Abstract

The Dis1/TOG family plays a pivotal role in microtubule organization. In fission yeast, Alp14 and Dis1 share an essential function in bipolar spindle formation. Here, we characterize Alp7, a novel coiled-coil protein that is required for organization of bipolar spindles. Both Alp7 and Alp14 colocalize to the spindle pole body (SPB) and mitotic spindles. Alp14 localization to these sites is fully dependent upon Alp7. Conversely, in the absence of Alp14, Alp7 localizes to the SPBs, but not mitotic spindles. Alp7 forms a complex with Alp14, where the C-terminal region of Alp14 interacts with the coiled-coil domain of Alp7. Intriguingly, this Alp14 C terminus is necessary and sufficient for mitotic spindle localization. Overproduction of either full-length or coiled-coil region of Alp7 results in abnormal V-shaped spindles and stabilization of interphase microtubules, which is induced independent of Alp14. Alp7 may be a functional homologue of animal TACC. Our results shed light on an interdependent relationship between Alp14/TOG and Alp7. We propose a two-step model that accounts for the recruitment of Alp7 and Alp14 to the SPB and microtubules.

INTRODUCTION

Bipolar spindle formation during prometaphase is vital for accurate chromosome segregation in anaphase. The Dis1/TOG microtubule-associated protein (MAP) family is conserved ubiquitously in all eukaryotes from plants to fungi and humans (Ohkura et al., 2001). This family plays a pivotal role in microtubule organization, including the formation of mitotic bipolar spindles. In Homo sapiens somatic cells, ch-TOG is required for spindle organization around the poles (Gergely et al., 2003). X. laevis XMAP215, Drosophila melanogaster Msps, and Caenorhabditis elegans ZYG-9 are all required for stabilization of microtubules, such that mutations in Msps or ZYG-9 result in abnormally small spindles or spindle integrity defects, respectively (Gard and Kirschner, 1987; Matthews et al., 1998; Tournebize et al., 2000; Kinoshita et al., 2001). Saccharomyces cerevisiae STU2 plays an essential role in microtubule organization at the SPB (Wang and Huffaker, 1997). Collectively, it is postulated that this MAP family stabilizes microtubules; however, there are several reports that raise the possibility that it may also act as a microtubule-destabilizing factor (van Breugel et al., 2003; Shirasu-Hiza et al., 2003) or a factor that promotes microtubule dynamics (Kosco et al., 2001; Pearson et al., 2003).

Structurally, Dis1/TOG MAPs are divided into at least two parts. The N-terminal domains contain two to five repeats of the `TOG' domains that by themselves consist of multiple HEAT repeats (Ohkura et al., 2001). Proteins containing these HEAT repeats participate in a variety of biological processes and are involved in protein–protein interaction (Groves et al., 1999; Neuwald and Hirano, 2000). On the other hand, the C-terminal region is shown to possess a microtubule-binding activity, at least in vitro (Nakaseko et al., 1996; Nakaseko et al., 2001; Ohkura et al., 2001; Kinoshita et al., 2002).

Despite its intrinsic microtubule-binding activity in animal cells efficient localization of Dis1/TOG to the centrosome requires a second protein called TACC (Cullen and Ohkura, 2001; Lee et al., 2001). Although flies have only one TACC homologue (D-TACC), mammals possess at least three members (TACC1, 2, and 3) (Gergely et al., 2000; Raff, 2002). All TACC members contain the homologous coiled-coil region in their C terminus, designated the “TACC domain” (Gergely et al., 2000). It has been shown that D-TACC and Msps physically interact, but domains of each protein responsible for a physical interaction remain to be determined (Lee et al., 2001). Recently the C. elegans TACC homologue, called TAC-1, has been identified, where TAC-1 binds the C-terminal region of ZYG-9 and is required for microtubule assembly (Bellanger and Gönczy, 2003; Le Bot et al., 2003; Srayko et al., 2003). Despite this, the molecular manner in which TOG and TACC localize to the centrosome and microtubules is not known. Also mechanisms as to how TOG and TACC regulate microtubule organization remain elusive. In budding yeast, the spindle pole body (SPB) component Spc72 binds Stu2 (Chen et al., 1998; Pereira et al., 1999; Usui et al., 2003). However, its amino acid sequence shows no similarity to TACC, implying that Spc72 is not the TACC homologue; therefore, unlike the Dis1/TOG family, homologues of TACC in yeast remain to be identified.

In the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, two TOG/XMAP215 homologues, Alp14 (also called Mtc1) and Dis1, have been identified and shown to be required for both cytoplasmic microtubule organization and mitotic spindle formation (Nabeshima et al., 1995; Garcia et al., 2001; Nakaseko et al., 2001). These two proteins share an essential function in cell division such that deletion of dis1+ results in cold sensitivity, whereas deletion of alp14+ shows temperature-sensitive growth defects (ts), and alp14dis1 double deletions are inviable at any temperature. Phenotypic analysis of double mutants shows that the lethality is ascribable to the failure in forming bipolar spindles, which results in chromosome missegregation (Garcia et al., 2002a). Both proteins localize to interphase microtubules, SPBs, and kinetochores during mitosis (Nabeshima et al., 1995; Garcia et al., 2001; Nakaseko et al., 2001).

In this study, we have identified the coiled-coil protein Alp7, which is likely to be the fission yeast homologue of TACC, as a functional and binding partner of Alp14/TOG. Here, we present novel findings on the regulatory mechanisms, on the cellular localization of these two proteins, and the functional analysis of protein domains of Alp7. We have found that the localization of Alp7 and Alp14 is interdependent but partly hierarchical. Alp14 is completely dislocalized from the SPB and microtubules in alp7 mutants. Conversely Alp14 is required for Alp7 localization to the mitotic spindle, but not to the SPB. Domain analysis shows that the coiled-coil domain of Alp7 binds Alp14, is sufficient for SPB localization and furthermore induces malfunctioning of both spindles and the SPB when overproduced. We discuss mechanisms underlying specific microtubule localization of the Alp7–Alp14 complex and the formation of mitotic bipolar spindles by this complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, Media, and Genetic Methods

Strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The standard methods were followed as described previously (Moreno et al., 1991).

Table 1.

Strain list used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Derivation |

|---|---|---|

| 513 | h-ura4 | Our stock |

| DH738 | h-alp7-738 | Our stock |

| LV4 | h-ura4alp7-738 | Our stock |

| LV24 | h-ura4kanr nmtP3-alp7+ | This study |

| MA062 | h-ura4his7alp14(1-420)-GFP kanr | This study |

| MA063 | h-ura4his7alp14(1-695)-GFP-kanr | This study |

| MS024 | h-ura4alp7+-YFP-kanr | This study |

| MS036 | h-ura4alp7+-YFP-kanrnuf2+-CFP-kanr | This study |

| MS048 | h-ura4alp7+-YFP-kanrcut12+-CFP-kanr | This study |

| MS109 | h-ura4alp7::ura4+ | This study |

| MS134 | h-ura4 his7alp14::kanralp7+-GFP-kanr | This study |

| MS140 | h-ura4 alp7+-YFP-kanralp14+-CFP-kanr | This study |

| MS146 | h-ura4 alp7::ura4+alp14+-GFP-kanr | This study |

| MS157 | h-ura4 alp7::kanr | This study |

| MS163 | h-ura4ade6his7 alp7+-GFP-kanralp14+-13myc-kanr | This study |

| MS167 | h-ura4ade6his7 alp7+-GFP-kanr | This study |

| MS168 | h-ura4ade6his7alp14+-13myc-kanr | This study |

| MS171 | h+ura4his7 alp7+-GFP-kanr dis1::ura4+ | This study |

| MS177 | h-ura4alp7+-GFP-kanr | This study |

| MS187 | h-alp7::ura4+dis1+-GFP-kanr | This study |

| MS210 | h-ura4 alp7::ura4+klp5+-GFP-kanr | This study |

| MS347 | h90ura4nuc2-663 alp7+-GFP-kanr | This study |

| MS363 | h-ura4kanr nmtP3-alp7+ alp14::ura4+ | This study |

| MS398 | h-ura4nda3-311alp7+-GFP-kanrcut12+-CFP-kanr | This study |

| MS427 | h-ura4kanr nmtP3-GFP-alp7+ | This study |

| MS430 | h-ura4kanr nmtP3-GFP-alp7(1-218)-C::ura4+ | This study |

| MS460 | h-ura4kanr nmtP3-GFP-alp7(219-474) | This study |

| MS495 | h-ura4 alp7+-YFP-kanrnuf2+-CFP-kanr alp14::ura4+ | This study |

| MS502 | h-ura4ade6his7 cdc25-22 alp7+-GFP-kanralp14+-13myc-kanr | This study |

| NK067 | h-ura4his7kanr-nmtP81-alp14+-GFP-ura4+ | This study |

| NK080 | h-ura4his7kanr-nmtP81-alp14Δ1-696-GFP-ura4+ | This study |

| NK085 | h-ura4his7kanr-nmtP81-alp14Δ1-430-GFP-ura4+ | This study |

| NK162 | h-ura4 alp14::ura4+ | This study |

All the strains listed in this table contain leu1-32. ura4 used is ura4-D18.

Nucleic Acids Preparation and Manipulation

Enzymes were used as recommended by the suppliers (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). Nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper are in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under the accession number: Q9URY2/AL133498/AB027802.

Construction of Strains Containing N-Terminally or C-Terminally Truncated Alp14-GFP

For construction of N-terminally truncated Alp14 (MA062, MA063) green fluorescent protein (GFP) was integrated at the C terminus of Alp14, and the G418-resistant maker (kanr) was replaced with ura4+. Strains containing N-terminal truncations including full-length Alp14-GFP were then made by integrating kanr-nmtP81 cassette into various positions (+1, +430, and +696). To construct C-terminally truncated Alp14-GFP, the GFP-kanr cassette was integrated at various positions as described above (+421 and +696) by a polymerase chain reaction-based gene targeting method (Bähler et al., 1998).

Construction of Strains Containing GFP-tagged Alp7 at the N Terminus

The kanr-nmtP3-GFP cassette (Bähler et al., 1998) was integrated in front of the initiator methionine to create a strain containing nmtP3-GFP-alp7+FL (MS427). To create a strain containing nmtP3-GFP-alp7+N (1–218, MS430), the ura4+ marker cassette was integrated in the MS427 strain at the alp7 locus corresponding to the 218th amino acid residue. The kanr-nmtP3-GFP cassette was also integrated at the 218th amino acid residue in the alp7 locus to create a strain containing nmtP3-GFP-alp7+C (219–474, MS460).

Time-Lapse Image Analysis

For live analysis, rich medium containing 2% agar was solidified on a glass slide and one drop of the culture of a strain expressing GFP-tagged proteins was placed on top of the agar and sandwiched with a coverslip. Immunofluorescence or live images were viewed with a Zeiss Axioplan equipped with a chilled video charge-coupled device camera (C4742-95; Hamamatsu Photonics, Shizuoka, Japan) and the PC computer containing kinetic image AQM software (Kinetic Imaging Ltd.) and processed by use of Adobe Photoshop (version 6.0) as described previously (Garcia et al., 2001).

Synchronization

A cdc25-22 strain was grown at 26°C and shifted to 36°C for 4 h and 15 min. The cultures were shifted down to 26°C and incubation continued. Samples were taken every 20-min interval for immunoprecipitation and staining with Calcofluor and 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI).

Production of Anti-Alp14 Antibody

Polyclonal rabbit anti-Alp14 antibody was prepared against synthetic peptides corresponding N-terminal peptide (MSQDQEEDYSKLPLESR) or C-terminal peptide (KITEMKQTDQRHQGLIH) and used after affinity purification with the respective peptides. Immunoblots of both affinity-purified peptide antibodies detected specifically a band of around 100 kDa, which disappeared in alp14-deleted cells. Also, a few smaller proteolytic bands were observed.

Indirect Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Cells were fixed with methanol or formaldehyde. Primary antibody (TAT-1 1/50 or anti-Sad1 antibody 1/15) was applied, followed by Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (C2306; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) or anti-mouse IgG (C2128; Sigma-Aldrich), fluorescein-linked sheep antimouse IgG (F0261; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) or Cy5-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (111-175-003; Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME).

Immunochemistry

The following antibodies were used as primary antibodies for immunofluorescence microscopy: mouse monoclonal anti-α-tubulin antibody (TAT-1, provided by Dr. Keith Gull, Oxford University, United Kingdom) and affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal anti-Sad1 antibody (gift from Dr. Mizuki Shimanuki, Kazusa DNA Research Institute, Japan). For immunoblotting, anti-Myc antibody (9E10; Babco, Richmond, CA), anti-GFP antibody (1814 460; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and anti-α-tubulin antibody (TAT-1) were used. For immunoprecipitation, rabbit polyclonal anti-Myc antibody (PRB-150C; Babco) and anti-GFP antibody (8372-2; BD Biosciences Clonetech, Palo Alto, CA) were used as primary antibody. 1 mg of total protein extracts was used. Sepharose-coupled anti-Myc affinity matrix (AFC-150P; Babco) was used to precipitate bound proteins.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Method

Standard methods were followed as described previously (Sato et al., 2002). Budding yeast L40 strain was used as a host. Plasmids used are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Strain and plasmid list for yeast two-hybrid analysis

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| L40 | Matatrp1leu2his3adeLYS2::lexA-HIS3URA3::lexA-lacZ |

| Plasmids | Vectors | Inserted fragments |

|---|---|---|

| pBT-Alp7FL | pBT116 | Alp7: 1-474 |

| pBT-Alp14FL | pBT116 | Alp14: 1-809 |

| pBT-Alp14TOG | pBT116 | Alp14: 1-430 |

| pBT-Alp14Δ430 | pBT116 | Alp14: 431-809 |

| pBT-Alp14Δ696 | pBT116 | Alp14: 697-809 |

| pBT-Alp7ΔC | pBT116 | Alp7: 1-218 |

| pBT-Alp7ΔN | pBT116 | Alp7: 219-474 |

| pGAN6-Alp7FL | pGAD6 | Alp7: 1-474 |

| pGAN6-Alp7ΔN | pGAD6 | Alp7: 219-474 |

| pGAN6-Alp14FL | pGAD6 | Alp14: 1-809 |

RESULTS

Alp7 Is Required for Bipolar Spindle Formation

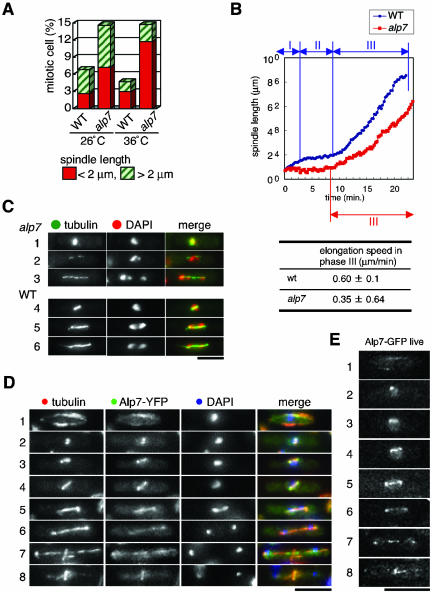

We identified ts alp7-738 as a growth polarity mutant with severe mitotic defects (Radcliffe et al., 1998). Phenotypic analysis of the alp7 mutant showed that even at the permissive temperature (26°C), alp7 mutant cells remained in mitosis longer than wild-type cells (Figure 1A), which is ascribable to activation of the Mad2-dependent spindle assembly checkpoint (Sato et al., 2003). Examination of spindle length in mitotic alp7 cells indicated that mitotic delay occurs at the stages of both early and late mitosis (see red [spindle length <2 μm] and hatched green columns [spindle length >2 μm] in Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Alp7 is a coiled-coil protein that is required for spindle organization and localizes to microtubules. (A) Frequency of mitotic cells. Wild-type and alp7 mutant cells grown at 26 or 36°C (4 h) were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence microscopy with anti-α-tubulin antibody. Frequency of cells with mitotic spindles was counted (at least 200 cells per each sample). (B) Visualization of spindle dynamics in wild-type and alp7 mutants. Strains (wild-type in blue line and alp7 in red line) containing plasmids carrying nmt1-GFP-atb2+ (encoding α2-tubulin) were grown at room temperature (25°C) in the presence of thiamine, and time-lapse live analysis of mitotic spindles was performed. The velocity (μm/min) of spindle elongation at phase 3 is shown with standard deviations. Ten independent samples were observed with live imaging analysis in each strain. (C) Abnormal spindles in alp7 mutants. Representative images displaying mitotic spindles in alp7 mutants (rows 1–3) and wild-type cells (rows 4–6) incubated at 36°C were shown together with DAPI staining. Merged images in which tubulin (green) and DAPI (red) are shown in the right-hand panels. (D) Cellular localization of Alp7. A strain containing Alp7-YFP was grown, fixed with methanol, and processed for immunofluorescence microscopy. Merged images (red for tubulin, green for Alp7-YFP and blue for DAPI) are also shown. Representative images that exhibit Alp7 localization during the cell cycle are presented (1, interphase; 2 and 3, early mitosis; 4, mid-mitosis; 5–7, late mitosis; and 8, postanaphase). (E) Alp7-GFP localization in live cells. A strain containing Alp7-GFP was grown in liquid rich medium at 26°C, and pictures were taken from unfixed live samples. Alp7-GFP images corresponding to stages shown in D (rows 1–8) are shown. Bar, 10 μm.

To show the kinetics of spindle elongation in live cells, we visualized microtubules by introducing nmt1-GFP-atb2+ (encoding α2-tubulin) (Ding et al., 1998), and the behavior of the mitotic spindle was recorded with time lapse live analysis. In wild-type cells, mitotic stages were divided into three phases based on spindle length: phase 1 (prophase), phase 2 (a period with constant spindle length, equivalent to prometaphase to anaphase A), and phase 3 (anaphase B) (see top blue line in Figure 1B) (Nabeshima et al., 1998). Unlike wild-type cells, on the other hand, alp7 mutants (bottom red line) displayed characteristic defects in all three phases, such that there were no periods corresponding to phases 1 and 2. Instead, a stage in which cells contain very short spindles (<1 μm), which looked like single dots by immunofluorescence microscopy, continued for >8 min. After this pause, spindles elongated during phase 3 with a slower velocity (0.35 μm/min, 40% reduction). The stage with dotted spindles before onset of phase 3 could be ascribable to the action of the Mad2-dependent spindle assembly checkpoint (Sato et al., 2003). A slower rate of spindle elongation during phase 3 might also contribute to the delay. This result shows that Alp7 regulates mitotic progression and is required for proper spindle elongation during anaphase B at the permissive temperature.

We noticed that the proportion of mitotic cells was not noticeably increased under restrictive conditions (36°C; Figure 1A). This indicates that the phenotype of the alp7 mutant is not simply due to prolonged mitotic arrest at 36°C, but instead Alp7 may play an essential role in mitosis at the higher temperature. To obtain an insight into the essential role of Alp7 at the high temperature, we next examined defective phenotypes of alp7 upon temperature shift up to 36°C. The most obvious phenotypes are defective mitotic spindles and severe chromosome missegregation (Figure 1C). At the very early stage of mitosis, when bipolar spindles start to form, we observed a densely stained dot of microtubules (row 1), which corresponds to prolonged mitotic phase seen at 26°C. In subsequent stages, mitotic spindles seemed to be unstable, with virtually no spindles being sufficiently robust to survive fixation protocols for immunofluorescence microscopy formed in alp7 mutants (rows 2 and 3, note chromosome missegregation in the cell of row 3, and see Supplementary Figure S1 for quantification of spindle intensity). These results show that Alp7 plays an essential role in bipolar spindle formation and equal chromosome segregation at 36°C.

Alp7 Localizes to the Microtubule

Alp7 contains the coiled-coil domain in the C-terminal region and is nonessential; complete deletion of the alp7+ open reading frame is viable and shows a ts phenotype similar to alp7-738 mutants (Sato et al., 2003). To examine the subcellular localization of Alp7, it was tagged with GFP or yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) at the C terminus, such that the tagged protein was produced under the native promoter. This C-terminal tagging did not interfere with Alp7 function as strains containing Alp7-GFP or Alp7-YFP grew normally at all temperatures tested, including 36°C and did not show an increase in mitotic cells (Supplementary Figure S2). The Alp7-YFP strain was grown exponentially, fixed with methanol, and immunofluorescence microscopy was performed with anti-tubulin antibody and DAPI staining. As shown in Figure 1D, Alp7-YFP colocalized to microtubules, almost completely, during both interphase (rows 1 and 8) and mitosis (rows 2–7).

To examine Alp7 localization in live cells, signals of Alp7-GFP were examined in growing cultures without prior fixation. As shown in Figure 1E, Alp7 localization images are very similar to those in fixed cells. One difference, which should be noted, however, was the pattern of Alp7 localization along the spindle. Whereas fixed samples tended to display staining along the whole spindle (Figure 1D, rows 5–7), live cells showed rather discrete patterns on long spindles (compare corresponding rows 5–7 in Figure 1E). In addition, in late anaphase, Alp7-GFP seemed to localize to the spindle midzones and the two SPBs (row 7). In summary, Alp7 localizes to interphase microtubules and mitotic spindles in a discrete pattern.

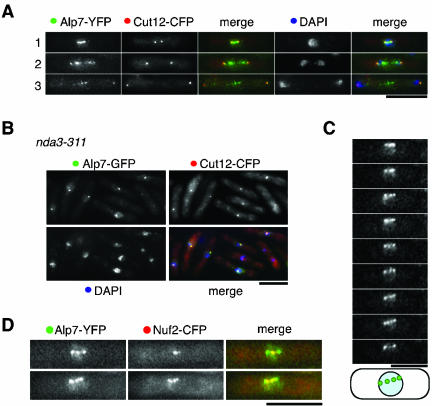

During Mitosis Alp7 Is Enriched in Both the SPB and the Kinetochore

Alp7 localization on mitotic spindles was addressed in more detail by using established localization markers. First, whether Alp7 localized to SPBs was examined using Alp7-YFP and Cut12-CFP, an authentic component of the SPB (Bridge et al., 1998). Because we learned that fixation with formaldehyde retained intact Alp7 localization as seen in live cells (see below), we used formaldehyde for fixation in the subsequent experiments. Figure 2A shows that Alp7 colocalized with Cut12 during mitosis. Note that localization patterns of Alp7-YFP are very similar, if not identical, to those from unfixed live cells (Figure 1E). Alp7 localization to SPB during mitosis was confirmed in an nda3-311 strain, a cold-sensitive β-tubulin mutant (Hiraoka et al., 1984). On temperature shift down to 20°C, Alp7-YFP localized only to the SPB (Figure 2B). This also indicates that Alp7 does not require a microtubule cytoskeleton to localize to the SPB. It is of note that in contrast to mitotic cells, in most of the interphase cells, Alp7 localized along cytoplasmic microtubules that are dissociated from the SPB (Figure 1D, row 1).

Figure 2.

Mitotic localization of Alp7 to the SPB and kinetochore periphery. (A) Colocalization between Alp7-YFP and Cut12-CFP. A doubly tagged strain was fixed with formaldehyde and signals were observed under fluorescence microscopy. Merged images (green for Alp7-YFP, red for Cut12-CFP and blue for DAPI) are also shown. (B) Localization of Alp7 to the mitotic SPB. An nda3-311 strain containing Alp7-GFP and Cut12-CFP was incubated at 20°C for 6 h and fixed with formaldehyde. (C) Time-lapse live analysis of mitotic localization of Alp7-GFP. Alp7 localization during mid-mitosis is depicted in the bottom row. (D) Overlapping localization between Alp7 and a kinetochore marker in mitotic cells. A strain containing Alp7-YFP and Nuf2-CFP was grown, fixed with formaldehyde, and mitotic cells were observed with YFP (green) and CFP (red). Bar, 10 μm.

Previous data showed that during mitosis, in addition to the SPBs, Alp7 existed as discrete patterns on mitotic spindles (e.g., Figures 1E, row 4, and 2A, row 1). This suggested that Alp7 localization on mitotic spindles is dynamic. To visualize the mitotic movement of Alp7, live time-lapse analysis was performed. As shown in Figure 2C, Alp7-GFP displayed a dotted pattern, where the number of dots varied from three to five, of which two peripheral dots must correspond to the SPBs (Figure 2A). Notably, the central Alp7-GFP dots moved back and forth between the two SPBs, reminiscent of kinetochore movement before onset of anaphase A (Garcia et al., 2001, 2002b; Nakaseko et al., 2001). The notion of Alp7 localization to the kinetochore was further substantiated in a strain containing Alp7-YFP and Nuf2-CFP, an established kinetochore marker (Nabetani et al., 2001). As shown in Figure 2D, the central dots of Alp7-YFP colocalized with Nuf2-CFP. This suggested that Alp7 localizes to mitotic spindles, from where it can associate with the mitotic kinetochores. Together, Alp7 is a microtubule-associated protein, which localizes to the SPB and kinetochore periphery in a mitosis-specific manner.

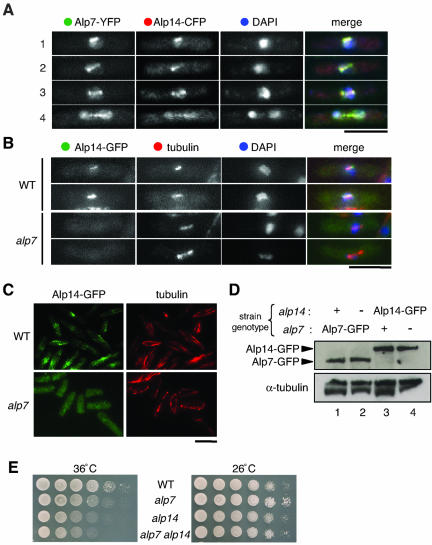

Alp7 and Alp14-TOG Colocalize to Microtubules

The cellular localization of Alp7 described above seemed very similar to Alp14, one of two fission yeast homologues of the Dis1/TOG MAP family (Garcia et al., 2001; Nakaseko et al., 2001). To examine the localization of both proteins, a strain containing Alp7-YFP and Alp14-CFP was constructed and localization of individual proteins was visualized in a single cell. From this it was evident that Alp7 and Alp14 colocalize during mitosis (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Alp7 colocalizes with Alp14 and is required for the specific localization of Alp14 to the microtubules. (A) Colocalization of Alp7 and Alp14. A strain containing Alp7-YFP and Alp14-CFP was grown, fixed, and observed with YFP, cyan fluorescent protein (CFP), and DAPI staining. Representative pictures of mitotic cells are shown (1; early mitosis; 2 and 3, mid-mitosis; and 4, late mitosis). Merged images for Alp7-YFP (green), Alp14-CFP (red), and DAPI (blue) are shown in the right-hand panels. (B and C) Requirement of Alp7 for Alp14 localization to the microtubules. Wild-type (top rows) or alp7-deleted cells (bottom rows) containing Alp14-GFP was cultured at 26°C, fixed, and processed for immunofluorescence microscopy. In the far-right panels in B, merged images (Alp14-GFP in green, tubulin in red, and DAPI in blue) are shown. Bar, 10 μm. (D) Protein levels of Alp7 and Alp14. Immunoblot against total cell extracts prepared from strains containing Alp7-GFP (lane 1), Alp7-GFP in alp14 mutants (lane 2), Alp14-GFP (lane 3), and Alp14-GFP in alp7 mutants (lane 4) was performed with anti-GFP and anti-α-tubulin antibodies. (E) Nonadditive ts phenotype of alp7alp14 double mutants. Wild-type (top row), alp7-deleted (second), alp14-deleted (third), or alp7alp14-deleted cells (bottom) were spotted on rich plates (106 cells in the far-left spots for each plate and then diluted 10-fold in each subsequent spot rightwards) at 36°C (left) or 26°C (right) and incubated for 3 d.

Alp7 Is Required for Specific Alp14 Localization

Given the colocalization of Alp7 and Alp14, we next addressed the localization dependency of one protein upon the other. For this purpose, strains containing Alp14-GFP in alp7 mutants and conversely Alp7-GFP in alp14 mutants were constructed. We found that in the absence of Alp7, Alp14 was no longer capable of localizing to the mitotic spindle or the SPB (Figure 3B). Alp7 is also required for Alp14 localization to interphase microtubules, i.e., in alp7 mutants during any cell cycle stage Alp14-GFP was observed as a homogenous cytoplasmic signal (Figure 3C). Lack of specific localization of Alp14 to microtubules in the absence of Alp7 was not ascribable to down-regulation of Alp14 protein levels, because comparable amounts of Alp14-GFP were detected on an immunoblot with total cell extracts prepared from wild-type and alp7 mutant cells (Figure 3D, lanes 3 and 4).

As reported previously, alp14 deletion mutants display, like alp7 deletions, ts lethality (Garcia et al., 2001; Nakaseko et al., 2001). If the ts phenotype of alp7 resulted mainly, if not entirely, from delocalization and malfunction of Alp14, double mutants between these two deletions would not show synthetic phenotypes. To address this question, we constructed the alp7alp14 double mutant and its growth properties were examined. As shown in Figure 3E, the ts phenotype of alp14 and alp7alp14 mutants was almost indistinguishable, although alp7alp14 double mutants seemed to show slightly more returned growth at 36°C. Together, these results suggest that Alp7 is a factor required for Alp14 localization to both interphase microtubules and mitotic spindles.

In the Absence of Alp14, Alp7 Localizes Only to the SPB, but Not to the Spindle or Kinetochore Vicinity

Given the requirement of Alp7 for Alp14 localization, we then sought to examine their interdependency and specificity. In alp14 mutants, Alp7-GFP localized to the SPBs at both 26°C (Figure 4A, left) and 36°C (right), indicating that the relationship is not fully interdependent. However, we noticed that even at 26°C Alp7-GFP localized only to the SPBs, and no localization was observed to either spindles or central dots. To clarify this point, Alp7-GFP and spindles were costained. Whereas in wild-type cells Alp7 localized to the kinetochore vicinity as well as the SPBs (Figure 4B, and see also Figure 2, C and D), Alp7 localized only to two peripheral dots (arrowheads) in alp14 mutants, despite these cells containing mitotic spindles. To confirm that these two dots correspond to the SPB, not the kinetochores, costaining was performed with Nuf2-CFP and anti-Sad1 antibody (an SPB marker) (Hagan and Yanagida, 1995). As shown in Figure 4C, two Alp7-GFP dots precisely colocalized to those of Sad1 dots, and Nuf2-CFP was found in the middle of these two dots, demonstrating that in the absence of Alp14, Alp7 only localizes to the SPB, but failed to associate with spindles. This result indicates that Alp14 is not required for targeting of Alp7 to the SPBs; nonetheless, it plays an essential role in Alp7 localization to the kinetochore vicinity along mitotic spindles.

Figure 4.

Alp7 localizes to only the SPBs, but not the spindles, in the absence of Alp14, and the requirement of Alp7 for Alp14 localization is specific. (A) Alp7 localization to the SPB in alp14 mutants. A strain containing Alp7-GFP in alp14 mutants was constructed, and GFP signals were observed at 26°C (left) or at 36°C (right). Merged images (green for Alp7-GFP and red for DAPI) are also shown. (B and C) Lack of spindle localization of Alp7 in alp14 mutants. Wild-type and alp14 mutant cells containing Alp7-GFP (B) or Alp14-GFP and Nuf2-CFP (C) were grown at 26°C, fixed, and processed for immunofluorescence microscopy. Merged images are shown with green for Alp7-GFP, red for tubulin, and blue for DAPI (B) or blue for anti-Sad1 (C). Alp7 localization to the two SPBs was marked with arrowheads in B. (D) Dis1 localization in the absence of Alp7. Mitotic cells (rows 1 and 2) and interphase cell (row 3) are shown. Merged images are shown with green in Dis1-GFP and red in DAPI. (E) Alp7 localization in the absence of Dis1. dis1 mutants containing Alp7-GFP were grown at 32°C. Alp7-GFP localization in mitotic cells is shown. Merged images are shown as in A. (F) Klp5 localization in alp7 mutants. Merged images are shown with green in Klp5-GFP, red in tubulin, and blue in DAPI. Bar, 10 μm.

Dis1 has been shown to be a structural and functional homologue of Alp14 (Garcia et al., 2001; Nakaseko et al., 2001). Next, we asked whether Dis1 localization to microtubules needs Alp7 function. Intriguingly, this was not the case. As shown in Figure 4D, in an alp7 mutant, as in wild-type, Dis1-GFP showed punctate patterns along the mitotic spindle (rows 1 and 2) and normal localization to interphase microtubules (row 3) (Nakaseko et al., 2001). Alp7 localization in the dis1 mutant was then examined. As shown in Figure 4E, Alp7 localized to mitotic spindles as discrete patterns as in wild-type cells. This indicated that Dis1 is not involved in Alp7 localization. Thus, despite Alp14 and Dis1 being thought of as homologues, their in vivo associations to the microtubule are regulated in distinct manners.

Microtubule-destabilizing proteins Klp5 and Klp6, homologues of metazoan Kin I (Desai et al., 1999; Garcia et al., 2002b; Walczak et al., 2002) also localize to the mitotic kinetochore. We have recently shown that these two proteins share an essential function with Alp14 and Dis1 and are involved in the attachment of the kinetochore to the spindle (Garcia et al., 2002a). To examine the specificity of the dependent relationship between Alp7 and Alp14, we observed Klp5-GFP in alp7 mutants. As shown in Figure 4F, unlike Alp14, Klp5 was able to localize to mitotic spindles as dots. These results indicate that the requirement of Alp7 for Alp14 localization to the microtubule is specific and that localization of these two proteins is only partially interdependent.

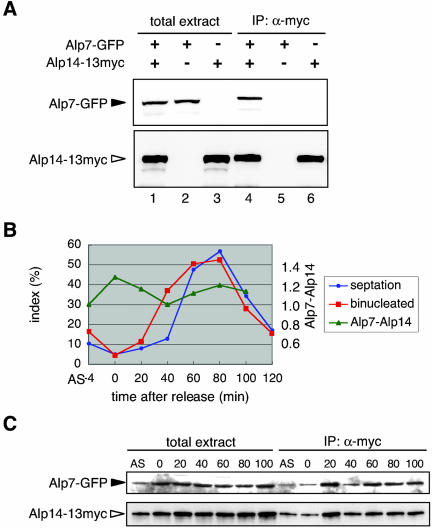

Alp7 and Alp14 Form a Complex That Does Not Fluctuate during the Cell Cycle

As a first step to address how Alp7 may regulate the specific in vivo localization of Alp14, a physical interaction between these two proteins was examined. Immunoprecipitation was performed using a doubly tagged strain that contained Alp7-GFP and Alp14–13myc each produced from their native promoters. It was found that Alp7-GFP specifically coprecipitated with Alp14-13myc (Figure 5A, lane 4).

Figure 5.

Physical interaction between Alp7 and Alp14 during the cell cycle. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation between Alp7 and Alp14. Total cell extracts were prepared from exponentially growing strains containing Alp7-GFP and Alp14–13myc (lane 1 and 4), Alp7-GFP (lanes 2 and 5), or Alp14–13myc (lanes 3 and 6), and immunoprecipitation was performed. Immunoprecipitates were then blotted with mouse monoclonal anti-GFP (top lanes 4–6) or anti-myc antibody (bottom lanes 4–6). Cell extracts used for immunoprecipitation were also run (50 μg, lanes 1–3). (B) A cdc25-22 strain containing Alp7-GFP and Alp14–13myc was shifted to 36°C for 4 h and 15 min (0 min) and then shifted down to 26°C. Samples were taken every 20-min interval for immunoprecipitation and staining with Calcofluor and DAPI. The percentage of septated cells (blue circles) and binucleated cells (red squares) is plotted at each time point. Also shown is quantification of Alp7–Alp14 complex levels (triangles in green). Image J (National Institutes of Health) was used to compare the level of the Alp7–Alp14 complex at each time point. The ratio of precipitated Alp7 and Alp14 was normalized. (C) Coimmunoprecipitation of Alp7 and Alp14 upon cdc25-22 arrest-release. AS means asynchronous culture at 26°C before shift up.

We next addressed whether the complex formation between these two proteins is cell-cycle regulated. For this purpose, synchronous culture was prepared using temperature-sensitive cdc25-22 arrest-release systems and immunoprecipitation was performed at several time points before and after release (Figure 5, B and C). It seemed that the amount of the Alp7–Alp14 complex does not fluctuate noticeably during the cell cycle. These results indicate that Alp7 targets Alp14 to the microtubule by directly binding to it, and binding is not cell-cycle regulated.

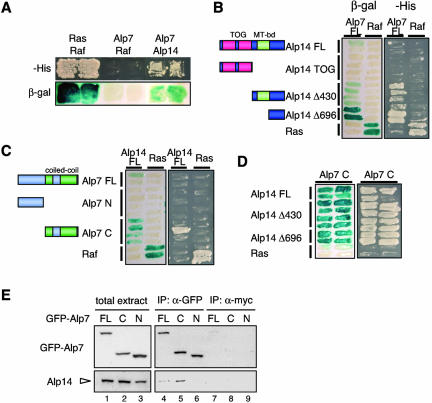

The Coiled-Coil Domain of Alp7 Interacts with the C-Terminal non-TOG Region of Alp14

We next sought to dissect the regions of each protein that are required for binding by using yeast two-hybrid assay. First, an interaction between the two individual full-length proteins was confirmed (Figure 6A), although, compared with a positive control (Ras-Raf), the degree of interaction seemed weaker. Next, either N-terminal or C-terminal fragments of these two proteins were expressed, and their interaction was examined. Assays between full-length Alp7 and subclones of Alp14 showed that N-terminally deleted Alp14, leaving 113 amino acid residues (Alp14 Δ696), is sufficient for an interaction with Alp7 (Figure 6B). Intriguingly this C-terminal region (697–809) is distinct from the domain (559–709, shown in green box in Figure 6B) that is required for microtubule binding in vitro (Nakaseko et al., 2001). This indicates that the C-terminal non-TOG region of Alp14 could be divided into two functionally distinct domains, one (559–709) possesses an in vitro microtubule binding activity, whereas the other (697–809) interacts with Alp7.

Figure 6.

Identification of interacting domains of Alp7 and Alp14. (A) Two-hybrid assay. Budding yeast transformants expressing the indicated gene products were streaked on minimal medium lacking histidine (-His) or plates containing X-Gal (β-gal). As a positive control, plasmids expressing Ras and Raf were used. (B) Two-hybrid interaction between full-length Alp7 and various region of Alp14. Schematically shown (left) are regions subcloned (FL, full-length). Full-length Alp7 was used as bait. (C) Interaction between full-length Alp14 and N-terminal or C-terminal half of Alp7. (D) Interaction between subregions of Alp7 and Alp14. (E) Interaction between Alp14 and the C-terminal Alp7 in fission yeast cells. Immunoprecipitation was performed in three different strains, in which full-length (lanes 1, 4, and 7), the C-terminal region (219–474, lanes 2, 5, and 8), and the N-terminal region of Alp7 (1–218, lanes 3, 6, and 9) were expressed with GFP. Cells were grown in rich medium and immunoprecipitation was performed with anti-GFP (lanes 4–6) or anti-myc antibody (lanes 7–9), followed by immunoblotting with anti-GFP (top) or anti-Alp14 antibody (bottom).

Two-hybrid analyses between full-length Alp14 and subclones of Alp7 indicate that the C-terminal coiled-coil region of Alp7 plays a major role in binding to Alp14 (Figure 6C). The N-terminal region alone did not interact with Alp14. We then examined the binding between individual subclones of each protein. As shown in Figure 6D, the C-terminal coiled-coil region of Alp7 (Alp7C) was capable of interacting to a similar degree with three types of the Alp14 protein, full-length and N-terminally deleted (Δ430 and Δ696). Together, we concluded that each C-terminal region of Alp7 and Alp14 interacts with each other.

We next addressed the domain of Alp7 that is responsible for an interaction with Alp14 in fission yeast cells. For this purpose, the nmtP3-GFP cassette (Bähler et al., 1998) was integrated into the genome to express three types of Alp7 proteins, full length (1–474), the N-terminal region (1–218) and the C-terminal region (219–474) (Figure 8A). All three types of Alp7 proteins were expressed under repressed conditions (lanes 1–3 in Figure 6E). Immunoprecipitation was then performed with anti-GFP antibody, followed by immunoblotting with anti-Alp14 antibody (for specificity of this antibody, see Supplementary Figure S3). Alp14 interacted with both the full-length and the C-terminal region of Alp7 (lanes 4 and 5), but not with the N-terminal region (lane 6). Interaction was specific, because nonrelated anti-myc antibody did not precipitate either Alp7 or Alp14 (lanes 7–9). Thus, consistent with two-hybrid analysis, the C-terminal coiled-coil region of Alp7 is responsible for forming a complex with Alp14 in fission yeast cells.

Figure 8.

Defects in microtubule organization by induced overproduction of Alp7. (A) Schematic representation of strains constructed to dissect functional domains of Alp7. The nmtP3-GFP cassette (Bähler et al., 1998) was integrated in the indicated position of the alp7 locus. (B) Expression of GFP-Alp7 proteins. Strains shown in A (FL, Alp7FL; C, Alp7C; and N, Alp7N) were grown in the presence (+) or absence (-) of thiamine and cell extracts were prepared. Immunoblotting was performed with anti-GFP antibody. Anti-α-tubulin antibody was used as a loading control. (C) Localization of the N-terminal and C-terminal Alp7. Strains containing GFP-tagged Alp7 (full-length, the C-terminal or N-terminal region) were grown in the presence of thiamine (repressed) and GFP signals were observed in individual cells. (D) Toxicity of Alp7 overproduction. Strains containing individual GFP-tagged Alp7 constructs were grown and spotted on rich plates (left) or minimal medium lacking thiamine (right, 106 cells in the far-left spots for each plate and then diluted 10-fold in each subsequent spots rightwards) at 27°C and incubated for 4 d. (E) Structure and organization of microtubules and the SPB in Alp7 overproducing cells. Cells expressing nmtP3-GFP-alp7+FL (rows 1–4) or nmtP3-GFP-alp7C (rows 5 and 6), or alp14-deleted cells containing nmtP3-GFP-alp7+FL (rows 7 and 8) were grown in the absence of thiamine at 27°C for 18 h, and immunofluorescence microscopy was performed with anti-tubulin and anti-Sad1 antibodies. Merged images are shown in the right-hand side (anti-Sad1, green; anti-tubulin, red; and DAPI, blue). Bar, 10 μm.

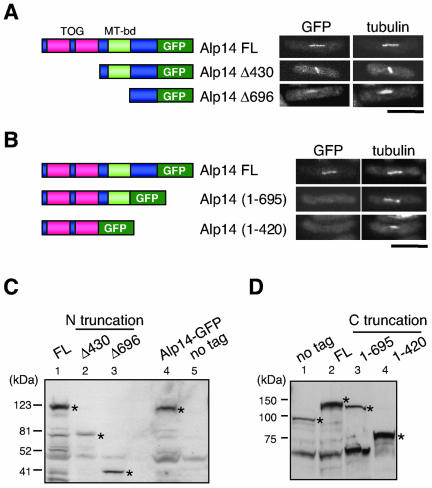

The Short C-Terminal Region of Alp14 Is Necessary and Sufficient to Localize to Microtubules In Vivo

To determine the region that is necessary for Alp14 to localize to microtubules in the cell, a series of N-terminal and C-terminal deletion constructs were expressed with GFP in fission yeast, and their localization pattern was examined. In addition to full-length Alp14, two N-terminally truncated versions of Alp14-GFP, which included those used in the two-hybrid assay, were constructed (Δ430 and Δ696, the left-hand side in Figure 7A). Fluorescence microscopy showed that Alp14 Δ430 was capable of localizing to mitotic spindles as strong as full-length Alp14 (the top and second rows). Intriguingly a further deleted construct Alp14 Δ696 clearly still localized to mitotic spindles (the third row), although signals were decreased compared with other two constructs.

Figure 7.

Determination of the minimal region of Alp14 required for in vivo localization to the spindle. (A) N-terminal truncation. Various subclones (depicted in the left-hand side) are constructed with C-terminally tagged GFP (integrated in the chromosome with nmt81 promoter) were tested for mitotic spindles in vivo. GFP signals were observed under derepressed conditions. Bar, 10 μm. (B) C-terminal truncation. GFP was integrated at various positions (left) and GFP signals were observed (right). (C and D) Immunoblotting with anti-GFP (C) or anti-Alp14 antibody (D) against cell extracts used in A (C, N-terminal truncation) and B (D, C-terminal truncation). Bands corresponding to Alp14 or its derivatives in each construct are marked with asterisks.

Deletions in the C-terminal regions with GFP tagging were also constructed (1–695, and 1–420, the left-hand side in Figure 7B). None of these C-terminally deleted proteins localized to SPBs or spindles. Expression of truncated proteins shown above was confirmed by immunoblotting as shown in Figure 7C (N-terminal truncation) and Figure 7D (C-terminal truncation). Thus, the C-terminal region of Alp14 that is responsible for Alp7 binding (Figure 6B) is necessary and sufficient for microtubule localization in vivo.

The C-Terminal Coiled-Coil Domain of Alp7 Is Responsible for Microtubule Localization

We sought to dissect Alp7 regions that are necessary for its in vivo localization and function. As described before, we created strains in which full-length, the N-terminal, or the C-terminal region of Alp7 was tagged with GFP and expressed under the thiamine-repressible nmtP3 promoter (GFP-Alp7FL, GFP-Alp7N, and GFP-Alp7C, respectively; Figure 8A). Immunoblotting with anti-GFP antibody under repressed and derepressed conditions showed that each type of protein was expressed as expected (Figure 8B). Using these strains, first the cellular localization of each GFP-Alp7 protein was examined under repressed conditions. It was clear that both full-length and C-terminal Alp7 proteins were capable of localizing to mitotic spindles (Figure 8C, top and middle), whereas, compared with full-length GFP-Alp7, N-terminally deleted GFP-Alp7C localized to spindles more weakly. In contrast, C-terminally deleted GFP-Alp7N failed to localize to microtubules (Figure 8C, bottom). This result indicated that the C-terminal coiled-coil domain of Alp7 plays a pivotal role in Alp7 function, because it is responsible for not only the interaction with Alp14 (Figure 6E) but also in vivo microtubule localization of Alp7.

Overproducing Full-Length or the Coiled-Coil Domain of Alp7 Results in Abnormal Microtubule Organization and Inhibition of SPB Separation

We next examined the phenotypic consequence of Alp7 overproduction by using nmtP3-GFP-alp7+ strains under derepressed conditions. As shown in Figure 8D, both Alp7FL and Alp7C were toxic and inhibited colony formation. Immunofluorescence microscopy showed that toxic Alp7FL and Alp7C induced predominantly two abnormalities in microtubule structures. One occurred during mitosis, which resulted in the appearance of V-shaped spindles (Figure 8E, rows 1, 2, and 5). These defective spindles are characteristic phenotypes that result from defective SPB function and are often associated with a failure in SPB separation (Hagan and Yanagida, 1990, 1992). In fact, Alp7-overproduing cells displaying V-shaped spindles were also defective in SPB separation (see anti-Sad1 staining in Figure 8E).

The second phenotype was observed in interphase cells, which exhibited apparent stabilization of cytoplasmic microtubules. As shown in Figure 8E (rows 3, 4, and 6), instead of normal cytoplasmic arrays consisting of multiple shorter microtubules (Hagan, 1998), a single long curved microtubule was seen. In addition, it is of note that the position of the nucleus in these cells was not normal, the nucleus was displaced from the center of the cell axis (rows 4 and 6). The nuclear displacement is reminiscent of defective microtubule/SPB function (Radcliffe et al., 1998; Vardy and Toda, 2000).

It is important to note that these abnormal mitotic and interphase microtubule phenotypes are induced by Alp7 overproduction even in the absence of Alp14 (Figure 8E, rows 7 and 8). Thus, at least under conditions of overproduction, Alp7, in particular its C-terminal coiled-coil domain, is capable of inducing abnormal microtubules and interfering with SPB function independent of Alp14. This implies that Alp7 plays a role in SPB organization during both interphase and mitosis that does not require Alp14-TOG.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have identified fission yeast Alp7 as a partner of Alp14-TOG. Alp7 and Alp14 form a complex and colocalize to the SPB and mitotic spindles. The cellular localization of Alp14 is fully dependent upon Alp7. Conversely, in the absence of Alp14, Alp7 localizes to the SPBs, but not mitotic spindles. Therefore, localization of Alp7 and Alp14 is mutually dependent and partly hierarchical. The functional relationship between Alp14/TOG and Alp7 described in this study points toward a close similarity between Alp7 and animal TACC. This prompted us to conduct careful comparison of amino acid sequence between Alp7 and TACC. Although Alp7 did not show any hits to human TACC by BLAST search, when amino acid comparison is made with all the TACC members, including recently reported C. elegans TAC-1, which is much more distantly related to conventional TACCs, Alp7 indeed shows a significant homology to the TACC family. The similarity is restricted to the C-terminal coiled-coil “TACC” domain (Supplementary Figure S4). These findings indicate that Alp7 is a fission yeast homologue of animal TACC.

Results shown here have highlighted both conservation and divergence of TACC function among species. A complex formation between TOG and TACC is conserved in all cases. Importantly, in worm, it is the C-terminal region of ZYG-9 that binds TAC-1 (Bellanger and Gönczy, 2003), which is consistent with the results presented for Alp14 binding to Alp7 in this study. Also the requirement of TACC for TOG localization to the centrosome/SPB and microtubules is in common in all organisms. However, molecular mechanisms as to how TACC regulates TOG localization seem divergent. Whereas in fly and human TACC is responsible for TOG localization by acting as a targeting molecule (Cullen and Ohkura, 2001; Lee et al., 2001; Gergely et al., 2003), in worm it seems that protein stability of ZYG-9 is ensured by binding to TAC-1, in TAC-1–depleted cells, ZYG-9 levels are substantially decreased (Bellanger and Gönczy, 2003; Srayko et al., 2003). This relationship is mutual because TAC-1 levels are also reduced in ZYG-9–depleted cells. As shown here, in fission yeast protein levels of Alp7 or Alp14 are not altered in alp14 or alp7 mutants, respectively, and Alp7 plays a role in targeting Alp14 to the SPB.

In addition to parallelisms, our analysis sheds a novel light on the regulation by Alp14/TOG toward Alp7/TACC. We show that Alp14 is required for Alp7 localization to the mitotic spindle. It is currently not known whether D-TACC localizes properly in msps mutants. Although human TACC3 seems to localize normally to the spindles under ch-TOG–depleted conditions (Gergely et al., 2003), because humans contain additional TACC1 and 2, it would be of particular interest to examine the localization of these proteins in ch-TOG–depleted cells. TACC3-depleted cells display relatively normal appearance of bipolar spindles (Gergely et al., 2003); however, a functional redundancy between TACC members needs to be considered. It should be pointed out that TACC3-depleted cells show a mitotic delay (Gergely et al., 2003), which, we conceive, might be attributable to activation of the Mad2-mediated spindle checkpoint like alp7 mutants (Sato et al., 2003). Overall, we feel that it would be of significance at this stage to emphasize the mutual dependence of localization between Alp7 and Alp14 as a novel finding, and with regards to a functional conservation we should await further analysis in vertebrate systems.

Another novelty in this study is the domain analysis of the Alp7 protein. We have shown that the C-terminal coiled-coil domain is the region, which is sufficient to both bind Alp14 and localize to the SPB and microtubules. Furthermore, it is the region responsible for induction of abnormal microtubule morphology upon overproduction. Human, fly, and fission yeast TACC members contain the N-terminal non-coiled-coil region, which does not show any conservation in amino acid sequence. Because worm TAC-1 is shorter and consists of only coiled-coil domain (Bellanger and Gönczy, 2003; Le Bot et al., 2003; Srayko et al., 2003), it is possible that the N-terminal region is simply an appurtenance. We have been performing further functional analysis of the N- and C-terminal domains of Alp7. A strain that lacks the C-terminal region of Alp7 displays a ts phenotype similar to the complete deletion of Alp7, further indicating the importance of the coiled-coil domain of Alp7 (Sato and Toda, unpublished data).

In budding yeast, Spc72 interacts with Stu2 and regulates Stu2 function (Souès and Adams, 1998; Usui et al., 2003). Despite this functionality, the amino acid sequence of Spc72 does not show any homology to Alp7 or TACC/TAC-1. Spc72 localizes to the cytoplasmic side of the SPB and is involved in the formation of astral microtubules (Souès and Adams, 1998; Pereira et al., 1999; Usui et al., 2003), whereas Stu2 regulates the dynamics of mitotic spindles in addition to that of astral microtubules (Severin et al., 2001; Pearson et al., 2003; van Breugel et al., 2003). Furthermore, Stu2 still localizes properly to the SPB and microtubules in spc72 mutants, in which the N-terminal Stu2-binding domain is deleted (Usui et al., 2003). This suggests that budding yeast might contain additional factor(s) required for Stu2 localization and function. Because the budding yeast protein most homologous to Alp7 is Slk19 (Sato et al., 2003), which is involved in mitotic spindle function (Zeng et al., 1999), it would be of interest to address a genetic and physical interaction between Slk19 and Stu2.

Given the mutual dependency and partial hierarchy of the cellular localization, it is likely that Alp7 is a targeting factor for Alp14 to the SPB. This leads us to propose a pathway, consisting of two distinct steps, resulting in the specific localization of the Alp7–Alp14 complex (Figure 9). One step is the microtubule-independent targeting of this complex to the SPB during mitosis. Alp7 plays a guiding role in this process. The other step is the Alp14-dependent localization of this complex to the microtubule and kinetochore vicinity. This process may be coupled to microtubule polymerization and stabilization, which Alp14 predominantly regulates. An alternative model is also conceivable. For example, the Alp7–Alp14 complex may be first targeted to the mitotic spindle. Then, these two proteins are transported toward the SPB, possibly by minus end-directed motors. This model is similar to that proposed for the Msps/D-TACC complex in the female meiosis in fly (Cullen and Ohkura, 2001). Because Alp14 completely delocalizes from microtubules in the absence of Alp7, the first model appears preferable; however, the second scenario is still possible. It would be important to record the movement of this complex on the SPB and the spindle in live cells.

Figure 9.

Proposed manner of Alp7-TAC and Alp14-TOG localization to the SPB and microtubules and how this complex regulates microtubule organization. A model depicts a functional dependency between Alp7 and Alp14. Alp7 and Alp14 form a complex, by which Alp7 targets this complex to the SPB. Once localizing to the SPB, Alp14 is responsible for localizing to mitotic spindles and kinetochores. The short C-terminal domain of Alp14 (C in yellow) and the coiled-coil region of Alp7 (C in green) bind each other and are responsible for the specific localization.

We show that the requirement of Alp7 for Alp14-TOG localization is specific. Unlike Alp14, Dis1-TOG localization does not require Alp7. This difference is explained by the fact that the extreme C-terminal region of Dis1 does not show any similarity to the corresponding region of Alp14 (696–809), the Alp7-binding domain. Whether Dis1 needs an Alp7-like protein to target it to the microtubule remains to be determined. However, it should be noted that, unlike Alp14, kinetochore localization of Dis1 is still observed in the absence of microtubules (Nakaseko et al., 2001).

Genetic analysis suggests that a major role of Alp7 is mediated through Alp14. Is this the full story for Alp7 function? We envisage that it might not be for the following reasons. First, alp7alp14 double mutants grew more slowly at 36°C than a single alp14 mutant, although the difference was rather subtle. Second, overproduction of Alp7 resulted in V-shaped spindles during mitosis and long, curved microtubules during interphase. V-shaped spindles are characteristic of mutations in SPB components, such as Cut11, Cut12, and Sad1 (Hagan and Yanagida, 1990, 1995; Bridge et al., 1998; West et al., 1998), or BimC-related kinesin motor Cut7 (Hagan and Yanagida, 1992). It is believed that the appearance of the V-shaped spindles is primarily ascribable to the failure in successful SPB separation. Although Alp7 overproduction could create the nonphysiological artificial situation, it is possible that when overproduced Alp7, interferes with SPB structural organization, resulting in prevention of SPB separation at mitosis. The appearance of curved cytoplasmic microtubules suggests that the excessive amount of Alp7 results in hyperstabilization of interphase microtubules that associate with the SPB. Importantly these abnormalities occur in the absence of Alp14, indicating that Alp7 has interacting partner(s) besides Alp14 at the SPB. It is tempting to speculate that Alp7 and Alp14 are required for in vivo microtubule dynamics in a stage-specific manner, in which the Alp7–Alp14 complex may regulate microtubule dynamics at both minus and plus ends, thereby playing a harmonious role in the establishment of mitotic bipolar spindles and interphase microtubules.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data for this article are available.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Tony Carr, Julie Promisel Cooper, Da-Qiao Ding, Keith Gull, Yasushi Hiraoka, Osami Niwa, Mizuki Shimanuki, and Mitsuhiro Yanagida for providing materials used in this study. We thank Dr. Frank Uhlmann for critical reading of the manuscript and useful suggestions. M.A.G. was supported by a European Molecular Biology Organization long-term fellowship. This work is supported by the Cancer Research UK and the Human Frontier Science Program research grant.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E03–11–0837. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E03–11–0837.

Abbreviations used: MAP, microtubule-associated protein; SPB, spindle pole body.

Online version of this article contains supplementary material. Online version available at www.molbiolcell.org.

References

- Bähler, J., Wu, J., Longtine, M.S., Shah, N.G., McKenzie III, A., Steever, A.B., Wach, A., Philippsen, P., and Pringle, J.R. (1998). Heterologous modules for efficient and versatile PCR-based gene targeting in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Yeast 14, 943-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellanger, J.-M., and Gönczy, P. (2003). TAC-1 and ZYG-9 form a complex that promotes microtubule assembly in C. elegans embryos. Curr. Biol. 13, 1488-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge, A.J., Morphew, M., Bartlett, R., and Hagan, I.M. (1998). The fission yeast SPB component Cut12 links bipolar spindle formation to mitotic control. Genes Dev. 12, 927-942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.P., Yin, H., and Huffaker, T.C. (1998). The yeast spindle pole body component Spc72p interacts with Stu2p and is required for proper microtubule assembly. J. Cell Biol. 141, 1169-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, C.F., and Ohkura, H. (2001). Msps protein is localized to acentrosomal poles to ensure bipolarity of Drosophila meiotic spindles. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 637-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai, A., Verma, S., Mitchison, T.J., and Walczak, C.E. (1999). Kin I kinesins are microtubule-destabilizing enzymes. Cell 96, 69-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding, D.-Q., Chikashige, Y., Haraguchi, T., and Hiraoka, Y. (1998). Oscillatory nuclear movement in fission yeast meiotic prophase is driven by astral microtubules, as revealed by continuous observation of chromosomes and microtubules in living cells. J. Cell Sci. 111, 701-712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.A., Koonrugsa, N., and Toda, T. (2002a). Spindle-kinetochore attachment requires the combined action of Kin I-like Klp5/6 and Alp14/Dis1-MAPs in fission yeast. EMBO J. 21, 6015-6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.A., Koonrugsa, N., and Toda, T. (2002b). Two kinesin-like Kin I family proteins in fission yeast regulate the establishment of metaphase and the onset of anaphase A. Curr. Biol. 12, 610-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, M.A., Vardy, L., Koonrugsa, N., and Toda, T. (2001). Fission yeast ch-TOG/XMAP215 homologue Alp14 connects mitotic spindles with the kinetochore and is a component of the Mad2-dependent spindle checkpoint. EMBO J. 20, 3389-3401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gard, D.L., and Kirschner, M.W. (1987). A microtubule-associated protein from Xenopus eggs that specifically promotes assembly at the plus-end. J. Cell Biol. 105, 2203-2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergely, F., Draviam, V.M., and Raff, J.W. (2003). The ch-TOG/XMAP215 protein is essential for spindle pole organization in human somatic cells. Genes Dev. 17, 336-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergely, F., Kidd, D., Jeffers, K., Wakefield, J.G., and Raff, J.W. (2000). D-TACC: a novel centrosomal protein required for normal spindle function in the early Drosophila embryo. EMBO J. 19, 241-252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves, M.R., Hanlon, N., Turowski, P., Hemmings, B.A., and Barford, D. (1999). The structure of the protein phosphatase 2A PR65/A subunit reveals the conformation of Its 15 tandemly repeated HEAT motifs. Cell 96, 99-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, I., and Yanagida, M. (1990). Novel potential mitotic motor protein encoded by the fission yeast cut7+ gene. Nature 347, 563-566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, I., and Yanagida, M. (1992). Kinesin-related cut7 protein associates with mitotic and meiotic spindles in fission yeast. Nature 356, 74-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, I., and Yanagida, M. (1995). The product of the spindle formation gene sad1+ associates with the fission yeast spindle pole body and is essential for viability. J. Cell Biol. 129, 1033-1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan, I.M. (1998). The fission yeast microtubule cytoskeleton. J. Cell Sci. 111, 1603-1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka, Y., Toda, T., and Yanagida, M. (1984). The NDA3 gene of fission yeast encodes β-tubulin: a cold-sensitive nda3 mutation reversibly blocks spindle formation and chromosome movement in mitosis. Cell 39, 349-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, K., Arnal, I., Desai, A., Drechsel, D.N., and Hyman, A.A. (2001). Reconstitution of physiological microtubule dynamics using purified components. Science 294, 1340-1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita, K., Habermann, B., and Hyman, A.A. (2002). XMAP 215, a key component of the dynamic microtubule cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 6, 267-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosco, K.A., Pearson, C.G., Maddox, P.S., Wang, P.J., Adams, I.R., Salmon, E.D., Bloom, K., and Huffaker, T.C. (2001). Control of microtubule dynamics by stu2p is essential for spindle orientation and metaphase chromosome alignment in yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 2870-2880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bot, N., Tsai, M.-C., Andrews, R.K., and Ahringer, J. (2003). TAC-1, a regulator of microtubule length in the C. elegans embryo. Curr. Biol. 13, 1499-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.J., Gergely, F., Jeffers, K., Peak-Chew, S.Y., and Raff, J.W. (2001). Msps/XMAP215 interacts with the centrosomal protein D-TACC to regulate microtubule behaviour. Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 643-649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, L.R., Carter, P., Thierry-Mieg, D., and Kemphues, K. (1998). ZYG-9, a Caenorhabditis elegans protein required for microtubule organization and function, is a component of meiotic and mitotic spindle poles. J. Cell Biol. 141, 1159-1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, S., Klar, A., and Nurse, P. (1991). Molecular genetic analyses of fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Methods Enzymol. 194, 773-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabeshima, K., Kurooka, H., Takeuchi, M., Kinoshita, K., Nakaseko, Y., and Yanagida, M. (1995). p93dis1, which is required for sister chromatid separation, is a novel microtubule and spindle pole body-associating protein phosphorylated at the Cdc2 target sites. Genes Dev. 9, 1572-1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabeshima, K., Nakagawa, T., Straight, A.F., Murray, A., Chikashige, Y., Yamashita, Y.M., Hiraoka, Y., and Yanagida, M. (1998). Dynamics of centromeres during metaphase-anaphase transition in fission yeast: Dis1 is implicated in force balance in metaphase bipolar spindle. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 3211-3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabetani, A., Koujin, T., Tsutsumi, C., Haraguchi, T., and Hiraoka, Y. (2001). A conserved protein, Nuf2, is implicated in connecting the centromere to the spindle during chromosome segregation: a link between the kinetochore function and the spindle checkpoint. Chromosoma 110, 322-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaseko, Y., Goshima, G., Morishita, J., and Yanagida, M. (2001). M phase-specific kinetochore proteins in fission yeast microtubule-associating Dis1 and Mtc1 display rapid separation and segregation during anaphase. Curr. Biol. 11, 537-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaseko, Y., Nabeshima, K., Kinoshita, K., and Yanagida, M. (1996). Dissection of fission yeast microtubule associating protein p93dis1: regions implicated in regulated localization and microtubule interaction. Genes Cells 1, 633-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuwald, A.F., and Hirano, T. (2000). HEAT repeats associated with condensins, cohesins, and other complexes Involved in chromosome-related functions. Genome Res. 10, 1445-1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohkura, H., Garcia, M.A., and Toda, T. (2001). Dis1/TOG universal microtubule adaptors-one MAP for all? J. Cell Sci. 114, 3805-3812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, C.G., Maddox, P.S., Zarzar, T.R., Salmon, E.D., and Bloom, K. (2003). Yeast kinetochores do not stabilize Stu2p-dependent spindle microtubule dynamics. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 4181-4195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G., Grueneberg, U., Knop, M., and Schiebel, E. (1999). Interaction of the yeast γ-tubulin complex-binding protein Spc72p with Kar1p is essential for microtubule function during karyogamy. EMBO J. 18, 4180-4195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe, P., Hirata, D., Childs, D., Vardy, L., and Toda, T. (1998). Identification of novel temperature-sensitive lethal alleles in essential β-tubulin and nonessential α2-tubulin genes as fission yeast polarity mutants. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 1757-1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raff, J.W. (2002). Centrosomes and cancer: lessons from a TACC. Trends Cell Biol. 12, 222-225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato, M., Vardy, L., Koonrugsa, N., Tournier, S., Millar, J.B.A., and Toda, T. (2003). Deletion of Mia1/Alp7 activates Mad2-dependent spindle assembly checkpoint in fission yeast. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 764-766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato, M., Watanabe, Y., Akiyoshi, Y., and Yamamoto, M. (2002). 14-3-3 protein interferes with the binding of RNA to the phosphorylated form of fission yeast meiotic regulator Mei2p. Curr. Biol. 12, 141-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severin, F., Habermann, B., Huffaker, T., and Hyman, T. (2001). Stu2 promotes mitotic spindle elongation in anaphase. J. Cell Biol. 153, 435-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasu-Hiza, M., Coughlin, P., and Mitchison, T. (2003). Identification of XMAP215 as a microtubule-destabilizing factor in Xenopus egg extract by biochemical purification. J. Cell Biol. 161, 349-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souès, S., and Adams, I.R. (1998). SPC 72, a spindle pole component required for spindle orientation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Sci. 111, 2809-2818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srayko, M., Quintin, S., Schwager, A., and Hyman, A.A. (2003). Caenorhabditis elegans TAC-1 and ZYG-9 form a complex that is essential for long astral and spindle microtubules. Curr. Biol. 13, 1506-1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tournebize, R., Popov, A., Kinoshita, K., Ashford, A.J., Rybina, S., Pozniakovsky, A., Mayer, T.U., Walczak, C.E., Karsenti, E., and Hyman, A.A. (2000). Control of microtubule dynamics by the antagonistic activities of XMAP215 and XKCM1 in Xenopus egg extracts. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 13-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui, T., Maekawa, H., Pereira, G., and Schiebel, E. (2003). The XMAP215 homologue Stu2 at yeast spindle pole bodies regulates microtubule dynamics and anchorage. EMBO J. 22, 4779-4793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Breugel, M., Drechsel, D., and Hyman, A. (2003). Stu2p, the budding yeast member of the conserved Dis1/XMAP215 family of microtubule-proteins is a plus end-binding microtubule destabilizer. J. Cell Biol. 161, 359-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardy, L., and Toda, T. (2000). The fission yeast γ-tubulin complex is required in G1 phase and is a component of the spindle-assembly checkpoint. EMBO J. 19, 6098-6111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak, C.E., Gan, E.C., Desai, A., Mitchison, T.J., and Kline-Smith, S.L. (2002). The microtubule-destabilizing kinesin XKCM1 is required for chromosome positioning during spindle assembly. Curr. Biol. 12, 1885-1889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.J., and Huffaker, T.C. (1997). Stu2p: a microtubule-binding protein that is essential component of the yeast spindle pole body. J. Cell Biol. 139, 1271-1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West, R.R., Vaisberg, E.V., Ding, R., Nurse, P., and McIntosh, J.R. (1998). cut11+: a gene required for cell cycle-dependent spindle pole body anchoring in the nuclear envelope and bipolar spindle formation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Biol. Cell 9, 2839-2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, X., Kahana, J.A., Silver, P.A., Morphew, M.K., McIntosh, J.R., Fitch, I.T., Carbon, J., and Saunders, W.S. (1999). Slk19p is a centromere protein that functions to stabilize mitotic spindles. J. Cell Biol. 146, 415-426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.