Complications can arise from spilled gallstones during cholecystectomy. A surgeon should make every effort to avoid gallbladder perforation and spillage of stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Keywords: Cholecystectomy, Laparoscopic, Gallstones, Volvulus, Cecal

Abstract

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the procedure of choice for the treatment of symptomatic biliary disease. There is currently no agreement on the management of spilled gallstones, which commonly occurs during laparoscopic cholecystectomy and may produce significant morbidity. We present a case of spilled gallstones causing cicatrical cecal volvulus and also provide a review of pertinent literature.

INTRODUCTION

Controversy has surrounded laparoscopic cholecystectomy since it was first performed in 1985 and reported in 1986 by Eric Muhe.1,2 Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has become the procedure of choice for the treatment of symptomatic biliary disease, but there is still debate regarding the disposition of spilled gallstones. We present the first reported incidence of gangrenous perforation secondary to cicatrical cecal volvulus.

CASE REPORT

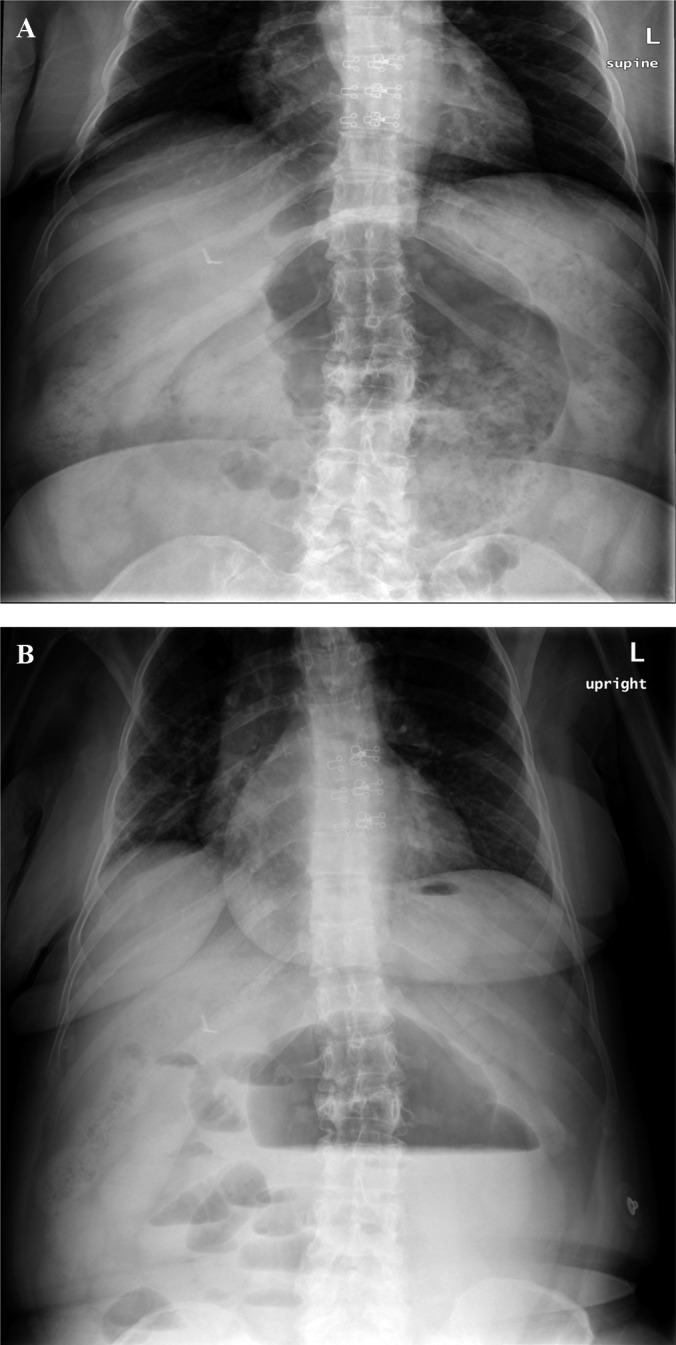

A 71-y-old female patient was transferred from an outside hospital with primary complaints of progressive diffuse abdominal pain, associated with nausea and emesis. The pain had lasted for 24 h. Initial presentation was diagnosed as constipation, which was treated with oral magnesium citrate. The patient returned several hours later with progressive symptoms. Complete bowel obstruction was diagnosed following computed tomography (CT) imaging. The patient was then transferred to our institution. Past medical history was significant for asthma, hypertension, fibromyalgia, degenerative disc disease, chronic pain disorder, chronic affect disorder, hypothyroidism, major depressive disorder, cerebral meningioma, coronary artery disease, and congestive heart failure. Past surgical history included craniotomy with resection of meningioma, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed 15 y before. The patient also presented with hypotension complicated by a prescribed daily calcium channel blocker. Other vital signs were within normal limits. Physical examination demonstrated a distended abdomen with involuntary guarding and rebound tenderness. Laboratory findings revealed an elevated white blood cell count of 11,200, with 87% neutrophils. Mild microcytic anemia was noted along with mild hyperglycemia (165 mg/dL), mild acute renal insufficiency (BUN/cre 32/1.4 mg/dL), and a hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis (Cl 96 mmol/L & CO2 35 mmol/L). Initial arterial blood gas (ABG) determination at 40% FiO2 demonstrated an elevated pH of 7.50, normocarbia with a pCO2 of 42 mm Hg, hypoxia with a pO2 of 30 mm Hg, and an elevated base excess at 8.7 mmol/L. Lactate was elevated at 4.0 mmol/L. Roentgenographic (Figures 1a, 1b) and CT (Figures 2 & 3) imaging were reviewed and intestinal obstruction secondary to cecal volvulus was noted. Intraabdominal sepsis secondary to cecal volvulus was detected.

Figure 1.

a. Supine Roentgenogram demonstrating “coffee bean” sign. Figure 1b. Upright Roentgenogram demonstrating air-fluid levels with “coffee bean” sign.

Figure 2.

CT scout film demonstrating “coffee bean” sign.

Figure 3.

CT coronal image demonstrating cecal volvulus.

Carbapenem antibiotics were initiated, and fluid resuscitation was started with bolused crystalloid as the patient was prepared for emergency exploratory laparotomy. Purulent ascites effused from the abdominal cavity immediately upon entry and was evacuated with suction irrigation. Gangrenous cecal volvulus was promptly diagnosed. Multiple cholesterol gallstones were found embedded within a dense mesenteric cicatrix causing ileocolic torsion. Mesenteric venous outflow was obstructed with hemostats to prevent circulation of the products of ischemia and necrosis. The volvulus was then reduced and ileocectomy was performed. Anastomosis was deferred due to the patient's vasopressor requiring septic shock. Additional justification for intestinal discontinuity and damage control election was the patient's perceived need for significant volume resuscitation with attendant iatrogenic bowel edema, clinically apparent coagulopathy and hypothermia. Abdominal exploration revealed multitudinous gallstones throughout the abdomen. Marked sclerosis associated with these gallstones was appreciated along the left anatomic gutter, the right subphrenic space, and within the mesentery and omentum. Gallstones were found embedded in Couinaud segment 7 of the liver and the sigmoid colon. All encountered cholesterol gallstones were removed and the abdomen was irrigated. Temporary abdominal closure was provided with a negative pressure intraabdominal dressing, and the patient was transported to the intensive care unit for resuscitation.

Following resuscitation, the patient returned to the operating room within 24 h for peritoneal toilet, reexamination, and ileocolostomy anastomosis. The patient tolerated these procedures well and was transferred to the floor. She progressed to a solid diet within 7 d and was discharged. The patient's recovery was smooth and limited to incisional pain controlled with oral analgesics. Pathology evaluation reported the following findings: “Focally transmural necrosis of the cecum associated with marked acute inflammation and focal hemorrhage, fibrous serosal adhesions, fibrous obliteration of the appendiceal lumen, and focal foreign body reaction to embedded periappendiceal gallstones.”

DISCUSSION

The reported incidence of gallbladder perforation during laparoscopic cholecystectomy varies from 6% to 40%, and the incidence of stone spillage varies from 5.7% to 12.3%.3–6 Established risk factors that predispose to gallbladder perforation during laparoscopic cholecystectomy are surgeon inexperience, acute cholecystitis, tensely distended gallbladder, right upper quadrant adhesive disease, thermal injury during dissection, and excessive traction.3,7,8

Morbidity related to spilled stones occurs with an incidence of 0.08% to 6%.4,9 There are currently no indications for conversion to open cholecystectomy for retrieval of spilled stones, but risk factors for postoperative complications have been identified.10 These established risk factors are old age, spillage of infected bile, acute cholecystitis, pigmented stones, stones (>15cm), and perihepatic localization of lost stones.4,10,11 Multiple gallstones were found throughout the abdomen of the patient described herein. Informed consent was obtained by discussing risks such as gallbladder perforation and benefits of laparoscopy with the patient.

A review of the literature found a report on mechanical bowel obstruction as a consequence of spilled gallstones.12 Cases of volvulus of the small intestines, cecum, and sigmoid have been reported following laparoscopic cholecystectomy, but they have not been directly attributed to ectopic intraperitoneal gallstones. Bariol et al.13 reported the first case of cecal volvulus after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a patient with mobile cecum syndrome, though no anatomic abnormality was found. Duron et al.14 presented a second case of cecal volvulus following laparoscopic cholecystectomy in a patient predisposed to the condition due to malrotation. The third case report by Ferguson et al.15 described cecal volvulus secondary to cecal bascule, occurring 6 mo after complicated laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The current case study describes the first reported cecal volvulus secondary to iatrogenic laparoscopic gallbladder perforation with unretrieved ectopic intraperitoneal gallstones, causing cicatrical mesenteric rotation. Peritoneal adhesions secondary to ectopic intraperitoneal gallstones have been reported in both animal models and humans.8,16 The number of ectopic concrements within the peritoneal space and the presence of infected bile appears directly related to the development of adhesions. Cecal mobility as a result of abnormal peritoneal fixation and anatomical distortion secondary to intraperitoneal adhesions or masses are predisposing risk factors for cecal volvulus.17,18 The patient presented herein developed marked fibrosis of the cecal mesentery leading to sclerotic contracture and cecal volvulus. Multiple ectopic gallstones were located throughout the peritoneal cavity with marked accumulation in the affected cecal mesentery.

Erosion of spilled biliary concrements has been reported into the hepatic parenchyma and sigmoid colon.19–21 Ectopic gallstones were found eroding into the liver parenchyma of segment 7 and the sigmoid colon in our subject patient. No hepatic fistula or sigmoid perforation developed but concern for such complications is based on prior reporting.

Radiographic evaluation is recommended when a clinician suspects cecal volvulus, as it may lead to perforation or strangulation of bowel. In addition, a small bowel obstruction, appendicitis or inflammatory bowel disease may be indistinguishable from volvulus at presentation.22 Plain film may demonstrate classic “bent inner tube” or “coffee bean sign,” but most often shows a collection of gas-filled colon extending from the right lower to left upper abdominal quadrant, similar to a coffee bean with a paucity of distal air or feces.17 This classic finding is evident in the patient's abdominal roentgenograms and CT scout film (Figures 1a, 1b & 2). Barium enema may demonstrate a “bird beak sign” as contrast tapers at the site of volvulus, but should be deferred if clinical concerns for perforation exist due to increased morbidity and mortality.23–25 Computed tomography (CT) has become the preferred radiographic method to investigate volvulus, as shown by “coffee bean,” “bird beak” and “whirl” signs.17 The “whirl” sign describes the torsion of cecum and ileum with enhancing mesenteric vessels. These classic findings are shown in the CT imaging (Figure 3).

Endoscopy is an accepted diagnostic and initial therapeutic method for sigmoid volvulus, but colonoscopy is limited in the management of cecal volvulus with successful reduction of volvulus in approximately 30% to 50% of cases.26–28 Surgical detorsion with or without cecopexy, cecostomy, ileocectomy, and right colectomy are possible treatment options, but ileocectomy or colectomy should only be used in cases with bowel necrosis. Surgical detorsion by open or laparoscopic approach demonstrates a recurrence rate of 50% and a mortality rate as high as 25%.22,27 Detorsion with cecopexy results in decreased recurrence rates of 30% to 40%, although mortality remains high.27 Initial reports for laparoscopic detorsion and cecopexy show decreased morbidity when compared with the open approach, though recurrence rates are unknown.29 Detorsion with cecostomy provides another option for fixation of the cecum with similar recurrence rates to those of cecopexy, although mortality rates may be higher.2 Resection by ileocectomy or colectomy with primary anastomosis is an accepted surgical option in all cases of cecal volvulus, offering the lowest risk of recurrence.26 In the setting of gangrenous bowel and perforation, resection should be performed to remove affected bowel and allow anastomosis of nonischemic tissues.30

CONCLUSION

The current study reports a case of cecal volvulus caused by spilled gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Adhesion formation has previously been linked to the formation of cecal volvulus, but ours is the first report of spilled gallstones causing intraperitoneal adhesions and resultant volvulus. This case also emphasizes spillage of multiple gallstones as a direct cause of postoperative morbidity. In a patient presenting with multiple risk factors for gallbladder perforation or stone spillage, a surgeon should make every attempt to avoid gallbladder perforation and spillage of stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Contributor Information

Michael W. Morris, Jr., Department of Surgery, University of Mississippi School of Medicine, Jackson, MS..

Andrea K. Barker, Department of Surgery, University of Mississippi School of Medicine, Jackson, MS..

James M. Harrison, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Mississippi School of Medicine, Jackson, MS..

Andrew J. Anderson, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Mississippi School of Medicine, Jackson, MS..

Wesley B. Vanderlan, Department of Surgery, University of Mississippi School of Medicine, Jackson, MS..

References:

- 1. Litynski GS. Erich Muhe and the rejection of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (1985): a surgeon ahead of his time. JSLS. 1998;2:341–346 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jani K, Rajan PS, Sendhikumar K, Palanivelu C. Twenty years after Erich Muhe: persisting controversies with the gold standard of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Minim Access Surg. 2006;2(2):49–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Frola C, Cannici F, Cantoni S, Tagliafico E, Luminati T. Peritoneal abscess formation as a late complication of gallstones spilled during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Radiol. 1999. February;72(854):201–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schafer M, Suter C, Klaiber C, Wehrli H, Frei E, Krahenbuhl L. Spilled gallstones after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A relevant problem? A retrospective analysis of 10,174 laparoscopic cholecystectomies. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:291–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Diez J, Arozamena C, Guiterez L. Lost gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. HPB Surg. 1998;11:105–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Memon MA, Deeik RK, Maffi TR, Fitzgibbons RJ. The outcome of unretrieved gallstones in the peritoneal cavity during laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective analysis. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:848–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Woodfield JC, Rodgers M, Windsor JA. Peritoneal gallstones following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1200–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Helme S, Smadain T, Sinha P. Complications of spilled gallstones following laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a case report and literature overview. J Med Case Reports. 2009;3:8626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hand AH, Self ML, Dunn E. Abdominal wall abscess formation two years after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. JSLS. 2006;10:105–107 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arishi AR, Rabie ME, Khan MSH, et al. Spilled gallstones: the source of an enigma. JLS. 2008;12(3):321–325 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brockmannn JG, Kocher T, Senninger NJ, Schurmann GM. Complications due to gallstones lost during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. An analysis of incidence, clinical course, and management. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1226–1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tekin A. Mechanical small bowel obstruction secondary to spilled stones. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1998;8:157–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bariol Sv, McEwen HJ. Cecal volvulus after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:79–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Duron JJ, Hay JM, Msika S, et al. Prevalence and mechanisms of small intestinal obstruction following laparoscopic abdominal surgery: A retrospective multicenter study. Arch Surg. 2000;135:208–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Walsh S, Lee J, Stokes M. Sigmoid volvulus after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. An unusual complication. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zorluoglu A, Ozguc H, Yilmazlar T, Guney N. Is it necessary to retrieve dropped gallstones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy? Surg Endosc. 1997;11(1):64–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Moore CJ, Corl FM, Fishman EK. CT of cecal volvulus: unraveling the image. AJR. 2001;177(1):95–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Frank AJ, Goffner LB, Fruauff AA, Losada RA. Cecal volvulus: the CT whirl sign. Abdom Imaging. 1993;18:288–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cohen RV, Pererira PRB, Barros MV. Is the retrieval of lost peritoneal gallstones worthwhile? Surg Endosc. 1994;8:875–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nicolai R, Foley RJ. Complications of spilled gallstones. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1992;2:362–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jost CJ, Smith JL, Smith RS. Spontaneous hepatic hemorrhage secondary to retained intraperitoneal gallstones. Am Surg. 2000;66:1059–1060 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Montes H, Wolf J. Cecal volvulus in pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2554–2556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Catalano O. Computed tomographic appearance of sigmoid volvulus. Abdom Imagin. 196;21:314–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oren D, Antmanalp SS, Aydinli B, et al. An algorithm for the management of sigmoid colon volvulus and the safety of primary resection: experience with 827 cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:765–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sung JP, O'Hara VS, Lee CY. Barium peritonitis. West J Med. 1977;127(2):172–176 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Madiba TE, Thomson SR. The management of cecal volvulus. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:264–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Consorti ET, Liu TH. Diagnosis and treatment of caecal volvulus. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:772–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Renzulli P, Maurer CA, Netzer P, Buchler MW. Preoperative colonoscopic derotation is beneficial in acute colonic volvulus. Dig Surg. 2002;19:223–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tsushimi T, kurazumi H, Takemoto Y, Oka K, Inokuchi T, Seyama A. Laparoscopic cecopexy for mobile cecal syndrome manifesting as cecal volvulus: report of case. Surg Today. 2008;38:359–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Majeski J. Operative therapy for cecal volvulus combining resection with colopexy. Am J Surg. 2005;189:211–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]