Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

We characterized breastfeeding concerns from open-text maternal responses and determined their association with stopping breastfeeding by 60 days (stopping breastfeeding) and feeding any formula between 30 and 60 days (formula use).

METHODS:

We assessed breastfeeding support, intentions, and concerns in 532 expectant primiparas and conducted follow-up interviews at 0, 3, 7, 14, 30, and 60 days postpartum. We calculated adjusted relative risk (ARR) and adjusted population attributable risk (PAR) for feeding outcomes by concern category and day, adjusted for feeding intentions and education.

RESULTS:

In 2946 interviews, 4179 breastfeeding concerns were reported, comprising 49 subcategories and 9 main categories. Ninety-two percent of participants reported ≥1 concern at day 3, with the most predominant being difficulty with infant feeding at breast (52%), breastfeeding pain (44%), and milk quantity (40%). Concerns at any postpartum interview were significantly associated with increased risk of stopping breastfeeding and formula use, with peak ARR at day 3 (eg, stopping breastfeeding ARR [95% confidence interval] = 9.2 [3.0–infinity]). The concerns yielding the largest adjusted PAR for stopping breastfeeding were day 7 “infant feeding difficulty” (adjusted PAR = 32%) and day 14 “milk quantity” (adjusted PAR = 23%).

CONCLUSIONS:

Breastfeeding concerns are highly prevalent and associated with stopping breastfeeding. Priority should be given to developing strategies for lowering the overall occurrence of breastfeeding concerns and resolving, in particular, infant feeding and milk quantity concerns occurring within the first 14 days postpartum.

Keywords: breastfeeding, infant, lactation, concerns, problems

What’s Known on This Subject:

Although most US mothers initiate breastfeeding, half fail to achieve their breastfeeding intentions. In cross-sectional and retrospective surveys, early breastfeeding difficulties are often cited as reasons for stopping breastfeeding earlier than intended.

What This Study Adds:

We characterized 4179 breastfeeding concerns/problems as reported by primiparas interviewed prospectively. Concerns were highly prevalent and associated with up to ninefold greater risk of stopping breastfeeding earlier than intended. Concerns at 3 to 7 days posed the greatest risk.

Although 75% of mothers in the United States initiate breastfeeding, only 13% are exclusively breastfeeding for the recommended duration of 6 months.1 Undoubtedly, prenatal breastfeeding intention is an important determinant of breastfeeding practices2; yet, one-half of US mothers fail to achieve their breastfeeding intention, supplementing with infant formula or stopping breastfeeding altogether earlier than planned.3,4

New mothers commonly describe the first few weeks of breastfeeding as surprisingly difficult, with many unanticipated problems arising.5,6 In cross-sectional and retrospective studies, these early breastfeeding challenges are often cited as reasons for early formula use and termination of breastfeeding.7,8 However, mothers’ retrospective reports may be biased by their current feeding status. To develop targeted strategies for supporting US mothers in achieving their breastfeeding goals, we need to prospectively identify the specific types and timing of breastfeeding problems that are most likely to lead to formula use.

We characterized the breastfeeding concerns and problems of a large and diverse cohort of first-time mothers as prospectively reported prenatally and at 0, 3, 7, 14, 30, and 60 days postpartum. We then determined the adjusted relative risks (ARRs) of (1) using formula or (2) having stopped breastfeeding by 60 days postpartum, according to the type and timing of breastfeeding concerns reported at earlier interviews, after accounting for prenatal breastfeeding intention.

Methods

Study Design

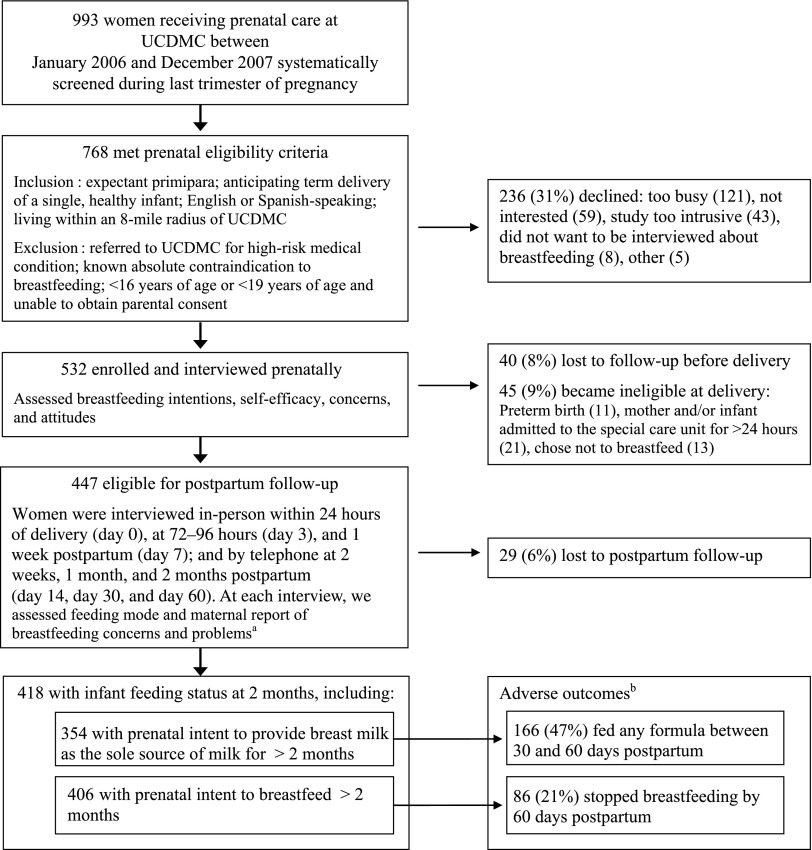

To achieve our objectives, we analyzed data from the Early Lactation Success study. Study design, screening, and enrollment are described elsewhere9,10 and summarized in Fig 1. Briefly, in this prospective cohort study based at the University of California Davis Medical Center (UCDMC), expectant first-time mothers were initially enrolled and interviewed between 32 and 40 weeks’ gestation. Follow-up continued with 6 postpartum interviews through the first 2 months or until the mother reported that she was no longer breastfeeding or feeding her expressed breast milk.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of participant screening, enrollment, and follow-up in the Early Lactation Success study. a Maternally reported breastfeeding concerns and problems are referred to as “breastfeeding concerns” throughout the text. b Overall, 46.4% (194/418) fed any formula between 30 and 60 days and 22.7% (95/418) stopped breastfeeding by 60 days postpartum.

The UCDMC, while not “baby friendly” certified, has a breastfeeding policy consistent with the Ten Steps for Successful Breastfeeding.11 During the study period, International Board Certified Lactation Consultants were generally available on the maternity unit 6 days per week and after discharge at the UCDMC Breastfeeding Clinic. The study research assistants referred participants to UCDMC breastfeeding support resources as needed.

This study and subsequent analyses were approved by the University of California Davis Institutional Review Board, with additional approval for continued data analysis from the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Data Collection

Prenatal

A trained research assistant conducted the prenatal interview in-person and in the participant’s preferred language (English or Spanish). During the prenatal interview, we collected socio-demographic data (including self-identified ethnicity, years of education completed, and health-insurance status, used as a proxy for income). We also interviewed participants about infant feeding attitudes and intentions (refer to online supplement for specific questions asked), including length of planned breastfeeding duration, age when planning to introduce infant formula or other milks, breastfeeding self-efficacy,12 infant feeding practices of family and friends, and strength of intentions to provide breast milk as the sole milk source for 6 months. For the latter, we used the validated Infant Feeding Intentions Scale,13 with possible scores ranging from 0 (not planning to breastfeed at all) to 16 (very much agree that I will be breastfeeding my infant without using any formula or other milk for at least the first 6 months). We assessed maternally reported breastfeeding concerns by asking the open-ended interview question, “What concerns, if any, do you have about being able to breastfeed?” Further details about the prenatal interview have been described previously.9

Postnatal

The Follow-up Team operated without knowledge of the mothers’ responses to the prenatal interview, to prevent bias in data collection regarding feeding concerns and practices. We determined infant feeding status at each follow-up interview time point (see Fig 1 for definitions).

We assessed maternally reported breastfeeding problems/concerns (hereafter referred to as breastfeeding concerns) in participants who had attempted to breastfeed or feed their infant expressed breast milk since the previous interview. We asked at each follow-up interview to “Please describe any problems or concerns you have had since our last interview or are currently having about feeding your infant, including breastfeeding problems, concerns, or discomforts.” Participants could list as many concerns as they wished. Interviewers specifically inquired about concerns that were mentioned, but not resolved, at the previous interview.

We assessed participants’ reported support for and attitudes toward breastfeeding through an ad hoc composite score of 3 Likert-type questions about recognized barriers to breastfeeding14 asked at day 3: (1) “How much support for breastfeeding do you receive from close family and friends?” (2) “Compared to bottle feeding, how convenient do you think breastfeeding is?” (3) “Do you feel embarrassed to breastfeed or think you might find breastfeeding embarrassing?” Each question was scored 0, 1, or 2 for a maximum of 6.

Collection of labor and delivery information, measurement of maternal BMI at day 7, and medical record data extraction are described elsewhere.10,15

Qualitative Data Analysis

The primary coder (Ms Wagner) reviewed all the breastfeeding concern responses from all interview time points to assess the scope of the responses provided. She then sorted responses by salient words and concepts by using a “cut and paste” approach to develop a preliminary coding framework.16 Two secondary coders (Drs Nommsen-Rivers and Chantry) reviewed the coding framework, and all 3 discussed cases where there was disagreement and achieved a final coding framework by consensus, consolidating related codes to create subcategories and main categories of breastfeeding concerns. The primary coder applied the final coding framework to all responses from all 7 interview time points. Multiple codes could be assigned to each response. At regular intervals throughout the coding process, the secondary coders reviewed the assignment of codes and resolved discrepancies through discussion.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Maternal Characteristics

We categorized all covariates as described previously.10 In particular, we categorized education level as high school diploma or less versus some college or more and categorized the Infant Feeding Intentions Scale score as weak (0–7.5), moderate (8–11.5), strong (12–15.5), or very strong (a maximum score of 16). We categorized the breastfeeding support composite score (reported support for and attitudes toward breastfeeding) at day 3 as least (0–4), moderate (5), and most (6).

Prevalence of Breastfeeding Concerns

All participants who responded to the breastfeeding concern question were coded for the absence or presence of each breastfeeding concern subcategory and main category at each interview time point.

Modeling Risk of Adverse Outcomes

We modeled the risk of the following 2 adverse outcomes: stopped breastfeeding by 60 days (defined as no breastfeeds or expressed breast milk feeds in the 24 hours preceding day 60) and fed any formula between 30 and 60 days postpartum (defined as supplementing breastfeeding with formula or feeding only formula between day 30 and day 60; ie, lack of “full breastfeeding”17). For the outcome “stopped breastfeeding by 60 days,” we restricted the analysis to participants with prenatal intent to breastfeed for at least 2 months and for “fed any formula between 30 and 60 days” we restricted the analysis to participants with prenatal intent to provide breast milk as the sole milk source for at least 2 months.

To identify potentially confounding variables, we performed χ2 analysis to evaluate the associations of maternal characteristics with breastfeeding concerns and with our 2 adverse outcomes. We then used logistic regression analysis to estimate the odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for these 2 outcomes by main categories of breastfeeding concerns in both unadjusted and adjusted models. Since the OR overestimates relative risk when outcomes are common,18 for select models we also calculated the ARR and 95% CI by using the method described by Kleinman and Norton.19

Finally, to determine the overall impact of the more common breastfeeding concerns on stopping breastfeeding, we calculated population attributable risks (PARs). In this study PAR represents the excess proportion of those who stopped breastfeeding that could theoretically be eliminated by prevention of a particular breastfeeding concern at a specific time point. We adapted a formula from Szklo and Nieto,18 substituting ARR for RR, to calculate adjusted PAR [prevalence of breastfeeding concern × (ARR – 1)] ÷ [prevalence of breastfeeding concern × (ARR – 1) + 1] × 100.

All analyses were performed by using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Cohort Characteristics and Categories of Breastfeeding Concerns

Figure 1 summarizes sample size across study time points, and Table 1 presents cohort characteristics. None of the characteristics presented in Table 1 differed significantly between the prenatal and follow-up cohorts.

TABLE 1.

Socio-demographic Characteristics of Prenatal Cohort (n = 532)

| Variablea | n | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | ||

| <25 | 258 | 49 |

| 25–29.9 | 130 | 24 |

| >30 | 144 | 27 |

| Education | ||

| < High school | 91 | 17 |

| High school graduate | 123 | 23 |

| Some college | 132 | 25 |

| College graduate | 186 | 35 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Asian | 64 | 12 |

| African American | 75 | 14 |

| Hispanic (primarily English-speaking) | 80 | 15 |

| Hispanic (primarily Spanish-speaking) | 62 | 12 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 218 | 41 |

| Identifies with >1 ethnic category | 33 | 6 |

| Health insurance status | ||

| Private | 267 | 51 |

| Public | 261 | 49 |

No characteristic was significantly different between the prenatal and follow-up cohorts.

In total, participants reported 4179 breastfeeding concerns over 2946 interviews. In our qualitative analysis, we identified 49 distinct breastfeeding concerns, which we consolidated into 9 main thematic categories. These main categories and their subcategories are described in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Breastfeeding Concern Main Categories and Subcategories

| Main Categorya | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| 1. Infant feeding difficulty | Problems with latch |

| Encompasses reported difficulties with how the infant is feeding at the breast | Infant sleepy or going too long between breastfeeds |

| Infant refuses to breastfeed/nipple confusion | |

| Infant fussy or frustrated at the breast | |

| Problems with the frequency or length of infant’s breastfeeds | |

| Infant not feeding well | |

| Other difficulty feeding at the breast | |

| 2. Milk quantity | Inadequate maternal production or milk supply |

| Includes concerns that the mother is not producing or the infant is not getting sufficient breast milk | Infant not getting enough milk or unsure if getting enough milk |

| Infant shows signs of hunger | |

| Milk not in | |

| 3. Uncertainty with own breastfeeding ability | Breastfeeding technique, positioning, or getting used to breastfeeding |

| Responses in which the mother questions her own breastfeeding skills or perseverance | Not sure how long breastfeeding duration or frequency should be |

| Breast anatomy adequacy | |

| Milk quality or nutritional adequacy of exclusive breast milk diet | |

| Breastfeeding too difficult or time-consuming | |

| Wanting someone else to feed the infant | |

| Tired or exhausted | |

| Uncomfortable with the act or connotations of breastfeeding | |

| Not meeting breastfeeding goals | |

| Other uncertainty with breastfeeding ability | |

| 4. Pain while breastfeeding | Painful nipples |

| Includes nipple pain or any other pain associated with breastfeeding | General or unspecified breastfeeding pain |

| Sore breasts, engorgement, or breast pain | |

| Cesarean delivery or other pain not related to breasts or nipples | |

| Mastitis | |

| Thrush or yeast infection | |

| Biting | |

| 5. Signs of inadequate intake | Weight loss |

| Includes references to medical signs in the infant of inadequate milk intake | Jaundice |

| Urine and stool output or signs of dehydration | |

| Hypoglycemia | |

| 6. Mother/infant separation | Work or school |

| Other separation | |

| 7. Maternal health/medication | Medications affecting infant through breast milk |

| References to medications or health conditions (whether true contraindications or not) interfering with breastfeeding | Medication and effect on milk supply |

| Maternal health problem related to breastfeeding | |

| 8. Too much milk | General too much milk |

| Includes references to strong milk ejection reflex or leaking | Strong let-down |

| Leaking | |

| 9. Other | Formula-feeding |

| Refers to feeding problems or concerns not directly related to feeding at the breast | Digestive issues, spitting up |

| Burping | |

| Infant medical concern (other than sign of inadequate intake) | |

| Pacifier | |

| Pumping or expressing breast milk | |

| Breastfeeding aids or alternate feeding methods | |

| Overfeeding | |

| Other infant behavior (nonspecific to feeding) |

Overall, 4179 distinct feeding problems or concerns were reported over 2946 combined interviews (prenatal and days 0, 3, 7, 14, 30, and 60 postpartum). At each interview, women were asked to describe any problems or concerns they had (currently or since the previous interview) about feeding their infant; postpartum interviews were only conducted with women who had breastfed or expressed their breast milk since the previous interview.

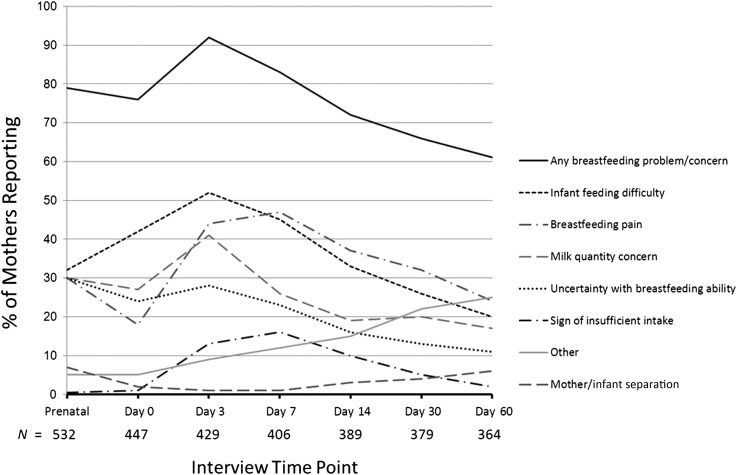

Figure 2 displays the prevalence of breastfeeding concerns over time. All main categories, but not all subcategories, were represented at every interview time point. At the prenatal interview, 79% of mothers reported at least 1 infant feeding concern. Postnatally, the prevalence of any breastfeeding concern peaked at day 3 (92%) and declined gradually thereafter, but the majority of participants continued to report breastfeeding concerns throughout the study. “Infant feeding difficulty” was the most prevalent concern reported at day 0 (44%) and day 3 (54%). “Pain while breastfeeding” peaked at day 7 (47%) and was the most prevalent concern at that and subsequent interviews. Concern about “milk quantity” peaked at day 3 (41%). Prevalence of maternal report of “uncertainty with own breastfeeding ability” was highest at the prenatal interview (28%).

FIGURE 2.

Prevalence of maternally reported breastfeeding concerns (main categories) by interview time point. At the prenatal interview, women were asked about their breastfeeding concerns. At each postpartum interview, women who had breastfed or expressed their breast milk since the previous interview were asked to describe any problems or concerns they had (currently or since the previous interview) about feeding their infant. Main categories in legend are presented top to bottom in order of prevalence at the day 3 interview. “Maternal health and medication” and “too much milk” main categories are not shown (prevalence ≤ 2% at any time point). Prevalence results are not adjusted for confounders.

Supplemental Table 4 details the prevalence of the most common breastfeeding concerns at the prenatal, day 3, and day 7 interviews, stratified by maternal characteristics.

Risk of Adverse Outcomes

Of women who planned prenatally to provide breast milk as the sole source of milk for >2 months, 47% (166/354) fed any formula between 30 and 60 days. Of women who planned prenatally to breastfeed > 2 months, 21% (86/406) stopped breastfeeding by 60 days (Fig 1). Table 3 presents the OR and adjusted OR for these outcomes by breastfeeding concern at each interview time point. In our final adjusted models, we included prenatal Infant Feeding Intention category and education level as covariates. Addition of maternal age, ethnicity, health insurance status, and prenatal breastfeeding self-efficacy did not cause significant change in models already adjusted for prenatal Infant Feeding Intention category and maternal education.

TABLE 3.

ORs for Fed Any Formula Between 30 and 60 Days and Stopped Breastfeeding by 60 Days by Breastfeeding Concern Main Category

| Interview Time Pointa | Breastfeeding Concern Main Category | Fed Any Formula Between 30 and 60 db | Stopped Breastfeeding by 60 dc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of Report of Concern, N (%) | Fed Any Formula (%) in Mothers With Versus Without Concern, With/Without | OR (95% CI)d | Adjusted OR (95% CI)d,e | Frequency of Report of Concern, N (%) | Stopped Breastfeeding (%) in Mothers With Versus Without Concern, With/Without | OR (95% CI)d | Adjusted OR (95% CI)d,e | ||

| PN | Any concern | 278 (79) | 48.2/42.7 | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 1.3 (0.8–2.2) | 323 (80) | 22.6/15.7 | 1.6 (0.8–3.0) | 1.6 (0.8–3.1) |

| Infant feeding difficulty | 125 (35) | 44.0/48.7 | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 140 (34) | 20.0/21.8 | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | 0.96 (0.6–1.7) | |

| Milk quantity concern | 114 (32) | 43.0/49.0 | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 128 (32) | 18.0/22.7 | 0.8 (0.4–1.3) | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | |

| Uncertainty with breastfeeding | 102 (29) | 52.0/45.0 | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 121 (30) | 26.4/18.9 | 1.5 (0.9–2.5) | 1.5 (0.9–2.6) | |

| Breastfeeding pain | 101 (29) | 48.5/46.4 | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 117 (29) | 19.7/21.8 | 0.9 (0.4–1.3) | 0.7 (0.4–1.5) | |

| Day 0 | Any concern | 272 (77) | 50.7/35.8 | 1.9 (1.1–3.1) | 1.9 (1.1–3.2) | 310 (76) | 23.5/14.6 | 1.8 (0.97–3.4) | 2.4 (1.2–4.8) |

| Infant feeding difficulty | 155 (44) | 51.6/43.9 | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | 1.3 (0.9–2.0) | 172 (42) | 26.2/17.9 | 1.6 (1.01–2.6) | 1.8 (1.1–3.0) | |

| Milk quantity concern | 100 (28) | 59.0/42.7 | 1.9 (1.2–3.1) | 1.9 (1.2–3.1) | 106 (26) | 26.4/19.7 | 1.5 (0.9–2.5) | 1.6 (0.9–2.8) | |

| Uncertainty with breastfeeding | 85 (24) | 51.8/45.9 | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 1.3 (0.8–2.2) | 99 (24) | 22.2/21.2 | 1.1 (0.6–1.8) | 1.2 (0.6–2.1) | |

| Breastfeeding pain | 61 (17) | 47.5/47.3 | 1.01 (0.6–1.8) | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 73 (18) | 16.4/22.5 | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 0.7 (0.4–1.5) | |

| Sign of insufficient intake | 4 (1) | 75.0/47.0 | 3.4 (0.4–32.9) | 4.1 (0.4–40.3) | 5 (1) | 0/21.7 | NA | NA | |

| Day 3 | Any concern | 324 (92) | 49.7/14.8 | 5.7 (1.9–16.8) | 5.8 (1.9–17.4) | 368 (92) | 22.8/2.9 | 9.8 (1.3–72.4) | 14.1 (1.8–110) |

| Infant feeding difficulty | 188 (54) | 53.7/39.3 | 1.8 (1.2–2.8) | 1.7 (1.1–2.7) | 212 (53) | 26.4/15.3 | 2.0 (1.2–3.3) | 2.1 (1.2–3.5) | |

| Milk quantity concern | 146 (42) | 58.2/39.3 | 2.2 (1.4–3.4) | 2.2 (1.4–3.4) | 160 (40) | 26.3/17.8 | 1.7 (1.02–2.7) | 2.0(1.2–3.3) | |

| Uncertainty with breastfeeding | 101 (29) | 50.5/45.6 | 1.2 (0.8–1.9) | 1.3 (0.8–2.2) | 116 (29) | 21.6/21 | 1.03 (0.6–1.8) | 1.3 (0.7–2.3) | |

| Breastfeeding pain | 147 (42) | 49.7/45.1 | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 173 (43) | 24.9/18.3 | 1.5 (0.9–2.4) | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) | |

| Sign of insufficient intake | 51 (15) | 43.1/47.7 | 0.8 (0.5–1.5) | 0.91 (0.5–1.7) | 55 (14) | 7.3/23.3 | 0.3 (0.09–0.7) | 0.3 (0.1–1.01) | |

| Day 7 | Any concern | 285 (83) | 48.4/35.1 | 1.7 (0.96–3.1) | 2.0 (1.1–3.7) | 327 (83) | 22.6/6.2 | 4.5 (1.6–12.7) | 6.5 (2.2–19.3) |

| Infant feeding difficulty | 153 (45) | 54.2/39.7 | 1.8 (1.2–2.8) | 1.9 (1.2–2.9) | 174 (44) | 27/14.2 | 2.2 (1.4–3.7) | 2.8 (1.6–4.8) | |

| Milk quantity concern | 92 (27) | 68.5/38 | 3.5 (2.1–5.9) | 3.8 (2.3–6.4) | 103 (26) | 29.1/16.6 | 2.1 (1.2–3.5) | 2.7 (1.5–4.8) | |

| Uncertainty with breastfeeding | 75 (22) | 57.3/43.1 | 1.8 (1.1–3.0) | 2.0 (1.2–3.4) | 91 (23) | 24.2/18.6 | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) | 1.67 (0.91–3.1) | |

| Breastfeeding pain | 155 (45) | 46.5/46 | 1.02 (0.7–1.6) | 1.03 (0.7–1.6) | 182 (46) | 24.7/15.7 | 1.8(1.1–2.9) | 1.7 (0.99–2.9) | |

| Sign of insufficient intake | 57 (17) | 50.9/45.3 | 1.3 (0.7–2.2) | 1.4 (0.8–2.5) | 62 (16) | 11.3/21.5 | 0.5 (0.2–1.06) | 0.6 (0.3–1.5) | |

| Day 14 | Any concern | 244 (73) | 50.4/29.3 | 2.5 (1.5–4.1) | 2.9 (1.7–5.0) | 273 (72) | 19.0/9.4 | 2.3 (1.1–4.6) | 3.2 (1.5–6.9) |

| Infant feeding difficulty | 113 (34) | 49.6/42.2 | 1.4 (0.9–2.1) | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) | 124 (33) | 20.2/14.5 | 1.5 (0.9–2.6) | 1.8 (0.96–3.2) | |

| Milk quantity concern | 65 (19) | 69.2/38.7 | 3.6 (2.0–6.4) | 4.11 (2.3–7.5) | 72 (19) | 29.2/13.4 | 2.7 (1.5–4.9) | 4.0 (2.0–7.8) | |

| Uncertainty with breastfeeding | 52 (15) | 57.7/42.3 | 1.9 (1.02–3.4) | 2.1 (1.1–3.9) | 58 (15) | 17.2/16.2 | 1.1 (0.5–2.3) | 1.4 (0.6–3.2) | |

| Breastfeeding pain | 124 (37) | 48.4/42.5 | 1.3 (0.8–2.0) | 1.3 (0.8–2.1) | 139 (37) | 19.4/14.6 | 1.4 (0.8–2.5) | 1.5 (0.9–2.7) | |

| Sign of insufficient intake | 35 (10) | 68.6/41.9 | 3.0 (1.4–6.4) | 3.5 (1.6–7.4) | 38 (10) | 15.8/16.4 | 0.95 (0.4–2.4) | 1.4 (0.5–3.8) | |

| Day30 | Any concern | 223 (68) | 48.9/32.4 | 2.0 (1.2–3.3) | 2.2 (1.3–3.5) | 248 (66) | 17.7/10.4 | 1.9 (0.96–3.6) | 2.5 (1.2–5.0) |

| Infant feeding difficulty | 88 (27) | 46.6/42.5 | 1.2 (0.7–1.9) | 1.2 (0.8–2.0) | 97 (26) | 15.5/15.2 | 1.0 (0.5–1.9) | 1.3 (0.7–2.5) | |

| Milk quantity concern | 64 (20) | 76.6/35.6 | 5.9 (3.1–11.1) | 6.5 (3.4–12.4) | 73 (20) | 26.0/12.7 | 2.4 (1.3–4.5) | 2.9 (1.5–5.6) | |

| Uncertainty with breastfeeding | 41 (13) | 56.1/41.8 | 1.8 (0.9–3.5) | 1.8 (0.9–3.5) | 47 (13) | 25.5/13.8 | 2.1 (1.03–4.4) | 2.6 (1.2–5.7) | |

| Breastfeeding pain | 110 (34) | 50.0/40.4 | 1.5 (0.9–2.3) | 1.5 (0.9–2.4) | 121 (32) | 19.0/13.5 | 1.5 (0.8–2.7) | 1.6 (0.9–3.0) | |

| Sign of insufficient intake | 15 (5) | 66.7/42.5 | 2.7 (0.9–8.1) | 2.8 (0.9–8.5) | 17 (5) | 23.5/14.9 | 1.8 (0.6–5.6) | 2.3 (0.7–7.9) | |

PN, prenatal interview at 32–40 weeks' gestation; Day 0, within 24 hours postpartum; Day 3, 72–96 hours postpartum; Day 7, Day 14, and Day 30 at 1 week, 2 weeks, and 1 month postpartum, respectively.

Analysis restricted to mothers who indicated prenatally their intent to provide breast milk as the sole source of milk >2 mo (N = 353, PN and day 0; N = 351, day 3; N = 342, day 7; N = 336, day 14; N = 328, day 30).

Analysis restricted to mothers who indicated prenatally their intent to breastfeed >2 mo (N = 406, PN and day 0; N = 402, day 3; N = 392, day 7; N = 379, day 14; N = 373, day 30).

Referent = mothers who did not report the problem or concern.

Adjusted for prenatal Infant Feeding Intentions Scale category and maternal education level. Further adjustment for maternal age, ethnicity, health insurance status, or prenatal breastfeeding self-efficacy did not appreciably change the parameter estimates of the models.

Overall, the ARR of having fed any formula between 30 and 60 days and stopped breastfeeding by 60 days were significantly greater among those with any (versus no) breastfeeding concern at each of the postnatal (but not prenatal) interview time points in adjusted models. The relative risk was highest at day 3: ARR (95% CI), 3.3 (1.7–15.0) for fed any formula between 30 and 60 days; and 9.2 (3.0–infinity) for stopped breastfeeding by 60 days.

Only 1 of the 34 women who reported no breastfeeding concerns at day 3 had stopped breastfeeding by 60 days. These 34 women presented a rare characteristic (no reported breastfeeding concerns at day 3) associated with a positive outcome (nearly all still breastfeeding at day 60), a condition described as “positive deviance.”20,21 We carried out a post hoc analysis of differences between this group and women who reported 1 or more breastfeeding concerns at day 3. The former were significantly more likely than the latter to be <30 years of age, Hispanic, have strong prenatal breastfeeding self-efficacy, have had an unmedicated vaginal delivery, and report strong breastfeeding support (Supplemental Fig 5).

The breastfeeding concern main categories significantly associated during at least 1 postpartum interview time point with increased risk of having fed any formula between 30 and 60 days and/or stopping breastfeeding by 60 days in adjusted logistic regression models were milk quantity concern, infant feeding difficulty, uncertainty with breastfeeding ability, and “sign of insufficient intake” (Fig 3). In unadjusted models, pain while breastfeeding at day 7 was associated with stopping breastfeeding by 60 days, but the significance disappeared after adjusting for feeding intention category and education level (Table 3). Report of “other” breastfeeding concerns was not significantly associated with either adverse outcome. We did not examine concerns categorized as “mother-infant separation,” “maternal health/medication,” or “too much milk,” in relation to either adverse outcome because their prevalence never exceeded 10%.

FIGURE 3.

ARR of having fed any formula between 30 and 60 days and stopped breastfeeding by 60 days by main category of breastfeeding concern at each interview time point (referent = no concern within the specified category at the same time point). Models were adjusted for Infant Feeding Intention Scale category and maternal education level. All main categories significant at ≥1 time point are shown (with the exception of “signs of inadequate intake” at day 14: ARR of feeding any formula days 30–60 = 1.70, P < .01). Postpartum interviews were only conducted with women who had breastfed or expressed their breast milk since the previous interview. The fed any formula model was restricted to mothers with prenatal intent to provide breast milk as the sole milk source for > 2 months (sample size, range 328–354 per interview time point). The stopped breastfeeding model was restricted to mothers with prenatal intent to breastfeed > 2 months (sample size, range 373–406 per interview time point). Significant relationships (P < .05) at each interview time point are indicated by a filled square.

Refer to Supplemental Table 5 for examination of the odds of stopping breastfeeding stratified by breastfeeding concern subcategories for the most commonly reported main categories. Most notably, the predominant subcategories at day 7 contributing to stopping breastfeeding under the infant feeding difficulty main category were “fussy or frustrated at the breast,” “infant refusing to breastfeed/nipple confusion,” and “problems with latch.”

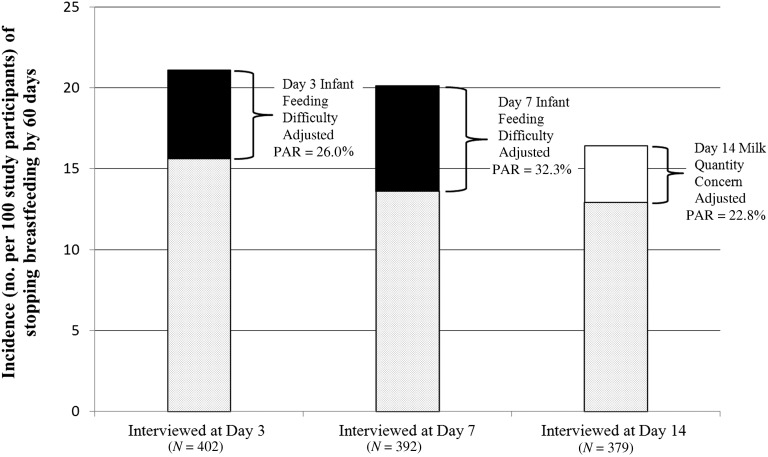

Population Attributable Risk

The greatest contributors to stopping breastfeeding by 60 days were day 3 or day 7 infant feeding difficulty concerns (adjusted PAR, 26% and 32%, respectively) and day 14 milk quantity concerns (adjusted PAR, 23%; Fig 4).

FIGURE 4.

Adjusted PAR for select breastfeeding concerns based on estimated risk adjusted for prenatal Infant Feeding Intention Scale category and maternal education level. For each time point, total bar height denotes overall incidence of having stopped breastfeeding by 60 days (per 100 study participants with prenatal intent to breastfeed > 2 months and breastfed 1 or more times since previous interview time point). Solid portion of each bar denotes percent “stopped breastfeeding” attributable to report of specified breastfeeding concern for same time point: closed square = infant feeding difficulty; open square = milk quantity concern.

Discussion

Among a diverse cohort of first-time mothers, breastfeeding concerns during the first 2 months postpartum were highly prevalent, persistent, and associated with not meeting breastfeeding goals. Adjustment for maternal education and prenatal breastfeeding intentions only strengthened associations between concerns and adverse outcomes, suggesting that our findings are not explained by weak intentions or demographic factors. Notably, prenatal concerns were not associated with adverse outcomes (ie, these results do not appear to be simply the “self-fulfillment” of anticipated problems). Further, although there were wide differences in the prevalence of prenatal breastfeeding concerns by demographic strata, demographic differences in postnatal breastfeeding concerns largely diminished as challenges in successfully establishing breastfeeding became nearly universal across all strata. The generalizability of our findings may be limited to settings with similar levels of breastfeeding support: the association between breastfeeding concerns and later formula use may be weaker in a baby-friendly hospital but may be stronger in a community where breastfeeding is less normative.

Similar to the findings of Taveras et al,7 we observed that breastfeeding concerns reported early in the maternity stay (ie, our day 0 interview) were only modestly associated with using formula between 30 and 60 days postpartum or stopping breastfeeding. However, concerns reported later in the first week postpartum were strongly associated with these adverse outcomes. This may be because our day 3 and day 7 interviews captured a time when there is often a gap between hospital and community lactation support resources. Even after excluding those who planned to introduce formula in the first 2 months, 50% of women who reported at least 1 breastfeeding concern at day 3 ended up feeding formula between 30 and 60 days postpartum, compared with only 15% of women who reported no breastfeeding concern. Similarly, 23% of women with at least 1 breastfeeding concern at day 3 had stopped breastfeeding altogether by 60 days, compared with only 3% of women with no breastfeeding concern.

Closer inspection of the 34 women who did not report a breastfeeding concern at day 3, ie, the positive deviants, revealed key characteristics (such as prenatal self-confidence about breastfeeding, youth, unmedicated vaginal birth, and strong breastfeeding support) that seem to serve as protective factors against experiencing breastfeeding concerns that lead to formula use. This is consistent with previous reports indicating that peer counseling22 and birth doula care23 are associated with improved breastfeeding outcomes. Although higher prenatal breastfeeding self-efficacy has been associated with better breastfeeding outcomes,24 in post hoc analysis, higher prenatal breastfeeding self-efficacy did not significantly attenuate the risk of using formula or stopping breastfeeding in relation to the concerns presented in Fig 3 (data not shown).

The concerns we found to be most strongly associated with stopping breastfeeding (infant feeding difficulty and milk quantity concern) are consistent with results of retrospective studies.25–28 For example, in the Infant Feeding Practices Study (II), the top fixed-response reasons mothers gave at 2 months postpartum for having stopped breastfeeding were “my infant had trouble sucking or latching on” and “breast milk alone didn’t satisfy my infant.” In a qualitative study of reasons for in-hospital formula supplementation among low-income mothers of infants under 12 months, DaMota et al29 concluded that new mothers commonly lack understanding about the breastfeeding process; thus, the misinterpretation of appropriate newborn behaviors often leads to maternal requests for infant formula. Breastfeeding concerns articulated by the first-time mothers in our cohort may also have arisen in part from a lack of understanding of normal lactation. In our study, we did not attempt to corroborate mothers’ breastfeeding concerns against clinical indicators. However, regardless of whether maternally reported breastfeeding concerns are congruent with clinical signs, they are strongly associated with breastfeeding outcomes and therefore warrant attention.

Because inquiry into breastfeeding concerns was just 1 question among many we asked at each interview time point, our characterization of some concerns may be underdeveloped as compared with in-depth interviews: maternal concerns may have been broad characterizations or symptoms of an underlying breastfeeding issue, and it is likely that further probing would have provided deeper insight. Also, our participants may have had breastfeeding concerns that they were reluctant to share with the research assistant, reporting what they considered to be socially acceptable responses rather than, for example, concerns about sexuality or body image and breastfeeding.30,31 Nonetheless, for a prospective cohort study of its magnitude (2946 interviews), ours is unique in not relying on fixed responses. In contrast to restricting respondents to categories that may not “fit” the true experience, we were able to develop our categories from open-text responses and, at the same time, have sufficient statistical power to quantitatively examine the category-specific risks associated with breastfeeding outcomes at key time points while accounting for prenatal breastfeeding intention.

Conclusions

Breastfeeding problems were a nearly universal experience in this cohort of first-time mothers. Our results indicate that to effectively support new mothers in meeting their breastfeeding goals, future efforts should consider strengthening the protective factors that reduce the prevalence of breastfeeding concerns and appropriately responding to any concerns that do arise, in particular how the infant feeds at the breast in the early postdischarge period and milk supply concerns lingering into the second week postpartum, as they forewarn of failure to meet breastfeeding goals. Overall, our results reinforce the recommendation of the American Academy of Pediatrics that all breastfed newborns receive an evaluation by a provider knowledgeable in lactation management within 2 to 3 days postdischarge.32

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank our study participants; staff at the UCDMC; University of California, Davis students and staff who contributed to this study; and Jan Peerson for biostatistical support.

Glossary

- ARR

adjusted relative risk

- CI

confidence interval

- OR

odds ratio

- PAR

population attributable risk

- UCDMC

University of California Davis Medical Center

Footnotes

Ms Wagner contributed to the secondary analysis study design, analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafting and revision of the article; Dr Chantry contributed to the acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revisions to the article; Dr Dewey contributed to the study conception and design and critical revisions to the article; Dr Nommsen-Rivers contributed to the study conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting and critical revisions to the article; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by HD063275-01A1 (to Dr Nommsen-Rivers), MC 04294 (to Dr Dewey), and the Perinatal Institute of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: Dr Nommsen-Rivers received a stipend for presenting a continuing education lecture at the National WIC Association meeting in 2012; and Ms Wagner, Dr Chantry, and Dr Dewey, have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding among US children born 2000–2009, CDC National Immunization Survey. Available at: www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis_data/. Accessed August 13, 2013

- 2.Donath SM, Amir LH, ALSPAC Study Team . Relationship between prenatal infant feeding intention and initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a cohort study. Acta Paediatr. 2003;92(3):352–356 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiGirolamo AM, Grummer-Strawn LM, Fein SB. Effect of maternity-care practices on breastfeeding. Pediatrics. 2008;122(suppl 2):S43–S49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perrine CG, Scanlon KS, Li R, Odom E, Grummer-Strawn LM. Baby-Friendly hospital practices and meeting exclusive breastfeeding intention. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):54–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williamson I, Leeming D, Lyttle S, Johnson S. ‘It should be the most natural thing in the world’: exploring first-time mothers’ breastfeeding difficulties in the UK using audio-diaries and interviews. Matern Child Nutr. 2012;8(4):434–447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burns E, Schmied V, Sheehan A, Fenwick J. A meta-ethnographic synthesis of women’s experience of breastfeeding. Matern Child Nutr. 2010;6(3):201–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taveras EM, Capra AM, Braveman PA, Jensvold NG, Escobar GJ, Lieu TA. Clinician support and psychosocial risk factors associated with breastfeeding discontinuation. Pediatrics. 2003;112(1 pt 1):108–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berridge K, McFadden K, Abayomi J, Topping J. Views of breastfeeding difficulties among drop-in-clinic attendees. Matern Child Nutr. 2005;1(4):250–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nommsen-Rivers LA, Chantry CJ, Cohen RJ, Dewey KG. Comfort with the idea of formula feeding helps explain ethnic disparity in breastfeeding intentions among expectant first-time mothers. Breastfeed Med. 2010;5(1):25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nommsen-Rivers LA, Chantry CJ, Peerson JM, Cohen RJ, Dewey KG. Delayed onset of lactogenesis among first-time mothers is related to maternal obesity and factors associated with ineffective breastfeeding. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(3):574–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.The World Health Organization and Unicef. Baby-friendly hospital initiative: revised, updated and expanded for integrated care. 2009. Available at: www.who.int/nutrition/publications/infantfeeding/9789241594950/en/index.html. Accessed August 13, 2013 [PubMed]

- 12.Dennis CL. The breastfeeding self-efficacy scale: psychometric assessment of the short form. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2003;32(6):734–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nommsen-Rivers LA, Dewey KG. Development and validation of the infant feeding intentions scale. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(3):334–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bryant CA, Coreil J, D’Angelo SL, Bailey DF, Lazarov M. A strategy for promoting breastfeeding among economically disadvantaged women and adolescents. NAACOGS Clin Issu Perinat Womens Health Nurs. 1992;3(4):723–730 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chantry CJ, Nommsen-Rivers LA, Peerson JM, Cohen RJ, Dewey KG. Excess weight loss in first-born breastfed newborns relates to maternal intrapartum fluid balance. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/127/1/e171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berg BL. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 7th ed. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Labbok M, Krasovec K. Toward consistency in breastfeeding definitions. Stud Fam Plann. 1990;21(4):226–230 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szklo M, Nieto FJ. Epidemiology: Beyond the Basics. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen; 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kleinman LC, Norton EC. What’s the Risk? A simple approach for estimating adjusted risk measures from nonlinear models including logistic regression. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(1):288–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marsh DR, Schroeder DG, Dearden KA, Sternin J, Sternin M. The power of positive deviance. BMJ. 2004;329(7475):1177–1179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker LO, Sterling BS, Hoke MM, Dearden KA. Applying the concept of positive deviance to public health data: a tool for reducing health disparities. Public Health Nurs. 2007;24(6):571–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson AK, Damio G, Young S, Chapman DJ, Pérez-Escamilla R. A randomized trial assessing the efficacy of peer counseling on exclusive breastfeeding in a predominantly Latina low-income community. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(9):836–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nommsen-Rivers LA, Mastergeorge AM, Hansen RL, Cullum AS, Dewey KG. Doula care, early breastfeeding outcomes, and breastfeeding status at 6 weeks postpartum among low-income primiparae. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2009;38(2):157–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Creedy DK, Dennis CL, Blyth R, Moyle W, Pratt J, De Vries SM. Psychometric characteristics of the breastfeeding self-efficacy scale: data from an Australian sample. Res Nurs Health. 2003;26(2):143–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li RW, Fein SB, Chen J, Grummer-Strawn LM. Why mothers stop breastfeeding: mothers’ self-reported reasons for stopping during the first year. Pediatrics. 2008;122(suppl 2):S69–S76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cernadas JM, Noceda G, Barrera L, Martinez AM, Garsd A. Maternal and perinatal factors influencing the duration of exclusive breastfeeding during the first 6 months of life. J Hum Lact. 2003;19(2):136–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mercer AM, Teasley SL, Hopkinson J, McPherson DM, Simon SD, Hall RT. Evaluation of a breastfeeding assessment score in a diverse population. J Hum Lact. 2010;26(1):42–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahluwalia IB, Morrow B, Hsia J. Why do women stop breastfeeding? Findings from the pregnancy risk assessment and monitoring system. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1408–1412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DaMota K, Bañuelos J, Goldbronn J, Vera-Beccera LE, Heinig MJ. Maternal request for in-hospital supplementation of healthy breastfed infants among low-income women. J Hum Lact. 2012;28(4):476–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hannon PR, Willis SK, Bishop-Townsend V, Martinez IM, Scrimshaw SC. African-American and Latina adolescent mothers’ infant feeding decisions and breastfeeding practices: a qualitative study. J Adolesc Health. 2000;26(6):399–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Archabald K, Lundsberg L, Triche E, Norwitz E, Illuzzi J. Women’s prenatal concerns regarding breastfeeding: are they being addressed? J Midwifery Womens Health. 2011;56(1):2–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eidelman AI, Schanler RJ, Johnston M, et al. Section on Breastfeeding . Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/129/3/e827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.