Abstract

The small heterodimer partner (SHP; NROB2), a member of the nuclear receptor superfamily, contributes to the biological regulation of several major functions of the liver. However, the role of SHP in cellular proliferation and tumorigenesis has not been investigated before. Here we report that SHP negatively regulates tumorigenesis both in vivo and in vitro. SHP−/− mice aged 12 to 15 months old developed spontaneous hepatocellular carcinoma, which was found to be strongly associated with enhanced hepatocyte proliferation and increased cyclin D1 expression. In contrast, overexpressing SHP in hepatocytes of SHP-transgenic mice reversed this effect. Embryonic fibroblasts lacking SHP showed enhanced proliferation and produced increased cyclin D1 messenger RNA and protein, and SHP was shown to be a direct negative regulator of cyclin D1 gene transcription. The immortal SHP−/− fibroblasts displayed characteristics of malignant transformed cells and formed tumors in nude mice.

Conclusion

These results provide first evidence that SHP plays tumor suppressor function by negatively regulating cellular growth.

The cell cycle transition from G0 to S phase is controlled by a series of regulatory events.1 The cell cycle clock operates by sequential activation and inactivation of several cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) complexes.2 D-type cyclins bind and activate the Cdk4/63 during early to mid G1, which initiate phosphorylation of the retinoblastoma family of proteins4,5 and lead to release of the E2F family of transcription factors.6 E2F triggers expression of genes, including cyclin E and cyclin A, that enables cells to advance into late G1 and S phases.7 Activation of cyclin E/Cdk2 complex collaborates with cyclin D/Cdk4–6 for the orderly completion of the G1-to-S transition.8,9 The activity of CDKs is negatively regulated by cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, including the CIP-KIP family (p21Cip1, p27Kip1, and p57Kip2) and INK family (p15 INK4b, p16INK4a, p18 INK4c, and p19ARF).10 Members of both families of inhibitors are important for executing growth arrest in response to a variety of DNA damage signals.

Genetic aberrations in the regulatory circuits that govern transit through the G1 phase of the cell cycle occur frequently in human cancers. Perturbation of the cyclin D1/Rb pathway by overexpression of cyclin D1 has been reported as a common alteration leading to a subset of human tumors, including parathyroid adenomas, breast cancer, colon cancer, lymphoma, melanoma, and prostate cancer.11 Overexpression of cyclin D1 also occurs in human12 and mouse13 hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Small heterodimer partner (SHP) is a nuclear receptor functioning as a transcriptional repressor of its target genes.14 Studies with SHP knockouts revealed regulatory functions of SHP in critical aspects of the metabolic disorders.15–17 In this report, we characterized the novel function of SHP in cellular proliferation associated with HCC formation, using SHP knock-outs, SHP transgenic mice, and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs).

Materials and Methods

Isolation, Growth, and Immortalization of Fibroblasts

A mutated SHP allele was generated in mice, whereby the exon 1 coding sequence was replaced with a bacterial NLS-LacZ cassette as described.15 Primary MEFs were isolated from individual E12.5 embryos obtained from crosses between heterozygote SHP+/− animals. The livers of embryos were used for genotyping. All cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), in an incubator at 37°C (5% CO2). Several independently derived immortalized cell lines were generated using a conventional 3T3 protocol that involves passaging cells every 3 days at a fixed cell density.18 For growth curve experiments, we used the Cell Titer 96 Aqueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega). Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) staining (Zymed Laboratories) was performed on liver sections according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protocols for animal use were approved by the Animal Care Committee at the University of Kansas Medical Center.

Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting Analysis

Cell cycle parameters were monitored via propidium iodide staining followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) using an Epics XL Flow Cytometer (Coulter). For 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU)-FACS analysis, cells were incubated with 10 µm of BrdU for 4 hours. Cells were collected, washed, and resuspended in 70% alcohol at 4°C, then stained with anti-BrdU antibody followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate–coupled anti-BrdU secondary antibody (Pharmingen) and prepared for FACS analysis. For cell size analysis, cultures were trypsinized, fixed in 70% alcohol at 4°C, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed via FACS.

To obtain cells enriched in G1 using hydroxyurea: exponentially growing cells were incubated for 16 hours in complete medium supplemented with 100 mM hydroxyurea (Sigma). To allow cells to progress in the cell cycle, the medium was replaced with DMEM plus 10% FBS and cells were harvested at different times. Synchronization in G1-S was performed using the double-thymidine procedure: cells were cultured for 8 hours in DMEM plus 10% FBS supplemented with 2 mM thymidine (Sigma), washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (Invitrogen), cultured for 16 hours in DMEM plus 10% FBS, and finally further incubated for 8 hours in the presence of 2 mM thymidine (Thymidine 0 hours). To allow cells to progress in the cell cycle, the medium was replaced with DMEM plus 10% FBS, and cells were harvested at different times for laser-scanning cytometry. To synchronize cells at G2-M phase, cells were incubated with 0.5 µg/mL nocodazole (Sigma) for 16 hours.

Kinase Assay and Immunoblot Analysis

Cyclin D1–associated Rb-kinase assays were performed as follows. Fibroblasts were harvested in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and whole cell extracts prepared by sonication in Nonidet P40 lysis buffer containing protein inhibitor cocktail (Amersham) and protein phosphotase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Supernatants were then collected, and 50 µg per sample were measured using the Bradford reagent (Sigma). The lysates were incubated for 12 hours at 4°C, with protein A–agarose beads precoated with saturating amounts of the cyclin D1 antibody, DCS-11 (NeoMarkers). Beads containing the immunoprecipitated proteins were washed twice with lysis buffer and twice with kinase buffer, then resuspended in 40 µL of kinase buffer containing substrate (2 µg of soluble GST-RB fusion protein), 10 µM of adenosine triphosphate, and 5 µCi of [γ-32P]adenosine triphosphate (6000 Ci/mmol; Amersham). The samples were incubated for 25 minutes at 30°C with occasional mixing, then boiled in polyacrylamide gel sample buffer containing sodium dodecylsulfate and separated via electrophoresis. Cyclin E–associated H1-kinase assays were performed following the same protocol above, except using cyclin E antibody for immunoprecipitation and histone H1 as the substrate. For immunoblotting analysis, the following antibodies were used: cyclin D2 (Ab-4), cyclin D3 (Ab-1), Cdk2 (Ab-2), Cdk4 (Ab-5), and Cdk6 (Ab-3) from NeoMarkers; cyclin A (C-19), cyclin D1(Ab-2), and cyclin E (M-20) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; and β-actin from Sigma. Blots were incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies (Amersham) followed by detection with an electrochemiluminescence detection kit (Pierce).

Adenovirus, RNA Interference Infection, and Northern Blotting

Viruses were generated by Dr. Kazuhiro Oka (Baylor College of Medicine). Cells were plated at 2 × 106 per 10-cm dish and infected the next day with viral supernatant (multiplicity of infection = 50) for 1 hour. SHP small interfering RNA (Ambion) was then transfected into cells. Gene expression was analyzed via northern blotting.17

Colony Formation, Tumorigenicity, and Chromosome Analyses

To test for the ability of the cells to form colonies when plated at low density, 1.3 × 103 cells were plated in two 10-cm dishes and were fed every 3 days. Following 2 weeks of culture, dishes were stained with Giemsa, and the number of visible colonies were counted. For tumorigenicity assays, exponentially growing MEF cells (2 × 106) were subcutaneously injected into the scapular region of 6-week-old anesthetized nude mice (Swiss nu/nu; Harlan) with two injection sites per mouse, and tumor development was monitored for 4 to 10 weeks. For chromosome analysis, MEFs were exposed to colce-mid (0.02 µg/mL) for 2 hours. Mitotic chromosome spreads were prepared via standard procedures and stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole. At least 300 metaphase spreads were analyzed.

Transient Transfection, Mutagenesis, Electrophoretic Mobility-Shift Assay, and Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay

Mouse SHP and LRH-1 complementary DNA and mouse cyclin D1 promoter-Luc reporters were obtained from Drs. Yoon Kwang Lee and David Moore. CV1 cells were transfected via the calcium phosphate method. Forty hours after transfection, cell extracts were analyzed for luciferase activity and β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity with a Dual-Luciferase Reporter System (Promega). Transfection efficiency was standardized with β-gal activity. Transfection experiments were performed three times with similar efficiency.

The Exsite polymerase chain reaction–based, site-directed mutagenesis (Stratagene) kit was used to introduce mutation in the LRH-1 binding sites of the −970 mCD1 promoter. Three mutant mCD1-Luc constructs were generated, and correct mutations were confirmed on sequencing. The following primers were used: mut-L1-F, 5′-cgatttgcatatctacgacttctgagggggaaggggtttg, and mut-L1-R, 5′-caaacccttccccctcagaagtcgtagatatgcaaatcg; mut-L2-F, 5′-ccccttttctctgcccggaagtgatctctgctt aacaac, and mut-L2-R, 5′-gttgttaagcagagatcacttccgggcagagaaaagggg.

The in vitro–translated LRH-1 proteins were prepared using a coupled transcription and translation kit (Promega). For protein-DNA interaction, in vitro–translated LRH-1 was incubated with the following 32P-labeled duplex oligonucleotide probe: L1-F, 5′-atatctaccaaggct-gagggg, and L1-R, 5′-cccctcagccttggtagatat; L2-F, 5′-ctgcccggctttgatctctg, and L2-R, 5′-cagagatcaaagccgggcag. Mutant probe L1-mut-F: 5′-atatctaccacttctgagggg and L1-mut-R 5′-cccctcagaagtggtagatat was used as a competitor. The wild-type and mutant LRH-1 binding sequences are underlined.

Mouse fibroblasts were used and chromatin was cross-linked immunoprecipitated using standard procedures. Immunoprecipitation was performed with 10 µg anti-SHP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibody overnight at 4°C. The primers mD1 SP-F, 5′-cctccacaggtctcggagga, and SP-R, 5′-gccgacagccctctggaggct, were used to amplify the mCD1 fragment including both LRH-1 binding sites (L1 and L2). The primers mD1 NS-F, 5′-accctcaacgaagc-caatca, and NS-R, 5′-tatccccctcctccactgca, were located upstream of the LRH-1 binding sites in mCD1 and were used for nonspecific amplification.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical analyses were performed using the Student unpaired t test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Spontaneous HCC Formation in SHP−/− Mice Associated with Massive Hepatocyte Proliferation

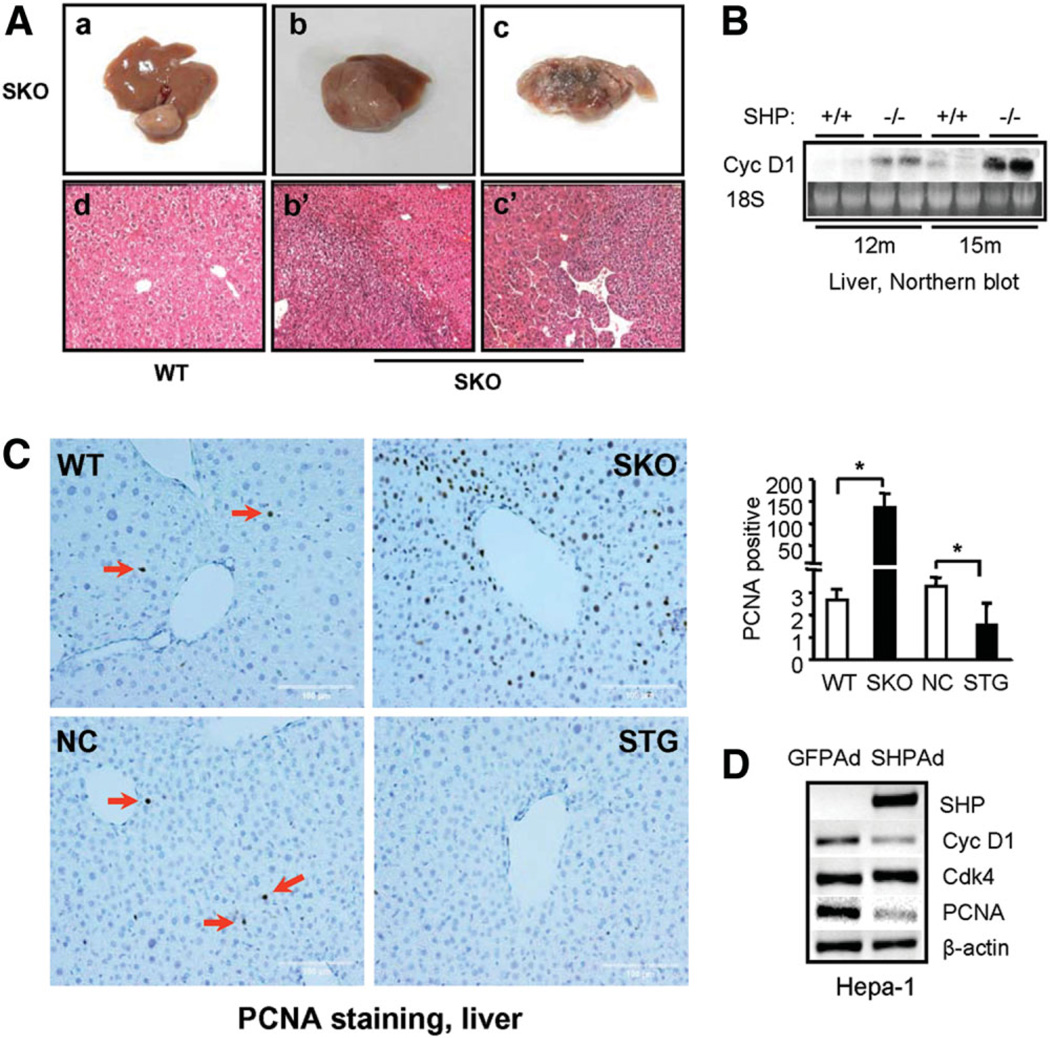

The SHP−/− mice showed no apparent phenotypic abnormalities of the liver in animals up to 6 months of age.17 However, by 15 months of age, we observed spontaneous liver tumors in 19 of 35 (55%) SHP−/− mice that were examined. The tumors were developed at different stages and histologically spanned the range from microadenomas (Fig. 1A, panel a) to adenocarcinomas (Fig. 1A, panels b and b’) to carcinomas (Fig. 1A, panels c and c’). None of the wild-type mice of the same age, maintained under the same conditions, had tumors (panel d). The data suggest that the liver tumors developed in SHP−/− mice were due to the long-term effect of loss of SHP function.

Fig. 1.

Spontaneous formation of HCC in mice lacking SHP. (A) SHP−/− mice developed HCC at 15 months of age (panels a-c). Hema-toxylin-eosin staining of wild-type (WT) liver (panel d) and tumors b and c (panels b’ and c’). (B) Increased cyclin D1 expression in SHP−/− liver compared with wild-type mice by northern blotting. (C) Massive hepatocyte proliferation in livers of SHP−/− (SKO) mice, which was inhibited in SHP-transgenic (STG) mice. NC, nontransgene controls. Ten- to 12-month-old mice were used for the assay. Bar graph represents mean ± SD of PCNA-positive cells counted in three fields per slide (n = 3). (D) SHP inhibition of cyclin D1 and PCNA expression in mouse HCC cell line Hepa-1 cells as examined by semiquantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis.

To determine if changes in hepatocyte proliferation were involved in HCC formation in SHP−/− mice, we examined cyclin D1 messenger RNA (mRNA) via northern blotting. The expression of cyclin D1 was up-regulated in SHP−/− mice at 12 months of age, and this was pronounced in 15-month old mice (Fig. 1B). However, no changes in cyclin D1 mRNA were seen in the livers of wild-type mice. PCNA staining of liver sections revealed massive hepatic proliferation in SHP−/− mice, which was completely reversed by overexpressing SHP in hepatocyte-specific SHP-transgenic mice (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. 1A–D). The data suggest that up-regulation of cyclin D1 and enhanced hepatocyte proliferation may contribute to liver tumor formation in SHP−/− mice. In addition, SHP expression was barely detectable in mouse hepatoma cell line Hepa-1 cells compared with the normal mouse hepatocyte cell line NMuli (Supplementary Fig. 1E), consistent with the notion that SHP deficiency is associated with liver tumor formation in mice. To determine if SHP directly represses cyclin D1 expression in hepatocytes, we overexpressed SHP back into Hepa-1 cells by SHP adenovirus transduction. Overexpression of SHP decreased cyclin D1 (≈50%) as well as PCNA (≈60%) expression (Fig. 1D and Supplementary Fig. 1F). The data further suggest that cyclin D1 may be a novel SHP target gene.

Enhanced Proliferation of Fibroblasts Lacking SHP

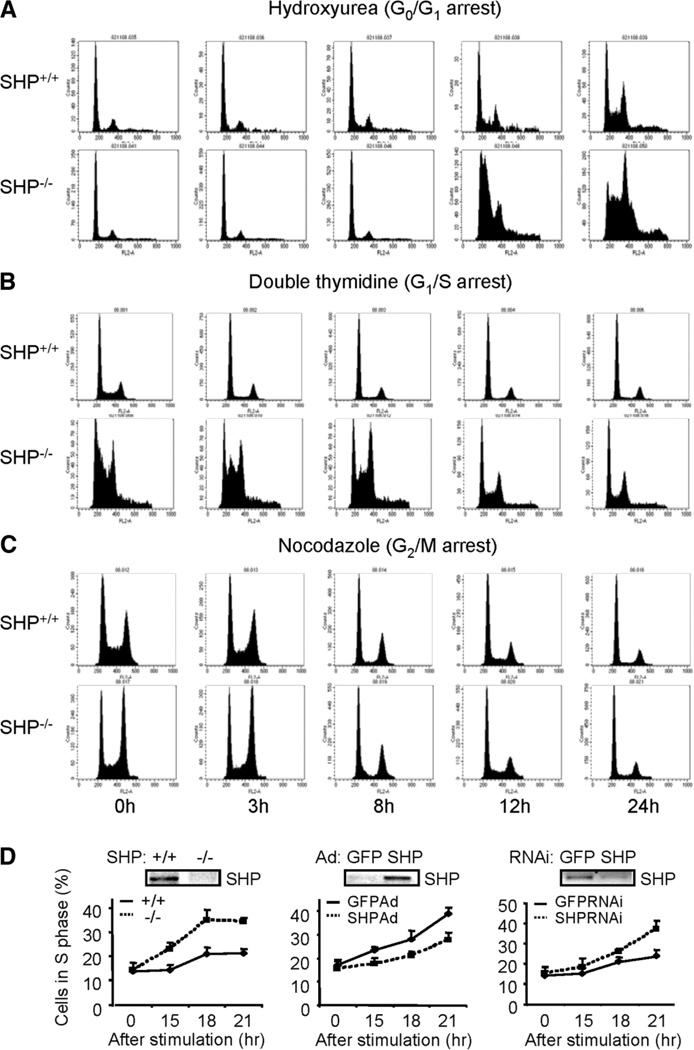

MEFs are a well-established in vitro model to study cell cycle regulation. To explore the role of SHP in cell cycle progression, MEFs were isolated from E12.5 embryos of heterozygous intercross of SHP+/−. Cultures of SHP−/− MEFs were morphologically indistinguishable from those of SHP+/+ MEFs. To further understand the growth properties of MEFs, we derived immortalized cells using the conventional 3T3 protocol18 and observed increased cell proliferation in SHP−/− cells. Compared with wild-type cells, the mutant SHP cells were with a spindlelike morphology (Supplementary Fig. 2A) that were approximately 30% smaller than control cells in volume (Supplementary Fig. 2B). The exponential SHP mutants showed decreased cells accumulated in G0/G1 but increased population of cells in G2/M phase than wild-type cells (Supplementary Fig. 2C, left). Approximately 14% of > 4n cells was seen in SHP mutants, which was detected by BrdU–fluorescein isothiocyanate–FACS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2C, right). To better understand the role of SHP in cellular progression, the cells were quiescent at G0/G1 by hydroxyurea. The SHP−/− cells maintained a persistent higher S phase cell population than the SHP+/+ cells (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Table 1). When cells were synchronized to the G1/S boundary by double thymidine block procedure, SHP-deletion resulted in a higher accumulation of S phase cells and a faster progression into the G2/M phase (Fig. 2B). When the cells were arrested at G2/M phase by nocodazole and released into the cell cycle, the SHP−/− cells progressed into G0/G1 phase in a fashion similar to that of SHP+/+ cells (Fig. 2C). Thus the SHP−/− cells displayed a higher G1/S transition capacity than wild-type controls.

Fig. 2.

Enhanced proliferation of immortalized fibroblasts lacking SHP. (A) FACS analysis of SHP+/+ and SHP−/−MEFs synchronized at G0/G1 by hydroxyurea. (B) FACS analysis of SHP+/+ and SHP−/− MEFs synchronized at G1/S by double thymidine block. (C) FACS analysis of SHP+/+ and SHP−/− MEFs arrested at G2/M phase by nocodazole. (D) FACS analysis of cells synchronized at G0 by serum starvation and released into the cell cycle. Left: SHP+/+ and SHP−/− cells in S phase; middle: re-expressing SHP in SHP−/− cells by adenovirus; right: knocking down SHP in SHP+/+ cells by RNA interference. GFP, control virus.

To determine the kinetics of cell cycle proliferation, cells were made quiescent by serum deprivation and the cell cycle re-entry was elicited by the addition of fresh serum. The SHP−/− cells exhibited faster growth than wild-type controls (Fig. 2D, left). Overexpression of SHP adenovirus into the null cells decreased the growth rate (Fig. 2D, middle), whereas knocking down SHP of wild-type cells by RNA interference enhanced the proliferation (Fig. 2D, right). The data demonstrated that SHP directly inhibits cell proliferation.

Alterations of Kinase Activities and Cyclins of Fibroblasts Lacking SHP

Cell cycle entry of quiescent cells begins with a rapid activation of immediate-early genes,19 such as the MAPK pathway and the induction of c-fos gene expression. The kinetics of MAPK activation was indistinguishable in SHP+/+ and SHP−/− cells (Supplementary Fig. 3A). However, there was a moderate reduction of c-fos (Supplementary Fig. 3B), c-jun, and junB (Supplementary Fig. 3C) expression in SHP−/− cells, indicating a partial impairment in this signal transduction pathway.

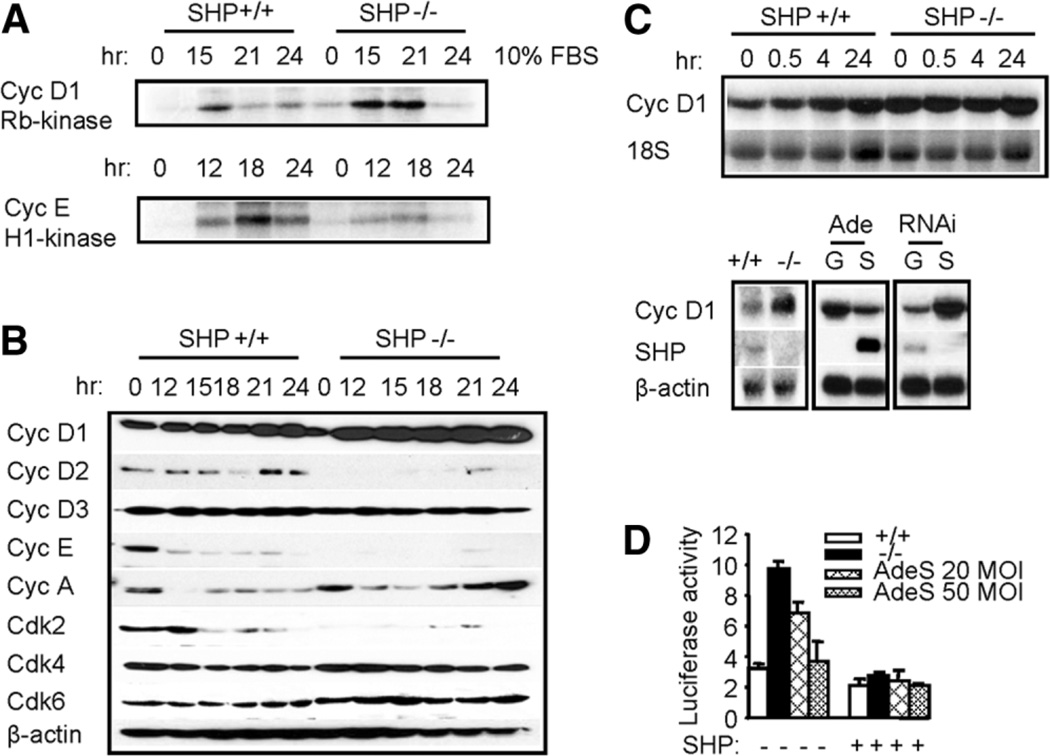

As an initial measure of potential cell cycle defect, we determined the kinase activities of cyclin-CDK complexes. A modest increase in cyclin D1–associated kinase activity was observed in SHP−/− cells (Fig. 3A). The largest defect was seen in cyclin E–associated activity, which was defective in SHP−/− cells.

Fig. 3.

Changes of cyclins and CDKs lacking SHP and inhibition of cyclin D1 mRNA by SHP. (A) Changes of cyclin D1/pRb-kinase activity and cyclin E/H1-kinase activity in SHP+/+ and SHP−/− fibroblasts. Cyclin D-associated or cyclin E-associated protein complexes were immunoprecipitated from cell lysates, and GST-Rb or histone H1 kinase activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins via western blotting in synchronized and restimulated SHP+/+ and SHP−/− fibroblasts. (C) Top: expression of cyclin D1 mRNA in synchronized and restimulated fibroblasts as determined by northern blot. Bottom: expression of cyclin D1 mRNA was increased in exponential growing SHP−/− cells (left), decreased by overexpressing SHP (middle), and increased by knocking down SHP function (right), as determined via northern blotting. G, green fluorescent protein; S, SHP. (D) Cyclin D1 promoter activity. Both the SHP+/+ and SHP−/− cells were transfected with a mouse cyclin D1 promoter reporter with or without SHP expression vector, and promoter activity was measured via luciferase/β-gal assay. AdeS, adenovirus SHP.

To investigate possible causes of the changed CDK activity, the expression levels of cyclins and CDKs in MEFs were examined via immunoblotting. The D-type cyclins are the first cyclins to be induced during the G0-to-S transition, followed by cyclin E in late G1 phase, cyclin A in S phase, and cyclin B in late S and G2 phase.2 Cyclin D1 expression was markedly increased in SHP−/− cells (Fig. 3B). There was a reduction in cyclin D2, cyclin E, and Cdk2 expression in SHP−/− cells, but no difference in expression of cyclin D3, cyclin A, Cdk4, or Cdk6 in SHP+/+ and SHP−/− cells. Thus, the increased cyclin D1 kinase activity may be responsible for the enhanced proliferation property in SHP−/− cells.

SHP Repression of Cyclin D1 mRNA of Embryonic Fibroblasts

To determine if changes in cyclin D1 protein are due to changes in cyclin D1 gene transcription, northern blotting was used to determine cyclin D1 mRNA expression. Cells were starved for 3 days and released into cell cycle, and an elevated level of cyclin D1 mRNA was observed in SHP−/− cells, especially at early time points (Fig. 3C, top). Cyclin D1 mRNA was also increased in exponentially growing SHP−/− cells (Fig. 3C, bottom, left). In addition, re-expression of SHP in SHP−/− cells by adenovirus transduction repressed cyclin D1 mRNA (middle), whereas knocking down SHP expression in wild-type cells by RNA interference effectively increased cyclin D1 mRNA (right). Furthermore, the basal cyclin D1 promoter activity in SHP−/− cells was significantly higher than in wild-type cells, and that addition of SHP by adenovirus transduction or coexpression with SHP vector dramatically decreased cyclin D1 activity (Fig. 3D). The data suggest that SHP may directly repress cyclin D1 expression.

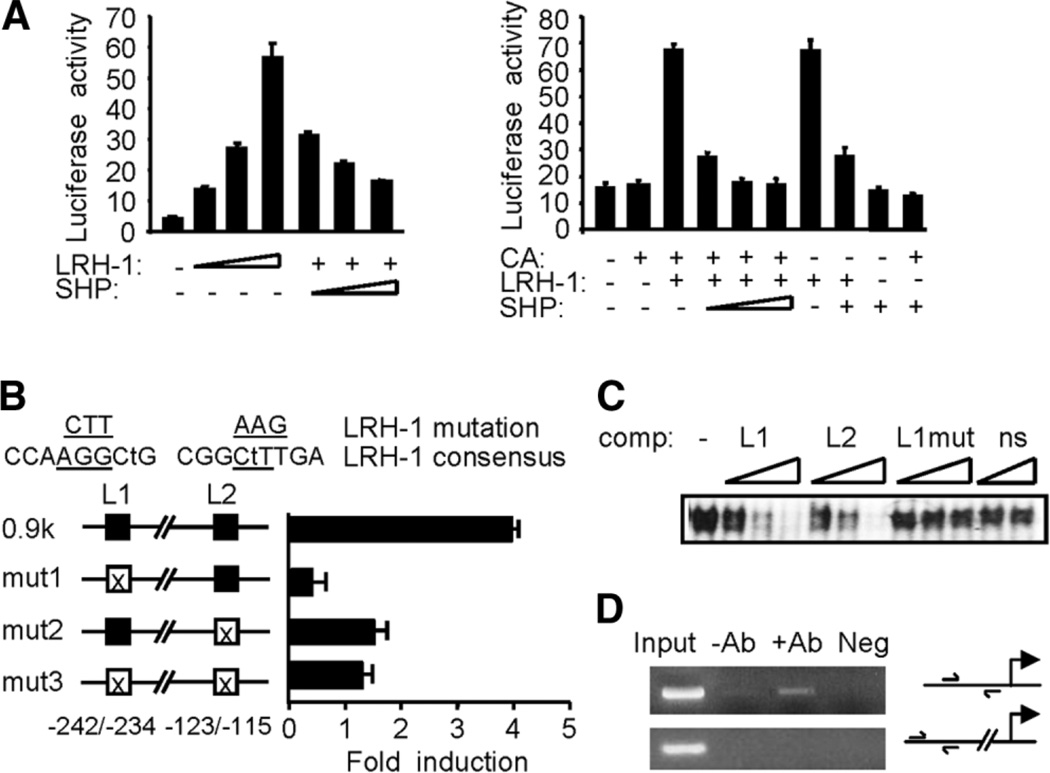

SHP Repression of Cyclin D1 Promoter Transactivation

To explore the molecular basis for the inhibition of cyclin D1 expression by SHP, we localized two potential matches to LRH-1 consensus sites on the proximal mouse cyclin D1 (mCD1) promoter between nt −123 to −115 and −242 to −234. Transient transfection with different deletion constructs showed that mCD1 −336, −675 and −970 reporters (containing L1 and L2) were strongly transcribed in response to LRH-1, which was not observed with the −52mCD1 (containing no LRH-1 site) (Supplementary Fig. 4A). The functionality of the proximal −123 to −115 site of mCD1 promoter was confirmed by the dose-dependent transactivation of −187mCD1 (containing one LRH-1 site) by LRH-1 and a dose-dependent repression by SHP (Fig. 4A, left). β-Catenin has been shown to activate human cyclin D1 promoter through the TCF transcription factor,20 thus we tested the effect of β-catenin, LRH-1, and SHP on mCD1 transactivation using the −970mCD1 (Fig. 4A, right). β-Catenin alone was unable to activate −970mCD1 gene transcription (lane 2 versus 1; Supplementary Fig. 4B). Cotransfection of LRH-1 with β-catenin strongly activated mCD1 (lane 3), and SHP dose-dependently repressed this activation (lanes 4–6). However, the effect on mCD1 gene transcription by β-catenin and LRH-1 (lane 3) did not differ from that of LRH-1 alone (lane 7), suggesting that the effect seen with cotransfection of β-catenin plus LRH-1 was mediated by LRH-1. In addition, with the same amount of SHP, the inhibitory effect of SHP on LRH-1 in the presence of β-catenin (lane 5) was more potent than in the absence of β-catenin (lane 8). Moreover, in the absence of LRH-1, cotransfection of SHP with β-catenin showed a modest inhibitory effect on mCD1 activity that was below the basal level. Cotransfection with β-catenin had no effect or mildly inhibitory effects on LRH-1 activation of the mouse SHP promoter (Supplementary Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Transcriptional repression of cyclin D1 promoter by SHP. (A) Left: a − 187mCD1-Luc was transfected into CV-1 cells with LRH-1 (50, 100, 200 ng) in the absence (−) or presence (+) of SHP (100, 200, 300 ng). Right: reporter gene of −970mCD1-Luc was cotransfected with expression vectors for β-catenin (CA, 400 ng), LRH-1 (100 ng), and SHP (100, 200, 300 ng; fixed amount: 200 ng) as indicated. Luciferase activities were normalized against β-galactosidase and expressed as relative activity. (B) Mutagenesis study. The mCD1 gene contains two potential LRH-1 sites (L1, L2). Mismatches with the consensus sequence are indicated by lower case letters, and mutated sequences are underlined. The mutated constructs (mut1, mut2, and mut3) were transfected into CV-1 cells with or without LRH-1 (100 ng). (C) Gel shift assay. In vitro translated LRH-1 was incubated with the 32P-labeled L1 and increasing amounts of unlabeled L1 (lanes 2–4), L2 (lanes 5–7), and mutated L1 (lanes 8–10) or HNF-4 binding sequences (ns: lanes 11–12). (D) Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis. Chromatin preparations from MEFs were subjected to chromatin immunoprecipitation assay with anti-SHP antibodies. DNA in the immunoprecipitates was polymerase chain reaction-amplified with the primers shown in the illustration of the promoter region. DNA from equal amounts of chromatin was polymerase chain reaction amplified before immunoprecipitation (Input). Neg, immunoglobulin G.

The function of the two LRH-1 binding sites (L1 and L2) was confirmed using mutagenesis (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, disruption of L1 resulted in a 90% decrease in mCD1 gene transcription, whereas mut2 lost approxi-mately 60% of the transactivation produced by LRH-1. Unexpectedly, the double mutant (mut3) did not completely abolish LRH-1–mediated transcription. It is possible that additional nonconsensus but weak LRH-1 sites might exist within the −970mCD1 promoter region. The binding activities of the L1 and L2 sequences were analyzed via electrophoretic mobility-shift assay using the oligonucleotides listed in Materials and Methods. When the oligonucleotides containing L1 and L2 were incubated with an in vitro synthesized LRH-1, both L1 and L2 competed for LRH-1 binding, whereas mutant L1 had no effect (Fig. 4C). Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays confirmed the coimmunoprecipitation of SHP with mCD1 in MEFs (Fig. 4D). Because LRH-1 is expressed in MEFs (Supplementary Fig. 5A), these studies demonstrate that SHP is a transcriptional repressor of cyclin D1 gene transcription by LRH-1.

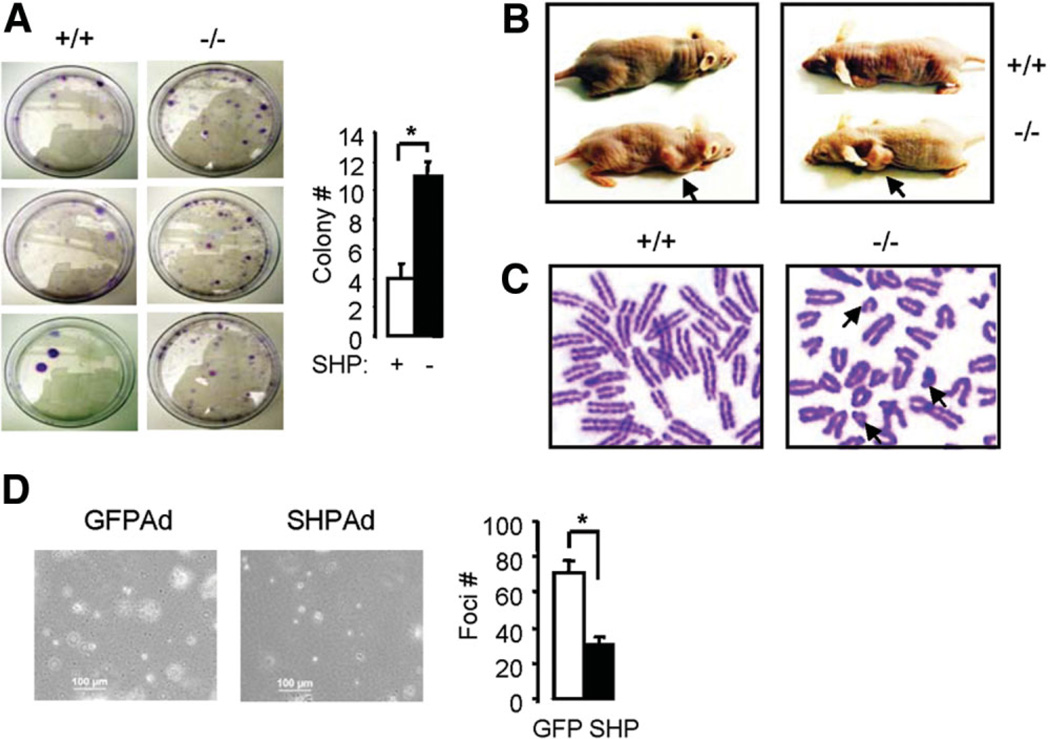

Malignant Transformation of Immortal Fibroblasts Lacking SHP

Although the SHP−/− cells were smaller, they reached higher density at confluence, lost contact inhibition property, and failed to undergo cell cycle arrest, all of which are hallmarks of transformed cells. To investigate the tumorigenicity of SHP−/− cells, we analyzed malignant features of the cells. SHP−/− cells exhibited increased colonies in soft agar (Fig. 5A) and tumor formation in nude mice (Fig. 5B). In contrast, matched control wild-type cells showed fewer colonies and did not form tumors within 6 weeks when the experiment was conducted. We ask if genetic alterations occurred in the immortal SHP−/− cells, and if SHP deficiency could contribute to such alterations. In support of this hypothesis, SHP−/− MEFs displayed an increased number of aberrations, such as many short chromosomes, which were rarely observed in SHP+/+ cells (Fig. 5C). To determine if decreased cyclin D1 expression is associated with the tumorgenic property of the cells, we overexpressed SHP using adenovirus into SHP−/− cells and examined its effect on foci formation. As expected, over-expression of SHP repressed cyclin D1 expression (Supplementary Fig. 5B) and reduced the number of foci formation (Fig. 5D). The data suggest that loss of SHP resulted in aberrant cell proliferation and cyclin D1 expression, which is associated with the transformed phenotype.

Fig. 5.

Transformation and tumorigenesis of immortalized fibroblasts lacking SHP. (A) Colony formation assay. Results from three independent SHP+/+ and SHP−/− cells were shown. (B) Tumorigenicity assay in nude mice. Four wild-type and five SHP mutant 3T3 clones were tested. Nude mice were still tumor-free 6 weeks after injection of wild-type MEF cells, whereas tumors (arrows) were observed 4 weeks after injection of SHP−/− cells. Photographs were taken 6 weeks after injection. (C) Chromosome spreads of SHP+/+ and SHP−/− 3T3 cells to examine chromosome aberrations. Each metaphase spread was assessed for the frequency of chromosome abnormalities. Note that only parts of spreads are shown in order to highlight the short chromosomes (arrows) found in SHP−/− cells. (D) Foci formation assay. SHP was overexpressed into SHP−/− fibroblasts by adenovirus transduction. Statistical results represent the mean ± standard deviation of foci counts from two different fields of triplicate plates.

Discussion

The effects of orphan nuclear receptor SHP on cellular proliferation and transformation have not been documented before. In this study, we show that deletion of SHP results in enhanced hepatocyte proliferation, which is directly associated with the development of liver tumor. We further show that the impaired function of SHP causes perturbations in growth of SHP−/− MEF cells. SHP regulates cell proliferation through repression of cyclin D1, thereby providing a novel molecular link between SHP and the cell cycle machinery. Deletion of SHP in fibroblasts causes a phenotype characterized by transformation of immortalized MEFs. Our results reveal a unique role for SHP in mediating cell growth associated with the development of HCC.

Despite extensive studies of tumor suppressor genes, there are presently no excellent mouse models demonstrating increased susceptibility to liver tumors.21 Suggested mechanisms of liver tumor formation are enhanced cell replication, promotion of spontaneous preneoplastic lesions, and inhibition of apoptosis. Abnormal expression of cyclin D1 has been described in liver cancers in both mice13 and humans.12 Our data provide new evidence that the enhancement of cyclin D1 expression and hepatocyte proliferation contribute to the development of liver cancer in SHP−/− mice. Thus, SHP may play a tumor suppressor function in the development of HCC.

SHP−/− mice did not show overt growth defects after birth,17 thus SHP is apparently dispensable for normal mouse embryogenesis. However, examination of SHP−/− fibroblasts indicates that SHP is required during continuous proliferation. Our analysis indicates that impaired function of SHP causes enhanced growth of SHP−/− fibroblasts. The increases in the expression levels of cyclin D1, cyclin D1 kinase activity, and subsequently the activation of E2F (Supplementary Fig. 5C), matches well with that in the increased cell proliferation in SHP−/− MEFs. For correct regulation of CDK activities, the amount of G1 cyclins, as well as CDK and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors will be tightly regulated within a certain range. The hyperproliferation occurs despite inactivation of cyclin E kinase activity, suggesting that cyclin E and Cdk2 are nonessential mediators for SHP-induced antiproliferative signaling. Because cyclin D1 and cyclin E subserve at least partially overlapping functions, and the roles of cyclin E and Cdk2 are dispensable in controlling cell cycle progression,22,23 the increased cyclin D1–associated kinase activity in SHP−/− cells may play a major role for the increased cell proliferation property.

A recent report describes the role of LRH-1 in enhancing cell proliferation through targeting cyclin D1 and cyclin E.24 In general, our results are similar and support the conclusion of a negative regulatory role of SHP on cyclin D1 transcription.24 However, we observed decreased cyclin E and Cdk 2 protein levels in SHP−/− rMEFs. Thus the regulatory function of SHP on cyclin E gene transcription may be cell type–specific. Other studies have also pointed toward a role of SHP in cell cycle control, such as regulation of p21 promoter activity25,26 and sexual maturation of male mice that involves several cyclins.27 Thus, SHP may also play a role at different phases of cell cycle.

Loss of SHP function in SHP−/− mice enhanced hepatocyte proliferation and promoted transformation of hepatocytes. Consistent with this observation, the immortal SHP mutant MEFs showed enhanced proliferation and displayed characteristics of malignant transformed cells, including formation of more colonies in soft agar and promoting tumor growth in immune compromised mice. Based on observations from these two different cell types, we conclude that SHP deficiency is an important factor in promoting tumorigenesis.

It is noted that HCC was only developed in old SHP−/− mice. The transcriptional corepressor Tob gene has been identified as a tumor suppressor by repressing cyclin D1.21 The mice lacking Tob did not show abnormalities in their early livers, but developed liver tumors by 18 months of age. Thus, the finding from both studies is very similar. Although the enhanced hepatocyte proliferation is directly associated with the development of HCC in SHP−/− mice, we consider it an initiating factor or first “hit.” A second hit, or other genetic alternations, may also be involved in HCC progression. For instance, bile acids have been shown to be promoting agents for HCC formation in nuclear receptor FXR knockout mice, which also showed increased cyclin D and cyclin E expression.28 The levels of bile acids are also increased in SHP−/− livers due to loss of SHP repression of bile acid synthesis.17 It is possible that bile acids may also promote the development of HCC in SHP−/− mice.

In conclusion, we show the novel effects of SHP on cellular proliferation and transformation. The future elucidation of how SHP modulates other signaling pathways, such as apoptosis signaling, will be of importance to our better understanding of nuclear receptors in the development of liver cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Dr. Curt Hagedorn for critical reading of the manuscript, Dr. Kazuhiro Oka for the adenoviruses, and Drs. Nan He and Jian-sheng Huang for their help.

Supported by funds from the American Liver Foundation/American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (Liver Scholar Award), the American Diabetes Association (Junior Faculty Award), and the American Heart Association (BGIA Award) to L.W. and 2007AA02Z460 and 30370645.

Abbreviations

- β-gal

β-galactosidase

- BrdU

5-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine

- CDK

cyclin-dependent kinase

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- mCD1

mouse cyclin D1

- MEF

mouse embryonic fibroblast

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- SHP

small heterodimer partner

Footnotes

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Supplementary material for this article can be found on the Hepatology Web site (http://interscience.wiley.com/jpages/0270-9139/suppmat/index.html).

References

- 1.Sherr CJ. D-type cyclins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:187–190. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harper JW, Elledge SJ. Cdk inhibitors in development and cancer. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:56–64. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)90011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates SL, Bonetta L, Macallan D, Parry D, Holder A, Dickson C, et al. CDK6 (PLSTIRE) and CDK4 (PSKJ3) are a distinct subset of the cyclin-dependent kinases that associate with cyclin D1. Oncogene. 1994;9:71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mayol X, Garriga J, Grana X. Cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of the retinoblastome-related protein p130. Oncogene. 1995;11:801–808. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiao ZX, Ginsberg D, Ewen M, Livingston DM. Regulation of the retinoblastoma protein-related protein p107 by G1 cyclin-associated kinases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:4633–4637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hiebert SW, Chellappan SP, Horowitz JM, Nevins JR. The interaction of RB with E2F coincides with an inhibition of the transcriptional activity of E2F. Genes Dev. 1992;6:177–185. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.2.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grana X, Reddy EP. Cell cycle control in mammalian cells: role of cyclins, cylin dependent kinases (CDKs), growth suppressor genes and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors (CKIs) Oncogene. 1995;11:211–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dulic V, Lees E, Reed SI. Association of human cyclin E with a periodic G1-s phase protein kinase. Science. 1992;257:1958–1961. doi: 10.1126/science.1329201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lundberg AS, Weinberg RA. Functional inactivation of the retinoblastoma protein requires sequential modification by at least two distince cyclin-cdk complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:753–761. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morgan DO. Cyclin-dependent kinases: engines, clocks, and microprocessors. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:261–291. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diehl JA. Cyclin to cancer with cyclin D1. Cancer Biol Ther. 2002;1:226–231. doi: 10.4161/cbt.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sato Y, Itoh F, Hareyama M, Satoh M, Hinoda Y, Seto M, et al. Association of cyclin D1 expression with factors correlated with tumor progression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:486–493. doi: 10.1007/s005350050301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deane NG, Parker MA, Aramandla R, Diehl L, Lee WJ, Washington MK, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma results from chronic cyclin D1 overexpression in transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5389–5395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bavner A, Sanyal S, Gustafsson JA, Treuter E. Transcriptional corepression by SHP: molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2005;16:478–488. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L, Liu J, Saha P, Huang JS, Chan L, Spiegelman B, et al. The orphan nuclear receptor SHP regulates PGC-1 α expression and energy production in brown adipocytes. Cell Metab. 2005;2:227–238. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang L, Huang J, Saha P, Kulkarni RN, Hu M, Kim Y, et al. Orphan receptor small heterodimer partner is an important mediator of glucose homeostasis. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:2671–2681. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang L, Lee YK, Bundman D, Han Y, Thevananther S, Kim CS, et al. Redundant pathways for negative feedback regulation of bile acid production. Dev Cell. 2002;2:721–731. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Todaro GJ, Green H. Quantitative studies of the growth of mouse embryo cells in culture and their development into established lines. J Cell Biol. 1963;17:299–313. doi: 10.1083/jcb.17.2.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mateyak MK, Obaya AJ, Sedivy JM. c-Myc regulates cyclin D-Cdks and -Cdk6 activity but affects cell cycle progression at multiple independent points. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4672–4683. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tetsu O, McCormick F. Beta-catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature. 1999;398:422–426. doi: 10.1038/18884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoshida Y, Nakamura T, Komoda M, Satoh H, Suzuki T, Tsuzuku JK, et al. Mice lacking a transcriptional corepressor Tob are predisposed to cancer. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1201–1206. doi: 10.1101/gad.1088003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geng Y, Yu Q, Sicinska E, Das M, Schneider JE, Bhattacharya S, et al. Cyclin E ablation in the mouse. Cell. 2003;114:431–443. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00645-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ortega S, Prieto I, Odajima J, Martin A, Dubus P, Sotillo R, et al. Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 is essential for meiosis but not for mitotic cell division in mice. Nat Genet. 2003;35:25–31. doi: 10.1038/ng1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Botrugno OA, Fayard E, Annicotte JS, Haby C, Brennan T, Wendling O, et al. Synergy between LRH-1 and beta-catenin induces G1 cyclin-mediated cell proliferation. Mol Cell. 2004;15:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JY, Chu K, Kim HJ, Seong HA, Park KC, Sanyal S, et al. Orphan nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner, a novel corepressor for a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor BETA2/neuroD. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:776–790. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suh JH, Huang J, Park YY, Seong HA, Kim D, Shong M, et al. Orphan nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner inhibits transforming growth factor-beta signaling by repressing SMAD3 transactivation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39169–39178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605947200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volle DH, Duggavathi R, Magnier BC, Houten SM, Cummins CL, Lobaccaro JM, et al. The small heterodimer partner is a gonadal gatekeeper of sexual maturation in male mice. Genes Dev. 2007;21:303–315. doi: 10.1101/gad.409307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang F, Huang X, Yi T, Yen Y, Moore DD, Huang W. Spontaneous development of liver tumors in the absence of the bile acid receptor farnesoid X receptor. Cancer Res. 2007;67:863–867. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.