Abstract

Mitophagy is a process that selectively degrades mitochondria. When mitophagy is induced in yeast, the mitochondrial outer membrane protein Atg32 is phosphorylated, interacts with the adaptor protein Atg11 and is recruited into the vacuole with mitochondria. We screened kinase-deleted yeast strains and found that CK2 is essential for Atg32 phosphorylation, Atg32–Atg11 interaction and mitophagy. Inhibition of CK2 specifically blocks mitophagy, but not macroautophagy, pexophagy or the Cvt pathway. In vitro, CK2 phosphorylates Atg32 at serine 114 and serine 119. We conclude that CK2 regulates mitophagy by directly phosphorylating Atg32.

Keywords: autophagy, mitochondria, mitophagy, yeast, casein kinase 2

Introduction

Autophagy (bulk autophagy) is a catabolic process that non-selectively degrades cytoplasmic components and organelles, and is conserved in almost all eukaryotes. During cellular stress, such as nutrient starvation, a cup-shaped double-membrane structure termed the isolation membrane (or phagophore) emerges in the cytoplasm, then elongates with curvature and finally becomes enclosed, forming an autophagosome containing cytoplasmic components. Subsequently, autophagosomes fuse with lysosomes in mammalian cells or vacuoles in yeast, and lysosomal/vacuolar hydrolases degrade the sequestered material [1]. In contrast to bulk autophagy, selective autophagy targets a specific cellular component as cargo [2]. The cytoplasm-to-vacuole targeting (Cvt) pathway is an autophagy-like process that delivers the Cvt complex (aminopeptidase I and α-mannosidase complex) from the cytoplasm to vacuoles, whereas pexophagy is the selective degradation of peroxisomes via autophagy.

Similarly, mitochondria autophagy (mitophagy) is a type of autophagy that selectively degrades mitochondria via the autophagic pathway [3]. Recent studies have shown that mitophagy has an important role in mitochondrial elimination during red blood cell differentiation [4, 5] and that defects in mitophagy causes Parkin- and PINK1-related familial Parkinson’s disease [6, 7]. However, the molecular mechanisms and regulatory signalling of mitophagy are still poorly understood.

ATG32 is an indispensable mitophagy-specific gene identified by a yeast genome-wide screen for mitophagy [8–10]. Its encoded protein, Atg32, is a mitochondrial outer membrane protein. When mitophagy is induced, serine 114 and serine 119 on Atg32 are phosphorylated. Then, Atg11, the cytosolic adaptor protein for selective autophagy, interacts with phosphorylated Atg32, especially at phosphorylated serine 114. Finally, Atg11 recruits mitochondria to the phagophore assembly site/pre-autophagosomal structure. Subsequently, the isolation membrane is generated, and mitochondria are selectively sequestered by autophagosomes for degradation [11]. Thus, the phosphorylation of Atg32 is an indispensable initiation switch for the selective recognition and degradation of mitochondria by mitophagy. However, the regulation of mitophagy, for example how and what regulate the phosphorylation of Atg32, has not been identified.

Casein kinase 2 (CK2) is a serine/threonine protein kinase that is highly conserved among eukaryotes and has roles in many different cellular processes, such as cell survival, cell cycle regulation, cell polarity, stress responses, transcription and translation [12, 13]. This enzyme in yeast has a tetrameric structure composed of two catalytic (Cka1 and/or Cka2) subunits and two regulatory (Ckb1 and Ckb2) subunits. Deletion of any of the four subunit-encoding genes individually has no overt phenotypic effect, but loss of both Cka1 and Cka2 is lethal. Although Cka1 and Cka2 can functionally compensate for each other, there are differences in their roles. Cka1 has a greater role in cell cycle progression, whereas Cka2 is more important in cell polarity. These regulatory subunits are thought to be responsible for the substrate specificity, kinase activity and stability of CK2. For the majority of substrates, the regulatory subunits stimulate kinase activity, whereas for others (for example, calmodulin, mdm-2), the regulatory subunits inhibit kinase activity [13, 14].

In this study, we screened yeast mutants of kinase- and kinase cofactor-encoding genes for an Atg32 phosphorylation-deficient strain. We found that CK2 regulates mitophagy by directly phosphorylating Atg32.

Results and discussion

Screen for kinases that affect Atg32 phosphorylation

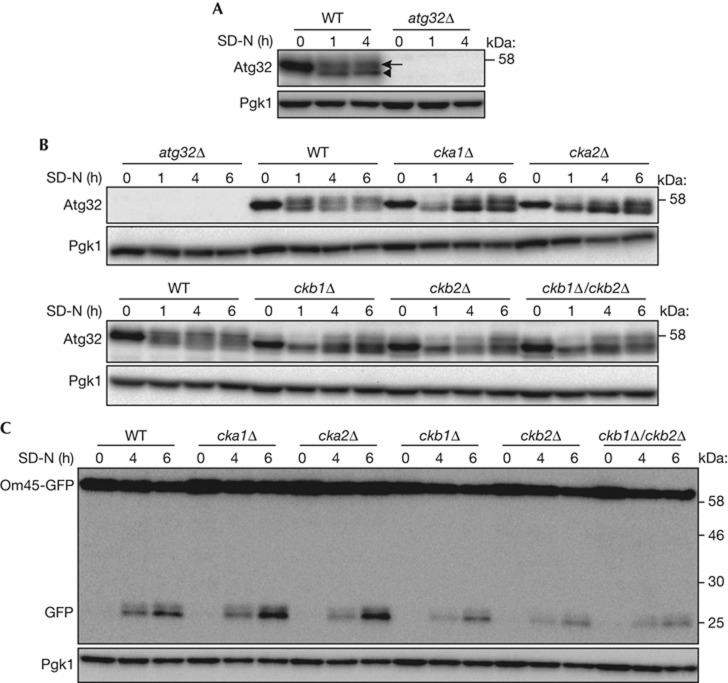

Mitophagy is induced efficiently when cells are cultured in lactate medium (YPL) and then shifted to nitrogen starvation medium supplemented with glucose (SD-N). Atg32 phosphorylation can be observed by immunoblotting. After nitrogen starvation, the molecular weight of Atg32 decreased owing to dephosphorylation of an unidentified phosphorylated residue, which is constitutively phosphorylated before starvation (Fig 1A, arrowhead). At the same time, the molecular weight of Atg32 increased because of phosphorylation of serines 114 and 119 (Fig 1A, arrow) [11].

Figure 1.

Deletion of CK2 components affects Atg32 phosphorylation. (A,B) WT and atg32Δ strains were cultured in YPL medium until the mid-log growth phase and then shifted to SD-N medium for 0, 1, or 4 h (A). WT, atg32Δ, cka1Δ, cka2Δ, ckb1Δ, ckb2Δ, and ckb1Δ/ckb2Δ strains were cultured in YPL medium until the mid-log growth phase, and then shifted to SD-N medium for 0, 1, 4 or 6 h (B). The phosphorylation status of Atg32 was observed by immunoblotting with anti-Atg32 and anti-Pgk1 (loading control) antibodies. The arrowhead and arrow indicate dephosphorylated and phosphorylated Atg32, respectively. (C) WT, atg32Δ, cka1Δ, cka2Δ, ckb1Δ, ckb2Δ and ckb1Δ/ckb2Δ strains expressing Om45-GFP were cultured in YPL medium until the mid-log growth phase and then shifted to SD-N for 0, 4 or 6 h. GFP processing was monitored by immunoblotting with anti-GFP and anti-Pgk1 antibodies. CK2, Casein kinase 2; GFP, green fluorescent protein; WT, wild type.

To identify the kinase that phosphorylates Atg32, we screened kinase, kinase cofactor and kinase-related gene knockout strains and determined whether they could phosphorylate Atg32 after nitrogen starvation for 1 h (supplementary Table S1; Fig S1 online). From this screen, we observed that the cka1Δ, cka2Δ, ckb1Δ and ckb2Δ strains affected Atg32 phosphorylation (supplementary Figs S1 and S2 online). To confirm the requirement for CK2 components for Atg32 phosphorylation, we developed cka1Δ, cka2Δ, ckb1Δ, ckb2Δ and ckb1Δ/ckb2Δ strains using another cell line (SEY6210). All CK2 mutants showed normal mitochondrial morphology, although the growth of ckb1Δ, ckb2Δ and ckb1Δ/ckb2Δ cells was slightly suppressed in YPL medium (supplementary Figs S3 and S4 online). In all CK2 mutants, Atg32 phosphorylation was barely observed after a 1-h nitrogen starvation. Phosphorylated Atg32 gradually increased at 4 and 6 h after nitrogen starvation, although the ratio of phosphorylated/dephosphorylated Atg32 was smaller than that of wild-type (WT) cells (Fig 1B). Because phosphorylation of Atg32 is essential for mitophagy, we examined whether the reduction of Atg32 phosphorylation in these CK2 mutant cells affects mitophagy. To observe mitophagy, we used the Om45-green fluorescent protein (GFP) processing assay that can monitor mitophagy levels semi-quantitatively [15]. Om45 is a mitochondrial outer membrane protein. Om45 tagged with GFP localized to the mitochondrial outer membrane and accumulated in vacuoles when mitophagy was induced. Although the Om45-GFP that accumulated in vacuoles was degraded, GFP was relatively stable within the vacuoles and was often released as an intact protein. Thus, the level of mitophagy could be semi-quantitatively monitored by measuring using immunoblotting the amount of GFP processed from Om45-GFP. As shown in Fig 1C, GFP processed from Om45-GFP in cka1Δ or cka2Δ cells was at a similar level to that in WT cells, suggesting that deletion of CKA1 or CKA2 did not affect mitophagy. In contrast, GFP processed from Om45-GFP in ckb1Δ, ckb2Δ or ckb1Δ/ckb2Δ cells was weaker than that in WT cells (Fig 1C). Because Om45-GFP expression in ckb1Δ, ckb2Δ or ckb1Δ/ckb2Δ cells was also weaker compared with WT cells, it is difficult to determine whether the reduction of processed GFP in these cells was due to mitophagy deficiency or to a reduction of the substrate, Om45-GFP. At least, deletion of one of the CK2 components did not show the severe deficiency in mitophagy.

CK2 activity is required for Atg32 phosphorylation

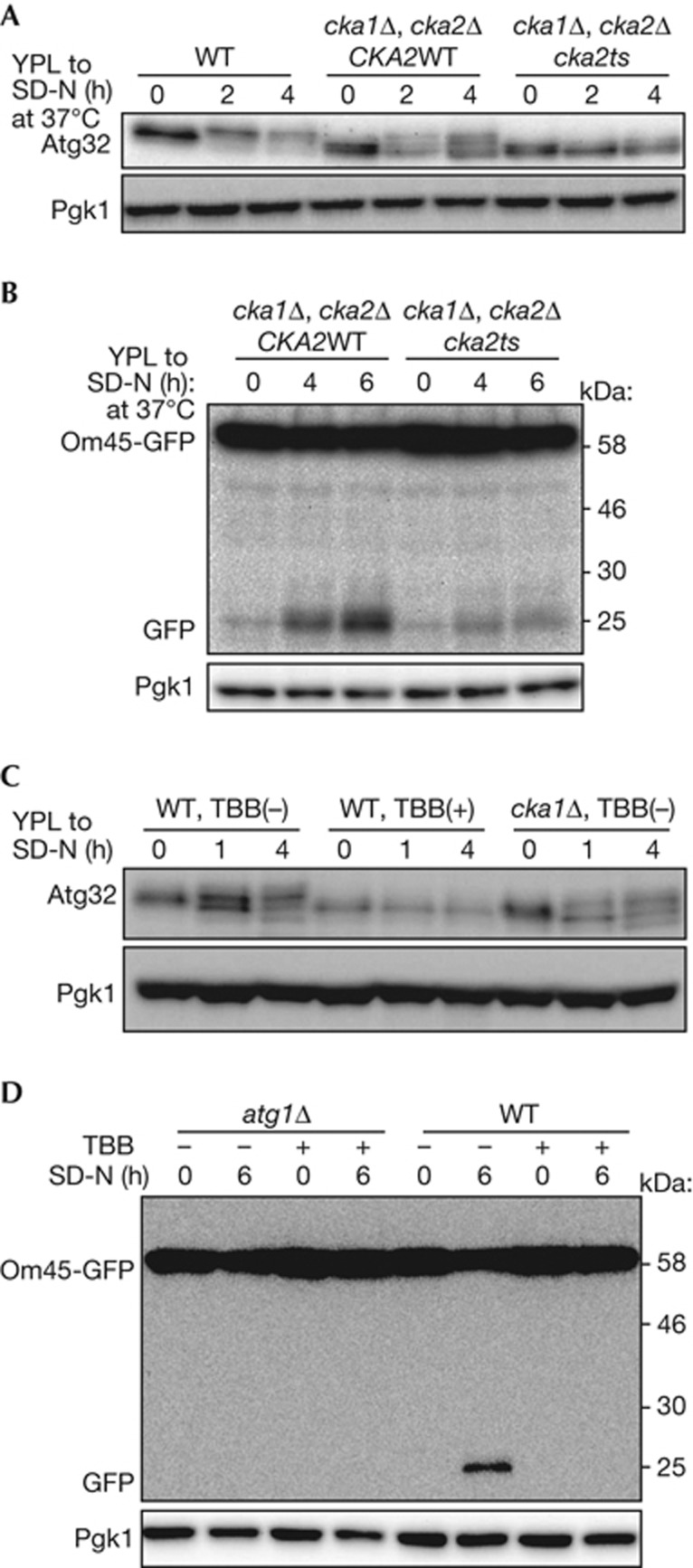

As shown in Fig 1B, phosphorylation of Atg32 was decreased but not completely blocked in cka1Δ and cka2Δ cells. This might be because Cka1 and Cka2 are functionally redundant. To determine whether CK2 activity is necessary for Atg32 phosphorylation, we developed a temperature-sensitive mutant of CK2 (cka1Δ cka2ts) [16] and observed phosphorylation of Atg32 after nitrogen starvation. As expected, phosphorylation of Atg32 was almost completely blocked in the cka1Δ cka2ts mutant at a non-permissive temperature (37 °C), while efficient and partial phosphorylation of Atg32 was observed in WT and cka1Δ cells, respectively (Fig 2A). We further analysed whether CK2 activity was required for mitophagy by Om45-GFP processing assay. As shown in Fig 2B, GFP processed from Om45-GFP in cka1Δ cka2ts mutant cells was barely detectable compared with that in cka1Δ cells, suggesting that CK2 activity is required for mitophagy (Fig 2B). To confirm the requirement for CK2 activity for Atg32 phosphorylation and mitophagy, we used 4,5,6,7-tetrabromobenzotriazole (TBB), a specific inhibitor of CK2. Cellular growth was severely suppressed by 70 μM TBB supplementation, suggesting that this concentration of TBB almost completely suppressed CK2 activity. Similar to that of the CK2 temperature-sensitive mutant, TBB suppressed Atg32 phosphorylation and mitophagy (Fig 2C,D).

Figure 2.

CK2 activity is required for Atg32 phosphorylation and mitophagy. (A,C) WT cells, cka1Δ/cka2Δ cells with vectors expressing intact CKA2, and cka1Δ/cka2Δ cells with vectors expressing temperature-sensitive cka2ts were cultured in YPL medium at 24 °C until the mid-log growth phase and then shifted to SD-N medium and cultured at 37 °C for 0, 2 or 4 h (A). WT and cka1Δ strains were cultured in YPL medium until the mid-log growth phase and then shifted to SD-N medium with or without 70 μM TBB supplementation and cultured for 0, 1 or 4 h (C). The phosphorylation status of Atg32 was observed by immunoblotting with anti-Atg32 and anti-Pgk1 antibodies.(B,D) Om45-GFP-expressing cka1Δ/cka2Δ cells with vectors expressing intact CKA2 or cka2ts were cultured in YPL medium at 24 °C until the mid-log growth phase and then shifted to SD-N at 37 °C for 0, 4 or 6 h (B). WT and atg1Δ cells expressing Om45-GFP were cultured in YPL medium until the mid-log growth phase and then shifted to SD-N with or without 70 μM TBB supplementation and cultured for 0 or 6 h (D). GFP processing was monitored by immunoblotting with anti-GFP and anti-Pgk1 antibodies. CK2, Casein kinase 2; GFP, green fluorescent protein; TBB, 4,5,6,7-tetrabromobenzotriazole; WT, wild type.

We next examined the requirement for CK2 activity for Atg32–Atg11 interaction. We expressed protein A-tagged Atg32 (ProA-Atg32) and HA-tagged Atg11 (HA-Atg11) in WT or cka1Δ cka2ts mutant cells and preformed protein A affinity isolation. HA-Atg11 was efficiently co-precipitated with ProA-Atg32 after nitrogen starvation in WT cells. However, co-precipitation of HA-Atg11 was dramatically decreased in the CK2 temperature-sensitive mutant at a non-permissive temperature (supplementary Fig S5A online). Similarly, co-precipitation of HA-Atg11 was dramatically decreased by TBB treatment (supplementary Fig S5B online). Thus, we concluded that CK2 activity is essential for Atg32 phosphorylation, the Atg32–Atg11 interaction and mitophagy. Because CK2 is essential for mitophagy, we speculated that overexpression of CK2 might enhance mitophagy. To test this, we overexpressed HA-Cka1 and HA-Ckb1 in WT cells and observed mitophagy by Om45-GFP processing assay. Contrary to our expectation, overexpression of CK2 did not affect mitophagy (supplementary Fig S5C online).

CK2 is not essential for other types of autophagy

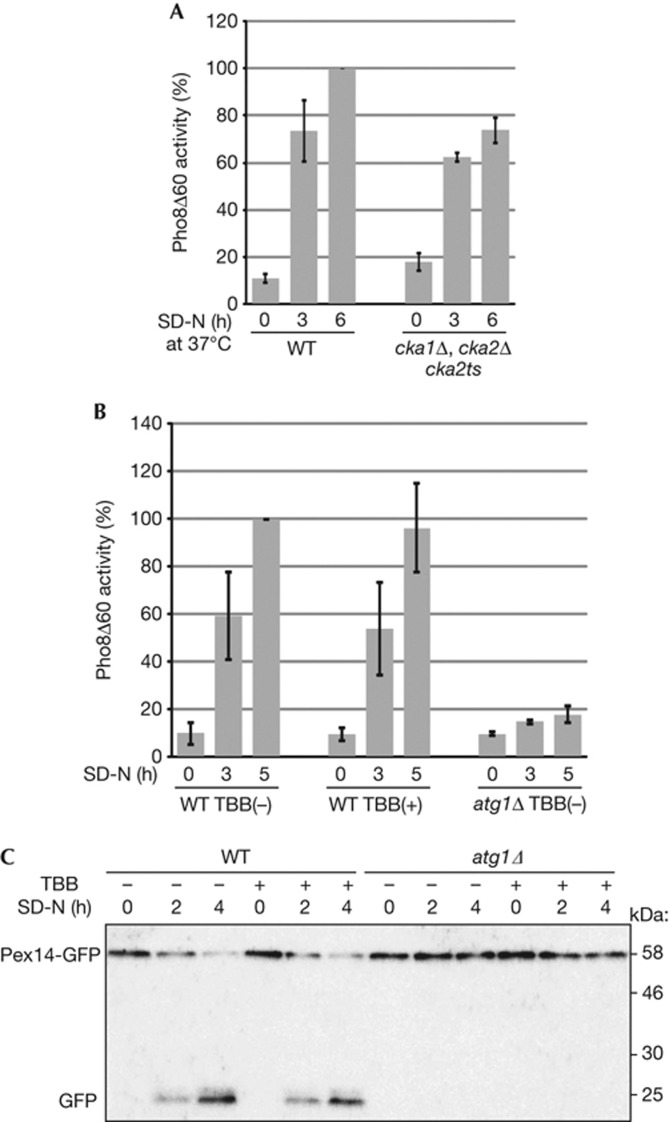

To evaluate whether CK2 is specifically required for mitophagy or other types of autophagy, we observed bulk macroautophagy, the Cvt pathway and pexophagy under CK2-suppressed conditions. To observe bulk macroautophagy, we used a Pho8Δ60 activity assay [17]. We found that the cka1Δ cka2ts mutant, as well as the cka1Δ or cka2Δ single deletion cells, showed a comparable increase in Pho8Δ60-dependent alkaline phosphatase activity similar to WT cells following nitrogen starvation (Fig 3A; supplementary Fig S6A online). Similarly, suppression of CK2 activity by TBB did not affect Pho8Δ60 activity (Fig 3B). To observe the Cvt pathway, we examined processing of precursor Ape1 to mature Ape1. We found that the cka1Δ cka2ts mutant showed efficient Ape1 maturation, whereas the atg1ts mutant blocked the maturation at non-permissive temperatures (supplementary Fig S6B online). Similarly, suppression of CK2 activity by TBB did not affect Ape1 maturation, whereas phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride blocked Ape1 maturation (supplementary Fig S6C online). Finally, we used GFP processing from the peroxisomal protein Pex14 tagged with GFP (Pex14-GFP) to observe pexophagy [18]. As shown in Fig 3C, pexophagy was not affected by administration of TBB. Thus, we concluded that CK2 is specifically required for mitophagy.

Figure 3.

CK2 activity is not essential for bulk macroautophagy and pexophagy. (A,B) WT (TKYM236) and CK2ts mutant (TKYM261) strains were grown in YPD medium and shifted to SD-N and cultured at 37 °C for 3 or 6 h (A). WT (TKYM236) and atg1Δ (TKYM256) strains were grown in YPD medium and shifted to SD-N with or without 70 μM TBB supplementation and cultured for 0, 3 or 5 h (B). Samples were collected and protein extracts assayed for Pho8Δ60 activity. The results represent the mean and standard deviation of three experiments. (C) WT and atg1Δ cells expressing Pex14-GFP were cultured with oleic acid containing medium for 19 h, and then shifted to SD-N with or without 70 μM TBB supplementation, cultured for 0, 2 or 4 h, and monitored for GFP processing by immunoblotting. CK2, Casein kinase 2; GFP, green fluorescent protein; TBB, 4,5,6,7-tetrabromobenzotriazole; WT, wild type; YPD, yeast extract-peptone-glucose.

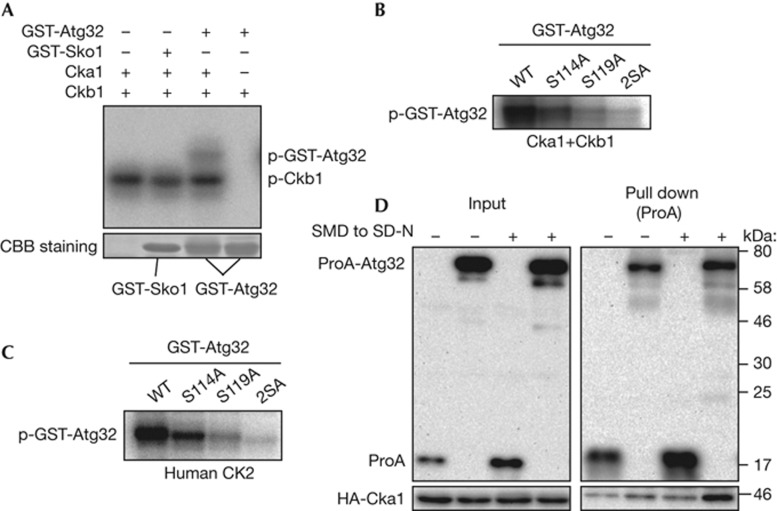

Atg32 is directly phosphorylated by CK2

Because CK2 is necessary for Atg32 phosphorylation, CK2 might directly phosphorylate Atg32. To evaluate this, we observed Atg32 phosphorylation by recombinant CK2 in vitro. Purified recombinant His-Cka1 and His-Ckb1 and [γ-32P]ATP were mixed with purified recombinant GST-Sko1 (amino-terminal 214 amino acids; negative control) or purified recombinant GST-Atg32 (N-terminal 250 amino acids) and incubated in vitro. As shown in Fig 4A and as previously reported by Pagano et al [19], Ckb1 was auto-phosphorylated by CK2 (Fig 4A, p-Ckb1). Atg32 was also phosphorylated by CK2, whereas Sko1, a known substrate of Hog1, was not phosphorylated in vitro. The phosphorylation of Atg32 in vitro was inhibited by TBB, suggesting that Atg32 was phosphorylated by CK2 and not by other potentially contaminating proteins (supplementary Fig S7A online). To evaluate whether the phosphorylated residues were serines 114 and 119 on Atg32, which are known to be phosphorylated in vivo [11], we purified recombinant GST-Atg32 with serine 114 mutated to alanine, serine 119 mutated to alanine or both serines mutated to alanines (2SA) and performed the CK2 phosphorylation assay. Both Atg32-S114A and Atg32-S119A were phosphorylated by CK2 (57±5% and 23±4%, respectively, compared with Atg32 WT), whereas Atg32-2SA, which still contains 37 serines and 16 threonines, was negligibly phosphorylated in vitro by CK2 (Fig 4B). Similar results were obtained when human recombinant CK2 was used (Fig 4C; supplementary Fig S7B online). Thus, we concluded that serines 114 and 119 on Atg32 are phosphorylated by CK2. The minimum consensus motif for phosphorylation by CK2 is SXXE/D, although there are many exceptions [20]. Although both serine 114 and serine 119 comply with this motif (114S-S-S-D and 119S-E-E-E, respectively), serine 119 is dominantly phosphorylated compared with serine 114 by CK2 in vitro (Fig 4B,C). This tendency is consistent with our previous observation in vivo that serine 119 is dominantly and serine 114 is subordinately phosphorylated when mitophagy is induced [11].

Figure 4.

Atg32 is directly phosphorylated by CK2. (A) In vitro phosphorylation assay of Atg32 by CK2. Recombinant GST-Atg32 (1–250) or GST-Sko1 (1–214) was phosphorylated by recombinant His-Cka1 and/or His-Ckb1 in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The labelled proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE; an autoradiograph (upper panel), and Coomassie brilliant blue-stained images (lower panel) of the gel are shown. (B,C) Recombinant GST-Atg32 (1–250) WT and mutant versions (serine 114 to alanine, serine 119 to alanine or both serines to alanines (2SA)) was phosphorylated by recombinant yeast CK2 (B) or human CK2 (C) in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP. The labelled proteins were resolved by SDS–PAGE, and an autoradiograph image is shown. (D) WT cells expressing HA-Cka1 and protein A (ProA)-tagged Atg32 or ProA only were grown in SMD medium until the mid-log phase and then starved in SD-N for 0 or 1 h. ProA-Atg32 was precipitated using IgG-Sepharose from cell lysates. The left panel shows an immunoblot of total cell lysate and the right panel shows the IgG precipitates, which were probed with anti-HA and anti-ProA antibodies. CK2, Casein kinase 2; GST, glutathione S-transferase; IgG, immunoglobulin G; SDS–PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; SMD, synthetic minimal medium with glucose; WT, wild type.

CK2 has the potential to interact with Atg32

If CK2 directly phosphorylates Atg32 in vivo, we speculated that it might be possible to observe interaction between the two. Accordingly, we expressed ProA only (negative control) or ProA-Atg32 and HA-Cka1 in WT cells and performed protein A affinity isolation. Although HA-Cka1 barely co-precipitated with ProA-Atg32 when cultured in synthetic minimal medium with glucose (SMD), HA-Cka1 co-precipitated with ProA-Atg32 after nitrogen starvation (Fig 4D, SD-N). Similarly, HA-Ckb1 also co-precipitated with ProA-Atg32 during nitrogen starvation (supplementary Fig S8A online). This Atg32–CK2 interaction was not affected by Atg32-2SA mutation (supplementary Fig S8B online). To mimic mitophagy-inducing conditions completely, we pre-cultured cells in synthetic minimal medium with lactate, then shifted to starvation medium, and observed the Atg32–CK2 interaction. Unexpectedly, we did not observe an Atg32–CK2 interaction in these conditions (supplementary Fig S8C online). It is generally thought that enzyme–substrate interactions are weak and occur only transiently, and thus, they are difficult to observe [21]. Accordingly, and because we could detect the interaction when cells were pre-cultured in SMD and starved, it is highly possible that CK2 interacts with Atg32 weakly and transiently. However, the weakness of the Atg32–CK2 interaction might make it difficult to detect the interaction when cells are pre-cultured in synthetic minimal medium with lactate and then starved.

Hog1, but not Slt2, is upstream of CK2

Mao et al reported that two mitogen-activated protein kinases, Hog1 and Slt2, and their upstream signalling pathways, are required for mitophagy [22]. We also reported that Hog1 is required for Atg32 phosphorylation, but that it does not directly phosphorylate Atg32 [11]. It is, however, unclear whether Slt2 is related to Atg32 phosphorylation. Thus, we observed mitophagy and Atg32 phosphorylation in slt2Δ and hog1Δ cells. Although mitophagy was inhibited in both slt2Δ and hog1Δ cells, Atg32 phosphorylation was inhibited only in hog1Δ cells (supplementary Fig S9 online). This finding suggests that the Hog1, but not Slt2, signalling pathway is upstream of CK2 and regulate Atg32 phosphorylation, although further studies are required to understand how Hog1 regulates Atg32 phosphorylation by CK2.

Regulation of Atg32 phosphorylation by CK2

It is unclear how phosphorylation of Atg32 by CK2 is regulated. One possibility is that CK2 accumulates on mitochondria to phosphorylate Atg32 during starvation. To observe the localization of CK2, we tagged GFP on each of the CK2 components and observed their localization. When cells were cultured in YPD or YPL, the majority of CK2 localized in the nucleus, whereas some CK2 diffused within the cytoplasm (supplementary Figs S10, S11A, and S12A online). After nitrogen starvation, the majority of CK2 is still localized in the nucleus and not accumulated in mitochondria (supplementary Figs S11B and S12B online). Because CK2 is an abundant protein and a proportion of CK2 is always present in cytoplasm, it might be difficult to detect mitochondrially localized CK2 that transiently interacts and phosphorylates mitochondrial Atg32. Another possibility is that nitrogen starvation increases the affinity of the Atg32–CK2 interaction. This possibility is in part supported by our finding that the Atg32–CK2 interaction was observed only when cells were pre-cultured in SMD and then shifted to SD-N (Fig 4D). However, it is unclear why the affinity of Atg32 for CK2 should increase upon starvation.

It is also unclear whether the regulatory subunits of CK2 (Ckb1 and Ckb2) are required for mitophagy, because ckb1Δ/ckb2Δ cells still induced mitophagy (Fig 1C). On the other hand, deletion of one of the regulatory subunits delayed Atg32 phosphorylation (Fig 1B), suggesting that the regulatory subunits are important in mitophagy. We observed Atg32 phosphorylation by Cka1 supplemented with or without Ckb1 in vitro and found that the presence of Ckb1 did not affect or partially suppressed Atg32 phosphorylation (supplementary Fig S7C online). These findings are controversial, and we cannot draw a conclusion about the importance of the regulatory subunits of CK2 for mitophagy. Further studies are needed.

In this study, we showed that CK2 is essential for mitophagy in yeast. In mammalian cells, misfolded proteins and protein aggregates are sometimes polyubiquitinated and eliminated by selective autophagy. Recently, it was shown that CK2 phosphorylates serine 403 on p62/SQSTM1, which then increases its affinity for polyubiquitinated chains and promotes the selective autophagic degradation of misfolded or aggregated proteins [23]. Because both Atg32 and p62 function as cargo receptors for selective autophagy, it is reasonable that a common kinase, CK2, phosphorylates both receptors for activation. In addition, p62 is thought to be a receptor for Parkin-related mitophagy in mammalian cells [24]. In this case, the ubiquitin ligase Parkin ubiquitinates the mitochondrial outer membrane proteins and p62 interacts with polyubiquitinated proteins for selective autophagic degradation. Because CK2 phosphorylates p62 for activation [23], CK2 might have a common and important role in mitophagy induction in both yeast and mammalian cells.

Methods

Strains and media. The yeast strains used in this study are listed in supplementary Table S2 online. The yeast knockout collection (BY4742 background, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, MA) was used for kinase screens. Media and growth conditions are given in the supplementary information online.

Assays for mitophagy, macroautophagy and pexophagy. To monitor mitophagy, the Om45-GFP processing assay was performed as previously described [15, 25]. To monitor macroautophagy, the alkaline phosphatase activity of Pho8Δ60 was measured as previously described [17]. To monitor pexophagy, the Pex14-GFP processing assay was performed as previously described [18].

In vitro kinase assay. For the in vitro kinase assay, we used a previously described method [11]. More details are available in the supplementary information online.

Protein A affinity pull-down assay. Cells expressing HA-Atg11, HA-Cka1 or HA-Ckb1 and ProA-tagged Atg32 were cultured in SMD or synthetic minimal medium with lactate medium until the mid-log growth phase, and then shifted to SD-N for 0 or 1 h. Cells were collected and lysed with glass beads in immunoprecipitation buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 1 mM phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride and proteinase inhibitors), and then centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was mixed with immunoglobulin G-Sepharose at 4 °C for 6 h. The Sepharose was washed with ice-cold wash buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 500 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 0.5% Triton X-100) five times, and the sample was eluted by sodium dodecyl sulphate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis loading buffer. The elution samples were observed by immunoblotting with anti-HA and anti-protein A antibodies.

Supplementary information is available at EMBO reports online (http://www.emboreports.org).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel J. Klionsky (University of Michigan) for providing the yeast strains and plasmids. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (23689032 and 25117714) and the Special Coordination Funds for Promoting Science and Technology (MEXT).

Author contributions: T.K., Y.H., Y.K., X.J., T.G., Y.O., M.A. and T.S. performed the research; T.K. designed the research; T.K., Y.A., T.U. and D.K. supervised the project; T.K. wrote the paper.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nakatogawa H, Suzuki K, Kamada Y, Ohsumi Y (2009) Dynamics and diversity in autophagy mechanisms: lessons from yeast. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 10: 458–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K (2013) Selective autophagy in budding yeast. Cell Death Differ 20: 43–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemasters JJ (2005) Selective mitochondrial autophagy, or mitophagy, as a targeted defense against oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and aging. Rejuvenation Res 8: 3–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweers RL et al. (2007) NIX is required for programmed mitochondrial clearance during reticulocyte maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 19500–19505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandoval H, Thiagarajan P, Dasgupta SK, Schumacher A, Prchal JT, Chen M, Wang J (2008) Essential role for Nix in autophagic maturation of erythroid cells. Nature 454: 232–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ (2008) Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. J Cell Biol 183: 795–803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vives-Bauza C et al. (2010) PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 378–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto K, Kondo-Okamoto N, Ohsumi Y (2009) Mitochondria-anchored receptor Atg32 mediates degradation of mitochondria via selective autophagy. Dev Cell 17: 87–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanki T et al. (2009) A genomic screen for yeast mutants defective in selective mitochondria autophagy. Mol Biol Cell 20: 4730–4738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanki T, Wang K, Cao Y, Baba M, Klionsky DJ (2009) Atg32 is a mitochondrial protein that confers selectivity during mitophagy. Dev Cell 17: 98–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki Y, Kanki T, Hirota Y, Kurihara Y, Saigusa T, Uchiumi T, Kang D (2011) Phosphorylation of Serine 114 on Atg32 mediates mitophagy. Mol Biol Cell 22: 3206–3217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkey CD, Carlson M (2006) A specific catalytic subunit isoform of protein kinase CK2 is required for phosphorylation of the repressor Nrg1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Curr Genet 50: 1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montenarh M (2010) Cellular regulators of protein kinase CK2. Cell Tissue Res 342: 139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meggio F, Boldyreff B, Issinger OG, Pinna LA (1994) Casein kinase 2 downregulation and activation by polybasic peptides are mediated by acidic residues in the 55-64 region of the beta-subunit. A study with calmodulin as phosphorylatable substrate. Biochemistry 33: 4336–4342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanki T, Klionsky DJ (2008) Mitophagy in yeast occurs through a selective mechanism. J Biol Chem 283: 32386–32393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna DE, Rethinaswamy A, Glover CV (1995) Casein kinase II is required for cell cycle progression during G1 and G2/M in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem 270: 25905–25914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noda T, Matsuura A, Wada Y, Ohsumi Y (1995) Novel system for monitoring autophagy in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 210: 126–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiori F, Monastyrska I, Shintani T, Klionsky DJ (2005) The actin cytoskeleton is required for selective types of autophagy, but not nonspecific autophagy, in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell 16: 5843–5856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano MA, Sarno S, Poletto G, Cozza G, Pinna LA, Meggio F (2005) Autophosphorylation at the regulatory beta subunit reflects the supramolecular organization of protein kinase CK2. Mol Cell Biochem 274: 23–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meggio F, Pinna LA (2003) One-thousand-and-one substrates of protein kinase CK2? FASEB J 17: 349–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pusch S, Dissmeyer N, Schnittger A (2011) Bimolecular-fluorescence complementation assay to monitor kinase-substrate interactions in vivo. Methods Mol Biol 779: 245–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao K, Wang K, Zhao M, Xu T, Klionsky DJ (2011) Two MAPK-signaling pathways are required for mitophagy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Biol 193: 755–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto G, Wada K, Okuno M, Kurosawa M, Nukina N (2011) Serine 403 phosphorylation of p62/SQSTM1 regulates selective autophagic clearance of ubiquitinated proteins. Mol Cell 44: 279–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler S, Holmstrom KM, Skujat D, Fiesel FC, Rothfuss OC, Kahle PJ, Springer W (2010) PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nat Cell Biol 12: 119–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanki T, Kang D, Klionsky DJ (2009) Monitoring mitophagy in yeast: the Om45-GFP processing assay. Autophagy 5: 1186–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.