Abstract

Severe floods triggered by intense precipitation are among the most destructive natural hazards in Alpine environments, frequently causing large financial and societal damage. Potential enhanced flood occurrence due to global climate change would thus increase threat to settlements, infrastructure, and human lives in the affected regions. Yet, projections of intense precipitation exhibit major uncertainties and robust reconstructions of Alpine floods are limited to the instrumental and historical period. Here we present a 2500-year long flood reconstruction for the European Alps, based on dated sedimentary flood deposits from ten lakes in Switzerland. We show that periods with high flood frequency coincide with cool summer temperatures. This wet-cold synchronism suggests enhanced flood occurrence to be triggered by latitudinal shifts of Atlantic and Mediterranean storm tracks. This paleoclimatic perspective reveals natural analogues for varying climate conditions, and thus can contribute to a better understanding and improved projections of weather extremes under climate change.

Mean Central European summer temperatures are projected to increase under global climate change, while summer precipitation totals will likely decrease1,2. However, the frequency of climate extremes, such as intense precipitation events, is more difficult to project, as such events strongly depend upon season, location, and spatial extent3,4,5. Therefore, the analysis of long climate time series supports the identification of climatic processes naturally governing the occurrence of intense precipitation and thus improves the projection of these climate extremes. Instrumental measurements that cover the last 150 years reveal highly resolved precipitation records over space and time6,7, but are too short to detect the natural multi-decadal to centennial variability in the climate system. Longer time series can be reconstructed from historical documents8,9, as well as from geological archives such as riverine overwash deposits10,11. However, both approaches do not provide continuous records over the past millennia11,12, and thus only yield an incomplete palaeoclimatic picture.

Lake sediments, in contrast, reflect past flood activity very accurately, as they record individual events as distinct sediment layers. These ‘turbidites’ or flood deposits provide a continuous flood archive over thousands of years13. The flood deposits are composed of terrigenous material, which is mobilized during intense precipitation in the catchment area and eventually deposited at the bottom of the next downstream lake13,14,15 (Fig. 1). Several studies have established flood records from single lakes16,17,18, however, these records may only reveal a local climate signal and/or may loose their pristine natural signal due to human activity in the corresponding catchment area13,14.

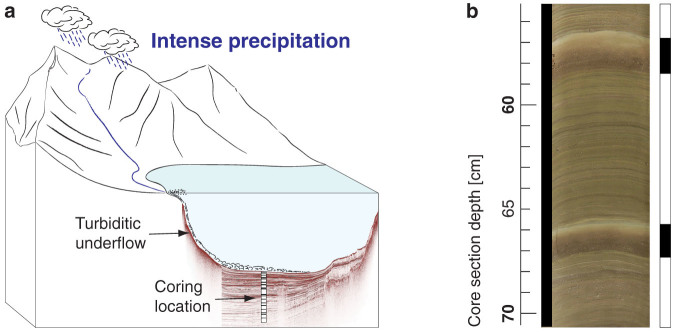

Figure 1. Flood-layer generation.

(a), Sketch illustrating erosion and mobilization of terrestrial material during intense precipitation in the catchment area. The sediment material is fed into the river drainage and upon entering the next downstream lake. The sediment-laden river water proceeds as turbiditic underflow to the deepest part of the lake basin, where the sediment load is deposited as characteristic flood-layer (illustration modified after13). (b), Core photograph with two flood-layers (indicated by black bars) from Lake Glattalp.

Here we present a multi-archive Alpine flood reconstruction based on ten lacustrine sediment records, covering the past 2500 years. The 10 investigated lakes are situated north of the Central Alpine arc along a montane to Alpine transect, spanning an elevation gradient from 447 to 2068 m asl (Fig. 2). This multi-lake compilation allows the extraction of a synoptic, rather than a merely local rainfall signal revealed by a single-lake study14.

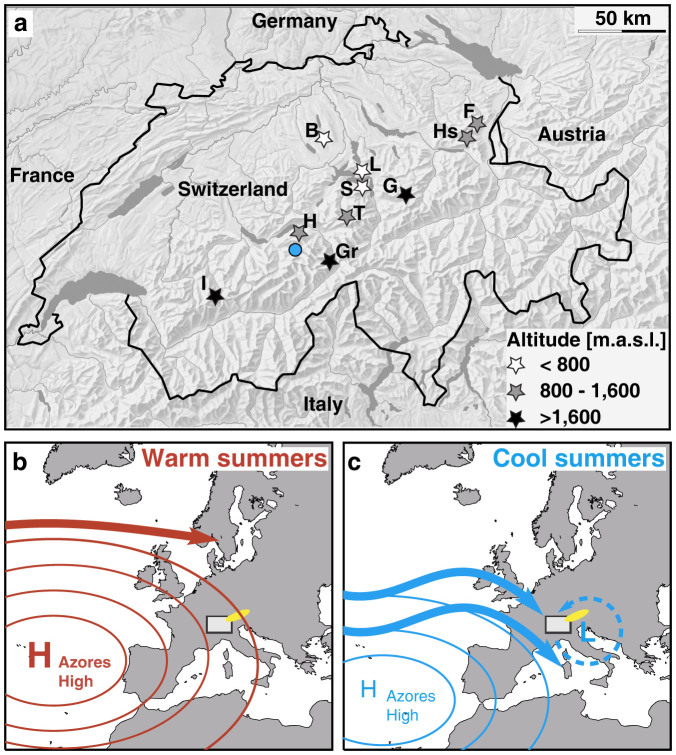

Figure 2. Alpine study sites.

(a), Location of studied lakes: B: Baldegg, F: Fälen, G: Glattalp, Gr: Grimsel, H: Hinterburg, Hs: Hinterer Schwendisee, I: Iffig, L: Lauerz, S: Seelisberg, T: Trüeb. Blue circle indicates the location of the Lower Grindelwald Glacier that was used for reconstruction of glacier-length change22. Relief data and map of Switzerland reproduced with permission of swisstopo/JA100119. (b–c), Schematic illustration of the meridional location and expansion of the Azores high-pressure system during warm and cool summers, controlling the pathways of westerly storm tracks (bold arrows) and the occurrence of Vb cyclones (dashed line). Varying expansion of the Hadley Cell leads to a northward-shift (southward-shift) and strengthening (weakening) of the Azores high-pressure system and of the westerly storm tracks, generating warm (cool) summers with less (more) intense precipitation in the Alps. White rectangle indicates the Alpine study area and yellow ellipse shows the location of the tree-ring-based summer temperature reconstruction used for comparison21.

Results

The complete flood reconstruction contains 842 dated flood layers (Fig. 3a), deposited dominantly from mid-spring to late-fall, since the higher elevated lakes are ice-covered and/or receive precipitation in the form of snow during winter. This seasonal pattern does not impede our flood record, as large floods occur mainly between June and October6,8,19. In order to verify our approach, the established Central Alpine flood reconstruction was compared against an independently established flood record over the past 500 years, which is based on historical documents8. Apart from the early times when the historical evidence appears to be particularly sparse, the two independent datasets are in good agreement (Figs. 3b–c).

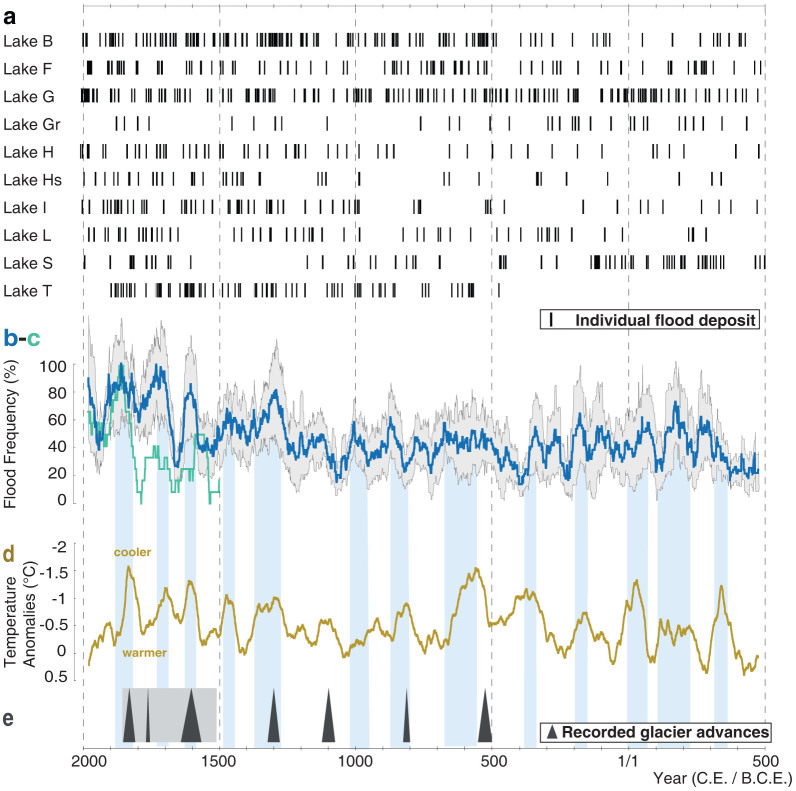

Figure 3. Alpine flood reconstruction.

(a), Flood chronologies of the ten studied lakes. Bars represent individual dated flood deposits. (b), Combination of the ten individual lake records represented as a 50-year moving average of flood events. The resulting frequency values are normalized between no flood activity (0%) and the maximal value (100%). The standard deviation is indicated with grey bars. (c), Historical flood reconstruction from Northern Switzerland (50-year moving average, normalized between 0 and 100%)8. (d), Tree-ring-based Central European summer temperature reconstruction (50-year moving average)21. (e), Major glacial advances reconstructed from the Lower Grindelwald Glacier (Northern Switzerland) indicated with triangles22; grey area marks period of large Alpine glacial extension22. Blue shaded bars indicate periods of high flood frequency that correlate with lower summer temperatures.

Our data show thirteen distinct periods of high flood frequency around 1850, 1740, 1610, 1480, 1380–1300, 1010, 880, 680–580, 350, 180 C.E., and 60, 170, 300 B.C.E. The highest flood frequency is found around 1740 C.E. with events occurring seven times more frequently than during the calmest period at 400 C.E., emphasizing high natural variability of the climate system. The robustness of the flood frequency peaks was tested with a Jackknife analysis (Supplementary notes online). The performed analyses reveal that the main peaks are robust and unlikely of random origin, but also underscore the need of combining records from different lake sites to reconstruct a synoptic rainfall signal. This is illustrated with the uncertainty estimate of the frequency signal, which considerably increases the more lakes from the Central Alpine flood reconstruction are omitted (Supplementary Fig. S1 online). Regarding the best-characterized climatic periods during the past 2500 years20, the flood activity was generally enhanced during the Little Ice Age (1430–1850 C.E.; LIA) compared to the Medieval Climate Anomaly (950–1250 C.E.; MCA) (Fig. 3b). This result is confirmed by other studies documenting an increased (decreased) flood activity during the LIA (MCA) in the Alps8,16,17,18, but our data further documents distinct centennial-scale natural variations in flood occurrence during these contrasting climate periods.

The observed relation between varying flood frequencies and climatically different periods suggests synchronisms between intense precipitation and temperature during the extended summer season. Therefore, our flood chronology was compared to a tree-ring-based summer temperature reconstruction for Central Europe21 (Fig. 3d). The two independent paleoclimatic datasets correlate negatively at r = −0.44 and −0.25 over the past 1300 and 2500 years, respectively. Statistical tests indicate that this anti-correlation is significant (Supplementary Fig. S2 online). In particular, the most distinct cooling events revealed by the summer temperature reconstruction are accompanied by high flood activity. Furthermore, 6 out of 7 major advances of the Lower Grindelwald Glacier that is situated in the studied area22 (Fig. 2a) correspond to periods characterized by enhanced flood frequency during the past 1500 years (Fig. 3e). As the crucial conditions for major glacial advances in the Alps are low summer temperatures22,23, this adds to the important observation that floods occur more frequently during cool summers. However, a distinct advance of Lower Grindelwald Glacier that is accompanied by only slightly enhanced flood frequencies is recognized at around 1100 C.E. (Fig. 3). Yet, as the tree-ring based summer temperature reconstruction does not reveal distinct cool conditions during this period, this specific glacier advance may reflect only slightly decreased summer temperatures, maybe in combination with other climatic factors. Consequently, Central Alpine flood frequency is not considerably enhanced during this period.

Discussion

We interpret the correlation between lower (higher) summer temperatures and enhanced (decreased) flood frequency in terms of North Atlantic atmospheric circulation patterns (Figs. 2b–c): Under current climatic conditions, warm and dry Alpine summers are usually accompanied by anticyclonic (high pressure) circulations that deflect the moist westerly flow towards more northern latitudes24,25 (Supplementary Fig. S3 online). In contrast, cooler summers are rather characterized by zonal westerly or meandering circulations. The latter are generally associated with above-normal precipitation, or may even lead to heavy precipitation events, for instance associated with the Vb cyclone track26 (Supplementary Figs. S4 and S5 online). These tracks are characterized by low-pressure systems moving northeastward from the Adriatic Sea, bringing orographic rainfall that potentially leads to severe flooding along the Alpine crest (Fig. 2c)19,26. Such Vb circulation tracks may occur during both cool and warm conditions27. Nevertheless, we propose that a more southerly position and a weaker expression of the subtropical high-pressure zone favor the occurrence of Vb circulation patterns. In particular, in the late 19th century, which was characterized by generally cool summer conditions28,29, an accumulation of Vb circulation tracks led to a clustering of floods in the Alps8,27.

The scientific literature puts varying emphasis on the different elements of the aforementioned circulation anomaly, and the terminology may invoke the northward extent of the subtropical dry zone (Hadley cell)24,25, or the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO)18,30. For the purpose of the current publication, we consider all these elements as part of one main circulation pattern. Evidence for its importance in shaping European summer climate variability is widespread1. Likewise, climate models yield a poleward expansion of the Hadley cell in response to greenhouse gas forcing24,25. This is related to a strengthening of the subtropical high-pressure zone and a poleward shift of the westerly storm tracks (Fig. 2B). Accordingly, Central European flood occurrence is expected to be lower than today, which is in good agreement with our finding of less frequent floods during warmer periods.

Our study implies that enhanced (decreased) occurrence of westerly and Vb storm tracks during cooler (warmer) summers increase (decrease) the frequency of flood events in the Alps. As the main determining factor for the frequency of intense precipitation events in the Alps, we propose a variable extent of the Hadley Cell and consequently changing atmospheric circulation patterns. This relationship appears applicable to a warmer climate as the subtropical dry zone is expected to expand poleward in response to greenhouse-gas forcing under climate change24. This pattern of less frequent intense precipitation events with warmer summers is regional in nature, thus underscoring the importance of incorporating the different effects of spatial changes in atmospheric circulation patterns in flood frequency reconstruction, as well as in projecting weather extremes under global climate change.

Methods

Sediment retrieval and flood-layer detection

Before sediment coring, every lake (Supplementary Tab. S1 online) was investigated by a high-resolution (3.5 kHz) reflection seismic survey that provided information on the sediment thickness, seismic stratigraphy and lake-basin morphology. The ideal coring location was determined based on the interpretation of the seismic data, and the complete sediment succession was retrieved with a UWITEC percussion piston coring system. Afterwards, the sediment cores were longitudinally cut into halves and the sediment surface was photographed in fresh and oxidized (after few hours exposure) state. The flood-layers were identified by macroscopic observations in combination with measurements of the physical characteristics of the retrieved cores performed by a GEOTEK multi-sensor core logger at a 5 mm sampling interval (gamma-ray attenuation bulk-density, magnetic susceptibility and p-wave velocity). Depending on the individual sediment composition of the different study sites, the flood-layer analysis was supported and complemented by image-analyses techniques, laser-diffraction grain-size analysis, carbon and nitrogen analysis (C/N ratio) and/or computer tomography13,15.

Age model

The topmost core sections were dated using the activity profiles of the radionuclide 137Cs, providing well-constrained age models for the past decades13. The older sections of the sediment sequences were dated by AMS radiocarbon measurements on terrestrial macrofossils (Supplementary Tab. S2 online). Based on the established age-depth models calculated with clam31 (Supplementary Figs. S6 and S7 online), we determined the age of every individual flood-layer (Fig. 3a).

Compiled Alpine flood reconstruction

The individual flood records show strong decadal to centennial fluctuations with site-specific average flood-recurrence rates between 16.7 and 80.7 years over the last 2500 years (Fig. 3). This high variability in the absolute number of recorded floods reflects different susceptibilities of the lakes to record floods. Therefore, we established 50-year moving sums of events and normalized these data sets from 0% (corresponding to no flood-layer) to 100% (maximum number of flood deposits)(Supplementary Fig. S8 online). Comparing the ten flood records, we find no consistent correlation between the individual single lake records (Pearson correlation coefficient between r = −0.3 and r = 0.5). The same observation is made when comparing instrumentally measured single heavy precipitation events in small catchments8. This underscores the complexity of precipitation and flood response and reflects the influence of local phenomena such as spatially confined thunderstorms and/or flood formation. It also emphasizes the importance and advantage of working with a multiple-lake record13,14. In order to combine the ten individual records into one Central Alpine flood reconstruction, we calculated the mean of the normalized flood records and resulting frequency values were again normalized to 0 and 100%. This flood record compilation shows a standard deviation between 5.3 and 44% (Fig. 3) and was tested for its significance by comparing the observed flood frequency variation with the 2σ-range of 10 000 randomized events series and different window sizes of running sum calculations (Supplementary Figs. S9 and S10 online).

Author Contributions

F.S.A., A.G. and G.H.H. designed the project and rose the funding. L.G., S.B.W., F.S.A. and A.G. performed the fieldwork. L.G. established the flood records of the individual lakes. C.S., J.B. and U.B. contributed to the interpretation of the results. All of the authors discussed the data and provided significant input to the final manuscript. The writing of the manuscript was led by L.G.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information for:Frequent floods in the European Alps coincide with cooler periods of the past 2500 years

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Hilbe, R. Hofmann and many others for supporting the fieldwork campaigns; D. Folini, O. Heiri, J. Rajczak and F. Steinhilber for fruitful discussions; I. Brunner and M. Fujak for measuring sediment samples; U. van Raden for a very good collaboration on Lake Baldegg (ETH grant CH1-02-08-2 for core recovery is acknowledged) and T. Frauenfelder and A. Marty from the Institute of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology at the University Hospital Zurich, for producing CT scans of the sediment cores. This work was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF) (Grant 200020-137930 and 200021-121909).

References

- Meehl G. A. et al. Global Climate Projections, in Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Solomon S., et al. Eds. (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2007).

- CH2011, Swiss Climate Change Scenarios CH2011. (published by C2SM, MeteoSwiss, ETH, NCCR Climate, OcCC, Zürich, Switzerland), 88 pp. (2011).

- Rajczak J., Pall P. & Schär C. Projections of extreme precipitation events in regional climate simulations for Europe and the Alpine Region. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 3610–3626 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Trenberth K. E. Changes in precipitation with climate change. Clim. Res. 47(1–2), 123–138 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J. H. & Christensen O. B. Severe summertime flooding in Europe. Nature 421, 805–806 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilker N., Badoux A. & Hegg C. The Swiss flood and landslide damage database 1972–2007. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 9, 913–925 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Schmocker-Fackel P. & Naef F. More frequent flooding? Changes in flood frequency in Switzerland since 1850. J. Hydrol. 381, 1–8 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Schmocker-Fackel P. & Naef F. Changes in flood frequencies in Switzerland since 1500. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 14, 1581–1594 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Mudelsee M., Börngen M., Tetzlaff G. & Grünewald U. Extreme floods in central Europe over the past 500 years: Role of cyclone pathway “Zugstrasse Vb”. J. Geophys. Res. 109, D23101 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann T., Lang A. & Dikau R. Holocene river activity: analysing 14 C-dated fluvial and colluvial sediments from Germany. Quart. Sci. Rev. 27, 2031–2040 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Macklin M. G. et al. Past hydrological events reflected in the Holocene fluvial record of Europe. Catena 66, 145–154 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Brázdil R., Pfister C., Wanner H., von Storch H. & Luterbacher J. Historical Climatology in Europe – The state of the art. Clim. Change 70, 363–430 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Gilli A., Anselmetti F. S., Glur L. & Wirth S. B. Lake sediments as archives of recurrence rates and intensities of past flood events. In: Dating torrential processes on fans and cones - Methods and their application for hazard and risk assessment. Schneuwly-Bollschweiler M., Stoffel M., Rudolf-Miklau F. Eds. (Vol. 47 of Springer Series in Advances in Global Change Research, Dordrecht), pp 225–242 (2013).

- Noren A. J., Biermann P. R., Steig E. J., Lini A. & Southon J. Millennial-scale storminess variability in northeastern United States during the Holocene epoch. Nature 419, 821–824 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb M. P. & Mohrig D. Do hyperpycnal-flow deposits record river-flood dynamics? Geology 37, 1067–1070 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Czymzik M. et al. A 450 year record of spring-summer flood layers in annually laminated sediments from Lake Ammersee (southern Germany). Water Resour. Res. 46, W11528 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelm B. et al. 1400 yr of extreme precipitation patterns over the Mediterranean French Alps and possible forcing mechanisms. Quat. Res. 78, 1–12 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Swierczynski T. et al. A 1600 yr seasonally resolved record of decadal-scale flood variability from the Austrian Pre-Alps. Geology 40, 1047–1050 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Beniston M. August 2005 intense rainfall in Switzerland: Not necessarily an analog for strong convective events in a greenhouse climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L05701 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Wanner H. et al. Mid- to Late Holocene climate change: an overview. Quat. Sci. Rev. 27, 1791–1828 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Büntgen U. et al. 2500 years of European climate variability and human susceptibility. Science 331, 578–582 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzhauser H., Magny M. & Zumbühl H. J. Glacier and lake-level variations in west-central Europe over the last 3500 years. Holocene 15, 789–801 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Paul F., Kääb A., Maisch M., Kellenberger T. & Haeberli W. Rapid disintegration of Alpine glaciers observed with satellite data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L21402 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Lu J., Vecchi G. A. & Reichler T. Expansion of the Hadley cell under global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L06805 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Haigh J. D. The impact of solar variability on climate. Science 272, 981–984 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zängl G. Interaction between dynamics and cloud microphysics in orographic precipitation enhancement: A high-resolution modeling study of two North Alpine heavy-precipitation events. Mon. Weather Rev. 135, 2817–2840 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Bichet A., Folini D., Wild M. & Schär C. Enhanced European summer precipitation in the late nineteenth century. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 10.1002/qj.2111 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Casty C., Wanner H., Luterbacher J., Esper J. & Böhm R. Temperatures and precipitation variability in the European Alps since 1500. Int. J. Climatol. 25, 1855–1880 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Luterbacher J., Dietrich D., Xoplaki E., Grosjean M. & Wanner H. European seasonal and annual temperature variability, trends, and extremes since 1500. Science 303, 1499–1503 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Puertas C. et al. Regional atmospheric circulation shifts induced by a grand solar minimum. Nature Geosci. 5, 397–401 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Blaauw M. Methods and code for ‘classical’ age-modelling of radiocarbon sequences. Quat. Geochronol. 5, 512–518 (2010). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information for:Frequent floods in the European Alps coincide with cooler periods of the past 2500 years