Abstract

Objective

While needle acupuncture is a well-accepted technique, laser acupuncture is being increasingly used in clinical practice. The differential effects of the two techniques are of interest. We examine this in relation to brain effects of activation of LR8, a putative acupuncture point for depression, using functional MRI (fMRI).

Methods

Sixteen healthy participants were randomised to receive low intensity laser acupuncture to LR8 on one side and needle acupuncture to the contralateral LR8. Stimulation was in an on-off block design and brain patterns were recorded under fMRI.

Results

Significant activation occurred in the left precuneus during laser acupuncture compared with needle acupuncture and significant activation occurred in the left precentral gyrus during needle acupuncture compared with laser acupuncture.

Conclusions

Laser and needle acupuncture at LR8 in healthy participants produced different brain patterns. Laser acupuncture activated the precuneus relevant to mood in the posterior default mode network while needle acupuncture activated the parietal cortical region associated with the primary motor cortex. Further investigations are warranted to evaluate the clinical relevance of these effects.

Introduction

Acupuncture is a popular form of complementary medical intervention used to treat a number of disorders including neuropsychiatric illnesses.1–8 The traditional modality of acupuncture has been with needles applied manually. A number of investigators have examined the possible mechanisms by which needle acupuncture (NA) may produce physiological effects, with many neural structures being implicated including peripheral nerves, neurovascular bundles, mechanoreceptors, nerve endings and neuromuscular attachments.9–18

In the 1970s, with the advent of laser technology, low intensity laser acupuncture (LA) emerged as a new modality of acupuncture and increased in popularity. The main advantages of LA were that it was painless and infection-free because there was no needle puncture. It was also easy to deliver, making it time-efficient and cost-effective. Because of the lack of any skin sensation, low intensity laser was also easy to blind in any experimental design, making it an ideal research tool. In spite of these qualities and its increasing clinical importance, there is a dearth of investigations into its neurophysiological effects and clinical efficacy.19–21 Little is known about the peripheral pathways and spinal and central mechanisms involved in LA.

The application of functional MRI (fMRI) to acupuncture research has opened up an avenue to investigate the CNS effects of the various modalities of acupuncture.22–34 In our previous studies, fMRI was used to examine the brain response to LA on four acupuncture points (LR8, LR14, CV14 and HT7) in both healthy participants and those with depression.35 36 The choice of acupuncture points in the fMRI studies was based on a pilot clinical study to demonstrate the effectiveness of a suite of acupuncture points in the treatment of mild to moderate depression in primary care,8 with LR8 stimulation having produced the most salient effect. These studies showed that the brain activation patterns in depression during LA were different from those in healthy participants, with a significant shift from the frontolimbic cortices to the parieto-temporal-cerebellar regions in those with depression. Another network of interest found with the brain effects of acupuncture is the default mode network (DMN),37 38 also known as the resting state network. The DMN is active when the brain is not involved in any specific task. When the DMN is active, self- referential activity occurs in the resting brain as part of its preparation before the next task.37 38 This self-referential activity is associated with the ‘sense of self’ important in the well-being of the individual.

In this study we chose LR8 (which produced the most salient antidepressant effect in our previous work) to compare the brain effects of the two modalities (LA vs NA) in healthy individuals. We also wanted to record their impact on the DMN.

Methods

Recruitment

Sixteen healthy individuals (eight women and eight men) aged 18–60 years (mean 48.2 years) were recruited by advertisement through the University of New South Wales, Black Dog Institute and a private medical acupuncture clinic in Sydney.

Study design

Each participant received LA on the medial knee acupuncture point LR8 (at the junction of the semitendinosus and semimembranosus tendon insertion site above the knee) and NA at LR8 on the other leg, with the side of stimulation being counterbalanced across the group; in other words, for the whole sample there was equivalent left- and right-sided stimulation with NA and LA.

During the fMRI scan, two runs were used for either LA or NA condition in randomised order. Each run had alternating rest/active phases, beginning with a rest phase, and consisted of 17 blocks with eight active phases (block) alternating with nine rest phases (block). The duration of each active block was 20 s, including 2 s preparation time, 16 s of continuous acupuncture stimulation and 2 s of repetition time (TR) at the end for the scanner to pick up the BOLD signal. The rest block was set at 20 s to match the active block. Both laser stimulation and needle stimulation were time-locked to signalling.

Inclusion criteria

Participants were right-handed, had no history of significant medical or psychiatric disorder, were not currently on any medication other than vitamin supplements, had no contraindications to an MRI scan and provided written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria included ongoing uncontrolled systemic illness, acute illness, brain injury, past surgery involving the lower limbs and any contraindications to MRI (pacemaker, ferromagnetic implants or foreign body, claustrophobia).

Withdrawal criteria

Subjects were withdrawn if any of the abovementioned exclusion criteria occurred in the interim before the procedure or if the subject became agitated or anxious during the procedure.

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation has been described above in the study design. There was no blinding of either the participant or the acupuncturist. The block (rest/active) design accommodated for the placebo response to both needle and laser stimulation.

Intervention

Practitioner background

LA and NA were conducted by IQ-S and TL. IQ-S is a Fellow of the Australian Medical Acupuncture College (AMAC) and has been a clinical acupuncturist for 20 years. TL has expertise in integrative neurophysiology and is a rehabilitation medicine specialist.

The needle

Single usage Helio-sourced non-ferrous silver needles with dimensions 0.22 mm×25 mm, which are compatible with the magnet, were used. The location of LR8 was confirmed by anatomical landmarks and needle puncture was followed by rotation in 1 Hz cycles in a 45 degrees clockwise direction to produce the de qi sensation typical of manual acupuncture while undergoing MRI acquisition. The needling blocks were achieved with time-lock to signalling for MRI acquisition.

The laser

A Moxla prototype fibreoptic infrared light laser (Euryphaessa AB, Stockholm, Sweden), 808 nm with 20 mW capacity and a fibreoptic arm was developed for use in the scanning room. Location was confirmed by anatomical location. A stably-held laser was applied to the skin by the acupuncturist for the duration of the laser session according to the time signal. The switching on and off was achieved with a computer signal time-locked to the MRI acquisition.

Sensory stimulation reporting

After the acupuncture intervention under fMRI acquisition the participants were each asked to assess the sensory stimulation they underwent; the sensory descriptions were light touch, pressure, fullness, heaviness, ache, soreness, numbness, tingling, warmth, pain and ‘other’.

fMRI

Imaging was performed on a 3T Philips Intera MRI scanner (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands) for both T1-weighted three-dimensional (3D) structural and BOLD contrast functional MRI. The 3D structural MRI was acquired in sagittal orientation using a T1-weighted TFE sequence (TR/TE=6.39/2.9 ms; flip angle=8; matrix size=256×256; FOV=256×256 mm; slice thickness 1.0 mm), yielding sagittal slices of 1.0 mm thick and an in-plane spatial resolution of 1.0×1.0 mm, producing an isotropic voxel of 1.0×1.0×1.0 mm. A gradient echo-planar imaging (EPI) technique (TR/TE=2000/40 ms; matrix size=128×128; FOV=250×250 mm; in-plane pixel size 1.953×1.953 mm) was used to acquire T2-weighted BOLD contrast fMRI in axial orientation. The whole brain was covered using 21 slices at 5.0 mm slice thickness.

Image preprocessing

Imaging data were analysed using statistical parametric mapping (SPM2, Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK) implemented in Matlab V.6 (The Mathworks). All volumes were realigned spatially to the first volume and the time series for voxels within each slice realigned temporally to acquisition of the middle slice. Resulting volumes were normalised to a standard EPI template based on the MNI. The normalised images were smoothed with an isotropic 8 mm full-width half-maximal Gaussian kernel. The time series in each voxel was highpass filtered to 1/120 Hz to remove low-frequency noise.

Image postprocessing

Statistical analysis was performed in two stages assuming a random effects design. Each stimulation site was compared with the rest condition for first-level analysis. The BOLD response to the acupuncture stimulation was modelled by a canonical haemodynamic response function (HRF).

Half the participants’ images were flipped and the group was then processed as a whole under second-level analysis (ANOVA) at the whole brain level. Each individual participant's contrast images, which were effectively the statistical parametric maps of the t-statistics for each voxel from the first-level analysis, were put into this second-level design. We used a one-sample t test to examine the activation pattern of each acupuncture group and a within-subject two-sample t test to compare the activation differences between the two types of acupuncture. To correct for multiple comparisons, areas with a p value<0.05 following cluster-level Family Wise Error (FWE) correction were considered significant, with an initial uncorrected p value threshold of <0.001 and the extent threshold to 15 contiguous voxels.

Results

First-level analysis

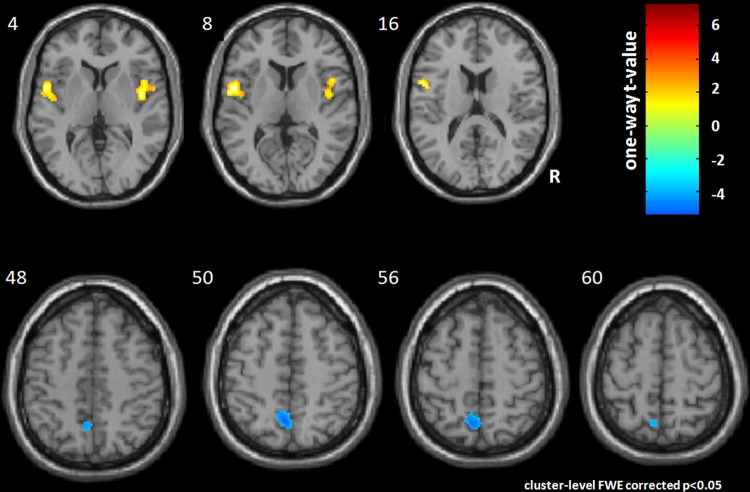

NA at LR8 showed increased activation at the right insula (pFWE=0.001) and left precentral gyrus and insula (pFWE<0.001) (figure 1, table 1). There was also deactivation at the left precuneus (pFWE=0.002). No significant results were found for LA acupuncture at LR8, indicating that there was no consistent activation or deactivation at the first level.

Figure 1.

A one-sample t test was used to show the activation pattern of needle acupuncture. Significant activation (p<0.05) corrected (Family Wise Error) was found at the bilateral insula and left precentral gyrus as well as deactivation at the left precuneus.

Table 1.

First-level analysis relative to resting state: significant results for NA

| k | pFWE | Regions | MNI coordinates | T | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | y | z | |||||

| Activation | |||||||

| Cluster 1 | 426 | <0.001 | L insula | −54 | 4 | 10 | 7.29 |

| L precentral gyrus | −48 | 2 | 18 | 5.86 | |||

| Cluster 2 | 229 | 0.001 | R insula | 44 | −6 | 6 | 6.12 |

| Deactivation | |||||||

| Cluster 3 | 197 | 0.002 | L precuneus | −4 | −52 | 54 | |

FWE, family wise error; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; NA, needle acupuncture; T, T value for t-test.

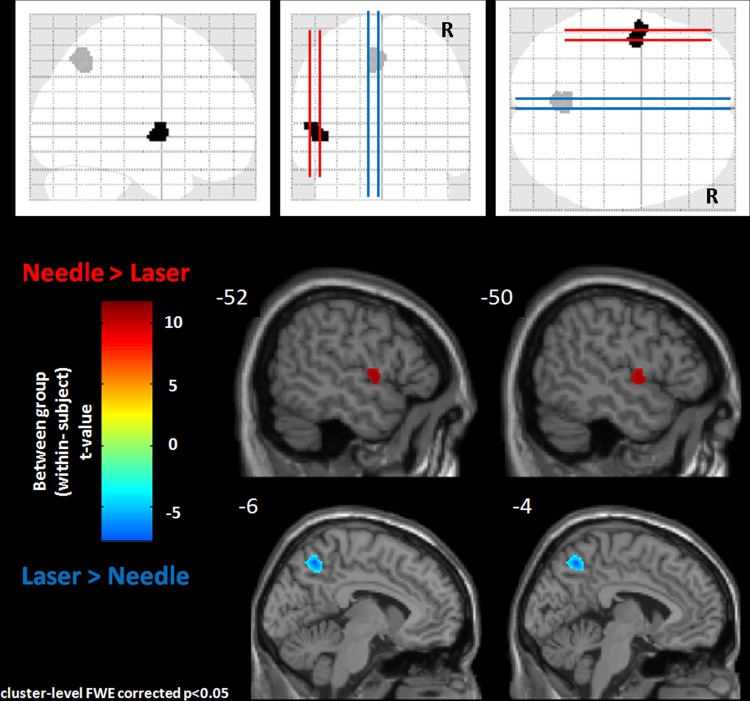

Second-level analysis

When the activation patterns for LA and NA were compared, NA produced greater activation in the left precentral gyrus (pFWE=0.023) and LA produced more activation in the left precuneus (pFWE=0.003) (figure 2, table 2).

Figure 2.

A within-subject t test was used to show differences in activation between needle acupuncture and laser acupuncture. Needle acupuncture activated the left precentral gyrus while laser acupuncture activated the left precuneus. All the results have been corrected for multiple comparison error.

Table 2.

Second-level analysis: significant activation differences between NA and LA

| Regions | MNI coordinates | k | pFWE | T | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x | Y | z | ||||

| Needle>laser | ||||||

| L precentral gyrus | −56 | −2 | 8 | 119 | 0.023 | 4.95 |

| Laser>needle | ||||||

| L precuneus | −6 | −56 | 44 | 174 | 0.003 | 3.73 |

FEW, family wise error; LA, laser acupuncture; NA, needle acupuncture.

Sensory stimulation: laser versus needle

All participants felt the touch of the laser probe but only a few reported any sensation produced by the laser beam itself, with three reporting a tingling sensation, one a feeling of warmth and one reporting both these sensations. Needle acupuncture with de qi produced more sensory changes, with all participants reporting pressure and tingling and three reporting pain (see online appendix, supplementary tables S1 and S2).

Adverse effects: laser and needle acupuncture, MRI experience

On a scale of 0 (none) to 6 (severe), mean scores of adverse effects with LA were: transient tiredness and dizziness (0.13), vagueness (0.125) and nausea (0.06). Adverse effects with NA were: pain (0.50) and unwell (0.13). The MRI experience caused mild discomfort (0.44) and anxiety (0.44) (see online appendix, supplementary table S3).

Discussion

Functional MRI studies with NA have indicated that deactivation of the limbic-paralimbic-neocortical network and activation of the somatosensory cortex are involved during NA intervention. Deactivation of the limbic system occurs with correct de qi needling technique, whereas poor technique resulting in the pain sensation causes the opposite reaction (activation of the limbic system). Some of the limbic-paralimbic regions were identifiable as being part of the DMN.12 13 22 23 These studies have selected acupuncture points which are clinically known to be uncomfortable when de qi needling is applied (eg, LI4 and ST36). The insula is involved in NA and our first-level findings confirmed those in the literature.12 13 27–34 The limited literature on the brain effects of LA suggests limbic-paralimbic-neocortical activation but no significant activation of the somatosensory cortex.20 21 Ipsilateral brain activation was also observed. One study on healthy participants reported that this ipsilaterality was only seen with limb acupuncture points and not truncal acupuncture points.35 The ipsilaterality suggests the involvement of the autonomic nervous system in LA mechanisms of action. There was no significant activation or deactivation of the somatosensory cortex, with the low intensity laser stimulation being free of pain or ache. This may contribute to the interindividual variability in the first-level analysis with LA while first-level analysis with NA demonstrated significant activation of the insula, important in pain pathways and deactivation of the posterior DMN. Unlike previous NA studies reporting somatosensory cortical changes, the precentral gyrus linked to the primary motor cortex was activated. The above literature therefore suggests that the NA and LA acupuncture afferent pathways may be different, the former due to its somatosensory and sensorimotor input following afferent pain pathways9 10 and the latter possibly more autonomically driven.19 35 36

The literature shows that both NA and LA modulate the DMN. The DMN is a composite of brain regions activated when the brain is at rest and not involved in an active task. It is therefore also referred to as the task negative brain network. During DMN time the healthy individual reflects on his or her life and his or her hopes and aspirations.39 It may be that activation of the DMN is responsible for the feeling of well-being from acupuncture intervention. Some may argue the case that the well-being is from the placebo effect. The DMN may be an integral part of every acupuncture intervention, directly contributing to the maintenance of ‘sense of self’ and well-being.37 40

The posterior DMN is important in depression.40 41 LR8 is the most important acupuncture point in the LA treatment regime for depression that was tested in our previous work.35 The significant activation of the left precuneus (as part of the posterior DMN) after FWE correction when LA is applied to LR8 across the group in the second-level analysis is further confirmation of the clinical efficacy of LA in depression.8 In NA, deactivation of the left precuneus was noted at the first-level analysis, confirming the deactivation of this part of the posterior DMN. This could be part of an antidepressant effect of NA at LR8. Further needle fMRI acupuncture studies are needed to confirm the efficacy of this acupuncture point in depression.

In the first-and second-level analyses, measuring activation less than or greater than a baseline (in this case, rest) are referred to as deactivation and activation, respectively. However, in this study, for second-level analysis, deactivation is impossible to interpret as we are subtracting two tasks from each other (NA vs LA) and not comparing them with rest. We found that NA significantly stimulated the left precentral gyrus compared with LA, and the latter significantly activated the left precuneus compared with the former. It is not known why the left precentral gyrus in NA and the left precuneus in LA are stimulated for these modalities in this comparison. In the protocol it was ensured that equivalent numbers of left- and right-sided NA and LA were conducted. The left-sidedness may be limited to our sample alone. Further studies may be required to clarify the brain functions of LR8 when stimulated by different modalities of acupuncture.

Interestingly, in spite of NA at this acupuncture point using the de qi method to cause the traditional ‘achy’ sensation, there was no significant stimulation of the somatosensory cortex (represented as the post-central gyrus). Instead, NA at LR8 produced significant activation at the precentral gyrus after FWE correction. The precentral gyrus is an important region which includes the motor cortical regions42 (primary motor or somatomotor cortex and the lateral premotor cortex). Previously, sensorimotor implicated acupuncture points (GB34, GB35, GB39, ST36 on the leg and LI9, LI10, LI13, LI14 on the arm) have been shown to increase brain activation of the premotor and supplementary motor regions.43 Another study showed that NA at GB34/BL57 caused deactivation of the primary motor cortex and premotor cortex.44 The findings of NA at LR8 in this study are only preliminary fMRI evidence. More investigations are warranted to evaluate the role of NA at LR8 in the modulation of motor cortical regions and hence its likely usefulness in motor rehabilitation clinically.

Empirically, LR8 is not particularly uncomfortable or painful when needled to produce the de qi sensation, unlike widely investigated acupuncture points ST36 or LI4 which are known to be uncomfortable to similar needling. This observation suggests that maybe not all acupuncture points produce somatosensory changes when needled.12 25 In the case of LR8, the outcome from this study is that NA at this acupuncture point is significantly somatomotor. In the literature, among its applications, LR8 is empirically used for muscle spasms, pareses and paretic tendencies.45 Classically, it is meant to ‘benefit the sinews’. It would be interesting to perform further work on other mid lower limb acupuncture points to test their sensorimotor implications.

The sensory signalling (if any) perceived by the participants from LA was light touch (for all participants) and tingling and/or warmth (n=2), and only one participant felt pressure. Warmth being C fibre-linked and light touch and tingling being more so, A-β linked sensations may be part of LA's afferent fibres. Evaluation of the sensory signalling with NA showed that pressure and tingling (n=10) were felt by more participants than light touch (n=6) or ache (n=5). Interestingly, with LA all of the participants felt light touch and only three participants felt anything more than light touch. This may suggest an A-β and possibly non-nociceptive C afferent involvement with LA, whereas NA probably sets up activity in A-β, A-δ and C fibres (nociceptive as well as non-nociceptive).9 46 More investigations are warranted to identify definitively the afferent fibre types involved in LA.

There are limitations to these findings. They may be confined to this low intensity laser (808 nm). Although we had 16 participants, this is still a relatively small sample size. This study was conducted on healthy participants and NA or LA at LR8 may produce totally different brain patterns in participants with health problems.

Conclusion

NA and LA at LR8 produce different brain patterns, highlighting the differential application of these two modalities of acupuncture. These activation patterns are consistent with the suggestion that LA at LR8 may be useful in the treatment of mood disorders while NA at LR8 may be useful in the modulation of motor cortical regions and hence may have a place in motor rehabilitation. These are only preliminary findings and further investigations with larger samples are warranted.

Summary points.

Laser and needle acupuncture at LR8 significantly activated different brain regions.

Laser acupuncture activated the precuneus, part of the posterior default mode network.

Needle acupuncture activated the precentral gyrus, part of the motor cortical brain regions and not the sensory cortical brain regions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Helio Australia for supplying the MRI friendly silver needles. Thanks to all our participants for their time and contribution, to Julie-Ann Ho for their recruitment and to Kate Bromley and Beverley Stanton for their help in laser signalling.

Footnotes

Contributors: IQ-Sdesigned and managed the study, recruited participants, conducted the laser/needle intervention under fMRI, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. MW helped with study design and data analysis. TL conducted the laser/needle intervention under fMRI and helped with writing the manuscript. CS analysed the data and helped with writing the manuscript. PS contributed to the study design, ethical application and writing the manuscript.

Funding: This project was funded by Thyne Reid Foundation and Louise Dobson and family. We thank them for their support.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee, South East Health, South Eastern Illawarra Area Health Service, Sydney, Australia.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We are happy to discuss data sharing as approved by the senior author Professor Perminder Sachdev.

References

- 1.Smith CA, Hay PPJ, MacPherson H. Acupuncture for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010;1:2–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li C, Huang Y, Li Y, et al. Treating post stroke depression with mind refreshing antidepressant acupuncture therapy. Int J Clin Acupunct 1994;5:389–93 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen J, Hitt SK, Schnyer RN. The efficacy of acupuncture in the treatment of major depression in women. Psychol Sci 1998;9:397–401 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han C, Li XW, Luo HC. Comparative study of electroacupuncture and maprotiline in treating depression. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi 2002;22:512–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo H, Menh F, Jia Y, et al. Clinical research on the therapeutic effect of electroacupuncture treatment in patients with depression. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 1998;52(Suppl):338–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song YQ, Zhou DF, Fan JH, et al. Effects of electroacupuncture and fluoxetine on the density of GTP-binding-proteins in platelet membrane in patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord 2007;98:253–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallagher SM, Allen JJ, Hitt SK, et al. Six-month depression relapse rates among women treated with acupuncture. Complement Ther Med 2001;9:216–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quah-Smith JI, Tang WM, Russell J. Laser acupuncture for mild to moderate depression in a primary care setting—a randomised controlled trial. Acupunct Med 2005; 23:103–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okada K, Kawakita K. Analgesic action of acupuncture and moxibustion: a review of unique approaches in Japan. eCAM 2009;6:11–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White A, Cummings M, Barlas C, et al. Defining an adequate dose of acupuncture using a neurophysiological approach—a narrative review of the literature. Acupunct Med 2008;26:111–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lundeberg T, Lund I, Naslund J. Acupuncture—self-appraisal and the reward system. Acupunct Med 2007;25:87–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hui KK, Liu J, Napadow V, et al. The integrated response of the human cerebro-cerebellar and limbic systems to acupuncture stimulation at ST 36 as evidenced by fMRI. NeuroImage 2005;27:479–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Napadow V, Kettner NW, Liu J, et al. Hypothalamus and amygdala response to acupuncture stimuli in carpal tunnel syndrome. Pain 2007;130:254–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haker E, Egevist H, Bjerring P. The effect of sensory stimulation (acupuncture) on symp and parasymp activities in healthy subjects. J Auton Nerv Syst 2000;79:52–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.You Y, Bai L, Dai R, et al. Differential neural responses to acupuncture revealed by MEG using wavelet-based time-frequency analysis: a pilot study. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2011;2011:7099–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Streitberger K, Ezzo J, Schneider A. Acupuncture for nausea and vomiting: an update of clinical and experimental studies. Auton Neurosci 2006;129:107–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ezzo J, Streitberger K, Schneider A. Cochrane systematic reviews examine P6 acupuncture-point stimulation for nausea and vomiting. J Altern Complement Med 2006;12:489–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macpherson H, Hammershlag R, Lewith G, et al. Acupuncture research—strategies for establishing an evidence base. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2008:133–50 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baxter D, Bleakley C, McDonough SM. Clinical effectiveness of LA: a systematic review. J Acupunct Merid Studies 2008; 1:65–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siedentopf CM, Koppelstaetter F, Haala IA, et al. Laser acupuncture induced specific cerebral cortical and subcortical activations in humans. Lasers Med Sci 2005;20:68–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siedentopf CM, Golaszewski SM, Mottaghy FM, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging detects activation of the visual association cortex during laser acupuncture of the foot in humans. Neurosci Lett 2002;327:53–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hui K, Marina O, Claunch JD, et al. Acupuncture mobilizes the brain's default mode and its anticorrelated network in healthy subjects. Brain Res 2009;1287:84–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hui K, Marina O, Liu J, et al. Acupuncture, the limbic system and the anticorrelated networks of the brain. Auton Neurosci 2010;157:81–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Napadow V, Makris N, Liu J, et al. Effects of electroacupuncture versus manual acupuncture on the human brain as measured by fMRI. Hum Brain Mapp 2005;24:193–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsieh JC, Tu CH, Chen FP, et al. Activation of the hypothalamus characterises the acupuncture stimulation at the analgesic point in the human: a PET Study. Neurosci Lett 2001;307:105–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoo SS, The EK, Blinder RA, et al. Modulation of cerebellar activities by acupuncture stimulation: evidence from fMRI study. NeuroImage 2004;22:932–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kong J, Gollub RL, Webb JM, et al. Test-retest study of fMRI signal change evoked by electroacupuncture stimulation. NeuroImage 2007;34:1171–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Napadow V, Dhond RP, Purdon P, et al. Correlating acupuncture fMRI in the human brain stem with heart rate variability. Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology 27th Annual Conference; Shanghai, Sept 1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu MT, Hsieh JC, Xiong J, et al. Central nervous system pathway for acupuncture stimulation: localisation of processing with fMRI of the brain. Radiology 1999;212:133–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fang JL, Krings T, Weidemann J, et al. Functional MRI in healthy subjects during acupuncture: different effects of needle rotation in real and false acupoints. Neuroradiology 2004;46:359–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang WT, Jin Z, Cui GH, et al. Relations between brain network activation and analgesic effect induced by low vs high frequency electrical acupoint stimulation in different subjects: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Brain Res 2003;982:168–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geng Li, Clifford RJ, Yang ES. An fMRI study of somatosensory implicated acupuncture points in stable somatosensory stroke patients. J Magn Reson Imaging 2006;24:1018–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Qin W, Bai L, Yang L, et al. FMRI connectivity analysis of acupuncture effect on an amygdala-associated brain network. Mol Pain 2008;4:1–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dhond RP, Yeh C, Park KY, et al. Acupuncture modulates resting state connectivity in default and sensorimotor brain networks. Pain 2008;136:407–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quah-Smith I, Sachdev P, Wen W, et al. The brain effects of laser acupuncture in healthy individuals: a functional MRI investigation. PLoS One 2010;5:e12619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quah-Smith I, Wen W, Chen X, et al. The brain effects of laser acupuncture in depressed individuals: an fMRI investigation. Med Acupunct 2012;24:161–71 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sheline YI, Barch DM, Price JL, et al. The default mode network and self-referential processes in depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:1942–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain's default network: anatomy, function and relevance to disease. Ann NY Acad Sci 2008;1124:1–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mason MF, Norton MI, Van Horn JD,, et al. Wandering minds: the default network and stimulus independent thought. Science 2007;315:393–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berman MG, Peltier S, Nee DE,, et al. Depression, rumination and the default mode network. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2011;6:548–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fransson P, Marrelec G. The precuneus/posterior cingulate cortex plays a pivotal role in the default mode network: evidence from a partial correlation network analysis. NeuroImage 2008;42:1178–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Meier JD, Afialo TN, Kastner S,, et al. Complex organization of the human primary motor cortex: a high-resolution fMRI study. J Neurophysiol 2008;100:1800–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li G, Huang L, Cheung RTF,, et al. Cortical activations upon stimulation of the sensorimotor- implicated acupoints. Magn Reson Imaging 2004;22:639–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang WT, Jin Z, Luo F,, et al. Evidence from brain imaging with fMRI supporting functional specificity of acupoints in humans. Neurosci Lett 2004;354:50–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hempen CH, Chow VW. Pocket Atlas of Acupuncture. Acupuncture points of the main channel of the liver. Stuttgart, New York: Thieme, 2006: 223 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kagitani F, Uchida S, Hotta H. Afferent nerve fibres and acupuncture. Auton Neurosci 2010;157:2–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.