Abstract

Background. Psychotropic medications, in particular second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) and benzodiazepines, have been associated with harm in elderly populations. Health agencies around the world have issued warnings about the risks of prescribing such medications to frail individuals affected by dementia and current guidelines recommend their use only in cases where the benefits clearly outweigh the risks. This study documents the use of psychotropic medications in the entire elderly population of a Canadian province in the context of current clinical guidelines for the treatment of behavioural disturbances.

Methods. Prevalent and incident utilization of antipsychotics, benzodiazepines and related medications (zopiclone and zaleplon) were determined in the population of Manitobans over age 65 in the time period 1997/98 to 2008/09 fiscal years. Comparisons between patients living in the community and those living in personal care (nursing) homes (PCH) were conducted. Influence of sociodemographic characteristics on prescribing was assessed by generalized estimating equations. Non-optimal use was defined as the prescribing of high dose of antipsychotic medications and the use of combination therapy of a benzodiazepine (or zopiclone/zaleplon) with an antipsychotic. A decrease in intensity of use over time and lower proportions of patients treated with antipsychotics at high dose or in combination with benzodiazepines (or zopiclone/zaleplon) was considered a trend toward better prescribing. Multiple regression analysis determined predictors of non-optimal use in the elderly population.

Results. A 20-fold greater prevalent utilization of SGAs was observed in PCH-dwelling elderly persons compared to those living in the community. In 2008/09, 27% of PCH-dwelling individuals received a prescription for an SGA. Patient characteristics, such as younger age, male gender, diagnoses of dementia (or use of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor) or psychosis in the year prior the prescription, were predictors of non-optimal prescribing (e.g., high dose antipsychotics). During the period 2002/3 and 2007/8, amongst new users of SGAs, 10.2% received high doses. Those receiving high dose antipsychotics did not show high levels of polypharmacy.

Conclusions. Despite encouraging trends, the use of psychotropic medications remains high in elderly individuals, especially in residents of nursing homes. Clinicians caring for such patients need to carefully assess risks and benefits.

Keywords: Antipsychotic, Benzodiazepines, Elderly, Prescribing, Psychotropic

Introduction

Antipsychotic medications have been prescribed to elderly persons mainly for the treatment of behavioural disturbances of dementia (Chan, Lam & Chen, 2011; Leslie & Rosenheck, 2012; Lee et al., 2004; Tariot, 2004). The safety and effectiveness of both first-generation (FGAs; e.g., haloperidol and phenothiazines) and second-generation antipsychotic agents (SGAs; e.g., risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine) have been questioned and severe adverse events, including death, have been reported in elderly patients treated with antipsychotics in both RCTs and observational studies (Ray et al., 2001; Percudani et al., 2005; Wang, Schneeweiss & Avorn, 2005; Schneeweiss et al., 2007; Trifiro et al., 2007; Mehta et al., 2010; Sacchetti, Turrina & Valsecchi, 2010; Mittal et al., 2011; Vasilyeva et al., 2013). Because of the strong evidence of harm caused by these agents to elderly patients affected by dementia, Health Canada and other health agencies worldwide issued several warnings between 2002 and 2005 (Health Canada, 2002; Health Canada, 2004; Health Canada, 2005; The Food and Drug Administration, 2008; European Medicines Agency (EMEA), 2009). Benzodiazepines (BZDs) and other psychotropic medications have also been associated with harm (e.g., increased risk of falls) in older adults (Eigenbrodt et al., 2000; Ayer et al., 2007; Barlett, Abrahamowicz & Grad, 2009; Hill & Wee, 2012), and evidence-based practice guidelines advise clinicians to consider all factors before prescribing potent medications to frail individuals (APA Practice Guidelines, 2007; Peisah, Chan & McKay, 2011; Jeste, Blazer & Casey, 2008; Gauthier, Patterson & Chertkow, 2012). The objectives of this study were:

-

1.

to evaluate the use of psychotropic medications (i.e., antipsychotics and benzodiazepines) in the elderly population of a Canadian province in light of health agency warnings and optimal prescribing guidelines;

-

2.

to determine predictors of non-optimal use of psychotropic medication in elderly persons.

Methods

This retrospective population-based study received ethics approval from the Research Ethics Board of the University of Manitoba. The study was conducted in full compliance with the Personal Health Information Act of Manitoba (Personal Health Information Act of Manitoba, 2013) and approved by the provincial Health Information Privacy Committee.

Data for the study were obtained from the administrative health care databases of the Manitoba Population Health Research Data Repository, housed at the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. The databases include de-identified information on the entire population of the province and the use of a consistent set of quasi-identifiers permits the building of health histories of non-identifiable individuals across files and time. Nearly all contacts with the universal provincial health care system, including physicians, hospitals, personal care (nursing) home (PCH) residence, and pharmaceutical dispensations are recorded. All registered individuals possess a 9-digit personal health identification number (PHIN), which is encrypted to protect privacy. The following databases were accessed: (1) population registry, (2) hospital abstracts, (3) medical services, (4) Drug Product Information Network (DPIN) prescription records, (5) PCH records, (6) vital statistics and (7) prescriber characteristics.

Records of physician reimbursement for medical care (ambulatory care visits and hospitalizations) are submitted under a fee-for-service arrangement and contain information on patient diagnosis based on the International Classification of Diseases, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes) (International Classification of Diseases, 2013). Records of dispensed prescriptions (DPIN) available through retail pharmacies contain data on the date of dispensing, drug name, strength, dosage form, and quantity, and the 8-digit drug identification number (DIN). Diagnoses can be retrieved from the hospital abstracts and medical services databases and linked with the population registry and vital statistics for demographic characteristics of patients and dates of death. Prescriber characteristics focus on the prescriber who wrote the incident prescription.

Region of residence (urban vs. rural) was determined by the postal codes registered with Manitoba Health. The distribution of urban (major cities of the province, Winnipeg and Brandon) versus rural (small communities across the province) population is approximately 72% versus 28% (Statistics Canada, 2013).

Socioeconomic status (SES) was determined on the basis of the median neighbourhood income quintiles from Statistics Canada (Statistics Canada, 2013): low income included the lowest and second lowest quintiles, high income included the three highest quintiles.

We included all Manitoba residents aged 65 years and older over an 11-year period. Separate analyses were conducted to evaluate prevalent and incident utilization of antipsychotics, BZDs, zopiclone (ZOP) and zaleplon (ZAL) in elderly persons living in the community or in PCH. SGAs available in Manitoba at the time of the study were clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine and quetiapine. Clozapine utilization in the elderly population of Manitoba has been negligible and restricted to patients with treatment-resistant-schizophrenia; therefore, it was not included in the analyses. Please refer to Appendix 1 for a complete list of BZDs and related medications. It is important to note that ZAL was discontinued in Canada by the manufacturer in September 2007 (Health Canada, 2013). Incident users were defined as individuals who were registered with the provincial health care system and had not received a prescription for the medication of interest in the year prior to the first prescription. Prevalence of use was also evaluated as defined-daily-dose (DDD) per 1,000 patients per day, which represented a measurement of intensity of use. The DDD is the average daily dose for a medication dispensed for the main indication in usual practice and is calculated according to the guidelines of the WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology (World Health Organization, 2013). The time frame of the study was between 1997/98 and 2008/09 by fiscal year (01 April to 31 March for each year). Generalized estimating equation (GEE) modeling (Vittinghoff, Glidden & Shiboski, 2012) was used to assess the influence of sociodemographic characteristics (age, sex, region of residence and SES) on the use of medications over time.

Non-optimal use definitions included incident prescription of high dose SGAs (i.e., ≥1.5 mg/day for risperidone, ≥10 mg/day olanzapine, ≥200 mg/day quetiapine) (World Health Organization, 2013) within the first year of use, use of SGAs in PCH residents with a concomitant prescription of an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (AChEI) (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine) within the same year, or a concomitant prescription of an antipsychotic and a BZD, ZOP or ZAP within the same quarter. Other medications such as memantine that can be prescribed to individuals with dementia were not included in the analysis because of negligible utilization in the province and/or because of overlapping prescribing with an AChEI.

Logistic regression modeling was used to identify predictors of non-optimal use. Variables included in the model were: prescribers’ characteristics (e.g., age, sex, speciality, type of practice, hospital affiliation), patient sociodemographic characteristics and measures of health services utilization in the year prior to the first antipsychotic prescription (i.e., number of hospitalizations and ambulatory visits, number of medications, use of AChEIs, psychosis diagnosis identified by ICD9-CM 295-299, ICD–10–CM: F2, F3, F84, R410, co-morbidities as assessed by the number of major Aggregated Diagnostic Groups (ADGs), as defined in the Johns Hopkins ACG® (Adjusted Clinical Group) Case-Mix System (software version 9) (Reid et al., 2013; The Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, 2013). Since time effects are important in changing prescribing patterns, optimal use evaluations were conducted in incident users between 2002/03 and 2008/09, as this was the interval that would best assess the possible effect of the warnings.

Analyses were performed using SAS® statistical software, version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Utilization: community-dwelling population

A total of 143,491 community-dwelling adults over 65 years of age represented the population denominator in 1997/98, and 153,189 in 2008/09.

Prevalent utilization of SGAs increased from 0.6 to 13.5 users per 1,000 community-dwelling older adults while the use of FGAs declined from 12.8 to 5.9 users per 1,000. Risperidone was the most prescribed agent with an increase in prevalence from 0.6 to 6.5 per 1,000 (olanzapine use increased from 0.05 to 3.7 per 1,000 and quetiapine use increased from 0.07 to 3.9 per 1,000) during the study period. The use of BZDs was greater than the use of antipsychotics in this population but little change in prevalence was observed (108.6 to 109.1 users per 1,000); however, ZOP and ZAL use increased from 13.6 to 53.0 users per 1,000 during the same time interval. Prevalence of users receiving a combination of SGAs and BZD (or ZOP, ZAL) increased from 0.2 to 5.61 per 1,000.

Dose intensity of SGAs increased from 0.2 DDD per 1,000 in 1997/98 to a peak of 6.5 per 1,000 in 2004/05 and subsequently decreased to 4.9 by the end of the study period, 2008/09. For BZDs the change in DDD was small (from 65.2 to 68.6 per 1,000) while for ZOP and ZAL, it increased from 9.5 to 49.6 per 1,000.

Incidence rates per quarter increased significantly for SGA users and for users of combination therapy over the time period of the study. Age and gender had a significant effect with greater incident utilization in the 85 and over group compared to the 65–84 year of age group for all medications and in females compared to males for the SGAs. Higher incident use in males was observed for the combination of BZDs (or ZOP, ZAL) and SGAs (Table 1).

Table 1. Incident use in community-dwelling older adults (65+).

| Medications | SGAs | FGAs | BZDs/ZOP, ZAL | BZDs/ZOP, ZAL + SGA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Users/1,000 Year 1998 | 0.21 | 1.88 | 13.14 | 0.06 |

| Users/1,000 Year 2009 | 1.63 | 1.03 | 13.66 | 0.15 |

| Change in rate per quarter | 1.02* | 0.98* | 1.00 NS | 1.01* |

| Age effect 65–84 vs. 85+ | 0.44* | 0.85* | 1.08* | 0.60* |

| SES effect low vs. high | 1.10* | 1.14* | 1.00 NS | 1.09 NS |

| Region effect rural vs. urban | 0.88* | 1.51* | 1.01 NS | 1.02 NS |

| Sex effect male vs. female | 0.91* | 0.86* | 0.73* | 1.17* |

Notes.

Results for change in quarterly rate, age, SES, region and sex effects are presented as relative rates (adjusted for age, SES, region, sex and time).

- SGAs

- second generation antipsychotics

- FGAs

- first generation antipsychotics

- BZDs/ZOP, ZAL

- benzodiazepines, zopiclone, zaleplon

- NS

- not significant

- SES

- socioeconomic status

Indicates a statistically significant effect (p < 0.05).

Utilization: PCH-dwelling population

A total of 8,516 PCH-dwelling older adults represented the denominator for this population in 1997/98 and 8,818 in 2008/09.

Prevalent utilization of SGAs increased from 15.0 to 268.5 users per 1,000 PCH-dwelling older adults while the use of FGAs declined from 169.3 to 47.7 users per 1,000. Risperidone was again the most commonly prescribed agent with an increase in prevalence from 15.0 to 167.0 per 1,000 (quetiapine use increased from 0.9 to 67.6 per 1,000 and olanzapine use increased from 0.8 to 49.1 per 1,000) during the study period. While the use of BZDs declined slightly from 170.7 to 161.3 per 1,000, the use of ZOP and ZAL increased dramatically from 15.0 to 102.6 users per 1,000 during the same time. Prevalence of users receiving a combination of SGAs and BZD, ZOP or ZAL increased from 4.8 to 90.8 per 1,000.

Dose intensity of SGAs increased from 5.5 DDDs per 1,000 in 1997/98 to a peak of 85.5 per 1,000 in 2003/04 and subsequently declined to 70.7 by the end of the study period, 2008/09. For BZDs the increase in DDD was small from 82.1 to 84.9 per 1,000 between 1997/98 and 2003 with a decline to 67.0 by the end of the study period. For ZOP or ZAL, there was a significant increase from 9.5 to 49.6 per 1,000 over the entire study period.

Incidence rates per quarter increased significantly for SGAs users and for users of combination therapy over the time period of the study. Refer to Table 2 for details of the age, residence, and sex effects on incident use in this population.

Table 2. Incident use in personal care (nursing) home-dwelling older adults (65+).

| Medications | SGAs | FGAs | BZDs/ZOP, ZAL | BZDs/ZOP, ZAL + SGA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Users/1,000 Year 1998 | 3.76 | 19.61 | 26.66 | 0.70 |

| Users/1,000 Year 2009 | 21.09 | 8.62 | 22.91 | 4.45 |

| Change in rate per quarter | 1.01* | 0.98* | 1.00 NS | 1.01* |

| Age effect 65–84 vs. 85+ | 1.21* | 1.36* | 1.13* | 1.40* |

| Region effect rural vs. urban | 0.78* | 0.85* | 0.79* | 0.74* |

| Sex effect male vs. female | 1.22* | 1.38* | 1.09* | 1.48* |

Notes.

Results for change in quarterly rate, age, region and sex effects are presented as relative rates (adjusted for age, region, sex and time). Individuals residing in PCH do not have values for SES.

- SGAs

- second generation antipsychotics

- FGAs

- first generation antipsychotics

- BZDs/ZOP, ZAL

- benzodiazepines, zopiclone, zaleplon

- NS

- not significant

- SES

- socioeconomic status

Indicates a statistically significant effect (p < 0.05).

Optimal use

There were 12,878 total incident users (community and PCH-dwelling) of antipsychotic medications (FGAs and SGAs) between 2002/03 and 2007/08. Of these, 1,319 (10.2%) went on to use a high dose of a SGA within the first year of therapy.

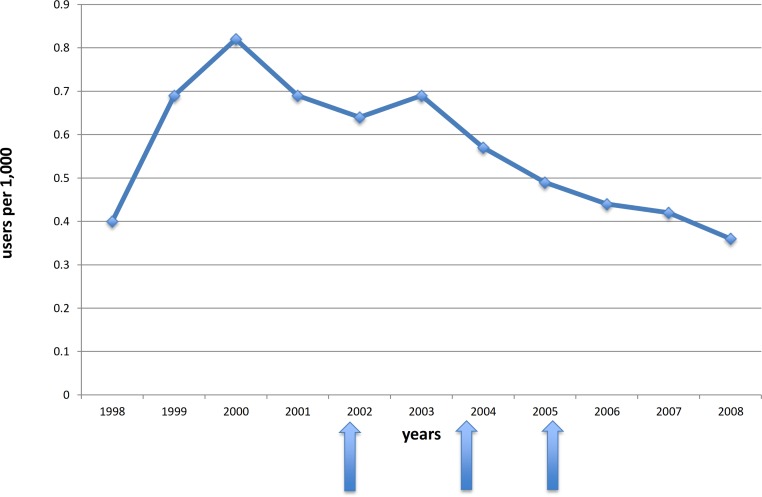

The rate of older adults who received a high dose SGA within the first year of being prescribed an SGA increased from 0.4 to 0.82 per 1,000 persons by 2000 and then declined to 0.36 per 1,000 in 2008 (Fig. 1). Among incident users of antipsychotic medications, the utilization of high dose SGAs declined from 112 to 94 per 1,000 from 2002 to 2008.

Figure 1. Crude incidence rates of high dose SGA use.

High doses were defined as: ≥1.5 mg/day for risperidone, ≥10 mg/day olanzapine, ≥200 mg/day quetiapine. The arrows indicate the times of the warnings issued by Health Canada.

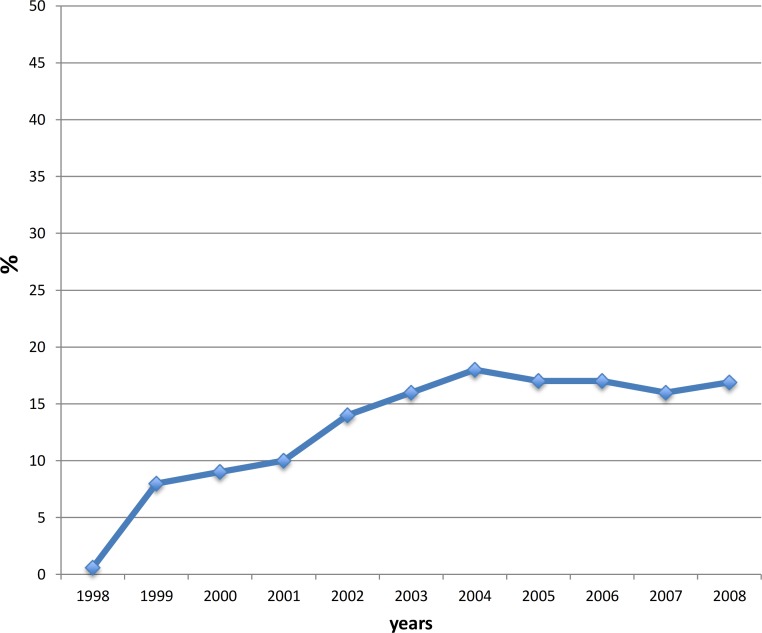

The proportion of PCH residents who were concomitantly prescribed an SGA and an AChEI in the same year increased over time from 0.2 to 17.8% in 2004 and slightly declined to 16.9% by the end of the study (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Proportion of PCH residents receiving an SGA in combination with AChEIs.

PCH, personal care home (nursing home); SGA, second-generation antipsychotic; AChEI, acetylcholinesterase inhibitor.

Patients were more likely to receive a high dose SGA if they were male, had received a prescription for an AChEI or had a diagnosis of psychosis within the year prior to the first prescription (Table 3). Very old patients and those treated with a greater number of different medications were less likely to receive a high dose SGA. Prescriber characteristics and use of other health care services were not significantly different.

Table 3. Factors predictive of high dose SGAs within the first year of use.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 | <0.0001 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 1.18 | 1.04–1.33 | 0.0095 |

| Number of other medications | 0.97 | 0.96–0.98 | <0.0001 |

| AChEI prescribed in the year prior to Rx | 1.28 | 1.08–1.51 | 0.0041 |

| Diagnosis for psychosis in the year prior to Rx | 1.52 | 1.34–1.73 | <0.0001 |

Notes.

- ACHEI

- acetylcholinesterase inhibitor (donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine)

- OR

- odds ratio

- Rx

- prescription

Discussion

We observed a significant increase in antipsychotic utilization in this elderly Canadian population. This is consistent with other reports from Canada (Valiyeva et al., 2008; Alessi-Severini et al., 2008; The Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2009), Europe (Martinez, Jones & Rietbrock, 2013; Schulze et al., 2013) and the US (Kales et al., 2011). Greater utilization of SGAs was observed in urban elderly persons and in particular among PCH residents. In fact, a 20-fold greater utilization was observed in PCH-dwelling elderly when compared to those living in the community. By the end of the study period, more than 25% of PCH-dwelling older individuals had received an SGA. Prevalence of BZD use remained above 10% in both community- and PCH-dwelling elderly over the time period of the study, while ZOP and ZAL utilization increased significantly. We observed greater use of FGAs amongst rural community dwelling elderly, but not among rural PCH dwellers. This could possibly be explained by off-label use of FGAs, such as treatment of chemotherapy-related nausea. Another reason could be a slower adoption of the newer agents by more isolated practice sites.

It seems that prescribers in the province of Manitoba have somewhat responded to warnings about potential harm to the elderly populations from treatment with SGAs (Health Canada, 2005; Health Canada, 2002; Health Canada, 2004; The Food and Drug Administration, 2008; European Medicines Agency (EMEA), 2009): the dose intensity declined in community-dwelling and reached a plateau in PCH-dwelling residents after the warnings were issued and only a minority (approximately 10%) received potentially inappropriate high doses of antipsychotic medications. Even though a decline would have been desirable, the sign of a lower incidence of new prescriptions can be interpreted as a positive trend. As well, the proportion of new users of SGAs who were also prescribed AChEIs reached a plateau after the warnings of serious adverse events in elderly individuals with dementias were released; however, no causality can be inferred as the study was not designed to assess the effects of an intervention, but to observe changing in prescribing patterns. While some findings might be difficult to interpret, the higher use of SGAs in PCH reflects a reality of a sicker population more susceptible to psychosis and agitation secondary to dementia; moreover, the observation that males seem more likely to receive high dose SGAs can be interpreted with a higher incidence of symptoms of aggression in male dementia patients. On the other hand, the observed lower occurrence of high dose SGAs in very old patients and/or on multiple therapies appears to be consistent with appropriate prescribing to frail individuals. Clinical studies are needed to confirm these assumptions.

Limitations to measures of optimal use of prescription medications using administrative databases include the lack of clinical information regarding severity of symptoms, use of over-the-counter medications, alcohol use and parameters of quality of life. Because of the lack of clinical outcome information, this study does not allow for assessment of appropriateness in all cases; numerous clinical characteristics may indicate that medications such as high dose SGAs may in fact be appropriate therapy for a particular patient at a particular time with appropriate close monitoring and follow up.

It is important to note also that in Manitoba, up to 27% of PCHs do not have medications filled through community pharmacies (Doupe, Brownell & Kozyrskyj, 2006) and are, therefore, not captured in the DPIN system; however, the proportion of elderly patients who reside in PCHs is limited (less than 6%) and no evidence of significant differences in patients’ characteristics has been shown among all PCHs in the province (Doupe, Brownell & Kozyrskyj, 2006). As a consequence, the missing data should not introduce a selection bias nor affect the validity of the results. A strength of these analyses is, in fact, in the comprehensive nature of the administrative health claims data, which include nearly all Manitobans: our results are not affected by sampling errors or recall bias. Furthermore, all studied psychotropic medications are available as unrestricted benefits on the provincial formulary, which allowed access to medications to be unaffected by SES and reimbursement conditions. For the PCH-dwelling older adults, medications are likely administered by PCH staff, so medication adherence is assured.

In conclusion, despite encouraging trends, the use of psychotropic medications remains high in elderly individuals, especially in residents of PCH. Clinicians caring for such patients need to carefully assess risks and benefits. Current recommendations call for the use of pharmacotherapy only when psychotic symptoms and agitation are persistent, recurrent or cause clinically significant functional disruption; the lowest possible effective dose of antipsychotics should be used when necessary and a regular monitoring of efficacy, safety and tolerability should be conducted (APA Practice Guidelines, 2007; Peisah, Chan & McKay, 2011; Jeste, Blazer & Casey, 2008; Gauthier, Patterson & Chertkow, 2012).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy, University of Manitoba, for use of data contained in the Population Health Research Data Repository under project 2008/2009–24, and derived form data provided by Manitoba Health. This work was part of a request of Manitoba Health; however, the results and conclusions are those of the authors and no official endorsement by Manitoba Health, the Manitoba Centre for Health Policy or other data providers is intended or should be inferred.

Appendix 1.

Benzodiazepines and related medications

Alprazolam, bramazepam, chlordiazepoxide, clobazam, clonazepam, diazepam, flurazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam, temazepam, triazolam, zaleplon and zopiclone.

Funding Statement

The financial support of the Department of Health at the Province of Manitoba is acknowledged as part of the contract between the University of Manitoba and Manitoba Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

Silvia Alessi-Severini is an Academic Editor for PeerJ. The authors do not have any other competing interests.

Author Contributions

Silvia Alessi-Severini and Colleen Metge conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed the data, wrote the paper.

Matthew Dahl performed the experiments, analyzed the data.

Jennifer Schultz wrote the paper, revisions; graphing.

Colette Raymond conceived and designed the experiments, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, wrote the paper.

Ethics

The following information was supplied relating to ethical approvals (i.e., approving body and any reference numbers):

This population-based study received ethics approval from the Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Manitoba (approval # H2008:250). The study was conducted in full compliance with the Personal Health Information Act of Manitoba and approved by the Health Information Privacy Committee (HIPC # 2008/2009–24).

References

- Alessi-Severini et al. (2008).Alessi-Severini S, Biscontri RG, Collins DM, Kozyrskyj A, Sareen J, Enns MW. Utilization and costs of antipsychotic agents: a Canadian population-based study: 1996–2006. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59(5):547–553. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.5.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- APA Practice Guidelines (2007).APA Work Group on Alzheimer’s Disease and other Dementias. Rabins PV, Blacker D, Rovner BW, Rummans T, Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Blass DM, Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. McIntyre JS, Charles SC, Anzia DJ, Cook IA, Finnerty MT, Johnson BR, Nininger JE, Schneidman B, Summergrad P, Woods SM, Berger J, Cross CD, Brandt HA, Margolis PM, Shemo JP, Blinder BJ, Duncan DL, Barnovitz MA, Carino AJ, Freyberg ZZ, Gray SH, Tonnu T, Kunkle R, Albert AB, Craig TJ, Regier DA, Fochtmann LJ. American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Second edition. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(12 Suppl):5–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayer et al. (2007).Ayer A, Antic V, Dulloo AG, Van Vliet BN, Montani JP. Hemodynamic consequences of chronic parasympathetic blockade with a peripheral muscarinic antagonist. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2007;293(2):H1265–H1272. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00326.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlett, Abrahamowicz & Grad (2009).Barlett G, Abrahamowicz M, Grad R, Sylvestre M-P, Tamblyn R. Association between risk factors for injurious falls and new benzodiazepine prescribing in elderly persons. BMC Family Practice. 2009;10:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Lam & Chen (2011).Chan W, Lam LC, Chen EY. Recent advances in pharmacological treatment of psychosis in late life. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2011;24:455–460. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32834a3f47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doupe, Brownell & Kozyrskyj (2006).Doupe M, Brownell M, Kozyrskyj A, Dik N, Burchill C, Dahl M, Chateau D, De Coster C, Hinds A, Bodnarchuk , J 2006. Using administrative data to develop indicators of quality care in personal care homes. Manitoba Centre for Health Policy. Available at http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/reference/pch.qi.pdf (accessed 8 May 2013)

- Eigenbrodt et al. (2000).Eigenbrodt ML, Rose KM, Couper DJ, Arnett DK, Smith R, Jones D. Orthostatic hypotension as a risk factor for stroke: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study, 1987–1996. Stroke. 2000;31(10):2307–2313. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.31.10.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency (EMEA) (2009).European Medicines Agency (EMEA) 2009. Safety aspects of antipsychotics in demented patients. Available at http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2010/03/WC500076323.pdf (accessed 21 June 2013)

- Gauthier, Patterson & Chertkow (2012).Gauthier S, Patterson C, Chertkow H, Gordon M, Herrmann N, Rockwood K, Rosa-Neto P, Soucy JP, CCCDTD4 participants 4th Canadian consensus conference on the diagnosis and treatment of dementia. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 2012;39(Suppl 5):S1–S8. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100015183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada (2002).Health Canada 2002. Important drug safety information: RISPERDAL* (risperidone) and cerebrovascular adverse events in placebo-controlled dementia trials - janssen-ortho inc. Available at http://www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall-alert-rappel-avis/hc-sc/2002/14164a-eng.php (accessed 1 May 2013)

- Health Canada (2004).Health Canada 2004. ZYPREXA (olanzapine) and cerebrovascular adverse events in placebo-controlled elderly dementia trials. Available at http://www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall-alert-rappel-avis/hc-sc/2004/14300a-eng.php (accessed 21 June 2013)

- Health Canada (2005).Health Canada 2005. Increased mortality associated with the use of atypical antipsychotic drugs in elderly patients with dementia. Available at http://www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall-alert-rappel-avis/hc-sc/2005/13696a-eng.php (accessed 1 May 2013)

- Health Canada (2013).Health Canada 2013. Drug product database. Available at http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/prodpharma/databasdon/index-eng.php (accessed 11 July 2013)

- Hill & Wee (2012).Hill KD, Wee R. Psychotropic drug-induced falls in older people. Drugs Aging. 2012;29(1):15–30. doi: 10.2165/11598420-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Classification of Diseases (2013).International Classification of Diseases 2013. Clinical Modification, Version 9 and Version 10 (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes). Available at http://www.icd9data.com (accessed 11 July 2013)

- Jeste, Blazer & Casey (2008).Jeste DV, Blazer D, Casey D, Meeks T, Salzman C, Schneider L, Tariot P, Yaffe K. ACNP White Paper: update on use of antipsychotic drugs in older adults with dementia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(5):957–970. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kales et al. (2011).Kales HC, Zivin K, Kim HM, Valenstein M, Chiang C, Ignacio RV, Ganoczy D, Cunningham F, Schneider LS, Blow FC. Trends in antipsychotic use in dementia 1999–2007. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2011;68(2):190–197. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee et al. (2004).Lee PE, Gill SS, Freedman M, Bronskill SE, Hillmer MP, Rochon PA. Atypical antipsychotic drugs in the treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: systematic review. BMJ. 2004;329(7457):75. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38125.465579.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie & Rosenheck (2012).Leslie DL, Rosenheck R. Off-label use of antipsychotic medications in Medicaid. American Journal of Management Care. 2012;18(3):e109–e117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, Jones & Rietbrock (2013).Martinez C, Jones RW, Rietbrock S. Trends in the prevalence of antipsychotic drug use among patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias including those treated with antidementia drugs in the community in the UK: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002080. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta et al. (2010).Mehta S, Johnson ML, Chen H, Aparasu RR. Risk of cerebrovascular adverse events in older adults using antipsychotic agents: a propensity-matched retrospective cohort study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2010;71(6):689–698. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05817yel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal et al. (2011).Mittal V, Kurup L, Williamson , Muralee S, Tampi RR. Risk of cerebrovascular adverse events and death in elderly patients with dementia treated with antipsychotic medications: a literature review of evidence. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias. 2011;26:10–28. doi: 10.1177/1533317510390351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peisah, Chan & McKay (2011).Peisah C, Chan DKY, McKay R, Kurrle SE, Reutens SG. Practical guidelines for the acute emergency sedation of the severely agitated older patient. Internal Medicine Journal. 2011;41:651–657. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percudani et al. (2005).Percudani M, Barbui C, Fortino I, Tansella M, Petrovich L. Second-generation antipsychotics and risk of cerebrovascular accidents in the elderly. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2005;25(5):468–470. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000178414.14685.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Personal Health Information Act of Manitoba (2013).Personal Health Information Act of Manitoba 2013. Available at http://www.gov.mb.ca/health/phia/ (accessed 21 June 2013)

- Ray et al. (2001).Ray WA, Meredith S, Thapa PB, Meador KG, Hall K, Murray KT. Antipsychotics and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(12):1161–1167. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.12.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid et al. (2013).Reid RJ, MacWilliam L, Roos NP, Bogdanovic B, Black C. Manitoba centre for health policy and evaluation. Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba; 1999. Measuring morbidity in populations: performance of the Johns Hopkins adjusted clinical group (ACG) case-mix adjustment system in Manitoba. Available at http://mchp-appserv.cpe.umanitoba.ca/reference/acg.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- Sacchetti, Turrina & Valsecchi (2010).Sacchetti E, Turrina C, Valsecchi P. Cerebrovascular accidents in elderly people treated with antipsychotic drugs: a systematic review. Drug Safety. 2010;33(4):273–288. doi: 10.2165/11319120-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneeweiss et al. (2007).Schneeweiss S, Setoguchi S, Brookhart A, Dormuth C, Wang PS. Risk of death associated with the use of conventional versus atypical antipsychotic drugs among elderly patients. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2007;176(5):627–632. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.061250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze et al. (2013).Schulze J, van den Bussche H, Glaeske G, Kaduszkiewicz H, Wiese B, Hoffmann F. Impact of safety warnings on antipsychotic prescriptions in dementia: nothing has changed but the years and the substances. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada (2013).Statistics Canada 2013. Population, urban and rural, by province and territory (Manitoba). Available at http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/demo62h-eng.htm (accessed 11 July 2013)

- Tariot (2004).Tariot PN. Clinical effectiveness of atypical antipsychotics in dementia. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65(Suppl 11):3–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Canadian Institute for Health Information (2009).The Canadian Institute for Health Information 2009. Antipsychotic use in seniors: an analysis focusing on drug claims, 2001 to 2007. Available at https://secure.cihi.ca/estore/productFamily.htm?pf=PFC1350&lang=en&media=0 (accessed 16 November 2012)

- The Food and Drug Administration (2008).The Food and Drug Administration 2008. FDA requests boxed warnings on older class of antipsychotic drugs. Available at http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2008/ucm116912.htm (accessed 21 June 2013)

- The Manitoba Centre for Health Policy (2013).The Manitoba Centre for Health Policy 2013. Concept: adjusted clinical group (ACG) - overview. Available at www.umanitoba.ca/faculties/medicine/units/mchp/resources/glossary.html (accessed 1 May 2013)

- Trifiro et al. (2007).Trifiro G, Verhamme KM, Ziere G, Caputi AP, Ch Stricker BH, Sturkenboom MC. All-cause mortality associated with atypical and typical antipsychotics in demented outpatients. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2007;16(5):538–544. doi: 10.1002/pds.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiyeva et al. (2008).Valiyeva E, Herrmann N, Rochon PA, Gill SS, Anderson GM. Effect of regulatory warnings on antipsychotic prescription rates among elderly patients with dementia: a population-based time-series analysis. Canadian Medical Association Journal/Journal de l’Association Medicale Canadienne. 2008;179(5):438–446. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.071540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilyeva et al. (2013).Vasilyeva I, Biscontri RG, Enns MW, Metge CJ, Alessi-Severini S. Adverse events in elderly users of antipsychotic pharmacotherapy in the province of Manitoba: a retrospective cohort study. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2013;33(1):24–30. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31827934a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vittinghoff, Glidden & Shiboski (2012).Vittinghoff E, Glidden DV, Shiboski SC, McCulloch CE. Regression methods in biostatistics - statistics for biology and health. Second Edition. NY: Springer Science+Business Media; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Schneeweiss & Avorn (2005).Wang PS, Schneeweiss S, Avorn J, Fischer MA, Mogun H, Solomon DH, Brookhart MA. Risk of death in elderly users of conventional vs. atypical antipsychotic medications. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;353(22):2335–2341. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2013).World Health Organization 2013. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology ATT/DD Index 2013. Available at http://www.whocc.no/atcddd (accessed 1 May 2013)