Abstract

Context:

Ageing is an unavoidable facet of life. Yogic practices have been reported to promote healthy aging. Previous studies have used either yoga therapy interventions derived from a particular school of yoga or have tested specific yogic practices like meditation.

Aims:

This study reports the development, validation and feasibility of a yoga-based intervention for elderly with or without mild cognitive impairment.

Settings and Design:

The study was conducted at the Advanced Centre for Yoga, National Institute for Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore. The module was developed, validated, and then pilot-tested on volunteers.

Materials and Methods:

The first part of the study consisted of designing of a yoga module based on traditional and contemporary yogic literature. This yoga module along with the three case vignettes of elderly with cognitive impairment were sent to 10 yoga experts to help develop the intended yoga-based intervention. In the second part, the feasibility of the developed yoga-based intervention was tested.

Results:

Experts (n=10) opined the yoga-based intervention will be useful in improving cognition in elderly, but with some modifications. Frequent supervised yoga sessions, regular follow-ups, addition/deletion/modifications of yoga postures were some of the suggestions. Ten elderly consented and eight completed the pilot testing of the intervention. All of them were able to perform most of the Sukṣmavyayāma, Prāṇāyāma and Nādānusaṇdhāna (meditation) technique without difficulty. Some of the participants (n=3) experienced difficulty in performing postures seated on the ground. Most of the older adults experienced difficulty in remembering and completing entire sequence of yoga-based intervention independently.

Conclusions:

The yoga based intervention is feasible in the elderly with cognitive impairment. Testing with a larger sample of older adults is warranted.

Keywords: Cognitive impairment, elderly, yoga-based intervention

INTRODUCTION

The elderly population in India is estimated to grow from 71 million in 2001 to 179 million in 2031.[1] Epidemiological studies on Indian population concur that more than 50% of the elderly above 60 years of age suffer from chronic medical conditions and its prevalence increases with age.[2] Health problems especially cardiovascular disorders, diabetes and hypertension are the widely prevalent while arthritis was mostly prevalent in women.[3] Depression was the most common psychiatric disorder followed by dementia in the elderly.[4] Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is a transitional state between normal ageing and dementia. MCI is considered to be a pre-Alzheimer's Dementia state with 10-15% of the elderly with MCI converting to Alzheimer's Dementia annually.[5] Presence of vascular risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, increased levels of cholesterol; neuropsychiatric conditions such as psychosis, depression, chronic psychological distress[6,7,8,9] are implicated in the development of MCI.

Yogic practices have been reported to promote healthy aging.[10,11] Yoga-based interventions are known to improve gait and balance, flexibility and mood in the elderly.[12,13] Most of the previous studies have used either yoga therapy interventions derived from a particular school of yoga or have tested individual yogic practices such as meditation in the elderly.[12,13,1,4,15] Chen et al. (2007) reported development and feasibility of a yoga-based program for elderly living in community homes. The yoga module used in this study was aimed at improving general health and quality-of-life in elderly.[15] The current study reports the development, validation and testing of a yoga-based intervention developed from the traditional literature for the elderly with or without MCI. We also chose such practices that the elderly could practice without difficulty as per our judgment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Designing of the yoga-based intervention

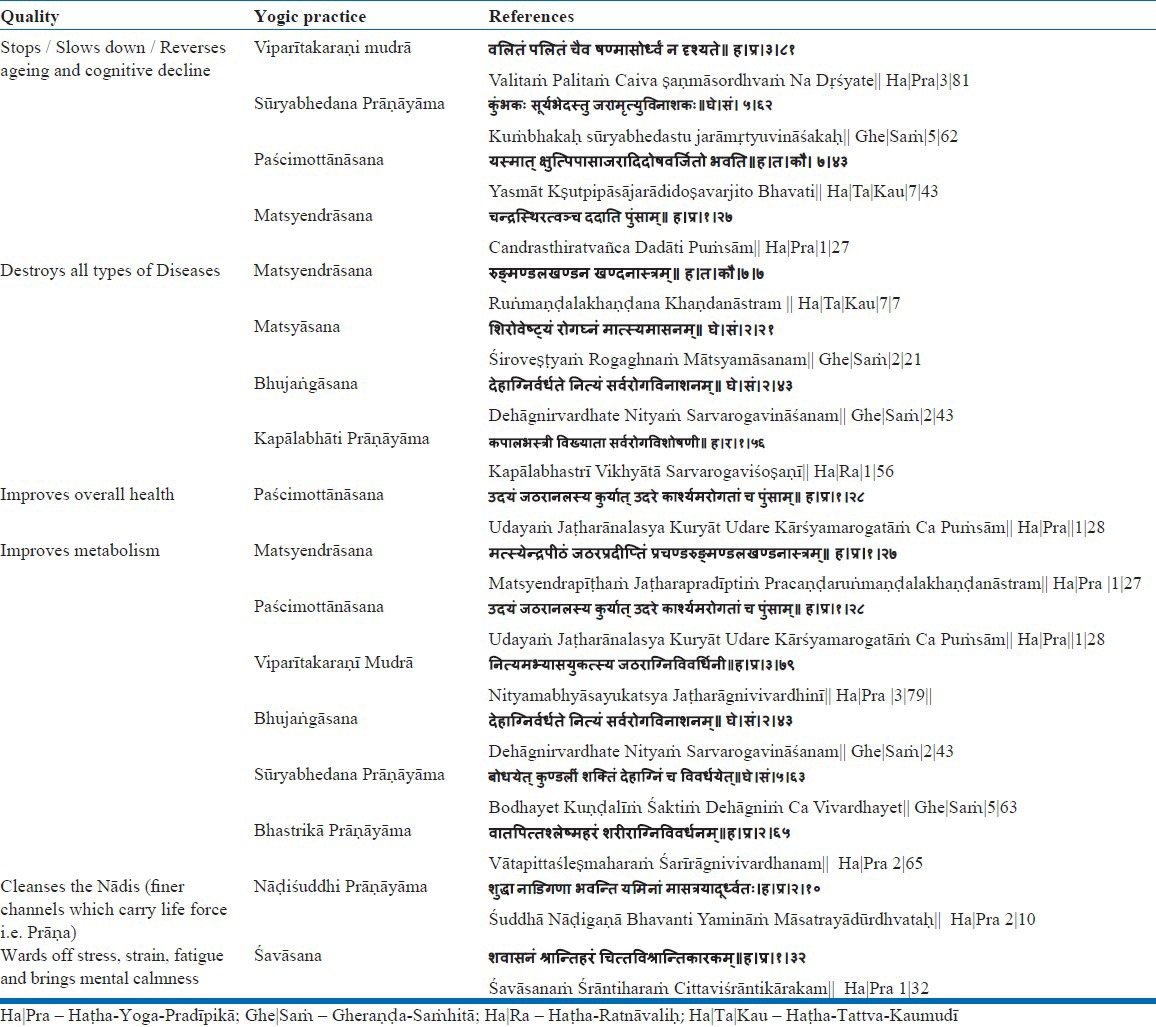

This phase of the study began with a systematic review of traditional[16,17,18,19,20] and contemporary yoga texts.[21,22,23,24,25] Yogic practices, which have been quoted in these texts to have the ability to improve age related decline of cognition specifically memory, executive function and health related quality-of-life were searched for in these texts. Since cognition and quality-of-life in elderly are related to factors such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, vascular risk indices such as elevated cholesterol levels, depression, chronic psychological distress, yogic practices quoted in the selected texts to have direct or indirect benefits in these conditions were also included. As references to direct effects on cognition were not available, yoga practices that slowed aging were chosen with an expectation of indirect effect on cognition [Table 1]. Complex, advanced and balancing postures, yogic practices with no clear description, as well as yogic practices generally avoided in cardiovascular, cerebrovascular conditions and uncontrolled hypertension were excluded. Suitability of the yoga-based intervention in elderly is further ensured by modifying the selected yogic postures by using appropriate props and support wherever needed. A comprehensive yoga module was thus designed comprising of Sukṣmavyayāma (warm-up exercises), Yogāsana (physical postures), Kriya (Purificatory practices), Praṇayāma (Breathing exercises) and meditation in the form of Nādānusaādhāna.

Table 1.

Yogic practices with abilities to promote healthy ageing and holistic health according to traditional Yogic Texts

Validation of yoga-based intervention

Three case vignettes of elderly with symptoms amounting to MCI were sent with the text of the yoga module to 15 experts on yoga. Ten experts responded with completed yoga module questionnaire sent for validation. The yoga validation questionnaire elicited the experts rating on the usefulness of each practice in elderly with cognitive impairment on a scale of 1-5 (1-Not at all, 2-A little, 3-Moderately, 4-Very much and 5-Extremely). Yogic practices, which scored three or more from at least 80% of the experts were included in the final module. Dichotomous responses such as Yes/No were obtained in determining the appropriateness of duration of each session and yoga training. Further, qualitative responses about the appropriateness of yogic practice, duration of each session, as well as yoga training, sequence of yoga practices and overall yoga module were collected. These experts were associated with different yoga schools, such as Iyengar yoga, Sudarshan Kriya yoga and others.

Pilot study of the yoga-based intervention in elderly

The pilot was an open-label exploratory study approved by the institutional ethical committee of the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS). In this study, we tested the feasibility of the validated yoga-based intervention on 10 consenting elderly subjects. The majority of them (nine) met the criteria for MCI. The subjects were invited to participate in the pilot study through workshops and paper advertisements in popular news dailies. Interested elderly (>60 years) were recruited after obtaining written consent. Elderly with dementia or other neurodegenerative disorders, major depressive disorder, psychosis, anxiety disorder, substance abuse other than nicotine, severe sensory impairment and inability to do yoga due to severe physical illness were excluded.

Subjects were taught 1 hour yoga-based intervention for 1 month at Advanced Centre for Yoga-NIMHANS. They were encouraged to participate daily with a minimum attendance of 12 sessions in 1 month. At the end of 1 month, the subjects’ ability to perform yoga was rated on a yoga performance assessment tool by the instructor who taught the yoga.

Yoga performance assessment tool

This is a yoga instructor rated scale exclusively designed for the current study. This scale rates the performance of subject's practice during the supervised yoga sessions. The scale is divided into two domains namely:

Performance of individual practices on a scale of 0-3 (0-Can’t practice at all, 1-Needs assistance throughout the practice, 2-Needs assistance through some steps of the practice, 3-Can practice with ease (without assistance of instructor))

Similar rating for overall yoga performance ability was sought on five parameters: (a) Completes the entire yoga sequence, (b) remember and completes each step of the yoga practice, (c) co-ordinates breathing with yoga-asana, (d) breathing as instructed in Pranayama (e) relaxes during the yogic practices.

Statistical analysis

For each component of the module, we tested the null hypothesis that 50% or less experts would opine that it is useful (i.e., give a score of three or more-moderately or more useful). Thus, with a one variable Chi-square test and one tailed probability of <0.05, a cut off of 80% was chosen as the criteria to retain a component – i.e., if more than 80% experts gave a score of >3, then such a component was retained.

RESULTS

Validation of yoga-based intervention

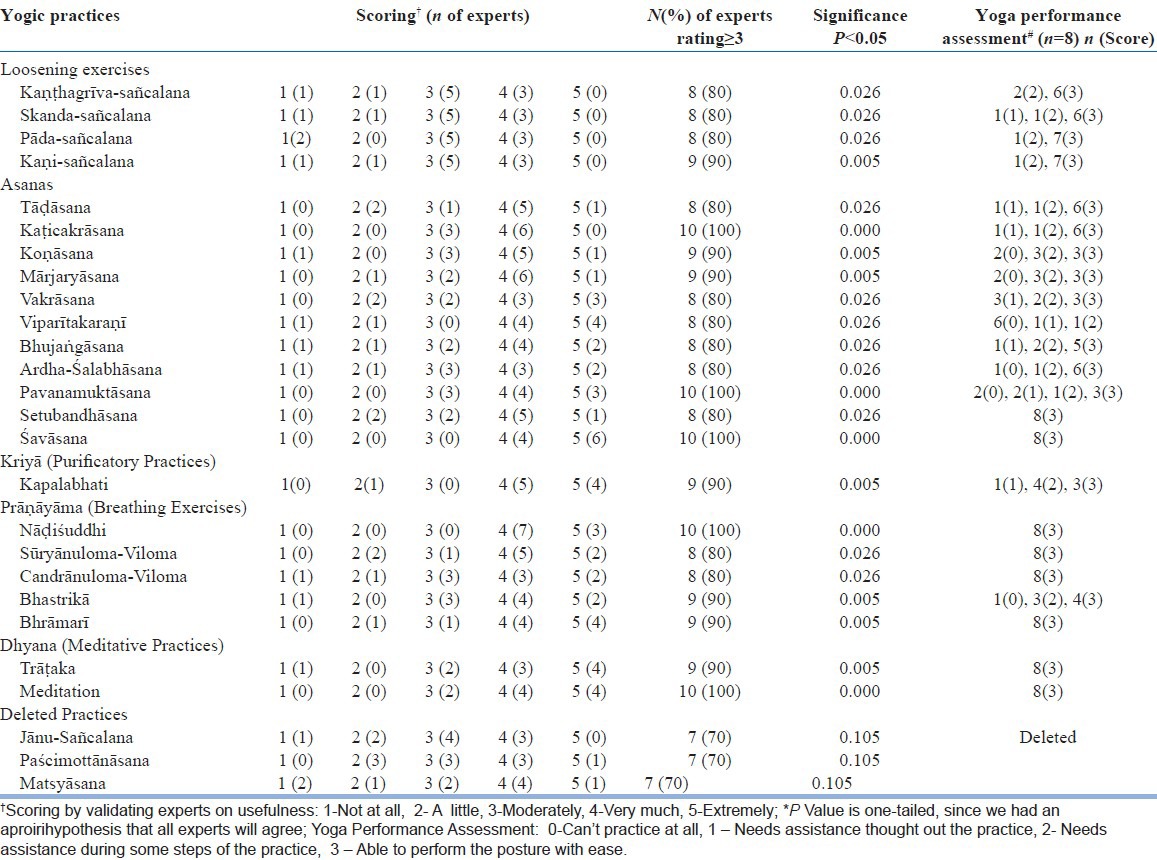

Ten experts (5-females) in yoga therapy and research consented to validate the yoga program. Age of the experts ranged between 30 and 62 years (Mean 44.50, standard deviation (SD) ±9.94). The average number of years of experience in yoga (SD) of the experts after formal education was 16.8 (SD±8.28). Scoring obtained for individual yogic practices is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Experts scoring of individual practices of Yoga-based intervention and Yoga Performance Assessment

Three practices (Jānusancālana, Paścimottānāsana and Matsyāsana.) were given a score of ≥3 by only 70% of the experts (P>0.05) and were therefore deleted from the final module [Table 2]. All felt Sukṣmavyayāma is necessary to improve motor functions and joint mobility in elderly. Majority of the experts felt 1 h of the yoga session daily will be sufficient to derive desired benefits. Most of the experts felt one supervised session every month after initial supervised yoga training until 6 months or 2 months of supervised yoga training initially is necessary to promote compliance among subjects. Experts suggested judicious use of Kapālabhāti and Bhastrikā in the elderly with medical conditions especially hypertension and diabetes. Only one of the experts suggested inclusion of walking, diet advice and yoga philosophy classes/satsang.

Pilot study

Following advertisement 28 persons responded and were screened. Having to travel long distances for attending yoga classes (in 10), unwilling to follow the yoga module that was being tested (in 3), a diagnosis of depression (in 3), Parkinson's disease (in 1) and a recent cardiac surgery (in 1) led to the exclusion of 18 subjects. Ten elderly (2 females) who met the inclusion criteria were recruited into the study. They were between 60 and 72 years of age (mean 65.1 years SD±4.8 years) and had a mean of 14 years (SD 1.8) years of education. All (n=10) had one or more health-related issues such as diabetes, hypertension, gastritis, osteoarthritis of the knee joint etc. All except one had subjective memory complaint. Their cognition was assessed on Hindi mental status examination.[26] The group's score averaged 29 (1.69) and none of the individuals had a score <27. None had clinical evidence of dementia. Eight subjects practiced yoga at least for 10 days, out of which two and six subjects attended yoga sessions daily and thrice in a week respectively. Two subjects dropped out of the study citing problems related to travel and working schedule. The details of the yoga performance of individual yogic practices are presented in Table 2. Six (75%) subjects were able to complete more than 60% of the practices from the yoga-based intervention program. Six subjects (75%) were able to remember and complete the steps of each yogic practice. Six (75%) and five (62%) of subjects respectively were able to co-ordinate breathing with Yoga-asana and perform breathing as instructed in Pranayama section of the yoga module. All individuals reported spontaneously one or more benefits that they attributed to yoga. Such experiences were an improvement in concentration, mood and backache. No subject reported any adverse event spontaneously.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, effort was made to develop a comprehensive yoga module based on traditional textual references and expert's advice. Our comprehensive search in traditional yogic texts did not yield any direct references for yogic practices with the ability of improving memory/cognition in the elderly. Yogic practices with an ability of slowing down the ageing process and improving quality-of-life were thus short listed. Since yoga was practiced seeking salvation and metaphysical benefits, most of the ancient texts explain methods to fulfill these benefits. However, recent hatha yogic texts[18,19] lay more emphasis on improving health through different yogic practices. Usefulness of yogic practices and importance of modifications to postures to enhance adaptability in the elderly and pregnancy are discussed.[19]

Experts from different schools of yoga (Art of Living, Iyengar yoga and others) participated in the validation process and were unanimous in the selection of yogic practices except for Jānusancālana, Paścimottanāsana and Matsyāsana. Nearly all (22 of 25, 88%) practices were agreed upon by all experts to be retained in the final module. Most of the contemporary yogic texts consider these excluded practices as intermediate to advanced level. Therefore, the experts may have excluded these practices for older adults. Chen et al. (2007)[15] opines that older adults were more likely to adhere to the yoga program which had simpler, easy to perform yogic practices thus providing the opportunity for self-improvement.

More than 50% of the subjects either could not perform or had difficulty in performing postures such as Koṇāsana, Mārjāriāsana, Vakrāsana, Viparītakaraṇi, Pavanamuktāsana, Kapālabhāti and Bhastrikā. Though most (75%) were able to remember and practice the steps of each Yogäsana in the module, majority (n=7, 87.5%) of the participants were unable to remember and complete sequence of all yogic practices in the prescribed order without help while many failing even to complete the entire yoga program. Memory problem, pre-existing medical illness and shorter attendance during the 1-month supervised yoga program might have affected the yoga performance ability of the participants. These findings validate the experts’ suggestions to increase the duration of the supervised yoga program and/or contact programs at frequent intervals. The participants gave a positive feedback such as improved back ache, flexibility, mood and concentration after the yoga-based intervention. These perceived benefits may also be attributed to the Sukṣmavyayāma, Praṇayāma and Nādānusaṇdhāna (meditation) which most these participants were able to perform with ease. It is important to note that none of the subjects who participated in the pilot study spontaneously complained of any serious adverse effects. These findings support a case for testing this module in prospective trials in the elderly.

CONCLUSION

Based on traditional texts a yoga module for elderly with an emphasis on obtaining benefits in cognition was developed. All experts validating the program agreed on most of these practices as appropriate. The pilot study indicated that the elderly found it useful and reported spontaneously no adverse events. Increase in number of the sessions to train the elderly was suggested and the pilot study hinted that fewer practice sessions may be inadequate. The validated yoga program's performance remains to be tested in prospective designs.

This study demonstrated that the developed yoga program has content and face validity. It is feasible to train the elderly to perform these practices. Longer training seems warranted. Pilot data suggests potential benefits with safety. However, clinical validation in scientific trials is warranted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mr. Sushrutha and Mr. Bhagath of Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anusandhana Samsthana for their help with transliteration.

Footnotes

Source of Support: The research was done under the Advanced Centre for Yoga - Mental Health and Neurosciences, a collaborative centre of NIMHANS and the Morarji Desai Institute of Yoga, New Delhi

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rajan SI, Mishra US. Defining old age: An Indian assessment. J UN Inst Aging. 1995;5:31–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Sample Survey Organisation. Socio-economic profile of aged persons. Sarvakshana. 1991;15:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Srinivasan K, Vaz M, Thomas T. Prevalence of health related disability among community dwelling urban elderly from middle socioeconomic strata in Bangaluru, India. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:515–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Varghese M, Patel V. 2nd ed. New Delhi (India): Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Health; 2005. The greying of India-mental health perspective. Mental Health: An Indian Perspective 1946-2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E. Mild cognitive impairment: Clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:303–8. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reitz C, Tang MX, Manly J, Mayeux R, Luchsinger JA. Hypertension and the risk of mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1734–40. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.12.1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steffens DC, Otey E, Alexopoulos GS, Butters MA, Cuthbert B, Ganguli M, et al. Perspectives on depression, mild cognitive impairment, and cognitive decline. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:130–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monastero R, Palmer K, Qiu C, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Heterogeneity in risk factors for cognitive impairment, no dementia: Population-based longitudinal study from the Kungsholmen Project. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15:60–9. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000229667.98607.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson RS, Schneider JA, Boyle PA, Arnold SE, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Chronic distress and incidence of mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2007;68:2085–92. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000264930.97061.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhar HL. Health and aging. Indian J Med Sci. 1997;51:373–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zettergren KK, Lubeski JM, Viverito JM. Effects of a yoga program on postural control, mobility, and gait speed in community-living older adults: A pilot study. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2011;34:88–94. doi: 10.1519/JPT.0b013e31820aab53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen KM, Chen MH, Chao HC, Hung HM, Lin HS, Li CH. Sleep quality, depression state, and health status of older adults after silver yoga exercises: Cluster randomized trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:154–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donesky-Cuenco D, Nguyen HQ, Paul S, Carrieri-Kohlman V. Yoga therapy decreases dyspnea-related distress and improves functional performance in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A pilot study. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:225–34. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krishnamurthy M, Telles S. Effects of Yoga and an Ayurveda preparation on gait, balance and mobility in older persons. Med Sci Monit. 2007;13:LE19–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen KM, Tseng WS, Ting LF, Huang GF. Development and evaluation of a yoga exercise programme for older adults. J Adv Nurs. 2007;57:432–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Digamberji S, Gharote ML, editors. Lonavala, India: Kaivalyadhama S.M.Y.M Samiti; 1997. Gheranda Samhita. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Desikachar TK, Krishnamacharya T, editors. Chennai, India: Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram; 1998. Nathamuni's Yoga Rahasya. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gharote ML, Devnath P, Jha VK, editors. Lonavla, India: The Lonavla Yoga Institute (India); 2007. Hathatatvakaumudi: A treatise on Hathayoga by Sundaradeva. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Digambarji S, Kokaje RS, editors. Lonavla, India: Kaivalyadhama, S.M.Y.M. Samiti; 1998. Hathapradipika of Svatmarama. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gharote ML, Devnath P, Jha VK, editors. Lonavla: The Lonavla Yoga Institute (India); 2002. Hatharatnavali of Srinivasayogi. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iyengar BK. New Delhi, India: Harper Collins India; 1966. Light on Yoga. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brahmachari D. 1st ed. Mumbai, India: Asia Publishing House; 1970. Yogasana Vijnana-The Science of Yoga. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acharya IN. 1st ed. New Delhi, India: Morarji Desai National Institute of Yoga; 2007. Yogasana. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagarathna R, Nagendra HR. 1st ed. Bangalore, India: Swami Vivekananda Yoga Prakashana; 2001. Yoga For Positive Health. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saraswati S. Munger, Bihar, India: Yoga Publications Trust; 1969. Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ganguli M, Ratcliff G, Chandra V, Sharma S, Gilby J, Pandav R, et al. A Hindi version of the MMSE: The development of a cognitive screening instrument for a largely illiterate rural elderly population in India. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1995;10:367–77. [Google Scholar]