Abstract

The existence of cobalamin (Cbl)-dependent enzymes that are members of the radical S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) superfamily was previously predicted based on bioinformatic analysis. A number of these are Cbl-dependent methyltransferases but the details surrounding their reaction mechanisms have remained unclear. In this report we demonstrate the in vitro activity of GenK, a Cbl-dependent radical SAM enzyme that methylates an unactivated sp3 carbon during the biosynthesis of gentamicin, an aminoglycoside antibiotic. Experiments to investigate the stoichiometry of the GenK reaction revealed that one equivalent each of 5′-deoxyadenosine and S-adenosyl-homocysteine are produced for each methylation reaction catalyzed by GenK. Furthermore, isotope-labeling experiments demonstrate that the S-methyl group from SAM is transferred to Cbl and the aminoglycoside product during the course of the reaction. Based on these results, one mechanistic possibility for the GenK reaction can be ruled out and further questions regarding the mechanisms of Cbl-dependent radical SAM methyltransferases, in general, are discussed.

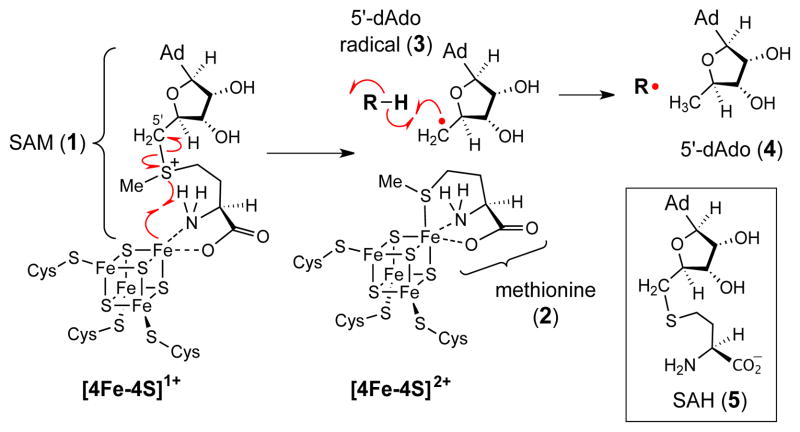

The radical S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM, 1) superfamily of enzymes1,2 comprise a diverse array of biological catalysts that share a common [4Fe-4S] cluster coordinated by three cysteines of a highly conserved CxxxCxxC motif in their active sites.3 The fourth iron of the cluster interacts with a bound SAM. Upon reduction to the +1 redox state, the [4Fe-4S]+ cluster donates an electron through inner-sphere e− transfer to trigger the reductive homolysis of the C5′–S bond of SAM (1) to produce methionine (2) and a 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical (5′-dAdo•, 3). The latter can be used as a radical initiator in the subsequent chemical transformation catalyzed by the corresponding enzymes (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Initial reaction catalyzed by radical SAM enzymes.

A subset of radical SAM enzymes contains a cobalamin (Cbl) binding domain at the N-terminus. This expanding group of enzymes is found in a number of biosynthetic pathways,4,5 where the individual enzymes are implicated in a wide range of transformations including the methylation of unactivated C and P centers and the formation of the isocyclic ring systems of chlorophyll and bacteriochlorophyll.6–9 Thus far, the activities of only two Cbl-dependent radical SAM enzymes have been demonstrated in vitro. One is PhpK,10 which catalyzes methylation of the phosphinate group of 2-acetylamino-4-hydroxyphosphinyl-butanoate in the biosynthesis of phosalacine in Kitasatospora phosalacinea. A more recent example is TsrM, which catalyzes the conversion of tryptophan to 2-methyl-tryptophan in the biosynthesis of thiostrepton A.11 In both cases the detailed mechanism remains unknown.

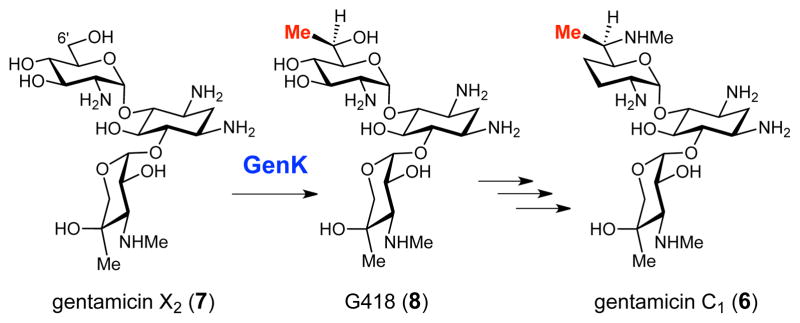

Gentamicins are aminoglycoside antibiotics produced by Micromonospora echinospora.12 Sequence analysis of the gentamicin C1 (6) biosynthetic gene cluster suggested that the methylation step at C-6′ of GenX2 (7) to yield the clinically useful geneticin (G418, 8),13,14 is likely catalyzed by a Cbl-dependent radical SAM enzyme, GenK (see Scheme 2).15 This assignment is supported by gene knockout experiments reported recently.16,17 An alignment of 13 putative Cbl-dependent radical SAM sp3 C-methyltransferases (including GenK, see Fig. S1) suggests that these enzymes harbor a single [4Fe-4S] cluster per monomer because only the cysteine residues comprising the CxxxCxxC motif are conserved. In order to shed light on the mechanisms of the reactions catalyzed by this fascinating set of enzymes, we undertook a study of the GenK-catalyzed reaction.

Scheme 2.

The C-6′ methylation reaction catalyzed by GenK in the gentamicin biosynthetic pathway.

The genK gene was amplified from the genomic DNA of M. echinospora using PCR (polymerase chain reaction) and was cloned into a pET24 vector. The recombinant genK was heterologously expressed in Escherichia coli. Although GenK was quite well overproduced, the enzyme was only detected in insoluble inclusion bodies. Thus, it was subjected to a denaturation (with 5 M urea) and refolding protocol as described in the Supporting Information (SI). The refolded GenK was then incubated with FeCl3 and Na2S under anaerobic conditions for reconstitution of the [4Fe-4S] cluster. Unbound iron and sulfide was removed by gel filtration chromatography. The purity of refolded, reconstituted GenK was assessed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. S2). The UV-visible spectrum of reconstituted GenK and the bleaching of the characteristic absorbance shoulder at 420 nm in the presence of sodium dithionite are consistent with the presence of a bound Fe/S cluster (Fig. S2). Further analysis revealed that 3.5 ± 0.9 eq of iron and 3.8 ± 1.1 eq of sulfide are bound to each GenK monomer indicating that GenK contains a single [4Fe-4S] cluster as predicated by the amino acid sequence alignment (Fig. S1).

The activity of GenK was assayed using 1 mM commercially available GenX2 (7) as substrate in 50 mM Tris•HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 10 mM DTT, 4 mM SAM, and 1 mM methylcobalamin (MeCbl) or hydroxocobalamin (HOCbl). An experiment comparing GenK activity over a range of MeCbl concentrations showed that GenK activity is nearly maximized in the presence of 1 mM MeCbl (Fig S3). NADPH (4 mM) and methyl viologen (MV, 1 mM) were employed as the electron source and mediator, respectively, to reduce the GenK [4Fe-4S] cluster to the active +1 redox state. A combination of E. coli flavodoxin, flavodoxin reductase, and NADPH is also capable of activating GenK (Fig S4). Although dithionite is commonly used to activate radical SAM enzymes for in vitro studies, it is not effective for GenK. Neither NADPH and benzyl viologen (BV), dithionite and MV, nor dithionite and BV are capable of activating GenK (Fig S4). The coordination of SO2− to the corrinoid cobalt18 may compromise the ability of dithionite to support multiple turnovers with Cbl-dependent radical SAM enzymes.

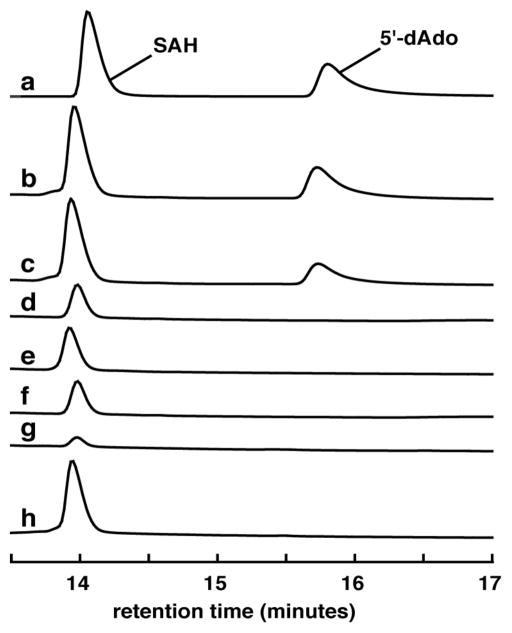

The GenK reaction was monitored under two different reverse-phase HPLC conditions: one to detect the formation of 5′-dAdo (4) and SAH (5) and another to detect GenX2 (7) to G418 (8). Both are described in the SI. The results shown in Figures 1 and 2 clearly indicate that GenK converts GenX2 (7) to G418 (8) in the presence of either MeCbl or HOCbl (but not without Cbl), and that both 5′-dAdo (4) and SAH (5) are formed as co-products during turnover. Reconstitution of GenK with iron and sulfide is required to obtain activity. Since 5′-dAdo (4) is not generated in the absence of GenX2, its production is coupled to G418 formation. Quantification of 5′-dAdo in trace b and c (Fig. 1) and G418 in traces b and c (Fig. 2) gives 0.49, 0.32, 0.49, and 0.40 mM, respectively demonstrating that 5′-dAdo and G418 are produced at a ratio close to 1:1. The presence of SAH in assays without GenK indicates that a notable extent of Cbl methylation takes place non-enzymatically under the conditions employed even when MeCbl is used as substrate. This suggests that the C-Co bond of MeCbl is prone to non-enzymatic cleavage during the assay.

Figure 1.

HPLC traces showing the production of both 5′-dAdo (4) and SAH (5) during the GenK reaction. Trace (a) is a standard composed of authentic 5′-dAdo (4) and SAH (5). The remaining traces result from reaction mixtures prepared as described in the text containing (b) MeCbl, (c) HOCbl, (d) MeCbl but no GenK, (e) HOCbl but no GenK, (f) MeCbl but no GenX2, (g) no Cbl, (h) MeCbl and non-reconstituted GenK. Detector was set at 260 nm.

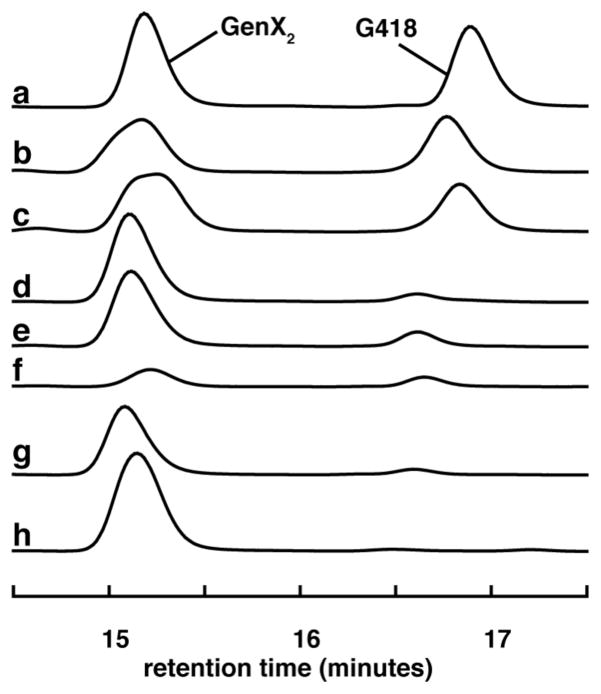

Figure 2.

HPLC traces showing conversion of GenX2 (7) to G418 (8) in the presence of GenK. Prior to HPLC analysis, the assay mixture was subjected to the reaction with 1-fluoro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (DNFB) (see SI for details). Absorbance was monitored at 340 nm to detect FDNB-derivatized aminoglycosides. Trace (a) is a standard composed of derivatized, authentic GenX2 (7) and G418 (8). Traces b–h are as described in the legend of Fig. 1. The small peaks at ~16.6 min in traces d–g and ~15.4 min in trace f are unrelated to product and substrate.

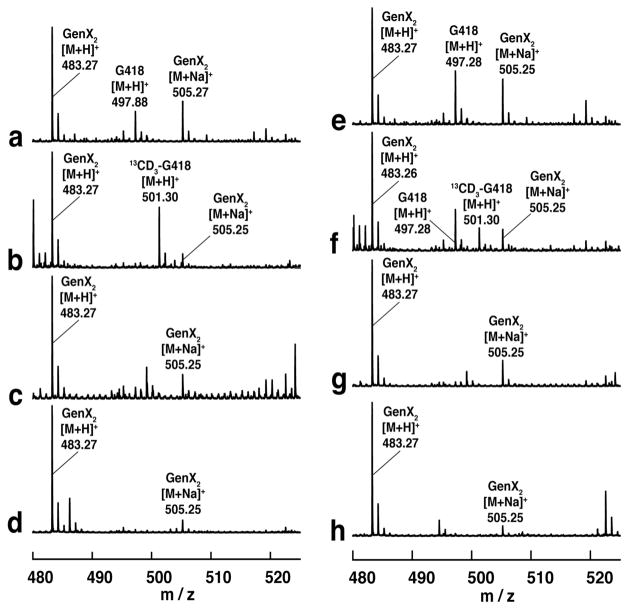

In order to confirm the role of cobalamin during methyl transfer from SAM to GenX2, assays were conducted in the presence of either HOCbl or MeCbl and 13CD3-methyl-SAM followed by mass spectroscopic analysis of G418 and Cbl. As expected, when 13CD3-methyl-SAM was used as a substrate in a GenK reaction, the 13CD3-label was detected in both G418 (Fig. 3) and Cbl (Fig. S5). These observations, together with the established Cbl-dependence of the GenK reaction, indicate that the S-methyl substituent in SAM is transferred to Cbl and, subsequently, to GenX2 to give G418.

Figure 3.

Mass spectra of aminoglycoside substrate and product displaying incorporation of 13CD3 from 13CD3-methyl-SAM into product. The spectra correspond to assays with (a) HOCbl + unlabeled SAM, (b) HOCbl + 13CD3-methyl-SAM, (c) HOCbl + unlabeled SAM without GenK, (d) HOCbl + 13CD3-methyl-SAM without GenK, (e) MeCbl + unlabeled SAM, (f) MeCbl + 13CD3-methyl-SAM, (g) MeCbl + unlabeled SAM without GenK, (h) MeCbl + 13CD3-methyl-SAM without GenK.

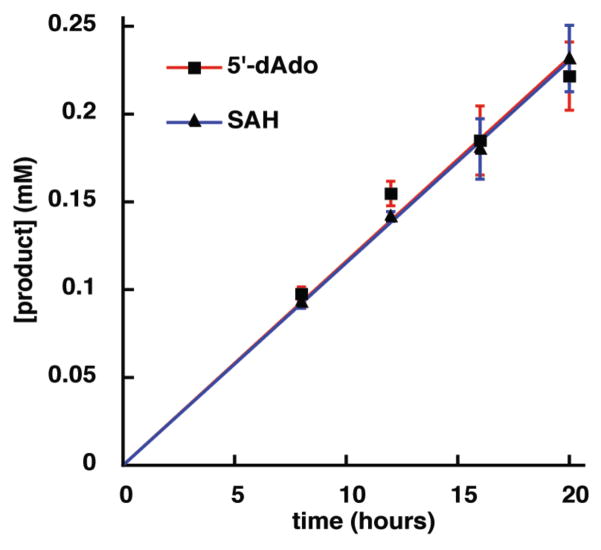

The quantity of 5′-dAdo and SAH produced by GenK was measured after an 8 hr incubation, as a function of [GenK] (2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 μM) revealing a linear relationship between the two (Fig S6). GenK (10 μM) was assayed over a timecourse to determine the stoichiometry of 5′-dAdo and SAH formation (depicted in Fig. 4). The results, obtained after subtraction of non-enzymatically produced SAH, clearly show that 5′-dAdo and SAH are produced in a 1:1 ratio. As mentioned above, Fig. 1 and 2 demonstrate that 5′-dAdo and G418 are also produced in a 1:1 ratio.

Figure 4.

Stoichiometry of 5′-dAdo and SAH production during the GenK reaction.

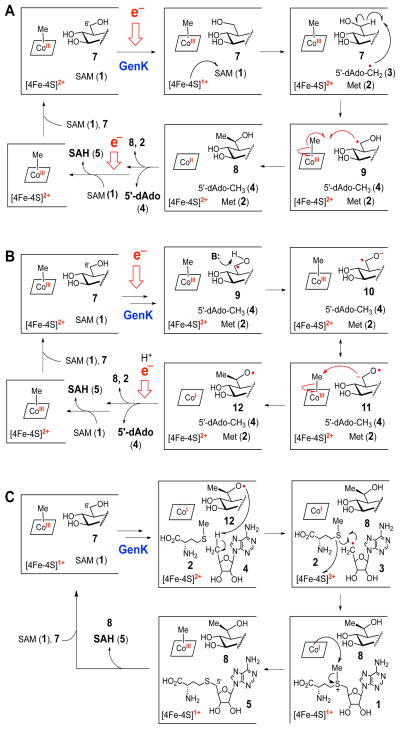

Several mechanisms can be envisioned for the GenK-catalyzed conversion of GenX2 (7) to G418 (8) (Scheme 3). In the first mechanism (Scheme 3A), the 5′-dAdo• radical (3) generated via the reductive cleavage of SAM abstracts a hydrogen atom from C-6′ of the substrate 7. The resulting substrate radical (9) then accepts a methyl radical from Me-Cbl to generate Cbl(II) and the G418 product (8). A similar mechanism has been proposed for the putative C-methyl-transferase Fom3, which is a Cbl-dependent radical SAM enzyme catalyzing C-2 methylation of 2-hydroxyethylphosphonate in fosfomycin biosynthesis.19,20 In this mechanism, Me-Cbl could be regenerated after each turnover via reduction of Cbl(II) to Cbl(I), followed by methylation by SAM.

Scheme 3.

Possible GenK reaction mechanisms. (A) GenX2 radical (9) is quenched by the transfer of methyl radical from Me-Cbl(III) to give Cbl(II), which is reduced to Cbl(I) in order to accept a new methyl group from SAM. (B) Transfer of methyl cation to GenX2 ketyl radical (11) followed by reduction and protonation of product radical (12). (C) Product radical (12) is quenched by a hydrogen from 5′-dAdo (4) to give 5′-dAdo• (3), which can be re-incorporated into SAM. In this mechanism, a single equivalent of SAM can serve as a source of both 5′-dAdo• (3) and CH3+.

Given that the transfer of a methyl radical is heretofore unprecedented among the Cbl-dependent methyltransferases, mechanisms involving the transfer of a methyl cation from Me-Cbl were also considered (Schemes 3B and 3C). The early steps of these alternative mechanisms are identical to those of Scheme 3A. However, after hydrogen atom abstraction (7 → 9), the radical intermediate 9 is deprotonated to form the ketyl radical 10/11, similar to those observed in the reactions catalyzed by DesII21–23 and (R)-2-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydratase.24,25 Nucleophilic attack by 11 at Me-Cbl leads to the transfer of an electrophilic methyl cation (11 → 12), yielding a Cbl(I) intermediate (as in traditional Me-Cbl chemistry)26,27 and an alkoxide product radical (12). The radical 12 could then be quenched by an external electron and proton (Scheme 3B), or via hydrogen atom transfer from 5′-dAdo (4) (Scheme 3C). In this latter mechanism, SAM (1) is regenerated while restoring the [4Fe-4S] cluster to the +1 redox state. The resultant SAM could then methylate Cbl(I), releasing SAH (5) as the sole adenosylated product. Thus, in this mechanism, the input of exogenous electrons is not required and only a single equivalent of SAM is consumed during each catalytic cycle. This is in contrast to mechanisms A and B, in which two equivalents of SAM (1) (in addition to two reducing equivalents) are consumed for each methyl transfer event catalyzed by GenK.

The observation that 5′-dAdo (4), SAH (5), and G418 (8) are each produced in equivalent amounts (Figure 4) is consistent with mechanisms A and B, but not C. Thus, mechanism C can be ruled out based on our current data. The catalytic cycle of GenK, and likely other Cbl-dependent radical SAM methyltransferases, consumes two SAM molecules and two reducing equivalents. The first molecule of SAM acts as the source of 5′-dAdo• (3), which abstracts a hydrogen atom from C-6′ of GenX2 (7) to give 5′-dAdo (4) and the GenX2 radical (9). The second SAM is used to re-methylated Cbl(I) during turnover to regenerate Me-Cbl for a subsequent round of catalysis. Efforts are currently underway to further elucidate the chemical mechanism of this intriguing enzyme. Although it is a technical challenge to study Cbl-dependent radical SAM enzymes, this emerging class of biocatalysts offers considerable potential for the discovery of new and unprecedented enzyme chemistry.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM035906) and the Robert Welch Foundation (F-1511). R.M.M is a recipient of the Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (GM103181).

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Details regarding the cloning, expression, refolding, and reconstitution of GenK along with HPLC protocols and a list of abbreviations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Frey PA, Hegeman AD, Ruzicka FJ. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;43:63–88. doi: 10.1080/10409230701829169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shepard EM, Broderick JB. In: Comprehensive Natural Products II, Chemistry and Biology. Mander L, Liu Hw, editors. Vol. 8. Elsevier; Oxford: 2010. pp. 625–661. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sofia HJ, Chen G, Hetzler BG, Reyes-Spindola JF, Miller NE. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:1097–1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.5.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Booker SJ. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2009;13:58–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Q, van der Donk WA, Liu W. Acc Chem Res. 2012;45:555–564. doi: 10.1021/ar200202c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuzuyama T, Hidaka T, Kamigiri K, Imai S, Seto H. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1992;45:1812–1814. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamigiri K, Hidaka T, Imai S, Murakami T, Seto H. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1992;45:781–787. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.45.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chew AGM, Bryant DA. Ann Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:113–129. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gough SP, Peterson BO, Duus JØ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6908–6913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.12.6908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werner WJ, Allen KD, Hu K, Helms GL, Chen BS, Wang SC. Biochemistry. 2011;50:8986–8988. doi: 10.1021/bi201220r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierre S, Guillot A, Benjdia A, Sandstrom C, Langella P, Berteau O. Nature Chem Biol. 2012;8:957–959. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinstein MJ, Luedemann GM, Oden EM, Wagman GH, Rosselet JP, Marquez JA, Coniglio CT, Charney W, Herzog HL, Black J. J Med Chem. 1963;6:463–464. doi: 10.1021/jm00340a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagman GH, Weinstein MJ. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1980;34:537–557. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.34.100180.002541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Testa RT, Tilley BC. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1976;29:140–146. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.29.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Unwin J, Standage S, Alexander D, Hosted T, Jr, Horan AC, Wellington EM. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2004;57:436–445. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.57.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park JW, Hong JSJ, Parajuli N, Jung WS, Park SR, Lim SK, Sohng JK, Yoon YJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:8399–8404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803164105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong W, Yan L. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 2012;58:349–356. doi: 10.2323/jgam.58.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salnikov DS, Silaghi-Dumitrescu R, Makarov SV, van Eldik R, Boss GR. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:9831–9834. doi: 10.1039/c1dt10219b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woodyer RD, Li G, Zhao H, van der Donk WA. Chem Commun. 2007;4:359–361. doi: 10.1039/b614678c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nair SK, van der Donk WA. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;505:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruszczycky MW, Choi S-h, Liu H-w. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2359–2369. doi: 10.1021/ja909451a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruszczycky MW, Choi S-h, Mansoorabadi SO, Liu H-w. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:7292–7295. doi: 10.1021/ja201212f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ruszczycky MW, Choi Sh, Liu Hw. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim J, Darley DJ, Buckel W, Pierik AJ. Nature. 2008;452:239–242. doi: 10.1038/nature06637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buckel W. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:6779–6787. doi: 10.1002/anie.200900771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matthews RG. Acc Chem Res. 2001;34:681–689. doi: 10.1021/ar0000051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matthews RG, Koutmos M, Datta S. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2008;18:658–666. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.