Abstract

Background

Doctors are more likely to implement guidelines in their everyday practice if the recommendations contained in them are understandable. So far, there has been little standardization in the wording of guideline recommendations. It would be important to know how certain terms are understood by guideline users. In this study, doctors were asked in a survey about what they considered to be the level of obligation carried by various formulations that are commonly used in guidelines to recommend particular courses of action.

Methods

An online survey of physicians (mostly dermatologists) was carried out in which they were asked to rate, on a visual analog scale, what they perceived to be the level of obligation of various common formulations for guideline recommendations.

Results

The terms “muss” (must) and “darf nicht” (must not) were interpreted as being maximally binding. The two closely related German words “soll” (shall) and “sollte” (should) were considered highly binding, as were negative formulations such as “wird nicht empfohlen” (is not recommended). The perceived level of obligation of “soll” did not differ from that of “sollte” to any detectable extent, nor was there any detectable distinction between the various negative formulations studied. Formulations with the words “wird empfohlen” (is recommended), “kann empfohlen werden” (can be recommended), or other “kann” (can) expressions were considered to be only mildly or moderately binding. In general, there was marked variation in the perceived level of obligation of formulations located in the low and middle ranges.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that guideline users do not necessarily perceive recommendation strengths as the guideline authors intended. It might be better if positive recommendations came in only two different strengths, while a single recommendation strength might suffice for negative ones. Further studies should shed more light on this question.

Medical guidelines are systematically developed aids to making decisions about the appropriate course of action in cases of particular health problems (1). In addition to improving health care for the population, the purpose of guidelines is to help avoid unnecessary interventions and costs. Thus, guidelines are instruments by which discrepancies between medical actions and scientific knowledge can be reduced.

So far, there has been little standardization in the wording of guideline recommendations in the German-speaking countries.

The Methods Report for the National Disease Management Guideline (NVL, Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinien) program, produced by the German Medical Association (BÄK, Bundesärztekammer), the National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians (KBV, Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung), and the Association of Scientific Medical Societies in Germany (AWMF, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen medizinischen Fachgesellschaften), distinguishes three different strengths of recommendation. In addition, it is intended that recommendations should be clear, unambiguous, action-oriented, and worded in a way that is as easy to understand as possible; and that the strength of recommendations is reflected in the choice of modal verb used (2). Accordingly, the NVL uniformly uses the words “soll” (shall), “sollte” (should), and “kann” (can). Although the AWMF’s guidelines for guidelines (AWMF Regelwerk) as the most important guide to guideline development in Germany—recommends the use of three recommendation strengths, with suggestions for the wording for each (3), many guidelines issued by the medical societies often contain a multitude of different wordings side by side.

For the German speaking countries, there have so far been no studies investigating how these different wordings are interpreted by the users of the guidelines. An accurate understanding of the perceived level of obligation carried by frequently used wordings in guideline recommendations—that is, how binding the wordings are felt to be—would be helpful to all those who develop, use, and evaluate guidelines.

For the Anglophone countries, Lomotan et al., in 2010, were the first to study perceptions of wordings used in guideline recommendations (4). This study showed that, for many wordings, the perceived level of obligation varied considerably, and that overlaps existed between wordings in terms of how binding they were.

The aim of the present study was to record the perceived level of obligation conveyed by formulations often encountered in guideline texts, in order to draw from them some standard terms for the wording of recommendations in German.

Methods

As part of a project supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft), in collaboration with the Centre for General Linguistics (Zentrum für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft) in Berlin, we investigated the perceived level of obligation conveyed by formulations used in German guidelines. To this end, following the procedure used by Lomotan et al. (4), our chosen method was to conduct an online survey administered to physicians.

To develop the questionnaire, as a first step, recommendation formulations were identified from 28 S2k (formal consensus-based guidelines) and S3 guidelines (evidence-based and formal consensus–based) selected at random from the AMWF register. The formulations of the eight S2k guidelines and 20 S3 guidelines were divided into “directive” and “discretionary” recommendations. Using the directive and discretionary formulations identified, 13 sentences were formulated (e.g., “Medikament X wird zur Behandlung von Krankheit Y empfohlen.” [Substance X is recommended for the treatment of disease Y] [Box]). These were supplemented by another 13 formulations designed as “filler questions” to distract respondents’ attention away from the survey’s true focus of interest and reduce the risk of biased answers (e.g., “Der Zustand X ist in der Regel keine Indikation zur Handlung Y.” [Condition X is usually not an indication for action Y]) (5).

Box. Investigated wordings of guideline recommendations.

-

Directive recommendations

-

If condition X is present,

then action Y must be done (muss erfolgen).

-

If condition X is present,

then action Y shall be done (soll erfolgen).

-

If condition X is present,

then action Y should be done (sollte erfolgen).

-

If condition X exists,

then action Y can be done (kann erfolgen).

-

If condition X is present,

then action Y shall not be done (soll nicht erfolgen).

-

If condition X is present

then action Y should not be done (sollte nicht erfolgen).

Substance X must not be used (darf nicht angewendet werden) to treat disease Y

-

-

Discretionary recommendations

Substance X is recommended (wird empfohlen) for treatment of disease Y.

Substance X can be recommended (kann empfohlen werden) for treatment of disease Y.

Substance X can be considered (kann erwogen werden) for treatment of disease Y.

Substance X cannot yet be conclusively assessed (kann noch nicht abschließend beurteilt werden) for treatment of disease Y.

Substance X cannot be recommended (kann nicht empfohlen werden) for treatment of disease Y.

Substance X is not recommended (wird nicht empfohlen) for treatment of disease Y

The formulations were listed in a questionnaire in random order. Respondents were asked to use a visual analog scale (VAS) to rate each formulation for its implied (as they saw it) level of obligation to carry out an action. The VAS coding went from 0 (no obligation) to 100 (maximum obligation). In addition to the VAS questionnaire, information on sex and age, medical specialization, professional qualification, whether working in a private practice or a hospital, and place of residence (federal state) was recorded.

Physicians from the specialties of dermatology, psychiatry, and general medicine were informed about the online survey and invited to take part by the newsletters of their respective medical societies. The online survey was set up using the open source software at Limesurvey.org, and was carried out from 22 February to 8 May 2012.

Descriptive statistical analysis was carried out using SAS version 9.3 and IBM SPSS Statistics 19. A graphic representation of the VAS values was produced using box plots. Subgroup analyses were carried out for sociodemographic data. The answers to the “filler questions” were not included in the analysis.

Results

A total of 447 physicians took part in the survey. Of these, 375 (90.4%) were in dermatology, 15 (3.6%) in general medicine, 14 (3.4%) in psychiatry, and 11 (2.6%) in other specialties (Table 1). The response rate cannot be calculated, because the exact number of invitations sent out by email, as well as the proportion of email addresses that were out of date, is unknown.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of respondents (N = 415).

| Mean (± SD) | Range | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)* | 47.3 (±10.2) |

26–75 | |

| n | % | ||

| Sex |

|

242 173 |

58.3 41.7 |

| Medical specialty |

|

375 15 14 11 |

90.4 3.6 3.4 2.6 |

| Place of work |

|

254 135 26 |

61.2 32.5 6.3 |

| Professional qualification |

|

254 71 30 24 36 |

61.2 17.1 7.2 5.8 8.7 |

| Geographical location* |

|

54 61 35 10 2 17 27 3 22 86 22 4 15 9 31 8 |

13.0 14.7 8.4 2.4 0.5 4.1 6.5 0.7 5.3 20.7 5.3 1.0 3.6 2.2 7.5 1.9 |

|

4 3 1 |

1.0 0.7 0.2 |

*One answer missing SD, standard deviation; MDK, Medizinischer Dienst der Krankenversicherung (Medical Service of the Health Insurance Companies in Germany)

The VAS questions were answered in full by 415 respondents, and these datasets are the basis of the present analysis. The demographic data are summarized in Table 1.

The levels of obligation implied by the 13 formulations under investigation are presented in Table 2, in descending order of the median and sorted into positive and negative formulations. The formulations “darf nicht” (must not) and “muss” (must) show very high levels of obligation (for both: median score 100 on the VAS of 0–100), with a small variability between the answers for these formulations (interquartile range, IQR = 2 for “darf nicht”, IQR = 3 for “muss”). For the formulations “soll” (shall), “soll nicht” (shall not), “sollte” (should), “sollte nicht” (should not), “wird nicht empfohlen” (is not recommended), and “kann nicht empfohlen werden” (cannot be recommended), median VAS values of 75 to 85 with IQRs between 24 and 29 were calculated. An intermediate level of obligation was achieved by the formulations “wird empfohlen” (is recommended) and “kann empfohlen werden” (can be recommended) (VAS values [median] 59 and 50, respectively). However, the IQRs indicate a high variability of the perceived levels of obligation among respondents (IQR = 33 and 42, respectively). Low levels of obligation were recorded for “kann” (can) formulations (VAS values [median] between 12 and 31). Here, too, the variability in the answers was high (IQR between 36 and 42). The formulation “kann noch nicht abschließend beurteilt werden” (cannot yet be conclusively assessed) was awarded the lowest perceived level of obligation.

Table 2. Perceived level of obligation conveyed by guideline recommendations (N = 415).

| Formulation | Visual analog scale [0–100] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 25th percentile | 75th percentile | |

| Positive | |||

| muss (must) | 100 | 97 | 100 |

| sollte (should) | 78 | 59 | 88 |

| soll (shall) | 75 | 59 | 86 |

| wird empfohlen (is recommended) | 59 | 44 | 77 |

| kann empfohlen werden (can be recommended) | 50 | 28 | 70 |

| kann erfolgen (can be done) | 31 | 14 | 50 |

| kann erwogen werden (can be considered) | 23 | 9 | 46 |

| kann noch nicht abschließend ‧beurteilt werden (cannot yet be conclusively assessed) | 12 | 0 | 42 |

| Negative | |||

| darf nicht (must not) | 100 | 98 | 100 |

| soll nicht (shall not) | 85 | 72 | 98 |

| sollte nicht (should not) | 83 | 71 | 95 |

| wird nicht empfohlen (is not recommended) | 81 | 63 | 90 |

| kann nicht empfohlen werden (cannot be recommended) | 80 | 62 | 91 |

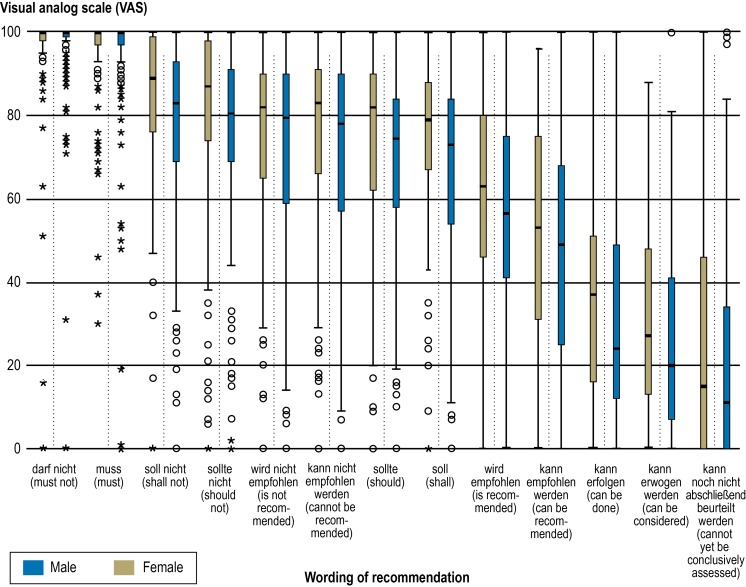

Analysis according to sex showed that, with the exception of “muss” (must) and “darf nicht” (must not), the VAS medians among the men were on average 5 points lower than the values among the women. The largest difference between men and women was for “kann erfolgen” (can be done) (13 points) and the smallest for “wird nicht empfohlen” (is not recommended) (2.5 points) (Figure).

Figure.

Box plot: perceived level of obligation (VAS values: 0–100) conveyed by guideline recommendations, according to sex of respondent

° = outlier (value that is 1.5 to 3 times the interquartile range from the median)

* = extreme (value that is more than 3 times the interquartile range from the median)

VAS = perceived level of obligation conveyed by recommendation wording as estimated on a visual analog scale

There was no identifiable tendency to perceive the level of obligation as stronger or weaker depending on age. The correlation coefficient (Spearman) ranged between –1.13 and 0.15, depending on formulation (data not shown).

Discussion

The success of a clinical guideline hangs to a great extent on how widely it is distributed and implemented. Implementation is the transfer of recommendations for action to individual physician action or behavior (6). Quality criteria exist for this, which require among other things that recommendations should be reliable and reproducible, and that use of the guideline should lead to the desired care outcomes (1). In this connection, it is important that the wording of guideline recommendations is understood in the same way by all users.

In NVL, to reflect the differences between three different strengths of recommendation in words, the three terms “soll” (shall), “sollte” (should), and “kann” (can) are used; these are also the terms recommended by the AWMF. However, the present study shows that there is no difference between the perceived levels of obligation of the terms “soll” (shall) and “sollte” (should); that is, that, contrary to the intentions of the guideline developers, both these terms are equally understood as entailing a high level of obligation. In contrast to this, the term “kann” (can) is interpreted as conveying a lower level of obligation than “soll” and “sollte.” Formulations involving “kann” have a high variability of perceived level of obligation among users, and so are interpreted very differently by different individuals. The perceived level of obligation of “kann” formulations, however, depends on the verbs that follow them. For example, “kann noch nicht abschließend beurteilt werden” (cannot yet be conclusively assessed) is perceived as having a very low level of obligation, whereas “kann empfohlen werden” (can be recommended is perceived, like “wird empfohlen” (is recommended), as having an intermediate level of obligation. It should be noted that the formulation “kann noch nicht abschließend beurteilt werden” is more a statement than a recommendation for action, and is thus only to a limited extent a decision-making aid for the user.

The perceived level of obligation of “soll” and “sollte” is strongly influenced by the verbs that follow. “soll durchgeführt werden” (Shall be performed) has a quite different level of obligation to “soll angeboten werden” (shall be offered) or “soll erwogen werden” (shall be considered). Because of this, standardization of the combined verbs should also be aimed at, because otherwise almost every recommendation containing “soll” (shall) can be turned by a weak second verb into a weak recommendation, resulting in a low level of obligation and unclear guidance for the guidelines’ users.

Formulations involving “muss” (must) and “darf nicht” (must not) are all notable for a high perceived level of obligation to perform or not to perform an action. Guidelines, however, are not rules, but are intended as “aids to navigation” in the sense of indicating “corridors for action and decision” which may—or even must be—deviated from in certain properly justified cases (1). For this reason, directive formulations (“muss” and “darf nicht”) should not normally be used in guideline recommendations.

The legal interpretation of verbal formulations should be taken into account. In formulating regulations in administrative law, legislators use the word “muss” (must) to lay down a strict course of administrative action, whereas the word “kann” (can) often allows a certain room for discretion according to which one of several actions, each of them fundamentally lawful, may take place. A reduction of the scope for discretion is expressed by “soll” (shall) according to which, as a rule, a sequence of lawful steps is determined that may be abstained from only in exceptional, atypical cases (7– 11).

To promote a uniform understanding of guideline recommendations, it is desirable to derive some standard formulations. The advantage of standard formulations for recommendations is that guideline authors know how their recommendations will be understood by the users of the guideline. In this way, errors of communication between the authors and the users of the guideline can be reduced. The use of standard formulations leads to greater user-friendliness, if formulations are established and are always used to mean the same thing. In addition, standard formulations can support the process of developing recommendations in consensus processes. Long-drawn-out discussions about wording will be avoided if recourse can be had to terms that have been studied and recommended. Wordings particularly well suited to standard formulations are those that convey clearly distinguishable levels of perceived obligation, in order to express different strengths of recommendation, and which show a low variability in their interpretation.

For the Anglophone world, Lomotan et al. (4) suggest the words “must,” “should,” and “may” as suitable formulations, in order to distinguish between three different strengths of recommendation. Of these, “must” conveys the highest level of obligation (VAS value [median] = 100) and is unequivocally comparable with the perceived levels of obligation found in the present study for “muss” (must) and “darf nicht” (must not). Lomotan et al. also indicate that the use of “must” should be restricted. According to Lomotan et al. (4), a low level of obligation follows “may” (VAS value [median] = 37). In contrast to this, terms such as “should” or “is recommended” are understood as carrying an intermediate level of obligation, although the VAS median values in this category varied between 50 and 75 on a scale of 0–100. The German recommendation formulations cannot be straightforwardly translated into these categories. Although the wordings “soll/te” (shall/should), “soll/te nicht” (shall not/should not), “wird nicht empfohlen” (is not recommended), and “kann nicht empfohlen werden” (cannot be recommended) are interpreted uniformly in terms of strength of recommendation and variability in level of obligation, recommendations using these wordings are perceived as more strongly binding than those in English using “should.” On the other hand, formulations in German using “kann” (can) show a low to intermediate perceived level of obligation, although the VAS scoring varies strongly between respondents.

The results of the present study do not yet allow the final derivation of standardized wordings for guideline recommendations. When starting work, every guideline group should lay down three categories of recommendation (open, simple, strong), or just two categories (strong, weak), as for instance in the GRADE system (12). Appropriate wordings for the formulations should then be chosen, depending on their suitability for the guideline in question, building on the results presented during the guideline development.

An interesting point is that formulations of recommendations not to perform an action are perceived as more binding than corresponding recommendations to perform an action. Thus, the negative formulations “wird nicht empfohlen” (is not recommended) and “kann nicht empfohlen werden” (cannot be recommended) are perceived as more binding than the corresponding formulations without the “nicht” (not). Presumably, formulations that advise against an action lead to an implication of harm if the action is carried out, and thus invoke the medical precept: “First, do no harm.” In general, according to the present study, recommendation formulations using “nicht” are understood as more binding, irrespective of whether the “nicht” is linked to “soll”, or “sollte,” or “kann.” For this reason, we would advise guideline groups to use only a single strength of negative recommendation.

The results of the present study indicate that men generally perceive recommendations as less binding than women do. However, we do not infer a need for gender-specific guidelines on the basis of this study. The differences depending on sex related to almost all formulations, but some of them were only small. The male respondents in the survey were on average 5 years older than the female respondents, so age bias is possible—although no such tendency was identified in the subanalysis according to age.

A notable finding is that 90.4% of the survey respondents were dermatologists, only 3.6% general physicians, 3.4% psychiatrists, and only 2.6% came from other specialties. The differences are due to the differences in how prominently the invitation to participate was displayed in the respective newsletters. Since we, the authors, are in dermatology, we were able to gain support by sending out single emails containing individual invitations, so that there was a particularly high awareness of the survey among dermatologists. In the other branches of medicine, the invitation to participate was sent out with a host of other messages. It may be assumed, however, that the perceived level of obligation of the guideline formulations under investigation is assessed similarly by all physicians, and that the assessment (VAS score) does not depend on physicians’ specializations.

It is possible that recommendation formulations are perceived differently depending on levels of professional qualification (e.g., a respondent’s level of training). Because participants were recruited via the email distribution lists of the medical societies, the proportion of specialists in the survey was particularly high, and it may be that the results do not take enough account of more junior doctors. The high proportions of both dermatologists and of specialists must be taken into account as possible sources of selection bias. However, it is hard to estimate a specific influence on the basis of the existing data.

In general, a notable feature in the data analysis was the recurrent appearance of extremes, as for example the assessment of “darf nicht” (must not) as not at all binding. It must be assumed that the respondents misunderstood the question here; perhaps they confused “perceived level of obligation” with “probability that you would carry out this action.”

Summary

The present study provides the first data about how the formulations of German-language guideline recommendations are understood in terms of the level of obligation they are perceived to entail. The results do not yet allow a final set of formulations for varying strengths of recommendations to be derived. Further studies are needed to answer the question of whether adding symbols (e.g., arrows) to support the formulations will help guideline users to interpret recommendations in a more uniform way.

Key Messages.

The wording of guideline recommendations is not very well standardized.

The terms “soll” (shall) and “sollte” (should)—although intended by guideline authors to express different strengths of recommendation—are both understood as expressing a high level of obligation.

Formulations such as “wird empfohlen” (is recommended and “kann empfohlen werden” (can be recommended) are very differently interpreted in terms of the level of obligation they express.

Recommendation obligations containing “nicht” (not) are generally understood as strongly binding (high level of obligation); a single recommendation strength could be enough for use in negative recommendations.

Since respondents were unable to distinguish consistently between most of the positive formulations investigated, it might make more sense to use only two positive standard formulations

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Kersti Wagstaff, MA.

We are grateful to all who took part in the study, and to the following medical societies who supported it by sending out the invitations to take part: the German Society of Dermatology (DDG, Deutsche Dermatologische Gesellschaft), German Association for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics (DGPPN, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde), German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Allgemeinmedizin und Familienmedizin). We are also grateful to ass. iur. Markus Schlaab for legal advice.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Bloch RE, Lauterbach K, Oesingmann U, Rienhoff O, Schirmer HD, Schwartz FW. Bekanntmachungen: Beurteilungskriterien für Leitlinien in der medizinischen Versorgung. Beschlüsse der Vorstände von Bundesärztekammer und Kassenärztlicher Bundesvereinigung Juni 1997. Dtsch Arztebl. 1997;94(33):A2154–A-2155. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bundesärztekammer (BÄK) Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung (KBV), Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF) Programm für Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinien. Methoden-Report. www.versorgungsleitlinien.de/methodik/reports. 4th edition. 2010. Last accessed on 14 January 2013.

- 3.Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (AWMF)-Ständige Kommission Leitlinien. AWMF-Regelwerk “Leitlinien”. www.awmf.org/leitlinien/awmf-regelwerk.html. 1st edition 2012. Last accessed on 14 January 2013.

- 4.Lomotan EA, Michel G, Lin Z, Shiffman RN. How “should” we write guideline recommendations? Interpretation of deontic terminology in clinical practice guidelines: survey of the health services community. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19:509–513. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2009.032565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowart W. Experimental syntax: applying objective methods to sentence judgments. SAGE Publications Inc. 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muche-Borowski C, Kopp I. Wie eine Leitlinie entsteht. Z Herz-Thorax-Gefäßchir. 2011;25:217–223. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koch HJ, Rubel R, Heselhaus S. München: Luchterhand (Hermann); 2003. Allgemeines Verwaltungsrecht. § 5 Rn. 83. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koch HJ, Rubel R, Heselhaus S. München: Luchterhand (Hermann); 2003. Allgemeines Verwaltungsrecht. § 5 Rn. 84. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maurer H. München: Beck Juristischer Verlag; 2008. Allgemeines Verwaltungsrecht. § 7 Rn. 9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maurer H. München: Beck Juristischer Verlag; 2008. Allgemeines Verwaltungsrecht. § 7 Rn. 12, 17. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suckow H, Weidemann H. Grundriss für die Aus- und Fortbildung. Rn. 256. Stuttgart: Deutscher Gemeindeverlag; 2007. Allgemeines Verwaltungsrecht und Verwaltungsrechtschutz. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]