Abstract

Mutations in canine superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) have recently been shown to cause canine degenerative myelopathy, a disabling neurodegenerative disorder affecting specific breeds of dogs characterized by progressive motor neuron loss and paralysis until death, or more common, euthanasia. This discovery makes canine degenerative myelopathy the first and only naturally occurring non-human model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), closely paralleling the clinical, pathological, and genetic presentation of its human counterpart, SOD1-mediated familial ALS. To further understand the biochemical role that canine SOD1 plays in this disease and how it may be similar to human SOD1, we characterized the only two SOD1 mutations described in affected dogs to date, E40K and T18S. We show that a detergent-insoluble species of mutant SOD1 is present in spinal cords of affected dogs that increases with disease progression. Our in vitro results indicate that both canine SOD1 mutants form enzymatically active dimers, arguing against a loss of function in affected homozygous animals. Further studies show that these mutants, like most human SOD1 mutants, have an increased propensity to form aggregates in cell culture, with 10-20% of cells possessing visible aggregates. Creation of the E40K mutation in human SOD1 recapitulates the normal enzymatic activity but not the aggregation propensity seen with the canine mutant. Our findings lend strong biochemical support to the toxic role of SOD1 in canine degenerative myelopathy and establish close parallels for the role mutant SOD1 plays in both canine and human disorders.

INTRODUCTION

For two decades, data from human studies and transgenic animal models have shown that mutations in superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) cause a form of dominantly-inherited amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a progressive neurodegenerative disorder resulting in motor neuron loss, paralysis, and death 3-5 years after symptom onset (Kiernan et al., 2011; Rosen et al., 1993; Turner and Talbot, 2008). To date, over 160 mutations have been identified in SOD1, which normally functions as a Cu,Zn-metalloenzyme that converts superoxide anions to molecular oxygen and H2O2 (for a list of mutations, see http://alsod.iop.kcl.ac.uk/). Although SOD1 mutations occur throughout the protein and result in a range of disease durations, they are united in their reduced stability and increased ability to aggregate. In fact, SOD1 aggregates in motor neurons are the histopathological hallmark of SOD1 ALS, a property that extends to animal models, cell culture overexpression systems, and experiments with recombinant protein. As SOD1-mediated ALS is a dominantly-inherited disease, this toxic gain of function becomes important in the setting of the remaining functional copy of wild-type (WT) SOD1, yet the mechanism responsible for how this toxic gain of function contributes to disease is unknown.

Until recently, with the exception of the artificial G86R and G93R mutations created in mouse and zebrafish SOD1, respectively, humans were the only organisms in which ALS occurred, and the only organisms where mutations in SOD1 responsible for causing this disease have been described (Ramesh et al., 2010; Ripps et al., 1995). That changed with GWAS data linking a mutation in canine SOD1 (cSOD1) to canine degenerative myelopathy (DM), a progressive neurodegenerative disorder in dogs with striking similarities to the clinical progression of human ALS (Awano et al., 2009). Specifically, canine DM affects multiple dog breeds toward the latter half of their lifespan and is characterized by an often asymmetric onset of paraparesis and ataxia in the hind limbs that progresses to paraplegia and muscle atrophy within one year from onset of signs. Although elective euthanasia occurs for a majority of these dogs by this stage, those that have been allowed to progress show ascension of the disease to include the forelimbs, ultimately resulting in flaccid tetraplegia and dysphagia. The entire course of the disease can last as long as 3 years (Coates and Wininger, 2010). Histopathology of spinal cords from affected dogs show a similar pattern of myelin and axonal loss replaced with astrogliosis seen in human ALS, and immunohistochemistry reveals the same SOD1 aggregates in motor neurons that are present in humans and rodent models with human SOD1 (hSOD1) mutations (Awano et al., 2009; Bruijn, 1998).

Dog models of human disease offer specific advantages over traditional rodent models. For example, many human diseases occur naturally in dogs that would otherwise need to be artificially induced in rodent models. Furthermore, the limited genetic diversity of dog breeds, faster aging, shared environment with humans, and availability of advanced medical care facilitate expedited clinical trials for promising pharmacological agents targeting human disease. One example is that many canine models of human cancers, which develop sporadically in dogs, have been found to share several genetic similarities with human cancers and have been successfully used in clinical trials (Rankin et al., 2012; Rowell et al., 2011). Therefore, with these advantages in mind, further characterization of the canine model of ALS is warranted. Here, we report the first biochemical characterization of the only two cSOD1 mutations known to be associated with canine DM – the E40K mutation originally described in a number of breeds and the T18S mutation from a case report detailing a Bernese Mountain dog with canine DM (Awano et al., 2009; Wininger et al., 2011). We show that spinal cords of DM dogs contain detergent-insoluble mutant SOD1 that correlates with disease severity and that both mutants are enzymatically active dimers that possess an increased aggregation propensity in vitro. Our results elucidate important similarities between human and canine SOD1 with respect to enzymatic function and aggregation propensity, adding a biochemical dimension to the clinical and histopathological similarities between canine DM and SOD1-mediated human ALS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Detergent extraction of SOD1 aggregates

Frozen thoracic spinal cord sections were obtained from age-matched control dogs and dogs with increasing severity of canine DM. Detergent extraction of SOD1 aggregates was preformed as previously described (Prudencio et al., 2010). Briefly, 100 mg of frozen tissue was thawed on ice and homogenized via hand blender in 10 w/v TEN buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl) with protease inhibitors (Sigma). The homogenate was then mixed with an equal volume of 2× Extraction Buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, protease inhibitors), mixed via sonication, and spun cold at 100,000×g for 10 minutes in a Beckman Ultracentrifuge. The supernatant, representing the detergent soluble fraction S1, was transferred to a new tube. The pellet was washed twice by resuspension in 1× extraction buffer via sonication and spun at 100,000×g for 10 minutes, cold. After the final wash, the supernatant was discarded and the pellet, designated as P2, resuspended via sonication in Buffer 3 (10 mM Tris, pH 8, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.25% SDS, 0.5% Na-deoxycholate, protease inhibitors). Protein concentration for the S1 and P2 fractions was determined by BCA assay (Pierce). The experiment was repeated once.

Generation of SOD1 Constructs

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol (Invitrogen) from frozen brain tissue obtained from control and DM-affected dogs according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA was then reverse transcribed using oligo dT primers to generate cDNA (SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT-PCR, Invitrogen). Wild-type (WT) and E40K cSOD1 were amplified via PCR using primers with engineered restriction endonuclease sites at the 5′ ends. To subclone cSOD1 cDNA into pGEX4T-1 (GE Healthcare) using EcoRI and NotI, the forward primer was 5′-agtcgaattcATGGAGATGAAGGCCGTGTGC-3′ and the reverse primer was 5′-atcggcggccgcTTATTGGGCGATCCCAATGACA-3′. To subclone into pEYFP-C1 (Clontech) using EcoRI and BamHI, the forward primer was 5′-agtcgaattcaATGGAGATGAAGGCCGTGTGC -3′and the reverse primer was 5′-atcgggatccTTATTGGGCGATCCCAATGACA-3′. The T18S mutant was obtained by site-directed mutagenesis of the wild-type SOD1 using the primers 5′-GTGGAGGGCTCCATCCACTTCGTGCAGAAG-3′ and 5′-CTTCTGCACGAAGTGGATGGAGCCCTCCAC-3′. Positive clones were verified by sequencing and subcloned into pGEX4T-1 and pEYFP-C1 using primers previously described. The human E40K mutant was generated via site-directed mutagenesis of wild-type hSOD1 using the primers 5′-GCATTAAAGGACTGACTAAAGGCCTGCATGGATTC-3′ and 5′-GAATCCATGCAGGCCTTTAGTCAGTCCTTTAATGC-3′. The human E40G mutant was similarly generated using the primers 5′-GCATTAAAGGACTGACTGGAGGCCTGCATGGATTC-3′ and 5′-GAATCCATGCAGGCCTCCAGTCAGTCCTTTAATGC-3′. Positive clones were verified by sequencing and subcloned into pEYFP-C1 with the primers 5′-agtcgaattcaGCCACGAAGGCCGTGT-3′ and 5′-atcgggatccTTATTGGGCGATCCCAATTACACC-3′ and the restriction endonucleases EcoRI and BamHI.

Untagged versions of the above plasmids for mammalian expression were created by subcloning human and canine SOD1 constructs into pCI-NEO (Promega) with a forward primer containing an EcoRI site and a Kozak sequence and a reverse primer containing a NotI site. For cSOD1, the primers were 5′-agtcgaattcgccaccATGGAGATGAAGGCCGTGTGC-3′ and 5′-atcggcggccgcTTATTGGGCGATCCCAATGACA-3′. For hSOD1, the primers were 5′-agtcgaattcgccaccATGGCGACGAAGGCCGTG-3′ and 5′-atcggcggccgcTTATTGGGCGATCCCAATTACACC-3′. Positive clones were verified by sequencing.

Cell Culture, Transfection, and Microscopy

NSC34 cells were grown in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum with 10 U/mL penicillin and 10 μg/mL streptomycin. Cells were split into 12-well plates at 5×105 cells/well 18 hours prior to transfection with media lacking antibiotics. Cells were transiently transfected with 900 ng of midi-prep DNA (Promega) and 6 μL Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Twenty four hours later, cells were split into 24-well plates at varying densities for microscopy, with a small aliquot taken for protein analysis. Forty eight hours after transfection, cells were washed once with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 minutes at room temperature, followed by three PBS washes. Cells were counterstained with DAPI in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes, followed by three PBS washes. Images were captured on a Nikon Eclipse TE300 inverted microscope using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices). Observers were blinded during cell counts, and at least 120 cells were counted for each condition in three separate experiments.

Recombinant SOD1 Production

Rosetta 2 E. coli (Novagen) containing GST-tagged cSOD1 WT, E40K, and T18S and hSOD1 WT, G85R, or E40K in pGEX4T-1 were grown in LB media with 100 μg/mL ampicillin and 25 μg/mL chloramphenicol at 37°C overnight, then diluted 1:10 in pre-heated LB with antibiotics and grown for two hours at 37°C. Protein production was induced for a further four hours after the addition of 1.0 mM IPTG. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 3500×g for 25 minutes, washed with 1× PBS, centrifuged again, and frozen until needed for purification.

Cell pellets were thawed on ice and resuspended in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mM DTT, pH 8.0). Cells were incubated with 4 mg/mL lysozyme (Sigma) for 15 minutes at room temperature, followed by sonication and centrifugation at 10,000×g for 15 minutes. 600 μL of a 50% slurry of pre-equilibrated glutathione sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare) was then added to each supernatant and incubated with end-over-end rotation for 18 hours at 4°C. Beads were then washed three times with PBS and the bound SOD1 proteins cleaved from GST with the Thrombin Cleavage Capture Kit (Novagen) as per manufacturer’s instructions. SOD1 proteins were metallated by dialysis against 100 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl, and 200 μM CuCl2 for 3.5 hours, followed by dialysis against 100 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, and 200 μM ZnCl2 for 3.5 hours as previously described (Chia et al., 2010). Metallated proteins were then dialyzed overnight at 4°C against 20 mM Tris (pH 7.8), 10 mM NaCl, and concentrated using Amicon Ultra centrifugal filters with a 10K membrane. SOD1 concentrations were determined using the Bradford assay.

SOD1 Dismutase Activity Assay

SOD1 enzymatic activity was determined using the SOD Determination Kit (Sigma) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Recombinant cSOD1 WT, E40K, T18S and hSOD1 WT, G85R, and E40K were diluted to 50 ng/μL with 20 mM Tris (pH 7.8), 10 mM NaCl, then 10-fold serially diluted down to 50 pg/μL. SOD1 from bovine erythrocytes (Sigma) was used to generate a standard curve from 0.1 U/mL to 50 U/mL. The assay was performed a total of three times.

Denaturing and Partially Denaturing SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting

For denaturing gels, boiled samples were run on a 14% acrylamide Tris gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked in PBS with 0.05% Tween (PBS-T) containing 5% milk for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated with anti-SOD1 (FL-154) antibody (Santa Cruz) in 5% milk PBS-T overnight at 4°C. Following three washes, membranes were incubated with donkey anti-rabbit IgG, horseradish peroxidase-linked whole antibody (GE Healthcare) at 1:5000 in 5% milk PBS-T for 2 hours at room temperature. Blots were developed with ECL 2 Western Blotting Substance (Pierce) and visualized on a G:Box Chemi XT4 imager (Syngene). Unless otherwise indicated, Western blots were repeated twice.

Partially denaturing PAGE was performed as previous described (Tiwari and Hayward, 2003). Briefly, 1 μg of recombinant cSOD1 WT, E40K, T18S and hSOD1 WT and G85R were mixed with partially denaturing sample buffer without a reducing agent (62 mM Tris, 10% glycerol, 0.05% bromophenol blue, 0.4% SDS, pH 6.8) and incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. Samples were then run on a 14% acrylamide Tris gel (both the gel and the running buffer contained 0.1% SDS) and stained with Gel Code Blue (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. This protocol was repeated for recombinant hSOD1 E40K. The experiments were repeated once with a fresh preparation of recombinant canine SOD1.

Filter Trap Assay

For TFE-treated recombinant protein, 2 μg of recombinant cSOD1 WT, E40K, and T18S were incubated in 0%, 10%, and 20% trifluoroethanol (TFE) for 6 hours at 37°C with agitation. Samples were then dialyzed against 20 mM Tris (pH 7.8), 10 mM NaCl overnight at 4°C. For untagged human and canine SOD1 constructs expressed in NSC34 cells, cells were washed once in PBS, collected, and lysed via sonication in PBS containing protease inhibitors. Samples were spun at 800×g for 10 minutes to remove large cell debris without removing SOD1 aggregates. Protein concentration was determined via Bradford assay and adjusted to 1 μg/μL. The dialyzed TFE-treated recombinant SOD1 proteins or 150 μg of cell lysate were then run over a 0.2 μM cellulose acetate membrane on a Minifold II Slot Blot System (Whatman) and washed once with PBS. Membranes were blocked in 5% milk PBS-T for 1 hour at room temperature and incubated with anti-SOD1 (FL-154) antibody (Santa Cruz) in 5% milk PBS-T overnight at 4°C. Following three washes, membranes were incubated with donkey anti-rabbit IgG, horseradish peroxidase-linked whole antibody (GE Healthcare) at 1:5000 in 5% milk PBS-T for 2 hours at room temperature. Blots were developed with ECL 2 Western Blotting Substance (Pierce) and visualized on a G:Box Chemi XT4 imager (Syngene). Experiments were repeated a total of three times.

RESULTS

Spinal cords of DM dogs contain detergent-insoluble mutant SOD1 that increases with disease severity

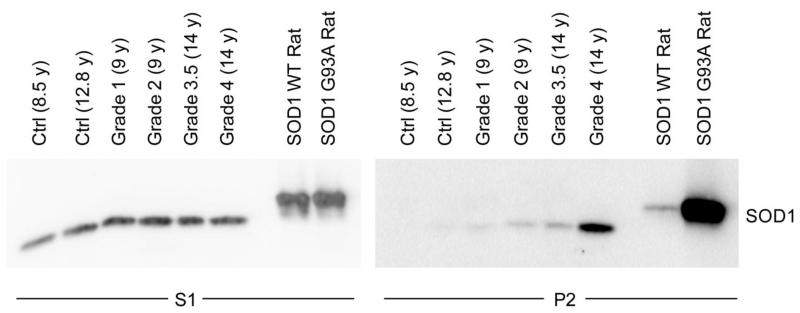

The presence of detergent-insoluble mutant SOD1 species in spinal cords of SOD1 transgenic mice and patients with SOD1 A4V mutations has been well characterized (Deng et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2003). To determine if this biochemical property was also found in DM, we fractionated spinal cords from two non-affected dogs and four homozygous SOD1 E40K dogs with DM of increasing disease grade (See (Shelton et al., 2012) for details on DM grade) into detergent-soluble (designated S1) and –insoluble (designated P2) fractions. We included non-affected dogs of different ages to control for age-related SOD1 accumulation, which has been shown in SOD1 WT transgenic mouse and rat models, as many dogs with Grade 3 and 4 DM are >14 years old (Prudencio et al., 2009a). Spinal cords from transgenic rats overexpressing SOD1 WT or G93A were used as controls. Western blot analysis revealed the presence of detergent-insoluble SOD1 in DM-affected dog spinal cords that increased with disease severity, despite approximately identical levels of detergent-soluble SOD1 between control and DM-affected dogs (Figure 1). As expected, a small amount of detergent-insoluble WT cSOD1 was found in the older non-affected spinal cord, but this level was below that of even Grade 1 DM. While advanced age may result in some degree of detergent-insoluble SOD1 accumulation in canine spinal cords, it does not account for the significant increase seen in DM-affected spinal cords. Thus, we conclude that the E40K mutation shares the same accumulation of detergent-insoluble aggregates as seen in human ALS and rodent models.

FIGURE 1. Canine DM spinal cords contain detergent-insoluble SOD1 that correlates with disease severity.

Detergent extraction of cSOD1 from thoracic spinal cord sections of non-affected dogs (Ctrl) and DM-affected dogs of increasing disease severity (Grades 1-4, with Grade 1 mild and Grade 4 severe) show increasing levels of detergent-insoluble mutant SOD1 (P2 fraction) with increasing DM Grade. Age is indicated in parentheses. As controls, transgenic rats overexpressing hSOD1 WT or SOD1 G93A were included. The S1 lanes contain 16 μg protein, except for the transgenic rat samples at 4 μg, and the P2 lanes contain 18.6 μg protein.

Properties of canine SOD1 mutations

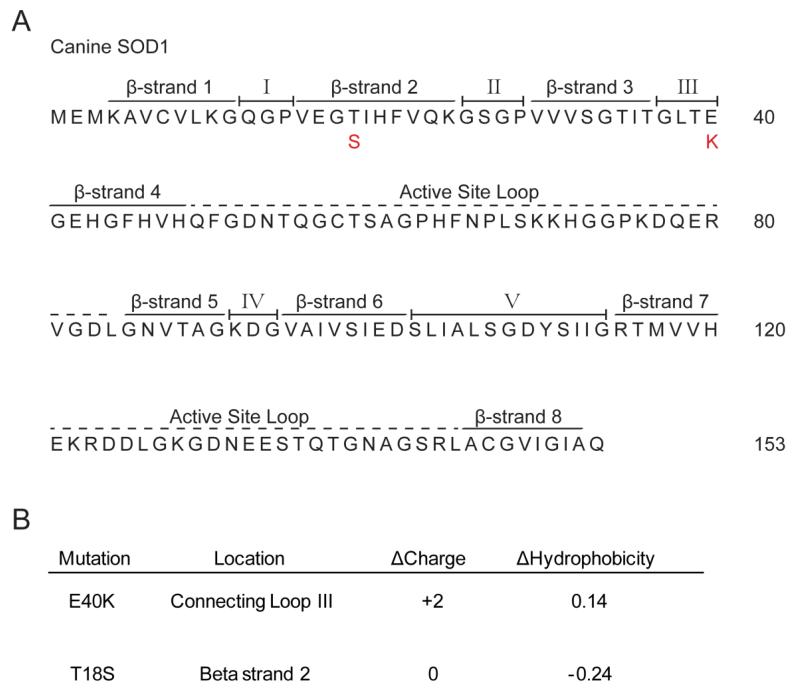

To date, only two mutations in cSOD1 have been described in the literature, as compared to the >120 mutations known for hSOD1 (Awano et al., 2009; Wininger et al., 2011). The sequence for cSOD1 was originally determined from a study looking for mutations in dogs with a form of spinal muscular atrophy and is hypothesized to contain eight beta sheets and a metal-binding active site similar to its human counterpart (Green et al., 2002). As can be seen from the primary amino acid sequence, the E40K mutation falls within connecting loop III and results in a +2 charge shift, while the T18S mutation occurs in the second beta strand and does not change overall protein charge (Figure 2). Both mutations result in minor changes in hydrophobicity. Such varying characteristics reflect the inconsistencies seen in trying to correlate protein charge, hydrophobicity, and even aggregation propensity to disease onset and progression in familial ALS (Prudencio et al., 2009b). As neither canine mutation disrupts the metal binding region of the enzyme, we predicted that both mutations retain dismutase activity, which lends credibility to a gain of toxic function and not loss of function in the dog model where a majority of dogs homozygous for mutant SOD1 show the DM phenotype.

FIGURE 2. Canine SOD1 primary sequence and known SOD1 mutations.

(A) Similar to hSOD1, cSOD1 contains 8 beta sheets interspersed by connecting loops and surrounding an active site that binds copper. Known cSOD1 mutations are depicted in red below the primary sequence. (B) Location, Δcharge, and Δhydrophobicity for known cSOD1 mutations. Δcharge calculation performed with PROTEIN CALCULATOR v3.3 (Scripps). Δhydrophobicity calculated according to (Chiti et al., 2003).

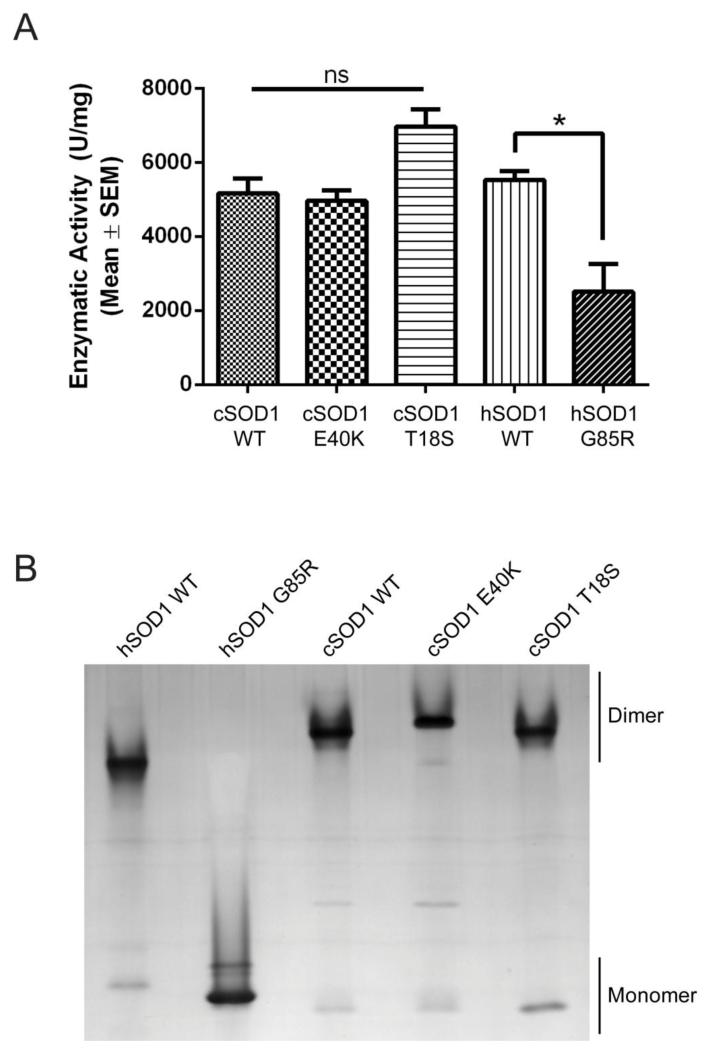

To measure enzymatic activity, a commercially available superoxide dismutase activity kit was used with recombinant cSOD1 WT, E40K, and T18S proteins. As controls, we compared dismutase activity with recombinant hSOD1 WT and G85R, a metal binding region mutant with significantly reduced activity (Borchelt et al., 1994). As predicted from the structural location of these mutants (i.e. outside of the metal binding region), both cSOD1 mutants retain full enzymatic activity (Figure 3A), providing evidence in favor of a toxic gain of function in dogs homozygous for these mutations.

FIGURE 3. Canine SOD1 mutants form enzymatically active dimers.

(A) Dismutase activity assay performed on recombinant canine and human SOD1 proteins. No significant difference between cSOD1 WT and E40K or T18S. * p<0.05 (B) Partially denaturating PAGE gel showing that cSOD1 WT, E40K, and T18S predominantly migrate as dimers, while the metal binding hSOD1 mutant G85R exists as a monomer.

Since both canine mutants were dismutase active, we predicted that they would remain as structural dimers under partially denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as consistent with previous reports of human mutations (Tiwari and Hayward, 2003). Using a lower SDS concentration (0.4%) and no reducing agent or boiling, this prediction was confirmed (Figure 3B). Both the E40K and T18S cSOD1 mutants migrated predominantly as dimers, while the hSOD1 G85R mutant migrated mostly as a monomer, reflecting its well documented monomeric state.(Zetterstrom et al., 2007) The shifted position of the E40K mutant on the gel reflects its +2 charge shift as compared to the WT or T18S proteins (Figure 2B). This is in agreement with our data reflecting full enzymatic activity in these mutants indicating the existence of a functional dimer. Thus, our data confirm that both cSOD1 mutants form enzymatically active dimers and, more importantly, that affected dogs homozygous for either mutant do not experience a loss of dismutase activity.

Canine SOD1 mutations are unstable and prone to aggregation

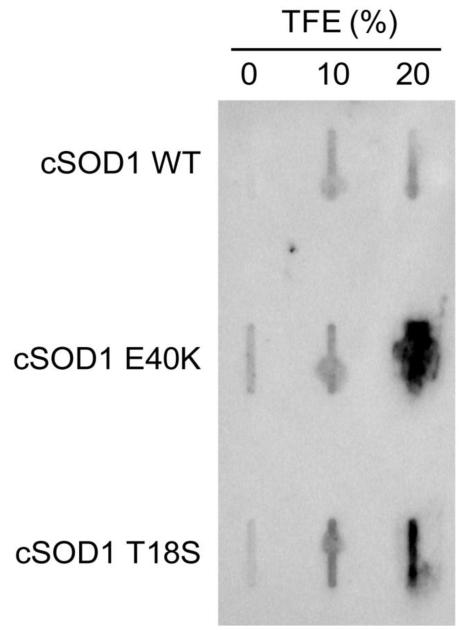

As has been confirmed with hSOD1 mutants, we hypothesized that mutations in the cSOD1 protein would result in reduced stability and increased aggregation potential (Münch and Bertolotti, 2010). We observed that treatment of the canine mutants, but not WT, with 20% TFE resulted in significant aggregation as detected by filter trap assay, indicating that the E40K and T18S mutants more readily expose their hydrophobic surfaces and aggregate than WT (Figure 4). Also, at lower concentrations of TFE, not only do both E40K and T18S show greater signal on the filter trap assay than WT, but E40K shows the most signal at 0% TFE indicating that it is relatively more unstable than T18S. This increased aggregation signal correlates with its greater degree of aggregation in cell culture (Figure 5A).

FIGURE 4. Canine SOD1 mutants are prone to aggregation in vitro.

Filter trap assay of recombinant cSOD1 proteins exposed to increasing concentrations of TFE. The E40K and T18S mutants show heightened sensitivity to 20% TFE compared to WT, indicating an increased ability to aggregate.

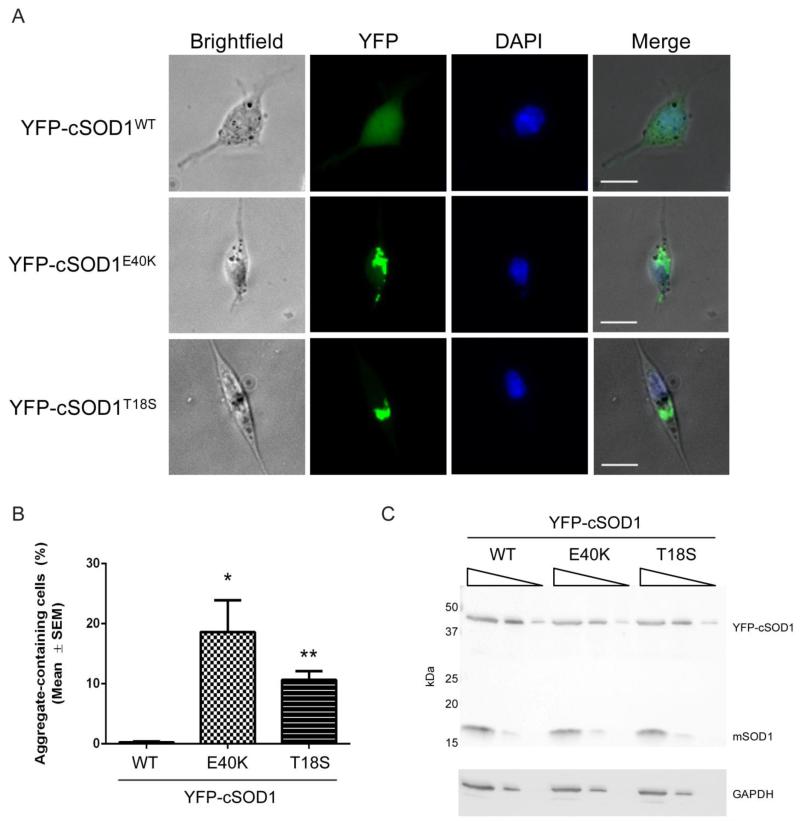

FIGURE 5. Canine SOD1 mutants aggregate in cell culture.

(A) NSC34 cells transiently transfected for 48 hours with 900 ng of YFP-tagged cSOD1 WT, E40K, or T18S. Scale bar = 20 μm. (B) Quantification of A. At least 120 cells were counted in three separate experiments. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01 (C) Western blot of transfected NSC34 cell lysates (17.6 μg initial protein with 1:5 serial dilutions) probed with α-SOD1 (FL154) or α-GAPDH antibodies. YFP-cSOD1 and the endogenous mouse SOD1 (mSOD1) at 17 kDa are indicated on the blot.

To visualize the degree of aggregation of cSOD1 mutants, we tagged WT, E40K, and T18S with an N-terminal YFP tag and transiently transfected each construct into NSC34 cells, an immortalized motor neuron-like cell line (Cashman et al., 1992). After 48 hours, similar expression levels resulted in significant aggregation in 10-20% of cells for both mutants, while the WT protein remained soluble (Figure 5). Data show that the degree of aggregation for the E40K mutant was significantly more than the T18S mutant, which reflects its increased aggregation as seen by filter trap assay. The aggregates closely resemble SOD1 aggregates for hSOD1 proteins in cell culture (Gomes et al., 2010).

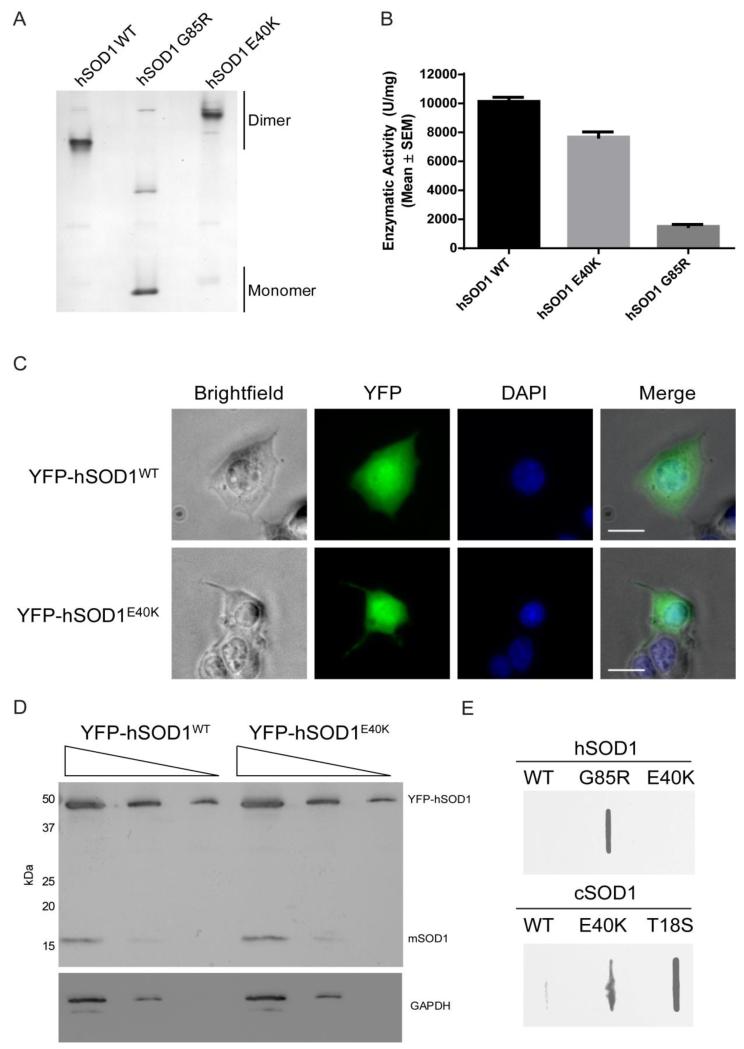

The E40K mutation in hSOD1 fails to recapitulate the aggregation seen in the canine mutant

Since human and canine SOD1 share 79.1% identity, and since >160 mutations have been described for the human protein, it was no surprise that the canine E40K mutation occurred at a residue shared with hSOD1. In fact, an older review of SOD1 mutants points out the existence of an E40G mutation, but no primary description exists (Turner and Talbot, 2008). To address any biochemical overlap between this mutation in humans and dogs, we created the E40K mutation in hSOD1 via site directed mutagenesis. As the location of this mutation in both human and canine SOD1 falls within one of the connecting loops and does not interfere with metal binding, we predicted that the human E40K mutant would, like its canine counterpart, be an enzymatically active dimer. A partially denaturing PAGE gel and dismutase activity confirm these predictions (Figure 6A, 6B). However, when we transiently transfected human SOD1 E40K into NSC34 cells, no aggregates were observed, even up to 72 hours after transfection (Figure 6C and data not shown). This is despite ample YFP-cSOD1 protein production in cells by Western blot (Figure 6D). To rule out any inhibitory effects that the YFP tag may have on aggregation, we transiently-transfected untagged hSOD1 WT, G85R, and E40K, as well as cSOD1 WT, E40K, and T18S, into NSC34 cells and looked for the presence of aggregates via a filter trap assay (Figure 6E). In agreement with previous observations with YFP-tagged SOD1 constructs, we found a significant aggregation signal from canine E40K and T18S and human G85R, but not human E40K. We subsequently created the hSOD1 E40G mutation to see if the lack of aggregation in human E40K was amino acid specific, but also found no aggregation in NSC34 or HEK293 cells (data not shown). Thus, despite the high sequence similarity between species, the aggregation propensity of the E40K mutation is unique to cSOD1 under the conditions and with the cell types studied here.

FIGURE 6. The human E40K mutation is a dismutase active dimer that fails to aggregate.

(A) Partially denaturing PAGE gel showing that hSOD1 E40K migrates as a dimer with a positive charge shift. (B) Dismutase assay of hSOD1 WT, E40K, and G85R mutations. No significant difference is seen between WT and E40K. (C) Representative images of NSC34 cells transiently transfection with 900 ng of YFP-tagged hSOD1 WT and E40K showing diffuse cytoplasmic and nuclear distribution with no aggregates. Scale bar = 20 μm (D) Western blot of transfected NSC34 cell lysates from C (1:5 serial dilutions) probed with α-SOD1 (FL154) or α-GAPDH antibodies. YFP-hSOD1 and the endogenous mouse SOD1 (mSOD1) at 17 kDa are indicated on the blot. (E) Filter trap assay of NSC34 cell lysates transiently transfected with human or canine SOD1 constructs lacking the N-terminal YFP tag confirm that hSOD1 E40K does not form aggregates.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The discovery that mutations in SOD1 are linked to canine DM opens many avenues for comparative studies between this disorder and human ALS, as well as a multitude of questions on the degree of similarity between these phylogenetically separated proteins. An important starting point for comparing the two disorders is understanding the biochemical characteristics of the only two known cSOD1 mutations linked to this disease as compared to hSOD1. Our results confirm that, like hSOD1 mutants, mutant cSOD1 forms detergent-insoluble aggregates in spinal cords of affected dogs that increase with disease severity. Further data show that both E40K and T18S mutations in cSOD1 are not loss of function mutations, but form enzymatically active dimers that are prone to aggregation in vitro. Finally, despite a high degree of sequence similarity to hSOD1, we show that the aggregation propensity of the conserved E40K mutation is unique to cSOD1.

One of the most striking differences between canine DM and human ALS is that, unlike the well documented toxic gain of function in dominantly-inherited SOD1-mediated human ALS, homozygosity at the SOD1 locus is frequently observed in most cases of canine DM (Awano et al., 2009; Wininger et al., 2011). Thus, unlike the heterozygous state found in the majority of ALS patients, a loss of function contributing to disease in these animals was a real possibility. In fact, SOD1 knock-out mice display mild age-related muscle denervation and degeneration that, depending on the genetic background, translate into impaired performance on motor tests (Flood et al., 1999; Kostrominova, 2010; Muller et al., 2006; Shefner et al., 1999). Therefore, we first needed to rule out SOD1 loss of function in these animals. As our data show that the canine E40K and T18S mutations form enzymatically active dimers, we are confident that the canine DM model reflects the same toxic gain of function phenotype described for hSOD1 mutants. However, if it is true that a DM phenotype is most common in the presence of two copies of mutant SOD1, and if the >160 mutations in hSOD1 foreshadow the possibility of additional mutations in cSOD1 that render it enzymatically inactive, then an overlapping DM and SOD1 knock-out phenotype in dogs with such mutation remains an interesting possibility.

In hSOD1, one common feature among all mutants is increased aggregation propensity in vitro and in vivo. This is accompanied by decreased protein stability as measured by differential scanning fluoroscopy, susceptibility of many, but not all, mutants to proteinase K digestion, and abnormal migration under reducing conditions when compared to the remarkably stable WT protein (Münch and Bertolotti, 2010; Ratovitski et al., 1999; Tiwari and Hayward, 2003). Our results with cSOD1 confirm that the E40K and T18S mutations are no exception. We consistently observed SOD1 aggregates in transiently-transfected NSC34 cells that, in our eyes, exceeded the degree of aggregation for many human SOD1 mutants. Coupled with its increased aggregation in the presence of TFE and the accumulation of detergent-insoluble SOD1 species in cases of canine DM, cSOD1 mirrors many of the properties of its human counterpart, and is predicted to recapitulate additional properties. However, the slight differences between the clinical presentations in canine DM and human ALS may reflect significant differences between the two proteins. For example, it has been shown that mutant hSOD1 aggregates possess prion-like properties in their ability to accelerate the misfolding and aggregation of additional SOD1 in vitro, as well as physically enter cells and cause the misfolding and aggregation of intracellular mutant and WT SOD1 (Chia et al., 2010; Grad et al., 2011; Munch et al., 2011). With SOD1 playing a role in canine DM, does this same mechanism hold true in dogs? One group elegantly elucidated the importance of the W32 residue in hSOD1 in maintaining species-specific cross-seeding of misfolded SOD1 (Grad et al., 2011) As cSOD1 lacks this critical residue, does this impact its ability to seed? These questions highlight the significance that canine DM offers as an additional tool to pursue disease mechanisms of SOD1.

Canine and human SOD1 share approximately 80% identity. While the T18S mutation occurs at a unique amino acid found only in cSOD1, the E40K mutation occurs at a conserved residue between canine and human SOD1. When we created the E40K mutation in hSOD1 to explore the similarities with the canine mutant, we showed that this mutation, like canine E40K, is a dismutase active dimer. However, we were surprised to find that mutating this residue in hSOD1 does not result in an aggregation phenotype despite the prevalent aggregation seen in its canine counterpart and despite the appearance of an hSOD1 E40G mutation in the SOD1 literature (Turner and Talbot, 2008). We also did not observe aggregation when we transiently transfected YFP-hSOD1 E40G into NSC34 cells (data not shown). The most recent edition of the online ALSod database (http://alsod.iop.kcl.ac.uk/, accessed February 22nd, 2013) no longer lists the hSOD1 E40G mutation, and no primary literature source exists, thus E40G may not represent a disease causing mutation in humans. As over 160 causative mutations spanning over 70 residues have been identified for hSOD1, the discovery of a mutation that causes aggregation in a species-specific manner is unique and raises interesting questions concerning the relationship between protein sequence, tertiary structure, and aggregation propensity. Perhaps hSOD1 contains a sufficiently different tertiary structure that ameliorates the instability conferred by E40K. Or perhaps the structure of cSOD1 renders mutations at this residue particularly unstable.

What are the implications of another animal model of ALS, and what are the advantages of the canine DM model as compared to existing SOD1 models? Canine DM is not a perfect model of human ALS (Table 1). So far, a majority of dogs homozygous for SOD1 mutations develop disease, although some heterozygous dogs do develop canine DM and show intermediate levels of SOD1 aggregates in motor neurons (Joan Coates, personal communication). Additionally, the motor neuron loss that is the hallmark of human ALS is not seen to the same degree histopathologically and DM also involves proprioceptive pathways (Table 1) (Awano et al., 2009; Coates et al., 2007; Coates and Wininger, 2010; Shelton et al., 2012). Despite these differences, canine DM offers a naturally occurring, non-artificial system in which to study SOD1 and ALS. This differs from many of the mouse and rat transgenic models created so far, many of which require hSOD1 overexpression to non-physiological levels (e.g. G93A). In contrast, dogs with canine DM develop disease late in life with physiological levels of mutant cSOD1, thus providing a better picture of the natural disease progression. Our results show that, at the biochemical level, canine and human SOD1 are remarkably similar. Both aggregate readily when mutated, both display decreased protein stability, and both contain mutants that are functionally indistinct from WT protein (Table 1). Thus, it is reasonable to assume that human and canine SOD1 cause disease via a similar mechanism. In elucidating biochemical similarities between human ALS and canine DM, this study expands the research toolkit for understanding ALS and opens the door for developing novel therapies for ALS.

TABLE 1.

Clinical, genetic, pathological, and biochemical differences between human ALS and canine DM.

| Clinical and Genetic |

Histopathology |

Biochemistry |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Onset | Inheritance | Proprioceptive involvement |

MN loss | SOD1 aggregates in spinal cord |

Detergent-insoluble SOD1 species in spinal cord |

Recombinant SOD1 aggregates |

SOD1 aggregates in cell culture |

|

|

|

||||||||

| SODALS | Limb, Bulbar | Autosomal Dominant | No | ++++ | Yes | Yesa | Yesb | Yesc |

| Canine DM | Lower Limb | Mostly Autosomal Recessive | Yes | + | Yes | Yes* | Yes* | Yes* |

This study

Highlights.

First characterization of two canine SOD1 mutants, E40K and T18S, in vitro

Spinal cords of affected dogs show detergent-insoluble SOD1 aggregates

Recombinant canine SOD1 mutants aggregate under mild denaturing conditions

Expression of canine SOD1 in cell culture confirms aggregation propensity

The conserved E40K mutation in human SOD1 does not aggregate

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Gary S. Johnson of the Animal Molecular Genetic Diseases Laboratory for genotyping and Dr. Martin L. Katz in assisting with kit preparations for tissue collections. This work was supported by K08NS074194, NIH/NINDS/AFAR (to TMM), R01NS078398 NINDS (to T.M.M), R21NS078242 NIH/NINDS (to JRC), and F31NS078818 NIH/NINDS (to MJC). Funding was also provided by AKC Canine Health Foundation Grants #821 and #1213A and ALS Association grant #6054.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; DM, degenerative myelopathy; GWAS, genome-wide association study; IPTG, isopropyl-β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside; SOD1, superoxide dismutase 1; TFE, trifluoroethanol.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Awano T, Johnson GS, Wade CM, Katz ML, Johnson GC, Taylor JF, Perloski M, Biagi T, Baranowska I, Long S, March PA, Olby NJ, Shelton GD, Khan S, O’Brien DP, Lindblad-Toh K, Coates JR. Genome-wide association analysis reveals a SOD1 mutation in canine degenerative myelopathy that resembles amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2794–2799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812297106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchelt DR, Lee MK, Slunt HS, Guarnieri M, Xu ZS, Wong PC, Brown RH, Jr., Price DL, Sisodia SS, Cleveland DW. Superoxide dismutase 1 with mutations linked to familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis possesses significant activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8292–8296. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruijn LI. Aggregation and Motor Neuron Toxicity of an ALS-Linked SOD1 Mutant Independent from Wild-Type SOD1. Science. 1998;281:1851–1854. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5384.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashman NR, Durham HD, Blusztajn JK, Oda K, Tabira T, Shaw IT, Dahrouge S, Antel JP. Neuroblastoma × spinal cord (NSC) hybrid cell lines resemble developing motor neurons. Dev Dyn. 1992;194:209–221. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001940306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia R, Tattum MH, Jones S, Collinge J, Fisher EM, Jackson GS. Superoxide dismutase 1 and tgSOD1 mouse spinal cord seed fibrils, suggesting a propagative cell death mechanism in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10627. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiti F, Stefani M, Taddei N, Ramponi G, Dobson CM. Rationalization of the effects of mutations on peptide and protein aggregation rates. Nature. 2003;424:805–808. doi: 10.1038/nature01891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates JR, March PA, Oglesbee M, Ruaux CG, Olby NJ, Berghaus RD, O’Brien DP, Keating JH, Johnson GS, Williams DA. Clinical characterization of a familial degenerative myelopathy in Pembroke Welsh Corgi dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21:1323–1331. doi: 10.1892/07-059.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coates JR, Wininger FA. Canine degenerative myelopathy. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2010;40:929–950. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng HX, Shi Y, Furukawa Y, Zhai H, Fu R, Liu E, Gorrie GH, Khan MS, Hung WY, Bigio EH, Lukas T, Dal Canto MC, O’Halloran TV, Siddique T. Conversion to the amyotrophic lateral sclerosis phenotype is associated with intermolecular linked insoluble aggregates of SOD1 in mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:7142–7147. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602046103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood DG, Reaume AG, Gruner JA, Hoffman EK, Hirsch JD, Lin YG, Dorfman KS, Scott RW. Hindlimb motor neurons require Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase for maintenance of neuromuscular junctions. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:663–672. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65162-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes C, Escrevente C, Costa J. Mutant superoxide dismutase 1 overexpression in NSC-34 cells: effect of trehalose on aggregation, TDP-43 localization and levels of co-expressed glycoproteins. Neurosci Lett. 2010;475:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grad LI, Guest WC, Yanai A, Pokrishevsky E, O’Neill MA, Gibbs E, Semenchenko V, Yousefi M, Wishart DS, Plotkin SS, Cashman NR. Intermolecular transmission of superoxide dismutase 1 misfolding in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16398–16403. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102645108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SL, Tolwani RJ, Varma S, Quignon P, Galibert F, Cork LC. Structure, chromosomal location, and analysis of the canine Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) gene. J Hered. 2002;93:119–124. doi: 10.1093/jhered/93.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan MC, Vucic S, Cheah BC, Turner MR, Eisen A, Hardiman O, Burrell JR, Zoing MC. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2011;377:942–955. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostrominova TY. Advanced age-related denervation and fiber-type grouping in skeletal muscle of SOD1 knockout mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:1582–1593. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto G, Stojanovic A, Holmberg CI, Kim S, Morimoto RI. Structural properties and neuronal toxicity of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis-associated Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase 1 aggregates. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:75–85. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller FL, Song W, Liu Y, Chaudhuri A, Pieke-Dahl S, Strong R, Huang TT, Epstein CJ, Roberts LJ, Csete M, Faulkner JA, Van Remmen H. Absence of CuZn superoxide dismutase leads to elevated oxidative stress and acceleration of age-dependent skeletal muscle atrophy. Free Radic Biol Med. (2nd) 2006;40:1993–2004. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Münch C, Bertolotti A. Exposure of Hydrophobic Surfaces Initiates Aggregation of Diverse ALS-Causing Superoxide Dismutase-1 Mutants. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2010;399:512–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munch C, O’Brien J, Bertolotti A. Prion-like propagation of mutant superoxide dismutase-1 misfolding in neuronal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3548–3553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017275108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudencio M, Durazo A, Whitelegge JP, Borchelt DR. Modulation of mutant superoxide dismutase 1 aggregation by co-expression of wild-type enzyme. J Neurochem. 2009a;108:1009–1018. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05839.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudencio M, Durazo A, Whitelegge JP, Borchelt DR. An examination of wild-type SOD1 in modulating the toxicity and aggregation of ALS-associated mutant SOD1. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:4774–4789. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudencio M, Hart PJ, Borchelt DR, Andersen PM. Variation in aggregation propensities among ALS-associated variants of SOD1: correlation to human disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2009b;18:3217–3226. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh T, Lyon AN, Pineda RH, Wang C, Janssen PM, Canan BD, Burghes AH, Beattie CE. A genetic model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in zebrafish displays phenotypic hallmarks of motoneuron disease. Dis Model Mech. 2010;3:652–662. doi: 10.1242/dmm.005538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin KS, Starkey M, Lunec J, Gerrand CH, Murphy S, Biswas S. Of dogs and men: comparative biology as a tool for the discovery of novel biomarkers and drug development targets in osteosarcoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:327–333. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratovitski T, Corson LB, Strain J, Wong P, Cleveland DW, Culotta VC, Borchelt DR. Variation in the biochemical/biophysical properties of mutant superoxide dismutase 1 enzymes and the rate of disease progression in familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis kindreds. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:1451–1460. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.8.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ripps ME, Huntley GW, Hof PR, Morrison JH, Gordon JW. Transgenic mice expressing an altered murine superoxide dismutase gene provide an animal model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:689–693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.3.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen DR, Siddique T, Patterson D, Figlewicz DA, Sapp P, Hentati A, Donaldson D, Goto J, O’Regan JP, Deng HX, et al. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature. 1993;362:59–62. doi: 10.1038/362059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowell JL, McCarthy DO, Alvarez CE. Dog models of naturally occurring cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:380–388. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shefner JM, Reaume AG, Flood DG, Scott RW, Kowall NW, Ferrante RJ, Siwek DF, Upton-Rice M, Brown RH., Jr. Mice lacking cytosolic copper/zinc superoxide dismutase display a distinctive motor axonopathy. Neurology. 1999;53:1239–1246. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.6.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton GD, Johnson GC, O’Brien DP, Katz ML, Pesayco JP, Chang, B , , Mizisin AP, Coates JR. Degenerative myelopathy associated with a missense mutation in the superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) gene progresses to peripheral neuropathy in Pembroke Welsh Corgis and Boxers. J Neurol Sci. 2012;318:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari A, Hayward LJ. Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mutants of copper/zinc superoxide dismutase are susceptible to disulfide reduction. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5984–5992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210419200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner BJ, Talbot K. Transgenics, toxicity and therapeutics in rodent models of mutant SOD1-mediated familial ALS. Prog Neurobiol. 2008;85:94–134. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Slunt H, Gonzales V, Fromholt D, Coonfield M, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Borchelt DR. Copper-binding-site-null SOD1 causes ALS in transgenic mice: aggregates of non-native SOD1 delineate a common feature. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2753–2764. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wininger FA, Zeng R, Johnson GS, Katz ML, Johnson GC, Bush WW, Jarboe JM, Coates JR. Degenerative myelopathy in a Bernese Mountain Dog with a novel SOD1 missense mutation. J Vet Intern Med. 2011;25:1166–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.0760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zetterstrom P, Stewart HG, Bergemalm D, Jonsson PA, Graffmo KS, Andersen PM, Brannstrom T, Oliveberg M, Marklund SL. Soluble misfolded subfractions of mutant superoxide dismutase-1s are enriched in spinal cords throughout life in murine ALS models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:14157–14162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700477104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]