Abstract

Purpose

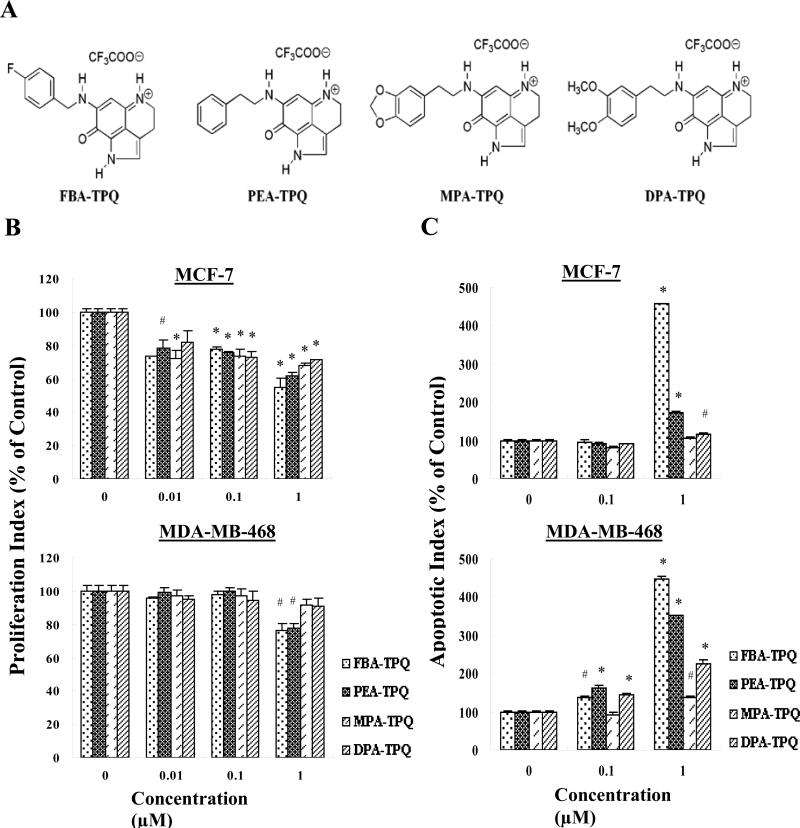

The present study was designed to determine biological structure-activity relationships (SAR) for four newly synthesized analogs of natural compounds (makaluvamines). The compounds, 7-(4-fluorobenzylamino)-1,3,4,8-tetrahydropyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinolin-8(1H)-one (FBA-TPQ); 7-(phenethylamino)-1,3,4,8-tetrahydro-pyrrolo[4,3,2-de]-quinolin-8(1H)-one (PEA-TPQ); 7-(3,4-methylenedioxyphenethylamino)-1,3,4,8-tetrahydropyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinolin-8(1H)-one (MPA-TPQ); 7-(3,4-dimethoxyphenethylamino)-1,3,4,8-tetrahydropyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinolin-8(1H)-one (DPA-TPQ), were synthesized and purified, and their chemical structures were elucidated on the basis of physicochemical constants and nuclear magnetic resonance spectra.

Experimental Design

The structure-activity relationship of the compounds was initially evaluated by comparing their in vitro cytotoxicity against 14 human cell lines. Detailed in vitro and in vivo studies were then done in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cell lines.

Results

The in vitro cytotoxicity was compound-, dose-, and cell line dependent. Whereas all of the compounds exerted some activity, FBA-TPQ was the most potent inducer of apoptosis and the most effective inhibitor of cell growth and proliferation, with half maximal inhibitory concentration values for most cell lines in the range of 0.097-2.297 μmol/L. In MCF-7 cells, FBA-TPQ exposure led to an increase in p53/p-p53, Bax, ATM/p-ATM, p-chk1 and p-chk2, p-H2AX, and cleavage of poly (ADP)ribose polymerase, caspases -3, -8, and -9. It also decreased the levels of MDM2, E2F1, Bcl-2, chk1/2 and proteins associated with cell proliferation [cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk)2, Cdk4, Cdk6, cyclin D1, etc). Moreover, FBA-TPQ inhibited the growth of breast cancer xenograft tumors in nude mice in a dose-dependent manner. Western blot analysis of the xenograft tumors indicated that similar changes in protein expression also occur in vivo.

Conclusion

Our preclinical data indicate that FBA-TPQ is a potential therapeutic agent for breast cancer, providing a basis for development of the compound as a novel anticancer agent.

Keywords: Breast cancer, apoptosis, DNA damage, MDM2, p53

Introduction

Breast cancer poses a major health problem worldwide. Although the mortality rate has decreased as a result of earlier detection and more aggressive treatment/prevention strategies, new therapies are still needed to further improve the survival of breast cancer patients, especially those with estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor/human epidermal growth factor receptor (Her)2- negative disease. In the search for novel cancer therapeutic agents, various plant and animals species have provided lead compounds for further development (1). For example, a large number of bioactive marine alkaloids with novel structures have been isolated from marine sponges; some of these compounds have exhibited a variety of antitumor activities (2).

One class of marine alkaloids containing a pyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinoline skeleton has received increasing attention as a source of new anticancer drugs (3-8). There has been a rapid growth of interest in their synthesis and biological evaluation (reviewed in refs. 9-11). Several of these makaluvamine compounds have exhibited in vitro cytotoxicity against human cancer cell lines, which was initially attributed to topoisomerase II inhibition (12). However, we and others have observed that topoisomerase II inhibition is not the only mechanism that is responsible for the cytotoxicity of makaluvamines (13, 14). Moreover, Dijoux et al have demonstrated that some makaluvamines cause direct DNA damage under reductive activation conditions (15).

Although the enthusiasm for some of the makaluvamines has been dampened by their lack of a novel mechanism of action (because effective topoisomerase inhibitors are already available in the clinic), the compounds have sufficient (unrelated to topoisomerase II) activity to warrant further consideration. We have recently developed a synthetic route for generating makaluvamines in our laboratory (13). Using this method, we have synthesized > 40 novel makaluvamine analogs and have evaluated their anticancer activities (14, 16). In the present study, we compared the anticancer activity of four novel makaluvamine analogs against a variety of cancer cell lines. The structures of the four makaluvamine analogs are given in Fig. 1A. The compounds exerted their most potent effects against breast cancer cell lines, so we focused our in-depth studies in models of breast cancer. Because 7-(4-fluorobenzylamino)-1,3,4,8-tetrahydropyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinolin-8(1H)-one (FBA-TPQ) was the most effective of the four compounds, we accomplished further in vitro and in vivo studies of this compound and examined the possible molecular mechanisms responsible for its anticancer activity.

Figure 1.

(A) Chemical structures of the makaluvamine analogs. (B) Anti-proliferative effects of FBA-TPQ, PEA-TPQ, MPA-TPQ and DPA-TPQ on human breast cancer cells in culture. MCF-7 and MDA-MB-468 cells were exposed to various concentrations of the compounds for 24 h, followed by measurement of cell proliferation via the bromodeoxyuridine assay. All assays were done in triplicate. The proliferation index is in comparison with untreated cells (#p<0.05, *p<0.01). (C) Induction of apoptosis in breast cancer cells by FBA-TPQ, PEA-TPQ, MPA-TPQ and DPA-TPQ. MCF-7 and MDA-MB-468 cells were exposed to various concentrations of the compounds for 48 h, followed by measurement of apoptosis by Annexin V assay/flow cytometry. The apoptotic index was calculated against untreated control cells (#p<0.05, *p<0.01).

Materials and Methods

Synthesis and purification of the test compounds

To conduct the present in vitro studies, we synthesized each of the four analogs, FBA-TPQ; 7-(phenethylamino)-1,3,4,8-tetrahydropyrrolo[4,3,2-de]-quinolin-8(1H)-one (PEA-TPQ); 7-(3,4-methylenedioxyphenethylamino)-1,3,4,8-tetrahydropyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinolin-8(1H)-one (MPA-TPQ); and 7-(3,4-dimethoxyphenethylamino)-1,3,4,8-tetrahydropyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinolin-8(1H)-one (DPA-TPQ) in 30-50 mg quantities. FBA-TPQ was prepared on a larger scale (600 mg) in order to accomplish the in vivo studies. The purity of these compounds was greater than 99.0%, based on 1H-NMR, 13C-NMR and mass spectral analyses. The data for the individual compounds are given below.

FBA-TPQ Spectral data

1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 2.95 (t, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz), 3.83 (t, 2H, J = 7.6 Hz), 4.57 (s, 2H), 5.40 (s, 1H), 7.01–7.16 (m, 3H) and 7.30–7.39 (m, 2H); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 19.4, 44.2, 47.3, 86.4, 116.5 and 116.8 (C-F coupling), 120.2, 123.6, 125.7, 127.1, 130.4 and 130.5 (C-F coupling), 133.3, 155.0 and 160.0 (C-F coupling), 165.4, 168.8, 173.2; MS (ES±) m/z 296 (M±).

PEA-TPQ Spectral data

1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 2.93 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz), 2.97 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz), 3.60 (t, 2H, J = 7.4 Hz), 3.84 (t, 2H, J = 7.8 Hz), 5.42 (s, 1H), 7.13 (s, 1H), 7.18–7.33 (m, 5H); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 19.5, 35.1, 44.1, 46.2, 85.3, 120.2, 123.8, 125.4, 127.2, 127.8, 129.8 (2C), 129.9 (2C), 139.3, 155.0, 159.7 and 168.4; MS (ES±) m/z 292(M±).

MPA-TPQ Spectral data

1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 2.88 (t, 2H, J = 7.8 Hz), 2.94 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz), 3.55 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.84 (t, 2H, J = 7.8 Hz), 5.41 (s, 1H), 5.89 (s, 2H), 6.65–6.79 (m, 3H), 7.14 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 19.5, 34.8, 44.1, 46.3, 85.2, 102.3, 109.3, 110.1, 120.2, 123.0, 123.9, 125.4, 127.2, 133.0, 147.9, 149.4, 155.0, 159.7 and 168.5; MS (ES±) m/z 336 (M±).

DPA-TPQ Spectral data

1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 2.86–3.01 (m, 4H), 3.57 (t, 2H, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.79 (s, 3H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 3.85 (t, 2H, J = 7.5 Hz), 5.39 (s, 1H), 6.78– 6.91 (m, 3H), 7.13 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 19.5, 34.8, 44.1, 46.3, 56.4, 56.5, 85.3, 113.3, 113.8, 120.2, 122.3, 123.9, 125.4, 127.3, 132.2, 149.5, 150.6, 155.0, 159.6 and 168.5; MS (ES±) m/z 352 (M±).

Chemicals and reagents

All chemicals and solvents used were of the highest analytical grade available. Cell culture supplies and media, PBS, fetal bovine serum, sodium pyruvate, non-essential amino acids, and penicillin-streptomycin were obtained from the Comprehensive Cancer Center Media Preparation Shared Facility, University of Alabama at Birmingham (Birmingham, AL). Anti-human MDM2 (SMP14), Bcl-2 (100), Bax (N-20), E2F1 (KH95), cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk)2 (M2), Cdk4 (H-22), Cdk6 (C-21), cyclin D1 (DCS-6), ATM (2C1), ATR (N-19), Chk1 (G-4), Chk2 (B-4), and poly(ADP)ribose polymerase (PARP; H-250) antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). The anti-human p53 (Ab-6) antibody was from EMD Chemicals, Inc.; the caspase-3, caspase-8, caspase-9, Chk1 (Ser317), p-Chk2 (Thr68), and p-p53 (ser15) antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. Antibodies against p-ATM (Ser1981) and p-H2AX (Ser139) were from Millipore.

Cell culture

Human cancer cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD). All cell culture media contained 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. Human breast cancer cell lines included MCF-7, MCF-7 p53 knockdown (MCF-7 p53−/−) and MDA-MB-468. MCF-7 cells were grown in MEM media containing 1mM non-essential amino acids and Earle's BSS, 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, and 10 mg/L bovine insulin. MCF-7 p53−/− cells were grown in the same media containing 0.5μg/mL puromycin (Sigma). MDA-MB-468 cells were grown in DMEM/F-12 Ham's media (DMEM/F-12 1:1 mixture). The human prostate cancer cell lines used for the study were LNCaP and PC3. LNCaP cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 media containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, glucose (4.5 mg/mL) and sodium bicarbonate (1.5 mg/mL). PC3 cells were cultured in Ham's F-12K medium containing 2 mmol/L L-glutamine. The human lung cancer cell lines included A549, H838, H358 and H1299. A549 cells were grown in Ham's F12K medium supplemented with 2 mmol/L L-glutamine and 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate. H838 and H358 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 4.5 g/L glucose, 10 mmol/L HEPES buffer, 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate and 2 mmol/L L-glutamine. H1299 cells were grown in DMEM media. The human pancreatic cancer cell lines were HPAC, PANC-1 and MIA PaCa-2. HPAC cells were grown in a 1:1 mixture of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium and Ham's F12 medium containing 1.2 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 2.5 mmol/L L-glutamine, 15 mmol/L HEPES and 0.5 mmol/L sodium pyruvate supplemented with 2 μg/mL insulin, 5 μg/mL transferrin, 40 ng/mL hydrocortisone, 10 ng/mL epidermal growth factor and 5% fetal bovine serum. PANC-1 cells were cultured with RPMI 1640 containing 1 mmol/L HEPES buffer, 25 μg/mL gentamicin, 1.5 g/L sodium bicarbonate, and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B. MIA PaCa-2 cells were grown in DMEM media. The human colon cancer cell line, HCT116, and the p53 knockdown (p53−/−) HCT116 cells were grown in McCoy's 5A media. Human glioma U87MG cells were cultured in EMEM supplemented with 1% non-essential amino acids. Human primary fibroblasts (IMR90), which were a gift from Dr. S. Lee (Harvard Cutaneous Biology Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charles Town, MA), were cultured in DMEM media.

Cell survival assay

The effects of the test compounds on human cancer cell viability, expressed as the percentage of cell survival, were determined with the use of the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Cells were grown in 96-well plates at 4 × 103 to 5 × 103 cells per well and exposed to different concentrations of the test compounds (0, 0.01, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5 or 10 μ mol/L). After incubation for 72 hr, 10 μL of the MTT solution (5 mg/mL; Sigma) were added into each well. The plates were incubated for 2-4 hr at 37°C. The supernatant was then removed and the formazan crystals were dissolved with 100 μL of DMSO. The absorbance at 570 nm was recorded using an OPTImax microplate reader (Molecular Devices). The cell survival percentages were calculated by dividing the mean OD of compound-containing wells by that of DMSO-containing control wells. Three separate experiments were accomplished to determine the half maximal inhibitory concentration values.

Cell proliferation assay

The effects of the compounds on cell proliferation were determined using the bromodeoxyuridine incorporation assay (Oncogene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, cells were seeded in 96-well plates (8 × 103 to 1.2 × 104 cells per well) and incubated with various concentrations of the makaluvamine analogs (0, 0.01, 0.1 and 1.0 μ mol/L) for 24 hr. Bromodeoxyuridine was added to the medium 10 hr before termination of the experiment. The bromodeoxyuridine incorporated into cells was determined by anti-bromodeoxyuridine antibody, and absorbance was measured at dual wavelengths of 450/540 nm using an OPTImax microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

Detection of apoptosis

Following a similar protocolas above, cells in early and late stages of apoptosis were detected using an Annexin V-FITC apoptosis detection kit from BioVision (Mountain View, CA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. For apoptosis experiments, 2 × 105 to 3 × 105 cells were exposed to the test compounds (0, 0.1 and 1.0 μ mol/L) and incubated for 48 hr prior to analysis. Cells were collected and washed with serum-free media. Cells were then re-suspended in 500 μL of Annexin V-binding buffer followed by addition of 5 μL of Annexin V-FITC and 5 μL of propidium iodide. The samples were incubated in the dark for 5 min at room temperature and analyzed with a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur instrument (excitation, 488 nm; emission, 530 nm). The cells that were positive for Annexin V-FITC alone (early apoptosis) and Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide (late apoptosis) were counted.

Cell cycle measurements

To determine the effects of the makaluvamine analogs on the cell cycle, a protocol similar to that described above was used. Cells (2 × 105 to 3 × 105) were exposed to the test compounds (0, 0.01, 0.1, and 1 μmol/L) and incubated for 24 hr prior to analysis. Cells were trypsinized, washed with PBS, and fixed in 1.5 mL of 95% ethanol at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with RNAse and staining with propidium iodide (Sigma). The DNA content was determined by flow cytometry.

Mouse xenograft model of human breast cancer

The animal use and care protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Female athymic pathogen-free nude mice (nu/nu, 4-6 weeks) were purchased from the Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center (Frederick, MD). To establish MCF-7 human breast cancer xenograft tumors, each of the female nude mice was first implanted with a 60-d s.c. slow release estrogen pellet (SE-121, 1.7 mg 17β-estradiol/pellet; Innovative Research of America). The following day, cultured MCF-7 cells were harvested from monolayer cultures, washed twice with serum-free medium, re-suspended and injected s.c. (5 × 106 cells, total volume 0.2 ml) into the left inguinal area of the mice. All animals were monitored for activity, physical condition, body weight, and tumor growth. Tumor size was determined every other day by caliper measurement of two perpendicular diameters of the implant. Tumor weight (in grams) was calculated by the formula, 1/2a × b2, which a is the long diameter and b is the short diameter (in centimeters).

In vivo chemotherapy

The animals bearing human cancer xenograft tumors were randomly divided into various treatment groups and a control group (5-10 mice/group). The untreated control group received the vehicle only. FBA-TPQ was dissolved in the vehicle, PEG400:ethanol:saline (57.1:14.3:28.6, volume for volume for volume), and was given i.p. at doses of 5 mg/kg/d, 3 days/wk for 3 wk, 10 mg/kg/d, 3 days/wk for 2 wk, or 20 mg/kg/d, 3 days/wk for 1 wk. Treatments in the 10 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg groups were halted early due to significant weight loss by the mice. At the end of the experiments, xenograft tumors were removed and homogenized, and the resulting supernatant was used for Western blot analysis of protein expression.

Western blot analysis

The protein levels in cell lysates and tissue homogenates were assessed using methods described previously (17, 18). In the in vitro studies, cells were exposed to various concentrations of FBA-TPQ for 24 h. For ATM, p-ATM and ATR, 3% to 8% NuPAGE Tris-acetate gels (Invitrogen) were used for proper separation of the proteins. Other Western blot experiments were carried out by regular SDS-PAGE. Cell lysates with identical amounts of protein were fractionated and transferred to Bio-Rad trans-Blot nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The nitrocellulose membrane was incubated in blocking buffer (Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat milk) for 1 hr at room temperature. Then the membrane was incubated with the appropriate primary antibody overnight at 4°C or 2 h at room temperature with gentle shaking. The membrane was washed three times with rinsing buffer (Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20) for 15 min and then incubated with goat anti-mouse/rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Bio-Rad) for 1 h at room temperature. After repeating the washes in triplicate, the protein of interest was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence reagents from PerkinElmer LAS, Inc.

Data and statistical analysis

Experimental data are expressed as means and standard deviations, and the significance of differences was analyzed by ANOVA or Student's t-test as appropriate.

Results

Initial screening for in vitro growth inhibition

The four compounds were first tested for their in vitro cytotoxicity using the MTT assay. Thirteen cell lines representing six types of human malignancies (breast, prostate, lung, pancreatic, colon and brain) and one “normal” (non-malignant) fibroblast cell line were cultured with test compounds at concentrations in the range of 0.01-10 μ mol/L for 72 hours, then cell viability was determined. The inhibitory effects of these compounds on cell growth are represented in Table 1. Of the four compounds, FBA-TPQ consistently showed greater activity in all of the cell lines. In general, the IMR90 cells were slightly less sensitive to compound than the other cells line. On the other hand, the breast cancer cell lines were the most sensitive to the compounds. For this reason, we further evaluated the activity of FBA-TPQ in comparison with the other three compounds in breast cancer cell lines.

Table 1.

Cell growth inhibitory activity of FBA-TPQ, PEA-TPQ, MPA-TPQ and DPA-TPQ in human cancer and normal cells

| Cell type | Cell line | IC50 (μmol/L)* |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FBA-TPQ | PEA-TPQ | MPA-TPQ | DPA-TPQ | ||

| Breast cancer | MCF-7 | 0.097 | 0.435 | 0.709 | 1.220 |

| MDA-MB-468 | 0.125 | 0.101 | 0.428 | 0.277 | |

| Prostate cancer | LNCaP | 1.290 | 1.742 | 3.959 | 24.451 |

| PC3 | 0.978 | 2.037 | 2.236 | 2.619 | |

| Lung cancer | A549 | 0.569 | 1.226 | 1.247 | 1.736 |

| H358 | 0.170 | 0.398 | 1.204 | 0.983 | |

| H838 | 0.110 | 0.260 | 0.665 | 0.838 | |

| H1299 | 0.968 | 1.708 | 2.478 | 2.524 | |

| Pancreatic cancer | HPAC | 0.535 | 1.131 | 2.920 | 2.852 |

| Panc-1 | 0.104 | 0.258 | 0.587 | 0.720 | |

| MIA-PaCa-2 | 0.315 | 0.982 | 2.740 | 1.320 | |

| Colon cancer | HCT116 | 1.474 | 2.545 | 4.865 | 2.765 |

| Glioma | U87MG | 1.420 | 1.978 | 2.993 | 1.675 |

| Fibroblast | IMR90 | 1.488 | 3.774 | 5.698 | 2.880 |

IC50, the concentration that inhibitscell growth by 50%.

Inhibition of cell proliferation by the compounds

In a dose-dependent manner, all four of the makaluvamine analogs inhibited cell proliferation (Fig. 1B). The anti-proliferative effects were seen in both MCF-7 (p53 wild type) and MDA-MB-468 (which are p53 mutant) cell lines. Again, FBA-TPQ was the most active compound in both cell lines, although the MCF-7 cells were more sensitive to the compound than the MDA-MB-468 cells, with three of the four compounds significantly decreasing proliferation at the 0.01 μ mol/L concentration in the MCF-7 cells.

Induction of apoptosis in human breast cancer cells

Because cell survival was dramatically reduced in all cell lines, but there were differences in the effects of the compounds on proliferation, we next evaluated whether the compounds induced apoptosis. As illustrated in Fig. 1C, all four of the compounds induced significant apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner in the MDA-MBA-468 cells. With regard to apoptosis, the MCF-7 cells were less sensitive, but all of the compounds except MPA-TPQ led to significant apoptosis at the 1 μ mol/L concentration. At 1 μ mol/L, FBA-TPQ showed more potent effects relative to the other compounds in both cell lines.

Effects of the makaluvamine analogues on cell cycle arrest

As in the case of apoptosis, the MDA-MB-468 cells were more sensitive to the effects of the compounds on cell cycle progression. The 1 μmol/L concentration of MPA-TPQ and DPA-TPQ induced a significant increase in the number of cells in the S phase (P < 0.05) as did FBA-TPQ and PEA-TPQ (P < 0.01). Even at the 0.1 μmol/L concentration, FBA-TPQ led to a significant (P < 0.05) increase in the number of cells in the S phase. FBA-TPQ was also the only compound that caused significant (P < 0.01) S-phase cell cycle arrest at the 1 μmol/L concentration in the MCF-7 cells (Table 2). In the MCF-7 cells, PEA-TPQ induced a significant increase in the number of cells in the G2-M phase (P < 0.01) at the 0.1 μmol/L concentration, and MPA-TPQ induced arrest in the G1 phase (P < 0.01; Table 2). The differences in the responses of the different cell lines may be related to their expression of p53.

Table 2.

Effects of FBA-TPQ, PEA-TPQ, MPA-TPQ and DPA-TPQ on the cell cycle progression of breast cancer cells.

| Test compounds | MCF-7 | MDA-MB-468 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Conc.(μM) | G1 | S | G2/M | G1 | S | G2/M |

| FBA-TPQ | 0 | 61.52±1.64 | 15.57±1.48 | 22.90±0.66 | 59.19±1.42 | 9.81±1.08 | 31.00±2.13 |

| 0.01 | 58.11±1.00 | 13.40±2.15 | 28.50±1.49 | 66.58±2.64 | 9.97±1.79 | 23.45±1.72 | |

| 0.10 | 62.49±3.48 | 14.39±0.85 | 23.12±2.88 | 66.36±1.88 | 11.46±2.69* | 22.18±2.96 | |

| 1.00 | 50.48±3.43 | 23.16±1.23† | 26.36±2.19 | 65.07±4.53 | 15.38±0.18† | 19.55±1.87 | |

| PEA-TPQ | 0 | 61.52±1.64 | 15.57±1.48 | 22.90±0.66 | 59.19±1.42 | 9.81±1.08 | 31.00±2.13 |

| 0.01 | 56.54±0.57 | 14.47±1.49 | 28.99±2.35† | 65.34±1.14 | 10.21±2.04 | 24.44±2.27 | |

| 0.10 | 56.63±1.35 | 14.38±2.97 | 28.99±1.06† | 68.17±2.54 | 10.43±2.15 | 21.40±3.64 | |

| 1.00 | 55.49±1.28 | 15.00±2.09 | 29.50±1.34† | 64.15±0.97 | 12.95±0.96† | 22.90±2.05 | |

| MPA-TPQ | 0 | 61.52±1.64 | 15.57±1.48 | 22.90±0.66 | 59.19±1.42 | 9.81±1.08 | 31.00±2.13 |

| 0.01 | 66.20±0.18† | 13.37±0.48 | 20.43±0.81 | 67.49±3.53 | 11.20±2.21 | 21.31±2.12 | |

| 0.10 | 67.94±1.20† | 14.15±0.15 | 17.91±3.00 | 65.74±0.83 | 11.53±1.22 | 22.73±2.05 | |

| 1.00 | 67.32±0.73† | 14.26±2.97 | 18.42±3.08 | 62.62±0.43 | 12.59±2.55* | 24.79±0.89 | |

| DPA-TPQ | 0 | 61.52±1.64 | 15.57±1.48 | 22.90±0.66 | 59.19±1.42 | 9.81±1.08 | 31.00±2.13 |

| 0.01 | 70.00±0.14 | 13.52±1.27 | 16.48±0.50 | 67.15±0.13 | 10.07±1.23 | 22.78±2.26 | |

| 0.10 | 68.41±4.97 | 14.17±1.79 | 17.42±0.30 | 65.57±1.93 | 10.40±1.07 | 24.04±0.71 | |

| 1.00 | 66.61±0.53 | 12.62±2.23 | 20.77±1.54 | 64.84±1.61 | 13.15±1.73* | 22.02±2.14 | |

P < 0.05.

P < 0.01 compared with the controls.

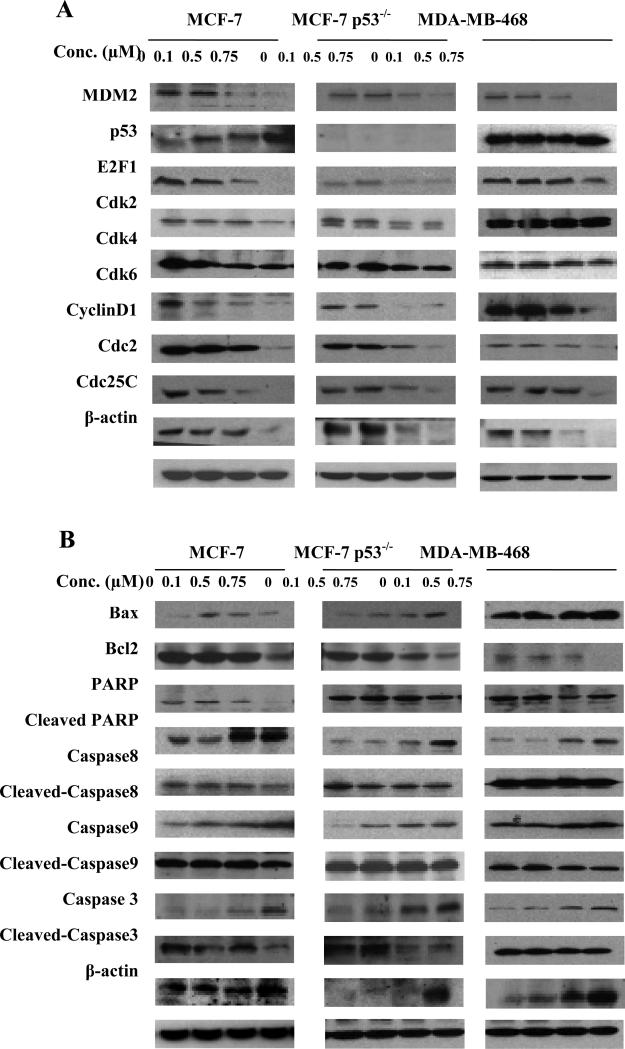

FBA-TPQ affects proteins associated with cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and the DNA damage response

We investigated the possible mechanisms responsible for the antiproliferative, proapoptotic, and cell cycle regulatory effects of FBA-TPQ by evaluating its effects on the expression level of various proteins involved in regulating cell cycle progression, apoptosis, and the response to DNA damage (Fig. 2A-C). In the MCF-7 cells, FBA-TPQ activated p53; increased the cleavage of PARP, Caspase-3, Caspase-8, and Caspase-9; activated ATM/p-ATM and ATR (at the lower concentrations); and led to increased phosphorylation of Chk1, Chk2, p53, and H2AX. The compound also down-regulated MDM2, E2F1, Cdk2, Cdk4, Cdk6, Cyclin D1, Cdc2, Cdc25c, and Bcl-2 (Fig. 2A and B). In the MCF-7 p53–/– cells and MDA-MB-468 (p53 mutant) cells, similar effects were observed for almost all of the proteins, indicating that FBA-TPQ can exert its effects via the DNA damage response and decreased cell cycle progression/increased apoptosis in a p53-independent manner (Figs. 2A and B, and 3A). To confirm these results, HCT116 cells with wild-type p53 expression or with p53 deleted were examined (Fig. 3B). Similar to the effects on breast cancer cells, in the p53 wild-type cells FBA-TPQ increased p53, and in both the wild-type and p53 knockdown (p53–/–) HCT116 cells, FBA-TPQ inhibited MDM2 and increased PARP cleavage.

Figure 2.

Effects of FBA-TPQ on the expression of proteins related to cell cycle progression and apoptosis in human breast cancer cells. MCF-7, MCF-7 p53 knockdown (MCF-7 p53−/−) and MDA-MB-468 breast cancer cells were exposed to several concentrations of the compound for 24 h; then target proteins related to cell cycle progression (A) or apoptosis (B) were examined by Western blotting.

Figure 3.

Effects of FBA-TPQ on the expression of proteins in human cancer cells. To further examine the mechanism(s) of action of the compound, the MCF-7, MCF-7 p53−/−, and MDA MB-468 cells were exposed to the compound for 24 h; then target proteins related to the DNA damage response were examined by western blotting (A). To confirm the effects observed in breast cancer cells, another pair of cells lines, human colon cancer HCT116 and p53 knockdown HCT116 (HCT116 p53−/−) cells were exposed to the compound and examined for expression of selected proteins by western blotting (B).

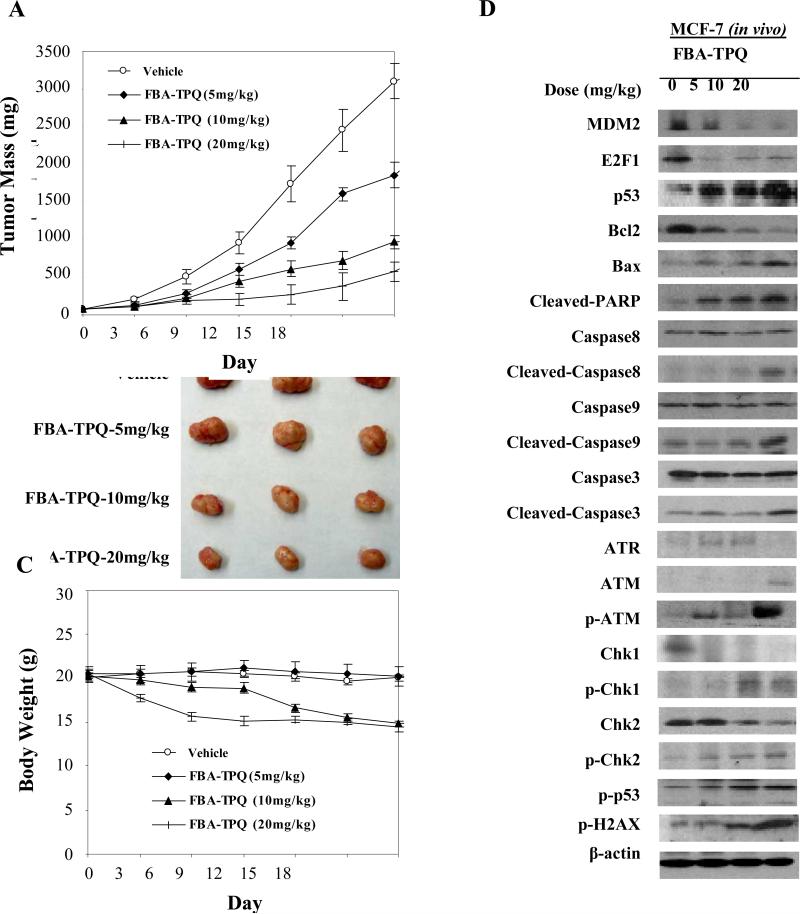

In vivo activity against human breast cancer xenograft tumors

After our observations of its potent in vitro effects, FBA-TPQ was evaluated in a mouse MCF-7 xenograft model of breast cancer. The compound was given at 5 mg/kg/d, 3 d/wk for 3 weeks; 10 mg/kg/d, 3 d/wk for 2 weeks; or 20 mg/kg/d, 3 d/wk for 1 week. The highest dose inhibited MCF-7 xenograft tumor growth by about 71.6% on day 18. Even the lowest (5 mg/kg) dose led to significant (36.2%; P < 0.001) tumor growth inhibition (Fig. 4A and B). There was no significant loss of body weight at the 5 mg/kg dose, although there was weight loss at the higher doses (Fig. 4C). Interestingly, the patterns of protein expression in the treated xenograft tumors were essentially the same as those observed in vitro (Fig. 4D). These data support that there are multiple pathways involved in the anticancer activity of this test compound, which may provide a basis for future biomarker and mechanistic studies of this class of compounds in both the preclinical and clinical settings.

Figure 4.

In vivo effects of FBA-TPQ given to nude mice bearing MCF-7 xenograft tumors. A, FBA-TPQ was given i.p. at doses of 5 mg/kg/d, 3 d/wk for 3 wk; 10 mg/kg/d, 3 d/wk for 2 wk; or 20 mg/kg/d, 3 d/wk for 1 wk; and tumors were measured every 3 d. At the end of the experiment, representative tumors were removed and photographed (B). Animals were also monitored for changes in body weight as a surrogate marker for toxicity (C). The expression of proteins from tumor homogenates was analyzed by western blotting (D).

Discussion

This study represents the first attempt to systematically evaluate the anticancer activities of novel synthetic makaluvamine analogues in in vitro and in vivo human cancer models. We have shown several important points: (a) the anticancer activity of the makaluvamine analogues is dose, structure, and cell type dependent; (b) although induction of apoptosis is the major mechanism responsible for the cytotoxicity of the compounds, antiproliferative and cell cycle inhibitory effects were also observed; (c) the most active compound, FBA-TPQ, activated p53 and regulated the expression of cell cycle–related, apoptosis-related, and DNA damage–related proteins, including MDM2, E2F1, Cdk2, Cdk4, Cdk6, Cyclin D1, Bcl-2, PARP, Caspase-3, Caspase-8, Caspase-9, ATM/p-ATM, ATR, p53/p-p53, and p-H2AX; (d) the anticancer activity was not dependent upon the p53 status of the cells; (e) FBA-TPQ decreased the growth of xenograft tumors in mice in a dose-dependent manner; and (f) similar changes in protein expression were observed in vitro and in vivo after exposure to FBA-TPQ.

The present data showed that there is a structure-activity relationship for the synthetic makaluvamine analogues. In general, for most cell lines, the order of activity was FBA-TPQ>PEA-TPQ>MPA-TPQ>DPA-TPQ. The compound FBA-TPQ consistently showed the best activity. The biological activities of the compound are apparently related to the types of modifications linked to the core structure. Because FBA-TPQ exerted the most potent effects, and DPA-TPQ and MPA-TPQ exerted lesser effects in all cell lines, it seems that a smaller side chain group may allow for enhanced activity of the compounds.

After evaluating the effects of the compounds on proliferation, apoptosis, and cell cycle progression, we concluded that apoptosis (likely as a result of the activation of the DNA damage response) was the main mechanism by which the compounds exert their effects. This is supported by the activation of several apoptosis-related proteins observed by western blotting. More importantly, the compounds were more cytotoxic to the cancer cell lines examined than to the primary fibroblasts. This suggests that the compound may preferentially induce apoptosis in cancer cells.

After our observation that FBA-TPQ exerted potent in vitro effects against breast cancer cells, we initiated an in vivo study to determine whether the compound could inhibit tumor growth in a MCF-7 xenograft model of breast cancer. A dose of 5 mg/kg given 3 d/wk led to nearly 40% tumor growth inhibition. Future pharmacokinetic studies of this compound, compared with its analogues, are warranted to determine whether the toxicity noted in the mice receiving the higher doses can be prevented by using a different formulation or route of administration.

Of note, human cancer cell lines were responsive to the compounds regardless of their p53 status, exhibiting decreases in survival and proliferation, and increases in apoptosis and cell cycle arrest regardless of their genotype. The activation of p53 is a major mechanism of action for many DNA-damaging agents, including irradiation and most of the chemotherapeutic agents used in the clinic. Therefore, cancers with nonfunctional p53 are often unresponsive to conventional DNA-damaging therapies. Because approximately half of human cancers lack functional p53, compounds that can target both p53 wild-type and mutant/null cells are of particular interest. Thus, our results indicate that FBA-TPQ and its analogues may be used against a broad spectrum of cancers with different p53 status. In support of this, additional cell lines with p53 knocked out also responded to treatment with FBA-TPQ.

Given the inhibitory effects on the proliferation and induction of apoptosis in all of the cell lines and the increase in p53 in the p53 wild-type cells, it is possible that the down-regulation of the MDM2 oncoprotein is, at least in part, responsible for the observed cytotoxic effects of FBA-TPQ. We and others have previously shown that MDM2 inhibition results in increased p53, decreased E2F1, decreased cell survival and proliferation, induction of cell cycle arrest, and an increase in apoptosis as well as in vivo antitumor effects (19, 20). Moreover, MDM2 has numerous p53-independent effects that can be targeted for cancer therapy (21).

Although the precise mechanism(s) of action of the compounds have yet to be elucidated, we have shown that their activity was associated with pathways involved in cell proliferation, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, and the DNA damage response. We speculate that there are three major pathways involved: tumor suppressor activation, oncogene inhibition, and the DNA damage response. At present, it is unclear why the expression of Ataxia telangiectasi and Rad3 related is increased by the lower concentrations/doses of FBA-TPQ but decreased at the highest levels (0.75 μmol/L; 20 mg/kg). It is possible that there is feedback inhibition, or it may be that the length of time that the cells/tumors were exposed to the compound was enough to induce recovery from the damage (supported by the high level of p-H2AX observed at these doses; ref. 22). Detailed investigations into the mechanism(s) of action will be carried out in future studies.

With respect to the potency of the compounds, our in vitro and in vivo results indicate that the concentration of compound necessary to produce anticancer activities, as illustrated by cell cytotoxicity assays, apoptosis assays, in vivo studies, and the effects on protein expression, is much lower than that of most reported natural products with shown chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic activities (23).

In conclusion, we have synthesized several makaluvamine analogues and have shown that they have broad-spectrum anticancer activity. Further molecular, pharmacologic, and toxicologic studies are needed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of action and to determine the optimal dose, route, and formulation for administering FBA-TPQ. These studies are important for further preclinical and clinical development of this class of compounds.

Statement of Translational Relevance.

There is an urgent need to develop novel agents for human cancer therapy. Although the mortality rate for breast cancer patients has decreased, new therapies are still urgently needed, especially for patients who are ER/PR/Her2 negative. We have recently generated a number of novel synthetic analogs of the marine-derived makaluvamine compounds. These synthetic compounds represent a new generation of anti-cancer agents and have high potency against several cancers, including breast cancer. In the present study, we demonstrated that all four of the novel compounds evaluated, but particularly 7-(4-fluorobenzylamino)-1,3,4,8-tetrahydropyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinolin-8(1H)-one, exerted potent in vitro and in vivo anti-cancer activities against models of human breast cancer. These data provide a basis for future pharmacology and toxicology studies and clinical trials of these agents. Although further investigation is needed, our data indicate that the synthetic makaluvamine analogs could potentially improve patient survival by providing a new chemotherapeutic agent for breast cancers. These results may also help determine the effects of the new compounds in other types of human cancers in the future.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Robert B. Diasio, Wayne J. Brouillette, and Hui Wang for their helpful discussion; and Drs. Mao Li, Feng Wang, Gu Jing, and Deng Chen, and Ms. Charri J. Ezell for their excellent technical assistance.

Grant Support: This work was supported by NIH grants R01 CA112029 and R01 CA121211 and by NCI CA13148-35/UAB Comprehensive Cancer Center Collaborative Programmatic Development Grant Program (CPDG08–09). E. Rayburn was supported by a DoD grant (W81XWH-06-1-0063) and a T32 fellowship from the NIH/UAB Gene Therapy Center (CA075930). The apoptosis analyses were performed by the Flow Cytometry Core of the Arthritis and Musculoskeletal Center, which is supported in part by an NIH grant (P60 AR20614). S. E. Velu was supported by a UAB Breast Spore pilot grant and a translational research grant from the UAB Council of University-Wide Interdisciplinary Research Centers.

Abbreviations

- FBA-TPQ

7-(4-fluorobenzylamino)-1,3,4,8-tetrahydropyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinolin-8(1H)-one

- PEA-TPQ

7-(phenethylamino)-1,3,4,8-tetrahydro-pyrrolo[4,3,2-de]-quinolin-8(1H)-one

- MPA-TPQ

7-(3,4-methylenedioxyphenethylamino)-1,3,4,8-tetrahydropyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinolin-8(1H)-one

- DPA-TPQ

7-(3,4-dimethoxyphenethylamino)-1,3,4,8-tetrahydropyrrolo[4,3,2-de]quinolin-8(1H)-one

- SAR

structure-activity relationship

References

- 1.Blunt JW, Copp BR, Munro MH, Northcote PT, Prinsep MR. Marine natural products. Nat Prod Rep. 2005;22:15–61. doi: 10.1039/b415080p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sipkema D, Franssen MC, Osinga R, Tramper J, Wijffels RH. Marine sponges as pharmacy. Mar Biotechnol. 2005;7:142–62. doi: 10.1007/s10126-004-0405-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beneteau V, Besson T. Synthesis of novel pentacyclic pyrrolothiazolobenzoquinolinones, analogs of natural marine alkaloids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001;42:2673–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beneteau V, Pierre A, Pfeiffer B, Renard P, Besson T. Synthesis and antiproliferative evaluation of 7-aminosubstituted pyrroloiminoquinone derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2000;10:2231–4. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(00)00450-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kokoshka JM, Capson TL, Holden JA, Ireland CM, Barrows LR. Differences in the topoisomerase I cleavage complexes formed by camptothecin and wakayin, a DNA-intercalating marine natural product. Anticancer Drugs. 1996;7:758–65. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199609000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Legentil L, Benel L, Bertrand V, Lesur B, Delfourne E. Synthesis and antitumor characterization of pyrazolic analogues of the marine pyrroloquinoline alkaloids: wakayin and tsitsikammamines. J Med Chem. 2006;49:2979–88. doi: 10.1021/jm051247f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Legentil L, Lesur B, Delfourne E. Aza-analogues of the marine pyrroloquinoline alkaloids wakayin and tsitsikammamines: synthesis and topoisomerase inhibition. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:427–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao R, Oreski B, Lown JW. Synthesis and biological evaluation of hybrid molecules containing the pyrroloquinoline nucleus and DNA-minor groove binders. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1996;6:2169–72. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antunes EM, Copp BR, Davies-Coleman MT, Samaai T. Pyrroloiminoquinone and related metabolites from marine sponges. Nat Prod Rep. 2005;22:62–72. doi: 10.1039/b407299p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ding Q, Chichak K, Lown JW. Pyrroloquinoline and pyridoacridine alkaloids from marine sources. Curr Med Chem. 1999;6:1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urban S, Hickford SJH, Blunt JW, Munro MHG. Bioactive Marine Alkaloids. Curr Org Chem. 2000;4:765–807. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Radisky DC, Radisky ES, Barrows LR, Copp BR, Kramer RA, Ireland CM. Novel cytotoxic topoisomerase II inhibiting pyrroloiminoquinones from Fijian sponges of the genus Zyzzya. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:1632–8. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Velu SE, Pillai SK, Lakshmikantham MV, Billimoria AD, Culpepper JS, Cava MP. Efficient Syntheses of the Marine Alkaloids Makaluvamine D and Discorhabdin C: The 4,6,7-Trimethoxyindole Approach. J Org Chem. 1995;60:1800–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shinkre BA, Raisch KP, Fan L, Velu SE. Analogs of the marine alkaloid makaluvamines: synthesis, topoisomerase II inhibition, and anticancer activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:2890–3. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.02.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dijoux MG, Schnabel PC, Hallock YF, et al. Antitumor activity and distribution of pyrroloiminoquinones in the sponge genus Zyzzya. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13:6035–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shinkre BA, Raisch KP, Fan L, Velu SE. Synthesis and Antiproliferative Activity of Benzyl and Phenethyl Analogs of Makaluvamines. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:2541–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang H, Cai Q, Zeng X, Yu D, Agrawal S, Zhang R. Anti-tumor activity and pharmacokinetics of a mixed-backbone antisense oligonucleotide targeted to RIα subunit of protein kinase A after oral administration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13989–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Yu D, Agrawal S, Zhang R. Experimental therapy of human prostate cancer by inhibiting MDM2 expression with novel mixed-backbone antisense oligonucleotides: In vitro and in vivo activities and mechanisms. Prostate. 2003;54:194–205. doi: 10.1002/pros.10187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Z, Wang H, Li M, Rayburn ER, Agrawal S, Zhang R. Stabilization of E2F1 protein by MDM2 through the E2F1 ubiquitination pathway. Oncogene. 2005;24:7238–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Z, Li M, Wang H, Agrawal S, Zhang R. Antisense therapy targeting MDM2 oncogene in prostate cancer: Effects on proliferation, apoptosis, multiple gene expression, and chemotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11636–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Z, Zhang R. p53-independent activities of MDM2 and their relevance to cancer therapy. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2005;5:9–20. doi: 10.2174/1568009053332618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu X, Nguyen TA, Donehower LA. Reversal of the ATM/ATR-mediated DNA damage response by the oncogenic phosphatase PPM1D. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1060–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li M, Zhang Z, Hill D, Chen X, Wang H, Zhang R. Genistein, a dietary isoflavone, down-regulates the MDM2 oncogene at both transcriptional and posttranslational levels. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8200–08. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]