Abstract

FeaR is an AraC family regulator that activates transcription of the tynA and feaB genes in Escherichia coli. TynA is a periplasmic topaquinone- and copper-containing amine oxidase, and FeaB is a cytosolic NAD-linked aldehyde dehydrogenase. Phenylethylamine, tyramine, and dopamine are oxidized by TynA to the corresponding aldehydes, releasing one equivalent of H2O2 and NH3. The aldehydes can be oxidized to carboxylic acids by FeaB, and (in the case of phenylacetate) can be further degraded to enter central metabolism. Thus, phenylethylamine can be used as a carbon and nitrogen source, while tyramine and dopamine can be used only as sources of nitrogen. Using genetic, biochemical and computational approaches, we show that the FeaR binding site is a TGNCA-N8-AAA motif that occurs in 2 copies in the tynA and feaB promoters. We show that the coactivator for FeaR is the product rather than the substrate of the TynA reaction. The feaR gene is upregulated by carbon or nitrogen limitation, which we propose reflects regulation of feaR by the cyclic AMP receptor protein (CRP) and the nitrogen assimilation control protein (NAC), respectively. In carbon-limited cells grown in the presence of a TynA substrate, tynA and feaB are induced, whereas in nitrogen-limited cells, only the tynA promoter is induced. We propose that tynA and feaB expression is finely tuned to provide the FeaB activity that is required for carbon source utilization and the TynA activity required for nitrogen and carbon source utilization.

INTRODUCTION

In Escherichia coli, TynA is a periplasmic amine oxidase containing copper and topaquinone cofactors (1). Aromatic amines, including phenylethylamine (PEA), tyramine, and dopamine, are oxidized by TynA to the corresponding aldehydes, in a reaction that releases one equivalent of H2O2 and NH3 (Fig. 1A). Therefore, these monoamines can be used as the sole nitrogen source for growth. The aldehydes are further oxidized to the corresponding carboxylic acids by FeaB, a cytosolic NAD-linked aldehyde dehydrogenase (2). Phenylacetate (PA) can be further degraded to acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) and succinyl-CoA, and therefore, PEA can be utilized as the sole carbon and energy source (3–6). In K-12 strains of E. coli, the carboxylic acids derived from tyramine and dopamine cannot be further catabolized, so these compounds can act only as nitrogen sources. Therefore, while TynA activity may allow for both carbon and nitrogen assimilation, FeaB activity is related solely to carbon and energy metabolism (3). Despite the potentially different physiological roles of TynA and FeaB, currently available information suggests that their genes are coordinately regulated by the product of the linked feaR gene, which is a transcriptional regulator from the AraC family (2, 5, 7, 8).

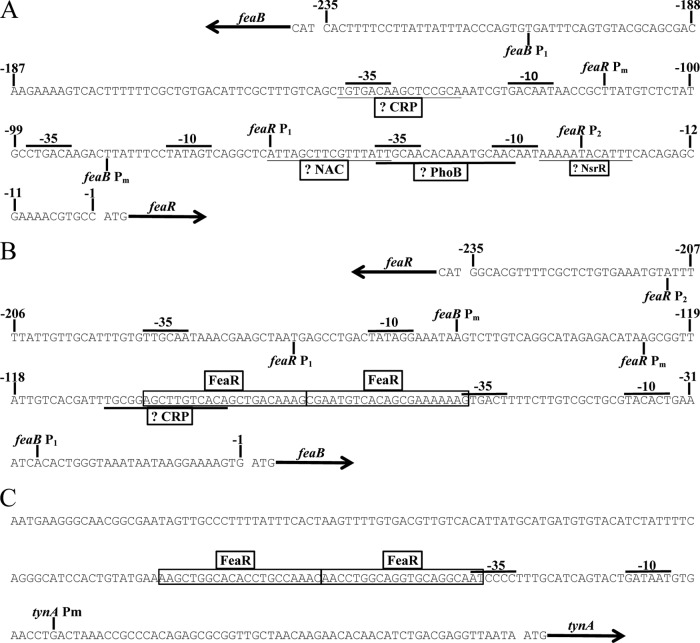

Fig 1.

(A) Pathways for the catabolism of phenylethylamine, tyramine, and dopamine. The first reaction is catalyzed by the periplasmic amine oxidase (TynA) and the second reaction by an NAD-linked dehydrogenase (FeaB). Where substituents at the 3 and 4 positions are hydrogen, the three compounds are phenylethylamine, phenylacetaldehyde, and phenylacetate. With a hydroxyl group at the 4 position, they are tyramine, 4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, and 4-hydroxyphenylacetate. With hydroxyl groups at both the 3 and 4 positions, they are dopamine, 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetate. (B and C) Schematics of the organization of the feaR-feaB intergenic region (B) and the tynA regulatory region (C). Transcription start sites are indicated by bent arrows. Verified and predicted binding sites for regulatory proteins are shown: FeaR (open circles), CRP (filled circle), NAC (open triangle), PhoB (open square), and NsrR (filled square). For additional details and DNA sequences, see Fig. 2.

The AraC family includes over 800 members, most of which are thought to be transcriptional activators that function to regulate genes related to carbon metabolism, stress responses, or pathogenesis (9–11). With some exceptions, AraC family members are characterized by a conserved C-terminal DNA binding domain (CTD) and a nonconserved N-terminal domain (NTD). The nonconserved NTD contains the ligand binding site and, usually, the dimerization interface (9, 10). AraC family regulators that have been well characterized include AraC, MelR, XylS, RhaR, and RhaS (9, 12–18). FeaR is known to be required for the expression of tynA and feaB (7, 8), but its role and mechanism have not otherwise been characterized.

Besides FeaR, there is some evidence that tynA and feaB expression may also be modulated by other transcriptional regulators. We have previously shown that the nitric oxide (NO)-sensitive repressor NsrR binds to sites in the tynA and feaB promoters and has a small effect on the transcription of these genes (8, 19). In addition, there is evidence that feaR expression may be regulated by PhoB (20) and ArcA (P. J. Kiley, personal communication).

In this study, we used computational, genetic, and biochemical approaches to identify the FeaR binding site in the tynA and feaB promoter regions. We showed that the FeaR CTD can bind to DNA in vitro and can activate the tynA promoter in vivo. In full-length FeaR, the NTD appears to act to inhibit the CTD in the absence of the coactivator. We show that the expression of feaR is regulated by carbon or nitrogen limitation and is not subject to autoregulation by the FeaR protein. Overall, we find that tynA expression is activated in both carbon- and nitrogen-limited cells in the presence of a FeaR coactivator, while feaB can be activated only during carbon limitation. We also show that the coactivator for FeaR is probably an aldehyde (the substrate for FeaB) rather than an amine (the substrate for TynA).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth media, and culture conditions.

The strains and plasmids used in this work are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. The methods used to make gene knockouts and to construct chromosomal promoter-lacZ fusions were described previously (8, 21–23). The glnG::kan and nac::kan mutations (in strain BW25113) were obtained from the Keio collection and then were transferred to the reporter strain by P1 transduction (21, 24). DNA sequences encoding the CTD and full-length FeaR were amplified by PCR (primers are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material) and ligated into pBAD24 (25). For β-galactosidase assays, cultures were grown in rich medium (LB) or in defined medium (26) with the indicated carbon and nitrogen sources. For growth with nonpreferred nitrogen sources, ammonium sulfate was replaced with sodium sulfate. For defined medium with PEA as the carbon and nitrogen source (PEA medium), Casamino Acids (0.05% [wt/vol]) were also added. Growth on PEA is temperature sensitive (6) and is significantly improved by the addition of Casamino Acids to growth media. PEA has limited solubility in water, so it was added directly to the bulk medium, which was then sterilized by filtration. Phenylacetaldehyde (PAL) was solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) prior to addition to growth media. Because PAL is toxic (and insoluble in aqueous buffers), it was added in 0.1 mM aliquots at 2-h intervals during the growth of cultures.

Promoter analysis.

The 250-bp, 150-bp, 142-bp, 140-bp, 133-bp, 132-bp, 129-bp, and 126-bp DNA fragments upstream of the tynA start codon (tynA5-1 to tynA5-8), and the 612-bp, 250-bp, 109-bp, 96-bp, 89-bp, 75-bp, and 63-bp DNA fragments upstream of the feaB start codon (feaB5-1 to feaB5-7) were amplified by PCR. The promoter fragments were cloned into pSTBlue-1 as described previously (22). Promoter fusions to lacZ were constructed in pRS415, transferred to λRS45, and integrated into the chromosome as described previously (22, 23). Mutations were introduced into the tynA5-1 clone using the Invitrogen QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit and appropriate mutagenic primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Mutant tynA promoters were fused to lacZ in pRS415 and then transferred to the chromosome (22, 23). 5′ transcription start sites were determined by rapid amplification of 5′ cDNA ends (RACE), using the TaKaRa 5′-full RACE core set according to the manufacturer's directions. The primers used for RACE are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Purification of the FeaR CTD.

The C-terminal domain (CTD) and the linker region of FeaR were identified by sequence alignment of five AraC family proteins (FeaR, AraC, MelR, RhaR, and RhaS) using T-coffee (27). The DNA sequence corresponding to the CTD and linker region was amplified by PCR and ligated into pET-21a(+) (Novagen) in frame with sequences encoding a C-terminal hexahistidine tag. The recombinant plasmid was transformed into E. coli strain BL21(λDE3) for overexpression of the His-tagged CTD. CTDhis was purified using the His GraviTrap kit (GE Healthcare). Protein concentrations were determined using the 660-nm protein assay reagent (Pierce).

DNA binding assay.

5′ biotin-labeled tynA and control (ytfE) promoters were amplified by PCR and gel purified. DNA binding buffer [10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 50 ng/μl poly(dI · dC), 100 ng/μl salmon sperm DNA, 5% glycerol, 0.05% NP-40, 0.5 mM EDTA, 200 μg/ml bovine serum albumin (BSA)] was incubated at the room temperature with or without CTDhis for 1 min (Pierce LightShift chemiluminescent electrophoretic mobility shift assay [EMSA] kit). Biotin-labeled DNA (1 nM) was added to the solution and incubated for 20 min. Protein-DNA complexes were then resolved on 8% polyacrylamide gels. The biotin-labeled DNA was transferred to a Biodyne B membrane (Pall Corporation) and then detected using the chemiluminescent nucleic acid detection module (Pierce).

The DNA binding activity of the FeaR CTD was also assayed by fluorescence anisotropy (28, 29). The rhodamine-X (ROX)-labeled 31-nucleotide (nt) site 1 and site 2 contain 21 nt of the first and second repeats of the FeaR binding site, respectively, flanked by 5 nt upstream and downstream of the full-length FeaR binding site. cDNA strands were annealed by heating at 95°C for 2 min in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer and then cooling to 25°C (at a rate of 1°C per min). ROX-labeled DNA fragments (5 nM) were incubated with 3 ml FA buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 200 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 25 μg/ml BSA, 75 μg/ml salmon sperm DNA) for 10 min, and then CTD (5 nM to 1,300 nM) was added and the reaction mixture incubated for 2 min. The anisotropy change was measured in a Varian Cary Eclipse fluorimeter. The binding isotherm was fit to equation 1 (28) using Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software):

| (1) |

where ΔA is the change in fluorescence anisotropy, ΔAT is the total change in anisotropy, CTD is the total protein concentration at each point in the titration, Kd is the dissociation constant, and nH is the Hill coefficient.

For competition assays, 345 nM CTD was incubated in 3 ml FA buffer for 5 min, and then 5 nM ROX-labeled site 1 or site 2 was added and the reaction mixture incubated for a further 10 min. Unlabeled competitor DNAs (16 to 1,500 nM competitors [see Table 2]) were added, and the anisotropy change was measured after equilibration for 4 min. The data were fit to equation 2 (29):

| (2) |

where FBmax is the fraction bound in the absence of competitor, IC50 is the concentration of competitor required for half-maximal inhibition of binding, and the fraction bound is defined according to equation 3 (29):

| (3) |

where Afree is the anisotropy in the absence of protein.

Table 2.

DNA binding competition assay with mutant FeaR binding sites

| Competitora | DNA sequenceb | IC50 (nM)c |

|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | ATGAAAAGCTGGCACACCTGCCAAACCCCCT | 660 (50) |

| Site 1-A1G | ATGAAgAGCTGGCACACCTGCCAAACCCCCT | 910 (51) |

| Site 1-A1C | ATGAAcAGCTGGCACACCTGCCAAACCCCCT | 1,070 (46) |

| Site 1-A2C | ATGAAAcGCTGGCACACCTGCCAAACCCCCT | 1,330 (65) |

| Site 1-C4G | ATGAAAAGgTGGCACACCTGCCAAACCCCCT | 700 (40) |

| Site 1-T5G | ATGAAAAGCgGGCACACCTGCCAAACCCCCT | No competition |

| Site 1-G6T | ATGAAAAGCTtGCACACCTGCCAAACCCCCT | No competition |

| Site 1-C8A | ATGAAAAGCTGGaACACCTGCCAAACCCCCT | No competition |

| Site 1-A9C | ATGAAAAGCTGGCcCACCTGCCAAACCCCCT | No competition |

| Site 1-A11C | ATGAAAAGCTGGCACcCCTGCCAAACCCCCT | 1,570 (106) |

| Site 1-C13A | ATGAAAAGCTGGCACACaTGCCAAACCCCCT | 691 (47) |

| Site 1-T14G | ATGAAAAGCTGGCACACCgGCCAAACCCCCT | 2,000 (82) |

| Site 1-G15T | ATGAAAAGCTGGCACACCTtCCAAACCCCCT | 1,810 (85) |

| Site 1-C17T | ATGAAAAGCTGGCACACCTGCtAAACCCCCT | 1,120 (60) |

| Site 1-A18T | ATGAAAAGCTGGCACACCTGCCtAACCCCCT | 4,120 (362) |

| Site 1-A19T | ATGAAAAGCTGGCACACCTGCCAtACCCCCT | 1,370 (86) |

| Site 1-A20C | ATGAAAAGCTGGCACACCTGCCAAcCCCCCT | 5,800 (517) |

| Site 2 | ATGAAAACCTGGCAGGTGCAGGCAATCCCCT | 580 (43) |

| Site 2-A23C | ATGAAAcCCTGGCAGGTGCAGGCAATCCCCT | 950 (32) |

| Site 2-C25G | ATGAAAACgTGGCAGGTGCAGGCAATCCCCT | 650 (54) |

| Site 2-T26G | ATGAAAACCgGGCAGGTGCAGGCAATCCCCT | No competition |

| Site 2-G27T | ATGAAAACCTtGCAGGTGCAGGCAATCCCCT | No competition |

| Site 2-C29A | ATGAAAACCTGGaAGGTGCAGGCAATCCCCT | No competition |

| Site 2-A30C | ATGAAAACCTGGCcGGTGCAGGCAATCCCCT | 5,010 (361) |

| Site 2-G32C | ATGAAAACCTGGCAGcTGCAGGCAATCCCCT | 2,650 (156) |

| Site 2-A36C | ATGAAAACCTGGCAGGTGCcGGCAATCCCCT | 1,840 (101) |

| Site 2-A40C | ATGAAAACCTGGCAGGTGCAGGCcATCCCCT | 7,846 (700) |

| Site 2-A41C | ATGAAAACCTGGCAGGTGCAGGCAcTCCCCT | No competition |

Promoter-proximal (site 1) and -distal (site 2) FeaR binding sites from the tynA promoter. Nucleotides are numbered according to the sequence logo (Fig. 3A).

The site 1 and site 2 sequences are underlined, and mutations are in lowercase.

Numbers in parentheses are errors estimated from the data fitting.

RESULTS

Regulation of the feaR promoter.

In order to study the regulation of feaR, feaB, and tynA, the promoters of the three genes were fused to lacZ, and the fusions were transferred to the E. coli MG1655 chromosome (8). β-Galactosidase activities were measured in cultures grown in defined media with different carbon and nitrogen sources (8, 26). In some cases, TynA substrates (PEA or tyramine) were used as the sole source of nitrogen, and/or these were added as inducers to media also containing other nitrogen sources (Table 1). The feaR promoter showed a basal level of activity in defined medium with glucose as the sole carbon source and ammonia as the sole nitrogen source (preferred medium). The promoter activity increased about 2-fold when the carbon source was replaced by glycerol (glycerol medium) and 4- to 6-fold when the nitrogen source was glutamine, alanine, or tyramine (glutamine, alanine, or tyramine medium). Addition of tyramine to the preferred medium or deletion of feaR had no effect on feaR promoter activity (Table 1), indicating that there is no autoregulation of feaR expression. Growth with glucose as the carbon source and tyramine as the nitrogen source was not possible, perhaps reflecting glucose repression of feaR expression (see below).

Table 1.

Activities of the feaR, tynA, and feaB promoters in cultures grown in different media

| Growth conditiona | β-Galactosidase activity (Miller units)b |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| feaR-lacZ | ΔfeaR feaR-lacZ | feaR-lacZ (anaerobic) | tynA-lacZ | ΔfeaR tynA-lacZ | tynA-lacZ (anaerobic) | feaB-lacZ | ΔfeaR feaB-lacZ | feaB-lacZ (anaerobic) | |

| Glucose + (NH4)2SO4 (preferred medium) | 476 (43) | 322 (8) | 160 (11) | 6 (0.9) | 3 (0.3) | ND | 219 (19) | 229 (15) | ND |

| Glycerol + (NH4)2SO4 (glycerol medium) | 951 (85) | 890 (22) | 322 (17) | 5 (0.7) | 3 (0.7) | ND | 225 (18) | 230 (17) | ND |

| Glucose + glutamine (glutamine medium) | 1,857 (123) | 2,123 (130) | 450 (45) | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.6) | ND | 142 (8) | 170 (12) | ND |

| Glucose + alanine (alanine medium) | 2,106 (115) | 2,048 (186) | NG | 5 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) | ND | 115 (5) | 154 (14) | ND |

| Glycerol + tyramine (tyramine medium) | 2,803 (321) | NG | 561 (46) | 1,665 (156) | NG | 5 (0.6) | 545 (16) | NG | ND |

| Preferred medium + tyramine | 389 (35) | ND | ND | 5 (0.1) | ND | 11 (0.6) | 206 (9) | ND | 34 (3) |

| Glycerol medium + tyramine | 953 (70) | ND | ND | 400 (50) | ND | 26 (2) | 464 (41) | ND | 94 (10) |

| Glycerol medium + phenylethylamine | 1,056 (121) | ND | ND | 549 (31) | ND | 3 (0.4) | 577 (25) | ND | 113 (9) |

| Glutamine medium + tyramine | 2,658 (98) | ND | ND | 312 (40) | ND | 7 (0.6) | 174 (13) | ND | 20 (2) |

Carbon and nitrogen source in the defined minimum medium for cell growth.

Values are means of duplicate measurements from each of three independent cultures. Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations. NG, no growth; ND, not done.

The transcription start site of feaR was determined by rapid amplification of 5′ cDNA ends (RACE). According to the RACE results, feaR transcription initiates from three sites, Pm (m for minor), P1, and P2, which are located 111, 66, and 26 bp upstream of the translation initiation codon, respectively (Fig. 1B and 2A). Based on the frequency of different clones recovered from the RACE procedure, all three sites are used in the preferred medium (6% of clones started at Pm, 38% at P1, and 56% at P2), while P1 is the only promoter used in cells grown on defined medium with PEA as the sole carbon source (PEA medium) and is the dominant promoter used in glycerol medium (78% P1 and 22% P2), and P2 is the only promoter used in glutamine medium (Fig. 2A). A sequence that is a good match to the cyclic AMP (cAMP) receptor protein (CRP) binding site is centered at 71.5 bp upstream of the P1 promoter, which is suggestive of a class I type activation mechanism by CRP-cAMP (30–32). Regulation of P1 by CRP-cAMP would be consistent with the preferential utilization of this promoter in glycerol medium. In contrast, the P2 promoter is used preferentially in cells grown on a nonpreferred nitrogen source, which is suggestive of regulation by NtrC or the nitrogen assimilation control protein (NAC) (33–36). Upregulation of feaR in glutamine medium was abolished in ntrC (glnG) and nac mutants (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material), which is consistent with NAC acting as a direct regulator of feaR, since nac expression is NtrC dependent (33–37). Accordingly, there is a predicted NAC binding site associated with the P2 promoter (Fig. 1B and 2A) and no predicted binding sites for NtrC or σ54.

Fig 2.

Transcription start sites of feaR (A), feaB (B), and tynA (C) as determined by 5′ RACE. The binding sites for FeaR as defined in this study are boxed. Suggested binding sites for CRP, NAC, PhoB, and NsrR are underlined. Promoter elements (−35 and −10) associated with the mapped transcription start sites are also indicated.

Regulation of the feaB and tynA promoters.

The feaB promoter showed a relatively low activity unless a substrate for the TynA/FeaB pathway was present in the growth medium (Table 1). Thus, there is not a simple correlation between feaR expression and the activity of its target promoter. The likely explanation is that a pathway substrate or intermediate is required to act as the coactivator for FeaR. Also, activation of the feaB promoter above its basal level required growth on a nonglucose carbon and energy source (for example, compare activities in preferred medium plus tyramine and in glycerol medium plus tyramine [Table 1]). In medium with a nonpreferred nitrogen source (glutamine medium plus tyramine), feaB activity remained low. Two transcription start sites were mapped 149 and 27 bp upstream of the feaB translation initiation codon and named Pm and P1, respectively. The Pm promoter was used in the preferred medium; while only P1 was used in cells growing on PEA medium. This pattern of promoter utilization is consistent with the presence of predicted FeaR and CRP binding sites upstream of the P1 promoter (Fig. 1B and 2B).

Unlike the feaB promoter, the tynA promoter was almost silent under noninducing conditions. Activation of tynA required the presence of either tyramine or PEA in the medium (tyramine medium, PEA medium, or glycerol medium with tyramine or PEA). The requirement for an inducer for tynA promoter activity is consistent with our detection of only a single transcription start site, which is associated with FeaR binding sites (Fig. 1C; Fig. 2C). Unlike feaB activity, tynA activity could be elevated above its basal level by addition of tyramine to the glycerol medium or glutamine medium (Table 1). Thus, in the presence of an inducer, tynA expression is elevated in cells growing on nonpreferred carbon and nitrogen sources.

Activity of the feaR promoter was at basal levels under anaerobic conditions in all growth media tested (Table 1). Accordingly, tynA could not be induced by pathway substrates in anaerobic cultures, and feaB promoter activity was consistently lower than that observed in aerobic cultures. We conclude that expression of the PEA pathway is shut down during anaerobic growth, which can be explained by the recent identification of feaR as a target for ArcA regulation (P. J. Kiley, personal communication).

Overall, our data show that the feaR gene is upregulated during growth on nonpreferred carbon and nitrogen sources. This increase in feaR expression is not sufficient to activate expression of tynA and feaB unless a pathway inducer is also present (although a nonphysiological increase in FeaR abundance may lead to induction of its targets in the absence of inducer [see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material]). Elevated levels of feaB expression require growth on glycerol and either PEA or tyramine, while tynA can be induced by PEA or tyramine in media containing either glucose (with glutamine as the nitrogen source) or glycerol. Thus, tynA can be induced by PEA or tyramine in either carbon- or nitrogen-limited cultures, while feaB is induced only in carbon-limited cultures.

The coactivator for FeaR.

The molecule that functions as the coactivator for FeaR is not known, though previous data and results reported above indicate that it is a substrate or intermediate of the TynA/FeaB pathway (3, 5, 7). We have been unable to test ligand binding to FeaR directly, since purified soluble protein is not available in sufficient yields (see below). We suspected that the coactivator for FeaR might be a FeaB substrate rather than a TynA substrate because (i) the TynA substrate is oxidized in the periplasm and it is the reaction product that is (presumably) transported into the cell and (ii) in multiple genomes, the feaR and feaB genes very frequently cooccur, whereas tynA is also present in only a subset of those genomes. The pattern of gene distribution suggests that FeaR more often functions as an activator of feaB, thus making it likely that the FeaR coactivator is an aldehyde rather than an amine (Fig. 1A). We measured tynA promoter activity in a wild-type strain and a tynA mutant in glycerol medium supplemented with PEA, PAL, or PA (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The activation of tynA in glycerol medium plus PEA is dependent on TynA activity, consistent with the suggestion that the inducer is the product of the TynA reaction. Further, tynA is upregulated by addition of PAL to growth media, and this effect does not require TynA activity (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In addition, PA is not able to activate tynA in either strain (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). These results suggest that the aldehyde is the direct inducer for the PEA catabolic pathway and is the likely coeffector of FeaR.

Computational prediction of the FeaR binding site.

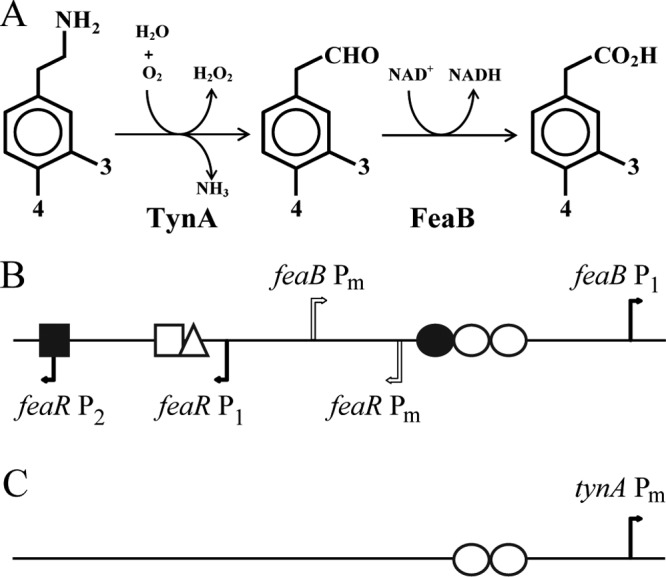

To identify the FeaR binding site, tynA promoter regions and feaR-feaB intergenic regions from different bacteria were collected and used in a search for enriched sequence motifs using the MEME algorithm (38). Sequences were collected only from species that have all three genes, and identical or very similar (<15-bp changes) sequences were discarded. In all, 15 tynA promoters and 10 feaB promoters were used for the motif search. The sequence logo generated by MEME is about 45 bp (Fig. 3A), and a number of patterns that might represent protein binding sites can be discerned in this sequence logo. Experimental results presented elsewhere in this paper suggest that the sequence is best interpreted as a direct repeat of two 16-bp motifs with the core consensus TGKCA-N8-MAA (where K is G or T and M is C or A). The 3′ end of the promoter-proximal FeaR binding site is 32 bp upstream of the tynA P1 and feaB P1 start sites (Fig. 2); in other words, the spacing between these sequence elements and the downstream transcription start sites is precisely conserved.

Fig 3.

(A) The FeaR binding site. Computational prediction of the FeaR binding site is shown. The tynA and feaB promoter regions from different organisms were used in a search for enriched sequence motifs using the MEME algorithm. Arrows indicate nucleotides that constitute the directly repeated TGNCA-N8-AAA, which is the proposed FeaR consensus binding site. (B) Mutations that were introduced into the FeaR binding site. Nucleotides are numbered according to the sequence logo. Those nucleotides that are within the TGNCA-N8-AAA motif are underlined. Mutations above the sequence were introduced for in vitro DNA binding assays. Mutations below the sequence were used for in vivo reporter fusion assays.

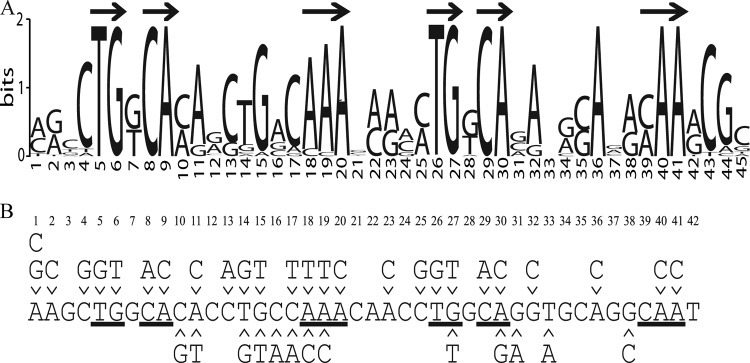

Deletion analysis of the tynA and feaB promoters.

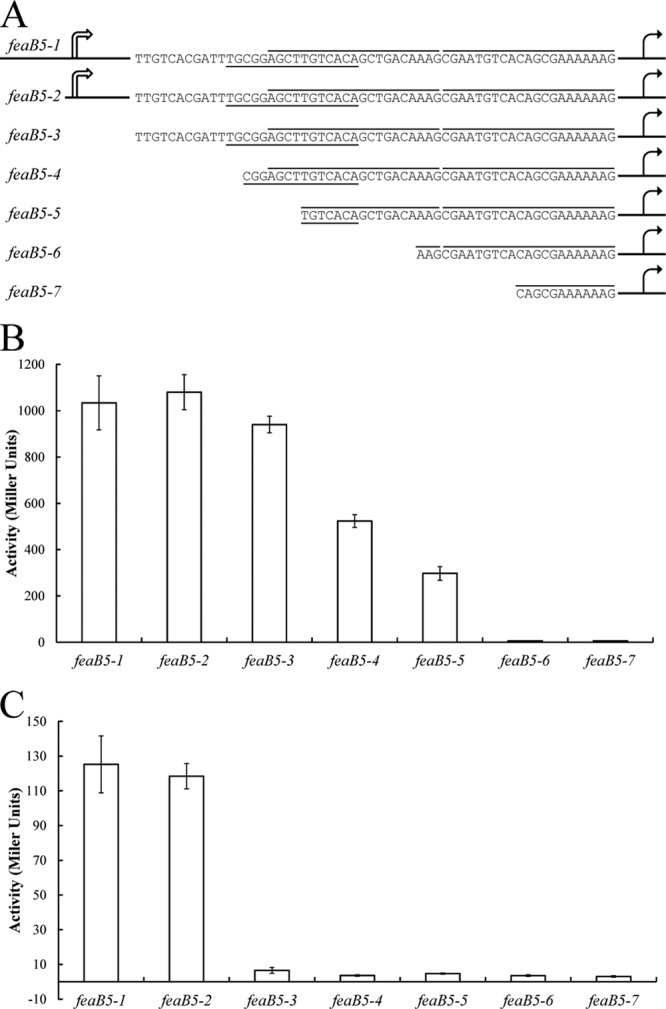

With some information about the locations of transcription start sites and potential FeaR binding sites, we next designed 5′ truncations of the tynA and feaB promoters, which were fused to lacZ. Promoter activities were measured in defined medium with PEA as the sole carbon source (PEA medium) and in glycerol medium. In PEA medium, tynA promoter activity remained high until the first nucleotide of the promoter-distal potential FeaR binding site was deleted. Further deletions completely abolished tynA promoter activity (Fig. 4). In the case of feaB, there was an ∼50% drop in activity for the deletion that extends into the predicted CRP binding site (Fig. 5). This is consistent with the previous observation that the utilization of tyramine as nitrogen source probably requires transcription activation by CRP-cAMP (Table 1). Interestingly, the feaB5-3 deletion, which had full promoter activity in PEA medium, showed no activity in glycerol medium (Fig. 5C). This deletion removes the Pm promoter, which is therefore probably active during growth in glycerol medium. The results of the deletion analysis are consistent with the proposed locations of FeaR and CRP binding sites (Fig. 2).

Fig 4.

Deletion analysis of the tynA promoters. (A) The tynA promoter was truncated as indicated and fused to lacZ for measurements of β-galactosidase activity. The predicted FeaR binding sites are underlined. (B and C) Promoter activity was measured in cultures grown in PEA medium (B) and in glycerol medium (C). Activities are the means of duplicate measurements from each of three independent cultures, and error bars are standard deviations. The 5′ end of tynA5-1 is shown schematically; this fusion contains 250 bp upstream of the tynA translational start site.

Fig 5.

Deletion analysis of the feaB promoters. (A) The feaB promoter was truncated as indicated and fused to lacZ for measurements of β-galactosidase activity. The FeaR binding sites are highlighted by lines above the sequence, and the predicted CRP binding site is underlined. (B and C) Promoter activity was measured in cultures grown in PEA medium (B) and in glycerol medium (C). Activities are the means of duplicate measurements from each of three independent cultures, and error bars are standard deviations. The 5′ ends of feaB5-1 and feaB5-2 are shown schematically; these fusions contain 612 and 250 bp, respectively, upstream of the feaB translational start site.

DNA binding assays.

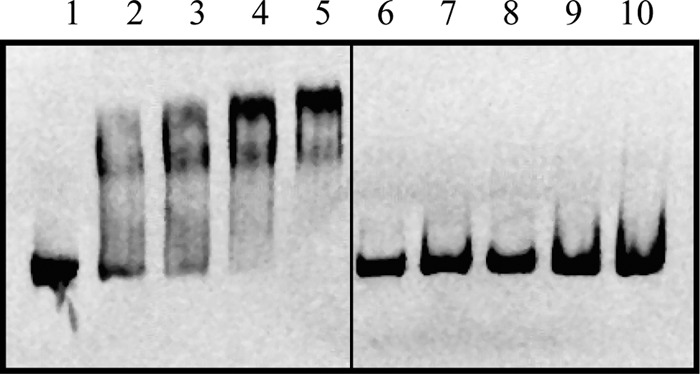

Attempts to purify FeaR using several different approaches yielded material that was highly insoluble, aggregation prone, and/or obtained in very low yields. In this respect, FeaR is similar to other AraC family members (9, 12, 39). For in vitro DNA binding assays, we therefore sought to take advantage of the fact that the isolated CTDs of AraC-type proteins often retain sequence-specific DNA binding activity (15, 16, 40–43). We purified a hexa-His-tagged derivative of the FeaR CTD, having first confirmed that this form of the protein is able to activate the tynA promoter in vivo when expressed at nonnative levels (data not shown). In a gel retardation DNA binding assay, the CTD bound specifically to a 250-bp fragment from the tynA promoter region, showing evidence of two retarded species (Fig. 6). This behavior is consistent with the presence of two FeaR binding sites in the tynA noncoding region.

Fig 6.

Gel retardation assay of FeaR CTD binding to the tynA promoter. A fragment from the ytfE promoter was used as a negative control. The labeled DNAs were tynA (lanes 1 to 5) and ytfE (lanes 6 to 10), and the protein concentrations were 0 (lanes 1 and 6), 250 nM (lanes 2 and 7), 500 nM (lanes 3 and 8), 750 nM (lanes 4 and 9), and 1,000 nM (lanes 5 and 10).

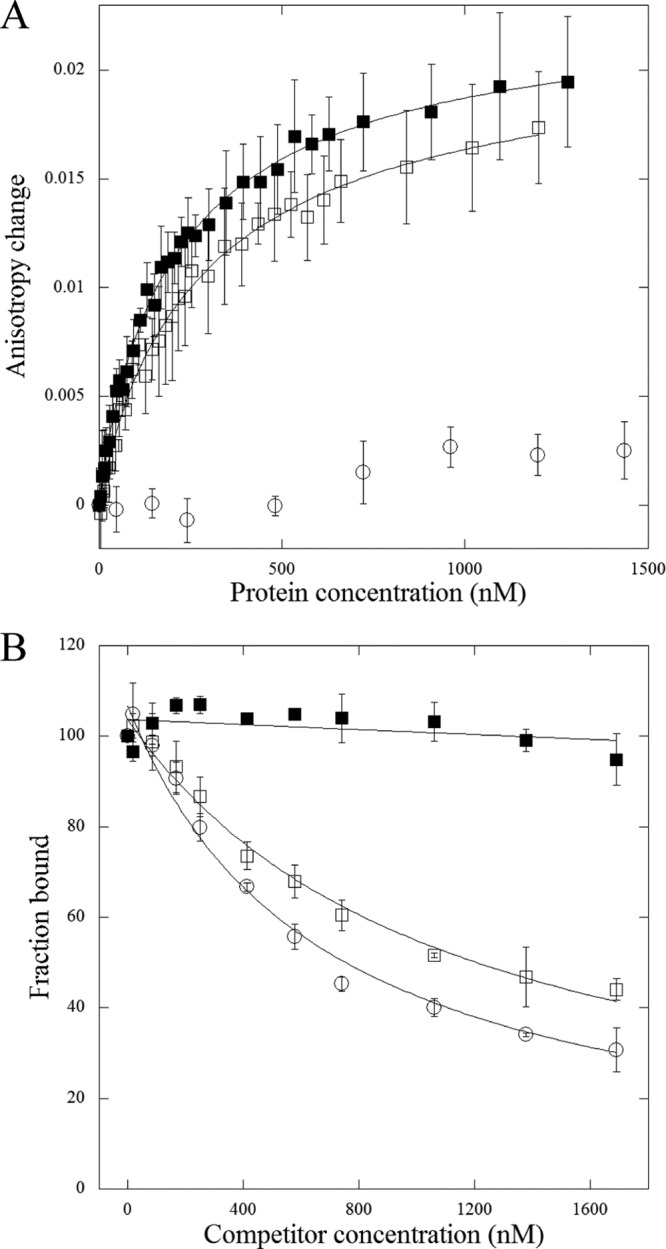

To further analyze the FeaR binding site predicted by MEME, we used fluorescence anisotropy to measure binding of the FeaR CTD to DNA fragments from the tynA promoter region with mutations in the predicted binding sites. Two 31-bp DNA fragments containing the promoter-proximal (site 1) and -distal (site 2) binding sites were used. These DNA fragments were fluorescently labeled and used in measurements of fluorescence anisotropy in the presence of increasing concentrations of the FeaR CTD (28). The CTD bound to site 1 and site 2 with estimated dissociation constants of 301 ± 47 nM and 219 ± 18 nM, respectively. In each case, the Hill coefficient for binding was ∼0.9, consistent with noncooperative binding to a single site (Fig. 7A).

Fig 7.

(A) Assay of DNA binding by the FeaR CTD by fluorescence anisotropy. The purified CTD was titrated into fluorescently labeled DNAs: site 1 (open squares), site 2 (filled squares), and a negative control, the nrdH promoter (open circles). Each data point is the mean of three measurements, and the plot lines show the fit to equation 1 (see Materials and Methods). The estimated dissociation constants are 301 nM ± 47 nM for site 1 and 219 nM ± 18 nM for site 2. (B) Competition assay using DNAs with mutations in the FeaR binding sites. Unlabeled DNAs were titrated into preformed complexes between the FeaR CTD and a labeled DNA. Each data point is the mean of three determinations, and data were fit to equation 2 (see Materials and Methods). Reactions are shown for DNAs that do not (T5G) (filled squares) and do (C17T) (open squares) compete with the wild-type sequence (competition with wild-type DNA is shown with open circles). Data for all mutations are shown in Table 2.

To address the importance of specific residues within the FeaR binding sites, we performed competition binding assays with unlabeled DNAs containing single-site substitutions. In these assays, a 31-bp labeled DNA fragment containing either site 1 or site 2 was approximately half saturated with 345 nM CTD, and unlabeled DNA fragments were titrated into the DNA-protein complex (Fig. 7B; Table 2). For each sequence, we calculated the IC50, i.e., the concentration that is required for half-maximal dissociation of the preexisting complex (29). The IC50s for wild-type site 1 and site 2 were 660 and 580 nM, respectively, and almost all of the mutations increased these values. Four single-site mutations in each site abolished the ability of the sequence to compete for binding (Table 2), implicating these residues as especially important for CTD binding. All eight of these substitutions fall with the TGNCA-N8-AAA element that is present in both fragments, and so the data are consistent with the proposal that this sequence is the FeaR binding site. With one exception (site 1-A19T), all other substitutions within the TGNCA-N8-AAA motifs increased the IC50 by between 6- and 12-fold. In contrast, substitutions outside the proposed FeaR sites increased the IC50 by 4-fold at the most.

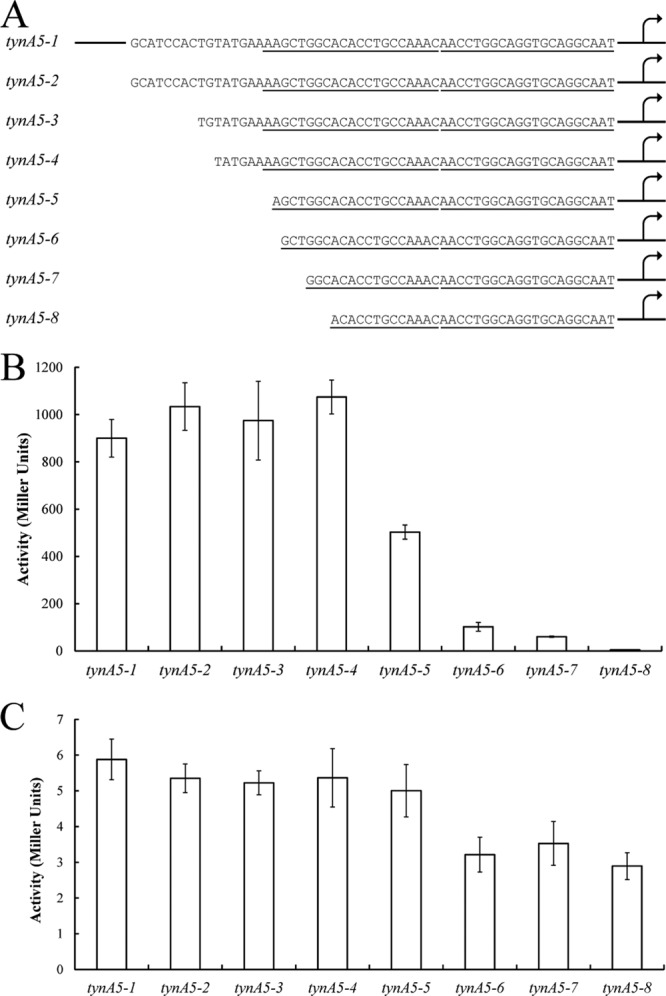

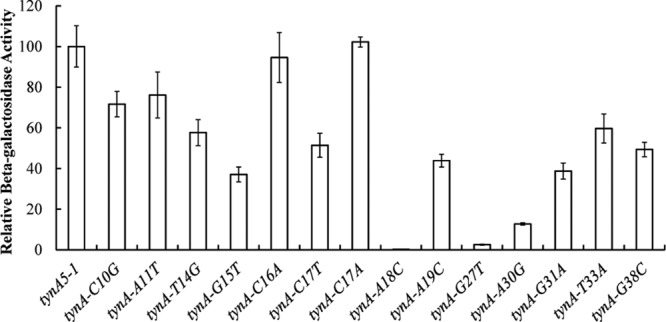

At an earlier stage of this analysis, we had made some point mutations in the region of the FeaR binding sites in the tynA promoter and fused the mutant promoters to lacZ. While this mutagenesis was not comprehensive, it is noticeable that of the four mutations within the TGNCA-N8-AAA motifs, three (A18C, G27T, and A30G) reduced promoter activity by more than a factor of 5 (Fig. 8). Of the remaining 11 mutations that were outside the motifs, two had no effect (C16A and C17A), and eight (C10G, A11T, T14G, G15T, C17T, G31A, T33A, and G38C) reduced the promoter activity to 80 to 40% of the wild-type level. Altogether, our data suggest that the FeaR binding site is a direct repeat of two 16-bp elements. Within each 16-bp sequence, nucleotides within the TGNCA-N8-AAA motif make significant contributions to FeaR binding, while some nucleotides outside the motif also make minor contributions.

Fig 8.

Site-directed mutagenesis of the FeaR binding site in the tynA promoter (Fig. 3). Mutations were introduced at positions in and near the FeaR binding sites, and mutant promoters were fused to lacZ for measurements of β-galactosidase activity. Activities are the means of duplicate measurements in each of three independent cultures, and error bars are standard deviations.

The function of the N-terminal domain.

Sequences encoding FeaR and the CTD were ligated into pBAD24 for expression from the arabinose-inducible araBAD promoter. The plasmids were then transformed into a tynA-lacZ reporter strain to test the activity of FeaR and the CTD. Expression of the CTD led to high-level tynA promoter activity, in both the presence and absence of tyramine (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). The full-length FeaR expressed from pBAD24 activated the tynA promoter significantly above basal levels (to ∼500 units) in the absence of a coactivator and to high levels in the presence of tyramine. Thus, activation by FeaR requires the NTD, as is the case for other AraC family members. Interestingly, the CTD activated tynA better than full-length FeaR in the absence of the coactivator, and this pattern was reversed in the presence of the ligand, suggesting that the NTD might function as an inhibitor of the CTD in the absence of the coactivator.

DISCUSSION

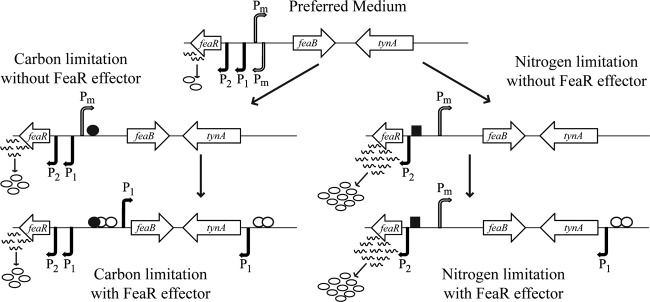

We have developed a model to describe the regulation of tynA and feaB expression that accounts for the data presented in this paper (Fig. 9). During growth on glucose and ammonia (preferred medium), feaR and feaB are expressed at basal levels, while tynA expression is almost silent. During growth on nonpreferred carbon or nitrogen sources (glycerol medium and glutamine medium), feaR expression is elevated 2- to 6-fold, but there is no activation of tynA or feaB in the absence of the FeaR coactivator. During carbon limitation in the presence of the FeaR coactivators (glycerol medium plus tyramine/PEA), both tynA and feaB are upregulated. However, during nitrogen limitation in the presence of the FeaR coactivators (glutamine medium plus tyramine), only tynA is upregulated, while feaB expression remains at a basal level. This regulatory pattern fits with the physiological roles of TynA and FeaB, in the sense that both are required for assimilation of monoamines as a source of carbon and energy, while only TynA is required when pathway substrates are serving only as a nitrogen source (Fig. 1). Thus, while tynA and feaB are coordinately regulated by FeaR, their expression is also fine-tuned by other regulators (CRP and NAC) and by the regulation of feaR expression in order to optimize enzyme activities according to the nutritional environment.

Fig 9.

Summary of the known and proposed mechanisms that regulate transcription of feaR, tynA, and feaB. Active transcription start sites are represented by arrows, with filled arrows for relatively strong promoters and open arrows for weak promoters. The FeaR protein is represented by open circles, CRP-cAMP by filled circles, and NAC by squares. In glycerol-grown cells, feaB is transcribed at low level from Pm, and tynA is not expressed. Upon addition of a FeaR effector, the feaB P1 promoter is activated by FeaR and CRP-cAMP and tynA is activated by FeaR. In cells using glutamine as the nitrogen source, feaB is expressed at a low level from Pm and tynA is not transcribed. In the presence of a FeaR effector, feaB is not expressed, most likely because CRP-cAMP is absent under these conditions. On the other hand, tynA transcription is activated by FeaR. Note that the figure is not drawn to scale.

In addition to CRP and NAC, feaR may also be repressed by PhoB (20) and ArcA (P. J. Kiley, personal communication). The oxidation of PEA, tyramine, or dopamine to the corresponding aldehydes releases one equivalent of H2O2 and NH3 at the expense of one equivalent of O2. There is a physiological rationale for the repression of feaR by PhoB and ArcA: O2 is required for the catabolism of monoamines, and H2O2 is a threat to membrane integrity during phosphate starvation (20). The H2O2 that is released by PEA catabolism is known to cause oxidative stress, activating the OxyR regulon and so stimulating the synthesis of enzymes that remove H2O2 (44). The feaR promoter is under the regulation of multiple global regulators, as is the case for about 50% of all E. coli genes (45). FeaR controls expression of a pathway for the degradation of potentially toxic aromatic compounds. The aldehydes that are the substrates for FeaB are particularly toxic, which may account for the fact that feaB is expressed at a significant level even in the absence of its substrates. A mutation in tynA causes constitutive expression of the SOS response (46), suggesting a role for TynA in removing a genotoxic compound, and we have suggested that TynA and FeaB may have a role in catabolizing toxic nitrated aromatic amines (8). Tyramine and PEA are found in food and in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract as products of the microbial decarboxylation of tyrosine and phenylalanine (47, 48). They may also play signaling roles, for example, influencing swarming motility and the adherence of pathogens to host cells (49–51). Tyramine-induced adherence may involve its binding to adrenergic receptors in intestinal tissue (49). It is also possible that tyramine interferes with signaling via the bacterial adrenergic sensor kinases QseC and QseE (52).

It is common for AraC family members to bind to two direct or inverted repeats upstream of the −35 region of the target promoters (39, 53, 54). Similarly, the FeaR binding site is two direct repeats upstream of the −35 region of tynA and feaB. However, unlike AraC, MelR, and XylS (15, 55, 56), the two FeaR binding sites have similar binding affinities, at least for binding to the FeaR CTD. Despite the fact that feaR and feaB are divergently transcribed with overlapping regulatory regions (Fig. 1), we find no evidence for autoregulation of feaR. The single predicted CRP site in the feaR-feaB intergenic region may be responsible for activation of both genes. This arrangement differs from that of (for example) the melR-melAB and rhaS-rhaBAD regulatory regions, in which the regulatory genes are subject to autoregulation and separate CRP dimers activate the divergently oriented promoters (14, 57).

The FeaR CTD can better activate the tynA promoter than full-length FeaR in the absence of the coactivator; this pattern is reversed in the presence of coactivator. This suggests a dual role of for the NTD: inhibitory in the absence of ligand and stimulatory in the presence of ligand. This inhibitory function of the NTD is not found in MelR and RhaS/RhaR (18, 56, 58) but is found in AraC and XylS (15, 41, 59). The AraC NTD binds to the CTD and holds the CTD in a conformation favoring DNA looping in the absence of arabinose.

In conclusion, we have studied the regulation of the aromatic amine degradation pathway of E. coli and found that the genes encoding the first two enzymes of the pathway are subject to complex regulation involving FeaR and other proteins. The regulatory mechanisms appear to be coordinated to facilitate optimal expression of the two enzymes according to their different physiological roles and to the nutritional environment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Larry Reitzer for helpful discussions and for providing bacterial strains, to Patricia Kiley for communicating results prior to publication, and to Brandon McKethan for help preparing figures.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 6 September 2013

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.00837-13.

REFERENCES

- 1.Klinman JP. 2003. The multi-functional topa-quinone copper amine oxidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1647:131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrandez A, Prieto MA, Garcia JL, Diaz E. 1997. Molecular characterization of PadA, a phenylacetaldehyde dehydrogenase from Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 406:23–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diaz E, Ferrandez A, Prieto MA, Garcia JL. 2001. Biodegradation of aromatic compounds by Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:523–569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teufel R, Mascaraque V, Ismail W, Voss M, Perera J, Eisenreich W, Haehnel W, Fuchs G. 2010. Bacterial phenylalanine and phenylacetate catabolic pathway revealed. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:14390–14395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanlon SP, Hill TK, Flavell MA, Stringfellow JM, Cooper RA. 1997. 2-Phenylethylamine catabolism by Escherichia coli K-12: gene organization and expression. J. Gen. Microbiol. 143:513–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parrott S, Jones S, Cooper RA. 1987. 2-Phenylethylamine catabolism by Escherichia coli K12. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133:347–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamashita M, Azakami H, Yokoro N, Roh JH, Suzuki H, Kumagai H, Murooka Y. 1996. maoB, a gene that encodes a positive regulator of the monoamine oxidase gene (maoA) in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 178:2941–2947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rankin LD, Bodenmiller DM, Partridge JD, Nishino SF, Spain JC, Spiro S. 2008. Escherichia coli NsrR regulates a pathway for the oxidation of 3-nitrotyramine to 4-hydroxy-3-nitrophenylacetate. J. Bacteriol. 190:6170–6177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallegos MT, Schleif R, Bairoch A, Hofmann K, Ramos JL. 1997. Arac/XylS family of transcriptional regulators. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61:393–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egan SM. 2002. Growing repertoire of AraC/XylS activators. J. Bacteriol. 184:5529–5532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin RG, Rosner JL. 2001. The AraC transcriptional activators. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 4:132–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schleif R. 2010. AraC protein, regulation of the l-arabinose operon in Escherichia coli, and the light switch mechanism of AraC action. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34:779–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samarasinghe S, El-Robh MS, Grainger DC, Zhang W, Soultanas P, Busby SJ. 2008. Autoregulation of the Escherichia coli melR promoter: repression involves four molecules of MelR. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:2667–2676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elrobh MS, Webster CL, Samarasinghe S, Durose D, Busby SJW. 2013. Two DNA sites for MelR in the same orientation are sufficient for optimal MelR-dependent repression at the Escherichia coli melR promoter. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 338:62–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dominguez-Cuevas P, Ramos JL, Marques S. 2010. Sequential XylS-CTD binding to the Pm promoter induces DNA bending prior to activation. J. Bacteriol. 192:2682–2690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dominguez-Cuevas P, Marin P, Busby S, Ramos JL, Marques S. 2008. Roles of effectors in XylS-dependent transcription activation: intramolecular domain derepression and DNA binding. J. Bacteriol. 190:3118–3128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wickstrum JR, Skredenske JM, Balasubramaniam V, Jones K, Egan SM. 2010. The AraC/XylS family activator RhaS negatively autoregulates rhaSR expression by preventing cyclic AMP receptor protein activation. J. Bacteriol. 192:225–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolin A, Balasubramaniam V, Skredenske JM, Wickstrum JR, Egan SM. 2008. Differences in the mechanism of the allosteric l-rhamnose responses of the AraC/XylS family transcription activators RhaS and RhaR. Mol. Microbiol. 68:448–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Partridge JD, Bodenmiller DM, Humphrys MS, Spiro S. 2009. NsrR targets in the Escherichia coli genome: new insights into DNA sequence requirements for binding and a role for NsrR in the regulation of motility. Mol. Microbiol. 73:680–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang C, Huang TW, Wen SY, Chang CY, Tsai SF, Wu WF, Chang CH. 2012. Genome-wide PhoB binding and gene expression profiles reveal the hierarchical gene regulatory network of phosphate starvation in Escherichia coli. PLoS One 7:e47314. 10.1371/journal.pone.0047314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bodenmiller DM, Spiro S. 2006. The yjeB (nsrR) gene of Escherichia coli encodes a nitric oxide-sensitive transcriptional regulator. J. Bacteriol. 188:874–881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simons RW, Houman F, Kleckner N. 1987. Improved single and multicopy lac-based cloning vectors for protein and operon fusions. Gene 53:85–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. 2006. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2:2006.0008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guzman LM, Belin D, Carson MJ, Beckwith J. 1995. Tight regulation, modulation, and high-level expression by vectors containing the arabinose PBAD promoter. J. Bacteriol. 177:4121–4130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spencer ME, Guest JR. 1973. Isolation and properties of fumarate reductase mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 114:563–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolin A, Jevtic V, Swint-Kruse L, Egan SM. 2007. Linker regions of the RhaS and RhaR proteins. J. Bacteriol. 189:269–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LiCata VJ, Wowor AJ. 2008. Applications of fluorescence anisotropy to the study of protein-DNA interactions. Methods Cell Biol. 84:243–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nesbit AD, Giel JL, Rose JC, Kiley PJ. 2009. Sequence-specific binding to a subset of IscR-regulated promoters does not require IscR Fe-S cluster ligation. J. Mol. Biol. 387:28–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Busby S, Ebright RH. 1999. Transcription activation by catabolite activator protein (CAP). J. Mol. Biol. 293:199–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Botsford JL, Harman JG. 1992. Cyclic AMP in prokaryotes. Microbiol. Rev. 56:100–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Crombrugghe B, Busby S, Buc H. 1984. Cyclic AMP receptor protein: role in transcription activation. Science 224:831–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reitzer L, Schneider BL. 2001. Metabolic context and possible physiological themes of σ54-dependent genes in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 65:422–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frisch RL, Bender RA. 2010. Expanded role for the nitrogen assimilation control protein in the response of Klebsiella pneumoniae to nitrogen stress. J. Bacteriol. 192:4812–4820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bender RA. 2010. A NAC for regulating metabolism: the nitrogen assimilation control protein (NAC) from Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 192:4801–4811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosario CJ, Frisch RL, Bender RA. 2010. The LysR-type nitrogen assimilation control protein forms complexes with both long and short DNA binding sites in the absence of coeffectors. J. Bacteriol. 192:4827–4833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimmer DP, Soupene E, Lee HL, Wendisch VF, Khodursky AB, Peter BJ, Bender RA, Kustu S. 2000. Nitrogen regulatory protein C-controlled genes of Escherichia coli: scavenging as a defense against nitrogen limitation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97:14674–14679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bailey TL, Williams N, Misleh C, Li WW. 2006. MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 34:W369–W373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Egan SM, Schleif RF. 1994. DNA-dependent renaturation of an insoluble DNA binding protein. Identification of the RhaS binding site at rhaBAD. J. Mol. Biol. 243:821–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Timmes A, Rodgers M, Schleif R. 2004. Biochemical and physiological properties of the DNA binding domain of AraC protein. J. Mol. Biol. 340:731–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kaldalu N, Toots U, de Lorenzo V, Ustav M. 2000. Functional domains of the TOL plasmid transcription factor XylS. J. Bacteriol. 182:1118–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caswell R, Williams J, Lyddiatt A, Busby S. 1992. Overexpression, purification and characterization of the Escherichia coli MelR transcription activator protein. Biochem. J. 287:493–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wickstrum JR, Skredenske JM, Kolin A, Jin DJ, Fang J, Egan SM. 2007. Transcription activation by the DNA-binding domain of the AraC family protein RhaS in the absence of its effector-binding domain. J. Bacteriol. 189:4984–4993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ravindra Kumar S, Imlay JA. 2013. How Escherichia coli tolerates profuse hydrogen peroxide formation by a catabolic pathway. J. Bacteriol 195:4569–4579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ishihama A. 2010. Prokaryotic genome regulation: multifactor promoters, multitarget regulators and hierarchic networks. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34:628–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Reilly EK, Kreuzer KN. 2004. Isolation of SOS constitutive mutants of Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 186:7149–7160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marcobal A, De las Rivas B, Landete JM, Tabera L, Munoz R. 2012. Tyramine and phenylethylamine biosynthesis by food bacteria. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 52:448–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Halasz A, Barath A, Simonsarkadi L, Holzapfel W. 1994. Biogenic-amines and their production by microorganisms in food. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 5:42–49 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lyte M. 2004. The biogenic amine tyramine modulates the adherence of Escherichia coli O157:H7 to intestinal mucosa. J. Food Prot. 67:878–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morgenstein RM, Szostek B, Rather PN. 2010. Regulation of gene expression during swarmer cell differentiation in Proteus mirabilis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34:753–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stevenson LG, Rather PN. 2006. A novel gene involved in regulating the flagellar gene cascade in Proteus mirabilis. J. Bacteriol. 188:7830–7839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hughes DT, Clarke MB, Yamamoto K, Rasko DA, Sperandio V. 2009. The QseC adrenergic signaling cascade in enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC). PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000553. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Webster C, Gardner L, Busby S. 1989. The Escherichia coli melR gene encodes a DNA-binding protein with affinity for specific sequences located in the melibiose-operon regulatory region. Gene 83:207–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carra JH, Schleif RF. 1993. Variation of half-site organization and DNA looping by AraC protein. EMBO J. 12:35–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seabold RR, Schleif RF. 1998. Apo-AraC actively seeks to loop. J. Mol. Biol. 278:529–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Howard VJ, Belyaeva TA, Busby SJ, Hyde EI. 2002. DNA binding of the transcription activator protein MelR from Escherichia coli and its C-terminal domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:2692–2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holcroft CC, Egan SM. 2000. Interdependence of activation at rhaSR by cyclic AMP receptor protein, the RNA polymerase alpha subunit C-terminal domain, and RhaR. J. Bacteriol. 182:6774–6782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Michan CM, Busby SJ, Hyde EI. 1995. The Escherichia coli MelR transcription activator: production of a stable fragment containing the DNA-binding domain. Nucleic Acids Res. 23:1518–1523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saviola B, Seabold R, Schleif RF. 1998. Arm-domain interactions in AraC. J. Mol. Biol. 278:539–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.