Abstract

To advance the identification of quantitative trait loci (QTLs) to reduce Cd content in rice (Oryza sativa L.) grains and breed low-Cd cultivars, we developed a novel population consisting of 46 chromosome segment substitution lines (CSSLs) in which donor segments of LAC23, a cultivar reported to have a low grain Cd content, were substituted into the Koshihikari genetic background. The parental cultivars and 32 CSSLs (the minimum set required for whole-genome coverage) were grown in two fields with different natural levels of soil Cd. QTL mapping by single-marker analysis using ANOVA indicated that eight chromosomal regions were associated with grain Cd content and detected a major QTL (qlGCd3) with a high F-test value in both fields (F = 9.19 and 5.60) on the long arm of chromosome 3. The LAC23 allele at qlGCd3 was associated with reduced grain Cd levels and appeared to reduce Cd transport from the shoots to the grains. Fine substitution mapping delimited qlGCd3 to a 3.5-Mbp region. Our results suggest that the low-Cd trait of LAC23 is controlled by multiple QTLs, and qlGCd3 is a promising candidate QTL to reduce the Cd level of rice grain.

Keywords: chromosome segment substitution lines (CSSLs), low cadmium (Cd), quantitative trait locus (QTL), paddy field, rice grain

Introduction

Chronic intake of cadmium (Cd) by humans causes health problems such as renal dysfunction (EFSA 2011). The average dietary intake of Cd by the Japanese population over the 10 years from 2000 to 2009 was estimated to be 3.0 μg kg−1 body weight per week, 43.1% of which came from rice and its derivatives (information available in Japanese at http://www.maff.go.jp/j/syouan/nouan/kome/k_cd/cyosa/pdf/cdtds.pdf), even though this rice (Oryza sativa L.) typically contains <0.4mg kg−1 of Cd, the international maximum limit for rice established by the Codex Alimentarius Commission of the FAO and WHO. As rice is thus a major dietary source of Cd for the Japanese people, it is important to reduce the grain Cd content in popular rice cultivars grown in unpolluted paddy fields in Japan as much as possible to reduce health risks.

A possible approach to reducing Cd intake from rice is to develop cultivars with lower grain Cd contents than those currently grown in Japan. Such cultivars can be derived efficiently through marker-assisted selection (MAS) once the genetic aspects of the low Cd trait are known. Quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping is an efficient tool to detect loci for Cd accumulation in rice and many studies of such QTLs have been performed using populations (e.g., backcross inbred lines, F2) derived from crosses between japonica and indica cultivars (Ishikawa et al. 2010, Miyadate et al. 2011, Ueno et al. 2010); however, Japanese elite cultivars (all japonica) already have lower Cd contents than indica cultivars, so cultivars with even lower grain Cd contents are needed for QTL analysis and subsequent marker-assisted breeding. Among 49 rice cultivars, LAC23, a tropical upland japonica rice bred in Africa, had a lower grain Cd content than Japanese rice cultivars; approximately 25–50% of the elite cultivar Koshihikari (Arao and Ae 2003); however, LAC23 is not a practical cultivar for use in Japan because of its late heading, long culms, long grains and low yield. Therefore, genetic analysis is necessary to enable breeders to introduce the low-Cd trait of LAC23 into Japanese cultivars.

Chromosome segment substitution lines (CSSLs)—sets of lines that carry segments covering the entire genome of a donor line within the genetic background of a recipient line—are powerful materials to facilitate the genetic analysis of agronomically and physiological useful traits and the subsequent development of near-isogenic lines (NILs) containing target genes or QTLs (Fukuoka et al. 2010). Several CSSL sets have already been used to detect QTLs controlling grain Cd content in rice (Ishikawa et al. 2005, 2010); however, these materials incorporate chromosome segments from indica cultivars into japonica. To incorporate chromosome segments from japonica LAC23 in the genetic background of japonica Koshihikari, we developed a novel CSSL population. We grew this population in two fields with naturally abundant Cd and searched for QTLs that were associated with low grain Cd content.

Materials and Methods

Development of the CSSLs

The procedure used to develop the CSSLs is summarized in Supplemental Fig. 1. Koshihikari was crossed with LAC23, and the resultant F1 plant was backcrossed to Koshihikari. Four backcrosses produced the BC4F1 generation. We performed a whole-genome survey of the BC1F1 generation and foreground selection (to select target chromosomes that were heterozygous) in the BC2F1 generation. In the BC3F1 and BC4F1 generations, foreground selection and background selection (to select non-target chromosomes and so minimize the occurrence of heterozygous and LAC23-homozygous regions) were combined. For both foreground and background selections, we selected candidate individuals by MAS using 117 simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers distributed over the whole genome (Supplemental Fig. 2; McCouch et al. 2002). Selected BC4F1 plants were self-pollinated to produce 31 BC4F2 populations. Forty-six plants were selected from among 2800 BC4F2 individuals by MAS. Although heterozygous segments remained in non-target regions, almost all target regions were homozygous. All 46 plants were self-pollinated for seed increase, giving 46 CSSLs in the BC4F3 generation. The genotypes of the 46 CSSLs were examined in detail by using 345 single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers distributed throughout the genome (Supplemental Table 1; Nagasaki et al. 2010). From the 46 CSSLs, we selected a final set of 32 lines, which was the minimum set that covered the whole genome without duplication (Fig. 1).

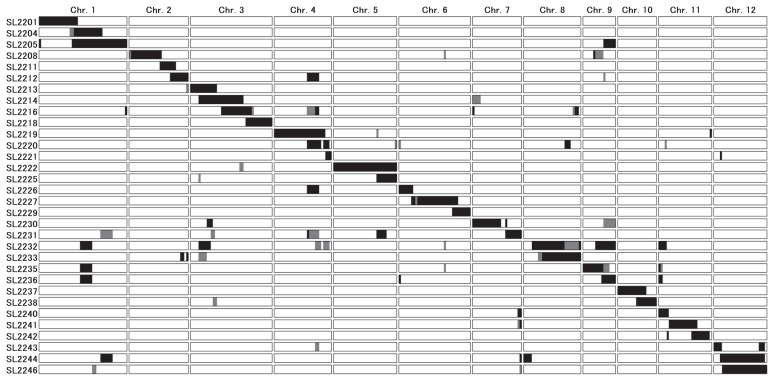

Fig. 1.

Graphical genotypes of the 32 CSSLs. Black, regions homozygous for LAC23 alleles; white, homozygous for Koshihikari alleles; gray, heterozygous. To construct the graphical genotypes, we examined the whole genome of each CSSL by using 345 single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers (Supplemental Table 1).

To delimit a region on chromosome 3 that appeared to contain a major QTL for low grain Cd content (see Results), we selected three segregating BC4F3 populations that had different points of recombination within the candidate chromosome region by using genotype data from the BC4F2 generation (Supplemental Fig. 1). In 2011, the seedlings of these populations were transplanted into field B (described below) and plants were genotyped in and around the candidate region by using 11 SSR markers and 1 cleaved amplified polymorphic sequence (CAPS) marker (Takahashi et al. 2001). Consequently, we selected the 82 plants of eight genotypes in which differential recombination had occurred in the candidate chromosome region (12 plants in line BC4F3-1, 14 in line 2, 11 in line 3, 5 in line 4, 16 in line 5, 6 in line 6, 10 in line 7 and 8 in line 8). The grain Cd contents of the 82 plants were summarized by line.

Seeds of the LAC23 × Koshihikari CSSLs developed here and more information on their genotypes can be obtained from the Rice Genome Resource Center of NIAS (http://www.rgrc.dna.affrc.go.jp/index.html).

Growth conditions

For phenotypic evaluation of Cd content in the 32 CSSLs and the parental cultivars, field trials were conducted at two sites with different natural levels of soil Cd. One site (field A) was a farmer-owned field located in the Hokuriku district of eastern Japan. The paddy soil was classified as a gray lowland soil and the soil Cd content was 0.68 mg kg−1 dry weight, as determined by 0.1M HCl extraction (the method stipulated by the Agricultural Land–Soil Pollution Prevention Law in Japan). The other site (field B) was an experimental paddy field at the National Institute of Agro-Environmental Sciences in Tsukuba City, Japan. The paddy soil was classified as a gray lowland soil and the soil Cd content was 0.21 mg kg−1 dry weight. The sites were planted and managed according to Abe et al. (2011). Five (field A) or three (field B) plants of each CSSL and 40 (field A) or 9 plants (field B) of each parent were transplanted in mid-May 2010 into each field. After irrigation was stopped at the beginning of July, the field was only rain-fed until the grain matured in mid-October. We scored days-to-heading for each parent and CSSL at mid-anthesis.

To perform fine mapping of a candidate QTL for low grain Cd on chromosome 3 (see Results), we grew eight BC4F3 lines that had recombinations within the region of interest, one CSSL (SL2218) and the parental cultivars in field B in 2011 using the same cultural practices as in 2010.

Cd analysis

After harvest, the plants were divided into unpolished grain (brown rice) and straw and each part was weighed after drying. Unless otherwise noted, “unpolished grain” is referred to as “grain” in this paper. The straw samples were ground to a fine powder in a stainless-steel rotor mill (P14; Fritsch) to pass through a 0.5-mm mesh, but the grain samples remained whole. Approximately 0.2 g of each sample was digested at 105°C for 3 h in a 65 ml polytetrafluoroethylene tube with 10 ml of 60% HNO3 solution (trace element grade) on a heating block system (DigiPREP LS; SCP Science). The straw samples were digested a second time: 1 ml of 30% hydrogen peroxide was added to each tube and the samples were digested for 60 min at 135°C in the heating block. The digested solutions were diluted with Milli-Q water and then filtered through disposable 0.2-μm PTFE syringe filters. The contents of Cd in the plant tissues were determined by inductive coupled plasma–mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS, ELAN DRC-e; Perkin-Elmer Sciex). Certified standard material was used to ensure the precision of the analytical procedure (NIES CRM No. 10 rice flour; National Institute for Environmental Studies, Tsukuba, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Significant differences in the mean values of Cd contents in grain or straw and of heading date were evaluated by several multiple comparison tests (Steel, Tukey and Steel–Dwass) using the program Ekuseru-Toukei 2006 (Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd.). QTL analysis of grain Cd content in CSSLs was performed using CSSL Finder version 0.9b1 software (http://mapdisto.free.fr/CSSLFinder/), which performs a single-marker ANOVA (P < 0.05).

Results

Genotypic characteristics of the CSSLs

Each of the 32 CSSLs contained a large substituted segment of a particular target chromosomal region from LAC23 and additional small segments in non-target regions (Fig. 1). If we assume that each recombination occurred midway between the two surrounding markers, the target LAC23 chromosomal segments in each CSSL ranged from 5.9 to 31.5 Mb and averaged 15.5 Mb. Although several non-target regions from LAC23 (5.0 Mb on average) and heterozygous regions (4.2 Mb on average) remained, each CSSL contained approximately 90% of the Koshihikari genome (93.4% on average). Together, the substituted LAC23 segments covered most of the genome, except for four regions (between NIAS_Os_ab07000724 and NIAS_Os_aa07002833 on chromosome 7, between NIAS_Os_ab08000087 and NIAS_Os_aa08000792 on chromosome 8, between NIAS_Os_aa11000174 and NIAS_Os_ab11000762 on chromosome 11 and between NIAS_Os_aa11010663 and NIAS_Os_ab11002174 on chromosome 11) and two heterozygous regions (between the telomere of the short arm and NIAS_Os_aa02000707 on chromosome 2 and between NIAS_Os_ac06000129 and NIAS_Os_ac06000385 on chromosome 6) (Fig. 1 and Supplemental Table 1).

Phenotypic variation in grain Cd content in CSSLs and parental cultivars

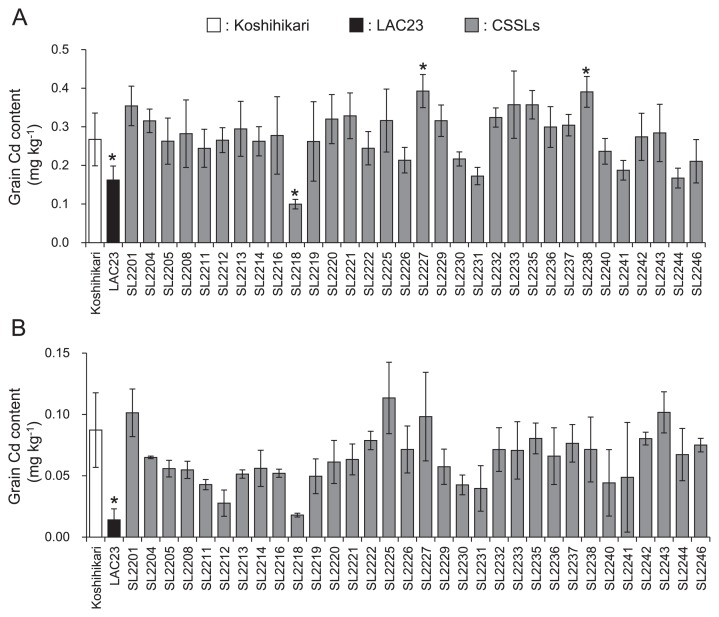

In field A, grain Cd content was significantly lower in LAC23 than in Koshihikari (0.17 vs. 0.27 mg kg−1, respectively; Fig. 2A). The grain Cd content in the 32 CSSLs ranged from 0.10 to 0.39mg kg−1 and averaged 0.28 mg kg−1. Three (SL2231, SL2241 and SL2244) of the 32 CSSLs had grain Cd contents similar to LAC23, but not significantly different from Koshihikari. SL2218 had the lowest grain Cd content, 0.10 mg kg−1, which was significantly lower than that of Koshihikari. Two CSSLs (SL2227 and SL2238) had significantly higher grain Cd contents than Koshihikari.

Fig. 2.

Grain Cd contents of CSSLs and parental cultivars (Koshihikari and LAC23). Fields A and B had different levels of naturally occurring soil Cd. Grain Cd contents were analyzed by ICP-MS. Error bars indicate standard deviation (SD). * Significantly different from Koshihikari at P < 0.05 by Steel’s multiple comparison t-test.

In field B, grain Cd content in LAC23 was much lower than in Koshihikari (0.01 and 0.09 mg kg−1, respectively; Fig. 2B) and the difference was significant. The grain Cd content in the 32 CSSLs ranged from 0.02 to 0.11 mg kg−1 and averaged 0.06 mg kg−1. Although none of the CSSLs had a statistically lower grain Cd content than Koshihikari, 28 CSSLs had lower average contents than Koshihikari and SL2218 again had the lowest Cd among the CSSLs.

Comparison of content and accumulation of Cd in grain and straw

We compared six factors (Cd content in grain, Cd content in straw, grain-to-straw ratio of Cd content, amount of Cd in grain [per plant], amount of Cd in straw [per plant] and percentage of grain Cd to total shoot Cd) between the parents and SL2218, the CSSL with the lowest grain Cd, in field A (Table 1). The average grain Cd contents decreased in the order Koshihikari > LAC23 > SL2218 and all differences were significant. The straw Cd content was the highest in LAC23, which was significantly higher than in either Koshihikari or SL2218. The grain-to-straw ratio of Cd content was significantly lower in LAC23 and SL2218 than in Koshihikari. The amount of Cd in grain on a per-plant basis was highest in Koshihikari; there was no significant difference between LAC23 and SL2218. On the other hand, SL2218 had the highest amount of Cd in straw, followed by LAC23 and Koshihikari. The percentage of grain Cd to total shoot (grain + straw) Cd was 14.9% in Koshihikari, 4.38% in LAC23 and 2.39% in SL2218.

Table 1.

Contents and total amounts of Cd in grain and straw, grain-to-straw ratio of Cd content, and percentage of grain Cd to total shoot Cd

| Cd content in grain (mg kg−1) | Cd content in straw (mg kg−1) | Ratio of Cd content (grain:straw) | Amount of Cd in grain (μg plant−1) | Amount of Cd in straw (μg plant−1) | Percentage of grain Cd to total shoot Cd (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Koshihikari | 0.27 ± 0.07 c | 1.25 ± 0.25 a | 0.22 ± 0.04 b | 6.35 ± 2.34 b | 36.4 ± 10.1 a | 14.9 |

| LAC23 | 0.17 ± 0.04 b | 1.87 ± 0.31 b | 0.09 ± 0.02 a | 2.08 ± 0.79 a | 45.4 ± 13.2 ab | 4.38 |

| SL2218 | 0.10 ± 0.01 a | 0.94 ± 0.27 a | 0.11 ± 0.02 a | 1.80 ± 0.43 a | 73.6 ± 27.8 b | 2.39 |

Koshihikari, LAC23 and SL2218 were grown in field A.

The values indicate the means ± standard deviations (Koshihikari and LAC23, n = 15; CSSLs, n = 5).

Values within a column followed by different letters are significantly different at the 5% level according to Tukey’s test (Cd content in straw) or the Steel–Dwass test (other traits).

QTL mapping for low grain Cd content

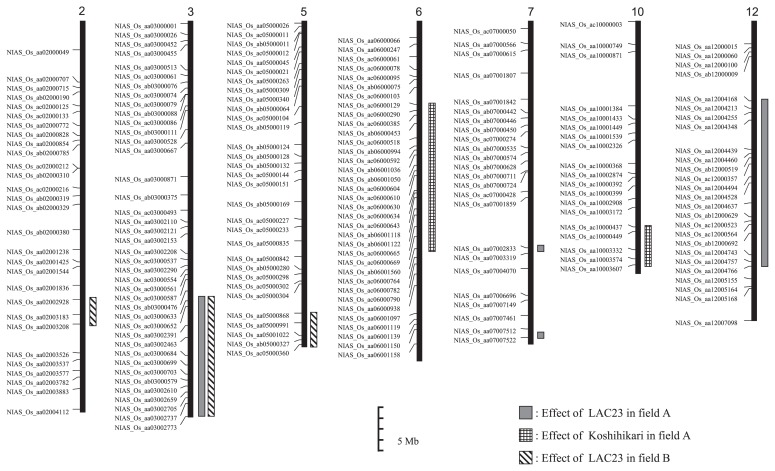

From the results of the single-marker ANOVA (Supplemental Fig. 3), the QTLs for grain Cd content are summarized in Table 2 and the chromosomal locations of QTLs are mapped in Fig. 3. In field A, we detected six QTLs on chromosomes 3, 6, 7 (two QTLs), 10 and 12; the LAC23 alleles at 4 QTLs and the Koshihikari alleles at 2 QTLs decreased the grain Cd content. In field B, we detected three QTLs on chromosomes 2, 3 and 5; the LAC23 alleles at all QTLs decreased the grain Cd content.

Table 2.

Position and effect of putative QTLs for low Cd content in rice grains

| Test field | Chr. | Marker namea | Peak marker | Maximum F-test valueb | Positive allelec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field A | 3 | NIAS_Os_ac03000633–NIAS_Os_aa03002773 | NIAS_Os_ac03000684–NIAS_Os_aa03002773 | 9.19 | LAC23 |

| 6 | NIAS_Os_ac06000129–NIAS_Os_aa06001560 | NIAS_Os_ab06001122 | 3.66 | Koshihikari | |

| 7 | NIAS_Os_aa07002833 | NIAS_Os_aa07002833 | 3.46 | LAC23 | |

| NIAS_Os_aa07007522 | NIAS_Os_aa07007522 | 10.4 | LAC23 | ||

| 10 | NIAS_Os_ac10000437–NIAS_Os_aa10003607 | NIAS_Os_ac10000437–NIAS_Os_aa10003607 | 3.29 | Koshihikari | |

| 12 | NIAS_Os_aa12004168–NIAS_Os_aa12004766 | NIAS_Os_aa12004168–NIAS_Os_aa12004766 | 4.02 | LAC23 | |

|

| |||||

| Field B | 2 | NIAS_Os_aa02002928–NIAS_Os_aa02003208 | NIAS_Os_aa02002928–NIAS_Os_aa02003208 | 4.38 | LAC23 |

| 3 | NIAS_Os_ac03000633–NIAS_Os_aa03002773 | NIAS_Os_aa03002463 | 5.60 | LAC23 | |

| 5 | NIAS_Os_aa05000868–NIAS_Os_ac05000360 | NIAS_Os_aa05000868–NIAS_Os_ab05000327 | 5.50 | LAC23 | |

Result of single-marker analysis.

After 1000 permutations, the threshold F-test values for grain Cd content were calculated as 3.28 for field A and 3.46 for field B.

Source of allele that reduces grain Cd content.

Fig. 3.

SNP linkage map showing the locations of QTLs for low grain Cd content in 32 CSSLs derived from LAC23 × Koshihikari. Chromosome numbers are indicated above; marker names are on the left. Bars represent chromosome regions exceeding a threshold F-test value for low grain Cd content according to 1000 permutations.

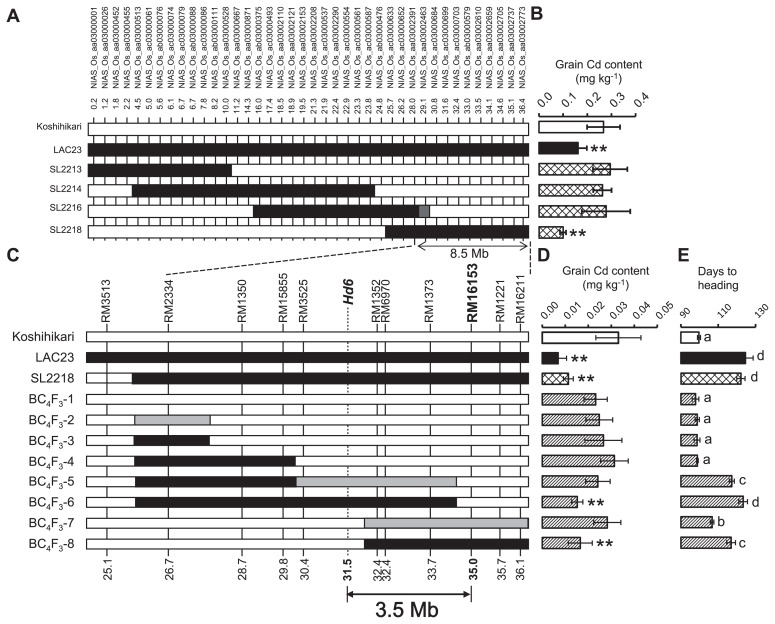

We considered the QTL on chromosome 3 to be the most effective and stable because this QTL was detected in both fields with high F-test values. Four CSSLs (SL2213, SL2214, SL2216 and SL2218) had a segment from LAC23 on chromosome 3, but the grain Cd contents of all except SL2218 were similar to that of Koshihikari (Fig. 4A, 4B). The LAC23 regions within SL2216 and SL2218 overlapped, but the grain Cd contents were different, indicating that the QTL lay outside the overlapping region. We designated the QTL in SL2218 tentatively as qlGCd3 (QTL for low grain Cd content). By using the recombination breakpoints in SL2216 and SL2218, we mapped qlGCd3 to the region defined by NIAS_Os_aa03002391 and the distal end of the long arm of chromosome 3; this region was estimated to be 8.5Mb on the basis of the IRGSP 1.0 data in RAP-DB (http://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp/).

Fig. 4.

Mapping of a putative QTL (qlGCd3) associated with low grain Cd content. (A) Graphical genotypes of parents and four CSSLs with substituted regions on chromosome 3. White, regions homozygous for the Koshihikari allele; black, homozygous for the LAC23 allele; gray, heterozygous. Names and positions of SNP markers are indicated above the genotypes. The region between the dotted lines at the bottom was identified as containing qlGCd3. (B) Grain Cd contents of parents and four CSSLs grown in field A. ** Significantly different from Koshihikari at P < 0.01 by Steel’s multiple comparison t-test. (C) Graphical genotypes of eight BC4F3 plants with recombination in the candidate region shown in A. Names and positions of SSR markers are indicated above the genotypes. Double-headed arrow indicates the limits of the chromosomal region containing qlGCd3. (D) Grain Cd contents in parents and eight BC4F3 lines grown in field B in 2011. (E) Days-to-heading in parents and BC4F3 lines. Different letters indicate significant differences at the 5% level according to Tukey’s test.

To further delimit the region containing qlGCd3, we selected eight BC4F3 lines in which recombination had occurred in the candidate region (Fig. 4C) and examined the grain Cd contents of these lines (Fig. 4D). Two of the eight lines, BC4F3-6 and -8, had significantly lower grain Cd contents than Koshihikari. Linkage analysis showed that qlGCd3 mapped within the 3.5-Mb region defined by the CAPS marker for Heading date 6 (Hd6; Takahashi et al. 2001) and RM16153 (Fig. 4C). Plants heterozygous for the qlGCd3 region (BC4F3-5 and -7) did not show significant decreases in grain Cd content relative to Koshihikari, indicating that the LAC23 allele of qlGCd3 is recessive to the Koshihikari allele. Plants that were either homozygous for the LAC23 allele (BC4F3-6 and -8) or heterozygous (BC4F3-5 and -7) headed significantly later than did Koshihikari (Fig. 4E). Although the days-to-heading of BC4F3-8 (homozygous for the LAC23 allele) was similar to the days-to-heading of BC4F3-5 (heterozygous), their grain Cd contents differed significantly.

Discussion

Because of environmental effects, the identification of reliable QTLs for grain Cd content requires testing across multiple field sites. Our QTL analysis indicates that the differences between sites greatly affected QTL detection in the CSSL mapping population derived from LAC23 and Koshihikari, because only qlGCd3 agreed between fields. It is probable that the genetic effects of other QTLs for reducing grain Cd content have poor stability and fluctuate with the influences of environment factors such as soil water potential and soil Cd availability. In contrast, qlGCd3 was stable in both fields and the LAC23 allele greatly decreased the grain Cd contents of SL2218 to the levels of LAC23 (Fig. 2). This result suggests that the LAC23 qlGCd3 allele could decrease the grain Cd content of Japanese elite cultivars.

Using recombinant inbred lines derived from a cross between Fukuhibiki and LAC23, Sato et al. (2011) identified two QTLs for low grain Cd content. qLCdG11 was detected at the distal end of the long arm of chromosome 11 and the LAC23 allele reduced grain Cd content. We did not find this QTL. Sato et al. (2011) also found qLCdG3 on chromosome 3; the Fukuhibiki allele reduced the grain Cd content. Although qlGCd3 is also on chromosome 3, the QTL position and the LAC23 allele effect were different from those reported by Sato et al. (2011). These discrepancies may be explained by the different parents (Koshihikari and Fukuhibiki) used in the two studies and by differences in cultural or environmental conditions. We previously found qGCd7 on the short arm of chromosome 7 in backcross inbred lines and CSSLs from a cross between Sasanishiki and Habataki and the Habataki allele increased the grain Cd content (Ishikawa et al. 2010). Here, we found two QTLs controlling grain Cd on chromosome 7, but on the long arm. Having the highest F-test value in field A, the QTL at the distal end of the long arm chromosome 7 might be a second candidate for reducing the grain Cd content in Japanese cultivars.

By fine substitution mapping, we delimited qlGCd3 to a 3.5-Mb region on the long arm of chromosome 3 (Fig. 4C). This region is likely to contain Hd16, a QTL for days-to-heading (Matsubara et al. 2008). Hori et al. (2012) recently reported that 37 out of 122 QTLs detected for various agronomic traits were mapped near Hd16 and that QTL clusters near Hd16 may represent the pleiotropic effects of heading-date genes. Although plants with recombination in the qlGCd3 region that did not differ in days-to-heading showed a significant difference in grain Cd content (Fig. 4C, 4D, 4E), the possible genetic effect of Hd16 on grain Cd content should be investigated.

LAC23 has unique characteristics related to Cd: it has a relatively high Cd content in the straw but a low Cd content in the grain, resulting in a lower grain-to-straw Cd ratio than in Koshihikari (Table 1). Similarly, SL2218 (carrying the LAC23 allele of qlGCd3) had a low grain-to-straw Cd ratio. These results suggest that qlGCd3 is involved in Cd transport from the shoot to the grain. Kato et al. (2010) reported a significant difference in Cd contents in phloem sap in rice cultivars grown in Cd-contaminated soil: the phloem sap Cd content of Koshihikari was approximately twice that of LAC23, suggesting less phloem Cd transport in LAC23. Uraguchi et al. (2011) identified a transporter gene, OsLCT1, involved in phloem Cd transport in rice. However, qlGCd3 and OsLCT1 must be different genes, because OsLCT1 (LOC_Os06g38120) is located on chromosome 6. Another possibility is that in plants containing the LAC23 allele at qlGCd3, the transport of Cd into phloem is limited by its sequestration in vacuoles in the shoot. Measurement of Cd levels in subcellular fractions of the shoot is needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying the differences in the grain-to-shoot Cd ratio of the parental cultivars and materials containing the LAC23 allele of qlGCd3.

Very recently, we have succeeded in producing a Koshihikari rice mutant that accumulates very low Cd in grain by using ion-beam mutagenesis (Ishikawa et al. 2012). These plants had a mutation in OsNRAMP5, a gene on chromosome 7 that encodes a Cd, Mn and Fe transporter protein. Cd uptake in the roots of mutant (osnramp5) plants was decreased owing to a defective OsNRAMP5 transporter protein. It should be easy to pyramid the osnramp5 mutant gene and the LAC23 allele of qlGCd3 into Koshihikari, because each gene is already available against the Koshihikari genetic background; in this way, it should be possible to greatly reduce Cd contents in rice grains.

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (Genome for Agricultural Innovation, NVR-0001 and QTL-4006). The authors are very grateful to Mr. Hiroshi Yamaguchi and Mr. Takahiro Ara at the National Institute for Agro-Environmental Sciences (NIAES) for their expert field assistance and to Mr. Hachidai Tanigawa, Ms. Yuko Nagaosa and Ms. Etsuko Saka, also at NIAES, for their laboratory assistance. We also thank to Dr. Kiyosumi Hori at the Agrogenomics Research Center, the National Institute of Agro Biological Sciences (NIAS) for his advice on QTL analysis.

Literature Cited

- Abe, T., Taguchi-Shiobara, F, Kojima, Y, Ebitani, T, Kuramata, M, Yamamoto, T, Yano, M and Ishikawa, S (2011) Detection of a QTL for accumulating Cd in rice that enables efficient Cd phytoextraction from soil. Breed. Sci. 61: 43–51 [Google Scholar]

- Arao, T and Ae, N (2003) Genotypic variations in cadmium levels of rice grain. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 49: 473–479 [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (2011) Scientific Opinion on tolerable weekly intake for cadmium. EFSA J. 9(2):1975 [Google Scholar]

- Fukuoka, S., Nonoue, Y and Yano, M (2010) Germplasm enhancement by developing advanced plant materials from diverse rice accessions. Breed. Sci. 60: 509–517 [Google Scholar]

- Hori, K., Kataoka, T, Miura, K, Yamaguchi, M, Saka, N, Nakahara, T, Sunohara, Y, Ebana, K and Yano, M (2012) Variation in heading date conceals quantitative trait loci for other traits of importance in breeding selection of rice. Breed. Sci. 62: 223–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, S., Ae, N, Sugiyama, M, Murakami, M and Arao, T (2005) Genotypic variation in shoot cadmium concentration in rice and soybean in soils with different levels of cadmium contamination. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 51: 101–108 [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, S., Abe, T, Kuramata, M, Yamaguchi, M, Ando, T, Yamamoto, T and Yano, M (2010) A major quantitative trait locus for increasing cadmium-specific concentration in rice grain is located on the short arm of chromosome 7. J. Exp. Bot. 61: 923–934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa, S., Ishimaru, Y., Igura, M., Kuramata, M., Abe, T., Senoura, T., Hase, Y., Arao, T., Nishizawa, N.K. and Nakanishi, H. (2012) Ion-beam irradiation, gene identification, and marker-assisted breeding in the development of low-cadmium rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: 19166–19171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato, M., Ishikawa, S, Inagaki, K, Chiba, K, Hayashi, H, Yanagisawa, S and Yoneyama, T (2010) Possible chemical forms of cadmium and varietal differences in cadmium concentrations in the phloem sap of rice plants (Oryza sativa L.). Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 56: 839–847 [Google Scholar]

- Matsubara, K., Kono, I, Hori, K, Nonoue, Y, Ono, N, Shomura, A, Mizubayashi, T, Yamamoto, S, Yamanouchi, U and Shirasawa, Ket al. (2008) Novel QTLs for photoperiodic flowering revealed by using reciprocal backcross inbred lines from crosses between japonica rice cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 117: 935–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCouch, S.R., Teytelman, L, Xu, Y, Lobos, K.B., Clare, K, Walton, M, Fu, B, Maghirang, R, Li, Z and Xing, Yet al. (2002) Development and mapping of 2240 new SSR markers for rice (Oryza sativa L.). DNA Res. 9: 199–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyadate, H., Adachi, S, Hiraizumi, A, Tezuka, K, Nakazawa, N, Kawamoto, T, Katou, K, Kodama, I, Sakurai, K and Takahashi, Het al. (2011) OsHMA3, a P-1B-type of ATPase affects root-to-shoot cadmium translocation in rice by mediating efflux into vacuoles. New Phytol. 189: 190–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasaki, H., Ebana, K, Shibaya, T, Yonemaru, J and Yano, M (2010) Core single-nucleotide polymorphisms—a tool for genetic analysis of the Japanese rice population. Breed. Sci. 60: 648–655 [Google Scholar]

- Sato, H., Shirasawa, S, Maeda, H, Nakagomi, K, Kaji, R, Ohta, H, Yamaguchi, M and Nishio, T (2011) Analysis of QTL for lowering cadmium concentration in rice grains from ‘LAC23’. Breed. Sci. 61: 196–200 [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, Y., Shomura, A., Sasaki, T. and Yano, M. (2001) Hd6, a rice quantitative trait locus involved in photoperiod sensitivity, encodes the alpha subunit of protein kinase CK2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 7922–7927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno, D., Yamaji, N., Kono, I., Huang, C.F., Ando, T., Yano, M. and Ma, J.F. (2010) Gene limiting cadmium accumulation in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107: 16500–16505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uraguchi, S., Kamiya, T., Sakamoto, T., Kasai, K., Sato, Y., Nagamura, Y., Yoshida, A., Kyozuka, J., Ishikawa, S. and Fujiwara, T. (2011) Low-affinity cation transporter (OsLCT1) regulates cadmium transport into rice grains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108: 20959–20964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.