Abstract

Atopic dermatitis is a common inflammatory skin disease with a strong heritable component. Pathogenetic models consider keratinocyte differentiation defects and immune alterations as scaffolds1, and recent data indicate a role for autoreactivity in at least a subgroup of patients2. With filaggrin (FLG) a major locus causing a skin barrier deficiency was identified3. To better define risk variants and identify additional susceptibility loci, we densely genotyped 2,425 German cases and 5,449 controls using the Immunochip array, followed by replication in 7,196 cases and 15,480 controls from Germany, Ireland, Japan and China. We identified 4 new susceptibility loci for atopic dermatitis and replicated previous associations. This brings the number of atopic dermatitis risk loci reported in individuals of European ancestry to 11. We estimate that these susceptibility loci together account for 14.4% of the heritability for atopic dermatitis.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have shown a remarkable overlap across immune-mediated (IM) diseases4. In addition to FLG, two European GWAS on atopic dermatitis established four susceptibility loci (C11orf30, OVOL1, ACTL9, and RAD50/IL13/KIF3A)5,6. At C11orf30 the same allele also confers risk to asthma7 and Crohn’s disease8. For the RAD50/IL13 locus agonistic effects were observed for asthma9 and antagonistic effects for psoriasis10. Two further loci were reported in a Chinese GWAS (TNFRSF6B/ZGPAT, TMEM232/SLC25A46)11. All loci were confirmed in a recent Japanese GWAS, which additionally reported 8 new loci (IL1RL1-IL18R1-IL18RAP, the MHC, OR10A3/NLRP10, GLB1, CCDC80, CARD11, ZNF365, CYP24A1/PFDN4)12. However, the causal variants at all loci apart from FLG are unknown. To better define susceptibility variants and to evaluate loci implicated in other IM diseases, we genotyped 2,425 German atopic dermatitis cases and 5,449 German population controls (panel A in Supplementary Table 1) using the Immunochip array13, followed by replication in four independent collections (panel B-D in Supplementary Table 1).

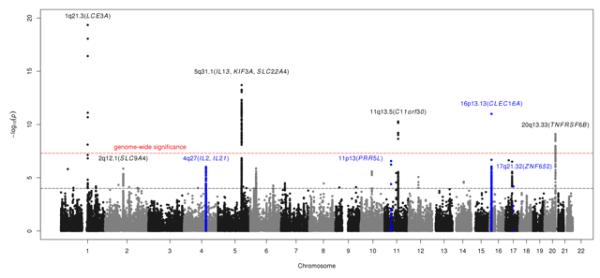

After quality control, 128,830 SNPs with a minor allele frequency >1% were available for analysis (Online Methods). The initial comparison of case-control frequencies yielded 131 and 663 SNPs within five and 33 genomic loci with PImmunochip<5×10−8 and PImmunochip<10−4, respectively (Figure 1). Of the five atopic dermatitis loci previously reported in European ancestry populations, three reached conservative genome-wide significance (GWS, i.e. P<5×10−8; P1q21.3=4.51×10−20, P5q31.1=1.99×10−14 and P11q13.5=5.22×10−11) (Table 1a). For all three loci, we observed stronger association signals as compared to previously reported SNPs5,6 (Supplementary Table 2), where Immunochip data were used to refine the 5q31.1 locus6. Variant rs72702813 at 1q21.3 is located 5275 bases upstream of the late cornified envelope gene 3 A (LCE3A), a member of the LCE3 group which contains a psoriasis risk-associated deletion (LCE3C_LCE3B-del)14 and encodes proteins involved in barrier repair with differential expression in atopic dermatitis15.

Figure 1. Manhattan plot of Immunochip association statistics highlighting atopic dermatitis susceptibility loci.

Red horizontal line indicates a genome-wide significance threshold of 5×10−8. Black horizontal line indicates threshold for follow-up genotyping of the most strongly associated SNPs (n=34) with PImmunochip<10−4 from each associated locus in an independent case-control collection (panel B in Supplementary Table 1).

SNPs within 5 known (Table 1a) and 4 newly associated loci (depicted in blue; Table 1b) achieve the genome-wide significance threshold for association with atopic dermatitis in the combined analysis of Immunochip discovery and replication (panel A-C, Supplementary Table 1).

Table 1. Susceptibility loci associated with atopic dermatitis in Europeans at genome-wide significance level.

| Key genes (+N additional in locus) |

Discovery Immunochip (2,425/5,449) |

Replication (1,951/4,599) |

Immunochip+Replication (4,376/10,048) |

Associations to other traits |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr | Association boundaries (kb) |

dbSNP id | A1 | A2 | AF(cases) | AF(controls) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | Pcombined | OR (95% CI) | ||

|

(a) Previously reported atopic dermatitis susceptibility loci*

meeting genome-wide significance (Pcombined < 5×10−8) | ||||||||||||||

| 1q21.3 | 150803-151051 | rs72702813 | T | G | 0.08147 | 0.04056 | LCE3A (15) | 4.51×10−20 | 1.91(1.66-2.19) | 2.22×10−16 | 2.46(1.98-3.04) | 1.49×10−33 | 2.06(1.83-2.31) | PS |

| 2q12.1 | 102225-102619 | rs759382 | C | A | 0.2866 | 0.2454 | SLC9A4 (5) | 1.40×10−6 | 1.21(1.12-1.30) | 9.69×10−6 | 1.23(1.12-1.35) | 6.01×10−11 | 1.22(1.15-1.29) | AS, CD, CelD, EC, WBCT |

| 5q31.1 | 131812-132167 | rs848 | T | G | 0.2679 | 0.2067 | IL13 (8) | 1.99×10−14 | 1.36(1.25-1.47) | 2.33×10−15 | 1.47(1.34-1.62) | 8.22×10−28 | 1.40(1.32-1.49) | AS§, CD, IgE§, PS§, HL§, PIC, FIB, EC, CRP |

| 11q13.5 | 75724-76017 | rs7110818 | A | G | 0.4992 | 0.4392 | C11orf30 (1) | 5.22×10−11 | 1.25(1.17-1.34) | 7.20×10−7 | 1.35(1.20-1.53) | 3.33×10−16 | 1.28(1.21-1.36) | AS, CD, ALRH, IgEgs, UC |

| 20q13.33 | 61678-61872 | rs909341 | A | G | 0.1809 | 0.226 | TNFRSF6B (8) | 7.73×10−10 | 0.76(0.70-0.83) | 1.90×10−7 | 0.77(0.70-0.85) | 7.77×10−16 | 0.77(0.72-0.82) | CD, UC§, poIBD, GL |

|

| ||||||||||||||

|

(b) New atopic dermatitis susceptibility loci meeting genome-wide significance (Pcombined < 5×10−8) | ||||||||||||||

| 4q27 | 123204-123784 | rs17389644 | A | G | 0.2774 | 0.2396 | IL2/IL21 (2) | 1.16×10−6 | 1.21(1.12-1.30) | 0.0026 | 1.16(1.05-1.28) | 1.39×10−8 | 1.19(1.12-1.26) | RA, CelD, UC, T1D, T1DA, IgEgs, PSNP, AA |

| 11p13 | 36355-36438 | rs12295535 | A | G | 0.04045 | 0.02376 | PRR5L | 2.71×10−7 | 1.63(1.35-1.96) | 4.32×10−7 | 1.75(1.41-2.17) | 7.96×10−13 | 1.68(1.46-1.93) | - |

| 16p13.13 | 10930-11218 | rs2041733 | A | G | 0.4903 | 0.4528 | CLEC16A/DEXI | 1.00×10−11 | 1.26(1.18-1.35) | 3.07×10−5 | 1.18(1.09-1.28) | 3.44×10−15 | 1.23(1.17-1.29) | MS, T1D, T1DA, PBC, IgA, AA, ALRH |

| 17q21.32 | 44641-44875 | rs16948048 | G | A | 0.4252 | 0.3848 | ZNF652 (5) | 6.46×10−5 | 1.15(1.07-1.23) | 8.45×10−6 | 1.20(1.11-1.30) | 2.92×10−9 | 1.17(1.11-1.23) | H |

We replicated the association at the 20q13.33/TNFRSF6B and the 2q12.1/SLCA4 locus, previously reported in Chinese and Japanese populations, respectively, with GWS in Europeans. Two other known atopic dermatitis loci in Europeans from previous GWAS (OVOL1, ACTL9) are sparsely covered on the Immunochip (see also main text and Supplementary Fig. 1). Chr: chromosome of marker; Association boundaries: association boundaries for each index SNP (Online Methods). Genomic positions were retrieved from NCBI’s dbSNP build v130 (genome build hg18); dbSNP id: rs ID; A1: minor allele (corresponds to risk allele except for rs909341 that is protective); A2: major allele; AF: allele frequency of A1 estimated from Immunochip and replication; Key gene(s): candidate gene(s) in the region; P/OR: P-value and corresponding odds ratio and 95% confidence interval with respect to minor allele. For each panel, numbers of atopic dermatitis cases/controls are displayed in parentheses. Associations to other traits: Overlaps with other disease phenotypes (listed if anywhere within association boundaries, § = known risk SNP in high LD (r2>0.9) with atopic dermatitis hit SNP, Online Methods): AA=Alopecia areata, ALRH=Allergic rhinitis, AS=Asthma, CD=Crohn’s disease, CelD=Celiac disease, CRP=C-reactive protein levels, EC=Eosinophil counts, FIB=Fibrinogen, GL=Glioma, H=Height, HL=Hodgkin's lymphoma, IgA=Immunoglobulin A, IgE=IgE levels, IgEgs=IgE grass sensitization, MS=Multiple sclerosis, PBC=Primary biliary cirrhosis, PIC=Platelet counts, poIBD=pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease, PS=Psoriasis, PSNP=Progressive supranuclear palsy, RA=Rheumatoid arthritis, T1D=Type 1 diabetes, T1DA=Type 1 diabetes autoantibodies, UC=Ulcerative colitis, WBCT=White blood cell types.

Analysis of the LD pattern showed that rs72702813 does not tag the psoriasis deletion (D′=1.0 and r2=0.09 with proxy SNP rs411278814), but is in moderate LD (D′=0.63; r2=0.38) with the known FLG mutation 2282del4 (Supplementary Table 3). Conditioning on FLG mutations (R501X, 2282del4, R2447X, S3247X), rs72702813 no longer showed association (Pcond=0.94; OR (95% CI)=0.99 (0.77-1.28)).

Another locus at CLEC16A/16p13.13, not previously known to be associated with atopic dermatitis, attained GWS (Prs2041733=1.00×10−11; OR (95% CI)=1.26 (1.18-1.35)) (Table 1b). For the two remaining established loci, we observed a significant signal for OVOL1/11q13.1 (Prs11820062=3.60×10−6), but not for ACTL9/19p13.2 (Prs2967682=0.18) (Supplementary Fig. 1), which, however, is sparsely covered on the Immunochip (r2=0.15 between rs2967682 and lead SNP rs2164983 from a previous GWAS6). Furthermore, we replicated the association at the 20q13.33/TNFRSF6B locus (Prs909341=7.73×10−10; OR (95% CI)=0.76 (0.70-0.83)), previously reported in Chinese population, with GWS in Europeans. This gene encodes a soluble decoy receptor (DCR3) that acts as immunomodulator (e.g. support of Th2 polarization, which is a hallmark feature of atopic dermatitis)16. DcR3 is overexpressed in inflamed epithelia17,18, and increased serum levels were reported in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. In line with this, we observed a slight overexpression in serum from atopic dermatitis patients (PFisher=0.00049, Supplementary Fig. 2). Immunohistochemistry showed strong epidermal staining with, however, no clear differences between atopic dermatitis lesional and healthy skin (Supplementary Fig. 3). No proxy SNPs (r2>0.5) were available for the Chinese 5q22.1 locus (TMEM232/SLC25A46). For the recently reported Japanese loci, we observed significant associations at 2q12.1 (IL1RL1-IL18R1-IL18RAP, Prs13015714=2.81×10−5, OR (95% CI)=1.18 (1.09-1.27)), 6p21.3 (GPSM3, Prs176095=2.53×10−5, OR (95% CI)=0.83 (0.76-0.90), and 7p22 (CARD11, Prs6978200=2.34×10−3, OR (95% CI)=1.12 (1.04-1.20), r2=0.58 with reported SNP rs4722404). No association was seen for 3p21.33 (GLB1, Prs35480293=0.80, r2=0.92 with reported SNP rs6780220) and 10q21.2 (ZNF365, Prs10995251=0.08). The 3q13.2 (CCDC80) and 20q13 (CYP24A1-PFDN4) loci have more limited coverage on the Immunochip array.

To identify additional susceptibility loci, we analyzed the most strongly associated SNPs (n=34) with PImmunochip<10−4 after the clumping procedure from each associated locus in an independent 794 German cases and 3,338 controls (panel B in Supplementary Table 1). SNPs replicated at the 0.05 level (n=15, Supplementary Table 4) were further genotyped in 1,157 Irish childhood cases and 1,261 controls (panel C in Supplementary Table 1). In a meta-analysis (PImmunochip+Repl) of the discovery (PImmunochip) and replication (PRepl) stage (panels A-C) SNPs within six distinct regions met the GWS threshold (Table 1b). Again association was observed at 16p13.13 for SNP rs2041733 in CLEC16A (PImmunochip+Repl=3.44×10−15; ORImmunochip+Repl (95% CI)=1.23 (1.17-1.29)). CLEC16A encodes a sugar-binding, C-type lectin expressed on B-lymphocytes, natural killer and dendritic cells, which is functionally active through an Immunoreceptor Tyrosine–based Activation Motif (ITAM)19. Several CLEC16A SNPs have been associated with IM diseases such as multiple sclerosis and type 1 diabetes20,21, and alopecia areata22, a frequent comorbidity of AD.

At 11p13, a significant association was observed for rs12295535 in PRR5L (PImmunochip+Repl=7.96×10−13; ORImmunochip+Repl (95% CI)=1.68 (1.46-1.93)), which encodes a protein that promotes apoptosis23. At 2q12.1, the associated SNP (rs759382; PImmunochip+Repl=6.01×10−11; ORImmunochip+Repl (95% CI)=1.22 (1.15-1.29)) maps to a ~400 kb LDblock encompassing four genes (IL1RL1, IL18R1, IL18RAP and SLC9A4). IL1RL1 encodes a receptor for IL33, which promotes Th2 responses24, and the products of IL18RAP and IL18R1 form the receptor for IL18, which has multiple immunologic functions including induction of Th1 responses. Various SNPs in IL1RL1, IL18R1 and IL18RAP were associated with asthma and related traits, and the effect was attributed to IL1RL19,25,26. In addition, IL18R1 and IL18RAP variants were associated with Crohn’s disease27 and celiac disease28. Stepwise conditional regression identified evidence for three independent signals (rs759382 in SLC9A4; rs3771180 in IL1RL1, which was previously implicated in asthma29; rs10185897 in IL1RL1/IL18R1) with P<5×10−4, and showed that the recently reported variant rs1301571412 tags rs759382 (Supplementary Table 5).

Further significant associations were observed for rs16948048 at 17q21.32 (ZNF652, PImmunochip+Repl=2.92×10−9; ORImmunochip+Repl (95% CI)=1.17 (1.11-1.23)) and rs17389644 at 4q27 (IL2/IL21, PImmunochip+Repl = 1.39×10−8; ORImmunochip+Repl (95% CI)=1.19 (1.12-1.26)). ZNF652 encodes a transcriptional repressor implicated in epithelial cancers30. IL2 has pleiotropic immunoregulatory functions, in particular control of proliferation and survival of T regulatory cells31. The IL2 locus is tightly linked with IL21, and variants in IL2, its high affinity receptor IL2RA, and IL21 were associated with multiple IM diseases. None of the SNPs chosen from the major histocompatibility complex replicated. Regional association plots of the nine atopic dermatitis susceptibility loci in Europeans with GWS are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. The four newly associated loci collectively increase the explained heritability from 9% to 14.4% (Supplementary Table 6).

To further determine the impact of the new susceptibility loci identified in Europeans on atopic dermatitis risk in diverse populations, we tested these for association in 2,397 adult Japanese cases and 7,937 controls from a recent GWAS12, and 2,848 adult Chinese cases and 2,944 controls (panel D in Supplementary Table 1). In the Japanese all new loci except IL2/IL21 and in the Chinese two loci (CLEC16A, TNFRSF6B) passed the Bonferroni-corrected significance threshold (P<0.05/6=0.008) for replication (Table 2, Supplementary Table 4). Thus, CLEC16A and TNFRSF6B appear to be relevant to the atopic dermatitis in both these European and Asian populations, while results for the other loci might reflect phenotypic and ancestry differences between the studies.

Table 2. Susceptibility loci associated with atopic dermatitis in Japanese and Chinese replication case-control studies.

| Key genes (+N additional in locus) |

Immunochip+Replication Europeans (4,376/10,048) |

Replication Japan (2,397/7,937) |

Replication China (2,848 /2,944) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr | Association boundaries (kb) |

dbSNP id | A1 | A2 | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | P | OR (95% CI) | |

|

(a) Previously reported atopic dermatitis susceptibility loci

*

| |||||||||||

| 1q21.3 | 150803-151051 | rs72702813 | T | G | LCE3A (15) | 1.49×10−33 | 2.06(1.83-2.31) | - | - | 0.3261 | 1(0-∞) |

| 2q12.1 | 102225-102619 | rs759382 | C | A | SLC9A4 (5) | 6.01×10−11 | 1.22(1.15-1.29) | 1.36×10−9 | 1.22(1.15-1.30) | 0.4540 | 0.97(0.90-1.05) |

| 5q31.1 | 131812-132167 | rs848 | T | G | IL13 (8) | 8.22×10−28 | 1.40(1.32-1.49) | 5.14×10−10 | 1.24(1.16-1.33) | 1.28×10−6 | 1.21(1.12-1.31) |

| 11q13.5 | 75724-76017 | rs7110818 | A | G | C11orf30 (1) | 3.33×10−16 | 1.28(1.21-1.36) | 6.34×10−6 | 1.16(1.09-1.24) | 0.0320 | 1.08(1.01-1.17) |

| 20q13.33 | 61678-61872 | rs909341 | A | G | TNFRSF6B (8) | 7.77×10−16 | 0.77(0.72-0.82) | 7.74×10−4 | 0.83(0.84-0.95) | 1.52×10−7 | 0.82(0.76-0.88) |

|

| |||||||||||

|

(b) New atopic dermatitis susceptibility loci

| |||||||||||

| 4q27 | 123204-123784 | rs17389644 | A | G | IL2/IL21 (2) | 1.39×10−8 | 1.19(1.12-1.26) | 0.2492 | 1.06(0.96 −1.18) | 0.1599 | 1.08(0.97-1.21) |

| 11p13 | 36355-36438 | rs12295535 | A | G | PRR5L | 7.96×10−13 | 1.68(1.46-1.93) | 0.0074 | 1.31 (1.08-1.60) | 0.1588 | 1.13(0.95-1.34) |

| 16p13.13 | 10930-11218 | rs2041733 | A | G | CLEC16A/DEXI | 3.44×10−15 | 1.23(1.17-1.29) | 0.0063 | 1.09(1.03-1.18) | 1.23×10−4 | 1.18(1.08-1.28) |

| 17q21.32 | 44641-44875 | rs16948048 | G | A | ZNF652 (5) | 2.92×10−9 | 1.17(1.11-1.23) | 1.87×10−5 | 1.22(1.12-1.34) | 0.04224 | 1.10(1.00-1.20) |

We replicated the association at the 20q13.33/TNFRSF6B and the 2q12.1/SLCA4 locus, previously reported in Chinese and Japanese populations, respectively, with GWS in Europeans. Two other known atopic dermatitis loci in Europeans from previous GWAS (OVOL1, ACTL9) are sparsely covered on the Immunochip (see also main text and Supplementary Fig. 1). Chr: chromosome of marker; Association boundaries: association boundaries for each index SNP (Online Methods). Genomic positions were retrieved from NCBI’s dbSNP build v130 (genome build hg18); dbSNP id: rs ID; A1: minor allele; A2: major allele; Key gene(s): candidate gene(s) in the region; P/OR: P-value and corresponding odds ratio and 95% confidence interval with respect to minor allele. For each panel, numbers of atopic dermatitis cases/controls are displayed in parentheses. rs72702813 failed replication genotyping in the Japanese study due to technical reasons.

Since atopic dermatitis is often co-expressed with asthma, in order to enhance interpretation of our findings we analyzed our own and Immunochip data from an independent set of 733 German asthma cases32 and 2,503 controls for atopic dermatitis, asthma, ‘atopic dermatitis no asthma’ and ‘asthma no atopic dermatitis’. We found that all of the newly susceptibility loci are primarily associated to atopic dermatitis (Supplementary Table 7).

For the nine loci associated at GWS (Table 1), we identified seven coding SNPs highly correlated (r2>0.9 in 1000 Genomes Project European samples) with the lead SNPs (Supplementary Table 8). However, these nonsynonymous SNPs are predicted in-silico to have a non-damaging effect on protein products.

Analysis of whole blood samples from 740 German control individuals identified evidence for correlation between expression of IL1RL1, ARAP3, MAP3K11 and STMN3 and SNP alleles in high LD (r2>0.95) with the most strongly associated SNPs from Table 1 (Supplementary Table 9). Examination of expression levels in skin biopsies from 64 healthy controls run on HU133 Plus 2.0 arrays33 yielded no evidence for cis-regulatory effects (Supplementary Table 10). However, a regulatory effect in another physiological state (e.g. atopic dermatitis) cannot be ruled out.

We looked for statistical interactions (allelic by allelic epistasis) between lead SNPs of each locus shown in Table 1 (Supplementary Table 11). One SNP pair (rs848/Il13 and rs2041733/CLEC16A) showed evidence for interaction (P=5.41×10−4) after Bonferroni correction (P<0.05/36=1.39×10−3). Rs848 is in tight LD with the functional IL13 variant rs20541 (r2=0.979), which impacts the activation of the signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) signaling pathway34. CLEC16A is thought to act through its ITAM, the ligation of which modulates Jak-STAT signaling35. Thus, the observed interactions reflect potential functional links, which need further investigation.

In summary, our dense genotyping approach using the Immunochip array identified four new atopic dermatitis risk loci in Europeans (Table 1b), which add 5.4% to the estimate of atopic dermatitis heritability explained, bringing the total to 14.4% explained by currently reported susceptibility loci. Our results expand the catalog of genetic loci implicated in atopic dermatitis, and provide evidence for a substantial contribution of loci shared with other immune-mediated diseases.

Online Methods

Study subjects

Immunochip data

All German atopic dermatitis cases (panel A in Supplementary Table 1) were recruited from tertiary dermatology clinics based at four centres (Technische Universität Munich, as part of the GENEVA study, University of Kiel, University of Bonn, and University Children’s Hospital, Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin, as part of the GENUFAD study). Atopic dermatitis was diagnosed on the basis of a skin examination by experienced dermatologists according to standard criteria, which included the presence of chronic or chronically relapsing pruritic dermatitis with the typical morphology and distribution36. 2,461 German controls were obtained from the PopGen biorepository37. 1,545 atopic dermatitis cases and all 2,461 PopGen controls were genotyped at the Institute of Clinical Molecular Biology, Christian-Albrechts-University of Kiel. 880 atopic dermatitis cases were genotyped at the Max-Delbrück-Centrum (MDC) for Molecular Medicine (Berlin-Buch, Germany). 979 German controls were selected as part of an independent population-based sample from the general population living in the region of Augsburg (KORA), southern Germany38, and were genotyped at the Helmholtz Center in Munich. 302 control individuals were of South German origin and part of the control population of the Munich recruited from the Bavarian Red Cross; 208 control individuals were recruited from the Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin. These samples were genotyped at the University of Pittsburgh Genomics and Proteomics Core Laboratories (PI: RH Duerr). The Bonn controls (HNR, n=1,499) were recruited from the population-based epidemiological Heinz Nixdorf Recall study39 and genotyped at the Life and Brain Center at the University Clinic in Bonn. 33.1% and 31.0% of the atopic dermatitis cases used for the screen with available phenotype information suffered from comorbid asthma.

For in silico analysis of selected SNPs for asthma, Immunochip data from 733 German asthma cases from the MAGICS and German ISAAC studies9 as well as 2,503 PopGen controls were used.

Replication data

For follow-up genotyping (panel B in Supplementary Table 1), we used 794 cases recruited at tertiary dermatology clinics in Munich, Bonn, Kiel and Hannover (Technische Universität Munich, as part of the GENEVA study, University of Bonn, University of Kiel, and Medizinische Hochschule of Hannover). 2,412 German control individuals were selected as part of the EMIL-study, an independent population-based sample from the general population living in Leukirch, southern Germany40. 926 German control individuals were selected as part of an independent population-based sample from the general population living in the region of Augsburg (KORA), southern Germany38, and were genotyped at the Helmholtz Center in Munich. The Irish case-control collection consisted of 1,157 unrelated children of self-reported Irish ancestry with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis recruited from the tertiary referral pediatric dermatology clinic based at Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital, Dublin (panel C in Supplementary Table 1). A total of 1,261 unselected control samples were obtained from the population-based Trinity Biobank Control samples. For further replication a total of 2,397 Japanese cases and 7,937 Japanese controls were analysed (panel D in Supplementary Table 1). Cases were recruited from several medical institutes including the Fukujuji Hospital, Iizuka Hospital, Juntendo University, Hospital Iwate Medical University School of Medicine, National Hospital Organization Osaka National Hospital, Nihon University, Nippon Medical School, Shiga University of Medical Science, Cancer Institute Hospital of the Japanese Foundation for Cancer Research, Tokushukai Hospital and Tokyo Metropolitan Geriatric Hospital41. Controls included 6,018 cases with one of five diseases (cerebral aneurysm, esophageal cancer, endometrial cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and glaucoma) who did not have atopic dermatitis and bronchial asthma in BioBank Japan, 1,018 healthy volunteers from members of the Rotary Club of Osaka-Midosuji District 2660 Rotary International in Japan, and 901 healthy subjects from the PharmaSNP Consortium. 2,848 Chinese Han atopic dermatitis cases and 2,944 Chinese Han control samples (panel D in Supplementary Table 1) were provided by Sen Yang and Xuejun Zhang.

Written, informed consent was obtained from all study participants and the institutional ethical review committees of the participating centers approved all protocols.

Immunochip genotyping

DNA samples were genotyped using the Immunochip, an Illumina iSelect HD custom genotyping array. The Immunochip is a BeadChip developed for highly multiplexed SNP genotyping of complex DNA. Data were analyzed using Illumina’s GenomeStudio Genotyping Module. The NCBI build 36 (hg18) map was used (Illumina manifest file Immuno_BeadChip_11419691_B.bpm) and normalized probe intensities were extracted for all samples passing standard laboratory QC thresholds.

Immunochip genotype calling and quality control

Genotype calling was performed with the GenomeStudio GenTrain 2.0 algorithm (Illumina’s GenomeStudio data analysis software) and the custom generated cluster file of Trynka et al. (based on an initial clustering of 2,000 UK samples and subsequent manual readjustment of cluster positions)13.

SNPs that had >5% missing data, a minor allele frequency <1% or deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (exact P<10−4 in controls) per sample study were excluded using the PLINK software version 1.0742. Sample quality control measures included sample call rate, overall heterozygosity, relatedness testing and other metrics (Supplementary Fig. 5-7). The remaining 2,425 atopic dermatitis cases and 5,449 controls were tested for population stratification using the principal components stratification method, as implemented in EIGENSTRAT43. Principal component analysis revealed no population stratification in the remaining samples; no population outliers were detected. 128,830 polymorphic SNPs were available for analysis. A quantile-quantile (Q-Q) plot of the full association analysis showed a marked excess of significant associations in the tail of the distribution (Supplementary Fig. 8a), which is primarily due to hundreds of highly significant association signals from a few associated (fine-mapped) regions. A Q-Q plot using 2,714 “null”-SNPs not associated with autoimmune disease (Bipolar disease)13 is shown as negative control and the inflation factor inferred showed only modest inflation (λ = 1.01; Supplementary Fig. 8b).

Replication genotyping

For replication genotpying, we selected the most strongly associated SNP (n=34) with P<10−4 from each associated locus by means of PLINK’s clumping procedure (using default settings; P1<0.0001, P2<0.01, r2≥0.5, kb=250) representing 23 loci (see also Supplementary Table 4). Follow-up replication genotyping in the Germans was carried out using our Sequenom® iPlex platform from Sequenom and TaqMan® technology from Applied Biosystems. Replication typing in the Irish case-control collection was done using TaqMan® technology from Applied Biosystems. Quality control was done for each country population separately. Individuals with >8% missing data were removed. SNPs that had >3% missing data or deviated from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (exact P<0.01 in controls) per sample population were excluded. P values for allele-based tests of phenotypic association for each single replication population were calculated using R 2.14.244. PLINK’s meta-analysis function was used to obtain P values for the replication dataset (PRepl) (panel B and C in Supplementary Table 1) and for the combined discovery-replication dataset (PImmunochip+Repl) (panel A-C in Supplementary Table 1). We used the commonly accepted threshold of 5×10−8 for joint P values to define statistical significance.

The Japanese replication set was typed using multiplex-PCR based Invader assay (Third Wave Technologies). Genotyping in the Chinese replication cohort was carried out using Sequenom® technology.

Annotation of association boundaries

Linkage disequilibrium regions (association boundaries) around focal SNPs were defined by extending in both directions a distance of 0.1 centimorgans (cM) or until another SNP with P<10−5 was reached, in which case the process was repeated from this SNP. For each locus, candidate genes within regions are listed in column “Key gene(s)” and are listed in detail in Supplementary Table 4.

Annotation of associations to other phenotypes

Overlaps with other phenotypes was annotated with the NHGRI GWAS catalogue45 (www.genome.gov/gwastudies, date of access Dec-19-2012). All known associations with P<5×10−8 to any disease or primary phenotype were included. For each atopic dermatitis susceptibility locus with association boundaries defined in Table 1 we annotated all phenotypes that had at least one associated SNP within the region. We also checked whether the hit SNP in the NHGRI GWAS catalogue was the same as, or in high LD with (r2>0.9) the atopic dermatitis hit SNP.

Stepwise conditional logistic regression and joint analysis

Multiple associated SNPs were selected through a stepwise selection procedure using GCTA (Genome-wide Complex Trait Analysis)46 using SNP markers at 2q12.1 and a threshold P value of 5×10−4 to declare evidence for independently associated SNPs (--massoc-p 5e-4) (Supplementary Table 5a).

eQTL look up

We analyzed gene expression data previously measured in whole blood (fasting conditions) and skin specimen. For analysis of whole blood we used Illumina Human HT-12 v3 Expression BeadChip data from 740 adult individuals of the German population-based KORA (Cooperative Heath Research in the Region of Augsburg) F4 study performed 2006-200847 (Supplementary Table 9). For analysis of skin, we used Affymetrix HU133 Plus 2.0 arrays data from 57 healthy individuals33 (Supplementary Table 10).

Statistical interaction analysis

To look for interactions between associated loci, we considered all distinct pairs (n=36) of the nine lead SNPs listed in Table 1 (see Supplementary Table 11).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical staining of paraffin-embedded tissue of 8 biopsies taken from lesions of atopic dermatitis patients compared to 8 healthy sex and age matched control persons was done by using monoclonal mouse anti-DcR3 antibody (see Supplementary Figure 3).

Serum measurements

Analysis of DcR3 serum levels has been done using Duo set ELISA development system from R&Dsystems, Wiesbaden, Germany according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all individuals with atopic dermatitis, their families, control individuals and clinicians for their participation. We wish to thank Tanja Wesse, Tanja Henke, Sanaz Sedghpour Sabet, Sandra Greve, Ilona Urbach, Giannino Patone, Christina Flachmeier, Susanne Kolberg and Gabriele Born for expert technical help. The study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), grant no. FR 2821/2-1, the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) through the National Genome Research Network (NGFN, 01GS 0818, 01GS 0812) and the PopGen biobank. Stephan Weidinger is supported by a Heisenberg fellowship of the DFG (WE 2678/7-1). The project received infrastructure support through the DFG Clusters of Excellence “Inflammation at Interfaces”. Alan Irvine is supported by the National Children’s Research Centre, Dublin. Alan Irvine and Irwin McLean are supported by the Wellcome Trust [reference: 090066/B/09/Z, 092530/Z/10/Z]. Stephan Brand is supported by the DFG grant BR1912/6-1 and by the Else-Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (stipend 2010_EKES.32). We acknowledge the National Institutes of Health grant 1R01CA141743-01 (PI: Richard H. Duerr), the University of Pittsburgh Genomics and Proteomics Core Laboratories for the Immunochip genotyping services. This work was supported by a Wellcome Trust Programme and Bioresources Grants (090066/B/09/Z and 092530/Z/10/Z) to W.H.I.M. and A.D.I., and a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award (098439/Z/12/Z) to W.H.I.M. Parts of the study were funded by the General Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (31171224), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-11-0889), Science and Technological Foundation of Anhui Province for Outstanding Youth (1108085J10) and a pre-project of State Key Basic Research Program 973 of China (No. 2012CB722404).

Footnotes

URLs: PopGen biobank, http://www.popgen.de

Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Bieber T. Atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1483–94. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra074081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang TS, Bieber T, Williams HC. Does “autoreactivity” play a role in atopic dermatitis? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1209–1215. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer CN, et al. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2006;38:441–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhernakova A, van Diemen CC, Wijmenga C. Detecting shared pathogenesis from the shared genetics of immune-related diseases. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:43–55. doi: 10.1038/nrg2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esparza-Gordillo J, et al. A common variant on chromosome 11q13 is associated with atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:596–601. doi: 10.1038/ng.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paternoster L, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies three new risk loci for atopic dermatitis. Nat Genet. 2011;44:187–192. doi: 10.1038/ng.1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marenholz I, et al. The eczema risk variant on chromosome 11q13 (rs7927894) in the population-based ALSPAC cohort: a novel susceptibility factor for asthma and hay fever. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:2443–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrett JC, et al. Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn’s disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:955–62. doi: 10.1038/NG.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moffatt MF, et al. A large-scale, consortium-based genomewide association study of asthma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1211–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, et al. The 5q31 variants associated with psoriasis and Crohn’s disease are distinct. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2978–85. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun LD, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies two new susceptibility loci for atopic dermatitis in the Chinese Han population. Nat Genet. 2011;43:690–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirota T, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies eight new susceptibility loci for atopic dermatitis in the Japanese population. Nat Genet. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ng.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trynka G, et al. Dense genotyping identifies and localizes multiple common and rare variant association signals in celiac disease. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1193–201. doi: 10.1038/ng.998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Cid R, et al. Deletion of the late cornified envelope LCE3B and LCE3C genes as a susceptibility factor for psoriasis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:211–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Koning HD, et al. Expression profile of cornified envelope structural proteins and keratinocyte differentiation-regulating proteins during skin barrier repair. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:1245–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hsu TL, et al. Modulation of dendritic cell differentiation and maturation by decoy receptor 3. J Immunol. 2002;168:4846–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.4846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kugathasan S, et al. Loci on 20q13 and 21q22 are associated with pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1211–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bamias G, et al. Upregulation and nuclear localization of TNF-like cytokine 1A (TL1A) and its receptors DR3 and DcR3 in psoriatic skin lesions. Exp Dermatol. 2011;20:725–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Todd JA, et al. Robust associations of four new chromosome regions from genome-wide analyses of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:857–64. doi: 10.1038/ng2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hakonarson H, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies KIAA0350 as a type 1 diabetes gene. Nature. 2007;448:591–4. doi: 10.1038/nature06010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(ANZgene), A.a.N.Z.M.S.G.C Genome-wide association study identifies new multiple sclerosis susceptibility loci on chromosomes 12 and 20. Nat Genet. 2009;41:824–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jagielska D, et al. Follow-Up Study of the First Genome-Wide Association Scan in Alopecia Areata: IL13 and KIAA0350 as Susceptibility Loci Supported with Genome-Wide Significance. J Invest Dermatol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gan X, et al. PRR5L degradation promotes mTORC2-mediated PKC-delta phosphorylation and cell migration downstream of Galpha(12) Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:686–96. doi: 10.1038/ncb2507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Palmer G, Gabay C. Interleukin-33 biology with potential insights into human diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:321–9. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2011.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gudbjartsson DF, et al. Sequence variants affecting eosinophil numbers associate with asthma and myocardial infarction. Nat Genet. 2009;41:342–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Savenije OE, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor-like 1 polymorphisms are associated with serum IL1RL1-a, eosinophils, and asthma in childhood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:750–6. e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franke A, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn’s disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42:1118–25. doi: 10.1038/ng.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunt KA, et al. Newly identified genetic risk variants for celiac disease related to the immune response. Nat Genet. 2008;40:395–402. doi: 10.1038/ng.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Torgerson DG, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of asthma in ethnically diverse North American populations. Nat Genet. 2011;43:887–92. doi: 10.1038/ng.888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar R, et al. Genome-wide mapping of ZNF652 promoter binding sites in breast cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:2742–7. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyman O, Sprent J. The role of interleukin-2 during homeostasis and activation of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12:180–90. doi: 10.1038/nri3156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeilinger S, et al. The effect of BDNF gene variants on asthma in German children. Allergy. 2009;64:1790–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gudjonsson JE, et al. Global gene expression analysis reveals evidence for decreased lipid biosynthesis and increased innate immunity in uninvolved psoriatic skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129:2795–804. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vladich FD, et al. IL-13 R130Q, a common variant associated with allergy and asthma, enhances effector mechanisms essential for human allergic inflammation. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115:747–54. doi: 10.1172/JCI22818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L, et al. ‘Tuning’ of type I interferon-induced Jak-STAT1 signaling by calcium-dependent kinases in macrophages. Nature immunology. 2008;9:186–93. doi: 10.1038/ni1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams HC, et al. The U.K. Working Party’s Diagnostic Criteria for Atopic Dermatitis. I. Derivation of a minimum set of discriminators for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:383–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krawczak M, et al. PopGen: population-based recruitment of patients and controls for the analysis of complex genotype-phenotype relationships. Community Genet. 2006;9:55–61. doi: 10.1159/000090694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wichmann HE, Gieger C, Illig T. KORA-gen--resource for population genetics, controls and a broad spectrum of disease phenotypes. Gesundheitswesen. 2005;67:S26–30. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmermund A, et al. Assessment of clinically silent atherosclerotic disease and established and novel risk factors for predicting myocardial infarction and cardiac death in healthy middle-aged subjects: rationale and design of the Heinz Nixdorf RECALL Study. Risk Factors, Evaluation of Coronary Calcium and Lifestyle. Am Heart J. 2002;144:212–8. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.123579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haenle MM, et al. Overweight, physical activity, tobacco and alcohol consumption in a cross-sectional random sample of German adults. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:233. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shimizu M, et al. Functional SNPs in the distal promoter of the ST2 gene are associated with atopic dermatitis. Human molecular genetics. 2005;14:2919–27. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Price AL, et al. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–9. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.R Development Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: 2007. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hindorff LA, et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9362–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903103106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang J, et al. Conditional and joint multiple-SNP analysis of GWAS summary statistics identifies additional variants influencing complex traits. Nat Genet. 2012;44:369–75. S1–3. doi: 10.1038/ng.2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mehta D, et al. Impact of common regulatory single-nucleotide variants on gene expression profiles in whole blood. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2012 doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.