Abstract

The structure-activity relations of myxinidin, a peptide derived from epidermal mucus of hagfish, Myxine glutinosa L., were investigated. Analysis of key residues allowed us to design new peptides with increased efficiency. Antimicrobial activity of native and modified peptides demonstrated the key role of uncharged residues in the sequence; the loss of these residues reduces almost entirely myxinidin antimicrobial activity, while insertion of arginine at charged and uncharged position increases antimicrobial activity compared with that of native myxinidin. Particularly, we designed a peptide capable of achieving a high inhibitory effect on bacterial growth. Experiments were conducted using both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) studies showed that myxinidin is able to form an amphipathic α-helical structure at the N terminus and a random coil region at the C terminus.

INTRODUCTION

The extensive use of broad-spectrum antibiotics has led to the emergence of resistance to classical antibiotics for many bacterial human pathogens and has posed a major threat to global health care. Effective infection control measures and development of new classes of antimicrobial agents with lower rates of resistance development necessitate extensive efforts and are urgently required (1, 2).

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are an essential part of the innate immune response, with both direct microbicidal and pleiotropic immunomodulatory properties (3, 4). The ubiquitous presence of AMPs in nature (microorganisms, insects, invertebrates, amphibians, plants, birds, and mammals) (5–7) attests to their key role in building the defense strategies of most organisms.

AMPs may display similar modes of action against a wide range of microbes and share several properties. In addition to microbicidal capabilities, certain peptides also confer diverse functions that have an impact on the quality and effectiveness of the innate immune responses and inflammation (8).

Nowadays, AMPs are considered a potential source of novel antibiotics because of their numerous advantages such as broad-spectrum activity, lower tendency to induce resistance, immunomodulatory response, and unique mode of action (9–11). Essentially all these properties are correlated to the fact that the target of AMPs is the bacterial membrane; as for cationic AMPs, the surface of the bacterial cell is composed of negatively charged components, and the electrostatic interaction between the cationic peptidic sequence and the bacterial cell surface plays a key role in antibacterial activity. However, despite the identification and rational design of amphipathic peptides that combine very good antimicrobial activity and low in vitro toxicity against mammalian cells, only a few peptides suitable for systemic administration have so far been developed (12–15). The drawbacks to their clinical use are correlated to their poor bioavailability, potential immunogenicity, and high production cost. Thus, to overcome the limitations of native peptides, peptidomimetics have become an important and promising approach. Many AMPs can be optimized to enhance their effectiveness and stability through modification of their sequences, making them good templates for the development of therapeutic agents (16–18). Bioinformatics has recently helped in developing and/or modifying preexisting AMPs, driving their synthesis toward more effective and selective drugs. Cationic AMPs of the α-helical class have two unique features: a net positive charge of at least +2 and an amphipathic character, with a nonpolar face and a polar/charged face (19). The goals in the development of antimicrobial peptides are to optimize hydrophobicity, to minimize eukaryotic cell toxicity, and to maximize antimicrobial activity, which, in turn, optimize the therapeutic index.

Peptides with antimicrobial activity were reported mainly from insects and amphibians approximately 30 years ago (examples of such AMPs are bombinin, melittin, and cecropins), but since then, several hundreds of AMPs have been discovered (lists can be found at http://www.bbcm.univ.trieste.it/ and http://aps.unmc.edu/AP/main.php). An underestimated group of potentially useful AMPs has been identified in hagfish, which possess a strong innate immune system that acts as the first line of defense against a broad spectrum of pathogens (20).

Recently, several AMPs have been identified in fish epidermal mucus (21). The mucous stratus secreted by goblet or mucus cells in fish epidermis functions as a physical and biochemical barrier between the fish and its aquatic environment to protect fishes from the invasion of pathogenic or opportunistic microbes. The mucous layer provides mechanical protective functions, but the prevention of colonization by parasites, bacteria, and fungi is also warranted by the chemical molecules present in the mucus having antimicrobial characteristics. Recently, a novel cationic AMP, myxinidin, was discovered in mucus of hagfish (Myxine glutinosa L.) (22). Myxinidin is a 12-amino-acid peptide with a molecular mass of 1,327.68 Da (Gly-Ile-His-Asp-Ile-Leu-Lys-Tyr-Gly-Lys-Pro-Ser), and it is one of the shortest AMPs discovered so far. Myxinidin showed potent antibacterial activity against a broad range of bacteria and yeast pathogens at minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBC) between 1 and 10 μg/ml depending on the microorganism (22). The microbicidal activity of myxinidin was retained in the presence of sodium chloride (NaCl) at concentrations up to 0.3 M, and myxinidin had no hemolytic activity against mammalian red blood cells. The antimicrobial activity of myxinidin (22) has been found to be more potent than that of the known fish-derived antimicrobial peptide pleurocidin, and the preserved activity at high salt concentrations makes it a good candidate for development as a novel antimicrobial agent.

In this study, we designed a series of structurally modified synthetic myxinidin analogues and determined their antimicrobial activities and secondary structure to elucidate the structure-function relations. The results have provided important information for further optimization of myxinidin-based anti-infective agents and the design of novel analogues to be employed in biophysical studies for analyzing the membranotropic behavior of myxinidin and its putative mechanism of action.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

The amino acids used for the peptide synthesis, the Rink amide MBHA resin, and the activators N-hydroxybenzotriazole (HOBT) and O-benzotriazole-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl-uronium-hexafluoro-phosphate (HBTU) were purchased from Novabiochem (Gibbstown, NJ). Acetonitrile (ACN) was from Reidel-deHaën (Seelze, Germany) and dry N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) from LabScan (Dublin, Ireland). All other reagents were from Sigma-Aldrich (Milan, Italy). Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analyses were performed on a Thermo Finnigan LC-MS with an electrospray source (MSQ) on a Phenomenex Jupiter 5-μm C18 300-Å (150- by 4.6-mm) column. Purification was carried out on a Phenomenex Jupiter 10-μm Proteo 90-Å (250- by 10-mm) column. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of Escherichia coli O111:B4 was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Mueller-Hinton broth (MHB) and Mueller-Hinton agar (MHA) were purchased from Oxoid (Basingstoke, Hampshire, United Kingdom); Mueller-Hinton broth II, cation adjusted (product no. 212322), was purchased from BD (Franklin Lakes, NJ).

Peptide synthesis.

Peptides were synthesized using the standard solid-phase 9-fluorenylmethoxy carbonyl (Fmoc) method as previously reported (23). Briefly, 50 μmol of peptide was synthesized on a Rink amide MBHA (0.54 mmol/g) resin by consecutive deprotection, coupling, and capping cycles as follows: deprotection, 30% piperidine in DMF, 5 min (2×); coupling, 4 equivalents of amino acid plus 4 equivalents of HOBT/HBTU (0.45 M in DMF), 25 min; capping: acetic anhydride-DIPEA (N,N-diisopropylethylamine)-DMF (15/15/70, vol/vol/vol), 5 min. Peptides were cleaved from the resin and deprotected by treatment with trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and precipitated in cold ethylic ether. Analysis of the crude peptides was performed by electrospray ionization (ESI) LC-MS using a gradient of acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) in water (0.1% TFA) from 5 to 70% in 15 min. Peptides were purified by preparative reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) using a gradient of acetonitrile (0.1% TFA) in water (0.1% TFA) from 5 to 70% in 15 min. All purified peptides were obtained with good yields (70 to 80%). Table 1 shows the sequences of all the synthesized peptides.

Table 1.

Comparison of myxinidin and analogues with respect to charge, hydrophobicity, hydrophobic moment, relative hydrophobic moment, and percent helicity

| Peptide | Sequencea | Charge | Hb | μHc | μHreld | % helicity in TFE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myxinidin | NH2-GIHDILKYGKPS-CONH2 | +1 | −0.96 | 2.81 | 0.44 | 63 |

| MH3K | NH2-GIKDILKYGKPS-CONH2 | +2 | −1.47 | 3.12 | 0.49 | 63 |

| MH3R | NH2-GIRDILKYGKPS-CONH2 | +2 | −1.48 | 3.12 | 0.49 | 61 |

| MD4K | NH2-GIHKILKYGKPS-CONH2 | +3 | −1.1 | 2.91 | 0.46 | 67 |

| MD4R | NH2-GIHRILKYGKPS-CONH2 | +3 | −1.1 | 2.92 | 0.46 | 64 |

| MP11K | NH2-GIHDILKYGKKS-CONH2 | +2 | −1.77 | 3.57 | 0.57 | 77 |

| MP11R | NH2-GIHDILKYGKRS-CONH2 | +2 | −1.78 | 3.58 | 0.57 | 84 |

| MS12B | NH2-GIHDILKYGKPβA-CONH2 | +1 | NDe | ND | ND | 65 |

| MK | NH2-GIKKILKYGKKS-CONH2 | +5 | −2.41 | 3.93 | 0.62 | 64 |

| MR | NH2-GIRRILKYGKRS-CONH2 | +5 | −2.44 | 3.95 | 0.63 | 69 |

| WMR | NH2-WGIRRILKYGKRS-CONH2 | +5 | −1.5 | 2.9 | 0.46 | 62 |

| Ac-WMR | Ac-WGIRRILKYGKRS-CONH2 | +5 | ND | ND | ND | 63 |

| Ac-MR | Ac-GIRRILKYGKRS-CONH2 | +5 | ND | ND | ND | 68 |

| M4R | NH2-GIRRILRYGRPS-CONH2 | +4 | −1.64 | 3.22 | 0.51 | 58 |

| M5R | NH2-GIRRILRYGRRS-CONH2 | +5 | −2.45 | 3.96 | 0.63 | 68 |

Modified residues are reported in bold; all peptides are amidated at the C terminus (CONH2).

The mean hydrophobicity (H) is the total hydrophobicity (sum of all residue hydrophobicity indices) divided by the number of residues.

The mean hydrophobic moment (μH) is the vectorial sum of all the hydrophobicity indices divided by the number of residues, and it depends on the conformation that has been selected (α helix).

The relative hydrophobic moment (μHrel) of a peptide is its hydrophobic moment relative to that of a perfectly amphipathic peptide. This gives a better idea of the amphipathicity using different scales. A value of 0.5 indicates that the peptide has about 50% of the maximum possible amphipathicity.

ND, not determined.

CD measurements.

Circular-dichroism (CD) spectra were recorded using a Jasco J-715 spectropolarimeter in a 0.1-cm quartz cell at room temperature. The spectra are an average of 3 consecutive scans from 250 to 195 nm, recorded with a bandwidth of 3 nm, a time constant of 16 s, and a scan rate of 10 nm/min. Spectra were recorded and corrected for the blank sample. Mean residue ellipticities (MRE) were calculated using the expression MRE = Obsd/(lcn), where Obsd is the ellipticity measured in millidegrees, l is the path length of the cell in cm, c is the peptide concentration in mol/liter, and n is the number of amino acid residues in the peptide. All measurements were made in phosphate buffer (5 mM, pH 7.5) and in 50% trifluoroethanol-phosphate buffer solution, using a peptide concentration of 100 μM.

NMR studies.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) samples were prepared by dissolving each peptide (1 mg) in either 600 μl of a 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer solution at a pH of 7.4 with 10% (vol/vol) D2O (99.8% d; Armar Chemicals, Switzerland) or a mixture of 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH = 7.4) and TFE (2-2-2 trifluorethanol-d3, 98% d, Armar Chemicals, Switzerland) (50/50, vol/vol).

NMR spectra were acquired on a VarianUNITY INOVA 600 spectrometer equipped with a cold probe and a VarianUNITY INOVA 400 spectrometer provided with z-axis pulsed-field gradients and a triple-resonance probe.

The DPFGSE (double pulsed-field gradient selective echo) technique (24) was used for water suppression. One-dimensional (1D) [1H] proton experiments were recorded with a relaxation delay (d1) of 1.5 s and 16 to 64 scans. Proton resonances were assigned with a canonical protocol (25) relying on analysis of the following 2D [1H, 1H] NMR experiments: TOCSY (total correlation spectroscopy) (26) (1,024 × 128 total data points, 8 to 16 scans per t1 increment, and 70-ms mixing time), NOESY (nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy) (27) (2,048 × 256 total data points, 32 to 64 scans per time increment (t1) and 200- and 300-ms mixing times), and DQFCOSY (double quantum filter correlation spectroscopy) (28) (2,048 × 256 total data points and 64 to 128 scans per delay time (t1) increment). TSP (trimethylsilyl-3-propionic acid sodium salt-d4, 99% d; Armar Chemicals, Switzerland) was used as an internal standard for chemical shift referencing.

NMR data were processed with the Varian software VNMRJ 1.1D (Varian by Agilent Technologies, Italy); the programs MestRe-C2.3a (Universitade de Santiago de Compostela) and NEASY (29) (http://www.nmr.ch/) were used for analysis of 1D and 2D NMR spectra, respectively.

Structure calculations were conducted with the program CYANA (version 2.1) (30). Distance constraints were gained from NOESY experiments (200-ms mixing time). Angular constraints were generated with the GRIDSEARCH module of CYANA. Calculations started from 100 random conformers; 20 3D models (i.e., the ones with the lowest CYANA target functions) were chosen as representative of the NMR solution structure and were finally inspected with the programs MOLMOL (31) and iCing (http://proteins.dyndns.org/cing/iCing.html) (32).

Microorganisms.

The strains used for the antimicrobial assays were selected to provide a certified standard for antimicrobial testing using reference strains from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), USA.

The following strains were included in our study: the Gram-negative bacteria Escherichia coli ATCC 11219, Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 13388, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028, and Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 10031 and the Gram-positive bacterium Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 6538.

To standardize the bacterial cell suspension for assay of antibacterial activity, some colonies of each strain grown overnight on MHA plates were resuspended in MHB and incubated at 37°C until visibly turbid. This log-phase inoculum was resuspended in 0.9% sterile saline to reach an appropriate optical density at 600 nm (OD600) (with a Bio-Rad microplate reader; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) corresponding to a concentration of about 1 × 108 CFU/ml. This standardized inoculum was diluted 1:10 in MHB, and the inoculum size was confirmed by colony counting.

Antimicrobial-activity assay.

Susceptibility testing was performed using the broth microdilution method outlined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute using sterile 96-well microtiter plates (Falcon, NJ). Serial 2-fold dilutions (0.1 to 50 μM) of each peptide were prepared in cation-adjusted MHB (CAMHB) at a volume of 100 μl/well. Each well was inoculated with 5 μl of the standardized bacterial inoculum, corresponding to a final test concentration of about 5 × 105 CFU/ml. Antimicrobial activities were expressed as the MIC, the lowest concentration of peptide at which 100% inhibition of microbial growth was observed after 24 h of incubation at 37°C. Each assay was performed in triplicate, and the mean antimicrobial activity is reported.

Cytotoxicity against eukaryotic cells.

Vero cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of compounds, and the number of viable cells was determined using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay that is based on the reduction of the yellowish MTT to the insoluble and dark blue formazan by viable and metabolically active cells (33). Vero cells were subcultured in 96-well plates at a seeding density of 2 × 104 cells/well and treated with peptides at concentrations ranging from 1 to 200 μM for 3, 10, and 24 h. The medium was then gently aspirated, MTT solution (5 mg/ml) was added to each well, and cells were incubated for a further 3 h at 37°C. The medium with MTT solution was removed, and the formazan crystals were dissolved with dimethyl sulfoxide. The absorption values were measured at 570 nm using a Bio-Rad microplate reader. The viability of Vero cells in each well was presented as a percentage of that of control cells.

Hemolytic assay.

The hemolytic activity of the peptides was determined using fresh human erythrocytes from healthy donors. Blood was centrifuged and the erythrocytes were washed three times with 0.9% NaCl. Peptides were added to the erythrocyte suspension (5%, vol/vol) at a final concentration ranging from 0.1 to 200 μM in a final volume of 100 μl. Samples were incubated with agitation at 37°C for 60 min. The release of hemoglobin was monitored by measuring the absorbance (Abs) of the supernatant at 540 nm. The control for zero hemolysis (blank) consisted of erythrocytes suspended in the presence of peptide solvent. Hypotonically lysed erythrocytes were used as a standard for 100% hemolysis. The percent hemolysis was calculated using the following equation: [(Abssample − Absblank)/(Abstotal lysis − Absblank)] × 100.

RESULTS

Peptide design and synthesis.

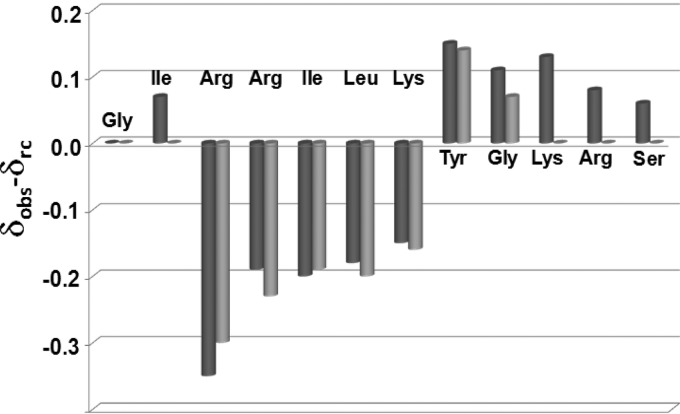

A series of myxinidin analogues were designed by inserting charged residues in fundamental positions. Alignment of native sequence of myxinidin with modified peptides shows the positions that were replaced with charged residues; Fig. 1 shows a helical-wheel representation of myxinidin with the positions of the amino acid substitutions. Arg and Lys residues were introduced to verify their effect on antimicrobial activity. A Trp residue was introduced to verify its ability to increase antibacterial activity and reduce hemolytic activity. Furthermore, the C terminus was amidated to increase stability. The antimicrobial activities of the analogues were tested against Gram-positive (S. aureus) and Gram-negative (E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. Typhimurium, and K. pneumoniae) bacteria. All peptides were obtained with a good yield (>70%). In Table 1 are shown all the peptide sequences used in this study.

Fig 1.

Helical-wheel representation of the native myxinidin peptide showing the positions and types of substitutions.

Toxicity.

To confirm that myxinidin and its modified peptides did not exert toxic effects on cells, monolayers of Vero cells were exposed to different concentrations (0.1 to 200 μM) of each compound for 3, 10, and 24 h, and cell viability was quantified by the MTT assay. No statistical difference was observed between the viability of control (untreated) cells and that of cells exposed to the peptides up to the concentration used in antimicrobial testing. Minimal toxicity was observed only at concentrations that were considerably higher than those required for antimicrobial activity (Table 2).

Table 2.

Toxicities of myxinidin and analogues on Vero cells

| Peptide | Toxicity (% of control) at indicated concn (μM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | 50 | 100 | 200 | |

| Myxinidin | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 10 |

| MH3K | 0 | 0 | 4 | 7 | 10 |

| MH3R | 0 | 0 | 3 | 12 | 22 |

| MD4K | 0 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 28 |

| MD4R | 0 | 0 | 8 | 18 | 41 |

| MP11K | 0 | 0 | 3 | 12 | 16 |

| MP11R | 0 | 0 | 7 | 16 | 28 |

| MS12B | 0 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 14 |

| MK | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 10 |

| MR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 15 |

| WMR | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 12 |

| Ac-WMR | 0 | 0 | 10 | 12 | 18 |

| Ac-MR | 0 | 0 | 4 | 15 | 25 |

| M4R | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 14 |

| M5R | 0 | 0 | 12 | 21 | 41 |

Hemolytic activity.

The hemolytic activities of the peptides against human erythrocytes were determined as a measure of peptide toxicity toward higher eukaryotic cells. Red blood cells were incubated with different peptide solutions and Triton X-100 as a positive control. None of the peptides showed any hemolytic effect up to 50 μM (Table 3).

Table 3.

Toxicities of myxinidin and analogues on erythrocytes, as determined by hemolysis

| Peptide | Hemolysis (% of control) at indicated concn (μM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20 | 50 | 100 | 200 | |

| Myxinidin | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| MH3K | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| MH3R | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 5 |

| MD4K | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 8 |

| MD4R | 0 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 21 |

| MP11K | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 9 |

| MP11R | 0 | 0 | 6 | 8 | 12 |

| MS12B | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 14 |

| MK | 0 | 0 | 3 | 10 | 18 |

| MR | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 8 |

| WMR | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Ac-WMR | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 12 |

| Ac-MR | 0 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 18 |

| M4R | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| M5R | 0 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 22 |

NMR analysis. (i) NMR studies of the MR peptide.

NMR conformational analysis of the MR peptide was conducted in an aqueous buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.4) and in a mixture of sodium phosphate and TFE. TFE is often used as a structuring cosolvent in peptide conformational studies since it can help unveil a peptide's intrinsic propensity to assume specific types of secondary-structure elements (34).

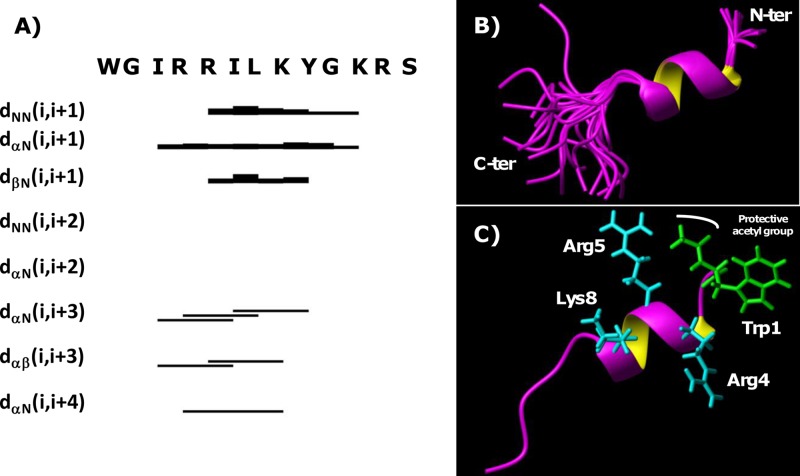

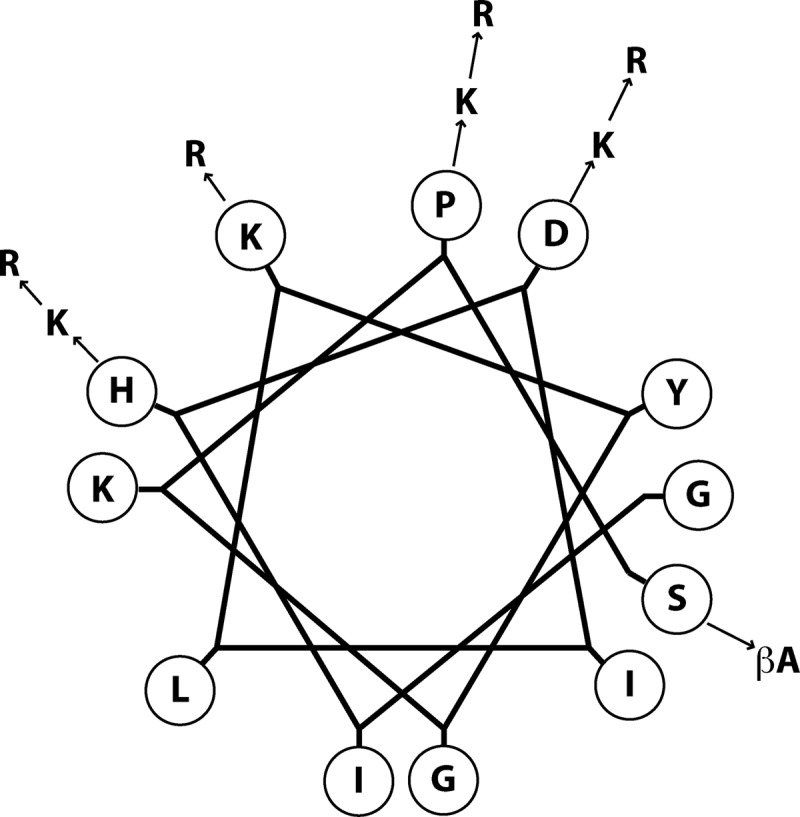

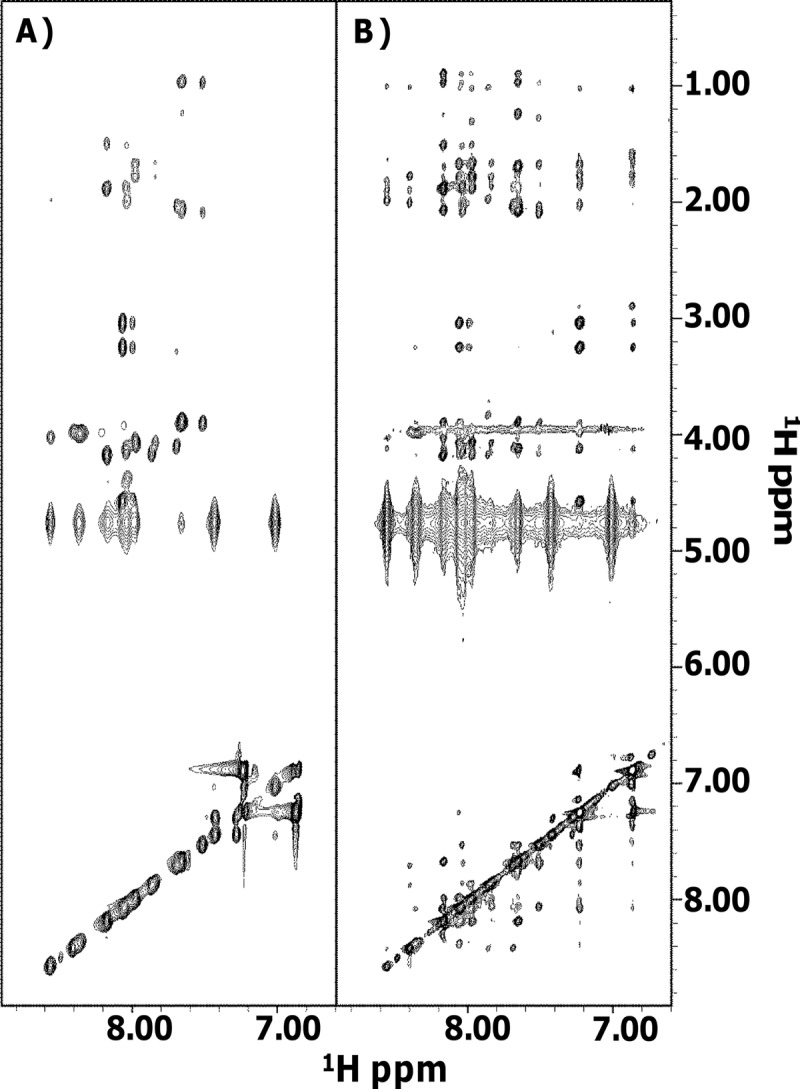

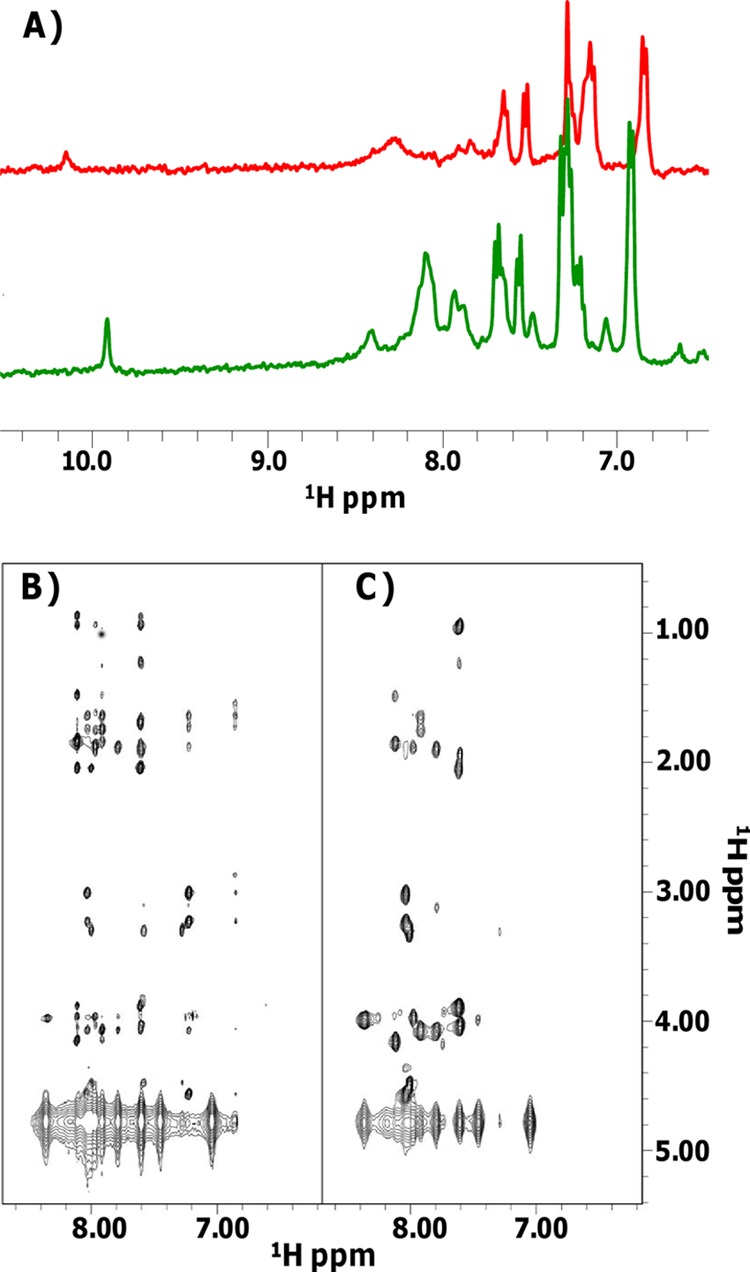

In sodium phosphate buffer, the peptide is unordered and flexible, as can be clearly seen in the 2D [1H, 1H] NOESY experiment (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), which is characterized by the presence of only a very reduced number of cross-peaks. In contrast, addition of TFE highly improves the quality of NMR data (Fig. 2). We conducted detailed analyses of 2D [1H, 1H] TOCSY (Fig. 2A) and 2D [1H, 1H] NOESY (Fig. 2B) spectra recorded in the presence of TFE. Our studies were complicated by the presence of several duplicated spin systems (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) that pointed to the coexistence in solution of two distinct conformers (indicated as A and B in Table S1in the supplemental material). Canonical strategies (25) were used to get proton resonance assignments for most of the spin systems; doubled assignments could be obtained for amino acids from Arg3 to Gly9 (see Table S1). Next, chemical-shift deviations from random coil values (35) were evaluated for Hα protons and indicated a preference of both the A and B species to assume an helical conformation in the region between Arg3 and Lys7 (Fig. 3).

Fig 2.

Comparison of 2D [1H, 1H] TOCSY (A) and 2D [1H, 1H] NOESY (B) of MR. Spectra were acquired at 298 K in phosphate buffer-TFE (50/50, vol/vol).

Fig 3.

Hα chemical-shift deviations from random coil values (δobs− δrc) for MR (35). Dark and light bars refer to the A and B species, respectively. Data are set equal to zero for those residues with unassigned Hα chemical shifts.

Due to spectral overlaps and the availability of only partial proton resonance assignments for the B form (see Table S1), it was not feasible to get a clear picture of the NOE pattern in each conformer. However, several “intermolecular” NOEs were clearly observed between HN protons of the A and B species (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). These data let us speculate that under the experimental conditions used to run the NMR experiments, the peptide was aggregated and likely forming a dimer. A 2-fold peptide dilution (MR final concentration: about 600 μM) did not prevent aggregation, since duplicated spin systems could still be distinguished (see Fig. S2B in the supplemental material); moreover, the presence of two conformations was still evident in the NMR spectra after lowering the temperature from 298 to 285 K (see Fig. S2C).

In conclusion, NMR data show that the MR peptide is likely a dimer in solution; the central portion of the peptide (i.e., residues Arg3 to Lys7) tends to assume a more ordered helical/turn structure, and probably the same region contributes to the dimer interface.

(ii) NMR studies of the Ac-WMR and WMR peptides.

NMR studies of the peptides Ac-WMR (provided with an N-terminal protecting acetyl group) and WMR were conducted in sodium phosphate buffer and in a mixture of sodium phosphate and TFE. In aqueous buffer, both peptides are disordered; in fact, a very poor dispersion and broadening of the lines can be appreciated in the HN regions (between 8.00 and 8.50 ppm) of the 1D spectra (Fig. 4A) and in 2D [1H, 1H] NOESY experiments which contained only a few very weak nondiagonal contacts (data not shown).

Fig 4.

(A) 1D [1H] spectra of Ac-WMR in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) (red) and in phosphate buffer-TFE (50/50, vol/vol) (green). (B and C) 2D [1H, 1H] NOESY (B) and TOCSY (C) spectra of Ac-WMR in phosphate buffer-TFE (50/50, vol/vol).

In the mixture sodium phosphate-TFE, both peptides assume more ordered structures, in agreement with CD results (Table 1); the rather good quality of the 2D spectra that we were able to record in the presence of 50% TFE (Fig. 4) allowed us to gain proton resonance assignments (see Tables S2 and S3 in the supplemental material) and carry out complete 3D structure calculations. Interestingly, for the Ac-WMR and WMR peptides, no duplicated spin system could be revealed, and thus aggregation processes could very likely be discarded.

Chemical-shift deviations from random coil values for Hα protons (35) were evaluated and indicated that either in the presence or in the absence of the protective acetyl group, these peptides exhibit a tendency toward helical secondary-structure elements in the segment from Arg4 to Lys8 (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material). This trend was confirmed by the NOE pattern (Fig. 5A; see also Fig. S5A in the supplemental material): several NOEs indicative of helices, such as HNi-HN(i + 1), Hαi-HN(i + 3), Hαi-Hβ(i + 3), and Hαi-HN(i + 4), could, in fact, be identified.

Fig 5.

(A) NOE intensity pattern for Ac-WMR in sodium phosphate buffer-TFE. Different residues are indicated with the one-letter amino acid code; “dlm (i, i+x)” designates a NOE contact between the Hl and Hm protons in the i and i+x residues, respectively. (B) Superposition on the backbone atoms (residues 2 to 10) of 20 Ac-WMR structures. (C) Ribbon representation of one representative NMR conformer (i.e., number 2 in the CYANA [30] ensemble). Side chains of the N-terminal Trp and of positively charged residues on the polar helix face are shown. The final CYANA calculation included 101 upper distance limits: 61 intraresidue, 32 short range, and 8 medium range.

3D peptide models were built with the software CYANA (see Tables S4 and S5 in the supplemental material). NMR structures of Ac-WMR (Fig. 5B and C) and WMR (see Fig. S5B and C in the supplemental material) are well defined in the region including residues 2 to 10. Inspection with the software MOLMOL (31) indicated the presence of an α helix encompassing regions Arg4 to Lys8 and Ile3 to Lys8 in WMR and Ac-WMR, respectively. The helix is amphiphilic; the hydrophobic surface includes Ile3, Ile6, and Leu7, whereas the positively charged residues Arg4, Arg5, and Lys8 belong to the polar face (see Fig. 5C for Ac-WMR and Fig. S5C in the supplemental material for WMR).

The presence of an acetyl protection does not appear to influence the structure significantly, as indicated by the similar NMR parameters gained for both peptides.

Antibacterial activity.

In order to assess the structure-activity relationship (SAR) in our novel designed molecules, we analyzed the set of the synthesized analogue peptides for their antibacterial activities. The antimicrobial activities of these analogues were analyzed by the broth microdilution method against the Gram-negative bacteria E. coli, P. aeruginosa, S. Typhimurium, and K. pneumoniae and the Gram-positive bacterium S. aureus. The results are shown in Table 4. At up to 50 μM, all peptides were found to be nontoxic to Vero cells and erythrocytes.

Table 4.

MICs of myxinidin and analogues for different microbial strains

| Peptide | MIC (μM) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | P. aeruginosa | S. Typhimurium | K. pneumoniae | S. aureus | |

| Myxinidin | 5 | 30 | 20 | 10 | 10 |

| MH3K | 10 | 30 | 5 | 10 | 15 |

| MH3R | 5 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| MD4K | 5 | 20 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

| MD4R | 2.2 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 10 |

| MP11K | 10 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 30 |

| MP11R | 10 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 10 |

| MS12B | 10 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 5 |

| MK | 20 | >50 | 20 | >50 | 5 |

| MR | 4 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 |

| WMR | 2 | 2 | 1.2 | 3 | 2.2 |

| Ac-WMR | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2 | 2.5 | 20 |

| Ac-MR | 5 | 20 | 20 | 5 | 2.2 |

| M4R | 4 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 |

| M5R | 3 | 20 | 10 | 5 | 10 |

We designed and synthesized four groups of analogues starting from the native sequence. The four groups involve a minimum of 1 to a maximum of 5 substitutions in the sequence of myxinidin in putative key positions. In particular, for group 1, the histidine in position 3, which is located on the hydrophilic face of the helix, was replaced with a lysine or an arginine (MH3K and MH3R); for group 2, the aspartic acid in position 4 was modified to a positively charged residue and thus replaced with a lysine or an arginine (MD4K and MD4R); for group 3, the proline in position 11, being a helix-perturbing element, was replaced with a lysine or an arginine (MP11K and MP11R); and for group 4, the serine in position 12, located on the hydrophobic face of the helix, was replaced with a β-Ala (MS12B). Then we designed peptides with a combination of substitutions of lysine and arginine residues at positions 3, 4, and 11, positions 3, 4, 7, and 10, and positions 3, 4, 7, 10, and 11. Finally, we designed a peptide containing an extra tryptophan residue at its N terminus.

In Table 1, we report together with hydrophobicity also the mean hydrophobic moment of the hypothetical α-helical structure assumed in the bilayer and the relative hydrophobic moment, which should be 1 for a peptide that has the maximum possible amphipathicity. These parameters were calculated as previously reported (36, 37). The two peptides MH3K and MH3R, in which the histidine residue present on the hydrophilic face of the helix was replaced with a lysine or an ariginine residue, showed slightly lower hydrophobicity and higher amphipathicity than did the native sequence, and their percentage of helix in TFE is conserved. Their activity toward Gram-negative bacteria is similar to that of the native sequence, with the arginine analogue being more active. It is interesting that their activity against Gram-positive bacteria is conserved.

Several AMPs contain negatively charged residues on their polar face, but the significance of this feature still remains not fully understood. In our case the replacement of the aspartic acid with a lysine or an arginine determined a substantial increase of activity especially with the arginine, indicating that this position has to be occupied by a cationic residue.

The third group corresponds to the substitution of the proline residue. Usually, the proline disrupts the α-helical structure forming a kink in the polypeptide chain, determining a substantial loss of the helical content. In our experiments, we explored the possibility of introducing a positively charged residue in this position. The introduction of the lysine or arginine causes a decrease of hydrophobicity, an increase of amphiphilicity, and a higher helical content and determines a reduction of activity. The two peptides show a lower inhibitory activity than does the native sequence. In fact, the formation of the α-helical structure before engaging membrane interactions may not be beneficial; thus, the antimicrobial potency may be related to the inducibility of a helical conformation in a membrane mimicking environment rather than intrinsic helical stability. The common view for cationic AMPs is that after reaching the microbial cytoplasmic membrane, the peptide initially interacts with the negatively charged head groups of the external leaflet and then assumes an amphipathic helical conformation that allows them to insert the hydrophobic face into the bilayer. This unique interplay between the initial electrostatic interaction and the following hydrophobic partition confers on AMPs the unique characteristic of being highly water soluble yet able to interact strongly with phospholipid bilayers.

The fourth group corresponds to the replacement of the C-terminal serine with a β-Ala. Introducing a positive charge onto the nonpolar face of an amphipathic helix is an extreme way of disrupting amphipathicity, which nonetheless contributes both to the suppression of binding to membranes with little surface charge and to the enhancement of binding to negatively charged membranes (38). As a matter of fact, the replacement of the Ser present on the hydrophobic face of myxinidin with β-alanine reduces activity against E. coli and K. pneumoniae.

Furthermore, as the positively charged amino acids are essential for the interaction between antimicrobial peptides and bacterial membranes, we investigated the possibility of introducing several positively charged side chains into the native sequence in particular positions. The peptides were designed in order to increase the amphipathicity and to better understand the role of lysines and arginine on the polar face. These peptides (MK, MR, M4R, and M5R) effectively show a reduction of hydrophobicity, an increase of amphipathicity, and an increase of helicity (Table 1). All together, they show a substantial reduction of activity, but we always observed a higher activity for peptides having the arginine or a mixture of arginine and lysines.

Arg and Lys side chains can form hydrogen bonds with lipid molecules. The phosphate groups of the lipids form the majority of the hydrogen bonds, with Arg side chains forming more hydrogen bonds than Lys side chains. The guanidinium group of the Arg side chains forms stable bidentate hydrogen bonds with phosphate groups, which are not only geometrically favorable but also energetically more stable. Such bidentate hydrogen bonds between Arg side chains and phosphate groups have been reported in other computational and experimental studies (39, 40). This feature is believed to play an important role in inducing negative curvature in anionic bacterial membranes (41). This powerful hydrogen bonding ability of Arg is coupled to the planar structure of the guanidinium group whose hydrophobic character enables it to easily penetrate into the membrane. Thus, it has been suggested that the antimicrobial activity of peptides containing Arg is higher than that of peptides containing Lys (42, 43).

The last analogues contain a tryptophan residue at the N terminus; the addition of this residue induces a high increase of activity for all bacteria reported in this article, and it is interesting that in this analogue the replacement of the Pro in position 11 with an Arg does not induce an increase of helical content as for the peptides MP11K and MP11R.

DISCUSSION

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are an ancient and universal component of the innate defense mechanisms that developed to control the natural flora and combat pathogens. Many of these peptides act specifically via permeabilization of microbial membranes, but this mechanism is not receptor mediated. The absence for the need of the expression of specific surface receptors could hamper resistance development (mainly due to generation of mutations within the putative recognition site) and confers on AMPs a considerable potential for their development as novel therapeutic agents. AMPs show a marked degree of variability, having evolved to act against distinct microbial targets in different physiological contexts. Two common and functionally important requirements shared by many cationic AMPs, a net cationicity that facilitates interaction with negatively charged microbial surfaces and the ability to assume amphipathic structures that permit incorporation into microbial membranes, do not impose a stringent primary or secondary structural organization, allowing for several different structural types. The natural abundance and diffusion of linear α-helical peptides suggest that this structural arrangement may be involved in innate defense. In order to design novel molecules with improved activity, they have been subjected to numerous structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies.

SAR studies indicate the key role of several parameters that can influence the potency and spectrum of activity: size, sequence, percent helical content, charge, overall hydrophobicity, amphipathicity, and widths of the hydrophobic and hydrophilic faces of the helix. These parameters are intimately related and are the key to designing novel peptides with increased potency and directed antimicrobial activity.

Here, we have reported the modification of selected amino acids of the native myxinidin peptide with the aim of obtaining the highest achievable antimicrobial activity with the minimum toxicity toward host cells.

Our data support the hypothesis that the ability of our peptide analogues to structure into a well-defined, amphipathic α-helix is strongly correlated to antimicrobial activity. On the other hand, formation of a helical structure before membrane interaction is not beneficial. Also, the net positive charge, the type of cationic residues, and the percentage of hydrophobic residues were key factors in determining their antibacterial and hemolytic activities. The charge of our analogues varied widely, from +1 to +6; most active peptides fall around a +5 charge. The distribution of charged and hydrophobic residues in naturally occurring α-helical amphipathic peptides plays an important role. We modified residues onto the polar face, trying to increase the charge, and we noticed that there is also a different activity between lysine and arginine analogues. Arg and Lys side chains can form hydrogen bonds with lipid molecules; the phosphate groups of the lipids form the majority of the hydrogen bonds, with Arg side chains forming more hydrogen bonds than Lys side chains do. This feature is believed to play an important role in inducing negative curvature in anionic bacterial membranes (41). This powerful hydrogen bonding ability of Arg is coupled to the planar structure of the guanidinium group whose hydrophobic character enables it to easily penetrate into the membrane. The reduced toxicity of arginine analogues likely results from their low surface concentration on the mammalian membrane, which appears to arise from reduced electrostatic attractions and hydrogen bonds with mammalian membrane, i.e., lower interfacial activity. In addition, unlike with mammalian cells, the highly negatively charged outer membrane of most bacterial cells (particularly Gram-negative bacteria) serves to concentrate molecules around the surface of the inner membrane, thus further contributing to the selectivity. When the arginine analogues reach a high surface concentration on the bacterial membrane, they may induce large structural perturbations, which probably depend on concentration. The structural perturbations of bacterial membranes may be associated with the formation of defects and subsequent water translocations across the membrane, suggesting that the membrane becomes leaky.

Introducing a positive charge onto the nonpolar face of an amphipathic helix is an extreme way of disrupting amphipathicity. Thus, introducing a positive charge on the nonpolar helix face contributes both to the suppression of binding to membranes with little surface charge and to the enhancement of binding to negatively charged membranes.

Aromatic residues are rare in AMPs and found mostly near the N terminus. We thus decided to verify the antibacterial activity of an analogue containing a tryptophan residue at the N terminus (44). Tryptophan residues have the unique property of being able to interact with the interfacial region of a membrane, thereby anchoring the peptide to the bilayer surface, and are very common in viral fusion peptides (45–47). The Trp residue has a strong membrane-disruptive activity, and this property endows Trp-containing peptides with the unique ability to interact with the surface of bacterial cell membranes. Moreover, the position of Trp residues in these peptides plays a key role in antibacterial activity. Our data further support previous literature (44) showing that the Trp residues at positions 1 and 4 from the amino-terminal side of AMPs play important roles in increasing their antimicrobial activities, whereas the Trp residues at positions 1 and 2 from the carboxyl-terminal side of the peptides inhibited their activity. Our data on the N-terminally modified peptide supported the view that strong hydrophobic amino acid residues at the N terminus significantly enhance peptide antimicrobial activity. The hydrophobicity of the tryptophan allows the peptide to insert more deeply into the hydrophobic core of the bilayer, thus increasing activity. It is interesting to compare the two peptides MR and WMR. The only difference between these two analogues is the presence of the extra tryptophan at the N terminus, which determines a great difference in activity. Our NMR data also show a significant structural difference; in fact, the peptide MR is characterized by the formation of dimers, while the peptide WMR is a monomer. As both peptides are rather active, with WMR being more active, these data support the view that self-oligomerization may not be the only key for membrane disruption and antibacterial activity; moreover, the presence of a high number of positively charged amino acids allows for a local increase in concentration which seems to be important for activity.

The data obtained for S. aureus clearly show that the activity strongly correlates with net charge, although it requires sufficient hydrophobicity and amphipathicity and, in particular, the peptides with increased charge show a higher activity. Other studies previously identified charge as a critical parameter for activity of helical AMPs (48); decreasing the net charge below +3 reduces potency, while increasing the net charge gradually increases activity (49, 50). In this context, it is interesting that positive charge selection appears to characterize the evolution of β-defensins and that hBD3, the human defensin with the highest positive net charge (+10), also has the highest activity against S. aureus (51). It is now well known that structural differences between bacterial and mammalian cell surfaces underlie a certain degree of selectivity for AMP action. Bacterial surfaces contain many anionic components, including LPS and anionic lipids of Gram-negative bacteria, as well as teichoic and teichuronic acids of Gram-positive bacteria. Beyond the outer cell surface, AMPs interact with the plasma membrane. In contrast to eukaryotic membranes, which contain mostly zwitterionic lipids (e.g., phosphatidylcholine), bacterial membranes contain various acidic phospholipids (phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylserine, and cardiolipin) which confer a negative charge facilitating AMP binding.

Our results can be placed in the context of a long series of studies that underline the importance for therapeutic potential of an appropriate balance of hydrophobicity, amphipathicity, and positive charge in α-helical antimicrobial peptides.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Leopoldo Zona for technical assistance.

Financial support was provided by MIUR-PON01_02388, “Verso la medicina personalizzata: nuovi sistemi molecolari per la diagnosi e la terapia di patologie oncologiche ad alto impatto sociale,” Salute dell'Uomo e Biotecnologie.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 September 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01341-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Livermore DM. 2009. Has the era of untreatable infections arrived? J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64(Suppl 1):i29–i36. 10.1093/jac/dkp255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawkey PM. 2008. The growing burden of antimicrobial resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 62(Suppl 1):i1–i9. 10.1093/jac/dkn241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi KY, Chow LN, Mookherjee N. 2012. Cationic host defence peptides: multifaceted role in immune modulation and inflammation. J. Innate Immun. 4:361–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowdish DM, Davidson DJ, Hancock RE. 2005. A re-evaluation of the role of host defence peptides in mammalian immunity. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 6:35–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jenssen H, Hamill P, Hancock RE. 2006. Peptide antimicrobial agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 19:491–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiesner J, Vilcinskas A. 2010. Antimicrobial peptides: the ancient arm of the human immune system. Virulence 1:440–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zasloff M. 2002. Antimicrobial peptides of multicellular organisms. Nature 415:389–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Easton DM, Nijnik A, Mayer ML, Hancock RE. 2009. Potential of immunomodulatory host defense peptides as novel anti-infectives. Trends Biotechnol. 27:582–590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perron GG, Zasloff M, Bell G. 2006. Experimental evolution of resistance to an antimicrobial peptide. Proc. Biol. Sci. 273:251–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Radzishevsky IS, Rotem S, Bourdetsky D, Navon-Venezia S, Carmeli Y, Mor A. 2007. Improved antimicrobial peptides based on acyl-lysine oligomers. Nat. Biotechnol. 25:657–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rotem S, Mor A. 2009. Antimicrobial peptide mimics for improved therapeutic properties. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788:1582–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon YJ, Romanowski EG, McDermott AM. 2005. A review of antimicrobial peptides and their therapeutic potential as anti-infective drugs. Curr. Eye Res. 30:505–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yedery RD, Reddy KV. 2005. Antimicrobial peptides as microbicidal contraceptives: prophecies for prophylactics–a mini review. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 10:32–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim YC, Ludovice PJ, Prausnitz MR. 2010. Transdermal delivery enhanced by antimicrobial peptides. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 6:612–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clara A, Manjramkar DD, Reddy VK. 2004. Preclinical evaluation of magainin-A as a contraceptive antimicrobial agent. Fertil. Steril. 81:1357–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuzaki K. 2009. Control of cell selectivity of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788:1687–1692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Norberg S, O'Connor PM, Stanton C, Ross RP, Hill C, Fitzgerald GF, Cotter PD. 2012. Extensive manipulation of caseicins A and B highlights the tolerance of these antimicrobial peptides to change. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78:2353–2358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Field D, Begley M, O'Connor PM, Daly KM, Hugenholtz F, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. 2012. Bioengineered nisin A derivatives with enhanced activity against both Gram positive and Gram negative pathogens. PLoS One 7:e46884. 10.1371/journal.pone.0046884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hancock RE, Lehrer R. 1998. Cationic peptides: a new source of antibiotics. Trends Biotechnol. 16:82–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Subramanian S, Ross NW, Mackinnon SL. 2008. Comparison of the biochemical composition of normal epidermal mucus and extruded slime of hagfish (Myxine glutinosa L.). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 25:625–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ellis AE. 2001. Innate host defense mechanisms of fish against viruses and bacteria. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 25:827–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subramanian S, Ross NW, MacKinnon SL. 2009. Myxinidin, a novel antimicrobial peptide from the epidermal mucus of hagfish, Myxine glutinosa L. Mar. Biotechnol. (NY) 11:748–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galdiero S, Falanga A, Vitiello M, Browne H, Pedone C, Galdiero M. 2005. Fusogenic domains in herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein H. J. Biol. Chem. 280:28632–28643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dalvit C. 1998. Efficient multiple-solvent suppression for the study of the interactions of organic solvents with biomolecules. J. Biomol. NMR 11:437–444 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wüthrich K. 1986. NMR of proteins and nucleic acids. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griesinger C, Otting G, Wuethrich K, Ernst RR. 1988. Clean TOCSY for proton spin system identification in macromolecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 110:7870–7872 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar A, Ernst RR, Wüthrich K. 1980. A two-dimensional nuclear Overhauser enhancement (2D NOE) experiment for the elucidation of complete proton-proton cross-relaxation networks in biological macromolecules. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 95:1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Piantini U, Sorensen OW, Ernst RR. 1982. Multiple quantum filters for elucidating NMR coupling networks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 104:6800–6801 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartels C, Xia TH, Billeter M, Guntert P, Wüthrich K. 1995. The program XEASY for computer-supported NMR spectral analysis of biological macromolecules. J. Biomol. NMR 6:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herrmann T, Guntert P, Wüthrich K. 2002. Protein NMR structure determination with automated NOE assignment using the new software CANDID and the torsion angle dynamics algorithm DYANA. J. Mol. Biol. 319:209–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wüthrich K. 1996. MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14:51–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doreleijers JF, Sousa da Silva AW, Krieger E, Nabuurs SB, Spronk CA, Stevens TJ, Vranken WF, Vriend G, Vuister GW. 2012. CING: an integrated residue-based structure validation program suite. J. Biomol. NMR 54:267–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mosmann T. 1983. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 65:55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buck M. 1998. Trifluoroethanol and colleagues: cosolvents come of age. Recent studies with peptides and proteins. Q. Rev. Biophys. 31:297–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wishart DS, Sykes BD, Richards FM. 1991. Relationship between nuclear magnetic resonance chemical shift and protein secondary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 222:311–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tossi A, Sandri L, Giangaspero A. 2000. Amphipathic, alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides. Biopolymers 55:4–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giangaspero A, Sandri L, Tossi A. 2001. Amphipathic alpha helical antimicrobial peptides. Eur. J. Biochem. 268:5589–5600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dempsey CE, Hawrani A, Howe RA, Walsh TR. 2010. Amphipathic antimicrobial peptides—from biophysics to therapeutics? Protein Pept. Lett. 17:1334–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li J, Garg M, Shah D, Rajagopalan R. 2010. Solubilization of aromatic and hydrophobic moieties by arginine in aqueous solutions. J. Chem. Phys. 133:054902. 10.1063/1.3469790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Su Y, Waring AJ, Ruchala P, Hong M. 2010. Membrane-bound dynamic structure of an arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptide, the protein transduction domain of HIV TAT, from solid-state NMR. Biochemistry 49:6009–6020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schmidt N, Mishra A, Lai GH, Wong GC. 2010. Arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides. FEBS Lett. 584:1806–1813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pellegrini A, von Fellenberg R. 1999. Design of synthetic bactericidal peptides derived from the bactericidal domain P(18-39) of aprotinin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1433:122–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ma QQ, Dong N, Shan AS, Lv YF, Li YZ, Chen ZH, Cheng BJ, Li ZY. 2012. Biochemical property and membrane-peptide interactions of de novo antimicrobial peptides designed by helix-forming units. Amino Acids 43:2527–2536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bi X, Wang C, Ma L, Sun Y, Shang D. 2013. Investigation of the role of tryptophan residues in cationic antimicrobial peptides to determine the mechanism of antimicrobial action. J. Appl. Microbiol. 115:663–672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galdiero S, Russo L, Falanga A, Cantisani M, Vitiello M, Fattorusso R, Malgieri G, Galdiero M, Isernia C. 2012. Structure and orientation of the gH625-644 membrane interacting region of herpes simplex virus type 1 in a membrane mimetic system. Biochemistry 51:3121–3128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Falanga A, Tarallo R, Vitiello G, Vitiello M, Perillo E, Cantisani M, D'Errico G, Galdiero M, Galdiero S. 2012. Biophysical characterization and membrane interaction of the two fusion loops of glycoprotein B from herpes simplex type I virus. PLoS One 7:e32186. 10.1371/journal.pone.0032186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Falanga A, Cantisani M, Pedone C, Galdiero S. 2009. Membrane fusion and fission: enveloped viruses. Protein Pept. Lett. 16:751–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pasupuleti M, Walse B, Svensson B, Malmsten M, Schmidtchen A. 2008. Rational design of antimicrobial C3a analogues with enhanced effects against staphylococci using an integrated structure and function-based approach. Biochemistry 47:9057–9070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scudiero O, Galdiero S, Nigro E, Del Vecchio L, Di Noto R, Cantisani M, Colavita I, Galdiero M, Cassiman JJ, Daniele A, Pedone C, Salvatore F. 2013. Chimeric beta-defensin analogs, including the novel 3NI analog, display salt-resistant antimicrobial activity and lack toxicity in human epithelial cell lines. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:1701–1708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scudiero O, Galdiero S, Cantisani M, Di Noto R, Vitiello M, Galdiero M, Naclerio G, Cassiman JJ, Pedone C, Castaldo G, Salvatore F. 2010. Novel synthetic, salt-resistant analogs of human beta-defensins 1 and 3 endowed with enhanced antimicrobial activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:2312–2322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harder J, Bartels J, Christophers E, Schroder JM. 2001. Isolation and characterization of human beta-defensin-3, a novel human inducible peptide antibiotic. J. Biol. Chem. 276:5707–5713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.