Abstract

Legionella pneumophila, a facultative intracellular bacterium, is the causative agent of legionellosis. In the environment this pathogenic bacterium colonizes the biofilms as well as amoebae, which provide a rich environment for the replication of Legionella. When seeded on pre-formed biofilms, L. pneumophila was able to establish and survive and was only found at the surface of the biofilms. Different phenotypes were observed when the L. pneumophila, used to implement pre-formed biofilms or to form mono-species biofilms, were cultivated in a laboratory culture broth or had grown intracellulary within the amoeba. Indeed, the bacteria, which developed within the amoeba, formed clusters when deposited on a solid surface. Moreover, our results demonstrate that multiplication inside the amoeba increased the capacity of L. pneumophila to produce polysaccharides and therefore enhanced its capacity to establish biofilms. Finally, it was shown that the clusters formed by L. pneumophila were probably related to the secretion of a chemotaxis molecular agent.

Introduction

Legionella is a facultative intracellular gram-negative bacteria found in natural freshwater environments as well as in man-made water systems [1]. Legionella pneumophila is the major agent of legionellosis, except in Australia, where Legionella longbeachae is the major causative agent [2], [3]. The infection is due to multiplication within alveolar macrophages after inhalation by human of contaminated aerosols produced by many engineered water systems such as air conditioning, cooling towers, hot water systems, whirlpools and spas, vegetable misters, shower heads and dental unit water lines [4]–[8].

The control of L. pneumophila in water networks is principally based on decontamination processes. However, it is now well known that this bacterium resists to biocide treatments because of its sessile way of life into biofilms as well as its capacity of growth within amoeba [9]–[11].

Legionella spp. require supplementation in amino acids and therefore, have developed mechanisms to acquire these nutrients by residing in nutrient rich biofilms [12]–[15]. L. pneumophila is able to survive and grow on dead biofilm-associated microbial cells such as heat-killed bacteria, amoebae and yeast [16]. In Legionella monospecies biofilm development in rich nutrient medium, temperature has a role about thickness and structure [17]. Biofilms constitute the major source of human contamination. Microbial formation of biofilm communities provides protection against physical or chemical agents. Thus, it was demonstrated by numerous studies [13], [14], [18] that L. pneumophila, prepared from laboratory culture medium, is able to implement into a pre-formed biofilm for bacteria.

Amoeba such as Acanthamoeba castellanii and ciliate protozoan are able to graze biofilm material [19]. In these environments, Legionella is a target of protozoan predation and has developed the capacity to parasitize and reside in 20 species of amoebae, three species of ciliated protozoa and one species of slime mould [20]–[22]. Numerous studies show the necessity of the presence of protozoans for the survival and replication of L. pneumophila in aquatic environments [14], [23]. The study of Declerck et al, in 2007 [24], shows that Acanthamoeba castellanii is not only used for intracellular replication but as a transporter like a “Trojan horse” [12] and Neumeister et al [25] proved that intracellular replication in human monocytic leukocytes is enhanced after infection of Acanthamoeba castellanii. Free protozoa not only select virulence traits, but also facilitate the transmission of Legionella spp to humans within intact amoebae or expelled vesicles [26]. The ability of Legionella spp to persist and colonize biofilm as well as parasitization of amoeba cells can be considered as a survival mechanism, but this can lead to severe consequences for human health.

With the current study, we provide information about the implementation of Legionella on static biofilms composed of non-Legionella bacteria similar to those present in aquatic systems. We compared the behavior of Legionella after culture in a usual medium, after infection of amoebae, or passage through ciliated protozoan in condition near to anthropogenic water networks.

Experimental Procedures

Strains and culture conditions

The Legionella strains used are L. pneumophila Lens (CIP 108286), a clinical isolate, Paris (LG03), an environmental isolate and Legionella longbeachae (ATCC 33484). The plasmid PSW001 or plasmid pMMB207-KM14-GFPc [26] encoding the protein DsRed and GFPMut2 were used to transform the bacteria. Legionella was grown in BYE medium (Buffered Yeast Extract) or BCYE (Buffered Charcoal Yeast Extract) at 37°C with chloramphenicol at 10 µg/mL when necessary. The experiments were made with L. pneumophila expressing GFP or Ds-red with similar results.

The pre-formed biofilms consisted of selected strains usually found in anthropogenic water networks [22]. Non-Legionella bacteria were Aeromonas hydrophila (Library of Microbiology Universiteit Gent, Belgium (LMG 2844)), Escherichia coli (LMG 2092), Flavobacterium breve (LMG 4011) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (LMG 1242). These strains were grown in BHI (Brain Heart Infusion) at 37°C.

Acanthamoeba castellani 30254 [27] was grown in medium PYG (Proteose Yeast Glucose) [28] at 25°C and Tetrahymena tropicalis was cultivated in PCB (Plate count Broth) at room temperature in the dark.

Preparation for the implementation of Legionella in the biofilm

The preparation described downhere were realized with the three Legionella strains cited previously.

“Medium Grown” (MG) Legionella non-filamentous condition

Legionella grown in culture media produced numerous filamentous cells, often more than 40 µm long, which is not the case after their passage into amoebae or ciliates (data not shown). Legionella non-filamentous stationary phase form were grown according to the protocol of the CNRL Lyon [10]. Bacteria were then suspended in sterile mineral water (Evian). As it is well known that nutrient depletion induces the stationary phase in Legionella [29], [30], under these conditions, these bacteria reached stationary form and were named "Medium Grown” bacteria. The fluorescence of strains was checked by epifluorescence microscopy.

"Amoeba Grown" (AG) Legionella

Amoeba, after 2 days of culture, were harvested and washed in amoeba buffer. Acanthamoeba were placed in contact with Legionella following a multiplicity of infection or MOI (Mutiplicity Of Infection) of 0.1 and incubated at 30 ° C. After 96 hours, Legionella were collected by centrifugation at 10000 g for 10 minutes. The pellet was washed twice with filtered mineral water and was resuspended by vortex. After centrifugation, the preparation was allowed 10 min to precipitate and only the upper half of the volume was taken. The absence of amoeba and the fluorescence of Legionella were checked using an epifluorescence microscope. Under these conditions, these bacteria were designated “Amoeba Growing" (AG).

“Medium Growing” Legionella treated with AG supernatant (MG+ Sur AG)

After 24 hours of incubation at 37°C, AG Legionella suspension was centrifuged 5 minutes at 10000 g and the cell free supernatant was collected. Supernatant (1 mL) was added to a pellet of 1.108 MG cells. After incubation during 1 hour at 37°C, Legionella suspension was centrifuged at 4500 g for 15 minutes and washed two times with mineral water. The fluorescence of Legionella was checked using an epifluorescence microscope. Under these conditions, these bacteria were designated “treated MG Legionella" (tMG).

“Ciliated Grown” (CG) Legionella

After 7 days of culture of Tetrahymena tropicalis the medium was gradually replaced between centrifugation by Osterhout's Tris buffer [10]. Legionella were added with MOI of 1000 bacteria for 1 protozoan. After 96 hours, the suspension was centrifuged and the medium discarded. Distilled water was added and left one night in the dark. The next day, water was eliminated. Legionella pellets were broken using syringes 27 and 22 gauges. Broken pellets and Legionella fluorescence were controlled by epifluorescence microscopy. Under these conditions, these bacteria and were designated “Ciliate Grown" (CG).

Alcian blue test

The wells of 6 well plates were filled with 2 ml of sterile mineral water. Each well was inoculated with 2.109 Legionella and incubated 24 hours at 37°C without agitation. The supernatant was removed and replaced by 1 mL of Alcian blue 8G (Sigma-Aldrich) at 0.1% in distilled water. After 30 min incubation, each well was washed three times and 1 mL of 33% acid acetic was added. Absorbance was measured at 595 nm.

Crystal violet test

The first part of the test was performed like Alcian blue assay. The supernatant of the wells was removed and replaced by 1 mL of 0.3% Crystal Violet (Sigma-Aldrich) in distilled water. After 15 min incubation, each well was washed three times with mineral water and 1 mL of absolute ethanol was added. Absorbance was then measured at 595 nm.

Legionella transformation

Legionella were grown on BCYE for 72 h and suspended by scrapping from the plates with 50 mL of sterile double distilled water. The cell suspension was centrifuged in a cold rotor (4°C) at 5500 g for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was washed three other times with half a volume of water each time. The final volume was added to make a concentration of 2.1011 cells/mL. The bacteria suspension was dispensed into 50 µL and transferred to a cold electroporation cuvette. After addition of 200 µg of plasmid DNA, electroporation was performed using a Gene Pulser apparatus. One mL of BYE was added after the pulse and incubated at 37°C without agitation. After one hour, 100 µL of suspension were spread on BCYE plates containing chloramphenicol. Transformants were confirmed by the presence of plasmid DNA by electrophoresis on 0.4% agarose gels.

Microscopy

Development of biofilms

Biofilms were made in 12 well plates with glass bottom adapted for confocal microscopy. In each well, 2 mL of BHI diluted 1/100 with mineral water (to reach organic matter concentration equivalent to river water) were introduced. The wells were inoculated with 5.106 bacteria of each of the four non-Legionella strains from an overnight pre-culture. The plates were incubated for 15 days at 37°C with media changes every four days. The medium was then removed and replaced by 2 mL of filtered mineral water. Biofilms were then seeded with 1.107 Legionella cells of different types (MG, AG and CG) and the plates were incubated for 7 days at 37°C. The microscopic observations were realized every 24 hours.

Staining

The wells were washed with mineral water to eliminate non-adherent Legionella. To mark the exopolysaccharide matrix, Concanavalin A AlexaFluor 350 conjugate (Invitrogen) was added according to the manufacturer's recommendations and wells were incubated 20 minutes at 37°C and then washed with mineral water. Draq 5 (Biostatus) was added to stain all bacteria as recommended by the supplier.

Observation and processing

The observations were made with the epifluorescence microscope Axio Observer A1 (Zeiss) equipped with Apotome. This module allows structured illumination. The microscope is equipped with a mercury lamp and filters specific for DAPI (Zeiss Filter Set 49), FITC (Zeiss Filter Set 44), Cy3 (Zeiss Filter Set 43) and Cy5 (Zeiss Filter Set 50), and the Plan Neofluar 1.25 oil immersion objective (Zeiss). The images were taken using the AxioVision software and processed with the software Imasis7.4.1 and Zen (Zeiss).

PCR

DNA extractions were performed with the High Pure PCR Template Kit (Roche) according to the supplier's recommendations. Primers used were listed in Table 1. PCR conditions were as follows: an initial denaturation step of 94°C for 5 min and then 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec., primer annealing 60°C for 30 sec., and polymerase extension at 72°C for 60 sec.

Table 1. Sequence and name of primers used for tested presence or absence of lqs gene.

| Name | Sequence |

| lqsA forward | AATCCTGGCAAGGGAAACAC |

| lqsA reverse | AACACGGCTCCAAAGATGTC |

| lqsR forward | CGTATTGCAGCTGGATGAGG |

| lqsR reverse | GGCAGGAACCAAACAATTCG |

| lqsS forward | CTGGTTGCCTCAGCCTTATG |

| lqsS reverse | AGCGTATTCGCCCTCTTTAG |

| lqsT forward | GATGCAAGCCACCAAATCAC |

| lqsT reverse | GCAAGCGGCGTTCTTAAATC |

Quantitative PCR

DNA extractions were performed with the High Pure PCR Template Kit (Roche) according to the supplier's recommendations. The qPCR were performed with primers specific for the mip gene (mipA1, mipA2 described by Jonas et al [31], with the Light Cycler FastStart DNA kit SybrGreen Master and Light Cycler 32 wells according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Results

Implementation of Legionella on multi-species biofilms

It was shown earlier [32] that Legionella pneumophila is able to colonize pre-formed biofilms consisting of the four aquatic bacteria Aeromonas hydrophila, Escherichia coli, Flavobacterium breve and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, generally present in the same aquatic environment as L. pneumophila [12], [14], [18], [32]–[34]. Thus we prepared biofilms composed of these bacteria, on glass support fixed under 12 wells microplates and using a BHI medium diluted 100 times with Evian mineral water. Indeed, it was recently shown [35] that the mineral composition of this water is particularly adapted for the biofilm formation by L. pneumophila. Every 4 days, medium was renewed. In all conditions tested, Legionella were described as highly mobile [36], [37].

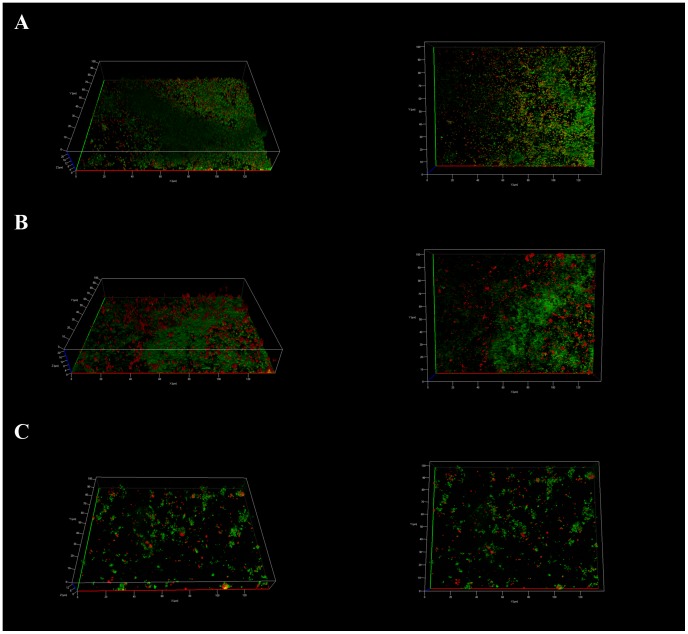

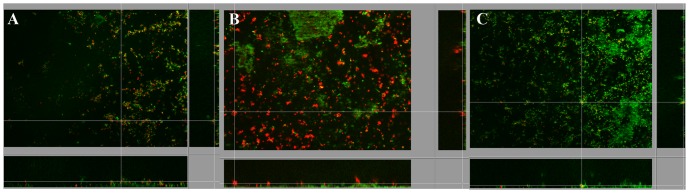

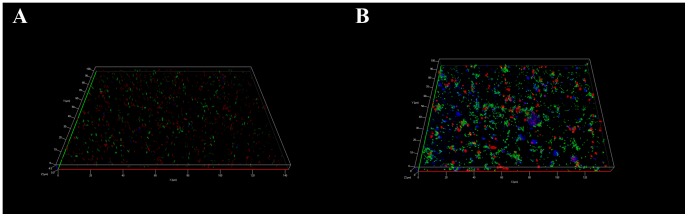

After 15 days, Ds-red fluorescent L. pneumophila Lens cells, prepared from BYE culture medium, named “Medium Grown” (MG) or after growing within Acathamoeba castelanii, “Amoeba Grown” (AG) or within ciliated protozoan, Tetrahymena tropicalis, "Ciliated Grown" (CG) were added to the pre-formed biofilms and medium was replaced by steril mineral water (Evian). Within one week, MG L. pneumophila established in the pre-formed biofilms as single cells, which were globally disseminated overall the surface of the non-Legionella strains biofilm (figure 1A). Transversal imaging (Figure 2) demonstrated that none of the L. pneumophila cells were found inside the biofilm structure but were all situated at the surface of the biofilm. The same results were obtained with CG L. pneumophila, (Figure 1C). Likewise, AG L. pneumophila were found only on the surface of the biofilm (Figure 1B) and were never found deeper inside the structure. However, contrarily to the MG bacteria the AG L. pneumophila appeared aggregated instead of individual cells. The same results were obtained with L. pneumophila Paris and L. longbeachae (not shown).

Figure 1. Apotome imaging, 7 days after establishment of L. pneumophila Lens A) MG, B) AG and C) CG, in biofilm pre-formed with four non-Legionella strains during 15 days from water networks.

L. pneumophila expressing Ds-Red marker appears in red and non-Legionella bacteria, marked using Draq5 stain, in green. Pictures are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Figure 2. Orthogonal views of apotome imaging, 7 days after establishment of L. pneumophila Lens A) MG and B) AG, in biofilm pre-formed with four non-Legionella strains during 15 days from water networks.

L. pneumophila expressing Ds-Red marker appears in red and non-Legionella bacteria, marked using Draq5 stain, in green.

When inoculated to monospecies biofilms pre-formed with each of the four non-Legionella strains, the MG and AG L. pneumophila had the same behavior as observed with multispecies biofilms, namely single cells for MG Legionella and clusters for AG Legionella (Figure 3). These results indicate that none of the four strains constituting the pre-formed biofilm could be specifically implicated in the establishment differences observed for the types of L. pneumophila.

Figure 3. Apotome imaging, 7 days after establishment of L. pneumophila Lens MG, in biofilm pre-formed with each of the four non-Legionella strains during 15 days from water networks.

Establishment in A) Pseudomonas aeuginosa, B) Flavobacterium breve, C) Aeromonas hydrophila and D) Escherichia coli. L. pneumophila expressing Ds-Red marker appears in red and non-Legionella bacteria, marked using Draq5 stain, in green.

Monospecies biofilm formation by L. pneumophila

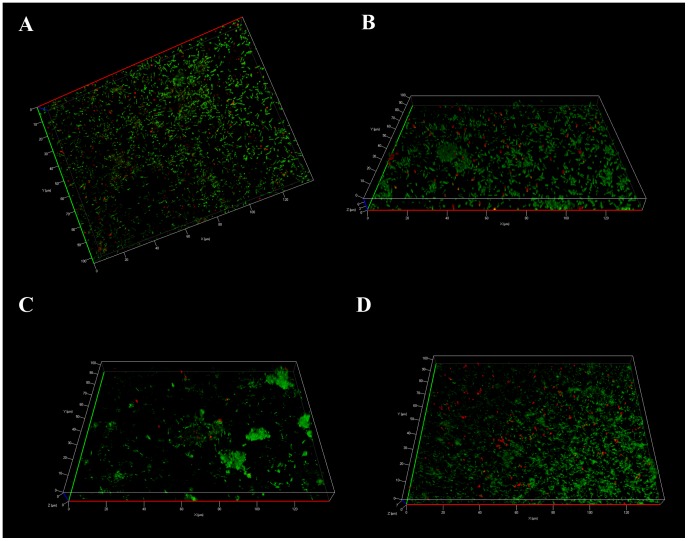

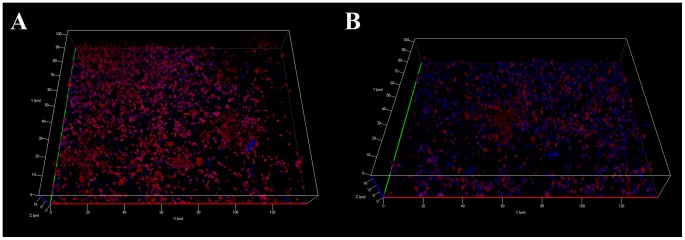

In order to determine whether the observed phenotypes for L. pneumophila in biofilm depended on the existence of a pre-formed biofilm, both types of L. pneumophila, MG and AG, were directly inoculated on the glass surfaces fixed at the bottom of the wells of a microplate. The MG L. pneumophila cells (figure 4A) appeared dispersed on the glass surface and this biofilm was found very thin, about 8 µm, with large areas devoid of attached cells. On the contrary, the biofilm obtained from the AG L. pneumophila (figure 4B) appeared thicker and presented densely packed bacteria separated by open structures.

Figure 4. Apotome imaging after 7 days of biofilm development on a glass surface of L. pneumophila Lens A) MG C) AG and polysaccharides produced by B) MG and D) AG L. pneumophila Lens.

Legionella are in green and polysaccharides in blue. Pictures are representative of 6 independent experiments.

Moreover, while the polysaccharides were poorly detected in the MG L. pneumophila biofilm (figure 4A) this type of macromolecule appeared abundant in the AG L. pneumophila biofilm (in blue on figure 4B and 4C) and was preferentially detected around the clusters of bacteria.

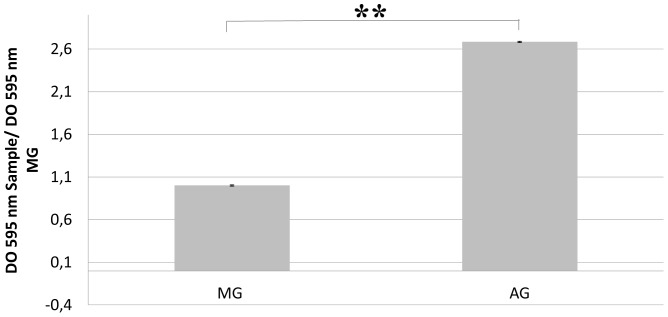

In order to verify whether the observed polysaccharides were newly synthesized by L. pneumophila and did not originate from A. castelanii, the amount of polysaccharide was determined using Alcian Blue. The amount of polysaccharide was too low to be detected in the MG as well the AG L. pneumophila suspensions used to seed the microplate wells (2.109 cells), indicating that it was synthesized by bacteria during biofilm formation. Moreover, it was found that the amount of polysaccharide newly synthesized after one day was 2.78 times higher for the AG L. pneumophila than the MG L. pneumophila (Figure 5), which confirmed the microscopy analyses.

Figure 5. Alcian blue test results after 249 MG and AG L. pneumophila Lens in Evian mineral water.

Error bars indicate standard deviation from six independent experiments. The p-value is less than 0,0001, this difference is considered to be extremely statistically significant.

L. pneumophila clusters origin

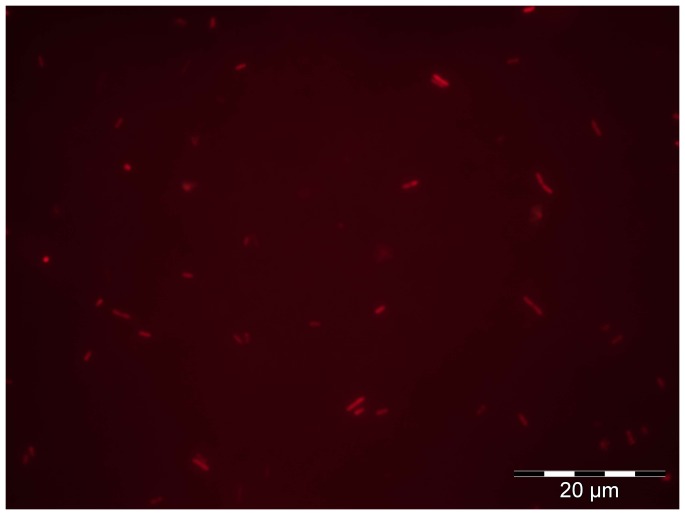

We hypothesized that the bacterial clusters observed for AG L. pneumophila could be formed in the amoeba cell before the release of the bacteria in the medium or by aggregation only after the release of L. pneumophila in the very early step of the biofilm formation. The AG L. pneumophila suspension appeared only as isolated cells (figure 6). No bacterial clusters were observed in this experiment whatever the L. pneumophila strain, Lens (figure 4), Paris (not shown) or L. longbeachae (not shown). This indicates that the aggregation occurred after the release from amoeba.

Figure 6. Epifluorescence microscopy observation of L. pneumophila Lens expressing ds-Red marker (in red) immediately after amoebae release.

Picture is representative of 2 independent experiments.

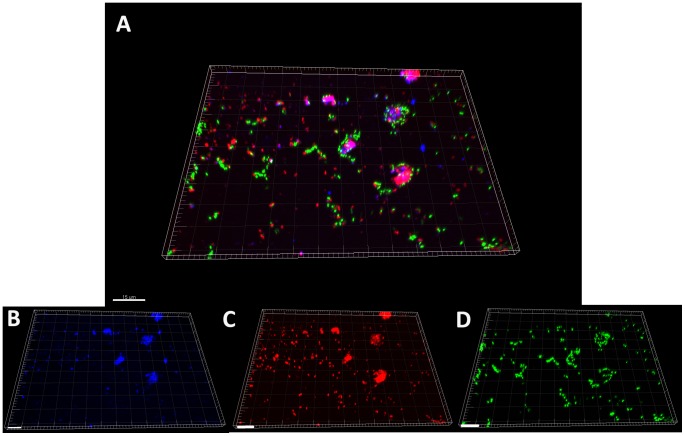

In order to verify whether the clusters originated from an aggregation of bacteria or the multiplication from a single cell, GFP and Ds-Red expressing AG L. pneumophila were mixed before spreading on the glass surface. The resulting clusters (Figure 7) were constituted of both types of cells, green and red, indicating that they came from an aggregation instead of cell division. Moreover, we observed a high quantity of yellow spots, corresponding to a co-localization of green and red cells. The same experiment, conducted with MG L. pneumophila, showed only isolated green and red cells homogenously distributed overall the glass surface (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Apotome imaging after 7 days of biofilm development on a glass surface of a mixture of A) AG L. pneumophila Lens or B) MG L. pneumophila Lens expressing Ds-Red marker (in red) or GFP marker (in green) and polysaccharides (in blue).

Pictures are representative of 3 independent experiments.

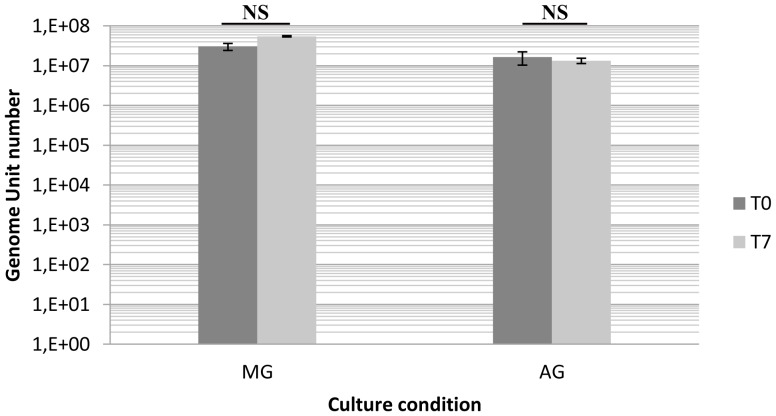

Moreover, the non-multiplication of L. pneumophila was confirmed using a qPCR analysis since the number of MG a well as AG bacteria was similar, after one week biofilm development than in the initial suspension (figure 8). Declerck et al (2005) show that L. pneumophila increase in amoeba buffer, alone or with the same four non-Legionella strains, was only due to intracellular multiplication of the human pathogen [32].

Figure 8. Results of qPCR amplification mip gene from MG and AG L. pneumophila Lens deposited on glass surface in Evian mineral water at T = 0 and T = 7 days.

Error bars indicate standard deviation from three independent experiments. The p-value is equal to 0,5913 for AG L. pneumophila Lens and 0,2709 for MG L. pneumophila Lens. It is considered not to be statistically significant (NS).

Taken together, these results suggest that the L. pneumophila, which multiplied within the amoeba, expressed, after their release in the environment, a molecular factor, which induced a mutual attraction of the bacteria.

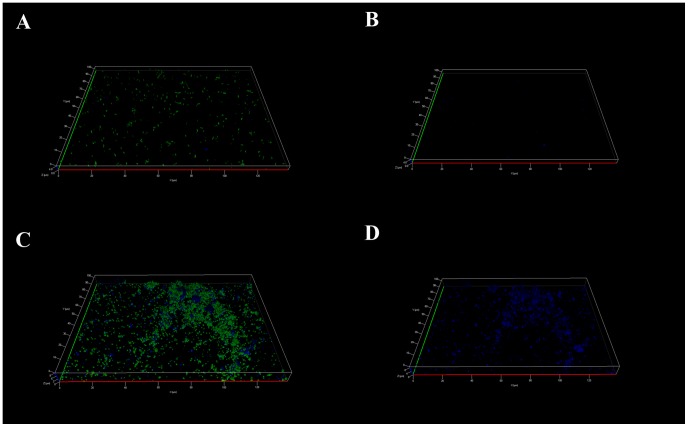

Chemotaxis factor

In order to verify our chemotaxis hypothesis, GFP expressing MG L. pneumophila were added to Ds-Red expressing AG L. pneumophila before inoculating the glass surface. The observed clusters of bacteria (figure 9) were composed of AG L. pneumophila, in red, covered with MG L. pneumophila, in green. This result shows that the “chemotaxis” factor expressed by AG bacteria was able to attract the MG L. pneumophila. Interestingly it has to be noticed that these “hybrid” clusters were partially embedded in newly synthesized polysaccharides (in blue, figure 9).

Figure 9. Apotome imaging after 7 days of biofilm development on a glass surface of a mixture of L. pneumophila lens AG expressing ds-Red marker (in red), and MG GFP marker (in green).

Polysaccharides appear in blue. Pictures are representative of 3 independent experiments. Scale bar corresponds to 10 µm.

To confirm the factor production, MG Legionella pneumophila Lens were treated with the supernatant of AG Legionella then inoculated into plates. After 7 days of incubation, Legionella aggregates were visible (Figure 10) with the presence of a large amount of exo-polyssacccharides. These Legionella acquired the same ability to develop a biofilm as AG Legionella, which suggests the latter secreted a compound that can induce an AG phenotype. Moreover, this result confirms that the observed exopolysaccharides were produced by Legionella pneumophila and not by amoeba.

Figure 10. Apotome imaging after 7 days of biofilm development on a glass surface of a A) L. pneumophila Lens treated with supernatant of AG L. pneumophila Lens or B) with supernatant of AG L. longbeachae.

Bacteria are in red and polysaccharides appear in blue. Pictures are representative of 3 independent experiments.

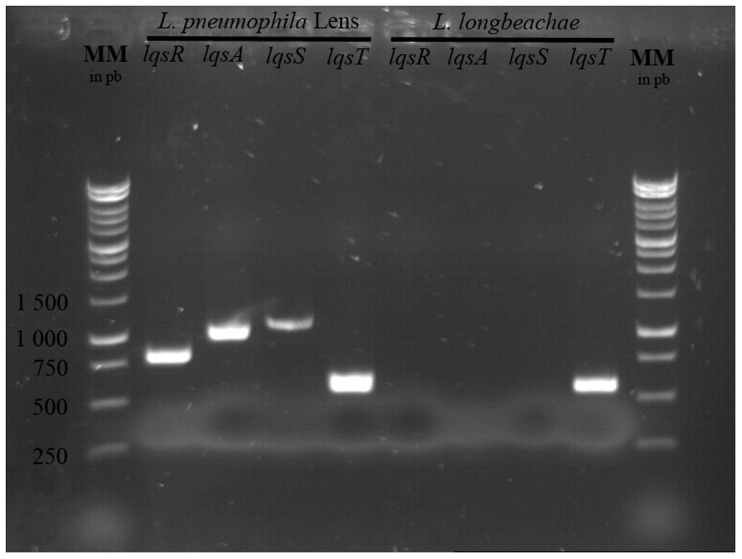

These results suggest the implication of a system similar to quorum sensing. A Legionella quorum sensing system named lqs was described by Spirig et al [38]. It was shown that this system was absent from Legionella longbeachae [33], [39]–[42]. Firstly, a PCR analysis was performed to verify the presence of the different lqs genes in Legionella pneumophila Lens, used as a positive control and Legionella longbeachae (ATCC 33484) (Figure 11). The results of the amplification confirmed the absence of the lqsA, R and S from Legionella longbeachae. To determine whether the induction system detected here corresponds to lqs system, we performed an experiment in which MG L. pneumophila Lens were treated with the supernatant of AG L. longbeachae, then suspended in mineral water and deposited on glass plate. After 7 days of incubation, Legionella aggregates, similar to those obtained with Legionella AG, and presence of exo-polysaccharides were observed (Figure 10 B). Thus, despite the lack of lqs system in L. longbeachae including lqsA, coding the enzyme responsible for the synthesis of LAI-1 autoinducer, a biofilm phenotype was induced. These preliminary results suggest the existence of a different quorum sensing system in Legionella intra and inter-species.

Figure 11. Picture of lqs PCR analysis electrophoresis gel of L. pneumophila Lens and L. longbeachae.

Pictures are representative of 3 independent experiments.

Discussion

It was demonstrated by numerous studies [13], [14], [18] that L. pneumophila, prepared from laboratory culture medium, is able to implement into a pre-formed biofilm for bacteria. In the first part of our study we showed that this implementation also occurred for Legionella cells released from ciliated protozoan or amoeba. And we also showed that the Legionella remained stable after seven days. This could indicate that the Legionella did not multiply in the biofilm, as it was previously proposed by Mampel and colleagues [33] who related the L. pneumophila development in biofilm to the adhesion of planktonic bacteria rather than by clonal replication of sessile cells. This is consistent with the study of the Legionella monospecies biofilms of Pecastaings and collaborators [43], who demonstrated that sessile L. pneumophila is able to grow in a minimum medium only when it is supplemented with iron and cysteine but not in an oligotrophic medium.

Whatever the origin of the bacteria, in our experiments, the Legionella cells appeared located on the surface of the pre-formed biofilm, which could be quite normal but also paradoxical, considering that the biofilm matrix protects the bacteria from external stresses. This superficial location could be related to our experimental conditions because observations were made only a week after seeding Legionella. It could be possible that the Legionella kinetic of penetration, or burying, into the biofilm matrix requires longer duration. However it could also be postulated that this superficial location on biofilm is advantageous regarding Legionella's ability to grow on dead bacteria. Indeed, probably because of its requirement for L-cysteine, Legionella is capable of necrotrophic feeding, thus utilizing dead bacteria, protozoans or other microflora for sustenance [16]. In these cases, Legionella pneumophila is located on boundary layer of biofilm, an advantage for this fastidious organisms that permit to Legionella to have access at more nutrient [44]. Stress, like nutrient depletion as in our experiment, was described to promote acceptance and recruitment of new members in the biofilm [45], [46]. In another way, it could be proposed that the Legionella located at the surface of the biofilm in order to be more accessible for amoeba grazing then subsequent intra-amoeba multiplication.

The other major observation we made in this study is the presence of aggregates, conjugated with the production of exopolysaccharides by the “Amoeba Grown” (AG) Legionella cells but not the “Medium Grown” (MG). Moreover, this behavior is not related to the origin of the strain because the results obtained with a clinical strain, L. pneumophila Lens, and strain originally isolated in the environment, L. pneumophila Paris, as well as L. longbeachae were the same.

At first we hypothesized that these bacterial aggregates corresponded to micro-colonies obtained consecutively to clonal multiplication of L. pneumophila after the initial adhesion on the glass surface or the pre-formed biofilm. We demonstrated that aggregation depends on the mutual attraction of the bacteria but only after they grew within amoeba. Moreover, this is clearly in relation with a multiplication phase, since after passage in Tetrahymena tropicalis, where no replication was observed, a phenotype similar to the MG Legionella, not AG, was obtained. It can be hypothesized that this gathering is related to the production of a chemotaxis molecular agent specifically by the Legionella cells which grew in amoeba and after their release in the environment.

The target of this attraction could be bacterial cells themselves which could express both the chemotaxis factor and its putative specific sensor, the latter being induced by the factor acting as an inducer. In this case, we could postulate that the expression of the sensor was already induced for AG bacteria, which can rapidly gather whereas the MG Legionella expressed the sensor with delay when induced by the chemotaxis factor. This could then explain why the MG bacteria appeared to coat the surface of the AG clusters whereas we could imagine that the attraction of the MG bacteria to AG cells led to the formation of bi-colored aggregates, because both types of cells where mixed before deposition on glass surface. Moreover, the chemotataxis factor seems to be dependent of the intracellular replication as shown by its lack from CG L. pneumophila.

A L. pneumophila quorum sensing system involving an autoinducer, LqsA,and a sensor, LqsS, was previously described [40]. However, the authors have demonstrated that the genes encoding such system are not present in the L. longbeachae genome [38]. Nevertheless, the ability to form biofilm acquired by Legionella after its intracellular growth was observed in our experiments with MG L. pneumophila Lens treated with supernatant of AG Legionella longbeachae which did not possess lqs genes. Thus, the chemotaxis factor is different than LAI-1. Nevertheless, with this study, we have demonstrated the existence of new quorum sensing system intra and inter-species.

Finally, it has to be noticed that the AG L. pneumophila expressed, when adhered, large amounts of polysaccharides. Moreover, because AG cells but not MG cells produced very important amounts of such polysaccharides, this is again related to a passage within amoeba. In our opinion this phenomenon is developed by Legionella issued from the protozoan in order to rapidly protect themselves from external conditions. Indeed, when we first tried to quantify the L. pneumophila using classical crystal violet staining (not shown), these assays always gave negative results whereas qPCR as well as microscopy demonstrated the presence of a biofilm. We thus hypothesized that the polysaccharides in which the Legionella were embedded could trap the crystal violet which was not able to stain the bacterial cells. Structure of the exo-polysaccharide has to be characterized. However, because it was recognized by concanavalin A [47], [48] and Alcian Blue [49], [50] it could be hypothesized that it is partly constituted of glucose and/or mannose residues.

To confirm the major importance of the Legionella exo-polysaccharide in the biofilm development it could be proposed to characterize it and after to search genes encoding potential glycosyl transferases which are involved in the production of such polymers by screening the genome of L. pneumophila. Moreover, it is important to isolate and characterize the causative agent of chemotaxis to study its role in the different stages of biofilm development and its hypothetical roles in intracellular replication stages or in virulence capacity.

To conclude, we have developed a biofilm model near to the water distribution system using Amoeba Grown Legionella which have higher ability to colonize or to develop biofilm in particular via exopolysaccharide secretion. We propose to encourage the use of this model to test or develop disinfection process rather than conventional models using Legionella derived from culture medium.

Funding Statement

The ministère de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche is acknowledged for R. Bigot Ph.D. funding. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Steinert M, Hentschel U, Hacker J (2002) Legionella pneumophila: an aquatic microbe goes astray. FEMS Microbiol Rev 26: 149–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Asare R, Abu Kwaik Y (2007) Early trafficking and intracellular replication of Legionella longbeachaea within an ER-derived late endosome-like phagosome. Cell Microbiol 9: 1571–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cazalet C, Gomez-Valero L, Rusniok C, Lomma M, Dervins-Ravault D, et al. (2010) Analysis of the Legionella longbeachae genome and transcriptome uncovers unique strategies to cause Legionnaires' disease. PLoS Genet 6: e1000851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Atlas RM (1999) Legionella: from environmental habitats to disease pathology, detection and control. Environ Microbiol 1: 283–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bhopal RS (1991) Surveillance of disease and information on laboratory request forms: the example of Legionnaires' disease. J Infect 22: 97–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bollin GE, Plouffe JF, Para MF, Hackman B (1985) Aerosols containing Legionella pneumophila generated by shower heads and hot-water faucets. Appl Environ Microbiol 50: 1128–1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bollin GE, Plouffe JF, Para MF, Prior RB (1985) Difference in virulence of environmental isolates of Legionella pneumophila. J Clin Microbiol 21: 674–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ewann F, Hoffman PS (2006) Cysteine metabolism in Legionella pneumophila: characterization of an L-cystine-utilizing mutant. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 3993–4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kim BR, Anderson JE, Mueller SA, Gaines WA, Kendall AM (2002) Literature review--efficacy of various disinfectants against Legionella in water systems. Water Res 36: 4433–4444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koubar M, Rodier MH, Garduno RA, Frere J (2011) Passage through Tetrahymena tropicalis enhances the resistance to stress and the infectivity of Legionella pneumophila. FEMS Microbiol Lett 325: 10–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thomas V, Bouchez T, Nicolas V, Robert S, Loret JF, et al. (2004) Amoebae in domestic water systems: resistance to disinfection treatments and implication in Legionella persistence. J Appl Microbiol 97: 950–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Declerck P, Behets J, van Hoef V, Ollevier F (2007) Detection of Legionella spp. and some of their amoeba hosts in floating biofilms from anthropogenic and natural aquatic environments. Water Res 41: 3159–3167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Declerck P, Behets J, van Hoef V, Ollevier F (2007) Replication of Legionella pneumophila in floating biofilms. Curr Microbiol 55: 435–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Murga R, Forster TS, Brown E, Pruckler JM, Fields BS, et al. (2001) Role of biofilms in the survival of Legionella pneumophila in a model potable-water system. Microbiology 147: 3121–3126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rogers J, Keevil CW (1992) Immunogold and fluorescein immunolabelling of Legionella pneumophila within an aquatic biofilm visualized by using episcopic differential interference contrast microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol 58: 2326–2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Temmerman R, Vervaeren H, Noseda B, Boon N, Verstraete W (2006) Necrotrophic growth of Legionella pneumophila. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 4323–4328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Piao Z, Sze CC, Barysheva O, Iida K, Yoshida S (2006) Temperature-regulated formation of mycelial mat-like biofilms by Legionella pneumophila. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 1613–1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vervaeren H, Temmerman R, Devos L, Boon N, Verstraete W (2006) Introduction of a boost of Legionella pneumophila into a stagnant-water model by heat treatment. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 58: 583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Huws SA, McBain AJ, Gilbert P (2005) Protozoan grazing and its impact upon population dynamics in biofilm communities. J Appl Microbiol 98: 238–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hagele S, Kohler R, Merkert H, Schleicher M, Hacker J, et al. (2000) Dictyostelium discoideum: a new host model system for intracellular pathogens of the genus Legionella. Cell Microbiol 2: 165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kikuhara H, Ogawa M, Miyamoto H, Nikaido Y, Yoshida S (1994) Intracellular multiplication of Legionella pneumophila in Tetrahymena thermophila. J UOEH 16: 263–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rowbotham TJ (1980) Preliminary report on the pathogenicity of Legionella pneumophila for freshwater and soil amoebae. J Clin Pathol 33: 1179–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kuiper MW, Wullings BA, Akkermans AD, Beumer RR, van der Kooij D (2004) Intracellular proliferation of Legionella pneumophila in Hartmannella vermiformis in aquatic biofilms grown on plasticized polyvinyl chloride. Appl Environ Microbiol 70: 6826–6833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Declerck P, Behets J, De Keersmaecker B, Ollevier F (2007) Receptor-mediated uptake of Legionella pneumophila by Acanthamoeba castellanii and Naegleria lovaniensis. J Appl Microbiol 103: 2697–2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Neumeister B, Reiff G, Faigle M, Dietz K, Northoff H, et al. (2000) Influence of Acanthamoeba castellanii on intracellular growth of different Legionella species in human monocytes. Appl Environ Microbiol 66: 914–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hilbi H, Hoffmann C, Harrison CF (2011) Legionella spp. outdoors: colonization, communication and persistence. Environ Microbiol Rep 3: 286–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dupuy M, Mazoua S, Berne F, Bodet C, Garrec N, et al. (2011) Efficiency of water disinfectants against Legionella pneumophila and Acanthamoeba. Water Res 45: 1087–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bellamy W, Takase M, Wakabayashi H, Kawase K, Tomita M (1992) Antibacterial spectrum of lactoferricin B, a potent bactericidal peptide derived from the N-terminal region of bovine lactoferrin. J Appl Bacteriol 73: 472–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Faulkner G, Berk SG, Garduno E, Ortiz-Jimenez MA, Garduno RA (2008) Passage through Tetrahymena tropicalis triggers a rapid morphological differentiation in Legionella pneumophila. J Bacteriol 190: 7728–7738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Molofsky AB, Swanson MS (2004) Differentiate to thrive: lessons from the Legionella pneumophila life cycle. Mol Microbiol 53: 29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jonas D, Rosenbaum A, Weyrich S, Bhakdi S (1995) Enzyme-linked immunoassay for detection of PCR-amplified DNA of legionellae in bronchoalveolar fluid. J Clin Microbiol 33: 1247–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Declerck P, Behets J, Delaedt Y, Margineanu A, Lammertyn E, et al. (2005) Impact of non-Legionella bacteria on the uptake and intracellular replication of Legionella pneumophila in Acanthamoeba castellanii and Naegleria lovaniensis. Microb Ecol 50: 536–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mampel J, Spirig T, Weber SS, Haagensen JA, Molin S, et al. (2006) Planktonic replication is essential for biofilm formation by Legionella pneumophila in a complex medium under static and dynamic flow conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol 72: 2885–2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stojek NM, Dutkiewicz J (2011) Co-existence of Legionella and other Gram-negative bacteria in potable water from various rural and urban sources. Ann Agric Environ Med 18: 330–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Koubar M, Rodier MH, Frere J (2013) Involvement of minerals in adherence of Legionella pneumophila to surfaces. Curr Microbiol 66: 437–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Byrne B, Swanson MS (1998) Expression of Legionella pneumophila virulence traits in response to growth conditions. Infect Immun 66: 3029–3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pruckler JM, Benson RF, Moyenuddin M, Martin WT, Fields BS (1995) Association of flagellum expression and intracellular growth of Legionella pneumophila. Infect Immun 63: 4928–4932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Spirig T, Tiaden A, Kiefer P, Buchrieser C, Vorholt JA, et al. (2008) The Legionella autoinducer synthase LqsA produces an alpha-hydroxyketone signaling molecule. J Biol Chem 283: 18113–18123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kessler A, Schell U, Sahr T, Tiaden A, Harrison C, et al. (2013) The Legionella pneumophila orphan sensor kinase LqsT regulates competence and pathogen-host interactions as a component of the LAI-1 circuit. Environ Microbiol 15: 646–662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tiaden A, Spirig T, Carranza P, Bruggemann H, Riedel K, et al. (2008) Synergistic contribution of the Legionella pneumophila lqs genes to pathogen-host interactions. J Bacteriol 190: 7532–7547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tiaden A, Spirig T, Sahr T, Walti MA, Boucke K, et al. (2010) The autoinducer synthase LqsA and putative sensor kinase LqsS regulate phagocyte interactions, extracellular filaments and a genomic island of Legionella pneumophila. Environ Microbiol 12: 1243–1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tiaden A, Spirig T, Weber SS, Bruggemann H, Bosshard R, et al. (2007) The Legionella pneumophila response regulator LqsR promotes host cell interactions as an element of the virulence regulatory network controlled by RpoS and LetA. Cell Microbiol 9: 2903–2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pecastaings S, Berge M, Dubourg KM, Roques C (2010) Sessile Legionella pneumophila is able to grow on surfaces and generate structured monospecies biofilms. Biofouling 26: 809–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Nadell CD, Bucci V, Drescher K, Levin SA, Bassler BL, et al. (2013) Cutting through the complexity of cell collectives. Proc Biol Sci 280: 20122770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Besemer K, Singer G, Limberger R, Chlup AK, Hochedlinger G, et al. (2007) Biophysical controls on community succession in stream biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 4966–4974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cheng KJ, Costerton JW (1986) Microbial adhesion and colonization within the digestive tract. Soc Appl Bacteriol Symp Ser 13: 239–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ibey BL, Beier HT, Rounds RM, Cote GL, Yadavalli VK, et al. (2005) Competitive binding assay for glucose based on glycodendrimer-fluorophore conjugates. Anal Chem 77: 7039–7046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Neu TR, Kuhlicke U, Lawrence JR (2002) Assessment of fluorochromes for two-photon laser scanning microscopy of biofilms. Appl Environ Microbiol 68: 901–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mead TJ, Yutzey KE (2009) Notch pathway regulation of chondrocyte differentiation and proliferation during appendicular and axial skeleton development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106: 14420–14425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Scott JE (1996) Alcian blue. Now you see it, now you don't. Eur J Oral Sci 104: 2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]