Abstract

Arthropod saliva possesses anti-hemostatic, anesthetic, and anti-inflammatory properties that facilitate feeding and, inadvertently, dissemination of pathogens. Vector-borne diseases caused by these pathogens affect millions of people each year. Many studies address the impact of arthropod salivary proteins on various immunological components. However, whether and how arthropod saliva counters Nod-like (NLR) sensing remains elusive. NLRs are innate immune pattern recognition molecules involved in detecting microbial molecules and danger signals. Nod1/2 signaling results in activation of the nuclear factor-κB and the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Caspase-1 NLRs regulate the inflammasome~– a protein scaffold that governs the maturation of interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18. Recently, several vector-borne pathogens have been shown to induce NLR activation in immune cells. Here, we provide a brief overview of NLR signaling and discuss clinically relevant vector-borne pathogens recognized by NLR pathways. We also elaborate on possible anti-inflammatory effects of arthropod saliva on NLR signaling and microbial pathogenesis for the purpose of exchanging research perspectives.

Keywords: Nod-like receptors, inflammasome, vector-borne pathogens, vector-borne diseases, arthropod saliva, salivary proteins

INTRODUCTION

Vector-borne diseases impact individuals worldwide and, with their frequencies increasing, they are becoming a crucial public health problem in need of attention (McGraw and O’Neill, 2013). With more than 200 million affected individuals, malaria is spreading rampant in tropical and subtropical regions and dengue fever is following close behind (Table 1). The spread of these illnesses, as well as other vector-borne diseases, has been attributed to rapid globalization, anthropomorphic and environmental changes, and the lack of effective vaccines (Kovats et al., 2001). These maladies have been combated by preventive care and therapeutics (Mejia et al., 2006; Fontaine et al., 2011). In order to develop novel treatments, scientists are continuously attempting to elucidate the mechanism of microbial transmission and aspects of the immune system that are involved in pathogen recognition (Titus and Ribeiro, 1990). Considering the variability between pathogens being transmitted from an arthropod vector to the mammalian host, one can imagine why the development of a vaccine has been an arduous task. However, vaccine development has taken a new route towards a common factor that all disease-transmitting vectors share: saliva. To promote feeding, hematophagous arthropods rely on salivary proteins to not only impart anti-hemostatic capabilities but also anti-inflammatory activities (Ribeiro and Francischetti, 2003; Chmelar et al., 2012).

Table 1.

Nod-like receptors and vector-borne diseases of health and economic importance.

*Estimates are not available.

**Estimates in the United States and Europe.

***Estimates in the United States.

—Not applicable.

? Potential association, needs further confirmation.

The relationship between arthropod saliva and components of the vertebrate immune system, such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs), has been studied. However, one crucial element of innate immunity that still remains vague, with regards to vector-borne diseases, is Nod-like receptors (NLRs). NLRs are an evolutionarily conserved mechanism for pathogen recognition found in both plants and mammals (Nürnberger et al., 2004). Since their discovery, numerous groups have identified the role of NLRs in the recognition of self-derived danger associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), such as ATP, and pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as those from fungi, bacteria, and viruses (Strowig et al., 2012). However, the association between NLRs and vector-borne pathogens still remains unclear. Only recently have researchers drawn attention to the detection of these pathogens by NLRs; even more ambiguous is the connection between salivary proteins and NLRs.

Here, we will address what occurs once a crucial barrier, the skin, is breached by an arthropod vector. We will discuss the subsequent recognition of key vector-borne pathogens by NLRs, and potential mechanisms by which salivary proteins may modulate this interaction. Though not all-encompassing, our focus is on acknowledging major examples by which saliva can modify immunity during infection. For a more comprehensive discussion about proteinaceous and non-proteinaceous salivary molecules, and their function during arthropod feeding, the reader is referred to accompanying reviews in this thematic research topic.

ARTHROPOD SALIVA AND SALIVARY PROTEINS

Hematophagous arthropods have developed ways to promote the extraction of blood from their hosts while evading detection. The penetration of an arthropod mouthpart into the mammalian host promotes the release of saliva and allows for the acquisition of a blood meal. Though some components of saliva are ubiquitous to all arthropods, specific molecules for different vectors have also been reported (Mans and Francischetti, 2011). For over a hundred years, researchers have identified and dissected the components of saliva and found it to contain anti-hemostatic and anti-inflammatory properties (Sabbatani, 1899). In order to maintain a fluid supply of blood, salivary proteins act as vasodilators, inhibitors of platelet activity, and anti-coagulants (Champagne, 2005). To avoid recognition by the host, saliva not only modulates the inflammatory response, but it can also inhibit immune signaling (Chmelar et al., 2012). Arthropod saliva is composed of a plethora of salivary proteins that possess unique immunomodulatory functions (Table 2). Effects of tick saliva can been seen in a range of immune cell types, such as macrophages, neutrophils, T cells, B cells, and others (Gillespie et al., 2000; Titus et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2012). Salivary proteins with immunomodulatory properties from a myriad of arthropods, include but are not limited to: Rhodnius prolixus, Rhipicephalus appendiculatus, Lutzomyia longipalpis, Aedes aegypti, and Anopheles gambiae have been described. These proteins do not simply target one immune constituent but rather they span the gamut of cellular and molecular immunity.

Table 2.

Salivary protein components and immunity.

| Protein component | Vector | Cellular | Molecular | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISL929 ISL1373 | Ixodes scapularis | Neutrophils | ↓ Superoxide production ↓ β2-integrins | Guo et al. (2009) |

| ISAC | I. scapularis | Complement | Dissociates C3 convertase | Valenzuela et al. (2000), Soares et al. (2005) |

| IL-2 binding protein | I. scapularis | T cells | Binds IL-2 | Gillespie et al. (2001) |

| Salp 25D | I. scapularis | Catalyzes the reduction of hydrogen peroxide with glutathione and glutathione reductase (antioxidant) | Das et al. (2001) | |

| Salp20 | I. scapularis | Complement | Dissociates C3 convertase | Tyson et al. (2007), Tyson et al. (2008) |

| Sialostatin L | I. scapularis | Neutrophils, dendritic cells, mast cells | ↓ Neutrophil influx, CD80/86, IL-12p70, TNF-α, MHC II, cathepsin L, IFN-γ, IL-17, T cell proliferation | Kotsyfakis et al. (2006), Kotsyfakis et al. (2007), Sá-Nunes et al. (2009), Horka et al. (2012) |

| IsSMase | I. scapularis | T cells | ↑ IL-4 | Alarcon-Chaidez et al. (2009) |

| PGE2 | I. scapularis | Dendritic cells | ↓ IL-12, TNF-α, CD40, inhibitor of differentiation Induces cAMP-PKA signaling | Sá-Nunes et al. (2007), Oliveira et al. (2011) |

| Histamine release factor (HRF) | I. scapularis Dermacentor variabilis | Basophils, mast cells | Release of histamine | Dai et al. (2010), Mulenga et al. (2003) |

| DAP-36 | Dermacentor andersoni | T cells | Bergman et al. (1995) | |

| IRS-2 | Ixodes ricinus | Neutrophils | Inhibits cathepsin G and chymase | Chmelar et al. (2011) |

| IRAC I and II | I. ricinus | Complement | Dissociates C3 convertase | Schroeder et al. (2007) |

| IRIS | I. ricinus | Monocytes, macrophages, T cells | ↓ TNF-α and IFN-γ | Prevot et al. (2009), Fontaine et al. (2011) |

| Ir-LBP | I. ricinus | Neutrophils (chemotaxis) | Binds leukotriene B4 | Beaufays et al. (2008) |

| BIP | I. ricinus | B cells | Inhibits B cell activation | Hannier et al. (2004) |

| TSLPI | Ixodes spp. | Complement, neutrophils | Inhibits mannose-binding lectin | Schuijt et al. (2011) |

| Salp15 | Ixodes spp. | Dendritic cells, T cells, complement | Raf-1/ MEK activation ↓ IL-6, TNF-α, and IL-12p35 CD4 binding ↓ T cell activation and IL-2 ↓ Membrane attack complex | Hovius et al. (2008), Anguita et al. (2002), Garg et al. (2006), Berende et al. (2010) |

| Histamine binding proteins (HBP) Lipocalins | Ixodes spp. Rhodnius prolixus | Basophils, mast cells | Binds histamine | Paesen et al. (1999), Sangamnatdej et al. (2002), Andersen et al. (2005) |

| Nitrophorins | Rh. prolixus | Binds histamine | Gazos-Lopes et al. (2012) | |

| IgG-BP | Ixodes spp. Rhipicephalus appendiculatus | IgG | Binds IgG | Wang and Nuttall (1995), Wang and Nuttall (1999), Wang et al. (1998) |

| Maxadilan | Lutzomyia longipalpis | T cells, macrophages | ↓ Nitric oxide, TNF- α ↑ Prostaglandin E2, IL-10, IL-6 | Gillespie et al. (2000) |

| Adenosine and adenosine monophosphate | Phlebotomus papatasi Rhipicephalus sanguineus | T cells, macrophages, NK cells?, dendritic cells | ↓ Nitric oxide and IFN-γ | Hall and Titus (1995), Katz et al. (2000), Oliveira et al. (2011) |

| Evasin-1, -3, -4 | R. sanguineus Tick spp. | Binds chemokines (Evasin-1: CCL3, CCL4, CCL18) (Evasin-3: CXCL8, CXCL1) (Evasin-4: CCL5, CCL11) | Frauenschuh et al. (2007), Déruaz et al. (2008) | |

| Ado | R. sanguineus | Dendritic cells | Induce cAMP-PKA to reduce cytokine production | Oliveira et al. (2011) |

| D7 proteins | Aedes aegypti Anopheles gambiae | Binds histamine | Calvo et al. (2006) | |

| Sialokinins | Aedes aegypti | T cell | Zeidner et al. (1999) |

An example of an immunomodulatory molecule in saliva is evasin. This protein manipulates immune signaling by binding key chemokines, thus, inhibiting the production of cytokines (Frauenschuh et al., 2007; Déruaz et al., 2008). The tick proteins ISL929, ISL1373, sialostatin L, IRS-2, Ir-LBP, and TSLP1 all target neutrophils, usually the first immune cell to respond to a pathogen (Kotsyfakis et al., 2006,2007; Beaufays et al., 2008; Guo et al., 2009; Sá-Nunes et al., 2009; Chmelar et al., 2011; Schuijt et al., 2011). Antigen presenting cells are the focus of the following salivary molecules: japanin, sialostatin L, PGE2, IRIS, Salp15, Ado, and maxadilan (Gillespie et al., 2000; Anguita et al., 2002; Leboulle et al., 2002; Garg et al., 2006; Kotsyfakis et al., 2006,2007; Hovius et al., 2008; Schuijt et al., 2008; Prevot et al., 2009; Sá-Nunes et al., 2007,2009; Berende et al., 2010; Fontaine et al., 2011; Oliveira et al., 2011; Preston et al., 2013; Ullmann et al., 2013). Histamine release factor (HRF) and histamine binding proteins (HBP) both act on granule releasing cells (Paesen et al., 1999; Sangamnatdej et al., 2002; Mulenga et al., 2003; Andersen et al., 2005; Dai et al., 2010), while sialostatin L affects cytokine secretion by mast cells (Horka et al., 2012). The complement cascade is a crucial factor involved in directing inflammatory responses through the formation of complexes on the pathogen surface, opsonization, and membrane-attack complex (MAC). ISAC, Salp20, IRAC I/II, TSLP1, and Salp15 can all inhibit the complement system (Valenzuela et al., 2000; Anguita et al., 2002; Garg et al., 2006; Tyson et al., 2007; Schroeder et al., 2007; Schuijt et al., 2008; Hovius et al., 2008; Berende et al., 2010). Salivary constituents not only aim for the innate immune system, but they also act on the adaptive immunity. Salivary components may act on T cells, B cells, or antibodies, as is the case with IL-2 binding protein, IsSMase, IRIS, BIP, Salp15, IgG-BP, and maxadilan (Wang and Nuttall, 1995,1999; Wang et al., 1998; Gillespie et al., 2001; Hannier et al., 2004; Alarcon-Chaidez et al., 2009; Prevot et al., 2009; Fontaine et al., 2011).

Although some of these proteins have overlapping cellular targets, their activity at the molecular level demonstrate some variability. For instance, ISAC, Salp20, IRAC I/II, TSLP1, and Salp15 inhibit complement through different mechanisms. ISAC, Salp20, and IRACI/II dissociate the crucial complement convertase molecule C3 (Paesen et al., 1999; Lögdberg and Wester, 2000; Valenzuela et al., 2000; Anguita et al., 2002; Leboulle et al., 2002; Sangamnatdej et al., 2002; Andersen et al., 2005; Garg et al., 2006; Daix et al., 2007; Schroeder et al., 2007; Tyson et al., 2007,2008; Déruaz et al., 2008; Schuijt et al., 2011). However, TSLP1 and Salp15 target the complement pathway by inhibiting mannose-binding lectin and MAC, respectively (Schuijt et al., 2008). Even within the same organism, salivary proteins can influence T cells in different ways. IL-2 binding, does as its name implies, blocks IL-2 while IsSMase affects T cells by increasing IL-4 (Gillespie et al., 2001; Alarcon-Chaidez et al., 2009). Immune regulation by the saliva of arthropod vectors discussed in this review consists of: (1) impediment of attachment, (2) reduction of oxidants, (3) decrease of pro-inflammatory enzymatic activity, (4) modification of cytokine levels, (5) attenuation of co-receptor binding, and (6) sequestration of pro-inflammatory mediators from binding to their receptors (Table 2).

Modulation of host immunity favors arthropod blood-feeding (Fontaine et al., 2011). This occurrence was first observed upon infection with Leishmania parasites (Titus and Ribeiro, 1988). More recently, studies demonstrated that enhancement of pathogen infection by saliva seems universal (Francischetti et al., 2009; Fontaine et al., 2011). Increased infectivity in the presence of arthropod saliva has been shown for pathogens transmitted by sandflies, mosquitoes and ticks (Titus et al., 2006). Specifically, mosquito saliva enhances transmission of malaria parasites (Vaughan et al., 1999), West Nile (Styer et al., 2011), La Crosse (Osorio et al., 1996) and Cache Valley (Edwards et al., 1998) viruses. Similarly, tick saliva counteracts host-derived inflammation (Francischetti et al., 2009; Fontaine et al., 2011) by impairing the function of innate and adaptive immune cells (de Silva et al., 2009), and inhibiting cytokine secretion (Fontaine et al., 2011). Borrelia burgdorferi – the Lyme disease agent - appears shielded by a salivary protein called Salp15 from the tick I. scapularis, and in turn, protected from antibody-mediated killing (Ramamoorthi et al., 2005) and dendritic cell function (Valenzuela et al., 2000; Hovius et al., 2008). However, this effect is not unique to Salp15 because sialostatin L2, another protein, also facilitates pathogen transmission at the skin site (Kotsyfakis et al., 2010). Interestingly, in the Aedes aegypti mosquito model, saliva appears to protect dendritic cells from infection with dengue virus in vitro (Ader et al., 2004).

An intriguing aspect of the pathogen-saliva interaction lies in the response of the skin to infection (Frischknecht, 2007; Krause et al., 2009). During the infectious blood meal, the arthropod mouthpart dilacerates and penetrates the epidermis and reaches the dermis. The skin injury leads to a local inflammatory response involving secretion of chemokines, cytokines, and antimicrobial molecules as well as dermal mast cell degranulation, fluid extravasation and neutrophil influx (Boulanger et al., 2006; Rubin and Strayer, 2012). This response has a major impact on furthering the establishment of infection because pathogen inoculation follows an arthropod bite. Cellular responses promoted by mast cells, neutrophils, dendritic cells and infiltrated macrophages aim not only to repair the skin injury, but also remove a microbial threat during vector transmission. This series of steps also reverberates on the later activation of adaptive immunity and recruitment of cell types that may promote pathogen propagation in the host, especially for intracellular microorganisms.

NOD-LIKE RECEPTORS

Approximately two decades ago, a group of sensors were added to the pattern recognition receptor family, expanding what was known about intracellular recognition of endogenous and exogenous molecules (Inohara et al., 1999). NLRs are appropriately named due to their characteristic nucleotide binding and oligomerization domain (NOD). NLRs may also contain leucine-rich repeats (LRR) at their C-terminus and a variable effector domain at their N-terminal end, all of which play a role in pathogen recognition and immunity (Moreira and Zamboni, 2012). Although 22 human and 30 mouse NLRs been discovered, to stay within the scope of our review, we will only address those that have been associated with crucial vector-borne diseases (Table 1; Schroder and Tschopp, 2010; Moreira and Zamboni, 2012).

NOD1 AND NOD2

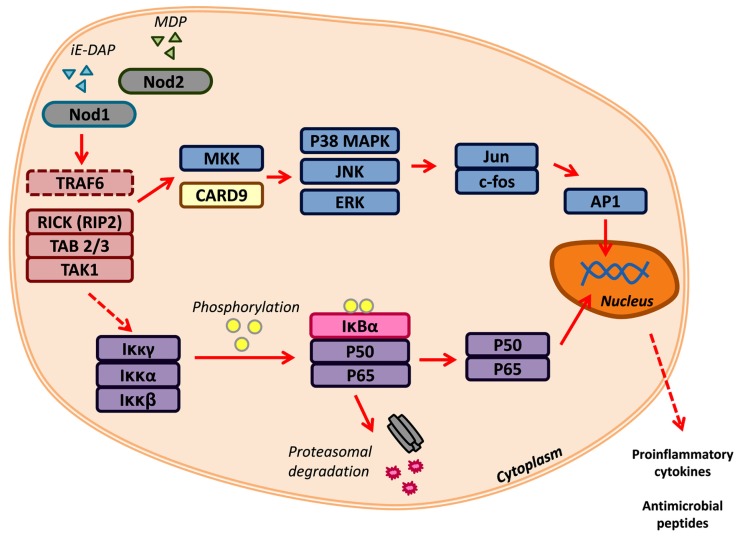

Nod1 and Nod2 are crucial for the recognition of peptidoglycan components (Figure 1). Signaling through Nod1 and Nod2 begins with the initiation of Nod1 by D-glutamyl-meso-diaminopimelic acid (DAP) and/or Nod2 by muramyl dipeptide (MDP; Chamaillard et al., 2003; Girardin et al., 2003a). While the NOD portion acts as a receiver in the presence of these pathogenic molecules, the effector CARD domain(s) of Nod1 and Nod2 perpetuate the signal transduction by interacting with receptor-interacting serine/threonine protein kinase-2 (RIP2/RICK; Kobayashi et al., 2002). Classically, RIP2/RICK is polyubiquitinated by TNF receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), this signal is required for the recruitment of the adaptor molecules TAK1-binding protein 2 and 3 (TAB2/3) and activation of TAK1 (Besse et al., 2007). Together this forms the TGF-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) complex that promotes the degradation of the inhibitor of nuclear factor (NF)-κB, thereby allowing the translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus. This is only one signaling cascade that is activated by Nod1/2, the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) pathway is another branch that can be driven by these NLRs (Pauleau and Murray, 2003; Park et al., 2007). Nod1 and Nod2 can activate three key MAPK: extracellular signal-related kinases (ERK), Jun amino-terminal kinases (JNK), and p38. The latter two can also be signaled by Nod2 through the adaptor caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 9 (CARD9; Colonna, 2007). The activation of each pathway results in the expression of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as cytokines and antimicrobial peptides. Nod1 and Nod2 can be regulated by A20-mediated ubiquitin modifications and caspase-12 inhibition of RIPK2-TRAF6 complex formation (Hitotsumatsu et al., 2008; LeBlanc et al., 2008).

FIGURE 1.

Nod1 and Nod2 signaling. Nod1 and Nod2 are activated by the peptidoglycan components iE-DAP and MDP, respectively. Recognition of PAMPs triggers TRAF6, RICK/RIP2, TAB 2/3, and TAK1. These can signal downstream to two major signaling networks: (1) MAP kinase and the (2) NF-κB pathways. Transcription factors, such as AP1 and the NF-κB complex (p50/p65), translocate to the nucleus to promote the transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines and antimicrobial peptides.

Recent developments have identified a new role for Nod1 and Nod2 in the recognition of pathogens lacking peptidoglycan. Studies have reported that Nod proteins can respond to protozoan parasites, like Toxoplasma gondii (Shaw et al., 2009). Surprisingly, Nod2 has been shown to respond to single-stranded RNA (Sabbah et al., 2009). The activation of Nod2 in this case is dependent upon the mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein MAVS and results in the facilitation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) mediated interferon (IFN) gene expression. Another protective measure that Nod1 and Nod2 are involved in is the induction of autophagy related 16-Like 1 (ATG16L1)-dependent autophagy in response to bacterial invasion, such is the case with Listeria monocytogenes (Travassos et al., 2010). Nod1 and Nod2 are gradually revealing their complex nature. Most commonly acknowledged as a sensor for peptidoglycan molecules, there is also debate that Nod1 and Nod2 may possess regulatory abilities (Murray, 2005). Studies regarding Nod1 and Nod2 function are continuously being assessed in order to develop a comprehensive understanding of these key proteins.

INFLAMMASOME

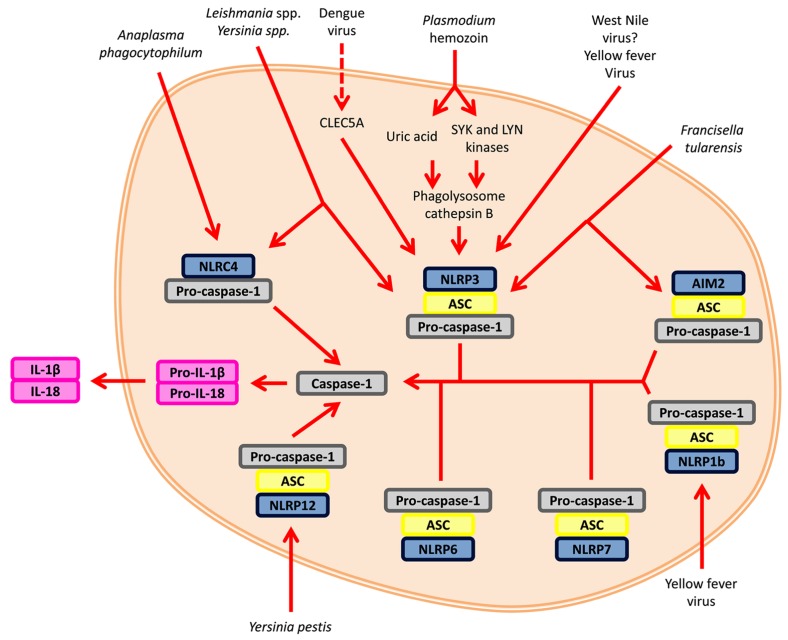

The inflammasome is a potent innate immune structure characterized by its ability to activate pro-caspase-1 in response to PAMPs or DAMP (Figure 2). The inflammasome scaffold is created by the oligomerization and recruitment of several proteins. One component, the receptor, defines the inflammasome; it can either originate from the NLR family or contain the HIN-200 domain (Lamkanfi and Dixit, 2011). Depending upon the receptor type, the adaptor molecule ASC may or may not be implicated. Since ASC possesses both a pyrin and CARD domain, it facilitates the association between the CARD-containing pro-caspase-1 and a receptor lacking the CARD domain (Schroder and Tschopp, 2010). Classically, inflammasome-mediated cytokine secretion is the product of a two-tiered signaling system (Figure 2; Franchi et al., 2012). The first signal concerns the activation the NF-κB pathway in order to promote the gene expression of IL-1β and IL-18 and other pro-inflammatory genes, such as Nlrp3. The second signal involves the assembly of the inflammasome, which results in the secretion of the abovementioned cytokines. Common to all canonical inflammasomes is the presence of the enzyme pro-caspase-1. Caspase-1 is responsible for the maturation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18 and the inflammation-related cell death process termed pyroptosis (Davis et al., 2011). Other caspases have also been shown to be involved in the inflammasome signaling pathway. Caspase-11 was recently discovered to modulate caspase-1 in response to certain Gram-negative bacteria, such as Citrobacter rodentium (Kayagaki et al., 2011; Rathinam et al., 2012). Another non-canonical inflammasome involves caspase-8. Caspase-8 is a negative regulator of pro-inflammatory NLRP3 inflammasome activity (Kang et al., 2013). During macrophage infection with Francisella tularensis subspecies novicida, caspase-8 can form a complex with AIM2 and ASC (Pierini et al., 2012). Caspase-8 associates with dectin-1 in the presence of fungi and mycobacteria (Gringhuis et al., 2012). Caspase-5 can also bind with an inflammasome, namely NLRP1 (Martinon et al., 2002). Not only can caspases bind to the inflammasome, they can also be cleaved by the caspase-1 component of the protein scaffold, similar to IL-1β. This phenomenon is seen in caspase-7 activation by caspase-1 during Legionella pneumophila infection (Akhter et al., 2009). Taken together, multiple checkpoints are crucial for inflammasome regulation due to its strength as a pro-inflammatory initiator.

FIGURE 2.

Inflammasome signaling. The inflammasome is activated by two signals. The first signal (not shown) involves the recognition of an agonist/PAMP by a receptor, such as TLRs, and upregulates transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines and key NLRs. Signal two is the initiation of the inflammasome itself. Various inflammasomes can be activated by vector-borne pathogens. The activation and oligomerization of the inflammasomes converge upon the activation of caspase-1 and the maturation of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1β and IL-18.

RECOGNITION OF VECTOR-BORNE PATHOGENS BY NLRs

Medically relevant vector-borne pathogens have plagued the health of individuals all over the globe (Table 1). Even more concerning is the rate at which these diseases are escalating and claiming the lives of thousands of people (Hotez et al., 2009). The relationship between these daunting pathogens and recognition by NLRs is not fully understood.

NOD1 AND NOD2

Being one of the first NLRs discovered, many studies have been aimed to the role of Nod1 in the context of bacterial pathogenesis (Chamaillard et al., 2003; Girardin et al., 2003b; Ray et al., 2009). Research involving the sensing of bacteria in the intracellular compartment of a wide range of cell types has dominated the Nod1 field. However, Silva et al. (2010) were able to classify Nod1 as a crucial component for the resistance to the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi. T. cruzi is transmitted by the kissing bug, Rhodnius prolixus, primarily in Latin American countries. It is the causative agent of Chagas disease, which can be characterized by fever, edema, or inflammation in the heart and/or brain (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010). These authors observed, through the use of Nod1-/- and Nod2-/- mice, that IL-12 and TNF-α levels were reduced after infection. Since nitric oxide is a key factor for T. cruzi containment, interferon gamma (IFN-γ) was used to treat Nod1-/- and Nod2-/- bone marrow-derived macrophages. This resulted in a high load of parasites for the Nod1-/- macrophage, highlighting the specificity of Nod1, not Nod2, for T. cruzi infection.

B. burgdorferi is a spirochete transmitted by Ixodes spp. Infection by B. burgdorferi causes Lyme disease, the most common vector-borne disease north of the equator (Parola and Raoult, 2001; Lindgren and Jaenson, 2006; Berende et al., 2010). Lyme disease can manifest into a three stage infection: (1) erythema migrans is characterized by localized infection, (2) early disseminated infection results in inflamed joints and CNS, and (3) persistent infection, which consists of chronic inflammation of joints and the CNS and sensory polyneuropathy (Berende et al., 2010). It has been established that TLR2 plays an important role in the recognition of B. burgdorferi. Recent evidence points to Nod2 as an important factor in the sensing of this pathogenic spirochete (Petnicki-Ocwieja et al., 2011). Nod2 is upregulated in mouse microglia and individuals with mutated Nod2 were not able to mount an efficient cytokine response after infection with B. burgdorferi (Sterka et al., 2006; Oosting et al., 2010). The plague causing vector-borne pathogen Yersinia has also been shown to be recognized by Nod2 (Ferwerda et al., 2009).

Nod1 and Nod2 also appear to possess redundancy because they are able to detect similar arthropod-borne pathogens. Individuals who encountered an antigenic component from the Brugia malayi adult demonstrated an increase in Nod1 and Nod2 expression (Babu et al., 2009). Brugia and Wuchereria bancrofti species can cause lymphatic filariasis which can manifest as elephantiasis, lymphedema, and hydrocele (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013a). Independently, the obligate intracellular pathogen Anaplasma phagocytophilum, transmitted by Ixodes spp., is involved in the increased expression of Rip2, a critical molecule in Nod1 and Nod2 signaling (Sukumaran et al., 2012). More importantly, the ability for Rip2-/- mice to control and clear A. phagocytophilum was severely hindered. The Plasmodium parasite is also detected by Nod proteins (Coban et al., 2007). Certain instances result in upregulation of Nod2 in the presence of Plasmodium sporozoites, while in other cases Nod1 and Nod2 confer changes in cytokines but do not promote survival after infection (Ockenhouse et al., 2006; Finney et al., 2009).

NLRP1 INFLAMMASOME

The NLRP1 inflammasome was the first to be characterized (Martinon et al., 2002). NLRP1 has been shown to recognize the Bacillus anthracis lethal toxin and, like Nod2, MDP (Boyden and Dietrich, 2006; Faustin et al., 2007). The activation of pro-caspase-1 activity elicited by these bacterial components is distinct. Cleavage of the NLRP1 inflammasome by the lethal toxin is required for inflammasome activation, as mutation of NLRP1 demonstrates reduced caspase-1 activation (Levinsohn et al., 2012). On the other hand, MDP activation of NLRP1 requires the presence of MDP and ribonucleoside triphosphates (Faustin et al., 2007). It was observed that a cohort given a yellow fever vaccine showed upregulation of caspase-1 and caspase-5. These two caspases are present in the NLRP1 inflammasome. This indicates that the NLRP1 inflammasome may be activated by the yellow fever virus. This virus is transmitted by the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Inoculation of yellow fever virus by a mosquito can lead to mild reactions, such as fever, ache, and nausea, or more serious ones, such as organ failure (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011a). More studies need to be done in order to clarify what components trigger a NLRP1 inflammasome response to the yellow fever virus.

NLRP3 INFLAMMASOME

Of all NLRs, NLRP3, currently, has the most known associations with vector-borne diseases. It is well known that NLRP3 is triggered by three signals: (1) potassium efflux, (2) phagolysosomal disruption, and (3) ROS production (Schroder and Tschopp, 2010). Recently, mitochondrial DNA and calcium levels were suggested to be other activators of the NLRP3 inflammasome (Rossol et al., 2012; Shimada et al., 2012). The malarial parasite has demonstrated the ability to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome through the crystalline particle hemozoin (Dostert et al., 2009; Griffith et al., 2009; Shio et al., 2009). Monosodium urate (uric acid), together with hemozoin, has also been reported to result in pro-inflammatory reactions through the MAPK signaling pathway (Griffith et al., 2009; Shio et al., 2009). Hemozoin is a byproduct of heme detoxification by Plasmodium. The phagocytosis of hemozoin initiates signals through spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) and v-yes-1 Yamaguchi sarcoma viral related oncogene homolog (Lyn), tyrosine kinases, in order to initiate the NLRP3 inflammasome (Shio et al., 2009). Another mosquito-borne pathogen, the dengue virus is transmitted by A. aegypti or A. albopictus. Dengue virus can cause dengue fever or dengue shock syndrome. Wu et al. (2013) elucidated that, in human macrophages, dengue virus can signal through Syk-coupled C-type lectin 5A (CLEC5A) to induce NLRP3-mediated cytokine secretion and pyroptosis. Though not much is known about yellow fever virus and the inflammasome, one study shows that vaccination with a live attenuated yellow fever vaccine is able to increase the expression caspase-1 associated with the NLRP3 inflammasome (Gaucher et al., 2008).

IL-1β is crucial for the protection of the CNS from West Nile neuroinvasive disease (Ramos et al., 2012). Moreover, it was shown that this phenomenon is specific for NLRP3 inflammasome mediated IL-1β secretion. Additionally, IL-1β combined with type I IFN results in the reduction of West Nile virus infection. Non-mosquito-borne pathogens also influence NLRP3 activity. Infection by Leishmania spp., transmitted by the sandfly Lutzomyia longipalpis, can result in skin, organ, and/or mucosal complications (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013b). In murine macrophages, Sani et al. (2013) found that the expression of Nlrp3 is increased after exposure to Leishmania major. Furthermore, Lima-Junior et al. (2013) confirmed NLRP3 activation after L. amazonensis infection that led to the protective restriction of parasites. Another non-mosquito-borne pathogen is Francisella tularensis, which is commonly transmitted by ticks. Tularemia can cause sores and respiratory complications. Uniquely in human leukemia cell line (THP-1) but not in mouse cells, Francisella is capable of activating the NLRP3 inflammasome (Atianand et al., 2011). Supporting this, the use of NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitors and Nlrp3 siRNA revealed that the IL-1β secretion in response to Francisella was lessened. The type III secretion system (T3SS) from Yersinia pestis is also able to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in vitro (Brodsky et al., 2010). With the addition of KCl, the NLRP3 inflammasome activity was nullified. However, other inflammasomes are also involved in the detection of Yersinia as well. Although Nod2 has been acknowledged as a protein that recognizes Borrelia, there is controversy on whether inflammasomes are activated in response to this vector-borne pathogen. Though independent of the NLRP3 inflammasome, multiple groups have found that caspase-1 is activated after exposure to Borrelia while another group was unable to detect caspase-1 dependence (Cruz et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2009; Oosting et al., 2011).

NLRC4 INFLAMMASOME

The CARD-containing NLRC4 inflammasome mediates pro-inflammatory responses to the recognition of flagellin and type III/IV secretion systems from gram-negative bacteria (Schroder and Tschopp, 2010). NLRC4, also called IPAF, inflammasome confer protection against bacteria, such as Salmonella typhimurium and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Miao et al., 2008). It is also able to directly and indirectly associate with pro-caspase-1, via its CARD domain or the adaptor molecule ASC, respectively. Additionally, another level of specificity is added by the NLRC4 interaction with NAIP5 or NAIP2, which modifies NLRC4 activation in response to flagellin and the type III secretion system (T3SS), respectively (Zhao et al., 2011). As of yet, NLRC4 has been implicated in two vector-borne illnesses, Human granulocytic anaplasmosis and Leishmaniasis. Nlrc4-/- mice showed heightened susceptibility to Anaplasma phagocytophilum and decreased levels of IL-18 relative to the wild-type. However, the effect of NLRC4 was partial; thereby, suggesting additional mechanisms of inflammasome activation (Pedra et al., 2007). Sani et al. (2013) found that Nlrc4 expression increased after exposing macrophages to L. major. As was previously mentioned, Y. pestis is able to activate several inflammasomes, and it is also able to combat this recognition with effector proteins (Brodsky et al., 2010). The NLRC4 inflammasome is another protein complex involved in the recognition of Y. pestis T3SS (Brodsky et al., 2010).

NLRP12 INFLAMMASOME

The NLRP12 inflammasome is a member of the NLR family that has been suggested to reduce and potentiate inflammatory cytokine secretion (Wang et al., 2002; Lich et al., 2008; Arthur et al., 2010; Zaki et al., 2011; Allen et al., 2012). Currently, NLRP12 has been shown to play a role in hereditary period fever syndromes, but very little is known with respect to vector-borne diseases. Vladimer et al. (2012) discovered that NLRP12 regulates IL-18 secretion in response to Y. pestis. More specifically, after infection of Nlrp12-/- mice with Y. pestis, they observed an increase in bacterial load and death which was associated with decreased levels of IL-18 and IL-1β.

NON-NLR INFLAMMASOME

The AIM2 (absent in melanoma 2) inflammasome does not contain the typical NLR domain as do other inflammasomes. Rather, it carries the HIN-200 domain (Case, 2011). In particular, AIM2 is known for sensing double stranded DNA in the cytosol (Bauernfeind et al., 2011). The formation of the AIM2 inflammasome consists of the AIM2 receptor, ASC, and pro-caspase-1. Upon recognition of cytoplasmic DNA, AIM2 is able to coordinate pyroptosis and the release of IL-1β and IL-18 via pro-caspase-1 maturation (Davis et al., 2011). Of the vector-borne pathogens discussed in this review, AIM2 is able to recognize F. tularensis in mouse macrophages (Fernandes-Alnemri et al., 2010). Moreover, IRF3 is needed for a type 1 IFN response to help mount an effective AIM2-dependent activation after F. tularensis infection (Fernandes-Alnemri et al., 2010).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The importance of NLRs and vector saliva has been demonstrated through numerous elaborate studies. Further research in this area has the potential to reveal more intricate relationships, as well as the salivary effectors that can modulate these interactions. This review has highlighted the role of NLRs and salivary components in vector-borne diseases. Due to the vast amount of literature available in the field of arthropod saliva and the diverse mechanisms of vertebrate-host immunomodulation, we elected to focus only on those pertinent to the vectors discussed here. Elucidating the mechanisms behind NLR recognition and salivary modulation of pathogenic agents will shed light on the fundamental basis of pathogen-vector-host interactions. Additionally, it should provide novel targets for therapeutic intervention of devastating vector-borne diseases.

Based on our current knowledge, we suggest that arthropod saliva could regulate NLR inflammasome activity during pathogen transmission or after infection. Vector saliva has been shown to minimize reactive oxygen species (ROS; Guo et al., 2009). ROS has been identified as an agonist for inflammasome activation; therefore salivary proteins can potentially reduce ROS to decrease inflammasome activity. Another mechanism by which arthropod saliva can hinder the inflammasome is by acting on caspase-1. Caspase-1, the key enzymatic component of the inflammasome, is a member of the cysteine protease family. Salivary proteins have demonstrated the ability to target cysteine proteases, such as sialostatin L inhibition of cathepsin L (Kotsyfakis et al., 2006). Of interest, the same protein exhibits anti-inflammatory effects. Thus, it is plausible that sialostatins block caspase-1 activation and subsequent IL-1β and IL-18 secretion. A better understanding of salivary components regulating vector-borne pathogens and NLR interaction could allow us to gain a foothold on controlling these infectious diseases.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Olivia S. Sakhon, Maiara S. Severo, Michail Kotsyfakis, and Joao H. F. Pedra wrote the manuscript. Olivia S. Sakhon created the tables and figures.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a public health service grant R01 AI093653 to Joao H. F. Pedra; and by an International Fellowship from the American Association of University Women to Maiara S. Severo.

REFERENCES

- Ader D. B., Celluzzi C., Bisbing J., Gilmore L., Gunther V., Peachman K. K. (2004). Modulation of dengue virus infection of dendritic cells by Aedes aegypti saliva. Viral Immunol. 17 252–265 10.1089/0882824041310496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhter A., Gavrilin M. A., Frantz L., Washington S., Ditty C., Limoli D. (2009). Caspase-7 activation by the Nlrc4/Ipaf inflammasome restricts Legionella pneumophila infection. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000361 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alarcon-Chaidez F. J., Boppana V. D., Hagymasi A. T., Adler A. J., Wikel S. K. (2009). A novel sphingomyelinase-like enzyme in Ixodes scapularis tick saliva drives host CD4 T cells to express IL-4. Parasite Immunol. 31 210–219 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2009.01095.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen I. C., Wilson J. E., Schneider M., Lich J. D., Roberts R., Arthur J. C. (2012). NLRP12 suppresses colon inflammation and tumorigenesis through the negative regulation of noncanonical NF-κB signaling. Immunity 36 742–754 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen J. F., Gudderra N. P., Francischetti I. M. B, Ribeiro J. M. C. (2005). The role of salivary lipocalins in blood feeding by Rhodnius prolixus. Arch. Insect Biochem. Physiol. 58 97–105 10.1002/arch.20032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anguita J., Ramamoorthi N., Hovius J. W. R., Das S., Thomas V., Persinski R. (2002). Salp15, an Ixodes scapularis salivary protein, inhibits CD4(+) T cell activation. Immunity 16 849–859 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00325-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki M. P., Carrera-Silva E. A., Cuervo H., Fresno M., Gironès N., Gea S. (2012). Nonimmune cells contribute to crosstalk between immune cells and inflammatory mediators in the innate response to Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J. Parasitol. Res. 2012 737324 10.1155/2012/737324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur J. C., Lich J. D., Ye Z., Allen I. C., Gris D., Wilson J. E. (2010). NLRP12 controls dendritic and myeloid cell migration to affect contact hypersensitivity. J. Immunol. 185 4515–4519 10.4049/jimmunol.1002227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atianand M. K., Duffy E. B., Shah A., Kar S., Malik M., Harton J. (2011). Francisella tularensis reveals a disparity between human and mouse NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J. Biol. Chem. 286 39033–39042 10.1074/jbc.M111.244079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babu S., Bhat S. Q., Pavan Kumar N., Lipira A. B., Kumar S., Karthik C. (2009). Filarial lymphedema is characterized by antigen-specific Th1 and Th17 proinflammatory responses and a lack of regulatory T cells. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 3:e420 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauernfeind F., Ablasser A., Bartok E., Kim S., Schmid-Burgk J., Cavlar T. (2011). Inflammasomes: current understanding and open questions. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 68 765–783 10.1007/s00018-010-0567-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaufays J., Adam B., Menten-Dedoyart C., Fievez L., Grosjean A., Decrem Y. (2008). Ir-LBP, an Ixodes ricinus tick salivary LTB4-binding lipocalin, interferes with host neutrophil function. PLoS ONE 3:e3987 10.1371/journal.pone.0003987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berende A., Oosting M., Kullberg B.-J., Netea M. G, Joosten L. A B. (2010). Activation of innate host defense mechanisms by Borrelia. Eur. Cytokine Netw. 21 7–18 10.1684/ecn.2009.0179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman D. K., Ramachandra R. N., Wikel S. K. (1995). Dermacentor andersoni: salivary gland proteins suppressing T-lymphocyte responses to concanavalin A in vitro. Exp. Parasitol. 81 262–271 10.1006/expr.1995.1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besse A., Lamothe B., Campos A. D., Webster W. K., Maddineni U., Lin S.-C. (2007). TAK1-dependent signaling requires functional interaction with TAB2/TAB3. J. Biol. Chem. 282 3918–3928 10.1074/jbc.M608867200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger N., Bulet P., Lowenberger C. (2006). Antimicrobial peptides in the interactions between insects and flagellate parasites. Trends Parasitol. 22 262–268 10.1016/j.pt.2006.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyden E. D., Dietrich W. F. (2006). Nalp1b controls mouse macrophage susceptibility to anthrax lethal toxin. Nat. Genet. 38 240–244 10.1038/ng1724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodsky I. E., Palm N. W., Sadanand S., Ryndak M. B., Fayyaz S., Flavell R. A. (2010). A Yersinia secreted effecor protein promotes virulence by preventing inflammasome recognition of the type III secretion system. Cell Host Microbe 7 376–387 10.1016/j.chom.2010.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo E., Mans B. J., Andersen J. F, Ribeiro J. M. C. (2006). Function and evolution of a mosquito salivary protein family. J. Biol. Chem. 281 1935–1942 10.1074/jbc.M510359200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Case C. L. (2011). Regulating caspase-1 during infection: roles of NLRs, AIM2, and ASC. Yale J. Biol. Med. 84 333–343 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010). Parasites – American Trypanosomiasis. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/chagas/disease.html (last modified November 2, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011a). Yellow Fever. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/yellowfever/ (last modified December 13, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2011b). Tularemia Statistics. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tularemia/statistics/ (last modified September 29, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012a). Dengue. Availble at: http://www.cdc.gov/dengue/epidemiology/ (last modified September 27, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012b). Lyme Disease Data. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/index.html (last modified September 10, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012c). Plague. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/plague/faq/ (last modified July 24, 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013a). Parasites – Lymphatic Filariasis. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/lymphaticfilariasis/gen_info/faqs.html (last modified June 14, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013b). Parasites – Leishmaniasis. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/leishmaniasis/disease.html (last modified January 10, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013c). Cases of West Nile Human Disease. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/westnile/qa/cases.htm (last modified August 13, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013d). Annual Cases of Anaplasmosis in the United States. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/anaplasmosis/stats/#casesbyyear (last modified July 8, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy. (2013). Tularemia: Current, Comprehensive Information on Pathogenesis, Microbiology, Epidemiology, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prophylaxis. Available at: http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/cidrap/content/bt/tularemia/biofacts/tularemiafactsheet.html#_Public_HealthReporting_1 (last modified February 27, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Chamaillard M., Hashimoto M., Horie Y., Masumoto J., Qiu S., Saab L. (2003). An essential role for NOD1 in host recognition of bacterial peptidoglycan containing diaminopimelic acid. Nat. Immunol. 4 702–707 10.1038/ni945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne D. E. (2005). Antihemostatic molecules from saliva of blood-feeding arthropods. Pathophysiol. Haemost. Thromb. 34 221–227 10.1159/000092428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Severo M. S., Sohail M., Sakhon O. S., Wikel S. K., Kotsyfakis M. (2012). Ixodes scapularis saliva mitigates inflammatory cytokine secretion during Anaplasma phagocytophilum stimulation of immune cells. Parasit. Vectors 5 1 10.1186/1756-3305-5-229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmelar J., Calvo E., Pedra J. H. F., Francischetti I. M. B., Kotsyfakis M. (2012). Tick salivary secretion as a source of antihemostatics. J. Proteomics 75 3842–3854 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.04.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chmelar J., Oliveira C. J., Rezacova P., Francischetti I. M. B., Kovarova Z., Pejler G. (2011). A tick salivary protein targets cathepsin G and chymase and inhibits host inflammation and platelet aggregation. Blood 117 736–744 10.1182/blood-2010-06-293241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coban C., Ishii K. J., Horii T., Akira S. (2007). Manipulation of host innate immune responses by the malaria parasite. Trends Microbiol. 15 271–278 10.1016/j.tim.2007.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna M. (2007). All roads lead to CARD9. Nat. Immunol. 8 554–555 10.1038/ni0607-554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz A. R., Moore M. W., La Vake C. J., Eggers C. H., Salazar J. C., Radolf J. D. (2008). Phagocytosis of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease spirochete, potentiates innate immune activation and induces apoptosis in human monocytes. Infect. Immun. 76 56–70 10.1128/IAI.01039-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J., Narasimhan S., Zhang L., Liu L., Wang P., Fikrig E. (2010). Tick histamine release factor is critical for Ixodes scapularis engorgement and transmission of the lyme disease agent. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001205 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daix V., Schroeder H., Praet N., Georgin J.-P., Chiappino I., Gillet L. (2007). Ixodes ticks belonging to the Ixodes ricinus complex encode a family of anticomplement proteins. Insect Mol. Biol. 16 155–166 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2006.00710.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S., Banerjee G., DePonte K., Marcantonio N., Kantor F. S., Fikrig E. (2001). Salp25D, an Ixodes scapularis antioxidant, is 1 of 14 immunodominant antigens in engorged tick salivary glands. J. Infect. Dis. 184 1056–1064 10.1086/323351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis B. K., Wen H, Ting J. P.-Y. (2011). The inflammasome NLRs in immunity, inflammation, and associated diseases. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 29 707–735 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demento S. L., Eisenbarth S. C., Foellmer H. G., Platt C., Caplan M. J., Mark Saltzman W. (2009). Inflammasome-activating nanoparticles as modular systems for optimizing vaccine efficacy. Vaccine 27 3013–3021 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.03.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Déruaz M., Frauenschuh A., Alessandri A. L., Dias J. M., Coelho F. M., Russo R. C. (2008). Ticks produce highly selective chemokine binding proteins with antiinflammatory activity. J. Exp. Med. 205 2019–31 10.1084/jem.20072689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Silva A. M., Tyson K. R., Pal U. (2009). Molecular characterization of the tick-Borrelia interface. Front. Biosci. 14:3051–3063 10.2741/3434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dostert C., Guarda G., Romero J. F., Menu P., Gross O., Tardivel A. (2009). Malarial hemozoin is a Nalp3 inflammasome activating danger signal. PLoS ONE 4:e6510 10.1371/journal.pone.0006510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J. F., Higgs S., Beaty B. J. (1998). Mosquito feeding-induced enhancement of Cache Valley Virus (Bunyaviridae) infection in mice. J. Med. Entomol. 35 261–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustin B., Lartigue L., Bruey J.-M., Luciano F., Sergienko E., Bailly-Maitre B. (2007). Reconstituted NALP1 inflammasome reveals two-step mechanism of caspase-1 activation. Mol. Cell 25 713–724 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Alnemri T., Yu J.-W., Juliana C., Solorzano L., Kang S., Wu J. (2010). The AIM2 inflammasome is critical for innate immunity to Francisella tularensis. Nat. Immunol. 11 385–393 10.1038/ni.1859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferwerda B., McCall M. B. B., de Vries M. C., Hopman J., Maiga B., Dolo A. (2009). Caspase-12 and the inflammatory response to Yersinia pestis. PLoS ONE 4:e6870 10.1371/journal.pone.0006870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney C. A. M., Lu Z., Lebourhis L., Philpott D. J., Kain K. C. (2009). Disruption of Nod-like receptors alters inflammatory response to infection but does not confer protection in experimental cerebral malaria. Infect. Immun. 80 718–722 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine A., Diouf I., Bakkali N., Missé D., Pagès F., Fusai T. (2011). Implication of haematophagous arthropod salivary proteins in host-vector interactions. Parasit. Vectors 4 187 10.1186/1756-3305-4-187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi L., Muñoz-Planillo R, Núñez G. (2012). Sensing and reacting to microbes through the inflammasomes. Nat. Immunol. 13 325–332 10.1038/ni.2231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francischetti I. M. B., Sa-Nunes A., Mans B. J., Santos I. M, Ribeiro J. M. C. (2009). The role of saliva in tick feeding. Front. Biosci. 14:2051–2088 10.2741/3363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frauenschuh A., Power C. A., Déruaz M., Ferreira B. R., Silva J. S., Teixeira M. M. (2007). Molecular cloning and characterization of a highly selective chemokine-binding protein from the tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus. J. Biol. Chem. 282 27250–27258 10.1074/jbc.M704706200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frischknecht F. (2007). The skin as interface in the transmission of arthropod-borne pathogens. Cell Microbiol. 9 1630–1640 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00955.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg R., Juncadella I. J., Ramamoorthi N., Ashish Ananthanarayanan S. K., Thomas V. (2006). CD4 is the receptor for the tick saliva immunosuppressor, Salp15. J. Immunol. 177 6579–6583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaucher D., Therrien R., Kettaf N., Angermann B. R., Boucher G., Filali-Mouhim A. (2008). Yellow fever vaccine induces integrated multilineage and polyfunctional immune responses. J. Exp. Med. 205 3119–31131 10.1084/jem.20082292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazos-Lopes F., Mesquita R. D., Silva-Cardoso L., Senna R., Silveira A. B., Jablonka W. (2012). Glycoinositolphospholipids from Trypanosomatids subvert nitric oxide production in Rhodnius prolixus salivary glands. PLoS ONE 7:e47285 10.1371/journal.pone.0047285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie R. D., Dolan M. C., Piesman J., Titus R. G. (2001). Identification of an IL-2 binding protein in the saliva of the Lyme disease vector tick, Ixodes scapularis. J. Immunol. 166 4319–4326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie R. D., Mbow M. L., Titus R. G. (2000). The immunomodulatory factors of bloodfeeding arthropod saliva. Parasite Immunol. 22 319–331 10.1046/j.1365-3024.2000.00309.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardin S. E., Boneca I. G., Viala J., Chamaillard M., Labigne A., Thomas G. (2003a). Nod2 is a general sensor of peptidoglycan through muramyl dipeptide (MDP) detection. J. Biol. Chem. 278 8869–8872 10.1074/jbc.C200651200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardin S. E., Travassos L. H., Hervé M., Blanot D., Boneca I. G., Philpott D. J. (2003b). Peptidoglycan molecular requirements allowing detection by Nod1 and Nod2. J. Biol. Chem. 278 41702–41708 10.1074/jbc.M307198200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith J. W., Sun T., McIntosh M. T., Bucala R. (2009). Pure hemozoin is inflammatory in vivo and activates the NALP3 inflammasome via release of uric acid. J. Immunol. 183 5208–5220 10.4049/jimmunol.0713552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gringhuis S. I., Kaptein T. M., Wevers B. A., Theelen B., van der Vlist M., Boekhout T. (2012). Dectin-1 is an extracellular pathogen sensor for the induction and processing of IL-1β via a noncanonical caspase-8 inflammasome. Nat. Immunol. 13 246–254 10.1038/ni.2222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Booth C. J., Paley M. A., Wang X., DePonte K., Fikrig E. (2009). Inhibition of neutrophil function by two tick salivary proteins. Infect. Immun. 77 2320–2329 10.1128/IAI.01507-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall L. R., Titus R. G. (1995). Vector saliva selectively modulates macrophage functions that inhibitk illing of. J. Immunol. 155 3501–3506 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannier S., Liversidge J., Sternberg J. M., Bowman A. S. (2004). Characterization of the B-cell inhibitory protein factor in Ixodes ricinus tick saliva: a potential role in enhanced Borrelia burgdoferi transmission. Immunology 113 401–408 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2004.01975.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healthline. (2013). The Plague. Available at: http://www.healthline.com/health/plague (accessed April 25, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Hitotsumatsu O., Ahmad R.-C., Tavares R., Wang M., Philpott D., Turer E. E. (2008). The ubiquitin-editing enzyme A20 restricts nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2-triggered signals. Immunity 28 381–390 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horka H., Staudt V., Klein M., Taube C., Reuter S., Dehzad N. (2012). The tick salivary protein sialostatin L inhibits the Th9-derived production of the asthma-promoting cytokine IL-9 and is effective in the prevention of experimental asthma. J. Immunol. 188 2669–2676 10.4049/jimmunol.1100529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotez P. J., Fenwick A., Savioli L., Molyneux D. H. (2009). Rescuing the bottom billion through control of neglected tropical diseases. Lancet 373 1570–1575 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60233-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovius J. W. R., de Jong M. A. W. P., den Dunnen J., Litjens M., Fikrig E., van der Poll T. (2008). Salp15 binding to DC-SIGN inhibits cytokine expression by impairing both nucleosome remodeling and mRNA stabilization. PLoS Pathog. 4:e31 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inohara N., Koseki T., del Peso L., Hu Y., Yee C., Chen S. (1999). Nod1, an Apaf-1-like activator of caspase-9 and nuclear factor-κB. J. Biol. Chem. 274 14560–14567 10.1074/jbc.274.21.14560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang T.-B., Yang S.-H., Toth B., Kovalenko A., Wallach D. (2013). Caspase-8 blocks kinase RIPK3-mediated activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Immunity 38 27–40 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz O., Waitumbi J. N., Zer R., Warburg A. (2000). Adenosine, AMP, and protein phosphatase activity in sandfly saliva. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 62 145–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushik D. K., Gupta M., Kumawat K. L., Basu A. (2012). NLRP3 inflammasome: key mediator of neuroinflammation in murine Japanese encephalitis. PLoS ONE 7:e32270 10.1371/journal.pone.0032270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayagaki N., Warming S., Lamkanfi M., Vande Walle L., Louie S., Dong J. (2011). Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature 479 117–121 10.1038/nature10558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi K., Inohara N., Hernandez L. D., Galán J. E., Núñez G., Janeway C. A. (2002). RICK/Rip2/CARDIAK mediates signalling for receptors of the innate and adaptive immune systems. Nature 416 194–199 10.1038/416194a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotsyfakis M., Horka H., Salat J., Andersen J. F. (2010). The crystal structures of two salivary cystatins from the tick Ixodes scapularis and the effect of these inhibitors on the establishment of Borrelia burgdorferi infection in a murine model. Mol. Microbiol. 77 456–470 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07220.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotsyfakis M., Karim S., Andersen J. F., Mather T. N, Ribeiro J. M. C. (2007). Selective cysteine protease inhibition contributes to blood-feeding success of the tick Ixodes scapularis. J. Biol. Chem. 282 29256–29263 10.1074/jbc.M703143200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotsyfakis M., Sá-Nunes A., Francischetti I. M. B., Mather T. N., Andersen J. F, Ribeiro J. M. C. (2006). Antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive activity of sialostatin L, a salivary cystatin from the tick Ixodes scapularis. J. Biol. Chem. 281 26298–26307 10.1074/jbc.M513010200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovats R. S., Campbell-Lendrum D. H., McMichel A. J., Woodward A, Cox J. S. H. (2001). Early effects of climate change: do they include changes in vector-borne disease? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 356 1057–1068 10.1098/rstb.2001.0894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause P. J., Grant-Kels J. M., Tahan S. R., Dardick K. R., Alarcon-Chaidez F., Bouchard K. (2009). Dermatologic changes induced by repeated Ixodes scapularis bites and implications for prevention of tick-borne infection. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 9 603–610 10.1089/vbz.2008.0091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamkanfi M., Dixit V. M. (2011). Modulation of inflammasome pathways by bacterial and viral pathogens. J. Immunol. 187 597–602 10.4049/jimmunol.1100229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc P. M., Yeretssian G., Rutherford N., Doiron K., Nadiri A., Zhu L. (2008). Caspase-12 modulates NOD signaling and regulates antimicrobial peptide production and mucosal immunity. Cell Host Microbe 3 146–157 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leboulle G., Crippa M., Decrem Y., Mejri N., Brossard M., Bollen A. (2002). Characterization of a novel salivary immunosuppressive protein from Ixodes ricinus ticks. J. Biol. Chem. 277 10083–10089 10.1074/jbc.M111391200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinsohn J. L., Newman Z. L., Hellmich K. A., Fattah R., Getz M. A., Liu S. (2012). Anthrax lethal factor cleavage of Nlrp1 is required for activation of the inflammasome. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002638 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lich J. D., Ting J. P., Carolina N., Hill C. (2008). Monarch-1/PYPAF7 and other CATERPILLER (CLR, NOD, NLR) proteins with negative regulatory functions. Microbes Infect. 9 672–676 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima-Junior D. S., Costa D. L., Carregaro V., Cunha L. D., Silva A. L. N., Mineo T. W. P. (2013). Inflammasome-derived IL-1β production induces nitric oxide-mediated resistance to Leishmania. Nat. Med. 19 909–15 10.1038/nm.3221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren E., Jaenson T. G. (2006). “Lyme borreliosis in Europe: influences of climate and climate change, epidemiology, ecology and adaptation measures, ” in Climate Change and Adaptation Strategies for Human Health eds Menne B., Menne K. L. Ebi. Geneva: World Health Organization Europe [Google Scholar]

- Liu N., Belperron A. A., Booth C. J., Bockenstedt L. K. (2009). The caspase 1 inflammasome is not required for control of murine Lyme borreliosis. Infect. Immun. 77 3320–3327 10.1128/IAI.00100-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lögdberg L., Wester L. (2000). Immunocalins: a lipocalin subfamily that modulates immune and inflammatory responses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1482 284–297 10.1016/S0167-4838(00)00164-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mans B. J, Francischetti I. M. B. (2011). Toxins and Hemostasis. Berlin: Springer 21–44 [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F., Burns K., Tschopp J. (2002). The inflammasome: a molecular platform triggering activation of inflammatory caspases and processing of pro-IL-β. Mol. Cell 10 417–426 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00599-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw E. A, O’Neill S. L. (2013). Beyond insecticides: new thinking on an ancient problem. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11 181–193 10.1038/nrmicro2968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MD Guidelines. (2013). Tularemia. Available at: http://www.mdguidelines.com/tularemia (accessed April 25, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Medscape. (2013). Tularemia Epidemiology. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/230923-overview#a0199 (accessed April 25, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Mejia J. S., Bishop J. V., Titus R. G. (2006). Is it possible to develop pan-arthropod vaccines? Trends Parasitol. 22 367–370 10.1016/j.pt.2006.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao E. A., Ernst R. K., Dors M., Mao D. P., Aderem A. (2008). Pseudomonas aeruginosa activates caspase 1 through Ipaf. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 2562–2567 10.1073/pnas.0712183105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira L. O., Zamboni D. S. (2012). NOD1 and NOD2 signaling in infection and inflammation. Front. Immunol. 3:328 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulenga A., Macaluso K. R., Simser J. A., Azad A. F. (2003). The American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis, encodes a functional histamine release factor homolog. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 33 911–919 10.1016/S0965-1748(03)00097-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray P. J. (2005). NOD proteins: an intracellular pathogen-recognition system or signal transduction modifiers? Curr. Opin. Immunol. 17 352–358 10.1016/j.coi.2005.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nürnberger T., Brunner F., Kemmerling B., Piater L. (2004). Innate immunity in plants and animals: striking similarities and obvious differences. Immunol. Rev. 198 249–266 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.0119.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ockenhouse C. F., Hu W., Kester K. E., Cummings J. F., Stewart A., Heppner D. G. (2006). Common and divergent immune response signaling pathways discovered in peripheral blood mononuclear cell gene expression patterns in presymptomatic and clinically apparent malaria. Infect. Immun. 74 5561–5573 10.1128/IAI.00408-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira C. J. F., Sá-Nunes A., Francischetti I. M. B., Carregaro V., Anatriello E., Silva J. S. (2011). Deconstructing tick saliva: non-protein molecules with potent immunomodulatory properties. J. Biol. Chem. 286 10960–10969 10.1074/jbc.M110.205047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosting M., Berende A., Sturm P., Ter Hofstede H. J. M., de Jong D. J., Kanneganti T.-D. (2010). Recognition of Borrelia burgdorferi by NOD2 is central for the induction of an inflammatory reaction. J. Infect. Dis. 201 1849–1858 10.1086/652871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosting M., van de Veerdonk F. L., Kanneganti T.-D., Sturm P., Verschueren I., Berende A. (2011). Borrelia species induce inflammasome activation and IL-17 production through a caspase-1-dependent mechanism. Eur. J. Immunol. 41 172–181 10.1002/eji.201040385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osorio J. E., Godsey M. S., Defoliart G. R., Yuill T. M. (1996). La Crosse viremias in white-tailed deer and chipmunks exposed by injection or mosquito bite. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 54 338–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paesen G. C., Adams P. L., Harlos K., Nuttall P. A., Stuart D. I. (1999). Tick histamine-binding proteins: isolation, cloning, and three-dimensional structure. Mol. Cell 3 661–671 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80359-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.-H., Kim Y.-G., McDonald C., Kanneganti T.-D., Hasegawa M., Body-Malapel M. (2007). RICK/RIP2 mediates innate immune responses induced through Nod1 and Nod2 but not TLRs. J. Immunol. 178 2380–2386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parola P., Raoult D. (2001). Ticks and tickborne bacterial diseases in humans: an emerging infectious threat. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32 897–928 10.1086/319347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauleau A.-L., Murray P. J. (2003). Role of Nod2 in the response of macrophages to Toll-like receptor agonists. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 7531–7539 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7531-7539.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedra J. H. F., Sutterwala F. S., Sukumaran B., Ogura Y., Qian F., Montgomery R. R. (2007). ASC/PYCARD and caspase-1 regulate the IL-18/IFN-γ axis during Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection. J. Immunol. 179 4783–4791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petnicki-Ocwieja T., DeFrancesco A. S., Chung E., Darcy C. T., Bronson R. T., Kobayashi K. S. (2011). Nod2 suppresses Borrelia burgdorferi mediated murine lyme arthritis and carditis through the induction of tolerance. PLoS ONE 6:e17414 10.1371/journal.pone.0017414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierini R., Juruj C., Perret M., Jones C. L., Mangeot P., Weiss D. S. (2012). AIM2/ASC triggers caspase-8-dependent apoptosis in Francisella-infected caspase-1-deficient macrophages. Cell Death Differ. 19 1709–1721 10.1038/cdd.2012.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston S. G., Majtán J., Kouremenou C., Rysnik O., Burger L. F., Cabezas Cruz A. (2013). Novel immunomodulators from hard ticks selectively reprogramme human dendritic cell responses. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003450 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevot P.-P., Beschin A., Lins L., Beaufays J., Grosjean A., Bruys L. (2009). Exosites mediate the anti-inflammatory effects of a multifunctional serpin from the saliva of the tick Ixodes ricinus. FEBS J. 276 3235–3246 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07038.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramamoorthi N., Narasimhan S., Pal U., Bao F., Yang X. F., Fish D. (2005). The Lyme disease agent exploits a tick protein to infect the mammalian host. Nature 436 573–577 10.1038/nature03812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos H. J., Lanteri M. C., Blahnik G., Negash A., Suthar M. S., Brassil M. M. (2012). IL-1β signaling promotes CNS-intrinsic immune control of West Nile virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1003039 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinam V. A. K., Vanaja S. K., Waggoner L., Sokolovska A., Becker C., Stuart L. M. (2012). TRIF licenses caspase-11-dependent NLRP3 inflammasome activation by gram-negative bacteria. Cell 150 606–619 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray K., Marteyn B., Sansonetti P. J., Tang C. M. (2009). Life on the inside: the intracellular lifestyle of cytosolic bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7 333–340 10.1038/nrmicro2112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro J. M. C, Francischetti I. M. B. (2003). Role of arthropod saliva in blood feeding: sialome and post-sialome perspectives. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 48 73–88 10.1146/annurev.ento.48.060402.102812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossol M., Pierer M., Raulien N., Quandt D., Meusch U., Rothe K. (2012). Extracellular Ca2+ is a danger signal activating the NLRP3 inflammasome through G protein-coupled calcium sensing receptors. Nat. Commun. 3 1329 10.1038/ncomms2339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin R., Strayer D. S. (2012). Pathology: Chapter 2 Inflammation and Repair. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: USA [Google Scholar]

- Sabbah A., Chang T. H., Harnack R., Frohlich V., Tominaga K., Dube P. H. (2009). Activation of innate immune antiviral responses by Nod2. Nat. Immunol. 10 1073–1080 10.1038/ni.1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbatani L. (1899). Fermento anticoagulante de l' “Ixodes ricinus.” Arch. Ital. Biol. 31 37–53 [Google Scholar]

- Sangamnatdej S., Paesen G. C., Slovak M., Nuttall P. A. (2002). A high affinity serotonin- and histamine-binding lipocalin from tick saliva. Insect Mol. Biol. 11 79–86 10.1046/j.0962-1075.2001.00311.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sani M. M., Hajizade A., Sankian M., Fata A., Mellat M., Hassanpour K. (2013). Evaluation of the expression of the inflammasome pathway related components in Leishmania major-infected murine macrophages. Eur. J. Exp. Biol. 3 104–109 [Google Scholar]

- Sá-Nunes A., Bafica A., Antonelli L. R., Choi E. Y., Francischetti I. M. B., Andersen J. F. (2009). The immunomodulatory action of sialostatin L on dendritic cells reveals its potential to interfere with autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 182 7422–7429 10.4049/jimmunol.0900075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sá-Nunes A., Bafica A., Lucas D. A., Conrads P., Veenstra T. D., Andersen J. F. (2007). Prostaglandin E2 is a major inhibitor of dendritic cell maturation and function in Ixodes scapularis saliva. J. Immunol. 179 1497–1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder K., Tschopp J. (2010). The inflammasomes. Cell 140 821–832 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder H., Daix V., Gillet L., Renauld J.-C., Vanderplasschen A. (2007). The paralogous salivary anti-complement proteins IRAC I and IRAC II encoded by Ixodes ricinus ticks have broad and complementary inhibitory activities against the complement of different host species. Microbes Infect. 9 247–250 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.10.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuijt T. J., Coumou J., Narasimhan S., Dai J., Deponte K., Wouters D. (2011). A tick mannose-binding lectin inhibitor interferes with the vertebrate complement cascade to enhance transmission of the lyme disease agent. Cell Host Microbe 10 136–146 10.1016/j.chom.2011.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuijt T. J., Hovius J. W. R., van Burgel N. D., Ramamoorthi N., Fikrig E, van Dam A. P. (2008). The tick salivary protein Salp15 inhibits the killing of serum-sensitive Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato isolates. Infect. Immun. 76 2888–2894 10.1128/IAI.00232-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw M. H., Reimer T., Sánchez-Valdepeñas C., Warner N., Kim Y.-G., Fresno M. (2009). T cell-intrinsic role of Nod2 in promoting type 1 immunity to Toxoplasma gondii. Nat. Immunol. 10 1267–1274 10.1038/ni.1816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada K., Crother T. R., Karlin J., Dagvadorj J., Chiba N., Chen S. (2012). Oxidized mitochondrial DNA activates the NLRP3 inflammasome during apoptosis. Immunity 36 401–414 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shio M. T., Tiemi Shio M., Eisenbarth S. C., Savaria M., Vinet A. F., Bellemare M.-J. (2009). Malarial hemozoin activates the NLRP3 inflammasome through Lyn and Syk kinases. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000559 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva G. K., Gutierrez F. R. S., Guedes P. M. M., Horta C. V., Cunha L. D., Mineo T. W. P. (2010). Cutting edge: nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 1-dependent responses account for murine resistance against Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J. Immunol. 184 1148–1152 10.4049/jimmunol.0902254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soares C. A. G., Lima C. M. R., Dolan M. C., Piesman J., Beard C. B., Zeidner N. S. (2005). Capillary feeding of specific dsRNA induces silencing of the Isac gene in nymphal Ixodes scapularis ticks. Insect Mol. Biol. 14 443–452 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2005.00575.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterka D., Rati D. M., Marriott I. (2006). Functional expression of NOD2, a novel pattern recognition receptor for bacterial motifs, in primary murine astrocytes. Glia 53 322–330 10.1002/glia.20286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strowig T., Henao-Mejia J., Elinav E., Flavell R. (2012). Inflammasomes in health and disease. Nature 481 278–286 10.1038/nature10759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Styer L. M., Lim P.-Y., Louie K. L., Albright R. G., Kramer L. D., Bernard K. A. (2011). Mosquito saliva causes enhancement of West Nile virus infection in mice. J. Virol. 85 1517–1527 10.1128/JVI.01112-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukumaran B., Ogura Y., Pedra J. H. F., Kobayashi K. S., Flavell R. A., Fikrig E. (2012). Receptor interacting protein-2 contributes to host defense against Anaplasma phagocytophilum infection. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 66 211–219 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.01001.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The New York Times. (2013). Lyme Disease. Available at: http://health.nytimes.com/health/guides/disease/lyme-disease/risk-factors.html (accessed April 25, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Titus R. G., Bishop J. V., Mejia J. S. (2006). The immunomodulatory factors of arthropod saliva and the potential for these factors to serve as vaccine targets to prevent pathogen transmission. Parasite Immunol. 28 131–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titus R. G., Ribeiro J. M. (1988). Salivary gland lysates from the sand fly Lutzomyia longipalpis enhance Leishmania infectivity. Science 239 1306–1308 10.1126/science.3344436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Titus R. G., Ribeiro J. M. (1990). The role of vector saliva in transmission of arthropod-borne disease. Parasitol. Today 6 157–160 10.1016/0169-4758(90)90338-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travassos L. H., Carneiro L. A. M., Ramjeet M., Hussey S., Kim Y.-G., Magalães J. G. (2010). Nod1 and Nod2 direct autophagy by recruiting ATG16L1 to the plasma membrane at the site of bacterial entry. Nat. Immunol. 11 55–62 10.1038/ni.1823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson K., Elkins C., Patterson H., Fikrig E, de Silva A. (2007). Biochemical and functional characterization of Salp20, an Ixodes scapularis tick salivary protein that inhibits the complement pathway. Insect Mol. Biol. 16 469–479 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00742.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson K. R., Elkins C, de Silva A. M. (2008). A novel mechanism of complement inhibition unmasked by a tick salivary protein that binds to properdin. J. Immunol. 180 3964–3968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullmann A. J., Dolan M. C., Sackal C. A., Fikrig E., Piesman J., Zeidner N. S. (2013). Immunization with adenoviral-vectored tick salivary gland proteins (SALPs) in a murine model of Lyme borreliosis. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 4 160–163 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2012.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela J. G., Charlab R., Mather T. N., Ribeiro J. M. (2000). Purification, cloning, and expression of a novel salivary anticomplement protein from the tick, Ixodes scapularis. J. Biol. Chem. 275 18717–18723 10.1074/jbc.M001486200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan J. A., Scheller L. F., Wirtz R. A., Azad A. F. (1999). Infectivity of Plasmodium berghei sporozoites delivered by intravenous inoculation versus mosquito bite: implications for sporozoite vaccine trials. Infect. Immun. 67 4285–4289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vladimer G. I., Weng D., Paquette S. W. M., Vanaja S. K., Rathinam V. A. K., Aune M. H. (2012). The NLRP12 inflammasome recognizes Yersinia pestis. Immunity 37 96–107 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Nuttall P. A. (1999). Immunoglobulin-binding proteins in ticks: new target for vaccine development against a blood-feeding parasite. Cell Mol. Life. Sci. 56 286–295 10.1007/s000180050430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Nuttall P. A. (1995). Immunoglobulin-G binding proteins in the ixodid ticks, Rhipicephalus appendiculatus, Amblyomma variegatum and Ixodes hexagonus. Parasitology 111 161–165 10.1017/S0031182000064908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Paesen G. C., Nuttall P. A., Barbour A. G. (1998). Male ticks help their mates to feed. Nature 391 753–4 10.1038/35773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Manji G. A., Grenier J. M., Al-Garawi A., Merriam S., Lora J. M. (2002). PYPAF7, a novel PYRIN-containing Apaf1-like protein that regulates activation of NF-κB and caspase-1-dependent cytokine processing. J. Biol. Chem. 277 29874–29880 10.1074/jbc.M203915200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilmanski J. M., Petnicki-Ocwieja T., Kobayashi K. S. (2008). NLR proteins: integral members of innate immunity and mediators of inflammatory diseases. J. Leukoc. Biol. 83 13–30 10.1189/jlb.0607402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2013a). World Malaria Report 2011. Available at: http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/atoz/9789241564403/en/index.html (accessed April 24, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2013b). Impact of Dengue. Available at: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/dengue/impact/en/index.html (accessed April 24, 2013) [Google Scholar]