Abstract

Objective

To provide recommendations on screening for hypertension in adults aged 18 years and older without previously diagnosed hypertension.

Quality of evidence

Evidence was found through a systematic search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (EBM Reviews), from January 1985 to September 2011. Study types were limited to randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and observational studies with control groups.

Main message

Three strong recommendations were made based on moderate-quality evidence. It is recommended that blood pressure measurement occur at all appropriate primary care visits, according to the current techniques described in the Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for office and ambulatory blood pressure measurement. The Canadian Hypertension Education Program criteria for assessment and diagnosis of hypertension should be applied for people found to have elevated blood pressure.

Conclusion

After review of the most recent evidence, the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care continues to recommend blood pressure measurement during regular physician visits.

Approximately 4.6 million Canadians aged 20 years and older (19% of the population) have high blood pressure,1 which is a risk factor for stroke, myocardial infarction, and other diseases. A further 20% have high-normal blood pressure levels, defined as systolic blood pressure between 120 and 139 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure between 80 and 89 mm Hg (the term prehypertension is also used to refer to this group).1 The prevalence of hypertension is similar in men and women, although the prevalence of high-normal blood pressure (prehypertension) is greater in men.1 Obesity is one of the most important risk factors for hypertension2 and even high-normal blood pressure increases risk of cardiovascular disease.3 While the prevalence of hypertension has remained stable over the past several years, rates of awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension have improved.4 In the early 1990s only 57% of Canadians were aware of their hypertensive status, but in 2009 that number increased to 83%. In the same period, the percentage of Canadians who had their hypertension under control rose from 13% to 65%.4

The Canadian Hypertension Education Program (CHEP) recommends that all health care professionals “who have been specifically trained to measure blood pressure ... accurately should assess [blood pressure] in all adult patients at all appropriate visits to determine cardiovascular risk and monitor antihypertensive treatment,”5 although no definitive screening interval is specified. Those with high-normal blood pressure should be reassessed annually.6 Evidence regarding the benefit of treatment forms the basis of this recommendation, but no specific evidence about the benefits of screening is cited.

Previous Canadian7–9 and US reviews10,11 have focused on the indirect evidence for benefit from treatment and none have summarized the direct effects of hypertension screening on reducing blood pressure or cardiovascular outcomes. We sought to determine if there was any direct evidence of the effectiveness of hypertension screening using office and out-of-office blood pressure measurement in adults. Home blood pressure measurement in this context is not considered a primary screening test; however, it could be used as an adjunct in the diagnostic process. For this hypertension screening guideline, cardiovascular disease and morbidity includes stroke, heart disease, renal disease, peripheral vascular disease, and retinal disease.

The objective of these guidelines is to provide recommendations on screening for hypertension for adults aged 18 years and older without previously diagnosed hypertension. Recommendations apply to the general population including adults with average baseline blood pressure and those at higher than average risk of hypertension and vascular disease. This document updates previous guidelines by the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care (CTFPHC), which were last reviewed in 1994.8

With respect to guidelines on the most appropriate methods for measuring blood pressure and for diagnosing hypertension, the CTFPHC defers to current guidance from CHEP to avoid duplication of effort. The CHEP recommendations have undergone critical appraisal by the CTFPHC to assess the quality of the guideline development process and have met our criteria for rigorously developed guidelines.

Quality of evidence

The development of these recommendations was led by a CTFPHC working group, in collaboration with CHEP and the Public Health Agency of Canada. Only members of the CTFPHC were involved in the final voting for these recommendations.

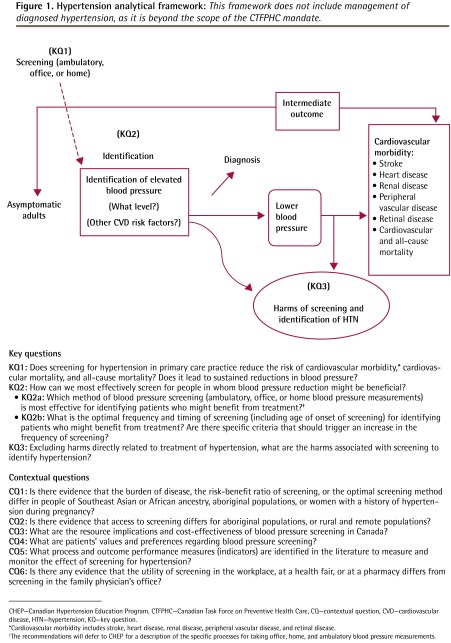

The working group established the research questions (Detailed Methods)* and analytical framework (Figure 1) for the guideline. Evidence was found through a systematic search of 3 electronic databases—MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (EBM Reviews)—restricted to English- and French-language articles published from January 1985 to September 2011. A total of 13 283 citations were retrieved and screened, with 205 publications meeting the inclusion criteria for full-text review. Study types were limited to randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and observational studies with control groups. Modeling studies were also examined to address key question 1 (Figure 1). The systematic review that supports these guidelines is published on the CTFPHC website.12 Detailed information about CTFPHC methods has been published elsewhere,13 and specific information related to these guidelines is available from CFPlus.*

Figure 1.

Hypertension analytical framework: This framework does not include management of diagnosed hypertension, as it is beyond the scope of the CTFPHC mandate.

CHEP—Canadian Hypertension Education Program, CTFPHC—Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, CQ—contextual question, CVD—cardiovascular disease, HTN—hypertension, KQ—key question.

*Cardiovascular morbidity includes stroke, heart disease, renal disease, peripheral vascular disease, and retinal disease.

†The recommendations will defer to CHEP for a description of the specific processes for taking office, home, and ambulatory blood pressure measurements.

The CHEP recommendations were assessed based on the CTFPHC’s critical appraisal process,* which is designed to review and critically appraise the guideline development process from other organizations.

Main message

A systematic review was conducted to examine the effectiveness of hypertension screening in primary care in reducing the risk of important patient outcomes of cardiovascular morbidity, and cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. The effectiveness of screening on reducing blood pressure (an intermediate outcome) and an examination of the harms of screening were also included. Critical appraisal of CHEP’s recommendations on methods for hypertension screening was conducted by the CTFPHC.

Recommendations for adults aged 18 years and older without previously diagnosed hypertension

1. We recommend blood pressure measurement at all appropriate primary care visits: “Appropriate” visits might include periodic health examinations, urgent office visits for neurologic or cardiovascular-related issues, medication renewal visits, and other visits where the primary care practitioner deems it an appropriate opportunity to monitor blood pressure. It is not necessary to measure the blood pressure of every patient at every office visit.

The frequency and timing of blood pressure screening might vary among patients. The risk of high blood pressure and the risk of stroke or heart disease change over a person’s natural lifespan and increase with age, comorbidities, and the presence of other risk factors. Therefore, screening frequency might increase accordingly, especially in patients with more than 1 vascular risk factor. Adults identified as belonging to a high-risk ethnic group (Southeast Asian, aboriginal, or African ancestry) might benefit from more frequent monitoring. Having recent consistently normal blood pressure measurements might decrease the need for more frequent monitoring, while a tendency toward high-normal blood pressure could indicate that more frequent monitoring is needed.

This is a strong recommendation, with moderate-quality evidence (Box 1).14 The evidence rating is based on a substantial body of indirect evidence and moderate-quality evidence from 1 randomized controlled trial.15

Box 1. Grading of recommendations.

Recommendations are graded according to the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system,14 which offers 2 strengths of recommendation: strong and weak. The strength of recommendations is based on the quality of supporting evidence; degree of uncertainty about the balance between desirable and undesirable effects; degree of uncertainty or variability in values and preferences; and degree of uncertainty about whether the intervention represents a wise use of resources.

Strong recommendations are those for which the task force is confident that the desirable effects of an intervention outweigh its undesirable effects (strong recommendation for an intervention) or that the undesirable effects of an intervention outweigh its desirable effects (strong recommendation against an intervention). A strong recommendation implies that most individuals will be best served by the recommended course of action.

Weak recommendations are those for which the desirable effects probably outweigh the undesirable effects (weak recommendation for an intervention) or undesirable effects probably outweigh the desirable effects (weak recommendation against an intervention) but appreciable uncertainty exists. A weak recommendation implies that most people would want the recommended course of action but that many would not. For clinicians this means they must recognize that different choices will be appropriate for each individual, and they must help each person arrive at a management decision consistent with his or her values and preferences. Policy making will require substantial debate and involvement of various stakeholders. Weak recommendations result when the balance between desirable and undesirable effects is small, the quality of evidence is lower, or there is more variability in the values and preferences of patients.

Evidence is graded as high, moderate, low, or very low, based on how likely further research is to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

This recommendation is in part based on direct evidence from a randomized controlled trial that showed a community-based screening program that included a comprehensive cardiovascular risk assessment and education session reduced cardiovascular mortality, compared with usual practice (Table 1).15 After adjustment for hospital admission rates during the year before intervention, intervention communities had 3 fewer annual hospital admissions for cardiovascular disease per 1000 people 65 years of age and older compared with control communities. The risk of admission was reduced for myocardial infarction (relative risk [RR] 0.87, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.97, P = .008) and congestive heart failure (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.99, P = .029), with non-significant trends toward decreases in stroke and cardiovascular mortality. Residents in the intervention communities were also more likely to start antihypertensive therapy (RR 1.10, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.20, P = .02) than those in the control communities who underwent usual screening practices.

Table 1.

Evidence summary of benefits associated with hypertension screening: The mean follow-up was 1 y. Each end point was assessed using mean cumulative hospital rates from 1 RCT.15 There was no serious risk of bias in this trial. There are no concerns about lack of blinding, as blinding is part of the intervention and therefore there is no risk of bias. There was no serious inconsistency, as only a single study was used (inconsistency is not applicable). There was serious indirectness, as the study focused on the population > 65 y of age (although younger patients were not denied participation); therefore, the study results are not generalizable to the general population. In addition to hypertension screening, the intervention included comprehensive cardiovascular risk assessment and education sessions. The efficacy of hypertension screening in isolation was not directly assessed. There was no serious imprecision seen in the trial. There was an insufficient number of studies to assess publication bias. The study was of moderate quality and critical importance.

| END POINT |

PATIENTS, N (%)

|

EFFECT RELATIVE (95% CI)* | ABSOLUTE NO. PER 1 000 000 (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KQ1 SCREENING (N = 69 942) | CONTROL, NO SCREENING (N = 75 499) | |||

| Composite | 1951 (2.8)† | 2275 (3.0)† | RR 0.91 (0.86 to 0.97) | 2712 fewer (904 fewer to 4219 fewer) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 667 (1.0)† | 816 (1.1)† | RR 0.87 (0.79 to 0.97) | 1405 fewer (324 fewer to 2270 fewer) |

| Congestive heart failure | 735 (1.1)† | 923 (1.2)† | RR 0.90 (0.81 to 0.99) | 1223 fewer (122 fewer to 2323 fewer) |

| Stroke | 550 (0.8)† | 536 (0.7)† | RR 0.99 (0.88 to 1.12) | 71 fewer (852 fewer to 852 more) |

| All-cause mortality | 2377 (3.4)‡ | 2608 (3.5)‡ | RR 0.98 (0.92 to 1.04) | 684 fewer (2618 fewer to 1368 more) |

KQ1—key question 1, RCT—randomized controlled trial, RR—relative risk.

These outcomes represent the effect of the Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program. Outcome measures reported have been adjusted for hospital admission rates in the year before the intervention.

Calculations based on mean cumulative admissions.

Calculations based on the number of unique admissions.

Data from Kaczorowski et al.15

This recommendation is also based on the substantial body of indirect evidence that demonstrates the benefits of treating diagnosed hypertension, whether mild or severe.16–18 One meta-analysis on the effectiveness of treatment of hypertension (which included 147 studies) found that lowering blood pressure by 10/5 mm Hg (the equivalent of taking 1 drug at a standard dose) could prevent 22% of coronary artery disease events and 41% of strokes in those aged 60 to 69 years.19 Previous guidance20,21 also used indirect evidence demonstrating that hypertension can be effectively diagnosed through office blood pressure measurements11 and that treatment of elevated blood pressure can decrease cardiovascular events11,20 as the basis for their recommendations.

The working group identified and searched for literature on the following clinically important harms associated with screening: false positives, false negatives, anxiety, psychological effects, and economic costs such as lost time from work or lost insurance. We found no evidence to indicate that any of these clinically relevant harms result from hypertension screening,12 although we do acknowledge that no evidence of harm does not ensure that there is no harm. Recent evidence suggests that although pharmacologic therapy for early hypertension has common side effects, serious adverse effects are rare.10 An examination of the harms of treatment of hypertension was outside the scope of our review. Although we did not identify studies of patients’ values and preferences about screening for hypertension, in the judgment of the CTFPHC, blood pressure screening is an acceptable preventive intervention for Canadian patients. Experience from the Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program,15 which had no problems recruiting volunteers, also suggests that this type of screening is acceptable to the general public.

Screening interval

We found no evidence to support a particular screening interval, although checking a patient’s blood pressure during almost any health care encounter has become a part of common clinical practice for patients who might be considered at higher risk of hypertension based on age and existing comorbidities. Given the potential value of detecting hypertension, the lack of evidence for substantial harms associated with screening, and the noninvasive nature of blood pressure measurement, the CTFPHC supports assessing blood pressure at all appropriate visits—and that Canadians with high-normal blood pressure should have their blood pressure assessed at least annually. These recommendations are consistent with those from CHEP.6

Recommendations on methods for hypertension screening

2. We recommend that blood pressure be measured according to the current techniques described in the CHEP recommendations for office and out-of-office blood pressure measurement5: The 2012 CHEP recommendations for office and ambulatory blood pressure measurement were critically appraised by the CTFPHC to assess the quality of the guideline development process, and were found to meet the CTFPHC criteria for rigorously developed guidelines (see Critical Appraisal Results for details).*

This is a strong recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence. Recommendations from CHEP were assessed with AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation)22 criteria and not with the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation)23 criteria. The quality of evidence was determined based on the CTFPHC’s confidence in their estimates and the rigour of their guideline development process.

3. For people who are found to have an elevated blood pressure measurement during screening, the CHEP criteria for assessment and diagnosis of hypertension should be applied to determine whether the patients meet diagnostic criteria for hypertension6: The 2012 CHEP recommendations for assessment and diagnosis of high blood pressure were critically appraised by the CTFPHC to assess the quality of the guideline development process, and were found to meet the CTFPHC criteria for rigorously developed guidelines (see Critical Appraisal Results for details).* This is a strong recommendation based on moderate-quality evidence. Recommendations from CHEP were assessed with AGREE II22 criteria and not with the GRADE23 criteria. The quality of evidence was determined based on the CTFPHC’s confidence in their estimates and the rigour of their guideline development process.

Considerations for implementation of recommendations

Although no evidence was found to indicate that screening practices should differ according to patients’ risk profiles, hypertension appears to be more common in certain population subgroups. The prevalence of hypertension and cardiovascular disease increases as people age, and has been found to be higher in those of Southeast Asian and African ancestry,24,25 and in aboriginal populations, who also have a higher prevalence of associated comorbidities.26,27 Clinical experience suggests that access to preventive health care is also reduced in aboriginal populations28 and in remote and rural areas.12 Hypertension is also common in pregnancy.28 Therefore, these populations might benefit from more frequent monitoring. Screening methods for populations in which English is not a first language could be optimized by using different knowledge translation tools to present information about hypertension screening in culturally appropriate and relevant ways. For instance, adapting pamphlets to accommodate differing literacy skills in Canadians of Indo-Asian descent improved users’ understanding of hypertension over the original English versions.29,30

Practitioners should remain alert for opportunities to screen those who infrequently attend their practices and others who have not been screened recently. These patients are often younger, appear healthy, and might not have risk factors for hypertension or cardiovascular disease and therefore might be overlooked for screening opportunities.

Suggested performance measures for implementation

A key objective of the CTFPHC is to support the uptake of our guidelines into clinical practice and to facilitate quality improvement. To achieve this goal, an important step in our guideline development process is the identification and selection of a small set of standardized key quality indicators. These quality indicators are directly linked to the recommendations contained in this guideline, and are designed and intended for individual practitioners to monitor their compliance and performance for hypertension screening. They will also enable groups of physicians to conduct comparisons for the sake of improvement and benchmarking (Table 2).31

Table 2.

Suggested performance measures for the implementation of the recommendations on screening for high BP in adult Canadians

| PERFORMANCE INDICATOR | INCLUSION | TECHNICAL NOTES |

|---|---|---|

| The proportion of patients aged 18 y and older in a primary care practice who have at least 1 documented BP measurement in the past 24 mo | Include

Exclude

|

|

| The proportion of patients aged 18 y and older with elevated BP on screening who have documentation of further assessment to determine whether the patient meets diagnostic criteria for hypertension as defined in the most current CHEP recommendations for assessment and diagnosis of hypertension | Include

Exclude

|

|

| The proportion of the population with a new diagnosis of hypertension in the past 24 mo | Include

|

|

BP—blood pressure, CHEP—Canadian Hypertension Education Program, DBP—diastolic blood pressure, SBP—systolic blood pressure.

Differences from previous guidelines

There are no differences from previous CTFPHC guidelines. Since 1984 the CTFPHC has recommended blood pressure measurement during regular physician visits. This recommendation is reaffirmed with the current guidelines, which in turn are consistent with recommendations from CHEP and the US Preventive Services Task Force (Table 3).5,7–9,17,21

Table 3.

Comparison of national and international hypertension screening guidelines

| ORGANIZATION | AGE | RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|---|

| Current CTFPHC | 18 y and older | BP screening at all appropriate primary care visits |

| CTFPHC 19948 | Adults and older adults | BP screening included in periodic health examination |

| CTFPHC 19847 | 25 y and over | BP measurement during any physician visit |

| CHEP 20115 | All adults | BP measurement at all appropriate physician visits |

| USPSTF 200721 | 18 y and older | Screen for BP every 1–2 y* |

| Canadian Stroke Network 20109 | All adults | All patients at risk of stroke should have their BP measured routinely, ideally at each health care encounter, but no less than once annually |

BP—blood pressure, CHEP—Canadian Hypertension Education Program, CTFPHC—Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, DBP—diastolic blood pressure, SBP—systolic blood pressure, USPSTF—US Preventive Services Task Force.

The interval comes from the 2000 sixth report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure,17 which recommends screening every 2 y with BP < 120/80 mm Hg and screening every year with SBP of 120–139 mm Hg or DBP of 80–90 mm Hg.

Conclusion

Limited evidence exists to demonstrate that screening for high blood pressure leads to improved cardiovascular and other health outcomes. However, substantial indirect evidence exists to demonstrate that measurement of blood pressure can identify adults at increased risk of cardiovascular disease, that diagnosis of hypertension leads to treatment, and that treatment in turn leads to improved outcomes. Awareness of hypertension status is high in Canada, which is probably because blood pressure screening has become a routine medical practice in recent years. Further research should focus on reaching populations who have less access to health care and as such are less likely to be aware of their hypertension or to have it appropriately controlled.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Blood pressure measurement is recommended at all appropriate primary care visits. “Appropriate” visits might include periodic health examinations, urgent office visits for neurologic or cardiovascular-related issues, medication renewal visits, and other visits where the primary care practitioner deems it an appropriate opportunity to monitor blood pressure. It is not necessary to measure the blood pressure of every patient at every office visit.

Blood pressure should be measured according to the current techniques described in the Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for office and ambulatory blood pressure measurement.

For people who are found to have elevated blood pressure during screening, the Canadian Hypertension Education Program criteria for assessment and diagnosis of hypertension should be applied to determine whether patients meet diagnostic criteria for hypertension.

Footnotes

This article is eligible for Mainpro-M1 credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro link.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro de septembre 2013 à la page e393.

The Decision Table to Inform Hypertension Screening Recommendations, Critical Appraisal Results, and Detailed Methods are available at www.cfp.ca. Go to the full text of the article online, then click on CFPlus in the menu at the top right-hand side of the page.

Contributors

All authors contributed to the literature review and interpretation, and to preparing the manuscript for submission.

Competing interests

None declared

References

- 1.Wilkins K, Campbell NR, Joffres MR, McAlister FA, Nichol M, Quach S, et al. Blood pressure in Canadian adults. Health Rep. 2010;21(1):37–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narkiewicz K. Obesity and hypertension—the issue is more complex than we thought. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21(2):264–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi290. Epub 2005 Nov 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vasan RS, Larson MG, Leip EP, Evans JC, O’Donnell CJ, Kannel WB, et al. Impact of high-normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(18):1291–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McAlister FA, Wilkins K, Joffres M, Leenen FH, Fodor G, Gee M, et al. Changes in the rates of awareness, treatment and control of hypertension in Canada over the past two decades. CMAJ. 2011;183(9):1007–13. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.101767. Epub 2011 May 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canadian Hypertension Education Program [website] Accurate measurement of blood pressure. Markham, ON: Hypertension Canada; 2011. Available from: www.hypertension.ca/accurate-measurement-of-blood-pressure. Accessed 2012 Mar 9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Canadian Hypertension Education Program . 2012 CHEP recommendations for management of hypertension. Markham, ON: Hypertension Canada; 2012. Available from: www.hypertension.ca/images/stories/dls/2012gl/2012CompleteCHEPRecommendationsEN.pdf. Accessed 2012 Mar 9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.The periodic health examination: 2. 1984 update. Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination. CMAJ. 1984;130(10):1278–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Logan AG. Screening for hypertension in young and middle-aged adults. Edmonton, AB: Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care; 1994. Available from: http://canadiantaskforce.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Chapter53_hypertension_adult94.pdf. Accessed 2012 Mar 9. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindsay MP, Gubitz G, Bayley M, Phillips S, editors. Canadian best practice recommendations for stroke care. 4th ed. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Stroke Network; 2012. Available from: www.strokebestpractices.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/20120BPR_Ch2_Prevention_Final-Version_20Sept-2012F-12.pdf. Accessed 2013 Aug 12. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolff T, Miller T. Evidence for the reaffirmation of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation on screening for high blood pressure. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(11):787–91. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-11-200712040-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sheridan S, Pignone M, Donahue K. Screening for high blood pressure: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25(2):151–8. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine M, Neary J, Hammill A, Gauld M, Rice M, Haq M. Screening for hypertension. McMaster Evidence, Review, and Synthesis Centre; 2012. Available from: http://canadiantaskforce.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/HTN-Screening-EvidenceReview-Final.pdf. Accessed 2013 Jul 25. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connor Gorber S, Singh H, Pottie K, Jaramillo A, Tonelli M. Process for guideline development by the reconstituted Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. CMAJ. 2012;184(14):1575–81. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.120642. Epub 2012 Aug 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaczorowski J, Chambers LW, Dolovich L, Paterson JM, Karwalajtys T, Gierman T, et al. Improving cardiovascular health at population level: 39 community cluster randomised trial of Cardiovascular Health Awareness Program (CHAP) BMJ. 2011;342:d442. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National High Blood Pressure Education Program . The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Bethesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2004. NIH publication 04-5230. Available from: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/jnc7full.pdf. Accessed 2013 Jul 18. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ogden LG, He J, Lydick E, Whelton PK. Long-term absolute benefit of lowering blood pressure in hypertensive patients according to the JNC VI risk stratification. Hypertension. 2000;35(2):539–43. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.2.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neal B, MacMahon S, Chapman N, Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration Effects of ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and other blood-pressure-lowering drugs: results of prospectively designed overviews of randomised trials. Lancet. 2000;356(9246):1955–64. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)03307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Law MR, Morris JK, Wald NJ. Use of blood pressure lowering drugs in the prevention of cardiovascular disease: meta-analysis of 147 randomised trials in the context of expectations from prospective epidemiological studies. BMJ. 2009;338:b1665. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldman RD, Campbell NR, Wyard K. Canadian Hypertension Education Program: the evolution of hypertension management guidelines in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2008;24(6):477–81. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70621-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Screening for high blood pressure: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(11):783–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-11-200712040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839–42. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. Epub 2010 Jul 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schünemann H, Brozek J, Oxman A, editors. GRADE handbook for grading the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations. The GRADE Working Group; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leenen FH, Dumais J, McInnis NH, Turton P, Stratychuk L, Nemeth K, et al. Results of the Ontario survey on the prevalence and control of hypertension. CMAJ. 2008;178(11):1441–9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu R, So L, Mohan S, Khan N, King K, Quan H. Cardiovascular risk factors in ethnic populations within Canada: results from national cross-sectional surveys. Open Med. 2010;4(3):e143–53. Epub 2010 Aug 10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.First Nations Regional Health Survey. RHS phase 2 (2008/10) preliminary results. 2nd ed. Ottawa, ON: The First Nations Information Governance Centre; 2011. Available from: www.rhs-ers.ca/sites/default/files/ENpdf/RHSPreliminaryReport31May2011.pdf. Accessed 2013 Jul 18. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Health Canada . A statistical profile on the health of First Nations in Canada: determinants of health, 1999 to 2003. Ottawa, ON: Health Canada; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romundstad PR, Magnussen EB, Smith GD, Vatten LJ. Hypertension in pregnancy and later cardiovascular risk: common antecedents? Circulation. 2010;122(6):579–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.943407. Epub 2010 Jul 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones CA, Davachi S, Nanji A, Mawani S, Faris P, Wang X, et al. Indo-Central Asian cardiovascular health and management program (ICACHAMP) [abstract 510] Can J Cardiol. 2008;24(Suppl SE) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones CA, Mawani S, King KM, Allu SO, Smith M, Mohan S, et al. Tackling health literacy: adaptation of public hypertension educational materials for an Indo-Asian population in Canada. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Public Health Agency of Canada . Report from the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System: hypertension in Canada, 2010. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2010. Available from: www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/cd-mc/cvd-mcv/ccdss-snsmc-2010/pdf/CCDSS_HTN_Report_FINAL_EN_20100513.pdf. Accessed 2013 Aug 12. [Google Scholar]