Abstract

As a single DNA molecule is positively supercoiled under constant tension, its extension initially increases due to a negative twist-stretch coupling1, 2. The subsequent attainment of an extension maximum has previously been assumed to be indicative of the onset of a phase transition from B- to scP-DNA2. Here we show that an extension maximum in fact does not coincide with the onset of a phase transition. This transition is evidenced by a direct observation of a torque plateau using an angular optical trap. Instead we find that the shape of the extension curve can be well explained with a theory by John Marko3 that incorporates both DNA twist-stretch coupling and bending fluctuations. This theory also provides a more accurate method of determining the value of the twist-stretch coupling modulus, which has possibly been underestimated in previous studies that did not take into consideration the bending fluctuations2. Our study demonstrates the importance of torque detection in the correct identification of phase transitions as well as the contribution of the twist-stretch coupling and bending fluctuations to DNA extension.

Introduction

During various cellular processes DNA molecules often experience moderate stress and torque. These perturbations may be generated by motor enzymes and provide a mechanism for the regulation of DNA replication, DNA repair, transcription, and DNA recombination4–8. Therefore, understanding tensile and torsional responses of DNA is essential to understanding how mechanical perturbations may regulate cellular activities.

A single DNA molecule can be extended under force and rotated under torque, as has been investigated using optical and magnetic tweezers and micropipettes during the past two decades9–16. In particular, some of these studies revealed that the tensile and torsional responses of DNA are coupled. Initial analyses suggested that DNA undertwists when extended, indicating a positive twist-stretch coupling coefficient3, 17. More recent studies by Gore et al.1 and Lionnet et al.2 using magnetic tweezers, as well as our own work using angular optical trapping15 provide compelling evidence to the contrary: DNA overtwists when extended and, conversely, DNA extends when overtwisted. However, there remains some ambiguity in identifying the signatures of twist-stretch coupling in the extension curves when the DNA was overtwisted under constant force. While Lionnet et al.2 interpreted a peak in this curve to be indicative of the onset of a phase transition from B- to supercoiled P- (scP-) DNA, our earlier work indicated that the peak of the curve and the phase transition did not coincide at the particular force examined15. In general, there was a lack of understanding of the nature of the extension peak location and its relation to both twist-stretch coupling and phase transitions.

The goals of this work are to differentiate between the signatures of twist-stretch coupling and those of phase transitions, and to provide an explanation for the existence of the maximum in the extension signal. To this end, we carried out DNA torsional experiments using an angular optical trap in conjunction with nanofabricated quartz cylinders so that torque, angle, force, and extension of a DNA molecule were simultaneously measured during DNA supercoiling, using previously described methods15, 16. An important advantage of this approach is the direct detection of the torque signal, allowing unambiguous identification of the onset of the phase transition where torque plateaus.

Experimental

Materials

The DNA template used in this study was constructed using previously described protocols16. In brief, a 4218-bp piece of DNA was ligated at one end to a short (60-bp) oligonucleotide labeled with multiple digoxygenin (dig) tags and at the other end to an oligonucleotide of the same length labeled with multiple biotin tags.

Experimental setup

The experimental configurations and procedures were similar to those described previously15, 16. In brief, prior to a measurement, DNA molecules were torsionally constrained at one end to streptavidin-coated nanofabricated quartz cylinders15 and at the other end to an anti-dig coated coverslip. All experiments were performed in phosphate-buffered saline (157 mM Na+, 4 mM K+, 12 mM PO43−, 140 mM Cl−, pH=7.4) at 23±1 °C. The experiment began with a torsion-free DNA molecule which was held under constant tension. The DNA was first slightly undertwisted and then overwound via a steady rotation of the input laser polarization at 5 Hz, so as to explore a range of DNA supercoiling. During this time, torque, angular orientation, position, and force of the cylinder as well as the location of the coverglass were simultaneously recorded. The torque exerted on the DNA was measured from the torque exerted on the cylinder by the optical trap after subtracting the viscous drag torque of the rotating cylinder.

Results and discussion

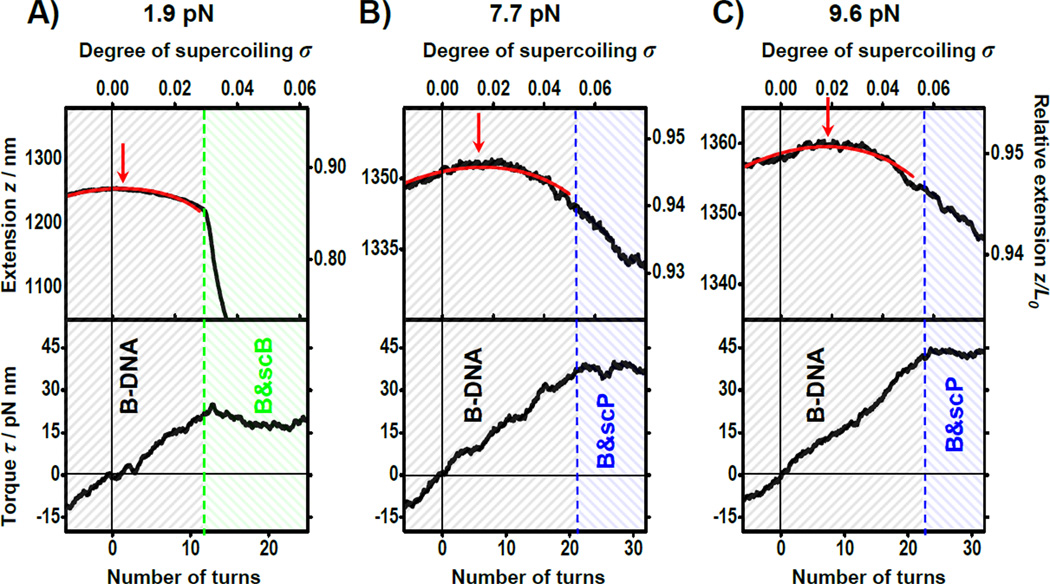

Figure 1 shows representative single traces of extension and the corresponding torque as a function of number of turns added to the DNA at three different applied forces (1.9, 7.7, and 9.6 pN). The number of turns was also converted to the degree of supercoiling σ, defined as the number of turns added to dsDNA divided by the number of naturally occurring helical turns in the given dsDNA. The DNA extension is also shown as the relative extension, defined as the extension normalized to the contour length of DNA template in its B-form.

Figure 1.

Examples of extension and torque versus turn number during DNA supercoiling. DNA molecules of 4.2 kbp in length were wound at 5 Hz under constant forces: A) 1.9 pN; B) 7.7 pN; C) 9.6 pN. Data were collected at 2 kHz and averaged with a sliding box window of 2.0 s for torque and 0.2 s for extension. The torque signal had more Brownian noise relative to signal and was subjected to more filtering. Red curves are fits to Equation (2) for B-DNA. Extension maxima are indicated with red arrows. A plateau in the torque reflects a phase transition and the onset of each transition is indicated by a dashed line.

Some overall features of these data are summarized below. At the beginning of each trace (σ ~ −0.02) DNA was in its B-form. As the DNA was twisted, torque increased linearly while extension remained approximately constant. At lower forces (< 6 pN) this continued until the DNA buckled to form a plectoneme, evidenced by a sudden decrease in extension and a concurrent plateau in torque, whose value was force-dependent16. Under this low force range, the signatures for the onset of the buckling transition may be recognized in either extension or torque. At higher forces we used (6 pN < F < 10 pN), as the molecule was overtwisted, DNA underwent a scP-DNA transition instead, as previously observed by Allemand et al.13 The onset of this transition was only evidenced by a sudden torque plateau around 40 pN nm14, 15. These phase transitions may be thought of as first-order phase transitions since two separate phases may coexist and can be transformed from one to another by simply changing the twist in the DNA18. Because there were no concurrent distinct features in the extension signal, the ability to monitor torque signal was essential in unambiguously locating the onset of this transition. In addition, the buckling torque showed a strong force-dependence as previously observed16; whereas the scP transition torque showed little force-dependence.

Several features relevant to twist-stretch coupling were also immediately evident. First, near σ = 0, the extension curve had a small but positive slope, which implied a negative twist-stretch coupling coefficient, i.e., DNA was extended when overtwisted. This observation was in accordance with previous studies1, 2, 15. Second, upon overtwisting, extension reached a maximum (indicated by an arrow in Fig. 1) at σz_max, as has also been previously observed2, 15. In addition, as the force increased, σz_max increased while the magnitude in the curvature of the extension at σz_max gradually decreased. Third, the location of the extension maximum σz_max clearly did not coincide with the onset of the phase transition (indicated by a dashed line on the right) where torque began to plateau. This was the case for the range of forces we examined. Therefore the location of the maximum is not indicative of an onset of a phase transition, contrary to what has been previously reported with the magnetic tweezers experiments, where the lack of torque signal might have complicated the interpretation of the results2.

To understand the nature of the extension signal for the B-form DNA, we performed a detailed analysis of both the extension and torque signals to gain insights in the twist-stretch coupling coefficient and the location of the extension maximum. We followed the analysis developed by Marko3. This theory also takes into account the contribution from bending fluctuations to DNA extension, using a treatment similar to that of Moroz and Nelson17. For a DNA molecule held under constant σ and force F, the free energy G includes contributions from bending, stretching, twisting, and twist-stretch coupling, and can be expressed as:

| (1) |

where Lp is the bending persistence length, K0 the stretch modulus, C0 the twist persistence length, g the twist-stretch coupling modulus (unitless), kBT the thermal energy, L0 the contour length, and ω0 = 2π/3.57 nm−1 the natural twist rate. This theory predicts DNA extension z as a function of σ and applied force F:

| (2) |

We used Equation (1) to obtain a prediction of torque τ as a function of σ and applied force F:

| (3) |

Thus, Equations (2) and (3) form a complete set of relations that fully describe force, extension, torque, and twist for a B-form DNA.

Below, we will focus on the analysis of the extension signal. Equation (2) contains several terms and its last term is due to the contribution of DNA bending fluctuations in the presence of the twist-stretch coupling. We found that Equation (2) predicts the existence of a maximum in the extension curve, reflecting an interplay between twist-stretch coupling and bending fluctuations. In the absence of any twist-stretch coupling, the maximum is centrally located, i.e., if g = 0, σz_max = 0. Twist-stretch coupling shifts the location of the maximum away from the center (Supplementary Materials). If g > 0, then σz_max < 0; and if g < 0, then σz_max > 0. The absolute value of σz_max increases with an increase in force.

Notice that if bending fluctuations are neglected, Equation (2) is then simplified to:

| (4) |

In contrast to Equation (2), Equation (4) predicts a linear relation between extension and the degree of supercoiling: if g > 0, then slope < 0 ; and if g < 0, then slope > 0 It does not predict a maximum in the extension curve.

We performed a fit of Equation (2) to our extension data for the B-form DNA with g as the only fit parameter. Other parameters were taken from previous measurements obtained under similar experimental conditions: K0 = 1200 pN9, 11, C0 = 100 nm14, 16, and Lp = 43 nm9, 11, 16. Our data were well fit by Equation (2) and some examples are shown in Figure 1 (red). In particular, the experimental observations that σz_max > 0 and increases with increasing force were indicative of a negative value for the twist-stretch coupling modulus g. Figure 2A shows g values obtained from the fits under various forces. Over the force range examined, g was essentially independent of the force: g = −21±1 (mean ± sem, N = 41). The g value is sensitive to the value used for C. For example, a ±10% uncertainty in C will result in a ±15% uncertainty in g.

Figure 2.

A) Measurement of the twist-stretch coupling modulus g. For each force, the twist-stretch coupling modulus was determined using Equation (2) from 7–11 traces of data. The mean of the modulus g is shown as the solid horizontal line. For comparison, the magnitude of g would have been underestimated by ~ 20% if Equation (3) were to be used instead (dashed line). B) Summary of the values of the twist-stretch coupling modulus obtained in recent single-molecule experiments. Considerations pertaining to bending fluctuations are specifically indicated.

If Equation (4) is used to obtain a g value instead, the magnitude of g is underestimated by ~ 20% over the range of forces examined (dashed line in Figure 2A). This difference does not vanish even with an increase in force, since the geometric coupling between bending and writhe fluctuations leads to a decrease in extension3. Interestingly, Lionnet et al.2 used Equation (4) to fit their extension data and obtained g = −16 ± 7 (mean ± sd, N > 36), whose magnitude is ~ 20% lower than our measured value. On the other hand, Gore et al.1 made a measurement of twist angle as a function of extension change when the DNA was not torsionally constrained and obtained g = −22±5 (mean ± sem, N = 4), more in accord with our measured value. In the analysis by Gore et al.1, the bending fluctuations were also neglected resulting in a similar linear approximation. Thus one might expect that the magnitude of g was similarly underestimated. Careful analysis using Equations (2) and (4) reveals that this effect was almost completely canceled by another linear approximation made to convert force to extension change. Taking together all these results (summarized in Fig. 2B), the twist-stretch coupling modulus g should be about − 21.

The extension maximum, however, can only be explained using Equation (2) and not Equation (4). Figure 3 plots σz_max obtained as a function of force. For comparison, we also plotted the critical σc values for phase transitions to plectoneme (scB-) or scP-DNA. As this figure indicates, when DNA is positively supercoiled under moderate forces (2 pN < F < 20 pN), the DNA extension reaches a maximum long before DNA buckling or a transition to scP-DNA. At even higher forces (F > 20 pN), the scP-DNA transition is reached before the extension reaches a maximum. This figure clearly indicates that σz_max and σc do not coincide, except at ~ 20 pN. Therefore, the maximum in the extension in general is not indicative of a phase transition, in contrast to the interpretation of Lionnet et al.2

Figure 3.

The degree of supercoiling at extension maximum σz_max and at the onsets of phase transitions. The measured values of σz_max (red circles) are plotted together with σz_max calculated using the mean value of g from Fig. 2 (red line). For comparison, also shown are the measured degree of supercoiling at the buckling transition and its fit using a Marko theory20 (green), as well as the measured degree of supercoiling at the onset to the scP transition with a constant fit (blue).

Twist-stretch coupling should also alter the torque signal. We found that consideration of the twist-stretch coupling as in Equation (3) will lower the expected torque value at most by ~ 1 pN nm (Supplementary Materials). This is below the uncertainty of our experimental determination of torque.

The analysis described in this work may not be valid at forces significantly higher than those used in the current work. In the absence of torsional constraints, Equation (3) predicts a monotonic increase in overtwisting angle with an increase in force. However, Gore et al.1 found that the twist angle starts to decrease with force above ~ 30 pN.

It is also worth mentioning that we do not consider sequence-dependent effects on twist-stretch coupling or phase transitions here. Prior simulation work 2, 19 suggests that DNA sequence may modulate the twist-stretch coupling. Future experiments with more refined measurements may help verify this prediction.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Wang lab for critical reading of the manuscript, S. Forth for help with the angular trap instrument and DNA template preparations, and T. Lionnet, V. Croquette, and D. Bensimon for helpful comments. M.D.W. wishes to acknowledge support from NSF grant (MCB-0820293), NIH grant (R01 GM059849), and the Cornell Nanobiotechnology Center.

References

- 1.Gore J, Bryant Z, Nollmann M, Le MU, Cozzarelli NR, Bustamante C. Nature. 2006;442:836–839. doi: 10.1038/nature04974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lionnet T, Joubaud S, Lavery R, Bensimon D, Croquette V. Phys Rev Lett. 2006;96:178102. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.178102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marko JF. Physical Review E. 1998;57:2134–2149. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liu LF, Wang JC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:7024–7027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.20.7024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Travers AA, Thompson JM. Philos Transact A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2004;362:1265–1279. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2004.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koster DA, Croquette V, Dekker C, Shuman S, Dekker NH. Nature. 2005;434:671–674. doi: 10.1038/nature03395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cozzarelli NR, Cost GJ, Nollmann M, Viard T, Stray JE. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:580–588. doi: 10.1038/nrm1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia HG, Grayson P, Han L, Inamdar M, Kondev J, Nelson PC, Phillips R, Widom J, Wiggins PA. Biopolymers. 2007;85:115–130. doi: 10.1002/bip.20627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith SB, Cui Y, Bustamante C. Science. 1996;271:795–799. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strick TR, Allemand JF, Bensimon D, Bensimon A, Croquette V. Science. 1996;271:1835–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5257.1835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang MD, Yin H, Landick R, Gelles J, Block SM. Biophys J. 1997;72:1335–1346. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78780-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strick TR, Allemand JF, Bensimon D, Croquette V. Biophys J. 1998;74:2016–2028. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77908-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allemand JF, Bensimon D, Lavery R, Croquette V. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14152–14157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bryant Z, Stone MD, Gore J, Smith SB, Cozzarelli NR, Bustamante C. Nature. 2003;424:338–341. doi: 10.1038/nature01810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deufel C, Forth S, Simmons CR, Dejgosha S, Wang MD. Nat Methods. 2007;4:223–225. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forth S, Deufel C, Sheinin MY, Daniels B, Sethna JP, Wang MD. Phys Rev Lett. 2008;100:148301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.148301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moroz JD, Nelson P. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:14418–14422. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marko JF, Siggia ED. Physical Review E. 1995;52:2912–2938. doi: 10.1103/physreve.52.2912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lionnet T, Lankas F. Biophys J. 2007;92:L30–L32. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.099572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marko JF. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2007;76:021926. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.76.021926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.