Abstract

Background.

Chemotherapy prolongs life and relieves symptoms in men with castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). There is limited information on a population level on the use of chemotherapy for CRPC.

Material and methods.

To assess the use of chemotherapy in men with CRPC we conducted a register-based nationwide population-based study in Prostate Cancer data Base Sweden (PCBaSe) and a nationwide in-patient drug register (SALT database) between May 2009 and December 2010. We assumed that men who died of prostate cancer (PCa) underwent a period of CRPC before they died.

Results.

Among the 2677 men who died from PCa during the study inclusion period, 556 (21%) had received chemotherapy (intravenous or per oral) detectable within the observation period in SALT database. Specifically, 239 (61%) of men < 70 years had received chemotherapy, 246 (30%) of men between 70 and 79 years and 71 (5%) men older than 80 years. The majority of men 465/556 (84%) had received a docetaxel-containing regimen. Among chemotherapy treated men, 283/556 (51%) received their last dose of chemotherapy during the last six months prior to death. Treatment with chemotherapy was more common among men with little comorbidity and high educational level, as well as in men who had received curatively intended primary treatment.

Conclusion.

A majority of men younger than 70 years with CRPC were treated with chemotherapy in contrast to men between 70 and 79 years of whom half as many received chemotherapy. Chemotherapy treatment was often administered shortly prior to death. The low uptake of chemotherapy in older men with CRPC may be caused by concerns about tolerability of treatment, as well as treatment decisions based on chronological age rather than global health status.

In 2004, docetaxel was shown to increase survival, relieve symptoms, and increase quality of life in men with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) and docetaxel is currently gold standard for first line chemotherapy for CRPC [1–3]. A survival benefit of nine months was observed in men with CRPC treated with weekly docetaxel and prednisone compared to men treated with only prednisone [4]. The beneficial effects of docetaxel has been documented both in symptomatic and asymptomatic CRPC and it is independent of age and performance status at initiation of therapy [3,5]. According to several guidelines, docetaxel should be initiated in symptomatic disease [3,6], but treatment of asymptomatic men with CRPC and a short prostate-specific antigen (PSA) doubling time or high PSA serum levels should be considered since early chemotherapy results in increased survival compared to delayed treatment [3,6].

Little is known about the use of chemotherapy in men with CRPC on a population level. A few single institutions and one population-based study have reported low treatment intensity, ranging from 12% to 37% [7–10]. In order to assess the use of chemotherapy in men with CRPC we conducted a register-based, nationwide population-based study in Prostate Cancer data Base Sweden (PCBaSe) combined with a nationwide drug register.

Material and methods

The National Prostate Cancer Register (NPCR) of Sweden

The National Prostate Cancer Register (NPCR) captures 98% of all incident PCa cases in Sweden since 1998 and contains detailed information on tumor characteristics and primary treatment [11]. Tumor risk category was based on a modification of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Practice Guidelines in Oncology [12] and classified into five risk groups, defined as: 1) low-risk with (clinical stage T1-2, Gleason score 2-6, and PSA < 10 ng/ml); 2) intermediate-risk (T1-2, Gleason score 7 and/or PSA 10–20); 3) high-risk (T3 and/or Gleason score 8–10 and/or PSA 20–50); 4) Regionally metastatic (T4 and/or N1 and/or PSA 50–100 without distant metastasis); and 5) distant metastasis (M1 and/or PSA > 100) [12].

Prostate Cancer data Base Sweden (PCBaSe)

By using the individually unique Swedish personal identity number, NPCR has been linked to a number of other population-based healthcare registers and demographic databases forming the Prostate Cancer data Base Sweden (PCBaSe). The database has recently been described in detail [11]. Information on underlying and contributing cause of death according to ICD-10 and date of death was obtained from the Cause of Death Register capturing all deaths in Sweden. The validity of the Cause of Death Register has been demonstrated to be high for prostate cancer (PCa). There was an overall 96% agreement on PCa as the cause of death when death certificates obtained from the Cause of Death Register were compared with the cause of death assigned by an independent blinded committee review in the Göteborg screening trial [13], and in another study with a wider range in stage and grade, the agreement on cause of death between the Register and chart review was 86% [14]. Information on medical conditions other than cancer was obtained from the National Patient Register, where the main diagnosis and up to seven secondary discharge diagnoses from in-hospital stays beside the PCa diagnosis were retrieved. The capture rate for somatic in-patient care is virtually 100%. Malignancies other than PCa were identified in the Swedish Cancer Register. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was used to assess the burden of concomitant disease for each man [15]. The CCI consists of 18 groups of diseases with a specific weight assigned to each disease category (1, 2, 3 and 6). The weights were then summed to obtain an overall score, resulting in the four comorbidity levels of CCI (0, 1, 2, 3+) [16]. When assessing the individual CCI for men with PCa in this study, PCa with a weight of 2 and metastatic cancer with a weight of 6 were excluded from the assessment. Demographic data was obtained from the Register of the Total Population [11]. Information on educational level was retrieved from Longitudinal integration database for health insurance and labor market studies database [LISA (acronym in Swedish)], a database containing data on all Swedish residents aged 16 and over on educational level, disposable income, socioeconomic index, welfare benefits and employment status which is updated annually. Men were categorized according to the highest attained level of education, into ‘low’ (1–9 years mandatory school), ‘middle’ (10–12 years high school), and ‘high’ (university studies or equivalent).

Drug registers

The Swedish Prescribed Drug Register.

Information on prescribed peroral drugs was retrieved from The Swedish Prescribed Drug Register containing data on all prescriptions dispensed in Swedish pharmacies in an out-patient setting. The register does not include data on over-the-counter medications or drugs used in-hospital or in nursing homes. The register is updated monthly and the capture rate is virtually complete, with data on patients’ identities missing for less than 0.3% [11].

In-hospital medication database.

During the observation period (21 May 2008 – 31 December 2010), the Sjukhusapotekens läkemedelstillverkning (SALT)/Hospital pharmaceutical manufacturing database contained individual information on type of chemotherapy, dose and date of production on all chemotherapy prepared in 27 of 30 Swedish hospital pharmacies. Three hospitals in the southern region could not be included in our analyses since their chemotherapy prescriptions were not registered in this database. Information on chemotherapy prepared locally in out-patient clinics was not registered in the SALT database and hence not included in the study. After three years the personal identity number is erased from the SALT database and thereafter data on an individual level cannot be analyzed.

Study population, design and statistical methods

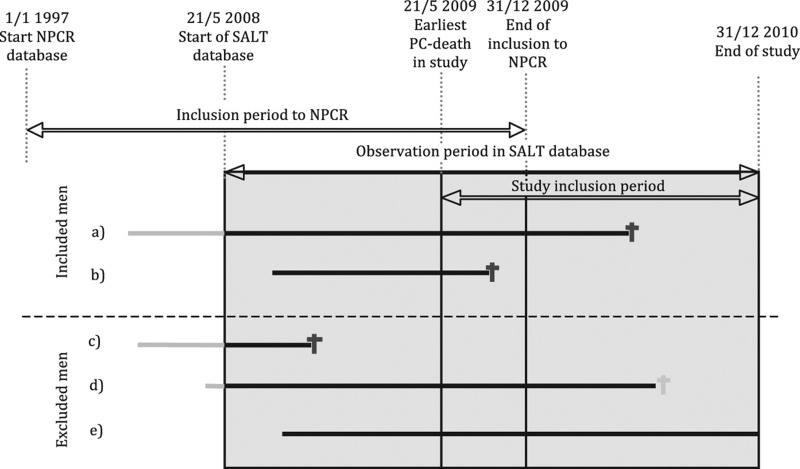

NPCR only collects data from the initial six month time period after date of diagnosis. Thus, men with CRPC cannot be identified in this register and therefore we used an indirect method to capture men with CRPC. Based on that > 90% of men in NPCR who died of PCa had received androgen deprivation therapy we assumed that men who died of PCa underwent a period of CRPC before death. Included cases were men diagnosed with PCa, registered in the NPCR prior or during the observation period in SALT database (21 May 2008 – 31 December 2010) and who died of PCa during the study inclusion period (21 May 2009 – 31 December 2010, Figure 1). This allowed for a minimum follow-up of one year in the SALT database.

Figure 1.

Inclusion/exclusion in study of chemotherapy use in men with castration resistant prostate cancer (PCa) in PCBaSe Sweden. Study inclusion period is the period during which a case had to die of PCa to be included. Observation period in SALT database is the period prior to death during which data on use of chemotherapy was available. Sjukhusapotekens läkemedelstillverkning (SALT)/Hospital pharmaceutical manufacturing database, an in-hospital medication database. Solid lines represents men followed diagnosed with PCa. Grey and black colors used for time with unknown and known chemotherapy status respectively. The solid lines ends in PCa death (dark grey) or death of other causes (light grey). The inclusion criteria are men dead from PCa within the study inclusion period 21 May 2009 and 31 December 2010. PCa diagnosis recorded in NPCR. Cases included: 1) Men who were diagnosed with PCa, registered in NPCR prior to the observation period in SALT database and died from PCa during the study inclusion period; and 2) Men diagnosed with PCa during the observation period in SALT database and died from PCa during the study inclusion period. Cases excluded: 3) Men who died from PCa prior to the study inclusion period; 4) Men who died from other causes during the study inclusion period; and 5) Men still alive at end of the observation period in SALT database.

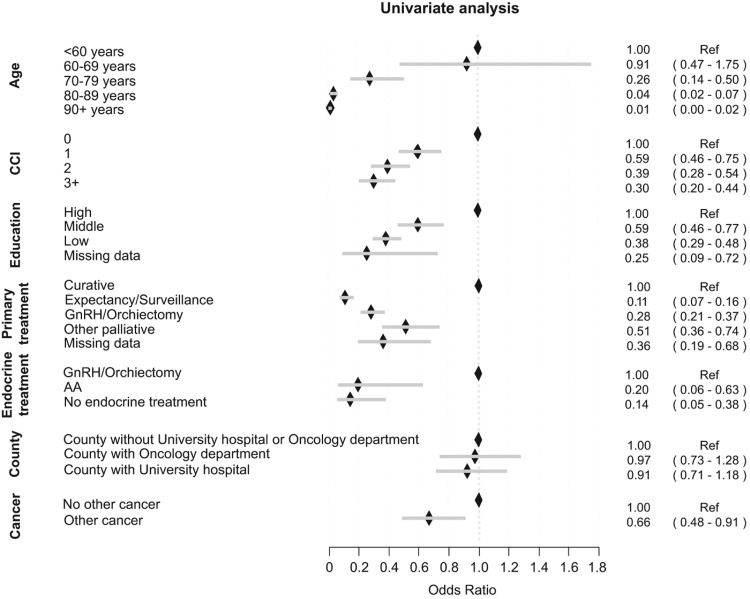

The odds of initiation of chemotherapy for various subgroups of men was compared by logistic regression and presented as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). This was done in univariate models and in a multivariate model including age, CCI, educational level, initial PCa treatment, concomitant cancer, ongoing endocrine treatment, and region. The results from univariate and multivariate analysis were very similar and therefore only the results from the univariate analysis are presented. A sensitivity analysis restricted to men who died in year 2010 was performed to ensure a longer time period when use of chemotherapy could be assessed.

Results

Chemotherapy treatment frequency and timing

A total of 2677 men died of PCa during the study inclusion period (Table I). Among these 2677 men, 556 (21%) men received chemotherapy (intravenous or peroral) detectable within the observation period in SALT database (Table II). Half of these men 283/556 (51%) received their last course of chemotherapy within six months of their death and 105/556 (19%) of patients received their last course of chemotherapy less than two months prior to death.

Table I.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of men who died from prostate cancer treated or not treated with chemotherapy in PCBaSe Sweden.

| Chemotherapy (n = 556) | No chemotherapy (n = 2121) | All cases (n = 2677) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, n (%) | |||

| < 60 years | 27 (4.9) | 16 (0.8) | 43 (1.6) |

| 60–69 years | 212 (38.1) | 138 (6.5) | 350 (13.1) |

| 70–79 years | 246 (44.2) | 552 (26.0) | 798 (29.8) |

| 80–89 years | 68 (12.2) | 1122 (52.9) | 1190 (44.5) |

| 90 + years | 3 (0.5) | 293 (13.8) | 296 (11.1) |

| Risk category at diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Low-risk | 17 (3.1) | 78 (3.7) | 95 (3.5) |

| Intermediate-risk | 52 (9.4) | 245 (11.6) | 297 (11.1) |

| High-risk | 128 (23.0) | 674 (31.8) | 802 (30.0) |

| Regionally metastatic | 85 (15.3) | 320 (15.1) | 405 (15.1) |

| Distant metastases | 268 (48.2) | 775 (36.5) | 1043 (39.0) |

| Missing data | 6 (1.1) | 29 (1.4) | 35 (1.3) |

| Endocrine treatment, n (%) | |||

| Anti-androgen | 3 (0.5) | 55 (2.6) | 58 (2.2) |

| GnRH/Orchiectomy | 549 (98.7) | 1963 (92.6) | 2512 (93.8) |

| No endocrine treatment | 4 (0.7) | 103 (4.9) | 107 (4.0) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, n (%) | |||

| CCI 0 | 370 (66.5) | 1010 (47.6) | 1380 (51.6) |

| CCI 1 | 109 (19.6) | 505 (23.8) | 614 (22.9) |

| CCI 2 | 47 (8.5) | 331 (15.6) | 378 (14.1) |

| CCI 3+ | 30 (5.4) | 275 (13.0) | 305 (11.4) |

| Educational level, n (%) | |||

| High | 136 (24.5) | 273 (12.9) | 409 (15.3) |

| Middle | 208 (37.4) | 704 (33.2) | 912 (34.1) |

| Low | 208 (37.4) | 1112 (52.4) | 1320 (49.3) |

| Missing data | 4 (0.7) | 32 (1.5) | 36 (1.3) |

| Other cancer | |||

| None | 505 (90.8) | 1840 (86.8) | 2345 (87.6) |

| Bladder/kidney | 8 (1.4) | 56 (2.6) | 64 (2.4) |

| Colorectal | 8 (1.4) | 49 (2.3) | 57 (2.1) |

| Malignant melanoma/neoplasm of skin | 12 (2.2) | 65 (3.1) | 77 (2.9) |

| Other | 22 (4.0) | 77 (3.6) | 99 (3.7) |

| Mixture of other cancers | 1 (0.2) | 34 (1.6) | 35 (1.3) |

| Region | |||

| County with University hospital | 279 (50.2) | 1100 (51.9) | 1379 (51.5) |

| County with Oncology department | 178 (32.0) | 664 (31.3) | 842 (31.5) |

| County without University hospital or Oncology department | 99 (17.8) | 357 (16.8) | 456 (17.0) |

For definition of risk category, comorbidity, educational level, see material and methods section.

Table II.

Chemotherapy regimens and timing.

| Chemotherapy (n = 556) | No chemotherapy (n = 2121) | All cases (n = 2677) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy, intravenous, n (%) | |||

| No Docetaxel + no other intravenous chemotherapy | 66 (11.9) | 2121 (100.0) | 2187 (81.7) |

| Docetaxel + no other chemotherapy | 395 (71.0) | 395 (14.8) | |

| Docetaxel + mitoxantrone | 46 (8.3) | 46 (1.7) | |

| Docetaxel + other chemotherapy | 20 (3.6) | 20 (0.7) | |

| No Docetaxel + mitoxantrone | 4 (0.7) | 4 (0.1) | |

| No Docetaxel+ other chemotherapy | 25 (4.5) | 25 (0.9) | |

| Chemotherapy, peroral, n (%) | |||

| KEES | 35 (6.3) | 35 (1.3) | |

| Cyklophosphamide | 50 (9.0) | 50 (1.9) | |

| Estramustine | 41 (7.4) | 41 (1.5) | |

| Mixture/other | 11 (2.0) | 11 (0.4) | |

| No peroral chemotherapy | 419 (75.4) | 2121 (100.0) | 2540 (94.9) |

| Prednisone, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 407 (73.2) | 510 (24.0) | 917 (34.3) |

| No | 149 (26.8) | 1611 (76.0) | 1760 (65.7) |

| Time of last dose of chemotherapy | |||

| Peroral chemotherapy | 66 (11.9) | 2121 (100.0) | 2187 (81.7) |

| Last chemo 0–1 month prior to death | 45 (8.1) | 45 (1.7) | |

| Last chemo 1–2 month prior to death | 60 (10.8) | 60 (2.2) | |

| Last chemo 2–6 months prior to death | 178 (32.0) | 178 (6.6) | |

| Last chemo 6–12 months prior to death | 128 (23.0) | 128 (4.8) | |

| Last chemo 1 + years prior to death | 79 (14.2) | 79 (3.0) |

KEES, ketokonazole, estramustine, etoposide, sendoxan/cyclophosphamide [17].

Chemotherapy regimens

A total of 19 different chemotherapy agents were utilized (Table III). The majority of men received only first line single docetaxel 395/556 (71%) (Table II). Some men received docetaxel followed by second line treatment with mitoxantrone 46/556 (8%) or other second line intravenous cytostatics (carboplatin, etoposide, gemcitabin, doxorubicin) 20/556 (4%). The four patients (1%) who received only mitoxantrone, had probably received docetaxel as first line treatment but before the observation period in the SALT database. Based on this assumption, a total of 465/556 (84%) men had received some docetaxel containing regimen. A small group, 66/556 men (12%) received only peroral chemotherapy out of which single cyclophosphamide was most common followed by single estramustine and KEES (peroral combination therapy regimen including ketoconazole, estramustine, etoposide and cyclophosphamide (Table II) [17]. The majority of men, 75/105 (71%), who received chemotherapy less than two months prior to death received docetaxel, 14/105 (13%) men received mitoxantrone, 1/105 (1%) man received docetaxel and mitoxantrone and 15/105 (14%) men received other types of chemotherapy. Among the 556 chemotherapy treated men, 51 (9%) had a second primary cancer (Table I).

Table III.

The 10 most commonly used chemotherapy agents.

| Agent | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Docetaxel |

| 2 | Mitoxantrone |

| 3 | Gemcitabine |

| 4 | Carboplatin |

| 5 | 5-Fluorouracil |

| 6 | Etoposide |

| 7 | Doxorubicine |

| 8 | Paclitaxel |

| 9 | Cisplatin |

| 10 | Cyclophosphamide |

Chemotherapy treatment, tumor characteristics and primary curative treatment

Most men (86%) who received chemotherapy had high risk, regionally, or distant metastatic PCa at diagnosis (Table I). Men primarily treated with curative intent had a higher likelihood of chemotherapy treatment (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The likelihood of initiation of chemotherapy for various subgroups of men who died from PCa 2009–2010 expressed as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. For definition of Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) and education, see materials and methods section. Primary treatment; other palliative, e.g. transurethral resection of the prostate, steroids, analgesics. Endocrine treatment – Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone analogues (GnRH).

Chemotherapy treatment and age

Median age at start of chemotherapy was 69.8 years (Q1 = 65.2, Q3 = 75.4). The majority of treated men 458/556 (82%) were between 60 and 79 years old (Figure 2). A higher proportion of younger men compared to older men were treated with chemotherapy (Figure 2). In total 239/393 (61%) of men < 70 years received chemotherapy in contrast to men between 70 and 79 years where 246/798 (31%) received chemotherapy and only 71/1486 (5%) of men over the age of 80 (Table I).

Chemotherapy treatment and comorbidity

A higher proportion of men with CRPC with no or little comorbidity (CCI 0-1) 479/556 (86%) received chemotherapy than men with high comorbidity (CCI 2+) 77/556 (14%) (Figure 2, Table I). A majority of non-treated men, 1515/2121 (71%) also had little or no comorbidity. In total only 479/1994 (24%) of men with CRPC and little or no comorbidity (CCI 0-1) received chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy treatment, educational level, regional differences and place of residence

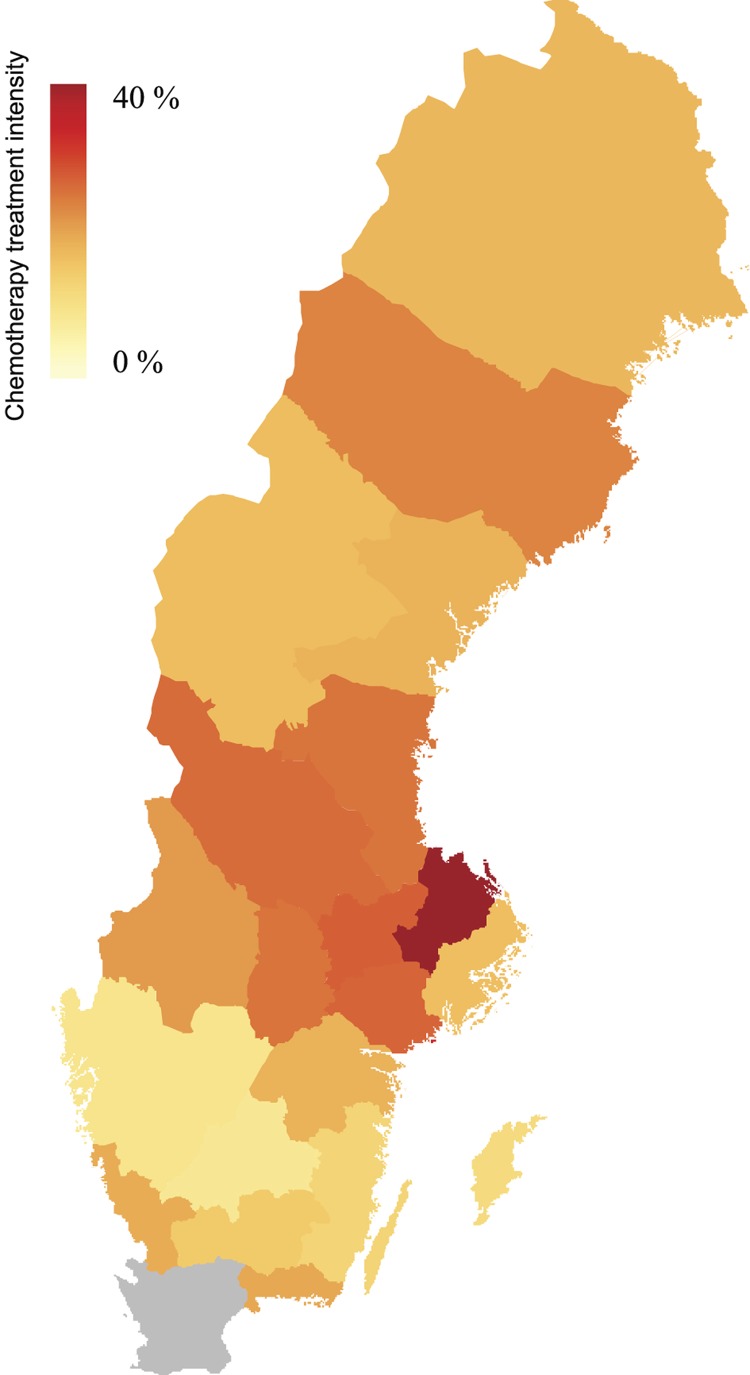

Men with high educational level were more likely to receive chemotherapy treatment than men with low educational level (Figure 2). There were marked differences between counties in treatment intensity (Figure 3). However, place of residence, i.e. proximity to university hospital or oncology department had no influence on the likelihood of being treated with chemotherapy (Figure 2).

Figure 3.

Differences between counties in use of intravenous docetaxel chemotherapy treatment, i.e percentage of men dying from prostate cancer who received intravenous docetaxel chemotherapy prior to death. Data from Skåne county is missing (gray).

Endocrine treatment

As expected, and according to guidelines, almost all 549/556 (99%) of men treated with chemotherapy were also treated with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT; GnRH or bilateral orchiectomy). This was also true for the majority of men not receiving chemotherapy 1963/2121 (93%). The reason that 103 (5%) men not treated with chemotherapy were registered as not receiving ADT was most likely explained by the fact that many of these men resided in nursing homes and ADT was therefore not registered in the Prescribed Drug Register. Besides use in combination with chemotherapy, prednisone was also used in late palliative care which probably explains why 510/2121 (24%) of men not treated with chemotherapy received prednisone (Table II).

Discussion

In this population-based nationwide study, the majority of men younger than 70 years (61%) with CRPC received chemotherapy in contrast to 30% of men between 70 and 79 years and 5% of men over the age of 80 years. Treatment was often administered shortly prior to death. Men primarily treated with curative intent, men with low comorbidity and men with high educational level were more often treated with chemotherapy. There were marked geographical differences in the use of chemotherapy.

Strengths of our study included the population-based nationwide cohort within NPCR including virtually all men who died of PCa in Sweden during the study inclusion period 2009–2010. Additional information on comorbidity, demographic and socio-economic factors were obtained from other registers in PCBaSe [11]. The chemotherapy register included 27 of 30 (90%) Swedish hospital pharmacies, making it highly representative. A potential limitation of our study is that some oncology departments may have prepared their chemotherapy in-house and not at the central hospital pharmacy and thus not registered in the SALT database. This was probably rare, due to national health and safety regulations for chemotherapy administration. Another weakness of our data set was that chemotherapy use could only be assessed during the last 31 months of a man´s life as the drug register is cleared from all personal information three years after registration. Thus, some men may have received chemotherapy treatment before the observation period in the SALT database [3,18]. These shortcomings notwithstanding, our results provide an insight into the use of chemotherapy for CRPC in a ‘real-life’ setting in a nationwide, population-based cohort.

The treatment intensity found in our study is in line with previously published mainly single institution experiences with 14–37% of men with CRPC receiving chemotherapy [7–10]. This is in contrast to treatment intensity in other common tumor types such as breast- and colorectal cancer in which 30–75% of patients receive palliative chemotherapy [19–22].

The vast majority of men with CRPC in our study received a docetaxel containing regimen complying with guidelines [3]. Many other types of chemotherapy agents were also utilized and several of them have only weak evidence in support of their use. Several patients received second line chemotherapy with mitoxantrone plus prednisone, the benefits of which are minimal as demonstrated in the TAX 327 trial [5].

Chemotherapy among men with CRPC was often administered late in life when survival time was short, in line with previous studies in prostate, breast, colorectal and lung cancer [23,24]. Chemotherapy treatment shortly prior to death might be detrimental to quality of life when there is little hope of clinical benefit and should therefore be avoided. The availability of supportive/palliative care units was recently shown to decrease futile chemotherapy use when survival time was short [25].

Younger men with CRPC were more likely to receive chemotherapy than older men, in line with earlier studies on prostate, breast and colorectal cancer [22,26–28] and in our study 61% of men below the age of 70 years received chemotherapy. Many men with CRPC are old, however, healthy old men have similar treatment outcomes as younger men [29,30] and old men are equally motivated to receive chemotherapy for a survival benefit [31]. Treatment decisions should be made on the basis of biological age and comorbidity, a key predictor of life expectancy. A total of 1515 (71%) of men who did not receive chemotherapy in this study had little or no comorbidity, indicating undertreatment. A geriatric assessment tool including biological and clinical correlates of aging may improve decision-making in old cancer patients [32,33].

Men with high educational level were more likely to receive chemotherapy than men with low education. These results are in line with previous studies of prostate, lung, breast and colorectal cancer [34–37]. Men with high education level are also more likely to receive primary curative treatment [35]. Thus, healthcare seeking behavior and patient-clinician interactions related to socioeconomic status contribute to inequalities in the management of men with PCa both in the curative and palliative setting.

There were marked differences between counties in the use of chemotherapy for men with CRPC, but proximity to university hospital or oncology department had no impact on the likelihood of chemotherapy treatment. Some of these geographical differences are probably explained by the number of uro-oncologists in the region.

In conclusion, despite strong evidence that docetaxel prolongs life and offers palliation in a substantial proportion of men with CRPC only 31% of men between 70 and 79 years, dying from PCa during 2009–2010 in Sweden, received chemotherapy in contrast to men younger than 70 years of whom 61% received chemotherapy. Chemotherapy was often administered shortly prior to death. Our data indicate an undertreatment in old men with CRPC who are in good general health.

Acknowledgements

This project was made possible by the continuous work of the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden (NPCR Swe) steering group: Pär Stattin (chairman), Anders Widmark, Camilla Thellenberg, Ove Andrén, Anna Bill-Axelson, Ann-Sofi Fransson, Magnus Törnblom, Stefan Karlsson, Marie Hjälm- Eriksson, Bodil Westman, Bill Petersson, David Robinsson, Mats Andén, Jan-Erik Damber, Jonas Hugosson, Ingela Franck Lissbrant, Maria Nyberg, Göran Ahlgren, Ola Bratt, René Blom, Rolf Lundgren, Lars Egevad, Calle Waller, Jan-Erik Johansson, Olof Akre, Per Fransson, Eva Johansson, Fredrik Sandin, Hans Garmo, Mats Lambe, Karin Hellström, Erik Holmberg and Annette Wigertz. This study was supported by funding from Swedish Research Council 825-2010-5950.

Declaration of interest: The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. Anders Widmark is working part time as medical advisor for Sanofi Oncology, Sweden and has received travel and lecture honorarium from Astellas. Ingela Franck Lissbrant, Hans Garmo and Pär Stattin have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, Horti J, Pluzanska A, Chi KN, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petrylak DP, Tangen CM, Hussain MH, Lara PN, Jones JA, Taplin ME, et al. Docetaxel and estramustine compared with mitoxantrone and prednisone for advanced refractory prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1513–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Joniau S, Mason M, Matveev V, et al. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: Treatment of advanced, relapsing, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2011;59:572–83. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fossa SD, Jacobsen AB, Ginman C, Jacobsen IN, Overn S, Iversen JR, et al. Weekly docetaxel and prednisolone versus prednisolone alone in androgen-independent prostate cancer: A randomized phase II study. Eur Urol. 2007;52:1691–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.01.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berthold DR, Pond GR, de Wit R, Eisenberger M, Tannock IF. Survival and PSA response of patients in the TAX 327 study who crossed over to receive docetaxel after mitoxantrone or vice versa. Ann Oncol. 2008;19:1749–53. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seruga B, Tannock IF. Chemotherapy-based treatment for castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3686–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.34.3996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chin SN, Wang L, Moore M, Sridhar SS. A review of the patterns of docetaxel use for hormone-resistant prostate cancer at the Princess Margaret Hospital. Curr Oncol. 2010;17:24–9. doi: 10.3747/co.v17i2.482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berruti A, Dogliotti L, Bitossi R, Fasolis G, Gorzegno G, Bellina M, et al. Incidence of skeletal complications in patients with bone metastatic prostate cancer and hormone refractory disease: Predictive role of bone resorption and formation markers evaluated at baseline. J Urol. 2000;164:1248–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirby M, Hirst C, Crawford ED. Characterising the castration-resistant prostate cancer population: A systematic review. Int J Clin Pract. 2011;65:1180–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2011.02799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris V, Lloyd K, Forsey S, Rogers P, Roche M, Parker C. A population-based study of prostate cancer chemotherapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2011;23:706–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2011.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Hemelrijck M, Wigertz A, Sandin F, Garmo H, Hellstrom K, Fransson P, et al. Cohort Profile: The National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden and Prostate Cancer data Base Sweden 2.0. Int J Epidemiol E-pub. 2012 May 4; doi: 10.1093/ije/dys068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohler J, Bahnson RR, Boston B, Busby JE, D’Amico A, Eastham JA, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: Prostate cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:162–200. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Godtman R, Holmberg E, Stranne J, Hugosson J. High accuracy of Swedish death certificates in men participating in screening for prostate cancer: A comparative study of official death certificates with a cause of death committee using a standardized algorithm. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2011;45:226–32. doi: 10.3109/00365599.2011.559950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fall K, Stromberg F, Rosell J, Andren O, Varenhorst E. Reliability of death certificates in prostate cancer patients. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2008;42:352–7. doi: 10.1080/00365590802078583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berglund A, Garmo H, Tishelman C, Holmberg L, Stattin P, Lambe M. Comorbidity, treatment and mortality: A population based cohort study of prostate cancer in PCBaSe Sweden. J Urol. 2011;185:833–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jellvert A, Lissbrant IF, Edgren M, Ovferholm E, Braide K, Olvenmark AM, et al. Effective oral combination metronomic chemotherapy with low toxicity for the management of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Exp Ther Med. 2011;2:579–84. doi: 10.3892/etm.2011.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armstrong AJ, Garrett-Mayer E, de Wit R, Tannock I, Eisenberger M. Prediction of survival following first-line chemotherapy in men with castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:203–11. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sorbye H, Pfeiffer P, Cavalli-Bjorkman N, Qvortrup C, Holsen MH, Wentzel-Larsen T, et al. Clinical trial enrollment, patient characteristics, and survival differences in prospectively registered metastatic colorectal cancer patients. Cancer. 2009;115:4679–87. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Pool AE, Damhuis RA, Ijzermans JN, de Wilt JH, Eggermont AM, Kranse R, et al. Trends in incidence, treatment and survival of patients with stage IV colorectal cancer: A population-based series. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:56–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song X, Zhao Z, Barber B, Gregory C, Wang PF, Long SR. Treatment patterns and metastasectomy among mCRC patients receiving chemotherapy and biologics. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27:123–30. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.536912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morimoto L, Coalson J, Mowat F, O’Malley C. Factors affecting receipt of chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. Int J Womens Health. 2010;2:107–22. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s9125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andreis F, Rizzi A, Rota L, Meriggi F, Mazzocchi M, Zaniboni A. Chemotherapy use at the end of life. A retrospective single centre experience analysis. Tumori. 2011;97:30–4. doi: 10.1177/030089161109700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asola R, Huhtala H, Holli K. Intensity of diagnostic and treatment activities during the end of life of patients with advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100:77–82. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9224-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Magarotto R, Lunardi G, Coati F, Cassandrini P, Picece V, Ferrighi S, et al. Reduced use of chemotherapy at the end of life in an integrated-care model of oncology and palliative care. Tumori. 2011;97:573–7. doi: 10.1177/030089161109700506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schonberg MA, Marcantonio ER, Li D, Silliman RA, Ngo L, McCarthy EP. Breast cancer among the oldest old: Tumor characteristics, treatment choices, and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2038–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.9796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dotan E, Browner I, Hurria A, Denlinger C. Challenges in the management of older patients with colon cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:213–24. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2012.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson J, Van Poppel H, Bellmunt J, Miller K, Droz JP, Fitzpatrick JM. Chemotherapy for older patients with prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2007;99:269–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aapro MS. Management of advanced prostate cancer in senior adults: The new landscape. Oncologist. 2012;17((Suppl 1)):16–22. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-S1-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Italiano A, Ortholan C, Oudard S, Pouessel D, Gravis G, Beuzeboc P, et al. Docetaxel-based chemotherapy in elderly patients (age 75 and older) with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2009;55:1368–75. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yellen SB, Cella DF, Leslie WT. Age and clinical decision making in oncology patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:1766–70. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.23.1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Droz JP, Balducci L, Bolla M, Emberton M, Fitzpatrick JM, Joniau S, et al. Background for the proposal of SIOG guidelines for the management of prostate cancer in senior adults. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;73:68–91. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fitzpatrick JM. Optimizing the management of prostate cancer in senior adults: Call to action. Oncologist. 2012; 17((Suppl 1)):1–3. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-S1-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myrdal G, Lamberg K, Lambe M, Stahle E, Wagenius G, Holmberg L. Regional differences in treatment and outcome in non-small cell lung cancer: A population-based study (Sweden) Lung Cancer. 2009;63:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berglund A, Garmo H, Robinson D, Tishelman C, Holmberg L, Bratt O, et al. Differences according to socioeconomic status in the management and mortality in men with high risk prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cavalli-Bjorkman N, Lambe M, Eaker S, Sandin F, Glimelius B. Differences according to educational level in the management and survival of colorectal cancer in Sweden. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eaker S, Halmin M, Bellocco R, Bergkvist L, Ahlgren J, Holmberg L, et al. Social differences in breast cancer survival in relation to patient management within a National Health Care System (Sweden) Int J Cancer. 2009;124:180–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]