Summary

The aim of this study was to look for differences in the power spectra and in EEG connectivity measures between patients in the vegetative state (VS/UWS) and patients in the minimally conscious state (MCS).

The EEG of 31 patients was recorded and analyzed. Power spectra were obtained using modern multitaper methods. Three connectivity measures (coherence, the imaginary part of coherency and the phase lag index) were computed. Of the 31 patients, 21 were diagnosed as MCS and 10 as VS/UWS using the Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R). EEG power spectra revealed differences between the two conditions. The VS/UWS patients showed increased delta power but decreased alpha power compared with the MCS patients. Connectivity measures were correlated with the CRS-R diagnosis; patients in the VS/UWS had significantly lower connectivity than MCS patients in the theta and alpha bands.

Standard EEG recorded in clinical conditions could be used as a tool to help the clinician in the diagnosis of disorders of consciousness.

Keywords: connectivity, disorders of consciousness, imaginary part of coherency, minimally conscious state, phase lag index, vegetative state

Introduction

Patients emerging from coma can go through different states of consciousness. The vegetative state/unresponsive wakefulness syndrome (VS/UWS) (1) is characterized by wakefulness but absence of both self and environmental awareness (2). ‘The minimally conscious state (MCS) is a condition of severely altered consciousness in which minimal but definite behavioral evidence of self or environmental awareness is demonstrated’ (3). The importance of a correct diagnosis of these two states is twofold. First, MCS patients have better recovery prospects than VS/UWS patients (4). Second, different treatments are needed, depending on the patient’s state of consciousness.

In clinical practice, several scales (5), based on behavioral reactions to different stimuli, are used to evaluate the state of consciousness. The Glasgow Coma Scale (6) is widely used, however, recent studies show that for chronic patients, the use of more advanced scales such as the Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R) (7) considerably improves the diagnosis of patients emerging from coma (8).

Nevertheless, bedside evaluation remains difficult, requires expertise and may be dependent on the subjectivity of the assessor. Thus, an automated method providing a paraclinical measure that allows a correct diagnosis of VS/UWS and MCS patients would prove helpful (9).

Through the use of external stimulations in passive and active paradigms with different imaging and neurophysiological tools, several steps have been taken towards this goal.

Studies based on passive stimulation have shown that MCS patients display larger and more extensive activations than VS/UWS patients (10–14). However, VS/UWS patients, too, can display significant activations, showing that they retain some islands of preserved cognitive function (15). Proof of higher level cognitive function can be obtained with active stimulation (16–18), but in this case absence of activation does not constitute proof of absence of cognitive function, given that it is not possible to know whether the patient tried to perform the task or not.

Hence, researchers are exploring resting-state activity, which is stimulus independent and therefore does not depend on the reaction of the patient.

An advance in this direction has been achieved using the bispectral index, which was found to be lower in VS/UWS patients than in MCS patients (19).

Although these results are promising, what they provide is only a general measure without physiological detail; thus, a logical step forward would be to identify more precisely correlates of consciousness in the EEG signal.

The level of integration and connection of networks in the brain can be assessed by computing the connectivity between electrode sites. Most EEG clinical studies use coherence (C) as a measure of connectivity between electrode sites. However, C values must be interpreted carefully since they can be contaminated by artifactual correlations between electrodes caused by the reference, and by volume conduction. It has been shown that C values are high for neighboring electrodes then decrease as the distance between electrodes increases (20,21). Furthermore, changes in C between two electrodes can be a reflection of power or phase variations at the reference site (22,23). Finally, C measures the correlation of both phase and amplitude simultaneously; it is therefore difficult to assess the individual contribution of these two factors.

Efforts by researchers to address these pitfalls have led to a flourishing algorithmic culture. Specific phase approaches have been proposed, such as phase-locking statistics (24) and phase coherence (25), however these do not resolve the volume conduction problem. This issue has been addressed with a modified measure of C that takes into account only the imaginary part of coherency (IC) (26). This approach is motivated by the fact that volume conductions are instantaneous, i.e. zero-lagged, and therefore only contribute to the real part of coherency. Although some neural information might be lost in the process of removing the real part of coherency, the benefit is that the imaginary part explains only true brain interactions. The influence of the volume conduction is also minimized by using the phase lag index (PLI) (27), which depends neither on the signal amplitude nor on the amplitude of the phases and takes into account only non-zero-lagged phase coupling.

The objective of this study was to investigate the possible differences in low-density EEG recordings of MCS and VS/UWS patients made in resting-state conditions. In the following sections we describe the methods that were used, the patient sample, the pre-processing steps and how the power spectra and connectivity measures were computed. The electrode montages are also described. The results presented refer to three main areas: the comparison between MCS and VS/UWS, the etiology analysis and the longitudinal analysis.

Materials and methods

We prospectively studied 31 brain-damaged patients with disorders of consciousness (DOCs). Three MCS patients (patients n. 13, 23 and 31, see Table 1) were excluded due to movement or ocular artifacts (only patients showing at least 10 artifact-free 4-second epochs were included). Of the 28 DOC patients included, 15 were studied in the acute/subacute setting (<3 months post-injury); 15 were non-traumatic; 18 patients were diagnosed as MCS (15 males, aged 39±11 years; 8 chronic >3 months post-injury; 7 non-traumatic) and 10 as VS/UWS (6 males, 50±13 years; 5 chronic; 8 non-traumatic). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical School of the University of Liège. Informed consent was obtained from the legal surrogates of the patients. All the patients were evaluated at the University Hospital of Liège, Liège, Belgium. The diagnosis of the patients was based on repeated CRS-R assessments (28). The clinical and demographic data are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical information

| State | n° | Age | G | CRS-R | Etio | Interval since insult | AfS | VfS | Mfs | OfS | CS | AS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VS | 1 | 62 | M | 6 | A | 260 | AS | N | FW | ORM | N | Eo |

| 2 | 35 | F | 7 | A | 125 | AS | BtT | FW | ORM | N | Eo | |

| 3 | 45 | F | 4 | CVA | 77 | AS | N | AP | V | N | Eo | |

| 4 | 47 | M | 3 | A | 7 | AS | N | N | ORM | N | EoWS | |

| 5 | 54 | M | 4 | A | 169 | AS | N | AP | ORM | N | EoWS | |

| 6 | 61 | M | 4 | E | 16 | AS | N | FW | ORM | N | EoWS | |

| 7 | 37 | M | 7 | A | 262 | AS | F | AP | ORM | N | Eo | |

| 8 | 31 | M | 3 | T | 184 | N | N | AP | ORM | N | Eo | |

| 9 | 69 | F | 3 | T | 8 | AS | N | AP | ORM | N | EoWS | |

| 10 | 61 | F | 5 | A | 34 | N | N | FW | ORM | N | Eo | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| MCS | 11 | 28 | M | 11 | T | 2299 | RMC | VP | FW | ORM | N | Eo |

| 12 | 31 | M | 11 | A | 604 | AS | VP | AP | V | N | Eo | |

| 13 | 28 | F | 11 | T | 800 | RMC | VP | FW | V | N | Eo | |

| 14 | 48 | M | 18 | CVA | 43 | RMC | OR | AMR | V | Nfl | Eo | |

| 15 | 35 | M | 9 | T | 8602 | AS | VP | FW | V | N | Eo | |

| 16 | 62 | M | 8 | T | 66 | N | PEM | FW | ORM | N | Eo | |

| 17 | 31 | F | 11 | CVA | 44 | LtS | PEM | FW | V | N | Eo | |

| 18 | 36 | M | 6 | T | 340 | N | VP | N | ORM | N | Eo | |

| 19 | 48 | M | 14 | T | 16 | RMC | VS | LNS | IV | F | Eo | |

| 20 | 24 | M | 8 | T | 71 | N | VP | FW | ORM | N | Eo | |

| 21 | 46 | M | 21 | CVA | 569 | CMC | OR | AMR | IV | Nfl | A | |

| 22 | 24 | M | 8 | T | 318 | RMC | VP | FW | ORM | N | Eo | |

| 23 | 41 | M | 12 | A | 47 | RMC | VP | N | V | Nfl | Eo | |

| 24 | 37 | M | 11 | T | 128 | RMC | VP | FW | ORM | N | Eo | |

| 25 | 38 | M | 10 | A | 4542 | N | VP | AMR | ORM | N | Eo | |

| 26 | 44 | F | 10 | CVA | 80 | AS | VP | FW | V | N | Eo | |

| 27 | 58 | M | 9 | T | 56 | AS | VP | FW | ORM | N | Eo | |

| 28 | 35 | M | 14 | T | 24 | RMC | VP | OM | V | N | Eo | |

| 29 | 53 | F | 12 | T | 80 | RMC | VP | FW | ORM | Nfl | Eo | |

| 30 | 42 | F | 15 | CVA | 23 | RMC | VP | FW | ORM | Nfl | Eo | |

| 31 | 21 | F | 10 | T | 743 | AS | VP | FW | V | N | Eo | |

Abbrevations: Age (years); G=gender; CRS-R= Coma Recovery Scale – Revised, total score; Etio=Etiology; A=anoxic; T=traumatic; CVA=cerebrovascular accident; E=encephalitis; Interval since insult (days); AfS=Auditory Function Scale; CMC=consistent movement to command; RMC=reproducible movement to command; LtS=localization to sound; AS=auditory startle ; N=none; VfS=Visual Function Scale; OR=object recognition; VP= visual pursuit; F=fixation; BtT=blink to threat; MfS=Motor Function Scale; AMR=automatic motor response; OM=object manipulation; FW=flexion withdrawal; AP=abnormal posturing; N=none; OfS=Oromotor/Verbal Function Scale; IV=intelligible verbalization; V=vocalization; ORM=oral reflexive movement; CS=Communication Scale; NfI=non functional:intentional; N=none; AS=Arousal Scale; A=attention; Eo=eye opening without stimulation; EoWS=eye opening with stimulation.

The EEG was recorded for 15 minutes in resting-state conditions at 500 Hz sampling rate using a Vamp amplifier (Brain Products GmbH, Munich, Germany). Ten cephalic EEG recordings (using the 10–20 positioning system Fz, F3, F4, Cz, C3, C4, Pz, P3, P4, Oz; referenced to the nose) and two electrooculograms, one over the right eye and one below the left eye, and two chin electromyography (EMG) recordings were obtained.

The EEG recordings were visually inspected for artifact removal using the FASST toolbox (29) and band-passed into three frequency bands: delta (0.5–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), using a first-order Butterworth filter. A low-order filter was chosen to minimize phase distortions due to filtering. Artifact-free epochs lasting at least 4 seconds were extracted and power spectra, C, IC (26) and PLI (27) were computed for each epoch and next averaged over all data for each subject and for different combinations of electrodes.

The EEG and EMG power spectra were computed for each epoch with a frequency resolution of 1 Hz. The average power spectra were then taken over all the epochs for each subject and for each frequency band. A multitaper method (30) was used with seven discrete prolate spheroidal sequences as data tapers. Relative power values were obtained for each band by computing the fraction of power at each band divided by the sum of power across 1–48 Hz. We calculated mean relative power spectra for frontal (i.e., F3 Fz F4), posterior (P3 Pz P4), left hemisphere (F3 C3 P3) and right hemisphere (F4 C4 P4) derivations.

Connectivity studies measured C, IC (26) and PLI (27) obtained from the instantaneous amplitude A(tk) and the instantaneous phase ϕ(tk) which are derived from the analytical signal z(t):

where x(t) represents the real signal while x̃(t) is the Hilbert transform of x(t), a complex value. The instantaneous amplitudes and phases were computed directly from the real signal and the corresponding Hilbert transform:

Let Ai(tk) (respectively Aj(tk)) and ϕi(tk) (respectively ϕj(tk)) be the instantaneous amplitude and phase at channel i (respectively j) and discrete time tk. The PLI, the C (i.e., the absolute value of coherency) and the IC between channels i and j at time tk were given by:

where Δϕi,j (tk) = ϕi (tk) – ϕj (tk) is the phase difference between the two channels, sign(x) is the sign of x (i.e., 1 or −1), <x> indicates the average of x, and |x| the absolute value.

These measures were computed for each epoch (values were next averaged over all epochs), for each frequency band and for each subject. All three connectivity measures were bounded between 0 (no connectivity) and 1 (total connectivity). The aim in using the IC and the PLI was to diminish the influence of common sources due to the volume conduction effect (20). The main concept underlying the PLI is that of the asymmetry of the phase difference distribution, which implies that in the case of coupling between two signals, the first signal should be consistently either in phase advance or in phase delay in relation to the second signal. Since volume conduction is instantaneous, phase differences that center around 0 modulo π are discarded and therefore perfect phase matching signals have a PLI of 0 while two signals with a constant phase lag would have a PLI of 1. The IC removes the effect of volume conduction by removing the real part of coherency which is responsible for instantaneous contributions. However, it differs from the PLI in that it is dependent on the amplitude of the signals and on the amplitude of the phase differences.

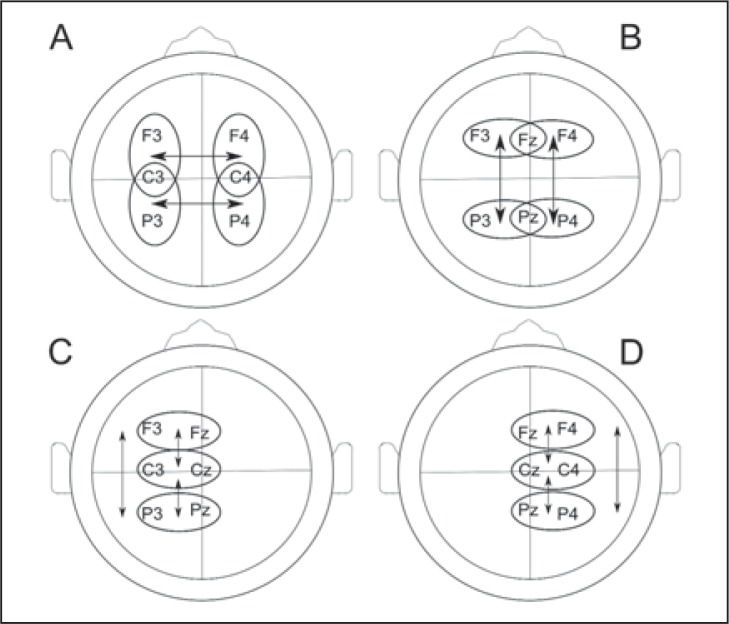

For connectivity assessments, data were analyzed using bipolar montages, avoiding influence of the reference, and assessing: i) left-right inter-hemispheric (employing F3 C3 P3, F4 C4 P4), ii) frontal-to-posterior (i.e., F3 Fz F4 P3 Pz P4), iii) left-hemisphere (F3 C3 P3) and iv) right hemisphere (F4 C4 P4) connectivity measures. Average connectivity values were computed on all these subsets for the different frequency bands. Averages were computed for all relevant connections. Bipolar montages are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Representative bipolar montages of (A) inter-hemispheric, (B) frontal-to-posterior (C) left hemisphere and (D) right hemisphere connectivity measurements

Statistical analyses were performed in Matlab R2007b (MATLAB version 7.5, MathWorks Inc., Natick, Massachusetts). Permutation testing (10000 permutations) compared relative power spectra for frontal, posterior, left and right averaged electrodes and connectivity measures for frontal-to-posterior, left-right inter-hemispheric, left-hemisphere and right-hemisphere montages, looking for the effect of time (acute/subacute vs chronic), etiology (traumatic vs non-traumatic) and diagnosis (MCS vs VS/UWS). Since most of the VS/UWS patients were non-traumatic, the effect of etiology was assessed only in the MCS patients.

The results were thresholded for significance at p<0.05 and corrected for multiple comparisons. In the following, p<0.05* designates a significant result which does not hold after multiple comparison correction and p<0.05** designates a significant result after multiple comparison correction.

Results

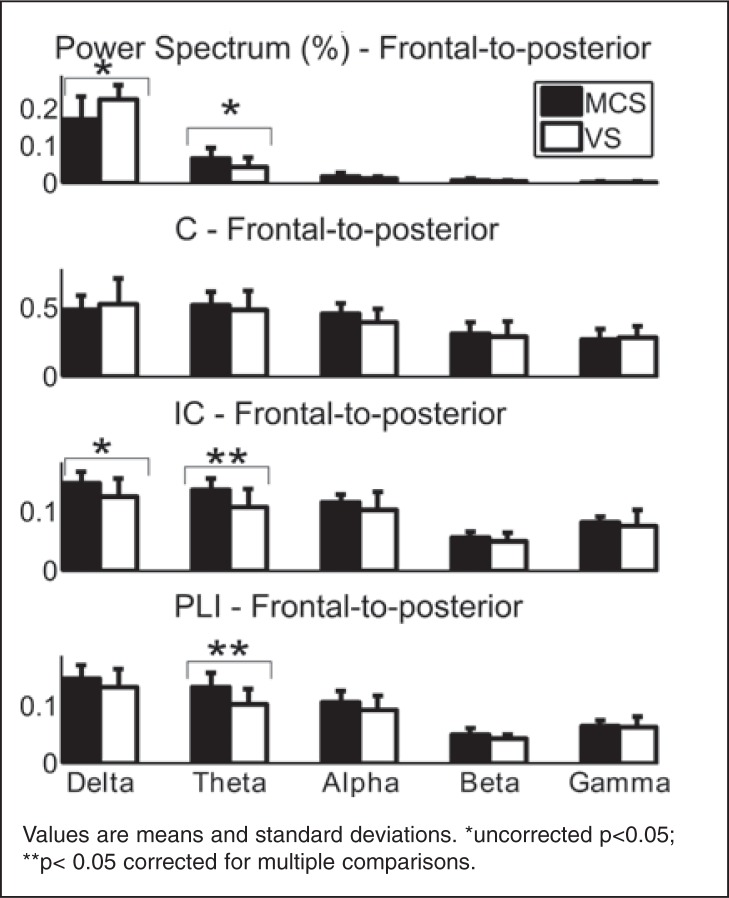

Relative power spectra were higher in the VS/UWS patients as compared to the MCS patients in the delta band for all electrodes. There was a marked difference for right hemisphere electrodes (0.223±0.04; 0.165±0.07; p<0.05**).

Relative power spectra were higher in MCS patients as compared to VS/UWS patients in the alpha band for all electrodes, again with a marked difference for right hemisphere electrodes (0.0173±0.007; 0.0106±0.006; p<0.05**).

None of the frequency bands in EEG and EMG showed any difference between acute/subacute and chronic DOC patients. No differences were found between traumatic and non-traumatic DOC patients.

Connectivity measures (C, IC and PLI) showed no differences between acute/subacute and chronic DOC patients or between traumatic and non-traumatic etiology. Connectivity assessments based on classical coherence showed no difference between diagnostic groups for any frequency band. There was a higher frontal-to-posterior connectivity in the MCS as compared to the VS/UWS group in the theta band as measured by the PLI (0.127±0.03; 0.103±0.03; p<0.05**) and the IC (0.134±0.02; 0.108±0.03; p<0.05**). The PLI also identified a higher alpha connectivity between hemispheres (0.0995±0.01; 0.0869±0.009; p<0.05**).

The power and connectivity results are illustrated in Figure 2, and numerical details are provided in Tables 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Power spectra (at posterior location), coherence, imaginary part of coherency and phase lag index (of the left hemisphere) in patients in the minimally conscious state (MCS, n=18) and patients in the vegetative/unresponsive state (VS/UWS, n=10)

Table 2.

Power spectra and significance between patients in the minimally conscious state and patients in the vegetative/unresponsive state in frontal, posterior, left and right hemisphere derivations and EMG.

| Comparison MCS-VS/UWS | sig | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| MCS | VS/UWS | ||

| Frontal | |||

| Delta | 0.172 ± 0.07 | 0.22 ± 0.04 | * |

| Theta | 0.0523 ± 0.02 | 0.0412 ± 0.03 | - |

| Alpha | 0.0142 ± 0.005 | 0.011 ± 0.006 | - |

| Posterior | |||

| Delta | 0.171 ± 0.06 | 0.224 ± 0.04 | * |

| Theta | 0.0648 ± 0.03 | 0.0435 ± 0.03 | * |

| Alpha | 0.0176 ± 0.008 | 0.0115 ± 0.005 | * |

| Left hemisphere | |||

| Delta | 0.173 ± 0.07 | 0.221 ± 0.04 | * |

| Theta | 0.0589 ± 0.03 | 0.0409 ± 0.03 | - |

| Alpha | 0.0154 ± 0.007 | 0.0109 ± 0.005 | * |

| Right hemisphere | |||

| Delta | 0.165 ± 0.07 | 0.223 ± 0.04 | ** |

| Theta | 0.058 ± 0.02 | 0.0409 ± 0.03 | * |

| Alpha | 0.0173 ± 0.007 | 0.0106 ± 0.006 | ** |

| EMG | |||

| Delta | 0.113 ± 0.08 | 0.0848 ± 0.09 | - |

| Theta | 0.0348 ± 0.02 | 0.0272 ± 0.02 | - |

| Alpha | 0.0166 ± 0.01 | 0.0211 ± 0.01 | - |

Abbreviations: MCS=minimally conscious state; VS/UWS=vegetative state

Values are means and standard deviations.

uncorrected p<0.05;

**p<0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons

Table 3.

Connectivity comparisons between patients in the minimally conscious state and patients in the vegetative/unresponsive state.

| PLI | sig | IC | sig. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCS | VS | MCS | VS | |||

| Inter hemisphere | ||||||

| Delta | 0.133 +/− 0.02 | 0.151 +/− 0.04 | - | 0.138 +/− 0.02 | 0.149 +/− 0.02 | - |

| Theta | 0.108 +/− 0.02 | 0.108 +/− 0.03 | - | 0.118 +/− 0.02 | 0.111 +/− 0.02 | - |

| Alpha | 0.0995 +/− 0.01 | 0.0869 +/− 0.009 | ** | 0.114 +/− 0.02 | 0.0994 +/− 0.01 | * |

| Frontal-to-posterior | ||||||

| Delta | 0.144 +/− 0.02 | 0.133 +/− 0.03 | - | 0.147 +/− 0.02 | 0.127 +/− 0.03 | * |

| Theta | 0.127 +/− 0.03 | 0.103 +/− 0.03 | ** | 0.134 +/− 0.02 | 0.108 +/− 0.03 | ** |

| Alpha | 0.101 +/− 0.02 | 0.0918 +/− 0.03 | - | 0.114 +/− 0.01 | 0.103 +/− 0.03 | - |

| Left hemisphere | ||||||

| Delta | 0.155 +/− 0.03 | 0.155 +/− 0.03 | - | 0.137 +/− 0.02 | 0.122 +/− 0.03 | * |

| Theta | 0.136 +/− 0.03 | 0.113 +/− 0.02 | * | 0.12 +/− 0.03 | 0.1 +/− 0.02 | * |

| Alpha | 0.114 +/− 0.02 | 0.1 +/− 0.02 | * | 0.107 +/− 0.01 | 0.0971 +/− 0.02 | - |

| Right hemisphere | ||||||

| Delta | 0.158 +/− 0.03 | 0.157 +/− 0.03 | - | 0.128 +/− 0.01 | 0.121 +/− 0.02 | - |

| Theta | 0.135 +/− 0.03 | 0.124 +/− 0.03 | - | 0.114 +/− 0.02 | 0.104 +/− 0.02 | - |

| Alpha | 0.114 +/− 0.02 | 0.104 +/− 0.03 | - | 0.103 +/− 0.02 | 0.0966 +/− 0.02 | - |

Abbreviations: PLI=phase lag index; IC=imaginary part of coherency; MCS=minimally conscious state; VS=vegetative state

Values are means and standard deviations of the phase lag index and imaginary part of coherency in three frequency bands (delta, theta, alpha) for all bipolar montages (inter-hemisphere, frontal-to-posterior, left and right hemisphere).

uncorrected p<0.05;

p<0.05 corrected for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

Quantitative analysis of the EEG of 28 DOC patients showed that the relative power in the delta band was higher in the VS/UWS group than in the MCS group. However a drop in alpha power was observed in VS/UWS patients compared to MCS patients. Connectivity measurements showed that MCS patients had a better connected network in the theta and in the alpha bands. No differences were found in the acute vs chronic or in the traumatic vs non-traumatic settings.

The results in the delta band are in line with a previous study (31) which compared a group of MCS patients with patients affected by severe neurocognitive disorders (SNDs) and showed that the power in the delta band increased with the severity of the disorder, while it decreased in higher frequency bands. Thus, VS/UWS patients have a more marked slowing of brain electrical activity than MCS patients. Such observations have already been reported in clinical EEG inspection (32,33). Furthermore, EEG connectivity showed that MCS patients have better connected networks than VS/UWS patients. This result goes in the same direction as the results of a recent study in which SND patients consistently displayed a higher number of connections than MCS patients (34); thus, the level of connectivity could be related to the severity of the disorder.

A previous study showed that EEG could be used to diagnose DOC patients using the bispectral index (19), which was originally used to monitor the level of anesthesia and provides a unitless number between 0 (death) and 100 (fully awake). The advantage of the approach presented herein is that it offers features that can be interpreted from a physiological point of view and can thus provide a better understanding of the underpinnings of brain electrical activity. The IC and the PLI, which previously had never been used with DOC patients, succeeded in finding differences between MCS and VS/UWS patients, while standard coherence failed. However, these results were obtained at the group level, and further work needs to be done to disentangle VS/UWS and MCS patients at the individual level. Further improvements will include a higher density electrode cap to allow the use of source reconstruction techniques for better localization of the brain activity.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the European ICT Program Project FP7-247919. The text reflects solely the views of its authors. The European Commission is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. This research was funded by the Belgian National Funds for Scientific Research (FNRS), the James McDonnell Foundation, the Mind Science Foundation. RL, VC and CC are research fellows, QN, AS, MAB and AV are postdoctoral researchers, and SL is senior research associate at FNRS.

References

- 1.Laureys S, Celesia GG, Cohadon F, et al. Unresponsive wakefulness syndrome: a new name for the vegetative state or apallic syndrome. BMC Med. 2010;8:68. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jennett B, Plum F. Persistent vegetative state after brain damage. A syndrome in search of a name. Lancet. 1972;1:734–737. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)90242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giacino JT, Ashwal S, Childs N, Cranford MR, Jennett B, Katz DI, et al. The minimally conscious state: definition and diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 2002;58:349–353. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.3.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giacino J, Kalmar K. The vegetative and minimally conscious states: a comparison of clinical features and functional outcome. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 1997;12:36–54. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majerus S, Gill-Thwaites H, Andrews K, Laureys S. Behavioral evaluation of consciousness in severe brain damage. Prog Brain Res. 2005;150:397–413. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)50028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness. A practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)91639-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giacino JT, Kalmar K, Whyte J. The JFK Coma Recovery Scale-Revised: measurement characteristics and diagnostic utility. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85:2020–2029. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schnakers C, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Giacino J, Ventura M, Boly M, Majerus S, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the vegetative and minimally conscious state: clinical consensus versus standardized neurobehavioral assessment. BMC Neurol. 2009;9:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luauté J, Maucort-Boulch D, Tell L, et al. Long-term outcomes of chronic minimally conscious and vegetative states. Neurology. 2010;75:246–252. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e8e8df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schiff ND, Rodriguez-Moreno D, Kamal A, et al. fMRI reveals large-scale network activation in minimally conscious patients. Neurology. 2005;64:514–523. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150883.10285.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boly M, Faymonville ME, Peigneux P, et al. Auditory processing in severely brain injured patients - differences between the minimally conscious state and the persistent vegetative state. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:233–238. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wijnen VJ, van Boxtel GJ, Eilander HJ, de Gelder B. Mismatch negativity predicts recovery from the vegetative state. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kotchoubey B, Lang S, Mezger G, et al. Information processing in severe disorders of consciousness: vegetative state and minimally conscious state. Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;116:2441–2453. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2005.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daltrozzo J, Wioland N, Mutschler V, Kotchoubey B. Predicting coma and other low responsive patients outcome using event-related brain potentials: a meta-analysis. Clin Neurophysiol. 2007;118:606–614. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2006.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman MR, Rodd JM, Davis MH, et al. Do vegetative patients retain aspects of language comprehension? Evidence from fMRI. Brain. 2007;130:2494–2507. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monti MM, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Coleman MR, et al. Willful modulation of brain activity in disorders of consciousness. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:579–589. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owen AM, Coleman MR, Boly M, Davis MH, Laureys S, Pickard JD. Detecting awareness in the vegetative state. Science. 2006;313:1402. doi: 10.1126/science.1130197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schnakers C, Perrin F, Schabus M, et al. Voluntary brain processing in disorders of consciousness. Neurology. 2008;71:1614–1620. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000334754.15330.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schnakers C, Ledoux D, Majerus S, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic use of bispectral index in coma, vegetative state and related disorders. Brain Inj. 2008;22:926–931. doi: 10.1080/02699050802530565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nunez PL, Srinivasan R, Westdorp AF, et al. EEG coherency I: statistics, reference electrode, volume conduction, Laplacians, cortical imaging, and interpretation at multiple scales. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1997;103:499–515. doi: 10.1016/s0013-4694(97)00066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Srinivasan R, Nunez PL, Silberstein RB. Spatial filtering and neocortical dynamics: estimates of EEG coherence. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 1998;45:814–826. doi: 10.1109/10.686789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fein G, Raz J, Brown FF, Merrin EL. Common reference coherence data are confounded by power and phase effects. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1988;69:581–584. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(88)90171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Florian G, Andrew C, Pfurtscheller G. Do changes in coherence always reflect changes in functional coupling? Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1998;106:87–91. doi: 10.1016/s0013-4694(97)00105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lachaux JP, Rodriguez E, Martinerie J, Varela FJ. Measuring phase synchrony in brain signals. Hum Brain Mapp. 1999;8:194–208. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1999)8:4<194::AID-HBM4>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mormann F, Lehnertz K, David P, Elger CE. Mean phase coherence as a measure for phase synchronization and its application to the EEG of epilepsy patients. Physica D. 2000;144:358–369. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nolte G, Bai O, Wheaton L, Mari Z, Vorbach S, Hallett M. Identifying true brain interaction from EEG data using the imaginary part of coherency. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:2292–2307. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stam CJ, Nolte G, Daffertshofer A. Phase lag index: assessment of functional connectivity from multi channel EEG and MEG with diminished bias from common sources. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007;28:1178–1193. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schnakers C, Majerus S, Giacino J, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Bruno MA, Boly M, et al. A French validation study of the Coma Recovery Scale-Revised (CRS-R) Brain Inj. 2008;22:786–792. doi: 10.1080/02699050802403557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leclercq Y, Maquet P, Noirhomme Q, Phillips C. fMRI Artefact rejection and Sleep Scoring Toolbox (FAST) 2009. http://www.montefiore.ulg.ac.be/phillips/toolbox.html: Cyclotron Research Centre, University of Liege, Belgium. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Percival DB, Walden AT. Spectral Analysis for Physical Applications: Multitaper and Conventional Univariate Techniques. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leon-Carrion J, Martin-Rodriguez JF, Damas-Lopez J, Barroso y Martin JM, Dominguez-Morales MR. Brain function in the minimally conscious state: A quantitative neurophysiological study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2008;119:1506–1514. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brenner RP. The interpretation of the EEG in stupor and coma. Neurologist. 2005;11:271–284. doi: 10.1097/01.nrl.0000178756.44055.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thatcher R. EEG database-guided neurotherapy. In: Evans JR, Abarbanel A, editors. Introduction to Quantitative EEG and Neurofeedback. San Diego: Academic Press; 1999. pp. 29–60. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pollonini L, Pophale S, Situ N, et al. Information communication networks in severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Topogr. 2010;23:221–226. doi: 10.1007/s10548-010-0139-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]