Abstract

Renal hypoxia occurs in AKI of various etiologies, but adaptation to hypoxia, mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), is incomplete in these conditions. Preconditional HIF activation protects against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury, yet the mechanisms involved are largely unknown, and HIF-mediated renoprotection has not been examined in other causes of AKI. Here, we show that selective activation of HIF in renal tubules, through Pax8-rtTA–based inducible knockout of von Hippel-Lindau protein (VHL-KO), protects from rhabdomyolysis-induced AKI. In this model, HIF activation correlated inversely with tubular injury. Specifically, VHL deletion attenuated the increased levels of serum creatinine/urea, caspase-3 protein, and tubular necrosis induced by rhabdomyolysis in wild-type mice. Moreover, HIF activation in nephron segments at risk for injury occurred only in VHL-KO animals. At day 1 after rhabdomyolysis, when tubular injury may be reversible, the HIF-mediated renoprotection in VHL-KO mice was associated with activated glycolysis, cellular glucose uptake and utilization, autophagy, vasodilation, and proton removal, as demonstrated by quantitative PCR, pathway enrichment analysis, and immunohistochemistry. In conclusion, a HIF-mediated shift toward improved energy supply may protect against acute tubular injury in various forms of AKI.

No specific therapy is currently available for human AKI, a clinical entity of increasing incidence and high morbidity and mortality.1–4 Rhabdomyolysis, one of the leading causes of AKI, develops after trauma, drug toxicity, infections, burns, and physical exertion.5–8 The animal model using an intramuscular glycerol injection with consequent myoglobinuria is closely related to the human syndrome of rhabdomyolysis.9 Experimental data demonstrate renal vasoconstriction,9–15 tubular hypoxia,15,16 normal or even reduced intratubular pressure,9–11 as well as large variation in single nephron GFR.10,11 Intratubular myoglobin casts, a histologic hallmark, seem not to cause tubular obstruction,9–11 but rather scavenge nitric oxide17,18 and generate reactive oxygen species19 followed by vasoconstriction.

The traditional discrimination between ischemic and toxic forms of AKI has been challenged because an increasing amount of evidence suggests that renal hypoxia is a common denominator in AKI of different etiologies.20 Pimonidazole adducts, which accumulate in tissues at oxygen tensions <10 mmHg,21 have been demonstrated in various AKI forms.16,22–24 During AKI, hypoxia-inducible factors (HIFs), which are mainly regulated by oxygen-dependent proteolysis, were found to be upregulated in different renal tubular segments.16,20,22,24,25 HIFs are heterodimers of a constitutive β subunit, HIF-β (ARNT), and one of three oxygen-dependent α-subunits, HIF-1α, HIF-2α, and HIF-3α. The α-β dimers bind to hypoxia-response elements (HREs) in the promoter-enhancer region of HIF target genes.26–28 Although the 5′-RCGTG-3′ (R = A or G) core HRE appears >1 million times in the entire genome29 and in >4000 promoter regions of validated genes,30 a recent study demonstrated HIF binding in roughly 350 genes.31 Multiple HIF-based biologic effects are known, and it is widely accepted that a broad panel of these promote cellular survival in a hostile and oxygen-deprived environment.27–29 In all types of AKI tested thus far, HIF activation along the nephron correlates with tubular survival, and the cells most vulnerable to injury exhibit no or only very limited HIF activity.20 This observation led to the concept of insufficient HIF-based hypoxic adaptation in AKI. Consequently, maneuvers of preconditional HIF activation are utilized to ameliorate AKI. Indeed, many of these attempts are successful but the majority are conducted in ischemia-reperfusion injury.20 It is largely unclear whether HIF can rescue kidneys exposed to AKI forms other than ischemia-reperfusion injury, and it is unclear which HIF target genes are involved in AKI protection if so. In many tumors, constitutive HIF activation promotes anaerobic ATP production, a process known as the Warburg effect.32

von Hippel-Lindau protein (VHL) is a ubiquitin ligase engaged in the stepwise HIF-α degradation process, which constantly occurs during normoxia.33 Inducible Pax8-rtTA–based knockout of VHL (VHL-KO) achieves strong, selective, and persistent upregulation of HIF in all nephron segments.34 In this study, we use this transgenic technique in conjunction with rhabdomyolysis in mice to address two issues: (1) Does HIF activation through VHL-KO protect from rhabdomyolysis-induced AKI? (2) If so, what are the biologic mechanisms and HIF target genes that are responsible for renal protection against acute injury? We demonstrate that indeed VHL-KO mice are largely protected against rhabdomyolysis-induced AKI, and provide evidence for a metabolic shift toward anaerobic ATP generation as the central protective mechanism.

Results

Renal Function

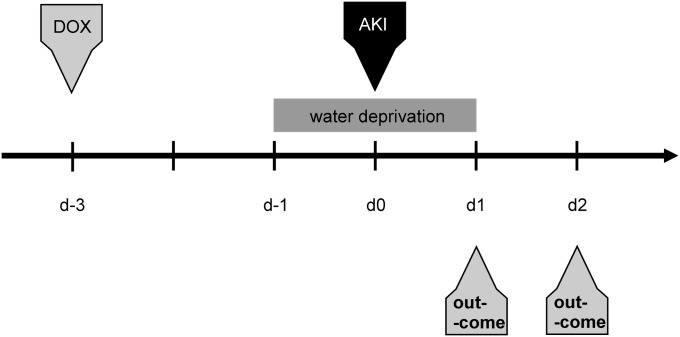

The protocol for animal treatment to activate HIF by VHL-KO and induce rhabdomyolysis-mediated AKI is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Protocol for AKI induction through rhabdomyolysis. AKI is induced under inhalation anesthesia by a single intramuscular injection of 50% glycerol into the left hind limb. Selective tubular HIF activation is induced by a single subcutaneous injection of doxycycline (DOX) 3 days before AKI induction. This time lag is necessary for establishment of maximum HIF activation via Pax8-rtTA–based knockout of VHL.

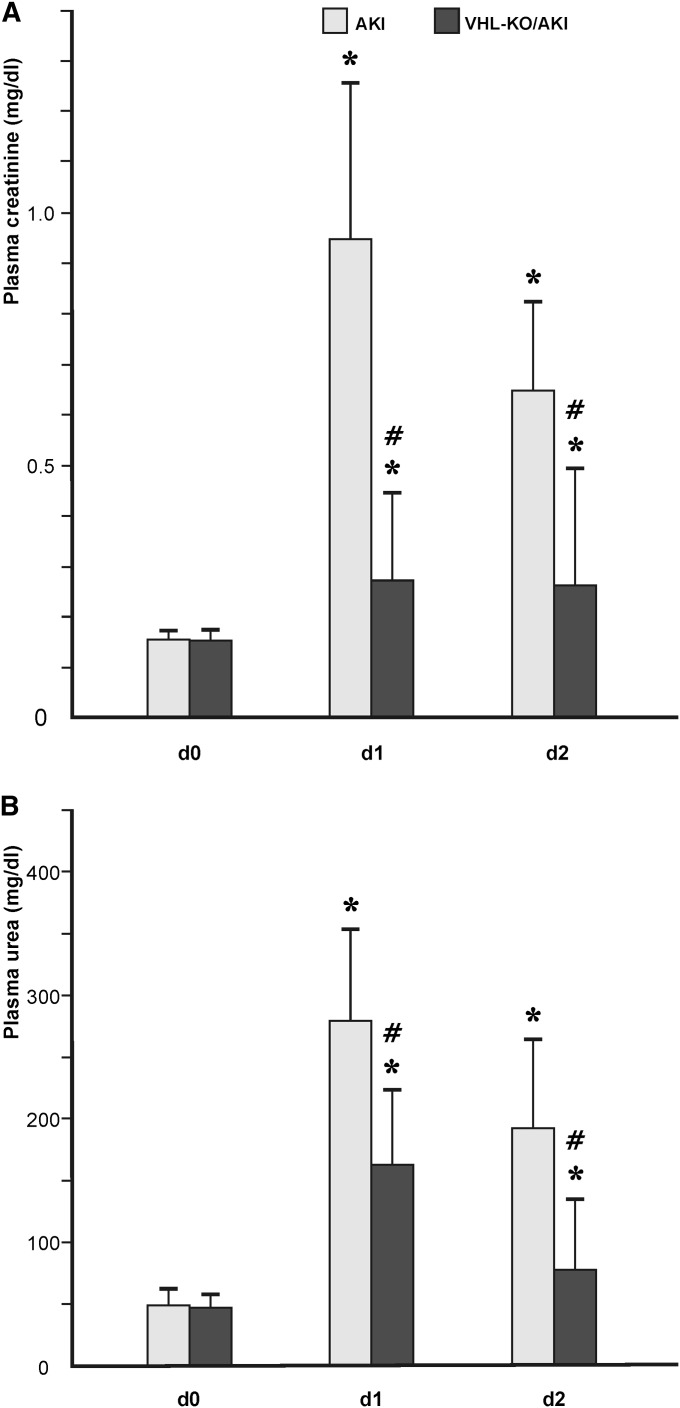

Neither VHL-KO per se nor withdrawal of drinking water had any effect on renal function or histology in otherwise untreated animals (not shown). At day 0, AKI and VHL-KO/AKI animals had comparable serum creatinine of approximately 0.18 mg/dl−1 (Figure 2A), as well as serum urea of approximately 50 mg/dl−1 (Figure 2B). Compared with day 0, AKI mice had significantly higher serum creatinine (0.93 mg/dl−1) and serum urea (283 mg/dl−1) at day 1. At day 2, both parameters were lower than at day 1 (serum creatinine, 0.65 mg/dl−1; serum urea, 190 mg/dl−1), although not statistically significant, but significantly higher than at day 0 (Figure 2). VHL-KO/AKI mice exhibited a similar time course of serum creatinine and urea. However, values were significantly lower than in the AKI group at both day 1 (serum creatinine, 0.28 mg/dl−1; serum urea, 166 mg/dl−1) and day 2 (serum creatinine, 0.25 mg/dl−1; serum urea, 78 mg/dl−1; Figure 2), reflecting functional protection.

Figure 2.

Tubular VHL knockout improves renal function during AKI. Both serum creatinine (A) and urea (B) are augmented at day 1 after induction of AKI. At day 2, both parameters decline, but are still elevated with respect to baseline. Animals with transgenic HIF activation in all renal tubules (VHL-KO/AKI, compare Figure 7B) exhibit less pronounced elevations of serum creatinine/urea than their littermates with scant and exclusively distal tubular HIF (AKI, compare Figure 7A). *P<0.05 versus control; #P<0.05 versus AKI.

Renal Morphology

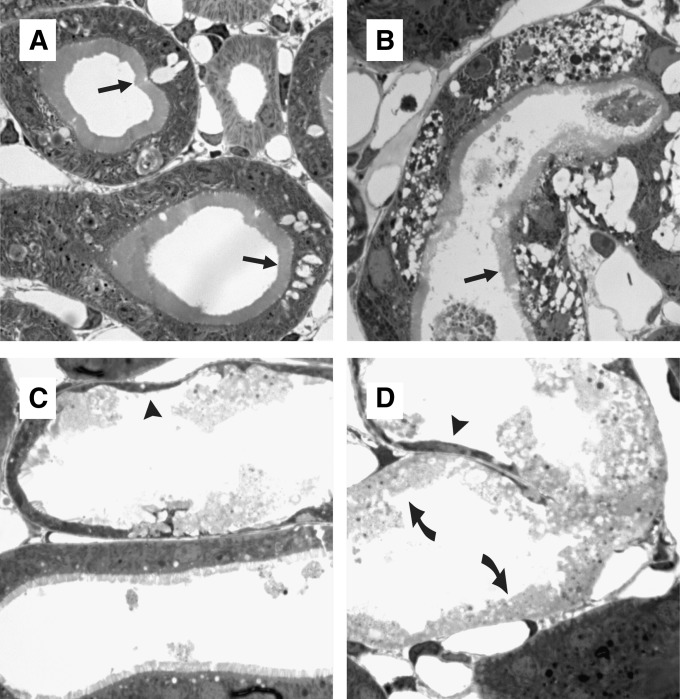

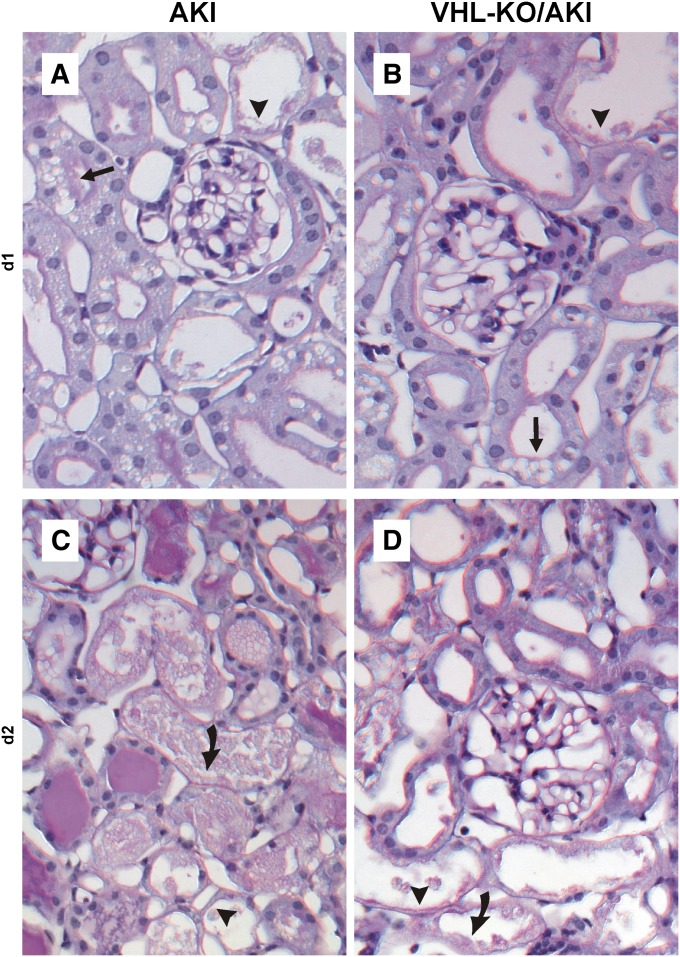

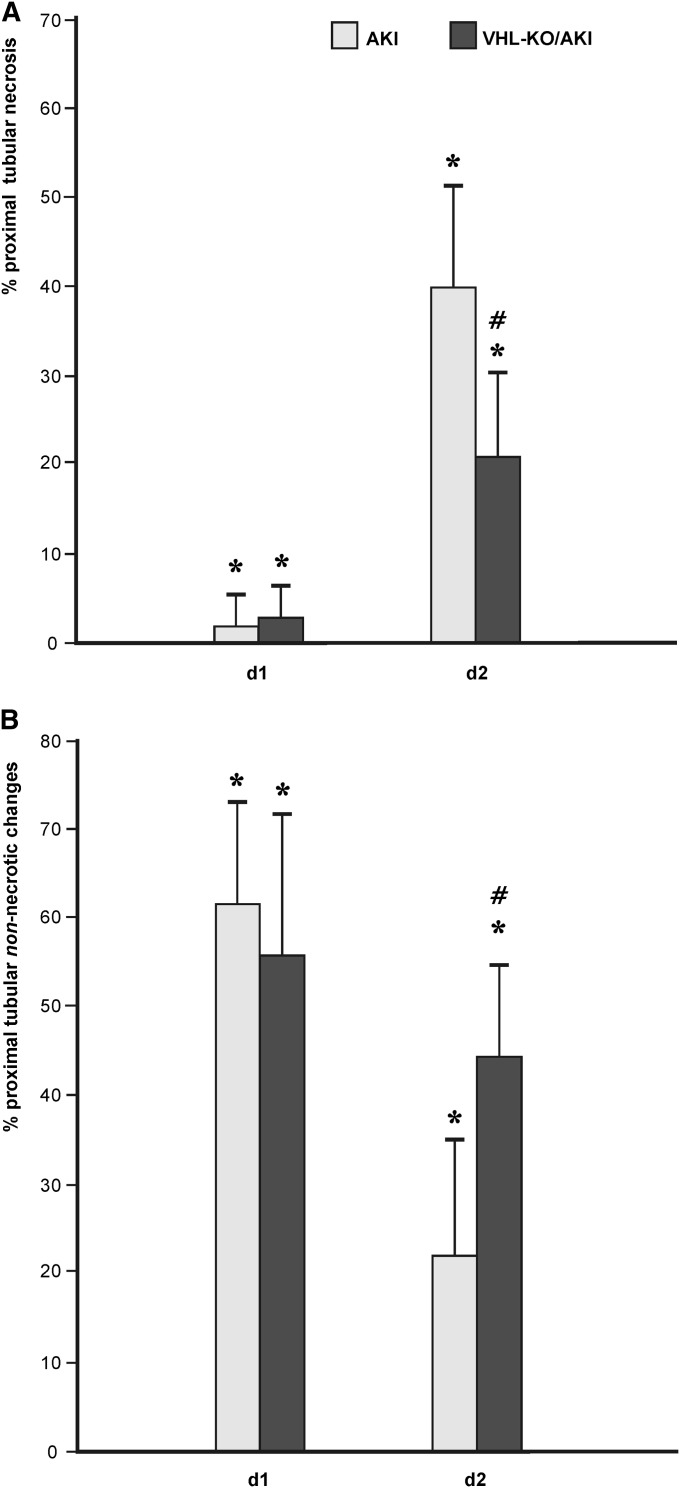

AKI principally provoked three forms of injury in proximal tubules, as found in 0.5-μm semithin sections: vacuoles (arrows in Figure 3, A and B), cytoplasmic thinning (arrowheads in Figure 3, C and D), and tubular necrosis (curved arrows in Figure 3D). To reduce sampling error, time course and semiquantification of injury were performed in paraffin sections stained with periodic acid–Schiff, in which the major injury categories were detected equally reliable as in semithin sections. Injury progressed over time, with necrosis being rare at day 1 but prominent at day 2 (Figure 4, A and C). Visual inspection revealed that necrosis was less pronounced in VHL-KO/AKI compared with AKI (Figure 4, B and D). For semiquantification, non-necrotic changes, namely vacuoles and flattening, were counted together, as opposed to tubular necrosis. At day 1, no significant histologic difference was seen between AKI and VHL-KO/AKI (Figure 5). Necrosis appeared in <5% of proximal convoluted tubules (Figure 5A), but roughly 55% of these were remarkable for non-necrotic damage (Figure 5B). By contrast, AKI and VHL-KO/AKI differed significantly in the extent of necrosis (40% versus 20%; Figure 5A) and non-necrotic changes (20% versus 45%; Figure 5B) at day 2, suggesting morphologic protection by the knockout.

Figure 3.

Tubular injury forms in rhabdomyolysis-induced AKI. Semithin plastic sections (0.5 μm). Arrow indicates vacuoles, arrowhead indicates cytoplasmic thinning, and curved arrow indicates necrosis. Tubular injury mainly affects proximal convoluted tubules. (A and B) Clear-cut, but non-necrotic, damage may occur under largely preserved brush border (arrows). (C) Largely normal and severely damaged tubules may occur side by side. (D) Different types of injury may coexist within the same tubular profile. Original magnification, ×1200.

Figure 4.

Tubular VHL knockout improves renal morphology during AKI. Paraffin sections (2 μm) stained with periodic acid–Schiff. Arrow indicates vacuoles, arrowhead indicates cytoplasmic thinning, and curved arrow indicates necrosis. Necrosis is rare at day 1 and is similar in AKI (A) and VHL-KO/AKI (B). By contrast, tubular necrosis is prominent at day 2, and is more extensive in AKI (C) than in VHL-KO/AKI (D). Original magnification, ×400.

Figure 5.

Semiquantification of injury in proximal tubules during AKI. At day 1 after AKI, induction tubular injury is mainly non-necrotic, and of similar extent in VHL-KO/AKI animals, which have marked HIF activation in all nephron segments (compare Figure 7B), as well as in AKI mice, which exhibit only scant HIF activation, and exclusively in largely unremarkable distal tubules (compare Figure 7A). By contrast, at day 2 after the onset of AKI, approximately 40% of proximal tubules are necrotic in AKI, and VHL-KO reduces this amount to 20%. *P<0.05 versus control; #P<0.05 versus AKI.

Apoptosis Marker Caspase-3

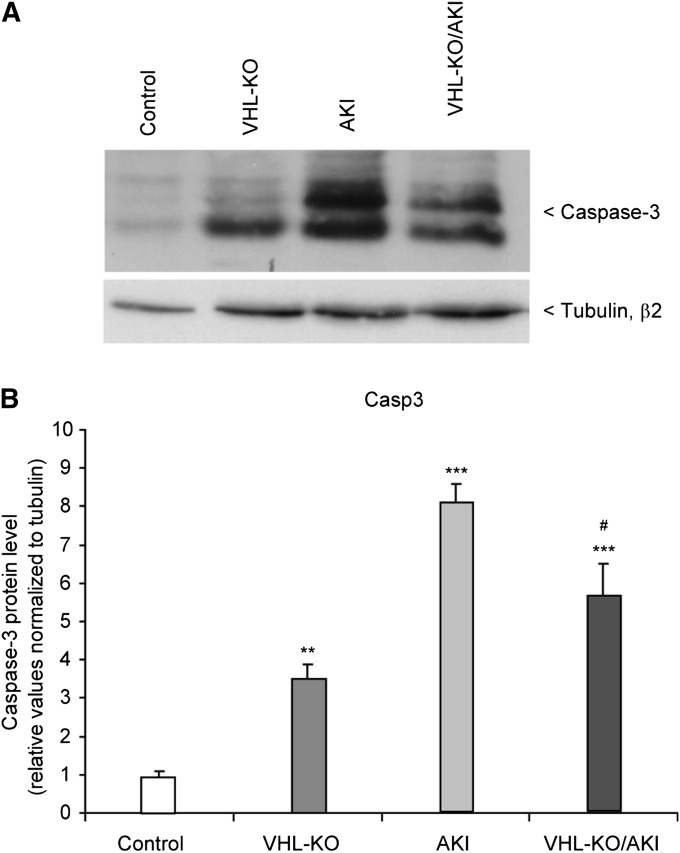

Apoptotic nuclei were rare in all four experimental groups (not shown). However, the apoptotic marker caspase-3 showed significant differences when measured by Western blot analysis (Figure 6). Both rhabdomyolysis groups had higher levels than controls or VHL-KO, respectively. In VHL-KO, caspase-3 levels were approximately 3-fold higher than in controls despite a similar histologic appearance. At day 1 after rhabdomyolysis, this relationship was inversed, with VHL-KO/AKI featuring significantly lower caspase-3 protein than AKI, suggesting that VHL-KO may have opposing effects depending on the underlying condition.

Figure 6.

Tubular VHL knockout reduces caspase-3 during AKI. (A) Representative original Western blot of caspase-3 protein in mouse kidneys. Untreated controls are compared with VHL-KO, rhabdomyolysis-induced AKI, and VHL-KO/AKI. (B) Statistical analyses. n=5 per experimental group. #P<0.05 versus AKI; **P <0.01 versus control; ***P<0.001 versus control.

Cellular Location of HIF-α

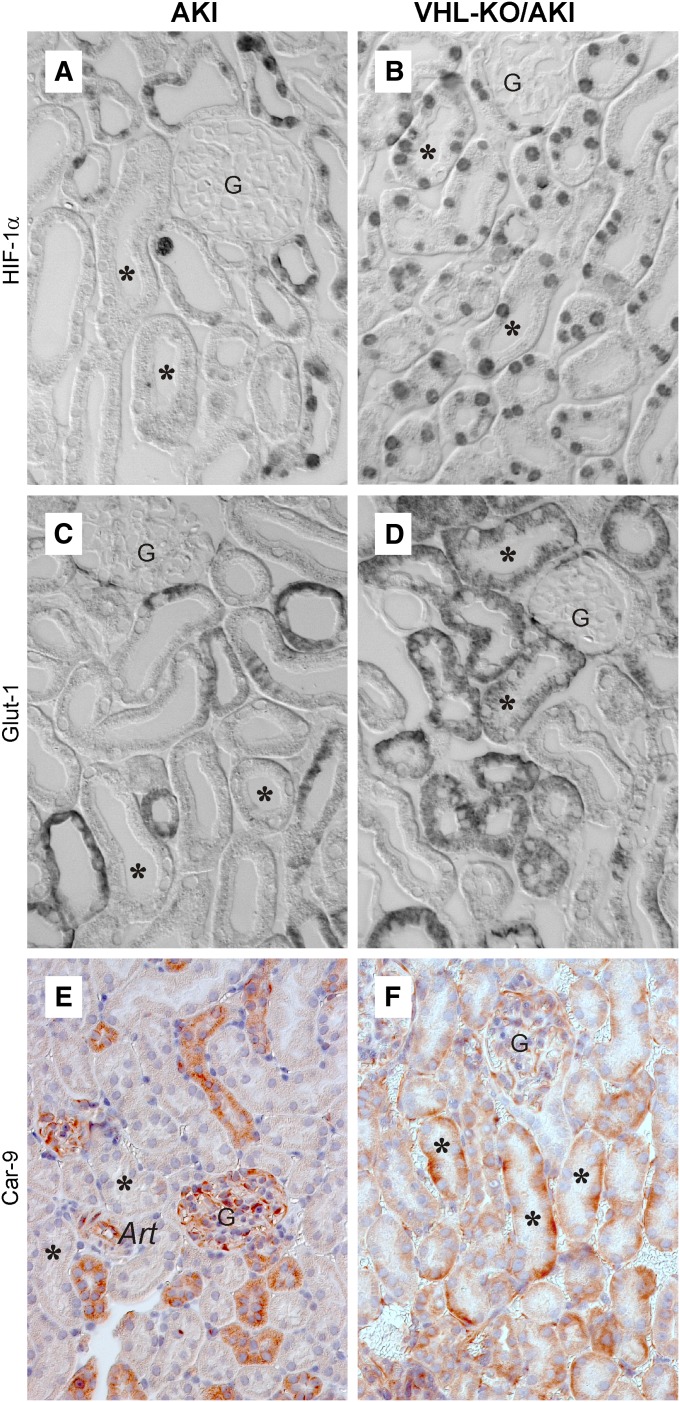

We performed immunohistochemistry for HIF-1α and HIF-2α to test for activation of HIF (Figure 7, A and B, and Tables 1 and 2). As previously shown,34 no signals were detectable in controls but appeared in all nephron segments in VHL-KO, with HIF-1α being more abundant than HIF-2α. AKI per se featured no HIF-2α staining (Table 2) but prominent HIF-1α immunosignals with increasing abundance from cortex to papilla, which is in line with known oxygen gradients,35–37 suggesting hypoxic HIF activation (Table 1). Proximal tubules (asterisks in Figure 7A), the nephron segment most prone to injury in this model, had no detectable HIF-α, suggesting defective hypoxia adaptation. By contrast, proximal tubules exhibited prominent HIF-1α in VHL-KO/AKI (asterisks in Figure 7B) as did the remainder of nephron segments. Staining patterns were similar for days 1 and 2, except for some background in necrotic areas (not shown). HIF-2α was undetectable in VHL-KO/AKI.

Figure 7.

VHL knockout induces HIF-1α and the HIF target genes Glut-1 and Car-9 in tubules at risk for injury. Immunohistochemistry at day 1 after induction of AKI. At this time point, histologic injury is mainly of the non-necrotic type and is comparable in AKI and VHL-KO/AKI (compare Figure 5). AKI features HIF-1α (A), Glut-1 (C), and Car-9 (E) in distal but not in proximal tubules. By contrast, VHL-KO/AKI reveals all three immunosignals in proximal tubules (asterisks in B, D, and F). Art, arteriole; asterisk, proximal tubule; G, glomerulus. Original magnification, ×400 in A–D; ×250 in E and F.

Table 1.

HIF-1α immunoreactivity at day 1 after AKI

| Renal Zone | Cell Type | Controla | AKIb | VHL-KOc | VHL-KO/AKId |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortex, labyrinth | Proximal convoluted tubule | — | + | +++ | ++ |

| Thick ascending limb | — | ++ | +++ | +++ | |

| Distal convoluted tubule | — | — | +++ | +++ | |

| Connecting tubule | — | — | +++ | +++ | |

| Tubular-interstitial cell | — | — | — | — | |

| Cortex, medullary ray | Proximal tubule (S3) | — | + | +++ | ++ |

| Thick ascending limb | — | ++ | +++ | +++ | |

| Collecting duct | — | ++ | +++ | +++ | |

| Tubular-interstitial cell | — | — | — | — | |

| Outer stripe of outer medulla | Proximal tubule (S3) | — | — | +++ | ++ |

| Collecting duct | — | + | +++ | +++ | |

| Thick ascending limb | — | ++ | +++ | +++ | |

| Tubular-interstitial cell | — | — | — | — | |

| Inner stripe of outer medulla | Thick ascending limb | — | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Thin limb | — | + | +++ | +++ | |

| Collecting duct | — | ++ | +++ | +++ | |

| Tubular-interstitial cell | — | + | — | ++ | |

| Inner medulla and papilla | Collecting duct | — | ++ | +++ | +++ |

| Thin limb | — | + | +++ | +++ | |

| Tubular-interstitial cell | — | + | — | — |

Untreated animals.

Intramuscular glycerol injection at day 0.

Subcutaenous doxycycline injection at day 3, which activates HIF in all nephron segments.

Combination of Intramuscular glycerol injection at day 0 and subcutaneous doxycycline injection at day 3.

Table 2.

HIF-2α immunoreactivity at day 1 after AKI

| Renal Zone | Cell Type | Controla | AKIb | VHL-KOc | VHL-KO/AKId |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cortex, labyrinth | Proximal convoluted tubule | — | — | ++ | — |

| Thick ascending limb | — | — | ++ | — | |

| Distal convoluted tubule | — | — | ++ | — | |

| Connecting tubule | — | — | ++ | — | |

| Tubular-interstitial cell | — | — | — | — | |

| Cortex, medullary ray | Proximal tubule (S3) | — | — | ++ | — |

| Thick ascending limb | — | — | ++ | — | |

| Collecting duct | — | — | ++ | — | |

| Tubular-interstitial cell | — | — | — | — | |

| Outer stripe of outer medulla | Proximal tubule (S3) | — | — | ++ | — |

| Collecting duct | — | — | ++ | — | |

| Thick ascending limb | — | — | ++ | — | |

| Tubular-interstitial cell | — | — | — | — | |

| Inner stripe of outer medulla | Thick ascending limb | — | — | + | — |

| Thin limb | — | — | + | — | |

| Collecting duct | — | — | + | — | |

| Tubular-interstitial cell | — | — | — | — | |

| Inner medulla and papilla | Collecting duct | — | — | + | — |

| Thin limb | — | — | + | — | |

| Tubular-interstitial cell | — | — | — | — |

Untreated animals.

Intramuscular glycerol injection at day 0.

Subcutaneous doxycycline injection at day 3, which activates HIF in all nephron segments.

Combination of intramuscular glycerol injection at day 0 and subcutaneous doxycycline injection at day 3.

Genome-Wide Analyses

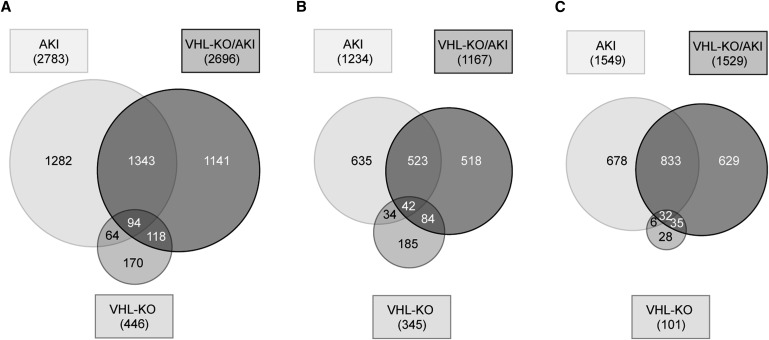

To gain an overview on the extent of gene regulation in the three interventional groups with respect to controls, we tested for the following: (1) present genes in controls (13,148 of 25,254 tested); (2) regulated genes (446 in VHL-KO, 2783 in AKI, and 2696 in VHL-KO/AKI) (Figure 8A); (3) upregulated genes (345 in VHL-KO, 1234 in AKI, and 1167 in VHL-KO/AKI) (Figure 8B); and (4) downregulated genes (101 in VHL-KO, 1549 in AKI, and 1529 in VHL-KO/AKI) (Figure 8C). Thus, AKI regulated approximately 20% of the active genome, and more than half of AKI-regulated genes were downregulated. Almost half of the genes regulated in VHL-KO/AKI were neither regulated by AKI nor by VHL-KO, suggesting that the combination of the two led to a unique transcriptome.

Figure 8.

Tubular VHL knockout leads to a largely novel transcriptome during AKI. Venn diagram illustrating the number of significantly regulated candidates (P<0.01) in VHL-KO, AKI, or VHL-KO/AKI relative to controls, respectively (A). Separate illustration of upregulated (B) and downregulated candidates (C).

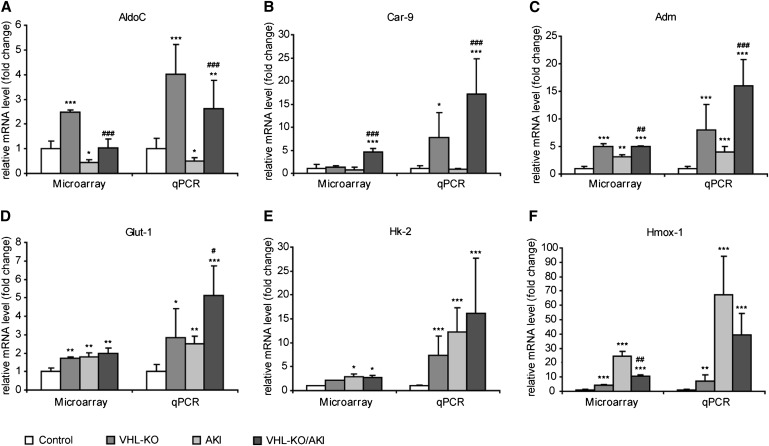

We performed real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) and detected typical HIF target genes to verify microarray data as well as functional HIF activation by VHL-KO (Figure 9). Selected candidates are involved in crucial protective pathways such as glycolysis (aldolase-C/fructose-bisphosphatase [AldoC] and hexokinase-2 [Hk2]),32,38 glucose uptake (solute carrier family 2 member 1 [Slc2a1 alias Glut-1]39), proton excretion (carbonic anhydrase-9 [Car-9]40), vasodilation (adrenomedullin, Adm41), and scavenging of free radicals (heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 [Hmox-1]42).

Figure 9.

Tubular VHL knockout upregulates HIF target genes with cell-protective potential. Microarray analysis and qPCR are shown side by side. AKI and VHL-KO/AKI are shown at day 1 after induction of injury. *P<0.05 versus control; **P<0.01 versus control; ***P<0.001 versus control; #P<0.05 versus AKI; ##P<0.01 versus AKI; ###P<0.001 versus AKI.

We found a good correlation between microarray and qPCR data. All tested HIF target genes were elevated at the transcript level by VHL-KO as determined by qPCR. By contrast, in rhabdomyolysis the HIF target genes Car-9 and AldoC were unchanged, or even depressed with respect to untreated controls. This finding backs the hypothesis of insufficient HIF response despite of renal hypoxia during AKI.

Pathway Enrichment Analyses

In tumors, stable HIF activation is responsible for the Warburg effect.32 We hypothesized that key enzymes of anaerobic energy metabolism will be upregulated in kidneys of Pax8-rtTA–based VHL-KO mice. Indeed, pathway enrichment analysis revealed that compared with controls, the major effect of VHL-KO per se was activation of glycolysis and increased glucose utilization (Table 3). In AKI, the TNF-α/NF-κB pathway was the most significantly upregulated.

Table 3.

Functional enrichment analysis at day 1 after AKI (P<0.01)

| Group | Upregulated Pathwaysa | P | Downregulated Pathwaysa | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VHL-KO versus control | ||||

| No. of genesa | 326 | 93 | ||

| Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis | 2.47e-07 | Glutathione metabolism | 0.001 | |

| ErbB signaling pathway | 0.0002 | Metabolic pathways | 0.001 | |

| Renal cell carcinoma | 0.001 | Folate biosynthesis | 0.002 | |

| MAPK signaling pathway | 0.0002 | Metapathway biotransformation | 0.003 | |

| B cell receptor signaling pathway | 0.0003 | Drug metabolism/cytochrome P450 | 0.004 | |

| EGFR1 signaling pathway | 0.001 | Selenium | 0.01 | |

| Keap1-Nrf2 | 0.002 | Folic acid network | 0.01 | |

| VEGF signaling pathway | 0.02 | AA metabolism | 0.01 | |

| Delta-notch signaling pathway | 0.02 | Oxidative stress | 0.01 | |

| AKI versus control | ||||

| No. of genesa | 1107 | 1421 | ||

| TNF-α NF-κB signaling pathway | 2.91e-12 | Metabolic pathways | 1.58e-15 | |

| Proteasome degradation | 5.54e-10 | Oxidative phosphorylation | 9.30e-05 | |

| MAPK signaling pathway | 1.43e-09 | Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids | 0.0002 | |

| EGFR1 signaling pathway | 4.49e-09 | Nuclear receptors | 0.0003 | |

| Spliceosome | 9.29e-08 | Electron transport chain | 0.001 | |

| Translation factors | 1.00e-07 | Steroid biosynthesis | 0.002 | |

| FAS pathway; stress induction of HSP regulation | 1.55e-06 | Glycosphingolipid biosynthesis (globo series) | 0.004 | |

| Toll-like receptor signaling pathway | 3.16e-06 | PG synthesis and regulation | 0.01 | |

| Insulin signaling | 4.35e-06 | |||

| Endocytosis | 8.10e-06 | |||

| Diurnally regulated genes with circadian orthologs | 1.46e-05 | |||

| Circadian exercise | 1.46e-05 | |||

| Neurotrophin signaling pathway | 5.99e-05 | |||

| Tight junction | 0.001 | |||

| VHL-KO/AKI versus AKI | ||||

| No. of genesa | 476 | 210 | ||

| Glycolysis and gluconeogenesis | 1.66e-09 | Diurnally regulated genes with circadian orthologs | 8.44e-05 | |

| Statin pathway (PharmGKB) | 9.11e-05 | Adipogenesis | 0.001 | |

| Biotin metabolism | 0.001 | EGFR1 signaling pathway | 0.001 | |

| PPAR signaling pathway | 0.001 | Id signaling pathway | 0.0003 | |

| Glycogen metabolism | 0.01 | IL-1 signaling pathway | 0.001 | |

| Circadian exercise | 0.001 | |||

| MAPK signaling pathway | 0.001 | |||

| IL-2 signaling pathway | 0.002 |

MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; EGFR1, epidermal growth factor receptor 1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; FAS, TNF receptor superfamily member 6; HSP, heat shock protein; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor.

Threshold P value <0.01.

To prove our hypothesis that renal protection by VHL-KO is a shift toward oxygen-independent energy metabolism, we next compared rhabdomyolysis-induced AKI in knockout animals and controls (VHL-KO/AKI versus AKI). A total of 686 candidates were differentially regulated, 476 of which were upregulated and 210 were downregulated. Indeed, the most prominent difference between VHL-KO/AKI and AKI was an enrichment of factors involved in glycolysis. By contrast, stress response and energy-consuming processes were reduced (Table 3).

We further compared the biologic roles of the top 30 upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively. Among the top 30 upregulated genes, there were 9 acknowledged HIF target genes, suggesting a high level of HIF-based transactivation. Six of these HIF target genes collectively achieved a shift toward anaerobic ATP production (Table 4). The main biologic roles of the top 30 downregulated genes in VHL-KO/AKI versus AKI are shown in Table 5. Twelve of these were hypoxia-regulated markers of tissue injury, repair, or remodeling, which is in line with a less severe tissue injury.

Table 4.

VHL-KO/AKI versus AKI at day 1, top 30 upregulated (P<0.01)

| Gene | Symbol | Other Aliases | Fold Change | HIF Target Genea | Induced in VHL-KO | Induced by Hypoxib | RefSeq | Function/Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vomeronasal 1 receptor 32 | Vmn1r32 | 31.71 | Yes | NM_134170 | Neural signaling | |||

| Vomeronasal 1 receptor 34 | Vmn1r34 | 24.29 | Yes | NM_001166719 | Neural signaling | |||

| Vomeronasal 1 receptor 37 | Vmn1r37 | 10.29 | Yes | NM_134165 | Neural signaling | |||

| Chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 28 | Ccl28 | 8.29 | No | Yes | NM_020279 | Chemoattraction, Treg recruitment | ||

| Apoc-III | Apoc3 | 6.81 | Yes | NM_023114 | Lipid metabolism | |||

| Carbonic anhydrase 9 | Car9 | CA9 | 6.76 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NM_139305 | Ph regulation |

| IL 17 receptor B | Il17rb | 6.43 | Yes | NM_019583 | NF-κB pathway | |||

| EGL nine homolog 3 (Caenorhabditis elegans) | Egln3 | PHD3 | 6.37 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NM_028133 | Transcription |

| Apo A-IV | Apoa4 | 6.34 | No | NM_007468 | Lipid metabolism | |||

| Defensin β19 | Defb19 | 5.97 | No | NM_145157 | Immunity | |||

| Phosphofructokinase, liver, B type | Pfkl | AldoC | 4.70 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NM_008826 | Glycolysis |

| PRELI domain containing 2 | Prelid2 | 4.19 | Yes | NM_029942 | Development | |||

| Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isoenzyme 1 | Pdk1 | 4.13 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NM_172665 | Krebs cycle inhibition | |

| Solute carrier family 16 (monocarboxylic acid transporters) | Slc16a3 | 4.02 | Yes | Yes | NM_001038653 | Lactic acid and pyruvate transport | ||

| Cytochrome P450, family 4, subfamily a, polypeptide 14 | Cyp4a14 | 3.84 | No | NM_007822 | AA metabolism, 20-HETE | |||

| 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 2 | Hmgcs2 | 3.78 | No | NM_008256 | Ketogenesis | |||

| Angiopoietin-like 3 | Angptl3 | ANGPT5 | 3.41 | Yes | NM_013913 | Angiogenesis | ||

| BCL2/adenovirus E1B interacting protein 3 | Bnip3 | NIP3 | 3.25 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NM_009760 | Autophagy |

| Endothelin 3 | Edn3 | ET-3 | 3.12 | Yes | NM_007903 | Development | ||

| Lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus F | Ly6f | 2.97 | No | NM_008530 | Unknown | |||

| Aldo-keto reductase family 1, member C18 | Akr1c18 | 2.96 | No | NM_134066 | Steroid metabolism | |||

| Vomeronasal 1 receptor 20 | Vmn1r20 | 2.87 | No | NM_001101533 | Unknown | |||

| IGF binding protein 1 | Igfbp1 | 2.85 | Yes | No | Yes | NM_008341 | Insulin resistance | |

| Adrenomedullin 2 | Adm2 | 2.62 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NM_182928 | Decreased endothelial permeability | |

| Phosphofructokinase, platelet | Pfkp | AldoC | 2.54 | Yes | Yes | Yes | NM_019703 | Glycolysis |

| Hormonally upregulated Neu-associated kinase | Hunk | 2.54 | No | NM_015755 | Constitutive in distal tubules; inhibits angiotensin II effect | |||

| Potassium inwardly-rectifying channel, subfamily J, 1 | Kcnj1 | 2.49 | No | NM_001168354 | Mutation leads to Bartter syndrome | |||

| Flavin containing monooxygenase 5 | Fmo5 | 2.45 | No | NM_001161765 | NADPH dependent | |||

| Solute carrier family 23 (nucleobase transporters), 3 | Slc23a3 | 2.42 | No | NM_194333 | Orphan transporter | |||

| Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1, cytosolic | Pck1 | PEPCK | 2.39 | Yes | No | Yes | NM_011044 | Gluconeogenesis |

Treg, regulatory T cell; 20-HETE, 20-hydroxyeicosatetraeonic acid.

HIF target genes: empty spaces are left for candidates without solid evidence for HIF-dependent regulation.

Genes regulated by hypoxia: empty spaces are left for candidates without solid evidence for hypoxia-dependent regulation.

Table 5.

VHL-KO/AKI versus AKI at day 1, top 30 downregulated (P<0.01)

| Gene | Symbol | Other Aliases | Fold Change | HIF Target Genea | Reduced in VHL-KO | Induced by Hypoxiab | RefSeq | Function/Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G protein-coupled receptor, family C, group 5, member A | Gprc5a | 0.31 | No | NM_181444 | Retinoic acid–dependent tumor suppressor | |||

| Growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible 45α | Gadd45a | 0.33 | No | Yes | NM_007836 | Cell cycle, DNA repair, tumor suppressor | ||

| Growth differentiation factor 15 | Gdf15 | PTGFB | 0.34 | No | Yes | NM_011819 | Angiogenesis, transcription, activates HIF | |

| Early growth response 1 | Egr1 | 0.38 | No | Yes | NM_007913 | HIF cotranscription factor | ||

| Polo-like kinase 3 (Drosophila) | Plk3 | 0.39 | No | Yes | NM_013807 | Tumor suppressor, phosphorylates HIF | ||

| NADH dehydrogenase subunit 6 | ND6 | 0.40 | No | NC_005089 | Mitochondrial gene of complex I, HIF-1α transcription | |||

| Stratifin | Sfn | YWHAS | 0.40 | No | NM_018754 | Matrix turnover | ||

| Dual specificity phosphatase 5 | Dusp5 | 0.43 | No | NM_001085390 | Dephosphorylate both tyrosine and serine/threonine residues | |||

| PG-endoperoxide synthase 2 | Ptgs2 | COX2 | 0.44 | Yes | No | Yes | NM_011198 | PG synthesis, activates HIF |

| Cysteine-rich protein 61 | Cyr61 | 0.44 | Yes | No | Yes | NM_010516 | Angiogenesis | |

| Tumor-associated calcium signal transducer 2 | Tacstd2 | 0.44 | No | NM_020047 | Membrane receptor | |||

| Rho family GTPase 3 | Rnd3 | 0.44 | Yes | No | Yes | NM_028810 | Cytoskeleton, epithelial-mesenchymal transdifferentiation | |

| Eph receptor A2 | Epha2 | 0.45 | Yes | No | Yes | NM_010139 | Development | |

| Transmembrane protein 108 | Tmem108 | 0.47 | No | NM_178638 | Lipid metabolism | |||

| Coagulation factor III | F3 | TF | 0.48 | No | Yes | NM_010171 | Coagulation | |

| IFN-related developmental regulator 1 | Ifrd1 | 0.48 | No | Yes | NM_013562 | Transcription | ||

| Pleckstrin homology-like domain, family A, member 1 | Phlda1 | 0.48 | No | NM_009344 | Apoptosis | |||

| Cholesterol 25-hydroxylase | Ch25h | 0.48 | No | NM_009890 | Lipid metabolism | |||

| Choline kinase α | Chka | 0.48 | Yes | No | Yes | NM_013490 | Biosynthesis of phosphatidylcholine | |

| fos-like antigen 1 | Fosl1 | 0.50 | No | Yes | NM_010235 | Transcription | ||

| Dual specificity phosphatase 14 | Dusp14 | 0.51 | No | Yes | NM_019819 | Dephosphorylate both tyrosine and serine/threonine residues | ||

| Retinoblastoma binding protein 6 | Rbbp6 | 0.51 | No | NM_011247 | Cell cycle | |||

| Transgelin | Tagln | 0.52 | No | NM_011526 | Cytoskeleton, shape change | |||

| Jun oncogene | Jun | AP-1 | 0.53 | No | Yes | NM_010591 | HIF cotranscription factor | |

| Transmembrane protein 171 | Tmem171 | 0.53 | No | NM_001025606 | Urate transport? | |||

| Thioredoxin reductase 1 | Txnrd1 | 0.54 | No | NM_001042523 | ROS scavenging, downregulated in hypoxia | |||

| Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 | Socs3 | 0.55 | No | Yes | NM_007707 | Modulation of cytokine signaling | ||

| Nestin | Nes | 0.55 | No | Yes | NM_016701 | Angiogenesis | ||

| Keratin 18 | Krt18 | 0.56 | No | NM_010664 | Cancer | |||

| Dual specificity phosphatase 8 | Dusp8 | 0.56 | No | Yes | NM_008748 | Dephosphorylates tyrosine and serine/threonine residues |

ROS, reactive oxygen species.

HIF target genes: empty spaces are left for candidates without solid evidence for HIF-dependent regulation.

Genes regulated by hypoxia: empty spaces are left for candidates without solid evidence for hypoxia-dependent regulation.

Location of HIF Target Genes in Tubules at Risk

To test whether HIF activation was accompanied by target gene transactivation in proximal tubules, we performed immunohistochemistry for the cell-protective HIF-1α target genes Glut-1 and Car-9. The cellular location of the latter has not been determined in the kidney thus far. As a positive control, we used paraffin-embedded mouse stomach, in which Car-9 is constitutively expressed.43 Membranous signals indeed appeared in epithelial cells of the corpus with virtually no background (Supplemental Figure 1). In AKI, both Glut-1 and Car-9 (Figure 7, C and E) matched the staining pattern of controls (not shown). Signal distribution in VHL-KO/AKI (Figure 7, D and F) was largely equivalent to that observed in VHL-KO (not shown). Moreover, both Glut-1 and Car-9 appeared in distal but not in proximal tubules (asterisks in Figure 7, C and E). By contrast, VHL-KO/AKI featured de novo expression in the basolateral membranes and adjacent cytoplasm of proximal convoluted tubules (asterisks in Figure 7D for Glut-1, and in Figure 7F for Car-9). Additional extratubular and constitutive expression was noted in glomeruli (Figure 7, C and E) including Glut-1 in Bowman’s capsule and Car-9 in various cell types, which most likely include mesangial and endothelial cells. Moreover, constitutive Car-9 was expressed in endothelial cells and in myocytes of arterioles (Figure 7E).

Discussion

Here we demonstrate protection against rhabdomyolysis-induced AKI by preconditional knockout of VHL. The latter is closely associated with a metabolic shift toward anaerobic ATP production.

Experimental rhabdomyolysis is intimately related to the human syndrome.9 Our finding of nuclear HIF-1α protein accumulation in the largely unremarkable distal tubules, but not in the injured proximal tubules, indicates hypoxia with insufficient adaptation. Pax8-rtTA–based VHL-KO achieves selective and inducible HIF activation in the entire nephron, and significantly reduces serum creatinine/urea as well as tubular necrosis at day 2 after the onset of rhabdomyolysis.

Upregulation of several cell-protective HIF target genes suggests that the effect of VHL-KO is conferred through HIF. It is important to recognize that target gene specificity of the two major HIFα isoforms varies with respect to cell type and underlying condition.44,45 Presumably, the setting in our VHL-KO mice is more or less matched by that of renal cell carcinoma cells with constitutive deletion of VHL,44 in which Car-9 and Bnip3 are regulated by HIF-1α, whereas cyclin D1 and Glut-1 are regulated by HIF-2α. Furthermore, erythropoietin was shown to be a HIF-2α target gene.45 Our microarray analysis and qPCR suggest that renal protection was mainly conferred through HIF-1.

The observation that tubular changes are mainly sublethal 24 hours after the onset of rhabdomyolysis is in line with the limited tubular injury seen in human AKI.3,46 Such potentially reversible injury opens a window of opportunity for renal protection. Our study focuses on this time span of already detectable and progressive pathology, which precedes necrosis by roughly 1 day. We hypothesized that the transcriptome would allow detection of HIF-related renal-protective mechanisms at this stage.

This study aimed to separately assess the transcriptome in VHL-KO, AKI, and their combination. AKI per se has a deep effect on gene regulation, affecting nearly 20% of the active genome. VHL-KO per se, which was previously shown to produce no major renal pathology,34 regulates approximately 3% of the active genome. Interestingly, VHL-KO superimposed on AKI causes a unique HIF transcriptome. Thus, of 1167 upregulated genes in VHL-KO/AKI (Figure 8B), 518 were neither shared with AKI nor with VHL-KO per se. Epigenetics may explain this phenomenon, at least in part. The balance between histone acetylases and demethylases is altered by hypoxia; hence, new HREs may become accessible for HIF in AKI.47,48

The number of acknowledged HIF target genes exceeds 350,31 giving rise to a myriad of possible biologic effects. Thus far, no study has systematically investigated the genome under HIF activation and established AKI. Our study shows a significant association between renal protection and a shift of energy metabolism. We provide evidence for a HIF-orchestrated program that comprises increased cellular glucose uptake and utilization, autophagy, gluconeogenesis, glycolysis, proton removal, vasodilation, as well as decreased fatty acid utilization and aerobe ATP production. Under oxygen shortage, it is biochemically advantageous to reduce oxygen-dependent ATP production, and to expand oxygen-independent, although less efficient, glycolysis.32,49 To match increased glucose consumption, at least two mechanisms are intensified: uptake from the environment and gluconeogenesis. As a major drawback, glycolysis may lead to acidosis unless powerful proton excretion devices are provided. De novo expression of Car-9 in the basolateral membrane of proximal tubules indicates that proton excretion via the blood stream may be part of the HIF-mediated rescue mechanism.

Mitochondria may become sources of apoptosis and necrosis signals in hypoxia.50 In this context autophagy can help to remove damaged and potentially harmful mitochondria,51 and at the same time provide new substrates for glycolysis. Bnip3, one of the top 30 upregulated genes in VHL-KO/AKI versus AKI (Table 4), promotes either apoptosis or autophagy, the latter being largely specific for mitochondria.52 Although microarray analysis revealed enhanced Bnip3 in VHL-KO versus controls, as well as in VHL-KO/AKI versus AKI, the apoptosis marker Casp-3 was increased in the former but decreased in the latter (Figure 6). It is tempting to assume that Bnip3 action depends on the underlying condition, promoting apoptosis in normoxia but repressing it under hypoxic conditions. In the setting of VHL-KO/AKI, additional HIF-dependent factors may repress apoptosis, as recently demonstrated for the glycolytic key enzyme Hk-2.53

Of note, the TNF/NF-κB pathway was the most significantly upregulated during AKI, and VHL-KO/AKI significantly reduced the inflammatory transcripts TNF-1α, TNF-1β, IL-1β, and IL-6, as assessed by microarray analysis. Whether this is a direct effect of VHL-KO/HIF activation, or a consequence of reduced tubular necrosis, requires further investigation.

Our data strongly suggest that proximal tubules overexpressing HIF are protected from acute injury. However, Schley et al.54 showed that selective VHL deletion in thick ascending limbs ameliorates ischemic proximal tubular damage. Although the mechanisms responsible for such remote protection of proximal tubules remain elusive, they may operate in Pax8-rtTA–based VHL-KO mice as well. Our data do not exclude that extratubular or HIF-independent mechanisms have the potential to ameliorate AKI. Recent studies indicate that blood-borne infiltrating cells play an important role in kidney protection.55,56 In rhabdomyolysis, the cell-protective enzyme Hmox-1 is upregulated in renal proximal tubules16,57 in the absence of HIF.16

In conclusion, a genome-wide search for potentially renal-protective genes in early stages after the onset of AKI provides strong evidence for a metabolic shift toward anaerobic energy metabolism in tubules at risk as the main mechanism of renal protection through VHL knockout.

Concise Methods

Animals

Mice of both sexes (24–31 g body weight) were fed a standard rodent chow with 19% protein content (V1534/300; Ssniff, Soest, Germany) and had free access to drinking water unless otherwise specified. Up to five mice were housed per cage in 12-hour day and night cycles. All experiments were carried out in transgenic mice in which selective renal tubular VHL-KO was inducible by doxycycline.34 Animal care and treatment were in conformity with the guidelines of the American Physiologic Society, and were also approved by the Berlin Senate (G0014/07).

Experimental Protocols

Four groups of animals were used: (1) controls, n=10 untreated mice; (2) VHL-KO, n=10 injected with doxycycline (0.1 mg per 10 g body weight subcutaneously) 4 days before euthanasia; (3) AKI, n=24 with rhabdomyolysis; and (4) VHL-KO/AKI, n=24 with rhabdomyolysis injected with doxycycline (Figure 1). To induce AKI, 50% glycerol (0.05 ml per 10 g body weight) was injected intramuscularly into the left hind limb under inhalation narcosis. Drinking water was withdrawn between 20 hours before and 24 hours after glycerol injection. Before glycerol injection and at either 24 hours or 48 hours thereafter, animals had blood collections from the facial vein58 for creatinine and urea, which were determined using a Roche Cobas modular PPP-800. The kidneys were then harvested.

Organ Harvesting and Fixation

For each condition, half of the animals had their kidneys fixed by perfusion under deep pentobarbital anesthesia.59 The other half had their kidneys harvested after cervical dislocation under inhalation anesthesia, and either fixed by immersion or processed for homogenization. The fixation protocol included 3% paraformaldehyde and 1.5% glutaraldehyde/1.5% paraformaldehyde postfixation for semithin analysis and electron microscopy. Solutions were buffered with Na-cacodylate buffer.59 After fixation, specimens were transferred to 330 mOsmol/L−1 sucrose in PBS with 0.02% sodium azide. Later, specimens were further prepared and either embedded in paraffin or Epon and sectioned according to a standard protocol.59 Tissue homogenates were performed from transversally sectioned fresh kidney halves that were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen immediately thereafter.

Morphologic Studies

Rhabdomyolysis leads to injury mainly in proximal tubules.60 Three categories of acute tubular injury were defined in 0.5-μm semithin sections, but were equally detectable in 2-μm paraffin sections stained with periodic acid–Schiff, which served for semiquantitative scoring. Each proximal tubular profile was assigned to one of the following categories on the basis of the highest grade injury: 0, unremarkable (any changes not fitting into the subsequent categories); I, vacuoles of more than half of a nuclear diameter; II, flattening with tubular cytoplasmic height (excluding brush border) of less than half of normal; and III, necrosis. Proximal tubular injury in the cortex was semiquantitatively assessed by point counting at ×400 magnification using a grid. At least 200 proximal tubular profiles were counted per animal.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on paraffin sections as previously described.25 The following primary antisera were used: rabbit anti-human HIF-1α (#10006421, 1:30,000; Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), rabbit anti-mouse HIF-2α (PM9, 1:12,500; gift from Patrick Maxwell, Imperial College, London, UK), rabbit anti-human glucose transporter-1 (Glut-1, #GT12-A, 1:10,000; Biotrend, Cologne, Germany), and rabbit anti-human carbonic anhydrase-9 (Car-9, #NB100–417, 1:10,000; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO). Semiquantitative scores for tubular HIF-1α and HIF-2α were performed by estimating three grades of histochemical signal: + was assigned to a proportion of less than one third of tubular profiles, ++ to one third to two thirds, and +++ to more than two thirds. For tubulointerstitial HIF-2α, + was assigned to a proportion of <5 signals per ×100 magnification field, ++ to 6–10, and +++ to >10. Light microscopy was performed with the help of a Leica DMRB fluorescence microscope equipped with an interference contrast module (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). Images were acquired using a SPOT RT 2.3.0 digital camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI) and the MetaVue imaging system (Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA).

Western Blot Analyses

To determine caspase-3 protein levels, extracts from kidneys were prepared as previously described.61 Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to Hybond-P membranes. Caspase-3 protein was detected using a specific antibody (#AM08377PU-N; Acris Antibodies GmbH, Herford, Germany) and secondary antibody goat-anti-mouse (#sc2031, dilution 1:100,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Detection of relative class IIb β-tubulin protein levels served as a loading control (primary antibody: anti-Tubb2B, #10063-2-AP, dilution 1:1000, Proteintech, Chicago, IL) (secondary antibody: donkey anti-rabbit, #sc2317, dilution 1:100,000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Microarray Analyses

Controls (n=3) were compared with VHL-KO (n=3), AKI at day 1 (n=5), and VHL-KO/AKI at day 1 (n=5). Total RNA from halved kidneys was isolated using RNA-Bee (AMS Biotechnology Ltd, Lake Forest, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA integrity was checked by analyzing on the 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). For global gene expression profile analysis, the Affymetrix Mouse Gene 1.0ST Array (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA) was used according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Arrays were processed at the Charité Genome Analysis Facility. Logarithm to the basis 2 (LOG2) levels of signal intensities were considered to be present when values were >6 in expressed genes. Data and relevant information can be accessed at the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number: GSE44925).

Functional Enrichment Analyses

Microarray data served for functional enrichment analysis using the Web-based Gene Set Analysis Toolkit (WebGestalt).62,63 Enrichment analysis of gene sets that were either significantly upregulated or downregulated in VHL-KO animals and/or AKI was performed based on the Gene Ontology, KEGG Pathway, and WikiPathways databases. To ensure high stringency, we selected groups according to a P value <0.01.

mRNA Quantification

RNA was isolated using RNA-Bee (AMS Biotechnology Europe Ltd) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and was reverse transcribed using Superscript and random hexamers (Invitrogen, Darmstadt, Germany). qPCR analysis was performed using SYBR Green master mix in a GeneAmp 5700 (Applied Biosystems). Two microliters of cDNA corresponding to 20 ng RNA served as a template. Primers were designed to bridge at least one intron. The primer sequences used for PCR amplification are presented in Supplemental Table 1. The following genes were tested: adrenomedullin (Adm; NM_009627.1), carbonic anhydrase 9 (Car-9, NM_139305.2), hexokinase-2 (Hk2, NM_013820.3), aldolase-C, fructose-bisphosphatase (AldoC, NM_009657.3), solute carrier family 2 (facilitated glucose transporter), member 1 (Slc2a1 [Glut-1], NM_011400.3), and heme oxygenase (decycling) 1 (Hmox-1, NM_010442.2). The expression levels were calculated according to the ΔCt-method with 18S rRNA as the reference gene. Parallelism of standard curves of the test and control was confirmed.

Statistical Analyses

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. At least six animals were analyzed in each experimental group, unless otherwise specified. Data were analyzed by the unpaired t test or Mann–Whitney U test where appropriate. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Kerstin Riskowsky, Petra Schrade, Jeannette Werner, and John Horn for their skillful assistance.

This study was supported by the German Research Foundation (FOR 1368, DFG).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2013030281/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM: Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 844–861, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoste EAJ, Schurgers M: Epidemiology of acute kidney injury: How big is the problem? Crit Care Med 36[Suppl]: S146–S151, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kellum JA: Acute kidney injury. Crit Care Med 36[Suppl]: S141–S145, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, Garg AX, Parikh CR: Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 961–973, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huerta-Alardín AL, Varon J, Marik PE: Bench-to-bedside review: Rhabdomyolysis — an overview for clinicians. Crit Care 9: 158–169, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malinoski DJ, Slater MS, Mullins RJ: Crush injury and rhabdomyolysis. Crit Care Clin 20: 171–192, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vanholder R, Sever MS, Erek E, Lameire N: Rhabdomyolysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1553–1561, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan FY: Rhabdomyolysis: A review of the literature. Neth J Med 67: 272–283, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oken DE: Acute renal failure (vasomotor nephropathy): Micropuncture studies of the pathogenetic mechanisms. Annu Rev Med 26: 307–319, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oken DE, Arce ML, Wilson DR: Glycerol-induced hemoglobinuric acute renal failure in the rat. I. Micropuncture study of the development of oliguria. J Clin Invest 45: 724–735, 1966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oken DE, DiBona GF, McDonald FD: Micropuncture studies of the recovery phase of myohemoglobinuric acute renal failure in the rat. J Clin Invest 49: 730–737, 1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayer G, Grandchamp A, Wyler T, Truniger B: Intrarenal hemodynamics in glycerol-induced myohemoglobinuric acute renal failure in the rat. Circ Res 29: 128–135, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu CH, Kurtz TW, Sands CE: Intrarenal vascular resistance in glycerol-induced acute renal failure in the rat. Circ Res 45: 583–587, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolfert AI, Oken DE: Glomerular hemodynamics in established glycerol-induced acute renal failure in the rat. J Clin Invest 84: 1967–1973, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milman Z, Heyman SN, Corchia N, Edrei Y, Axelrod JH, Rosenberger C, Tsarfati G, Abramovitch R: Hemodynamic response magnetic resonance imaging: Application for renal hemodynamic characterization. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 1150–1156, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberger C, Goldfarb M, Shina A, Bachmann S, Frei U, Eckardt KU, Schrader T, Rosen S, Heyman SN: Evidence for sustained renal hypoxia and transient hypoxia adaptation in experimental rhabdomyolysis-induced acute kidney injury. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 1135–1143, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flögel U, Merx MW, Gödecke A, Decking UK, Schrader J: Myoglobin: A scavenger of bioactive NO. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98: 735–740, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schaad O, Zhou HX, Szabo A, Eaton WA, Henry ER: Simulation of the kinetics of ligand binding to a protein by molecular dynamics: Geminate rebinding of nitric oxide to myoglobin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 90: 9547–9551, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holt S, Moore K: Pathogenesis of renal failure in rhabdomyolysis: The role of myoglobin. Exp Nephrol 8: 72–76, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nangaku M, Rosenberger C, Heyman SN, Eckardt KU: Regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor in kidney disease. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 40: 148–157, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gross MW, Karbach U, Groebe K, Franko AJ, Mueller-Klieser W: Calibration of misonidazole labeling by simultaneous measurement of oxygen tension and labeling density in multicellular spheroids. Int J Cancer 61: 567–573, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenberger C, Heyman SN, Rosen S, Shina A, Goldfarb M, Griethe W, Frei U, Reinke P, Bachmann S, Eckardt KU: Up-regulation of HIF in experimental acute renal failure: Evidence for a protective transcriptional response to hypoxia. Kidney Int 67: 531–542, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasuda H, Yuen PS, Hu X, Zhou H, Star RA: Simvastatin improves sepsis-induced mortality and acute kidney injury via renal vascular effects. Kidney Int 69: 1535–1542, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heyman SN, Rosenberger C, Rosen S: Experimental ischemia-reperfusion: Biases and myths-the proximal vs. distal hypoxic tubular injury debate revisited. Kidney Int 77: 9–16, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosenberger C, Mandriota S, Jürgensen JS, Wiesener MS, Hörstrup JH, Frei U, Ratcliffe PJ, Maxwell PH, Bachmann S, Eckardt KU: Expression of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha and -2alpha in hypoxic and ischemic rat kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1721–1732, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maxwell PH: HIF-1’s relationship to oxygen: Simple yet sophisticated. Cell Cycle 3: 156–159, 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Metzen E, Ratcliffe PJ: HIF hydroxylation and cellular oxygen sensing. Biol Chem 385: 223–230, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Semenza GL: Hydroxylation of HIF-1: Oxygen sensing at the molecular level. Physiology (Bethesda) 19: 176–182, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wenger RH, Stiehl DP, Camenisch G: Integration of oxygen signaling at the consensus HRE. Sci STKE 2005: re12, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ortiz-Barahona A, Villar D, Pescador N, Amigo J, del Peso L: Genome-wide identification of hypoxia-inducible factor binding sites and target genes by a probabilistic model integrating transcription-profiling data and in silico binding site prediction. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 2332–2345, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schödel J, Mole DR, Ratcliffe PJ: Pan-genomic binding of hypoxia-inducible transcription factors. Biol Chem 394: 507–517, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Semenza GL: HIF-1 mediates the Warburg effect in clear cell renal carcinoma. J Bioenerg Biomembr 39: 231–234, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaelin WG, Jr: The von Hippel-Lindau tumour suppressor protein: O2 sensing and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 8: 865–873, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mathia S, Paliege A, Koesters R, Peters H, Neumayer HH, Bachmann S, Rosenberger C: Action of hypoxia-inducible factor in liver and kidney from mice with Pax8-rtTA-based deletion of von Hippel-Lindau protein. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 207: 565–576, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aukland K, Krog J: Renal oxygen tension. Nature 188: 671, 1960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leichtweiss HP, Lübbers DW, Weiss C, Baumgärtl H, Reschke W: The oxygen supply of the rat kidney: Measurements of intrarenal pO2. Pflugers Arch 309: 328–349, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Evans RG, Gardiner BS, Smith DW, O’Connor PM: Intrarenal oxygenation: Unique challenges and the biophysical basis of homeostasis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F1259–F1270, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Semenza GL, Roth PH, Fang H-M, Wang GL: Transcriptional regulation of genes encoding glycolytic enzymes by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. J Biol Chem 269: 23757–23763, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen C, Pore N, Behrooz A, Ismail-Beigi F, Maity A: Regulation of glut1 mRNA by hypoxia-inducible factor-1. Interaction between H-ras and hypoxia. J Biol Chem 276: 9519–9525, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holotnakova T, Ziegelhoffer A, Ohradanova A, Hulikova A, Novakova M, Kopacek J, Pastorek J, Pastorekova S: Induction of carbonic anhydrase IX by hypoxia and chemical disruption of oxygen sensing in rat fibroblasts and cardiomyocytes. Pflugers Arch 456: 323–337, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cormier-Regard S, Nguyen SV, Claycomb WC: Adrenomedullin gene expression is developmentally regulated and induced by hypoxia in rat ventricular cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem 273: 17787–17792, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee PJ, Jiang BH, Chin BY, Iyer NV, Alam J, Semenza GL, Choi AM: Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 mediates transcriptional activation of the heme oxygenase-1 gene in response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem 272: 5375–5381, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pastoreková S, Parkkila S, Parkkila AK, Opavský R, Zelník V, Saarnio J, Pastorek J: Carbonic anhydrase IX, MN/CA IX: Analysis of stomach complementary DNA sequence and expression in human and rat alimentary tracts. Gastroenterology 112: 398–408, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raval RR, Lau KW, Tran MG, Sowter HM, Mandriota SJ, Li JL, Pugh CW, Maxwell PH, Harris AL, Ratcliffe PJ: Contrasting properties of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) and HIF-2 in von Hippel-Lindau-associated renal cell carcinoma. Mol Cell Biol 25: 5675–5686, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warnecke C, Zaborowska Z, Kurreck J, Erdmann VA, Frei U, Wiesener M, Eckardt KU: Differentiating the functional role of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1alpha and HIF-2alpha (EPAS-1) by the use of RNA interference: Erythropoietin is a HIF-2alpha target gene in Hep3B and Kelly cells. FASEB J 18: 1462–1464, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosen S, Stillman IE: Acute tubular necrosis is a syndrome of physiologic and pathologic dissociation. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 871–875, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brigati C, Banelli B, di Vinci A, Casciano I, Allemanni G, Forlani A, Borzì L, Romani M: Inflammation, HIF-1, and the epigenetics that follows. Mediators Inflamm 2010: 263914, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luo W, Chang R, Zhong J, Pandey A, Semenza GL: Histone demethylase JMJD2C is a coactivator for hypoxia-inducible factor 1 that is required for breast cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: E3367–E3376, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goda N, Kanai M: Hypoxia-inducible factors and their roles in energy metabolism. Int J Hematol 95: 457–463, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gustafsson AB: Bnip3 as a dual regulator of mitochondrial turnover and cell death in the myocardium. Pediatr Cardiol 32: 267–274, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Periyasamy-Thandavan S, Jiang M, Schoenlein P, Dong Z: Autophagy: Molecular machinery, regulation, and implications for renal pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297: F244–F256, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bruick RK: Expression of the gene encoding the proapoptotic Nip3 protein is induced by hypoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97: 9082–9087, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gall JM, Wong V, Pimental DR, Havasi A, Wang Z, Pastorino JG, Bonegio RG, Schwartz JH, Borkan SC: Hexokinase regulates Bax-mediated mitochondrial membrane injury following ischemic stress. Kidney Int 79: 1207–1216, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schley G, Klanke B, Schödel J, Forstreuter F, Shukla D, Kurtz A, Amann K, Wiesener MS, Rosen S, Eckardt KU, Maxwell PH, Willam C: Hypoxia-inducible transcription factors stabilization in the thick ascending limb protects against ischemic acute kidney injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 2004–2015, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wei Q, Hill WD, Su Y, Huang S, Dong Z: Heme oxygenase-1 induction contributes to renoprotection by G-CSF during rhabdomyolysis-associated acute kidney injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F162–F170, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang MZ, Yao B, Yang S, Jiang L, Wang S, Fan X, Yin H, Wong K, Miyazawa T, Chen J, Chang I, Singh A, Harris RC: CSF-1 signaling mediates recovery from acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest 122: 4519–4532, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nath KA, Haggard JJ, Croatt AJ, Grande JP, Poss KD, Alam J: The indispensability of heme oxygenase-1 in protecting against acute heme protein-induced toxicity in vivo. Am J Pathol 156: 1527–1535, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.University of Minnesota Research Animal Resources: Facial vein technique: How to obtain blood samples from the facial vein of a mouse. Available at: http://www.ahc.umn.edu/rar/facial_vein.html Accessed August 4, 2013

- 59.Bachmann S, Kriz W: Histotopography and ultrastructure of the thin limbs of the loop of Henle in the hamster. Cell Tissue Res 225: 111–127, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zager RA, Foerder C, Bredl C: The influence of mannitol on myoglobinuric acute renal failure: Functional, biochemical, and morphological assessments. J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 848–855, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lai EY, Martinka P, Fähling M, Mrowka R, Steege A, Gericke A, Sendeski M, Persson PB, Persson AE, Patzak A: Adenosine restores angiotensin II-induced contractions by receptor-independent enhancement of calcium sensitivity in renal arterioles. Circ Res 99: 1117–1124, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang B, Kirov SA, Snoddy JR: WebGestalt: An integrated system for exploring gene sets in various biological contexts. Nucleic Acids Res 33: W741–W748, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 63.Duncan DT, Prodduturi N, Zhang B: WebGestalt2: An updated and expanded version of the Web-based Gene Set Analysis Toolkit. BMC Bioinformatics 11[Suppl 4]: 10, 2010. 20053291 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.