Abstract

Free fatty acids (FFAs) are metabolic intermediates that may be obtained through the diet, synthesized endogenously, or produced via fermentation of carbohydrates by gut microbiota. In addition to serving as an important source of energy, FFAs are known to produce a variety of both beneficial and detrimental effects on metabolic and inflammatory processes. While historically, FFAs were believed to produce these effects only through intracellular targets such as peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, it has now become clear that FFAs are also agonists for several GPCRs, including a family of four receptors now termed FFA1-4. Increasing evidence suggests that FFA1-4 mediate many of the beneficial properties of FFAs and not surprisingly, this has generated significant interest in the potential of these receptors as therapeutic targets for the treatment of a variety of metabolic and inflammatory disorders. In addition to the traditional strategy of developing small-molecule therapeutics targeting these receptors, there has also been some consideration given to alternate therapeutic approaches, specifically by manipulating endogenous FFA concentrations through alteration of either dietary intake, or production by gut microbiota. In this review, the current state of knowledge for FFA1-4 will be discussed, together with their potential as therapeutic targets in the treatment of metabolic and inflammatory disorders. In particular, the evidence in support of small molecule versus dietary and microbiota-based therapeutic approaches will be considered to provide insight into the development of novel multifaceted strategies targeting the FFA receptors for the treatment of metabolic and inflammatory disorders.

Keywords: free fatty acid, free fatty acid receptor, metabolism, inflammation, glucose homeostasis, therapeutics, diet, gut microbiota

Fatty acids (FAs) are nutritional components and metabolic intermediates that play important roles in a wide range of cellular functions. These include serving as an important energy substrate, as a building material for cellular membranes, and as signalling molecules (Kremmyda et al., 2011; Tvrzicka et al., 2011). FAs are carboxylic acids with an unbranched aliphatic tail and are classified based on chain length as well as degree and pattern of unsaturation. Long-chain FAs (LCFAs) are FAs containing more than 12 carbon atoms, medium-chain FAs (MCFAs) contain 6–12 carbon atoms, while short-chain FAs (SCFAs) possess less than 6 carbons (Ratnayake and Galli, 2009; Tvrzicka et al., 2011). The biological sources by which we obtain the different types of FAs also varies greatly. LCFAs and MCFAs are typically derived from the diet, or through adipose recycling and hepatic turnover of neutral fats, cholesterol esters, and phospholipids (Tvrzicka et al., 2011). In contrast, the primary source of SCFAs is from the bacterial fermentation of indigestible dietary carbohydrates and polysaccharides by anaerobic gut bacteria in the lower intestine (Macfarlane and Macfarlane, 2011). Following ingestion and/or generation LCFAs readily bind plasma albumin or may be incorporated through ester linkages into phospholipids, triglycerides or other lipids. Based on this, a FA is described as a free FA when present in the unbound form.

Historically, FAs were believed to produce their physiological actions primarily through intracellular targets, including actions at the PPARs for LCFAs (Grimaldi, 2010; Varga et al., 2011) and inhibitor effects on histone deacetylase (HDACs) for SCFAs (Sealy and Chalkley, 1978; Waldecker et al., 2008). Additionally, incorporation of specific FAs into phospholipid may account for some of their biological properties, as changes in membrane FA composition has been demonstrated to influence the physical properties of cell membranes, as well as cell signalling pathways (Calder, 2004). However, in recent years it has become clear that FFAs are also agonists for a group of cell-surface GPCRs. These include the family of GPCRs now classified as the free FA 1-4 (FFA1–4) receptor family (Stoddart et al., 2008; Alexander et al., 2011; Davenport et al., 2013), as well as one additional receptor currently still classified as an orphan, GPR84 (Wang et al., 2006). Although the importance and relevance of FFAs as ligands at GPR84 remains largely unknown, growing evidence suggests that FFAs do produce many of their beneficial effects on both metabolic and inflammatory processes through actions at the members of FFA family of receptors. This has led to growing interest in these receptors as novel therapeutic targets. Although this interest does include traditional small-molecule drug development programmes, because FFA receptor function may also be manipulated by modification of FFA levels through diet or gut microbiota composition, alternative therapeutic approaches are also being explored. The current review examines the role of the FFA family members in metabolic and inflammatory processes and considers advantages and disadvantages of various therapeutic strategies that may be developed to target this family of receptors.

Discovery and characterization of the FFA family

Of the four members of the FFA receptor family, three, FFA1, FFA2 and FFA3 (previously known as GPR40, GPR43 and GPR41, respectively) were first identified in 1997 as a group of closely related putative GPCRs encoded in tandem on chromosome 19q13.1 (Sawzdargo et al., 1997). These receptors were subsequently deorphanized as receptors for FFAs in 2003 using high-throughput screening approaches (Briscoe et al., 2003; Brown et al., 2003; Itoh et al., 2003; Kotarsky et al., 2003b; Nilsson et al., 2003). The fourth member of the family, previously known as GPR120, does not share homology with the other family members. However, GPR120 was also identified through high-throughput screening as a receptor for FFAs (Hirasawa et al., 2005), and therefore despite its lack of homology with the other family members, GPR120 was recently reclassified as FFA4 (Davenport et al., 2013).

Several key differences exist among the FFA family members with respect to ligand specificity. FFA1 and FFA4 are each activated by LCFAs of varying chain length and degree of saturation (Briscoe et al., 2003; Itoh et al., 2003; Kotarsky et al., 2003a). Of particular interest, FFA4 has at times been described as a selective n-3 FA sensor (Oh et al., 2010), although it must be noted both that n-3 FAs are also agonists with similar potency at FFA1, and that many non n-3 FAs are equally active at FFA4. Indeed, examination of the currently available data on the potency of various LCFAs at FFA1 and FFA4 (Briscoe et al., 2003; Itoh et al., 2003; Kotarsky et al., 2003a; Hirasawa et al., 2005) yields no clear consensus of a particular subgroup of LCFAs that reasonably could be deemed selective for one receptor over the other. In contrast to these LCFA receptors, FFA2 and FFA3 are activated only by the various SCFAs, although with differing rank–order of potencies between the two receptors (Brown et al., 2003; Nilsson et al., 2003). Most notably, at least for the human orthologues, acetate (C2) is significantly more potent at FFA2 than FFA3 (Hudson et al., 2012b). Interestingly, the potencies of the various FA ligands are relatively low at all four members of the family (Table 1), which initially led to some debate as to whether these were in fact the endogenous ligands for these receptors (Smith, 2012). However, the ligand potencies observed for each receptor are either at or below the physiological levels of these FAs in the body (Table 1), supporting the conclusion that FFAs are indeed the endogenous ligands of these receptors. Interestingly, in the case of FFA1 and FFA4 the serum concentrations of LCFAs are actually substantially higher than the reported potency of these ligands and presumably this reflects the fact that LCFAs in the body will be predominantly bound to serum albumin, which has been shown to reduce their ability to activate the FFA receptors (Itoh et al., 2003).

Table 1.

Comparison of FFA receptor endogenous ligand potency and reported physiological concentrations

| Receptor | Endogenous ligands | Endogenous ligand potency (EC50)a | Physiological levels of endogenous ligandsb |

|---|---|---|---|

| FFA1 | LCFAs | 1.0–30 μM | Serum- 200–500 μMc |

| FFA4 | |||

| FFA2 | SCFAs | 0.1–1.0 mM | Gut- 70–100 mM Serum- 50–200 μM |

| FFA3 |

Potency ranges reported for endogenous ligands at LCFA or SCFA receptors (Briscoe et al., 2003; Brown et al., 2003; Itoh et al., 2003; Kotarsky et al., 2003b; Nilsson et al., 2003; Hirasawa et al., 2005).

Total LCFA or SCFA levels reported in human (Cook and Shellin, 1998; Jouven et al., 2001; Pouteau et al., 2001; van Eijk et al., 2009; Wagner et al., 2013).

Total concentration of nonesterified fatty acids does not account for the effect of serum albumin binding.

FFA1-4 each exhibit distinct downstream signalling profiles (Table 2). Collectively, the FFA receptors have been demonstrated to couple to Gαq/11 (FFA1, FFA2 and FFA4) and/or Gαi/o (FFA2 and FFA3) G-proteins, increasing intracellular Ca2+ levels and inhibiting cAMP generation, respectively (Briscoe et al., 2003; Brown et al., 2003; Itoh et al., 2003; Kotarsky et al., 2003a; Le Poul et al., 2003; Nilsson et al., 2003; Yonezawa et al., 2004; Katsuma et al., 2005; Hirasawa et al., 2008; Watson et al., 2012). Less is known about G–protein-independent signalling effects of these receptors, although β-arrestin-2 recruitment has been reported for FFA1 (Shimpukade et al., 2012), FFA2 (Hudson et al., 2012a) and FFA4 (Oh et al., 2010; Watson et al., 2012). G–protein–independent β-arrestin signalling may therefore be important, and in particular, this appears to be the case for FFA4. For example, the anti-inflammatory properties of this receptor in macrophages have been reported to be β-arrestin-2 dependent, involving a pathway where FFA4 activation results in β-arrestin-2 interaction with TAK1 binding protein 1 (TAB1), preventing the TAK1/TAB1 interaction required for a TAK1 mediated inflammatory response (Oh et al., 2010).

Table 2.

Properties of the FFA family of receptors relevant to metabolic and inflammatory processes

| Receptor | Signal transduction | Expression | Physiological role |

|---|---|---|---|

| FFA1 | Gαq/11 Gαi/o | Pancreatic β-cell | Acute: ↑ Glucose stimulated insulin secretion Chronic: Influences cell viability |

| Pancreatic α-cell | ↑ Glucagon secretion | ||

| Gut | ↑ GIP, GLP-1, CCK secretion | ||

| FFA2 | Gαi/o Gαq/11 | Adipose | ↑ Differentiation Inhibits lipolysis ↑ Glucose Uptake |

| Pancreas | Function unknown | ||

| Gut | ↑ GLP-1 secretion | ||

| Immune cells | Influences leukocyte differentiation and chemotaxis | ||

| FFA3 | Gαi/o | Pancreas | Function unknown |

| Gut | ↑ PYY secretion | ||

| Immune cells | Function unknown | ||

| FFA4 | Short isoform: Gαq/11 and β-arrestin-2 Long isoform: β-arrestin-2 | Adipose | ↑ Differentiation ↑ Glucose uptake |

| Pancreas | ↑ Cell viability | ||

| Gut | ↑ GLP-1, CCK secretion Inhibits ghrelin secretion | ||

| Immune cells | Anti-inflammatory |

Tissue expression patterns differ for each of the four FFA receptors. FFA1 is expressed at high levels in brain, enteroendocrine cells of the gut, and in pancreas, with enriched levels in pancreatic islets and particularly in the insulin-producing β-cells (Briscoe et al., 2003; Itoh et al., 2003). FFA2 is expressed at the highest levels in immune cells including neutrophils, monocytes, and b-lymphocytes (Brown et al., 2003; Kotarsky et al., 2003b) and is also expressed in both enteroendocrine cells and adipocytes (Hong et al., 2005; Ge et al., 2008). FFA3 is expressed in pancreas, spleen, enteroendocrine cells and blood mononuclear cells (Brown et al., 2003). Some studies have suggested that FFA3 is expressed in adipocytes (Hirasawa et al., 2005; Gotoh et al., 2007; Oh et al., 2010; Taneera et al., 2012); however, others have found only FFA2 and not FFA3 in adipocytes (Hong et al., 2005; Ge et al., 2008; Zaibi et al., 2010). FFA4 expression has been detected in human pancreatic islets, lung, immune cells, particularly macrophages, enteroendocrine cells and adipocytes (Hirasawa et al., 2005; Gotoh et al., 2007; Tanaka et al., 2008b; Miyauchi et al., 2009; Oh et al., 2010; Taneera et al., 2012).

Physiological roles of the LCFA receptors, FFA1 and FFA4, in metabolic and inflammatory processes

Taken together, the pharmacological properties and expression patterns of the FFA family receptors suggest that these receptors may be of physiological relevance in metabolic and inflammatory processes. In particular, the expression of these receptors in adipose tissue, pancreas, enteroendocrine and immune cells has prompted significant interest in investigating the role of FFA receptors in metabolic diseases, most notably type 2 diabetes and obesity, as well as in inflammatory processes. Considering the prevalence of these diseases with worldwide estimates of over 347 and 500 million people affected by diabetes and obesity, respectively (Danaei et al., 2011; WHO, 2013); elucidating the mechanisms that promote or protect against development of these disorders is of great interest.

Insulin and glucagon secretion

It has long been known that LCFAs are critical to insulin secretion following a period of fasting (Dobbins et al., 1998), and indeed, acute elevations in LCFAs have been shown to enhance glucose-stimulate insulin secretion (GSIS) from pancreatic β-cells (Haber et al., 2003). Given the high level of FFA1 expression in these cells and the ability of this receptor to couple to Gαq/11, a pathway often associated with enhancement of GSIS (Kebede et al., 2009), it was hypothesized that LCFAs amplify GSIS through activation of FFA1. Numerous studies using a variety of both in vitro and in vivo models have now confirmed that FFA1 is responsible for approximately 50% of the acute effect of LCFAs on GSIS (Itoh et al., 2003; Itoh and Hinuma, 2005; Salehi et al., 2005; Steneberg et al., 2005; Latour et al., 2007; Tan et al., 2008; Alquier et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2010; Schmidt et al., 2011a; Yashiro et al., 2012). A recent examination of the mechanism responsible for this effect demonstrated that FFA1 activates protein kinase D to promote F-actin depolymerization, suggesting that FFA1 influences insulin release via modulation of intracellular granule transport (Ferdaoussi et al., 2012). Although not as well studied, FFA4 expression has also been reported in both human pancreatic islets and rodent β-cell lines (Kebede et al., 2008; 2009; Taneera et al., 2012). While the specific cell types expressing FFA4 in human islets has not yet been determined, its expression in rodent β-cell lines raises the possibility that FFA4 may also contribute, at least to some degree, directly to LCFA-mediated enhancement of GSIS. To date, no studies have examined this possibility, although it may warrant further consideration.

In contrast to the beneficial acute effects on GSIS, long-term elevation of plasma LCFAs is detrimental to β-cell function and results in a decline in GSIS (Haber et al., 2003). Initial studies suggested that FFA1 may mediate the negative long-term effects of LCFAs (Steneberg et al., 2005). However, subsequent studies have found conflicting results, and the emerging consensus is that FFA1 activation is not detrimental to GSIS. Support for this derives from independently generated mouse models that have found that FFA-null mice fed a high-fat diet become as glucose intolerant as wild-type mice (Kebede et al., 2008; Lan et al., 2008). Additionally, a β–cell-specific FFA1 overexpression mouse model demonstrated enhanced insulin secretion, improved glucose tolerance, and resistance to impairment of glucose intolerance when fed a high-fat diet (Nagasumi et al., 2009). Finally, FFA1 selective agonists have not reproduced the toxic effects of long-term LCFA treatment on β-cells (Tan et al., 2008). Collectively, this current evidence suggests that FFA1 likely does not mediate the long-term effects of LCFA exposure on insulin secretion. Instead, recent work has suggested that the toxic effects of long-term LCFA exposure on GSIS results from β-cell death associated with reactive oxygen species generated in LCFA metabolism (Gehrmann et al., 2010). Conflicting results have also been reported on the role of FFA1 in improving pancreatic cell viability, with both treatment using a FFA1 antagonist, DC260126 (Wu et al., 2012) and a FFA1 agonist, TUG469 (Wagner et al., 2013), shown to protect against palmitate-induced β-cell apoptosis in mouse and rat models respectively. Furthermore, the protective effect of oleate against palmitate-induced apoptosis in the NIT-1 β-cell line was reduced by FFA1 knockdown, again suggesting a protective role for this receptor (Zhang et al., 2007). It has also recently been suggested that FFA4 activation may protect pancreatic islets from lipotoxicity by increasing cell viability and preserving β-cell mass (Taneera et al., 2012).

Glucose homeostasis is also regulated through the secretion of glucagon from pancreatic α-cells, which acts primarily on the liver to convert stored glycogen into glucose, thus raising blood glucose levels. Glucagon secretion occurs in response to low blood glucose levels and LCFAs have also been shown to stimulate increased glucagon secretion. While the expression of FFA1 in α-cells has been controversial, several studies have shown that elimination of FFA1 expression decreases LCFA-induced glucagon release both in vitro and in vivo in rodent models (Flodgren et al., 2007; Lan et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2011). In contrast, a recent study found that a selective FFA1 agonist, TAK-875, decreased glucagon secretion from isolated rat islets (Yashiro et al., 2012). At present it is not clear if this represents differential signalling properties between TAK-875 and the LCFAs at FFA1, or if other unknown factors account for the differing results of these studies.

Gastrointestinal hormone secretion

The enteroendocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract secrete a number of hormones that have effects on GSIS, glucagon secretion, gastrointestinal tract motility and appetite/food intake (Cuomo et al., 2011; Deacon and Ahren, 2011; Warzecha and Dembinski, 2012). FFA1 and FFA4 are co-expressed in enteroendocrine L cells that express and secrete glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1), peptide YY (PYY) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP); these incretins influence glucose homeostasis through effects on insulin and glucagon secretion, appetite and energy intake. Consistent with this, elimination of FFA1 expression in mice reduces LCFA-stimulated GLP-1 and GIP secretion (Edfalk et al., 2008). Similarly, FFA4 was proposed to mediate the effect of α-linolenic acid on GLP-1 release measured from the mouse STC-1 enteroendocrine cell line (Hirasawa et al., 2005). A recent study has indicated these effects on incretin secretion are also seen in primary human L cells, where the FFA1/FFA4 agonist GW9508 was found to stimulate both GLP-1 and PYY secretion (Habib et al., 2013). Activation of both FFA1 and FFA4 also results in the secretion of cholecystokinin (CCK), a peptide hormone that stimulates the digestion of fat and protein (Tanaka et al., 2008a; Liou et al., 2011). FFA4 is also expressed at high levels in ghrelin-positive cells (Lu et al., 2012), a gastric peptide hormone that controls appetite and energy homeostasis, and activation of FFA4 has been found to inhibit ghrelin secretion (Lu et al., 2012). FFA4 may also play a role in promoting enteroendocrine cell survival, as activation of FFA4 prevented apoptosis in the STC-1 cell line (Katsuma et al., 2005). These observations suggest that FFA1 and FFA4 may act as intestinal nutrient sensors for dietary fat in the gut and promote metabolic homeostasis through indirect actions on insulin and glucagon release, satiety, and energy harvest, all of which have implications on the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Adipose development and function

Obesity is characterized as the accumulation of excess white adipose tissue (WAT). WAT acts an energy storage depot that is capable of storing and releasing lipid in times of excess or deficiency respectively. Under conditions of excess energy input, WAT expansion occurs partly through an increase in adipocyte number. FFA4 plays an important role in adipocyte expansion; knockdown of FFA4 in vitro leads to a reduction in adipocyte differentiation and lipid accumulation (Gotoh et al., 2007) and FFA4-null mice exhibit decreased adipocyte differentiation (Ichimura et al., 2012). This decreased adipocyte differentiation is associated with an increase in adipocyte size and results in high-fat diet-induced obesity in FFA4-null mice that is more severe than that of wild-type mice (Ichimura et al., 2012). Furthermore, activation of FFA4 leads to an enhancement in adipocyte glucose uptake (Oh et al., 2010), which helps to prevent fat deposition in ectopic tissues, and FFA4-null mice fed a high-fat diet exhibit fatty liver (Ichimura et al., 2012). Similar to rodents, a loss-of function single-nucleotide polymorphism in FFA4 (R270H) appears to correlate with the risk for obesity in humans (Ichimura et al., 2012). Although FFA1 is not expressed in adipocytes, several SNP variations in FFA1 have been positively correlated with body mass index, body composition and plasma lipids in humans (Walker et al., 2011), suggesting that FFA1 may indirectly affect adipose development and function in humans.

Inflammation

The development of obesity, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes is commonly associated with a chronic level of low-grade inflammation that is characterized by the accumulation of pro-inflammatory cells in adipose tissue and altered cytokine and chemokine secretion (Monteiro and Azevedo, 2010; Lumeng and Saltiel, 2011; Ouchi et al., 2011). These immunological changes contribute to the development of insulin resistance, which influences the development of type 2 diabetes and pathological cardiac processes (Monteiro and Azevedo, 2010; Lumeng and Saltiel, 2011; Ouchi et al., 2011). FFA4 is expressed on immune cells, particularly macrophages and has been shown to mediate the anti-inflammatory properties of n-3 FAs in these cells (Oh et al., 2010). The importance of this finding is supported by evidence that FFA4-null mice fed a high-fat diet exhibit enhanced macrophage-induced inflammation in adipose tissue (Ichimura et al., 2012). Furthermore, administration of n-3 FAs to wild type, but not FFA4-null mice, inhibits inflammation and enhances systemic insulin sensitivity, with wild-type mice specifically displaying increased insulin stimulated-glucose disposal rates, indirectly suggesting improved muscle insulin sensitivity and increased suppression of hepatic glucose production (Oh et al., 2010; Ichimura et al., 2012). The anti-inflammatory effects of FFA4 may also extend beyond macrophages. For example, in one study intracerebroventricular administration of n-3 and n-6 FAs was associated with local anti-inflammatory effects in the hypothalamus, resulting in decreased food intake, weight reduction and improved insulin sensitivity (Cintra et al., 2012). Although this study did not carry out knockout studies that would have been required to directly demonstrate the involvement of FFA4 in these effects, the study did demonstrate that the n-3 and n-6 FAs were capable of activating hypothalamic FFA4 receptors. Therefore, clearly future work should examine the possibility that FFA4 may be responsible for these anti-inflammatory effects.

Physiological roles of the SCFA receptors, FFA2 and FFA3

Metabolism

Similar to the role of FFA4 in adipocyte expansion, knockdown of FFA2 in vitro leads to a reduction in adipocyte differentiation and lipid accumulation (Hong et al., 2005; Ge et al., 2008), and in at least one study, FFA2-null mice fed a high-fat diet were found to have decreased adipocyte numbers and reduced body fat mass (Bjursell et al., 2011). However, a more recent study found the opposite, in that FFA2-null mice were obese compared with their wild-type littermates when fed either normal chow or high-fat diets (Kimura et al., 2013). Indeed, Kimura et al. further demonstrated that the effect was directly related to FFA2 expression in adipocytes, as a transgenic mouse overexpressing FFA2 specifically in adipocytes remained lean even when fed a high-fat diet. As with FFA4, activation of FFA2 enhances adipocyte glucose uptake (Hoveyda et al., 2010), and has additionally been shown to mediate the anti-lipolytic effect of SCFA treatment on adipocytes both in vitro and in vivo (Hong et al., 2005; Ge et al., 2008). Thus, although the knockout studies have been contradictory, the current data do suggest that FFA2 plays a critical role in the regulation of plasma glucose and lipid profiles through effects on adipocyte function.

The SCFA receptors have also been demonstrated to affect the secretion of gastrointestinal peptides. FFA2 and FFA3 are both expressed in colonic endocrine L cells, and elimination of FFA2 expression reduces SCFA-stimulated GLP-1 secretion both in vitro and in vivo, which correlates with an impairment in glucose tolerance in mice (Tolhurst et al., 2012). In addition to GLP-1, L cells also secrete PYY, a peptide that normally inhibits gut motility, increases intestinal transit rate and reduces energy harvest (Simpson et al., 2012), and PYY levels are decreased in FFA3-null mice (Karaki et al., 2006; 2008; Samuel et al., 2008; Tazoe et al., 2008). Additionally, FFA2 has been suggested to mediate the release of gut 5-HT, which plays a role in gastric motility-mediated appetite regulation (Karaki et al., 2006). Taken together, these findings support a role for SCFA receptors in the regulation of host energy balance through effects on hormone secretion in the gastrointestinal tract.

Although not studied in detail, the expression of both SCFA receptors, FFA2 and FFA3, have also been reported in both pancreas and pancreatic β-cell lines (Brown et al., 2003; Kebede et al., 2009). This raises the possibility that these receptors may have a role in directly regulating insulin secretion and GSIS. As both receptors couple to Gi/o-coupled signalling pathways, which are associated with inhibition of GSIS, and FFA2 also couples to Gq/11 pathways associated with enhancement of GSIS, it is likely that the overall effect of SCFAs on insulin secretion may be complex. To date, only one patent application has directly looked at SCFA receptors on insulin release, showing limited data indicating that activation of FFA3 inhibits GSIS in the mouse MIN6 insulinoma cell line (Leonard et al., 2006). This finding is consistent with an observation that the SCFA propionate does inhibit GSIS in isolated rat islets (Ximenes et al., 2007), although this study did not determine the receptor mediating the effect. To date, no studies have directly examined the role of FFA2 in islet function and GSIS; however, this clearly is an area that should be examined in the future.

Inflammation

SCFAs have also been reported to exhibit anti-inflammatory properties, particularly in the gut (Miller, 2004), and some of these effects are directly mediated through the FFA family. FFA2, which is expressed at high levels in neutrophils and eosinophils, is implicated in the differentiation of leukocytes including monocytes and granulocytes (Senga et al., 2003), and following activation by SCFAs, FFA2 has been shown to regulate the inflammatory response in immune cells. FFA2 activation in neutrophils results in a rise in intracellular Ca2+ and mediates subsequent SCFA-dependent chemotaxis (Le Poul et al., 2003; Maslowski et al., 2009; Sina et al., 2009; Vinolo et al., 2011), implicating SCFAs and FFA2 in the migration of neutrophils towards sites of injury or infection. This action would have effects on pathological states with unresolving inflammation, such as irritable bowel disease (IBD) and colitis, particularly as these are conditions of the gut where SCFAs are generated at high levels. The role of FFA2 in intestinal inflammation has been examined and conflicting results presented by two different groups. In a study by Maslowski et al. (2009), FFA2-null mice exhibited exacerbated immune responses and greater morbidity in both acute and chronic models of colitis, and the beneficial effects of the SCFA, acetate, were not observed in FFA2-null mice (Maslowski et al., 2009). In contrast, Sina et al. (2009) found that while FFA2-null mice did show increased mortality in an acute model of intestinal inflammation, these mice were protected from inflammatory tissue damage in chronic models (Sina et al., 2009). Recently, it was shown that both FFA2 and FFA3-null mice had reduced inflammatory responses following intestinal damage induced by trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid administration, and a delayed response and pathogen clearance following Citrobacter rodentium infection, suggesting that these receptors mediate beneficial inflammatory responses at least in these models (Kim et al., 2013). Thus, the current evidence supports a role for SCFAs receptors in inflammatory responses of the gut, even if conflicting knockout studies perhaps make it unclear at present as to whether agonism or antagonism would be the preferred therapeutic mode of action.

Therapeutic potential of the FFA receptor family

Based on the physiological data demonstrating the role of FFA1–4 in glucose and lipid homeostasis, adiposity and inflammation, there has been significant interest in modulating the activity of FFA receptors for the treatment of a wide range of conditions including obesity, insulin resistance, atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease and IBD (Stoddart et al., 2008; Hara et al., 2011; Hudson et al., 2011; Talukdar et al., 2011). The majority of studies indicate that activation of FFA1 and FFA4, and possibly FFA2/3, would be therapeutically useful for the treatment of metabolic and inflammatory diseases, while a small number of studies suggesting that inhibition of FFA receptors, particularly FFA2 for inflammatory conditions of the gut, would be beneficial (Sina et al., 2009; Bjursell et al., 2011). Not surprisingly, small-molecule agonists of each of the FFA receptors have received at least some interest in drug development programmes. However, in addition to the development of synthetic receptor ligands, modulation of FFA activity may also be achieved through alternative approaches including dietary intervention and/or modulation of gut microbiota composition. The potential for each of these three therapeutic strategies for the treatment of metabolic and inflammatory diseases are discussed in the subsequent sections.

Development of small molecules targeting FFA1-4

There has been significant attention given to developing high-affinity synthetic ligands targeting the FFA family of receptors receptors (for reviews of available synthetic ligands see Bharate et al., 2009; Hudson et al., 2011; Ulven, 2012). To date, FFA1 has received the most attention primarily because of the large number of studies that have demonstrated that FFA1 agonists enhance GSIS and have glucose-lowering effects even in obese and/or diabetic animals (Briscoe et al., 2006; Tan et al., 2008; Doshi et al., 2009; Lin et al., 2011; Tsujihata et al., 2011). A promising phase II clinical trial with the FFA1 agonist, TAK-875, found that administration of the compound to diabetic patients resulted in improvements in GSIS and blood glucose control, with a low risk of hypoglycaemia (Araki et al., 2012; Burant et al., 2012; Leifke et al., 2012; Yashiro et al., 2012). This suggests that small-molecule agonism of FFA1 is a viable therapeutic strategy for type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, this approach may be safer than the traditional insulin secretagogues, such as the sulfonylureas, which increase basal insulin secretion independent of the prevailing glucose concentration, and therefore increase the risk of hypoglycaemia (El-Kaissi and Sherbeeni, 2011). While there has been less focus on the remaining FFA receptors, given their reported effects on metabolic and inflammatory processes it is not surprising that all members of the FFA family remain interesting potential therapeutic targets.

Considerations in developing small-molecule therapeutics targeting the FFA family

There are several important considerations that need to first be addressed in developing small-molecule therapeutics targeting the FFA receptor family. Firstly, there is significant overlap in the ligands that activate the two LCFA receptors, FFA1 and FFA4, and the two SCFA receptors, FFA2 and FFA3. In the case of FFA1 and FFA4, this is particularly true with respect to the endogenous ligands, but also many FFA1 selective ligands reported in the literature display at least micromolar potency at FFA4 (Briscoe et al., 2006; Shimpukade et al., 2012). Similarly, although there are currently only two academic reports describing synthetic FFA4 agonists, in both cases the ligands retained at least some activity at FFA1 (Suzuki et al., 2008; Shimpukade et al., 2012). Developing selective ligands for FFA2 and FFA3 has been even more challenging. One early study described selective orthosteric agonists derived from small carboxylic acids; however, these structures are not very ‘drug-like’, have low potency, and only modest selectivity (Schmidt et al., 2011b). Several molecules have also been described in recent patents as agonists for both FFA2 and FFA3 (for review, see Ulven, 2012); however, until the recent detailed characterization of one such series as potent and selective orthosteric agonists at both human and mouse FFA2 (Hudson et al., 2013a), little was known about the detailed pharmacology of these compounds.

One alternative to developing selective orthosteric ligands for receptors activated by the same endogenous ligands would be to target allosteric binding sites, which typically have greater variation between closely related receptors relative to orthosteric binding sites (May et al., 2007; Hudson et al., 2013c). This has been used to develop a series of FFA2 selective agonists (Lee et al., 2008; Smith et al., 2011). It also appears that at least some FFA1 agonists previously believed to be orthosteric in fact bind allosterically (Lin et al., 2012). Targeting allosteric binding sites may also be advantageous for improved efficacy and reduced toxicity, as many allosteric ligands will only produce an effect when an endogenous orthosteric agonist is also present, maintaining endogenous temporal and spatial patterns of receptor activation, and thus, improving safety (Hudson et al., 2013c).

Functional selectivity, or the ability of a ligand to initiate a distinct cellular signalling response by stabilizing a specific receptor active state (Goupil et al., 2012), may also be an important consideration for the development of novel synthetic ligands targeting the FFA family. For example, the anti-inflammatory effects of n-3 FAs via FFA4 are reportedly mediated by β-arrestin-2, while the effects on glucose uptake in adipocytes are through Gαq/11 (Oh et al., 2010). This suggests that β–arrestin-biased FFA4 ligands would contribute to improvements in glucose handling via anti-inflammatory mechanisms, while G–protein-biased ligands might be more effective for other aspects of metabolic disorders.

In addition to these pharmacodynamics considerations, pharmacokinetic issues have also presented a significant challenge, particularly in the development of agonists for FFA1. Specifically, the structure of the vast majority of agonists described for FFA1 are effectively synthetic FAs, containing both a charged carboxylic acid (or suitable bioisotere) head group attached to an extended hydrophobic tail (Bharate et al., 2009; Hudson et al., 2011). As a result, these compounds tend to be very lipophilic and like the FAs themselves, show high-plasma protein binding. Indeed the focus of many recent medicinal chemistry studies on FFA1 has shifted to improving pharmacokinetic absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion properties of the novel ligands, instead of simply identifying ligands with better potency or selectivity (Christiansen et al., 2012; 2013). The development of the clinical candidate, TAK-875, represents the best example of this, where chemical alterations to the lead scaffold were able to both reduce hydrophobicity and improve oral bioavailability, in order to identify the final preferred compound that has now progressed into phase III trials (Negoro et al., 2010).

Given that in the majority of cases agonism appears to be the preferred therapeutic mode of action at the FFA receptor family, another issue that must be taken into consideration in the development of FFA therapeutics is receptor desensitization. In particular, activation of FFA4 has been widely reported to strongly stimulate phosphorylation, β-arrestin recruitment and internalization (Hirasawa et al., 2005; Burns and Moniri, 2010; Shimpukade et al., 2012; Watson et al., 2012). Thus, it is possible that chronic treatment with an FFA4 agonist will lead to desensitization and ultimately tachyphylaxis. To avoid this, development of biased FFA4 agonists that stimulate receptor activation, but not desensitization and internalization, may be a viable option. Additionally, at least for FFA2, there is some indication that antagonism might also be beneficial, particularly in chronic inflammatory conditions. At present there is a significant lack of available antagonists for the FFA receptors, with current reports only describing antagonists for FFA1 (Briscoe et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2012) and FFA2 (Hudson et al., 2012b; Saniere et al., 2012). Complicating matters further, the antagonists described for FFA2 are human-selective, producing no effect on the rodent orthologues of the receptor, and therefore, greatly complicating their pre-clinical validation. Indeed, this has led one company that has developed small-molecule FFA2 antagonists for the treatment of inflammatory conditions of the gut (Saniere et al., 2012), to take the unusual step of progressing their compound directly into early phase I, and even phase II clinical trials in the absence of pre-clinical proof-of principle studies from rodent models.

Finally, toxic and/or side effects of small molecules need to be considered. For example, FFA1 has been implicated in the proliferation of human breast cancer cell lines and bronchial epithelial cells (Yonezawa et al., 2004; Hardy et al., 2005; Gras et al., 2009), and thus, alteration of signalling pathways mediated by FFAs may have unwanted effects on cell growth, among other possibilities. Recent evidence from mouse models also suggests that FFA1 plays an important role in osteoclast differentiation and thus bone remodelling, as well as in mediating the effect of transarachidonic acids on neonatal hypoxic-ischemic induced neurovasculature degeneration (Honore et al., 2013; Wauquier et al., 2013). Additionally, although an overwhelming majority of evidence supports an agonist approach for most FFA receptors, there are a small number of studies that suggest otherwise. These include studies showing that treatment of the MIN6 mouse pancreatic β-cell line with an FFA1 antagonist protected against palmitate-induced ER stress and apoptosis (Wu et al., 2012), or demonstrating that FFA2-null mice are protected against intestinal inflammation (Sina et al., 2009). Considering these data, it is possible that FFA1 and FFA2 agonists may contribute to lipotoxicity and exacerbate chronic inflammation respectively. Ultimately, although several key questions remain concerning mechanisms of FFA receptor signalling, the development of synthetic small molecules targeting the FFA receptors remains a promising area for novel therapeutics in the treatment of metabolic and inflammatory conditions.

Targeting FFA1-4 through modulation of dietary intake and microbiota composition

In addition to manipulating FFA receptor activity through the administration of synthetic small molecules, altering the levels of natural ligands for these receptors may also be possible through the diet. For example, increasing daily intake of polyunsaturated FAs by supplementing the diet with meats, fish and fish oils may be an indirect method of targeting FFA1 and FFA4 activation. Increasing the dietary intake of other non-traditional agonists for FFA receptors could also have beneficial effects on LCFA receptors. For example, berberine, which is the active constituent of the Chinese herb Rhizoma coptidis, has been shown to activate FFA1 and stimulate GSIS in vitro (Rayasam et al., 2010), in addition to inhibiting the development of high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance in rats (Gu et al., 2012). Thus, supplementing the diet with components that will directly activate LCFA receptors may represent an attractive alternative means to influence physiological processes downstream of FFA1 or FFA4.

Similarly, levels of SCFAs vary depending on the amount of non-digestible fibre in the diet. In contrast to LCFA levels that can be directly manipulated through diet, this represents an indirect method as bacterial fermentation of the fibre is first required to generate SCFAs. Considering this, manipulating the composition of SCFA-generating microflora in the gastrointestinal tract through the use of pre and/or probiotics could also be used to alter SCFA profiles. For instance, bacteria of the Bacteroidetes phylum produce high amounts of acetate and propionate, whereas bacteria of the Firmicutes phylum produce high amounts of butyrate. As acetate and propionate are more potent agonists at FFA2 than butyrate, shifting bacterial composition in this respect would be hypothesized to alter levels of FFA2 activation.

Considerations for modulating dietary intake and microbiota composition to target FFA receptors

Similar to the challenges that have been associated with developing small-molecule therapeutics for the FFA family of receptors, there are also a number of issues that must be considered before undertaking dietary or microbiota-based therapeutic approaches for these receptors. The first, and perhaps most important in the context of the current review, is that it is difficult to specifically attribute the beneficial effects of these approaches to actions at the FFA receptors. As described earlier, both LCFAs and SCFAs have alternate modes of actions to the FFA family of receptors including for example LCFAs activating PPAR signalling cascades and SCFA acting as HDAC inhibitors (Sealy and Chalkley, 1978; Medina et al., 1997; Waldecker et al., 2008). Therefore, determining which effects are specifically mediated by members of the FFA family of receptors presents a significant challenge. The most obvious means currently to address this is through knockout mouse studies and indeed, such studies have been used to suggest the beneficial effects of dietary n-3 FA supplementation on inflammation and insulin sensitivity are mediated by FFA4 (Oh et al., 2010). Similarly, conjugated linoleic acids (CLAs), a popular food supplement thought to reduce body fat and increase lean muscle mass, have been demonstrated to enhance GSIS in pancreatic β-cells, but not in primary β-cells from FFA1 knockout mice (Schmidt et al., 2011a). Several knockout studies have also aimed to determine if the SCFA receptors provide the key link between gut microbiota and host. For example, Maslowski et al. (2009) found that FFA2-null mice displayed dys-regulation in their inflammatory responses to models of colitis and arthritis that were similar to the effects observed when using germ-free mice in these same models. In another study looking at the link between FFA3 and gut microbiota, FFA3-null mice were found to be leaner than wild-type mice if raised under normal conditions, or following colonization with a model fermentative microbial community; however, this was not the case if the mice were raised under germ-free conditions (Samuel et al., 2008). Finally, a very recent study demonstrated that FFA2-null mice found to be obese compared with their wild-type littermates showed no weight difference when raised under germ-free conditions, or following treatment with antibiotics (Kimura et al., 2013).

While such knockout studies have been informative, it is perhaps unclear how well these may translate to the treatment of human disease. As the diet of a mouse is very different from that of a human, it may be predicted that the overall response and indeed the mechanisms underlying the effects of dietary or microbiota manipulations will vary among species. Several recent studies have demonstrated clear differences in the pharmacology of the SCFA receptors between species (Hudson et al., 2012a,b; 2013a), and in at least one case these differences appear likely to have originated as an evolutionary adaptation to accommodate different diets between species (Hudson et al., 2012a). A more detailed examination of species variations in pharmacology across all of the FFA receptors suggests that there are at least some differences in potency and/or selectivity of both endogenous and synthetic ligands for all members of the FFA receptor family (Hudson et al., 2013b), clearly indicating that extrapolation of animal studies linking FFA receptor actions and diet to humans will be challenging.

Therefore one must use alternate approaches to link dietary or microbiota manipulations with the FFA receptors in humans. Many large-scale epidemiological studies have examined connections between dietary FA intake and disease, with one focus often being the impact of the typical Western diet abundant in n-6, but low in n-3 FAs. Such epidemiological evidence suggests that a high-fat diet low in n-3 relative to n-6 FAs often results in an insulin resistant state that is characterized by increased pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion (Moussavi et al., 2008; Gillingham et al., 2011; Poudyal et al., 2011; Cascio et al., 2012). However, while at least one study has described FFA4 as an n-3 FA sensor (Oh et al., 2010), the fact that others have shown similar potencies of n-3 and n-6 FAs at both FFA1 and FFA4 (Briscoe et al., 2003; Itoh et al., 2003; Kotarsky et al., 2003a; Hirasawa et al., 2005), indicates that these effects of n-3 compared with n-6 FAs cannot easily be attributed only to specific actions at the FFA receptor family. Although such observations could conceivably be explained if both n-3 and n-6 FAs produce beneficial effects through the FFA1 and/or FFA4, with only the n-6 FAs producing detrimental effects via non-FFA receptor mechanisms of action, at present there is no direct evidence to support such a hypothesis. Interestingly, in contrast to supplementing the diet with specific beneficial FAs, numerous studies have also demonstrated that lowering overall FA concentrations in the body may also be associated with improved insulin resistance, oral glucose tolerance, and basal insulin levels in humans (Santomauro et al., 1999; Lehto et al., 2012; Na et al., 2012). While the wealth of current in vitro and in vivo data suggest these beneficial effects of lowering total FA levels are unlikely to be mediated by decreased FFA receptor function, this possibility has also not yet been directly examined.

Clearly there is a need to more directly answer these questions on the specific contribution that FFA receptors have in mediating the effects of dietary manipulations. Likely, the easiest way to achieve this will be through future genetic studies exploiting human FFA receptor polymorphisms that alter receptor function or expression (for a review, see Hudson et al., 2013b). Of particular note, one non-coding polymorphism in FFA1, rs1573611, has recently been reported to alter the relationship between plasma FA concentration and insulin secretion in humans (Wagner et al., 2013), while a non-synonymous coding polymorphism of FFA4 (R270H) results in greatly reduced receptor function (Ichimura et al., 2012), suggesting either of these would be attractive candidates to provide a genetic link between FFA1 or FFA4 function and dietary manipulation of LCFA levels. Alternative to genetic studies, if FFA receptor antagonists become approved for use in humans, these conceivably could be used in small-scale clinical studies to establish more direct links between dietary or microbiota manipulations and the FFA receptors. Indeed, this may become the case for FFA2, where one antagonist (Saniere et al., 2012) has recently progressed through phase I trials.

A second significant question that must be addressed before considering dietary or microbiota therapeutic approaches to target the FFA receptors, is whether such manipulations will actually be able to achieve therapeutically relevant changes in LCFA or SCFA concentrations. Several studies have explored the effects of n-3 FA or CLA supplementation on total plasma FA composition (Rustan et al., 1998; Doyle et al., 2005; Vandal et al., 2008). These studies have generally found that supplementation can significantly increase total plasma n-3 FA or CLA levels, for example in one study when healthy adult men were given a CLA supplement for 8 weeks it resulted in a threefold increase in CLA levels measured in total blood lipid (Doyle et al., 2005). However, it is less clear how these changes in total lipid levels correlate with changes in free unbound FAs. Furthermore, even after supplementation, the concentrations of the supplemented FAs remain low compared with other more prominate plasma FA species such as oleate or linoleate (Doyle et al., 2005), both of which would be expected to activate either FFA1 or FFA4 with relatively similar potencies. Considering these factors, it may be reasonable to hypothesize that it is through actions on the more directly accessible gut where dietary supplements of n-3 or other LCFAs are most likely to produce effects via FFA1 and/or FFA4.

Similarly, several studies have also explored how increasing dietary fibre affects SCFA levels, generally finding increased concentrations, particularly in acetate, both in the gut and plasma (Akanji et al., 1989; Yen et al., 2011; Francois et al., 2012), which appear to correspond well with the reported potency of acetate at human FFA2. This suggests that dietary fibre supplementation is perhaps likely to alter FFA2 function in humans. However, determining whether microbiota manipulations will result in therapeutically relevant changes in SCFA levels presents an even greater challenge. A number of methods exist to manipulate the composition of gut microbiota. Firstly, prebiotics, or non-digestible carbohydrates suggested to selectively stimulate the growth, activity, or both, of bacterial species already in the colon, may promote the generation of SCFAs and these have been linked to beneficial metabolic and/or anti-inflammatory effects (Cani et al., 2004; Delzenne et al., 2005; Parnell and Reimer, 2009). Alternatively, probiotics, or live microbial food supplements, could be used and many studies have now also explored their potential health benefits (Andreasen et al., 2010; Kadooka et al., 2010). If there is concern that pre or probiotics will not survive gastric transit, an alternative method of promoting a beneficial microbial balance that may have utility is faecal transplantation of gut microbiota from a healthy donor to treat another patient. Faecal transplant of microflora has recently proven to be a valuable tool in the treatment of certain diseases, including colitis caused by Clostridium difficile (Khoruts et al., 2010). Importantly, a recent study demonstrated that infusion of intestinal microbiota from lean human donors to those with metabolic syndrome altered intestinal microbiota composition and resulted in increased insulin sensitivity (Vrieze et al., 2012). Finally, a very recent study has also found that the composition of gut microbiota is altered following gastric bypass surgery in both mice and humans and that at least a portion of the weight loss observed following the surgery in mice appears to result from these microbiota changes (Liou et al., 2013). Although each of these approaches to manipulate gut microbiota would be hypothesized to alter both overall SCFA concentration, as well as the relative profiles of individual SCFAs, there is currently little data on the extent to which this is the case, nor is there any current data directly linking any possible health benefits of these manipulations in humans to either FFA2 or FFA3. These will be critical questions to be answered in the future if these approaches are to be advanced as therapeutically relevant strategies specifically targeting FFA2 and/or FFA3.

One final consideration that must be taken into account before developing dietary approaches to target FFA receptors is that both dietary intake and modulation of gut microflora may be associated with a number of side effects such as bloating, cramping, and flatulence. To prevent this, it will be important to elucidate a dose with beneficial physiological effects that does not cause pathological changes in gut microstructure. Furthermore, altered composition of gut microbiota brought on by a Western diet or use of antibiotics has been suggested as a reason for increased incidence of allergies and asthma in humans (Shreiner et al., 2008; Musso et al., 2010). Despite these concerns, altering the activity of LCFA and/or SCFA receptors, whether directly through the diet, or indirectly through biotics supplementation or microbial transplantation, are promising strategies to influence processes involved in the development and/or prevention of metabolic and inflammatory disorders.

Traditional therapeutics versus manipulation of diet/microflora

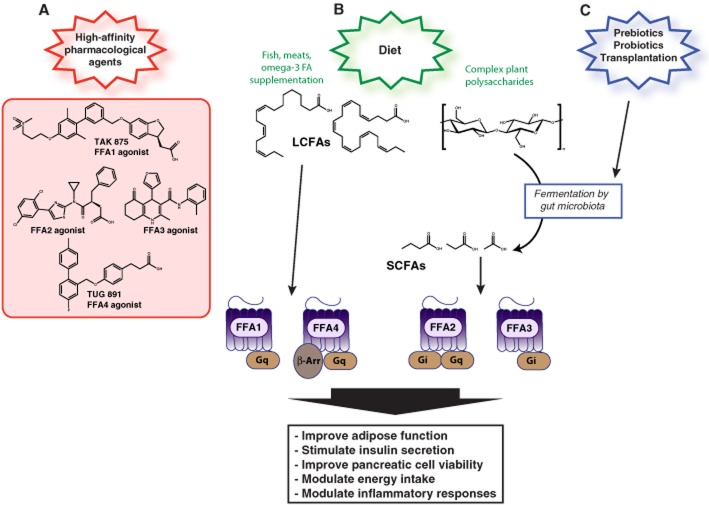

As there are a number of potential strategies to modulate FFA receptor activation for the treatment of metabolic and inflammatory diseases (Figure 1), there is some debate as to which approach, or approaches, would be most beneficial. While the available evidence suggests that all three, including small-molecule pharmacological agents, dietary changes, or manipulation of gut microflora populations, represent promising strategies to target FFA receptors, there are potential advantages or disadvantages to each strategy that might affect therapeutic success and are highlighted in Table 3.

Figure 1.

Modulation of FFA activation can be achieved through several different methods to prevent and/or treat metabolic and inflammatory diseases. Changes in FFA1-4 activity can be achieved directly through small-molecule targeting of specific FFAs (A). FFA activity can also be modulated indirectly via changes in dietary intake (B) or modulation of gut microflora composition (C). Increased consumption and/or supplementation of the diet with fish, meats or omega-3 FAs will result in increased levels of LCFAs and FFA1 and FFA4 activation. Increased intake of complex plant polysaccharides will result in generation of SCFAs through fermentation by gut microbiota and activation of FFA2 and FFA3. Levels of SCFAs can also be altered indirectly via modulation of gastrointestinal microflora composition through administration of biotics or bacterial transplantation. Activation of FFAs has beneficial effects on a variety of physiological processes that are associated with metabolic and inflammatory processes.

Table 3.

Comparison of traditional small-molecule therapeutics to dietary or microbiota manipulation of FFA receptor function

| Traditional therapeutics | Dietary and/or microbiota manipulations | |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | Can be designed to achieve desired effect High potency Receptor specific Target allosteric binding sites Exploit G-protein or β-arrestin bias Full versus partial agonism Only method for which antagonism of FFAs is possible | Natural products often avoid regulatory approval issues Suited for use as a prophylactic treatment Low cost in both development and to the end user Microflora composition can be easily monitored and used as a biomarker |

| Disadvantages | Receptor desensitization High development cost Toxic/side effects may include certain cancers, lipotoxicity, exacerbation of chronic inflammation, effects on bone remodelling and neurovasculature | Lower potency relative to bioavailability Off-target effects Side effects may include bloating, cramping, flatulence Development of novel therapeutic strategies may be impeded by lack of patent protection |

In addition to the properties highlighted in Table 3, there are a few final issues that may affect both drug development- or dietary-based therapeutic approaches. Firstly, is the possibility that the expression of FFA receptors may be altered or reduced in disease states. For example, both FFA1 and FFA4 expression levels are down-regulated in islets isolated from diabetic patients (Del Guerra et al., 2010), perhaps limiting the efficacy in targeting these receptors for this condition. Furthermore, it is possible that FFA polymorphisms may affect therapeutic efficacy of FFA agonists. It should also be considered that the method of preferred treatment may vary on an individual patient basis, and it is possible that the best treatment may in fact be a combination of approaches. This is exemplified by recent success in using low-dose thiazolidinedione treatment in combination with n-3 FA supplementation (Kuda et al., 2009), suggesting that similar combination therapies could be useful for the FFA family. Finally, because of the challenges associated with directly showing efficacy and mode of action for dietary and microbiota approaches, it is perhaps likely that these will remain better suited as a prophylactic approach to improve general health, while small-molecule therapeutics with a validated target, known mechanism of action, and clinically proven efficacy are likely to remain the best options for individuals with a clearly defined disease state.

In summary, FFA1-4 comprise a recently deorphanized family of GPCRs. This GPCR family, which differs with respect to ligand potency, generation of signal transduction cascades and expression patterns, regulates and coordinates some of the effects of FFAs on adiposity, adipose function, appetite control, gut motility, glucose homeostasis and inflammation. Given the recent increase in metabolic and inflammatory diseases, there is a critical need for novel effective therapeutic strategies. Modulation of FFA receptor activity represents an exciting possibility to achieve this, whether through small-molecule pharmacological agents, diet, or microflora modification. The key requirement of future studies will be to develop specific and efficacious small-molecule ligands and/or to identify specific components of the diet, natural products or bacterial species that can be shown to produce beneficial effects through actions at FFA1-4. Ultimately, modulation of FFA signalling represents a promising strategy that will likely prove invaluable for the timely prevention, management, and treatment of metabolic and inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgments

HJD is supported by a National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Canada Graduate Scholarship and Izaak Walton Killam Predoctoral Scholarship. BDH is supported by a Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR) Fellowship. This work was supported by an NSERC Discovery Grant (MEMK).

Glossary

- CCK

cholecystokinin

- CLA

conjugated linoleic acid

- FA

fatty acid

- FFA

free fatty acid

- FFA1

free fatty acid receptor 1

- FFA2

free fatty acid receptor 2

- FFA3

free fatty acid receptor 3

- FFA4

free fatty acid receptor 4

- GIP

glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide

- GLP-1

glucagon- like peptide 1

- GSIS

glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- IBD

irritable bowel disease

- LCFA

long-chain fatty acid

- MCFA

medium-chain fatty acid

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- PYY

peptide YY

- SCFA

short-chain fatty acid

- WAT

white adipose tissue

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akanji AO, Peterson DB, Humphreys S, Hockaday TD. Change in plasma acetate levels in diabetic subjects on mixed high fiber diets. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1365–1370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to receptors and channels (GRAC), 5th edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(Suppl. 1):S1–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alquier T, Peyot ML, Latour MG, Kebede M, Sorensen CM, Gesta S, et al. Deletion of GPR40 impairs glucose-induced insulin secretion in vivo in mice without affecting intracellular fuel metabolism in islets. Diabetes. 2009;58:2607–2615. doi: 10.2337/db09-0362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen AS, Larsen N, Pedersen-Skovsgaard T, Berg RM, Moller K, Svendsen KD, et al. Effects of Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM on insulin sensitivity and the systemic inflammatory response in human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2010;104:1831–1838. doi: 10.1017/S0007114510002874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araki T, Hirayama M, Hiroi S, Kaku K. GPR40-induced insulin secretion by the novel agonist TAK-875: first clinical findings in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14:271–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharate SB, Nemmani KV, Vishwakarma RA. Progress in the discovery and development of small-molecule modulators of G-protein-coupled receptor 40 (GPR40/FFA1/FFAR1): an emerging target for type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2009;19:237–264. doi: 10.1517/13543770802665717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjursell M, Admyre T, Goransson M, Marley AE, Smith DM, Oscarsson J, et al. Improved glucose control and reduced body fat mass in free fatty acid receptor 2-deficient mice fed a high-fat diet. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300:E211–E220. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00229.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe CP, Tadayyon M, Andrews JL, Benson WG, Chambers JK, Eilert MM, et al. The orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR40 is activated by medium and long chain fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11303–11311. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211495200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe CP, Peat AJ, McKeown SC, Corbett DF, Goetz AS, Littleton TR, et al. Pharmacological regulation of insulin secretion in MIN6 cells through the fatty acid receptor GPR40: identification of agonist and antagonist small molecules. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;148:619–628. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AJ, Goldsworthy SM, Barnes AA, Eilert MM, Tcheang L, Daniels D, et al. The orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11312–11319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burant CF, Viswanathan P, Marcinak J, Cao C, Vakilynejad M, Xie B, et al. TAK-875 versus placebo or glimepiride in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:1403–1411. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61879-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns RN, Moniri NH. Agonism with the omega-3 fatty acids alpha-linolenic acid and docosahexaenoic acid mediates phosphorylation of both the short and long isoforms of the human GPR120 receptor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396:1030–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder PC. n-3 Fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: evidence explained and mechanisms explored. Clin Sci (Lond) 2004;107:1–11. doi: 10.1042/CS20040119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cani PD, Dewever C, Delzenne NM. Inulin-type fructans modulate gastrointestinal peptides involved in appetite regulation (glucagon-like peptide-1 and ghrelin) in rats. Br J Nutr. 2004;92:521–526. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascio G, Schiera G, Di Liegro I. Dietary fatty acids in metabolic syndrome, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. Curr Diab Rev. 2012;8:2–17. doi: 10.2174/157339912798829241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen E, Due-Hansen ME, Urban C, Grundmann M, Schroder R, Hudson BD, et al. Free fatty acid receptor 1 (FFA1/GPR40) agonists: mesylpropoxy appendage lowers lipophilicity and improves ADME properties. J Med Chem. 2012;55:6624–6628. doi: 10.1021/jm3002026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen E, Due-Hansen ME, Urban C, Grundmann M, Schmidt J, Hansen SV, et al. Discovery of a potent and selective free fatty acid receptor 1 agonist with low lipophilicity and high oral bioavailability. J Med Chem. 2013;56:982–992. doi: 10.1021/jm301470a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cintra DE, Ropelle ER, Moraes JC, Pauli JR, Morari J, Souza CT, et al. Unsaturated fatty acids revert diet-induced hypothalamic inflammation in obesity. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook SI, Shellin JH. Short chain fatty acids in health and disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:499–507. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuomo R, D'Alessandro A, Andreozzi P, Vozzella L, Sarnelli G. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake: do gut motility, enteric nerves and entero-hormones play together? Minerva Endocrinol. 2011;36:281–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danaei G, Finucane MM, Lu Y, Singh GM, Cowan MJ, Paciorek CJ, et al. National, regional, and global trends in fasting plasma glucose and diabetes prevalence since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 370 country-years and 2.7 million participants. Lancet. 2011;378:31–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60679-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport AP, Alexander SPH, Sharman JL, Pawson AJ, Benson HE, Monaghan AE, et al. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXVIII. G protein-coupled receptor list: recommendations for new pairings with cognate ligands. Pharmacol Rev. 2013;65:967–986. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.007179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deacon CF, Ahren B. Physiology of incretins in health and disease. Rev Diabet Stud. 2011;8:293–306. doi: 10.1900/RDS.2011.8.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Guerra S, Bugliani M, D'Aleo V, Del Prato S, Boggi U, Mosca F, et al. G-protein-coupled receptor 40 (GPR40) expression and its regulation in human pancreatic islets: the role of type 2 diabetes and fatty acids. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;20:22–25. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delzenne NM, Cani PD, Daubioul C, Neyrinck AM. Impact of inulin and oligofructose on gastrointestinal peptides. Br J Nutr. 2005;93(Suppl. 1):S157–S161. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins RL, Chester MW, Stevenson BE, Daniels MB, Stein DT, McGarry JD. A fatty acid-dependent step is critically important for both glucose- and non-glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:2370–2376. doi: 10.1172/JCI1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doshi LS, Brahma MK, Sayyed SG, Dixit AV, Chandak PG, Pamidiboina V, et al. Acute administration of GPR40 receptor agonist potentiates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in vivo in the rat. Metabolism. 2009;58:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle L, Jewell C, Mullen A, Nugent AP, Roche HM, Cashman KD. Effect of dietary supplementation with conjugated linoleic acid on markers of calcium and bone metabolism in healthy adult men. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59:432–440. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edfalk S, Steneberg P, Edlund H. Gpr40 is expressed in enteroendocrine cells and mediates free fatty acid stimulation of incretin secretion. Diabetes. 2008;57:2280–2287. doi: 10.2337/db08-0307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Eijk HMH, Bloemen JG, Dejong CHC. Application of liquid chromatorgraphy-mass spectrometry to measure short chain fatty acids in blood. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009;877:719–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Kaissi S, Sherbeeni S. Pharmacological management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: an update. Curr Diab Rev. 2011;7:392–405. doi: 10.2174/157339911797579160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdaoussi M, Bergeron V, Zarrouki B, Kolic J, Cantley J, Fielitz J, et al. G protein-coupled receptor (GPR)40-dependent potentiation of insulin secretion in mouse islets is mediated by protein kinase D1. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2682–2692. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2650-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flodgren E, Olde B, Meidute-Abaraviciene S, Winzell MS, Ahren B, Salehi A. GPR40 is expressed in glucagon producing cells and affects glucagon secretion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois IE, Lescroart O, Veraverbeke WS, Marzorati M, Possemiers S, Evenepoel P, et al. Effects of a wheat bran extract containing arabinoxylan oligosaccharides on gastrointestinal health parameters in healthy adult human volunteers: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial. Br J Nutr. 2012;108:2229–2242. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512000372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge H, Li X, Weiszmann J, Wang P, Baribault H, Chen JL, et al. Activation of G protein-coupled receptor 43 in adipocytes leads to inhibition of lipolysis and suppression of plasma free fatty acids. Endocrinology. 2008;149:4519–4526. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehrmann W, Elsner M, Lenzen S. Role of metabolically generated reactive oxygen species for lipotoxicity in pancreatic beta-cells. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12(Suppl. 2):149–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillingham LG, Harris-Janz S, Jones PJ. Dietary monounsaturated fatty acids are protective against metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease risk factors. Lipids. 2011;46:209–228. doi: 10.1007/s11745-010-3524-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh C, Hong YH, Iga T, Hishikawa D, Suzuki Y, Song SH, et al. The regulation of adipogenesis through GPR120. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;354:591–597. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goupil E, Laporte SA, Hebert TE. Functional selectivity in GPCR signaling: understanding the full spectrum of receptor conformations. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2012;12:817–830. doi: 10.2174/138955712800959143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gras D, Chanez P, Urbach V, Vachier I, Godard P, Bonnans C. Thiazolidinediones induce proliferation of human bronchial epithelial cells through the GPR40 receptor. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2009;296:L970–L978. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.90219.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimaldi PA. Metabolic and nonmetabolic regulatory functions of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor beta. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21:186–191. doi: 10.1097/mol.0b013e32833884a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu JJ, Gao FY, Zhao TY. A preliminary investigation of the mechanisms underlying the effect of berberine in preventing high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance in rats. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2012;63:505–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber EP, Ximenes HM, Procopio J, Carvalho CR, Curi R, Carpinelli AR. Pleiotropic effects of fatty acids on pancreatic beta-cells. J Cell Physiol. 2003;194:1–12. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habib AM, Richards P, Rogers GJ, Reimann F, Gribble FM. Co-localisation and secretion of glucagon-like peptide 1 and peptide YY from primary cultured human L cells. Diabetologia. 2013;56:1413–1416. doi: 10.1007/s00125-013-2887-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara T, Hirasawa A, Ichimura A, Kimura I, Tsujimoto G. Free fatty acid receptors FFAR1 and GPR120 as novel therapeutic targets for metabolic disorders. J Pharm Sci. 2011;100:3594–3601. doi: 10.1002/jps.22639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy SS, Onge GG, Joly E, Langelier Y, Prentki M. Oleate promotes the proliferation of breast cancer cells via the G protein-coupled receptor GPR40. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13285–13291. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410922200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa A, Tsumaya K, Awaji T, Katsuma S, Adachi T, Yamada M, et al. Free fatty acids regulate gut incretin glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion through GPR120. Nat Med. 2005;11:90–94. doi: 10.1038/nm1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa A, Hara T, Katsuma S, Adachi T, Tsujimoto G. Free fatty acid receptors and drug discovery. Biol Pharm Bull. 2008;31:1847–1851. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong YH, Nishimura Y, Hishikawa D, Tsuzuki H, Miyahara H, Gotoh C, et al. Acetate and propionate short chain fatty acids stimulate adipogenesis via GPCR43. Endocrinology. 2005;146:5092–5099. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honore JC, Kooli A, Hamel D, Alquier T, Rivera JC, Quiniou C, et al. Fatty acid receptor gpr40 mediates neuromicrovascular degeneration induced by transarachidonic acids in rodents. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:954–961. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoveyda H, Brantis C, Dutheuil G, Zoute L, Schils D, Bernard J. 2010. Compounds, pharmaceutical composition and methods for use in treating metabolic disorders. International patent application WO2011076734.

- Hudson BD, Smith NJ, Milligan G. Experimental challenges to targeting poorly characterized GPCRs: uncovering the therapeutic potential for free fatty acid receptors. Adv Pharmacol. 2011;62:175–218. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385952-5.00006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BD, Christiansen E, Tikhonova IG, Grundmann M, Kostenis E, Adams DR, et al. Chemically engineering ligand selectivity at the free fatty acid receptor 2 based on pharmacological variation between species orthologs. FASEB J. 2012a;26:4951–4965. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-213314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BD, Tikhonova IG, Pandey SK, Ulven T, Milligan G. Extracellular ionic locks determine variation in constitutive activity and ligand potency between species orthologs of the free fatty acid receptors FFA2 and FFA3. J Biol Chem. 2012b;287:41195–41209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.396259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BD, Due-Hansen ME, Christiansen E, Hansen AM, Mackenzie AE, Murdoch H, et al. Defining the molecular basis for the first potent and selective orthosteric agonists of the FFA2 free fatty acid receptor. J Biol Chem. 2013a;288:17296–17312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.455337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BD, Murdoch H, Milligan G. Minireview: the effects of species ortholog and SNP variation on receptors for free fatty acids. Mol Endocrinol. 2013b;27:1177–1187. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson BD, Ulven T, Milligan G. The therapeutic potential of allosteric ligands for free fatty acid sensitive GPCRs. Curr Top Med Chem. 2013c;13:14–25. doi: 10.2174/1568026611313010004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura A, Hirasawa A, Poulain-Godefroy O, Bonnefond A, Hara T, Yengo L, et al. Dysfunction of lipid sensor GPR120 leads to obesity in both mouse and human. Nature. 2012;483:350–354. doi: 10.1038/nature10798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Hinuma S. GPR40, a free fatty acid receptor on pancreatic beta cells, regulates insulin secretion. Hepatol Res. 2005;33:171–173. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2005.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Kawamata Y, Harada M, Kobayashi M, Fujii R, Fukusumi S, et al. Free fatty acids regulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells through GPR40. Nature. 2003;422:173–176. doi: 10.1038/nature01478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouven X, Charles M-A, Desnos M, Ducimetière P. Circulating nonesterified fatty acid level as a predictive risk factor for sudden death in the population. Circulation. 2001;104:756–761. doi: 10.1161/hc3201.094151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadooka Y, Sato M, Imaizumi K, Ogawa A, Ikuyama K, Akai Y, et al. Regulation of abdominal adiposity by probiotics (Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055) in adults with obese tendencies in a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010;64:636–643. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaki S, Mitsui R, Hayashi H, Kato I, Sugiya H, Iwanaga T, et al. Short-chain fatty acid receptor, GPR43, is expressed by enteroendocrine cells and mucosal mast cells in rat intestine. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;324:353–360. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaki S, Tazoe H, Hayashi H, Kashiwabara H, Tooyama K, Suzuki Y, et al. Expression of the short-chain fatty acid receptor, GPR43, in the human colon. J Mol Histol. 2008;39:135–142. doi: 10.1007/s10735-007-9145-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsuma S, Hatae N, Yano T, Ruike Y, Kimura M, Hirasawa A, et al. Free fatty acids inhibit serum deprivation-induced apoptosis through GPR120 in a murine enteroendocrine cell line STC-1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19507–19515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412385200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebede M, Alquier T, Latour MG, Semache M, Tremblay C, Poitout V. The fatty acid receptor GPR40 plays a role in insulin secretion in vivo after high-fat feeding. Diabetes. 2008;57:2432–2437. doi: 10.2337/db08-0553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebede MA, Alquier T, Latour MG, Poitout V. Lipid receptors and islet function: therapeutic implications? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11(Suppl. 4):10–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2009.01114.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoruts A, Dicksved J, Jansson JK, Sadowsky MJ. Changes in the composition of the human fecal microbiome after bacteriotherapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:354–360. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181c87e02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]