Abstract

One of the key classical pathological features of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the progressive accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ42) peptides and their coalescence into highly insoluble senile plaque cores. A major factor driving Aβ42 peptide accumulation is the inability of brain cells to effectively clear excessive amounts of Aβ42 via phagocytosis. The trans-membrane spanning, sensor-receptor known as the ‘triggering receptor expressed in myeloid cells 2′ (TREM2; chr6p21) is essential in the sensing, recognition, phagocytosis and clearance of noxious cellular debris from brain cells, including neurotoxic Aβ42 peptides. Recently, mutations in the TREM2 gene have been associated with amyloidogenesis in neurodegenerative diseases including AD. In this report, we provide evidence that aluminum-sulfate, when incubated with microglial cells, induces the up-regulation of an NF-kB-sensitive micro RNA-34a (miRNA-34a; chr1p36) that is known to target the TREM2 mRNA 3′-untranslated region (3′-UTR), significantly down-regulating TREM2 expression. The aluminum-induced up-regulation of miRNA-34a and down-regulation of TREM2 expression was effectively quenched using the natural phenolic compound and NF-kB inhibitor CAPE [2-phenylethyl-(2E)-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl) acrylate; caffeic-acid phenethyl ester]. These results suggest, for the first time, that an epigenetic mechanism involving an aluminum-triggered, NF-kB-sensitive, miRNA-34a-mediated down-regulation of TREM2 expression may impair phagocytic responses that ultimately contribute to Aβ42 peptide accumulation, aggregation, amyloidogenesis and inflammatory degeneration in the brain.

Keywords: aluminum sulfate, Alzheimer’s disease, genotoxicity, microglial cells, inflammation, magnesium sulfate, phagocytosis, TREM2

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a progressive, multi-factorial human brain disorder whose incidence is reaching epidemic proportions in industrialized societies [1]. According to the widely accepted amyloid cascade hypothesis, AD is strongly associated with the progressive accumulation of neurotoxic 42 amino acid amyloid beta (Aβ42) peptides generated from the tandem beta- and gamma-secretase-mediated cleavage of the trans-membrane beta amyloid precursor protein (βAPP) [2,3]. The Aβ42 peptides so generated are normally cleared by an active phagocytosis system that involves microglial cell-mediated Aβ42 peptide recognition and catabolism, however when this system is impaired, Aβ42 peptides progressively accumulate, and self-aggregate into insoluble senile plaque cores that support a pro-inflammatory and degenerative neuropathology [2–5]. The catabolic mechanisms by which excessive Aβ is cleared from the brain is not fully understood, but is known to involve microglial cells, the major resident scavenging cell types in the CNS [4,5]. Microglial cells normally fulfill important functions in cell-cell interactions, immune surveillance, the resolution of latent inflammatory reactions and the clearance of tissue debris [4–8]. Microglial cells highly express TREM2 (encoded at chr6p21.1) as an integral trans-membrane glycoprotein. TREM2 appears to be key in the sensing, recognition and phagocytosis of noxious cellular debris from brain cells, including neurotoxic Aβ42 peptides [8–12]. Expression deficits in TREM2 could in part explain the loss of effective, homeostatic phagocytotic functions mediated by microglial cells, the ensuing buildup of Aβ42 peptides, and a progressive, ‘smoldering’, pro-inflammatory response associated with Aβ42 accumulation, including the chronic over-production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [11,12]. Recent studies have shown that TREM2 variants are genetically linked to AD, and that TREM2 expression is under the post-transcriptional regulation by a brain enriched miRNA-34a, by virtue of a miRNA-34a recognition feature within the 299 nucleotide TREM2 mRNA 3′-UTR [11–13]. To more fully understand the effects of aluminum on AD-relevant gene expression processes, in this study we analyzed the effects of aluminum on the key phagocytosis protein TREM2 in primary murine microglial cells.

In these studies ultrapure reagents for molecular biology, including MgSO4 (63133) and Al2(SO4)3 (11044; Biochemika MicroSelect©; Fluka Ultraselect©; Fluka Chemical, Milwaukee, WI), freshly prepared as 0.1 M stock solutions, were instilled into either serum-containing or half serum strength microglial cell maintenance medium (MCMM) made up in ultrapure water (18 megohm, Milli-Q, Millipore; aluminum content less than 1 ppb), followed by filter sterilization using 0.2-μM spin filters (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA) [14,15,17]. MCMM consists of Dulbecco’s modified Eagles medium; the full medium contains 10% fetal bovine serum; also known as LADMAC conditioned medium (complete MCMM composition; see ATCC-EOC2; Manassus VA, USA). Cell media solutions contained a final concentration of 2.0 uM MgSO4 or 2.0 uM of Al2(SO4)3. Murine CB-84 (ATCC CRL-2467) microglial cells were cultured according to ATCC-EOC2 protocols; after 1 week of culture, control MCMM was replaced with MgSO4- or Al2(SO4)3-containing MCMM and cells were incubated for 8 hrs at 37°C (Fig. 1A). Details of control, magnesium- and aluminum-sulfate treatment of brain cells have been extensively described [14,16–18,20–23]. Importantly, with an MCMM pH of 6.8, the predominant form of aluminum would be as aluminum hydroxide, itself a potent mediator of the immune response [19]. Total RNA and proteins were simultaneously isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen) [20–23]; RNA quality was assessed using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Lucent Technologies/Caliper Technologies) and RNA integrity numbers (RIN) values were typically 8.0–9.0 indicating high quality total RNA [14–18]. Protein concentrations were determined using dotMETRIC microassay (sensitivity 0.3 ng protein/ml; Millipore, Billerica MA, USA) [14,17]. Western immunoblots employed antibodies to TREM2 (B3; sc-373828, H160; sc-49764 or M227; sc-48765; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz CA, USA) or the control protein marker β-actin (3598-100; Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company, St Louis, Missouri, USA) in the same sample [11,14]. CAPE (MW 284.31; 2-phenylethyl-(2E)-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl) acrylate; caffeic acid phenethyl ester) was purchased from Tocris Bioscience and used according to the manufacturer’s protocols (#2743; R&D Systems, Minneapolis MN, USA). All miRNA arrays were analyzed as previously described [11,20–23].

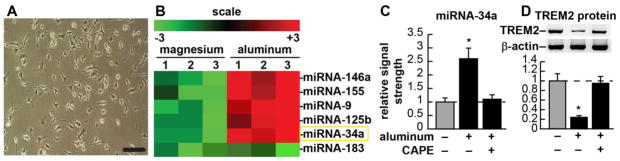

Figure 1.

(A) CB-84 (ATCC CRL-2467) murine microglial cells, 32% confluent, phase contrast microscopy; bar = 20 μm; (B) fluorescent-based miRNA array analysis results for 3 magnesium sulfate-treated and 3 aluminum-sulfate-treated experiments using CB-84 murine microglial cells [as described in (A)]; compared to 2 uM ambient magnesium, 2 uM ambient aluminum induces a small family of micro RNAs (miRNAs) in murine microglial cells; these include miRNA-9, miRNA-34a, miRNA-125b, miRNA-146a and miRNA-155 but not miRNA-183; up-regulation of these induced miRNAs has been previously shown to be NF-kB-sensitive [21–23]; microRNAs (miRNAs) are a recently discovered class of single stranded non-coding ribonucleotide regulators which, through base-pair complementarity, bind to the 3′ un-translated (3′-UTR) region of highly selective target mRNAs, and direct the post-transcriptional repression of that mRNA’s encoded genetic information [25,26] (Fig. 1B); the aluminum-mediated up-regulation of miRNA-9, miRNA-146a, miRNA-125b and miRNA-155 and their pathogenic consequences have already been reported [18,20–25,28,33,37]; miRNA-183 is a control miRNA whose levels do not change in the presence of either magnesium or aluminum in microglial or other brain cell types [11,18,22]; (C) Quantitation of fluorescent signals in (B); miRNA-34a (highlighted in a yellow rectangle) is up-regulated 2.6-fold in aluminum-sulfate-treated microglial cells (compared to magnesium sulfate-treated controls); note that treatments longer than 8 hrs with <2 uM ambient aluminum gave quantitatively similar results [23]; addition of caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE), a potent honeybee-resin (propolis)-derived NF-kB inhibitor quenched this induction, indicating the NF-kB-sensitivity of miRNA-34a expression; (D) within the same microglial cells TREM2 protein abundance is shown in comparison to an unchanging control β-actin protein abundance in the same sample; (representative protein bands, upper panel; quantified in bar format, lower panel); TREM2 is significantly down-regulated to 0.24-fold of control values; again, addition of CAPE inhibitor quenched this induction, indicating that TREM2 up-regulation is NF-kB-sensitive. An aluminum-induced reduction in TREM2 expression may therefore impair phagocytosis of Aβ42 peptides with amyloidogenic effects (see text); a dashed horizontal line at 1.0 indicates in (C) control miRNA-34a levels or (D) control TREM2 protein levels for ease of comparison; figures were generated using Adobe Photoshop v9.0 (Adobe, San Jose CA, USA); statistical procedures were analyzed using a two-way factorial analysis of variance (p, ANOVA) and the SAS language (Statistical Analysis Institute, Cary NC, USA) [11,21]. Only p-values less than 0.05 (ANOVA) were considered as statistically significant; N=5, significance over controls *p<0.05 (ANOVA).

Murine microglial cells (Fig. 1A) were stressed with either magnesium- or aluminum-sulfate, however only aluminum-sulfate generated a unique up-regulated miRNA expression profile highly characteristic of NF-kB up-regulated miRNAs (Fig. 1B) [16,18,22]. As has been previously observed, addition of magnesium sulfate to microglial cells had no significant effect on gene expression for either mRNA or miRNA (data not shown) [14,17,22,23]. On the other hand aluminum, a known strong inducer of NF-kB, triggered the expression of several miRNAs known to be pro-inflammatory and under NF-kB transcriptional control [22–24]. Because NF-kB up-regulated, pro-inflammatory miRNAs have been associated with down-regulation of the expression of Alzheimer-relevant neuroimmune genes and immunological system deficits, using miRBASE algorithms (EMBL-EBI Institute; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/enright-srv/microcosm/htdocs/targets/v5/) we systematically searched for potential miRNA-34a mRNA targets and a strong candidate was the miRNA-34a-TREM2-mRNA 3′-UTR interaction [11,22,23]. Subsequently, miRNA-34a up-regulation was found to be closely coupled to TREM-2 down-regulation in the same sample, and Western analysis indicated that TREM2 protein levels were reduced in aluminum-treated microglial cells to about 0.25-fold of controls (Fig. 1C and Fig. 1D). Both miRNA-34a up-regulation and TREM2 down-regulation was significantly quenched using the NF-kB inhibitor CAPE, indicating the involvement of NF-kB in these reactions (Fig. 1C and Fig. 1D). A family of brain-enriched miRNAs, up-regulated in AD brain, known to be under NF-kB control, are involved in the regulation of innate-immune sensing, the inflammatory response, neurotrophism, synaptogenesis and amyloidogenesis [25–28]. For example, an NF-kB-regulated miRNA subfamily including miRNA-9, miRNA-125b, miRNA-146a and miRNA-155 each target the 3′-UTR of the key, innate-immune- and inflammation-related regulatory protein CFH, resulting in significant decreases in CFH expression with subsequent stimulation of the innate immune response, and a chronic form of NF-kB activation (Fig. 1B) [22,23,29,30].

Rare missense mutations of TREM2 (R47H) or of the TREM2 coupling protein, DAP12 (also known as TYROBP) and loss-of-function for TREM2 have recently been associated with deficiencies in phagocytosis and the innate-immune system in progressive dementing illnesses including AD [5–13]. TREM2 is a stimulatory receptor of the immunoglobulin/lectin-like gene superfamily highly expressed in a subset of myeloid cells including immature dendritic cells, tissue macrophages and myeloid-derived microglia, and is an integral part of the evolutionarily ancient complement system and the innate immune response [10,12,29,30]. Signaling through TREM2 or its adaptor proteins DAP12 (TYROBP) is known to play neuroprotective roles through the clearance of noxious cellular debris from the CNS, the phagocytosis of pathogens that is accompanied by the release of reactive oxygen species and inflammatory cytokines, and the resolution of damage-associated inflammation [7–13]. We speculate that an important consequence of down-regulated TREM2 is interference with the brain’s natural ability to deal with excessive Aβ42 peptide, resulting in Aβ42 accumulation and self-aggregation into senile plaque [6,7]. Given the known anti-amyloidogenic and pro-phagocytotic roles of TREM2, loss-of-function resulting in a defective TREM2, or down-regulation of an intact, functional TREM2 may have analogous pathological effects [11].

This study is the first to show an aluminum-mediated, miRNA-modulated down-regulation of TREM2 expression, and underscores the importance of aluminum-induced miRNAs as epigenetic regulators of AD-relevant gene expression in brain immune cells [20–23,31–33]. Importantly, ~6 uM-and-higher aluminum sulfate causes microglial cell cultures to undergo apoptosis, so the 2 uM concentration used in these experiments is at a sub-apoptotic, sub-lethal concentration. It is interesting to speculate that exogenous aluminum may directly impact amyloidogenesis by at least 2 distinct and interdependent pathogenic mechanisms: (1) by facilitating Aβ42 monomers to aggregate into higher order, more compacted, amyloid-plaque structures [34], while (2) impairing the phagocytosis mechanism and the clearance of Aβ42 peptides and other neurotoxic end-products from the brain, thus driving their accumulation. Further studies are required (1) to evaluate what forms of Aβ peptide (monomer, dimer, oligomer) are phagocytosed by TREM2; (2) to test the involvement of other TREM2-associated membrane proteins such as DAP12 (TYROBP) in the phagocytosis process; and (3) to evaluate the utility of aluminum chelation, anti-NF-kB or anti-miRNA-34a therapeutic strategies to potentially reverse these ‘anti-phagocytic’ and ‘amyloidogenic’ effects [35–37].

Highlights.

cultured murine microglial cells express the trans-membrane sensor-receptor known as the ‘triggering receptor expressed in myeloid cells 2′ (TREM2; chr6p21);

TREM2 is normally essential in the sensing, recognition, phagocytosis and clearance of noxious cellular debris from brain cells, including neurotoxic Aβ42 peptides;

aluminum (sulfate) up-regulation of an NF-kB-sensitive miRNA-34a and down-regulation in the expression of TREM2 may impair Aβ42 peptide clearance;

impaired Aβ42 peptide clearance may result in progressive amyloidosis and inflammatory neurodegeneration.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are extended to Drs. C. Eicken, P. Dua and C. Hebel for miRNA array work and initial data interpretation, and to D. Guillot and A.I. Pogue for expert technical assistance. Research on miRNA in the Lukiw laboratory involving metal neurotoxicity, the innate-immune response in AD, amyloidogenesis and neuro-inflammation was supported through an Alzheimer Association Investigator-Initiated Research Grant IIRG-09-131729 and NIH NIA Grants AG18031 and AG038834.

Abbreviations

- 3′-UTR

3′-untranslated region (of a mature mRNA)

- Aβ42

a 42 amino acid amyloid beta peptide (neurotoxic in high concentrations)

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- Al2(SO4)3

aluminum sulfate

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- ATCC

American tissue culture collection

- CAPE

2-phenylethyl-(2E)-3-(3,4-dihydroxyphenyl) acrylate (caffeic-acid phenethyl ester)

- CNS

central nervous system

- MCMM

microglial cell maintenance medium

- MgSO4

magnesium sulfate

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- NF-kB

nuclear factor for kappa B

- miRNA

micro RNA

- miRNA-34a

micro RNA type 34a, a pro-inflammatory NF-kB-regulated miRNA

- TREM2

triggering receptor expressed in myeloid cells 2

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.http://www.alz.org/downloads/facts_figures2012.pdf.

- 2.Hardy J. J Neurochem. 2009;110:1129–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tiiman A, Palumaa P, Tõugu V. Neurochem Int 2013. 2013;62:367–378. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boche D, VH, Nicoll JA. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2013;39:3–18. doi: 10.1111/nan.12011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aguzzi A, Barres BA, Bennett ML. Science. 2013;339:156–161. doi: 10.1126/science.1227901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmid CD, Sautkulis LN, Danielson PE, Cooper J, Hasel KW, Hilbush BS, Sutcliffe JG, Carson MJ. J Neurochem. 2002;83:1309–1320. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01243.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F. Helmchen Science. 2005;308:1314–1318. doi: 10.1126/science.1110647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saijo K, Crotti A, Glass CK. Glia. 2013;61:104–11. doi: 10.1002/glia.22423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neumann H, Takahashi K. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;184:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melchior B, Garcia AE, Hsiung BK, Lo KM, Doose JM, Thrash JC, Stalder AK, Staufenbiel M, Neumann H, Carson MJ. ASN Neuro. 2010;2:e00037. doi: 10.1042/AN20100010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao Y, Bhattacharjee S, Jones BMM, Dua P, Alexandrov PN, Hill JM, Lukiw WJ. Neuroreport. 2013;24:318–323. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32835fb6b0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jiang T, Yu JT, Zhu XC, Tan L. Mol Neurobiol. 2013 Feb 14; [Epub ahead of print] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guerreiro R, Wojtas A, Bras J, Carrasquillo M, Rogaeva E, Majounie E, Cruchaga C, Sassi C, Kauwe JS, Younkin S, Hazrati L, Collinge J, Pocock J, Lashley T, Williams J, Lambert JC, Amouyel P, Goate A, Rademakers R, Morgan K, Powell J, St George-Hyslop P, Singleton A, Hardy J Alzheimer Genetic Analysis Group. N Engl J Med. 2012;368:117–127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alexandrov PN, Zhao Y, Pogue AI, Tarr MA, Kruck TPA, Percy ME, Cui JG, Lukiw WJ. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2005;8:117–127. doi: 10.3233/jad-2005-8204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lukiw WJ, LeBlanc HJ, Carver LA, McLachlan DRC, Bazan NG. J Molec Neurosci. 1998;11:67–78. doi: 10.1385/JMN:11:1:67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pogue AI, Jones BM, Bhattacharjee S, Percy ME, Zhao Y, Lukiw WJ. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:9615–9626. doi: 10.3390/ijms13089615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lukiw WJ, Bhattacharjee S, Dua P, Alexandrov PN. Int J Biochem Molec Biol. 2012;3:105–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lukiw WJ, Zhao Y, Cui JG. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31315–31322. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805371200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vera-Lastra O, Medina G, Cruz-Dominguez P, Jara LJ, Shoenfeld Y. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2013;9:361–373. doi: 10.1586/eci.13.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cui JG, Li YY, Zhao Y, Bhattacharjee S, Lukiw WJ. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:38951–38960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.178848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li YY, Cui JG, Dua P, Pogue AI, Bhattacharjee S, Lukiw WJ. Neurosci Lett. 2011;499:109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lukiw WJ. Exp Neurol. 2012;235:484–490. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pogue AI, Percy ME, Cui JG, Li YY, Bhattacharjee S, Hill JM, Kruck TPA, Zhao Y, Lukiw WJ. J Inorg Biochem. 2011;105:1434–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iyer A, Zurolo E, Prabowo A, Fluiter K, Spliet WG, van Rijen PC, Gorter JA, Aronica E. PLoS One. 2012;7:e44789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soreq H, Wolf Y. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonkoly E, Ståhle M, Pivarcsi A. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qin B, Yang H, Xiao B. Mol Biol Rep. 2012;39:4509–4518. doi: 10.1007/s11033-011-1241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lukiw WJ, Andreeva TV, Grigorenko AP, Rogaev EI. Front Genet. 2013;3:27–36. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saijo K, Crotti A, Glass CK. Glia. 2013;61:104–111. doi: 10.1002/glia.22423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aiyaz M, Lupton MK, Proitsi P, Powell JF, Lovestone S. Immunobiology. 2012;217:204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lukiw WJ. Neuroreport. 2007;18:297–300. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3280148e8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veremeyko T, Starossom SC, Weiner HL, Ponomarev ED. J Vis Exp. 2012;65:4097–4103. doi: 10.3791/4097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lukiw WJ, Alexandrov PN. Mol Neurobiol. 2012;46:11–19. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8234-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Exley C. Subcell Biochem. 2005;38:225–234. doi: 10.1007/0-387-23226-5_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Percy ME, Kruck TPA, Pogue AI, Lukiw WJ. J Inorg Biochem. 2011;105:1505–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lukiw WJ. Front Physiol. 2013;4:24. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00024. Epub 2013 Feb 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lukiw WJ. Front Genetics. 2013;4:77. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00077. Epub 2013 May 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]