Abstract

In this study, 425 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) isolates recovered in the Dutch-German Euregio were investigated for the presence of the arginine catabolic mobile element (ACME). Sequence analysis by whole-genome sequencing revealed an entirely new organization of the ACME-staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec composite island (SCCmec-CI), with truncated ACME type II located downstream of SCCmec. An identical nucleotide sequence of ACME-SCCmec-CI was found in two distinct MRSA lineages (t064-ST8 and t002-ST5), which has not been reported previously in S. aureus.

TEXT

The exceptional epidemiological success of the USA300 community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) clone may be related to acquisition of the arginine catabolic mobile element (ACME) (1, 2). ACME of USA300 is located downstream of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) type IVa, forming the ACME-SCCmec composite island (ACME-SCCmec-CI) (1). The most predominant features of ACME are an arginine deiminase gene cluster and an oligopeptide permease operon gene cluster. ACME is not associated with enhanced virulence of USA300 (3). ACME confers enhanced fitness of USA300, which has been shown in a rabbit bacteremia model (4). The presence of ACME enhances colonization of the skin by neutralizing the acidic pH of human sweat. This is achieved by the ACME-encoded arginine deiminase system via the production of ammonia from l-arginine catabolism (5). Moreover, ACME improves S. aureus survival and growth on human skin by depletion of l-arginine, which is the only substrate for production of nitric oxide through nitric oxide synthase isoform (iNOS)-producing macrophages. Additionally, USA300 uses the ACME-carried speG gene to enhance its fitness (6). S. aureus exhibits a unique sensitivity among bacteria to polyamines. Spermidin N-acetyltransferase encoded by the ACME-speG gene counters polyamine toxicity (5, 6).

Three ACME types have been identified so far (1, 7, 8). ACME type I is composed of both the arc gene cluster and the opp gene cluster, ACME type II consists of the arc genes but not the opp cluster, and ACME type III contains the opp genes but not the arc cluster. To date, only ACME type I and a truncated form of ACME type II have been identified in S. aureus.

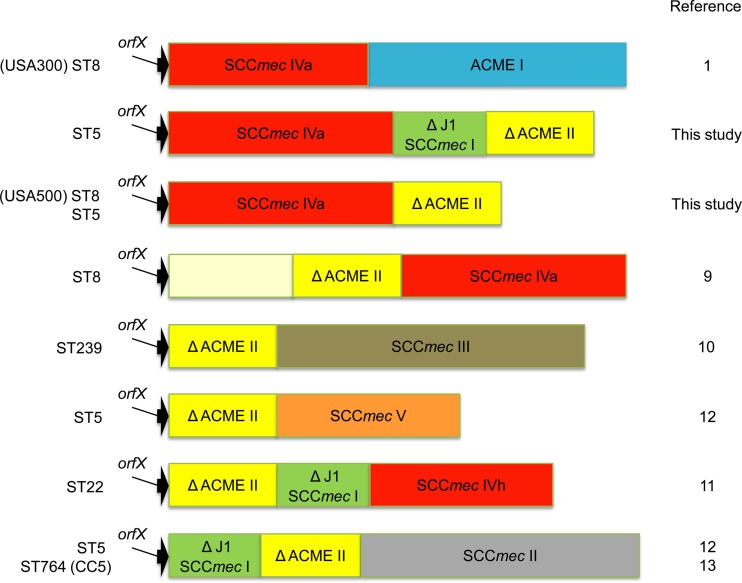

Recently, five novel types of ACME-SCCmec-CI have been reported from MRSA strains with distinct genotypes (9, 10, 11, 12, 13) (Fig. 1). All five novel ACME-SCCmec-CI have a truncated form of ACME type II inserted between orfX and SCCmec and not downstream of SCCmec, like in the case of ACME type I in USA300.

Fig 1.

Schematic representation of ACME-SCCmec-CI.

The objective of this study was to investigate MRSA isolates recovered from patients in hospitals located on the Dutch-German border area of Euregio for the presence of ACME. Moreover, we focused on the determination of genetic organization of ACME-SCCmec-CI in selected ACME-positive isolates by whole-genome sequencing.

A total of 425 MRSA isolates recovered from patients between 2002 and 2012 in the Dutch-German Euregio were genotyped for the present study (14). Total DNA was extracted using the Qiagen DNeasy blood and tissue kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA microarray analysis was conducted using the ArrayMate system (Alere Technologies) and the StaphyType kit (Alere Technologies) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The Alere StaphyType DNA microarray kit for S. aureus covers 334 target sequences. Among the target sequences are also those which allow the detection of the ACME-arc gene cluster, including the ACME-arcABCD genes. To detect the ACME-opp cluster, the ACME-opp3AB genes were used as markers. PCR screening of the ACME-opp3AB genes was performed as described previously (4). MRSA strain USA300-FPR3757 was used as a positive control for PCRs. All isolates were subjected to spa typing (15), DNA microarrays, and PCR detection of the ACME-opp3AB genes. Only ACME-positive isolates were characterized by multilocus sequence type (MLST) (16).

A next-generation sequencing approach was undertaken by Eurofins MWG Operon (Ebersberg, Germany) using a Roche-454 GS FLX+ system and noncloned shotgun DNA libraries. The SeqMan NGen software (version 4.1.2; DNAStar, Madison, WI) was used for de novo assembly of the reads for all selected genomes. The resulting contigs were ordered by using the Mauve Contig Mover (17) relative to the USA300_TCH1516 reference genome (GenBank accession number NC_010079.1). End-to-end alignment of contigs to find overlap between adjoining contigs was accomplished using the SeqMan Pro software (version 10.1.2; DNAStar). It allowed merging the majority of the contigs in the draft genomes. Contigs containing ACME or SCCmec DNA sequences were identified by BLAST software (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The remaining gaps identified between ACME- and SCCmec-related contigs in the whole-genome sequences of selected isolates were closed by an extension of the contig ends using the reference-guided genome closure protocol and the SeqMan NGen software followed by merging contigs in the SeqMan Pro software. Automated genome annotation was achieved using the SeqMan NGen and BLASTN software, followed by manual sequence annotation and editing using the SeqBuilder software (version 10.1.2; DNAStar). The DNA sequences were aligned using the MegAlign (version 10.1.2; DNAStar) and BLASTn software.

Among 425 MRSA isolates characterized, 36 isolates (8.47%) were positive for ACME genes. Twenty nine isolates carried both the ACME-arc and ACME-opp clusters, and based on the spa types and the overall hybridization profiles, they were classified as USA300 (t008-ST8). The remaining 7 ACME-positive isolates contained only the ACME-arc cluster and were associated with t064-ST8 (n = 4) and t002-ST5 (n = 3). All ACME-positive isolates harbored SCCmec type IV.

Whole-genome sequencing was utilized to further characterize the ACME-SCCmec region from 6 selected ACME-positive MRSA isolates. Selection was based on the microarray results, and it was intended to include 2 representative isolates from every ACME-positive genotype which differed most substantially from each other by the gene content. Two types of the ACME-SCCmec composite islands, with sizes between 40 and 54 kb, were found. They had the same type of SCCmec (type IVa) but differed by the ACME types. ACME type I was found in the USA300 isolates, while the truncated form of ACME type II was present in the remaining isolates. In all isolates, SCCmec was located within orfX and ACME was located downstream of SCCmec.

Both USA300 isolates (designated R92 and R114) harbored ACME-SCCmec composite islands of the same size (54,374 bp), with SCCmec IVa 23,387 bp in length and ACME I 30,987 bp in length. The ACME-SCCmec-CI sequences of the R92 and R114 isolates differed by 7 point mutations between each other, and they were located almost equally among the SCCmec and ACME regions, 4 and 3, respectively. The ACME-SCCmec-CI of the R92 and R114 isolates exhibited 99% DNA sequence identity with those of USA300 isolates designated FPR3757 and THC1516. They differed by only 1 (isolates R92 and TCH1516) to 9 (isolates R114 and FPR3537) point mutations. However, the ACME-SCCmec-CI sequences of the FPR3757 and TCH1516 isolates were longer (54,728 and 54,674 bp, respectively) than those of the R92 and R114 isolates due to the differences in the number of tandem repeats of the two variable-number tandem repeat (VNTR) regions located outside the coding sequences. One VNTR region (contains repeats of 40 bp), a direct-repeat unit (dru) region adjacent to IS431 in SCCmec, was 80 nucleotides longer in the FPR3757 and TCH1516 isolates than in the R92 and R114 isolates. A second VNTR region (contains repeats of 55 bp), located within the J1 region of SCCmec, was 220 and 275 nucleotides longer in the TC1516 and FPR3757 isolates, respectively, than in the R92 and R114 isolates.

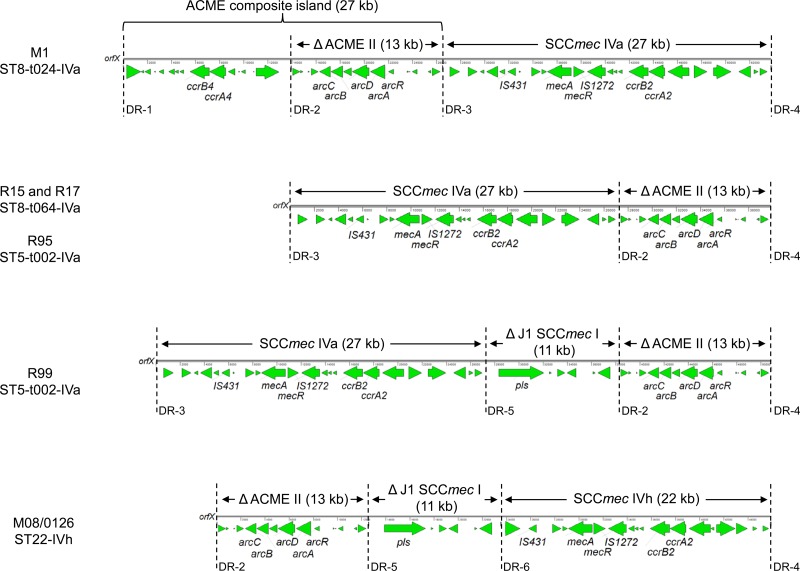

Sequence analysis revealed a novel organization of ACME-SCCmec-CI, with truncated ACME II located downstream of the SCCmec element (Fig. 2), which had not been reported previously in S. aureus. All four isolates showed identical sequences of SCCmec IVa and truncated ACME II of 27,251 bp and 12,544 bp, respectively. Additionally, the isolate R99 had inserted a truncated J1 region of SCCmec I of 11,000 bp between the SCCmec IVa and ACME II elements (Fig. 2). In all four isolates, the ACME-SCCmec elements were flanked by the direct repeat (DR) sequences, DR-3 from the 5′ end and DR-4 from the 3′ end, and DR-2 was present between the SCCmec and ACME regions. An additional DR (DR-5) was identified between SCCmec IVa and the J1 region of SCCmec I in the R99 isolate. The three isolates, R15, R17, and R95, had ACME-SCCmec-CI sequences of the same length, 39,852 bp, while the R99 isolate had a sequence 50,871 bp in size.

Fig 2.

Comparison of the ACME-SCCmec-CI structures from the isolates: M1 (GenBank accession number HM030720), R15 (GenBank accession number KF184643), R17 (GenBank accession number KF184644), R95 (GenBank accession number KF184645), R99 (GenBank accession number KF234240), and M08/0126 (GenBank accession number FR753166). Only the following selected genes are annotated: the arginine deiminase pathway (arcCBDAR), the SCCmec cassette recombinases (ccrB4, ccrA4, ccrB2, and ccrA2), the determinant encoding resistance to methicillin (mecA) and its regulatory gene (mecR), the transposases of IS431 and IS1272, and plasmin-sensitive (pls) surface protein. Sequences of direct repeats (DR): DR1, GAAGCATATCATAAG; DR2, WGAAGCGTATCATAAGTGA; DR3, RGAAGCGTATCACAAATAA; DR4, RGAGGCGTATCATAAGTAA; DR5, RGAAGCGTACCACAAATAA; DR6, AGAAGCATATCATAAATGA.

BLAST searches in the GenBank database showed that the SCCmec IVa and truncated ACME II sequences (from the isolates R15, R17, R95, and R95) were identical to those located between DR-3 and DR-4 and between DR-2 and DR-3, respectively, in isolate M1 (Fig. 2), which is a representative of a common health care-associated MRSA strain in Copenhagen, Denmark (t024-ST8) (7). The sequence of truncated ACME II identified in the current study was also identical to that from the isolate Sa0059 and differed by only a single nucleotide from those from the isolates M08/0126, SR388, and NN54. However, the sequences of the SCCmec region in these isolates represented other SCCmec types than that of the study isolates (R15, R17, R95, and R95), with the exception of the M08/0126 isolate, which possessed another SCCmec subtype, IVh (Fig. 2). In the ACME-SCCmec-CI of the M08/0126 isolate, the truncated J1 region of SCCmec I was also present and showed the highest similarity (∼98%) to the corresponding region (located between DR5 and DR2) in the R99 isolate (Fig. 2) among all deposited sequences in the GenBank database.

In conclusion, we have determined the ACME II element to be located downstream of the SCCmec region, which had not been reported previously in S. aureus. We also show for the first time the identical ACME-SCCmec-CI in two distinct MRSA lineages. Our data show that considerable genetic transfer occurs between genetically different S. aureus strains.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the ACME-SCCmec-CI of R15, R17, R92, R95, R99, and R114 have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers KF184643, KF184644, KF148619, KF184645, KF234240, and KF175393, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Interreg IVa-funded projects EurSafety Heath-net (III-1-02=73) and SafeGuard (III-2-03=025), part of a Dutch-German cross-border network supported by the European Commission, the German Federal States of Nordrhein-Westfalen and Niedersachsen, and the Dutch provinces of Overijssel, Gelderland, and Limburg. This work was supported in part by a grant (grant 01KI1014A) from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF), Germany Interdisciplinary Research Network MedVet-Staph, to K.B., R.K., and A.W.F.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 September 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Diep BA, Gill SR, Chang RF, Phan TH, Chen JH, Davidson MG, Lin F, Lin J, Carleton HA, Mongodin EF, Sensabaugh GF, Perdreau-Remington F. 2006. Complete genome sequence of USA300, an epidemic clone of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet 367:731–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tenover FC, Goering RV. 2009. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain USA300: origin and epidemiology. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64:441–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montgomery CP, Boyle-Vavra S, Daum RS. 2009. The arginine catabolic mobile element is not associated with enhanced virulence in experimental invasive disease caused by the community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus USA300 genetic background. Infect. Immun. 77:2650–2656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diep BA, Stone GG, Basuino L, Graber CJ, Miller A, des Etages SA, Jones A, Palazzolo-Ballance AM, Perdreau-Remington F, Sensabaugh GF, DeLeo FR, Chambers HF. 2008. The arginine catabolic mobile element and staphylococcal chromosomal cassette mec linkage: convergence of virulence and resistance in the USA300 clone of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Infect. Dis. 197:1523–1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thurlow LR, Joshi GS, Clark JR, Spontak JS, Neely CJ, Maile R, Richardson AR. 2013. Functional modularity of the arginine catabolic mobile element contributes to the success of USA300 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Host Microbe 13:100–107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joshi GS, Spontak JS, Klapper DG, Richardson AR. 2011. Arginine catabolic mobile element encoded speG abrogates the unique hypersensitivity of Staphylococcus aureus to exogenous polyamines. Mol. Microbiol. 82:9–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miragaia M, de Lencastre H, Perdreau-Remington F, Chambers HF, Higashi J, Sullam PM, Lin J, Wong KI, King KA, Otto M, Sensabaugh GF, Diep BA. 2009. Genetic diversity of arginine catabolic mobile element in Staphylococcus epidermidis. PLoS One 4:e7722. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbier F, Lebeaux D, Hernandez D, Delannoy AS, Caro V, François P, Schrenzel J, Ruppé E, Gaillard K, Wolff M, Brisse S, Andremont A, Ruimy R. 2011. High prevalence of the arginine catabolic mobile element in carriage isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartels MD, Hansen LH, Boye K, Sørensen SJ, Westh H. 2011. An unexpected location of the arginine catabolic mobile element (ACME) in a USA300-related MRSA strain. PLoS One 6:e16193. 10.1371/journal.pone.0016193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Espedido BA, Steen JA, Barbagiannakos T, Mercer J, Paterson DL, Grimmond SM, Cooper MA, Gosbell IB, van Hal SJ, Jensen SO. 2012. Carriage of an ACME II variant may have contributed to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus sequence type 239-like strain replacement in Liverpool Hospital, Sydney, Australia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:3380–3383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shore AC, Rossney AS, Brennan OM, Kinnevey PM, Humphreys H, Sullivan DJ, Goering RV, Ehricht R, Monecke S, Coleman DC. 2011. Characterization of a novel arginine catabolic mobile element (ACME) and staphylococcal chromosomal cassette mec composite island with significant homology to Staphylococcus epidermidis ACME type II in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus genotype ST22-MRSA-IV. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:1896–1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Urushibara N, Kawaguchiya M, Kobayashi N. 2012. Two novel arginine catabolic mobile elements and staphylococcal chromosome cassette mec composite islands in community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus genotypes ST5-MRSA-V and ST5-MRSA-II. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67:1828–1834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takano T, Hung WC, Shibuya M, Higuchi W, Iwao Y, Nishiyama A, Reva I, Khokhlova OE, Yabe S, Ozaki K, Takano M, Yamamoto T. 2013. A new local variant (ST764) of the globally disseminated ST5 lineage of hospital-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) carrying the virulence determinants of community-associated MRSA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:1589–1595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedrich AW, Daniels-Haardt I, Köck R, Verhoeven F, Mellmann A, Harmsen D, van Gemert-Pijnen JE, Becker K, Hendrix MG. 2008. EUREGIO MRSA-net Twente/Münsterland—a Dutch-German cross-border network for the prevention and control of infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Euro Surveill. 13:pii=18965 http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=18965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aires-de-Sousa M, Boye K, de Lencastre H, Deplano A, Enright MC, Etienne J, Friedrich A, Harmsen D, Holmes A, Huijsdens XW, Kearns AM, Mellmann A, Meugnier H, Rasheed JK, Spalburg E, Strommenger B, Struelens MJ, Tenover FC, Thomas J, Vogel U, Westh H, Xu J, Witte W. 2006. High interlaboratory reproducibility of DNA sequence-based typing of bacteria in a multicenter study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:619–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enright MC, Day NP, Davies CE, Peacock SJ, Spratt BG. 2000. Multilocus sequence typing for characterization of methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible clones of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1008–1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rissman AI, Mau B, Biehl BS, Darling AE, Glasner JD, Perna NT. 2009. Reordering contigs of draft genomes using the Mauve aligner. Bioinformatics 25:2071–2073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]