Abstract

Background:

Cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum II (CDDP)) is an effective drug in cancer therapy to treat solid tumors. However, the drug is accompanied by nephrotoxicity. Previous reports indicated that estrogen has no protective role against CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity, but the role of phytoestrogen as an estrogenic agent in plants is not determined yet. The major composition of fennel essential oil (FEO) is trans-anethole that has estrogenic activity; so, we used FEO as a phytoestrogen source against CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty-four ovariectomized Wistar rats were divided into seven groups. Groups 1-3 received different doses of FEO (250, 500, and 1000 mg/kg/day, respectively) for 10 days. Group 4 received saline for 10 days plus single dose of CDDP (7 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (ip)) at day 3. Groups 5-7 received FEO similar to groups 1-3, respectively; plus a single dose of CDDP (7 mg/kg, ip) on day 3. On day 10, the animals were sacrificed for histopathological studies.

Results:

The serum levels of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine (Cr), kidney tissue damage score (KTDS), and kidney weight (KW) and body weight changes in CDDP-treated groups increased significantly (P < 0.05). FEO did not reduce the levels of BUN and Cr, KTDS, and KW and body weight changes. Also, the serum and tissue levels of nitrite were not altered significantly by FEO.

Conclusion:

FEO, as a source of phytoestrogen, did not induce kidney damage. In addition, FEO similar to estrogen was not a nephroprotectant agent against CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity.

Keywords: Cisplatin, fennel essential oil, nephrotoxicity, ovariectomized rats

INTRODUCTION

Cisplatin (cis-diamminedichloroplatinum II (CDDP)) is a chemotherapy drug widely used in clinic for treatment of solid tumors. One of the most important and common side effects of CDDP is nephrotoxicity.[1,2,3,4] The pathogenesis of CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity includes oxidative stress, inflammation, and necrosis in proximal tubule.[2,5] Many agents have been suggested to protect the kidney against CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity; including erythropoietin, vitamins E and C, L-arginine, N-acetylcysteine, and angiotensin receptor blocker-losartan.[5,6,7,8,9,10,11] It is also reported that CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity is gender-related[6] and pharmacological doses of estrogen could abolish the nephroprotectant effect of some antioxidants.[12] Although estrogen is well-known as a cardiovascular protectant in women before menopause, it is not nephroprotectant in CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity.[12,13] So, one question is raised here; whether phytoestrogen response to kidney toxicity is similar to estradiol. Genistein, a phytoestrogen source was used to prevent CDDP-induced renal injury in male rats, and decrease in inflammation and oxidative stress was reported.[5]

Phytoestrogens are estrogenic agents found in plants.[14,15,16,17,18] These agents may reduce the development of renal diseases.[17] Phytoestrogens also have estrogenic activity due to their structural resemblance to diethylstilbestrol, a synthetic estrogen.[19] Foeniculum vulgare Mill. (fennel) is an aromatic plant that is used in fresh, juice, or dried forms. It has been widely used as a flavoring agent in many dishes and salads.[19,20,21] Additionally, this plant have been used for treatment of some diseases such as dyspepsia, bronchitis, chronic cough, dysmenorrhea,[21] and also has been suggested to increase milk and libido in women.[20,22,23]

The major composition of fennel essential oil (FEO) is trans-anethole, fenchone, and limonene.[20] Among them, trans-anethole is the most important item, which has antispermatogenic effect and decreases sperm concentration in epidermis of male rats.[24] It is well-documented that trans-anethole has estrogenic activity and is a well-known phytoestrogen.[19,20,21,25]

Previously, we reported that estrogen itself is a risk factor to promote CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity in female,[12] however the role of phytoestrogen was not reported yet, and therefore in this study we investigate the protective effect of FEO on CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity in ovariectomized rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fifty-four adult female Wistar rats (weighting 183.5 ± 1.4 g) were used in this study. The animals were housed at the room temperature of 23-25°C. The rats had free access to water and chow. All procedures were approved by the Ethical Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Essential oil preparation

Foeniculum vulgare essential oil was kindly gifted from the Barij Essence Pharmaceutical Company, Mashhad Ardehal, Iran, in 2008.

Essential oil analysis

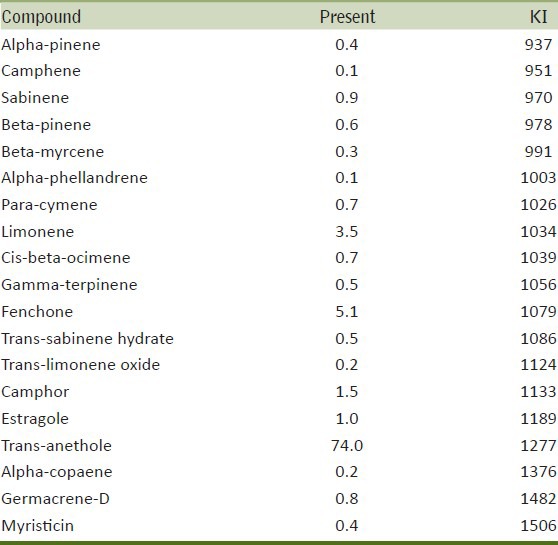

The gas chromatography (GC)/mass spectrophotometry (MS) analysis was performed on an Agilent 5975C Mass selective detector coupled with a Hewlett Packard 6890 gas chromatography equipped with a HP-5MS capillary column. The oven temperature was programmed from 60 to 280°C at the rate of 4°C/min. Helium was used as the carrier gas at the flow rate of 2 mL/min. The injector and detector temperature was 280°C. The MS operating parameters were: Ionization voltage 70 eV, ion source temperature 200°C. Identification of the natural constituents of the oil was based on retention indices relative to n-alkanes and computer matching with the WILEY 275.L library, as well as by comparison of the fragmentation patterns of mass spectra with those reported in the literature [Table 1].[20,25,26]

Table 1.

The list of the natural constituents of F. vulgare essential oil

Drug

CDDP (code P4394) was provided from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Experimental protocol

The rats were ovariectomized as described previously.[3] After 5 days of recovery, the animals were randomly divided into seven experimental groups.

Groups 1-3 were considered as the negative control groups (n = 10 for each group), received 250, 500, and 1000 mg/kg/day FEO intraperitoneally (ip) for 10 days.

Group 4 (n = 4), as the positive control groups received saline for 10 days plus a single dose of CDDP (7 mg/kg, ip) on day 3.

Groups 5-7 received 250 (group 5, n = 6), 500 (group 6, n = 7), and 1000 mg/kg/day (group 7, n = 7) FEO for 10 days, plus a single dose of CDDP (7 mg/kg, ip) on day 3. The groups were considered as the cases groups.

The weight of animals was recorded daily. After 10 days of experiment, the rats were sacrificed after blood samples were taken. The serum samples were collected and stored at −20°C until measurement. The kidney and uterus were removed immediately and weighed. The left kidney was fixed in 10% formalin for pathological investigation, and the right kidney was homogenated in 2 ml of saline; centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 2 min; and the supernatant was collected for measurement.

Measurements

The levels of serum creatinine (Cr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) were measured using diagnostic kits (Pars Azmoon Co., Tehran, Iran). The serum and renal levels of nitrite (NO stable metabolite) were determined by a commercial kit (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA). The renal and serum levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) were measured by the manual method. Briefly, 0.5 mL of the sample was mixed by 1 mL of 10% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). The mixture was centrifuged at 2,000 g for 10 min; and 500 μl of the supernatant was added to 500 μl of 0.67% thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and was incubated in the boiling water for 10 min. After cooling, the absorbance was read at the wavelength of 532 nm.

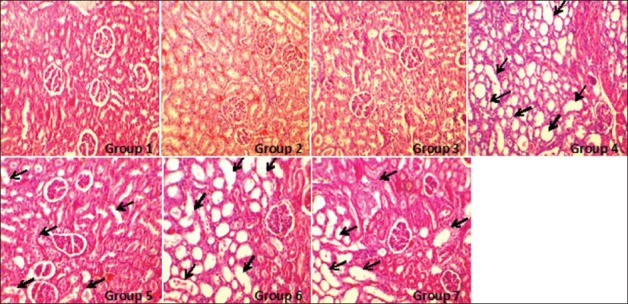

Histopathological procedures

For histopathological investigation, the excised left kidney was embedded in paraffin and then stained by hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) to assay the tubular damage. The tubular damage was evaluated by an expert pathologist who was blind to the study with regard to tubular dilation and simplification, tubular cells swelling and necrosis, tubular casts, and intraluminal cell debris with inflammatory cells infiltration. According to intensity of tubular injuries, the kidney tissue damage score (KTDS) was assigned in the range of 1-4 by pathologist as blind, while zero was assigned to normal tissue without damage.

Statistical analysis

Data was expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Comparison of the groups with regard to body weight was performed using repeated measure analysis. The levels of BUN, Cr, MDA, and nitrite; and kidney weight (KW) were analyzed by the one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey's test. The tissue damage score was compared by the Kruskal-Wallis or Mann-Whitney tests.

RESULTS

Effect of CDDP

Serum levels of BUN, Cr, and serum and tissue nitrite levels

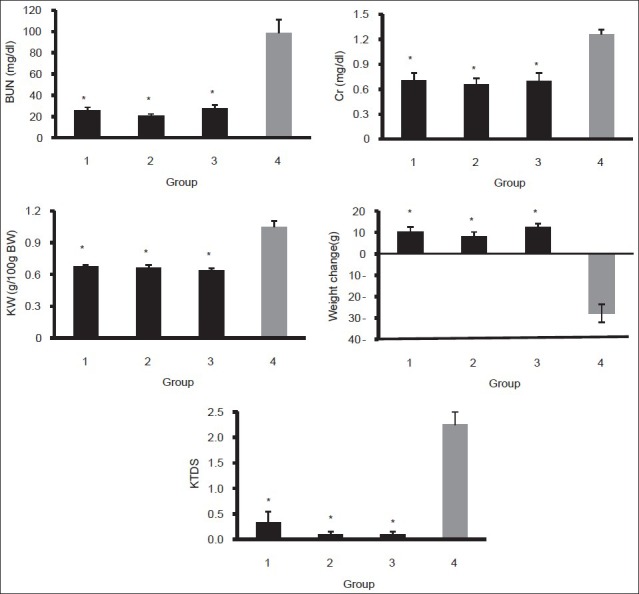

The CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity was approved by comparison of BUN and Cr levels between the positive control group (group 4) and the negative control groups (groups 1, 2, and 3). The data indicated that the levels of BUN and Cr increased significantly in the positive control group (P < 0.05) [Figure 1]. The negative control groups were not significantly different in the BUN and Cr levels. Although the serum level of nitrite was not significantly different between groups 1-4, the kidney nitrite levels in negative control groups (FEO-alone treated groups) increased, and this increase was statistically significant in groups 1 and 3, when compared with the positive control group (P < 0.05) [Table 2].

Figure 1.

Serum levels of BUN and Cr; kidney weight; weight change and kidney tissue damage score in the positive (group 4) and negative control (groups 1, 2, and 3) groups. The star indicates significant difference from positive control group (P < 0.05)

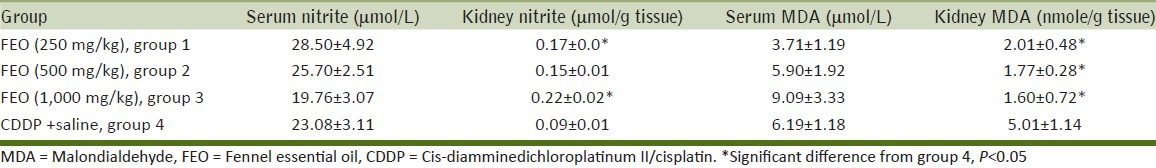

Table 2.

Levels of nitrite and MDA in serum and kidney in positive and negative control groups

Serum and tissue levels of MDA, body weight changes, KW, and KTDS

CDDP significantly increased the kidney tissue MDA level (P < 0.05), and such finding was not observed in the serum level of MDA [Table 2]. Both KW and KTDS increased significantly in the CDDP-alone treated (positive control) group compared with the negative control groups (P < 0.05) [Figure 1]. These findings verify CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity. No body weight loss was detected in the FEO-alone treated (negative control) group, but significant weight loss was observed in the CDDP-alone treated group (P < 0.05) [Figure 1].

Effect of FEO on CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity

Serum levels of BUN, Cr, and the serum and tissue nitrite levels

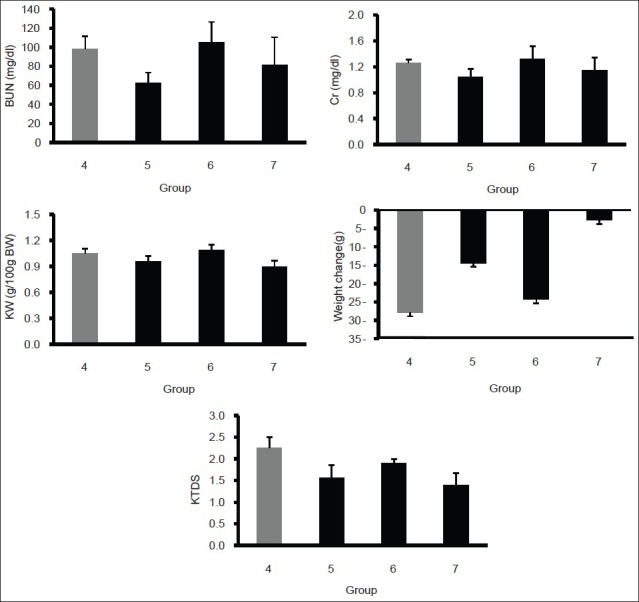

To determine the effect of FEO on nephrotoxicity induced by CDDP, all groups treated by the combination of CDDP and different doses of FEO were compared with the CDDP-alone treated group. The data obtained showed that FEO could not reduce the levels of BUN and Cr [Figure 2]. The results also indicated that the serum and tissue levels of nitrite did not significantly change by FEO [Table 3].

Figure 2.

Serum levels of BUN and Cr; KW; weight change; and KTDS in positive control (group 4) and case (groups 5, 6, and 7) groups. The star indicates significant difference from positive control group (P < 0.05)

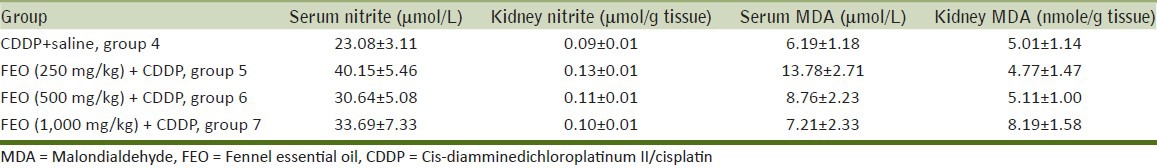

Table 3.

Serum and kidney levels of nitrite and MDA in positive control and case groups

Serum and tissue levels of MDA, body weight changes, KW, and KTDS

The CDDP-received groups were not significantly different in serum and tissue levels of MDA. The KW and KTDS increased, but the increase was not statistically significant between the positive control group (group 4) and the case groups (groups 5, 6, and 7). The weight loss in CDDP-alone treated group was more than that in the groups that received FEO plus CDDP. However, the weight loss in all groups that received CDDP was not statistically significant [Figures 2 and 3].

Figure 3.

The images of kidney tissues (magnification, ×100) in all groups of experiments. The damage was detected by tubular dilation and simplification, tubular cells swelling and necrosis, tubular casts, and intraluminal cell debris with inflammatory cells infiltration. More kidney tissue damage was observed in groups 4-7 (with no significant difference between the groups) while no damage was detected in the groups 1-3

DISCUSSION

The main objective of this study was to determine the effect of FEO on CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity in ovariectomized rats. Our results indicate that CDDP increased the serum levels of BUN, Cr, and MDA. The KTDS and KW were also increased, and weight loss was observed in the presence of CDDP. This finding is in agreement with the results of other studies.[3,6,8,27,28,29]

CDDP resulted in significant tubular damage[28] and oxidative stress involved in kidney damage after CDDP administration.[30] The nephrotoxic effect of CDDP is related to its uptake by proximal tubular cells.[31,32] Some other studies documented that a single injection of CDDP at doses of 5-10 mg/kg in rats caused a marked reduction in the glomerular filtration rate and increase in serum levels of BUN and Cr; thus, indicating induction of acute kidney injury.[33,34,35,36] The weight loss in animals is caused by CDDP-induced gastrointestinal disturbances.[6,37,38,39] We observed that KW increased by CDDP, possibly due to tubular damages and changes in glomerular filtration rate,[40] which accumulates water and salt in the kidney tissue. CDDP induced free radical protection and lipid peroxidation in tubular cells that is probably responsible for the oxidative renal damage. Lipid peroxidation was monitored by measuring MDA, which results from free radical damage to the membrane components of the cells.[28,29]

According to our results, FEO has not protective role against nephrotoxicity. The major component of FEO is trans-anethole that has estrogenic activity.[20,21,41] It seems that tarns-anethole have the potential to interact with estrogen receptors.[20] Estrogen can improve the potency of CDDP[42] and promote the kidney damage.[12,13] Furthermore, estrogen has vasodilatory effect and more CDDP may be transported to the kidney, and CDDP accumulates in the kidney tissue via basolateral membranes and destroys mitochondrial DNA, and finally causes tubular damage.[40,43,44] Moreover, studies showed that estrogen increases oxidative stress in kidney[12,45] and promotes kidney toxicity in proximal tubules.[6,12] Therefore, it seems that the effect of FEO on CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity is very similar to synthetic estrogen which is not protecting CDDP induced kidney toxicity, possibly different mechanism was involved. CDDP enhances the level of renal inducible NO synthase (iNOS) in response to oxidative stress;[28,45,46] but in our previous studies, CDDP did not cause any changes in nitrite levels.[12,13] FEO is a source of NO, especially iNOS.[47] So, increase in the NO kidney level in negative control groups is probably caused by NO. But, the level of kidney NO decreased when CDDP was injected. Therefore, positive control group and case groups were not significantly different in this regard. This result is probably due to the effect of CDDP on reduction of endothelial NO[12] and it possibly prevents the protective effect of FEO on CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity. On the other hand, studies have shown that the FEO effect is dose dependent;[20] so, probably doses used in the current study were not effective doses.

CONCLUSIONS

It seems that FEO, as a source of phytoestrogen,[20,41,48] did not induce nephrotoxicity. In addition, FEO was not a nephroprotectant agent against CDDP-induced nephrotoxicity.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. The authors wish to thank Barij Essence Pharmaceutical Company for providing the essential oil.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This research was supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rybak LP, Mukherjea D, Jajoo S, Ramkumar V. Cisplatin ototoxicity and protection: Clinical and experimental studies. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2009;219:177–86. doi: 10.1620/tjem.219.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller RP, Tadagavadi RK, Ramesh G, Reeves WB. Mechanisms of cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Toxins (Basel) 2010;2:2490–518. doi: 10.3390/toxins2112490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nematbakhsh M, Pezeshki Z, Eshraghi-Jazi F, Ashrafi F, Nasri H, Talebi A, et al. Vitamin E, Vitamin C, or losartan is not nephroprotectant against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in presence of estrogen in ovariectomized rat model. Int J Nephrol. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/284896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Townsend DM, Deng M, Zhang L, Lapus MG, Hanigan MH. Metabolism of cisplatin to a nephrotoxin in proximal tubule cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1–10. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000042803.28024.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sung MJ, Kim DH, Jung YJ, Kang KP, Lee AS, Lee S, et al. Genistein protects the kidney from cisplatin-induced injury. Kidney Int. 2008;74:1538–47. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eshraghi-Jazi F, Nematbakhsh M, Nasri H, Talebi A, Haghighi M, Pezeshki Z, et al. The protective role of endogenous nitric oxide donor (L-arginine) in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity: Gender related differences in rat model. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:1389–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saleh S, Ain-Shoka AA, El-Demerdash E, Khalef MM. Protective effects of the angiotensin II receptor blocker losartan on cisplatin-induced kidney injury. Chemotherapy. 2009;55:399–406. doi: 10.1159/000262453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saad AA, Youssef MI, El-Shennawy LK. Cisplatin induced damage in kidney genomic DNA and nephrotoxicity in male rats: The protective effect of grape seed proanthocyanidin extract. Food Chem Toxicol. 2009;47:1499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2009.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tarladacalisir YT, Kanter M, Uygun M. Protective effects of Vitamin C on cisplatin-induced renal damage: A light and electron microscopic study. Ren Fail. 2008;30:1–8. doi: 10.1080/08860220701742070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vesey DA, Cheung C, Pat B, Endre Z, Gobe G, Johnson DW. Erythropoietin protects against ischaemic acute renal injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:348–55. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nisar S, Feinfeld DA. N-acetylcysteine as salvage therapy in cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Ren Fail. 2002;24:529–33. doi: 10.1081/jdi-120006780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pezeshki Z, Nematbakhsh M, Mazaheri S, Eshraghi-Jazi F, Talebi A, Nasri H, et al. Estrogen abolishes protective effect of erythropoietin against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in ovariectomized rats. ISRN Oncol 2012. 2012:1–7. doi: 10.5402/2012/890310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pezeshki Z, Nematbakhsh M, Nasri H, Talebi A, Pilehvarian A, Safari T, et al. Evidence against protective role of sex hormone estrogen in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in ovariectomized rat model. Toxicol Int. 2013;20:43–7. doi: 10.4103/0971-6580.111568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walker HA, Dean TS, Sanders TA, Jackson G, Ritter JM, Chowienczyk PJ. The Phytoestrogen genistein produces acute nitric oxide-dependent dilation of human forearm vasculature with similar potency to 17beta-estradiol. Circulation. 2001;103:258–62. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bingham SA, Atkinson C, Liggins J, Bluck L, Coward A. Phyto-oestrogens: Where are we now? Br J Nutr. 1998;79:393–406. doi: 10.1079/bjn19980068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tikkanen MJ, Wahala K, Ojala S, Vihma V, Adlercreutz H. Effect of soybean phytoestrogen intake on low density lipoprotein oxidation resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:3106–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Velasquez MT, Bhathena SJ. Dietary phytoestrogens: A possible role in renal disease protection. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:1056–68. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(05)80025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams MR, Golden DL, Register TC, Anthony MS, Hodgin JB, Maeda N, et al. The atheroprotective effect of dietary soy isoflavones in apolipoprotein E-/-’ mice requires the presence of estrogen receptor-α. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2002;22:1859–64. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.0000042202.42136.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Devi K, Vanithakumari G, Anusya S, Mekala N, Malini T, Elango V. Effect of Foeniculum vulgare seed extract on mammary glands and oviducts of ovariectomised rats. Anc Sci Life. 1985;5:129–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaffary F, Ghannadi A, Najafzadeh H. Evaluation of the prophylactic effect of fennel essential oil on experimental osteoporosis model in rats. Int J Pharmacol. 2006;2:588–92. [Google Scholar]

- 21.He W, Huang B. A review of chemistry and bioactivities of a medicinal spice: Foeniculum vulgare. J Med Pl Res. 2011;5:3595–600. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ostad SN, Soodi M, Shariffzadeh M, Khorshidi N, Marzban H. The effect of fennel essential oil on uterine contraction as a model for dysmenorrhea, pharmacology and toxicology study. J Ethnopharmacol. 2001;76:299–304. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(01)00249-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Namavar Jahromi B, Tartifizadeh A, Khabnadideh S. Comparison of fennel and mefenamic acid for the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2003;80:153–7. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(02)00372-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farook T, Vanithakumari G, Bhuvaneswari G, Malini T, Manonayaki S. Effects of anethole on seminal vesicle of albino rats. Anc Sci Life. 1991;11:9–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miraldi E. Comparison of the essential oils from ten Foeniculum vulgare Miller samples of fruits of different origin. Flavour Fragr J. 2000;14:379–82. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams R. Identification of essential oil components by gas chromatography. Mass Spectrometry. 1995:4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baldew GS, McVie JG, van der Valk MA, Los G, de Goeij JJ, Vermeulen NP. Selective reduction of cis-diamminedichloroplatinum (II) nephrotoxicity by ebselen. Cancer Res. 1990;50:7031–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohamed HE, El-Swefy SE, Mohamed RH, Ghanim AM. Effect of erythropoietin therapy on the progression of cisplatin induced renal injury in rats. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2013;65:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joy J, Nair CK. Amelioration of cisplatin induced nephrotoxicity in Swiss albino mice by Rubia cordifolia extract. J Cancer Res Ther. 2008;4:111–5. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.43139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuhad A, Tirkey N, Pilkhwal S, Chopra K. Renoprotective effect of Spirulina fusiformis on cisplatin-induced oxidative stress and renal dysfunction in rats. Ren Fail. 2006;28:247–54. doi: 10.1080/08860220600580399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lau AH. Apoptosis induced by cisplatin nephrotoxic injury. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1295–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Safirstein R, Miller P, Guttenplan JB. Uptake and metabolism of cisplatin by rat kidney. Kidney Int. 1984;25:753–8. doi: 10.1038/ki.1984.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rjiba-Touati K, Boussema IA, Belarbia A, Achour A, Bacha H. Protective effect of recombinant human erythropoietin against cisplatin-induced oxidative stress and nephrotoxicity in rat kidney. Int J Toxicol. 2011;30:510–7. doi: 10.1177/1091581810411931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Appenroth D, Frob S, Kersten L, Splinter FK, Winnefeld K. Protective effects of vitamin E and C on cisplatin nephrotoxicity in developing rats. Arch Toxicol. 1997;71:677–83. doi: 10.1007/s002040050444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mora Lde O, Antunes LM, Francescato HD, Bianchi Mde L. The effects of oral glutamine on cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Pharmacol Res. 2003;47:517–22. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(03)00040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atessahin A, Yilmaz S, Karahan I, Ceribasi AO, Karaoglu A. Effects of lycopene against cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity and oxidative stress in rats. Toxicology. 2005;212:116–23. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohno T, Kato S, Wakatsuki M, Noda SE, Murakami C, Nakamura M, et al. Incidence and temporal pattern of anorexia diarrhea weight loss and leukopenia in patients with cervical cancer treated with concurrent radiation therapy and weekly cisplatin: Comparison with radiation therapy alone. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:94–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Endo Y, Kanbayashi H. Modified rice bran beneficial for weight loss of mice as a major and acute adverse effect of cisplatin. Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;92:300–3. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2003.920608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miya T, Goya T, Yanagida O, Nogami H, Koshiishi Y, Sasaki Y. The influence of relative body weight on toxicity of combination chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1998;42:386–90. doi: 10.1007/s002800050834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yao X, Panichpisal K, Kurtzman N, Nugent K. Cisplatin nephrotoxicity: A review. Am J Med Sci. 2007;334:115–24. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31812dfe1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Javadi S, Ilkhnipour M, Heidari R, Nejati V. The effect foeniculum vulgare mill (Fennel) essential oil on blood glucose in rats. Plant Sci Res. 2008;1:47–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.He Q, Liang CH, Lippard SJ. Steroid hormones induce HMG1 overexpression and sensitize breast cancer cells to cisplatin and carboplatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:5768–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100108697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pabla N, Murphy RF, Liu K, Dong Z. The copper transporter Ctr1 contributes to cisplatin uptake by renal tubular cells during cisplatin nephrotoxicity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296:F505–11. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90545.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qian W, Nishikawa M, Haque AM, Hirose M, Mashimo M, Sato E, et al. Mitochondrial density determines the cellular sensitivity to cisplatin-induced cell death. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;289:C1466–75. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00265.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chirino YI, Pedraza-Chaverri J. Role of oxidative and nitrosative stress in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2009;61:223–42. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yagmurca M, Erdogan H, Iraz M, Songur A, Ucar M, Fadillioglu E. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester as a protective agent against doxorubicin nephrotoxicity in rats. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;348:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swaminathan A, Sridhara SR, Sinha S, Nagarajan S, Balaguru UM, Siamwala JH, et al. Nitrites derived from foneiculum vulgare (Fennel) seeds promotes vascular functions. J Food Sci. 2012;77:H273–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2012.03000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albert-Puleo M. Fennel and anise as estrogenic agents. J Ethnopharmacol. 1980;2:337–44. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(80)81015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]