Abstract

Human DNA mismatch repair (MMR) recognizes and binds 5-fluorouracil (5FU) incorporated into DNA and triggers a MMR-dependent cell death. Absence of MMR in a patient's colorectal tumor abrogates 5FU's beneficial effects on survival. Changes in the tumor microenvironment like low extracellular pH (pHe) may diminish DNA repair, increasing genomic instability. Here, we explored if low pHe modifies MMR recognition of 5FU, as 5FU can exist in ionized and non-ionized forms depending on pH. We demonstrate that MMR-proficient cells at low pHe show downregulation of hMLH1, whereas expression of TDG and MBD4, known DNA glycosylases for base excision repair (BER) that can remove 5FU from DNA, were unchanged. We show in vitro that 5FU within DNA pairs with adenine (A) at high and low pH (in absence of MMR and BER). Surprisingly, 5FdU:G was repaired to C:G in hMLH1 -deficient cells cultured at both low and normal pHe, similar to MMR-proficient cells. Moreover, both hMSH6 and hMSH3, components of hMutSα and hMutSβ, respectively, bound 5FU within DNA(hMSH6 > hMSH3) but is influenced by hMLH1. We conclude that an acidic tumor microenvironment triggers downregulation of hMLH1, potentially removing the execution component of MMR for 5FU cytotoxicity, whereas other mechanisms remain stable to implement overall 5FU sensitivity.

Keywords: Colon cancer, 5-Fluorouracil, DNA mismatch repair, Cell death, Chemotherapy, Acidic tumor microenvironment

1. Introduction

5-Fluorouracil (5FU) is the principal chemotherapeutic agent used to treat patients with advanced colorectal cancer. 5FU-based chemotherapy improves survival in patients with stage III colon cancer and stage II and III rectal cancer [1–4]. Although 5FU-based chemotherapy is the gold standard for advanced staged colorectal cancer patients, individual patient tumor response is low, but it does have an impact on survival [5,6]. Retrospective and prospective studies of patients with colorectal cancer indicate that those patients with intact DNA mismatch repair (MMR) within their tumors have improved survival with 5FU treatment, whereas patients whose tumors lost DNA MMR do not have improved survival [7–10].

The DNA MMR system plays an important role in maintaining DNA fidelity after DNA synthesis for cell replication. DNA MMR has two recognition complexes for DNA alterations. hMutS α, a heterodimer of the DNA MMR proteins hMSH2 and hMSH6, recognizes base–base mispairs and insertion/deletion (I/D) loops less than two nucleotides [11], whereas I/D loops more than two nucleotides are recognized by hMutSβ, an hMSH2–hMSH3 heterodimer [12–19]. hMutSα not only recognizes nucleotide mispairs but can also recognize altered nucleotides that are intercalated or formed by chemotherapy, such as intercrosslinks induced by cisplatin and the adduct O6-methylguanine [20]. We and others have demonstrated that 5FU incorporated into DNA is also recognized by hMutSα [21–23]. Furthermore, we recently demonstrated that hMutSβ can recognize 5FU incorporated into DNA, and that both hMutSα and hMutSβ have additive roles for 5FU cytotoxicity [24]. 5FU is incorporated into DNA because it is available as a substrate after 5FU's action upon thymidylate synthetase (TS), causing depletion of 2′-deoxythymidine 5′-triphosphate (dTTP). Our demonstration that DNA-containing 5FU specifically triggers a DNA MMR-dependent cell death independent of its RNA actions suggests the importance of 5FU incorporated into DNA for its cytotoxicity [25].

Primary and metastatic solid tumors grow in size, outstrip normal vascular supply and nutrients, creating a unique tumor microenvironment. That tumor microenvironment is typically characterized by low extracellular pH (pHe) and hypoxia [26,27], and can be associated with increased genomic instability [28] as a result of alteration of DNA repair mechanisms [29]. Hypoxia has been demonstrated to reduce DNA MMR expression and function, but there is no data in regards to pH changes. An acidic tumor microenvironment in colorectal tumors might alter two items that can affect the chemotherapeutic response: (1) 5FU itself, as in an acidic microenvironment can be ionized and (2) DNA MMR function. Here, we examined both. We observed that in the absence of any DNA repair, 5FU preferentially pairs with adenine; irrespective of pH. Although cells with low pH reduce hMLH1 expression, 5FU:G is preferentially repaired by unaffected DNA glycosylases to C:G in the absence of DNA MMR regardless of pH. These experiments suggest that low pHe could exacerbate 5FU chemosensitivity by removing DNA MMR mechanisms that triggers cytotoxicity but simultaneously leaves unaltered glycosylase function to maintain chemosensitivity. This shifts the cytotoxicity of 5FU from DNA MMR to BER under low pHe conditions.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell lines and culture

The human colon cancer cell lines SW480 (MMR-proficient), HCT116 (hMLH1−/− and hMSH3−/−) were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, USA), and HCT116 + ch5 was kindly provided by Minoru Koi, Ph.D. (Baylor University Medical Center). HCT116 + ch3 cells were present in the laboratory. Cells were maintained in growth medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Culture medium was acidified by supplementing regular medium with 25 mM 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Acidity was adjusted to a final pH of 6.5 with 1 N NaOH as previously reported [29].

2.2. Reagents

5-FU was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (Sigma) and dissolved in DMSO (Sigma) at a stock concentration of 1 mmol/L and maintained at 4°C.

2.3. Protein extraction and Western blotting

Cultured cells were solubilized in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris– HCl [pH 7.2], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% deoxycholic acid sodium salt, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 5 mM EDTA, and proteinase inhibitor cocktail (supplied by Sigma) on ice and then centrifuged (14,000 r.p.m.) for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was mixed with 4× protein sample buffer (4× NuPAGE®LDS Sample Buffer [Life Technologies, NY, USA], 3% 2-mercaptoethanol) and heated for 10 min at 98 °C. The proteins were then separated by electrophoresis on 4–12% NuPAGE®Bis-Tris Mini Gels (Life Technologies), and transferred to Protoran™ Nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, CA, USA) in a transfer apparatus (Life Technologies). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk and 0.1% Tween in Tris-buffered saline (TBS). Immunodetection was done utilizing primary antibodies: hMSH2 (BD Biosciences, MD, USA), hMSH3 (BD Biosciences), hMSH6 (BD Biosciences), hMLH1 (BD Biosciences), TDG (Sigma), and MBD4 (Sigma), β-tubulin (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences), and horseradish peroxidase (HRP) linked F(ab')2 secondary rabbit or mouse antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA). The signals were detected by an LAS-4000 luminescent image analyzer (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) utilizing a chemiluminescent solution.

2.4. Clonogenic assay

Cells were trypsinized and washed twice with PBS. Cells were then plated on 60 mm × 15 mm Tissue Culture Dish (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA) in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium supplemented with 10% FBS adjusted to pH 7.4 or 6.5, and containing various concentrations of 5FU (0, 2.5, 5, and 7.5 μM), then incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After 14 days of growth, the culture plates were washed with PBS, fixed with methanol for 15 min, and then rewashed with PBS. The colonies were stained with 3% Giemsa (Sigma) for 15 min and rinsed with water. Viable clonal colonies of at least 50 cells were counted. The relative surviving fraction for each cell line was expressed as a ratio of the plating efficiency in treated cultures to that observed in the controls.

2.5. Construction of heteroduplex linear dsDNA

We synthesized 61-mer oligonucleotides containing 5FdU (5′-AGAACCCACTGCTTACTGGCGGGCGGGCGG-5FdU-GGCGGGCGGGGCCTTCTAGTTGCCAGCCAT-3′), mismatched thymine (5′-AGAACCCACTGCTTACTGGCGGGCGGGCGG-T-GGCGGGCGGGGCCTTCTAGTTGCCAGCCAT-3′) as a positive mismatch paired control, and an unaltered cytosine (5′-AGAACCCACTGCTTACTGGCGGGCGGGCGG-C-GGCGGGCGGGGCCTTCTAGTTGCCAGCCAT-3′) as a negative control (Sigma). 5′-Biotin-labeled 5FdU contained 61-mer oligonucleotides (5′-Biotin-AGAACCCACTGCTTACTGGCGGGCGGGCGG-5FdU-GGCGGGCGGGGCCTTCTAGTTGCCAGCCAT-3′) were synthesized (Sigma) for DNA pulldown assays. To complete the dsDNA molecule, the complementary sequence of the 61-mer was synthesized (5′-ATGGCTGGCAACTAGAAGGCCCC-C-CCCGCCGCCGCCCGCCCGCCAGTAAGCAGTGGGTTCT-3′ for in vitro analysis of binding partner of 5FU within DNA, and 5′-ATGGCTGGCAACTAGAAGGCCCC-G-CCCGCCGCCGCCCGCCCGCCAGTAAGCAGTGGGTTCT-3′ was synthesized for 5FU repair analysis in genomic DNA from colorectal cancer cells) (Sigma). Equal molar ratios of the 61-mer containing the 5FdU, mismatched thymine, unaltered strand, or 5′-biotin-labeled 5FdU contained 61-mer oligonucleotide were mixed with the complementary strand, heated to 95 °C, and allowed to cool slowly to room temperature to construct 5FdU:C containing dsDNA, 5FdU:G containing dsDNA, T:G mismatched dsDNA, C:G matched dsDNA, and biotin-labeled 5FdU:G containing dsDNA for further use.

2.6. In vitro analysis of binding partner of 5FU within DNA

The procedure for in vitro analysis of binding partners of 5FU within DNA is summarized in Fig. 2A. 5FdU:C containing dsDNA was designed to have a forward and reverse primer sequence site at both terminal ends (forward primer: 5′-AGAACCCACTGCTTACTGGC-3′ and reverse primer: 5′-ATGGCTGGCAACTAGAAGGC-3′), with other sequences designed with cytosine and guanine except that 5FdU is inserted at position 32 (Fig. 2A). One microgram of 5FdU:C containing dsDNA was used for PCR in 20μL of total mixture with 10 mM Tris–HCl adjusted to pH 7.4 or 5.7, 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.25 μM forward primer, 0.25 μM reverse primer, 5 unit of HotStarTaq® DNA polymerase (QIAGEN, CA, USA), and 200 μM dNTP, 200 μMdCTP + dGTP, 200 μM dCTP + dGTP + dATP, or 200 μM dCTP + dGTP + dTTP. After heating at 95 °C for 15 min, PCR was conducted as follows: 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 60 °C,1 min at 72°C for 20 cycles. Because the extension reaction at the primer site was not completed when the mixture contained only dCTP + dGTP, dCTP + dGTP + dATP, or dCTP + dGTP + dTTP, 100 μM dNTP was added just before the extension reaction for 10 min at 72 °C. After the extension reaction completed, the amplified product was purified using QIAquick® PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN). The purified PCR products were ligated into pGEM®-T Easy vector (Promega, WI, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The recombinant plasmids were used to transform the Escherichia coli JM109 strain (Promega). Transformants were plated onto LB agar plates containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 2 mM IPTG and 80 μg/mL X-gal. After incubation for 18 h at 37 °C, white colonies on the plates were picked up and each single colony was incubated in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium containing 100 μg/mLampicillin for 2 h. One microliter of the medium was utilized for PCR reaction mixture with 10 mM Tris–HCl [pH 8.4], 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTP, 0.25 μM forward primer (5′-AGGCGATTAAGTTGGGTAACG-3′), 0.25 μM reverse primer (5′-TGACCATGATTACGCCAAGC-3′), and 5 U of HotStarTaq DNA polymerase (QIAGEN). After heating at 95 °C for 15 min, PCR were conducted as follows: 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 60 °C, 1 min at 72 °C for 35 cycles, followed by 10 min at 72 °C. PCR products were purified and with QIAquick® PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN) and were directly sequenced using ABI 3700 analyzer (Life Technologies). The frequency of each paired base was calculated as the number of each base where 5FdU was inserted by total number of colonies with informative sequence at the 5FdU site.

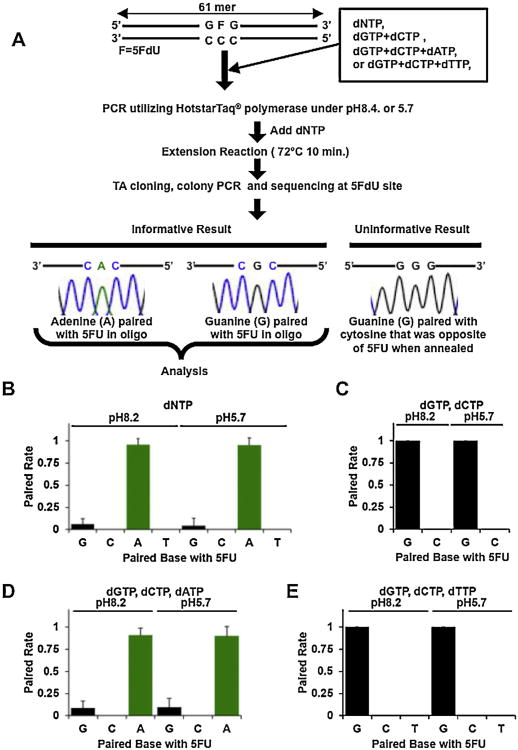

Fig. 2.

5FU incorporated into DNA is preferentially paired with adenine, followed by guanine. (A) Flowchart of procedure of in vitro analysis of binding partner of 5FU within DNA. (B-E) Frequencies of paired base with 5FU incorporated into DNA. One microgram of 5FdU:C containing dsDNA template PCR were utilized for both pH 8.2 or pH5.7 as a model of intracellular pH (pHi) of tumor cells or normal cells in acidic tumor microenvironment with dNTP (B), only dCTP and dGTP (C), only dCTP, dGTP, and dATP (D), or only dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP (E). After TA cloning and total colony PCR, paired bases were analyzed by direct sequencing. The frequency of paired bases was calculated as the number of each base where 5FdU was inserted by total number of colonies (N ≥ 24) with an informative sequence at the 5FdU site. 5FU within DNA is predominantly paired with adenine when both dGTP and dATP are available (B, D), whereas guanine is preferentially paired with 5FU when dATP is absent (C, E).

2.7. 5FU repair analysis within genomic DNA from colorectal cancer cells

The procedure of 5FU repair analysis in genomic DNA from colorectal can cer cells is summarized in Fig. 3A. Cells were co-transfected with 5 μg of 5FdU:G containing dsDNA, T:G mismatched dsDNA, or C:G matched dsDNA, and 1 μg of puromycin selection plasmid by using Nucleofector Kit V (for SW480 and HCT116) (Amaxa, Cologne, Germany), following the manufacturer's instructions. Selection with 0.75 mg/mL puromycin-containing culture medium adjusted to pH 7.4 or pH 6.5 commenced 12 h after transfection. Ten days after transfection, genomic DNA was isolated using a Wizerd® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega). Purified genomic DNA was used for a PCR reaction mixture with 10 mM Tris–HCl [pH 8.4], 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTP, 5U of HotStarTaq DNA polymerase (QIAGEN), 0.25 μM forward primer (5′-AGAACCCACTGCTTACTGGC-3′) and reverse primer (5′-ATGGCTGGCAACTAGAAGGC-3/) whose sequence is identical with each end of 5FdU:G, T:G, or C:G matched dsDNA. After heating at 95 °C for 15 min, PCR was conducted as follows: 30 s at 94 °C, 30 sat 60 °C, 1 min at 72° C for 25 cycles, followed by 10 min at 72 °C. PCR products were purified and with QIAquick® PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN). The purified PCR products were ligated into pGEM®-T Easy vector (Promega) following manufacturer's instructions. The recombinant plasmids were used to transform the E. coli JM109 strain (Promega). Transformants were plated onto LB agar plates containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 2 mM IPTG and 80 μg/mL X-gal. After incubation for 18 h at 37 °C, white colonies on the plates were picked up and each single colony were incubated in LB medium containing 100 μ/mL ampicillin for 2h. One microliter of the medium was used for the PCR reaction mixture with 10 mM Tris–HCl [pH 8.4], 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM dNTP, 0.25 μM forward primer (5′-AGGCGATTAAGTTGGGTAACG-3′), 0.25 (xM reverse primer (5′-TGACCATGATTACGCCAAGC-3′), and 5U of HotStarTaq® DNA polymerase (QIAGEN). After heating at 95 °C for 15 min, PCR were conducted as follows: 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 60°C, 1 min at 72°C for 35 cycles, followed by 10min at 72°C. PCR products were purified and with QIAquick® PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN) and were directly sequenced using ABI3700 analyzer (Life Technologies). The frequency of repaired 5FdU site was calculated as the number of repaired (5FdU:G to C:G) or unrepaired (5FdU:G to T:A) site by total sequence at the 5FdU site.

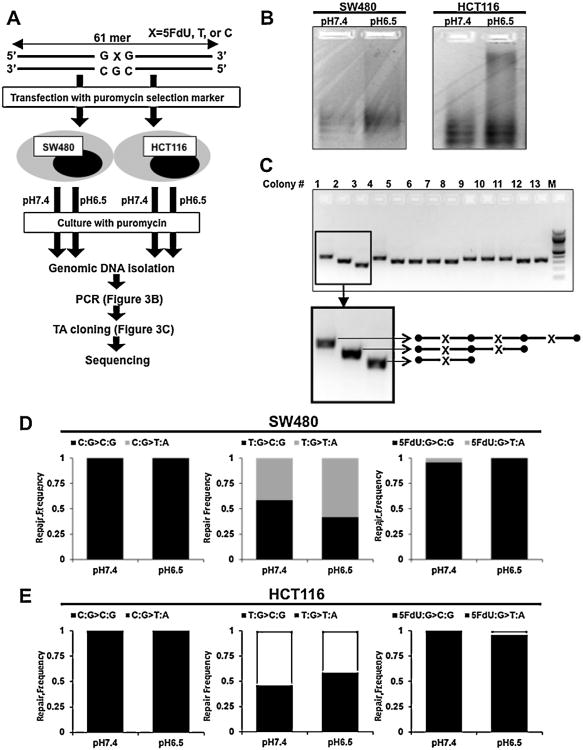

Fig. 3.

5FU incorporated into DNA is repaired in hMLH1 -downregulated cells in an acidic tumor microenvironment. (A) Flowchart of procedure of 5FU repair analysis in genomic DNA from colorectal cancer cells. SW480 and HCT116 were co-transfected with 5FdU:G-containing dsDNA, T:G mismatched dsDNA, or C:G matched dsDNA, and puromycin selection plasmid. Selection with 0.75 mg/mL puromycin-containing culture medium adjusted to pHe 7.4 or pHe 6.5 commenced 12haftertransfection. Ten days after transfection, genomic DNA was isolated. (B) Isolated genomic DNA was used for PCR, showed polyclonal PCR products in both MMR-proficient and hMLH1 -deficient cells cultured at both low and normal pHe. (C) Concatamer formation after genomic DNA integration. After TA cloning of the purified PCR products followed by colony PCR, we confirmed by direct sequencing that the integrated dsDNA into genomic DNA formed concatamers (see Fig. S1). (D) Repair frequency of 5FU within DNA in MMR-proficient cells. The integrated C:G site of dsDNA was unchanged under both low and normal pHe (left panel). Integrated T:G heteroduplex sites in MMR-proficient cells repaired to either T:A or C:G at both normal and low pHe (middle panel). When cells were transfected with 5FdU:G containing dsDNA, 5FdU:G sites were mainly repaired to C:G in MMR-proficient cells at both normal and low pHe (right panel). Repair frequency between normal and low pHe did not show any significance by Chi-square test. (E) Repair frequency of 5FU within DNA in hMLH1-deficient cells. The integrated C:G site of dsDNA was unchanged under both low and normal pHe (left panel). New equivalent T:G to C:G orT:G toT:G changes were seen in these hMLH1 -deficient cells (middle panel). Interestingly 5FdU:G was also predominantly repaired to C:G in hMLH1 -deficient cells as like MMR-proficient cells at both normal and low pHe (right panel). Repair frequency between normal and low pHe did not show any significance by Chi-square test.

2.8. DNA pulldown assay

We utilized 106 cells that were washed with cold PBS, and proteins were extracted from nuclei by using a Nuclear Extraction Kit (Cayman Chemical, MI, USA) following the manufacturer's instructions. For immobilization, biotin-labeled dsDNA probes (12.5 pmol) was mixed with 20 μg Dynabeads® M-280 Streptavidin (Invitrogen) in washing buffer (5 mM Tris–HCl [pH 7.5], 0.5 mM EDTA, and 1 MNaCl) and incubated for40minat room temperature utilizing a rotator. After the washing procedure using Magnetic Rack (Magna GrIP™ Rack supplied by Millipore, CA, USA), immobilized biotin-labeled dsDNA probes with or without unlabeled DNA probe (competitor) were added in incubation buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl [pH 7.2], 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 0.01% NP-40, and 1 mM DTT) followed by mixture with 25 μg of nuclear lysate, and incubated using a rotator for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, precipitated proteins were mixed with 30 μL 1 × protein sample buffer and boiled for 3 min, and the supernatant was collected for Western blotting.

3. Results

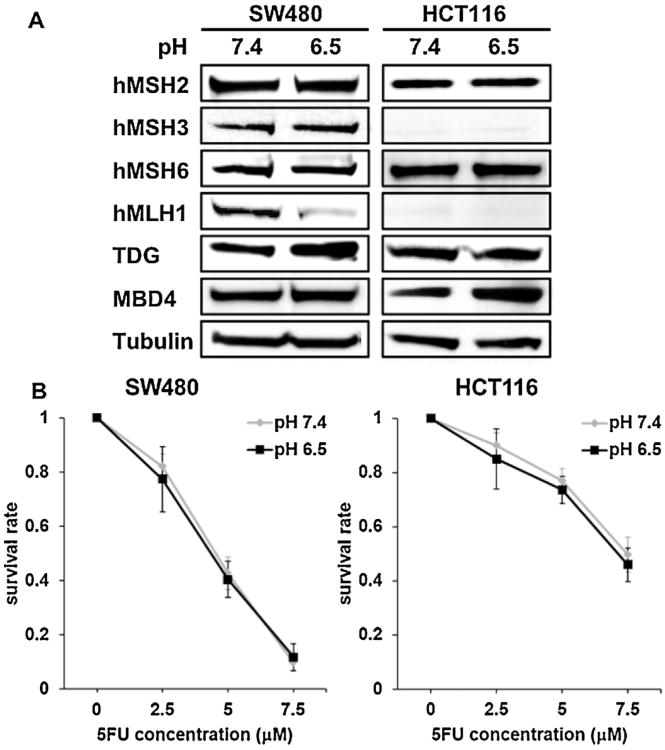

3.1. An acidic microenvironment causes hMLH1 downregulation but does not change 5FU resistance

We first analyzed expression of the DNA MMR proteins in DNA MMR-proficient colon cancer cells cultured under normal or low pHe. Of the DNA MMR proteins, only hMLH1, a component of a heterodimer hMutLα, was downregulated when cultured at low pHe compared to cells cultured at normal pHe (Fig. 1A). Expression of hMSH6, a component of a heterodimer hMutSα, hMSH3, a component of hMutSβ, and hMSH2, a common component to both hMutSα and hMutSβ, showed no change in expression at low and normal pHe. In hMLH1 -deficient HCT116 cells, the expression of the existing native MMR proteins was also unchanged between low and normal pHe. However, expression of TDG and MBD4, known DNA glycosylases for base excision repair (BER) that can affect 5FU cytotoxicity [30,31], were not altered between low and normal pHe (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Acidic tumor microenvironment downregulates hMLH1 alone but does not diminish 5FU chemosensitivity. (A) SW480 and HCT116 were cultured at both low extracellular pH (pHe) (pHe 6.2) and normal pHe (pHe 7.4) for 72 h. After extraction of protein, Western blotting was utilized to compare expression of hMSH2, hMSH3, hMSH6, hMLH1, TDG, MBD4 between both low and normal pHe. Representative blots from three independent experiments are shown. (B) Clonogenic assay of SW480 and HCT116 cells in response to 5FU. Cells were plated in media at both at low pHe (pH 6.5) and normal pHe (pH 7.4) containing 0, 2.5, 5, 7.5 μM 5FU and allowed to form colonies for 14 days. The plates were then fixed with methanol and stained with 3% Giemsa, and viable colonies were counted.

Cell colony survival assays were then performed to determine the effect of hMLH1 downregulation induced by low pHe for overall 5FU cytotoxicity. In DNA MMR-proficient cells, we noted no difference in cell survival at low pHeversus normal pHe following 5FU treatment (0–7.5 μM). Further, in hMLH1 -deficient cells, cell survival after 5FU treatment was also similar between low and normal pHe (Fig. 1B). Thus, sensitivity to 5FU was not influenced simply by hMLH1 downregulation that was induced by the acidic microenvironment.

3.2. 5FU incorporated into DNA is preferentially paired with adenine, followed by guanine

The intracellular pH (pHi) of cancer cells in an acidic tumor microenvironment have a pHi of >7.4 (called ‘reversed’ pH gradient), whereas pHe is lower than observed for normal differentiated adult cells [32-36]. Thus, here, our approach was to analyze which base is preferentially paired with 5FU incorporated into DNA under both low (pH 5.7) and high (pH 8.2) pH conditions. Utilizing 5FdU:C containing dsDNA as a template, we performed PCR with Taq DNA polymerase which does not have 3′–5′ exonuclease activity (proof reading activity), at low and high pH conditions. We performed TA cloning of the PCR products, transformed JM109 E. coli cells with the PCR product to allow colony formation, and performed direct sequencing using the colony PCR products. Direct sequencing of each PCR product can include sequences that either reflect the paired base with 5FdU within DNA (informative sequences), or 5FdU paired cytosine inserted sequences, which reflects the paired base with opposite cytosine and are not informative (Fig. 2A).

When the 5FdU:C containing dsDNA template was amplified using all four dNTPs, 5FdU within DNA was predominantly paired with adenine at both low and high pH (frequency; 0.95 ±0.08 at low pH and 0.96 ±0.07 at high pH), followed rarely by guanine (frequency; 0.04 ±0.08 at low pH and 0.06 ±0.06 at high pH) (Fig. 2B). No cytosine or thymidine pairings with 5FU were observed for both pH conditions. To determine the direct frequency of 5FdU paired bases, we further amplified the 5FdU:C containing dsDNA template using only dCTP + dGTP, dCTP + dGTP + dATP, or dCTP + dGTP + dTTP, followed by addition of dNTP for the final extension reaction (Fig. 2A). When we added only dCTP and dGTP, or dCTP, dGTP, and dTTP, 5FdU was paired with guanine at both low and high pH (Fig. 2C and E). In contrast, when we added only dCTP + dGTP + dATP, adenine was predominantly paired with 5FdU within DNA at both low and high pH (frequency; 0.90 ± 0.10 at low pH and 0.91 ±0.10 at high pH), followed by guanine (frequency; 0.10 ± 0.09 at low pH and 0.07 ± 0.07 at high pH) as was seen when we added all 4 dNTPs (Fig. 2D). These findings indicate that 5FU incorporated into DNA pairs with adenine preferably at both low and high pH condition (in the absence of any repair mechanisms) and pairs with guanine when adenine is absent.

3.3. 5FU incorporated into DNA is repaired despite absence of hMLH1 in an acidic tumor microenvironment

We then explored 5FdU:C pairing within cells in which active repair mechanisms are present to assess the influence of the tumor microenvironment (Fig. 3A). We constructed and transfected C:G, T:G, and 5FdU:G containing dsDNA into cells, adjusted the culture medium to pH 7.4 or pH 6.5, isolated genomic DNA and amplified across the C:G, T:G, 5FdU:G containing dsDNA sequences to determine 5FdU pairings (Fig. 3B). We confirmed that the transfected 5FdU:G containing dsDNA was integrated into genomic DNA forming concatamers as previously demonstrated [37,38] (Fig. 3C, Fig. S1).

Supplementary material related to this article found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2013.04.006.

In MMR-proficient cells, the integrated C:G site in dsDNA was unchanged at both low and normal pHe (C:G to C:G, frequency; 1.0 at normal pHe and 1.0 at low pHe as shown in the left panel of Fig. 3D), as was in hMLH1 -deficient cells (C:G to C:G, frequency; 1.0 at normal pHe and 1.0 at low pHe as shown in the left panel of Fig. 3E). Integrated T:G heteroduplex sites in MMR-proficient cells at normal pHe were repaired to either T:A or C:G (frequency; 0.58 of T:G to C:G, and 0.42 of T:G to T:A as shown in the middle panel of Fig. 3D) because T:G heteroduplex sites were presumably equally repaired by the DNA MMR system. At low pHe, at which hMLH1 is downregulated, integrated T:G heteroduplex sites were changed to either T:A or C:G (frequency; 0.42 of T:G to C:G, 0.59 of T:G to T:A as shown in the middle panel of Fig. 3D) because of both T or G is used as a parent strand for further DNA replication. The results of equal chance repair for a T:G to C:G or T:G to T:A change at low pH condition were confirmed in hMLH1 -deficient cells (frequency; 0.46 of T:G to C:G at normal pHe, and 0.54 of T:G to T:A at normal pHe, 0.58 of T:G to C:G at low pHe, and 0.42 of T:G to T:A at low pHe as shown in the middle panel of Fig. 3E). Surprisingly, when transfected with 5FdU:G containing dsDNA, 5FdU:G sites were mainly repaired to C:G in MMR-proficient cells at both normal and low pH (Fig. 3D) which is nearly identical to the pairings observed for hMLH1 -deficient cells (right panel of Fig. 3E). These results suggest that 5FU incorporated into DNA is repaired likely by BER despite hMLH1 downregulation in an acidic tumor microenvironment.

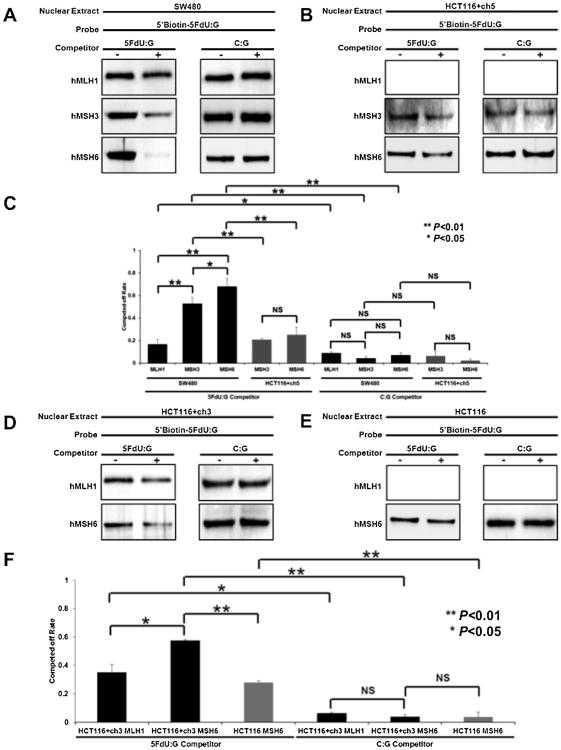

3.4. Affinity of hMutSα is greater for 5FdU within DNA as compared to hMutSβ or hMutLα

We previously demonstrated that 5FU cytotoxicity is dependent on functional DNA MMR binding of hMutS complexes, with hMutSα > hMutSβ [24]. Here, we utilized a pull-down assay to assess the relative binding of 5FU to hMutSα, hMutSβ, and hMutLα to determine if there is any direct influence of hMutLα upon 5FU within DNA. By Western blotting of proteins interacting with the probes, hMLH1, hMSH3, and hMSH6 could be detected (Fig. 4A). To analyze the affinity level of each protein to 5FU, unlabeled 5FdU:G containing dsDNA probes (5FdU:G competitor) were mixed with biotin-labeled 5FdU:G containing dsDNA probes to compare competing-off rates reflecting the affinity level. We were surprised to find that the level of hMLH1 was reduced with 5FU competition, which could reflect combined hMutLα complex associated with hMutSα or hMutSβ. Overall, the affinity level of 5GdU:G competitor for hMLH1 was lower than that of hMSH3 and hMSH6 (P <0.01), whereas the affinity level for unlabeled C:G containing dsDNA probes (C:G competitor) was essentially non-existent (Fig. 4A and C). These results indicate that hMutSα and hMutSβ bind to 5FU in DNA with relatively high affinity (hMutSα > hMutSβ), and that hMutLα can be competed off either as a result of direct binding, or more likely indirect binding through one of the hMutS complexes. Since the hMutLα complex is thought to execute signaling to other proteins for repair or cell death, it is theorized that in the absence of hMLH1 (such as seen with low pHe), the execution function of MMR for 5FU cytotoxicity is lost, while the binding function by hMutSα or hMutSβ is preserved.

Fig. 4.

Affinity of hMLH1 for 5FU within DNA is lower than that of hMSH3 or hMSH6. (A, B, D, E) Immobilized biotin-labeled dsDNA probes with or without unlabeled DNA probe (competitor) were added in incubation buffer followed by mixture with 25 μg of nuclear lysate isolated from SW480 (MMR-proficient) (A), HCT116 + ch5 (hMLH1−/− but hMSH3 restored) (B), HCT116 + ch3 (hMSH3−/− but hMLH1 restored) (D) and HCT116 (hMLH1−/− and hMSH3−/−)(E), and incubated using a rotator for 1 hat room temperature. After washing, precipitated proteins were mixed with protein sample buffer and boiled for 3 min, and the supernatant was collected for Western blowing. (C, F) Unlabeled 5FdU:G containing dsDNA probes (5FdU:G competitor) were mixed with biotin-labeled 5FdU:G containing dsDNA probes and the competing off rate was compared which reflects the affinity level. In MMR-proficient cells, we found that the affinity level of 5GdU:G competitor for hMLH1 was markedly lower than that of hMSH3 and hMSH6 with hMSH6>hMSH3 ≫ ≫ hMLH1 (P < 0.01). Furthermore, the competing off rates for hMSH6 and hMSH3 were reduced when hMLH1 was absent. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

3.5. Absence of hMLH1 alters binding of hMSH6 and hMSH3 to 5FdU

When hMLH1 is expressed, pull down by the 5FdU:G competitor causes a modest reduction in hMLH1 protein that is not observed by pull down with the C:G competitor. We observed this in MMR-proficient as well as hMLH1 -restored cells (Fig. 4A, C, D, and F). We then explored MMR binding in the absence of hMLH1. As show in Fig. 4B, C, E, and F, the competing off rates for hMSH6 and hMSH3 were reduced when hMLH1 is not present. Thus, with this experiment, loss of hMutLα function may secondarily alter the binding capability of hMutSα and hMutSβ, further reducing MMR execution of cytotoxicity to 5FU incorporated into DNA.

4. Discussion

Clinical evidence suggests that patients with advanced colorectal cancer and whose tumors retain DNA MMR function derive a survival benefit with 5FU-based chemotherapy, compared with patients with tumors that lost MMR function. In experimental studies, hMutSα and hMutSβ participate in recognition of 5FU incorporated within DNA [23,24], which parallels MMR-directed 5FU cytotoxicity, with hMutSα > hMutSβ [25]. Although it has been demonstrated that some components of the tumor microenvironment such as hypoxia diminish DNA MMR repair activity [39–42], there is no data regarding DNA MMR binding or function for 5FU induced cytotoxicity in the typically acidic tumor microenvironment. Our study demonstrates (a) that hMLH1 is downregulated in an acidic microenvironment but its absence does not modify 5FU cytotoxicity, (b) 5FU incorporated into DNA is paired with adenine in an acidic microenvironment in the absence of any cellular repair mechanisms, (c) 5FU incorporated into DNA is repaired in cancer cells regardless of the hMLH1 status, (d) hMutSα and hMutSβ principally bind 5FU within DNA but hMutLα could potentially have a direct binding role to 5FU, and (e) absence of hMutLα has a secondary influence hMutSα and hMutSβ binding to 5FdU. Overall the data suggests that in the absence of hMLH1, as triggered by an acidic microenvironment, the MMR execution function of DNA MMR is abrogated while binding and recognition may be partially preserved but reduced. With DNA glycosylases unchanged in the acidic microenvironment, 5FU sensitivity is likely maintained within solid colorectal tumors despite loss of DNA MMR function. Our observations indicate a shift of cytotoxicity from DNA MMR to BER under low pHe conditions. The redundant mechanisms for 5FU recognition allow cells to attempt repair of 5FU within DNA to ensure its fidelity.

Tumor cells often use glycolysis where glucose is converted into lactate to produce ATP, rather than oxidative metabolism, because hypoxic regions are likely to have a decreased supply of nutrients such as glucose and essential amino acids [27,43,44] causing a low interstitial pH [45,46]. A decreased pHe may be associated with genomic instability but the acidic effects upon DNA MMR have not been previously evaluated [40,41]. Here, we observed that an acidic microenvironment induced downregulation of hMLH1. It has been previously shown that hMLH1 is downregulated with hypoxia [41], indicating combined effects to reduce hMLH1 expression and function that could contribute to acquired genetic instability and tumor progression. This combination has not been tested or confirmed experimentally.

It is now apparent that there are two major pathways for the cellular response to 5FU, an RNA-directed cytotoxicity via incorporation of 5-fluorouridine-5′-triphosphate (FUTP) into RNAs, and a DNA-directed cytotoxicity via inhibition of thymidylate synthetase (TS) or incorporation of 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-triphosphate (5FdUTP) into DNA. TS inhibition by 5FU prevents the conversion of dUMP to dTMP and results in decreased intracellular dTTP pools [47]. The dNTP pool imbalance leads to misincorporation of dUTP or/and 5FdUTP into DNA [22,48]. Meyers et al. demonstrated that 5FdUTP misincorporation forms 5FdU:G mismatched nucleotides, even in hMLH1 -deficient cells [22]. As they could detect 5FdU:G mismatched nucleotides 3-10 days after 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (5FdUrd) treatment, it is possible that misincorporated 5FdU occurs on both parental and daughter strands. However, no one has previously demonstrated which base pairs with 5FU that is already incorporated into DNA, as we did not treat cells but utilized 5FdU containing constructs.

It is notable that in an acidic tumor environment, the intracellular pH (pHi) of cancer cells increase above the physiological pHi >7.4 simultaneous with a more acidic pHe, and this can even be seen in normal differentiated adult cells [32–36]. We examined how 5FU incorporated into DNA forms nucleotide pairing at both high (simulating tumor cellular pHi) and an acidic microenvironment (simulating a low pHe model). It has been proposed that 5FU dynamically pairs with guanine at low pH because 5FU becomes ionized, whereas 5FU dynamically pairs with adenine at physiological pH conditions [49]. These pairings are detected with 5FU treatment of cells, unlike a fixed template of dsDNA. Our data indicate that in an acidic microenvironment in the absence of any DNA repair mechanisms, 5FU within DNA pairs with adenine. This would suggest in an acidic microenvironment 5FdU:G would cause C:G to T:A mutations due to the pairing of adenine with 5FdU. However, we were surprised with our observation that 5FdU integrated into genomic DNA as a 5FdU:G mispair was repaired to C:G at both normal pHe and low pHe, as well as in hMLH1 -downregulated cells. This is likely because DNA glycosylases for base excision repair (BER) that remove 5FU from DNA (i.e. TDG and MBD4) may also contribute 5FU repair because they are known to remove 5FU from DNA in vitro[50,51] and expression of both TDG and MBD4 did not change between normal and low pHe as shown in Fig. 1A.

There are two proposed pathways for DNA MMR-stimulated DNA-directed 5FU cytotoxicity: (i) a futile cycling or (ii) a direct damage signaling [52,53]. In cells treated with 5FU over a long period of time, the replicating polymerases will incorporate 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-triophosphate (5FdUTP) into DNA, but the repair polymerases cannot replace FdUTP residues removed by DNA MMR or BER with dTTP because of the dNTP imbalance caused by TS inhibition, triggering further rounds of futile repair and which eventually may lead to DNA strand breaks and cell death [21]. Our result of similar 5FU cytotoxicity between low and normal pHe in MMR-proficient cells as well as in hMLH1-deficient cells indicate that futile 5FU removal is likely occurring by functional MBD4 or TDG when hMLH1 is downregulated in acidic tumor microenvironment. On the other hand, direct damage signaling provides that MMR-dependent cytotoxicity might be activated through the direct interaction of the 5FU bound MMR proteins with signaling kinases such as ATR, CHK1, and CHK2, and is reported to form complexes with hMSH2, a component of both hMutSα or hMutSβ [54,55]. Prior reports indicate that murine mutant Msh2 (G674A) or Msh6 (T1217D) results in absence of MMR activity, but retains normal damage-induced apoptotic function [56,57]. Interestingly, some groups demonstrated a role of hMutS proteins that occur independently of hMLH1. Takahashi et al. showed that hMutSβ depleted cells are sensitive to cisplatin and oxaliplatin, and that this occurs independent of hMLH1 function [58]. Zhao et al. demonstrated that hMuSβ is involved in both recognition of and processing of interstrand cross-links [59], which suggests that hMutSβ is involved in both recognition and processing of certain types of ICLs in cooperation with other proteins such as nucleotide excision repair. Our data that 5FU within DNA has a higher affinity for the hMutS complexes over hMutLα indicates that the hMutS proteins may play a role for 5FU cytotoxicity independently of hMutLα, which may lead to 5FU chemosensitivity for hMSH3-deficient cells than MMR-proficient cells under acidic tumor microenvironment as shown in Fig. 1B. However, the loss of hMutLα may modify the ability of the hMutS complexes to bind 5FdU, reducing this proposed role.

In conclusion, we demonstrate hMLH1 downregulation induced by an acidic tumor microenvironment, but not a parallel reduction in 5FU resistance because of compensation by other 5FU repair mechanisms. After due consideration of our result that 5FU has a higher affinity for hMutS proteins than hMutL proteins, the role of hMutS proteins independently of hMutL might be an avenue to explore approaches toward an improved survival benefit for patients of hMLH1 -deficient colorectal cancer with 5FU-based chemotherapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by the United States Public Health Service (DK067287 and CA162147 to JMC). We are grateful to Dr. Minoru Koi, Ph.D. (Baylor University Medical Center) for providing us HCT116 + ch5 cells.

Abbreviations

- 5FU

5-fluorouracil

- pHe

extracellular pH

- pHi

intracel lular pH

- dTTP

2′-deoxythymidine 5′-triphosphate

- dATP

2′-deoxyadenosine 5′-triphosphate

- dGTP

2′-deoxyguanosine 5′-triphosphate

- dCTP

2′-deoxycytidine 5′-triphosphate

- LB

Luria-Bertani

- ICLs

interstrand crosslinks

- MMR

mismatch repair

- I/D

insertion/deletion

- FUTP

5-fluorouridine-5′-triphosphate

- TS

thymidy-late synthetase

- 5FdUTP

5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-triphosphate

- 5FdUMP

5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-monophosphate

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- 5FdU:C

5FdU mispairwith cytosine

- 5FdU:G

5FdU mispair with guanine

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributions: JMC conceived the project; MI and STR performed all experiments; MI and JMC wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Boland CR, Sinicrope FA, Brenner DE, Carethers JM. Colorectal cancer prevention and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:S115–S128. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laurie LA, Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Wieand HS, Leigh JE, Rubin J, McCormack GW, Gerstner JB, Krook JE, Malliard J, et al. Surgical adjuvant therapy of large-bowel carcinoma: an evaluation of levamisole and the combination of levamisole and fluorouracil. The North Central Cancer Treatment Group and the Mayo Clinic. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1447–1456. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.10.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, Haller DG, Laurie JA, Goodman PJ, Ungerleider JS, Emerson WA, Tormey DC, Glick JH, et al. Levamisole and fluorouracil for adjuvant therapy of resected colon carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:352–358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199002083220602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Macdonald JS, Haller DG, Laurie JA, Tangen CM, Ungerleider JS, Emerson WA, Tormey DC, Glick JH, Veeder MH, Mailliard JA. Fluorouracil plus levamisole as effective adjuvant therapy after resection of stage III colon carcinoma: a final report. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:321–326. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-5-199503010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Efficacy of intravenous continuous infusion of fluorouracil compared with bolus administration in advanced colorectal cancer. Meta-analysis Group in Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:301–308. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carethers JM, Chung H, Tajima A. Mismatch repair competency predicts 5-fluorouracil effectiveness on patient survival. Falk Symp. 2007;158:72–84. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carethers JM, Smith EJ, Behling CA, Nguyen L, Tajima A, Doctolero RT, Cabrera BL, Goel A, Arnold CA, Miyai K, Boland CR. Use of 5-fluorouracil and survival in patients with microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:394–401. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jover R, Zapater P, Castells A, Llor X, Andreu M, Cubiella J, Balaguer F, Sempere L, Xicola RM, Bujanda L, Rene JM, Clofent J, Bessa X, Morillas JD, Nicolas-Perez D, Pons E, Paya A, Alenda C. The efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil in colorectal cancer depends on the mismatch repair status. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ribic CM, Sargent DJ, Moore MJ, Thibodeau SN, French AJ, Goldberg RM, Hamilton SR, Laurent-Puig P, Gryfe R, Shepherd LE, Tu D, Redston M, Gallinger S. Tumor microsatellite-instability status as a predictor of benefit from fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:247–257. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sargent DJ, Marsoni S, Monges G, Thibodeau SN, Labianca R, Hamilton SR, French AJ, Kabat B, Foster NR, Torri V, Ribic C, Grothey A, Moore M, Zaniboni A, Seitz JF, Sinicrope F, Gallinger S. Defective mismatch repair as a predictive marker for lack of efficacy of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3219–3226. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marsischky GT, Kolodner RD. Biochemical characterization of the interaction between the Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH2-MSH6 complex and mispaired bases in DNA. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26668–26682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acharya S, Wilson T, Gradia S, Kane MF, Guerrette S, Marsischky GT, Kolodner R, Fishel R. hMSH2 forms specific mispair-binding complexes with hMSH3 and hMSH6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13629–13634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blackwell LJ, Bjornson KP, Modrich P. DNA-dependent activation of the hMutSalpha ATPase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32049–32054. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Wind N, Dekker M, Claij N, Jansen L, van Klink Y, Radman M, Riggins G, van der Valk M, van't Wout K, te Riele H. HNPCC-like cancer predisposition in mice through simultaneous loss of Msh3 and Msh6 mismatch-repair protein functions. Nat Genet. 1999;23:359–362. doi: 10.1038/15544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Genschel J, Littman SJ, Drummond JT, Modrich P. Isolation of MutSbeta from human cells and comparison of the mismatch repair specificities of MutSbeta and MutSalpha. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19895–19901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Habraken Y, Sung P, Prakash L, Prakash S. Binding of insertion/deletion DNA mismatches by the heterodimer of yeast mismatch repair proteins MSH2 and MSH3. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1185–1187. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70686-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson RE, Kovvali GK, Prakash L, Prakash S. Requirement of the yeast MSH3 and MSH6 genes for MSH2-dependent genomic stability. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7285–7288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuraguchi M, Yang K, Wong E, Avdievich E, Fan K, Kolodner RD, Lipkin M, Brown AM, Kucherlapati R, Edelmann W. The distinct spectra of tumor-associated Apc mutations in mismatch repair-deficient Apc1638N mice define the roles of MSH3 and MSH6 in DNA repairand intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7934–7942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Umar A, Risinger JI, Glaab WE, Tindall KR, Barrett JC, Kunkel TA. Functional overlap in mismatch repair by human MSH3 and MSH6. Genetics. 1998;148:1637–1646. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.4.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duckett DR, Drummond JT, Murchie AI, Reardon JT, Sancar A, Lilley DM, Modrich P. Human MutSalpha recognizes damaged DNA base pairs containing O6-methylguanine, O4-methylthymine, or the cisplatin-d(GpG) adduct. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6443–6447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fischer F, Baerenfaller K, Jiricny J. 5-Fluorouracil is efficiently removed from DNA by the base excision and mismatch repair systems. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1858–1868. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyers M, Wagner MW, Mazurek A, Schmutte C, Fishel R, Boothman DA. DNA mismatch repair-dependent response to fluoropyrimidine-generated damage. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5516–5526. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tajima A, Hess MT, Cabrera BL, Kolodner RD, Carethers JM. The mismatch repair complex hMutS alpha recognizes 5-fluorouracil-modified DNA: implications for chemosensitivity and resistance. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1678–1684. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tajima A, Iwaizumi M, Tseng-Rogenski S, Cabrera BL, Carethers JM. Both hMutSalpha and hMutSss DNA mismatch repair complexes participate in 5-fluorouracil cytotoxicity. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e28117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iwaizumi M, Tseng-Rogenski S, Carethers JM. DNA mismatch repair proficiency executing 5-fluorouracil cytotoxicity in colorectal cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2011;12:756–764. doi: 10.4161/cbt.12.8.17169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vaupel P. Tumor microenvironmental physiology and its implications for radiation oncology. Semin Radiat Oncol. 2004;14:198–206. doi: 10.1016/j.semradonc.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tredan O, Galmarini CM, Patel K, Tannock IF. Drug resistance and the solid tumor microenvironment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1441–1454. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bindra RS, Glazer PM. Genetic instability and the tumor microenvironment: towards the concept of microenvironment-induced mutagenesis. Mutat Res. 2005;569:75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seo Y, Kinsella TJ. Essential role of DNA base excision repair on survival in an acidic tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7285–7293. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kunz C, Focke F, Saito Y, Schuermann D, Lettieri T, Selfridge J, Schar P. Base excision by thymine DNA glycosylase mediates DNA-directed cytotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e91. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sansom OJ, Zabkiewicz J, Bishop SM, Guy J, Bird A, Clarke AR. MBD4 deficiency reduces the apoptotic response to DNA-damaging agents in the murine small intestine. Oncogene. 2003;22:7130–7136. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Busco G, Cardone RA, Greco MR, Bellizzi A, Colella M, Antelmi E, Mancini MT, Dell'Aquila ME, Casavola V, Paradiso A, Reshkin SJ. NHE1 promotes invadopodial ECM proteolysis through acidification of the peri-invadopodial space. FASEBJ. 2010;24:3903–3915. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-149518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gallagher FA, Kettunen MI, Day SE, Hu DE, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Zandt R, Jensen PR, Karlsson M, Golman K, Lerche MH, Brindle KM. Magnetic resonance imaging of pH in vivo using hyperpolarized 13C-labelled bicarbonate. Nature. 2008;453:940–943. doi: 10.1038/nature07017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gillies RJ, Raghunand N, Karczmar GS, Bhujwalla ZM. MRI of the tumor microenvironment. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2002;16:430–450. doi: 10.1002/jmri.10181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stuwe L, Muller M, Fabian A, Waning J, Mally S, Noel J, Schwab A, Stock C. pH dependence of melanoma cell migration: protons extruded by NHE1 dominate protons of the bulk solution. J Physiol. 2007;585:351–360. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.145185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webb BA, Chimenti M, Jacobson MP, Barber DL. Dysregulated pH: a perfect storm for cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:671–677. doi: 10.1038/nrc3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gordon JW, Scangos GA, Plotkin DJ, Barbosa JA, Ruddle FH. Genetic transformation of mouse embryos by microinjection of purified DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:7380–7384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.12.7380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perucho M, Hanahan D, Wigler M. Genetic and physical linkage of exogenous sequences in transformed cells. Cell. 1980;22:309–317. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90178-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bindra RS, Schaffer PJ, Meng A, Woo J, Maseide K, Roth ME, Lizardi P, Hedley DW, Bristow RG, Glazer PM. Down-regulation of Rad51 and decreased homologous recombination in hypoxic cancer cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8504–8518. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.19.8504-8518.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koshiji M, To KK, Hammer S, Kumamoto K, Harris AL, Modrich P, Huang LE. HIF-1alpha induces genetic instability by transcriptionally downregulating MutSalpha expression. Mol Cell. 2005;17:793–803. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mihaylova VT, Bindra RS, Yuan J, Campisi D, Narayanan L, Jensen R, Giordano F, Johnson RS, Rockwell S, Glazer PM. Decreased expression of the DNA mismatch repairgene Mlh1 under hypoxic stress in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3265–3273. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.9.3265-3273.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yuan J, Narayanan L, Rockwell S, Glazer PM. Diminished DNA repair and elevated mutagenesis in mammalian cells exposed to hypoxia and low pH. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4372–4376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dang CV, Semenza GL. Oncogenic alterations of metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:68–72. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309–314. doi: 10.1126/science.123.3191.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Helmlinger G, Yuan F, Dellian M, Jain RK. Interstitial pH and pO2 gradients in solid tumors in vivo: high-resolution measurements reveal a lack of correlation. Nat Med. 1997;3:177–182. doi: 10.1038/nm0297-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tannock IF, Rotin D. Acid pH in tumors and its potential for therapeutic exploitation. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4373–4384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Santi DV. Perspective on the design and biochemical pharmacology of inhibitors of thymidylate synthetase. J Med Chem. 1980;23:103–111. doi: 10.1021/jm00176a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carethers JM, Chauhan DP, Fink D, Nebel S, Bresalier RS, Howell SB, Boland CR. Mismatch repair proficiency and in vitro response to 5-fluorouracil. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:123–131. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70558-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sowers LC, Eritja R, Kaplan B, Goodman MF, Fazakerly GV. Equilibrium between a wobble and ionized base pair formed between fluorouracil and guanine in DNA as studied by proton and fluorine NMR. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:14794–14801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hardeland U, Bentele M, Jiricny J, Schar P. The versatile thymine DNA-glycosylase: a comparative characterization of the human, Drosophila and fission yeast orthologs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2261–2271. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petronzelli F, Riccio A, Markham GD, Seeholzer SH, Stoerker J, Genuardi M, Yeung AT, Matsumoto Y, Bellacosa A. Biphasic kinetics of the human DNA repair protein MED1 (MBD4), a mismatch-specific DNA N-glycosylase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32422–32429. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004535200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hewish M, Lord CJ, Martin SA, Cunningham D, Ashworth A. Mismatch repair deficient colorectal cancer in the era of personalized treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2010;7:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li LS, Morales JC, Veigl M, Sedwick D, Greer S, Meyers M, Wagner M, Fishel R, Boothman DA. DNA mismatch repair (MMR)-dependent 5-fluorouracil cytotoxicity and the potential for new therapeutic targets. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:679–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00423.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adamson AW, Beardsley DI, Kim WJ, Gao Y, Baskaran R, Brown KD. Methylator-induced, mismatch repair-dependent G2 arrest is activated through Chk1 and Chk2. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1513–1526. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-02-0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang Y, Qin J. MSH2 and ATR form a signaling module and regulate two branches of the damage response to DNA methylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15387–15392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536810100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lin DP, Wang Y, Scherer SJ, Clark AB, Yang K, Avdievich E, Jin B, Werling U, Parris T, Kurihara N, Umar A, Kucherlapati R, Lipkin M, Kunkel TA, Edelmann W. An Msh2 point mutation uncouples DNA mismatch repair and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:517–522. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang G, Scherer SJ, Shell SS, Yang K, Kim M, Lipkin M, Kucherlapati R, Kolodner RD, Edelmann W. Dominant effects of an Msh6 missense mutation on DNA repair and cancer susceptibility. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:139–150. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takahashi M, Koi M, Balaguer F, Boland CR, Goel A. MSH3 mediates sensitization of colorectal cancer cells to cisplatin, oxaliplatin, and a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:12157–12165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.198804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao J, Jain A, Iyer RR, Modrich PL, Vasquez KM. Mismatch repair and nucleotide excision repair proteins cooperate in the recognition of DNA inter-strand crosslinks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:4420–4429. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.