Summary

Many bacteria colonize surfaces and transition to a sessile mode of growth. The plant pathogen Agrobacterium tumefaciens produces a unipolar polysaccharide (UPP) adhesin at single cell poles that contact surfaces. Here we report that elevated levels of the intracellular signal cyclic diguanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) lead to surface-contact-independent UPP production and a red colony phenotype due to production of UPP and the exopolysaccharide cellulose, when A. tumefaciens is incubated with the polysaccharide stain Congo Red. Transposon mutations with elevated Congo Red staining identified presumptive UPP negative regulators, mutants for which were hyperadherent, producing UPP irrespective of surface contact. Multiple independent mutations were obtained in visN and visR, activators of flagellar motility in A. tumefaciens, now found to inhibit UPP and cellulose production. Expression analysis in a visR mutant and isolation of suppressor mutations, identified three diguanylate cyclases inhibited by VisR. Null mutations for two of these genes decrease attachment and UPP production, but do not alter cellular c-di-GMP levels. However, analysis of catalytic site mutants revealed their GGDEF motifs are required to increase UPP production and surface attachment. Mutations in a specific presumptive cyclic diguanosine monophosphate phosphodiesterase also elevate UPP production and attachment, consistent with c-di-GMP activation of surface-dependent adhesin deployment.

Keywords: Attachment, Unipolar polysaccharide, Cellulose, Congo Red, VisN-VisR, Biofilm, Motility, c-di-GMP

Introduction

Bacteria can exist as either free-swimming single cells or attached to surfaces and sessile (Pratt & Kolter, 1998). The transition from a motile to sessile mode of growth is often coupled with termination of flagellar motility and activation of exopolysaccharide production (Branda et al., 2005, Li et al., 2012, Blair et al., 2008). Bacterial attachment can lead to biofilm formation, which is typified by the production of a self-secreted extracellular matrix composed of exopolysaccharides, proteins, lipids and sometimes DNA (Cogan & Keener, 2004, Danhorn & Fuqua, 2007, Kolter & Greenberg, 2006). The motile-to-biofilm switch is influenced by environmental cues and impacts antibiotic resistance, bacterial dispersion, and disease persistence (Mah et al., 2003, Danhorn & Fuqua, 2007, Hall-Stoodley et al., 2004).

In many bacteria the intracellular signal cyclic diguanosine monophosphate (c-di-GMP) has emerged as a major determinant of whether cells favor motility or attachment (D’Argenio & Miller, 2004). The general trend is that elevated c-di-GMP levels promote polysaccharide biosynthesis and biofilm formation while impeding the synthesis of flagella and swimming motility (Hengge, 2009). Cellular pools of c-di-GMP are inversely controlled by diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) and phosphodiesterases (PDEs) (Hengge, 2009). DGCs contain a conserved GGDEF domain and catalyze synthesis of c-di-GMP molecules while PDEs contain either an EAL or HD-GYP domain and drive degradation of the signal molecules (Simm et al., 2004, Ryan et al., 2006). Many bacterial genomes encode multiple proteins with GGDEF and EAL domains, and at some frequency both motifs are found on the same protein. In addition, these proteins often also contain additional regulatory motifs such as HAMP and PAS domains, suggesting that they respond to environmental stimuli to control c-di-GMP levels (Tamayo et al., 2007).

Recent work has revealed distinct mechanisms by which c-di-GMP regulates the motile-to-sessile transition in different bacteria. Intracellular c-di-GMP controls activities that promote surface colonization including the elaboration of adhesin proteins, diminishing flagellar locomotion and exopolysaccharide synthesis (Ryan et al., 2006). The response to c-di-GMP can be transduced by a variety of receptors including riboswitches and several different classes of proteins, most notably those with PilZ-type domains, but also others. These effectors can control transcription or impart direct allosteric regulation of target processes. One of the most comprehensively studied systems is in the dimorphic Alpha-proteobacterium Caulobacter crescentus for which c-di-GMP plays an important role in controlling cellular differentiation from a motile, flagellated swarmer cell to a non-motile and often adherent stalked cell (Brown et al., 2009). Two active DGC proteins DgcB and PleD physically localize to the incipient stalk pole, and in parallel with inactivation of PDE proteins, drive a localized c-di-GMP increase, which stimulates stalk morphogenesis and entry of the cell into the S phase of active DNA replication (Abel et al., 2011). This control is in part mediated by association of c-di-GMP with an enzymatically inactive DGC homologue called PopA, and possibly additional effectors (Duerig et al., 2009).

Agrobacterium tumefaciens is a pathogen that causes crown gall disease on plants due to its ability to transfer a segment of its own DNA into nucleus of plant cells where it integrates into host cell chromosomes (Van Larebeke et al., 1974, Watson et al., 1975). A. tumefaciens is a member of the Alphaproteobacteria as is C. crescentus, and although it is rod-shaped, also exhibits asymmetric cell division (Brown et al., 2012). An early step in A. tumefaciens pathogenesis is attachment to host plants, which can subsequently lead to biofilm formation (Douglas et al., 1982, Matthysse, 1986). We have observed that a unipolar polysaccharide (UPP) is produced at a single pole of A. tumefaciens cells that contact surfaces during adhesion but this structure is rarely observed in planktonic cells or in colonies on solid media (Li et al., 2012, Xu et al., 2012). Therefore, the production of UPP is a landmark for permanent attachment and transitioning into the sessile polar attachment stage. Investigating UPP regulation should shed light on how bacterial cells sense and respond to surface contact and provide insights on the motile-to-sessile transition.

In this study, we first show that cells with elevated intracellular c-di-GMP levels produce the UPP independent of surface contact. Extending these findings we have isolated mutants that manifest misregulation of UPP synthesis and suppressors of these mutants that reverse this phenotype. Among mutants with altered c-di-GMP levels we have found that the VisN-VisR transcriptional regulators play a key role in regulating attachment, functioning to control motility while repressing the production of UPP and cellulose through modulating c-di-GMP levels. VisN and VisR impart a profound influence over the motile-to-sessile transition in A. tumefaciens at least in part through influencing c-di-GMP pools.

Results

Ectopic expression of a diguanylate cyclase homologue stimulates aggregation and UPP production

In many different bacteria, GGDEF proteins and c-di-GMP often control production of polysaccharides (Hengge, 2009). The PleD protein of Caulobacter crescentus was the first GGDEF protein for which diguanylate cyclase activity was demonstrated in vitro (Abel et al., 2011). PleD consists of tandem response regulator receiver domains and a GGDEF effector domain (Fig. S1), through which phosphorylation regulates c-di-GMP synthesis in C. crescentus (Aldridge et al., 2003). Well prior to the recognition of the widespread role for c-di-GMP, it was reported that synthesis of cellulose in vitro with a crude cellulase enzyme preparation from A. tumefaciens was strongly stimulated by c-di-GMP (Amikam & Benziman, 1989). During examination of specific Caulobacter homologues in A. tumefaciens (Kim, 2013), we observed that expression of a plasmid-borne pleD homologue (Atu1297, Plac-pleD) in an otherwise wild-type A. tumefaciens C58 resulted in a high frequency of large aggregates in colonies grown on solid medium (Fig. 1A) and similarly in planktonic cultures (Fig. S2A). These aggregates stained copiously with fluorescently tagged wheat germ agglutinin (fl-WGA), which labels a presumptive N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc) component of the UPP. Ectopic expression of pleD in an otherwise wild type strain also strongly elevated biofilm formation (Fig. 1B), suggesting increased levels of adhesive polysaccharides. However, in-frame deletion of pleD in an otherwise wild type strain did not diminish biofilm formation (Kim, 2013).

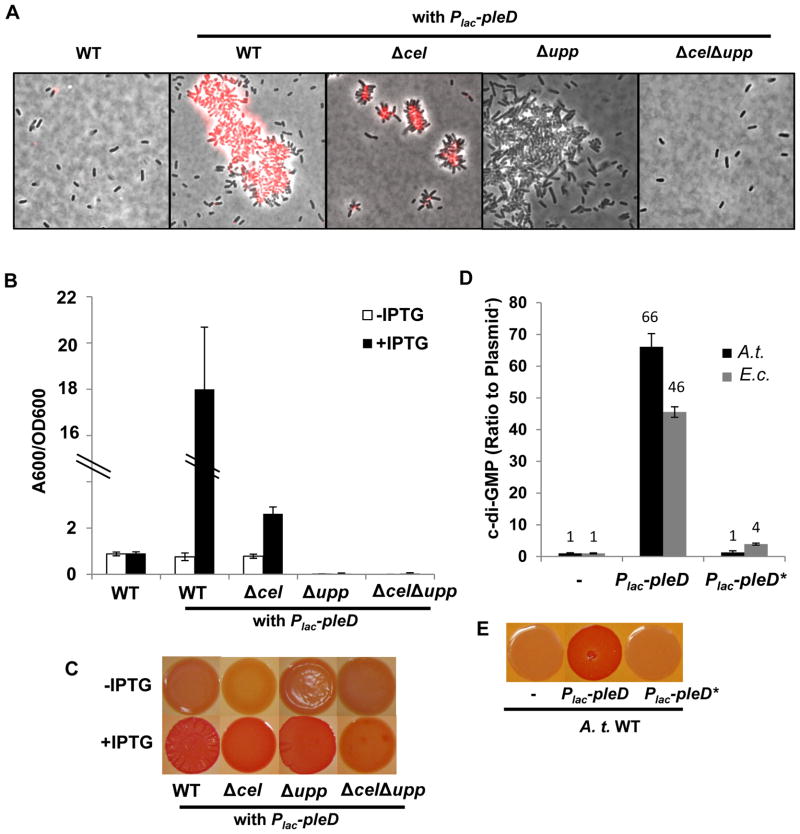

Figure 1. Ectopic expression of A. tumefaciens pleD and phenotypic characterization.

(A) Fluorescently conjugated WGA lectin (fl-WGA) labeling for UPP elaboration in colonies of A. tumefaciens C58 derivatives. Cells were suspended in ddH2O from fresh colonies of indicated strains on ATGN solid medium plus 0.5 mM IPTG, with or without the IPTG-inducible Plac-pleD plasmid. Cells were labeled by AlexaFluor594-WGA and viewed at 100× magnification on a Nikon E800 epifluorescence microscope (excitation, 510–560 nm; emission, >610 nm) and images are an overlay of phase contrast and fluorescence. (B) A quantitative biofilm assay for A. tumefaciens C58 derivatives at 48 h. Biofilms formed on PVC coverslips were stained by crystal violet, solubilized in 30% acetic acid and quantified by spectrophotometry at 600 nm. A600/OD600 represents the crystal violet quantification A600 normalized by culture optical density. White bars indicate cultures grown in ATGN medium without IPTG, and black bars for cultures grown in ATGN medium plus 0.5 mM IPTG. Values are averages of triplicate assays and error bars are standard deviation. (C) Congo Red binding phenotype of A. tumefaciens C58 derivatives. Strains harboring the Plac-pleD plasmid were grown on ATGN-CR solid media (80 μg/ml Congo Red), with (bottom row) or without (upper row) 0.5 mM IPTG supplementation. Images of the same row were taken from the same plate. (D) Measurement of intracellular levels of c-di-GMP in indicated strains carrying Plac-pleD (wild type plasmid) or Plac-pleD* (Plac-pleD plasmid carrying a GGEEF to GGAAF mutation). A.t. (black bars) represents A. tumefaciens C58 strain and E.c. (grey bars) represents E. coli DH5α. The intracellular level of c-di-GMP in either C58 or DH5α strain is normalized to 1. The Y-axis represents the ratio of C58 or DH5α strain harboring a pleD expression plasmid to the same strain without a plasmid (50–100 nM for A. tumefaciens and 250–500 nM for E. coli). Cells at stationary phase were pelleted and resuspended in c-di-GMP extraction buffer containing methanol and acetonitrile. Measurement of c-di-GMP by LC-MS/MS as described in the Methods. Values are averages of triplicate assays and error bars are standard deviation. (E) Congo Red binding phenotype of A. tumefaciens C58 strain carrying Plac-pleD (wild type plasmid) or Plac-pleD* (Plac-pleD with GGEEF to GGAAF mutation). Colonies were grown on ATGN-CR solid media plus 0.5 mM IPTG. Images were obtained from the same plate.

PleD-dependent phenotypes require the exopolysaccharides cellulose and UPP

Production of β-linked polysaccharides in colonies can often be visualized by growth in the presence of specific stains. The visible dye Congo Red stains colonies that produce specific polysaccharides (also in some cases amyloid proteins, (Howie & Brewer, 2009)), and the intensity of red staining is proportional to the amount of Congo Red-reactive polysaccharide produced (Romling, 2005). Growth under inducing conditions for A. tumefaciens harboring the Plac-pleD plasmid resulted in dark red staining on ATGN minimal medium with Congo Red (ATGN-CR) relative to the non-induced conditions (Fig. 1C). We designate this as the Elevated Congo Red (ECR) phenotype and will discuss it further below. The ECR phenotype suggested elevated polysaccharide production in A. tumefaciens due to Plac-pleD expression.

A. tumefaciens is recognized to produce several different exopolysaccharides including succinoglycan, β-1,2 glucan, β-1,3 glucan, cellulose and UPP. Independent and combinatorial mutational analysis of these different polysaccharides revealed that the UPP was strictly required for attachment (Xu et al., 2012), whereas the others were not required. Examination of these exopolysaccharide mutants expressing the Plac-pleD plasmid and grown on Congo Red revealed that either UPP or cellulose could suffice for the ECR phenotype, and that mutational disruption of both pathways was required to significantly diminish the intense Congo Red staining (Fig. 1C). None of the other exopolysaccharide mutants were affected for the PleD-stimulated ECR phenotype (Fig. S2B).

Induction of pleD expression in Δcel mutants resulted in small aggregates and rosettes in colonies on solid medium, which were extensively labeled with fl-WGA (Fig. 1A). Expression of pleD in Δupp mutants also drove aggregate formation in colonies, but in contrast these were fragile clusters without rosettes and seldomly labeled with fl-WGA. Strikingly, mutants with both Δcel Δupp deletions did not aggregate and revealed single cells with no visible fl-WGA staining (Fig. 1A). These findings suggest that ectopic pleD expression stimulates increased production of UPP and cellulose, both of which contribute to increased cellular aggregation.

Wild type C58 expressing the Plac-pleD plasmid exhibits elevated biofilm formation (Fig. 1B). The profound biofilm deficiency of the Δupp mutant could not be rescued by plasmid-borne pleD, and this was also true in the ΔuppΔcel mutant (Fig. 1B). The Δcel mutation alone significantly diminished PleD-stimulated biofilm formation, but this remained substantially greater than the plasmid free derivative (Fig. 1B). Although mutation of the cel genes does not substantially impact biofilm formation at native levels of pleD expression, elevated cellulose production in response to ectopic pleD expression clearly contributes to biofilm formation (Fig. 1B).

PleD of A. tumefaciens is a diguanylate cyclase that drives c-di-GMP synthesis

To test whether the plasmid borne pleD homologue elevates c-di-GMP, we measured intracellular levels of the signal molecule using liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The intracellular c-di-GMP concentration of the A. tumefaciens wild type strain is approximately 50–100 nM. The same strain harboring the Plac-pleD plasmid is approximately 66 fold higher than that observed in the absence of the plasmid (Fig. 1D). Site-specific mutation of the plasmid-borne pleD GGEEF motif (Fig. S1B, the putative catalytic site for diguanylate cyclases) to GGAAF (pleD*) abolished its ability to cause the ECR phenotype (Fig. 1E) and correspondingly decreased c-di-GMP levels to near wild type levels (Fig. 1D). Expression of the pleD plasmid in Escherichia coli DH5α (a heterologous host without other A. tumefaciens proteins and low basal c-di-GMP) also resulted in a striking increase in c-di-GMP when pleD expression was induced (46 fold over the same strain without the plasmid), and this increase was abolished in the GGAAF pleD* mutant (Fig. 1D). Taken together, these observations suggest that ectopic expression of pleD stimulates its DGC activity, increasing c-di-GMP levels in A. tumefaciens and elevating synthesis of both cellulose and UPP polysaccharides. In turn this results in the ECR phenotype and enhanced biofilm formation.

A genetic screen for transposon mutants that mimic ectopic pleD expression

With our understanding of the genetic basis for the ECR colony phenotype a forward genetic screen was implemented to systematically explore how production of the UPP polysaccharide is regulated (Fig. S3A and S3B). To avoid the influence of other EPSs (particularly cellulose) we used a C58 derivative genetically disabled for the synthesis of all major EPSs (succinoglycan, β-1,2 glucan, β-1,3 glucan and cellulose) except for UPP (this mutant was designated as EPS−UPP+). We reasoned that mutation of a negative regulator that would increase UPP production in colonies grown on ATGN-CR solid medium should phenocopy the ECR phenotype exhibited by strains ectopically expressing pleD. Mutagenesis of the EPS−UPP+ mutant with the Mariner transposon was performed, and greater than 25,000 colonies were screened on ATGN-CR plates, yielding a collection of mutants with the ECR phenotype. Mutants with elevated Congo Red binding (ECR mutants) were incubated with fl-WGA and observed under fluorescence microscopy to visualize UPP production. All ECR mutants exhibited notable production of UPP both in colonies (Fig. S3C) and in planktonic cultures (data not shown). The sites of transposon insertion were sequenced in these mutants and multiple independent disruptions were found in four discrete loci (initially designated as ECR1, ECR2, ECR3 and ECR4). Transposon insertions in Atu1130 and Atu1631, encoding a short chain dehydrogenase homologue (ECR2 class, three mutants) and a CheY single domain type response regulator (ECR3 class, six mutants) respectively, resulted in the ECR phenotype, but the basis for these mutant phenotypes remain unclear and they require additional analysis. The remaining two classes of mutants (ECR1 and ECR4) were examined further in this study.

VisN and VisR inversely regulate swimming and UPP-mediated biofilm formation

The ECR1 class of mutants was due to disruptions of two linked genes Atu0524 and Atu0525 (Fig. 2A), in which seven independent mutants were isolated. These genes are annotated in the A. tumefaciens genome as LuxR-FixJ type transcriptional regulators (Fig. 2B) and are highly homologous to visN and visR (vital in swimming), reported to control motility in Sinorhizobium meliloti and other rhizobia (Sourjik et al., 2000). The visN and visR genes form a presumptive two-gene operon and are located between the chemotaxis and flagellar gene clusters on the A. tumefaciens C58 circular chromosome. The visN and visR gene products share similarity within their C-terminal regions with the DNA binding domains of LuxR and FixJ homologues, as well as to each other (Fig. 2B). However, the N-terminal sequences of VisN and VisR do not resemble either the acylhomoserine lactone binding motif of LuxR homologues nor the phosphate-receiver domain of FixJ. The N-termini of VisN and VisR also do not resemble each other.

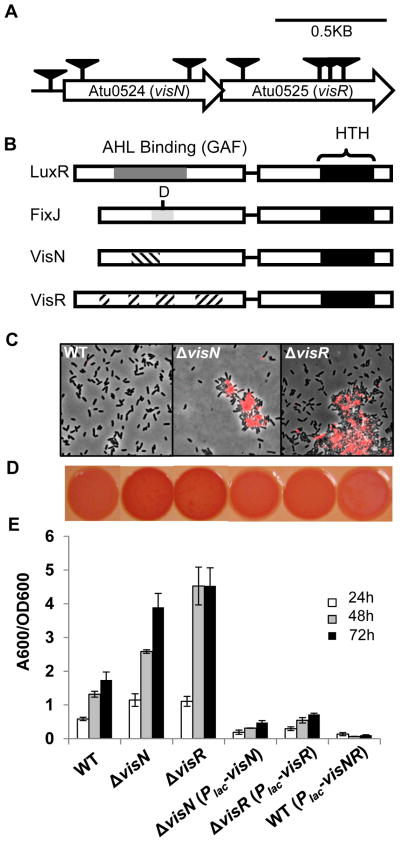

Figure 2. Phenotypic analysis of visN-visR mutants isolated from the ECR genetic screen.

(A) Genetic map and transposon insertions in visN (Atu0524) and visR (Atu0525) genes. Transposon mutants were isolated from a (EPS−UPP+) parent strain, an A. tumefaciens C58 derivative deficient in all major exopolysaccharides except for UPP. Triangles indicate transposon insertion sites isolated from independent transposon insertion events from a genetic screen for 25,000 colonies. (B) Comparison of the domain structures of LuxR and FixJ family proteins with the putative domains of VisN and VisR proteins from A. tumefaciens. Black boxes represent Helix-Turn-Helix (HTH) DNA binding motifs. The dark grey shade represents the acylhomoserine lactone (AHL) binding domain or GAF domain of LuxR-type proteins, the light grey domain represents the conserved receiver domain of FixJ-type proteins, with the conserved aspartic acid residue indicated, and the hatched regions represent the conserved residues of VisN and VisR proteins among different rhizobia. (C) Labeling with fl-WGA lectin for UPP elaboration in planktonic cultures of indicated A. tumefaciens C58 derivatives. Cells at exponential phase (OD600 0.6~0.8) were labeled by fl-WGA and viewed at 100× magnification on a Nikon E800 epifluorescence microscope (excitation, 510–560 nm; emission, >610 nm) with an overlay of phase contrast and fluorescence images. (D) Congo Red binding phenotypes of indicated A. tumefaciens C58 derivatives as labeled in panel E. Strains were grown on ATGN-CR solid medium plus 0.5 mM IPTG. (E) A quantitative biofilm assay plotting solubilized crystal violet staining (A600) normalized to culture OD600 by the indicated A. tumefaciens derivatives at 24 h, 48 h and 72 h as in Fig. 1B. All strains were grown in ATGN medium plus 0.5 mM IPTG. Values are averages of triplicate assays and error bars are standard deviation.

Mutations in visN and visR cause a loss of motility in S. meliloti due to failure to express flagellar genes (Sourjik et al., 2000). The A. tumefaciens transposon mutants in visN or visR were also non-motile (Fig. S4A). The transposon mutants described above were isolated in the EPS−UPP+ parent background, which exhibited a moderate decrease of biofilm formation and swimming motility relative to wild type because of one of the deleted polysaccharide gene clusters, chvAB, mutants of which are highly pleiotropic (Xu et al., 2012). Transposon insertions in visN might also be polar on downstream visR. We therefore generated individual site-specific, in-frame deletions of visN and visR genes in the original EPS−UPP+ parent and in the wild type. The EPS−UPP+ visN and visR deletion mutants exhibited phenotypes identical to the transposon mutants and to each other, and were non-motile (Fig. S4A). Both mutants exhibited elevated biofilm formation (Fig. S4C), even with the loss of swimming motility (known to diminish attachment efficiency (Merritt et al., 2007)). The ΔvisN and ΔvisR mutants also exhibited elevated UPP production in both colonies and planktonic phase (Fig. S4D).

The ΔvisN and ΔvisR mutations in the wild type resulted in phenotypes consistent with the EPS−UPP+ background. However, in colonies (Fig. 3C) and liquid medium (Fig. 2C) they formed very large aggregates with extensive UPP staining. On solid medium with Congo Red (ATGN-CR) ΔvisN and ΔvisR mutants had red ECR colony phenotypes (Fig. 2D). The ΔvisN and ΔvisR mutants were elevated for biofilm formation compared to the wild type (Fig. 2E).

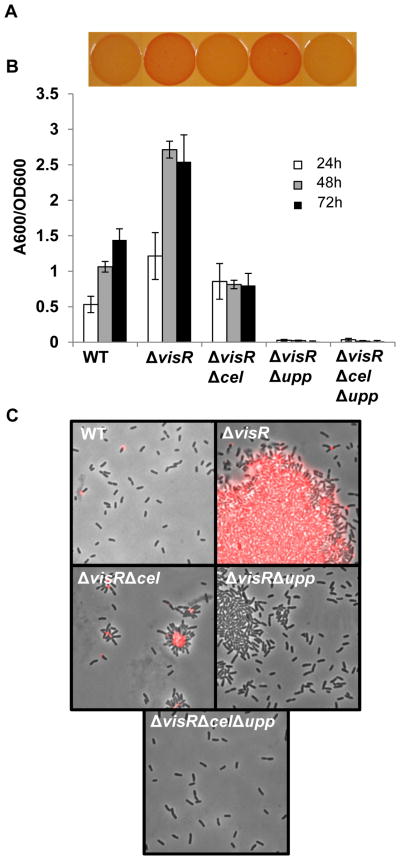

Figure 3. The ΔvisR mutant is elevated for UPP and cellulose production.

(A) Congo Red binding phenotypes of indicated A. tumefaciens C58 derivatives as in Fig. 1C. (B) A quantitative biofilm assay plotting solubilized crystal violet staining (A600) normalized to culture OD600 by the indicated A. tumefaciens derivatives at 24 h, 48 h and 72 h as in Fig. 1B. All strains were grown in ATGN medium. Values are averages of triplicate assays and error bars are standard deviation. (C) Labeling with fl-WGA lectin for UPP elaboration in colonies of indicated strains as described in Fig. 1A.

Ectopic expression of visN and visR

Both the visN and visR deletion mutants grown on ATGN-CR medium were complemented by the corresponding plasmid-borne gene expressed from Plac (Fig. 2D). Biofilm formation was in fact inhibited to below wild type levels by the individual visN and visR plasmids and a plasmid expressing both visN and visR caused the strongest inhibition (Fig. 2E). The ΔvisN and ΔvisR mutants were also fully complemented to wild type motility by these plasmids (Fig. S5A). Neither mutation was rescued by provision of the other gene (e.g. visN mutation with plasmid-borne visR) in terms of swimming motility or Congo Red staining, but a plasmid expressing both visN and visR corrected either mutant for both of these phenotypes (Fig. S5). This suggests that VisN and VisR play discrete roles in regulating the motile-to-sessile switch.

Cellulose and UPP both contribute to the visR mutant phenotypes

The ΔvisR mutant was chosen for further investigation since the ΔvisN and ΔvisR mutants phenocopy each other. To test whether the visR mutant phenotypes require UPP and cellulose, we constructed ΔvisRΔupp, ΔvisRΔcel double mutants and a ΔvisRΔcelΔupp triple mutant. The ΔvisRΔupp mutant retained an ECR phenotype similar to ΔvisR. The ΔvisRΔcel mutant was faintly redder than wild type, although significantly lighter than ΔvisR (Fig. 3A). These data suggest the ECR phenotype of the ΔvisR mutant in the otherwise wild type background is substantially due to cellulose overproduction, and to a lesser extent due to UPP overproduction (although in the original screen with the EPS−UPP+ parent, the ECR phenotype was due to UPP alone). The ECR phenotype was largely abolished in the ΔvisRΔcelΔupp mutant (Fig. 3A), reflecting the participation of both polysaccharides.

The ΔvisR mutant also was elevated for biofilm formation, and both cellulose and UPP contributed to this phenotype. The ΔvisRΔcel mutant was decreased for biofilm formation, revealing a role for cellulose in the increased biofilm formation of the ΔvisR mutant (Fig. 3B). Consistent with our observation that UPP is essential for biofilm formation, the ΔvisRΔupp mutant and ΔvisRΔcelΔupp mutant were completely unable to form biofilms (Fig. 3B). The ΔvisR mutant formed large aggregates in colonies, which were copiously labeled by fl-WGA (Fig. 3C). The ΔvisRΔcel mutant formed UPP--dependent small aggregates and rosettes in colonies, which were extensively labeled with fl-WGA. The ΔvisRΔupp mutant formed weakly associated, cellulose-dependent aggregates, which were seldomly labeled with fl-WGA (Fig. 3B). In contrast, ΔvisRΔcelΔupp mutants did not aggregate and revealed single cells with no visible fl-WGA staining. Overall, these findings suggest that both elevated UPP and increased cellulose production in the ΔvisR mutant drive cellular aggregation, enhance biofilm formation and contribute to the ECR phenotype.

UPP visualization with electron microscopy

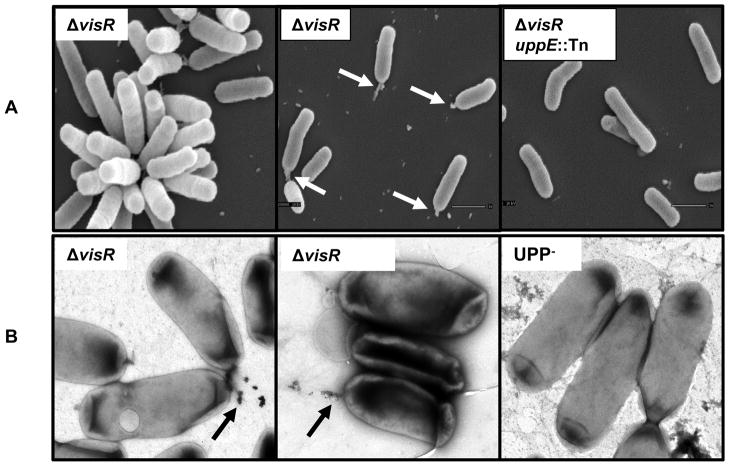

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed production of the UPP. To limit large aggregates due to cellulose that might obscure the UPP structure, the EPS−UPP+ΔvisR strain was used for electron microscopy. In contrast to wild type cells or EPS−UPP+ cells, EPS−ΔvisR mutants produced UPP in planktonic phase, thereby allowing it to be visualized more readily by electron microscopy. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed rosette formation (cellular aggregates due to adhesion between cells at their poles) and a consistent unipolar protrusion in EPS−ΔvisR mutants (Fig. 4A). This protrusion varied from a small unipolar bulb of material or a more extended, fibrillar material. The material was not visible on any cells of the EPS−ΔvisR mutant with a transposon insertion in uppE (Fig. 4A), one of UPP biosynthesis genes ((Xu et al., 2012)). Using TEM, unipolar fibers from the EPS−UPP+ΔvisR mutant were also decorated with colloidal gold-labeled WGA, whereas no polar labeling was observed for UPP− strains (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Visualization of UPP by electron microscopy.

(A) Visualization of UPP by scanning electron microscopy. Indicated strains were ΔvisR mutant in the EPS−UPP+ backgrounds. The uppE::Tn represents a Mariner transposon insertion in the uppE gene required for UPP biosynthesis. Bacterial cells on coverslips were fixed by glutaraldehyde, and after processing sputter coated with gold before observation using JEOL JSM-5800 LV Scanning Electron Microscope at 10 kV. White arrows indicate unipolar material. (B) Visualization of UPP by transmission electron microscopy for the ΔvisR mutant in the EPS−UPP+ backgrounds. The UPP− strain was uppA-F in-frame deletion mutant constructed in an otherwise wild type background. Cells were labeled with colloidal gold conjugated WGA, stained by uranyl acetate and observed on carbon-coated grids. Black arrows indicate the colloidal gold conjugated WGA labeled polar material.

A specific diguanylate cyclase homologue dgcA is required for elevated UPP in the ΔvisR mutant

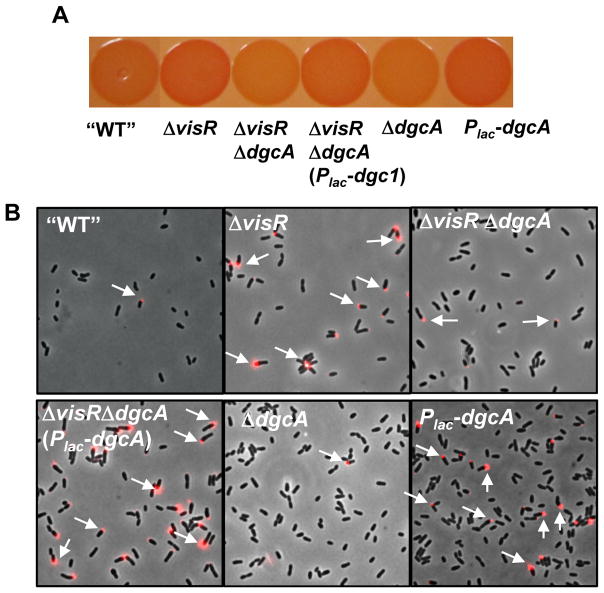

To further investigate how visN and visR exert their function in UPP control, we performed a genetic screen for suppressors by mutagenizing the EPS−UPP+ΔvisR mutant with the Mariner transposon to identify mutants with Decreased Congo Red binding (DCR) (Fig. S3A and B). As expected, we identified several UPP biosynthesis genes (Xu et al., 2012). In addition, three independent mutants were isolated with transposon insertions in Atu1257, encoding a putative GGDEF-type diguanylate cyclase homologue (designated dgcA) with seven predicted transmembrane domains (Fig. S1). In-frame deletion of dgcA in the EPS−UPP+ΔvisR mutant abolished the ECR phenotype and diminished UPP dysregulation, and these phenotypes could be complemented by providing a plasmid-borne Plac-dgcA (Fig. 5). This Plac-dgcA plasmid also resulted in elevated CR binding and UPP production in the EPS−UPP+ mutant (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Isolation of the putative GGDEF gene dgcA from a DCR suppressor screen.

(A) Congo Red binding phenotype of indicated A. tumefaciens C58 derivative grown on ATGN-CR solid media plus 0.5 mM IPTG, as in Fig. 1C. All strains were constructed in EPS−UPP+ background. In this figure “WT” refers to the EPS−UPP+ strain. (C) Labeling with fl-WGA lectin for UPP production in colonies of the indicated derivatives from ATGN agar plus 0.5 mM IPTG as in Fig. 1A. Arrows highlight lectin labeling on cell poles. All strains were constructed in EPS−UPP+ background, and “WT” refers to this strain.

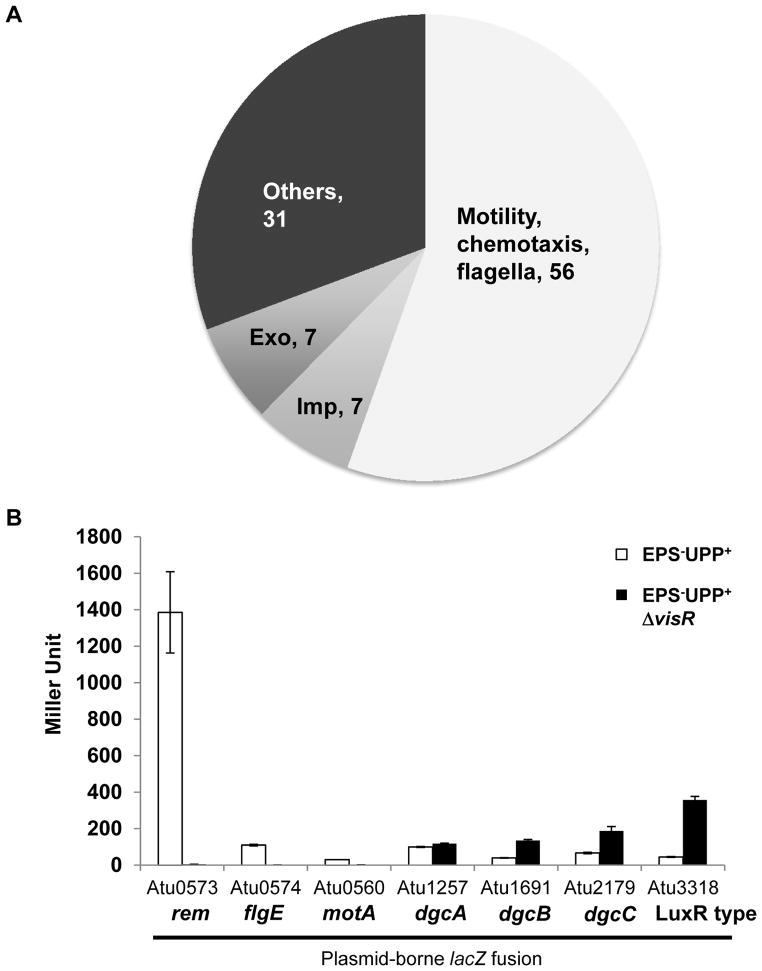

DNA microarray analysis of the VisR transcriptome

To provide additional insights into how VisNR exerts control on biofilm formation and motility, a DNA microarray experiment was performed to compare the transcriptional profile of the ΔvisR mutant and the wild type. Expression data showed that genes with decreased expression in the visR mutant and thus under presumptive VisR positive control included flagellar and chemotaxis genes as well as the transcription factor rem (Rotter et al., 2006), and the imp genes (Wu et al., 2012) encoding a Type VI secretion system (Table S1, Fig. 6A). Although several exopolysaccharide synthesis genes were also down in the visR mutant (Fig. 6A), none of these are UPP or cellulose biosynthetic genes (Xu et al., 2012, Matthysse et al., 1995). A smaller number of genes were increased in expression in the visR mutant and therefore under presumptive VisR-dependent repression (Table S2), including a pair of genes encoding putative DGC proteins, Atu1691 (renamed as dgcB) and Atu2179 (renamed as dgcC). Similar to DgcA, DgcC is predicted to be a membrane-associated protein, whereas DgcB is predicted to be cytoplasmic (Fig. S1). Notably, dgcA expression was not elevated in the ΔvisR mutant.

Figure 6. Identification of VisR regulon by DNA microarray.

(A) Pie chart showing the classification and number of genes with decreased expression in the A. tumefaciens ΔvisR mutant as determined by Agilent DNA microarrays from 4 biological replications and 2 dye swaps. Genes with a t-test P-value < 0.05 and with log2 ratios more negative than −0.6 (representing a fold-change of −1.5) are graphed. (B) β galactosidase specific activity plotting Miller Units from ATGN grown cultures of A. tumefaciens EPS−UPP+ strain (white bars) and the EPS−UPP+ΔvisR mutant (black bars) harboring the indicated plasmid-borne lacZ translational fusions. Values are averages of triplicate assays and error bars are standard deviations.

To confirm the microarray data, plasmid-borne promoter translational fusions with lacZ were constructed with the upstream regions of Atu0573 (rem), Atu0560 (motA) and Atu0574 (flgE), Atu1257 (dgcA), Atu1691 (dgcB), Atu2179 (dgcC), and Atu3318 (encoding a LuxR family protein). These plasmids were introduced into the wild type and the ΔvisR mutant (in both cases the EPS−UPP+ background to avoid large aggregation). Measurement of β-galactosidase activity revealed expression patterns for these lacZ fusions that were wholly consistent with the microarray data (Fig. 6B).

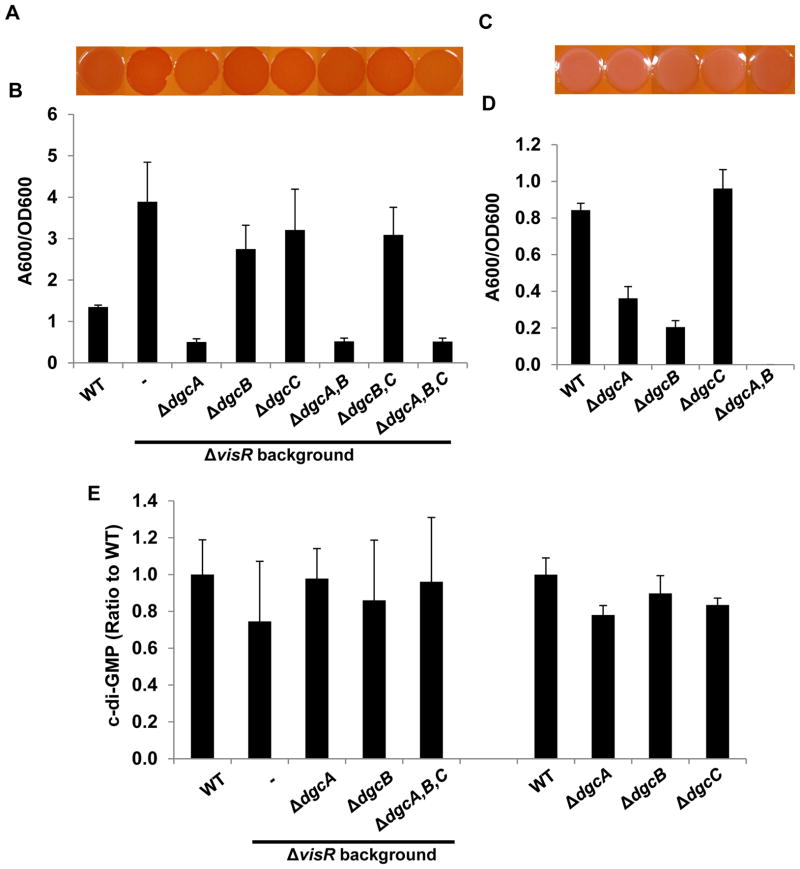

DgcA, DgcB and DgcC proteins contribute to regulation of exopolysaccharides and biofilm phenotypes

Three putative A. tumefaciens DGC (GGDEF) proteins are implicated in the ΔvisR phenotype: dgcA that was isolated from the DCR suppressor screen of the EPS−UPP+ΔvisR mutant, and dgcB and dgcC that were derepressed in the visR mutant. To examine how these three DGC proteins might be integrated to control exopolysaccharide production in the ΔvisR mutant, we constructed single, double and triple dgc deletion mutants in the ΔvisR mutant and the otherwise wild type strain. Deletion of dgcA in the ΔvisR background that also synthesizes the other polysaccharides including cellulose did not abolish elevated Congo Red Binding although this was slightly decreased relative to ΔvisR alone (Fig. 7A). However, deletion of dgcA in the EPS−UPP+ΔvisR background abolished its ECR phenotype (Fig. 5A). This suggests that cellulose is still up-regulated in ΔvisRΔdgcA mutants. The ΔvisRΔdgcB, ΔvisRΔdgcC, and ΔvisRΔdgcBΔdgcC mutants maintained the ECR phenotype (Fig. 7A). Deletion of all three DGC genes together in ΔvisR mutant, however, resulted in Congo Red staining marginally less intense than the ΔvisR mutant, suggesting that DgcA and DgcB are primarily involved in stimulating cellulose and UPP production, but that DgcC may have a modest contribution.

Figure 7. Phenotypic analysis of dgcA, dgcB and dgcC mutants and their contributions to the visR phenotype.

(A) and (C) Congo Red binding phenotypes of indicated A. tumefaciens C58 derivatives as described in Fig. 1C. (B) and (D) Quantitative biofilm assay plotting solubilized crystal violet staining (A600) normalized to culture OD600 at 48 h as described in Fig. 1B. All strains were grown in ATGN medium. Values are averages of triplicate assays and error bars are standard deviation. (E) Measurement of intracellular levels of c-di-GMP in indicated A. tumefaciens C58 derivatives, as described in Fig. 1D. Levels of c-di-GMP for C58 wild type are 50–100 nM and the value for each mutant is represented as a ratio to those measured for the wild type.

In the ΔvisR mutant the ΔdgcA mutation on its own dramatically decreased biofilm formation (Fig. 7B). The ΔvisRΔdgcB, ΔvisRΔdgcC, and ΔvisRΔdgcBΔdgcC mutants maintained elevated biofilm phenotypes similar to ΔvisR (Fig. 7B). Three way mutation of dgcA, dgcB and dgcC in the ΔvisR mutant did not further decrease biofilm formation lower than the ΔvisRΔdgcA mutant. In the wild type, none of the DGC deletions altered its pale Congo Red staining (Fig. 7C). Deletion of either dgcA or dgcB in the otherwise wild type strain resulted in a significant biofilm reduction, whereas the ΔdgcC mutant forms biofilms similar to wild type (Fig. 7D). Biofilm formation of a ΔdgcAΔdgcB double deletion mutant was completely abolished in the wild type background (Fig. 7D), suggesting that both DgcA and DgcB contribute significantly to UPP control and biofilm formation. Complementation of the ΔdgcA mutation or the ΔvisRΔdgcA mutation with a plasmid-borne Plac-dgcA partially restores biofilm formation (Fig. S6A and B). A plasmid-borne Plac-dgcB in the ΔdgcB mutant enhances biofilm formation roughly 3 times above wild type levels (Fig. S6A). Individual deletion of dgcA, dgcB and dgcC did not impact swimming motility nor did ectopic expression of these DGC genes (Fig. S6C).

Plasmid borne lacZ fusions of the dgcA, dgcB and dgcC upstream regions were used to evaluate expression in the static culture conditions of the biofilm assays. All three fusions imparted significant, detectable β-galactosidase activity to otherwise wild type A. tumefaciens (Fig. S6D). Interestingly, the dgcB-lacZ fusion has the weakest relative expression while it manifests the most profound biofilm defect (Fig. 7D).

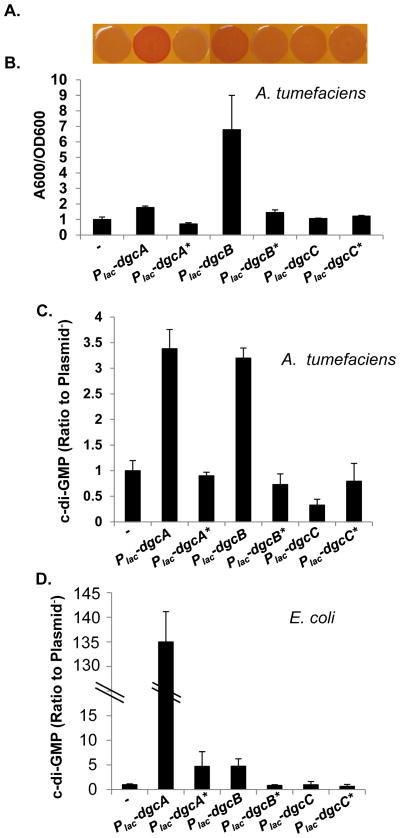

Catalytic site mutation of DGC genes

In order to test whether the dgcA, dgcB and dgcC genes require their GGEEF presumptive catalytic sites (Fig. S1B) to stimulate target phenotypes and drive c-di-GMP synthesis we created plasmid-borne mutant alleles in which the GGEEF motifs were modified to GGAAF. We introduced these plasmids and their wild type counterparts into A. tumefaciens C58. Both the Plac-dgcA and Plac-dgcB plasmids with the unaltered GGEEF motif conferred the ECR phenotype on solid medium with Congo Red (Fig. 8A). While the Plac-dgcA plasmid modestly enhanced the biofilm formation of the wild type strain, the Plac-dgcB plasmid significantly enhanced biofilm formation similarly to when Plac-pleD was expressed ectopically (Fig. 8B). Both of their GGAAF mutant derivatives were greatly diminished for these effects (Fig. 8A and B). In contrast, the Plac-dgcC had no effect in a wild background and not surprisingly, this was similar for the GGAAF mutant allele (Fig. 8A and B). Direct measurement of c-di-GMP levels for A. tumefaciens harboring these plasmids agreed with these phenotypic patterns, with the dgcA and dgcB plasmids driving significant increases in signal concentration, whereas their GGAAF mutants did not (Fig. 8C). Again, neither the wild type nor the GGAAF form of the Plac-dgcC plasmid significantly elevated c-di-GMP levels in A. tumefaciens. These same plasmids were introduced into E. coli DH5α and cytoplasmic c-di-GMP levels were measured (Fig. 8D). The Plac-dgcA and Plac-dgcB plasmids stimulated c-di-GMP levels significantly above the plasmid-free background, whereas these levels in their mutant derivatives with GGAAF mutations were severely decreased. Similar to the observations in A. tumefaciens, neither of the Plac-dgcC plasmids significantly altered the c-di-GMP concentrations (Fig. 8D). These observations provide evidence that DgcA and DgcB are active DGC enzymes and their effect on exopolysaccharide synthesis and biofilm formation is mediated through their ability to catalyze c-di-GMP synthesis. Thus far we have yet to identify conditions under which DgcC is enzymatically active.

Figure 8. Site-directed mutants of putative catalytic sites of DgcA, DgcB and DgcC.

(A) Congo Red binding phenotype of A. tumefaciens C58 wild type strain carrying plasmids as labeled in panel B. All strains were grown on ATGN-CR solid medium plus 0.5 mM IPTG. (B) A quantitative biofilm assay (48 h) for A. tumefaciens C58 wild type strain carrying plasmids as indicated. Cultures were grown in ATGN medium plus 0.5 mM IPTG. Values are averages of triplicate assays and error bars are standard deviation. Plasmids carrying GGEEF to GGAAF site-specific mutations are indicated with an asterisk (*). (C) Measurement of intracellular level of c-di-GMP in A. tumefaciens C58 strain carrying the indicated plasmid, as described in Fig. 1D. Cultures were grown in ATGN medium plus 0.5 mM IPTG. The Y axis represents the ratio of the C58 strain carrying a DGC expression plasmid to the same strain without a plasmid (50–100 nM). (D) Measurement of intracellular levels of c-di-GMP in E. coli DH5α carrying the indicated plasmid, as described in Fig. 1D. Cultures were grown in LB medium plus 0.5 mM IPTG. The intracellular level of c-di-GMP of E. coli DH5α strain is 250–500 nM and normalized to 1. The Y axis represents the ratio of E. coli DH5α strain carrying a plasmid to the same strain without a plasmid.

Average intracellular c-di-GMP levels do not change in visR or DGC mutants

In many ways, the ΔvisR mutant appeared to mimic the phenotypes of strains ectopically expressing pleD. In addition, ectopically expressing dgcA or dgcB in an otherwise wild type strain also resulted in the ECR phenotype, increased attachment and elevated c-di-GMP. All of these effects were dependent on the GGEEF motifs. In light of our findings that these DGCs contribute to the ECR and biofilm phenotype of visR mutant, we hypothesized that similar to ectopic pleD expression, the ΔvisR mutant might lead to elevation of c-di-GMP. Analysis of extracts from the ΔvisR mutant in fact revealed intracellular c-di-GMP levels that were statistically indistinguishable from the parent strain (Fig. 7E). Furthermore, mutation of dgcA, dgcB or dgcC in the wild type or the ΔvisR mutants did not reveal any statistically significant decreases in c-di-GMP pools (Fig. 7E). This was also true for a ΔvisRΔdgcAΔdgcBΔdgcC quadruple mutant (Fig. 7E).

Mutation of a specific dual GGDEF-EAL protein causes dysregulation of UPP synthesis

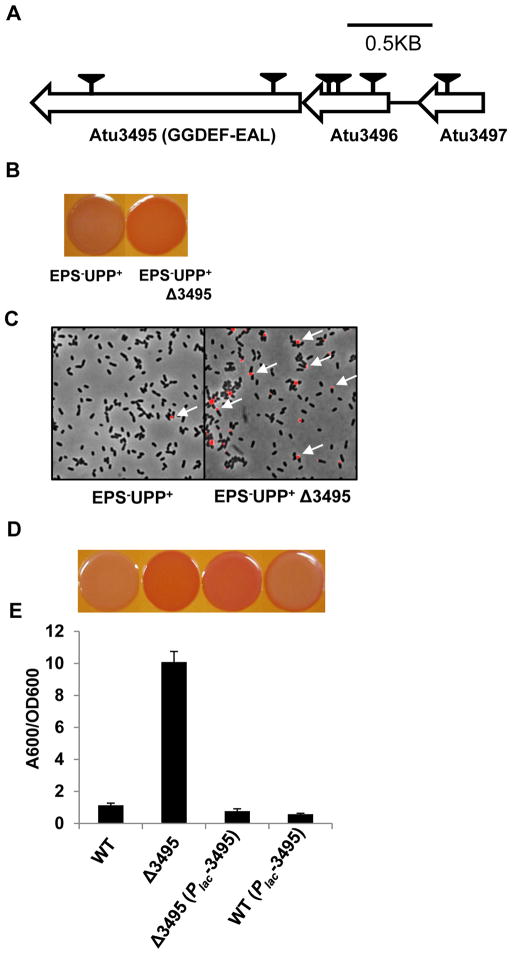

The important role of c-di-GMP in controlling attachment in A. tumefaciens is now clear, at least in part via the VisNR regulation of DgcA and DgcB, and through them, cellulose and UPP. In many bacterial systems, production of c-di-GMP by DGC activity is balanced by degradation of the signal by PDE enzymes. In fact, the last class of A. tumefaciens mutants identified in the original ECR screen (Class ECR4) implicates such a PDE activity. Six independent transposon insertions were isolated in the gene cluster Atu3495–3497 (Fig. 9A). Atu3495 is the last gene in this cluster and encodes a presumptive dual function PDE protein with distinct cytoplasmic GGDEF and EAL domains, and two predicted N-terminal transmembrane segments flanking a periplasmic loop (Fig. S1). Atu3496 and Atu3497 are conserved hypothetical proteins. It seemed likely that the transposon insertions in Atu3496 and Atu3497 were polar on the downstream Atu3495. Targeted deletion of Atu3495 in the EPS−UPP+ parent resulted in the same ECR phenotype as the transposon mutants (Fig. 9B), and this mutant produced a high frequency of fl-WGA-labeled UPP in colonies (Fig. 9C). Similarly, deletion of Atu3495 in a wild type background results in the ECR phenotype and increased biofilm formation (Fig. 9D and E). The mutant is effectively complemented by introduction of a plasmid-borne Plac-Atu3495 (Fig. 9D and E). The Atu3495 mutant phenotype simulates elevated PleD activity and it seems plausible that this may result from loss of its PDE function, thus leading to increased c-di-GMP.

Figure 9. Phenotypic analysis of the putative phosphodiesterase Atu3495.

(A) Genetic map and transposon insertions in Atu3495–Atu3497 genes. Transposon mutants were isolated from a (EPS−UPP+) parent strain, deficient in all major exopolysaccharides except for UPP. Triangles indicate transposon insertion sites isolated from independent transposon insertion events. (B) Congo Red binding phenotype of indicated strains, as described in Fig. 1C. (C) Labeling with fl− WGA lectin for UPP elaboration in colonies, as indicated in Fig 1A. (D) Congo Red binding phenotypes of A. tumefaciens C58 derivatives as labeled in panel E, and all grown on ATGN-CR solid media plus 0.5 mM IPTG. (E) A quantitative biofilm assay plotting solubilized crystal violet staining (A600) normalized to culture OD600 by the indicated A. tumefaciens derivatives at 48 h, as described in Fig. 1B. All strains were grown in ATGN medium plus 0.5 mM IPTG. Values are averages of triplicate assays and error bars are standard deviation.

Discussion

During surface colonization, motile bacteria must transition from an active swimming mode to an attached sessile existence. A significant component of this transition is a change in synthesis of surface polysaccharides (Branda et al., 2005). Consistent with our prior work (Xu et al., 2012), we provide evidence here that production of UPP is required for productive surface interactions in the wild type and in hyper-biofilm forming mutants. Cellulose can contribute to increased biofilm formation, particularly in strains that over produce it, but under laboratory conditions mutants unable to synthesize cellulose adhere to abiotic surfaces equivalently to the wild type. Our findings are consistent with the general observation that c-di-GMP regulates polysaccharide synthesis (Ryan et al., 2006), with elevated levels of the signal through the activity DGC genes (such as pleD, dgcA or dgcB) stimulating cellulose and UPP synthesis, and thus promoting attachment and subsequent biofilm formation. The activities of DGC and PDE enzymes are required to control these processes, but do not necessarily alter overall c-di-GMP levels in A. tumefaciens.

Regulation of surface-dependent UPP production and attachment

Initial surface association often begins with a reversible binding step, mediated by flagella and pili (O’Toole & Kolter, 1998, Merritt et al., 2007), followed by a more permanent attachment that coincides with production of one or more exopolysaccharides (Xu et al., 2012, Berk et al., 2012, Colvin et al., 2012). For Caulobacter crescentus, reversible surface contact stimulates the just-in-time production of the holdfast adhesive, produced at the tip of this bacterium’s stalk (Li et al., 2012). Similarly, production of the UPP polar adhesin in A. tumefaciens is also dependent on surface contact. Time-lapse total internal reflectance fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy with fluorescently tagged lectin revealed that A. tumefaciens deploys the UPP very rapidly, as early as several minutes upon surface binding (Li et al., 2012). Although few if any isolated planktonic A. tumefaciens cells produce UPP, a majority of them elaborate UPP after they bind to surfaces, either biotic (other cells, plant roots, etc) or abiotic. A. tumefaciens is apparently recognizing the consequences of intimate surface contact and as with C. crescentus, responding by transitioning to the stably adherent state.

How might A. tumefaciens sense solid surfaces to drive irreversible attachment and proceed forward to biofilm formation? In C. crescentus production of the holdfast can be stimulated by the addition of chemical agents that cause polymer crowding and impede the rotation of the flagellum (Li et al., 2012). Arguably the best-studied system is Vibrio parahaemolyticus in which surface contact is sensed via impeded rotation of a single polar flagellum, which activates production of a lateral flagellar (Laf) system that mediates the transition from swimming to swarming (McCarter et al., 1988, McCarter & Silverman, 1990). Molecular genetic analyses have identified several of the key regulators that are required to control this process in V. parahaemolyticus, but the mechanism by which flagellar rotation is coupled to Laf system activation has remained elusive. In A. tumefaciens, mutants that block flagellar assembly are not affected for the timing or production of UPP (Xu et al., in preparation). There are now many studies showing that elevated c-di-GMP promotes sessility and biofilm formation (Ryan et al., 2006), although our findings provide the first evidence that aberrantly elevated c-di-GMP decouples the control of adhesin synthesis from surface contact. We propose that during normal A. tumefaciens surface colonization, a consequence or attribute of surface contact stimulates an increase of c-di-GMP through DGC activity (and possibly decreased PDE activity), thus elevating adhesin production and eventually driving biofilm formation. The apparent co-regulation of UPP and cellulose by c-di-GMP also suggests synergistic roles for these exopolysaccharides during adherent growth, with UPP providing polar surface binding and cellulose bridging cells within developing biofilms or aggregates.

Inverse control of motility and attachment via VisN and VisR

We have found that A. tumefaciens controls production of UPP and cellulose at least in part through the VisN-VisR transcriptional regulators, previously found to activate flagellar assembly in the rhizobia (Sourjik et al., 2000). VisN and VisR thus are well positioned at the fulcrum between motility and sessility, and exert an inhibitory influence on production of both the UPP and cellulose (Fig. 10). As in S. meliloti, our genetic analysis suggests that VisN and VisR function together, but that each is required for regulation. Mutations in visN or visR in A. tumefaciens decouple UPP production from surface dependence and ectopic expression of these regulators can severely suppress UPP production, preventing surface attachment. Microarray analysis of the ΔvisR mutant revealed the decreased expression of several exopolysaccharide synthesis genes (most involved in succinoglycan biosynthesis) in ΔvisR, but none of the recognized UPP and cellulose biosynthesis genes were affected by the ΔvisR mutation. As predicted by the microarray data, synthesis of the exopolysaccharide succinoglycan (SCG) is significantly decreased in the visR mutant and is inhibited at high levels of c-di-GMP (Xu et al., in preparation). Differences in colony muciody also reflect this pattern as A. tumefaciens derivatives with elevated UPP and cellulose form dry, non-mucoid colonies (for examples see Fig. 1C, S2B and others)

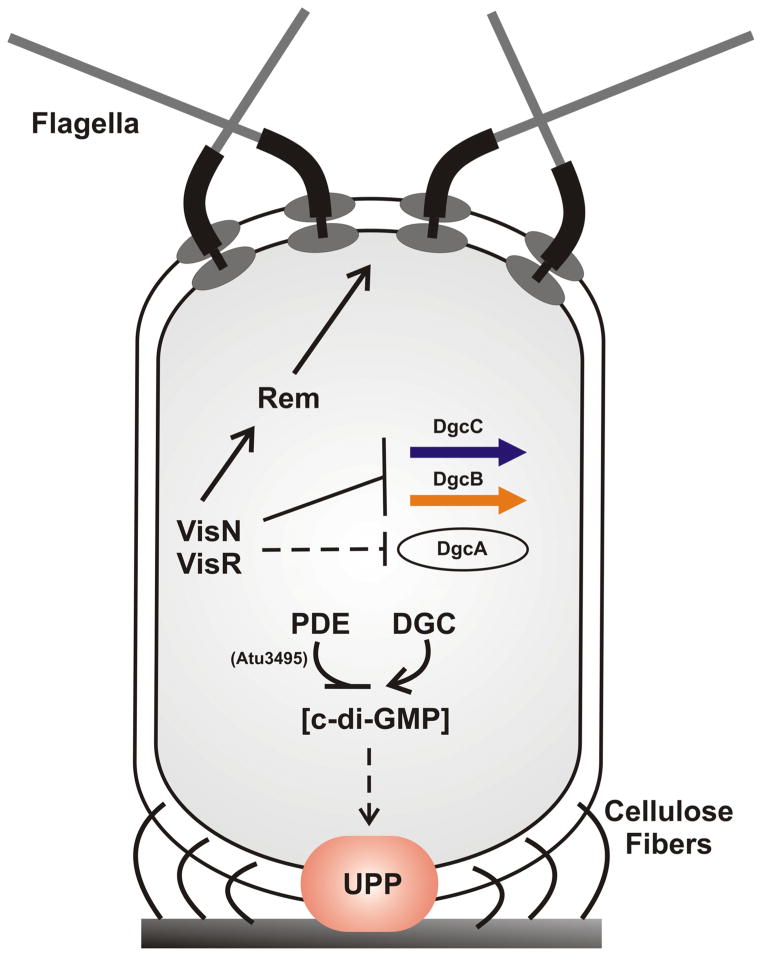

Figure 10. Working model of VisN-VisR and c-di-GMP regulation of motility and polysaccharide synthesis.

The turnover of c-di-GMP, which is controlled by phosphodiesterase EAL proteins and diguanylate cyclase GGDEF proteins, positively regulates the production of UPP (indicated by orange ellipse) and cellulose fibers (indicated by the curved lines). Cells with elevated c-di-GMP elaborate the UPP independent of surface contact. VisNR negatively regulates UPP and cellulose through modulating the c-di-GMP levels via the diguanylate cyclases DgcA, DgcB and perhaps DgcC. VisN-VisR directly or indirectly regulates the transcription of dgcB and dgcC, while directly or indirectly regulating dgcA post-transcriptionally. VisNR regulates motility and flagellar function through the Rem transcriptional activator, as in S. meliloti.

In S. meliloti VisN-VisR activate expression of the transcription factor called Rem, a two-component-type response regulator with no known cognate histidine kinase (Rotter et al., 2006). Rem is the direct activator of many of the class II and class III flagellar genes and S. meliloti rem mutants are aflagellate. One of the most dramatically decreased genes in the A. tumefaciens ΔvisR mutant is rem, consistent with a similar regulatory architecture for flagellar assembly control as in S. meliloti. It is plausible that the impact of visN and visR mutations on UPP and cellulose production is also indirect through their control of rem expression. A simple prediction of this model, would be for rem mutants to phenocopy visN and visR mutants, but this is not the case in A. tumefaciens (Fig. 10), and our preliminary findings suggest that VisN-VisR-dependent control of adhesive polysaccharides is distinct from their control of flagellar assembly through Rem (Xu et al., in preparation)

Control of UPP and cellulose through c-di-GMP and specific DGCs

Levels of c-di-GMP have a profound influence on the attachment process in A. tumefaciens, consistent with findings in other bacteria (Hengge, 2009). The observed dysregulated UPP production and enhanced attachment of visNR mutants are highly dependent on a specific diguanylate cyclase protein, DgcA. Although two other GGDEF proteins, encoded by dgcB and dgcC are shown here to be within the VisR regulon and contribute to the ECR phenotype of the ΔvisR mutant, DgcA plays the dominant role in the visR mutant. However, VisR does not influence the transcription of dgcA and thus we presume that this control is indirect through an additional target gene(s) the product(s) of which ultimately controls DgcA post-transcriptionally or regulates a downstream effector dependent on DgcA. Interestingly, DgcB apparently plays an equally important role in the wild type, with both dgcA and dgcB required for normal UPP-dependent attachment. For most of the DGC proteins analyzed in this study, mutation of their GGEEF motifs to GGAAF resulted in a loss of function. PleD, DgcA and DgcB require this motif to drive c-di-GMP synthesis when expressed in E. coli, and also in A. tumefaciens. Correspondingly, they also require these presumptive catalytic residues to control output phenotypes such as UPP production and cellulose synthesis. This is strong evidence that these outputs are affected by c-di-GMP produced by these proteins. Despite its parallel regulation by VisR we have yet to detect DGC activity for the dgcC gene product. Mutations in this gene also have little if any effect on any of the output phenotypes we have measured. Its putative GGEEF motif is not notably different from dgcA and dgcB and it may be that its activity is controlled by an environmental stimulus absent in our culture conditions. There are also examples of GGDEF proteins that do not function as enzymes but are instead regulated by c-di-GMP (Sondermann et al., 2012), and it is possible that dgcC is not an active DGC.

Given that allosteric control of polysaccharide biosynthetic machinery by c-di-GMP is well established (Merighi et al., 2007, Weinhouse et al., 1997, Lee et al., 2007), it is plausible that the regulation of the GGDEF proteins by VisR imparts direct control on the synthesis of cellulose and UPP. The CelA protein contains a recognized PilZ-type domain, a likely binding site for c-di-GMP (Schirmer & Jenal, 2009). Our results suggest that mutants in visR and visN are elevated for cellulose via the activity of one or more of the DGCs (dgcA, dgcB, and dgcC) we have identified. The simplest model is that c-di-GMP synthesized by these proteins (artificially simulated when the PleD DGC is ectopically expressed), activates cellulose synthesis via interaction with the CelA PilZ domain, although more complex models are also plausible.

We hypothesize that the rapid and surface-dependent deployment of the UPP is also allosterically regulated by c-di-GMP. A. tumefaciens only encodes two PilZ domain-containing proteins in addition to CelA, but neither of these have an impact on UPP production (Xu and Fuqua, unpublished results). However, there are several distinct c-di-GMP response mechanisms in addition to the activity of PilZ domains, including other protein domains that bind the signal (Hickman & Harwood, 2008, Krasteva et al., 2010) and a c-di-GMP-dependent riboswitch (Sudarsan et al., 2008). Several of the proteins with these c-di-GMP binding domains are transcriptional regulators, and given that VisN and VisR are LuxR-FixJ-type transcription factors, but have atypical N-terminal domains it is plausible that a presumptive VisNR heterodimer might bind to c-di-GMP. If this were the case we would predict that this interaction would inactivate VisNR, and thereby relieve a repressive effect on UPP production, as well as block activation of rem and biosynthesis of flagella. However, the elevated UPP phenotype of the ΔvisR mutant requires the activity of dgcA, and its ability to synthesize c-di-GMP. Thus any interaction of c-di-GMP with VisNR that might exist does not explain the increased production of UPP in the visR mutant. Moreover, expression analysis failed to identify the elevated expression of any UPP biosynthesis genes in the ΔvisR mutant, which seems to rule out a simple transcription control model. We suspect that analogous to cellulose synthesis, c-di-GMP regulates one or more of the rate-limiting steps of UPP synthesis through direct interactions with the biosynthetic machinery. Recent studies in E. coli have revealed direct c-di-GMP regulation of poly-N-acetyl glucosamine (PAG) synthesis by binding to a biosynthetic enzyme, promoting its productive interaction with other components of the biosynthetic machinery (Steiner et al., 2012).

Integration of c-di-GMP signaling in A. tumefaciens

There are 31 gene products with putative GGDEF domains in the A. tumefaciens C58 genome, 16 of which also carry annotated EAL domains (Goodner et al., 2001, Slater et al., 2009). How those GGDEF and EAL proteins integrate together to produce coherent, discrete output signals remains unclear. Although UPP control in wild type A. tumefaciens appears to be mediated primarily through dgcA and dgcB, this can be overridden by ectopic expression of pleD, dramatically increasing cytoplasmic levels of c-di-GMP. This in turn leads to increased production of cellulose and the UPP, and consequently to increased attachment, aggregation and biofilm formation. The mutants for visN and visR recapitulate the effect of pleD ectopic expression, but these phenotypes are not dependent on PleD, and rather on DgcA. In striking contrast to cells with high levels of PleD, the c-di-GMP levels in the ΔvisR mutant are not significantly different from wild type. Despite the clear role of dgcA in UPP production in the ΔvisR mutant, only simultaneous mutation of dgcA, dgcB, and dgcC decreases cellulose-dependent Congo Red staining. None of the dgc deletion mutants are impacted for their average levels of intracellular c-di-GMP. These observations are in agreement with a number of recent studies in which the cytoplasmic levels of c-di-GMP fail to correlate with specific targeted phenotypes. In P. aeruginosa two DGC proteins, SadC and RoeA predominantly regulate distinct target functions (motility and polysaccharide synthesis, respectively), and in both cases control requires their catalytic GGDEF/GGEEF motif, indicating the requirement for c-di-GMP (Merritt et al., 2010). However, cellular levels of c-di-GMP do not correlate with changes in the DGC-regulated phenotypes, leading to the proposal that the targets which control these phenotypes only perceive the c-di-GMP synthesized by a specific DGC enzyme(s), and that the signal is somehow compartmentalized, not contributing to the average cytoplasmic signal concentration. Likewise, studies in E. coli suggest that the oxygen-responsive DGC/PDE pair DosC and DosP form a complex with their target enzyme, polynucleotide phosphorylase, and control its activity through localized synthesis and degradation of c-di-GMP (Goodner et al., 2001). It is however clear that compartmentalization of c-di-GMP signaling is not the only way to achieve specificity, as in V. cholerae the VpsT transcription factor responds to c-di-GMP synthesized by five different DGCs and these can act on VpsT from a distance (Hengge, 2009). We did not observe global changes in the levels of c-di-GMP in the A. tumefaciens visR mutant, although its phenotype requires dgcA and its GGEEF motif. Our findings suggest that increases in c-di-GMP for this mutant may occur in a localized fashion, potentially at the cell pole where UPP is synthesized.

Experimental procedures

Reagents, strains and growth conditions

All strains, plasmids and oligonucleotides used in this study are provided in the Supplementary Materials, Tables S3 and S4, respectively. The E. coli strains used for plasmid DNA transformation or conjugation of plasmids were grown in LB broth (Difco Bacto tryptone at 10 g liter−1, Difco yeast extract at 10 g liter−1, and NaCl at 5 g liter−1, pH 7.2) with or without 1.5% (w v−1) agar. Unless noted otherwise, the A. tumefaciens strains were grown on either LB or AT minimal medium (Tempe et al., 1977) supplemented with 0.5% (wt vol−1) glucose and 15 mM ammonium sulfate (ATGN). To prevent the accumulation of iron oxide precipitate, the FeSO4 prescribed in the original AT recipe was omitted, with no adverse growth effect. However, for biofilm cultures, 22 μM FeSO4·7H2O was added to ATGN medium immediately before. For sacB counter-selection, 5% sucrose (Suc) replaced glucose as the sole carbon source (ATSN). Chemicals, antibiotics, and culture media were obtained from Fisher Scientific and Sigma-Aldrich. When required, appropriate antibiotics were added to the medium as follows: for E. coli, 50 μg ml−1 ampicillin, 25 μg ml−1 gentamicin (Gm), 50 μg ml−1 kanamycin (Km) and 100 μg ml−1 spectinomycin; and for A. tumefaciens, 300 μg ml−1 gentamicin, 150 μg ml−1 Km, and 200 μg ml−1 spectinomycin. Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) was used when necessary. For Congo Red plates, the dye was dissolved in methanol at 20 mg/ml, and passed through 0.2 μm syringe filters immediately before use to remove aggregates. Four ml filtered Congo Red was added per L (final ~80 μg/ml) to generate ATGN-CR agar medium.

Transposon mutagenesis

The mariner minitransposon Himar1 was used to mutagenize A. tumefaciens C58 (Lampe et al., 1999). Fully turbid LB-broth cultures of the donor E. coli SM10/λpir pFD1 (Himar1) and A. tumefaciens, were inoculated at a 1:10 dilution in 2 mls of LB broth and incubated 4 h at 37°C and 27°C respectively. From each culture 1 ml was removed and cells were collected by centrifugation (6,000 × g) and resuspended in 50 μl of LB. From each cell suspension 50 μl were mixed together and this entire mixture was spotted on 0.2 μm cellulose acetate filters on a LB plate without antibiotics. After the inoculant soaked in, these plates were incubated overnight at 28°C to allow mating. Following incubation, cells were suspended off the filter into 1 ml sterile 30% glycerol, and then, aliquots serially diluted (10−1–10−5) with 100 μl plated on Congo Red ATGN media with appropriate levels of Km, followed by incubation at 28°C. The unused mating mixture was frozen at −80°C for subsequent platings, as necessary.

Touchdown PCR and sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from Mariner mutagenized A. tumefaciens derivatives using a Wizard Genomic DNA purification kit (Promega Corp.). The genomic DNA concentration was measured using a NanoDrop 1000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). Touchdown PCR was performed using 80–120 ng genomic DNA with primers MarRSeq and MarTDL2 pair or MarLSeq and MarTDR1 pair (Table S4), and NEB High Fidelity Phusion polymerase, followed with a standard Touchdown PCR program [(i) 54 min, 95 °C, (ii) 24 cycles, 95 °C for 45 sec, 60 °C for 45 sec decreasing by 5 degrees with each cycle, 2 min at 72 °C, and (iii) 24 cycles, 95 °C for 45 sec, 60 °C for 45 sec, 2 min at 72 °C]. PCR reactions that yielded one or several strong bands were purified using Qiagen Qiaquick purification kit and used as template for cycle sequencing using the Big Dye reagent, primers MarRSeq or MarLseq and the recommended protocol in the Indiana Molecular Biology Institute.

UPP production assays

The UPP was visualized as described using wheat germ agglutinnin (WGA) labeled with Alex Fluor 594 (Invitrogen). A. tumefaciens were grown in ATGN to an optical density of approximately 0.6 at 600 nm (OD600). A 1 ml aliquot of culture was centrifuged (6,000 × g) and pelleted cells were resuspended in 100 ATGN. To visualize the production of UPP in standard colonies on agar, these were picked with a sterile toothpick and suspended in 100 μl ATGN. In both cases, 1μl labeled WGA stock solution (1 mg ml−1) was added to 100 μl of the suspension and incubated for 20 min. Bacteria were collected by centrifugation (6,000 × g) and washed twice by ATGN medium. A small volume of the cell suspension was dispensed on an agar pad (1.5 % agar, 150 μl) solidified on a microscopic slide, just prior to application of a coverslip. Samples were observed by fluorescence microscopy (Nikon E800) using a 100× oil immersion objective and NIS-Elements software.

Cultivation and analysis of static culture biofilms

Biofilms were grown in static culture essentially as described previously (Merritt et al., 2007). Briefly, sterile polyvinyl chloride (PVC) coverslips were placed vertically in 12-well polystyrene cell culture plates (Corning Inc.), inoculated with cells in ATGN at an OD600 of 0.05, and incubated at room temperature for 48 h. For CV visualization, coverslips were rinsed in double-distilled H2O, stained with 0.1% (wt vol−1) CV for 10 min, and rinsed again in double-distilled H2O. CV-stained biomass adhered to the coverslip was quantified by soaking stained coverslips in 1 ml of 33% acetic acid to solubilize the CV, followed by absorbance measurement of the soluble stain at 600 nm (A600) in a Bio-Tek Synergy HT microplate reader. Absorbance values were normalized to culture growth by dividing the A600 value for solubilized CV by the OD600 value of the planktonic culture.

Expression analysis using DNA microarrays

A. tumefaciens C58 specific microarrays created with custom 60mer oligonucleotides were purchased from Agilent Technologies. RNA was extracted with the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Transcriptional profiling was carried out as follows with 20 mg of purified RNA used for cDNA synthesis. First strand labeling and reverse transcription was performed using Invitrogen SuperScript Indirect Labeling Kit, and cDNA was purified on Qiagen QIAQuick columns. cDNA was labeled with AlexaFluor 542 and 655 dyes using Invitrogen SuperScript cDNA Labeling Kit, and repurified on QIAQuick columns. The yield and purity of cDNA was quantified on a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. Hybridization reactions were performed using an Agilent in situ Hybridization Kit Plus. Equivalent amounts of labeled cDNA preparations were mixed 50/50, boiled for 5 min at 95°C, applied to the A. tumefaciens C58 custom microarrays, and hybridized overnight at 65°C. Hybridized arrays were washed with Agilent Wash Solutions 1 and 2, rinsed with acetonitrile, and incubated in Agilent Stabilization and Drying Solution immediately prior to scanning the arrays. Four independent biological replicates were performed for comparison of the wild type and the ΔvisR mutant, with dye swaps. Hybridized arrays were scanned on a GenePix Scanner 4200. Scanned images were processed by the LIMMA package in Bioconductor, correcting for background with the minimum method, normalizing within arrays with the LOESS method, and between arrays with the quantile method. Linear model fitting and empirical Bayesian analysis was performed by least squares, and dye swap effect correction. Gene lists were created using a t-test P-value < 0.05 and with log2 ratios of ≥ 0.6 or ≤ −0.6 (representing a fold-change of ± 1.5) are reported here. Microarray data is deposited into the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/)

Electron microscopy

Electron microscopy was performed in the Indiana Molecular Biology Institute Microscopy Center. For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), 10 ul 1% poly L-lysine was added to the surface of a disk-shaped glass coverslip for 5 min to make the surface adhesive. The coverslip was rinsed with water, and 10 μl of culture (OD600 0.6) was added to the coverslip surface for 5 min and absorbed by filter paper. Bacteria remaining on the coverslip were fixed with 10 μl 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.2 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.2) for 5 min. Bacteria on coverslips were dried by treatment with a series of increasing ethanol solutions (30%–100%). These coverslips were further dried in an atmosphere saturated with absolute ethanol and then dehydrated with acetone and dried with CO2 using the critical point method. The samples were sputter coated with gold and observed by a JEOL JSM-5800 LV Scanning Electron Microscope at 10 kV.

For Immuno-gold Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), 1 ml of culture (OD600 0.6) was centrifuged and resuspended in 200 μl ATGN, to which 5 μl 20 nm colloidal gold conjugated WGA (20 μg/ml WGA, purchased from EY laboratories) was added and incubated 20 min. The bacterial suspension was centrifuged (6,000 × g) and the pelleted material was washed twice with 1 ml ATGN and resuspended in 200 μl ATGN. 10 μl of bacterial suspension was applied to carbon-coated grids for 5 min and stained with 10 μl 1% uranyl acetate 5 min. Excess uranyl acetate was removed using filter paper and the grid was air dried for 5 min. The grid was then examined using the JEOL JEM-1010 Transmission Electron Microscope at 80 kV.

Motility assays and flagellar staining

Motility plates were performed using 100-mm petri plates with 25 ml ATGN medium containing 0.3% Bacto agar (BD). Motility plates were inoculated with 5 μl of fresh cultures (OD600=0.6) at the center of the plate, plates were incubated for up to six days at room temperature, and the swim ring diameter was measured daily.

Flagella were stained using a two-component stain and protocol adapted from Mayfield and Inniss (Mayfield & Inniss, 1977). Solution A is equal volumes 5% phenol and saturated AlK(SO4)2 12H2O in 10% tannic acid, and solution B is 12% crystal violet (CV) in 100% ethanol. Solutions A and B were mixed fresh with 10 volumes of A added to 1 volume of B, vortexed, and centrifuged to remove CV crystals. A small volume of bacterial culture (~3 μl) was spotted onto a clean microscope slide and overlaid with a 22 × 22-mm coverslip. The slides were held vertically, and approximately 2 to 5 μl of the AB stain solution was applied to the edge of the coverslip, allowing capillary action to wick the stain under the coverslip. Samples were observed by phase-contrast microscopy using a 100× oil immersion objective after at least 5 min of staining.

c-di-GMP measurement

Cultures of A. tumefaciens derivatives were grown in ATGN medium (plus 0.5 mM IPTG if needed) at 28°C to OD600 of 2.0, and used to perform viable counts to determine CFUs/ml. Cultures of E. coli DH5α derivatives were grown in LB (plus 0.5 mM IPTG if needed) at 37°C to OD600 of 0.6–0.8. 30 ml of culture was centrifuged for 3 min at 10,000 × g at 25°C. The pellet was immediately resuspended in 250 μl extraction buffer (methanol/mcetonitrile/dH2O 40:40:20 + 0.1 N formic acid cooled at −20°C) by vigorous vortexing and pipetting. The extractions were incubated at −20°C for 30 min, followed by transfer to a new microfuge tube on ice. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 10,000 × g 5 min at 4°C, and 200 μl of supernatant was transferred into a new tube on ice. Samples were neutralized within 1 hr of preparation by adding 4 μl of 15% NH4HCO3 per 100 μl of sample, aimed to set a pH of 7 ~ 7.5.

Prior to analysis, the sample was subjected to vacuum centrifugation to remove the extraction buffer and resuspended in an equal volume of water. Ten μL of each sample was then analyzed using liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) on a Quattro Premier XE mass spectrometer (Waters Corporation) coupled with an Acquity Ultra Performance LC system (Waters Corporation). C-di-GMP detection and quantification was performed as previously described (Massie et al., 2012). To calculate the c-di-GMP concentration, chemically synthesized c-di-GMP (Biolog) was dissolved in water at concentrations of 250, 125, 62.5, 31.2, 15.6, 7.8, 3.9, and 1.9 nM and analyzed using LC-MS/MS to generate a standard curve.

Construction of in-frame markerless deletions

Construction of nonpolar deletion was performed as reported previously (Merritt et al., 2007). Briefly, PCR was used to amplify approximately 500 to 1,000 bp of flanking sequence upstream (primers 1 and 2) and downstream (primers 3 and 4) of the reading frame targeted for deletion. Primers were designed to remove as much of the coding sequence as possible without disrupting any possible translational coupling. Primers 2 and 3 were designed with 18-bp complementary sequences at their 5′ ends (lowercase nucleotides in Table S4) to facilitate splicing by overlapping extension (SOE), essentially as described previously (Merritt et al., 2007). Briefly, both flanking sequences were amplified using the high-fidelity Phusion DNA polymerase (NEB) and were agarose gel purified. Purified PCR products were used as both templates and primers for a five-cycle PCR. A final PCR step with primers 1 and 4, using 2 μl of the second-step reaction mix as the template, generating the full-length spliced product. The final PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T Easy (Promega), confirmed by sequencing, excised by cleavage with the appropriate restriction enzymes, and ligated with the suicide vector pNPTS138 cleaved at compatible restriction sites. The pNPTS138 plasmid confers Km resistance (KmR) and sucrose sensitivity (Sucs). Derivatives of pNPTS138 were introduced into A. tumefaciens C58 by electroporation. The ColE1 origin of pNPTS138 does not replicate in A. tumefaciens, and therefore the plasmid must recombine into the genome, to allow growth of transformants on media containing Km. Recombinants were selected on ATGN plates containing KmR, and plasmid integration was confirmed by patching KmR isolates onto ATSN-Km plates to identify SucS derivatives. To facilitate excision of the integrated plasmid, KmR SucS clones were grown overnight in ATGN broth without KmR and then plated on ATSN. Plasmid excision was verified by patching SucRclones onto ATSN plus Km to identify KmS derivatives. Appropriate deletion of the target genes was confirmed by diagnostic PCR and DNA sequencing of the products.

Controlled expression plasmids

To perform complementation analyses, wild-type coding sequences were cloned into the LacIQ encoding, IPTG-inducible expression vector pSRKKm or pSRKGm (Khan et al., 2008). Coding sequences were PCR amplified from C58 genomic DNA, using the corresponding primers for each gene (Table S4) and the Phusion polymerase. Amplicons were ligated into pGEM-T Easy, confirmed by sequencing, excised by restriction enzyme cleavage, and ligated with appropriately cleaved pSRKKm or pSRKGm. Plasmid derivatives harboring the correct inserts were verified by restriction digestion and sequencing prior to electroporation into competent A. tumefaciens cells.

Catalytic site mutations for PleD, DgcA, DgcB and DgcC

These site-specific mutants were generated by PCR SOEing with mutagenic primers. Mutagenesis of pleD is an example. Complementary primers pairs (pleD*-P1 and pleD*-P2) were designed with GGEEF mutated to GGAAF by altering the corresponding nucleotides in the internal primers. The first round of PCR reactions were performed by using primer pairs (Com-pleD-P1 and pleD*-P2) and (Com-pleD-P2 and pleD*-P1) separately to amplify the sequences from C58 genomic DNA. Amplicons from the previous two PCR reactions were gel purified and added as the template for the second round of PCR by using Com-pleD-P1 and Com-pleD-P2. The amplicons from the second round of PCR were gel purified, excised by restriction enzyme cleavage and ligated with appropriately cleaved pSRKGm. Plasmid derivatives harboring the correct inserts were verified by restriction digestion and sequencing prior to electroporation into competent A. tumefaciens cells. Catalytic site mutations for DgcA, DgcB and DgcC were constructed by the same approach.

β-Galactosidase assays and lacZ fusions

Fragments containing the promoter elements upstream of Atu1257, Atu1691, Atu2179, Atu3318, Atu0560, Atu0573 and Atu0574 were amplified from A. tumefaciens genomic DNA using Phusion DNA polymerase and primers 1 and 2 (see Table S4). PCR fragments were agarose gel purified, ligated into pGEM-T Easy, and verified by sequencing. Fragments were excised with the appropriate restriction enzymes and ligated into the compatibly cleaved vector pRA301. Fragments were designed to insert the promoter region and ribosome binding site with the start codon of the gene of interest in frame with the promoterless lacZ gene. Fragments were confirmed by PCR, and the constructs were electroporated into A. tumefaciens wild-type and mutant derivatives.

Cultures were prepared for β-galactosidase assay by culturing in ATGN into exponential phase measured for OD600 and frozen at −80°C. The β-galactosidase activity of the cultures was assayed as described previously (Hibbing & Fuqua, 2011). Briefly, cells were permeabilized in Z-buffer (0.06 M Na2HPO4, 0.04 M NaH2PO4, 0.01 M KCl, 0.001 M MgSO4, 0.05 M β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.0) by the addition of 3 drops of 0.05% SDS and 4 drops of chloroform. β-galactosidase reactions were initiated by addition of 100 μl of a 4 mg ml-1 solution of the colorimetric substrate o-nitrophenyl β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG) and terminated with addition of 600 μl of 6 M NaCO2. Intact cells and debris were removed by centrifugation (10 min, 10,000 × g) and free ONP was measured as A420 and specific activity was reported in Miller Units. At least 3 biological replicates were performed.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Annotated domain structures of PleD, DgcA, DgcB, DgcC and Atu3495 in A. tumefaciens. (A) Domain structures were obtained and modified from http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de. PleD contains two putative REC response regulator signal receiving domains and one putative GGDEF domains. DgcA and DgcC contain several putative transmembrane domains and one putative GGDEF domain. DgcB contains one putative GGDEF domain. Atu3495 is annotated with two transmembrane domains, one GGDEF domain and one EAL domain. (B) Amino acid sequence alignments of predicted GGDEF domains of PleD (Atu1297), DgcA (Atu1257), DgcB (Atu1691), DgcC (Atu2197) and Atu3495 using ClustalW2. The black rectangle highlights the conserved “GGEEF” motifs. The red rectangle highlights the positions of putative c-di-GMP inhibitory sites or I box “RXXD”. Asterisks mark completely conserved positions, colons indicate partial conservation and periods are chemically similar residues.

Figure S2. Congo Red binding phenotypes of EPS mutants. (A) Labeling with fl-WGA lectin for UPP production in planktonic cultures of the indicated strains grown in ATGN liquid medium plus 0.5 mM IPTG. Cultures with OD600 0.6–0.8 were harvested and stained by WGA, followed by fluorescence microscopy as described in Fig. 1A. (B) Systematic analysis of Congo Red binding phenotype of different EPS mutants. Colonies were growing on ATGN-CR plates with (bottom row) and without (upper row) 0.5 mM IPTG. The EPSs for which targeted mutants were generated were succinoglycan (SCG, mutated for exoA, Atu4053, the glycosyl transferase thought to add the first glucose residue in each subunit), cellulose (deletion of the entire celABCDEG cluster, Atu8187-Atu3302), β-1, 2-glucans (deletion of the chvAB operon, Atu2728–2730, the synthase and transporter), β-1, 3-glucans (also known as curdlan, deleted for the curdlan biosynthesis genes, Atu3055–Atu3057, including the presumptive polysaccharide synthase CrdS), and UPP (deleted for the uppABCDEF gene cluster Atu1235–1240, required for UPP synthesis (Xu et al., 2012, Römling, 2002, Stasinopoulos et al., 1999, Cangelosi et al., 1989, Cangelosi et al., 1990, O’Connell & Handelsman, 1989).

Figure S3. Genetic screening approaches employed in this study. (A) Two genetic screens were implemented: (i) a screen to identify mutants with elevated Congo Red (ECR) staining due to increased UPP production and (ii) a suppressor screen using an existing ECR mutant to identify mutants with decreased Congo Red (DCR) staining due to decreases in UPP synthesis. In the ECR screen, we utilized an EPS−UPP+ A. tumefaciens parent, a strain deficient in production of all major exopolysaccharides except UPP. In the DCR screen, we utilized the ECR mutant, the same EPS−UPP+ derivative that also carries the ΔvisR deletion, as the parent strain. The yellow circle represents colonies with low Congo Red binding when growing on ATGN-CR solid medium. The red circle represents colonies with elevated Congo Red binding on ATGN-CR solid medium. (B) Cartoon representing the UPP staining patterns of cells from the colonies in panel A. Rods are A. tumefaciens cells and red circles with orange center indicate the UPP production of cells. Similar patterns are also observed when cells are growing in planktonic phase. (C) UPP staining of representative ECR mutant classes identified from the genetic screen. Labeling with fl-WGA lectin for UPP production in colonies of indicated derivatives grown on ATGN solid medium, as described in Fig. 1A. ECR1–4 indicates examples of ECR mutants with Himar1 insertions. ECR1: interrupted for Atu0525 (visR); ECR2: interrupted for Atu1130; ECR3: interrupted for Atu1631; ECR4: interrupted for Atu3495. Arrows highlight lectin labeling on cell poles.