Abstract

Recent emphasis has focused on the development of rationally-designed polymer-based micelle carriers for drug delivery. The current work tests the hypothesis that target specificity can be enhanced by micelles with cancer-specific ligands. In particular, we describe the synthesis and characterization of a new gadolinium texaphyrin (Gd-Tx) complex encapsulated in an IVECT™ micellar system, stabilized through Fe(III) crosslinking and targeted with multiple copies of a specific ligand for the melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), which has been evaluated as a cell-surface marker for melanoma. On the basis of comparative MRI experiments, we have been able to demonstrate that these Gd-Tx micelles are able to target MC1R-expressing xenograft tumors in vitro and in vivo more effectively than various control systems, including untargeted and/or uncrosslinked Gd-Tx micelles. Taken in concert, the findings reported herein support the conclusion that appropriately designed micelles are able to deliver contrast agent payloads to tumors expressing the MC1R.

Keywords: micelle, targeted therapy, melanoma, cancer, nanoparticles, MRI

Introduction

Rationally-designed, polymer-based micelle carriers represent a promising approach to the delivery of therapeutic and/or diagnostic payloads. They offer many potential advantages as delivery agents and could serve to: (1) enhance the solubility of lipophilic drugs; (2) increase circulation times; and (3) lower the toxicity of the payload in question. Micelles with diameters between 20 and 200 nm are particularly attractive as particles of this size can escape renal clearance. This generally translates into longer circulation times and can lead to improved accumulation in tumor tissues as the result of the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect.1, 2 It has also been suggested that selective accumulation in tumors relative to normal tissues can be enhanced through the use of tumor-specific cell-surface targeting groups, and that binding events may be used to trigger release mechanisms. Such strategies are appealing since they could serve not only to enhance uptake in tumor relative to normal tissues, but also to reduce toxicity in peripheral organs.1–3

Despite the advantages offered by micellar delivery systems, to date no micellar system has been described that achieves the full promise of targeting in vivo. Of additional concern is the fate of micelle delivery systems in biological media.4 Previously described micelle delivery systems have suffered from an inherent instability in vivo, generally undergoing collapse in the presence of serum lipids and proteins.4 Micelles can be stabilized for in vivo use through crosslinking of individual acyl chains. To date numerous crosslinking reactions have been attempted, employing strategies that range from the use of disulfides5, 6 and other redox-sensitive bonds7 to temperature-8 and pH-sensitive functional groups.9–11 Here, we report a novel crosslinking procedure that relies on the pH sensitivity of metal-oxygen coordination bonds.12 This particular form of crosslinking is known to increase blood circulation times and result in a stable micelle delivery system that is able to selectively dissociate and release its contents in acidic tumor microenvironments.13

There are a number of micelle-based delivery systems for drugs such as doxorubicin and paclitaxel currently in Phase I and II clinical trials.1, 2 These systems provide for increased circulation times and larger area-under-the curve pharmacokinetics relative to the corresponding free drug. Some systems now in preclinical study are also “passively targeted,”6, 14, 15 meaning they lack any specific surface ligands and rely solely on EPR to deliver their payload.5, 8, 16 A significant disadvantage with passive targeting of micelle delivery systems is an increased probability for nonspecific delivery and accumulation in clearance organs, such as liver and kidney, relative to tumor.2, 17 Additionally, the significance of EPR in human cancers remains largely unproven and there is increasing evidence that EPR alone may not be enough to ensure the selective delivery of a payload.17

Most attempts at micelle targeting have come from the use of ligands such as αvβ3 (RGD), EGFR, or folate.7, 18–23 Unfortunately, most of these targeted systems suffer from a high peripheral toxicity,5, 7, 16, 19, 20 have only seen limited testing in vivo (e.g., in animal models lacking tumor xenografts21, 22), or have not yet quantitatively demonstrated selective tumor accumulation relative to peripheral organs.7, 11, 18, 23, 24 It is also noteworthy that various other targeted systems have been reported to provide little improvement in tumor uptake as compared to their untargeted controls.7, 19, 20 Thus, there remains a need for more specific biological targeting agents, including those that rely on localization strategies that are not EPR dependent. This may be of particular relevance in clinical systems, where it has recently been proposed that human cancers have only a modest EPR as compared to murine xenografts.17

One attractive target is the melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), which is expressed on over 80% of malignant melanomas.25 Not surprisingly, the MC1R has been investigated as a target for delivery of imaging and therapeutic agents. Indeed, a number of MC1R ligands have been developed for this purpose.26–28, 29 The best known of these is based on the melanocyte stimulating hormone (MSH) structure, [Nle4,DPhe7]-α-MSH (NDP-α-MSH),30 and is considered the “gold standard” for in vitro assays due to its ease of synthesis, low cost and high MC1R affinity.29, 31 However, NDP-α-MSH is not selective for MC1R and displays strong nanomolar binding affinities to other melanocortin receptor isoforms, i.e., MC3R, MC4R and MC5R.32–34 MC2R is not avid for MSH-based ligands.35 MC3R and MC4R are primarily expressed in the human brain and CNS36–38 However, MC3R mRNA has been detected in human heart and MC5R mRNA is expressed in human lung and kidney.39 Expression in the brain is less of a concern because MSH-based targeted agents are not likely to cross the blood-brain barrier. Likewise, expression in the heart and lung is not likely to be problematic since, due to their mass, targeted micelles are expected to be restricted to the normal vasculature, although it is anticipated that they will enter tumors due to the permeable tumor vasculature (EPR effect). On the other hand, the expression of MC5R in the kidney is of concern due to kidney involvement in drug clearance, which could lead to off-target binding. Nevertheless it was expected that enhanced delivery to melanomas could be achieved through targeting the MC1R receptor. The present study was designed as an initial test of this hypothesis.

Koikov et al. has reported the development of a ligand, 4-phenylbutyryl-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-NH2, with high selectivity and specificity for MC1R28. We have recently altered this ligand with an alkyne (4-phenylbutyryl-His-DPhe-Arg-Trp-Gly-Lys(hex-5-ynoyl)-NH2; 1)40 for click attachment to a micelle-forming triblock polymer. Moreover, we have demonstrated in vitro that micelles decorated with compound 1 retain the high binding affinity (2.9 nM Ki) of the free ligand and display improved target selectivity.40 In this prior work, the Ki of targeted crosslinked (XL) micelles for MC1R was found be to four times lower than the corresponding targeted uncrosslinked (UXL) micelles while not binding to either of the undesired targets, MC4R or MC5R.40 In this report we show how these micelles can be used to deliver a contrast-enhancing agent.

Texaphyrins are a series of expanded porphyrins that have attracted interest in the area of cancer research.41–44 Gadolinium complexes of texaphyrin (Gd-Tx) have been specifically evaluated in numerous clinical trials, including those for metastatic cancer to the brain, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.43 The incorporation of gadolinium into the texaphyrin macrocycle allows the tissue distribution of Gd-Tx to be studied non-invasively via standard magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) methods.

To develop micelles containing Gd-Tx, we have taken advantage of a triblock polymer micelle system with enhanced stability (IVECT™) that was initially developed by Intezyne Technologies Inc. (Tampa, FL).13, 40 This triblock polymer is composed of a hydrophobic encapsulation block, a responsive stabilizer block, and a hydrophilic masking block that contains an azide for functionalization via click chemistry. The main advantage of IVECT™ micelles over traditional micelles is the incorporation of the stabilization block, which allows the micelles to be crosslinked via a pH-sensitive Fe(III) metal coordination reaction.12, 13, 40 They are also biodegradable and designed to release their payload in the acidic microenvironment of tumors.13 As detailed below, this approach has allowed for the generation of a stabilized IVECT™ micelle system that incorporates Gd-Tx and which both penetrates into xenografted tumors with high selectively and clears from circulation without being retained in the kidney or liver. Tumor penetration, as inferred from MRI studies, was not observed with either untargeted or uncrosslinked micelles. On this basis we suggest that the present approach provides for tumor-specific targeting that is superior to that provided by EPR alone.

Results

Gadolinium-Texaphyrin (Gd-Tx) structure

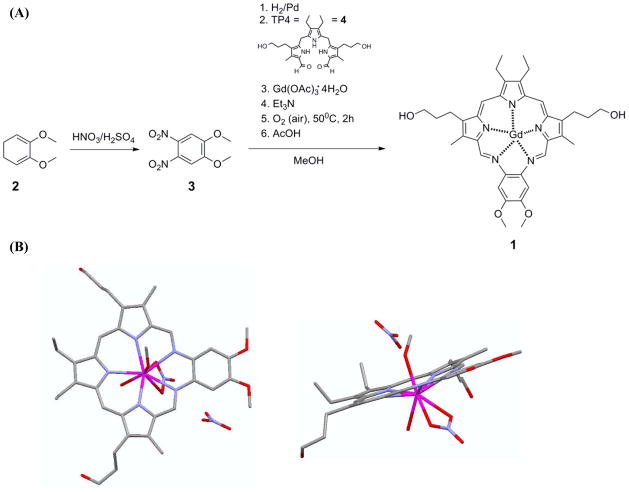

A single crystal X-ray diffraction analysis of the Gd-Tx complex confirmed the expected planar structure for the core macrocycle and revealed several ancillary ligand and solvent interactions (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

(A) Synthesis of gadolinium texaphyrin (Gd-Tx) 1. (B) Crystal structure of 1 obtained from methanol. Detailed information regarding the Gd-Tx crystal structure can be found in the Supporting Information.

Physical properties of the Gd-Tx micelles

The targeted Gd-Tx micelles were prepared using a novel optimized encapsulation strategy (Scheme 2). The average particle size was determined using standard dynamic light scattering (DLS, Particle Characterization Labs, Novato, CA) methods. The surface charge and gadolinium percent loading by weight were determined by zeta potential (Particle Characterization Labs) and elemental analyses (ICP-OES, Galbraith Labs, Knoxville, TN), respectively (Table 1). These studies provided support for the notion that there are no difference in micelle size for the crosslinked (XL) and uncrosslinked (UXL) pairs, or for the targeted (T) and untargeted (UT) pairs. Particle charges ranged from −0.33 to −29 mV as deduced from zeta potential analyses.

Scheme 2.

Formulation of Gd-Tx micelles.

Table 1.

Summary of the physical properties of Gd-Tx micelles.

| Sample # | Stability* | Targeting** | % Gd-Tx Encap. (calculated) | % Gd-Tx Encap. (actual) | Charge (mV) | DLS Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | UXL | UT | 0.54 | 0.51 | −17.70 | 88.90 |

| 2 | UXL | T | 0.53 | 0.50 | −17.74 | 88.80 |

| 3 | XL | UT | 0.52 | 0.52 | −10.73 | 87.50 |

| 4 | XL | T | 0.51 | 0.51 | −9.49 | 82.50 |

Micelles are stabilized with Fe(III) crosslinking (XL) reaction. UXL denotes uncrosslinked micelles.

Micelles are targeted (T) with an MC1R-specific ligand. UT denotes untargeted micelles.

Gd-Tx micelle stability

Crosslinked Gd-Tx micelles were dissolved in PBS at the critical micelle concentration (CMC, 0.02 mg/mL) and dialyzed for 6 hours against PBS (pH 8 and pH 3). HPLC analyses of the Gd-Tx micelles pre- and post-dialysis indicated that the crosslinked micelles retained >95% of the encapsulated Gd-Tx after dialysis at pH 8 and 50% of the encapsulated Gd-Tx at pH 3.

Competitive Binding Assays

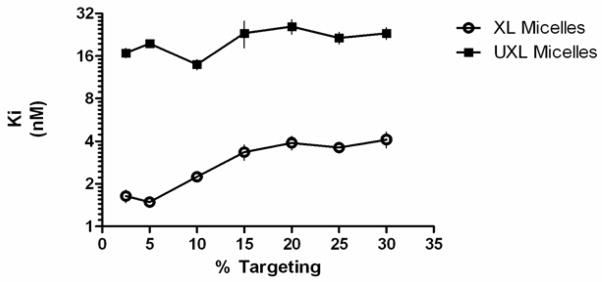

Our established time-resolved lanthanide-fluorescence whole-cell competitive binding assays33, 40 were used to optimize ligand loading for maximal avidity. In these assays, increasing concentrations of micelles conjugated to the targeting ligand 6, a version of NDP-α-MSH with an alkyne for attachment by click chemistry (Scheme 2), were measured for their ability to competitively displace Eu-labeled NDP-α-MSH. The remaining Eu was then measured using time resolved fluorescence (TRF, see Methods). As gadolinium(III) cations can potentially interfere with the lanthanide-based TRF binding assays,33 unloaded triblock polymer micelles (i.e., free of Gd-Tx) targeted with 2.5% to 30% ligand 6 by weight loading (see Scheme 2) were used. Micelles stabilized with Fe(III) crosslinking (6-XL micelles) had the highest binding avidity at 5% ligand loading, as reflected in the lowest Ki (1.49 ± 0.12 nM Ki, n = 4, Figure 1). It was also observed that 6-XL micelles had significantly higher binding avidities at all ligand loading levels (p < 0.001). The same binding assays were also conducted with 5-targeted XL and UXL micelles (5-XL and 5-UXL micelles, Scheme 2) at 5% ligand loading, as well as 5-targeted monomeric polymer. Ligand 5 has greater specificity for MC1R relative to MC4R or MC5R isoforms, which are expressed in the kidney.40 The Ki of the 5-targeted XL micelles (2.9 ± 0.42 nM; n = 4) was 4 times lower than the corresponding UXL micelles (12 ± 2.6 nM; n = 4, Figure 1).40 Control assays with untargeted micelles (UT-XL and UT-UXL) and untargeted monomeric polymer revealed no detectable interaction with the receptor.40

Figure 1.

Effect of % ligand 6 coverage on micelle binding avidity.

In vivo MR imaging

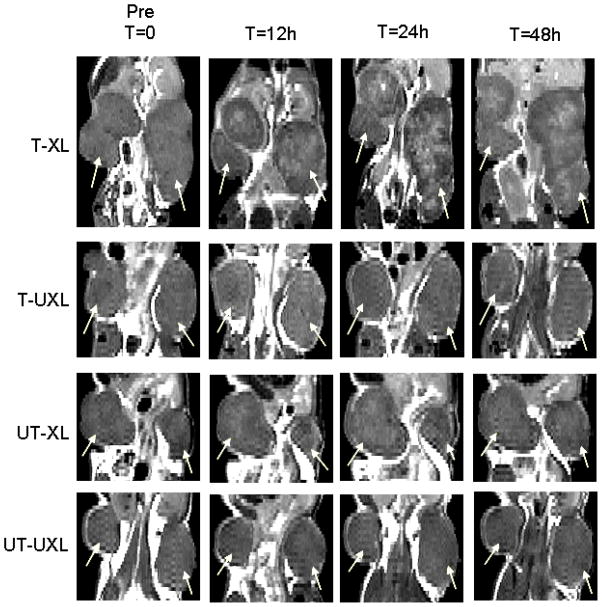

SCID mice with subcutaneous MC1R-expressing tumors were injected with 0.5% w/w Gd-Tx micelles (T-XL, T-UXL, UT-XL, UT-UXL) via tail vein at a dose of 12 μmol Gd-Tx/kg. All targeted micelles used for in vivo imaging studies were formulated with 5% (w/w) of 5-targeted polymer (5-UXL and 5-XL). Using an Agilent 7T small animal MRI spectrometer, coronal T1-weighted spin echo multi slice (SEMS) images were acquired of each animal prior to and 1, 4, 12, 24 and 48 hours after injection of the micelles. Following imaging, MC1R expression was confirmed in each tumor by immunohistochemistry staining (Supplemental Figure S.4). Figure 2 shows representative images of the center slices of the tumors of animals injected with the different 0.5% Gd-Tx loaded micelles recorded at different time-points.

Figure 2.

Coronal-90 T1 weighted spin echo multi slice (SEMS) images of mice treated with different Gd-Tx micelle formulations. A) Representative images from each group of mice treated with 0.5% Gd-Tx micelles at selected time points. White arrows denote location of tumors.

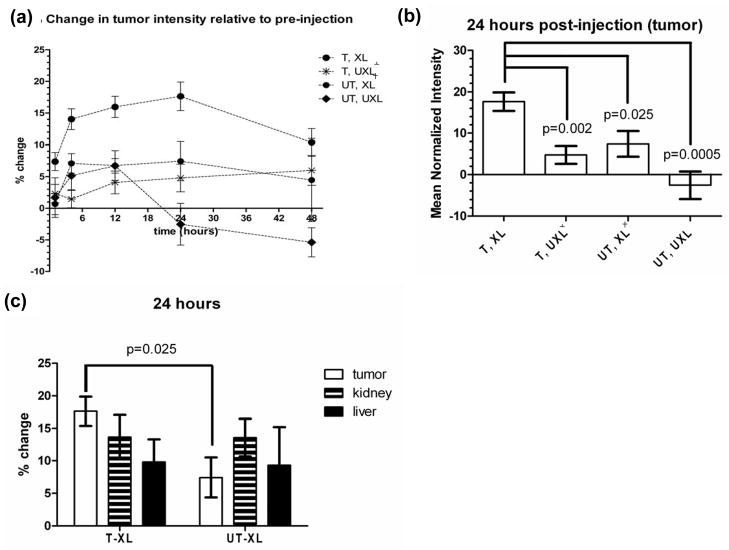

To quantify enhancement due to tumor uptake of the micelles, intensity histograms for right (R) and left (L) whole tumors, kidneys and livers were prepared using a MATLAB program (Mathworks) by drawing a region of interest (ROI) across all applicable slices for each time point. A mean intensity value was then calculated and normalized to thigh muscle as contrast material is not expected to be present in the muscle (see Methods Section). Figure 3 shows the percent change in intensity from pre- to post-injection in tumors (a–b), kidneys (c), and liver (d) for each 0.5% Gd-Tx micelle group over a 48 h time-course (for full clearance data, see Figure S5). By one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Test, the 5-XL micelle group had a significantly higher change in contrast enhancement in the tumors relative to the other groups at all time-points, p<0.05 (3a), with a peak accumulation occurring at 24h (3b). The increased enhancement in the tumors of animals injected with the 0.5% Gd-Tx 5-XL micelles can be visualized in the post-injection MR images (Figure 2, top row) relative to tumors in all other animals injected with the control formulation (UT-XL, 5-UXL, UT-UXL). Again, no other micelle group displayed visible tumor uptake.

Figure 3.

Buildup and clearance data of Gd-Tx contrast enhancement in (a–b) tumor, (c) tumor, liver and kidney (24h). p-values are in comparison to T-XL group. All groups contained 3 mice except where noted. ⊥One mouse expired between 24h and 48h time point. ┼One mouse expired upon injection of micelle agent.

By one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s Multiple Comparison Test, both groups with crosslinked micelles (XL) had a significantly higher change in contrast pre- to post-injection in the kidneys compared to the UXL groups, but there was no significant difference when comparing the 5-XL and UT-XL, or the T-UXL and UT-UXL time courses. Contrast enhancement for the XL micelles peaked in the kidneys ~1–4 h. There was no significant difference in enhancement in the liver among the different time-courses.

Discussion

Europium time-resolved fluorescence (TRF) whole-cell competition binding assays conducted with both 5- and 6-targeted micelles provide support for the central hypothesis underlying this study, namely that crosslinking provides stability to the micelle system and that the composition of the micelle can be modified to allow for targeting. Eu-NDP-α-MSH was chosen as a model ligand for competition due to its relatively high affinity for MC1R (1.9 nM), and for the ease of synthesis that it provides.29, 31 In the percent targeting optimization assays with an alkyne-functionalized NDP-α-MSH (6, Scheme 2), there was a clear difference between the binding affinities of the crosslinked (6-XL) and uncrosslinked (6-UXL) micelles (Figure 1). This finding is ascribed to the Fe(III) crosslinking, which serves to stabilize the micelles in biological media. In the absence of crosslinking, the micelles dissociate, in whole or in part, to free monomers, leading to a loss of structural integrity and the premature release of the payload (the encapsulated contrast agent in the present instance). A second advantage of crosslinking is that it leads to an operational increase in binding avidity, a result that may reflect a benefit of multivalent interactions. The 5-targeted (T) micelles of this study also exhibited a stronger avidity to the MC1R receptor when crosslinked (5-XL) as compared to their uncrosslinked counterpart (T-UXL), a finding we take as further support for the contention that i) crosslinking stabilizes micelles and ii) multiple ligands on the micelle surface provide for enhanced binding.

The above Gd-Tx containing micelles (0.5% Gd-Tx w/w) were further studied in vivo. In accord with the design expectations, these in vivo experiments revealed improved MRI contrast enhancements upon administration of the Gd-Tx containing 5-XL micelles, with maximal enhancement observed at 24 h. As can be seen by an inspection of Figures 2 and 3, this enhancement was not seen with the other micelle systems, supporting the contention that the 5-XL micelles provide good systems for effecting tumor localization and payload delivery. The maximum enhancement was 17% compared to pre-injection images. While this enhancement is likely not large enough to be clinically valid for imaging in the current formulation, it is encouraging that similar stabilized micelle formulations have demonstrated significant tumor uptake of therapeutic payload and increased therapeutic efficacy relative to untargeted drug administration.13, 45 The results of this study thus provide support for the contention that targeted formulations can provide for improvements in efficacy through increased delivery of payload throughout the tumor.

Although the in vivo studies were conducted using a colorectal cancer cell line (HCT116) engineered to express MC1R at a level of 240,000 receptors per cell,46 we have recently conducted in vivo studies using the same MC1R targeting ligand (5) conjugated to a near-infrared fluorescent dye and using melanoma tumor lines with high (B16) and low (A375) endogenous expression of MC1R.47 Blocking studies demonstrated specific uptake of the labeled ligand into tumors bearing these melanoma cells and uptake was correlated with MC1R expression levels. To demonstrate clinical relevance, additional work will be needed that, inter alia, demonstrates uptake of ligand 5 targeted micelles into tumor xenografts containing melanoma cells with lower endogenous MC1R expression levels. However, these future studies lie outside the scope of the present proof-of-principle analyses.

The unique ability of the 5-XL micelles to penetrate the tumor appears to result from a combination of the MC1R-specific targeting group and the enhanced stability provided by the Fe(III) crosslinking. If targeting alone were enough to produce effective tumor enhancement, we would also observe a substantial uptake in the case of the 5-UXL micelles. Likewise, if crosslinking and EPR alone were enough to affect accumulation, we would observe an increased build-up in the UT-XL group. Finally, it is important to note that the enhancement observed in the 5-XL group was not the result of free Gd-Tx (which is known to accumulate in tumors selectively42, 43, 48, 49). If this were the case, we would have observed enhanced uptake in all four micelle groups (i.e., UT-UXL, 5-UXL and UT-UXL, in addition to the 5-XL system). This was not seen; thus, the in vivo data are consistent with the conclusion that the Gd-Tx containing 5-XL micelles allow for functionally acceptable binding avidity, stability, tumor penetration and uptake. Presumably, the crosslinking reaction stabilizes the micelles after administration and during initial time points while they circulate throughout the bloodstream, while the targeting group allows the system to bind to, and be retained within, the tumor cells. Interestingly, the XL micelle groups had significantly elevated enhancement in the kidneys relative to the UXL groups, although this uptake was non-specific. This may be a result of the increased stability of the XL micelles resulting in longer circulation times and slower rates of complete clearance through the renal system into the bladder. Also, the timing of kidney clearance of the XL micelles is comparable in timing to near-infrared fluorescent dye conjugates to monoclonal antibodies with comparable mass.50

We have previously reported the development of a ligand specific to MC1R and we have shown that the conjugation of this ligand to the IVECT™ micelle system does not result in a significant decrease in binding avidity.40 In this report, we describe the synthesis, incorporation and characterization of a new gadolinium texaphyrin (Gd-Tx) that is characterized by a high inherent T1 relaxivity. We also detail its encapsulation within the IVECT™ system and the production of crosslinked micelles by reaction with Fe(III). Moreover, we have demonstrated that the targeted Gd-Tx micelles are selectively retained in target-expressing xenograft tumors in vivo. As expected, MRI contrast enhancement was not visually observed within the heart, lung, brain or CNS following clearance from vascular circulation. While non-specific uptake into the kidney and liver was observed, targeted micelles were not specifically retained in the kidney relative to untargeted which suggests only non-specific clearance as opposed to off-target uptake in these organs. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of a targeted micelle that is capable of carrying a payload and which outperforms systems based on EPR in terms of tumor penetration, uptake and retention.

Advantages of the current system include the following: (1) the target, MC1R, is highly expressed in melanoma cells and not in healthy tissues, except for melanocytes; (2) high short term stability, and (3) an ability to specifically accumulate in tumors, compared to non-specific uptake in clearance organs. These attributes are reflected in the in vivo images that reveal uptake of targeted constructs relative to untargeted deep within the tumor with peak accumulation at 24 h. In contrast, peak non-specific accumulations in the kidney and liver accumulations were seen at 1–4 h. These differences are thought to reflect the benefits of targeting. However, biodegradation of the stabilized micelles may also contribute to the effect; to the extent it occurs on short time scales (on the order of hours), it would allow for release of payload (Gd-Tx) within the tumor while concurrently clearing from circulation. While further investigations will be required to detail the full pharmacokinetic profile of these new micelles, and to develop formulations that deliver more clinically relevant payloads, it is important to appreciate that from an operational perspective the systems of this report constitute the first example of targeted micellar constructs that are capable of delivering payloads in a tumor selective fashion.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of Gd-Tx

All chemicals were obtained from commercial sources (Fisher Scientific, Acros Chemicals, Sigma-Aldrich or Strem Chemicals) and used as supplied unless otherwise noted. All solvents were of reagent grade quality. Fisher silica gel (230–400 mesh, Grade 60 Å) and Sorbent Technologies alumina (neutral, standard activity I, 50–200 μm) were used for column chromatography. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) analyses were performed on silica gel (aluminum backed, 200 μm or glass backed, 250 μm) or alumina neutral TLC plates (polyester backed, 200 μm), both obtained from Sorbent Technologies. Low- and high-resolution ESI mass spectra (MS) were obtained at the Mass Spectrometry Facility at The University of Texas at Austin using a Thermo Finnigan LTQ instrument and an Qq FTICR (7 Tesla) instrument, respectively. HPLC spectra were taken on a Shimadzu High Performance Liquid Chromatograph (Fraction Collector Module FRC-10A, Auto Sampler SIL-20A, System Controller CBM-20A, UV/Vis Photodiode Array Detector SPD-M20A, Prominence). The tripyrrane dialdehyde species 4 (generally referred to as “TP-4”) was provided by Pharmacyclics Inc. and synthesized as previously described.49 The precursor 1,2-dimethoxy-4,5-dinitrobenzene 3 was synthesized as previously described.51

The gadolinium complex used in this study (Gd-Tx 1) was prepared as shown in Scheme 1. Briefly, compound 3 (1 g, 4.38 mmol) was dissolved in 10 mL methanol and placed in a hydrogenation flask. The solution was purged with nitrogen for 5 minutes and palladium on activated carbon (10%, 0.1 g) was added. The mixture was degassed and allowed to react with hydrogen gas at 100 psi with agitation for 18 hours, filtered under Schlenk conditions through a minimal pad of Celite, and added instantly to a solution of TP-4 4 (2.11 g, 4.38 mmol) in 15 mL methanol under nitrogen at 70 °C. Aqueous hydrochloric acid was added (2 mL, 0.5 M) and the deep red reaction mixture was stirred for 4 hours. Next, gadolinium acetate tetrahydrate (2.67 g, 6.57 mmol, 1.5 equiv) was added together with 3 ml triethylamine and the solution was stirred at 70 °C for 16 hours, during which time the solution gradually changed color from deep red to deep green. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue was subjected to column chromatography (silica gel). To remove apolar impurities, the column was eluted with a mixture of 95% CH2Cl2 and 5% MeOH. The product slowly starts to elute when a mixture of 60% CH2Cl2 and 40% MeOH is used as the eluent. The deep green fraction isolated using this eluent mixture was collected and the solvent was removed in vacuo to give 1 (Gd-Tx) as a deep green crystalline material (1.63 g, 42%). UV/Vis (MeOH, 25 °C): λmax = 470 (Soret-type band); 739 (Q-type band); Low Resolution MS (ESI in MeOH): 797.25 (M+ - 2OAc + OMe), 825.42 (M+ - OAc). High Resolution MS (ESI in MeOH): calculated for [C38H45N5O6Gd+1]+ = 825.2611; found: 825.2621 ([C38H45N5O6Gd+1]+; M+ - OAc). The Gd-Tx 1 samples used in the present study were confirmed as 99.5% pure by HPLC. Additional data, including mass spectra and HPLC traces for Gd-Tx 1 can be found in the Supporting Information.

Crystalization of Gd-Tx and determination of structure

Crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained by dissolving Gd-Tx 1 (2 mg, 2.26 μmol) in 1 mL methanol. Sodium nitrate (0.2 mg, 4 equiv.) was added and the solution was heated to reflux at 60 °C for 24 hours. At this point, 0.25 mL chloroform was added and the solution was placed in a vial and diethyl ether was allowed to slowly diffuse into the solution at 5 °C. For full crystallographic data, see Supporting Information. Further details of the structure may also be obtained from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre by quoting CCDC number 859294.

Synthesis of targeted triblock polymers

IVECT™ triblock polymers with a terminal azide were obtained from Intezyne Technologies (Tampa, FL) and either 540 or 6 were synthesized (Scheme 2) and analyzed for purity (>95%) by analytical HPLC and MS by ESI or MALDI-TOF and used as the MC1R-selective ligand. Standard click chemistry was conducted as previously published.40 Unconjugated polymer was characterized by NMR and GPC analysis, which showed a single, monomodal peak. The polymer conjugated to the MC1R-selective ligand was determined by NMR to be >95% pure.

Formulation and stabilization of Gd-Tx micelles

For targeted formulations, a percentage (5% in most cases) of the targeted polymer was used and the remainder (95% in most cases) was made up of untargeted polymer. The triblock polymer (750 mg) was dissolved in water (150 mL) at a concentration of 5 mg/mL and stirred with slight heating until fully dissolved. After cooling to room temperature, the polymer solution was placed in a sheer mixer and the Gd-Tx 1 solution (0.5% w/w in 380 μL dimethyl sulfoxide) was added. The resulting solution was then passed through a microfluidizer (Microfluidics M-110Y) at 23,000 PSI, filtered through a 0.22 μm Steriflip-GP Filter Unit (Millipore) and lyophilized.

For stabilized formulations, micelles were subject to an Fe(III)-mediated crosslinking reaction.12 FeCl3 was prepared at concentration of 1.35 g/mL in 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.4). The targeted and untargeted micelles were then dissolved in the Fe(III)-Tris solution at a concentration of 20 mg/mL and the solution was adjusted to pH 8 through the dropwise addition of 0.1 – 1.0 M aqueous NaOH. The crosslinking reaction was stirred for 12 hours and the contents of the reaction vessel were then lyophilized.

Cell Culture

HCT116 cells overexpressing hMC1R were engineered in our lab. HCT116 cells were transfected with the pCMV6-Entry Vector (Origene; RC 203218) using the Fugene 6 transfection reagent (Roche; 1814-443). Transfected cells were grown in a selection media containing 0.4 mg/ml geneticin (Life Technologies; 11811-031) and tested for the hMC1R cell surface expression by saturation binding assay.23 Cells were maintained under standard conditions (37°C and 5% CO2) and were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and 5% penicillin/streptomycin. Geneticin (G418S, 0.8%) was added to the media to ensure proper selection. hMC1R expression was verified through immunohistochemistry (IHC, see Supplemental Information).

Europium Binding Assays

Our established europium lanthanide time-resolved fluorescence whole-cell saturation and competitive binding assays were conducted as previously published using the HCT116 cells engineered to express MC1R and the Eu-NDP-α-MSH ligand which has known binding affinity for MC1R.33, 40

In vivo murine tumor models

All animal experiments were conducted under a protocol approved by the University of South Florida Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). These experiments adhere to the guidelines on the care and use of animals in research. HCT116/hMC1R-expressing flank tumor xenograft models were studied in female SCID/beige mice obtained from Harlan Laboratories at 6–8 weeks of age. HCT116/hMC1R cells were injected at concentrations of 3 × 106–10 × 106 cells per 0.1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline. Tumor volume measurements were made bi-weekly and calculated by multiplying the length by the width squared and dividing by two. Final volume measurements were determined through ROI analysis on the MRI and all tumors imaged ranged from 300 to 500 mm3 in volume.

MRI Imaging and Analysis

All imaging was completed on a 7 Tesla, 30 cm horizontal bore Agilent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) spectrometer ASR310 (Agilent Life Sciences Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Once the tumors in the animals reached an average of ~500 mm3, the animals were pair-matched by tumor size and sorted into four groups to receive the following micelles: 5-XL; UT-XL; 5-UXL; or UT-UXL. Each animal was imaged the day before micelle injection for “pre” images. The following morning, each animal was individually administered 12 μmol/kg Gd-Tx (as Gd-Tx micelles) dissolved in 200 uL saline, via tail vein injection, and the time of injection was noted. Follow-up MRI images were taken at 1hr, 4 hr, 12hr, 24 and 48h post-injection of the micelles.

All animals were sedated using isoflurane and remained under anesthesia for the duration of the imaging. Animals were kept at body temperature (~37 °C) using a warm air blower; the temperature of the air was adjusted to maintain the body temperature and was monitored using a fiber optic rectal probe. SCOUT images were taken to determine animal position within the magnet and setup the slices for the T1 weighted spin echo multi slice (SEMS) images. The SEMS images were taken as coronal-90 images (read direction along the X-axis, phase-encode along the Z-axis), with data matrix of 128 × 128 and a FOV of 40 mm (read) × 90 mm (phase); 15 one-mm thick slices were taken with a 0.5 mm gap between slices; the TR was 180 ms, and TE was 8.62 ms; there were 8 averages taken for each image, resulting in a total scan time of about 3 minutes per SEMS image.

Images were processed using MATLAB (Mathworks, Natick, MA) to draw regions of interest (ROI) in the tumors, kidney, liver and thigh muscle over multiple slices for each mouse at each time point. All intensities for each area of interest were averaged to determine a mean intensity. The mean intensity of each area was then normalized to the mean intensity of the thigh to generate a normalized intensity (NI):

A percent change value was then calculated by comparing each normalized time point after injection to the normalized pre-injection intensity mean:

Since the right and left tumors are histologically equivalent (Figure S.4), the % change values for all tumors were averaged to obtain an “average tumor % change” at time points 1 – 24 h. Percent change values were also averaged for R and L kidney to obtain an “average kidney % change” at time points 1 – 24 h.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research was funded by the Bankhead Coley Melanoma Pre-SPORE Program (Grant 02-15066-10-03) to D.L.M., NIH/NCI (Grant R01 CA 097360 to R.J.G. and D.L.M.; CA 68682 to J.L.S.), and Intezyne Inc. (Award #84-16301-01-01) to R.J.G. for a portion of N.M.B.’s salary and polymer materials.

The authors would like to acknowledge Professor Dean Sherry (UTSW) for his invaluable wisdom and insight.

Abbreviations

- IVECT

Trademarked name of Intezyne Technology’s tri-block polymer

- Gd-Tx

Gadolinium texaphyrin

- RGD

Integrin αvβ3 three amino-acid residue ligand (arginine, glycine, aspartic acid)

- MC1R

Melanocortin 1 receptor

- MSH

Melanocyte stimulation hormone

- MC3R

Melanocortin 3 receptor

- MC4R

Melanocortin 4 receptor

- MC5R

Melanocortin 5 receptor

- MC2R

Melanocortin 2 receptor

- XL

Crosslinked

- UXL

Uncrosslinked

- T

Targeted

- UT

Untargeted

- TRF

Time resolved fluorescence

- SEMS

Spin echo multi slice

- R

Right

- L

Left

- ROI

Region of interest

- IACUC

Institutional animal care and use committee

Footnotes

Competing Financial Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing of this manuscript.

Ancillary Information:

“Supporting information available that includes analytic spectra for compound; immunohistochemical staining of xenograft tumors for MC1R expression; a quantified time-course of liver, kidney and tumor clearance; in vitro phantom imaging data; and X-ray crystallography data for compound 1. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org”

References

- 1.Yokoyama M. Clinical Applications of Polymeric Micelle Carrier Systems in Chemotherapy and Image Diagnosis of Solid Tumors. J Exp Clin Med. 2011;3:151–158. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oerlemans C, Bult W, Bos M, Storm G, Nijsen JFW, Hennink WE. Polymeric micelles in Anticancer Therapy: Targeting, Imaging, and Triggered Release. Pharm Res. 2010;27:2569–2589. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0233-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kedar U, Phutane P, Shidhaye S, Kadam V. Advances in Polymeric Micelles for Drug Delivery and Tumor Targeting. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine. 2010;6:714–729. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim S, Shi Y, Kim JY, KP, Chen JX. Overcoming the barriers in micellar drug delivery: loading efficiency, in vivo stability, and micelle–cell interaction. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2010;7:49–62. doi: 10.1517/17425240903380446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shiraishi K, Kawano K, Maitani Y, Yokoyama M. Polyion Complex Micele MRI Contrast Agents from Poly (ethylene glycol)-b-poly(L-lysine) Block Copolymers having Gd-DOTA; Preparations and their COntrol of T1 Relaxitivities and Blood Circulation Characteristics. J Controlled Release. 2010:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, Huo M, Wang J, Zhou J, Mohammas J, Zhang Y, Zhu Q, Waddad A, Zhang Q. Redox-sensitive micelles self-assembled from amphiphilic hyaluronic acid-deoxycholic acid conjugates for targeted intracellular delivery of paclitaxel. Biomaterials. 2012;33:2310–2320. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee H, Hoang B, Fonge H, Reilly R, Allen C. In-vivo Distribution of Polymeric Nanoparticles at the Whole Body, Tumor and Cellular Levels. Pharmaceutical Research. 2010;27:2343–2355. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0068-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim T, Chen Y, Mount C, Gambotz W, Li X, Pun S. Evaluation of Temperture-Sensitive, Indocyanine Green-Encapsulating Micelles for Noninvasive Near-Infrared Tumor Imaging. Pharm Res. 2010;27:1900–1913. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0190-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jia Z, Wong L, Davis TP, Bulmus V. One-pot conversion of RAFT-generated multifunctional block copolymers of HPMA to doxorubicin conjugated acid- and reductant-sensitive crosslinked micelles. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:3106–3113. doi: 10.1021/bm800657e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang X, Grailer JJ, Pilla S, Steebe DA, Gong S. Tumor-Targeting, pH-Responsive, and Stable Unimolecular Micelles as Drug Nanocarriers for Targeted Cancer Therapy. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010;21:496–504. doi: 10.1021/bc900422j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Xio W, Xiao K, Berti L, Luo J, Tseng H, Fung G, Lam K. Well-definied reversible boronate crosslinked nanocarriers for targeted drug delivery in response to acidic pH values and cis-diols. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:1–7. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cannan RK, Kibrick A. Complex Formation between Carboxylic Acids and Divalent Metal Cations. J Am Chem Soc. 1938;60:2314–2320. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rios-Doria J, Carie A, Costich T, Burke B, Skaff H, Panicucci R, Sill K. A versatile polymer micelle drug delivery system for encapsulation and in vivo stabilization of hydrophobic anticancer drugs. J Drug Delivery. 2012;2012:951741. doi: 10.1155/2012/951741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun TM, Du JZ, Yao YD, Mao CQ, Dou S, Huang SY, Zhang PZ, Leong K, Song EW, Wang J. Simultaneous delivery of siRNA and pacilitaxel via a “two-in-one” micelleplex promotes synergistic tumor supression. ACS Nano. 2011;5:1483–1494. doi: 10.1021/nn103349h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koo H, Huh M, Sun IC, Yuk S, Choi K, Kim K, Kwon I. In vivo targeted delivery of nanoparticles for theranosis. Accounts of Chemical Research. 2011;44:1018–1028. doi: 10.1021/ar2000138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang N, Dy G, Wang N, Liu C, Hang H, Liang W. Improving Penetration in Tumors with Nanoassemblies of Phospholipids and Doxorubicin. JNCI. 2007;99:1004–1015. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chrastina A, Massey KA, Schnitzer JE. Overcoming in vivo barriers to targeted nanodelivery. Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology. 2011;3:421–437. doi: 10.1002/wnan.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessinger C, Khemtong C, Togao O, Takahashi M, Sumer B, Gao J. In-vivo angiogenesis imaging of solid tumors by avb3-targeted, dual-modality micellar nanoprobes. Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2010;235:957–965. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poon Z, Lee J, Huang S, Prevost R, Hammond P. Highly Stable, Ligand Clustered “Patchy” Micelle Nanocarriers for Systemic Tumor Targeting. Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and medicine. 2010:1–30. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee H, Fonge H, Hoang B, Reilly R, Allen C. The Effects of Particle Size and Molecular Targeting on teh Intratumoral and Suncellular Distribution of Polymeric Nanoparticles. Molecular Pharmaceutics. 2010;7:1195–1208. doi: 10.1021/mp100038h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu J, Qian Y, Wang X, Liu W, Liu S. Drug-Loaded and Superparamagnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Surface-Embedded Amphiphilic Block Copolymer Micelles for Integrated Chemotherapeutic Drug Delivery and MR Imaging. Langmuir. 2012 doi: 10.1021/la203992q. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu T, Liu X, Qian Y, Hu X, Liu S. Multifunctional pH-Disintegrable micelle nanoparticles of asymmetrically functionalized beta-cyclodextrin-based star copolymer covalently conjugated with doxorubicin and DOTA-Gd moieties. Biomaterials. 2012;33:2521–2531. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiong XB, Lavasanifar A. Traceable Multifunctional Micellar nanocarriers for Cancer-Targeted Co-delivery of MDR-1 siRNA and Doxorubicin. ACS Nano. 2011;5:5202–5213. doi: 10.1021/nn2013707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang R, Meng F, Ma S, Huang F, Liu H, Zhong Z. Galactose-decorated cross-linked biodegradable poly9ethylene glycol)-b-poly(E-caprolactone) block copolymer micelles for enhanced hepatoma-targeting delivery of paclitaxel. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:3047–3055. doi: 10.1021/bm2006856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siegrist W, Solca F, Stutz S, Giuffre L, Carrel S, Girard J, Eberle AN. Characterization of receptors for alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone on human melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6352–6358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai M, Varga EV, Stankova M, Mayorov A, Perry JW, Yamamura HI, Trivedi D, Hruby VJ. Cell signaling and trafficking of human melanocortin receptors in real time using two-photon fluorescence and confocal laser microscopy: differentiation of agonists and antagonists. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2006;68:183–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2006.00432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mayorov AV, Han SY, Cai M, Hammer MR, Trivedi D, Hruby VJ. Effects of macrocycle size and rigidity on melanocortin receptor-1 and -5 selectivity in cyclic lactam alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone analogs. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2006;67:329–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2006.00383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koikov LN, Ebetino FH, Solinsky MG, Cross-Doersen D, Knittel JJ. Sub-nanomolar hMC1R agonists by end-capping of the melanocortin tetrapeptide His-D-Phe-Arg-Trp-NH(2) Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003;13:2647–2650. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00552-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J, Giblin MF, Wang N, Jurisson SS, Quinn TP. In vivo evaluation of 99mTc/188Re-labeled linear alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone analogs for specific melanoma targeting. Nucl Med Biol. 1999;26:687–693. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(99)00032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sawyer T, Sanfilippo P, Hruby V, Engel M, Heward C, Burnett J, Hadley M. 4-Norleucine, 7-D-phenylalanine-alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone: a highly potent alpha-melanotropin with ultralong biological activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:5754–5758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.10.5754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J, Cheng Z, Hoffman TJ, Jurisson SS, Quinn TP. Melanoma-targeting properties of (99m)technetium-labeled cyclic alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone peptide analogues. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5649–5658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai M, Mayorov AV, Cabello C, Stankova M, Trivedi D, Hruby VJ. Novel 3D Pharmacophore of r-MSH/α-MSH Hybrids Leads to Selective Human MC1R and MC3R Analogues. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1839–1848. doi: 10.1021/jm049579s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Handl HL, Vagner J, Yamamura HI, Hruby VJ, Gillies RJ. Lanthanide-based time-resolved fluorescence of in cyto ligand-receptor interactions. Anal Biochem. 2004;330:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Y, Hruby VJ, Chen M, Crasto C, Cai M, Harmon CM. Novel Binding Motif of ACTH Analogues at the Melanocortin Receptors. Biochemistry. 2009;48:9775–9784. doi: 10.1021/bi900634e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang L, Angleson JK, Dores RM. Using the human melanocortin-2 receptor as a model for analyzing hormone/receptor interactions between a mammalian MC2 receptor and ACTH(1–24) Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2013;181:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hruby VJ, Cai M, Cain JP, Mayorov AV, Dedek MM, Trivedi D. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of ligands selective for the melanocortin-3 receptor. Curr Top Med Chem. 2007;7:1107–1119. doi: 10.2174/156802607780906645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sohn JW, Harris LE, Berglund ED, Liu T, Vong L, Lowell BB, Balthasar N, Williams KW, Elmquist JK. Melanocortin 4 receptors reciprocally regulate sympathetic and parasympathetic preganglionic neurons. Cell. 2013;152:612–619. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biebermann H, Kuhnen P, Kleinau G, Krude H. The neuroendocrine circuitry controlled by POMC, MSH, and AGRP. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2012:47–75. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-24716-3_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chhajlani V. Distribution of cDNA for melanocortin receptor subtypes in human tissues. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1996;38:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barkey NM, Tafreshi NK, Josan JS, Silva CRD, Sill KN, Hruby VJ, Gillies RJ, Morse DL, Vagner J. Development of melanoma-targeted polymer micelles by conjugation of an MC1R specific ligand. J Med Chem. 2011;54:8078–8084. doi: 10.1021/jm201226w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Young SW, Qing F, Harriman A, Sessler JL, Dow WC, Mody TD, Hemmi GW, Hoill Y, Miller RA. Gadolinium(III) texaphyrin: A tumor selective radiation sensitizer that is detectable by MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6610–6615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sessler JL, Miller RA. Texaphyrins. New Drugs with Diverse Clinical Applications in Radiation and Photodynamic Therapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:733–739. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00314-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Viala J, Vanel D, Meingan P, Lartigau E, Carde P, Renchler M. Phases IB and II Multidose Trial of Gadolinium Texaphyrin, a Radiation Sensitizer Detectable at MR Imaging: Preliminary Results in Brain Metastases. Radiology. 1999;212:755–759. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.3.r99se10755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sessler JL, Mody TD, Hemmi GW, Lynch V, Young SW, Miller RA. Gadolinium(III) texaphyrin: a novel MRI contrast agent. J Am Chem Soc. 1993;115:10368–10369. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carie A, Rios-Doria J, Costich T, Burke B, Slama R, Skaff H, Sill K. IT-141: a Polymer Micelle Encapsulating SN-38, Induces Tumor Regression in Multiple Colorectal Cancer Models. J Drug Deliv. 2011;2011:869027. doi: 10.1155/2011/869027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu L, Josan JS, Vagner J, Caplan MR, Hruby VJ, Mash EA, Lynch RM, Morse DL, Gillies RJ. Heterobivalent ligands target cell-surface receptor combinations in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:21295–21300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211762109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tafreshi NK, Huang X, Moberg VE, Barkey NM, Sondak VK, Tian H, Morse DL, Vagner J. Synthesis and characterization of a melanoma-targeted fluorescence imaging probe by conjugation of a melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) specific ligand. Bioconjug Chem. 2012;23:2451–2459. doi: 10.1021/bc300549s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sessler JL, Krill V, Hoehner MC, Chin KOA, Davila RM. New texaphyrin-type expanded porphyrins. Pure & Appl Chem. 1996;68:1291–1295. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sessler JL, Mody TD, Hemmi GW, Lynch VM. Synthesis and Structural Characterization of lanthanide(III) texaphyrins. Inorg Chem. 1993;32:3175–3187. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tafreshi NK, Bui MM, Bishop K, Lloyd MC, Enkemann SA, Lopez AS, Abrahams D, Carter BW, Vagner J, Grobmyer SR, Gillies RJ, Morse DL. Noninvasive detection of breast cancer lymph node metastasis using carbonic anhydrases IX and XII targeted imaging probes. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:207–219. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ehrlich J, Bogert MT. Experiments in the veratrole and quinoxaline groups. J Org Chem. 1947;12(4):522–534. doi: 10.1021/jo01168a006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.