Abstract

We examined the ability of HIV-1 subtype C to develop resistance to the inhibitory lectins, griffithsin (GRFT), cyanovirin-N (CV-N) and scytovirin (SVN), which bind multiple mannose-rich glycans on gp120. Four primary HIV-1 strains cultured under escalating concentrations of these lectins became increasingly resistant tolerating 2 to 12 times their 50% inhibitory concentrations. Sequence analysis of gp120 showed that most had deletions of 1 to 5 mannose-rich glycans. Glycosylation sites at positions 230, 234, 241, 289 located in the C2 region and 339, 392 and 448 in the C3-C4 region were affected. Furthermore, deletions and insertions of up to 5 amino acids in the V4 region were observed in 3 of the 4 isolates. These data suggest that loss of glycosylation sites on gp120 as well as rearrangement of glycans in V4 are mechanisms involved in HIV-1 subtype C escape from GRFT, CV-N and SVN.

Keywords: Griffithsin, Cyanovirin-N, Scytovirin, HIV subtype C, resistance, entry inhibitor, glycans, single genome amplification, microbicide

INTRODUCTION

The surface of the HIV-1 envelope is populated with glycans that play an important role in protecting neutralization sensitive epitopes, promoting gp120 structural integrity and mediating interaction with cellular receptors (Geijtenbeek and Gringhuis, 2009; Li et al., 1993; Lin et al., 2003; Liu et al., 2004; Losman et al., 2001; Lue et al., 2002; Wei et al., 2003; Zhu et al., 2000). The majority of glycans on the HIV-1 envelope trimer are mannose-rich comprising 7 to 9 terminal mannose residues (Bonomelli et al.; Doores et al.) although the precise number and location remains undetermined. Complex glycans with terminal sialic acid residues are likely also present (Leonard et al., 1990). Mannose-rich glycans are targets for lectins or carbohydrate binding agents (CBAs) such as griffithsin (GRFT), cyanovirin-N (CV-N) and scytovirin (SVN) isolated from naturally occurring algae (Bokesch et al., 2003; Boyd et al., 1997; Mori et al., 2005; Moulaei et al., 2007; Ziolkowska and Wlodawer, 2006). These lectins show potent and broad anti-HIV-1 activities in vitro and are, therefore, being investigated for use in HIV-1 prevention, mostly in the form of microbicides (Balzarini, 2005; Ferir et al., 2012; O’Keefe et al., 2009; Tsai et al., 2004; Tsai et al., 2003).

Since the neutralization activity of lectins involves interaction with glycans, one potential mechanism of HIV-1 escape from these compounds is the deletion of glycosylation sites. Indeed studies on HIV-1 subtype B have shown deletion of mannose-rich glycans is a mechanism of resistance to CV-N (Balzarini et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2007). More specifically, a loss of mannose-rich glycans at positions 230, 289, 295, 332, 339, 386, 392 and 448 was associated with resistance in the laboratory-adapted strains HIV-1IIIB and HIV-1NL-4.3 (Balzarini et al., 2006). In another study, the deletion of these glycans excluding those at positions 230 and 386 in HIV-1IIIB cultured under escalating concentrations of CV-N, resulted in resistance to the lectin (Hu et al., 2007). In addition, HIV-1 resistance to the lectins Galanthus nivalis agglutinin and Hippeastrum hybrid agglutinin, was reported to occur via a partial loss of glycans on the envelope (Balzarini et al., 2005; Balzarini et al., 2004). Resistance to the broadly neutralizing antibody 2G12, that targets glycans on gp120, also involves the deletion of mannose-rich glycans. This is supported by the fact that most subtype C viruses are resistant to this antibody due to their lack of the 295 glycosylation site (Binley et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2005; Gray et al., 2007; Manrique et al., 2007).

The glycosylation pattern on the HIV-1 subtype C envelope differs from subtype B (Zhang et al., 2004), and the ability of these viruses to develop resistance to lectins is unknown. In the current study we describe the mechanism of resistance to CV-N among four subtype C primary viruses, which while similar to subtype B showed some differences. This involved the deletion of mannose-rich glycans on gp120 as well as 4–5 amino acids deletions or insertions in the V4 region. In addition, we studied HIV-1 escape from two other lectins, GRFT and SVN, and showed that it followed a similar pathway to CV-N although patterns varied between the lectins. Thus, changes of glycosylated and non-glycosylated amino acid sequences suggest multiple mechanisms of escape from these three lectins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses, cell lines, lectins and antibodies

The R5 infectious HIV-1 subtype C viruses Du151 and Du422 were isolated from acute infections while the R5X4 Du179 was isolated from a chronic infection in South Africa (Williamson et al., 2003); COT9 is a R5 isolate from a chronically infected pediatric patient (Choge et al., 2006). These four primary isolates were chosen because they are well characterized. Furthermore, Du151, Du422 and Du179 were previously selected as HIV-1 vaccine strains since they represented the HIV-1 subtype C epidemic (Williamson et al., 2003). The pSG33env plasmid was provided by Dr. Beatrice Hahn. The TZM-bl cell line was from the NIH Reference and Reagent Program (Cat No 8129) and the 293T cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. These two cell lines were cultured in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Cell monolayers were disrupted at confluence by treatment with 0.25% trypsin in 1 mM EDTA. Recombinant GRFT, CV-N and SVN were purified from E. coli at the National Cancer Institute, MD, USA (Bokesch et al., 2003; Boyd et al., 1997; Mori et al., 2005). The PGT and b12 antibodies were kindly provided by D. Burton and W. Koff of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative. VRC01 was obtained from the Vaccine Research Centre (Bethesda, MD) while the soluble CD4 was a generous gift from Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Tarrytown, NY).

Selection of GRFT, CV-N and SVN resistant viruses

One thousand TCID50 of each HIV-1 subtype C infectious isolate were grown under escalating concentrations of GRFT, CV-N and SVN. Viruses were cultured in 2 mL of 4 × 106 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), depleted of CD8+ T cells by means of RosetteSep CD8 depletion cocktail (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). The starting concentrations of the lectins were the IC50 (50% inhibitory concentration) for each virus. Cultures without lectins were included as experimental controls. All cultures were maintained in RPMI 1640 containing 20% FBS and IL-2 (0.05 μg/mL). Viruses were passaged every 7 days by transferring 500 μL of the previous culture into fresh CD8 depleted PBMC. The concentration of GRFT, CV-N and SVN was increased whenever the p24 antigen level in the lectin containing cultures was similar or higher than the control cultures without lectin. When p24 levels dropped the lectin concentration was reduced. After every passage 500 μL aliquots of culture supernatants were stored at −70°C for genotyping and neutralization assays.

HIV-1 neutralization assay in peripheral blood mononuclear cells

The PBMC neutralization assay was performed as described (Bures et al., 2000). Briefly, a three-fold dilution series of GRFT, CV-N, and SVN in 40 μL of RPMI 1640 containing 20% FBS and IL-2 (growth medium) was prepared in triplicate in a U-bottom 96-well plate. Five hundred TCID50 of the HIV-1 isolate in 15 μL of growth medium was added to each well and the plate was incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. This was followed by the addition of 5 × 105 cells/well/100 μL of phytohemagglutin/IL-2 stimulated PBMC (PHA-PBMCs). After an overnight incubation, cells were washed 3 times with RPMI 1640 containing 20% FBS and resuspended in 155 μL of fresh growth medium. The culture supernatant was collected twice daily and replaced with an equal amount of fresh growth medium. The p24 antigen concentration in the virus control wells was measured by ELISA using the Vironostika HIV-1 Antigen Microelisa System (Biomerieux, Boseind, the Netherlands). Levels of p24 in the lectin cultures were measured at the time-point corresponding to the early part of the linear growth period of the virus control (Zhou and Montefiori, 1997). The 80% inhibitory concentrations (IC80) were calculated by plotting the lectin concentration versus the percentage inhibition in a linear regression using GraphPad Prism 4.0 and the transformation Y = b + mX.

HIV-1 envelope amplification and sequencing

HIV-1 RNA was extracted from frozen culture supernatants and reverse transcribed to cDNA using the Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, CA). For both the single genome amplification (SGA) and the total population amplification, the envelope gene PCR was carried out as described by Salazar-Gonzalez et al. (Salazar-Gonzalez et al., 2008). The PCR products were gel purified using the Qiagen Gel Purification Kit according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Hilden, Germany), sequenced using the ABI PRISM Big Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and resolved on an automated genetic analyzer. Changes in the envelopes sequences were identified using Sequencher v.4.5 (Genecodes, Ann Arbor, MI), Clustal X (ver. 1.83) and Bioedit (ver. 5.0.9).

Generation of mutants Env-pseudotyped virus stock

Glycosylation sites and amino acid deletions and insertions associated with GRFT, CV-N and SVN resistance were introduced in HIV-1 envelope clones using the QuikChange Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, LaJolla, CA). Primers were designed to insert or remove potential glycosylation sites and indels in a stepwise fashion and were confirmed by sequencing as described above. HIV-1 pseudoviruses were generated by co-transfection of the Env and pSG33env plasmids (Wei et al., 2003) into 293T cells using the Fugene transfection reagent (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN). This was followed by the quantification of the TCID50 of each virus stock by infecting TZM-bl cells with serial 5-fold dilutions of the supernatant in quadruplicate in the presence of DEAE dextran (37.5 μg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). After 48 hours of culture, HIV-1 infection was measured using the Bright Glo™ Reagent (Promega, Madison, WI), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence was quantified in a Wallac 1420 Victor Multilabel Counter (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, CT) and the TCID50 was calculated as described elsewhere (Johnson and Byington, 1990).

Single cycle neutralization assay (TZM-bl assay)

The pseudovirus neutralization assay was carried out as described previously (Montefiori, 2004). Briefly, three-fold dilution series of GRFT, CV-N and SVN in 100 μL of DMEM with 10% FBS (growth medium) were prepared in a 96-well plate in duplicate. This was followed by the addition of 200 TCID50 of pseudovirus in 50 μL of growth medium and the mixture was incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Then 100 μL of TZM-bl cells at a concentration of 1 × 105 cells/mL in 10% FBS DMEM containing 37.5 μg/mL of DEAE dextran was added to each well and the plate was placed at 37°C for 48 hours. HIV-1 infection was evaluated by measuring the activity of firefly luciferase. Titers were calculated as the inhibitory concentration that causes 50% reduction (IC50) of relative light unit (RLU) compared to the virus control (wells with no inhibitor) after the subtraction of the background (wells without both the virus and the inhibitor).

RESULTS

Replication of HIV-1 subtype C isolates in the presence of sub-inhibitory concentrations GRFT, CV-N and SVN

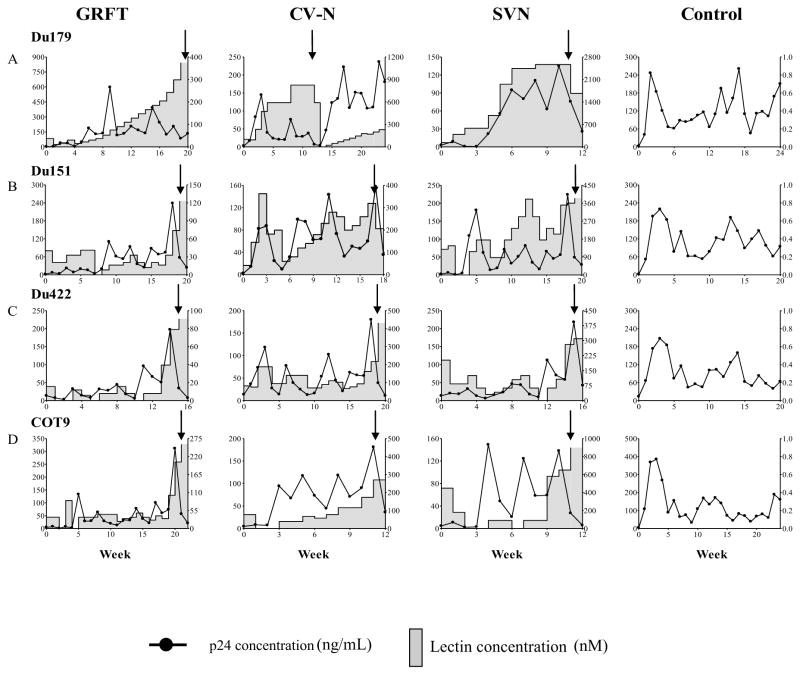

HIV-1 subtype B has previously been shown to develop resistance after repeated passages in the presence of escalating concentrations of CV-N (Balzarini et al., 2005; Balzarini et al., 2004; Hu et al., 2007; Witvrouw et al., 2005). Since the glycosylation pattern of HIV-1 envelope differs by subtype (Zhang et al., 2004), we determined the ability of viruses from subtype C to develop resistance to CV-N and two other lectins, GRFT and SVN. Four subtype C primary isolates were cultured in CD8 depleted PBMC in the presence of increasing lectin concentrations for 11 to 22 weeks, starting with the concentration equal to the IC50 for each compound (Table 1). Viral growth was measured weekly by p24 antigen ELISA. When the p24 levels in the lectin-containing cultures were lower than the control cultures (containing no lectin), the lectin concentrations were reduced in order to facilitate ongoing replication (Figure 1). Of all four isolates, Du179 showed the highest levels of resistance, tolerating at least 10 times the starting concentration of each lectin (Table 1). The other 3 viruses, Du151, Du422 and COT9 grew at 3 times the starting concentrations of GRFT and SVN and 5 times the starting concentration of CV-N. Altogether, these data showed that the continuous growth of these four HIV-1 subtype C viruses under lectin selective pressure resulted in their ability to tolerate higher concentrations suggesting a level of resistance to these compounds.

Table 1.

IC50 values of GRFT, CV-N and SVN for the neutralization of HIV-1 isolates

| Virus | Pre-selection a IC50 (nM) | Fold increase after selection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRFT | CV-N | SVN | GRFT | CV-N | SVN | |

| Du179 | 37.8 | 102.2 | 134.1 | 10 | 10 | 12 |

| Du151 | 40.3 | 41.2 | 128.5 | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| Du422 | 39.5 | 82.1 | 215.6 | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| COT9 | 85.8 | 77.1 | 449.5 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

50% inhibitory concentration.

Figure 1. In vitro generation of GRFT, CV-N and SVN resistant viruses.

Primary HIV-1 subtype C isolates Du179 (A), Du151 (B), Du422 (C) and COT9 (D) were cultured in PBMC under escalating concentrations of GRFT, CV-N and SVN. The concentration of each lectin was gradually increased or reduced depending on the viral growth compared to the control cultures (containing no lectin) as determined by p24 antigen ELISA. The arrows indicate the time-point that the supernatant was collected for analysis.

Lectin-selected isolates showed decreased sensitivity and cross-resistance

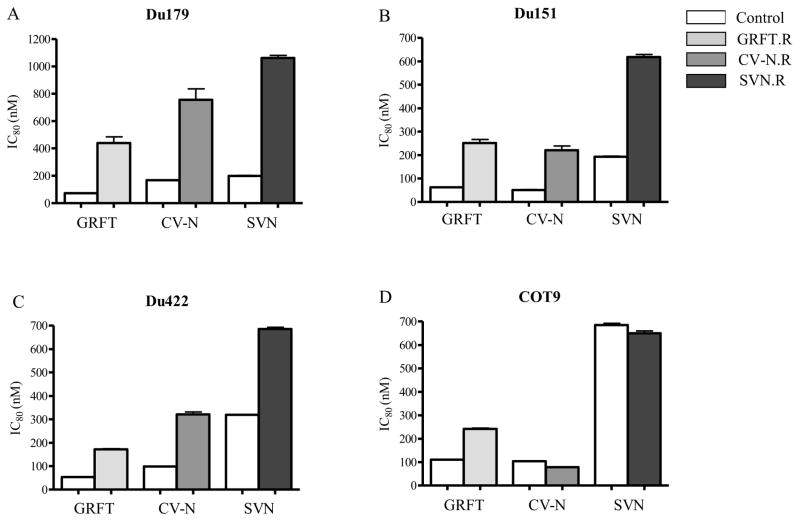

We next determined whether viruses cultured in the presence of GRFT, CV-N and SVN showed reduced sensitivity to these compounds in the PBMC neutralization assay, using an 80% neutralization (IC80) cut-off (Bures et al., 2002; Fenyo et al., 2009). Du179/GRFT.R, Du179/CV-N.R and Du179/SVN.R showed at least 5-fold increase in IC80 compared to the control viruses, passaged in the absence of the lectin (Figure 2A). For Du151 and Du422 there was an increase in IC80 that ranged from 2 to 4 fold for all 3 lectins (Figure 2B and C), while for COT9, the GRFT resistant virus showed a ~2 fold increase in IC80 (Figure 2D). However, there was no change in IC80 for COT9 cultured under CV-N and SVN, despite the ability to grow under increased concentrations of the two lectins.

Figure 2. Lectin-selected viruses showed a decreased sensitivity to GRFT, CV-N and SVN.

Resistant primary HIV-1 subtype C isolates Du179 (A), Du151 (B), Du422 (C) and COT9 (D) were tested against GRFT, CV-N and SVN in a PBMC neutralization assay. The neutralization of HIV-1 infection was measured by p24 ELISA and the IC80 of the resistant virus and the corresponding wild-type were determined by linear regression. Bars represent standard deviation of three independent experiments.

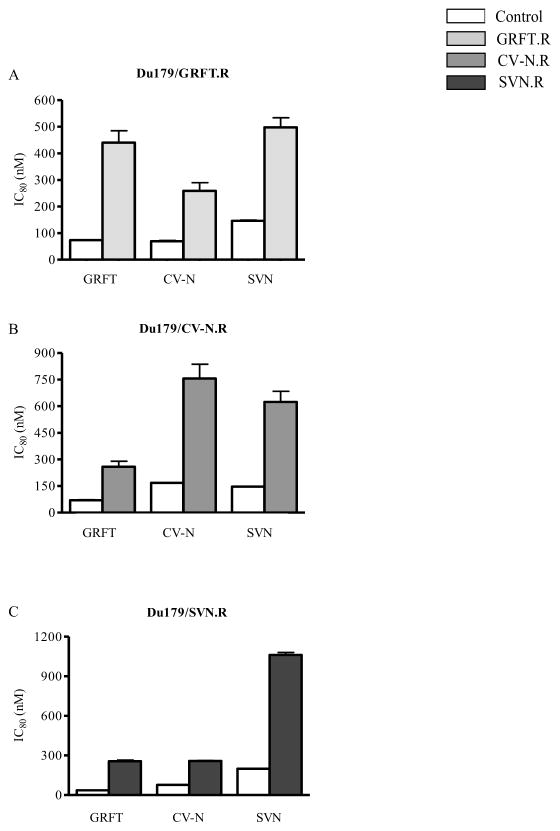

We next investigated whether viruses that were resistant to each compound also showed cross-resistance or decreased sensitivity to the other two lectins. We used Du179 for this study as this virus developed the greatest resistance to all three lectins. Du179/GRFT.R that was 10 fold resistant to GRFT showed a ~3 fold increase in resistance to CV-N and SVN neutralization (Figure 3). A similar pattern was observed for Du179/CV-N.R and Du179/SVN.R. These data suggest that resistance to one lectin confers cross-resistance to the other; however resistance to the selecting agent was always the strongest.

Figure 3. Cross-resistance between GRFT, CV-N and SVN.

Du179 virus selected by GRFT (A), CV-N (B) and SVN (C) were tested against all three lectins in a PBMC assay. HIV-1 neutralization was measured by p24 ELISA and the IC80 of the resistant virus (grey bar) and the corresponding wild-type (white bar) were determined by linear regression. Bars represent standard deviation of three independent experiments.

Resistance was associated with amino acid changes and deletions at and around mannose-rich glycosylation sites

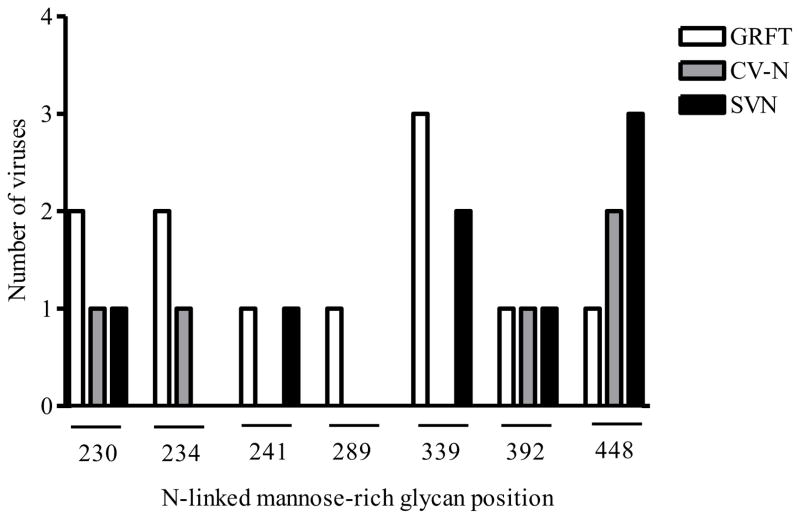

The full envelope sequences of both wild-type (viruses passaged in the absence of the lectin) and the corresponding resistant viruses were compared. Wild-type Du179, Du151 and COT9 each had 10 intact mannose-rich glycosylation sites while Du422 had nine. All four viruses lacked the 295 glycosylation site as is common among subtype C viruses (Zhang et al., 2004). Of the 12 selected viruses (four for each lectin), nine had deletions of glycans on gp120 with no changes in gp41 glycosylation patterns. Seven of the 11 glycosylation sites on gp120 that have been confirmed to contain mannose-rich glycans (Leonard et al., 1990), were involved in resistance to GRFT, CV-N and SVN (Figure 4). Deletions of the 230, 392 and 448 glycans were observed among viruses selected by all three lectins with the loss of the 448 glycan observed in 6 out of the 12 selected viruses. Except for position 289, deletions at the seven sites occurred in response to more than one lectin.

Figure 4. Mannose-rich glycosylation sites deleted in GRFT, CV-N and SVN selected viruses.

The X-axis shows the positions of mannose-rich glycans deleted in the four isolates under lectin selective pressure. The positions of glycans are numbered according to the HxB2 virus (Leonard et al., 1990) and were identified by sequence analysis. The Y-axis shows the number of resistant viruses (out of 4) that had the deletion.

Examination of glycan changes to individual lectins showed that the greatest number of deleted glycans was conferred by GRFT selection (Table 2). The loss of the glycan at position 339 occurred in three out of four GRFT selected viruses (Table 2 and Figure 4), with those at position 230 and 234 occurring in two. The GRFT resistant Du179 also deleted the 442 glycan, predicted to be complex in studies conducted with monomeric gp120 (Kwong et al., 1998; Leonard et al., 1990). The loss of sensitivity to GRFT in Du422 restored the glycan at position 386 that was absent in the wild type virus (Table 2). For CV-N resistant viruses, the loss of the 448 glycan was the most common, occurring in half of these viruses (Table 2). However, we did not observe any changes in COT9 and Du422 sequences that accompanied their increased resistance to CV-N. Three out of four SVN selected viruses had the 448 deletion while two out four had the 339 glycan loss (Table 2). As with GRFT, selection with SVN restored the 386 glycan in Du422. Lastly, similar to CV-N, COT9 resistance to SVN was not associated with any apparent changes in glycans.

Table 2.

Changes in gp120 mannose-rich glycosylation patterns associated with resistance to GRFT, CV-N and SVN

| Lectin | Virus | a Predicted mannose-rich glycosylation sites | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 230 | 234 | 241 | 262 | 289 | 295 | 332 | 339 | 386 | b392 | 448 | ||

| GRFT | Du179 | |||||||||||

| Du151 | ||||||||||||

| Du422 | ||||||||||||

| COT9 | ||||||||||||

| CV-N | Du179 | |||||||||||

| Du151 | ||||||||||||

| Du422 | ||||||||||||

| COT9 | ||||||||||||

| SVN | Du179 | |||||||||||

| Du151 | ||||||||||||

| Du422 | ||||||||||||

| COT9 | ||||||||||||

Mannose-rich glycosylation sites were identified from the amino acid sequence of each envelope clone (related to HxB2) based on a study using monomeric gp120 (Leonard et al., 1990).

Note that for Du179 and Du151 the 392 glycan is shifted to position 393 but it is placed at position 392 for simplicity.

Red colored boxes indicate glycosylation sites that were deleted under GRFT, CV-N or SVN selective pressure.

Green colored boxes indicate glycosylation sites that were added under GRFT, CV-N or SVN selective pressure.

Grey colored boxes indicate sites that were unchanged.

Blank boxes indicate sites that were absent in the wild-type virus.

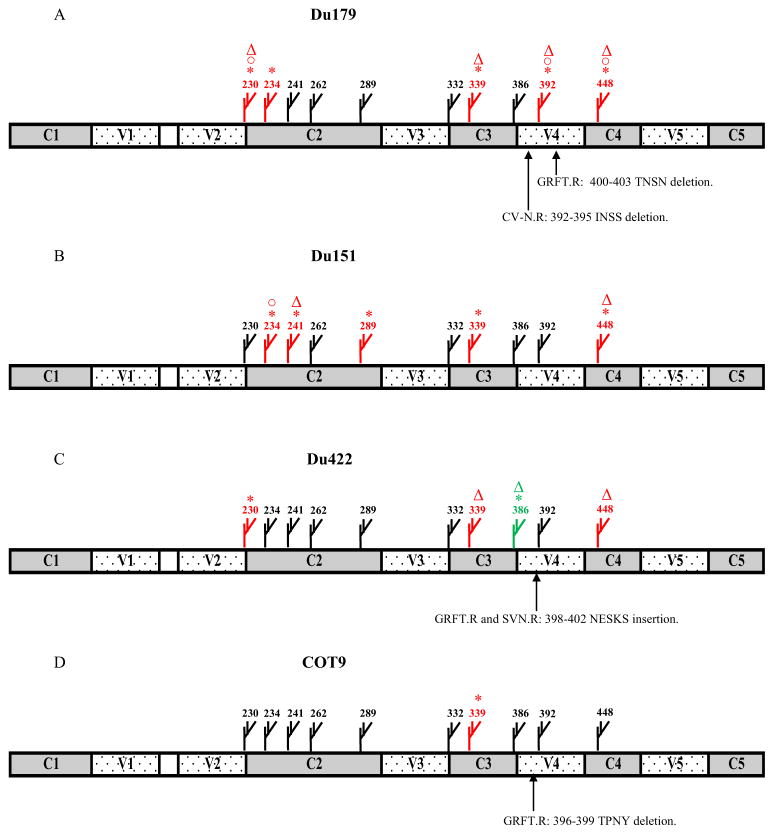

In addition to loss of glycans on gp120, we observed deletions and insertions of amino acid sequences near and within mannose-rich glycosylation sites located in the fourth variable (V4) region. GRFT resistance was associated with the deletion of four amino acids at position 400–403 and 396–399 in Du179 and COT9, respectively (Figure 5A and D). However, in Du422 resistance to GRFT resulted in the insertion of five amino acids at position 398–402 (Figure 5C). Similarly, CV-N resistance led to the deletion of four amino acids in Du179 at position 392–395 (Figure 5A) that resulted in the loss of the 392 glycan. In Du422, SVN resistance resulted in the insertion of five amino acids at position 398–402, this was similar to GRFT (Figure 5C). We observed no deletions or insertions of amino acids in Du151 under the selective pressure of any of the three lectins. In conclusion, our data using 4 subtype C primary isolates suggested that in addition to directly deleting glycans, resistance to GRFT, CV-N and SVN may frequently also involve deletion of multiple amino acids that results in shifting of the position of neighboring glycans.

Figure 5. Changes in gp120 associated with lectin selection.

Position of mannose-rich glycans and amino acid sequences for Du179 (A), Du151 (B), Du422 (C) and COT9 (D) following selection by GRFT, CV-N and SVN. Glycan deletions are shown in red and the addition in green. Symbols indicate changes in response to GRFT (*), CV-N (3) and SVN (3). Deletions and insertions of amino acid sequences in V4 are shown.

Single genome amplification of GRFT, CV-N and SVN resistant viruses

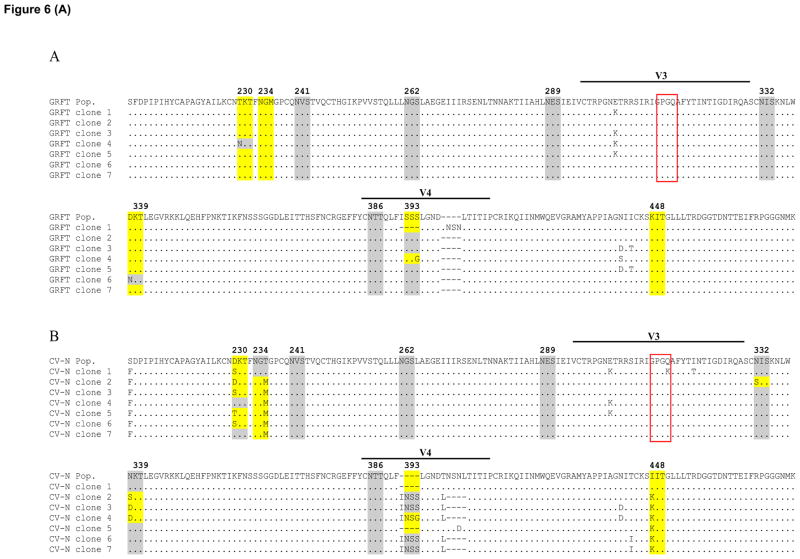

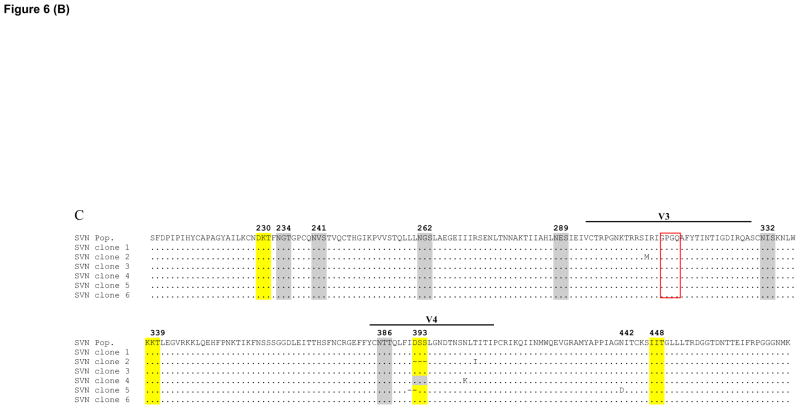

Since the loss of multiple glycans observed by total viral population sequencing could be the result of a mixture of viruses carrying fewer deletions, we performed single genome amplifications (SGA) of gp120. We used Du179 for this experiment since it had the highest number of glycan loss. Six to seven clones were selected for each lectin and compared to their corresponding total population sequence.

The majority of clones from GRFT cultures had the same 4 glycans deleted as the population sequence (highlighted in yellow) while the 393 glycan absent in the population sequence was deleted in only 2 of the 7 clones (Figure 6). Furthermore, all GRFT clones had the deletion of four amino acids in V4 and most were at position 400 to 403. For CV-N, most clones had one to two additional glycans deleted compared to the total population sequence. However, similar to the population sequence, all clones had the deletion of four amino acids in V4, although not all in the same location. With SVN both the number and glycan deletion pattern of isolated clones were almost identical to the total population sequence. But unlike this sequence, one had lost the 442 glycan while two carried deletions of amino acids in V4. Lastly, almost all GRFT, CV-N and SVN clones had GPGQ at the tip of the V3 loop which differed from the wild-type Du179 sequence with GPGK. Taken together, these data show that clones largely harbor the same mutational patterns as the total population sequence suggesting that multiple mutations on single genomes are required to develop resistance.

Figure 6. Amino acid sequence of isolated GRFT, CV-N and SVN resistant Du179 clones.

GRFT (A), CV-N (B) and SVN (C) resistant Du179 clones gp120 sequence isolated by single genome amplification were aligned with their respective population sequences. The grey shading shows the presence of a potential mannose-rich glycosylation site, yellow shading indicates the site deletion while the red box shows the tip of the V3 loop (McCaffrey et al., 2004). Note that the glycan at position 393 is labeled as 392 in the text for comparison with other viruses.

GRFT, CV-N and SVN resistance affects HIV-1 sensitivity to neutralizing antibodies

A previous study in subtype B showed that resistance to CV-N can affect HIV-1 sensitivity to neutralizing antibodies (Hu et al., 2007). Therefore, we investigated whether subtype C resistance to GRFT, CV-N and SVN impacted the senstivity to gp120 antibodies and soluble CD4 (sCD4) in the TZM-bl neutralization assay. Five Du179 SGA-derived clones with the highest number of glycan deletions selected by each lectin, were tested together with the Du179 clone passaged without the lectins (control). All GRFT, CV-N and SVN resistant viruses showed decreased sensitivity to b12 with 4–20 fold higher antibody concentrations required for neutralization (Table 3). In contrast, all 5 clones showed an increased sensitivity to VRC01 of 2–6 fold. We also observed a moderate increase in sensitivity to sCD4, which is known to have a similar binding site to VRC01 (Zhou et al., 2010). None of the viruses showed changes in sensitivity to the PGT121 or PGT128 mAbs, which bind to the glycans at positions 301 and 332 on the gp120 outer domain (Walker et al., 2011). In conclusion, our data show that resistance to GRFT, CV-N and SVN can affect HIV-1 subtype C sensitivity to some antibodies that target gp120.

Table 3.

Sensitivity of Du179 lectin-resistant clones to neutralizing antibodies and sCD4

| Envelope | Entry inhibitors a IC50 (μg/mL) b(fold change) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b12 | VRC01 | PGT121 | PGT128 | sCD4 | |

| Control | 0.7 | 0.60 | 0.065 | 0.18 | 4.0 |

| GRFT clone 1 | 12.5 (18↓) | 0.14 (4↑) | 0.043 | 0.13 | 1.2 (3↑) |

| GRFT clone 7 | 5.8 (8↓) | 0.10 (6↑) | 0.049 | 0.20 | 1.8 (2↑) |

| CV-N clone 1 | 6.4 (9↓) | 0.11 (5↑) | 0.055 | 0.21 | 2.2 (2↑) |

| CV-N clone 2 | 13.9 (20↓) | 0.15 (4↑) | 0.057 | 0.07 | 1.5 (3↑) |

| SVN clone 2 | 2.6 (4↓) | 0.31(2↑) | 0.061 | 0.16 | 3.3 |

Concentration needed to inhibit HIV-1 infection by 50%.

The increase and decrease in sensitivity is shown by arrows; only ≥ 2 fold changes are shown.

Confirmation of resistance conferring mutations by site-directed mutagenesis

To confirm if the changes seen in GRFT, CV-N and SVN selected viruses (shown in Table 2 and Figure 5) conferred resistance to the lectins, we introduced these changes into the corresponding wild-type cloned envelopes by site-directed mutagenesis. This included all changes at glycosylation sites as well as deletions and insertions in V4. For Du179.14 a total of 6 rounds of site-directed mutagenesis were necessary to produce Du179/GRFT.RM (where RM indicates resistance generated by mutagenesis). We could not test the CV-N associated mutations as functional viruses could not be obtained for Du179 and Du151 and no changes were noted for Du422 and COT9. The GRFT.RM and SVN.RM envelope clones were tested for sensitivity to GRFT and SVN relative to their wild-type counterparts in a TZM-bl cell neutralization assay.

The effect of the combined changes in glycosylation and V4 amino acid indels associated with GRFT and SVN resistance in the four cloned envelopes resulted in a loss of sensitivity to the lectins as seen by an increase in IC50 values of the mutant viruses (Table 4). For GRFT, there was a 3–4 fold decrease in sensitivity in all 4 viruses while for SVN the effect was more pronounced. In particular the insertion of 5 amino acids together with the loss of 2 glycans in Du422.1 resulted in a 16-fold increase in resistance to SVN. These data suggest that the changes we observed in the HIV-1 gp120 sequences from lectin-selected PBMC cultures were indeed resistance-conferring mutations.

Table 4.

Change in IC50 of mutant viruses compared to the corresponding wild type

| a IC50 (nM) (fold change) | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| b Pseudovirus | GRFT | SVN |

|

| ||

| Du179.14 (WT) | 3.6 ± 0.6 | 9.8 ± 1.6 |

| Du179/GRFT.RM (N230T/T236M/N339D/N393S/N448K/400-403 aa deletion) | 13.7± 0.6 (↑4) | |

| Du179/SVN.RM (N230D/N339K/N393D/N448I) | 46.0 ± 1.6 (↑5) | |

|

| ||

| Du151.2 (WT) | 3.3 ± 0.2 | 14.0 ± 0.7 |

| Du151/GRFT.RM (N234S/S243G/S291Y ) | 10.5 ± 0.4 (↑3) | |

| Du151/SVN.RM (N241K/N448D) | 106.4 ± 39.2 (↑8) | |

|

| ||

| Du422.1 (WT) | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 7.4 ± 1.2 |

| Du422/GRFT.RM (N230T/D386N/ 398-402 aa insertion) | 3.4 ± 0.8 (↑4) | |

| Du422/SVN.RM (N339K/N448T/398-402 aa insertion) | 117.5 ± 46.4 (↑16) | |

|

| ||

| COT9.6 (WT) | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 21.6 ± 7.5 |

| COT9/GRFT.RM (T341I/396-399 aa deletion) | 9.8 ± 3.7 (↑3) | |

The concentration needed to inhibit HIV-1 infection by 50%. Fold change of IC50 compared to WT is shown in brackets.

RM indicates that resistance was generated by mutagenesis. The aa changes that were introduced by mutagenesis are shown in brackets. The N339I mutation was not introduced in Du151.2 since this envelope clone lacked the glycan at position 339.

DISCUSSION

In this study we demonstrated that the continuous growth of four HIV-1 subtype C isolates under escalating concentrations of GRFT, CV-N and SVN resulted in reduced sensitivity to these lectins. This was associated with the deletion of mannose-rich glycans on gp120 and in some cases insertions or deletions of amino acids near mannose-rich glycosylation sites. These changes were observed in both the total population and clonal sequences of selected viruses and were confirmed to be resistance conferring by site-directed mutagenesis of envelope clones. This study is the first to report the mechanism of HIV-1 subtype C resistance to GRFT, CV-N and SVN and provides important insights into the binding sites of these lectins on the subtype C envelope.

The association between deletions of mannose-rich glycans on the subtype C viruses studied here and increased resistance to GRFT, CV-N and SVN is consistent with the fact that these compounds bind glycans on the viral envelope (Ziolkowska and Wlodawer, 2006). It also supports previous reports showing that glycan deletions mediate HIV-1 subtype B resistance to CV-N and GRFT (Balzarini et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2011; Witvrouw et al., 2005). Deleted glycans were located in C2, C3, V4 and C4 suggesting that the binding sites for these lectins are located in these regions, which are exposed on gp120 and hence readily accessible for binding. While the most resistant viruses generally had more glycan deletions there was no clear correlation between the number of deleted mannose-rich glycans and resistance to GRFT, CV-N and SVN. This supports our earlier study showing that the position of the glycan is also important in determining sensitivity to these lectins (Alexandre et al., 2010). The lack of correlation between the number of deleted glycans and resistance may suggest that some glycans are directly involved in lectin binding to HIV-1 while for others the involvement may be indirect i.e. they contribute to the formation of the binding site. Viruses selected by the three lectins showed cross-resistance to these compounds, also supporting our earlier finding that these lectins have overlapping binding sites on the viral envelope. Some of the affected glycans are within structural proximity of each other on gp120, which together with the symmetrical arrangement of binding sites on CV-N and GRFT, suggests that cross-linking of glycans underlies the mechanism of action of lectin inhibition (Ziolkowska et al., 2006; Ziolkowska and Wlodawer, 2006). This hypothesis has previously been proposed for GRFT (Moulaei et al., 2010).

The 448 glycan was the most frequently deleted glycan suggesting that it plays an important role in GRFT, CV-N and SVN binding to subtype C gp120. This glycan together with those at positions 230 and 392 were involved in resistance to all 3 lectins and have previously been shown to be important for subtype B viruses (Balzarini et al., 2006). Despite these similarities, our data suggest that there may be subtype-specific pathways to resistance. For example, the 332 glycan was not affected in our study while it was lost in subtype B viruses that developed resistance to CV-N (Balzarini et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2007; Witvrouw et al., 2005). This being said, the differences in culture conditions in addition to the use of different viral isolates may have accounted for some of these subtype-specific effects. We previously showed that viruses naturally lacking the 234 and 295 glycosylation sites were less sensitive to GRFT, CV-N and SVN (Alexandre et al., 2010). In the current study, we observed the deletion of the 234 glycosylation site for all three lectins suggesting that this glycan can participate in both natural and in vitro induced resistance to these compounds. In some Du179 resistant viruses we observed the deletion of the 442 glycosylation site which is not mannose-rich on monomeric gp120 (Leonard et al., 1990). However, recent studies have indicated that glycans on envelope trimer are more resistant to mannose-trimming generating complex glycans (Bonomelli et al.; Doores et al.). Thus, it can be speculated that the 442 glycosylation site on the trimer contains a mannose-rich glycan and is, therefore, another potential binding site for GRFT, CV-N and SVN.

In addition to single amino acid changes that resulted in the loss of glycans, we noted 4–5 amino acid indels in V4 sequences in 3 of the 4 viruses studied. In the case of Du179 cultured in CV-N, this obliterated the 393 glycosylation site. This mechanism of resistance has also been reported by Witvrouw and colleagues who showed that HIV-1 cultured in increasing concentrations of CV-N had a 13 amino acid deletion in V4 resulting in the loss of 3 glycosylation sites (Witvrouw et al., 2005). The other indels found in our study did not involve the loss of glycans but occurred near mannose-rich glycosylation sites, which likely affected their arrangement. Further work is needed to explore the impact of these V4 changes to determine if they affect lectin sensitivity independently of glycan deletions.

In this study we showed that individual clones generally had the same number of deleted glycans as the total population sequence. This implies that resistance is not due to a swarm of quasispecies with different mutational profiles but that multiple mutations on each genome are needed for resistance to GRFT, CV-N and SVN. However, there was variation with some clones having slightly different glycan deletion patterns that collectively matched the population sequence. It is possible that each clone has different levels of sensitivity to the lectins that could coexist provided that they have sufficient resistance conferring mutations. It can also be speculated that the presence of strains with different levels of glycan loss is the result of differences in their mechanisms of escape. An in-depth analysis of minority variants in Du422 and COT9 may help to explain why no mutations were seen in the population sequence of these viruses despite phenotypic resistance to the lectins.

The increased sensitivity of GRFT, CV-N and SVN resistant Du179 clones to VRC01 and sCD4 suggests that lectin-escape mutations affect the exposure of the CD4 binding site (CD4bs). However, the simultaneous decrease in sensitivity to b12 that also targets this site indicates that these mutations differentially affect these compounds. This is probably due to the fact that althought they all bind the CD4bs the footprint of VRC01, b12 and sCD4 on gp120 do not completely overlap (Li et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2007). A previous study showed that HIV-1 escape from CV-N did not affect sensitivity to b12 despite the fact that this isolate became sensitive to V3 and other HIV antibodies (Hu et al., 2007). Our finding of decreased resistance to b12 in 5 distinct clones from a single isolate suggests that there are also virus dependent effects. We did not observe a change in sensitivity to the PGT121 and PGT128 antibodies, consistent with the fact that the 332 glycan (Walker et al., 2011) was not deleted in our resistant viruses (Table 2).

Du179 developed the highest level of resistance to these lectins. It is unlikely that this was due to differences in glycosylation as the wild-type Du179 had an identical mannose-rich glycosylation pattern as Du151 and COT9. It is also unlikely that the preselection sensitivity of these viruses to GRFT, CV-N and SVN played any role in the development of resistance to the lectins given that they had similar IC50 values (Table 1). However, Du179 was the only dual-tropic virus tested here (Coetzer et al., 2007; Williamson et al., 2003). We previously showed that GRFT blocks HIV infection by interfering with co-receptor binding (Alexandre et al., 2011). Thus, the ability of Du179 to enter cells via both CCR5 and CXCR4 may have provided additional opportunities to escape the inhibitory effects of these lectins. Indeed, our data suggest that lectin selection did impact on viral tropism as the GPGK at the tip of the V3 loop in Du179 was replaced with GPGQ that is characteristic of R5 viruses (Cilliers et al., 2003; Coetzer et al., 2011). Thus, testing a larger number of dual tropic viruses and comparing them to single tropic viruses may reveal to what extent the R5X4 property affects the rate at which HIV-1 develops resistance to these lectins.

The level of resistance to the lectins observed in our study was 2–12 fold, which was not as high as reported in some other studies (Balzarini et al., 2006; Witvrouw et al., 2005). The reason for this may be due to our use of PBMC that do not support HIV-1 replication to the same extent as cell lines used by other investigators. Also our viruses were primary isolates that may have different replication capacity or pathways to resistance compared to lab-adapted viruses and molecular clones used in previous studies (Balzarini et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2007; Witvrouw et al., 2005). Partial resistance to CV-N was also reported by Balzarini and colleagues and was shown to be associated with fewer glycan deletions. Defining these early events in the development of resistance will help to understand the evolution of complete lectin resistance.

GRFT, CV-N and SVN are among leading CBAs that are being studied for use in HIV-1 prevention. However, until now much of what was known about HIV-1 resistance to these lectins is the result of studies conducted with subtype B viruses that have a different glycosylation pattern compared to subtype C (Zhang et al., 2004). Thus the current study makes an important contribution to our understanding of the mechanism of resistance to GRFT, CV-N and SVN in HIV-1 subtype C viruses, the main cause of HIV infections around the world. The extensive loss of glycans and amino acid sequence changes required for resistance to these three lectins poses a high genetic barrier distinct from the single glycan deletion required to confer resistance to the 2G12 monoclonal antibody. Thus lectins have a broader reactivity and would be expected to target a variety of wild-type viruses compared to antibodies that are more specific; and attempts are being made to test these compounds in humans. Taken together, our study supports further research in the use of GRFT, CV-N and SVN to prevent the spread of HIV-1.

Research Highlights.

First description of HIV-1 subtype C resistance to lectins, griffithsin, cyanovirin-N and scytovirin

Resistance was associated with the loss of glycans in gp120 and amino acid changes in V4

Clonal analysis suggested that multiple changes were required to confer resistance

There was extensive cross-resistance between these three lectins

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the BioFISA program of NEPAD Agency/SANBio under the microbicide project, the Poliomyelitis Research Foundation, the South African AIDS Vaccine Initiative (SAAVI) and a training fellowship to KBA from Columbia University-Southern African Fogarty AIDS International Training and Research Programme (AITRP) funded by the Fogarty International Center, NIH. This research was also supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research (B. O.& J. M.). Penny Moore is supported by the Wellcome Trust (Grant 089933/Z/09/Z).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexandre KB, Gray ES, Lambson BE, Moore PL, Choge IA, Mlisana K, Karim SS, McMahon J, O’Keefe B, Chikwamba R, Morris L. Mannose-rich glycosylation patterns on HIV-1 subtype C gp120 and sensitivity to the lectins, Griffithsin, Cyanovirin-N and Scytovirin. Virology. 2010;402:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandre KB, Gray ES, Pantophlet R, Moore PL, McMahon JB, Chakauya E, O’Keefe BR, Chikwamba R, Morris L. Binding of the mannose-specific lectin, griffithsin, to HIV-1 gp120 exposes the CD4-binding site. J Virol. 2011;85:9039–9050. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02675-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzarini J. Targeting the glycans of gp120: a novel approach aimed at the Achilles heel of HIV. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:726–731. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzarini J, Van Laethem K, Hatse S, Froeyen M, Van Damme E, Bolmstedt A, Peumans W, De Clercq E, Schols D. Marked depletion of glycosylation sites in HIV-1 gp120 under selection pressure by the mannose-specific plant lectins of Hippeastrum hybrid and Galanthus nivalis. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:1556–1565. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.005082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzarini J, Van Laethem K, Hatse S, Vermeire K, De Clercq E, Peumans W, Van Damme E, Vandamme AM, Bolmstedt A, Schols D. Profile of resistance of human immunodeficiency virus to mannose-specific plant lectins. J Virol. 2004;78:10617–10627. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.19.10617-10627.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balzarini J, Van Laethem K, Peumans WJ, Van Damme EJ, Bolmstedt A, Gago F, Schols D. Mutational pathways, resistance profile, and side effects of cyanovirin relative to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 strains with N-glycan deletions in their gp120 envelopes. J Virol. 2006;80:8411–8421. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00369-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binley JM, Wrin T, Korber B, Zwick MB, Wang M, Chappey C, Stiegler G, Kunert R, Zolla-Pazner S, Katinger H, Petropoulos CJ, Burton DR. Comprehensive cross-clade neutralization analysis of a panel of anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 2004;78:13232–13252. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.23.13232-13252.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bokesch HR, O’Keefe BR, McKee TC, Pannell LK, Patterson GM, Gardella RS, Sowder RC, 2nd, Turpin J, Watson K, Buckheit RW, Jr, Boyd MR. A potent novel anti-HIV protein from the cultured cyanobacterium Scytonema varium. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2578–2584. doi: 10.1021/bi0205698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomelli C, Doores KJ, Dunlop DC, Thaney V, Dwek RA, Burton DR, Crispin M, Scanlan CN. The glycan shield of HIV is predominantly oligomannose independently of production system or viral clade. PLoS One. 6:e23521. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd MR, Gustafson KR, McMahon JB, Shoemaker RH, O’Keefe BR, Mori T, Gulakowski RJ, Wu L, Rivera MI, Laurencot CM, Currens MJ, Cardellina JH, 2nd, Buckheit RW, Jr, Nara PL, Pannell LK, Sowder RC, 2nd, Henderson LE. Discovery of cyanovirin-N, a novel human immunodeficiency virus-inactivating protein that binds viral surface envelope glycoprotein gp120: potential applications to microbicide development. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1521–1530. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.7.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bures R, Gaitan A, Zhu T, Graziosi C, McGrath KM, Tartaglia J, Caudrelier P, El Habib R, Klein M, Lazzarin A, Stablein DM, Deers M, Corey L, Greenberg ML, Schwartz DH, Montefiori DC. Immunization with recombinant canarypox vectors expressing membrane-anchored glycoprotein 120 followed by glycoprotein 160 boosting fails to generate antibodies that neutralize R5 primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2000;16:2019–2035. doi: 10.1089/088922200750054756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bures R, Morris L, Williamson C, Ramjee G, Deers M, Fiscus SA, Abdool-Karim S, Montefiori DC. Regional clustering of shared neutralization determinants on primary isolates of clade C human immunodeficiency virus type 1 from South Africa. J Virol. 2002;76:2233–2244. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2233-2244.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Xu X, Bishop A, Jones IM. Reintroduction of the 2G12 epitope in an HIV-1 clade C gp120. Aids. 2005;19:833–835. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000168980.74713.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choge I, Cilliers T, Walker P, Taylor N, Phoswa M, Meyers T, Viljoen J, Violari A, Gray G, Moore PL, Papathanosopoulos M, Morris L. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of viral isolates from HIV-1 subtype C-infected children with slow and rapid disease progression. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2006;22:458–465. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.22.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cilliers T, Nhlapo J, Coetzer M, Orlovic D, Ketas T, Olson WC, Moore JP, Trkola A, Morris L. The CCR5 and CXCR4 coreceptors are both used by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolates from subtype C. J Virol. 2003;77:4449–4456. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.7.4449-4456.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzer M, Cilliers T, Papathanasopoulos M, Ramjee G, Karim SA, Williamson C, Morris L. Longitudinal analysis of HIV type 1 subtype C envelope sequences from South Africa. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007;23:316–321. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.0207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coetzer M, Nedellec R, Cilliers T, Meyers T, Morris L, Mosier DE. Extreme genetic divergence is required for coreceptor switching in HIV-1 subtype C. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56:9–15. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f63906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doores KJ, Bonomelli C, Harvey DJ, Vasiljevic S, Dwek RA, Burton DR, Crispin M, Scanlan CN. Envelope glycans of immunodeficiency virions are almost entirely oligomannose antigens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107:13800–13805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006498107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenyo EM, Heath A, Dispinseri S, Holmes H, Lusso P, Zolla-Pazner S, Donners H, Heyndrickx L, Alcami J, Bongertz V, Jassoy C, Malnati M, Montefiori D, Moog C, Morris L, Osmanov S, Polonis V, Sattentau Q, Schuitemaker H, Sutthent R, Wrin T, Scarlatti G. International network for comparison of HIV neutralization assays: the NeutNet report. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferir G, Huskens D, Palmer KE, Boudreaux DM, Swanson MD, Markovitz DM, Balzarini J, Schols D. Combinations of griffithsin with other carbohydrate-binding agents demonstrate superior activity against HIV Type 1, HIV Type 2, and selected carbohydrate-binding agent-resistant HIV Type 1 strains. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2012;28:1513–1523. doi: 10.1089/aid.2012.0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geijtenbeek TB, Gringhuis SI. Signalling through C-type lectin receptors: shaping immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:465–479. doi: 10.1038/nri2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray ES, Moore PL, Pantophlet RA, Morris L. N-linked glycan modifications in gp120 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C render partial sensitivity to 2G12 antibody neutralization. J Virol. 2007;81:10769–10776. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01106-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Q, Mahmood N, Shattock RJ. High-mannose-specific deglycosylation of HIV-1 gp120 induced by resistance to cyanovirin-N and the impact on antibody neutralization. Virology. 2007;368:145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Jin W, Griffin GE, Shattock RJ, Hu Q. Removal of two high-mannose N-linked glycans on gp120 renders human immunodeficiency virus 1 largely resistant to the carbohydrate-binding agent griffithsin. J Gen Virol. 2011;92:2367–2373. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.033092-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VA, Byington RE. Quantitative assays for virus infectivity. In: Aldovini A, Walker BD, editors. Techniques in HIV Research. Stockton Press; New York: 1990. pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet RW, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard CK, Spellman MW, Riddle L, Harris RJ, Thomas JN, Gregory TJ. Assignment of intrachain disulfide bonds and characterization of potential glycosylation sites of the type 1 recombinant human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein (gp120) expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10373–10382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Luo L, Rasool N, Kang CY. Glycosylation is necessary for the correct folding of human immunodeficiency virus gp120 in CD4 binding. J Virol. 1993;67:584–588. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.1.584-588.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, O’Dell S, Walker LM, Wu X, Guenaga J, Feng Y, Schmidt SD, McKee K, Louder MK, Ledgerwood JE, Graham BS, Haynes BF, Burton DR, Wyatt RT, Mascola JR. Mechanism of neutralization by the broadly neutralizing HIV-1 monoclonal antibody VRC01. J Virol. 2011;85:8954–8967. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00754-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G, Simmons G, Pohlmann S, Baribaud F, Ni H, Leslie GJ, Haggarty BS, Bates P, Weissman D, Hoxie JA, Doms RW. Differential N-linked glycosylation of human immunodeficiency virus and Ebola virus envelope glycoproteins modulates interactions with DC-SIGN and DC-SIGNR. J Virol. 2003;77:1337–1346. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.2.1337-1346.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Liu H, Kim BO, Gattone VH, Li J, Nath A, Blum J, He JJ. CD4-independent infection of astrocytes by human immunodeficiency virus type 1: requirement for the human mannose receptor. J Virol. 2004;78:4120–4133. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.8.4120-4133.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losman B, Bolmstedt A, Schonning K, Bjorndal A, Westin C, Fenyo EM, Olofsson S. Protection of neutralization epitopes in the V3 loop of oligomeric human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein 120 by N-linked oligosaccharides in the V1 region. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2001;17:1067–1076. doi: 10.1089/088922201300343753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lue J, Hsu M, Yang D, Marx P, Chen Z, Cheng-Mayer C. Addition of a single gp120 glycan confers increased binding to dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3-grabbing nonintegrin and neutralization escape to human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 2002;76:10299–10306. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.20.10299-10306.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manrique A, Rusert P, Joos B, Fischer M, Kuster H, Leemann C, Niederost B, Weber R, Stiegler G, Katinger H, Gunthard HF, Trkola A. In vivo and in vitro escape from neutralizing antibodies 2G12, 2F5, and 4E10. J Virol. 2007;81:8793–8808. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00598-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey RA, Saunders C, Hensel M, Stamatatos L. N-linked glycosylation of the V3 loop and the immunologically silent face of gp120 protects human immunodeficiency virus type 1 SF162 from neutralization by anti-gp120 and anti-gp41 antibodies. J Virol. 2004;78:3279–3295. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.7.3279-3295.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montefiori DC. Evaluating neutralizing antibodies againts HIV, SIV and SHIV in luciferase reporter gene assays. In: Coligan JE, Kruisbeek AM, Margulies DH, Shevach EM, Strober W, Coico R, editors. Current Protocols in Immunology. John Wiley & Sons; 2004. pp. 12.11.11–12.11.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori T, O’Keefe BR, Sowder RC, 2nd, Bringans S, Gardella R, Berg S, Cochran P, Turpin JA, Buckheit RW, Jr, McMahon JB, Boyd MR. Isolation and characterization of griffithsin, a novel HIV-inactivating protein, from the red alga Griffithsia sp. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:9345–9353. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulaei T, Botos I, Ziolkowska NE, Bokesch HR, Krumpe LR, McKee TC, O’Keefe BR, Dauter Z, Wlodawer A. Atomic-resolution crystal structure of the antiviral lectin scytovirin. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2756–2760. doi: 10.1110/ps.073157507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulaei T, Shenoy SR, Giomarelli B, Thomas C, McMahon JB, Dauter Z, O’Keefe BR, Wlodawer A. Monomerization of viral entry inhibitor griffithsin elucidates the relationship between multivalent binding to carbohydrates and anti-HIV activity. Structure. 2010;18:1104–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe BR, Vojdani F, Buffa V, Shattock RJ, Montefiori DC, Bakke J, Mirsalis J, d’Andrea AL, Hume SD, Bratcher B, Saucedo CJ, McMahon JB, Pogue GP, Palmer KE. Scaleable manufacture of HIV-1 entry inhibitor griffithsin and validation of its safety and efficacy as a topical microbicide component. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6099–6104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901506106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Bailes E, Pham KT, Salazar MG, Guffey MB, Keele BF, Derdeyn CA, Farmer P, Hunter E, Allen S, Manigart O, Mulenga J, Anderson JA, Swanstrom R, Haynes BF, Athreya GS, Korber BT, Sharp PM, Shaw GM, Hahn BH. Deciphering human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission and early envelope diversification by single-genome amplification and sequencing. J Virol. 2008;82:3952–3970. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02660-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CC, Emau P, Jiang Y, Agy MB, Shattock RJ, Schmidt A, Morton WR, Gustafson KR, Boyd MR. Cyanovirin-N inhibits AIDS virus infections in vaginal transmission models. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2004;20:11–18. doi: 10.1089/088922204322749459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai CC, Emau P, Jiang Y, Tian B, Morton WR, Gustafson KR, Boyd MR. Cyanovirin-N gel as a topical microbicide prevents rectal transmission of SHIV89.6P in macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19:535–541. doi: 10.1089/088922203322230897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LM, Huber M, Doores KJ, Falkowska E, Pejchal R, Julien JP, Wang SK, Ramos A, Chan-Hui PY, Moyle M, Mitcham JL, Hammond PW, Olsen OA, Phung P, Fling S, Wong CH, Phogat S, Wrin T, Simek MD, Koff WC, Wilson IA, Burton DR, Poignard P. Broad neutralization coverage of HIV by multiple highly potent antibodies. Nature. 2011;477:466–470. doi: 10.1038/nature10373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Decker JM, Wang S, Hui H, Kappes JC, Wu X, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Komarova NL, Nowak MA, Hahn BH, Kwong PD, Shaw GM. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature. 2003;422:307–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson C, Morris L, Maughan MF, Ping LH, Dryga SA, Thomas R, Reap EA, Cilliers T, van Harmelen J, Pascual A, Ramjee G, Gray G, Johnston R, Karim SA, Swanstrom R. Characterization and selection of HIV-1 subtype C isolates for use in vaccine development. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2003;19:133–144. doi: 10.1089/088922203762688649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witvrouw M, Fikkert V, Hantson A, Pannecouque C, O’Keefe BR, McMahon J, Stamatatos L, de Clercq E, Bolmstedt A. Resistance of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to the high-mannose binding agents cyanovirin N and concanavalin A. J Virol. 2005;79:7777–7784. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7777-7784.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Gaschen B, Blay W, Foley B, Haigwood N, Kuiken C, Korber B. Tracking global patterns of N-linked glycosylation site variation in highly variable viral glycoproteins: HIV, SIV, and HCV envelopes and influenza hemagglutinin. Glycobiology. 2004;14:1229–1246. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwh106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou JY, Montefiori DC. Antibody-mediated neutralization of primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells is not affected by the initial activation state of the cells. J Virol. 1997;71:2512–2517. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2512-2517.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T, Georgiev I, Wu X, Yang ZY, Dai K, Finzi A, Kwon YD, Scheid JF, Shi W, Xu L, Yang Y, Zhu J, Nussenzweig MC, Sodroski J, Shapiro L, Nabel GJ, Mascola JR, Kwong PD. Structural basis for broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 by antibody VRC01. Science. 2010;329:811–817. doi: 10.1126/science.1192819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou T, Xu L, Dey B, Hessell AJ, Van Ryk D, Xiang SH, Yang X, Zhang MY, Zwick MB, Arthos J, Burton DR, Dimitrov DS, Sodroski J, Wyatt R, Nabel GJ, Kwong PD. Structural definition of a conserved neutralization epitope on HIV-1 gp120. Nature. 2007;445:732–737. doi: 10.1038/nature05580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Borchers C, Bienstock RJ, Tomer KB. Mass spectrometric characterization of the glycosylation pattern of HIV-gp120 expressed in CHO cells. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11194–11204. doi: 10.1021/bi000432m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziolkowska NE, O’Keefe BR, Mori T, Zhu C, Giomarelli B, Vojdani F, Palmer KE, McMahon JB, Wlodawer A. Domain-swapped structure of the potent antiviral protein griffithsin and its mode of carbohydrate binding. Structure. 2006;14:1127–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziolkowska NE, Wlodawer A. Structural studies of algal lectins with anti-HIV activity. Acta Biochim Pol. 2006;53:617–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]