Abstract

Apolipoprotein A-II (ApoA-II) is the second most abundant protein constituent of high-density lipoprotein (HDL). The physiologic role of ApoA-II is poorly defined. ApoA-II may inhibit lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase and cholesteryl-ester-transfer protein activities, but may increase the hepatic lipase activity. ApoA-II may also inhibit the hepatic cholesteryl uptake from HDL probably through the scavenger receptor class B type I depending pathway. Interpretation of data from transgenic and knockout mice of genes involved in lipoprotein metabolism has been often complicated as clinical implications because of species difference. So it is important to obtain human ApoA-II for further studies about its functions. In our studies, Pichia pastoris expression system was first used to express a high-level secreted recombinant human ApoA-II (rhApoA-II). We have cloned the cDNA encoding human ApoA-II and achieved its high-level secreting expression with a yield of 65 mg/L of yeast culture and the purification process was effective and easy to handle. The purified rhApoA-II can be used to further study its biological activities.

Introduction

High-density lipoprotein (HDL) particles are classified according to the content of their major apolipoproteins, namely apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I) and apolipoprotein A-II (ApoA-II). ApoA-I is required to maintain the HDL structure, induces specific and nonspecific cholesterol efflux, activates lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT), and plays an antiatherogenic role.1 ApoA-II is the second most abundant protein constituent of HDL, representing 20% by weight of the HDL protein.2 The mean ApoA-II plasma concentration in normolipidemic humans is about 30–35 mg/dL.3 The human ApoA-II gene has been cloned and sequenced in several organisms.4 It is a member of the apolipoprotein multigene superfamily, which includes genes encoding soluble apolipoproteins (ApoA-I, ApoA-II, apolipoprotein C's, and apolipoprotein E).5 In pigs, humans, chimpanzees, and probably other great apes, a cysteine at residue 6 enables ApoA-II to form a homodimer.6 In healthy humans, each homodimer has a molecular weight of 17,400, consisting of two identical polypeptide chains of 77 amino acid residues.2,7

The physiologic role of ApoA-II is poorly defined and controversial. The early work by Weng and Breslow conducted in ApoA-II knockout mice showed a dramatic decrease in plasma HDL cholesterol associated with a rapid clearance of remnant particles, suggesting an important role of ApoA-II in triglyceride metabolism.8 Furthermore, the effects of ApoA-II on HDL metabolism are also complex and controversial: ApoA-II may inhibit LCAT and cholesteryl-ester-transfer protein (CETP) activities, but may increase the hepatic lipase (HL) activity. ApoA-II may also inhibit the hepatic cholesteryl uptake from HDL probably through the scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI) depending pathway. Therefore, in terms of atherogenesis, ApoA-II alters the intermediate HDL metabolism in opposing ways by increasing (LCAT, SR-BI) or decreasing (HL, CETP) the atherogenicity of lipid metabolism.9

The effect of ApoA-II on atherosclerosis has not been determined because there were conflicting clinical and epidemiological studies. Interpretation of data from transgenic and knockout mice of genes involved in lipoprotein metabolism has been often complicated as clinical implications because of species difference. Mouse ApoA-II and human ApoA-II have different molecular properties: human ApoA-II dimerizes, whereas mouse ApoA-II is a monomer and could cause different phenotypes in transgenic mice. Mouse is essentially deficient in CETP in which ApoA-II may be involved.10 Hence, it is important to obtain human ApoA-II for further studies about its functions. Although Escherichia coli-based recombinant expression system was used to express human apoA-II, the yield was somewhat low.11,12 In this study, we had cloned the cDNA encoding human ApoA-II and expressed recombinant human ApoA-II (rhApoA-II) with Pichia pastoris X-33, a wild-type Pichia strain containing the alcohol oxidase promoter, which allows for rapid growth while utilizing methanol as the sole carbon source. Eventually, we achieved high level secreting expression of rhApoA-II. Purification and preliminary characterization of rhApoA-II were also presented in this article.

Materials and Methods

Strains, Vectors, and Reagents

The P. pastoris X-33, pPICZαC vector, and zeocin antibiotic were obtained from Invitrogen and pPICZαC vector without cleavage Ste13 was reconstructed by our laboratory. All primers were synthesized by Sangon Biotechnology Corp. All restriction enzymes, DNA marker, protein marker, Pfu pyroglutamate aminopeptidase, and phosphate buffer were purchased from Takara Biotechnology. The ApoA-II antibody was obtained from Abcam Biotechnology and standard human ApoA-II was purchased from ProSpec Biotechnology. The PCR purification kit, gel extraction kit, and Miniprep kit for plasmid extraction were obtained from Sangon Biotechnology Corp.

Yeast Culture Media

P. pastoris was grown in yeast extract peptone dextrose (YPD) (2% peptone, 1% yeast extract, and 2% dextrose) or buffered minimal glycerol-complex medium (BMGY) (0.1 M potassium phosphate, 2% peptone, 1% yeast extract, 1.34% YNB, and 1% glycerol). Buffered minimal methanol-complex medium (BMMY) was used for protein induction (0.1 M potassium phosphate, 2% peptone, 1% yeast extract, 1.34% YNB, and 0.5% methanol). YPD-zeocin plates (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% dextrose, 2% agar, and 0.1 zeocin) were used for selecting positive transformants.

Acquisition the Gene of ApoA-II

Total RNA was extracted from the human liver and used as the template for reverse transcription (RT) reaction. RT reaction was carried out with the following parameters: 50°C 30 min for RT, and then 94°C 2 min to inactivate avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) reverse transcriptase. Then, the cDNA we obtained was used as the template for further PCR to amplify the DNA of human ApoA-II. The upstream primer was 5′-ATG AAG CTG CTC GCA GCA ACT GT-3′, and the downstream primer was 5′-TTA TCA CTG GGT GGC AGG CTG T-3′, the temperature of annealing was 56°C and the polymerase was Takara Ex Taq. The amplified DNA fragment (about 300 bp) was detected by electrophoresis on a 1.0% agarose gel. The resulting human ApoA-II DNA fragment was inserted into the cloning vector pMD18T and the recombinant plasmid, which contained the correct sequence of ApoA-II, was used as a template for another PCR. The primers were 5′-AAC CTC GAG AAG AGA CAG GCA AAG GAG CCA TGT-3′ (upstream primer), which contained the XhoI site and the Kex2 site, and 5′-ATT GAA TTC TCA CTG GGT GGC AGG CTG TGT TCC-3′ (downstream primer), which contained the EcoRI site. The temperature of annealing was 61°C and the polymerase was Takara Ex Taq. The amplified DNA fragment (about 230 bp) was detected by electrophoresis on a 1.0% agarose gel.

Construction of Expression Vector pPICZαC-rhApoA-II

The resulting human ApoA-II DNA fragment was digested with XhoI and EcoRI and then inserted into the corresponding sites of the expression vector pPICZαC. Then, the recombinant DNA was transformed into the competent cells of E. coli XL-Blue and the recombinant colonies were selected by zeocin (25 μg/mL) resistance. Both the nucleotide sequences of the inserted DNA and the flanking sequence were verified by sequencing with the GenomeLab DTCS-Quick Start Kit and CEQ 2000 DNA analysis system (Beckman).

Transformation of P. pastoris and Selection of High-Level Expression Colonies

Plasmid DNA was linearized with SacI and introduced into Pichia host cells P. pastoris X33 by electroporation using a Micropulser (Bio-Rad) according to the pPICZa vector manual. After the electroporation, 1 M ice-cold sorbitol was added immediately, and the cuvette contents were incubated at 30°C without shaking for 60 min. The mixture was spread on YPD agar plates containing zeocin and cultured at 30°C for 2 days. Antibiotic zeocin was used in the concentration of 0.1 g/L. After the transformants with zeocin resistance appeared, some monoclonal transformants were picked up randomly from the plates and initially cultured in a 50-mL conical tube containing 10 mL of BMGY medium at 28°C with shaking at 225 rpm for 24 h. The cloned cells were then centrifuged and resuspended in 10 mL of BMMY medium to induce expression for 7 days. The culture media (0.5 mL) were sampled each day and centrifuged at 4°C, 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The cell pellets and supernatant were separated. The supernatant was used for recombinant protein detection and the cell pellets were used for genomic DNA analysis. Methanol was added every 24 h to a final concentration of 0.5% (v/v) for inducing the expression of the target protein. The blank plasmids of pPICZαC were also transformed as a negative control.

Optimized Expression of rhApoA-II in P. pastoris

To achieve high level expression of ApoA-II, different culture parameters, including pH value and induction time were evaluated in the expression procedure. The pH values were adjusted to 3.2–6.4 with 0.4 intervals. The processes were the same as above and the pH values were adjusted every day with disodium hydrogen phosphate and citric acid. At the desired time points, 0.5-mL cell aliquots were withdrawn and then replaced with an equal amount of fresh medium. The supernatant samples were used for Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

Individual wells of the ELISA plate (Costar) were coated with 50 μL of supernatant sample of rhApoA-II diluted with 50 μL of coating buffer (15 mM Na2CO3, 35 mM NaHCO3, pH 9.6) overnight at 4°C. The plates were blocked with 5% (w/v) nonfat milk powder in PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (TPBS) and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The mouse anti-human ApoA-II monoclonal antibody (Abcam) was used at 1:1000, incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Following several washes with TPBS, the plates were incubated with goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Dingguo) (1:250 dilution with blocking buffer) for 1 h again. The color reaction was developed by addition of the substrate solution ortho-phenylenediamine and incubated for 5 min at room temperature in the dark. Then, 50 μL of stop solution (2 M H2SO4) was added to each well. The absorbance values at 490 nm were read in ELX800 Microplate Reader (Bio-Tek). The reading work was finished within 2 h after adding the stop solution.

Large-Scale Expression and Purification of rhApoA-II

The highest level expression transformant was cultured in a 5-L shake flask containing 2 L of BMGY medium at 30°C until the culture reached OD600=6.0; the cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended in 2 L of BMMY (pH 6.0) medium, and cultured at 30°C with shaking for 5 days. Sampling of the culture medium was performed every 24 h to analyze the cell wet weight, optical density, and determine rhApoA-II expression by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis, and the culture was supplemented daily with 10 mL methanol to a final concentration of 0.5% (v/v) for inducing the expression of rhApoA-II.

A cation exchange chromatographic column (20 mL, SP Sepharose XL) was equilibrated with 100 mL of 20 mM NaAc–HAc (pH 3.0) buffer. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 15,000 rpm for 10 min and was clarified with a 0.45 μm cellulose membrane. After having diluted four times with the 20 mM NaAc–HAc (pH 3.0) buffer, the pH of the fermentation broth was adjusted to 3.0 with 1 M acetate acid. The supernatant was loaded onto the cation exchange chromatographic column at the rate of 0.5 mL/min. Then, the column was washed extensively with the same buffer at the rate of 1 mL/min. The bound protein was eluted with a linear gradient of 0.1–1.0 M NaCl, while the flow rate was maintained at the rate of 1 mL/min. Protein elution was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm and identified by SDS-PAGE analysis. Column eluent containing rhApoA-II was loaded onto a reverse phase column (2.0×15 cm, Source 30), which was equilibrated with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) for further purification. RhApoA-II was eluted using 50% methanol that contained 0.1% TFA and 100% methanol (containing 0.1% TFA) at the rate of 1 mL/min and monitored by measuring the UV absorbance at 280 nm. The column effluent containing rhApoA-II was concentrated by vacuum distillation and freeze drying to remove methanol. The concise protocol of rhApoA-II is presented in Table 1. The finally purified rhApoA-II was stored at −80°C for further studies.

Table 1.

Recombinant Human Apolipoprotein Purification Protocol

| Step | Parameter | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Centrifugation | 15,000 rpm, 10 min | |

| 2 | Dilution | 4 times | 20 mM NaAc–HAc buffer |

| 3 | Adjusted pH | 3.0 | HAc |

| 4 | Cation exchange chromatography | 0.5 mL/min | To bind rhApoA-II |

| 5 | Elution | 1 mL/min | A linear gradient of NaCl |

| 6 | Collected eluted proteins | Analysis of eluted proteins | |

| 7 | Reverse phase chromatography | 0.5 mL/min | Desalination and further purification |

| 8 | Elution | 1 mL/min | Methanol |

| 9 | Collected eluted proteins | Analysis of eluted proteins | |

| 10 | Remove D methanol | Vacuum distillation and freeze drying |

Step Notes

1. Collected supernatant form fermentation broth.

2. The supernatant was diluted four times with 20 mM NaAc–HAc (pH 3.0) buffer.

3. The pH of the supernatant was adjusted to 3.0 with 1 M acetate acid.

4. The supernatant was loaded onto the cation exchange chromatographic column at the rate of 0.5 mL/min.

5. The bound protein was eluted with a linear gradient of 0.1–1.0 M NaCl, while the flow rate was maintained at the rate of 1 mL/min.

6. Protein elution was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm and SDS-PAGE analysis.

7. Column eluent containing rhApoA-II was loaded onto a reverse phase column, which was equilibrated with 0.1% TFA, for the further purification.

8. RhApoA-II was eluted using 50% and 100% methanol (containing 0.1% TFA) at the rate of 1 mL/min.

9. Protein elution was monitored by measuring the absorbance at 280 nm and SDS-PAGE analysis.

10. RhApoA-II was concentrated by vacuum distillation and freeze drying to remove methanol.

rhApoA-II, recombinant human apolipoprotein A-II; TFA, trifluoroacetic acid; SDS-PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting Assays

SDS-PAGE analysis was performed using an 18% gel. For Western blotting, proteins in the gel were transferred to the nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h and then incubated with the mouse anti-human ApoA-II monoclonal antibody (Abcam) for 12 h. After being washed, the membrane was incubated with the goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to HRP (Dingguo), diluted to 1:250. The bound antibody was detected using 3,3′-diaminobenzidine.

N-terminal Amino Acid Sequence Analysis

When glutamine (Gln) is present at the N-terminus, as in human plasma apoA-II, it can undergo cyclization to pyroglutamate. This kind of cyclization will hinder N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis. So, we need to unblock N-terminally blocked proteins before SDS-PAGE analysis or N-terminal amino acid sequence analysis. In brief, 50 mM of sodium phosphate buffer, containing 2 mU Pfu pyroglutamate aminopeptidase, 10 mM DTT, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, was mixed with 10 μg rhApoA-II at 75°C for 6 h. To determine the N-terminal sequence, the purified rhApoA-II was electrophoresed on an 18% SDS-PAGE gel and electroblotted on a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. After blotting, the PVDF membrane was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R250, and the rhApoA-II band was cut out and determined by automated Edman degradation performed on a model PPSQ-21A protein sequencer (Shimadzu).

Mass Spectrometric Analysis

Mass spectrometry was performed by use of autoflex speed MALDI-TOF/TOF MS (Brucker Daltonics). The RhApoA-II sample (5 μg) was solubilized in 10 μL 0.1% TFA. As a matrix, 10 mg/mL sinapinic acid dissolved in a solution containing 50% acetonitrile and 0.1% TFA. The sample and the matrix were mixed 1:1 before spotting on the plate and air-dried. Protein mass detection was determined using flexAnalysis 3.0 (Brucker Daltonics).

Liposomes Clearance Assay

Interactions of rhApoA-II and plasma ApoA-II with dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine (DMPC) were monitored by the method described by Cho et al.13 with slight modifications. DMPC was dispersed in tris buffered saline (TBS) (3.5 mg/mL) to form multilamellar liposomes. RhApoA-II and plasma ApoA-II were dissolved in a standard Tris buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 8.2], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2% NaN3), respectively. An aliquot of the turbid DMPC liposome solution was added to each protein solution, to give a final concentration of protein of 0.15 mg/mL. The mass ratio of DMPC to protein was 2:1 (w/w). After being mixed quickly, the solution was maintained at 24.5°C and was measured at 325 nm every 30 s.

Results

Construction and Transformation of pPICZαC-rhApoA-II

To obtain human ApoA-II gene, RT-PCR was used to get the cDNA of ApoA-II from the human liver. A specific DNA fragment about 230 bp was produced. Results of DNA sequence analysis of the recombinant expression vector pPICZαC-rhApoA-II (data not shown) demonstrated that the DNA encoding human ApoA-II was correctly inserted into the pPICZαC vector and the sequence was identical with that logged in GenBank (Accession No. NM_001643).

After being cultured at 30°C for 2 days, dozens of transformants with zeocin resistance appeared on YPD agar plates, which contained 0.1 g/L zeocin. The PCR analysis of genomic DNA showed that the DNA encoding ApoA-II was indeed integrated into over 90% of clones, which transformed with the recombinant expression vector pPICZαC-rhApoA-II. There were no similar bands for the control samples, which were transformed with the pPICZαC blank plasmid (data not shown).

Expression and Detection of rhApoA-II in P. pastoris

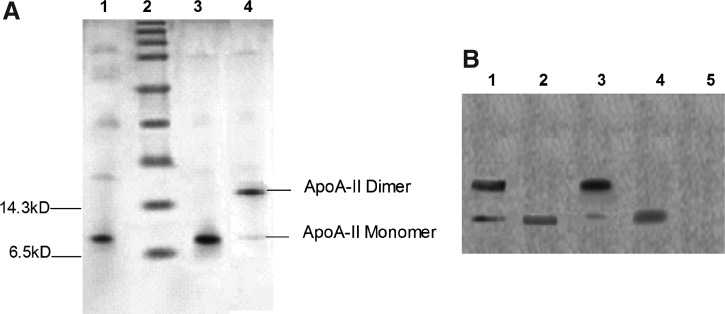

After induction with methanol for ApoA-II expression, 12 transformants showed high expression levels of rhApoA-II by ELISA and one of them was used for further experiments. SDS-PAGE analysis of the ApoA-II culture medium indicated rhApoA-II expressed after the induction of methanol, however, the rhApoA-II expression in the transformant containing blank plasmids of pPICZαC was negative. Based on the amino acid sequence, the calculated molecular weight of rhApoA-II monomer was 8.7 kDa, which was consistent with the result of SDS-PAGE measurement (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis. SDS-PAGE was performed on 18% gel and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Lane 1, protein molecular weight marker (broad). Lane 2, supernatant from the negative stain transformed with pPICZα blank plasmids. Lane 3–8, supernatant from apolipoprotein A-II (ApoA-II) culture after induction by methanol at different time points (24 h, 48 h, 72 h, 96 h, 120 h, and 144 h, respectively).

Optimized Expression of rhApoA-II in P. pastoris

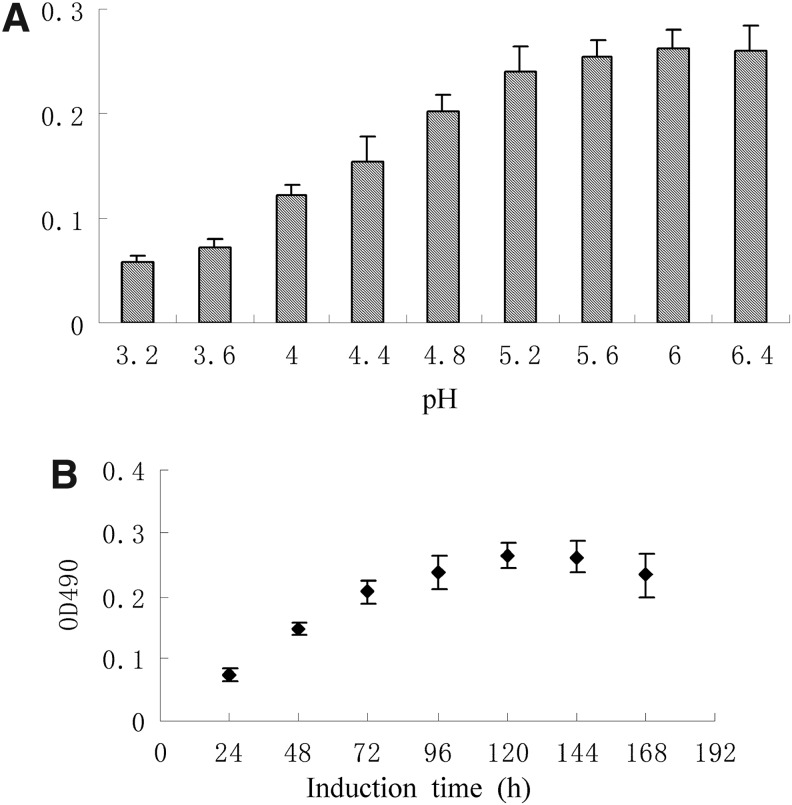

The transformant that showed the highest expression level was chosen for up scaled protein production. After a series of experiments, the optimal expression conditions of rhApoA-II were obtained as follows: the optimal pH was 6.0 (Fig. 2A) and the optimal induction time points was about the 5th day for the strain (Fig. 2B) at 28°C and methanol daily addition concentration of 0.5% (v/v). Under these conditions, high level expression transformant of P. pastoris strain was obtained and retained for further studies.

Fig. 2.

Optimized expression of recombinant human apolipoprotein (rhApoA-II) in P. pastoris. Supernatants collected at each evaluated condition were processed by ELISA. (A) Optimization of the pH value. (B) Optimization of the methanol inducing time points.

The Characterization of Purified rhApoA-II

The rhApoA-II supernatant was purified with a cation exchange chromatography and a reverse phase chromatography. Using an AKTA Explorer 100 chromatography system, we get the optimized purification parameter. The optimal concentration of NaCl for elution was 0.5 M and 100% methanol (containing 0.1% TFA) can elute the bound rhApoA-II from the reverse phase chromatographic column. Following these processes, we could get a total of 88 mg purified rhApoA-II from 2 L of culture medium, the purity of rhApoA-II about 95% as revealed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A). The protein recovery and purity of the rhApoA-II at the different purification steps were summarized and the yield of each step is shown in Table 2.

Fig. 3.

(A) SDS-PAGE analysis of rhApoA-II. Lane 1, the supernatant of rhApoA-II (reduced); Lane 2, protein molecular weight marker (broad); Lane 3, purified rhApoA-II (reduced); Lane 4, purified rhApoA-II (non-reduced). (B) Western blot analysis. Lane 1, purified and non-reduced rhApoA-II; Lane 2, purified rhApoA-II (reduced); Lane 3, standard rhApoA-II as a positive control (non-reduced); Lane 4, standard rhApoA-II as a positive control (reduced); Lane 5, supernatant of rhApoA-II before adding methanol as a negative control.

Table 2.

Recovery and Purity of rhApoA-II at Different Purification Stages from 2 L Fermentation Supernatant

| Purification steps | Total protein (mg) | RhApoA-II (mg) | Recovery (%) | Purity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supernatant | 192 | 130 | 67.7 | |

| SP Sepharose XL | 132 | 107 | 82.3 | 81.1 |

| Source™ 30RPC | 92 | 88 | 67.7 | 95.7 |

The primary purified recombinant protein was identified by Western blot analysis. The results demonstrated that the recombinant protein (both homodimer and monomer) as well as standard ApoA-II could bind with the mouse anti-human ApoA-II monoclonal antibody. No band was observed in lane 5, which was the supernatant of rhApoA-II before adding methanol (Fig. 3B).

N-terminal sequencing of rhApoA-II gave the first 13 amino acids as A K E P C V E S L V S Q Y, so compared with human ApoA-II, the N-terminal sequence of rhApoA-II was missing the first amino acid (Gln). The lack of Gln in the rhApoA-II sequence was attributed to the effect of Pfu pyroglutamate aminopeptidase, which hydrolyzes N-terminal pyroglutamate formed by cyclization of N-terminal Gln. Therefore, the N-terminal sequence of rhApoA-II was in fact identical to that of hApoA-II, confirming the successful expression and purification of rhApoA-II.

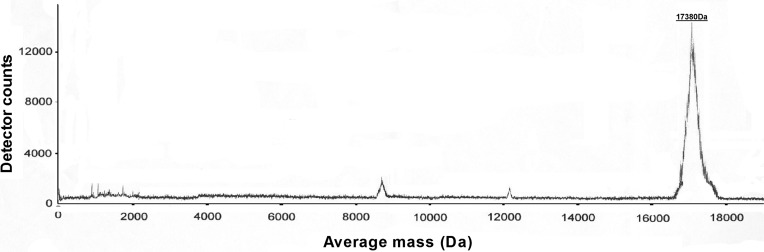

To verify the molecular weight and integrity of the recombinant protein, mass spectrometry was performed with purified rhApoA-II (Fig. 4). Human ApoA-II is a 77 amino acid protein and exists in solution primarily as a homodimer due to a disulfide linkage at Cys 6, so the expected molecular mass is 17,414 Da. However, the Gln that is present at the N-terminus of human ApoA-II can undergo cyclization to pyroglutamate with the release of NH3. Dimeric ApoA-II, containing two N-terminal Gln residues, would then be expected to lose 34 Da.11 Therefore, the experimental value of rhapoA-II is 17,380 Da, that is, in agreement with the predicted molecular mass. This indicates that our recombinant ApoA-II has the correct sequence and is highly pure. There is no obvious degradation during purification.

Fig. 4.

Mass spectrometry analysis of rhApoA-II. RhApoA-II showed a single major peak. Observed average masses resulting from the proteins are reported in Da.

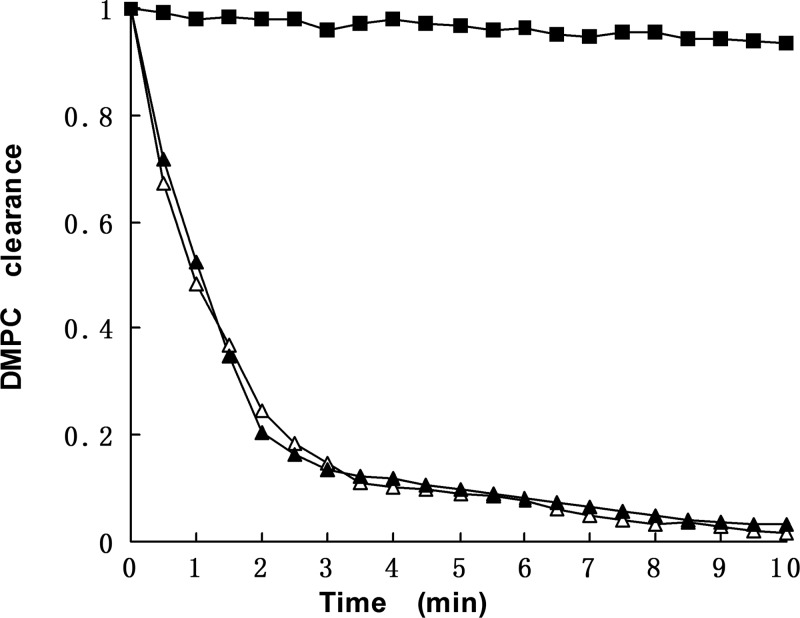

We performed DMPC clearance assays to investigate the ability of rhApoA-II to bind and reorganize multilamellar vesicles. DMPC liposomes incubated at 24.5°C without apolipoproteins were still turbid. On the other hand, both rhApoA-II and standard ApoA-II readily bind the DMPC liposomes, rendering the solution clear. No significant differences between human plasma and recombinant ApoA-II liposome clearance kinetics were observed (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Lipsomes clearance assay of rhApoA-II and plasma ApoA-II. Closed rectangles: dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine (DMPC) liposomes only; Open triangles: rhApoA-II; Closed triangles: human plasma ApoA-II (standard ApoA-II).

Conclusion

ApoA-II is the second most abundant protein constituent of HDL, however, its role in HDL metabolism is still unclear. Despite a few studies that showed ApoA-II decreased atherosclerosis susceptibility,14 many studies drew a conclusion that overexpression of ApoA-II was proatherogenic.15,16 Whereas these findings are important from the viewpoint of mouse pathology, they may not necessarily apply to humans given the important differences in lipoprotein metabolism between these two species.17 In our studies, P. pastoris expression system was first used to express a high level secreted rhApoA-II. We have cloned the cDNA encoding human ApoA-II and achieved its high level secreting expression with a yield of 65 mg/L of yeast culture.

In recent years, a purification tag has been commonly attached to recombinant proteins to allow rapid and complete purification. In general, affinity tags allow binding to affinity purification ligands without affecting the normal function of the protein of interest. Amino-terminal affinity tags may be removed by specific proteolytic cleavage, but it can be difficult to release affinity tags from some fusion proteins. Because little is known about human ApoA-II, we wanted to obtain native ApoA-II without the use of affinity tags to avoid potential impact on its structure and function. The purification process we designed is effective and easy to carry out. The purified rhApoA-II has identical properties to human plasma ApoA-II and can therefore be used in further studies.

Abbreviations

- ApoA-I

apolipoprotein A-I

- ApoA-II

apolipoprotein A-II

- CETP

cholesteryl-ester-transfer protein

- DMPC

dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- Gln

glutamine

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HL

hepatic lipase

- LCAT

lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase

- PVDF

polyvinylidene fluoride

- rhApo A-II

recombinant human apolipoprotein A-II

- RT

reverse transcription

- SR-BI

scavenger receptor class B type I

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- YPD

yeast extract peptone dextrose

Acknowledgments

This work was kindly supported by the Jilin Science and Technology Bureau (20120957), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 81272875), Jilin Province Development and Reform Commission, Jilin University (Grants 200903339), and the Foundation for Distinguished Young Talents in Higher Education of Guangdong, China (LYM11080).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Escolà-Gil JC. Julve J. Marzal-Casacuberta A. Ordóñez-Llanos J. González-Sastre F. Blanco-Vaca F. Expression of human apolipoprotein A-II in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice induces features of familial combined hyperlipidemia. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:1328–1338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scanu AM. Edelstein C. Gordon JI. Apolipoproteins of human plasma high density lipoproteins. Biology, biochemistry and clinical significance. Clin Physiol Biochem. 1984;2:111–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bu X. Warden CH. Xia YR, et al. Linkage analysis of the genetic determinants of high density lipoprotein concentrations and composition: evidence for involvement of the apolipoprotein A-II and cholesteryl ester transfer protein loci. Hum Genet. 1994;93:639–648. doi: 10.1007/BF00201563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li WH. Tanimura M. Luo CC. Datta S. Chan L. The apolipoprotein multigene family: biosynthesis, structure function relationship, and evolution. J Lipid Res. 1988;29:245–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blanco-Vaca F. Escolà-Gil JC. Martín-Campos JM. Julve J. Role of apoA-II in lipid metabolism and therosclerosis: advances in the study of an enigmatic protein. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:1727–1739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puppione DL. Whitelegge JP. Yam LM. Bassilian S. Schumaker VN. MacDonald MH. Mass spectral analysis of domestic and wild equine apoA-I and A-II: detection of unique dimeric forms of apoA-II. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;142:369–373. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpb.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brewer HB., Jr. Lux SE. Ronan R. John KM. Amino acid sequence of human apolp-gln-II (apoA-II), an apolipoprotein isolated from the high-density lipoprotein complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:1304–1308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.5.1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weng W. Breslow JL. Dramatically decreased high density lipoprotein cholesterol, increased remnant clearance, and insulin hypersensitivity in apolipoprotein A-II knockout mice suggest a complex role for apolipoprotein A-II in atherosclerosis susceptibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14788–14794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tailleux A. Duriez P. Fruchart JC. Clavey V. Apolipoprotein A-II, HDL metabolism and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2002;164:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00751-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shimano H. ApoAII controversy still in rabbit? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1984–1985. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.196683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith LE. Yang J. Goodman L, et al. High yield expression and purification of recombinant human apolipoprotein A-II in Escherichia coli. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:1708–1715. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D028043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopez J. Latta M. Collet X, et al. Purification and characterization of recombinant human apolipoprotein A-II expressed in Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1994;225:1141–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.1141b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho KH. Durbin DM. Jonas A. Role of individual amino acids of apolipoprotein A-I in the activation of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase and in HDL rearrangements. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:379–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tailleux A. Bouly M. Luc G, et al. Decreased susceptibility to diet-induced atherosclerosis in human apolipoprotein A-II transgenic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:2453–2458. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.11.2453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warden CH. Hedrick CC. Qiao JH. Castellani LW. Lusis AJ. Atherosclerosis in transgenic mice overexpressing apolipoprotein A-II. Science. 1993;261:469–471. doi: 10.1126/science.8332912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Escolà-Gil JC. Julve J. Marzal-Casacuberta A. Ordóñez-Llanos J. González-Sastre F. Blanco-Vaca F. ApoA-II expression in CETP transgenic mice increases VLDL production and impairs VLDL clearance. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scanu AM. Edelstein C. HDL: bridging past and present with a look at the future. FASEB J. 2008;22:4044–4054. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-117150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]