Abstract

Escherichia coli strains of serogroup O26 comprise two distinct groups of pathogens, characterized as enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) and enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC). Among the several genes related to type III secretion system-secreted effector proteins, espK was found to be highly specific for EHEC O26:H11 and its stx-negative derivative strains isolated in European countries. E. coli O26 strains isolated in Brazil from infant diarrhea, foods, and the environment have consistently been shown to lack stx genes and are thus considered atypical EPEC. However, no further information related to their genetic background is known. Therefore, in this study, we aimed to discriminate and characterize these Brazilian O26 stx-negative strains by phenotypic, genetic, and biochemical approaches. Among 44 isolates confirmed to be O26 isolates, most displayed flagellar antigen H11 or H32. Out of the 13 nonmotile isolates, 2 tested positive for fliCH11, and 11 were fliCH8 positive. The identification of genetic markers showed that several O26:H11 and all O26:H8 strains tested positive for espK and could therefore be discriminated as EHEC derivatives. The presence of H8 among EHEC O26 and its stx-negative derivative isolates is described for the first time. The interaction of three isolates with polarized Caco-2 cells and with intestinal biopsy specimen fragments ex vivo confirmed the ability of the O26 strains analyzed to cause attaching-and-effacing (A/E) lesions. The O26:H32 strains, isolated mostly from meat, were considered nonvirulent. Knowledge of the virulence content of stx-negative O26 isolates within the same serotype helped to avoid misclassification of isolates, which certainly has important implications for public health surveillance.

INTRODUCTION

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) and enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) comprise two of the six diarrheagenic E. coli pathotypes and share the ability to form attaching-and-effacing (A/E) lesions on the intestinal epithelium (1). These lesions are characterized by intimate bacterial attachment to the host cell membrane and microvillus effacement at the sites of bacterial adherence, as a result of the local rearrangement of cytoskeletal components (mainly filamentous actin), which results in pedestal formation at the apical cell membrane (1, 2). The chromosomal locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) contains the genes necessary for A/E lesion formation, one of which (the eae gene) encodes the outer membrane adhesin intimin (3). In contrast to EHEC, EPEC strains lack the stx genes encoding Shiga toxins (Stx) (4). Moreover, EPEC strains may carry a large plasmid known as the EPEC adherence factor plasmid (pEAF) (5, 6), which encodes the bundle-forming pilus (BFP) and plasmid-encoded regulator, a complex regulator of virulence genes (4, 7). Thus, the EPEC pathotype has been subdivided into typical EPEC (tEPEC) and atypical EPEC (aEPEC), with the basic difference being the presence and absence of pEAF and bfp, and BFP expression, respectively (4, 8–10).

E. coli serogroup O26 is one of the most frequent serogroups implicated in diarrhea caused by EPEC and EHEC strains. It commonly includes either the H11/nonmotile (HNM) or the H32 flagellar type (11–13). While O26:H32 strains are usually nonenteropathogenic, the virulence characteristics carried by O26:H11 strains may be variable. Many O26:H11 strains isolated in North America, Europe, and Japan produce Stx (14). In Brazil, O26:H11 has been the second most frequent EHEC serotype observed in São Paulo since the late 1970s (15), and one strain of this serotype was identified in a child with hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) (16). Nevertheless, E. coli isolates of the O26:H11 and O26:HNM serotypes have been identified in infants with diarrhea, but they have consistently been shown to lack the stx genes and have not been associated with HUS (11, 17, 18), therefore being classified as aEPEC.

Some aEPEC and EHEC strains of the O26:H11 serotype have been found to be genetically closely related, as demonstrated by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis (MLEE) (19) and by multiple-locus variable-number tandem-repeat analysis (MLVA), which divides the O26 strains into two clonal lineages by their arcA gene sequences (12). Moreover, it has been demonstrated that EHEC and aEPEC strains can be divided into two clonally related groups depending on the ability of the O26:H11 isolates to ferment rhamnose and dulcitol (20).

The presence of chromosomally encoded virulence attributes such as the LEE effectors and putative adhesins was also found to be conserved in EHEC and EPEC pathotypes (21–28). Some of these adhesins include the long polar fimbriae (21); Iha, a 67-kDa adherence-conferring protein (22); Efa1, an EHEC factor for adherence (23); ToxB, a protein encoded by a gene located on the virulence plasmid (24); Paa, the porcine attaching-and-effacing-associated adhesin (25, 26); and a diffuse adherence (ldaH) locus in an aEPEC strain of the O26 serogroup (27). Moreover, virulence plasmids encoding EHEC-hemolysin (ehxA), catalase peroxidase (katP), and serine protease (espP) are found in most EHEC and in some aEPEC O26:H11 strains (29–31). The presence of a high-pathogenicity island (HPI) encoding an iron uptake system has also been associated with O26:H11/NM EHEC and aEPEC isolates (32, 33). In addition, nle genes of the O islands OI-57, OI-71, and OI-122 were recently found to be significantly associated with aEPEC strains that showed close similarities to EHEC regarding their serotypes and virulence traits (13). However, Bugarel et al. (34), studying a collection of European O26 E. coli strains by a high-throughput PCR approach, showed that among the several genes related to LEE effectors, espK was a highly specific genetic marker that could discriminate EHEC and EHEC derivative isolates.

A third group of O26 E. coli strains, which is represented by the O26:H32 serotype, has been found to lack eae and stx genes (35). These strains were grouped by MLEE into genetic clusters other than O26:H11/NM EPEC/EHEC (19) and formed a separate pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) cluster and two clusters by MLVA (12). Apart from these findings, little is known about the pathogenic potential and the genetic relationship of E. coli O26:H32 and O26:H11/NM strains.

Patterns of in vitro adherence to epithelial cells have been considered a phenotypic approach for the identification of diarrheagenic E. coli pathotypes. Unlike tEPEC strains, which characteristically show the localized adherence pattern (LA) in adherence assays with HEp-2 and HeLa cells, aEPEC strains often express the localized adherence-like (LAL) pattern and, less frequently, the aggregative adherence (AA) and diffuse adherence (DA) patterns in these cell lines (36–40).

In the present work, we aimed to determine the phenotypic, genetic, and biochemical profile of a collection of O26 strains devoid of stx genes, which were isolated in Brazil from different sources. In addition, three isolates exhibiting different adhesion patterns in HeLa epithelial cells were individually tested by using polarized Caco-2 cells, which express brush border enzymes similar to those of the small intestinal epithelium, and human intestinal biopsy specimen fragments ex vivo. Our results showed that several stx-negative EHEC derivative strains were discriminated among O26 strains carrying H11 and H8 antigens (mostly from diarrheic patients), which were originally classified as aEPEC. The presence of the H8 antigen among O26 EHEC or stx-negative derivative isolates is described for the first time.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

A total of 44 E. coli strains belonging to the O26 serogroup and devoid of stx gene sequences were investigated in this study. The strains were isolated in Brazil between 1980 and 1990 and were shown to carry the H11 or H32 antigen or were nonmotile. Twenty-five strains were isolated from children with diarrhea, nine were from children without diarrhea, nine were isolated from ground meat, and one was recovered from a nontreated water sample. All isolates were confirmed to be E. coli by standard biochemical assays. Slide and tube agglutination assays using O26 monovalent antiserum (Probac do Brasil, São Paulo, Brazil, and Federal Institute for Risk Assessment [BfR], Berlin, Germany) were performed for serogroup confirmation. Nonmotile (HNM) strains were investigated for the flagellar gene (fliC) by restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP)-PCR to allow serotype identification (41).

Prevalence of virulence markers.

The eae, pEAF, bfp, and ehxA sequences were detected by colony hybridization assays with specific DNA probes, as previously described (40). The primers and conditions employed in the PCR assays for identification of gene sequences related to efa1 (23), iha (22), saa (42), lpfAO113 (21), toxB (24), paa (25), katP (43), espP (43), espI (44), lpf (45), astA (46), ldaH (27), sheA (47), espC (48), and hlyA (49) were reported previously.

Prevalence of other gene markers.

The BioMark real-time PCR system (Fluidigm, San Francisco, CA) was used for high-throughput microfluidic real-time PCR amplification using the 48.48 Dynamic Array (Fluidigm). Amplifications were performed in accordance with the recommendations of the manufacturer, using EvaGreen DNA binding dye (Biotium Inc., Hayward, CA) followed by a melting-curve analysis with TaqMan gene expression master mix (Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France). The BioMark real-time PCR system was used with the following thermal profile: 95°C for 10 min (enzyme activation) followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min (amplification step). PCR amplifications were developed for detection of genes encoding Shiga toxins 1 and 2 (stx1 and stx2, respectively), intimin (eae, eae-alpha, eae-beta, eae-gamma, eae-epsilon, and eae-theta), an O26 group-associated protein (O26 wzx [wzxO26]), flagellar antigens H11 and H8 (fliCH11 and fliCH8), the iron uptake system (irp2 and fyuA), effector proteins translocated by the type III secretion system (EspG [espG], EspF1 [espF1], EspL2 [ent {or espL2}], NleB [nleB], NleE [nleE], NleH1-2 [nleH1-2], NleA [nleA], EfA1 [efa1], EspX1 [espX1], NleC [nleC], NleH1-1 [nleH1-1], EspN [espN], EspO1-1 [espO1-1], EspK [espK], NleG [nleG], NleG2 [nleG2], NleG6-1 [nleG6-1], EspR1 [espR1], NleG5-2 [nleG5-2], NleG6-2 [nleG6-2], EspJ [espJ], EspM2 [espM2], NleG8-2 [nleG8-2], EspB [espB], and EspX5 [espX5]), and a hypothetical protein encoded by ECs1822. The wecA gene was used as a reference genetic marker of E. coli (34).

Biochemical characterization.

The fermentative pattern of O26 strains was defined after bacterial cultivation at 37°C in medium containing 1.5% peptone, 0.002% bromocresol purple, and a 1% final concentration of the following carbohydrates: sucrose, raffinose, rhamnose, and dulcitol. The fermentative pattern was determined by daily observation of reactions until the seventh day.

Phylogenetic classification.

Phylogenetic groups (group A, B1, B2, or D) were determined according to the presence or absence of chuA and yjaA genes and the DNA fragment TspE4.C2 by using triplex PCR according to methods described previously by Clermont et al. (50), in which chuA+ yjaA+ strains are classified into group B2, chuA+ yjaA-negative strains are classified into group D, chuA-negative TspE4.C2+ strains are classified into group B1, and chuA-negative TspE4.C2-negative strains are classified into group A.

Assays of adherence to HeLa cells.

Adherence tests with HeLa cells grown on coverslips were performed according to methods described previously by Cravioto and coworkers (51), with some modifications. Cells were grown for 48 h (60 to 70% confluence) in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. After one wash with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4), 1.0 ml of fresh DMEM with 2% d-mannose was added to the cell monolayers, which were then infected with a 1:50 dilution of bacteria grown overnight in tryptic soy broth (TSB). After 3 h of incubation at 37°C, the preparations were washed three times with PBS and then incubated in fresh medium for an additional 3 h (6-h assay), followed by six washes with PBS. All preparations were fixed with methanol, stained with May Grünwald-Giemsa stain, and examined by light microscopy. The adherence patterns were classified as follows: localized adherence (LA), where the bacteria adhered to the cell surface as tight clusters; localized adherence-like (LAL), where the bacteria adhered to the cell surface, forming loose clusters; aggregative adherence (AA), where the bacteria adhered to the cell surface and to the coverslip in a stacked-brick pattern; and diffuse adherence (DA), where the bacteria adhered diffusely to the cell surface. E. coli strains E2348/69, C1845, and 042 (5, 52, 53) were used as controls for the LA, DA, and AA patterns, respectively. E. coli HB101 was used as the nonadherent (NA) control.

Analysis of the interaction of selected O26 strains with Caco-2 intestinal cells and human duodenal mucosa.

In vitro cell culture adhesion assays were performed with polarized and differentiated Caco-2 cells, which were grown in microplates using bicarbonate-buffered Eagle's minimum essential medium (Sigma) containing 20% newborn calf serum (NCS). Bacterial broth cultures grown overnight were diluted 1:50 in culture medium and incubated with cells for 6 h at 37°C. Cells were carefully washed to remove nonadherent bacteria and fixed in glutaraldehyde prior to preparation for microscopic examination. Cultured human intestinal mucosa assays were performed essentially as previously described (54). The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), and patients gave informed consent to be included in the study. Briefly, duodenal mucosa biopsy specimens were taken from adult patients undergoing endoscopy, and fragments were transported in ice-cold NCTC 135 medium (Sigma) with 200 μg/ml gentamicin and washed in antibiotic-free medium. For each strain tested, two fragments from different patients were used. Biopsy fragments were placed onto sterile filters (AP15; Millipore) in plastic petri dishes (35 by 10 mm; Corning) containing organ culture medium described previously by Embaye et al. (55) and 1% d-mannose (Sigma). After incubation for 15 min at 37°C in an incubator with 95% O2–5% CO2, 200 μl of bacterial culture was added to the samples. Following an incubation period of 2 h under the same conditions, samples were washed in NCTC 135 medium and incubated with 5 ml of antibiotic-free organ culture medium for an additional 6 h and with antibiotic for an additional 10 or 16 h under the conditions described above. Subsequently, the biopsy samples were washed and fixed prior to processing for scanning electron microscopy (SEM) or transmission electron microscopy (TEM). For SEM, glutaraldehyde-fixed specimens were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and critical-point dried. Samples were mounted onto SEM stubs, coated with gold, and examined with a JEOL JSM-5300 instrument operated at 25 kV. For TEM, samples were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M PBS, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series and propylene oxide solutions, and embedded in Araldite resin. Ultrathin sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined with a JEOL 1200 EX-II instrument operated at 80 kV.

RESULTS

Biochemical and genetic characterization of O26 isolates.

In this study, we examined a collection of E. coli O26 strains isolated in Brazil, which were previously characterized as non-Shiga-toxin-producing strains (18; our unpublished data). All strains were confirmed to be O26 strains by seroagglutination, except for 10 isolates that were rough. PCR demonstrated that all isolates, including the rough strains, harbored the wzxO26 and wzyO26 genes. On the basis of serotyping, most of the strains showed H11 (n = 20), followed by H32 (n = 10) and H8 (n = 1), and 13 were HNM. The HNM strains were analyzed for fliC, where 2 isolates showed H11 and 11 isolates showed H8. Therefore, in the present study, 22 isolates showing H11, 12 showing H8, and 10 showing H32 were enrolled (Table 1).

Table 1.

Association of genetic markers with different serotypes of E. coli O26

| Genetic marker | % (no.) of strains associated with group |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| H11 (n = 22) | H8 (n = 12) | H32 (n = 10) | |

| wzxO26 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| fliCH11 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| fliCH8 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| eae | 100 | 100 | 0 |

| eae-beta | 100 | 33.3 (4) | 0 |

| pEAF | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| bfp | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| stx1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| stx2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| espK | 50 (11) | 100 | 0 |

| espN | 31.8 (7) | 75 (9) | 0 |

| espP | 27.2 (6) | 0 | 0 |

| ehxA | 22.7 (5) | 0 | 0 |

| espI | 13.6 (3) | 0 | 10 (1) |

| katP | 4.5 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| irp2 | 100 | 67 (8) | 0 |

| fyuA | 100 | 67 (8) | 0 |

| etpD | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| nleF | 86.3 (19) | 100 | 0 |

| nleH1-2 | 95.4 (21) | 16.7 (2) | 0 |

| nleA | 91 (20) | 83.3 (10) | 0 |

| ent | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| nleB | 100 | 0 | 10 (1) |

| nleE | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| pagC | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| nleH1-1 | 100 | 25 (3) | 0 |

| nleD2 | 0 | 33.3 (4) | 0 |

| nleG | 81.8 (18) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| efa1 | 100 | 33.3 (4) | 0 |

| efa2 | 100 | 66.7 (8) | 0 |

| iha | 50 (11) | 75(9) | 0 |

| paa | 81.8 (18) | 0 | 0 |

| lpfAO113 | 27.2 (6) | 8.3 (1) | 0 |

| lpfA | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| toxB | 22.7 (5) | 0 | 0 |

| ldaH | 31.8 (72) | 0 | 10 (1) |

| saa | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| astA | 18.2 (4) | 25 (3) | 0 |

| espV | 0 | 75 (9) | 0 |

| terE | 86.3 (19) | 33.3 (4) | 0 |

| ureD | 54.5 (12) | 0 | 0 |

| hlyA | 13.6 (3) | 0 | 0 |

| sheA | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| espM1 | 81.8 (18) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| espM2 | 86.3 (19) | 16.7 (2) | 10 (1) |

| espX2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| espX7 | 31.8 (7) | 66.7 (8) | 0 |

| espO1-1 | 0 | 66.7 (8) | 0 |

| espY4-2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| espX6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| espW | 86.3 (19) | 0 | 0 |

| espG | 95.4 (21) | 100 (12) | 0 |

| espF1 | 91 (20) | 91.6 (11) | 90 (9) |

| espX1 | 100 (22) | 100 | 90 (9) |

| espY1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| espY3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| espR1 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| espJ | 100 | 33.3 (4) | 0 |

| ECs1822 | 86.3 (19) | 0 | 0 |

| ECs1763 | 86.3 (19) | 8.3 (1) | 0 |

All isolates, except those of serotype O26:H32, were originally classified as aEPEC, as they carried eae but lacked pEAF and the bfpA genes of the tEPEC pathotype. The results obtained in the search of 59 genetic markers by PCR and high-throughput PCR approaches are shown in Table 1. We observed that 50% of the O26:H11 (n = 11) and all of the O26:H8 strains tested positive for espK, therefore discriminating them as stx-negative EHEC derivatives (Table 2). The espN gene occurred in 63.6% and 75% of O26:H11 and O26:H8 stx-negative EHEC derivative isolates, respectively, whereas the espF1, espX1, espR1, and sheA genes occurred at a high frequency among all O26 isolates. None of the O26 strains carried the lpfA, saa, etpD, pagC, espX2, espY4-2, espX6, espY1, and espY3 genes. Only a few genes, including ldaH, espI, nleB, and espM2, were identified among 10% of the O26:H32 isolates, mostly those isolated from meat samples (Table 1).

Table 2.

Genotypic and phenotypic characteristics of O26 isolates

| Strain | Ora | H type | Virulence marker(s) |

Adhesionb | FPd |

PGe | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O island |

Adhesin | Virulence plasmid | Additional | S/RF | RH/D | ||||||

| 71 | 122 | ||||||||||

| EHEC derivatives | |||||||||||

| 1.84 | DC | H8 | nleF, nleA | eae, efa2, iha | irp2, fyuA | NA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | ||

| 2361-4/85 | DC | H8 | nleF, nleA | eae, efa2 (lif), iha | espV, irp2, fyuA | DA | +/+ | +/− | B1 | ||

| 234-1 CII | DC | H8 | nleF, nleA | eae, efa1, efa2 (lif), iha | irp2, fyuA | LAL | +/+ | −/+ | B1 | ||

| 32Fe/2 vera | DC | H8 | nleF, nleA | eae, efa2, iha | astA, espV, irp2, fyuA | LAL | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | ||

| 1-84/RJ | DC | H8 | nleF, nleA | eae, efa1, efa2 (lif), iha | espV, irp2, fyuA | NA | +/+ | +/− | B1 | ||

| 3561-2 | DC | H8 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae, efa1, efa2, iha | espV, irp2, fyuA | DA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | |

| 54/82 HC | DC | H8 | nleF, nleA | eae, efa2, iha | espV, irp2, fyuA | LAL | +/+ | +/− | B1 | ||

| 14-1 CII | CC | H8 | nleF, nleA | eae, efa1, efa2 (lif), iha | irp2, fyuA | LA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | ||

| 3282-7 | CC | H8 | nleF | eae-beta | terE, astA, espV | NA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | ||

| 387-8 CII | DC | H8 | nleF, nleH1-2 | eae-beta, iha | terE, espV | LAL | +/+ | +/− | B1 | ||

| 200/82 HSP | DC | H8 | nleF, nleH1-2 | eae-beta | terE, nleD-2, astA, espV | DA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | ||

| 3280-7/86 | CC | H8 | nleF | eae-beta, lpfAO113 | terE, nleD-2, espV | NA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | ||

| O26 TR EPM | DC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), iha, paa, lpfAO113, toxB | ehxA, espP, katP | ureD, terE, hlyA, irp2, fyuA | LAL | +/+ | −/− | B1 |

| 0791-1/85c | DC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), iha, paa, lpfAO113 | espP | ureD, terE, irp2, fyuA | NA | +/+ | −/− | B1 |

| 1971-1/85c | DC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), iha, paa, ldaH | ureD, terE, irp2, fyuA | LA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | |

| 72-B/87 | DC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), iha, paa | espI | ureD, terE, irp2, fyuA | LA | +/+ | +/− | B1 |

| 3561-2/86 | DC | H11 | nleF, nleA | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), iha, paa, lpfAO113 | ureD, terE, irp2, fyuA | DA | +/+ | +/− | B1 | ||

| 1551-3/85c | DC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), iha, paa | ureD, terE, irp2, fyuA | DA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | |

| 7-81 HSJ | DC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), iha, paa | ureD, terE, irp2, fyuA | LAL | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | |

| 3451-3/86 | DC | H11 | nleF, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), iha, paa | ehxA, espP, espI | ureD, terE, hlyA, irp2, fyuA | NA | +/+ | −/− | B1 |

| 2911-2/84 | DC | H11 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), iha, paa, toxB | ehxA, espP | ureD, terE, astA, irp2, fyuA | NA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | |

| 93-81 HSP | DC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), iha, toxB | ehxA, espP, espI | ureD, terE, hlyA, irp2, fyuA | LA/DA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 |

| 2012-1 (2) | CC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), iha, paa, toxB, ldaH | ehxA, espP | ureD, terE, astA, irp2, fyuA | LAL | +/+ | +/+ | B1 |

| aEPEC | |||||||||||

| 4851-3/86 | DC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), paa, toxB, ldaH | terE, irp2, fyuA | LAL | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | |

| H2 | DC | H11 | nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif) | irp2, fyuA | LA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | |

| 2271-1/85 | DC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), paa, ldaH | terE, irp2, fyuA | LAL | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | |

| 25623 | DC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), paa | terE, astA, irp2, fyuA | LAL | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | |

| 277-2 CII | DC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), paa | terE, irp2, fyuA | LA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | |

| 316-10 CII | DC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), paa | ureD, terE, irp2, fyuA | AA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | |

| 324-1 CII | CC | H11 | nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 | irp2, fyuA | LA | +/+ | +/+ | A | |

| 2010-1/85 | CC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), paa, lpfAO113, ldaH | terE, irp2, fyuA | LA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | |

| 2490-1/85 | CC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), paa, lpfAO113, ldaH | terE, irp2, fyuA | LA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | |

| 2492-1 | CC | H11 | nleF, nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), paa, ldaH | terE, astA, irp2, fyuA | LAL | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | |

| 1C50 | MM | H11 | nleA, nleH1-2 | nleB, ent, nleE | eae-beta, efa1, efa2 (lif), lpfAO113 | irp2, fyuA | DA | +/+ | +/+ | B1 | |

| Avirulent | |||||||||||

| 268-10 CII | CC | H32 | NA | −/− | +/+ | A | |||||

| 17354-2/84 | NTW | H32 | ldaH | espI | NA | −/− | +/+ | A | |||

| 2C27 | MM | H32 | NA | −/− | +/+ | A | |||||

| 3C21 | MM | H32 | NA | −/− | +/+ | A | |||||

| 4C2 | MM | H32 | NA | −/− | +/+ | A | |||||

| 4C27 | MM | H32 | NA | −/− | +/+ | A | |||||

| 6K10 | MM | H32 | NA | −/− | +/+ | A | |||||

| 6K60 | MM | H32 | nleB | NA | −/− | +/+ | A | ||||

| 6C41 | MM | H32 | NA | −/− | +/+ | A | |||||

| 1K10 | MM | H32 | NA | −/− | +/+ | A | |||||

Or, strain origin; DC, diarrheic child; CC, control child; MM, minced meat; NTW, nontreated water.

Adhesion patterns on HeLa cells. LA, localized adherence; LAL, localized adherence-like; AA, aggregative adherence; DA, diffuse adherence; NA, nonadherent.

Isolate analyzed by its host cell interactions and TEM.

FP, fermentation pattern; S/RF, sucrose/raffinose; R/D, rhamnose/dulcitol; +, positive reaction; −, negative reaction.

PG, phylogenetic group.

Concerning O islands, the genes contained in OI-71 (nleF, nleH1-2, and nleA) were very common in all H11 and H8 O26 isolates, except for nleH1-2, which occurred in 16% of H8 isolates. The presence of a complete OI-122 (ent, nleB, nleE, and pagC) was not observed, but the ent, nleB, and nleE genes were identified in all H11 strains. Occurrence of HPI genes (irp2 and fyuA) was observed in all O26:H11 and in 67% of O26:H8 isolates (Table 1).

The presence of the virulence plasmid genes (ehxA, espP, espI, etpD, and katP) was identified in 7 of the 11 (64%) O26:H11 EHEC derivative isolates, with the exception of etpD (Table 1). The different virulence profiles observed among the O26 isolates are presented in Table 2. Interestingly, the paa, espM1, espW, toxB, ureD, and ECs1822 genes were associated with almost all H11 isolates. The presence of the hlyA gene was identified in only three O26:H11 isolates, whereas espV, espO1-1, and nleD occurred only among the O26:H8 isolates. In addition, only the stx-negative EHEC derivative isolates tested positive for iha (75% of H8 and 100% of H11 isolates).

Analysis of the fermentative pattern showed that except for the O26:H32 avirulent strains, all aEPEC and stx-negative EHEC derivative isolates fermented sucrose and raffinose. On the other hand, all aEPEC and avirulent strains and 56% (13/23) of the stx-negative EHEC derivative O26 strains fermented rhamnose and dulcitol (Table 2). Three stx-negative EHEC O26:H11 derivative isolates (0791-1/85, O26TR EPM, and 3451-3/86) fermented neither rhamnose nor dulcitol.

Determination of phylogenetic groups showed that all stx-negative EHEC derivatives and aEPEC isolates belonged to the B1 group, except for one O26:H11 aEPEC isolate (324-1 CII). All nonpathogenic O26:H32 strains belonged to the A group (Table 2).

In relation to adhesion, none of the O26:H32 strains adhered to HeLa cells, but a diversity of adherence patterns was identified among the stx-negative EHEC derivatives and aEPEC strains. Eleven and nine of the 34 EHEC derivatives and aEPEC isolates displayed LAL (32%) or LA (26.5%), respectively, in 6-h assays. In addition, six (17.6%) of the strains showed DA, and nonadherence to the cells was observed for six (17.6%) strains (Table 2).

Analysis of the interactions of O26 strains with Caco-2 intestinal cells and biopsy specimens of human duodenal mucosa.

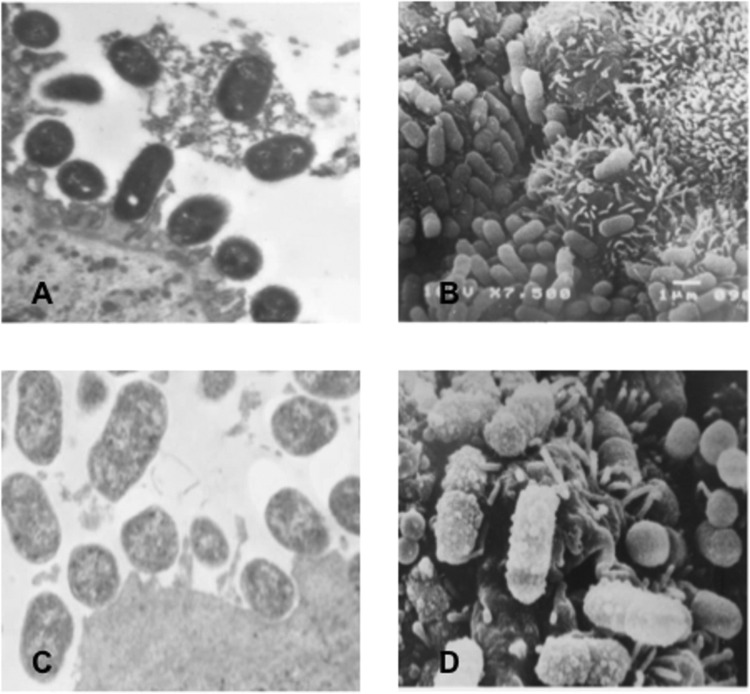

Three stx-negative EHEC O26:H11 derivative strains (0791-1/85, 1551-3/85, and 1971-1/85) isolated from children with acute diarrhea, each exhibiting a distinct adherence pattern, were selected for further analysis of their potential to interact with human enterocytes. Although one strain was nonadherent to HeLa cells (0791-1/85), all strains adhered to and caused A/E lesions (fluorescent-actin staining [FAS] positivity) in differentiated Caco-2 cells (not shown), despite the fact that their adherence patterns were not maintained. However, only two (1551-3/85 and 1971-1/85) of the three strains adhered to and displayed pedestal formation in duodenal mucosa ex vivo (Fig. 1A and B). The remaining strain (0791-1/85) showed loosely adherent bacteria and no true pedestals (Fig. 1C and D).

Fig 1.

(A) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) of human duodenal mucosa infected with an O26:H11 strain (1551-3/85), showing attachment-effacement lesions comprised of closely attached bacteria accompanied by alterations to the enterocyte cytoskeleton, evidenced by cupping, pedestal formation, accumulation of electron-dense material, and an absence of microvilli at sites of bacterial attachment. Magnification, ×12,500. (B) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of human duodenal mucosa infected with an O26:H11 strain (1551-3/85) confirms the occurrence of bacterial colonization of the mucosal surface. Magnification, ×9,940. (C and D) TEM and SEM views of human duodenal mucosa ex vivo infected with an O26:H11 strain (0791-1/85), showing bacterial adhesion but without true pedestal formation. Magnification, ×12,120 (C) and ×11,310 (D).

DISCUSSION

An understanding of virulence genes present in the E. coli O26 group may help to avoid misclassification of different pathotypes, which has important implications for public health surveillance. In the present study, the O26 isolates originally classified as aEPEC were discriminated as stx-negative EHEC derivatives on the basis of the presence of the espK gene. These results confirmed previous observations of the absence of espK in aEPEC O26:H11 and nonpathogenic O26:H32 isolates (34). Moreover, the presence of espK in all O26:H8 strains isolated in Brazil, mostly from children suffering from diarrhea, provides evidence to consider them stx-negative EHEC derivatives. The importance of classifying O26 isolates as EHEC derivatives relies on the severity of the diseases that can be associated with EHEC infections compared to those usually caused by aEPEC.

Several virulence plasmid-borne genes were also identified in a set of the O26:H11 stx-negative EHEC derivative isolates studied here. In fact, this result reinforces the suggestion that these strains may have been derived from EHEC strains that lost stx genes. Indeed, previous findings have shown that stx-negative/eae-positive E. coli O26:H11/NM strains can be converted to EHEC by transduction with stx phages (56). Furthermore, the conversion of EHEC to stx-negative EHEC derivatives over time has also been observed in follow-up studies of patients with HUS (57). The occurrence of the HPI genes irp2 and fyuA, previously reported to be conserved among O26:H11/NM EHEC and aEPEC strains (33), was identified in all O26:H11 and in most O26:H8 stx-negative EHEC derivatives presently studied, thus also consistent with the suggestion that these stx-negative isolates may have been derived from EHEC.

The incomplete versions of PAI O122 (efa [lifA], nleB, ent, and nleE genes) identified in the present study were also found in O26:HNM aEPEC strains (58) and O26 EHEC strains as well as in several stx-negative O26 E. coli strains associated with HUS (33), thus suggesting a role of this PAI in the virulence of O26 stx-negative isolates. Taking into account additional virulence markers, we observed that the adhesin-encoding gene iha is characteristic of stx-negative EHEC derivative strains, while the paa gene in combination with other markers may help to identify the O26:H11 serotype, as this gene was previously shown to be found much more frequently in aEPEC strains isolated from diarrheic children (59, 60). Only a few genes, including ldaH, espI, nleB, and espM2, were identified in the O26:H32 isolates in the present study, corroborating previous findings that they belong to a different clonal group and apparently comprise avirulent strains (12, 13). Indeed, the H32 strains analyzed can also be separated into a cluster and are genetically different from the H11 and H8 strains by simple matching analysis by RFLP (H. O. Saridakis, personal communication).

Leomil et al. (20), in studying 23 E. coli O26:H11/HNM isolates, defined two groups of genetically closely related strains on the basis of their carbohydrate fermentation patterns. One group was formed by aEPEC and EHEC, which do not ferment rhamnose and dulcitol and most of which carry a plasmid encoding enterohemolysin. The other group consisted of rhamnose- and dulcitol-fermenting aEPEC strains, which carry plasmids encoding alpha-hemolysin. In fact, as described above, all the O26:H11 aEPEC strains analyzed here were rhamnose and dulcitol fermenters, but none of them carried the alpha-hemolysin gene. On the contrary, rhamnose- and dulcitol-fermenting isolates also occurred among the stx-negative O26 EHEC derivative isolates studied here. Nevertheless, the only three isolates identified that did not ferment rhamnose and dulcitol showed plasmid-associated virulence genes for enterohemolysin (ehxA) and serine protease (espP), a finding similar to that reported by Leomil et al. (20), and occurred among the O26:H11 stx-negative EHEC derivative isolates.

Knowledge of the genomic background of E. coli may have implications in understanding the ability of bacteria to integrate and express different virulence factors. A link between phylogeny and virulence has also been observed among intestinal pathogens (61). Phylogenetic analyses have shown that pathogenic E. coli strains fall into groups B1, B2, and D, whereas most commensal strains belong to group A (50). As expected, all avirulent O26 strains belonged to the A group, and interestingly, most of them were isolated from ground meat. On the other hand, except for one isolate, all stx-negative EHEC derivative and aEPEC isolates carrying several of the virulence factors studied belonged to the B1 group, and most were isolated from diarrheic children. The classification of O26 aEPEC and EHEC isolates into the B1 group has also been described by others (62, 63).

The adhesion patterns identified in this study among O26 aEPEC and EHEC derivatives were comparable to those observed by other authors who found LAL to be the most frequent adherence pattern, whereas AA, DA, and NA occurred at different frequencies (9, 40, 64), thus suggesting that the adherence pattern is also a very variable characteristic among O26 isolates. Regardless of the distinct adherence pattern shown by the three selected O26:H11 strains in HeLa cells, all were FAS positive in polarized intestinal Caco-2 cells, and adherence to human duodenal mucosa ex vivo was observed. However, the NA strain (0791-1/85) was apparently much less efficient in such interactions. Why this strain did not produce A/E lesions in human enterocytes ex vivo remains to be clarified.

Considering the current knowledge of the characteristics of the O26 serogroup, a valuable picture of the gene signature and phenotypic features of stx-negative O26 isolates is presented in this study. While O26 EHEC derivatives were found to carry most of the virulence markers studied, very few genes and nonadherence properties were identified in the O26:H32 avirulent group. Moreover, as several of the isolates studied were rough or nonmotile, the genetic approaches used were extremely advantageous, which resulted in the first description of O26 strains belonging to the H8 serotype. It would be interesting to know if the aEPEC O26 isolates so far described in the literature also include some stx-negative EHEC derivative isolates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) awarded to R.M.F.P., B.E.C.G., and T.A.T.G. L.B.R. is the recipient of a FAPESP fellowship.

We thank Kathelin Lascowski for technical assistance. A. Leyva helped with English editing of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 23 August 2013

REFERENCES

- 1.Frankel G, Phillips AD, Rosenshine I, Dougan G, Kaper JB, Knutton S. 1998. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: more subversive elements. Mol. Microbiol. 30:911–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen HD, Frankel G. 2005. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: unravelling pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29:83–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jerse AE, Yu J, Tall BD, Kaper JB. 1990. A genetic locus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli necessary for the production of attaching and effacing lesions on tissue culture cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:7839–7843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaper JB. 1996. Defining EPEC. Rev. Microbiol. 27:130–133 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nataro JP, Baldini MM, Kaper JB, Black RE, Bravo N, Levine MM. 1985. Detection of an adherence factor of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli with a DNA probe. J. Infect. Dis. 152:560–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sohel I, Puente JL, Murray WJ, Vuopio-Varkila J, Schoolnik GK. 1993. Cloning and characterization of the bundle-forming pilin gene of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and its distribution in Salmonella serotypes. Mol. Microbiol. 7:563–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trabulsi LR, Keller R, Gomes TAT. 2002. Typical and atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:508–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernandes RT, Elias WP, Vieira AM, Gomes TAT. 2009. An overview of atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 297:137–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abe CM, Trabulsi LR, Blanco J, Blanco M, Dahbi G, Blanco JE, Mora A, Franzolin MR, Taddei CR, Martinez MB, Piazza RMF, Elias WP. 2009. Virulence features of atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli identified by the eae+ EAF-negative stx- genetic profile. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 64:357–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nara JM, Cianciarullo AM, Culler HF, Bueris V, Horton DSPQ, Menezes MA, Franzolin MR, Elias WP, Piazza RMF. 2010. Differentiation of typical and atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli using colony immunoblot for detection of bundle-forming pilus expression. J. Appl. Microbiol. 109:35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peixoto JCC, Bando SY, Ordoñez JAG, Botelho BA, Trabulsi LR, Moreira-Filho CA. 2001. Genetic differences between Escherichia coli O26 strains isolated in Brazil and in other countries. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 196:239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miko A, Lindstedt BA, Brandal LT, Løbersli I, Beutin L. 2010. Evaluation of multiple-locus variable number of tandem-repeats analysis (MLVA) as a method for identification of clonal groups among enteropathogenic, enterohaemorrhagic and avirulent Escherichia coli O26 strains. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 303:137–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bugarel M, Martin A, Fach P, Beutin L. 2011. Virulence gene profiling of enterohemorrhagic (EHEC) and enteropathogenic (EPEC) Escherichia coli strains: a basis for molecular risk assessment of typical and atypical EPEC strains. BMC Microbiol. 11:142. 10.1186/1471-2180-11-142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkins C, Evans J, Chart H, Willshaw GA, Frankel G. 2008. Escherichia coli serogroup O26—a new look at an old adversary. J. Appl. Microbiol. 104:14–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vaz TM, Irino K, Kato MA, Dias AM, Gomes TAT, Medeiros ML, Rocha MM, Guth BEC. 2004. Virulence properties and characteristics of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in São Paulo, Brazil, from 1976 through 1999. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:903–905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guth BEC, Lopes de Souza R, Vaz TM, Irino K. 2002. First Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolate from a patient with hemolytic uremic syndrome, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8:535–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silva MLM, Scaletsky ICA, Viotto LH. 1983. Non-production of cytotoxin among enteropathogenic strains of Escherichia coli isolated in São Paulo, Brazil. Rev. Microbiol. 14:161–162 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saridakis HO. 1994. Non production of Shiga-like toxins by Escherichia coli serogroup O26. Rev. Microbiol. 25:154–155 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whittam TS, Wolfe ML, Wachsmuth IK, Orskov F, Orskov I, Wilson RA. 1993. Clonal relationships among Escherichia coli strains that cause hemorrhagic colitis and infantile diarrhea. Infect. Immun. 61:1619–1629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leomil L, Pestana de Castro AF, Krause G, Schmidt H, Beutin L. 2005. Characterization of two major groups of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli O26 strains which are globally spread in human patients and domestic animals of different species. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 249:335–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doughty S, Sloan J, Bennett-Wood V, Robertson M, Robins-Browne RM, Hartland EL. 2002. Identification of a novel fimbrial gene cluster related to long polar fimbriae in locus of enterocyte effacement-negative strains of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 70:6761–6769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tarr PI, Bilge SS, Vary JC, Jr, Jelacic S, Habeeb RL, Ward TR, Baylor MR, Besser TE. 2000. Iha: a novel Escherichia coli O157:H7 adherence-conferring molecule encoded on a recently acquired chromosomal island of conserved structure. Infect. Immun. 68:1400–1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nicholls L, Grant TH, Robins-Browne RM. 2000. Identification of a novel genetic locus that is required for in vitro adhesion of a clinical isolate of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli to epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 35:275–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tatsuno I, Horie M, Abe H, Miki T, Makino K, Shinagawa H, Taguchi H, Kamiya S, Hayashi T, Sasakawa C. 2001. toxB gene on pO157 of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 is required for full epithelial cell adherence phenotype. Infect. Immun. 69:6660–6669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Batisson I, Guimond MP, Girard F, An H, Zhu C, Oswald E, Fairbrother JM, Jacques M, Harel J. 2003. Characterization of the novel factor paa involved in the early steps of the adhesion mechanism of attaching and effacing Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 71:4516–4525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.An H, Fairbrother JM, Desautels C, Harel J. 1999. Distribution of a novel locus called Paa (porcine attaching and effacing associated) among enteric Escherichia coli. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 473:179–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scaletsky IC, Michalski J, Torres AG, Dulguer MV, Kaper JB. 2005. Identification and characterization of the locus for diffuse adherence, which encodes a novel afimbrial adhesin found in atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 73:4753–4765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bardiau M, Labrozzo S, Mainil JG. 2009. Putative adhesins of enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli of serogroup O26 isolated from humans and cattle. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:2090–2096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brunder W, Schmidt H, Frosch M, Karch H. 1999. The large plasmids of Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) are highly variable genetic elements. Microbiology 145:1005–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang WL, Bielaszewska M, Bockemuhl J, Schmidt H, Scheutz F, Karch H. 2000. Molecular analysis of H antigens reveals that human diarrheagenic Escherichia coli O26 strains that carry the eae gene belong to the H11 clonal complex. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2989–2993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bielaszewska M, Zhang W, Tarr PI, Sonntag AK, Karch H. 2005. Molecular profiling and phenotype analysis of Escherichia coli O26:H11 and O26:NM: secular and geographic consistency of enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:4225–4228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karch H, Schubert S, Zhang D, Zhang W, Schmidt H, Olschläger T, Hacker J. 1999. A genomic island, termed high-pathogenicity island, is present in certain non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli clonal lineages. Infect. Immun. 67:5994–6001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bielaszewska M, Sonntag AK, Schmidt MA, Karch H. 2007. Presence of virulence and fitness gene modules of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli O26. Microbes Infect. 9:891–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bugarel M, Beutin L, Scheutz F, Loukiadis E, Fach P. 2011. Identification of genetic markers for differentiation of Shiga toxin-producing, enteropathogenic, and avirulent strains of Escherichia coli O26. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:2275–2281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang WL, Bielaszewska M, Liesegang A, Tschape H, Schmidt H, Bitzan M, Karch H. 2000. Molecular characteristics and epidemiological significance of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O26 strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:2134–2140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dulguer MV, Fabbricotti SH, Bando SY, Moreira-Filho CA, Fagundes-Neto U, Scaletsky ICA. 2003. Atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains: phenotypical and genetic profiling reveals a strong association between enteroaggregative E. coli heat-stable enterotoxin and diarrhea. J. Infect. Dis. 188:1685–1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gomes TAT, Irino K, Girão DM, Girão VBC, Guth BEC, Vaz TMI, Moreira FC, Chinarelli SH, Vieira MAM. 2004. Emerging enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains? Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1851–1855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pelayo JS, Scaletsky ICA, Pedroso MZ, Sperandio V, Girón JA, Frankel G, Trabulsi LR. 1999. Virulence properties of atypical EPEC strains. J. Med. Microbiol. 48:41–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robins-Browne RM, Bordun AM, Tauschek M, Bennett-Wood VR, Russell J, Oppedisano F, Lister NA, Bettelheim KA, Fairley CK, Sinclair MI, Hellard ME. 2004. Escherichia coli and community-acquired gastroenteritis, Melbourne, Australia. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 10:1797–1805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vieira MAM, Andrade JRC, Trabulsi LR, Rosa ACP, Dias AMG, Ramos SRTS, Frankel G, Gomes TAT. 2001. Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of Escherichia coli strains of non-enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) serogroups that carry eae and lack the EPEC adherence factor and Shiga toxin DNA probe sequences. J. Infect. Dis. 183:762–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Machado J, Grimont F, Grimont PA. 2000. Identification of Escherichia coli flagellar types by restriction of the amplified fliC gene. Res. Microbiol. 151:535–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paton AW, Srimanote P, Woodrow MC, Paton JC. 2001. Characterization of Saa, a novel autoagglutinating adhesin produced by locus of enterocyte effacement-negative Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli strains that are virulent for humans. Infect. Immun. 69:6999–7009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beutin L, Strauch E, Zimmermann S, Kaulfuss S, Schaudinn C, Mannel A, Gelderblom HR. 2005. Genetical and functional investigation of fliC genes encoding flagellar serotype H4 in wildtype strains of Escherichia coli and in a laboratory E. coli K-12 strain expressing flagellar antigen type H48. BMC Microbiol. 5:4. 10.1186/1471-2180-5-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmidt H, Zhang WL, Hemmrich U, Jelacic S, Brunder W, Tarr PI, Dobrindt U, Hacker J, Karch H. 2001. Identification and characterization of a novel genomic island integrated at selC in locus of enterocyte effacement-negative, Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 69:6863–6873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torres AG, Kanack KJ, Tutt CB, Popov V, Kaper JB. 2004. Characterization of the second long polar (LP) fimbriae of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and distribution of LP fimbriae in other pathogenic E. coli strains. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 238:333–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamamoto T, Nakazawa M. 1997. Detection and sequences of the enteroaggregative Escherichia coli heat-stable enterotoxin 1 gene in enterotoxigenic E. coli strains isolated from piglets and calves with diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:223–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kerényi M, Allison HE, Bátai I, Sonnevend A, Emödy L, Plaveczky N, Pál T. 2005. Occurrence of hlyA and sheA genes in extraintestinal Escherichia coli strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:2965–2968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Restieri C, Garriss G, Locas MC, Dozois CM. 2007. Autotransporter-encoding sequences are phylogenetically distributed among Escherichia coli clinical isolates and reference strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:1553–1562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Magalhães CA, Rossato SS, Barbosa AS, dos Santos TO, Elias WP, Sircili MP, Piazza RMF. 2011. The ability of haemolysins expressed by atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to bind to extracellular matrix components. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 106:146–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Bingen E. 2000. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:4555–4558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cravioto A, Gross RJ, Scotland SM, Rowe B. 1979. An adhesive factor found in strains of Escherichia coli belonging to the traditional infantile enteropathogenic serotypes. Curr. Microbiol. 3:95–99 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levine MM. 1987. Escherichia coli that cause diarrhea: enterotoxigenic, enteropathogenic, enteroinvasive, enterohemorrhagic, and enteroadherent. J. Infect. Dis. 155:377–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bilge SS, Clausen CR, Lau W, Moseley SL. 1989. Molecular characterization of a fimbrial adhesin, F1845, mediating diffuse adherence of diarrhea-associated Escherichia coli to HEp-2 cells. J. Bacteriol. 171:4281–4289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pedroso MZ, Freymüller E, Trabulsi LR, Gomes TAT. 1993. Attaching-effacing lesions and intracellular penetration in HeLa cells and human duodenal mucosa by two Escherichia coli strains not belonging to the classical enteropathogenic E. coli serogroups. Infect. Immun. 61:1152–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Embaye H, Batt RM, Saunders JR, Getty B, Hart CA. 1989. Interaction of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli 0111 with rabbit intestinal mucosa in vitro. Gastroenterology 96:1079–1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bielaszewska M, Prager R, Köck R, Mellmann A, Zhang W, Tschäpe H, Tarr PI, Karch H. 2007. Shiga toxin gene loss and transfer in vitro and in vivo during enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O26 infection in humans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3144–3150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bielaszewska M, Köck R, Friedrich AW, von Eiff C, Zimmerhackl LB, Karch H, Mellmann A. 2007. Shiga toxin-mediated hemolytic uremic syndrome: time to change the diagnostic paradigm? PLoS One 2:e1024. 10.1371/journal.pone.0001024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vieira MA, Salvador FA, Silva RM, Irino K, Vaz TM, Rockstroh AC, Guth BE, Gomes TAT. 2010. Prevalence and characteristics of the O122 pathogenicity island in typical and atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 48:1452–1455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Afset JE, Bruant G, Brousseau R, Harel J, Anderssen E, Bevanger L, Bergh K. 2006. Identification of virulence genes linked with diarrhea due to atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli by DNA microarray analysis and PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44:3703–3711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scaletsky IC, Aranda KR, Souza TB, Silva NP, Morais MB. 2009. Evidence of pathogenic subgroups among atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47:3756–3759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Escobar-Páramo P, Clermont O, Blanc-Potard AB, Bui H, Le Bouguénec C, Denamur E. 2004. A specific genetic background is required for acquisition and expression of virulence factors in Escherichia coli. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21:1085–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bando SY, Andrade FB, Guth BEC, Elias WP, Moreira-Filho CA, Castro AFP. 2009. Atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli genomic background allows the acquisition of non-EPEC virulence factors. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 299:22–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Contreras CA, Ochoa TJ, Ruiz J, Lacher DW, Rivera FP, Saenz Y, Chea-Woo E, Zavaleta N, Gil AI, Lanata CF, Huicho L, Maves RC, Torres C, DebRoy C, Cleary TG. 2011. Phylogenetic relationships of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from Peruvian children. J. Med. Microbiol. 60:639–646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mora A, Blanco M, Yamamoto D, Dahbi G, Blanco JE, López C, Alonso MP, Vieira MAM, Hernandes RT, Abe CM, Piazza RMF, Lacher DW, Elias WP, Gomes TAT, Blanco J. 2009. HeLa-cell adherence patterns and actin aggregation of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) and Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) strains carrying different eae and tir alleles. Int. Microbiol. 12:243–251 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]