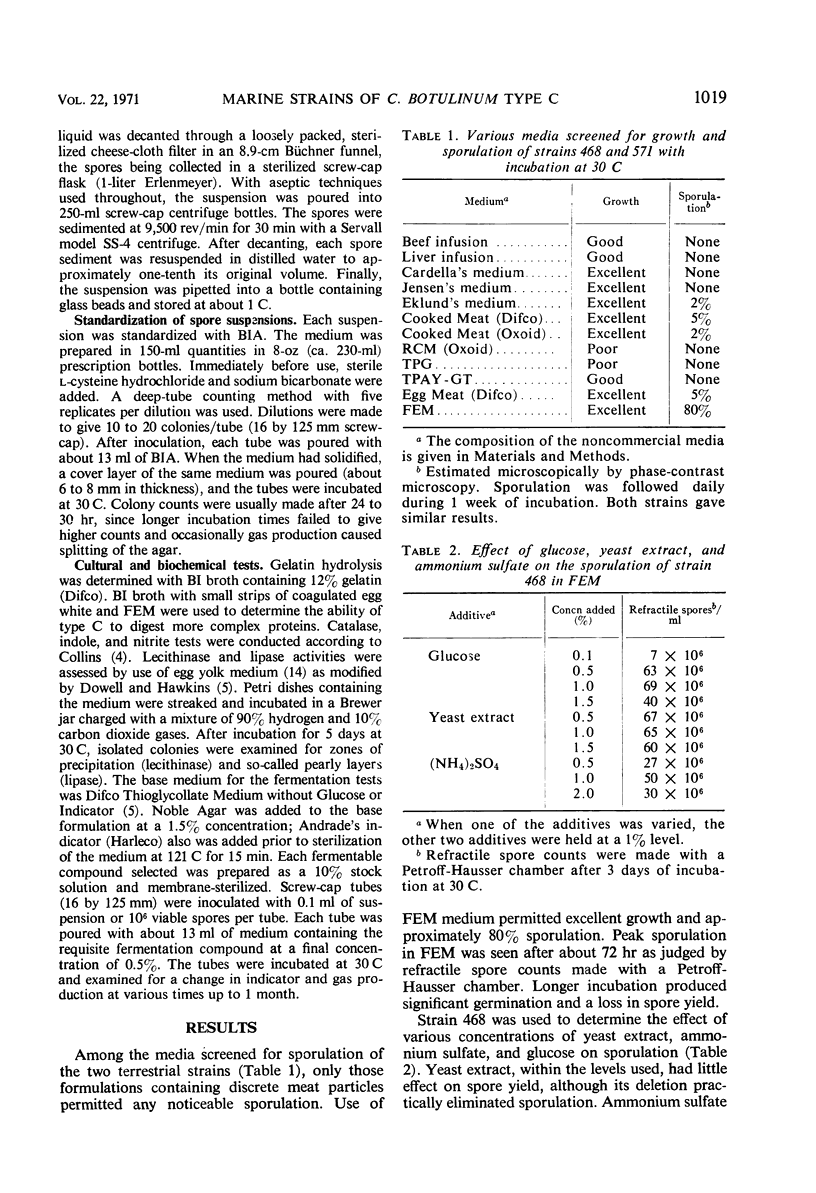

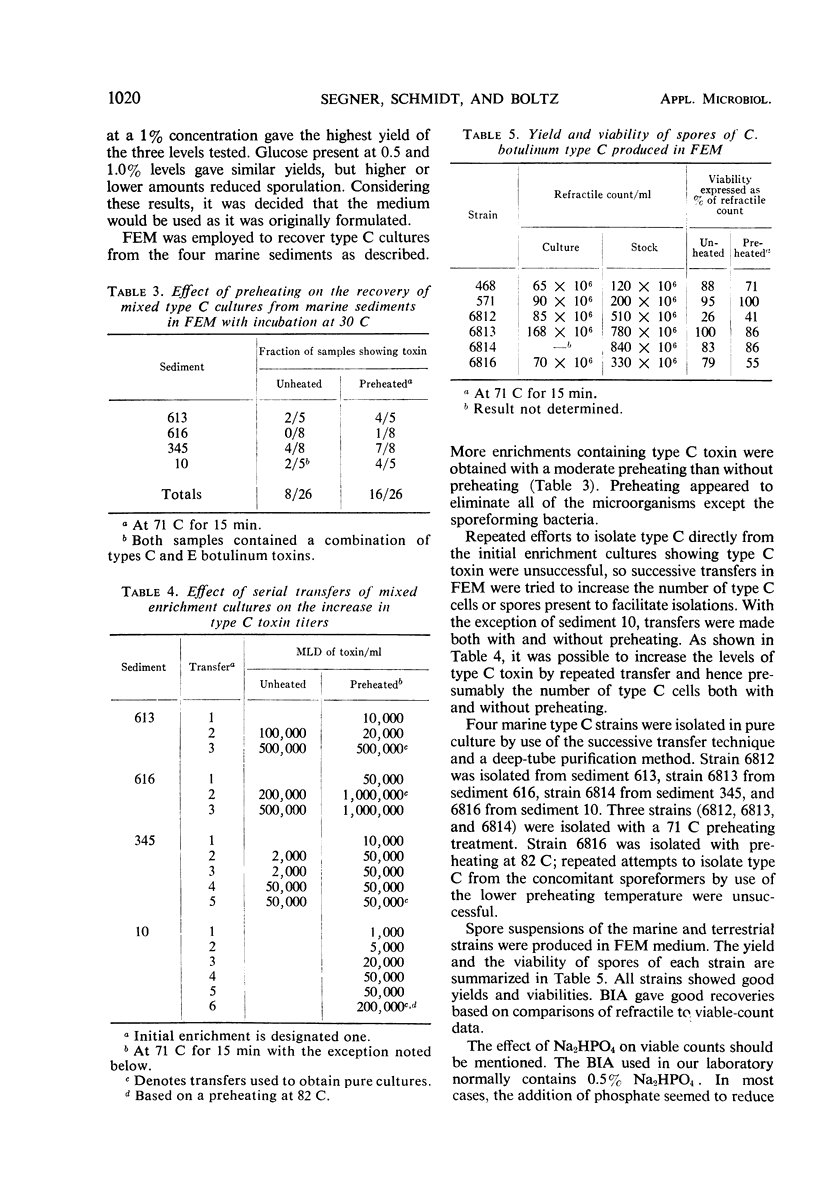

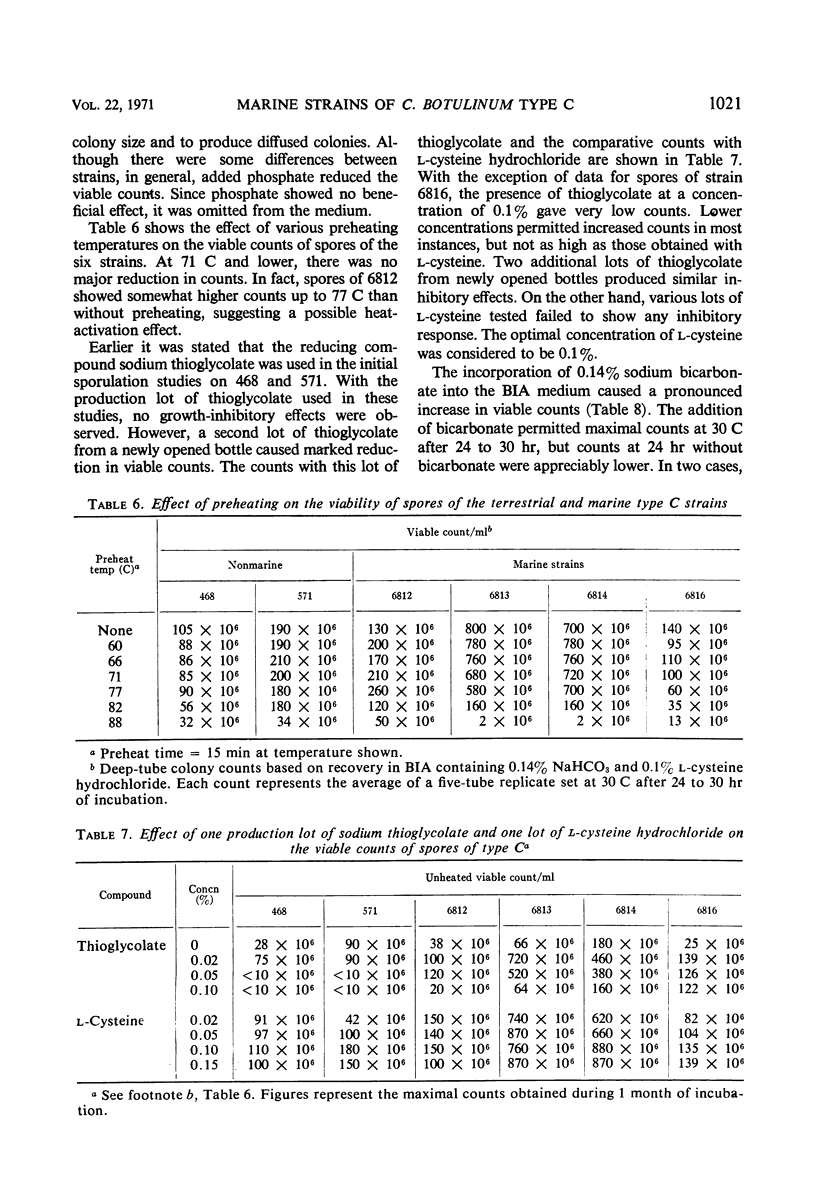

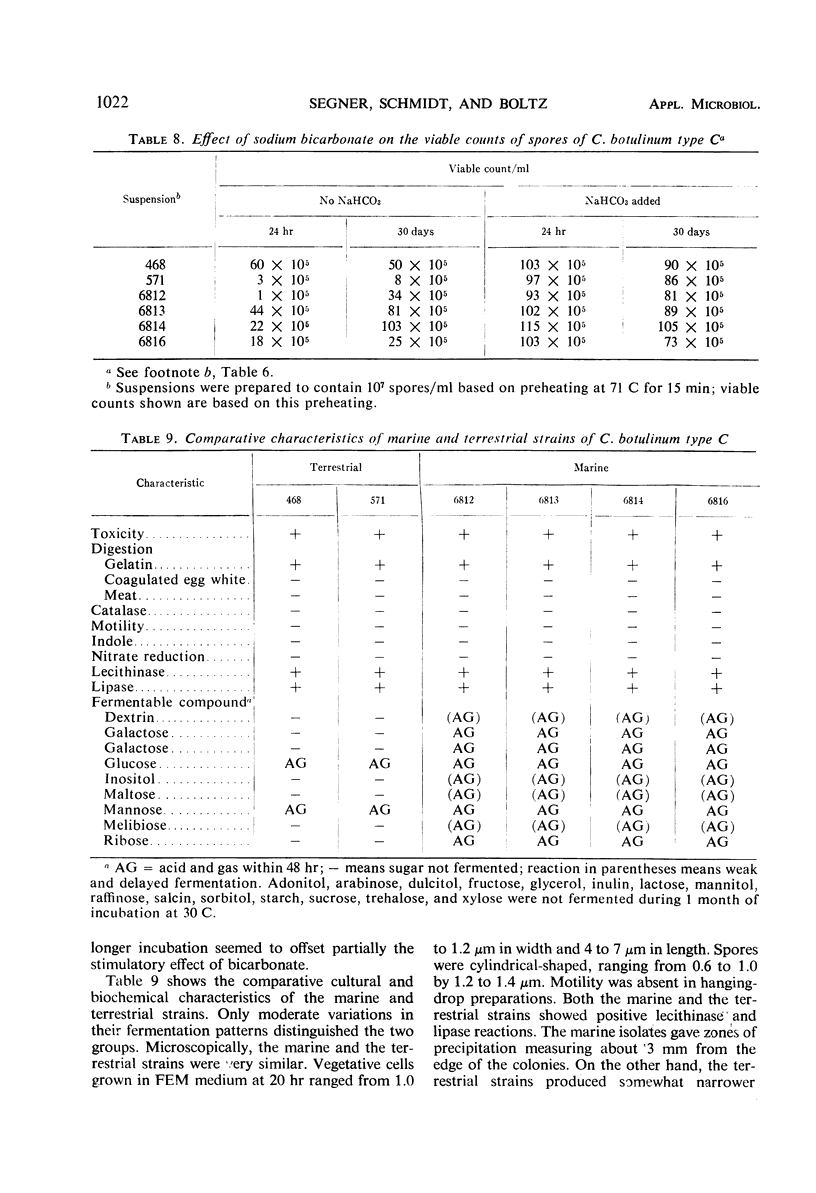

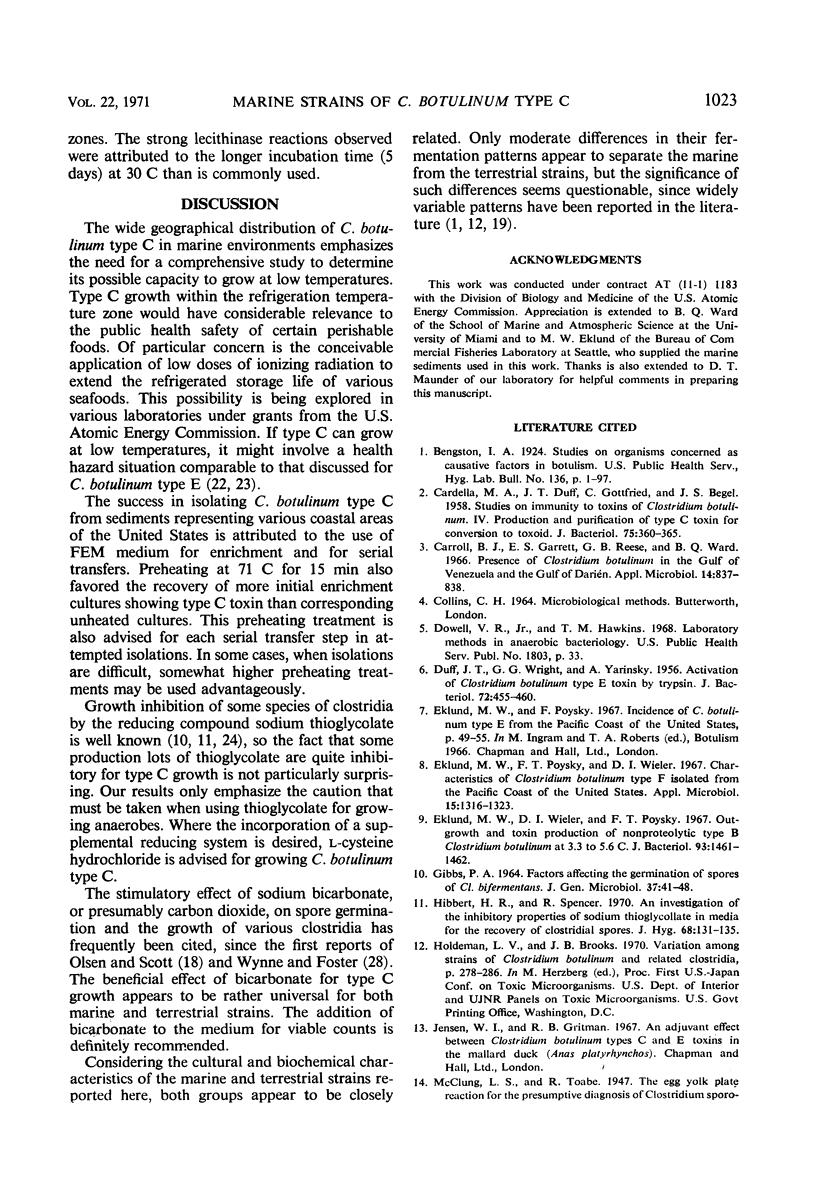

Terrestrial strains of Clostridium botulinum type C, designated 468 and 571, were used to screen various media for growth and sporulation at 30 C. Of the various formulations tested, only egg meat medium fortified with 1% additions of yeast extract, ammonium sulfate, and glucose (FEM medium) gave good growth and satisfactory sporulation. FEM medium was used to recover four marine type C isolates from inshore sediments collected along the Atlantic, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Pacific coasts of the United States. The isolation techniques involved repeated transfer of cultures showing type C toxin in FEM medium and purification by a deep tube method. The medium used for purification was beef infusion-agar supplemented with 0.14% sodium bicarbonate and 0.1% l-cysteine hydrochloride. l-Cysteine was adopted in preference to sodium thioglycolate, because some lots of the latter were definitely inhibitory for growth. The addition of bicarbonate markedly increased viable spore counts of both the marine and terrestrial strains. Various cultural and biochemical characteristics of the marine and the terrestrial strains were compared. With the exception of some variations in their fermentation patterns, both groups showed similar characteristics. Of 23 fermentable compounds tested, the terrestrial strains attacked only glucose and mannose. The marine strains fermented glucose, mannose, galactose, and ribose actively; dextrin, inositol, maltose, and melibiose were weakly fermented.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- CARDELLA M. A., DUFF J. T., GOTTFRIED C., BEGEL J. S. Studies on immunity to toxins of Clostridium botulinum. IV. Production and purification of type C toxin for conversion to toxoid. J Bacteriol. 1958 Mar;75(3):360–365. doi: 10.1128/jb.75.3.360-365.1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll B. J., Garrett E. S., Reese G. B., Ward B. Q. Presence of Clostridium botulinum in the Gult of Venezuela and the Gulf of Darién. Appl Microbiol. 1966 Sep;14(5):837–838. doi: 10.1128/am.14.5.837-838.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DUFF J. T., WRIGHT G. G., YARINSKY A. Activation of Clostridium botulinum type E toxin by trypsin. J Bacteriol. 1956 Oct;72(4):455–460. doi: 10.1128/jb.72.4.455-460.1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund M. W., Poysky F. T., Wieler D. I. Characteristics of Clostridium botulinum type F isolated from the Pacific Coast of the United States. Appl Microbiol. 1967 Nov;15(6):1316–1323. doi: 10.1128/am.15.6.1316-1323.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund M. W., Wieler D. I., Poysky F. T. Outgrowth and toxin production of nonproteolytic type B Clostridium botulinum at 3.3 to 5.6 C. J Bacteriol. 1967 Apr;93(4):1461–1462. doi: 10.1128/jb.93.4.1461-1462.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIBBS P. A. FACTORS AFFECTING THE GERMINATION OF SPORES OF CLOSTRIDIUM BIFERMENTANS. J Gen Microbiol. 1964 Oct;37:41–48. doi: 10.1099/00221287-37-1-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbert H. R., Spencer R. An investigation of the inhibitory properties of sodium thioglycollate in media for the recovery of clostridial spores. J Hyg (Lond) 1970 Mar;68(1):131–135. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400028588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEYER K. F. The status of botulism as a world health problem. Bull World Health Organ. 1956;15(1-2):281–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PREVOT A. R., TERRASSE J., DAUMAIL J., CAVAROC M., RIOL J., SILLIOC R. Existence en France du botulisme humain de type C. Bull Acad Natl Med. 1955 Jun 21;139(21-22):355–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts T. A. Sporulation of mesophilic clostridia. J Appl Bacteriol. 1967 Dec;30(3):430–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1967.tb00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TREADWELL P. E., JANN G. J., SALLE A. J. Studies on factors affecting the rapid germination of spores of Clostridium botulinum. J Bacteriol. 1958 Nov;76(5):549–556. doi: 10.1128/jb.76.5.549-556.1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward B. Q., Carroll B. J., Garrett E. S., Reese G. B. Survey of the U.S. Atlantic coast and estuaries from Key Largo to Staten Island for the presence of Clostridium botulinum. Appl Microbiol. 1967 Jul;15(4):964–965. doi: 10.1128/am.15.4.964-965.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward B. Q., Carroll B. J., Garrett E. S., Reese G. B. Survey of the U.S. Gulf Coast for the presence of Clostridium botulinum. Appl Microbiol. 1967 May;15(3):629–636. doi: 10.1128/am.15.3.629-636.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward B. Q., Garrett E. S., Reese G. B. Further Indications of Clostridium botulinum in Latin American Waters. Appl Microbiol. 1967 Nov;15(6):1509–1509. doi: 10.1128/am.15.6.1509-1509.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wynne E. S., Foster J. W. Physiological Studies on Spore Germination, with Special Reference to Clostridium botulinum: III. Carbon Dioxide and Germination, with a Note on Carbon Dioxide and Aerobic Spores. J Bacteriol. 1948 Mar;55(3):331–339. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]