Abstract

BACKGROUND

Dietary sodium indiscretion frequently contributes to hospitalizations in elderly heart failure patients. Animal models suggest an important role for dietary sodium intake in the pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved systolic function. The documentation and effects of hospital discharge recommendations, particularly for sodium-restricted diet, have not been extensively investigated in heart failure with preserved systolic function.

METHODS

We analyzed 1700 heart failure admissions to Michigan community hospitals. We compared documentation of guideline-based discharge recommendations between preserved systolic function and systolic heart failure patients with chi-squared testing, and used logistic regression to identify predictors of 30-day death and hospital readmission in a prespecified follow-up cohort of 443 patients with preserved systolic function. We hypothesized that patients who received a documented discharge recommendation for sodium-restricted diet would have lower 30-day adverse event rates.

RESULTS

Heart failure patients with preserved systolic function were significantly less likely than systolic heart failure patients to receive discharge recommendations for weight monitoring (33% vs 43%) and sodium-restricted diet (42% vs 53%). Upon propensity score-adjusted multivariable analysis, patients with preserved systolic function who received a documented sodium-restricted diet recommendation had decreased odds of 30-day combined death and readmission (odds ratio 0.43, 95% confidence interval, 0.24–0.79; P = .007). No other discharge recommendations predicted 30-day outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Clinicians document appropriate discharge instructions less frequently in heart failure with preserved systolic function than systolic heart failure. Selected heart failure patients with preserved systolic function who receive advice for sodium-restricted diet may have improved short-term outcomes after hospital discharge.

Keywords: Diastolic heart failure, Dietary salt, Discharge recommendations, Normal ejection fraction, Outcomes, Performance measures

Heart failure with preserved systolic function accounts for over 50% of hospital admissions for heart failure in patients over age 65 years.1 Nearly half of discharged patients are readmitted within 6 months, with 40% 343of these for repeat heart failure exacerbations.2 In an effort to improve postdischarge outcomes, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA) have developed hospital performance measures that include the documentation of dietary recommendations and other appropriate heart failure discharge instructions.3

Many early rehospitalizations in elderly heart failure patients follow dietary sodium indiscretion.4,5 In hypertensive animal models and susceptible humans, high dietary sodium intake contributes to structural and physiological changes that are implicated in the pathophysiology of heart failure with preserved systolic function.6–14 Current guidelines recommend sodium-restricted diet for all symptomatic heart failure patients.15,16 No previous studies have reported on the documentation and effects of a hospital discharge recommendation for sodium-restricted diet in patients with preserved systolic function.

We explored 2 specific hypotheses in a heart failure population discharged from 14 Michigan community hospitals. First, we predicted that clinicians document appropriate discharge instructions less frequently in heart failure with preserved systolic function than systolic heart failure.17 Secondly, we hypothesized that patients with preserved systolic function who received a documented discharge recommendation for sodium-restricted diet would have lower odds of 30-day death and hospital readmission than those who did not receive this recommendation.

METHODS

Overview of GAP-HF

The Mid-Michigan Guidelines Applied in Practice - Heart Failure (GAP-HF) study was a collaborative effort between the Greater Flint Health Coalition, the Michigan Peer Review Organization (affiliated with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services), and the Michigan Chapter of the ACC to increase adherence to inpatient heart failure performance measures.3,15 A prespecified secondary aim was to investigate the effects of hospital discharge recommendations, including sodium-restricted diet, on short-term outcomes in patients with Medicare or Medicaid as the primary insurance payer.

In GAP-HF, 8 “intervention” Michigan community hospitals developed an ACC/AHA guideline-based “tool kit” to improve performance measure adherence. Six other Michigan community hospitals, matched by number of beds, participated as a control group. Each facility was assessed over 2 6-month intervals: one before (October 1, 2002-March 31, 2003) and one after the intervention hospitals adopted the quality improvement program (January 1–June 30, 2004). Each intervention hospital had the opportunity to develop a template-based, heart failure-specific discharge form. However, locally developed forms were already in use in all intervention hospitals and 5 of 6 control hospitals before GAP-HF.

For intervention hospitals, all patients with a primary heart failure discharge diagnosis were evaluated. For control hospitals with fewer than 110 heart failure discharges during the assessment period, all subjects were included; otherwise, 110 were randomly selected. All patient data from the index hospitalization were manually abstracted from hospital charts by DynKePRO (York, Penn), a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services Clinical Data Abstraction Center with previously validated high accuracy and reliability.18 The dates of hospital readmission and the number of hospitalizations within the 12 months before the index admission (both all-cause) were obtained for patients with Medicare and Medicaid as primary payer through the Michigan Peer Review Organization. Mortality data were obtained from the Social Security Death Index at least 1 year after discharge.

Selection of Study Subjects and Description of Variables Analyzed

We defined “preserved systolic function” as left ventricular ejection fraction (by echocardiography, nuclear scintigraphy, or contrast ventriculography) ≥50% and systolic dysfunction as ejection fraction <40%, and excluded patients without numerical ejection fraction assessment or ejection fraction between 40% and 49%.19 We also excluded patients with known moderate or severe aortic or mitral stenosis. We defined coronary artery disease as prior history or the occurrence of myocardial infarction or revascularization procedures during the index admission, and atrial fibrillation as prior history or occurrence during the index admission. Patient race was analyzed as “Caucasian” or “other.”

We examined the documentation of individual and “complete” ACC/AHA discharge recommendations in patients who were discharged home from the index admission. The 6 components of complete instructions are: written discharge medication list, recommended activity level, scheduled follow-up appointment, action plan if symptoms worsen, instructions for weight monitoring, and recommended diet.3 We defined sodium-restricted diet as any specific recommendation for dietary intake of 3 g or less of sodium per day, or any documented recommendation to eat a “low sodium” or “no sodium” diet without specific mention of sodium quantity. We classified all other subjects as not having received sodium-restricted diet instructions. The GAP-HF study was not intended to assess discharge education beyond documentation of discharge instructions, and information about the format, length, or intensity of discharge education for sodium-restricted diet was not collected.

Statistical Analysis

We performed all analyses with STATA version 10.0 (Stata-Corp LP, College Station, Tex). We report mean (SD) for continuous and number (%) for categorical variables. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. We compared patient characteristics and discharge recommendation documentation between heart failure with preserved systolic function and systolic heart failure with Pearson chi-squared or 2-tailed independent sample t testing where appropriate. We used logistic regression to determine univariable and multivariable predictors of combined death and readmission and readmission alone at 30 days postdischarge in the follow-up cohort with preserved systolic function. We performed identical exploratory analyses in the systolic heart failure cohort.

We used the previously validated Enhanced Feedback For Effective Cardiac Treatment (EFFECT) composite score (Table 1),20 and the number of hospitalizations within the previous year (a strong and “dose-dependent” predictor of adverse events in heart failure21,22) to adjust for individual patient risk of death and readmission. We divided patients into categories of 0, 1, 2 or 3, and 4 or more hospitalizations within the 12 months before the index admission. The multivariable outcome models included these clinical factors: sex, race, the 30-day EFFECT score, number of prior hospitalizations, atrial fibrillation, and coronary artery disease.1,20–23 We adjusted for baseline or remeasurement GAP-HF time period, and intervention or control hospital group, and then added sodium-restricted diet documentation to the model.

Table 1.

EFFECT Model* Score Components

| Variable | 30-day EFFECT Score† |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | +Age (in years) |

| Respiratory rate (breaths/min) | +Rate (in breaths/min) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | |

| ≥180 | −60 |

| 160–179 | −55 |

| 140–159 | −50 |

| 120–139 | −45 |

| 110–119 | −40 |

| 90–99 | −35 |

| <90 | −30 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL, maximum 60) | +Level (in mg/dL) |

| Serum sodium <136 mg/dL | +10 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | +10 |

| Dementia | +20 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | +10 |

| Hepatic cirrhosis | +25 |

| Cancer | +15 |

EFFECT = enhanced feedback for effective cardiac treatment.

Adapted from Lee et al. JAMA. 2003;290:2581–2587.20

Copyright © 2003 American Medical Association, All rights reserved.

Calculated as age + respiratory rate + systolic blood pressure points + blood urea nitrogen (≤60) + serum sodium points + cerebrovascular disease points + dementia points + chronic obstructive pulmonary disease points + hepatic cirrhosis points + cancer points.

Because sodium-restricted diet documentation was non-randomized, we calculated a focused propensity score24 using logistic regression. This method uses measured variables to predict treatment group assignment. We selected the following variables a priori24 as likely to affect sodium-restricted diet documentation: age, sex, race, hospital site, intervention vs control, and pre- vs postintervention hospital group, presence of a heart failure-specific discharge form in the chart, number of hospital admissions within the preceding 12 months, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, blood urea nitrogen, hospital length of stay, need for loop diuretic at hospital discharge, and admission history of heart failure, hypertension, or dementia. Using the propensity score, we then adjusted the 30-day outcome models for the likelihood of sodium-restricted diet documentation.

RESULTS

Study Population

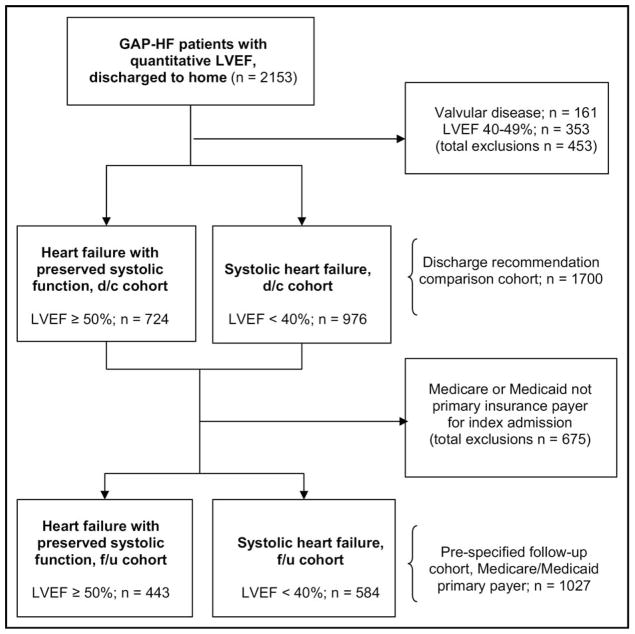

A total of 2153 patients with ejection fraction assessment were discharged home from their index admission. After exclusion of subjects with known valvular disease or ejection fraction between 40% and 49% (n = 453), 724 had heart failure with preserved systolic function and 976 had systolic heart failure. We compared discharge recommendation documentation between these groups. In the pre-specified follow-up cohort (see “Overview of GAP-HF” above and Figure 1), we analyzed 443 preserved systolic function and 584 systolic heart failure patients with Medicare or Medicaid as the primary insurance payer. The baseline characteristics of the overall and follow-up cohorts were generally similar (Table 2). As shown by others,1,25 patients with preserved systolic function were older, more obese, more often female, and had less known coronary artery disease and higher prevalence of hypertension than patients with systolic heart failure.

Figure 1.

Patient selection for analyses. GAP-HF = Mid-Michigan Guidelines Applied in Practice - Heart Failure study; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; d/c cohort = discharge recommendation comparison cohort; f/u cohort = prespecified follow-up cohort.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Subjects

| Variables | Systolic Heart Failure (Overall) (n = 976) | Systolic Heart Failure (Follow-up) (n = 584) | Heart Failure with Preserved Systolic Function (Overall) (n = 724) | Heart Failure with Preserved Systolic Function (Follow-up) (n = 443) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 69 ± 14 | 75 ± 10* | 72 ± 12† | 75 ± 10* |

| Sex (% female) | 40 | 40 | 64† | 66‡ |

| Race (% white) | 71 | 77 | 77† | 80 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29.2 ± 7.6 | 28.3 ± 6.9 | 32.7 ± 9.4† | 31.8 ± 8.7‡ |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 25 ± 8 | 25 ± 8 | 60 ± 8† | 60 ± 8‡ |

| History of: | ||||

| Heart failure (%) | 84 | 88 | 73† | 75‡ |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 72 | 80 | 57† | 59‡ |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 25 | 29 | 26 | 29 |

| Hypertension (%) | 77 | 79 | 84† | 85‡ |

| Diabetes mellitus (%) | 45 | 46 | 53† | 50 |

| COPD | 45 | 44 | 50† | 52‡ |

| Admission systolic BP (mm Hg) | 143 ± 33 | 140 ± 31 | 156 ± 33† | 156 ± 33‡ |

| Admission diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 80 ± 21 | 77 ± 19 | 77 ± 20† | 77 ± 20 |

| Admit heart rate (beats per minute) | 90 ± 22 | 87 ± 22 | 85 ± 21† | 83 ± 20‡ |

| Peripheral edema on examination (%) | 72 | 73 | 81† | 80‡ |

| Radiographic pulmonary edema (%) | 67 | 67 | 68 | 66 |

| Laboratory studies at admission | ||||

| Serum creatinine | 1.7 ± 1.4 | 1.7 ± 1.4 | 1.8 ± 1.7 | 1.7 ± 1.6 |

| Serum sodium | 137.3 ± 4.4 | 137.4 ± 4.3 | 137.7 ± 4.2† | 137.6 ± 4.2 |

| Serum hemoglobin | 12.5 ± 2.1 | 12.4 ± 2.0 | 11.9 ± 2.0† | 11.8 ± 1.9‡ |

Continuous variables are presented as means ± SD.

Abbreviations: BP = blood pressure; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Denotes significant (P <.05) difference between overall and analyzed population.

Denotes significant (P <.05) difference between systolic heart failure and heart failure with preserved systolic function in overall population.

Denotes significant (P <.05) difference between systolic heart failure and heart failure with preserved systolic function in analyzed population.

Hospital Discharge Instructions in Heart Failure with Preserved Systolic Function and Systolic Heart Failure

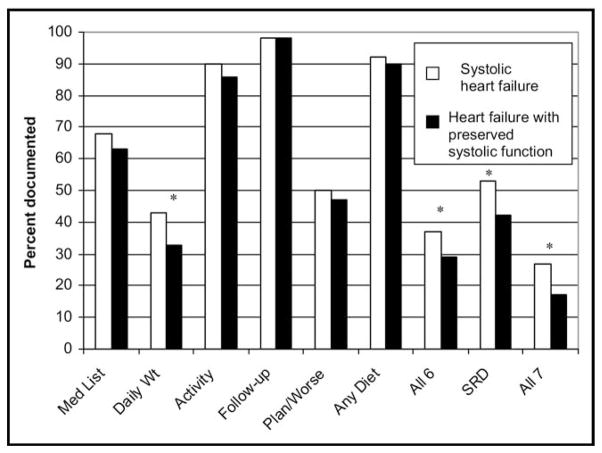

Patients with preserved systolic function received documented instructions for weight monitoring less often than systolic heart failure patients (33% vs 43%, P = .001), and hence, less frequently received complete ACC/AHA discharge recommendations (29% vs 37%, P = .006). Documentation of any form of dietary advice was similar between groups (90% vs 92%, P = .29), but patients with preserved systolic function were less likely to receive instructions to restrict dietary sodium (42% vs 53%, P = .001). Complete discharge instructions, when defined as including sodium-restricted diet, were infrequently documented in both groups and again less often in heart failure with preserved systolic function (17% vs 27%, P <.001; Figure 2). We found no differences between groups in appropriate anticoagulation for atrial fibrillation (58% vs 59%, P = .86) or the documentation of smoking cessation advice (60% vs 59%, P = .83). Heart failure-specific discharge forms were used similarly often in both groups (27% vs 32%, P = .12).

Figure 2.

Comparison of ACC/AHA (American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association) discharge recommendation documentation by heart failure type. Med List = written medication list; Daily Wt = daily weights; Plan/Worse = plan if symptoms worsened; All 6 = all 6 standard ACC/AHA discharge recommendations; SRD = sodium-restricted diet; All 7 = all standard ACA/AHA discharge recommendations plus sodium-restricted diet.

*Denotes significant (P <.02) intergroup difference.

Patients with preserved systolic function who received sodium-restricted diet recommendation were less likely than those who did not to have diabetes mellitus (44% vs 55%, P = .02), and had higher discharge loop diuretic mean daily dose (59 mg furosemide equivalent vs 46 mg, P = .003), but were otherwise clinically similar. The propensity score model yielded a C-statistic of 0.74; the strongest predictor of sodium-restricted diet documentation was the presence of a heart failure-specific discharge form (odds ratio [OR] 3.97, 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.25–4.84; P <.001), but 36% of patients with such a form in their chart still did not receive documented advice for sodium-restricted diet.

Predictors of 30-day Outcomes in Heart Failure with Preserved Systolic Function

In the follow-up cohort, 91/443 heart failure patients with preserved systolic function (21%) were rehospitalized or died within 30 days after discharge home; 28/91 (31%) received discharge advice for sodium-restricted diet as compared with 160/352 (46%) of those who did not die or get readmitted. A documented sodium-restricted diet recommendation significantly reduced the odds of 30-day death or readmission (OR 0.53, 95% CI, 0.33–0.87; P = .01; Table 3). None of the other discharge recommendations predicted 30-day outcomes on a univariable basis.

Table 3.

Factors Predicting 30-day Postdischarge Events in Heart Failure with Preserved Systolic Function Cohort

| Univariable 30-day Mortality or Readmission (n = 91/443) OR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted 30-day Mortality or Readmission (n = 87/428) OR (95% CI) | P Value | Adjusted 30-day Readmission Only (n = 84/428) OR (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFFECT score (per 10 points) | 1.17 (1.04–1.29) | .006 | 1.12 (.99–1.27) | .07 | 1.10 (.97–1.24) | .16 |

| Number of hospital admissions in previous 12 months | ||||||

| 0 (reference) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||

| 1–2 | 3.70 (1.82–7.52) | <.001 | 4.09 (1.90–8.83) | <.001 | 4.74 (2.17–10.34) | <.001 |

| 3 | 4.04 (2.17–7.51) | <.001 | 3.45 (1.76–6.79) | <.001 | 4.10 (2.06–8.19) | <.001 |

| 4 or more | 6.35 (3.25–12.4) | <.001 | 7.28 (3.50–15.17) | <.001 | 8.83 (4.16–18.70) | <.001 |

| Female (vs male) sex | .81 (.50–1.31) | .40 | .65 (38–1.14) | .13 | .65 (.34–1.04) | .07 |

| Non-white (vs white) race | 1.23 (.67–2.23) | .50 | 1.65 (.83–3.29) | .15 | 1.81 (.89–3.67) | .10 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.58 (.99–2.51) | .06 | 1.28 (.75–2.18) | .37 | 1.21 (.70–2.09) | .49 |

| Coronary artery disease | 1.01 (.63–1.62) | .97 | 1.01 (.59–1.72) | .97 | 1.07 (.62–1.84) | .81 |

| Recommendation for sodium-restricted diet | .53 (.33–.87) | .01 | .43 (.24–.79) | .007 | .46 (.25–.84) | .01 |

Abbreviations: OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; EFFECT = enhanced feedback for effective cardiac treatment. Model also adjusted for baseline or remeasurement cohort status and intervention or control hospital group, and propensity score for prescription of sodium-restricted diet (see text).

Of the 443 patients with preserved systolic function, 428 (97%) had complete data on all analyzed variables; 87 were rehospitalized or died within 30 days of discharge (84 readmissions, 10 deaths). The results of the propensity-adjusted multivariable models for 30-day outcomes in this cohort are shown in Table 3. A documented discharge recommendation for sodium-restricted diet was independently associated with decreased odds of combined 30-day death and readmission (OR 0.43, 95% CI, 0.24–0.79; P = .007) and 30-day readmission alone (OR 0.46, 95% CI, 0.25–0.84; P = .01).

The sodium-restricted diet recommendation predicted events with similar effect size and remained significant when the cohort was restricted to patients aged 65 and over, during both the “baseline” and “postintervention” periods of the GAP-HF study, regardless of whether or not patients had a heart failure-specific discharge form in their chart, and when EFFECT model components were included individually. The 6 standard ACC/AHA discharge recommendations did not predict 30-day event rates, either individually or as a “complete” set, when sodium-restricted diet was replaced in the multivariable models by each of the other measures in turn. None of the discharge recommendations, including sodium-restricted diet, predicted 30-day outcomes in the systolic heart failure cohort.

DISCUSSION

Over one fifth of patients hospitalized for decompensated heart failure with preserved systolic function die or are readmitted within 30 days of discharge. Our study demonstrates a discrepancy of care between systolic heart failure and heart failure with preserved systolic function that could potentially affect these short-term outcomes. We noted that heart failure patients with preserved systolic function had poorer chart documentation of guideline-based discharge recommendations than patients with systolic heart failure. We also found that a documented discharge recommendation for sodium-restricted diet, a simple and noncostly intervention, was independently associated with lower odds of 30-day death or readmission in patients with preserved systolic function.

One prior analysis of elderly heart failure inpatients suggested that up to half of rehospitalizations could be prevented by nonpharmacological means.4 Although intensive discharge education and outpatient support can decrease adverse events in elderly heart failure patients,26,27 postdischarge care begins with appropriate hospital discharge instructions. Patient self-care measures such as daily weight monitoring and sodium-restricted diet are nonpharmacological cornerstones of heart failure outpatient management, yet in GAP-HF were less frequently recommended in heart failure with preserved systolic function than systolic heart failure. Our findings complement those of the EuroHeart Failure Survey, in which postdischarge heart failure patients with preserved systolic function were less likely than systolic heart failure patients to recall being told to follow sodium-restricted diet or weigh themselves regularly.28 These results suggest that clinicians view the importance of hospital discharge recommendations differently between these groups. Providers might be unaware that these guidelines apply to patients with preserved systolic function or might be unconvinced of their effectiveness.17

Indeed, prior studies of guideline-based heart failure hospital discharge recommendations have not consistently suggested benefit.17,29,30 However, these have not extensively examined differences in documentation or effects between systolic heart failure and heart failure with preserved systolic function. In addition, previous work has reported on documentation of discharge dietary advice without considering the specific dietary recommendations provided.17,29,30 Dietary sodium indiscretion frequently occurs before heart failure hospitalizations, particularly in elderly patients,4,5 and current guidelines recommend sodium-restricted diet for all symptomatic heart failure patients.15,16 Some question this approach, noting increased neurohormonal levels and adverse outcomes in well-compensated systolic heart failure patients following sodium-restricted diet.31 However, there are reasons to believe that the response to sodium-restricted diet in heart failure with preserved systolic function may differ from systolic heart failure.

Animal models suggest that dietary sodium intake specifically contributes to the development and exacerbation of heart failure with preserved systolic function. In the Dahl S (salt-sensitive) rat, the primary animal model for heart failure with preserved systolic function, high sodium intake causes hypertension, ventricular and vascular stiffening, adverse renal remodeling, and subsequent heart failure.7 Target organ damage is caused by oxidative stress, local neurohormonal upregulation, and vascular inflammation in the heart and kidney that are induced by high sodium intake.6

Interestingly, the risk factors for human blood pressure salt sensitivity match the demographics of heart failure with preserved systolic function, namely advanced age, hypertension, renal insufficiency, obesity/metabolic syndrome, and the postmenopausal state.32 In salt-sensitive humans, chronically high dietary sodium intake is associated with hypertension, ventricular hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction, and arterial stiffening,12–14 factors that are highly prevalent in heart failure with preserved systolic function and implicated in its pathophysiology. Short-term dietary sodium loading in salt-sensitive humans causes endothelial dysfunction,8 altered neurohormonal responses,9 oxidative stress,11 and increased plasma volume.10 Through effects on preload, afterload, or ventriculovascular coupling, such changes could contribute to heart failure decompensa-tion.33,34 The neurohormonal and functional aspects of changes in dietary sodium intake have not yet been directly explored in heart failure with preserved systolic function.

Study Limitations

We obtained data by chart abstraction, and could not investigate nondocumented patient discharge education, patient adherence to discharge recommendations, or other aspects of outpatient management. While these are important limitations, our hypothesis-generating results highlight the need for further prospective studies that assess the effects of sodium-restricted diet education and adherence in heart failure patients. These investigations are particularly important in the heart failure population with preserved systolic function, for which there are currently no specific evidence-based therapies.15,16

Hospital readmission data were available only for a pre-specified cohort of patients with Medicare or Medicaid as the primary insurance payer. The clinical characteristics of this group were very similar to the overall GAP-HF population. Nonetheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that selection bias affected our results. We could not perform hierarchical analysis to adjust for potential clustering effects due to the small number of GAP-HF hospital sites.

We used propensity scoring to control for measured variables that we judged likely to affect the probability of documenting sodium-restricted diet. We recognize that documentation of sodium-restricted diet might serve as a marker for unmeasured factors that affect outcomes, such as higher-quality overall heart failure care. However, other than assessment of ejection fraction and appropriate discharge instructions, there are currently no quality measures specific to heart failure with preserved systolic function.3,15

CONCLUSIONS

Appropriate guideline-based discharge recommendations are frequently not provided to community hospital heart failure inpatients, particularly those with preserved systolic function. In selected heart failure patients with preserved systolic function, a documented discharge recommendation for sodium-restricted diet may be associated with lower 30-day death and hospital readmission rate. Prospective studies are needed to account for specific formats of discharge education and aspects of outpatient management, including comprehension of and adherence to sodium-restricted diet. The modifiable risk factor of dietary sodium intake represents a potential target to improve outcomes in this challenging population.

CLINICAL SIGNIFICANCE.

Heart failure with preserved systolic function currently has no evidence-based treatment strategy.

Guideline-based hospital performance measures include providing appropriate discharge instructions for all heart failure patients.

Heart failure patients with preserved systolic function are less likely than systolic heart failure patients to receive appropriate hospital discharge recommendations.

Heart failure patients with preserved systolic function who receive a documented discharge recommendation for sodium-restricted diet might have a lower short-term risk of death and hospital readmission.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Greater Flint Health Coalition, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation (all unrestricted grants). Dr. Hummel is supported by a National Institutes of Health T-32 research training grant, 5T32HL007853-10.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. DeFranco has previously served as a consultant to AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals and Pfizer, Inc. There are no other conflicts of interest to report.

Authorship: All authors had access to the data and contributed significantly to the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Yancy CW, Lopatin M, Stevenson LW, et al. ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee and Investigators. Clinical presentation, management, and in-hospital outcomes of patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure with preserved systolic function: a report from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) Database. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith GL, Masoudi FA, Vaccarino V, et al. Outcomes in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction: mortality, readmission, and functional decline. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1510–1518. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00185-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonow RO, Bennett S, Casey DE, Jr, et al. ACC/AHA clinical performance measures for adults with chronic heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on performance measures (writing committee to develop heart failure clinical performance measures) endorsed by the Heart Failure Society of America. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1144–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vinson JM, Rich MW, Sperry JC, et al. Early readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1990;38:1290–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1990.tb03450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michalsen A, Konig G, Thimme W. Preventable causative factors leading to hospital admission with decompensated heart failure. Heart. 1998;80:437–441. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.5.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bayorh MA, Mann G, Walton M, Eatman D. Effects of enalapril, tempol, and eplerenone on salt-induced hypertension in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2006;28:121–132. doi: 10.1080/10641960500468276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klotz S, Hay I, Zhang G, et al. Development of heart failure in chronic hypertensive Dahl rats: focus on heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Hypertension. 2006;47:901–911. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000215579.81408.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bragulat E, de la Sierra A. Salt intake, endothelial dysfunction, and salt-sensitive hypertension. J Clin Hypertens. 2002;4:41–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-6175.2002.00503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishimitsu T, Minami J, Nishikimi T, et al. Responses of natriuretic peptides to acute and chronic salt loading in normotensive and hypertensive subjects. Hypertens Res. 1998;21:15–22. doi: 10.1291/hypres.21.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown WJ, Jr, Brown FK, Krishan I. Exchangeable sodium and blood volume in normotensive and hypertensive humans on high and low sodium intake. Circulation. 1971;43:508–519. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.43.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujiwara N, Osanai T, Kamada T, et al. Study on the relationship between plasma nitrite and nitrate level and salt sensitivity in human hypertension: modulation of nitric oxide synthesis by salt intake. Circulation. 2000;101:856–861. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.8.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams JS, Williams GH, Jeunemaitre X, et al. Influence of dietary sodium on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and prevalence of left ventricular hypertrophy by EKG criteria. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:133–138. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Musiari L, Ceriati R, Taliani U, et al. Early abnormalities in left ventricular diastolic function of sodium-sensitive hypertensive patients. J Hum Hypertens. 1999;13:711–716. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Avolio AP, Clyde KM, Beard TC, et al. Improved arterial distensibility in normotensive subjects on a low salt diet. Arteriosclerosis. 1986;6:166–169. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.6.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guideline update for the diagnosis and management of chronic heart failure in the adult—summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1116–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:933–989. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, et al. Association between performance measures and clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA. 2007;297:61–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eagle KA, Montoye CK, Riba AL, et al. Guideline-based standardized care is associated with substantially lower mortality in Medicare patients with acute myocardial infarction: the American College of Cardiology’s Guidelines Applied in Practice (GAP) projects in Michigan. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1242–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paulus WJ, Tschope C, Sanderson JE, et al. How to diagnose diastolic heart failure: a consensus statement on the diagnosis of heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction by the Heart Failure and Echocardiography Associations of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2539–2550. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee DS, Austin PC, Rouleau JL, et al. Predicting mortality among patients hospitalized for heart failure: derivation and validation of a clinical model. JAMA. 2003;290:2581–2587. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee DS, Austin PC, Stukel TA, et al. “Dose-dependent” impact of recurrent cardiac events on mortality in patients with heart failure. Am J Med. 2009;122:162.e1–169.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krumholz HM, Chen YT, Wang Y, et al. Predictors of readmission among elderly survivors of admission with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2000;139(1 Pt 1):72–77. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(00)90311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Judge KW, Pawitan Y, Caldwell J, et al. Congestive heart failure symptoms in patients with preserved left ventricular systolic function: analysis of the CASS registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;18:377–382. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90589-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin DB. Estimating causal effects from large data sets using propensity scores. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(8 Part 2):757–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-8_part_2-199710151-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, et al. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:251–259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips CO, Wright SM, Kern DE, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning with postdischarge support for older patients with congestive heart failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;291:1358–1367. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.11.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koelling TM, Johnson ML, Cody RJ, Aaronson KD. Discharge education improves clinical outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2005;111:179–185. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151811.53450.B8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lainscak M, Cleland JGF, Lenzen MJ, et al. Recall of lifestyle advice in patients recently hospitalised with heart failure: a EuroHeart Failure Survey analysis. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:1095–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kfoury AG, French TK, Horne BD, et al. Incremental survival benefit with adherence to standardized heart failure core measures: a performance evaluation study of 2958 patients. J Card Fail. 2008;14:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.VanSuch M, Naessens JM, Stroebel RJ, et al. Effect of discharge instructions on readmission of hospitalised patients with heart failure: do all of the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations heart failure core measures reflect better care? Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:414–417. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paterna S, Gaspare P, Fasullo S, et al. Normal-sodium diet compared with low-sodium diet in compensated congestive heart failure: is sodium an old enemy or a new friend? Clin Sci (Lond) 2008;114:221–230. doi: 10.1042/CS20070193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinberger MH. Salt sensitivity of blood pressure in humans. Hypertension. 1996;27(3 Pt 2):481–490. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.27.3.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Borlaug BA, Kass DA. Ventricular-vascular interaction in heart failure. Heart Fail Clin. 2008;4:23–36. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2007.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cotter G, Felker GM, Adams KF, et al. The pathophysiology of acute heart failure—is it all about fluid accumulation? Am Heart J. 2008;155:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]