Abstract

We present here a novel platform combination, using a multifunctional pipette to individually electroporate single-cells and to locally deliver an analyte, while in their culture environment. We demonstrate a method to fabricate low-resistance metallic electrodes into a PDMS pipette, followed by characterization of its effectiveness, benefits and limits in comparison with an external carbon microelectrode.

Cellular heterogeneity has been identified as one limiting factor in further understanding how biological cells function within tissues.1 In vitro analysis of cells has shown that individual entities can display considerable variability, particularly stem cells, but primary cells and permanent cell lines display similar behaviour. Treating these populations as an ensemble average infers an unnatural homogeneity to the cellular functions. Individual events occurring infrequently are hidden due to this averaging effect.2 The benefits of single cell analysis are driving new investigations, from both biochemical3–5 and analytical perspectives.6,7

In order to manipulate and analyze the cellular machinery, access to its content is often required. Electroporation has proven to be a useful technique for this, allowing controllable and reversible permeabilization of the cell membrane, by application of an electric field.8,9 Nano-scale membrane pores, which are created in the process, allow transport of a variety of substances from small molecules to DNA and RNA across the membrane.10 As the effects of electroporation on the membrane can be achieved reversibly, the cells maintain their functions and remain viable. This allows, for example, investigation of gene expression and RNA interference.11 Methods for the targeted electroporation of single-cells have also emerged,12 utilizing microfluidic technology,13–15 glass capillaries16,17 or micro electrodes.18,19

In this communication, we present a novel approach for single cell electroporation in combination with highly localized solution delivery, utilising the multifunctional microfluidic pipette.20,21 We demonstrated this approach using two electrode configurations; carbon fiber electrodes being externally (with respect to the device) arranged to apply the electroporation field, and fabrication of an electroporation electrode into the pipette. The second strategy has the distinct advantage of enabling solution delivery and targeted field deployment on one device, therefore avoiding the need to position two separate probes (fluidic and electroporation electrode) near the cell.

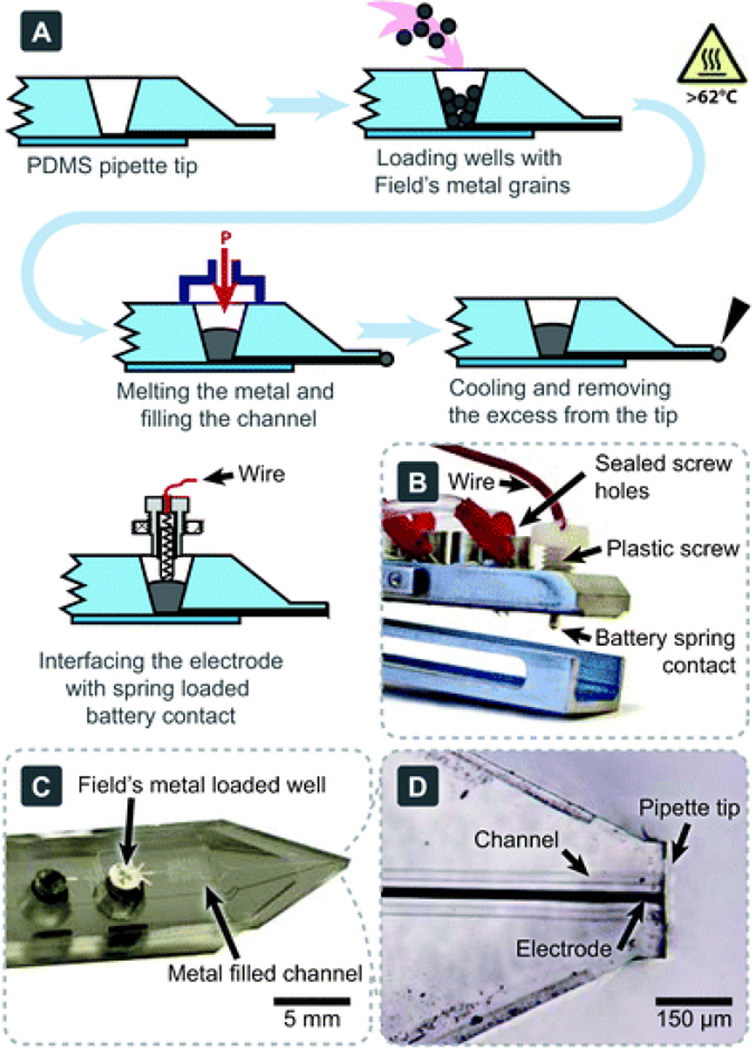

We have previously demonstrated the utility of the multifunctional pipette for localized solution delivery and switching.21 Here we demonstrate the combination of this device with both on-chip and external electroporation electrodes, suitable for single-cell studies. A schematic of the procedure for the integrated electrode fabrication is shown in Fig. 1, with a detailed description given in the electronic supplementary information (ESI)†. A photograph of the connecting interface is shown in Fig. 1B, and the final fabricated electrode can be seen in Fig. 1C,D.

Fig. 1.

Integrating electrodes into the multifunctional pipette. (A) A depiction of the fabrication procedure for Field's metal electrodes, using a common laboratory hotplate. The electrodes were electroplated with gold before use; this step is not shown. (B) A photograph of the pipette holder and electrical interface to the internal electrode. (C) Macro-and (D) micro-photographs of a pipette tip, highlighting the integrated electrode.

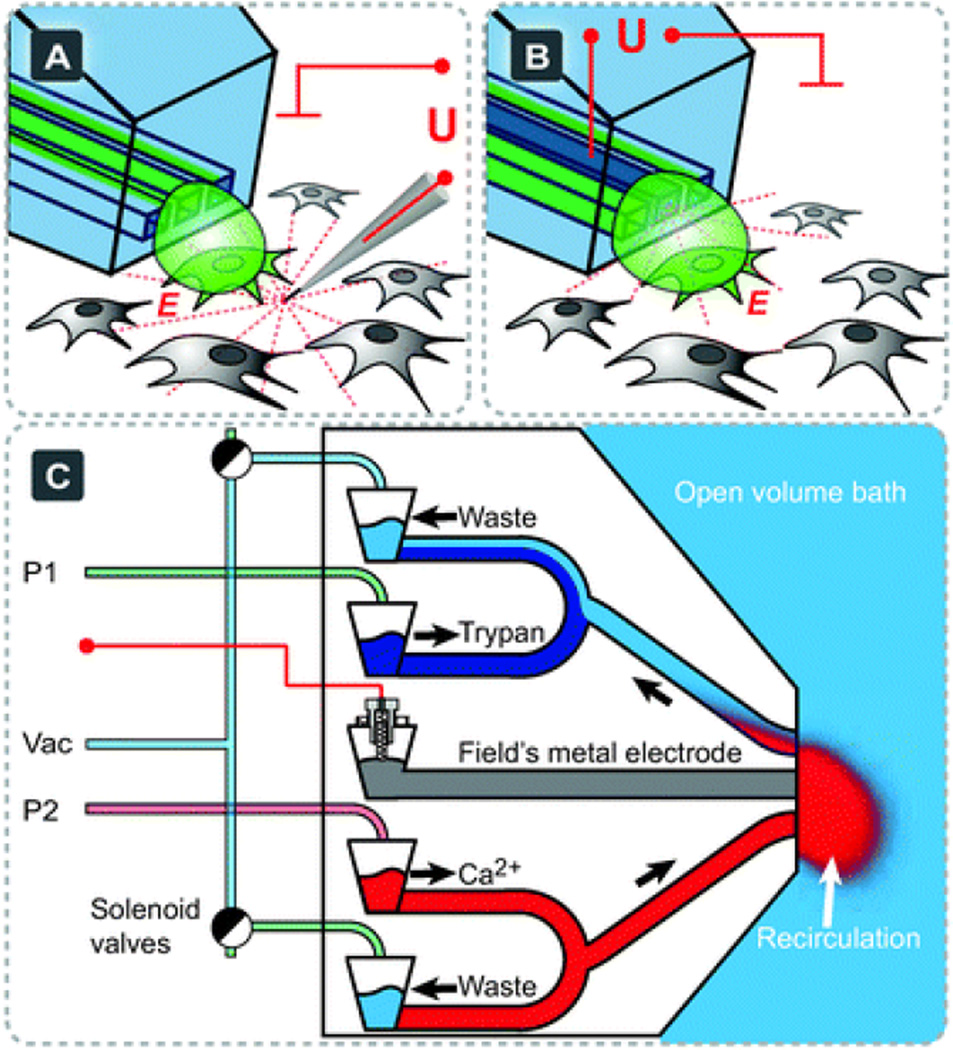

In a first experimental set, we used the pipette to generate a localized chemical environment (fluorescein solution) around a cell and used a carbon fiber electrode for electroporation (Fig. 2A). This poration scheme takes advantage of the tilted pipette configuration, which provides access to the recirculation zone for external probes. Microfluidic probes featuring a planar apex that covered the surface22,23 would not allow for such an arrangement. In a second experimental set we extended the electroporation concept by integrating an electrode into the pipette (Fig. 2B). This not only eliminates the need for two micromanipulators, but most of all simplifies operation, as only one probe needs to be positioned. The risk of damaging the rather fragile carbon fiber microelectrode is also eradicated.

Fig. 2.

Pipette configurations. (A) A combination of the multifunctional pipette with an external carbon fiber electrode for single cell electroporation and simultaneous localized solution delivery. The red dotted lines represent the electric field (simplified). (B) The multifunctional pipette with integrated electroporation electrode in the same experimental environment. The counter electrode for both configurations is located in the open bath, represented by a red ground symbol. (C) A schematic representation of a two-channel superfusion pipette, allowing multiplexing between two chemical environments: Ca2+ for chemical stimulation and Trypan blue for a subsequent viability test. External supply connections and solution well structures are also depicted, but are not to scale.

Fabrication of the pipette itself is achieved by soft-lithography in polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS).24 However, integrating electrodes into a PDMS structure is challenging due to the poor adhesion of metals to PDMS, hindering standard photolithographic patterning and vapor deposition of the metal tracks. Previously reported approaches to fabricate electrodes into a PDMS device include rather elaborate procedures: gold implantation from a filtered cathode voltage arc, creating a 50 nm conductive layer (σ ≈ 2 × 105 S m−1),25 mixtures of silver particles and PDMS (AgPDMS, σ≈2 × 104 S m−1) filled into 40 µm × 100 µm channels,26 mixtures of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and PDMS (σ≈67 S m−1), filled into 200 µm × 170 µm channels.27 Additionally, injection of molten metals and alloys has been used to fabricate electrodes, for example liquid gallium (σ≈107 S m−1),28 solder,29 and a gallium–indium eutectic.30

We fabricated our electrodes using a metal filling approach, where molten metal is pressure-driven into the channel. The main benefit of this method is ensuing high conductivity of the finished electrode. We chose Field's metal (σ≈2.4 × 106 S m−1), a low-melting temperature non-toxic alloy, for our in-channel metal electrodes. This fabrication method is favourable due to the fast and simple post-processing of PDMS pipettes, which requires only a few minutes of time. No specific instrumentation or expensive materials are required. A certain disadvantage of utilizing this metal is the brittleness; therefore care has to be taken not to damage the electrode while interfacing it with the external voltage source. Too high mechanic stress applied to the metal plug in the well can break the plug apart from the molded wire in the channel. Field's metal does not wet copper wires, making soldering difficult. We found a reliable and convenient way to interface the electrode by using battery spring contacts, applying only slight pressure. Our electrodes exhibited low-resistance (40 Ω), but made the otherwise flexible pipette tip more fragile. Nevertheless, the remaining flexibility was sufficient to tolerate accidental surface collisions during micromanipulation, which would be impossible with glass pipettes. We also observed slight electrode degradation and formation of precipitation around the pipette tip during the application of electrical pulses. In order to eliminate this problem, electrochemical gold plating of the Field's metal tip was a sufficient measure. In alternative approaches, we have attempted to use silver particles (~1 µm diameter) mixed with PDMS, as well as conductive silver pastes and epoxies. We did not succeed to fill the 20 µm × 20 µm channels of our device. The particle suspensions penetrated only a few millimeters into the channel, after which particulates formed and prevented further flow of the composites. Channel filling even did not succeed after applying elevated pressures (up to 3 bar) and extended times (hours). This is consistent with previous reports that these filling methods are successful only with significantly larger channels.

The NG-108-15 cells were prepared the same for both experiments, except for the second set, in which the cells were pre-loaded with a Ca2+ sensitive dye (Method S2†). Pipette and carbon fiber electrodes were mounted to hydraulic micromanipulators (Narishige MC-35A/MHW-3-course/fine). For superfusion, the pipette wells were loaded either with 25 µM fluorescein solution in PBS or with 1 mM calcium chloride in PBS, and with a standard Trypan blue solution for cell viability testing (Invitrogen). For electroporation, the electrodes were connected to a Digitimer DS2A flat-top pulse generator (0–99 V with adjustable pulse length and width between 1–2000 ms), using crocodile clips. All studies were performed using a Leica DM IRE2 confocal microscope with a 40× NA 1.25 oil immersed objective.

The electric field simulations were performed on COMSOL Multiphysics 4.1 with the electric currents (ec) module. The cell was assumed to be an electrically conductive volume with insulating boundaries. All currents and electric fields were treated as stationary. Detailed simulation parameters can be found in Method S4†.

In both experimental sets, the cell membrane viability was tested after electroporation, using Trypan blue as a live-dead stain. This required the pipette to have the capability to switch between the Ca2+ containing PBS solution, and Trypan blue staining solution. This was achieved with the microfluidic circuitry depicted in Fig. 2C. Here, interchanging P1 and P2 and switching vacuum (V) between wells enabled solution switching. Solution exchange occurred in less than 3 s. Switching parameters for the exchange can be found in Table S5†.

Utilising the fluidic pipette to generate a recirculation zone allowed for the contamination free delivery of the desired analyte, fluorescein or Ca2+, to the cell. The delivered analyte did not penetrate into the cell before application of an electroporation pulse of up to 100 V for 1–10 ms. To discover the critical eletroporation parameters, voltage and pulse duration were gradually increased until permeabilization of the membrane occurred. This was indicated by a rapid increase in intracellular fluorescence in both cases (Fig. 3A, B). During our analysis a sample size of ~50 cells was collected, with almost 100% electroporation success rate, tuning the conditions for the individual cells. The viability of each individual addressed cell was not interrogated prior to analysis, and may explain the occasionally observed necrosis upon electroporation. The switching capability of the superfusion pipette allowed for exchange of the Ca2+ solution to Trypan blue, which was initiated after ~1 min of Ca2+ delivery. Within ~30 s of constant exposure, Trypan blue was not observed to penetrate the cell membrane, indicating membrane integrity. Some cells however, appeared to show slight response to external calcium changes, as long as 2.5 min after the electroporation pulse. This passage of calcium, but not Trypan blue, suggests that the membrane retains its viability, but may contain small or closing pores.

Fig. 3.

Targeted single-cell electroporation and fluidic interrogation (A) Single-cell electroporation with an external carbon fiber electrode and simultaneous superfusion with 25 µM fluorescein solution in PBS. The regions of interest and the corresponding intensity graphs are colour coded on the inset image. The superfused cell of interest is represented in green. Fluorescence micrographs of the cell of interest at time points before and after electroporation are displayed as insets on the graph. (B) Single-cell electroporation with the pipette-integrated electrode. The cells were pre-loaded with Calcium-Green™, and superfused using the pipette with 1 mM calcium chloride in PBS. Calcium inflow was monitored via quantitative fluorescence imaging (upper panel). The cell viability was tested by switching the pipette outflow to Trypan blue and monitoring optical transmission (lower panel). The sequence of chemical exposure is represented by a horizontal top bar. Fluorescence (calcium inflow) and transmission (Trypan blue exposure) micrographs of the targeted cell are shown for different time points in the supporting information. (C) An electric field simulation, close to the tip of a carbon fiber electrode. The graph shows the transmembrane potential dependence on the electrode distance D from the cell. The schematic depicts the electrode arrangement with respect to the cell, overlaid with the electrical potential (coloured using a rainbow LUT). (D) The same simulation for a pipette-integrated electrode, where the electrical potential distribution ϕ(solid lines) and transmembrane potential Δϕ (dotted lines) are plotted in relation to pipette height H (distance from device bottom to the glass surface) and distance D from the cell.

In order to elucidate the electric field strength around the cells, a COMSOL study was performed (Fig. 3C,D). Since our estimations (Method S4†) indicated that an essential voltage drop occurs only in a small volume around the electrode tip (> 96%), other resistive components of the bath were neglected. To interpret our simulation results and obtain the membrane potential, the electric potential distribution was monitored along the outer surface of the cell in order to find the highest (ϕhigh) and lowest (ϕlow) values. Even though we do not know explicitly the potential of the cell interior, we can assume that it is constant, since the cell interior can be considered highly conductive compared to its insulating boundaries. Therefore the transmembrane potential should be at least Δϕmembrane ≥ (ϕhigh − ϕlow)/2 at some point along the cell membrane. It is further known that electric potentials across the cell membrane that exceed a critical limit of 0.25–1 V permeablize the membrane.9 Since point electrodes have been used, the electric field in our system is non-homogeneous and heavily dependent on the distance from the electrode (Fig. 3C,D).31 The effective electric field strength drops with increasing distance, with the exception when the pipette is positioned exactly over the cell, In this case symmetry causes smaller potential differences along the cell (Fig. 3D). We found that the voltage difference along the cell membrane is at least 0.1 V per 1 V applied electrode potential for the carbon fiber and 0.06 V/V for the integrated electrode. Therefore, voltage pulses in the ranges of 5–20 V and 8–33 V for an external, and an integrated electrode, respectively, should be sufficient for electroporation. In the experiments, comparable voltage pulses (3–10 V for 2–10 ms) were indeed sufficient to electroporate using the carbon fiber microelectrode. However, voltages larger than predicted by the simulations were needed in case of the Field's metal electrode (30–100 V for 1 ms, even longer pulse durations time did not lower the voltage requirement). An explanation could be a larger voltage drop at the interface between the metal electrode and buffer, which is the only unknown parameter of the resistive chain.

Here we have demonstrated a multifunctional pipette with an integrated electrode, suitable for the electroporation and simultaneous superfusion of single-cells. The use of Field's metal with its low-melting temperature provides a facile bench top method to fabricate low-resistance electrodes in the microfluidic channels, even though it reduces the flexibility of the tip and requires gold plating for chemical stability in some situations. We demonstrated that by combining local superfusion, with single cell electroporation, highly localized sequential delivery of several compounds across the physical boundary of a single cell can be achieved, while eliminating chemical contamination of the surrounding medium, as well as electric field damage of nearby cells. The additional electroporation functionality clearly extends the versatility and performance of the pipette as a multifunctional single-cell manipulation tool. A distinct advantage of this setup is the microfluidic functionality provided by the pipette. Switching between different solutions allows convenient testing of viability and electroporation efficiency during an experiment. Dye penetration could in such a system be utilized as an indicator for, or even feedback of successful electroporation, preceding delivery of active compounds through the pores.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the European Research Council, the Swedish Research Council (VR), the Wallenberg Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) through grant GM R01-066018. We thank Owe Orwar for support and Erik T. Jansson for helpful discussion. We are grateful to Sanofi-Aventis for supporting Nicolas Sanchez' internship in our laboratory.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c2lc40563f

References

- 1.de Souza N. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:35–35. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0710-488b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niepel M, Spencer SL, Sorger PK. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2009;13:556–561. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anselmetti D. Single Cell Analysis. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Charvin G. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:363–363. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0510-363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spiller DG, Wood CD, Rand DA, White MRH. Nature. 2010;465:736–745. doi: 10.1038/nature09232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun J, Stowers CC, Boczko EM, Li D. Lab Chip. 2010;10:2986–2993. doi: 10.1039/c005029f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Messerli MA, Collis LP, Smith PJS. Electroanalysis. 2009;21:1906–1913. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hapala I. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 1997;17:105–122. doi: 10.3109/07388559709146609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olofsson J, Nolkrantz K, Ryttsen F, Lambie BA, Weber SG, Orwar O. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2003;14:29–34. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo D, Saltzman WM. Nat. Biotechnol. 2000;18:33–37. doi: 10.1038/71889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanaka M, Yanagawa Y, Hirashima N. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2009;178:80–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang M, Orwar O, Olofsson J, Weber SG. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010;397:3235–3248. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3744-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ionescu-Zanetti C, Blatz A, Khine M. Biomed. Microdevices. 2008;10:113–116. doi: 10.1007/s10544-007-9115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khine M, Lau A, Ionescu-Zanetti C, Seo J, Lee LP. Lab Chip. 2005;5:38–43. doi: 10.1039/b408352k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee WG, Demirci U, Khademhosseini A. Integr. Biol. 2009;1:242–251. doi: 10.1039/b819201d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olofsson J, Levin M, Stromberg A, Weber SG, Ryttsen F, Orwar O. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:4410–4418. doi: 10.1021/ac062140i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bae C, Butler PJ. BioTechniques. 2006;41:399. doi: 10.2144/000112261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lundqvist JA, Sahlin F, Aberg MAI, Stromberg A, Eriksson PS, Orwar O. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1998;95:10356–10360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aberg MAI, Ryttsen F, Hellgren G, Lindell K, Rosengren LE, MacLennan AJ, Carlsson B, Orwar O, Eriksson PS. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2001;17:426–443. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ainla A, Jansson ET, Stepanyants N, Orwar O, Jesorka A. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:4529–4536. doi: 10.1021/ac100480f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ainla A, Jeffries GDM, Brune R, Orwar O, Jesorka A. Lab Chip. 2012;12:1255–1261. doi: 10.1039/c2lc20906c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juncker D, Schmid H, Delamarche E. Nat. Mater. 2005;4:622–628. doi: 10.1038/nmat1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaigala GV, Lovchik RD, Drechsler U, Delamarche E. Langmuir. 2011;27:5686–5693. doi: 10.1021/la2003639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xia YN, Whitesides GM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1998;37:551–575. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19980316)37:5<550::AID-ANIE550>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi J-W, Rosset S, Niklaus M, Adleman JR, Shea H, Psaltis D. Lab Chip. 2010;10:783–788. doi: 10.1039/b917719a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewpiriyawong N, Yang C, Lam YC. Electrophoresis. 2010;31:2622–2631. doi: 10.1002/elps.201000087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pavesi A, Piraino F, Fiore GB, Farino KM, Moretti M, Rasponi M. Lab Chip. 2011;11:1593–1595. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20084d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Priest C, Gruner PJ, Szili EJ, Al-Bataineh SA, Bradley JW, Ralston J, Steele DA, Short RD. Lab Chip. 2011;11:541–544. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00339e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siegel AC, Shevkoplyas SS, Weibel DB, Bruzewicz DA, Martinez AW, Whitesides GM. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:6877–6882. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.So J-H, Dickey MD. Lab Chip. 2011;11:905–911. doi: 10.1039/c0lc00501k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zudans I, Agarwal A, Orwar O, Weber SG. Biophys. J. 2007;92:3696–3705. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.097683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.