Preface

Viral replication is rapid and robust, but it is far from a chaotic process. Instead, successful production of infectious progeny requires that events occur in the correct place and at the correct time. Rotavirus, a segmented double-stranded RNA virus of the Reoviridae family, seems to govern its replication through ordered disassembly and assembly of a triple-layered icosahedral capsid. In recent years, high-resolution structural data have provided unprecedented insight into these events. In this Review, we explore the current understanding of rotavirus replication and how it compares to other Reoviridae family members.

Introduction

Viruses perform numerous tasks during their replication cycles—from entry into the host cell, to viral protein production and genome replication, to the assembly and egress of nascent particles. Yet, for many viruses, it is not entirely clear how each stage of the replication cycle is controlled so that processes occur at appropriate times. Segmented, double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) viruses of the Reoviridae family seem to achieve such regulation through ordered, stepwise particle disassembly and assembly. This strategy is particularly true for rotaviruses, which are well-studied Reoviridae family members that are important human and veterinary gastrointestinal pathogens. The infectious rotavirus virion is an icosahedral particle composed of three concentric protein layers surrounding eleven dsRNA genome segments1. Loss of the outermost virion layer during entry is intimately tied to membrane penetration2 and subsequent transcription of viral plus-sense RNAs [(+)RNAs] via polymerase complexes (PCs) within the particle interior3, 4. Likewise, during the early stages of rotavirus particle assembly, interaction of the PCs with the innermost protein layer triggers the initiation of viral genome replication5, 6. The subsequent addition of the intermediate and outer layers during particle morphogenesis effectively halts RNA synthesis and directs rotavirus towards host cell egress. The lack of high-resolution structures for rotavirus assembly intermediates previously hampered our understanding of assembly state-mediated regulation of replication. In recent years, several studies using X-ray crystallography and electron cryomicroscopy (cryo-EM) have defined structures of the rotavirus virion, subviral particles, and individual proteins1, 3, 7–12. In this review, we will explore the current model of rotavirus replication, which is based primarily on this new structural information, but is in accordance with numerous biochemical results. Importantly, while this article will focus on rotavirus, the most medically important member of the Reoviridae, we will also incorporate relevant information from other well-studied viruses in this family, such as mammalian orthoreovirus (reovirus) and bluetongue virus (BTV).

Architecture of the rotavirus virion

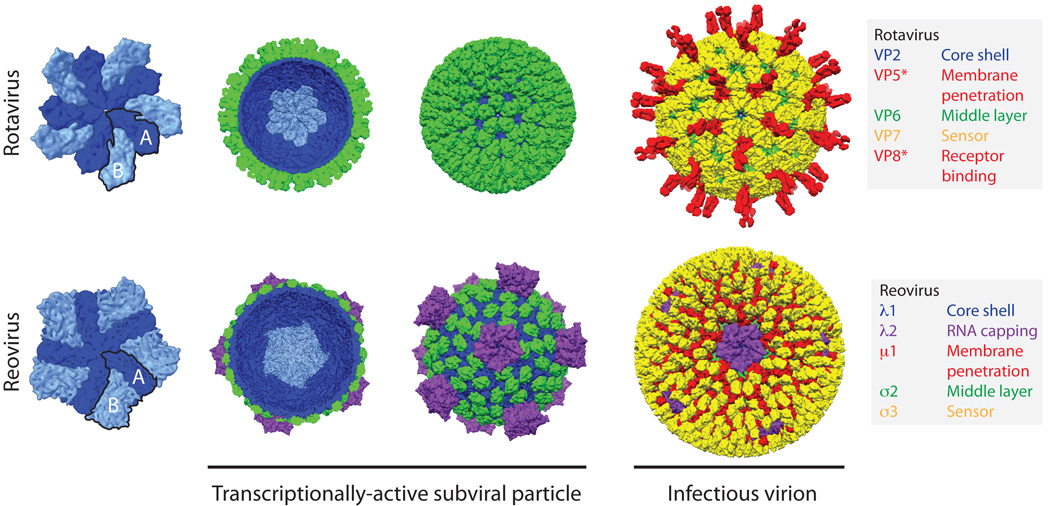

The structures of infectious and sub-viral rotavirus particles have been solved to near-atomic resolution using X-ray crystallography and single-particle reconstructions of cryo-EM images1, 3, 11, 12 (Fig. 1). At approximately 100 nm in diameter, the infectious triple-layered particle (TLP) is relatively large compared to many other non-enveloped, icosahedral viruses. The innermost layer of the TLP, referred to as the core shell, immediately surrounds the viral dsRNA genome. The core shell is composed of 120 copies of VP2 (102 kDa), with each asymmetric unit formed by a dimer (rather than a monomer), and hence the VP2 layer is most accurately described as having T=1 symmetry11. To achieve this organization, VP2 monomers in each dimer unit adopt slightly different conformations. One conformation, VP2-A, converges tightly around the 5-fold vertices, while the other conformation, VP2-B, sits further back and intercalates between adjacent VP2-A molecules11 (Fig. 1). Both forms of VP2 fold into thin, comma-shaped plates; flexible hinge regions between the three subdomains (apical, central, and dimerization) of VP2 allow for subtle structural differences between the A and B conformations11. The extreme N-terminal residues of VP2 (∼1 to 100 of VP2-A and ∼1 to 80 of VP2-B) are not resolved in any known rotavirus structure1, 3, 11, 12. This flexible region of the protein resides within the particle interior, projects towards the 5-fold vertices, and is thought to engage the viral PC that is composed of a single copy each of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (VP1; 125 kDa) and the viral capping enzyme (VP3; 88 kDa)11. Thus, it is currently assumed that most (if not all) 5-fold vertices have a single PC, which is anchored in place via simultaneous interactions with the subdomains of multiple VP2-A and VP2-B conformers and their N-terminal tethers6. While the overall T=1 architecture is conserved for the inner layers of Reoviridae particles, rotavirus is the only member currently known to have such an internal organization11, 13, 14. In contrast, for reovirus and other turreted Reoviridae, the core shell has an externally protruding complex at each 5-fold vertex that is made up of a pentameric viral capping enzyme13 (Fig. 1). For the Reoviridae, the polymerase is bound as a monomer directly to the inside of the core shell, at a defined position slightly off-center from the 5-fold vertices (i.e., there are five identical binding sites at each vertex, only one of which is occupied by the polymerase; this reflects the inherent symmetry mismatch between the monomeric polymerase and 5-fold symmetric core shell)15, 16.

Fig 1. The rotavirus and reovirus virions.

A comparison of the structures of the rotavirus (non-turreted, top) and reovirus (turreted, bottom) particles, colored by functional similarity, not (necessarily) structural homology. The rotavirus double-layered particle (DLP; PDB ID 3KZ4) is the functional equivalent of the reovirus core (PDB ID 1EJ6)—the transcriptionally active subviral particle11, 13. The first view is of a decamer formed by the T=1 inner capsid protein; alternatively colored A (dark blue) and B (light blue) subunits of the 5-fold symmetric decamer illustrate arrangement of the capsid. In outline are a single T=1 asymmetric unit formed by one A conformer and one B conformer. In the second view (a cut-away of the subviral particle) a single decamer (light blue) within the T=1 core is highlighted. Structural evidence suggests that VP1 (not shown; see Fig. 5) binds a specific position on the core near the 5-fold vertices15, 16. The locations of the rotavirus capping enzymes (VP3) within the virion are not known, while the large turrets formed by the reovirus capping enzyme (λ2, purple) are clearly visible in the third view. A continuous shell of rotavirus VP6, and the discontinuous layer of reovirus σ2 (both in green), stabilize the inner capsid and interface with the outer capsid proteins3, 11, 13. The final view shows the infectious rotavirus virion (PDB IDs 3IYU and 3N09) is coated with the trimeric VP7 protein (yellow), and decorated with the VP5*/VP8* spike complex (red) that mediates attachment and entry1. In contrast, the reovirus core is covered with a layer of the trimeric membrane penetration protein, µ1 (red), which is studded with the chaperone protein σ3 (yellow) to form the infectious virion (PDB ID 2CSE)19. The flexible trimeric reovirus attachment fiber, σ1 (cartooned), extends from the 5-fold turrets has not been fully resolved in any particle reconstruction106, but the structure of the head domain has been solved independently107. The diameter of the mature virion in both cases is approximately 80 nm (excluding spikes)3, 19.

Surrounding the rotavirus VP2 shell are two additional protein layers, both of which have T=13 icosahedral symmetry (Fig. 1). The intermediate layer is relatively thick compared to the other two layers and is made up of 260 trimers of VP6 (monomer, 45 kDa). VP6 is composed of two domains, a distal jelly-roll β-barrel and a proximal α-helical pedestal, both of which participate in extensive contacts with neighboring subunits as they twist around each other to form a trimer11, 17. The symmetry mismatch with the underlying VP2 core shell results in five distinct positions for VP6 trimers. Binding of VP6 to VP2 results in a dramatic stabilization of the very fragile core. Thus, VP6 is functionally analogous to the discontinuous σ2 protein clamps that bridge the subunits of the core shell in the reovirus particle13. VP6 also serves as an adaptor for the rotavirus outer capsid proteins, which are critical for attachment and entry into a host cell. Specifically, 260 trimers of the glycoprotein VP7 (monomer, 37 kDa) sit directly on top of the VP6 trimers and form a continuous, perforated shell. VP7 trimers are dependent on bound calcium ions for stability; two calcium ions are held at each subunit interface, requiring six total bound ions per trimer7. Arm-like extensions formed by the VP7 N-termini account for nearly all contacts with VP61, 3 (Box 1). In addition to allowing VP7 to grip the intermediate layer, the N-terminal arms of VP7 also create lattice contacts with other VP7 trimers, thereby reinforcing the outer shell integrity and allowing cooperative interaction of adjacent VP7 trimers (Box 1)3. Protruding through the VP7 layer on the rotavirus virion are 60 trimeric spikes 120 Å in length that emanate from the peripentonal channels of the VP6 layer. These spikes are formed by the viral attachment protein, VP4 (88 kDa), and (as detailed in a later section) they undergo significant conformational changes during penetration of the host cell membrane. Because of their key roles in infectivity, antibodies generated against VP4 and VP7 effectively neutralize rotavirus. Thus, a binary serotype system (GxP[y]) is often used to classify and describe individual rotavirus strains18 (Box 2), analogous to the HxNy designation of influenza virus strains.

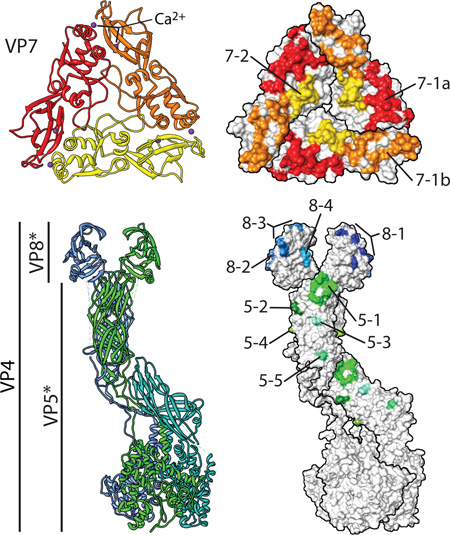

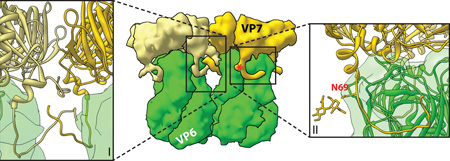

Box 1. The grip-arm mode of VP7 assembly.

Despite occupying a position directly on top of the VP6 trimers, the bottom face of VP7 and the top of VP6 share minimal contacts (rotavirus DLP “recoated” with recombinant VP7; PDB IDs 3GZT and 3GZU)3. Instead, the three flexible N termini of a VP7 trimer latch onto small protrusions formed by a loop in the VP6 β-jellyroll domain3. The N terminus of mature VP7 begins at residue Q51 (1–50 are the cleaved signal peptide). Residues 58–62 interact with VP6 to effectively extend the β-sheet of VP6 by an additional strand (inset II), while residues 63–78 curve under the VP6 protrusion and lead up into the main VP7 structure3. A glycosylation site, N69, in VP7 that is conserved among many group A rotaviruses is actually within the grip-arm and below the virion surface (red asterisk; also labeled in inset II)3. In certain VP7 conformers, additional N terminal residues (51–57) can be modeled and appear to cross-over between VP7 trimers and mediate many of the trimer-to-trimer contacts of the VP7 layer (inset I)3. This capsid protein ‘networking’ is similar to that seen with other virions, notably that of papillomavirus, in which N- and C-terminal arms lash the pentameric capsomeres together105. Thus, the flexible N-terminal arms of VP7 are probably responsible for many of the interactions that stabilize the outer capsid on the rotavirus virion. It is likely that these interactions are weak for a single VP7 monomer, consistent with the requirement for calcium-dependent trimerization of VP7 to assemble84. Calcium binding, and the context-sensitive interaction with VP6 (and between VP7 trimers), appear to have evolved as an exquisite mechanism to govern the highly cooperative assembly and uncoating properties of the rotavirus outer capsid2, 84.

Box 2. Structurally defined rotavirus epitopes.

The outer capsid proteins VP7 and VP4 (including the VP4 cleavage products, VP5* and VP8*) are the primary targets of rotavirus-neutralizing antibodies. The VP7 glycoprotein (G-antigen; shown in red/orange/yellow ribbon) and the protease-sensitive spike protein, VP4 (P-antigen; shown in blue/green/cyan ribbon), are used to classify rotavirus strain serotype (e.g., G1P[8]) based on sequence comparison and reactivity with neutralizing antibodies. Mapping of antibody escape mutations has lead to the identification of several discrete epitopes in each outer capsid protein. The recent structures have allowed coherent, structure-based epitopes to be defined. For example, six epitopes (A–F) were mapped to VP7 by neutralization escape. By plotting these targets onto the surface of the VP7 trimer, it is immediately apparent that there are, in fact, only two unique areas that seem to be targeted by neutralizing antibodies7. Epitope 7–1 (red and orange) lies at the corners of each trimer and comprises residues from two adjacent VP7 subunits (and can be subdivided into 7–1a [red] and 7–1b [orange] by this fact)7. Antibodies that target 7–1 by and large neutralize the virus by stabilizing the capsid and preventing uncoating2, 7; indeed, epitope 7–1 includes several amino acids proximal to one of the calcium (purple) binding sites that maintain the trimeric conformation of VP7. Epitope 7–2 (yellow) is in the flexible region in the center of each VP7 subunit; there is less certainty about the mechanism(s) of neutralization by antibodies that target this epitope. In the mature virion, VP4 is cleaved by trypsin into VP5* and VP8*. VP8* has four structurally defined epitopes (blue)9. Most neutralizing antibodies directed against VP8* block virus attachment9, 27. VP5*, the membrane penetration protein, has five structurally defined epitopes (green)8. The specific mechanism of neutralization of most anti-VP5* antibodies has not been determined; however, those directed against epitope 5–1, at the apical hydrophobic loops (Fig. 3), appear to block association of VP5* with membranes (and, presumably, membrane penetration)34, 38.

A comparison of reovirus and rotavirus virions, as representatives of the turreted and non-turreted Reoviridae respectively, indicates that their outermost virion layers are much more distinct than their relatively conserved T=1 core shells. When diagramed side-by-side, it is clear that the overall organization of outer capsid proteins is highly dissimilar and that functions are not parsed among proteins in the same way (Fig. 1). Specifically, reovirus encodes its attachment and membrane penetration functions in two different proteins (σ1 and µ1, respectively) that do not occupy the same positions on a virion as rotavirus VP419. Furthermore, the reovirus sensor protein (σ3), involved in virion disassembly, does not self-associate and does not form a continuous outer shell like rotavirus VP7, but instead decorates trimers of the penetration protein µ119, 20. These differences in the outer capsid may be an evolutionary result of distinct entry requirements. However, there are several commonalities between rotavirus and reovirus entry that belie these architectural differences and highlight that these viruses have effectively solved the same problem in two unique ways.

Changes in the outer capsid drive entry

Rotaviruses infect enterocytes of small intestinal villi and replicate exclusively in the cell cytoplasm (Fig. 2). Newly-assembled rotavirus virions are not fully infectious; for membrane penetration, the VP4 spike protein must be proteolytically cleaved (primed) by trypsin-like proteases of the host gastrointestinal tract into two fragments, VP8* (28 kDa) and VP5*21 (60 kDa). These cleavage products remain non-covalently associated with each other on the mature virion surface (Fig. 3). Structural analysis of VP4 from TLPs before and after trypsin cleavage revealed a rigidification of the spike upon proteolysis22, 23. The primed spike contains an unusual mix of trimeric, dimeric, and asymmetric elements1, 24 (Fig. 3). Specifically, the proximal VP5* portion of the spike is trimeric at its base, where it is sandwiched between the VP6 and VP7 layers1, 24, 25. As VP5* extends away from the virion, however, two of the three subunits form an extended pair, while the third VP5* subunit lays nearly flat to the virion surface1. Two VP8* molecules cap distal ends of the two upright VP5* subunits and project their extended N-termini down into the base of the spike, while the third VP8* is presumed to dissociate from the virion1. Consistent with its position at the tip of the cleaved spike, VP8* appears to mediate host cell attachment for many rotavirus strains26. Consequently, most neutralizing antibodies that target VP8* block virus attachment (Box 2)27. The structure of the VP8* fragment alone has been solved for several different rotavirus strains9, 28–30. This protein has a galectin-like fold and, for many strains, can bind sialic acid moieties in vitro9, 29, 30. However, not all rotavirus strains require terminal sialic acid for attachment in cell culture experiments31, 32. This observation suggests that alternative cellular surface molecules can serve as functional receptors for rotavirus, possibly including glycans with internal sialic acid groups. An ongoing focus of many laboratories is the identification and characterization of these undefined receptors31.

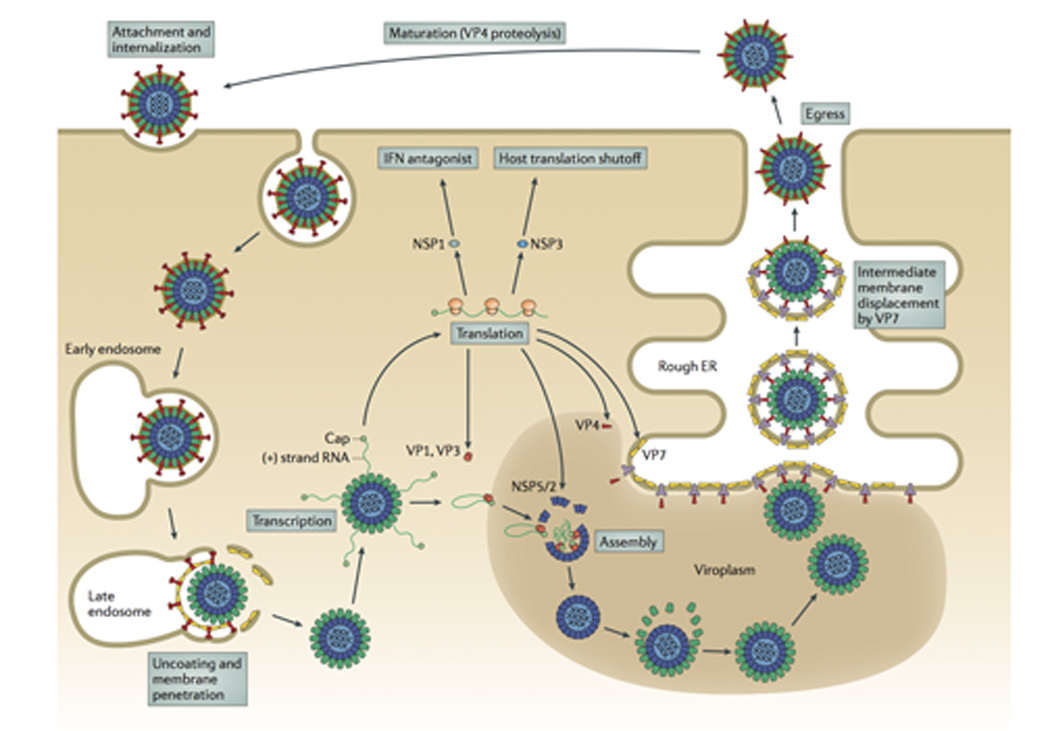

Fig. 2. The rotavirus replication cycle.

The rotavirus virion first attaches to the target cell; many strains bind cell-surface sialic acids through VP8* at the tips of the virion spikes (red). Non-clathrin, non-caveolin mediated endocytosis delivers the virion to the early endosome. There, reduced calcium concentrations are thought to trigger uncoating of VP7 (yellow) and membrane penetration by VP5* (red). Loss of the outer capsid and release of the DLP into the cytosol activates the internal polymerase complex (VP1 and VP3) to transcribe capped (+)RNAs (grey) from each of the eleven dsRNA genome segments. (+)RNAs serve either as mRNAs for viral protein synthesis by cellular ribosomes or as templates for (-)RNA synthesis during genome replication. Two non-structural proteins, NSP2 and NSP5, interact to form large inclusions (viroplasms; brown) that sequester components required for genome replication and sub-viral particle assembly. Genome packaging is initiated when VP1 (and, presumably, VP3) complex with the 3’ end of viral (+)RNAs. It is currently thought that interactions among the eleven (+)RNAs drive formation of the “assortment complex”. Condensation of the inner capsid protein, VP2 (light blue), around the assortment complex triggers dsRNA synthesis by VP1. The intermediate capsid protein, VP6 (green), then assembles onto the nascent core to form the DLP. Assembly of the outer capsid is not well understood; the current model proposes that interaction with the viral transmembrane protein NSP4 (dark blue) recruits DLPs and the outer capsid protein VP4 (red) to the cytosolic face of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane. Through an undefined mechanism, the DLP/VP4/NSP4 complex buds into the ER. Subsequent removal of the ER membrane and NSP4 permits assembly of the ER-resident outer capsid protein VP7 and formation of the triple-layered virion (see Fig. 6). Release from the infected cell exposes the virion to trypsin-like proteases of the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in the specific cleavage of VP4 (wiggly red) into VP5* and VP8* (straight red) to produce the fully infectious virion.

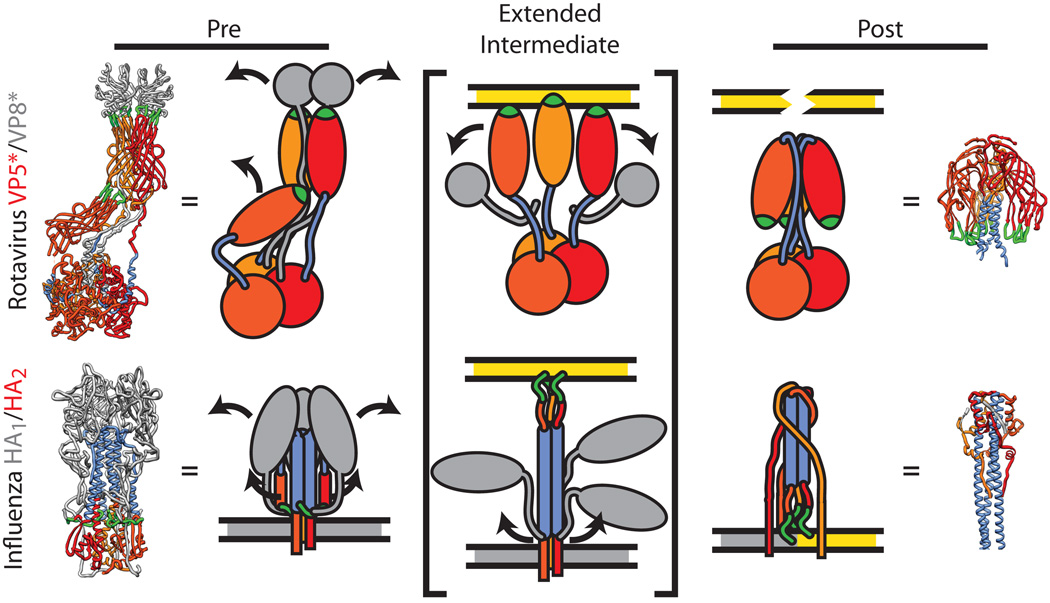

Fig. 3. Conformational rearrangements of the rotavirus spike during entry.

A comparison of the refolding of the rotavirus spike (VP5*/VP8*) during membrane penetration with the refolding of the influenza hemagglutinin (HA) during membrane fusion. The rotavirus spike (top, PDB IDs 3IYU and 1SLQ) is formed by three subunits of VP5* (warm colors) and capped by two subunits of VP8* (grey). The hydrophobic loops thought to interact with the membrane (green) and the sequence in VP5* that will refold into a coiled-coil (blue) are highlighted. The influenza HA protein (bottom, PDB IDs 3HMG and 1HTM) is colored similarly: The HA2 trimer (warm colors) is held below the three receptor-binding subunits, HA1 (grey), with the post-fusion coiled-coil (blue) and fusion peptide (green) highlighted. During penetration (or fusion), the meta-stable ‘pre’ state is perturbed, resulting in dissociation of the receptor-binding subunits, extension of the penetration protein, and insertion of the hydrophobic peptide into the host cell membrane (yellow). The stability of the ‘post’ state drives a fold-back reorganization of the penetration protein36. In the case of influenza HA2, this places the host (yellow) and viral (grey) membranes into close opposition and drives fusion36. How refolding of VP5* accomplishes membrane penetration is currently not known. Dissociation of the VP7 layer appears to trigger VP5* refolding38, 44, but it is also not known if VP5* performs membrane penetration while still particle associated or as a discrete complex.

In structures of the intact, primed virion, the VP5* spike conformation appears static, yet several studies have shown that this protein has the capacity to undergo a significant molecular movement. A requirement for membrane penetration is the exposure of three hydrophobic loops in VP5*, which are tucked below the VP8* lobes in the two upright conformers, while the loops of the third VP5* nestle into the base of the upright VP5* subunits33, 34 (Fig. 3). When soluble VP4 is proteolytically cleaved in vitro, it bypasses the spike conformation altogether and forms an inverted, highly-stable trimer that corresponds to the central region of VP5*8, 35; it has been proposed that this is the ‘post-penetration’ conformation of VP5*8. Rather than the elongated, quasi-asymmetrical spike, this umbrella-shaped structure folds backward onto itself and has at its core a three-helix coiled-coil8 (Fig. 3). This apparent ‘fold back’ mechanism, which is required to expose the hydrophobic loops in VP5*, closely parallels the maturation and refolding pathway that occurs in many viral membrane fusion proteins during entry1, 8, 36 (Fig. 3). In particular, a precursor protein (e.g., VP4) is proteolytically primed to form a meta-stable intermediate (the spike), which is then triggered to interact with a target membrane and refold (the VP5* umbrella) to destabilize the membrane1, 8, 33 (Fig. 3). Support for this model is growing, as it has recently been reported that formation of the inverted VP5* trimer accompanies infectious rotavirus entry37. Furthermore, there is a specific correlation between the rearrangement of VP5* and liposome binding in vitro38. Given that rotavirus has no envelope of its own to fuse to the host cell, it is not fully understood how these structural changes in VP5* result in membrane penetration. Although mechanistically distinct, the myristoylated reovirus penetration protein, µ1, forms ∼7 nm pores in model membranes39, 40. It may be the case that VP5* is capable of perforating the cellular membrane via its hydrophobic loops in much the same way as reovirus µ1, albeit through an entirely different physical mechanism.

VP7 appears to be the key regulator of the conformation and membrane penetration activity of VP5*. Once assembled onto the particle, the VP7 layer limits the access of trypsin to VP4, thereby allowing the protease to cleave only the region that bridges VP8* and VP5*1, 41. As described above, proteolytic processing of VP4 in the absence of VP7 and the viral particle is more extensive and leads directly to the formation of the post-penetration state of VP5*8, 35. The VP7 layer likely functions to arrest and stabilize VP5* in the upright spike conformation to allow for viral attachment1. During rotavirus entry, it has been observed that the TLP is internalized via endocytosis and trafficks to the early endosome37, wherein it is predicted that the low calcium concentration triggers VP7 disassembly42, 43. The dissociation of VP7 then serves as a cue for VP5* rearrangement and allows for the virion to penetrate the endosomal membrane38, 44. Consistent with this model, bafilomycin A and extracellular CaEGTA, both of which increase endosomal calcium concentrations, effectively block rotavirus entry37, 42. Furthermore, inhibition of VP7 uncoating by a neutralizing antibody also blocks membrane penetration2, suggesting that VP7 disassembly is an obligate step prior to membrane penetration by VP5*.

Similar to rotavirus, reovirus also utilizes endocytosis to trigger infectious entry, but for an entirely different reason. Proteolysis of the reovirus sensor protein, σ3, by endosomal cathepsin partially disassembles the virion and activates the membrane penetration activity of µ145, 46. Thus, both rotavirus and reovirus have evolved endosome-sensing proteins (VP7 and σ3, respectively) that detect different features of the same intracellular compartment to trigger uncoating and engage the membrane penetration apparatus. The net result of attachment, uncoating and endosomal membrane penetration is the release of a large subviral particle into the host cell cytosol.

Uncoating induces transcription by DLPs

For rotavirus, the double-layered particle (DLP) is delivered to the target cell following entry (Fig. 2). Viral PCs within the DLP are transcriptionally-active and immediately commence synthesis of eleven species of capped, non-polyadenylated (+)RNAs using the minus-strands [(-)RNAs] of the dsRNA genome segments as templates47 (Fig. 4). The catalytic subunit of the PC for RNA synthesis is VP1, a hollow, globular enzyme whose structure is composed of a central, conserved ‘right-handed’ polymerase domain, surrounded by N- and C-terminal domains unique to the Reoviridae10, 48. VP1 uses the (-)RNA of the dsRNA genome as a template for the synthesis of nascent (+)RNA transcripts. The first RNA exit tunnel of VP1 directs the nascent (+)RNA towards VP3 (discussed below) and release from the virus particle, while the second directs the genomic (-)RNA back into the core where it re-associates with the genomic (+)RNA. Thus, transcription by VP1 is fully conservative. The presence of an RNA cap-binding site near the RNA template entry tunnel suggests a mechanism whereby VP1 may bind and orient the dsRNA genome to allow for template recycling during transcription10. Immediately following synthesis of the (+)RNAs, but prior to their extrusion from the DLP via channels at the 5-fold vertices, the (+)RNA molecules acquire a 5’ cap through the activities of VP349. While we do not yet have a structure for rotavirus VP3, studies of the BTV capping enzyme (VP4; 71 kDa) have shed light on the putative functional domains of this protein50. BTV VP4 is an hourglass-shaped protein that contains four domains50. Like rotavirus VP3, it is responsible for the entire chemistry of viral RNA capping: guanylylation, N-7-methylation, and 2’-O-methylation. However, the RNA triphosphatase activity that precedes capping has yet to be clarified by the BTV VP4 structure50. For reovirus, RNA triphosphatase activity is encoded in a separate protein, µ2 (83 kDa), that is a minor component of the core particle and interacts with the λ3 polymerase51; rotavirus does not possess a minor capsid protein, suggesting that triphosphatase activity resides in one of the PC components (VP1 or VP3). Overall, the BTV VP4 structure has suggested an ‘assembly line’ model for capping, in which the 5’ end of the RNA is transferred from one domain to the next to perform the successive reactions that generate the final m7GpppG50 (Fig. 4). Recent structural evidence suggests that rotavirus VP1 is located at a discrete position very near the 5-fold channels in the DLP16. As such, VP3 likely performs its capping activities in a relatively small space prior to transcript ejection (Fig. 4). In contrast, the newly-made (+)RNAs of turreted Reoviridae are capped as they navigate a pentameric gauntlet of capping enzymes as they exit the transcribing particle15, 52, 53.

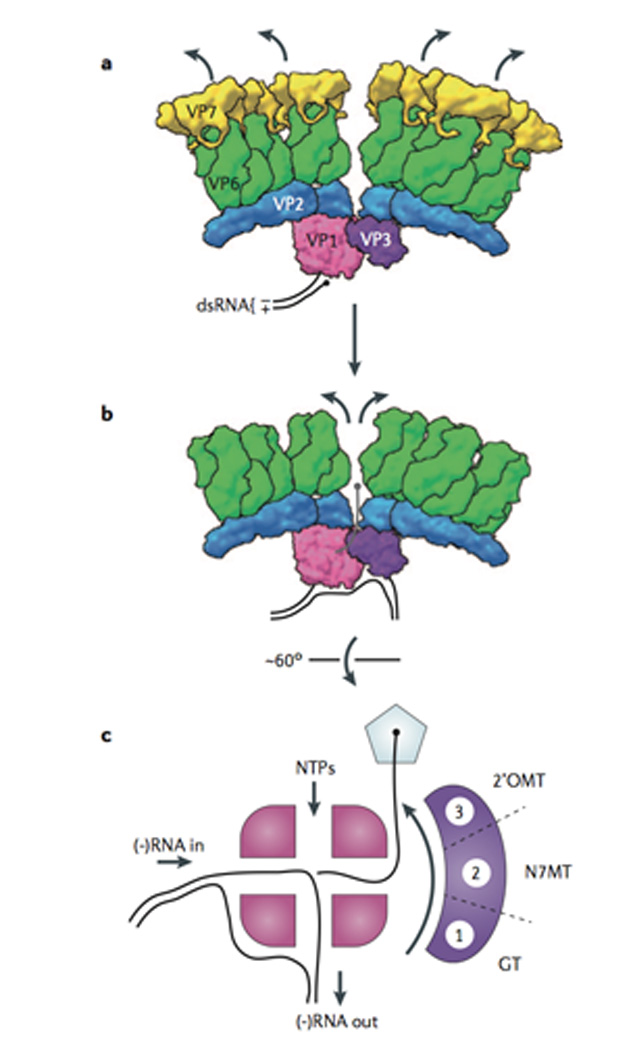

Fig. 4. Conformational changes of the sub-viral particle that trigger transcription.

(A) Model for the transcriptionally inactive rotavirus virion. Prior to entry, the VP7 layer (yellow) appears to suppress transcription by the viral polymerase complex (PC), VP1 (pink) and VP3 (purple)3, 4. Current data suggest that a single PC resides near almost all of the 5-fold channels in a rotavirus particle16. In this inactive state, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase VP1 (PDB ID 2R7U) is likely bound to the 3’ end of the (-) strand of the dsRNA, poised for transcription of the (+)RNA10. (B) The VP7 layer (PDB ID 3IYU) dissociates during entry, resulting in the upward- and outward-movement of the VP6 (green) and VP2 (blue) layers (PDB ID 3N09) of the particle3, 54. This movement results in expansion of the 5-fold channel and permits extrusion of (+)RNA transcripts4. (C) Model for the passage of the nascent (+)RNA transcript through the PC and out of the particle. The four tunnels of VP1 permit the input (-)RNA and NTPs to support synthesis of the new (+)RNA, and the re-formation of the parental dsRNA pair10. The 5’ end of the (+)RNA must rapidly be recruited and capped (black sphere) by VP3 prior to exit through the 5-fold channel (pentagon). Biochemical data, and comparison with the BTV capping enzyme (VP4; used here as a surrogate for rotavirus VP3; PDB ID 2JH8)50, suggest that VP3 is a multi-domain protein that successively modifies the 5’ end through (1) guanylyltransferase, (2) N-7-methyltransferase, and (3) 2’-O-methyltransferase activities to generate the mature rotavirus 5’ cap structure.

It is still not clear how changes that occur in the DLP upon loss of the outer capsid induce transcription. Structural evidence suggests that removal of VP7 causes a dilation of the 5-fold channels in the DLP, thereby providing conduits for the influx of ions and nucleotides and the efflux of transcripts3, 54. Specifically, upon recoating of a DLP with recombinant VP7, the VP6 trimers immediately surrounding the 5-fold vertices move down and inward3. This motion also drives VP2 inward, thereby constricting the channel diameter3. These structural changes detected in the presence of VP7 are similar to those observed with anti-VP6 antibodies that inhibit transcription by DLPs in vitro55, 56. Thus, it is presumed that uncoating of the outer capsid layer during entry results in an outward movement of VP6 and VP2 at the 5-fold vertices and an opening of the channel3 (Fig. 4). It is not clear, though, if merely increasing the diameter of the 5-fold channels is sufficient to induce (+)RNA synthesis, or instead, if a specific signal is relayed to the internally tethered PCs. An alternative hypothesis for transcriptional activation of the DLP infers that VP1 is sensitive to conformational changes in VP2 that occur during uncoating. In support of this idea, the activity of VP1 during genome replication (dsRNA synthesis) is tightly controlled by interactions with VP26, 57–60 (discussed below). As such, it is interesting to speculate that loss of VP7 transmits structural changes through VP6, which in turn influences the interaction of VP1 with VP2 and enables polymerase activity.

Genome replication and core assembly

Nascent rotavirus (+)RNAs made within DLPs serve dual roles during the rotavirus replication cycle, acting as mRNAs for protein synthesis and as templates for genome replication (Fig. 2). The function of any given (+)RNA during infection is thought to be determined by its intracellular localization61. Products of transcription from incoming DLPs accumulate in the cytosol and are available for translation into viral proteins by host ribosomes. Two viral nonstructural proteins (NSP2 and NSP5) are thought to co-localize around transcribing DLPs, nucleating the formation of inclusion bodies termed viroplasms. The structure of NSP2 (35 kDa) has been solved; it forms donut-shaped octomers that bind both RNA and NSP562, 63. The largely unstructured phosphoprotein NSP5 (22 kDa) has been shown to self-associate, and interacts with RNA and NSP264, 65. The numerous self- and partner-specific interactions of NSP2 and NSP5 suggest that viroplasms may form as large, semi-regular networks designed to sequester viral RNAs and capsid proteins for assembly in to nascent virions. Consistent with this model, these RNA-dense bodies are the sites of early virion assembly and further (+)RNA transcription by nascent DLPs. Viroplasm-associated rotavirus (+)RNAs are selectively packaged into assembling VP2 cores and replicated by VP1 into the dsRNA genome61.

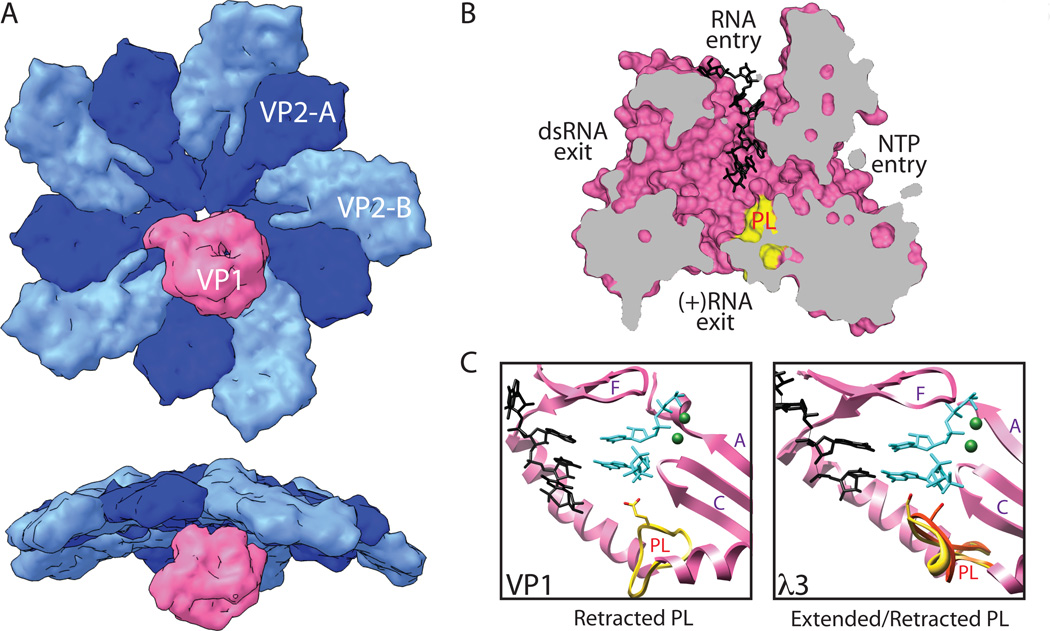

While the order of protein and RNA interactions that occur during packaging and genome replication are not completely understood, cumulative biochemical and structural data suggest a working model (Fig. 5A). First, individual copies of VP1 (perhaps in complex with VP3) bind to the 3’ termini of the viral (+)RNAs, creating eleven different enzyme-RNA complexes10, 58. The structure of recombinant VP1 in complex with an oligonucleotide representing the 3’ terminus of a (+)RNA revealed that it specifically recognizes a conserved four base sequence (UGUG)10 (Fig. 5B). Mutation of VP1 to disrupt multiple base-specific interactions diminishes dsRNA synthesis by the polymerase in vitro, likely by abolishing the initial RNA recognition and binding events66. The 3’ end of the (+)RNA is held near the central active site through interactions with the phosphate backbone in a sequence-independent manner, but is positioned out-of-register with the catalytic site10 (Fig. 5B–C). Thus, the PC/(+)RNA complexes that first form in the viroplasm are thought to be catalytically inactive; the VP1 component would have to undergo one or more conformational changes to initiate synthesis of dsRNA.

Fig. 5. Rotavirus core assembly is coupled with genome replication.

(A) Model for (+)RNA packaging, core assembly, and dsRNA genome replication. In the viroplasms, it is assumed that VP1 and VP3 associate to form polymerase complexes (PCs). VP1 also binds a specific sequence at the 3’ end of each of the 11 rotavirus (+)RNAs, but remains catalytically inactive. Comparisons with reovirus and influenza have suggested a mechanism in which RNA-RNA interactions among the (+)RNAs nucleate complexes containing all of the segments and associated PCs. VP2 then self-assembles and engages VP1; this triggers dsRNA synthesis activity by VP1. (B) Structure of VP1 with bound (+)RNA, but held in an inactive state (PDB ID 2R7R). The functions of the four tunnels extending to the large catalytic center of VP1 are identified. Prior to interaction with VP2, VP1 can bind to the 3’ end of (+)RNAs (black) with high affinity, but remains auto-inhibited10, 58. Also shown is the priming loop (PL) (yellow), a structural feature that is thought to be involved in regulating polymerization by VP1. (C) Model for conformational changes in the VP1 priming loop that initiate dsRNA synthesis. In the structure of VP1, the priming loop (PL) (yellow) used to stabilize a priming nucleotide in the catalytic center is retracted and out of place. It is thought that interaction of VP1 with VP2 promotes a conformational change in this loop that allows it to stabilize the priming nucleotide. Here we have used the structure of reovirus λ3 with bound template and nucleotides (PDB ID 1N1H) in the catalytic center as a surrogate for activated VP148; note that the priming loop supports a priming nucleotide only in its extended conformation (yellow) and not in its retracted state (red). Polymerase motifs A, C, and F are indicated. For sake of reference, the locations of nucleotides and cations have been modeled into the catalytic center of VP1. (D) Model for the interaction of rotavirus VP1 with the inner surface of the core shell. Recent structural evidence, and information obtained with reovirus, suggest that VP1 (pink) binds to a specific position off center of a VP2 decamer (blues)15, 16. Its 5-fold symmetry suggests that there are potentially 5 VP1 binding sites per decamer, although it is likely that only a single polymerase is associated with each. The RNA capping enzyme, VP3 (not shown) is likely held in close proximity to VP1, but has not been observed. Interaction with VP2 may transmit information to VP1 (e.g., through the priming loop) that activates the polymerase to synthesize (-)RNA using the (+)RNA as a template, resulting in the formation of the dsRNA genome59.

The auto-inhibited RNA-binding mechanism of VP1 may produce an accumulating population of catalytically inactive PC/(+)RNA complexes that are available for assortment into assembling cores (Fig. 5A). The current model for rotavirus (+)RNA assortment borrows heavily from the more established mechanisms of segmented (-)RNA viruses. Influenza A virus, in particular, has multiple genome segments, each of which contains a central open reading frame (ORF) flanked by short, conserved 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions (UTRs). It has been proposed that the genomic (-)RNAs of influenza are arranged in a specific pattern according to base-pairing interactions between the UTRs of different segments67. A recent report, in which the UTRs are swapped between influenza genome segments to influence how they are packaged, supports this model68. Additionally, reverse genetics systems for reovirus have been used successfully to package and replicate two reporter genes by replacing the native ORF of a given segment with that of a transgene, suggesting that Reoviridae genome packaging may be dependent entirely on the UTR sequences69, 70. Similar to the influenza genome, rotavirus (+)RNAs appear to adopt a looped ‘panhandle’ conformation with base-paired 5’ and 3’ ends71, 72. While it has not been formally demonstrated that the UTRs of rotavirus (+)RNAs drive gene-specific interactions during packaging, they are obvious targets for future experimentation.

Following assortment, an assembling VP2 core shell engages the polymerase component of PC/(+)RNAs complexes, thereby activating the enzymes to initiate (-)RNA strand synthesis to produce the dsRNA genome (Fig. 5A, D). In vitro biochemical studies have shown that the inwardly-protruding VP2 N-termini play a role in polymerase activation59, 60, but that residues of the core shell proximal to the 5-fold vertex are important for specific interaction of a given VP2 with its cognate VP16. The relative sizes of VP1 and VP2, and comparison with reovirus15, suggest that VP1 likely contacts multiple VP2 molecules (both A and B forms) at a given 5-fold vertex (Fig. 5D). The further observation that maximal in vitro dsRNA synthesis occurs with a 10:1 molar ratio of VP2:VP1, leads to the hypothesis that a decameric assembly of VP2 activates each VP1 monomer59. During the process of dsRNA synthesis, however, VP2 must ultimately self-assemble to form a complete, closed T=1 shell. In this model, the rotavirus core would be composed of twelve VP2 decamers with eleven internally tethered PC/(+)RNA complexes and a single empty vertex11.

The mechanism by which VP2 activates VP1 to initiate dsRNA synthesis is currently not well understood. Some insight into this process has been provided by comparing the structure of an auto-inhibited VP1 with that of a catalytically active form of the reovirus polymerase, λ310, 48. An extended loop is seen between the fingers and palm subdomains of the central polymerase domain in both enzymes (Fig. 5C)10, 48. In λ3, the loop appears to operate as a platform for stabilizing a priming nucleotide48. In the VP1 crystal structure, however, this so-called ‘priming loop’ bends away from the active site by about 90°, leaving it in a retracted state that is incapable of binding nucleotides10. Based on this observation, it is thought that interaction with VP2 causes structural changes in VP1 that include lifting the priming loop, and repositioning of the 3’ terminus of the (+)RNA to be in-register with the catalytic site10. Regardless of the mechanism, regulation of VP1 activity by VP2 is critical for rotavirus replication, as it likely prevents premature synthesis of dsRNA and allows the virus to precisely coordinate the stages of RNA packaging, genome replication, and core shell assembly.

In addition to regulating the timing of dsRNA synthesis by VP1, rotavirus must also control the assembly of its capsid proteins. When expressed in the absence of other rotavirus proteins, VP2 and VP6 will each spontaneously self-assemble into capsid-like structures17, 73, 74. It seems likely that rotavirus must employ a specific mechanism to prevent uncontrolled self-assembly of its structural proteins during infection. The viroplasm-forming proteins, NSP2 and NSP5, have each been shown to interact with a subset of the structural proteins, (+)RNA, and each other. As such, it is likely that these two non-structural proteins help govern particle assembly. NSP5 has been shown to interact with VP2 in co-immunoprecipitation assays and may modulate the assembly of VP6 onto the core shell75. The addition of NSP5 to DLP-like structures actively displaced VP6 from the core shell in vitro, suggesting that this phosphoprotein may compete for binding sites on VP275. Thus, NSP5 might act to negatively regulate VP6 assembly, while the competing interactions of other viral proteins with NSP5 may further regulate this activity. To date, similar regulation of VP2 assembly has not been observed. However, NSP2 has been shown to interfere with VP2-dependent VP1-mediated dsRNA synthesis in vitro, suggesting that it might function to control interactions among VP1, VP2, and (+)RNA76, 77. Additional characterization of the network of protein and RNA interactions within the viroplasm is vital to our understanding of how rotavirus carefully moderates particle assembly to ensure that (+)RNAs are properly encapsidated prior to their replication.

Regulation of outer capsid assembly

One of the least understood aspects of rotavirus replication is the process by which the DLP acquires the outer capsid. To fully assemble, the DLP must exit the viroplasm, associate with the spike protein, VP4, and then breach the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane to gain access to the VP7 glycoprotein. Rotavirus appears to be the only Reoviridae member to encode a structural glycoprotein. In fact, this property is exceeding rare for non-enveloped viruses in general, as they largely assemble within the cytoplasm or nucleus without involving budding steps in morphogenesis. Much in the same way that uncontrolled assembly of VP2 or VP6 would impair genome replication, premature addition of VP7 to the DLP would stifle replication by silencing (+)RNA transcription. By compartmentalizing VP7 to the ER, rotavirus ensures that DLPs are only converted to TLPs after they leave the confines of the viroplasm.

The viral non-structural protein NSP4 (20 kDa) is a key regulator of outer capsid assembly. NSP4 is an integral membrane protein that accumulates in the ER near the cytosolic viroplasms. The N terminus of the protein extends into the ER lumen and is both glycosylated and forms intramolecular disulfide bonds78. A single-pass transmembrane sequence leads into a cytosolic coiled-coil motif that causes NSP4 to tetramerize78, 79. The largely unstructured C terminus of NSP4 has been shown to bind both the DLP (through VP6) and VP480–83, suggesting that it may help to chaperone the otherwise weak DLP-VP4 and VP4 trimerization interactions84. While a specific mechanism for the extraction of DLPs from the viroplasm is not known, we postulate that interaction with NSP4 may recruit DLPs into the outer capsid assembly pathway. It is suspected that unassembled VP7 interacts with the ER-luminal or transmembrane region of NSP485, 86. Through an unknown mechanism, VP7 is also retained in the ER via interaction with its cleaved signal peptide87.

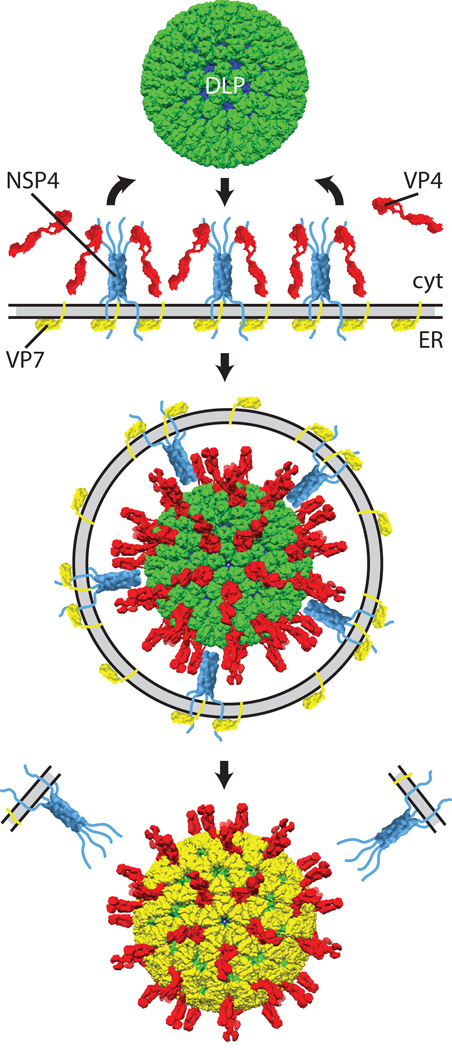

Although the data are incomplete, the current model for outer capsid assembly is as follows (Fig. 6). NSP4 recruits both DLPs (from nearby viroplasms) and VP4 to the cytosolic face of the ER membrane. Successive interaction of the DLP with surrounding NSP4 tetramers results in ER membrane deformation and budding of the DLP/VP4/NSP4 complex into the ER. Thereafter the membrane is removed and VP7 assembles onto the particle, thereby locking VP4 into place. Biochemical and structural data support this order of assembly. Immunoelectron- and fluorescence-microscopy of infected cells indicates that VP4 accumulates in the narrow region between the viroplasms and ER, possibly because it is recruited by NSP488, 89. In vitro assembly of the outer capsid onto DLPs requires that the addition of VP4 before VP7 to generate infectious particles; the reverse order excludes VP4 from assembly84. Finally, the TLP structure indicates that the bulbous VP4 foot is likely too large to be inserted through the narrow opening formed by VP7 at the peripentonal channels1.

Fig. 6. Rotavirus penetrates a second membrane during virion assembly.

Model for the acquisition of the rotavirus outer capsid via budding and penetration through the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane. After assembly in the viroplasm, DLPs (green) are recruited to the cytosolic face (cyt) of the ER membrane through interaction with the C-terminal tails of the NSP4 (light blue) tetramer (PDB ID 1G1J)79–81. The C-terminal tails of NSP4 likely bind and recruit the VP4 spike protein (red) that is synthesized in the cytosol83. Simultaneously, in the ER lumen, outer capsid protein VP7 (yellow) associates with its cleaved signal peptide (yellow, embedded in ER membrane) and NSP485–87. Successive interaction of NSP4 with the DLP may induce the ER membrane to wrap around the DLP causing it to bud into the ER. Enveloped intermediate particles have been isolated and found to contain DLPs and VP4 in their lumen, transmembrane NSP4, and VP7 associated with their exterior face (second particle)90. Through an undefined mechanism—presumably involving VP795—the ER membrane (along with NSP4) is removed from the particle, and allows VP7 to assemble onto the particle. The structure of the immature rotavirus virion has not been fully resolved; here we have used that of the trypsin-primed, fully-infectious particle1. Prior to trypsin cleavage, VP4 does not form well-ordered spikes like those depicted here22

The mechanism by which the transient envelope is removed from the DLP is not known. Treatment of infected cells with tunicamycin (which blocks N-glycosylation) or thapsigargin (which disrupts ER calcium storage and chaperone functions) arrests morphogenesis, causing enveloped DLPs to accumulate in the ER lumen90, 91. These data implicate one of the rotavirus ER-resident glycoproteins (NSP4 or VP7) in membrane penetration. Interestingly, although somewhat confounding, both NSP4 and VP7 have been shown to disrupt membranes in vitro92, 93. siRNA knockdown of NSP4 expression results in a pleiotropic phenotype that cannot be directly linked to membrane penetration during assembly94, 95. In contrast, siRNA knockdown of VP7 expression results in the same ‘enveloped DLP’ phenotype observed with drug treatment and strongly suggests a direct role for VP7 in membrane disruption during assembly95.

Virion release from infected cells

In vitro studies indicate that assembled rotavirus virions are capable of egress from infected cells by more than one mechanism. The virus is released from non-polarized kidney epithelium cells virus by direct lysis96. However, as the morphology and function of these cells are very different from the intestinal epithelial cells, lysis may not reflect the primary mechanism of virus release from all cell types in the infected host. Consistent with this, another report indicates that rotavirus is released from a polarized intestinal epithelial cell line by trafficking and secretion from the apical cell surface97. Release from polarized cells appears to utilize a novel secretion pathway that bypasses the Golgi apparatus and lysosomes97. It is not known if the apical targeting of virions is due to ‘hijacking’ of the infected cell by rotavirus (i.e., misappropriation of cellular components to aid in egress, as with the actin tail-based ejection of vaccinia virus98) or if the virus is merely accessing a pre-existing secretory pathway. With growing evidence that rotavirus replicates in other than intestinal epithelial cells in the infected host, the possibility remains that a combination of release mechanisms are involved in virus spread in vivo.

Concluding remarks

Throughout the process of replication, rotavirus appears to have evolved mechanisms to ascertain various states of particle assembly and then function accordingly to drive replication forward. During entry, the virus uses VP7 to sense that it has been endocytosed into a target cell. Subsequent uncoating of VP7 from the DLP cues membrane penetration by VP5* and transcription by the encapsidated PCs. Later, during assembly, an intricate network of interactions among viral RNAs and proteins within the viroplasm coordinate the order of events that culminate with the assembly-associated synthesis of the dsRNA genome. Rotavirus prevents aberrant genome replication by first forming an auto-inhibited complex between the (+)RNA transcripts and the viral polymerase, VP1; genome replication is triggered through subsequent interaction of this complex with the assembling VP2 core shell. Yet, the entirety of how the non-structural proteins NSP2 and NSP5 orchestrate—and likely modulate—virus particle assembly is not known. Newly formed DLPs are recognized by the viral ‘ER receptor’, NSP4, and directed towards outer capsid assembly. Arguably, one of the least understood aspects of rotavirus biology is the process by which the assembling particle penetrates the ER membrane to acquire its outer capsid. The advancement of reverse genetics technology 69, 99 and, possibly, novel complementation systems100 for rotavirus will likely lead to a better understanding of this transient and multifactorial event.

In an interesting parallel with rotavirus, the activity of Hepadnaviridae reverse transcriptase is intimately tied to the assembly of nascent virions. During packaging, the hepatitis B virus reverse transcriptase must first recognize a stem loop structure near the 5’ end of the pre-genomic RNA in order to be sequestered into a core particle101, 102. Only then is the pre-genomic RNA converted into partial dsDNA. Reverse transcription is also required for capsid maturation, leading to subsequent membrane envelopment and egress103. While more broad comparisons among retrovirus, (+)RNA virus, and dsRNA virus replication have been made104, this specific example illustrates the functional convergence of viruses using particle assembly state as a precise metric—and trigger—to ensure correct coordination of replication. Further insights into the minute details of virus particle structures, and assembly intermediates, may provide a greater appreciation of the commonalities that span divergent groups of viruses.

Acknowledgements

We thank Natalie Leach for careful reading of the manuscript. We thank Steve Harrison, Ethan Settembre, and Kristen Ogden for helpful discussions. ST and JP were supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH (Z01 AI000788). SM was supported by the NIAID Intramural Research Program and the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute.

Glossary

- Segmented virus

A virus whose genome comprises multiple, distinct nucleic acid molecules-each segment is analogous to a eukaryotic chromosome, but usually encodes 1–3 proteins

- Icosohedral symmetry

A type of symmetry common to viral capsids-an icosahedrally symmetric object has 30 two-fold, 20 three-fold, and 12 five-fold axes of rotation (cf. icosahedron or dodecahedron)

- Triangulation number (T-number)

References the number of symmetrically distinct subunits that make up each of the asymmetric units of the capsid. Generally, larger virions require higher T-numbers (i.e., more subunits) to form their capsids

- 5-fold vertex

The point on an icosahedron; for the Reoviridae, these are the 12 axes of five-fold symmetry and the sites of plus-sense RNA extrusion

- (RNA) capping enzyme

An enzyme that is responsible for modifying the 5’ end of an RNA to generate a cap structure that is common to that of eukaryotic mRNAs

- Peripentonal channels

For rotavirus, the approximately 6-fold symmetric ‘gaps’ in the VP6 layer that surround each of the 5-fold vertices these are the binding sites for VP4 trimers during assembly

- Serotype

A method of classifying rotaviruses, using comparative neutralization by monoclonal antibodies-for rotavirus, the presence of two outer capsid proteins (VP4 and VP7) results in a binary serotype

- Neutralizing antibodies

Antibodies that block infectivity (e.g., of a virus), usually by binding to the virion and incapacitating it in some way

- Galectin

A family of sugar-binding proteins that have a similar, distinct fold

- Sialic acid (moieties)

A carbohydrate functional group added to proteins or lipids used by several viruses (rotavirus, influenza, etc.) as attachment factors to host cells

- Myristoylation

Modification of the N-terminus of a protein with a covalently linked fatty acid (myristic acid) can impart a hydrophobic character to proteins or target them to a membrane

- Cathepsin

A diverse family of intracellular proteases many members function in the low pH environment of the lysosome

- Plus-strand RNA

The RNA strand that directly encodes the Reoviridae proteins; used as a template to synthesize the minus-strand during dsRNA genome replication

- Minus-strand RNA

The reverse complement of the plus-strand RNA for the Reoviridae, used as a template during transcription to make more plus-strand RNA

- Reverse genetics (systems)

Any method of specifically modifying a viral genome using recombinant technology (cf. forward genetic screen)

References

- 1.Settembre EC, Chen JZ, Dormitzer PR, Grigorieff N, Harrison SC. Atomic model of an infectious rotavirus particle. EMBO J. 2011;30:408–416. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ludert JE, Ruiz MC, Hidalgo C, Liprandi F. Antibodies to rotavirus outer capsid glycoprotein VP7 neutralize infectivity by inhibiting virion decapsidation. J Virol. 2002;76:6643–6651. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.13.6643-6651.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen JZ, et al. Molecular interactions in rotavirus assembly and uncoating seen by high-resolution cryo-EM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:10644–10648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904024106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawton JA, Estes MK, Prasad BV. Three-dimensional visualization of mRNA release from actively transcribing rotavirus particles. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:118–121. doi: 10.1038/nsb0297-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen D, Patton JT. De novo synthesis of minus strand RNA by the rotavirus RNA polymerase in a cell-free system involves a novel mechanism of initiation. RNA. 2000;6:1455–1467. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200001187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald SM, Patton JT. Rotavirus VP2 core shell regions critical for viral polymerase activation. J Virol. 2011;85:3095–3105. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02360-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aoki ST, et al. Structure of rotavirus outer-layer protein VP7 bound with a neutralizing Fab. Science. 2009;324:1444–1447. doi: 10.1126/science.1170481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dormitzer PR, Nason EB, Prasad BV, Harrison SC. Structural rearrangements in the membrane penetration protein of a non-enveloped virus. Nature. 2004;430:1053–1058. doi: 10.1038/nature02836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dormitzer PR, Sun ZY, Wagner G, Harrison SC. The rhesus rotavirus VP4 sialic acid binding domain has a galectin fold with a novel carbohydrate binding site. EMBO J. 2002;21:885–897. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.5.885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lu X, et al. Mechanism for coordinated RNA packaging and genome replication by rotavirus polymerase VP1. Structure. 2008;16:1678–1688. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClain B, Settembre E, Temple BR, Bellamy AR, Harrison SC. X-ray crystal structure of the rotavirus inner capsid particle at 3.8 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2010;397:587–599. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.01.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang X, et al. Near-atomic resolution using electron cryomicroscopy and single-particle reconstruction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1867–1872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711623105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reinisch KM, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. Structure of the reovirus core at 3.6 A resolution. Nature. 2000;404:960–967. doi: 10.1038/35010041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grimes JM, et al. The atomic structure of the bluetongue virus core. Nature. 1998;395:470–478. doi: 10.1038/26694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang X, Walker SB, Chipman PR, Nibert ML, Baker TS. Reovirus polymerase lambda 3 localized by cryo-electron microscopy of virions at a resolution of 7.6 A. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:1011–1018. doi: 10.1038/nsb1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estrozi LF, Navaza J. Ab initio high-resolution single-particle 3D reconstructions: the symmetry adapted functions way. J Struct Biol. 2010;172:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathieu M, et al. Atomic structure of the major capsid protein of rotavirus: implications for the architecture of the virion. EMBO J. 2001;20:1485–1497. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matthijnssens J, et al. Recommendations for the classification of group A rotaviruses using all 11 genomic RNA segments. Arch Virol. 2008;153:1621–1629. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0155-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, et al. Features of reovirus outer capsid protein mu1 revealed by electron cryomicroscopy and image reconstruction of the virion at 7.0 Angstrom resolution. Structure. 2005;13:1545–1557. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liemann S, Chandran K, Baker TS, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. Structure of the reovirus membrane-penetration protein, Mu1, in a complex with is protector protein, Sigma3. Cell. 2002;108:283–295. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00612-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Estes MK, Graham DY, Mason BB. Proteolytic enhancement of rotavirus infectivity: molecular mechanisms. J Virol. 1981;39:879–888. doi: 10.1128/jvi.39.3.879-888.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crawford SE, et al. Trypsin cleavage stabilizes the rotavirus VP4 spike. J Virol. 2001;75:6052–6061. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.6052-6061.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yeager M, Berriman JA, Baker TS, Bellamy AR. Three-dimensional structure of the rotavirus haemagglutinin VP4 by cryo-electron microscopy and difference map analysis. EMBO J. 1994;13:1011–1018. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Z, Baker ML, Jiang W, Estes MK, Prasad BV. Rotavirus architecture at subnanometer resolution. J Virol. 2009;83:1754–1766. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01855-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaw AL, et al. Three-dimensional visualization of the rotavirus hemagglutinin structure. Cell. 1993;74:693–701. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90516-S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fiore L, Greenberg HB, Mackow ER. The VP8 fragment of VP4 is the rhesus rotavirus hemagglutinin. Virology. 1991;181:553–563. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90888-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruggeri FM, Greenberg HB. Antibodies to the trypsin cleavage peptide VP8 neutralize rotavirus by inhibiting binding of virions to target cells in culture. J Virol. 1991;65:2211–2219. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.5.2211-2219.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monnier N, et al. High-resolution molecular and antigen structure of the VP8* core of a sialic acid-independent human rotavirus strain. J Virol. 2006;80:1513–1523. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1513-1523.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dormitzer PR, et al. Specificity and affinity of sialic acid binding by the rhesus rotavirus VP8* core. J Virol. 2002;76:10512–10517. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10512-10517.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanchard H, Yu X, Coulson BS, von Itzstein M. Insight into host cell carbohydrate-recognition by human and porcine rotavirus from crystal structures of the virion spike associated carbohydrate-binding domain (VP8*) J Mol Biol. 2007;367:1215–1226. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mendez E, Arias CF, Lopez S. Binding to sialic acids is not an essential step for the entry of animal rotaviruses to epithelial cells in culture. J Virol. 1993;67:5253–5259. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5253-5259.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ciarlet M, Estes MK. Human and most animal rotavirus strains do not require the presence of sialic acid on the cell surface for efficient infectivity. J Gen Virol. 1999;80(Pt 4):943–948. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-4-943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim IS, Trask SD, Babyonyshev M, Dormitzer PR, Harrison SC. Effect of mutations in VP5 hydrophobic loops on rotavirus cell entry. J Virol. 2010;84:6200–6207. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02461-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tihova M, Dryden KA, Bellamy AR, Greenberg HB, Yeager M. Localization of membrane permeabilization and receptor binding sites on the VP4 hemagglutinin of rotavirus: implications for cell entry. J Mol Biol. 2001;314:985–992. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.5238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dormitzer PR, Greenberg HB, Harrison SC. Proteolysis of monomeric recombinant rotavirus VP4 yields an oligomeric VP5* core. J Virol. 2001;75:7339–7350. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.16.7339-7350.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrison SC. Viral membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:690–698. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wolf M, Vo PT, Greenberg HB. Rhesus rotavirus entry into a polarized epithelium is endocytosis dependent and involves sequential VP4 conformational changes. J Virol. 2011;85:2492–2503. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02082-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trask SD, Kim IS, Harrison SC, Dormitzer PR. A rotavirus spike protein conformational intermediate binds lipid bilayers. J Virol. 2010;84:1764–1770. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01682-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Agosto MA, Ivanovic T, Nibert ML. Mammalian reovirus, a nonfusogenic nonenveloped virus, forms size-selective pores in a model membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16496–16501. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605835103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang L, et al. Requirements for the formation of membrane pores by the reovirus myristoylated micro1N peptide. J Virol. 2009;83:7004–7014. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00377-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arias CF, Romero P, Alvarez V, Lopez S. Trypsin activation pathway of rotavirus infectivity. J Virol. 1996;70:5832–5839. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.9.5832-5839.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chemello ME, Aristimuno OC, Michelangeli F, Ruiz MC. Requirement for vacuolar H+ -ATPase activity and Ca2+ gradient during entry of rotavirus into MA104 cells. J Virol. 2002;76:13083–13087. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.13083-13087.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ludert JE, Michelangeli F, Gil F, Liprandi F, Esparza J. Penetration and uncoating of rotaviruses in cultured cells. Intervirology. 1987;27:95–101. doi: 10.1159/000149726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yoder JD, et al. VP5* rearranges when rotavirus uncoats. J Virol. 2009;83:11372–11377. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01228-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ebert DH, Deussing J, Peters C, Dermody TS. Cathepsin L and cathepsin B mediate reovirus disassembly in murine fibroblast cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:24609–24617. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201107200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Golden JW, Bahe JA, Lucas WT, Nibert ML, Schiff LA. Cathepsin S supports acid-independent infection by some reoviruses. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:8547–8557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309758200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lawton JA, Estes MK, Prasad BV. Mechanism of genome transcription in segmented dsRNA viruses. Adv Virus Res. 2000;55:185–229. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(00)55004-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tao Y, Farsetta DL, Nibert ML, Harrison SC. RNA synthesis in a cage--structural studies of reovirus polymerase lambda3. Cell. 2002;111:733–745. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen D, Luongo CL, Nibert ML, Patton JT. Rotavirus open cores catalyze 5'-capping and methylation of exogenous RNA: evidence that VP3 is a methyltransferase. Virology. 1999;265:120–130. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sutton G, Grimes JM, Stuart DI, Roy P. Bluetongue virus VP4 is an RNA-capping assembly line. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:449–451. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim J, Parker JS, Murray KE, Nibert ML. Nucleoside and RNA triphosphatase activities of orthoreovirus transcriptase cofactor mu2. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:4394–4403. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308637200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng L, et al. Atomic model of a cypovirus built from cryo-EM structure provides insight into the mechanism of mRNA capping. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1373–1378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014995108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mendez II, Weiner SG, She YM, Yeager M, Coombs KM. Conformational changes accompany activation of reovirus RNA-dependent RNA transcription. J Struct Biol. 2008;162:277–289. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Libersou S, et al. Geometric mismatches within the concentric layers of rotavirus particles: a potential regulatory switch of viral particle transcription activity. J Virol. 2008;82:2844–2852. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02268-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thouvenin E, et al. Antibody inhibition of the transcriptase activity of the rotavirus DLP: a structural view. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:161–172. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feng N, et al. Inhibition of rotavirus replication by a non-neutralizing, rotavirus VP6-specific IgA mAb. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1203–1213. doi: 10.1172/JCI14397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mansell EA, Patton JT. Rotavirus RNA replication: VP2, but not VP6, is necessary for viral replicase activity. J Virol. 1990;64:4988–4996. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.4988-4996.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patton JT. Rotavirus VP1 alone specifically binds to the 3' end of viral mRNA, but the interaction is not sufficient to initiate minus-strand synthesis. J Virol. 1996;70:7940–7947. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.7940-7947.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Patton JT, Jones MT, Kalbach AN, He YW, Xiaobo J. Rotavirus RNA polymerase requires the core shell protein to synthesize the double-stranded RNA genome. J Virol. 1997;71:9618–9626. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9618-9626.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McDonald SM, Patton JT. Molecular characterization of a subgroup specificity associated with the rotavirus inner capsid protein VP2. J Virol. 2008;82:2752–2764. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02492-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Silvestri LS, Taraporewala ZF, Patton JT. Rotavirus replication: plus-sense templates for double-stranded RNA synthesis are made in viroplasms. J Virol. 2004;78:7763–7774. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.14.7763-7774.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jayaram H, Taraporewala Z, Patton JT, Prasad BV. Rotavirus protein involved in genome replication and packaging exhibits a HIT-like fold. Nature. 2002;417:311–315. doi: 10.1038/417311a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jiang X, et al. Cryoelectron microscopy structures of rotavirus NSP2-NSP5 and NSP2-RNA complexes: implications for genome replication. J Virol. 2006;80:10829–10835. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01347-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martin D, Ouldali M, Menetrey J, Poncet D. Structural Organisation of the Rotavirus Nonstructural Protein NSP5. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chnaiderman J, Barro M, Spencer E. NSP5 phosphorylation regulates the fate of viral mRNA in rotavirus infected cells. Arch Virol. 2002;147:1899–1911. doi: 10.1007/s00705-002-0856-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ogden KM, Ramanathan HN, Patton JT. Residues of the rotavirus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase template entry tunnel that mediate RNA recognition and genome replication. J Virol. 2011;85:1958–1969. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01689-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Noda T, et al. Architecture of ribonucleoprotein complexes in influenza A virus particles. Nature. 2006;439:490–492. doi: 10.1038/nature04378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gao Q, Palese P. Rewiring the RNAs of influenza virus to prevent reassortment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:15891–15896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908897106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kobayashi T, et al. A plasmid-based reverse genetics system for animal double-stranded RNA viruses. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:147–157. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roner MR, Joklik WK. Reovirus reverse genetics: Incorporation of the CAT gene into the reovirus genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:8036–8041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131203198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li W, et al. Genomic analysis of codon, sequence and structural conservation with selective biochemical-structure mapping reveals highly conserved and dynamic structures in rotavirus RNAs with potential cis-acting functions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:7718–7735. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Patton JT, Wentz M, Xiaobo J, Ramig RF. cis-Acting signals that promote genome replication in rotavirus mRNA. J Virol. 1996;70:3961–3971. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3961-3971.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lepault J, et al. Structural polymorphism of the major capsid protein of rotavirus. EMBO J. 2001;20:1498–1507. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.7.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zeng CQ, et al. Characterization of rotavirus VP2 particles. Virology. 1994;201:55–65. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Berois M, Sapin C, Erk I, Poncet D, Cohen J. Rotavirus nonstructural protein NSP5 interacts with major core protein VP2. J Virol. 2003;77:1757–1763. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.3.1757-1763.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kattoura MD, Chen X, Patton JT. The rotavirus RNA-binding protein NS35 (NSP2) forms 10S multimers and interacts with the viral RNA polymerase. Virology. 1994;202:803–813. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vende P, Tortorici MA, Taraporewala ZF, Patton JT. Rotavirus NSP2 interferes with the core lattice protein VP2 in initiation of minus-strand synthesis. Virology. 2003;313:261–273. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bergmann CC, Maass D, Poruchynsky MS, Atkinson PH, Bellamy AR. Topology of the non-structural rotavirus receptor glycoprotein NS28 in the rough endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 1989;8:1695–1703. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bowman GD, et al. Crystal structure of the oligomerization domain of NSP4 from rotavirus reveals a core metal-binding site. J Mol Biol. 2000;304:861–871. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.O'Brien JA, Taylor JA, Bellamy AR. Probing the structure of rotavirus NSP4: a short sequence at the extreme C terminus mediates binding to the inner capsid particle. J Virol. 2000;74:5388–5394. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.11.5388-5394.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Taylor JA, O'Brien JA, Yeager M. The cytoplasmic tail of NSP4, the endoplasmic reticulum-localized non-structural glycoprotein of rotavirus, contains distinct virus binding and coiled coil domains. EMBO J. 1996;15:4469–4476. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Taylor JA, O'Brien JA, Lord VJ, Meyer JC, Bellamy AR. The RER-localized rotavirus intracellular receptor: a truncated purified soluble form is multivalent and binds virus particles. Virology. 1993;194:807–814. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Au KS, Mattion NM, Estes MK. A subviral particle binding domain on the rotavirus nonstructural glycoprotein NS28. Virology. 1993;194:665–673. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Trask SD, Dormitzer PR. Assembly of highly infectious rotavirus particles recoated with recombinant outer capsid proteins. J Virol. 2006;80:11293–11304. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01346-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Poruchynsky MS, Atkinson PH. Rotavirus protein rearrangements in purified membrane-enveloped intermediate particles. J Virol. 1991;65:4720–4727. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4720-4727.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Maass DR, Atkinson PH. Rotavirus proteins VP7, NS28, and VP4 form oligomeric structures. J Virol. 1990;64:2632–2641. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.6.2632-2641.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stirzaker SC, Both GW. The signal peptide of the rotavirus glycoprotein VP7 is essential for its retention in the ER as an integral membrane protein. Cell. 1989;56:741–747. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90677-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Petrie BL, Greenberg HB, Graham DY, Estes MK. Ultrastructural localization of rotavirus antigens using colloidal gold. Virus Res. 1984;1:133–152. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(84)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gonzalez RA, Espinosa R, Romero P, Lopez S, Arias CF. Relative localization of viroplasmic and endoplasmic reticulum-resident rotavirus proteins in infected cells. Arch Virol. 2000;145:1963–1973. doi: 10.1007/s007050070069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Poruchynsky MS, Maass DR, Atkinson PH. Calcium depletion blocks the maturation of rotavirus by altering the oligomerization of virus-encoded proteins in the ER. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:651–656. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Michelangeli F, Liprandi F, Chemello ME, Ciarlet M, Ruiz MC. Selective depletion of stored calcium by thapsigargin blocks rotavirus maturation but not the cytopathic effect. J Virol. 1995;69:3838–3847. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3838-3847.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Browne EP, Bellamy AR, Taylor JA. Membrane-destabilizing activity of rotavirus NSP4 is mediated by a membrane-proximal amphipathic domain. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:1955–1959. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-8-1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Charpilienne A, et al. Solubilized and cleaved VP7, the outer glycoprotein of rotavirus, induces permeabilization of cell membrane vesicles. J Gen Virol. 1997;78(Pt 6):1367–1371. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-6-1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Silvestri LS, Tortorici MA, Vasquez-Del Carpio R, Patton JT. Rotavirus glycoprotein NSP4 is a modulator of viral transcription in the infected cell. J Virol. 2005;79:15165–15174. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15165-15174.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lopez T, et al. Silencing the morphogenesis of rotavirus. J Virol. 2005;79:184–192. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.184-192.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Musalem C, Espejo RT. Release of progeny virus from cells infected with simian rotavirus SA11. Gen Virol. 1985;66(Pt 12):2715–2724. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-66-12-2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jourdan N, et al. Rotavirus is released from the apical surface of cultured human intestinal cells through nonconventional vesicular transport that bypasses the Golgi apparatus. J Virol. 1997;71:8268–8278. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8268-8278.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cudmore S, Cossart P, Griffiths G, Way M. Actin-based motility of vaccinia virus. Nature. 1995;378:636–638. doi: 10.1038/378636a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Boyce M, Celma CC, Roy P. Development of reverse genetics systems for bluetongue virus: recovery of infectious virus from synthetic RNA transcripts. J Virol. 2008;82:8339–8348. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00808-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Taraporewala ZF, et al. Structure-function analysis of rotavirus NSP2 octamer by using a novel complementation system. J Virol. 2006;80:7984–7994. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00172-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Knaus T, Nassal M. The encapsidation signal on the hepatitis B virus RNA pregenome forms a stem-loop structure that is critical for its function. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3967–3975. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.17.3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Porterfield JZ, et al. Full-length hepatitis B virus core protein packages viral and heterologous RNA with similarly high levels of cooperativity. J Virol. 2010;84:7174–7184. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00586-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Perlman DH, Berg EA, O’Connor PB, Costello CE, Hu J. Reverse transcription-associated dephosphorylation of hepadnavirus nucleocapsids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9020–9025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502138102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ahlquist P. Parallels among positive-strand RNA viruses, reverse-transcribing viruses and double-stranded RNA viruses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4:371–382. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]